Abstract

Objective

To examine whether intensive care unit (ICU) admission is independently associated with increased risk of major depression in patients with diabetes.

Methods

This prospective cohort study included 3596 patients with diabetes enrolled in the Pathways Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study, of whom 193 had at least one ICU admission over a 3-year period. We controlled for baseline depressive symptoms, demographics, and clinical characteristics. We examined associations between ICU admission and subsequent major depression using logistic regression.

Results

There were 2624 eligible patients who survived to complete follow-up; 98 had at least one ICU admission. Follow-up assessments occurred at a mean of 16.4 months post-ICU for those who had an ICU admission. At baseline, patients who had an ICU admission tended to be depressed, older, had greater medical comorbidity, and had more diabetic complications. At follow-up, the point prevalence of probable major depression among patients who had an ICU admission was 14% versus 6% among patients without an ICU admission. After multivariate adjustment, ICU admission was independently associated with subsequent probable major depression (Odds Ratio 2.07, 95% confidence interval (1.06–4.06)). Additionally, baseline probable major depression was significantly associated with post-ICU probable major depression.

Conclusions

ICU admission in patients with diabetes is independently associated with subsequent probable major depression. Additional research is needed to identify at-risk patients and potentially modifiable ICU exposures in order to inform future interventional studies with the goal of decreasing the burden of comorbid depression in older patients with diabetes who survive critical illnesses.

Keywords: intensive care unit, critical care, depression, diabetes, risk factors, outcome assessment (health care)

Introduction

Every year, millions of Americans require admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) for the treatment of a life-threatening illness (Davydow et al., 2008a). ICU admissions for the treatment of critical illnesses are an issue of particular importance for older patients, as patients over the age of 65 comprise over half of all ICU admissions (Ehlenbach et al., 2010). With advances in critical care medicine, more patients are surviving ICU admissions (Angus and Carlet, 2003), and interest has increased in longer-term patient-centered outcomes. Research in the field has demonstrated that ICU survivors report poorer quality of life as compared to the general population (Dowdy et al., 2005; Myhren et al., 2010). Furthermore, patients surviving critical illnesses have been found to have a high prevalence of clinically significant depressive symptoms in the months following hospital discharge (Davydow et al., 2009). However, it is unclear if ICU admission is an independent risk factor for depression, or if the elevated prevalence of post-ICU depression is due to confounding by other factors, such as pre-existing depression. While a history of major depression prior to a critical illness could be the primary risk factor for post-ICU depression, few studies of post-ICU psychopathology have examined prior psychiatric disorders as potential risk factors (Davydow et al., 2008a, 2009).

Patients with diabetes mellitus may face a uniquely heightened risk of comorbid major depression in the aftermath of a critical illness. Diabetes is a known risk factor for developing critical illnesses that require treatment in intensive care settings such as a severe myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure (CHF), and sepsis (Cheadle et al., 1996; Bell, 2003; Kelly et al., 2009). Furthermore, approximately 11–15% of patients with diabetes have comorbid major depression (Anderson et al., 2001). Also, comorbid depression in patients with diabetes is associated with poor glycemic control, higher rates of smoking, sedentary life-style, poor diet control, reduced adherence to disease controlling medications, and greater risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications (Ciechanowski et al., 2000; Katon et al., 2004a, 2010a; Lin et al., 2004, 2010), all factors that could increase the likelihood of developing a critical illness.

The Pathways Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study was a prospective population-based cohort investigation examining the potential adverse impact of major depression in primary care patients with diabetes (Katon et al., 2003). The aim of the current investigation was to utilize the Pathways Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study to examine whether ICU admission is independently associated with subsequent major depression. We hypothesized that ICU admission would be associated with a greater risk of subsequent major depression, after adjusting for baseline depression, demographic, and clinical characteristics.

Methods

The Pathways Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study was developed by a multidisciplinary team from the University of Washington and Group Health Cooperative (GHC) Research Institute. GHC is a mixed-model capitated health plan with 30 primary care clinics caring for approximately 523 000 patients in western Washington State. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by institutional review boards at the University of Washington and GHC.

Setting

Nine GHC clinics were selected for the Pathways Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study based on the following three criteria: (1) clinics with the largest populations of patients with diabetes, (2) clinics located within a 40-mile geographic radius of Seattle, and (3) clinics with the greatest amount of ethnic and racial diversity.

Patient population

The cohort for the Pathways Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study was initially sampled between 2000 and 2002. Patients enrolled in the Group Health Diabetes registry were recruited for the study based on previously described eligibility criteria (Katon et al., 2003, 2004b). The investigators obtained permission to review medical records from 4128 patients enrolled in the original Pathways study. Non-consenting patients were more often younger, female, non-white, less educated, had a shorter duration of diabetes, a lower mean body mass index (BMI), a lower mean hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C), and had less medical comorbidity (Katon et al., 2010b).

Predictor of interest

The predictor of interest was ICU admission, which was identified from inpatient location codes obtained through automated medical record review. Although enrollment into the Pathways Study began in March 2001, we could not differentiate the type of hospital admission due to lack of location codes for the first 2 years. Therefore, the present study reports on all ICU admissions that occurred over a 3-year period beginning in March 2003. We obtained primary ICU admission diagnoses (defined as the first listed diagnosis for the ICU admission) from automated medical record review.

Potential confounders

The baseline mailed survey included information regarding depression, sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, race, educational level, and marital status), and questions regarding smoking status and physical activity from the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Questionnaire (Toobert et al., 2000). We ascertained baseline non-diabetic medical comorbidity with the RxRisk, an automated pharmacy-based data model based on prescription drug use over the prior 12 months (Fishman et al., 2003). We used the Diabetes Complications Severity Index (DCSI), an automated-data derived measure of diabetic complications based on International Classification of Disease-9th Revision diagnostic codes for diabetic complications and laboratory tests, to assess severity of diabetic complications (Young et al., 2008).

Outcome of interest

Probable major depression was assessed at baseline and at the 5-year follow-up survey with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (Spitzer et al., 1999). This questionnaire can be utilized as a continuous measure of depressive symptom severity (range 0–27). In addition, patients with a PHQ-9 score ≥10 with ≥5 symptoms scored as being present for half of the days or more for at least 2 weeks (with one of the symptoms being either depressed mood or anhedonia) have symptoms suggestive of the diagnosis of major depression. Patients with 2–4 depressive symptoms for more than half the days for at least 2 weeks (with one of the symptoms being either depressed mood or anhedonia) have symptoms suggestive of minor depression. The PHQ-9 threshold of ≥10 for a probable case of major depression has been found to have high sensitivity (73%) and specificity (98%) for the diagnosis of major depression based on structured psychiatric interview (Spitzer et al., 1999; Kroenke et al., 2001). A total of 329 patients that scored ≥10 on the PHQ-9 were randomized into a depression intervention versus usual care study (Katon et al., 2004c). Analyses from the present study controlled for randomization status.

Statistical analysis

Initially, we examined differences between patients who completed the 5-year assessment and those who did not but were still alive at the 5-year assessment date on baseline depression, demographics, and clinical characteristics. We used chi-square (χ2) tests for categorical variables and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables.

To address the issue of non-random missingness of the 5-year assessment, we used propensity score methodology to balance the groups on the observed variables (Rao et al., 2005). We created a non-response propensity score for each subject eligible for the follow-up assessment, which is the conditional probability of being a non-respondent at 5-year follow-up, based on baseline characteristics. To create the non-response propensity scores, we performed a logistic regression in which the dependent variable was follow-up versus no follow-up and the covariates were all significantly different baseline variables. This model then produced probabilities for each subject, conditional on their observed baseline variables. We used these probabilities as a regression adjustment in all subsequent analyses (Rao et al., 2005).

Next, we used χ2 tests and one-way ANOVA to assess for significant univariate associations between ICU admission, baseline probable minor and major depression, demographics, and clinical characteristics, with probable major depression at follow-up. Then, we created logistic regression models estimating the likelihood of meeting criteria for probable major depression at the 5-year follow-up assessment. First, we tested the association of ICU admission and probable major depression at follow-up without adjustment. We then added two groups of potential confounding variables to the regression model: (1) design variables selected a priori that have been found to be important in diabetes–depression comorbidity research (Katon et al., 2009) (e.g., baseline depressive symptoms, age, gender, categorized RxRisk score, and DCSI score) non-response propensity scores, interventional trial randomization status, and (2) baseline demographics and clinical characteristics found to be significant to p ≤ 0.05 from the univariate analyses. Since there were only 98 patients with our predictor of interest, ICU admission, over the 3-year follow-up period of this study who completed the follow-up assessment, we limited the number of covariates in our regression models to 10 (Peduzzi et al., 1996). Finally, as a secondary analysis to examine onset of probable major depression at follow-up, we created two logistic regression models, stratified by probable baseline major depression status.

As a sensitivity analysis, we re-fit the logistic regression models without non-response propensity adjustments. Analyses were performed with appropriate components of the IBM SPSS Statistics 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) statistical software program.

Results

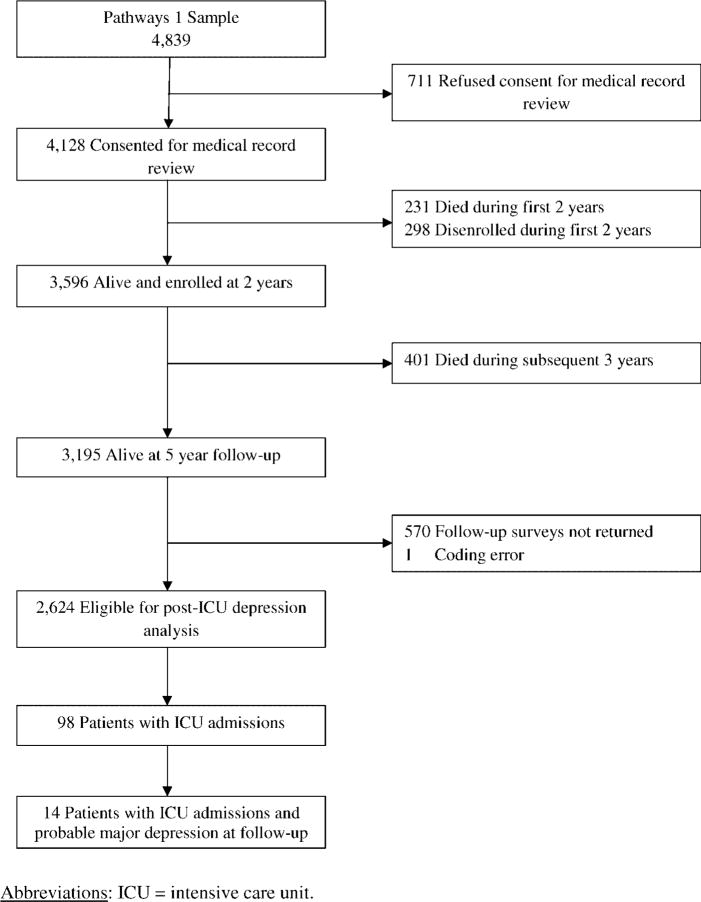

Figure 1 describes the flow of patients from the baseline mailed survey of the Pathways Epidemiologic Study through the completion of a telephone survey approximately 5 years later (the Pathways Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study). Of the 3596 patients alive and enrolled in the Pathways Epidemiologic Study at 2 years, 193 had at least one ICU admission over the next 3 years. Of these patients, 126 were alive at the time of the 5-year follow-up, and 98 completed the follow-up assessment.

Figure 1.

Pathways follow-up study flow diagram. Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit.

Table 1 describes differences between the 2624 patients eligible for the Pathways post-ICU depression analysis and the 571 patients who were lost to follow-up but survived the 5-year period. Patients lost to follow-up were more likely to be older, single, non-white, less educated, had more medical comorbidity, and were smokers. Among survivors, there was no association between having an ICU admission between years 3 and 5 and likelihood of completing the follow-up assessment (χ2 = 1.72, p = 0.19).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients included and not included in the follow-up analysis

| Variables | Total (n = 3195) | Follow-up (n = 2624) | No follow-up (n = 571) | Test statisticsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62.2 (12.8) | 61.7 (12.3) | 64.4 (14.7) | F = 22.05*** |

| Female | 1559 (48.8%) | 1291 (49.2%) | 268 (47.0%) | χ2 = 0.88 |

| Married | 2099 (65.7%) | 1748 (66.6%) | 351 (61.6%) | χ2 = 5.22* |

| Whiteb | 2556 (80.2%) | 2138 (81.6%) | 418 (73.2%) | χ2 = 26.58*** |

| Black | 275 (8.6%) | 207 (7.9%) | 68 (12.0%) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 268 (8.4%) | 198 (7.6%) | 70 (12.3%) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 50 (1.6%) | 44 (1.7%) | 6 (1.1%) | |

| Hispanic or Other | 38 (1.2%) | 32 (1.2%) | 6 (1.1%) | |

| Education beyond high school | 2487 (77.8%) | 2112 (80.5%) | 375 (65.8%) | χ2 = 58.41*** |

| RxRisk score | 2822.2 (2195.6) | 2760.2 (2154.4) | 3108.0 (2357.3) | F = 11.79** |

| DCSI | 1.5 (1.7) | 1.5 (1.6) | 1.6 (1.7) | F = 0.44 |

| Current smoking | 267 (8.4%) | 200 (7.6%) | 67 (11.8%) | χ2 = 10.46** |

| Exercise | ||||

| ≤1 day per week | 985 (30.8%) | 816 (31.1%) | 169 (29.6%) | χ2 = 0.45 |

| 2–7 days per week | 2210 (69.2%) | 1809 (68.9%) | 401 (70.4%) | |

| PHQ-9 Score (of 27) | 5.5 (5.4) | 5.5 (5.4) | 5.8 (5.5) | F = 1.03 |

| Enrolled in RCT | 242 (7.6%) | 207 (7.9%) | 35 (6.1%) | χ2 = 2.04 |

All values are mean ± SD or n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations (in alphabetic order): χ2, chi-square; DCSI, Diabetes Complications Severity Index; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

F-statistic with 3194 degrees of freedom or Pearson χ2 with 1 degree of freedom.

Eight subjects had missing data on their ethnic background.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

Telephone follow-up assessments occurred at a mean of 491.4 days (standard deviation 300.5 days, median 530.5 days, interquartile range 176–775.5 days, absolute range 11–1004 days) post-ICU for those patients with an ICU admission. Patients who had an ICU admission between years 3 and 5 were more likely to meet criteria for probable major depression at baseline (χ2 = 12.31, p < 0.001), were older (F = 4.49, p = 0.03), had greater medical comorbidity (χ2 = 18.22, p < 0.001), and had greater severity of diabetic complications (F = 21.73, p < 0.001). The most common ICU admission diagnoses included the following: myocardial infarction (n = 21), arrhythmia (n = 12), pneumonia (n = 11), congestive heart failure (n = 9), sepsis (n = 8), and acute respiratory failure (n = 7).

Table 2 presents baseline differences between patients with and without probable major depression at the 5-year follow-up assessment. Of patients with probable major depression at follow-up, 58% either were not depressed or met criteria for probable minor depression at baseline, and 42% met criteria for probable major depression at baseline. Patients with probable major depression at follow-up were more likely to be younger, single, were smokers, sedentary, and met criteria for either probable minor or major depression at baseline.

Table 2.

Associations of baseline characteristics with probable major depression at follow-up

| Variables | Total (n = 2624) | No depression (n = 2470) | Major depression (n = 154) | Test statisticsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.7 (12.3) | 61.8 (12.3) | 58.6 (12.6) | F = 9.92** |

| Female | 1291 (49.2%) | 1207 (48.9%) | 84 (54.5%) | χ2 = 1.87 |

| Married | 1747 (66.6%) | 1658 (67.1%) | 89 (57.8%) | χ2 = 5.68* |

| Whiteb | 2137 (81.6%) | 2015 (81.8%) | 122 (79.2%) | χ2 = 0.77 |

| Black | 207 (7.9%) | 193 (7.8%) | 14 (9.1%) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 198 (7.6%) | 185 (7.5%) | 13 (8.4%) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 44 (1.7%) | 40 (1.6%) | 4 (2.6%) | |

| Hispanic or Other | 32 (1.2%) | 31 (1.3%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Education beyond high school | 2112 (80.5%) | 1990 (80.6%) | 122 (79.2%) | χ2 = 0.17 |

| RxRisk score | 2758.4 (2152.9) | 2758.3 (2151.9) | 2758.9 (2175.2) | F = 0.00 |

| DCSI | 1.5 (1.6) | 1.5 (1.6) | 1.7 (1.5) | F = 2.30 |

| Current smoking | 200 (7.6%) | 181 (7.3%) | 19 (12.3%) | χ2 = 5.17* |

| Exercise | ||||

| ≤1 day per week | 815 (31.1%) | 750 (30.4%) | 65 (42.2%) | χ2 = 9.50** |

| 2–7 days per week | 1809 (68.9%) | 1720 (69.6%) | 89 (57.8%) | |

| Major depression | 280 (10.7%) | 215 (8.7%) | 65 (42.2%) | χ2 = 170.31*** |

| minor depression | 189 (7.2%) | 170 (6.9%) | 19 (12.3%) | χ2 = 6.42* |

| Enrolled in RCT | 206 (7.9%) | 165 (6.7%) | 41 (26.6%) | χ2 = 79.70*** |

All values are mean ± SD or n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations (in alphabetic order): χ2, chi-square; DCSI, Diabetes Complications Severity Index; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

F-statistic with 2623 degrees of freedom or Pearson χ2 with 1 degree of freedom.

Six subjects had missing data on their ethnic background.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

Among patients with at least one ICU admission, the point prevalence of probable major depression at the 5-year follow-up was 14% versus 6% for patients without an ICU admission (χ2 = 13.06, p < 0.001). After adjustment for potential confounders, a significant association remained between ICU admission and probable major depression at follow-up (p = 0.03) (Table 3). Baseline depressive symptoms were also significantly associated with probable major depression at follow-up (Odds Ratio (OR) 1.18, 95% confidence interval (CI) (1.15–1.22)). Furthermore, among patients who had at least one ICU admission and completed the 5-year follow-up, baseline probable major depression was significantly associated with probable major depression at follow-up (χ2 = 17.82, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Models of association of intensive care unit admission and probable major depression at follow-up

| Association of ICU admission after covariate adjustment | Probable major depression, Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Unadjusted | 2.84 (1.58–5.14)** |

| Design variables,a propensity scores, and additional significant demographic and clinical characteristicsb | 2.07 (1.06–4.06)* |

Abbreviations (in alphabetic order): CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit.

Design variables: age, gender, baseline depressive symptoms, RxRisk, and Diabetes Complications Severity Index

Additional significant demographic and clinical characteristics: marital status, smoking, physical inactivity, and randomization status in the pathways randomized controlled trial.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

When we stratified by probable major depression status at baseline, we found a significant association between ICU admission and probable major depression at follow-up among patients without baseline probable major depression in unadjusted (OR 2.81, 95% CI (1.09–7.27)) and adjusted (OR 2.90, 95% CI (1.08–7.08)) analyses. Among patients with probable major depression at baseline, we found a significant association between ICU admission and probable major depression at follow-up in the unadjusted analysis (OR 2.35, 95% CI (1.02–5.40)), and a trend towards an association in the adjusted analysis (OR 1.71, 95% CI(0.69–4.24)).

In our sensitivity analyses, we found no difference between models with or without inclusion of the propensity adjustment for non-response.

Discussion

In this prospective investigation of patients with diabetes, ICU admission was associated with a 2.07 times as high odds of subsequent probable major depression, even after adjusting for baseline depressive symptoms, demographics, and baseline clinical characteristics. Furthermore, for each point increase in a patient’s baseline PHQ-9 score, their odds of probable major depression at follow-up increased by 18%. In a secondary analysis, stratified by baseline probable major depression status, we found a similar significant association between ICU admission and onset of subsequent probable major depression among patients without probable major depression at baseline, and a trend towards an association among patients with probable major depression at baseline. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first investigation of post-ICU psychopathology to include a standardized measure of depressive symptoms administered to patients prospectively, and only the second study to examine pre-critical illness depression as a risk factor for post-ICU depressive symptoms (Davydow et al., 2009).

Comorbid major depression in older patients with diabetes surviving ICU admission may be particularly severe and debilitating. Major depression is known to be a significant predictor of functional and cognitive decline in aging populations (Spitzer et al., 1995; Steffens et al., 2006). Also, the Pathways randomized controlled trial found that over 70% of patients with a PHQ-9 score ≥10 reported that they had been depressed for more than 2 years (Katon et al., 2004c). In addition, depressive symptoms in the aftermath of a critical illness or severe injury are associated with lack of return to work (Zatzick et al., 2008; Adhikari et al., 2009). Furthermore, ICU admission in older adults has been found to be associated with subsequent cognitive decline (Ehlenbach et al., 2010), and post-ICU depression has been found to be associated with cognitive impairment (Jackson et al., 2003; Hopkins et al., 2010). These findings potentially compound the heightened risk for adverse cognitive outcomes that older patients with diabetes, and particularly those with diabetes and comorbid depression, face (Strachan et al., 2008; Katon et al., 2010b).

In patients with diabetes, the etiology of depression following an ICU admission is likely multi-factorial. A potential biological etiology could be an increase in pro-inflammatory factors associated with critical illnesses and their risk factors. Comorbid depression in patients with diabetes is associated with increased inflammation and abnormalities in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which lead to chronic gluco-corticoid elevations (Musselman et al., 2003). Also, since patients leaving the ICU may have physical and cognitive deficits, and family lives can be disrupted by prolonged hospitalizations and recovery periods, feelings of loss can be substantial in these patients, and could be an ‘understandable’ cause of depression/demoralization (Davydow et al., 2008b). It is probable that these and other etiologic factors play a role in the development of depression in older patients with diabetes after a critical illness.

With increasing recognition of depression as a considerable public health dilemma (Moussavi et al., 2007), a potential increased risk of major depression in the aftermath of critical illnesses is a serious concern in light of the number of patients requiring ICU admission annually in the U.S. alone, the increased risk of adverse medical outcomes associated with major depression (Katon et al., 2004b; Lin et al., 2010), and the enormous healthcare costs attributable to critical illnesses and ICU admissions (Halpern and Pastores, 2010). Therefore, future research into post-ICU depression should focus on potential interventions that may reduce the burden of depressive symptoms after a critical illness. Since substantial depressive symptoms prior to a critical illness appear to convey substantial risk for post-ICU depression, interventions that focus on screening to identify patients with a prior history of depression for early referral and potential treatment after hospital discharge should be studied. Studies of screening and treatment interventions for comorbid depression and medical conditions have demonstrated reductions in depressive symptom burden, improvements in physical functioning, lower likelihood of cognitive decline, and improvement in quality of life (Katon et al., 2004c; Williams et al., 2004; Callahan et al., 2005; Hunkeler et al., 2006; Steffens et al., 2007). New interventions are being designed to translate improved depression treatment in patients with diabetes into improvements in medical outcomes (Katon et al., 2010c).

Since the present study highlights that ICU admission is independently associated with subsequent depression, additional investigations are needed to identify potentially modifiable risk factors that may occur in the ICU setting in addition to screening patients for a history of depression. In-ICU hypoglycemia has been found to be associated with increased depressive symptoms following acute lung injury (Dowdy et al., 2008). Also, benzodiazepine sedation has been shown to be associated with greater risk of depression 6 months after an ICU admission (Dowdy et al., 2009). Furthermore, delirium is highly prevalent in the ICU (Pisani et al., 2003), and patients may be at elevated risk for depression following episodes of delirium (Davydow, 2009). Identification of in-ICU risk factors for post-ICU psychopathology could also complement screening for pre-critical illness psychiatric history and lead to risk-prediction algorithms that identify high-risk patients for early interventions.

Several important limitations of the present study are noted. First, we did not have location codes for ICU admission for the first 2 years of the Pathways Epidemiologic Study, so we are only able to report on the potential association of ICU admissions between years 3 and 5 and subsequent depression. Second, only 14 patients who had an ICU admission and completed the follow-up assessment were found to meet criteria for probable major depression, tempering confidence in our findings. Third, since depressive symptoms were assessed using a questionnaire (i.e., PHQ-9), and not a structured or semi-structured diagnostic interview, a diagnosis of major depression could not be made, hence the use of the phrases ‘probable major depression’ or ‘symptoms suggestive of major depression’ throughout. Furthermore, a single administration of the PHQ-9 at follow-up as done in our study only provides a snapshot of a patient’s symptoms following a critical illness, and does not provide a picture of when depression may develop in the post-ICU course. Fifth, our investigation lacked sufficient power to identify associations between specific ICU exposures and risk of subsequent depression. An additional limitation is that we only measured depression at baseline and at 5 years, and the first ICU admission, but not recurrent ICU admissions during follow-up, were measured. Given the relatively small number of ICU admissions during years 3–5 of the follow-up period and the lack of measurement of repetitive ICU admits, we were not able to study time-to-ICU admit and depression outcomes. Also, this study was completed in only one geographic region of the U.S., potentially limiting generalizability. Finally, due to the observational nature of the present investigation, the possibility of residual confounding does exist.

Conclusions

In conclusion, ICU admission is independently associated with subsequent probable major depression in patients with diabetes. In addition, probable major depression prior to ICU admission is associated with subsequent depression in patients with diabetes. Future research should strive to identify potentially modifiable ICU exposures that increase the risk of post-ICU depression. This information could inform a comprehensive risk-prediction algorithm that includes screening for prior depression, identifying high-risk patients with diabetes for interventions that can reduce the burden of depressive symptoms and improve their quality of life.

Key points.

Intensive care unit (ICU) admission in patients with diabetes was found to be independently associated with subsequent clinically significant depressive symptoms.

For each point increase in a patient’s baseline Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score, their odds of probable major depression at follow-up increased by 18%.

Future research should strive to identify at-risk patients and potentially modifiable ICU exposures in order to inform interventional studies with the goal of decreasing the burden of comorbid depression in patients with diabetes who survive critical illnesses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants NRSA-T32/MH20021-12 (Katon), K24MH069741-07 (Katon), and RO1MH073686-04 (Von Korff) from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Dr Katon has received honorariums for lectures from Wyeth, Eli Lilly, Forest, and Pfizer pharmaceutical companies and serves on the Advisory Board for Eli Lilly and Wyeth. Dr Von Korff has received grant funding from Johnson & Johnson. Dr Ciechanowski is CEO and founder of Samepage, Inc., a consulting company providing services for improving patient–provider relationships. Dr Lin has received honorariums from Health Star Communications and Prescott Medical. Drs Davydow, Hough, Russo, Ludman, and Young, and Ms Oliver have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Adhikari NKJ, McAndrews MP, Tansey CM, et al. Self-reported symptoms of depression and memory dysfunction in survivors of ARDS. Chest. 2009;135:678–687. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, et al. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1069–1078. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus DC, Carlet J. Surviving intensive care: a report from the 2002 Brussels Roundtable. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:368–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell DSH. Heart failure: the frequent, forgotten, and often fatal complication of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2433–2441. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.8.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan CM, Kroenke K, Counsell SR, et al. Treatment of depression improves physical functioning in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:367–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle WG, Mercer-Jones M, Heinzelmann M, et al. Sepsis and septic complications in the surgical patient: who is at risk? Shock. 1996;6:S6–S9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3278–3285. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydow DS, Gifford JM, Desai SV, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in general intensive care unit survivors: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008a;30:421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydow DS, Desai SV, Needham DM, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review. Psychosom Med. 2008b;70:512–519. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816aa0dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydow DS, Gifford JM, Desai SV, et al. Depression in general intensive care unit survivors: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:796–809. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1396-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydow DS. Symptoms of depression and anxiety following delirium. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:309–316. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.4.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdy DW, Eid MP, Sedrakyan A, et al. Quality of life in adult survivors of critical illness: a systematic review of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:611–620. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2592-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdy DW, Dinglas V, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. Intensive care unit hypoglycemia predicts depression during early recovery after acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2726–2733. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818781f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdy DW, Bienvenu OJ, Dinglas VD, et al. Are intensive care factors associated with depressive symptoms six months after acute lung injury? Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1702–1707. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819fea55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlenbach WJ, Hough CL, Crane PK, et al. Association between acute care and critical illness hospitalization and cognitive function in older adults. J Am Med Assoc. 2010;303:763–770. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman PA, Goodman MJ, Hornbrook MC, et al. Risk adjustment using automated ambulatory pharmacy data: the RxRisk model. Med Care. 2003;41:84–99. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern NA, Pastores SM. Critical care medicine in the United States 2000-2005: an analysis of bed numbers, occupancy rates, payer mix, and costs. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:65–71. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b090d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins RO, Key CW, Suchyta MR, et al. Risk factors for depression and anxiety in survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunkeler EM, Katon W, Tang L, et al. Long term outcomes from the IMPACT randomized trial for depressed elderly patients in primary care. Br Med J. 2006;32:259–263. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38683.710255.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JC, Hart RP, Gordon SM, et al. Six-month neuropsychological outcome of medical intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1226–1234. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000059996.30263.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Improving primary care treatment of depression among patients with diabetes mellitus: the design of the Pathways Study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:158–168. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, et al. Behavioral and clinical factors associated with depression among individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004a;27:914–920. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.4.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Lin EH, Russo J, et al. Cardiac risk factors in patients with diabetes mellitus and major depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2004b;19:1192–1199. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, et al. The Pathways Study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004c;61:1042–1049. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Russo J, Lin EHB, et al. Depression and diabetes: factors associated with major depression at five-year follow-up. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:570–579. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Russo JE, Heckbert SR, et al. The relationship between changes in depression symptoms and changes in health risk behaviors in patients with diabetes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010a;25:466–475. doi: 10.1002/gps.2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Lin EHB, Williams LH, et al. Comorbid depression is associated with an increased risk of dementia diagnosis in patients with diabetes: a prospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2010b;25:423–429. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1248-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Integrating depression and chronic disease care among patients with diabetes and/or coronary heart disease: the design of the TEAM care study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010c;31:312–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly TN, Bazzano LA, Fonseca VA, et al. Systematic review: glucose control and cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:394–403. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-6-200909150-00137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Relationship of diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2154–2160. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EH, Rutter CM, Katon W, et al. Depression and advanced complications of diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:264–269. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:851–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musselman DL, Betan E, Larsen H, et al. Relationship of depression to diabetes types 1 and 2: epidemiology, biology, and treatment. Biol Psychiatr. 2003;54:317–329. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myhren H, Ekeberg Ø, Stokland O. Health-related quality of life and return to work after critical illness in general intensive care unit patients: a 1-year follow-up study. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1554–1561. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e2c8b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, et al. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani MA, McNichol L, Inouye SK. Cognitive impairment in the intensive care unit. Clin Chest Med. 2003;24:727–737. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(03)00092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao RS, Sigurdson AJ, Doody MM, et al. An application of a weighting method to adjust for non-response in standardized incidence-ratio analysis of cohort studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Linzer M, et al. Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with mental disorders. Results from the PRIME-MD 1000 Study. J Am Med Assoc. 1995;274:1511–1517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study: Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders; patient health questionnaire. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffens DC, Snowden M, Fan MY, et al. Cognitive impairment and depression outcomes in the IMPACT Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2006;14:401–409. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000194646.65031.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strachan MW, Reynolds RM, Frier BM, et al. The relationship between type 2 diabetes and dementia. Br Med Bull. 2008;88:131–146. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldn042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from seven studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:943–950. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JW, Jr, Katon W, Lin EH, et al. The effectiveness of depression care management on diabetes-related outcomes in older patients. Ann Int Med. 2004;140:1015–1024. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-12-200406150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young BA, Lin E, Von Korff M, et al. Diabetes Complications Severity Index and risk of mortality, hospitalization, and healthcare utilization. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:15–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatzick D, Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP, et al. A national US study of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and work and functional outcomes after hospitalization for traumatic injury. Ann Surg. 2008;248:429–437. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318185a6b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]