Abstract

Studies of racial disparities in access to living donor kidney transplantation focus mainly on patient factors, whereas donor factors remain largely unexamined. Here, data from the US Census Bureau were combined with data on all African-American and white living kidney donors in the United States who were registered in the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) between 1998 and 2010 (N=57,896) to examine the associations between living kidney donation (LKD) and donor median household income and race. The relative incidence of LKD was determined in zip code quintiles ranked by median household income after adjustment for age, sex, ESRD rate, and geography. The incidence of LKD was greater in higher-income quintiles in both African-American and white populations. Notably, the total incidence of LKD was higher in the African-American population than in the white population (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.20; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.17 to 1.24]), but ratios varied by income. The incidence of LKD was lower in the African-American population than in the white population in the lowest income quintile (IRR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.78 to 0.90), but higher in the African-American population in the three highest income quintiles, with IRRs of 1.31 (95% CI, 1.22 to 1.41) in Q3, 1.50 (95% CI, 1.39 to 1.62) in Q4, and 1.87 (95% CI, 1.73 to 2.02) in Q5. Thus, these data suggest that racial disparities in access to living donor transplantation are likely due to socioeconomic factors rather than cultural differences in the acceptance of LKD.

For patients with ESRD, living donor kidney transplantation is the preferred therapy because it allows for timely transplantation and is associated with superior outcomes compared with deceased donor transplantation or dialysis.1,2 Living kidney donors facilitate >5000 kidney transplants in the United States per annum.1 By obviating the need for dialysis, each living donor provides an estimated health care savings of $100,000.3 Living kidney donation (LKD) expanded dramatically in the 1990s and early 2000s; however, living donation rates have plateaued and recently retracted in the last 8 years.1 Living donor transplantation is less frequent among African Americans and it is assumed that this is due in part to lower rates of kidney donation among African Americans.4,5 However, this association may be confounded by lower socioeconomic status and a higher prevalence of ESRD in the African-American population compared with the white population. To inform new strategies to expand LKD, we examined the association of median household income (as an indicator of socioeconomic status) with LKD in the African-American and white US populations.

Results

Population Characteristics

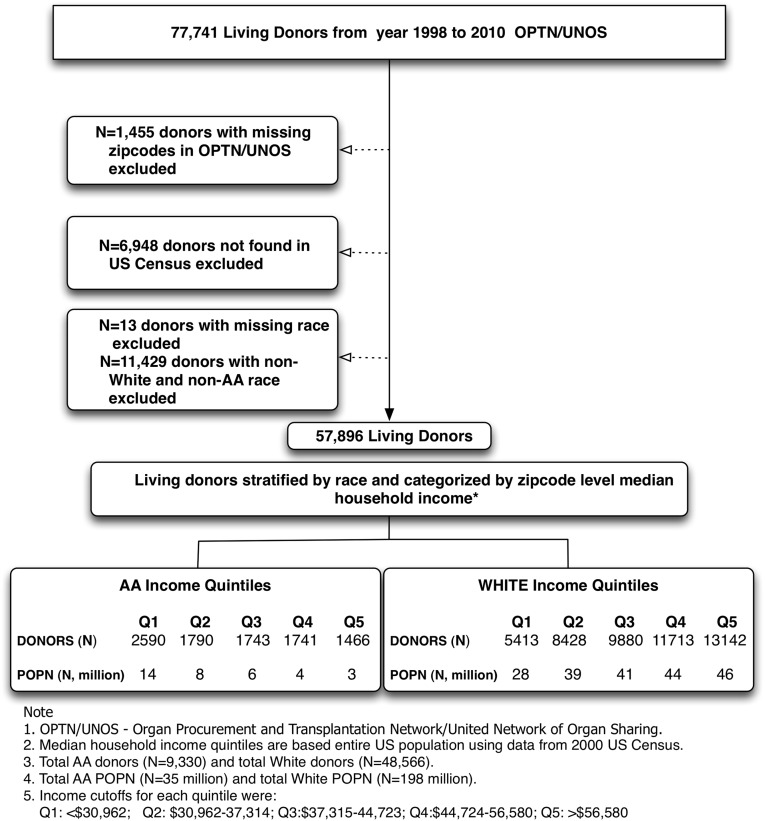

Figure 1 outlines the selection of the study cohort and Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the African-American and white populations in the United States by zip code quintile of median household income. The majority of the African-American population is distributed in the lowest three zip code quintiles, whereas the white population is more evenly distributed across all quintiles. The rate of ESRD was highest in the lower-income quintiles in both the African-American and white populations. However, in all zip code quintiles, ESRD rates were higher in the African-American population compared with the white population.

Figure 1.

Outline of cohort selection. All N=77,741 living kidney donors reported to OPTN/UNOS between 1998 and 2010 were identified. After excluding 8403 donors with no recorded residential zip code in either OPTN/UNOS data or the US Census and 11,442 donors with missing or non-white and non-African-American race, 57,896 living kidney donors were identified for study inclusion.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the African-American and white populations in the United States by zip code quintile of median household income

| Characteristic | Median Household Income Quintiles | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (<$30,962) | Q2 ($30,962–$37,314) | Q3 ($37,315–$44,723) | Q4 ($44,724–$56,580) | Q5 (>$56,580) | ||

| African-American population | ||||||

| Population (n) | 14 million | 8 million | 6 million | 4 million | 3 million | |

| Age (yr) | 34±14 | 33±11 | 32±11 | 31±10 | 31±10 | <0.001 |

| Age categories (yr) | <0.001 | |||||

| 18–39 | 47 | 51 | 52 | 52 | 48 | |

| 40–59 | 34 | 33 | 33 | 34 | 40 | |

| ≥60 | 19 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 12 | |

| Female sex | 52 | 51 | 52 | 52 | 51 | 0.42 |

| Age and sex standardized ESRD rate (pmp) | 762 | 653 | 594 | 540 | 502 | <0.001 |

| Residence | ||||||

| Metropolitan | 84 | 86 | 94 | 98 | 99 | <0.001 |

| Micropolitan | 7 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Rural residence | 9 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | <0.001 |

| White population | ||||||

| Population (n) | 28 million | 39 million | 41 million | 44 million | 46 million | <0.001 |

| Age (yr) | 49±4 | 48±4 | 48±3 | 47±3 | 46±4 | <0.001 |

| Age categories (yr) | <0.001 | |||||

| 18–39 | 40 | 38 | 39 | 39 | 37 | |

| 40–59 | 32 | 34 | 35 | 37 | 42 | |

| ≥60 | 28 | 28 | 26 | 24 | 21 | |

| Female sex | 52 | 52 | 52 | 52 | 52 | 0.41 |

| Age and sex standardized ESRD rate (pmp) | 358 | 319 | 294 | 262 | 215 | <0.001 |

| Residence | ||||||

| Metropolitan | 49 | 54 | 73 | 91 | 99 | <0.001 |

| Micropolitan | 20 | 23 | 16 | 5 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Rural | 31 | 23 | 11 | 4 | 0 | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or percentages, unless otherwise stated. Where not stated, missing values comprised <5% of all values.

Donor Characteristics

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of African-American and white donors. Compared with white donors, African-American donors were younger and were mostly related to their recipients and this was consistent within each median household income category. Higher-income donors were older, were more likely to donate to spouses, and were more likely to live in metropolitan regions compared with lower-income donors, and these associations were consistent in both African-American and white donors. Importantly, the vast majority of donors donated to recipients of the same race and income category (Table 2). This remained true even after exclusion of donor and recipient pairs residing in the same zip code (data not shown).

Table 2.

Characteristics of African-American and white living kidney donors in the United States by zip code quintile of median household income

| Characteristic | Median Household Income Quintiles | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (<$30,962) | Q2 ($30,962–$37,314) | Q3 ($37,315–$44,723) | Q4 ($44,724–$56,580) | Q5 (>$56,580) | ||

| African-American donors | ||||||

| Donors (n) | 2590 | 1790 | 1743 | 1741 | 1466 | |

| Age (yr) | 36±10 | 36±11 | 36±11 | 37±10 | 37±11 | <0.001 |

| Age categories (yr) | <0.001 | |||||

| 18–39 | 65 | 67 | 66 | 62 | 57 | |

| 40–59 | 34 | 32 | 33 | 37 | 41 | |

| ≥60 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Female sex | 55 | 55 | 57 | 60 | 56 | 0.01 |

| Donor type | <0.001 | |||||

| Related | 82 | 81 | 78 | 77 | 75 | |

| Spousal | 7 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 11 | |

| Other unrelated | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 14 | |

| Recipient race | <0.001 | |||||

| White | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | |

| Black | 97 | 96 | 95 | 95 | 94 | |

| Other | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Recipient income | <0.001 | |||||

| Q1 (<$30,962) | 65 | 18 | 14 | 14 | 11 | |

| Q2 ($30,962–$37,314) | 12 | 55 | 13 | 10 | 9 | |

| Q3 ($37,315–$44,723) | 10 | 11 | 53 | 13 | 12 | |

| Q4 ($44,724–$56,580) | 8 | 9 | 12 | 52 | 13 | |

| Q5 (>$56,580) | 5 | 7 | 8 | 11 | 55 | |

| White donors | ||||||

| Donors (n) | 5413 | 8418 | 9880 | 11,713 | 13,142 | |

| Age (yr) | 40±11 | 41±11 | 41±11 | 42±11 | 43±11 | <0.001 |

| Age categories (yr) | <0.001 | |||||

| 18–39 | 48 | 46 | 45 | 43 | 37 | |

| 40–59 | 48 | 50 | 51 | 53 | 58 | |

| ≥60 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| Female sex | 58 | 60 | 60 | 59 | 59 | 0.01 |

| Donor type | <0.001 | |||||

| Related | 66 | 63 | 64 | 62 | 62 | |

| Spousal | 12 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 15 | |

| Other unrelated | 22 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 23 | |

| Recipient race | <0.001 | |||||

| White | 94 | 95 | 96 | 95 | 94 | |

| Black | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | |

| Other | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| Recipient income | <0.001 | |||||

| Q1 (<$30,962) | 58 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 3 | |

| Q2 ($30,962–$37,314) | 13 | 56 | 13 | 9 | 7 | |

| Q3 ($37,315–$44,723) | 10 | 13 | 53 | 13 | 10 | |

| Q4 ($44,724–$56,580) | 10 | 13 | 15 | 55 | 16 | |

| Q5 (>$56,580) | 9 | 9 | 13 | 18 | 64 | |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or percentages, unless otherwise stated. Where not stated, missing values comprised <5% of all values.

Association of Median Household Income with Living Donor Rate per Million Population

Figure 2 displays age and sex standardized living donor rates per million population (pmp) within each zip code quintile of median household income and shows lower living donor rates in lower-income zip codes in both African-American and white populations. However, this association was more evident in the African-American population; the absolute difference in the living donor rate between the lowest and highest income quintiles was 25 pmp compared with 8 pmp in the white population. Overall, living donor rates were higher in the African-American population; however, this difference was most evident in the high-income zip codes. In a sensitivity analysis using 2010 US Census data, these associations between median household income with age and sex standardized living donor rates persisted in both African-American and white populations (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Age and sex standardized living donor rates per million population by quintile of median household income in African-American and white populations.

Adjusted Relative Incidence of LKD by Median Household Income

Table 3 shows the fully adjusted incidence rate ratio (IRR) for LKD in each zip code quintile of median household income (Q2, Q3, Q4, and Q5) compared with the lowest income quintile (Q1) in the African-American and white populations. The relative incidence of living donation was significantly greater in higher-income zip codes in both race groups. These income-related differences were larger in the African-American population (for Q5 versus Q1: IRR, 1.79; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.63 to 1.95) than the white population (for Q5 versus Q1: IRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.13 to 1.24). These findings were consistent for both biologically related and unrelated (including spousal) living donors (data not shown).

Table 3.

Adjusted relative incidence of LKD by zip code quintile of median household income in African-American and white populationsa

| Income Quintile | African-American Population | White Population |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 (<$30,962) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Q2 ($30,962–$37,314) | 1.09 (1.02 to 1.17) | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.07) |

| Q3 ($37,315–$44,723) | 1.26 (1.17 to 1.35) | 1.11 (1.07 to 1.15) |

| Q4 ($44,724–$56,580) | 1.53 (1.41 to 1.65) | 1.15 (1.11 to 1.20) |

| Q5 (>$56,580) | 1.79 (1.63 to 1.95) | 1.19 (1.13 to 1.24) |

Data are presented as the IRR (95% CI). Multilevel Poisson regression model adjusted for donor age and sex, population age and sex, ESRD rate standardized for age and sex, and geography (RUCA and state of residence).

P<0.001 for interaction of race and income in the combined model.

Adjusted Relative Incidence of LKD by Race

Table 4 shows the adjusted IRR of LKD in the African-American population compared with the white population overall and in each zip code quintile of median household income. Overall, the adjusted incidence of living donation was higher in the African-American population (IRR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.17 to 1.24). However, this effect varied by zip code quintile, with IRRs of 0.84 for Q1 (95% CI, 0.78 to 0.90), 1.01 for Q2 (95% CI, 0.94 to 1.09), 1.31 for Q3 (95% CI, 1.22 to 1.41), 1.50 for Q4 (95% CI, 1.39 to 1.62), and 1.87 for Q5 (95% CI, 1.73 to 2.02).

Table 4.

Adjusted relative incidence of LKD in African-American populations compared with white populations, stratified by zip code quintile of median household incomea

| Income Quintile | IRR for Living Donation in African Americans versus Whites |

|---|---|

| Total population | 1.20 (1.17 to 1.24) |

| Q1 (<$30,962) | 0.84 (0.78 to 0.90) |

| Q2 ($30,962–$37,314) | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.09) |

| Q3 ($37,315–$44,723) | 1.31 (1.22 to 1.41) |

| Q4 ($44,724–$56,580) | 1.50 (1.39 to 1.62) |

| Q5 (>$56,580) | 1.87 (1.73 to 2.02) |

Data are presented as the IRR (95% CI). Multilevel Poisson regression model adjusted for donor age and sex, population age and sex, ESRD rate standardized for age and sex, and geography (RUCA and state of residence).

P<0.001 for interaction of race and income in the combined model.

Discussion

There are currently >100,000 patients waiting for a kidney transplant in the United States.1 Despite concerted efforts, there has been only a modest increase in deceased donation in the United States over the last decade1 and this has not kept pace with the increasing demand for kidney transplantation. Identifying and addressing barriers to LKD is essential to reduce the gap between the supply of transplantable organs and demand for kidney transplantation.

In this analysis, we demonstrate a strong association between median household income and LKD in African-American and white populations after adjustment for age-, sex-, and race-related differences in ESRD, as well as geographical factors that may affect the likelihood of living donation. We also directly examined differences in living donation between the African-American and white populations and found higher age- and sex-adjusted rates of living donation in the African-American population (Figure 2). The higher likelihood of donation in African Americans persisted after adjustment for race-related differences in the incidence of ESRD but varied by income status (Table 4). The incidence of living donation was lower in the African-American population compared with the white population in zip codes with the lowest median household income (where the greatest numbers of African-American ESRD patients and their prospective donors reside). Meanwhile living donation was markedly higher among African Americans in higher-income zip codes (Table 4).

Our findings demonstrate the complex relationship between race, income, and LKD. The results also dispel the notion of a systematic cultural difference in the acceptance of LKD among African Americans, and point to the higher concentration of African-American ESRD patients and their prospective donors in lower-income populations as the major barrier to living donation in this group. These findings should inform new strategies to increase living donation among both the African-American and white populations.

There are a number of potential factors that may contribute to a lower likelihood of living donation among lower-income populations. Individuals lose the equivalent of 1 month’s salary to donate a kidney, including time away from work to complete the pretransplant evaluation, hospitalization, and postsurgical convalescence.6 In addition to lost income, there are significant out-of-pocket expenses, including travel, lodging, and childcare, that are borne by kidney donors.7 Therefore, low-income potential donors may simply not be able to afford the costs of kidney donation.

Household income is an important socioeconomic determinant of health, with several studies outlining inferior health outcomes in lower-income groups, including a higher risk of diabetes, coronary artery disease, obesity, psychiatric illness, and, importantly, ESRD.8–14 Furthermore, high-risk behaviors, such as tobacco and substance abuse, are more common in lower-income populations and social support networks may be poorer in these groups.12,14 As a result, prospective donors from low-income populations may frequently be found medically unsuitable to donate a kidney. Although we were unable to adjust for individual comorbidities in this population-level analysis, we did adjust for population-level ESRD rates to account for the higher prevalence of ESRD in lower-income and African-American populations. Although donor medical costs are covered by the transplant recipient’s insurance, health insurance coverage is limited to medical claims that are directly related to donation.6,15 Therefore, the cost of investigating and managing a medical problem identified during the work-up of a potential living donor is typically not covered by the recipient’s insurance. Similarly, postdonation medical claims deemed unrelated to the donor surgery may not be covered by the recipient’s insurance. Therefore, due to concerns that uninsured donors may not be able to access future medical care,16 some US transplant programs may refuse to accept uninsured potential donors.5 It is unknown what proportion of potential living donors from low-income populations fail to donate because of lack of health insurance. Unfortunately, information regarding donor health insurance is incompletely recorded in Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/United Network of Organ Sharing (OPTN/UNOS) data and we did not adjust for this in our analysis.15 Finally, the willingness of both ESRD patients and their prospective donors to participate in living donor transplantation may be lower in low-income populations. Mistrust of the health care system and a lack of knowledge about the safety of living donation have been associated with a reduced willingness to consider LKD17,18 and may be more prevalent in low-income populations.

Although most of the information regarding disparities in access to kidney transplantation in African Americans has focused on deceased donation,19–23 recent studies have shown that African Americans have a 46% lower odds of living donor transplantation.24 Patient-, system-, and donor-related factors may all contribute to the lower likelihood of living donor transplantation in African-American ESRD patients, but available studies have primarily focused on patient-level factors, many of which overlap with determinants of living donor transplantation in low-income populations.25–29 More recently, attention has shifted to transplant center–level practices that affect LKD.22 However, there has been less emphasis on donor-related factors in the published literature, and most of the available studies actually address recipient-related factors contributing to decreased identification of potential living donors in ethnic minority groups.30–32 Consistent with previous reports,5,6 we found that most living donations involve donors and recipients of the same race and income. Therefore, our results likely reflect a markedly reduced ability of lower-income African-American ESRD patients to successfully pursue living donor transplantation within their social networks. However, it is unclear whether this is driven by recipient factors (such as a reduced willingness to seek out potential donors), donor factors, or both. Efforts to decrease disparities in living donor transplantation among African Americans therefore must consider both patient- and donor-related factors.

Readers of this study should consider the strengths and limitations of this analysis. The study included all reported living kidney donors in the United States and included adjustment for most known confounders, including race-specific ESRD rates. All analyses were conducted at the population level and may not be applicable to individual donors. Non-African-American and non-white donors were excluded from this analysis; therefore, the results may not be directly applicable to those populations. The use of zip codes to determine median household income is frequent in the medical literature and assumes the same income for individuals living in a given zip code. This assumption may be incorrect, especially in metropolitan areas. Furthermore, median household income is only one of many indicators of socioeconomic status and may not directly relate to the financial status of an individual. The data on living donors spanned from 1998 to 2010, but we utilized 2000 Census data to assign median household income and determine population figures, not accounting for changes in the population over time. To examine the effect that this may have, a sensitivity analysis was conducted for the primary association of median household income and living donation rates using data from the 2010 Census, which revealed results consistent with our findings using the 2000 Census. Over 8000 donors were excluded from the analysis due to missing zip code data. Missing donors included a smaller proportion of white donors compared with the donors included in the analysis and we were unable to reliably capture other surrogates for income in these donors. Therefore, it is possible that these missing donors may have been skewed in terms of median household income. Within each race category, however, basic demographic characteristics of these donors were similar to the donors included in the analysis.

In conclusion, we found that median household income strongly associates with LKD in the United States, particularly in the African-American population. Furthermore, our findings dispel the notion of cultural resistance to living donation among African Americans, and instead suggest that socioeconomic factors underlie disparities in access to living donor transplantation among African-American patients with renal failure. Strategies to overcome socioeconomic barriers to LKD in lower-income populations may reduce racial disparities in access to living donor kidney transplantation.

Concise Methods

This study was performed with the approval of our local hospital research ethics board.

Data Source and Study Population

Figure 1 outlines the selection of the cohort. All living kidney donors in the United States reported to the OPTN/UNOS between 1998 and 2010 were identified (N=77,741). Race is self-reported in OPTN/UNOS data and race categories are identical to those recorded in the 2000 US Census. However, the US Census includes the Hispanic population within the white and African-American race categories, whereas OPTN/UNOS categorizes Hispanic ethnicity as separate from African-American or white race. For the purposes of this study, we restricted the analysis to non-Hispanic African-American donors and non-Hispanic white donors. After excluding 8403 donors with no recorded residential zip code and 11,442 donors with non-white and non-African-American race, 57,896 living kidney donors were identified for study inclusion. Non-African-American and non-white donors were excluded because many ethnic groups were represented, making it difficult to make inferences about any single ethnic group.

Population and Donor Characteristics

All 33,178 zip codes in the US Census were ranked by median household income and categorized into quintiles. For example, the lowest quintile (Q1) included all zip codes with median household incomes in the bottom 20% of all zip codes in the country (<$30,962).

The characteristics of the US population and living kidney donors were compared across zip code quintiles in both African-American and white populations. Continuous variables were reported as the mean ± SD or median (25th percentile, 75th percentile), whereas categorical variables were described using proportions. Group differences were determined using t tests, ANOVA, or the chi-squared test as appropriate.

Calculation of Living Donor Rate per Million Population

Using the total number of living donors in each zip code, we determined the living donor rate per million population within each zip code quintile after adjustment for age (categorized as 18–39, 40–59, and ≥60 years) and sex using the direct method1 (see the Supplemental Appendix for details). Separate living donor rates were determined for African-American and white populations within each zip code quintile.

Calculation of Adjusted IRRs for LKD by Median Household Income

Multilevel Poisson regression models were used to determine the age- and sex-adjusted relative incidence of living donation in each zip code quintile (Q2, Q3, Q4, and Q5) compared with the lowest quintile Q1 (IRR). To account for the possibility that income- and race-related differences in ESRD may affect living donation, IRRs were adjusted by the race-specific ESRD rate standardized for age and sex (see the Supplemental Appendix for detailed methods on calculation of standardized ESRD rates). Finally, to account for known and unknown geographical factors that may affect the likelihood of living donation, our analyses were clustered by state of residence and were adjusted by the rural-urban commuting area (RUCA) code.33,34RUCA codes are assigned to each US zip code based on markers of population density and were classified into the following groups: metropolitan (cities with a population of >50,000 and their associated suburban areas; RUCA, 1.0–3.9); micropolitan (towns or cities with a population of 10,000–50,000; RUCA, 4.0–6.0); and rural (towns with a population of <10,000; RUCA, >6.0). Separate analyses were performed in African-American and white populations. In addition, the interaction between race and median household income with the outcome of living donation was tested in a combined model.

Calculation of Adjusted IRR for LKD in African-American versus White Populations

Additional multilevel Poisson regression models were used to compare the incidence of living donation (IRR) in African-American versus white populations in each zip code quintile of median household income. These analyses were fully adjusted as described above. All analyses were performed using StataMP 11 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The data reported here were supplied by the United Network of Organ Sharing as the contractor for the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, as well as by the US Renal Data System. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the OPTN or the US Government. The data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System.

C.R. is funded by the Kidney Research Scientist Core Education and National Training Program.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2013010049/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.US Renal Data System: Annual Data Report: Atlas of End Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institute of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll G, Bello A, Browne S, Jadhav D, Klarenbach S, Gill J: Systematic review: Kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transplant 11: 2093–2109, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whiting JF, Kiberd B, Kalo Z, Keown P, Roels L, Kjerulf M: Cost-effectiveness of organ donation: Evaluating investment into donor action and other donor initiatives. Am J Transplant 4: 569–573, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waterman AD, Rodrigue JR, Purnell TS, Ladin K, Boulware LE: Addressing racial and ethnic disparities in live donor kidney transplantation: Priorities for research and intervention. Semin Nephrol 30: 90–98, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reese PP, Nair M, Bloom RD: Eliminating racial disparities in access to living donor kidney transplantation: How can centers do better? Am J Kidney Dis 59: 751–753, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill JS, Gill J, Barnieh L, Dong J, Rose C, Johnston O, Tonelli M, Klarenbach S: Income of living kidney donors and the income difference between living kidney donors and their recipients in the United States. Am J Transplant 12: 3111–3118, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaston RS, Danovitch GM, Epstein RA, Kahn JP, Matas AJ, Schnitzler MA: Limiting financial disincentives in live organ donation: A rational solution to the kidney shortage. Am J Transplant 6: 2548–2555, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akil L, Ahmad HA: Effects of socioeconomic factors on obesity rates in four southern states and Colorado. Ethn Dis 21: 58–62, 2011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark AM, DesMeules M, Luo W, Duncan AS, Wielgosz A: Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular disease: Risks and implications for care. Nat Rev Cardiol 6: 712–722, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudson CG: Socioeconomic status and mental illness: Tests of the social causation and selection hypotheses. Am J Orthopsychiatry 75: 3–18, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patzer RE, McClellan WM: Influence of race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status on kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 8: 533–541, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid JL, Hammond D, Driezen P: Socio-economic status and smoking in Canada, 1999-2006: Has there been any progress on disparities in tobacco use? Can J Public Health 101: 73–78, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sobal J, Stunkard AJ: Socioeconomic status and obesity: A review of the literature. Psychol Bull 105: 260–275, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams CT, Latkin CA: Neighborhood socioeconomic status, personal network attributes, and use of heroin and cocaine. Am J Prev Med 32[Suppl]: S203–S210, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ommen ES, Gill JS: The system of health insurance for living donors is a disincentive for live donation. Am J Transplant 10: 747–750, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibney EM, Doshi MD, Hartmann EL, Parikh CR, Garg AX: Health insurance status of US living kidney donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 912–916, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boulware LE, Ratner LE, Sosa JA, Cooper LA, LaVeist TA, Powe NR: Determinants of willingness to donate living related and cadaveric organs: Identifying opportunities for intervention. Transplantation 73: 1683–1691, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waterman AD, Barrett AC, Stanley SL, Rothstein M, Burroughs TE, Brennan DC, Hong BA: Why African-Americans are not pursuing living kidney donation. Am J Transplant 6(Suppl 2): 286, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexander GC, Sehgal AR: Barriers to cadaveric renal transplantation among blacks, women, and the poor. JAMA 280: 1148–1152, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ, Keogh JH, Noonan SJ, Armistead N, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, David-Kasdan JA, Carlson D, Fuller J, Marsh D, Conti RM: Racial disparities in access to renal transplantation–clinically appropriate or due to underuse or overuse? N Engl J Med 343: 1537–1544, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall YN, Choi AI, Xu P, O’Hare AM, Chertow GM: Racial ethnic differences in rates and determinants of deceased donor kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 743–751, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall EC, James NT, Garonzik Wang JM, Berger JC, Montgomery RA, Dagher NN, Desai NM, Segev DL: Center-level factors and racial disparities in living donor kidney transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 849–857, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bratton C, Chavin K, Baliga P: Racial disparities in organ donation and why. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 16: 243–249, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gore JL, Danovitch GM, Litwin MS, Pham PT, Singer JS: Disparities in the utilization of live donor renal transplantation. Am J Transplant 9: 1124–1133, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weng FL, Reese PP, Mulgaonkar S, Patel AM: Barriers to living donor kidney transplantation among black or older transplant candidates. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 2338–2347, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, Epstein AM: The effect of patients’ preferences on racial differences in access to renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 341: 1661–1669, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lunsford SL, Simpson KS, Chavin KD, Hildebrand LG, Miles LG, Shilling LM, Smalls GR, Baliga PK: Racial differences in coping with the need for kidney transplantation and willingness to ask for live organ donation. Am J Kidney Dis 47: 324–331, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waterman AD, Stanley SL, Covelli T, Hazel E, Hong BA, Brennan DC: Living donation decision making: Recipients’ concerns and educational needs. Prog Transplant 16: 17–23, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boulware LE, Hill-Briggs F, Kraus ES, Melancon JK, Senga M, Evans KE, Troll MU, Ephraim P, Jaar BG, Myers DI, McGuire R, Falcone B, Bonhage B, Powe NR: Identifying and addressing barriers to African American and non-African American families’ discussions about preemptive living related kidney transplantation. Prog Transplant 21: 97–104, quiz 105, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Lin JK, Kaplan B, Howard RJ: Increasing live donor kidney transplantation: A randomized controlled trial of a home-based educational intervention. Am J Transplant 7: 394–401, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Kaplan B, Howard RJ: Patients’ willingness to talk to others about living kidney donation. Prog Transplant 18: 25–31, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boulware LE, Hill-Briggs F, Kraus ES, Melancon JK, McGuire R, Bonhage B, Senga M, Ephraim P, Evans KE, Falcone B, Troll MU, Depasquale N, Powe NR: Protocol of a randomized controlled trial of culturally sensitive interventions to improve African Americans’ and non-African Americans’ early, shared, and informed consideration of live kidney transplantation: The Talking About Live Kidney Donation (TALK) Study. BMC Nephrol 12: 34, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Axelrod DA, Guidinger MK, Finlayson S, Schaubel DE, Goodman DC, Chobanian M, Merion RM: Rates of solid-organ wait-listing, transplantation, and survival among residents of rural and urban areas. JAMA 299: 202–207, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tonelli M, Klarenbach S, Rose C, Wiebe N, Gill J: Access to kidney transplantation among remote- and rural-dwelling patients with kidney failure in the United States. JAMA 301: 1681–1690, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.