Abstract

Alterations in expression of a cannabinoid receptor (CNR1, CB1), and of fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) that degrades endogenous ligands of CB1, may contribute to the development of addiction. The 385C>A in the FAAH gene and six polymorphisms of CNR1 were genotyped in former heroin addicts and control subjects (247 Caucasians, 161 Hispanics, 179 African Americans and 19 Asians). In Caucasians, long repeats (≥14) of 18087–18131 (TAA)8–17 were associated with heroin addiction (P = 0.0102). Across three ethnicities combined, a highly significant association of long repeats with heroin addiction was found (z = 3.322, P = 0.0009). Point-wise significant associations of allele 1359A (P= 0.006) and genotype 1359AA (P= 0.034) with protection from heroin addiction were found in Caucasians. Also in Caucasians, the genotype pattern, 1359G>A and −6274A>T, was significantly associated with heroin addiction experiment wise (P= 0.0244). No association of FAAH 385C>A with heroin addiction was found in any group studied.

Keywords: drug addiction, SNPs, CB1, CNR1, FAAH, haplotypes

Introduction

The endogenous opioid and cannabinoid systems are central in mediating and modulating neurophysiological responses to several drugs of abuse. Central cannabinoid receptor or cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1, CNR1) is found predominantly in the brain and is expressed in multiple regions, including those important for drug reward.1–3 A second type of cannabinoid receptors, CNR2, has been found in immune cells as well as in the spleen4 and in brain-stem neurons.5 Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol, the principal psychoactive component of marijuana, is an agonist of both CNR1 and CNR2 (for review see Howlett et al.6). N-arachidonoyl ethanolamine (anandamide)7 and 2-arachydonoylglycerol8 are endogenous ligands of the CNR1.

Fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) is important in the inactivation of some endogenous ligands of CNR1, including anandamide and 2-arachydonoylglycerol (for review see Deutsch et al.9 and McKinney and Cravatt10). Endogenous brain levels of anandamide and other amides of fatty acids are increased up to 15-fold in FAAH knockout mice.11 The missense substitution 385C>A in FAAH converts a conserved proline residue to threonine (129P>T) that results in increased sensitivity of this enzyme to proteolytic degradation12 and reduced FAAH expression and activity as measured in lymphocytes from human subjects.13 These abnormalities in the properties of the 385A variant of FAAH are considered to be a potential link between functional abnormalities in the endogenous cannabinoid system and drug abuse and dependence, and have been reported to be an important risk factor for problem drug use and street drug use.12

Precipitation of an abstinence syndrome in cannabinoid-dependent rats by blockade of opioid receptors by naloxone14 indicates cross-interaction between cannabinoid and opioid systems in neuronal pathways. In animal models, acute administration of SR141716A (Rimonabant hydrochloride), a selective central CNR1 antagonist, blocked heroin self-administration in rats, as well as morphine-induced place preference and morphine self-administration in mice.15 A more recent study showed that motivational and reinforcing effects of heroin are mediated by activation of CB1 receptors.16 In CNR1 knockout mice, morphine did not modify dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens in areas of the brain involved in the reinforcing effects of morphine.17 Mice lacking CNR1 failed to self-administer morphine, but did self-administer nicotine, cocaine and amphetamines.18

In humans, several polymorphic sites including the triplet polymorphism 18087–18131(TAA)8–17 have been identified in the CNRl gene19–21, which is located on chromosome 6 at 6ql4–ql5.22 Earlier studies of a possible association of 18087–18131(TAA)8–17 with neuropsychiatric diseases were inconclusive. No association of this variant with mood disorders23 or with schizophrenia24 was found in a Taiwanese population, although in a Japanese cohort 18087–18131(TAA)8–17 was shown to confer a susceptibility for schizophrenia, especially of the hebephrenic type.25 In Germans, no association with schizophrenia of this polymorphism, rs6454674, or rsl049353 was found.26 This repeat polymorphism has been reported to be associated with diverse intravenous injection in non-Hispanic Caucasians,27 but not with heroin abuse in Han Chinese.28

For this study, we selected high-frequency single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from the promoter regions of the CNR1 gene that were previously shown to be in association with polysubstance abuse.21 Another SNP chosen for this study, 1359G> A, is located in the coding region of the gene.

In the CNR1 gene, we found a significant association of long repeats (≥14) of 18087–18131(TAA)8–17 with heroin addiction in Caucasians and an association of long repeats with heroin addiction across three ethnicities combined. Also in Caucasians only, we found associations of allele 1359A and genotype 1359AA with protection from heroin addiction.

Materials and methods

Study subjects: recruitment and diagnostic procedures

For this study, African American, Caucasian, Hispanic and Asian unrelated subjects were recruited between 7 February 1995 and 31 May 2005 in New York City. The Rockefeller University Hospital Institutional Review Board-approved informed consent for genetic studies was obtained from all subjects. Subjects provided self-reported ethnicity.

Individuals were included in the former heroin-addicted group if they met Federal regulations for admission to methadone maintenance treatment: more than 1 year of daily multiple dose self-administration of heroin or other illicitly used opiates;29 these criteria are significantly more stringent than those of a diagnosis of heroin addiction by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition criteria30 and are quantitatively defined subphenotype of opiate addiction. Subjects with prior or continuing codependence on other illicit drugs or alcohol were not excluded as long as opiate dependence was the primary diagnosis.

To increase the precision and provide more detailed characterization of the subjects involved in our research, we characterized a subgroup of our subjects, including both former heroin-addicted and control subjects recruited between 26 June 2000 and 31 May 2005, by the Kreek-McHugh—Schluger–Kellogg scale, which quantifies frequency, mode, amount and duration of self-exposure to opiates, cocaine, alcohol and tobacco.31

Exclusion criteria for the control subjects entering the study were as previously published.32 Control subjects had no history of any extended period of drug or alcohol abuse or dependence. Subjects who used cannabis >12 days during the previous 30 days were excluded from the control group. Use of nicotine or caffeine was not an exclusion criterion for this group. Subjects with each parent from a different ethnic group (mixed ethnicity) were excluded from the study. Asians were excluded from the association analysis due to low numbers.

CNR1 Genotyping

DNA was extracted from blood specimens using a salting-out procedure followed by ethanol precipitation and stored at −80 °C until further use. In a search for novel polymorphisms, PCR amplification of the coding region of the human CNR1 gene in a subgroup of 205 DNA samples (including 30 former heroin-addicted and 48 control Caucasians, 51 former heroin-addicted and 16 control Hispanics, 18 former heroin-addicted and 23 control African Americans and 19 others) was performed using the following two primer pairs: 5′-TTCGGCTTATTTGTTTTCCCTCCTC (Forward 1), 5′-CAT CAATGTGTGGGAAAATG (Reverse 1), 5′-CAGCCATCGAC AGGTACATA (Forward 2), 5′-CACCTTTTCATTGAGCATGG (Reverse 2), resulting in two overlapping fragments (909 and 910 nucleotides long, based on GenBank accession no. GBPRI 8217458). All oligonucleotide primers were from Midland Certified Reagent (Midland, TX, USA). Numbering of the polymorphism position is based upon the previously reported system that gives value +1 to the first nucleotide of the AUG initiation codon. PCR amplifications of 5–10 ng of DNA using Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were performed on GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using step-down procedure: incubation at 95 °C for 5 min, then 3 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 66 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min, then 3 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 63 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min, then 3 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min, then 3 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 57 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min, then 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 54 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min, then incubation at 72 °C for 7 min. Amplified PCR fragments were purified and subsequently sequenced at the Rockefeller University DNA Sequencing Resource Center. Electropherograms were aligned using SeqMan 5.00 alignment software (DNASTAR 1998, Madison, WI, USA) and were analyzed by visual examination independently by two investigators blind to diagnostic characterization (phenotypes). Novel SNPs identified in this study were confirmed by replicating the PCR amplification and subsequently sequenced again.

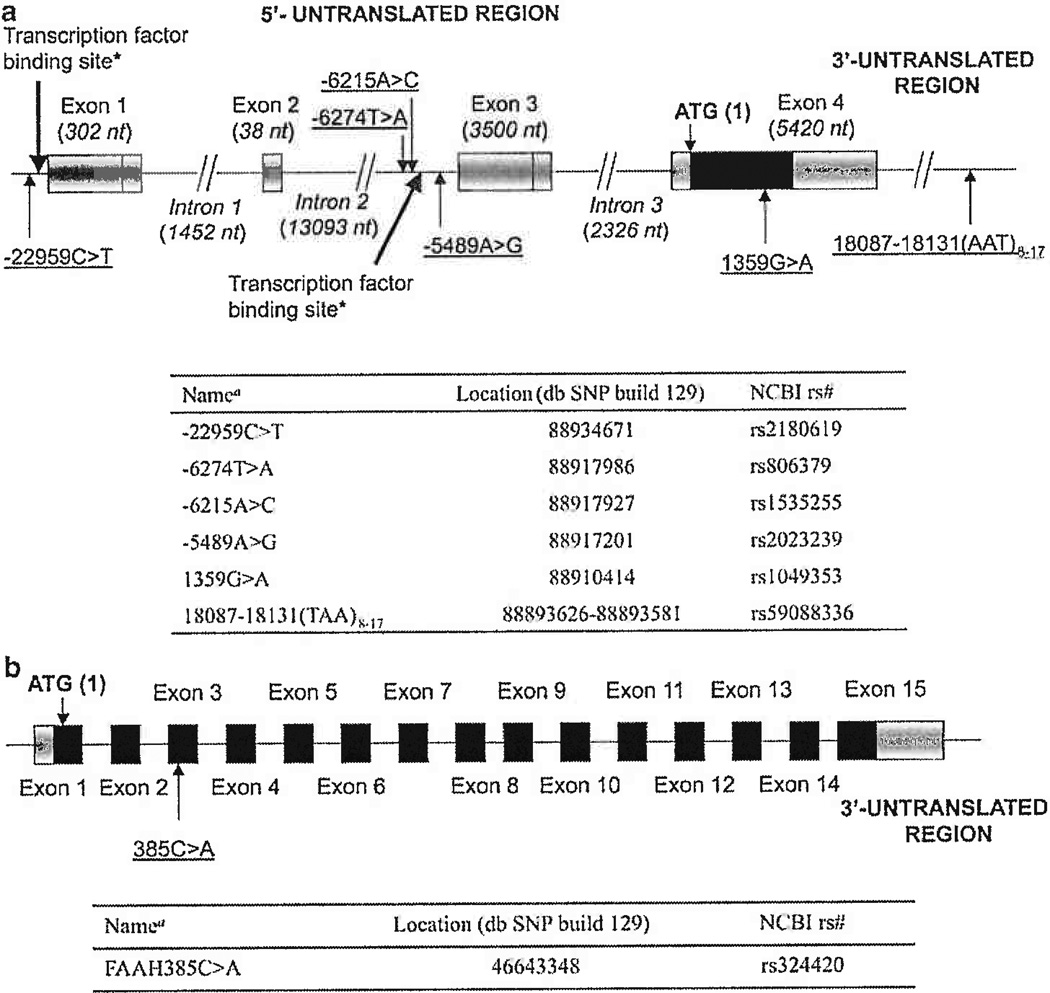

Genotyping by 5′ Fluorogenic Exonuclease Assay (TaqMan) was performed in 5 µl volumes in 384-well plates using Platinum quantitative PCR SuperMix-UDG (Invitrogen) and 1–10 ng of DNA per reaction. Amplification reactions for genotyping of polymorphisms −22959G>A, −6274A>T, −6215T>G, −5489T>C, 1359G>A of the CNR1 gene (Figure 1) and 385C>A of the FAAH gene were carried out on a GeneAmp PCR system 9700 and the dual 384-well sample block module (Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer’s protocol. To genotype polymorphisms in the CNR1 gene, we used a set of primers and probes developed by Uhl’s group21; and to genotype polymorphisms in the FAAH gene, we used the minor groove binder-bound probes 5′-TCAGGCCCCAAGGC, 5′-fluorescein amidite labeled and 5′-TCAGGCCACAAGGC, VIC labeled, and oligonucleotide primers 5′-CCTGGGAAGTGAACAAAGGG, forward and 5′-CCAAAATGACCCAAGATGCA, reverse. All custom TaqMan probes were purchased from Applied Biosystems. Upon completion of PCR cycling, genotype analysis was performed on the ABI Prism 7900 sequence detection system using SDS 2.2 software (Applied Biosystems). The results of TaqMan genotyping were confirmed by direct sequencing of selected samples (one heterozygote and two homozygote groups of eight samples per group for each polymorphism) using the same primers.

Figure 1.

(a) Location of the polymorphisms of CNR1 gene selected for these studies in chromosome 6. *Transcription factor binding sites identified by Uhl’s group21 and shown in bold arrows; aNumbering of the polymorphism position starts with the first nucleotide of AUG initiation codon as 1; bases that belong to the coding region have positive values; nt, nucleotides; NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/); db SNP build 129 at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP. (b) Location of the polymorphism 385C > A of FAAH gene selected for these studies in chromosome 1.

To genotype 18087–18131(TAA)8–17 repeats, we performed PCR amplifications in two replicates: first, using oligonucleotide primers 5′-GCTGCTTCTGTTAACCCTGC labeled with 5′-fluorescein amidite and 5′-TACATCTCCGTGTGATGTTCC (yielding PCR product with fluorescently labeled forward strand) and second, using 5′-GCTGCTTCTGTTAACCCTGC and 5′-TACATCTCCGTGTGATGTTCC labeled with 5′-fluorescein amidite (yielding PCR product with fluorescently labeled reverse strand). The amplification was performed using Platinum DNA polymerase in 5 µ1 volumes using a previously described step-down protocol (see above). Upon the completion of cycling, the reaction mixture was diluted with 20 µ1 of water and 0.5 of the resulting solution was used for fragment analysis on ABI 3700 and ABI 3730xl DNA analyzers (Applied Biosystems). The data were analyzed using GeneMapper 3.7 (Applied Biosystems) software by two independent researchers. The data provided by the ABI 3700 were consistent with the data provided by the ABI 3730xl with 3.14% error. The only repeated inconsistency between results provided by the two instruments was absence of the 9-triplet allele in any readings provided by the ABI 3730xl (1.24% error attributed to this discrepancy). All other inconsistencies were random. The results of fragment analysis were confirmed by regular sequencing of 38 samples, including 13 samples in which a 9-triplet allele was found using the ABI 3700.

Statistical analysis

Genotypic, multilocus genotype pattern (MLGP), and allelic association analyses were carried out between cases and controls, separately for each ethnicity. Likelihood ratio χ2-tests33,34 were applied for significance testing in the resulting 2 × n contingency tables, where n is the number of alleles or genotypes. In this study, the likelihood ratio χ2-test was used rather than the Pearson χ2-test because it is less sensitive to small sample sizes.

Separate Bonferroni correction factors for multiple testing were applied for different tables presented in our study. In allelic and genotypic association tests (Table 1), data were corrected for the number of SNPs studied. In allelic and genotypic association of microsatellite repeats (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S3, respectively) the data were corrected for the number of individual alleles or genotypes analyzed in each ethnic group separately. In MLGP tests (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S4), data were corrected for the number of individual patterns analyzed in each ethnic group separately.

Table 1.

Allelic and genotypic association of the polymorphisms of the CNR1 and FAAH genes with heroin addiction

| (A) Polymorphism −22959C> T (CNR1) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity |

Group of subjects |

Number of alleles C (frequency) |

Number of alleles T (frequency) |

P, Allele test (odds ratio) |

Genotype CC (frequency) |

Genotype CT (frequency) |

Genotype TT (frequency) |

P, Genotype test |

| African American | Controls | 113 (0.681) | 53 (0.319) | 0.624 (1.19) | 41 (0.434) | 31 (0.373) | 11 (0.133) | 0.890 |

| Former heroin addicted | 126 (0.656) | 66 (0.344) | 44 (0.458) | 38 (0.396) | 14 (0.146) | |||

| Caucasian | Controls | 92 (0.411) | 132 (0.589) | 0.993 (0.99) | 19 (0.170) | 54 (0.482) | 39 (0.348) | 0.625 |

| Former heroin addicted | 111 (0.411) | 159 (0.589) | 27 (0.200) | 57 (0.422) | 51 (0.378) | |||

| Hispanic | Controls | 40 (0.541) | 34 (0.459) | 0.501 (1.19) | 8 (0.216) | 24 (0.649) | 5 (0.135) | 0.018 |

| Former heroin addicted | 123 (0.496) | 125 (0.504) | 37 (0.298) | 49 (0.395) | 38 (0.306) | |||

| (B) Polymorphism −6274T>A (CNR1) | ||||||||

| Ethnicity |

Group of subjects |

Number of alleles T (frequency) |

Number of alleles A (frequency) |

P, Allele test (odds ratio) |

Genotype TT (frequency) |

Genotype TA (frequency) |

Genotype AA (frequency) |

P, Genotype test |

| African American | Controls | 79 (0.476) | 87 (0.524) | 0.951 (0.99) | 17 (0.205) | 45 (0.542) | 21 (0.253) | 0.858 |

| Former heroin addicted | 92 (0.479) | 100 (0.521) | 18 (0.186) | 56 (0.583) | 22 (0.229) | |||

| Caucasian | Controls | 115 (0.514) | 109 (0.486) | 0.845 (0.97) | 27 (0.241) | 61 (0.544) | 24 (0.214) | 0.158 |

| Former heroin addicted | 141 (0.522) | 129 (0.478) | 42 (0.311) | 57 (0.422) | 36 (0.267) | |||

| Hispanic | Controls | 37 (0.500) | 37 (0.500) | 0.715 (0.91) | 8 (0.216) | 21 (0.568) | 8 (0.216) | 0.725 |

| Former heroin addicted | 130 (0.524) | 118 (0.476) | 34 (0.274) | 62 (0.500) | 28 (0.226) | |||

| (C) Polymorphism −6215A>C (CNR1) | ||||||||

| Ethnicity |

Group of subjects |

Number of alleles A (frequency) |

Number of alleles C (frequency) |

P, Allele test (odds ratio) |

Genotype AA (frequency) |

Genotype AC (frequency) |

Genotype CC (frequency) |

P, Genotype test |

| African American | Controls | 118 (0.711) | 48 (0.289) | 0.789 (1.06) | 42 (0.506) | 34 (0.410) | 7 (0.084) | 0.964 |

| Former heroin addicted | 134 (0.698) | 58 (0.302) | 47 (0.490) | 40 (0.417) | 9 (0.094) | |||

| Caucasian | Controls | 193 (0.862) | 31 (0.138) | 0.448 (1.21) | 82 (0.732) | 29 (0.259) | 1 (0.010) | 0.474 |

| Former heroin addicted | 226 (0.837) | 44 (0.143) | 95 (0.704) | 36 (0.267) | 4 (0.030) | |||

| Hispanic | Controls | 63 (0.851) | 11 (0.149) | 0.160 (1.63) | 26 (0.703) | 11 (0.297) | 0 | 0.050 |

| Former heroin addicted | 193 (0.778) | 55 (0.222) | 80 (0.645) | 33 (0.266) | 11 (0.089) | |||

| (D) Polymorphism −5489A>G (CNR1) | ||||||||

| Ethnicity |

Group of subjects |

Number of alleles A (frequency) |

Number of alleles G (frequency) |

P, Allele test (odds ratio) |

Genotype AA (frequency) |

Genotype AG (frequency) |

Genotype GG (frequency) |

P, Genotype test |

| African American | Controls | 118 (0.711) | 48 (0.289) | 0.873 (1.04) | 43 (0.518) | 32 (0.386) | 8 (0.096) | 0.841 |

| Former heroin addicted | 135 (0.703) | 57 (0.298) | 47 (0.490) | 41 (0.427) | 8 (0.083) | |||

| Caucasian | Controls | 193 (0.862) | 31 (0.138) | 0.448 (1.21) | 82 (0.732) | 29 (0.259) | 1 (0.009) | 0.474 |

| Former heroin addicted | 226 (0.837) | 44 (0.143) | 95 (0.704) | 36 (0.267) | 4 (0.030) | |||

| Hispanic | Controls | 64 (0.865) | 10 (0.135) | 0.106 (1.78) | 27 (0.730) | 10 (0.270) | 0 | 0.050 |

| Former heroin addicted | 194 (0.782) | 54 (0.218) | 81 (0.653) | 32 (0.258) | 11 (0.089) | |||

| (E) Polymorphism 1359G>A (CNR1) | ||||||||

|

Ethnicity |

Group of subjects |

Number of alleles G (frequency) |

Number of alleles A (frequency) |

P, Allele test (odds ratio) |

Genotype GG (frequency) |

Genotype GA (frequency) |

Genotype AA (frequency) |

P, Genotype test |

| African American | Controls | 154 (0.928) | 12 (0.072) | 0.982 (1.01) | 72 (0.867) | 10 (0.120) | 1 (0.012) | 0.853 |

| Former heroin addicted | 178 (0.927) | 14 (0.073) | 84 (0.875) | 10 (0.104) | 2 (0.021) | |||

| Caucasian | Controls | 170 (0.759) | 54 (0.241) | 0.006a (0.53) | 67 (0.598) | 36 (0.321) | 9 (0.080) | 0.034 |

| Former heroin addicted | 231 (0.856) | 39 (0.144) | 100 (0.741) | 31 (0.230) | 4 (0.030) | |||

| Hispanic | Controls | 63 (0.851) | 11 (0.149) | 0.857 (1.07) | 28 (0.757) | 7 (0.189) | 2 (0.054) | 0.284 |

| Former heroin addicted | 209 (0.843) | 39 (0.157) | 87 (0.702) | 35 (0.282) | 2 (0.016) | |||

| (F) Polymorphism 385C>A (FAAH) | ||||||||

| Ethnicity |

Croup of subjects |

Number of alleles C (frequency) |

Number of alleles A (frequency) |

P, Allele test (odds ratio) |

Genotype CC (frequency) |

Genotype CA (frequency) |

Genotype AA (frequency) |

P, Genotype test |

| African American | Controls | 102 (0.614) | 64 (0.386) | 0.617 (1.11) | 35 (0.422) | 32 (0.386) | 16 (0.193) | 0.521 |

| Former heroin addicted | 113 (0.589) | 79 (0.411) | 34 (0.354) | 45 (0.469) | 17 (0.177) | |||

| Caucasian | Controls | 174 (0.776) | 50 (0.224) | 0.403 (0.83) | 68 (0.607) | 38 (0.339) | 6 (0.054) | 0.597 |

| Former heroin addicted | 218 (0.807) | 52 (0.193) | 87 (0.644) | 44 (0.326) | 4 (0.030) | |||

| Hispanic | Controls | 51 (0.689) | 23 (0.311) | 0.735 (0.91) | 16 (0.432) | 19 (0.514) | 2 (0.054) | 0.254 |

| Former heroin addicted | 176 (0.710) | 72 (0.290) | 65 (0.524) | 46 (0.371) | 13 (0.105) | |||

Significant association (P<0.05) is shown in bold italic.

P = 0.036 after correction for multiple testing (correction factor is 6, the number of SNPs tested).

Table 2.

Allelic association of microsatellite repeats 18087–18131 (AAT)8–17 of the CNR1 gene with heroin addiction

| Ethnicities |

Number of repeats |

Number of alleles (frequency) |

Test of alleles of individual lengths |

Logistic regression test: OR, (95%CI), P |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Former heroin addicted | χ2 | P | |||

| African American | 10 | 19 (0.114) | 15 (0.078) | 1.3635 | 0.2429 | 1.12, |

| 11 | 70 (0.422) | 79 (0.411) | 0.0383 | 0.8448 | (0.97–1.28), | |

| 12 | 37 (0.223) | 32 (0.167) | 1.8044 | 0.1792 | 0.1142 | |

| 13 | 17 (0.102) | 24 (0.125) | 0.4505 | 0.5021 | ||

| 14 | 4 (0.024) | 18 (0.094) | 8.1751 | 0.0042a | ||

| 15 | 19 (0.114) | 20 (0.104) | 0.0970 | 0.7555 | ||

| Rareb | 0 (0) | 4 (0.021) | ||||

| Total | 166 | 192 | ||||

| Total short (8–13) | 143 (0.861) | 151 (0.786) | 3.4592 | 0.0629c (OR=1.69) | ||

| Total long (14–17) | 23 (0.139) | 41 (0.214) | ||||

| Caucasian | 11 | 65 (0.290) | 50 (0.185) | 7.5333 | 0.0061d | 1.12, |

| 12 | 13 (0.058) | 8 (0.030) | 2.4220 | 0.1196 | (1.02–1.23), | |

| 13 | 35 (0.156) | 42 (0.156) | 0.0004 | 0.9831 | 0.0213 | |

| 14 | 44 (0.196) | 58 (0.215) | 0.2532 | 0.6148 | ||

| 15 | 57 (0.254) | 88 (0.326) | 3.0343 | 0.0815 | ||

| Rareb | 10 (0.045) | 24 (0.089) | ||||

| Total | 224 | 270 | ||||

| Total short (8–13) | 118 (0.527) | 111 (0.411) | 6.5962 | 0.0102c (OR = 1.60) | ||

| Total long (14–17) | 106 (0.473) | 159 (0.589) | ||||

| Hispanic | 11 | 26 (0.351) | 75 (0.302) | 0.6251 | 0.4292 | 1.08, |

| 12 | 6 (0.081) | 11 (0.044) | 1.3978 | 0.2371 | (0.94–1.25), | |

| 13 | 13 (0.176) | 43 (0.173) | 0.0021 | 0.9637 | 0.2649 | |

| 14 | 10 (0.135) | 38 (0.153) | 0.1499 | 0.6987 | ||

| 15 | 13 (0.176) | 59 (0.238) | 1.3236 | 0.2499 | ||

| Rareb | 6 (0.081) | 22 (0.089) | ||||

| Total | 74 | 248 | ||||

| Total short (8–13) | 49 (0.662) | 143 (0.577) | 1.7591 | 0.1847c (OR = 1.44) | ||

| Total long (14–17) | 25 (0.338) | 105 (0.423) | ||||

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Significant association (P<0.05) is shown in bold.

Association of a 14-triplet repeat with vulnerability to develop heroin addiction was found in African Americans, corrected for multiple testing P=0.0252 (correction factor is 6, the number of alleles studied in African Americans).

Alleles with frequency <5% in each of the two treatment groups (controls, former heroin addicts) were combined into a ‘rare’ group.

When all three ethnic/cultural groups were considered together to determine whether the long repeats are associated with vulnerability to develop heroin addiction, specific calculations documented that the two-sided significance level associated with the resulting Z= 3.322 is P = 0.0009 (see Results).

Association of an 11-triplet repeat with protection from the vulnerability to develop heroin addiction was found in Caucasians, corrected for multiple testing P = 0.0305 (correction factor is 5, the number of alleles studied in Caucasians).

Table 3.

Results of the MLGP analysis of SNPs –22959C>T, –6274T>A, –6215A>C, –5489A>G and 1359G>A of the CNR1 gene

| Ethnicities | MLGP | Controls | Former heroin addicted | Total | χ2 | d.f. | P | OR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African American | CT-AT-CA-GA-GG | 13 | 14 | 27 | 0.0404 | 1 | 0.8406 | 0.93 (0.43–1.99) |

| CC-AT-AA-AA-GG | 10 | 11 | 21 | 0.0149 | 1 | 0.9027 | 0.95 (0.40–2.24) | |

| CC-AT-CA-GA-GG | 6 | 12 | 18 | 1.3983 | 1 | 0.2370 | 1.85 (0.67–4.76) | |

| CT-TT-AA-AA-GG | 8 | 10 | 18 | 0.0299 | 1 | 0.8628 | 1.10 (0.43–2.74) | |

| CC-AA-CC-GG-GG | 4 | 6 | 10 | 0.1742 | 1 | 0.6764 | 1.33 (0.39–4.38) | |

| TT-AT-AA-AA-GG | 4 | 6 | 10 | 0.1742 | 1 | 0.6764 | 1.33 (0.39–4.38) | |

| CC-AA-CA-GA-GG | 4 | 5 | 9 | 0.0141 | 1 | 0.9054 | 1.09 (0.31–3.80) | |

| Rarea | 34 | 32 | 66 | |||||

| Total | 83 | 96 | 179 | 2.3468 | 7 | 0.9382 | ||

| Caucasian | CT-AT-AA-AA-GG | 12 | 15 | 27 | 0.0099 | 1 | 0.9207 | 1.04 (0.47–2.29) |

| CT-TT-AA-AA-GG | 7 | 14 | 21 | 1.3675 | 1 | 0.2423 | 1.74 (0.69–4.40) | |

| TT-AA-AA-AA-GG | 8 | 13 | 21 | 0.4923 | 1 | 0.4829 | 1.39 (0.57–3.38) | |

| TT-AT-AA-AA-GG | 10 | 8 | 18 | 0.8126 | 1 | 0.3674 | 0.64 (0.25–1.64) | |

| CC-TT-AA-AA-GG | 3 | 12 | 15 | 4.4829 | 1 | 0.0342 | 3.57 (1.04–12.0) | |

| TT-TT-AA-AA-GG | 3 | 11 | 14 | 3.6814 | 1 | 0.0550 | 3.23 (0.94–11.0) | |

| Rarea | 69 | 62 | 131 | |||||

| Total | 112 | 135 | 247 | 12.3906 | 6 | 0.0538 | ||

| Hispanic | CT-AT-AA-AA-GG | 7 | 13 | 20 | 1.7138 | 1 | 0.1905 | 0.50 (0.18–1.33) |

| CT-TT-AA-AA-GG | 4 | 9 | 13 | 0.4552 | 1 | 0.4999 | 0.65 (0.19–2.10) | |

| TT-AT-AA-AA-GG | 2 | 9 | 11 | 0.1616 | 1 | 0.6877 | 1.37 (0.32–5.85) | |

| CC-AT-AA-AA-GG | 4 | 6 | 10 | 1.5468 | 1 | 0.2136 | 0.42 (0.12–1.47) | |

| CC-TT-AA-AA-GG | 2 | 8 | 10 | 0.0552 | 1 | 0.8143 | 1.21 (0.27–5.30) | |

| CT-AT-CA-GA-GG | 3 | 7 | 10 | 0.2799 | 1 | 0.5968 | 0.68 (0.18–2.53) | |

| Rarea | 15 | 72 | 87 | |||||

| Total | 37 | 124 | 161 | 5.8051 | 6 | 0.4454 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; d.f., degree of freedom; MLGP, multilocus genotype pattern; OR, odds ratio.

Significant association (P<0.05) is shown in bold.

MLGPs with frequency <5% were combined into a ‘rare’ group.

When analyzing association of genotype pairs of polymorphisms of the CNR1 and the FAAH genes with heroin addiction (Table 4), permutation testing was performed to account for the fact that multiple tests were run.35 This consisted of randomizing case–control status and rerunning the analysis for the six SNPs. From each of the 50 000 permutations, the maximum χ2-value from the six tests was obtained. Then the original χ2-value for each of the six SNPs was compared to this distribution of maximum χ2-values. The number of randomized maximum χ2-values greater than the original χ2-value divided by the total number of permutation samples was taken as an estimate for the experiment-wise P-value.

Table 4.

| A Results of association tests of genotype pairs consisting of polymorphisms of CNR1 and FAAH genes analyzed in this study with heroin addiction in Caucasians | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | SNP1 | SNP2 | χ2 | Pa |

| 1 | 1359G>A (CNR1) | −6274T>A (CNR1) | 23.2123 | 0.0244 |

| 2 | −6274T>A (CNR1) | 385C>A (FAAH) | 19.7695 | 0.0841 |

| 3 | −5489A>G (CNR1) | 1359G> A (CNR1) | 14.2189 | 0.4370 |

| 4 | −6215A>C (CNR1) | 1359G> A (CNR1) | 14.2189 | 0.4370 |

| 5 | −5489A>G (CNR1) | 385C> A (FAAH) | 13.2277 | 0.5435 |

| 6 | −6215A>C (CNR1) | 385C>A (FAAH) | 13.2277 | 0.5435 |

| 7 | −22959C>T (CNR1) | −6274T> A (CNR1) | 11.1481 | 0.7718 |

| 8 | 1359G>A (CNR1) | 385C> A (FAAH) | 10.2626 | 0.8558 |

| 9 | −22959C>T (CNR1) | 1359G> A (CNR1) | 8.2223 | 0.9711 |

| 10 | −22959C>T (CNR1) | −5489A>G (CNR1) | 7.7294 | 0.9834 |

| 11 | −22959C>T (CNR1) | −6215A>C (CNR1) | 7.7294 | 0.9834 |

| 12 | −5489A>G (CNR1) | −6274T>A (CNR1) | 5.3569 | 0.9997 |

| 13 | −6215A>C (CNR1) | −6274T>A (CNR1) | 5.3569 | 0.9997 |

| 14 | −22959C>T (CNR1) | 385C> A (FAAH) | 3.6087 | 1.0000 |

| 15 | −5489A>C (CNR1) | −6215A>C (CNR1) | 1.4936 | 1.0000 |

| B Distribution of genotype patterns of the CNR1 gene formed by SNPs −6274T> A and 1359G> A in addicted and control groups of a Caucasian population | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotypes 1359C>A | Number of joint genotypes found | |||||||||

| Genotypes −6274T>A | AA | GA | GG | Total | ||||||

| AA | AT | TT | AA | AT | TT | AA | AT | TT | ||

| Controls | 0 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 15 | 13 | 16 | 38 | 13 | 112 |

| Former heroin addicted | 0 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 21 | 4 | 30 | 33 | 37 | 135 |

| OR | 0.295 | 0.828 | 0.605 | 1.191 | 0.233 | 1.714 | 0.630 | 2.875 | ||

Significant association (P<0.05) is shown in bold.

P-values are corrected for multiple testing within this table.

For the microsatellite marker, in addition to testing for allele frequency differences between case and control individuals, we took the sum of the two allele lengths in an individual as that individual’s genotype and used the resulting n ‘genotypes’ in a χ2-analysis as outlined above. Also for the microsatellite marker, an unadjusted logistic regression analysis was conducted where treatment group status was the response and length of repeat was the explanatory variable. In this model, an exponential beta-weight is equivalent to the odds increase in susceptibility attributable to each unit increase in length. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was tested in cases and controls for each marker with likelihood ratio χ2, separately for each ethnicity. If any group of individuals deviated significantly from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, genotypes were scrutinized for errors and TaqMan results were reexamined. Plots of linkage disequilibrium were generated with control samples using the program Haploview 4.0 (Cambridge, MA, USA).36

Results

Demographic details of the study subjects are shown in Table 5. In control individuals, overall allele frequencies were significantly different among the four ethnicities for each marker tested except −6274A>T (Supplementary Table S1). In Supplementary Table S2 no significant deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium were found in controls, but in cases significant deviations were observed for 1359G>A in African Americans and for −2959C>T, −6215A>C and −5489A>G in Hispanics, which might be an indication of an association. Allelic tests showed significant association of minor 1359A located in the coding region of the CNR1 gene with protection from addiction in Caucasians (P = 0.006, odds ratio (OR) =0.53, Table 1E). At the genotype level, a significant association with disease, for example, vulnerability to develop heroin addiction, was found for 1359GG in Caucasians (P = 0.034, Table 1E). Similarly, at the genotype level a significant association with disease was found for −22959TT in Hispanics (P= 0.018, Table 1A). No association of polymorphism 385C>A in the FAAH gene with heroin addiction was found either in genotype or allele tests (Table 1F).

Table 5.

Demography of the study subjects

| Ethnicity | Number of subjects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Heroin addicted |

Total subjects |

|||||

| Female | Male | Total | Female | Male | Total | ||

| African American | 37 | 46 | 83 | 43 | 53 | 96 | 179 |

| Caucasian | 52 | 60 | 112 | 47 | 88 | 135 | 247 |

| Hispanic | 25 | 12 | 37 | 43 | 81 | 124 | 161 |

| Asiana | 7 | 11 | 18 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 19 |

| Total | 121 | 129 | 250 | 134 | 222 | 356 | 606 |

Asians were excluded from the association analysis due to low numbers.

When examining the allelic association of microsatellite repeats 18087–18131(TAA)8−17 with vulnerability to development of heroin addiction (Table 2), we grouped the repeats into two categories using a median split: short (13 and fewer) and long (14 and more). Performing this test for each type of allele separately, we found a significantly increased frequency of the 14-copy allele (long type) in the former heroin-addicted group of African Americans (association with development of addiction, P = 0.0042), which was consistent with the observed decreased frequency of the 11-copy allele (short type) in the addicted group of Caucasians (association with protection from heroin addiction, P = 0.0061). An increased frequency of long repeats in former heroin-addicted groups was found in Caucasians (P = 0.0102) when all short types of alleles were tested vs all long types. Genotypic association of microsatellite repeats with heroin addiction is shown in Supplementary Table S3. Logistic regression performed for the microsatellite marker showed an association of the length of the repeat with the disease status in Caucasians for both alleles (P = 0.0213, Table 2) and genotypes (P = 0.0190, Supplementary Table S3).

To evaluate the joint effect of the long repeats of microsatellite 18087–18131(TAA)8–17 in the CNR1 gene in the three (independent) ethnic groups, we combined the three 1–d.f. χ2-values into a single normal deviate, Z = Σ√χ2/√3 where the square root of χ2 is positive in each ethnicity as the direction of association is the same in each of them. The two-sided significance level associated with the resulting Z = 3.322 is P = 0.0009. With only six SNPs genotyped in this study, even though various tests have been carried out, this result is clearly highly significant.

In Caucasians, we analyzed χ2- and P-values for all fifteen SNP pairs formed by all six polymorphisms tested in this study. The results are shown in Table 4A, where P-values were corrected for multiple testing by permutation testing. One pair of SNPs, 1359G>A and −6274T>A, shows a significant difference in the frequencies of genotype patterns between cases and controls (P = 0.0244). The corresponding genotype patterns (nine patterns total) for this pair of SNPs are shown in Table 4B (the pattern AA-AA was not observed). One particular genotype pattern, TT-GG for 1359G>A and −6274T>A, predominantly contributes to the effect of genotype pair with an OR of 2.875, 95% confidence interval = (1.44, 5.74), which represents the joint effect of these SNPs toward susceptibility to develop heroin addiction. This effect was not found in the African-American and Hispanic ethnicities.

MLGPs were formed for the five SNPs of the CNR1 gene: −22959C>T, −6274T>A, −6215A>C, −5489A>G and 1359G>A (Table 3). These patterns correspond to the splice variants A–D of CNR1 according to the study of Uhl’s group.21 Analysis of the corresponding pattern frequencies showed significant disease association for the pattern CC-TT-AA-AA-GG in Caucasians with P-value = 0.0342 (OR = 0.28, confidence interval = (0.08, 0.94)). MLGPs with frequencies <5% in case and control individuals were combined into a ‘rare’ group. MLGP analysis for the splice variant E21 of CNR1 is shown in Supplementary Table S4. For this variant in Caucasians, a pattern TT-AA-AA-GG has been found to be associated with disease (P = 0.003, OR = 2.82), whereas the other pattern, TT-AA-AA-GA, was found to be associated with protection from the disease (P = 0.008, OR = 0.23). Analysis of haplotypes for the five SNPs −22959C>T, −6274T>A, −6215A>C, −5489A>G and 1359G>A of the CNR1 gene is shown in Supplementary Table S5. No association of any common haplotype with heroin addiction was found in any ethnic group studied.

Linkage disequilibrium plots were constructed for the five SNPs of control samples for each ethnicity separately. There was strong linkage disequilibrium between SNPs −6215A>C and −5489A>G in all ethnicities studied (Supplementary Figure S1).

Using direct sequencing of the CNR1 gene in a subgroup of our subjects, we identified two novel synonymous SNPs in positions 366G>C (Leu → Leu) and 912C>T (His → His). The first polymorphism was found in one heterozygous sample and the second one in three heterozygous samples out of 205 total DNA samples sequenced.

Discussion

In this study, we found that results of an allelic association of 18087–18131(TAA)8–17 in African-American and Caucasian study groups are consistent with each other: in separate tests for each type of the repeat number, a 14-copy repeat (long) was associated with vulnerability to develop heroin addiction in African Americans, whereas the 11-copy repeat (short) was associated with the protective effect from heroin addiction in Caucasians (Table 2). Association of long repeats with vulnerability to develop heroin addiction was consistent in Caucasians when all short repeats were grouped vs all long (Table 2); repeats longer than 13 were associated with vulnerability to develop heroin addiction with P = 0.0009 over all ethnic groups combined. These findings are consistent with and extend the findings of Uhl’s group.21 Using data presented in that table, we found that the frequency of the short alleles is higher in the control group and the frequency of the long allele is higher in the abuser group of Caucasians. In another previous study, allele and genotype frequencies of 18087– 18131(TAA)8–17 were found to be significantly associated with cocaine dependence in an Afro-Caribbean population of Martinique island37 (cocaine-dependent patients with and without comorbidity to schizophrenia were tested vs controls).

In genotype tests of 18087–18131(TAA)8–17, we found increased frequency of the (TAA)26 and (TAA)25 in Caucasian and Hispanic control groups, respectively (Supplementary Table S3). In contrast, we found increased frequencies of the (TAA)30 and the (TAA)20 in former heroin-addicted Caucasians and in Hispanics, respectively.

We found that the patterns of previously reported frequencies for allelic distributions in different ethnic groups21,26,37,38 for the 18087–18131(TAA)8–17 triplet are similar to those found in our study (Table 6), although the highest allele frequency in the control group in both African Americans and Caucasians is shifted by a 1- or 2-triplet repeat, which probably is the result of differences in the methodology.

Table 6.

Comparison of allele frequencies of microsatellite repeats 18087–18131 (AAT)8–17 of the CNR1 gene with previously published data

|

Number of repeats |

Caucasians (this study) |

Caucasians (Zhang et al.21) |

Caucasians (Seifert et al.26) |

African Americans (this study) |

African Americans (Zhang et al.21) |

African Caribbeans (Ballon et al.37) |

Hispanics (this study) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls |

Former heroin addicted |

Controls |

Substance abusers |

Controls | Schizophrenics | Controls |

Former heroin addiced |

Controls |

Substance abusers |

Controls |

Schiz.-cocaine addicted |

N-Schiz. cocaine addicted |

Controls |

Former heroin addicted |

|

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.021 | 0.034 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0.022 | 0.041 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.005 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.014 | 0.020 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0.014 | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0 | 0.011 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0.014 | 0.007 | 0.307 | 0.264 | 0.114 | 0.078 | 0.005 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.041 | 0.036 |

| 11a | 0.290 | 0.185 | 0.006 | 0.011 | 0.032 | 0.034 | 0.422 | 0.411 | 0.132 | 0.093 | 0.006 | 0.056 | 0.031 | 0.351 | 0.302 |

| 12 | 0.058 | 0.030 | 0.360 | 0.306 | 0.161 | 0.139 | 0.223 | 0.177 | 0.385 | 0.417 | 0.057 | 0.267 | 0.253 | 0.081 | 0.044 |

| 13 | 0.156 | 0.156 | 0.103 | 0.083 | 0.168 | 0.236 | 0.102 | 0.120 | 0.198 | 0.235 | 0.375 | 0.233 | 0.263 | 0.176 | 0.173 |

| 14 | 0.196 | 0.215 | 0.103 | 0.161 | 0.286 | 0.274 | 0.024 | 0.089 | 0.132 | 0.098 | 0.216 | 0.167 | 0.149 | 0.135 | 0.153 |

| 15 | 0.254 | 0.326 | 0.191 | 0.129 | 0.018 | 0.014 | 0.114 | 0.104 | 0.027 | 0.880 | 0.091 | 0.067 | 0.103 | 0.176 | 0.238 |

| 16 | 0.022 | 0.044 | 0.197 | 0.257 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0 | 0.016 | 0.104 | 0.059 | 0.114 | 0 | 0.113 | 0.027 | 0.032 |

| 17 | 0 | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.031 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.005 | 0.125 | 0.133 | 0.077 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | 0 | 0 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.017 | 0.067 | 0.010 | 0 | 0 |

Although the pattern of distribution of frequencies of repeats of different lengths in our study is similar to patterns reported in other publications (for example, Refs.21,26,37), the exact counting of the triplets is shifted by 1 or 2 repeats, which probably is the result of differences in the methodology. The reference allele of highest frequency (counted as 11 in our study) is highlighted in bold.

The other polymorphism that was found in this study to be in association with a protective effect from heroin addiction in Caucasians is synonymous 1359G>A. Because this is the only high-frequency variant located in the coding region of CNR1, it has been previously tested for association with various neuropsychiatric conditions and substance abuse and dependence with inconclusive results. In Caucasians, it was associated with severe alcohol withdrawal.39 No association of this polymorphism with a history of alcohol withdrawal-induced seizures was found.40 In a study of schizophrenia in a French-Caucasian population, Leroy et al.41 reported a lower representation of the 1359GG genotype in nonsubstance-abusing patients, compared to substance-abusing patients, suggesting an association between CNR1 variants and substance abuse in schizophrenia. In Germans, the 1359G>A was not found to be associated with schizophrenia.26 Another study42 found an association between cannabis use and schizophrenia in a population of Caucasians in the United Kingdom, but no association of 1359G>A with drug use. In a French cohort, there was no association of this polymorphism with schizophrenia,43 although the frequency of the G allele was significantly higher among patients who were nonresponsive to antipsychotics. In German opioid addicts and age- and gender-matched controls, no association of the 1359G>A with intravenous drug addiction was found.38

A study of CNR1 mRNAs by Uhl’s group in Caucasian, African-American and Japanese populations revealed novel exonic sequences, splice variants and polymorphisms of CNR1.21 Specific splice variants were expressed differentially in different brain regions: caudate, substantia nigra and amygdala express a large amount of the splice variant E of the CNR1 gene that contains exon 3, but not exons 1 and 2.21 To study the influence of different splice variants on initiation of heroin addiction, we analyzed an association of patterns formed by five SNPs: −22959C>T, −6274T>A, 6215A>C, −5489A>G and 1359G>A (splice variants A–D of CNR1, Table 3) and four SNPs: −6274T>A, 6215A>C, −5489A>G and 1359G>A (splice variant E of CNR1, Supplementary Table S4). In Caucasians, for the four-SNP locus we found pattern TT-AA-AA-GG to be associated with disease (P = 0.003, OR = 2.82). In contrast, we found another pattern, TT-AA-AA-GA, to be associated with protection from the disease (P = 0.008, OR = 0.23).

SNPs −22959C>T, −6274T>A and −5489A>G were reported to be associated with polysubstance abuse in European Americans; SNPs −6274T>A, −6215A>C and −5489A>G were found to be associated with polysubstance abuse in African Americans.21 Another group44 found no association of these SNPs (−6274T>A, −6215A>C and −5489A>G) with substance dependence diagnoses, including alcohol, cocaine and opioids in either European-American or African-American subjects. In our studies, we also found no association of these polymorphisms with vulnerability to develop heroin addiction in any ethnic group.

One study found an associations of −39884C>G (rs1884830), −17937T>G (rs6454674) and 4893T>C (rs806368) with drug dependence at the allele level and −39884C>G at the genotype level in European Americans.45 Also in European Americans, associations of −39884C>G, −17937T>G, −6274T>A and 4893T>C SNPs with comorbid drug and alcohol dependence were found at the allele level. Interestingly, we found an association of the joint genotype that includes one of these SNPs, −6274T>A, with heroin addiction also in European Americans.

There were several studies of an association of missense substitution 385C > A in the FAAH gene (resulting in protein change 129P>T) with various diseases. In studies of a Japanese cohort,46 no association of this polymorphism with either methamphetamine dependence or schizophrenia was found. SNP 385C>A has been reported as a risk factor for problem drug use and street drug use but not alcohol or tobacco use or dependence in Caucasians.12,47 In another study of a Caucasian cohort,48 individuals with the 385AA genotype were found to be at reduced risk for cannabis dependence. In our studies, we did not find an association of 385C > A with heroin addiction. This might be a result of use of different phenotype criteria during subject classification.

Given the number of tests performed, some observed results may be due to type 1 error. A few values were no longer significant after correcting for multiple testing. A future study with a larger number of subjects would be important for confirmation of our findings. Taken together, our findings support the hypothesis of an involvement of polymorphisms of the CNR1 gene in the vulnerability to develop heroin addiction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Vadim Yuferov, Dr David Nielsen, Dr Orna Levran and the late Dr K Steven LaForge for comments and a critical review of the paper. We thank Matthew Swift and Johannes Adomako-Mensah for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH-NIDA Grant P60-DA05130 (MJK), NSFC Grant 30730057 from the Chinese Government (JO) and NIH/NCRR-CTSA UL1-RR024143 (The Rockefeller University Center for Clinical and Translational Science).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on The Pharmacogenomics Journal website (http://www.nature.com/tpj)

References

- 1.Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Little MD, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, de Costa BR, et al. Cannabinoid receptor localization in brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1932–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, de Costa BR, Rice KC. Characterization and localization of cannabinoid receptors in rat brain: a quantitative in vitro autoradiographic study. J Neurosci. 1991;11:563–583. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-02-00563.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsou K, Brown S, Sañudo-Peña MC, Mackie K, Walker JM. Immunohistochemical distribution of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the rat central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1998;83:393–411. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00436-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M. Molecular characterization of peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature. 1993;365:61–65. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Sickle MD, Duncan M, Kingsley PJ, Mouihate A, Urbani P, Mackie K, et al. Identification and functional characterization of brainstem cannabinoid CB2 receptors. Science. 2005;310:329–332. doi: 10.1126/science.1115740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howlett AC, Barth F, Bonner TI, Cabral G, Casellas P, Devane WA, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XXVII. Classification of cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:161–202. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, Pertwee RG, Stevenson LA, Griffin G, et al. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science. 1992;258:1946–1949. doi: 10.1126/science.1470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugiura T, Kondo S, Sukagawa A, Nakane S, Shinoda A, Itoh K, et al. 2-Arachidonoylglycerol: a possible endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand in brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;215:89–97. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deutsch DG, Ueda N, Yamamoto S. The fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2002;66:201–210. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKinney MK, Cravatt BF. Structure and function of fatty acid amide hydrolase. Ann Rev Biochem. 2005;74:411–432. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cravatt BF, Demarest K, Patricelli MP, Bracey MH, Giang DK, Martin BR, et al. Supersensitivity to anandamide and enhanced endogenous cannabinoid signaling in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9371–9376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161191698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sipe JC, Chiang K, Gerber AL, Beutler E, Cravatt BF. A missense mutation in human fatty acid amide hydrolase associated with problem drug use. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8394–8399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082235799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiang KP, Gerber AL, Sipe JC, Cravatt BF. Reduced cellular expression and activity of the P129T mutant of human fatty acid amide hydrolase: evidence for a link between defects in the endocannabinoid system and problem drug use. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2113–2119. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Navarro M, Chowen J, Carrera MRA, del Arco I, Villanúa MA, Martin Y, et al. CB1 cannabinoid receptor antagonist-induced opiate withdrawal in morphine-dependent rats. Neuroreport. 1998;9:3397–3402. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199810260-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navarro M, Carrera MR, Fratta W, Valverde O, Cossu G, Fattore L, et al. Functional interaction between opioid and cannabinoid receptors in drug self-administration. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5344–5350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05344.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Vries TJ, Homberg JR, Binnekade R, Raasø H, Schoffelmeer AN. Cannabinoid modulation of the reinforcing and motivational properties of heroin-associated cues in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:164–169. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1422-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mascia MS, Obinu MC, Ledent C, Parmentier M, Böhme GA, Imperato A, et al. Lack of morphine-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens of cannabinoid CB (1) receptor knockout mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;383:R1–R2. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00656-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cossu G, Ledent C, Fattore L, Imperato A, Böhme GA, Parmentier M, et al. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice fail to self-administer morphine but not other drugs of abuse. Behav Brain Res. 2001;118:61–65. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caenazzo L, Hoehe MR, Hsieh WT, Berrettini WH, Bonner TI, Gershon ES. Hindill identifies a two allele DNA polymorphism of the human cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR) Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4798. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.17.4798-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gadzicki D, Müller-Vahl K, Stuhrmann M. A frequent polymorphism in the coding exon of the human cannabinoid receptor (CNR1) gene. Mot Cell Probes. 1999;13:321–323. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1999.0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang PW, Ishiguro H, Ohtsuki T, Hess J, Carillo F, Walther D, et al. Human cannabinoid receptor 1:5′ exons, candidate regulatory regions, polymorphisms, haplotypes and association with polysubstance abuse. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:916–931. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoehe MR, Caenazzo L, Martinez MM, Hsieh WT, Modi WS, Gershon ES, et al. Genetic and physical mapping of the human cannabinoid receptor gene to chromosome 6q14-q15. New Biol. 1991;3:880–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai SJ, Wang YC, Hong CJ. Association study between cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1) and pathogenesis and psychotic symptoms of mood disorders. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105:219–221. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai SJ, Wang YC, Hong CJ. Association study of a cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1) polymorphism and schizophrenia. Psychiatr Genet. 2000;10:149–151. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200010030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ujike H, Takaki M, Nakata K, Tanaka Y, Takeda T, Kodama M, et al. CNR1, central cannabinoid receptor gene, associated with susceptibility to hebephrenic schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:515–518. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seifert J, Ossege S, Emrich HM, Schneider U, Stuhrmann M. No association of CNR1 gene variations with susceptibility to schizophrenia. Neurosci Lett. 2007;426:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Comings DE, Muhleman D, Gade R, Johnson P, Verde R, Saucier G, et al. Cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1): association with i.v. drug use. Mol Psychiatry. 1997;2:161–168. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li T, Liu X, Zhu ZH, Zhao J, Hu X, Ball DM, et al. No association between (AAT)n repeats in the cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1) and heroin abuse in a Chinese population. Mol Psychiatry. 2000;5:128–130. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rettig RA, Yarmolinsky A, editors. Federal Regulation of Methadone Treatment. National Academy of Sciences. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kellogg SH, McHugh PF, Bell K, Schluger JH, Schluger RP, LaForge KS, et al. The Kreek-McHugh-Schluger-Kellogg scale: a new, rapid method for quantifying substance abuse and its possible applications. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69:137–150. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bond C, LaForge KS, Tian M, Melia D, Zhang S, Borg L, et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphism in the human mu opioid receptor gene alters beta-endorphin binding and activity: possible implications for opiate addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9608–9613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Everitt BS. The Analysis of Contingency Tables. 2nd edn. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. 2nd edn. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoh J, Wille A, Ott J. Trimming, weighting, and grouping SNPs in human case-control association studies. Genome Res. 2001;11:2115–2119. doi: 10.1101/gr.204001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ballon N, Leroy S, Roy C, Bourdel MC, Charles-Nicolas A, Krebs MO, et al. (AAT)n repeat in the cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1): association with cocaine addiction in an African-Caribbean population. Pharmacogenomics J. 2006;6:126–130. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heller D, Schneider U, Seifert J, Cimander KF, Stuhrmann M. The cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1) is not affected in German i.v. drug users. Addict Biol. 2001;6:183–187. doi: 10.1080/13556210020040271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt LG, Samochowiec J, Finckh U, Fiszer-Piosik E, Horodnicki J, Wendel B, et al. Association of a CB1 cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1) polymorphism with severe alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;65:221–224. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Preuss UW, Koller G, Zill P, Bondy B, Soyka M. Alcoholism-related phenotypes and genetic variants of the CB1 receptor. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neourosci. 2003;253:275–280. doi: 10.1007/s00406-003-0440-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leroy S, Griffon N, Bourdel MC, Olié JP, Poirier MF, Krebs MO. Schizophrenia and the cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1): association study using a single-base polymorphism in coding exon 1. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105:749–752. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zammit S, Spurlock G, Williams H, Norton N, Williams N, O’Donovan MC, et al. Genotype effects of CHRNA7, CNR1, COMT in schizophrenia: interactions with tobacco cannabis use. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:402–107. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamdani N, Tabeze JP, Ramoz N, Ades J, Hamon M, Sarfati Y, et al. The CNR1 gene as a pharmacogenetic factor for antipsychotics rather than a susceptibility gene for schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herman AI, Kranzler HR, Cubells JF, Gelernter J, Covault J. Association study of the CNR1 gene exon 3 alternative promoter region polymorphisms and substance dependence. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141B:499–503. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zuo L, Kranzler HR, Luo X, Covault J, Gelernter J. CNR1 variation modulates risk for drug and alcohol dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:616–626. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morita Y, Ujike H, Tanaka Y, Uchida N, Nomura A, Ohtani K, et al. A nonsynonymous polymorphism in the human fatty acid amide hydrolase gene did not associate with either methamphetamine dependence or schizophrenia. Neurosci Lett. 2005;376:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flanagan JM, Gerber AL, Cadet JL, Beutler E, Sipe JC. The fatty acid amide hydrolase 385 A/A (P129T) variant: haplotype analysis of an ancient missense mutation and validation of risk for drug addiction. Hum Genet. 2006;120:581–588. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tyndale RF, Payne JI, Gerber AL, Sipe JC. The fatty acid amide hydrolase C385A (P129T) missense variant in cannabis users: studies of drug use and dependence in Caucasians. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:660–666. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.