Abstract

Objective

Little data have been reported regarding radiation exposure during pediatric endourologic procedures, including ureteroscopy (URS). We sought to measure radiation exposure during pediatric URS and identify opportunities for exposure reduction.

Methods

We prospectively observed URS procedures as part of a quality improvement initiative. Pre-operative patient characteristics, operative factors, fluoroscopy settings and radiation exposure were recorded. Our outcomes were entrance skin dose (ESD, in mGy) and midline dose (MLD, in mGy). Specific modifiable factors were identified as targets for potential quality improvement.

Results

Direct observation was performed on 56 consecutive URS procedures. Mean patient age was 14.8 ± 3.8 years (range 7.4 to 19.2); 9 children were under age 12 years. Mean ESD was 46.4 ± 48 mGy. Mean MLD was 6.2 ± 5.0 mGy. The most important major determinant of radiation dose was total fluoroscopy time (mean 2.68 ± 1.8 min) followed by dose rate setting, child anterior-posterior (AP) diameter, and source to skin distance (all p<0.01). The analysis of factors affecting exposure levels found that the use of ureteral access sheaths (p=0.01) and retrograde pyelography (p=0.04) were significantly associated with fluoroscopy time. We also found that dose rate settings were higher than recommended in up to 43% of cases and ideal C-arm positioning could have reduced exposure 14% (up to 49% in some cases).

Conclusions

Children receive biologically significant radiation doses during URS procedures. Several modifiable factors contribute to dose and could be targeted in efforts to implement dose reduction strategies.

Keywords: Nephrolithiasis, Pediatrics, Kidney, Stone, Urolithiasis

Introduction

Increasing medical radiation exposure is generating considerable concern in the United States. By some estimates, per capita radiation exposure today is more than seven times greater than 30 years ago.1 Children are particularly vulnerable to long-term effects of ionizing radiation, due to both their long anticipated lifespan and to the relatively higher radio-sensitivity of rapidly growing tissues.2 The United States National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements (NCRP) advocates the “as low as reasonably achievable” (ALARA) principle when using ionizing radiation for medical purposes, particularly in children.3

Previous work has shown that children with urolithiasis have a nearly 40% chance of stone recurrence and that many will undergo multiple stone procedures during their lifetime.4 The incidence of urolithiasis in the pediatric population may be increasing,5, 6 and with this comes the need for both medical imaging and surgical intervention. Although shock wave lithotripsy (SWL) has long been considered the first-line therapy for children with stones urologists have increasingly turned to URS techniques in these patients,7, 8 which is typically performed using fluoroscopic guidance. In addition to surgical intervention, many will undergo radiation-intensive diagnostic imaging such as CT.9

There are very few studies documenting the radiation exposure associated with URS,10 and none in pediatric patients. The aims of this quality improvement project were thus to systematically measure radiation exposure during URS in children, to identify factors associated with increased exposure, and to identify potential opportunities to reduce exposure.

Methods

After IRB approval, we prospectively monitored all URS procedures at our institution from September 2009 to December 2010. A research assistant (urology fellow or masters-level research associate familiarized with ureteroscopic procedures) was present in the operating room for each case. Preoperatively, we collected demographics, medical history, and stone burden from imaging. After induction of anesthesia, we measured patient anteroposterior (AP) diameter at the umbilicus with calipers. Intraoperatively, equipment and techniques (e.g. ureteral access sheath, retrograde pyelography, safety wires, mode of lithotripsy, basket extraction, pre- or post-procedure ureteral stent), fluoroscopy unit factors (unit ID, position, individual directly controlling the unit, total fluoroscopy time and machine settings) and other relevant factors (surgeon, level of trainee involvement, total anesthesia time) were recorded. The mobile fluoroscopy units used were BV Pulsera (2006, Philips Medical Systems, Netherlands) with 23 cm intensifiers.

Operating room staff were broadly informed of the study, but in order to minimize the Hawthorne effect,11 the specific data collected were not disclosed and the individual collecting data minimized their interactions with operating room personnel.

Radiation exposure was calculated as both entrance skin dose (ESD) and midline dose (MLD). ESD estimates radiation dose to the skin, the organ that receives the maximum dose, while MLD is a better approximation of the ‘average’ dose received by all irradiated tissue. ESD was indirectly measured from the fluoroscopy unit's dosimeter: (air kerma) at 70 cm from the radiation source. To calculate ESD, the air kerma is adjusted for back scatter (factor of 1.2), bed/pad attenuation (measured as 0.40 at 70kV), and observed source to skin distance (SSD) (using the inverse square law). MLD at the midpoint of the patient's umbilical AP diameter was estimated from the calculated ESD by applying appropriate tissue attenuation factors for a 70kV beam from a mobile fluoroscope. SSD was calculated from direct measurements of the patient and fluoroscopy unit. All dose calculations were performed by a radiation physicist (KS).

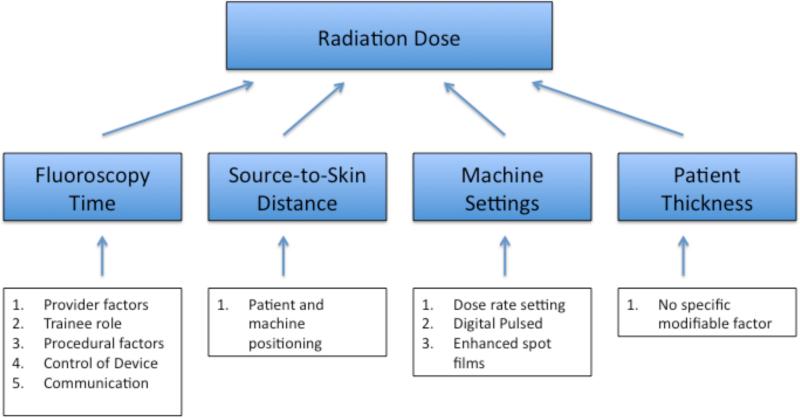

The known determinants primarily responsible for radiation exposure in the setting of fluoroscopy include the patient AP diameter, total fluoroscopy time, SSD, and the fluoroscope's exposure parameters (e.g. voltage and tube current). We used these determinants to develop a conceptual model of factors affecting radiation exposure (Figure 1). The independent effect of each of these determinants was estimated using multivariable regression. The relative importance of each determinant was determined by comparing a series of nested models.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model.

To assess how technique modification might be expected to impact ESD, we conducted sensitivity analyses. We assumed that ideal SSD would result if the image intensifier were placed no more than 7 cm above the patient's umbilicus. Appropriate fluoroscopy machine dose rate settings were derived from institutional recommendations for children with an AP diameter of < 12 cm (“Toddler”), 12-20 cm (“Child”), and > 20 cm (“Adult”). We contrasted these recommendations with the actual settings for study patients.

We estimated stone burden as the total number of treated stones, as categories, as the sum of the treated stone diameters, and as the sum of the calculated spherical volumes of the treated stones. We categorized stone location as renal (other than lower pole), renal (lower pole), ureteral, or mixed.

Total surgical time was measured from scope insertion to the procedure completion time, as noted by the surgeon and verified using intra-operative records. Level of trainee involvement (based on the individual handling the ureteroscope) was defined categorically as <50%, ~50% or >50% as determined by attending of record.

Univariate tests of association were performed to examine relationships between measured factors and major determinants of radiation exposure using t-tests or wilcoxon rank sum, chi-square or Fisher's exact tests based on data characteristics. Multivariable regression was used to control for potential confounding when sufficient data points per outcome group were available. Log-transformed ESD was used as our primary outcome of interest. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). All tests were two-sided and p-values of 0.05 or less were considered significant.

Results

We observed 54 URS procedures, 17 of which were excluded (11 due to patient age > 21 years, 4 due to indication other than urolithiasis, 2 bilateral procedures were excluded). Descriptive information for the remaining 37 patients is presented in Table 1. In 5/37 cases (13.5%) the stone seen on preoperative imaging was not treated with lithotripsy or stone basketing (3 stented UVJ stones that likely passed ,1 small ureter requiring stenting, 1 case with many small fragments and Randall's plaques).

Table 1.

Descriptive Information.

| Child Factors | All Age<21 years (n=37) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean (yrs) | 14.8± 4.0 |

| Less than 6 years | 0 (0%) |

| 6-10 years | 7 (19%) |

| 10-12 years | 2 (5%) |

| >12 years | 28 (76%) |

| Anterior Posterior Thickness (at Umbilicus in cm) | 18.6± 4.3 |

| Fluoroscopy Machine | |

| Total Fluoroscopy Time (min) | 2.68± 1.8 |

| Positioning | |

| Source to Skin (entry) (cm) | 67± 8 |

| Skin (exit) to Intensifier (cm) | 12± 7 |

| Dose Rate Machine Setting | |

| Toddler | 1 (3%) |

| Child | 6 (16%) |

| Adult | 30 (81%) |

| Technical Related Factors | |

| Total Surgery Time (min) | 73± 45 |

| Total Stone Diameter in mm (n) | 7.7± 7.3 |

| Total Stone Vol in mm3 (n) | 543± 1357 |

| Number of Stones Treated with Lithotripsy and/or Basket removal (n) | 14% (5) |

| None | 62% (23) |

| One | 24% (9) |

| Multiple | |

| Stone Location (n) | |

| Renal not Lower Pole | 28% (9) |

| Lower Pole Renal | 19% (6) |

| Ureteral | 47% (15) |

| Mixed | 6% (2) |

| Basket Extraction (n) | |

| Yes | 62% (23) |

| No | 38% (14) |

| Laser Lithotripsy (n) | |

| Yes | 54% (20) |

| No | 46% (17) |

| Pre-op stent in place (n) | |

| Yes | 41% (15) |

| No | 59% (22) |

| Post-op stent (n) | |

| Yes | 84% (31) |

| No | 16% (6) |

| Ureteral Access Sheath (n) | |

| Yes | 70% (26) |

| No | 30% (11) |

| Retrograde Pyelogram (n) | |

| Yes | 86% (32) |

| No | 14% (5) |

| Safety Wire Used (n) | |

| Yes | 84% (31) |

| No | 16% (6) |

| Complications (n) | |

| Yes | 11% (4) |

| No | 89% (33) |

| Surgeon | |

| Trainee Role (n) | |

| <50% | 8% (3) |

| 50% | 81% (30) |

| >50% | 11% (4) |

| Surgeon (n) | |

| A | 27% (10) |

| B | 5% (2) |

| C | 35% (13) |

| D | 16% (6) |

| E | 5% (2) |

| F | 11% (4) |

Radiation dose outcomes (with reference standards) are presented in Table 2. Mean ESD was 46.4 ± 48 (range: 2.7-223 mGy). Mean MLD was 6.2 ± 5.0 (range 0.7-17.1 mGy). After adjusting for non-modifiable factors (i.e., patient AP diameter and stone burden), neither individual surgeon (p=0.12-0.28) nor degree of trainee participation (p=0.41-0.57) was associated with ESD or MLD.

Table 2.

Primary dose outcomes for pediatric ureteroscopy with typical doses for commonly used radiologic genitourinary studies at our institution.

| Exam Type | Entrance Skin Dose (mGy) | Midline Dosea (mGy) |

|---|---|---|

| Pediatric Ureteroscopy | 46.4b (range 2.7-223) | 6.2b (range 0.7-17.1) |

| Chest X-ray (PA&Lat) | 0.2 | 0.002 |

| Abdominal X-ray (KUB) | 0.75 | 0.1 |

| Voiding Cystourethrogram | 6.0 | 1.0 |

| Abdominal/Pelvic CT scan | 20 | 15 |

Midline doses based on the central exposure dose of a typical 15 year old.

Values for dose outcomes based on mean value for the current study.

Multivariable analysis confirmed that hypothesized primary dose determinants were significant predictors of ESD, including AP diameter (p<0.01), total fluoroscopy time (p<0.01), SSD (p<0.01), and dose rate setting (p<0.01). The most important determinant of ESD was total fluoroscopy time (ΔAIC= 63) followed by dose rate setting (ΔAIC=55), AP diameter (ΔAIC=23), and skin to SSD (ΔAIC=9).

Total Fluoroscopy Time

The mean adjusted fluoroscopy time for all pediatric cases was 2.68±1.8 min (range 0.4-6.7; Table 1). Operative time was similar between cases with and without treated stones (mean 2.8 ± 1.7 min versus 2.1± 2.6 min; p=0.44). Clinical factors significantly associated with increased fluoroscopy time (Table 3) include ureteral access sheath use (p=0.01) and retrograde pyelography (p=0.04). Other analyzed factors were not significantly associated with fluoroscopy time, including other measures of stone burden (p=0.65 to 0.96), total operative time (p=0.56), basket stone removal (p=0.53), laser use (p=0.98), pre-operative stent in place (p=0.78), post-lithotripsy stenting (p=0.06), safety wire use (p=0.22), stone location (p=0.89), trainee role (p=0.52), surgeon (p=0.11) and complications (perforation by wire [n=2], accidental stent dislodgement [n=1], inability to pass ureteroscope up to the proximal ureter [n=1]; p=0.33)) .

Table 3.

Predictors of Total Fluoroscopy Time in Pediatric Ureteroscopy

| Potential Predictors | Mean Fluoroscopy Time in Minutes (n) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Overall (all pediatric cases) | 2.68 ± 1.8 min range 0.4-6.7 | -- |

| Total Surgical Time | Correlation 0.10 | p=0.56 |

| Stones Treated with Lithotripsy and/or Basket Removal | ||

| Yes | 2.8± 1.7 (32) | p=0.44 |

| No | 2.1± 2.6 (5) | |

| Stone Burden by | ||

| Volume | Correlation 0.08 | p=0.65 |

| Diameter | Correlation 0.07 | p=0.69 |

| Total Stone Number | Correlation 0.08 | p=0.63 |

| Stone Number Category | ||

| None/Fragments | 2.1± 2.6 (5) | p=0.74 |

| One | 2.8± 1.7 (23) | |

| Multiple | 2.8± 1.8 (9) | |

| Stone Location (n=35) | ||

| Renal not Lower Pole | 3.1± 1.9 (9) | p=0.89 |

| Lower Pole Renal | 2.8± 1.6 (6) | |

| Ureteral | 2.5± 1.7 (15) | |

| Mixed | 3.0± 2.3 (2) | |

| Basket Stone Removal | ||

| Yes | 2.5± 1.5 (23) | p=0.53 |

| No | 2.9± 2.2 (14) | |

| Laser Lithotripsy | ||

| Yes | 2.7± 1.7 (20) | p=0.98 |

| No | 2.7± 2.0 (17) | |

| Pre-op Stent in Place | ||

| Yes | 2.8±2.0 (15) | p=0.78 |

| No | 2.6±1.7 (22) | |

| Post Treatment Stent Placed | ||

| Yes | 2.9±1.8 (31) | p=0.06 |

| No | 1.4±1.0 (6) | |

| Access Sheath Used | ||

| Yes | 3.1±1.8 (26) | p=0.01 |

| No | 1.6±1.4(11) | |

| Retrograde Pyelography | ||

| Yes | 2.9±1.8 (32) | p=0.04 |

| No | 1.2±1.2 (5) | |

| Safety Wire Used | ||

| Yes | 2.8±1.7 (31) | p=0.22 |

| No | 1.9±2.1 (6) | |

| Complications | ||

| Yes | 4.0±2.3 (4) | p=0.33 |

| No | 2.5±1.7 (33) | |

| Degree of Trainee Participation | ||

| Less than 50% | 2.1±1.0 (3) | p=0.55 |

| ~50% | 2.8±1.9 (30) | |

| Greater than 50% | 1.9±1.9 (4) | |

| Surgeon | ||

| A | 2.2±1.6 (10) | p=0.11 |

| B | 3.1±2.9 (2) | |

| C | 2.4±1.4 (13) | |

| D | 4.1±2.2 (6) | |

| E | 0.4±0.0 (2) | |

| F | 3.5±1.9 (4) | |

SSD

For one patient, SSD was aberrantly small due to positioning of the radiation source above rather than below the patient. Mean SSD for the remaining patients was 67.5 ± 5.5 cm. Trainee involvement (p=0.46) was not significantly associated with SSD and neither was individual surgeon (p=0.30, Table 3). Mean exit to intensifier distance was 12.3 ± 6.7 cm. Mean excess space (difference between the optimal exit to intensifier distance (7 cm) and the measured exit to intensifier distance) was 5.2 ± 4.9 cm (range: 0-21). On average, the potential ESD reduction from removing excess space was 13.8%. For individual children, this dose reduction ranged from 0 to 49%.

Machine Settings

Fluoroscopy units were set on the “Adult” setting in 81% (30/37) of cases. Comparing recommended dose rate settings (based on AP diameter measurements) to settings actually used, 18/37 (49%) of cases were performed at a setting that was higher than recommended. Only 1/37 (3%) of cases were performed at a dose rate setting lower then recommended. Use of a higher-than-recommended setting was not significantly associated with individual surgeon (p=0.90) or trainee role (p=0.51).

Discussion

These data were collected as part of a quality improvement project seeking to reduce radiation exposure to pediatric patients during URS procedures for urolithiasis. The average ESD exposure for children undergoing URS was 46.4 mGy, or more than double that of a typical abdominal/pelvic CT scan. MLD was also significant and represents a substantial dose to internal organs (Table 2). Dose should be minimized whenever possible to reduce potential risks to the patient from ionizing radiation.

Exposure to medical radiation is a public health and safety issue, especially in the pediatric population. Pediatric patients are 3-10 times more radiation-sensitive than adults due to their longer life span and to the higher radiosensitivity of developing organs.12 There is an increasing awareness of pediatric radiation exposure through imaging modalities such as CT scans.13, 14 Collaborative efforts of radiologists and the medical imaging industry have promoted the ALARA principle,15 and there is widespread agreement that reducing radiation exposure, particularly among children, should be addressed.3, 16

It is possible to reduce radiation dose through a combination of system-based changes, education, and technical modifications. Successful efforts have focused on diagnostic procedures such as voiding cystourethrography,17 cardiac catheterization,18 and interventional fluoroscopy.19 Pediatric fluoroscopy was specifically targeted in the recent Pause and Pulse initiative from the Image Gently Campaign of the Alliance for Radiation Safety in Pediatric Imaging.20 With respect to endourological procedures, studies have demonstrated benefits of specific protocols and technical modifications.21 Our analysis suggests that targets exist for reducing dose in children undergoing URS at our institution. These include modifications to fluoroscopy unit settings, patient and unit positioning, and surgeon technique changes in the operating room (Table 4).

Table 4.

Targets for a hypothetical intervention aimed at dose reduction consistent with the ALARA principle.

| Targeted Change in Practice | Potential Effect |

|---|---|

| Maximize Source to Skin Distance | Mean 13% (range 0-49%) |

| Proper Dose Rate Setting | Significant dose reduction for 49% of cases |

| Judicious use of Fluoroscopy | Dose reduction proportional to decrease in total fluoroscopy time |

| Clear communication | Dose reduction proportional to decrease in total fluoroscopy time |

Basic maneuvers minimize excess radiation exposure to both patients and operating room personnel. Fluoroscopy machines allow various exposure settings including continuous and pulsed modes. Pulsed techniques allow adequate visualization with a ~10-fold reductions in dose.17 The default setting for fluoroscopy units at our institution is a digital pulsed (12 pulse/sec) exposure setting. When taking single images, machines often provide an option for a higher-quality digital radiograph. Such higher-quality imaging is often unnecessary; as an alternative, use of the “image hold” function allows the last frame of fluoroscopy images to be displayed as a still radiographic image. We have found these images to be of sufficient quality for most situations during URS. Other important machine settings include a size-specific dose rate setting. In this investigation, we observed that dose rate settings were poorly matched to actual patient size in half of cases, and improved attention to this parameter could have a highly favorable impact on exposure.

Maximizing SSD by bringing the fluoroscopy unit's image intensifier (not the source) as close to the patient as possible can avoid unnecessary exposure. Our sensitivity analyses suggest that simple positioning changes could have reduced radiation doses by 14% on average and up to 49% for some individuals.

Radio-opaque materials placed between the skin exit surface and the image intensifier will increase the ESD required to penetrate the additional matter. This also increases scattered radiation to the surgeon and operating room personnel. Improved collimation techniques reduce the irradiated skin area and the total volume of irradiated tissue.

Simple feedback mechanisms help remind the fluoroscope operator when ionizing radiation is being produced. For most fluoroscopy systems, an indicator light on the display unit illuminates during x-ray production. In our hospital, the indicator light is frequently located out of view of the operating surgeon, allowing little active feedback and perhaps representing an opportunity for dose reduction. Post procedure feedback and documentation may also affect radiation exposure. Studies have found a 24% reduction in total fluoroscopy time when surgeons were provided feedback on usage and 40% lower times when radiologists specifically included total duration in their dictated reports.22, 23

At our hospital, a radiation technologist activates the fluoroscopy unit, based on verbal direction from the surgeon. Control at other institutions may differ, with direct surgeon control in many cases. Urologists are trained to safely use fluoroscopic equipment during residency, and use of this equipment is an integral component of endourological practice. Nevertheless, urologists have less training in both radiation physics and in the practical utilization of imaging equipment than radiologists or radiation technologists. There are no data regarding the relative merits of who controls the fluoroscopy unit during endourological procedures, although imaging utilization issues have been the subject of extensive “turf battles” among medical specialty societies.24

Given the active role of the radiation technologist at our institution, we believe that improved communications will likely result in dose reductions. Improvements might include standardized terminology, technologist-initiated collimation or audio-visual alerts (e.g. audible alarms) during fluoroscopy. In this series, the technologist initiated collimation in both cases where this technique was used.

The results of our analyses should be interpreted in light of their limitations. This is an observational study of patients treated at a single tertiary center; patient characteristics, surgical practices and other factors in this setting may not apply to other settings. These patients may be more complex or have greater stone burdens leading to above-average radiation exposure. Additionally, the significant degree of heterogeneity among both patients and surgeon practices reduces our ability to identify some factors that may be associated with radiation exposure. Several patients had ureteroscopic explorations without stone fragmentation or basket removal, which had lower (but not statistically different) fluoroscopy times. Three of these involved stented UVJ stones, with ureteroscopic confirmation of passage, one involved difficulty traversing a small caliber ureter, and one patient had multiple small fragments and Randall's plaques mimicking larger stones. Relatively small sample sizes preclude more complex statistical analysis. In an un-blinded study such as this, the results may be susceptible to the Hawthorne effect,11 as surgeons and OR staff were aware that they were being observed and may have altered their behavior as a consequence. While we did minimize observer and staff interactions, our direct measurement methods could not practically be completely concealed. Mitigating factors include the fact that observed staff had little risk of negative repercussions from our study findings, and that the observers were not in a position of authority over those being observed. While radiation exposure was carefully assessed, we used indirect methods to determine dose outcomes. Despite strong correlation between indirect and direct measurement methods, some imprecision is unavoidable.

Conclusion

Pediatric patients undergoing URS are exposed to significant levels of ionizing radiation. Given the long-term risks associated with cumulative radiation exposure, it is prudent to actively reduce exposure in accordance with the ALARA principle. Systematic investigation of current practices is a crucial first step towards achieving meaningful dose reductions consistent.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the operating room staff, the participating surgeons, Michael Demers and all of the radiation technologists for their invaluable contributions to this project.

Funding: Dr. Kokorowski is supported by grant number T32-DK60442 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), and Dr. Nelson is supported by grant number K23-DK088943 from NIDDK.

Abbreviations

- ALARA

As Low As Reasonably Acheivable

- ESD

Entrance skin dose

- MLD

Midline absorbed dose

- SSD

Source to skin distance

- URS

Ureteroscopy

- AP

Anterior to posterior

- CT

Computed tomography

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: None of the authors have a conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements. National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements. Scientific Committee 6-2 on Radiation Exposure of the U.S. Population . Ionizing radiation exposure of the population of the United States : recommendations of the National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements. National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements; Bethesda, Md.: 2009. p. xv.p. 387. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Preston DL, Cullings H, Suyama A, et al. Solid cancer incidence in atomic bomb survivors exposed in utero or as young children. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:428. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strauss KJ, Kaste SC. The ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) concept in pediatric interventional and fluoroscopic imaging: striving to keep radiation doses as low as possible during fluoroscopy of pediatric patients--a white paper executive summary. Radiology. 2006;240:621. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2403060698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.VanDervoort K, Wiesen J, Frank R, et al. Urolithiasis in pediatric patients: a single center study of incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. J Urol. 2007;177:2300. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Routh JC, Graham DA, Nelson CP. Epidemiological trends in pediatric urolithiasis at United States freestanding pediatric hospitals. J Urol. 2010;184:1100. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.VanDervoort K, Wiesen J, Frank R, et al. Urolithiasis in pediatric patients: a single center study of incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. J Urol. 2007;177:2300. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SS, Kolon TF, Canter D, et al. Pediatric flexible ureteroscopic lithotripsy: the children's hospital of Philadelphia experience. J Urol. 2008;180:2616. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smaldone MC, Cannon GM, Jr., Wu HY, et al. Is ureteroscopy first line treatment for pediatric stone disease? J Urol. 2007;178:2128. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Routh JC, Graham DA, Nelson CP. Trends in imaging and surgical management of pediatric urolithiasis at American pediatric hospitals. J Urol. 2010;184:1816. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bagley DH, Cubler-Goodman A. Radiation exposure during ureteroscopy. J Urol. 1990;144:1356. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39739-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vehmas T. Hawthorne effect: shortening of fluoroscopy times during radiation measurement studies. Br J Radiol. 1997;70:1053. doi: 10.1259/bjr.70.838.9404210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) Sources, effects and risks of atomic radiation. II. United Nations; New York: 2000. p. 13. Ref Type: Serial (Book. Monograph), 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brenner D, Elliston C, Hall E, et al. Estimated risks of radiation-induced fatal cancer from pediatric CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:289. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.2.1760289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paterson A, Frush DP, Donnelly LF. Helical CT of the body: are settings adjusted for pediatric patients? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:297. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.2.1760297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slovis TL. The ALARA concept in pediatric CT: myth or reality? Radiology. 2002;223:5. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2231012100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography--an increasing source of radiation exposure. N.Engl.J Med. 2007;357:2277. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward VL, Strauss KJ, Barnewolt CE, et al. Pediatric radiation exposure and effective dose reduction during voiding cystourethrography. Radiology. 2008;249:1002. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2492062066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Justino H. The ALARA concept in pediatric cardiac catheterization: techniques and tactics for managing radiation dose. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36:146. doi: 10.1007/s00247-006-0194-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strauss KJ. Pediatric interventional radiography equipment: safety considerations. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36(Suppl 2):126. doi: 10.1007/s00247-006-0220-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernanz-Schulman M, Goske MJ, Bercha IH, et al. Pause and pulse: ten steps that help manage radiation dose during pediatric fluoroscopy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:475. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greene DJ, Tenggadjaja CF, Bowman RJ, et al. Comparison of a reduced radiation fluoroscopy protocol to conventional fluoroscopy during uncomplicated ureteroscopy. Urology. 2011;78:286. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ngo TC, Macleod LC, Rosenstein DI, et al. Tracking intraoperative fluoroscopy utilization reduces radiation exposure during ureteroscopy. J Endourol. 2011;25:763. doi: 10.1089/end.2010.0624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Darling S, Sammer M, Chapman T, et al. Physician documentation of fluoroscopy time in voiding cystourethrography reports correlates with lower fluoroscopy times: a surrogate marker of patient radiation exposure. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W777. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levin DC, Rao VM, Bree RL, et al. Turf battles in radiology: how the radiology community can collectively respond to the challenge. Radiology. 1999;211:301. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.2.r99ma05301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]