Abstract

We previously described a check-point for allelic exclusion that occurs at the pre-B to immature B cell transition and is dependent upon IgH intronic enhancer, Eμ. We now provide evidence that the breach in allelic exclusion associated with Eμ deletion results from decreased Igμ levels that make it difficult for emerging B cell receptors (BCRs) to reach the signaling threshold required for positive selection into the immature B cell compartment. We show that this compartment is smaller in mice carrying an Eμ-deficient, but functional IgH allele (VHΔa). Pre-B cells in such mice produce ~50% wild-type levels of Igμ (mRNA and protein), and this is associated with diminished signals, as measured by phosphorylation of pre-BCR/BCR downstream signaling proteins. Providing Eμ-deficient mice with a pre-assembled VL gene led not only to a larger immature B cell compartment but also to a decrease in “double-producers”, suggesting that heavy-chain/light-chain combinations with superior signaling properties can overcome the signaling defect associated with low Igμ-chain and eliminate the selective advantage of “double-producers” that achieve higherIgμ-chain levels through expression of a second IgH allele. Finally, we found that “double-producers” in Eμ-deficient mice include a subpopulation with autoreactive BCRs. We infer that BCRs with IgH chain from the Eμ-deficient allele are ignored during negative selection due to their comparatively low density. In summary, these studies show Eμ's effect on IgH levels at the pre-B to immature B cell transition strongly influences allelic exclusion, the breadth of the mature BCR repertoire, and the emergence of autoimmune B cells.

INTRODUCTION

B lymphocytes develop from progenitor cells in mouse bone marrow (BM) through sequential rearrangements of immunoglobulin heavy (Igh) and light (lgl) chain genes (1, 2). The Igα/Igβ signaling heterodimer associates with protein calnexin on the plasma membrane of pro-B cells, and this complex has been proposed to elicit intracellular differentiation signals for VHDJH gene assembly (3). Igμ is the product of the successfully recombined heavy chain gene (IgH). It assembles with the surrogate light chain (SLC) proteins (λ5 and VpreB), and then with the signaling subunit Igα/Igβ to form a pre-B cell antigen receptor complex (pre-BCR) at the pre-B cell stage (4-6). Subsequently, rearranged immunoglobulin light chains (IgL) replace SLCs and form B cell receptors (BCRs), which define the immature B cell stage (7-9). To achieve a mature B cell population that produces a highly diverse antibody repertoirethat recognizes numerous foreign antigens but lacks anti-self reactivity, B cell development is regulated through intracellular signals propagated by these receptors (9-12). Disruption of any element of the pre-BCR or BCR (the SLC, membrane Igμ, Igα or Igβ) or of the downstream signaling pathways of these receptors blocks B cell development, indicating that not only membrane expression but also the signaling capacity of these receptors are critical for the development and maintenance of the B cell population (10, 13, 14).

To avoid autoimmunity, newly-emerging B cells with self-reactive BCRs must be eliminated or induced to modify their BCR specificity. Cross-linking the BCRs with self-antigen initiates cell signals that lead to cell death, anergy or receptor editing (negative selection) (11, 15, 16). On the other hand, constitutive (tonic or basal) signaling through the pre-BCR and BCR, independent of ligand-binding, is needed to select B cells with functional receptors (positive selection), promoting B cell maturation (17-19). Several different experimental models have suggested that the constitutive signaling strength of the pre-BCR and BCR is directly proportional to their surface densities, since reduced receptor expression translates into diminished tonic signaling, impairing B cell maturation and skewing the development of B cell subsets (20-25). In the current study, we explore the hypothesis that one role of the transcriptional enhancer Eμ is to ensure sufficient Igμ protein levels in pre-B and nascent immature B cells, and thus sufficient BCR density, to support positive selection into the immature B cell compartment.

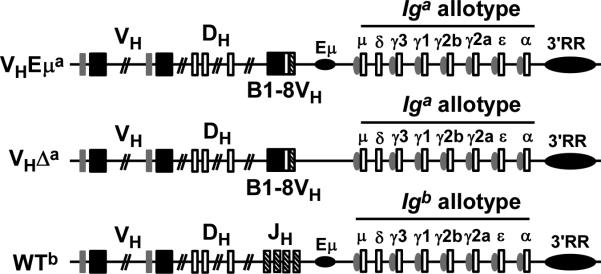

The cis-acting intronic enhancer Eμ, lying between JH and Cμ coding sequences of the Igh locus, has been shown to be essential for efficient heavy chain variable region (VH) gene assembly, and also enhances the transcription of IgH genes (26, 27). In previous studies, we circumvented the need for Eμ in VHgene assembly to study its functions after this process (28, 29). To do this, we created an Eμ-deficient Igha allele with a pre-assembled heavy chain variable region gene (B1-8VH) knocked into the endogenous locus (VHΔa, Fig. 1). We found that, in pre-B cells, this allele was expressed at half the level of an identical but Eμ-intact allele (VHEμa), resulting in ~½ normal cytoplasmic Igμ levels (28). We proposed that this reduction in Igμ expression caused a decrease in the surface density of newly emerging BCRs, thereby reducing BCR-mediated signals and the likelihood of transition to the immature B cell stage. Supporting this hypothesis was our finding that mature, splenic B cells expressing Igμ from only the Eμ-deficient IgH allele (VHΔa single-producers) had undergone unusually extensive light-chain editing, the process that has been described previously as a means by which an emerging B cell replaces its autoreactive receptor with an innocuous one(28, 30). We suggested that in this case, however, light-chain editing was occurring because of weak BCR signals (low Igμ) that were insufficient to indicate formation of a functional BCR and thus turn off the recombination machinery (the recombination-activating genes RAG-1 and RAG-2). Only when a light chain was found that could combine with the B1-8Igμ-chain and somehow increase the BCR signal beyond the threshold for positive selection, would an individual pre-B cell transit to the immature B cell stage. Three predictions of this hypothesis are that B1-8 H-chainBCR signals in developing pre-B cells of VHΔa/WTb mice are of lower mean strength than their counterparts in VHEμa/WTb animals, that this results in less efficient generation of the immature B cell pool, and that the rate of the pre-B to immature B cell transition in these Eμ-deficient animals should be responsive to changes in Ig light-chain availability and structure. We test these predictions in the current study.

Figure 1. Diagram of wild-type (WTb) and B1-8VH knock-in loci with and without Eμ (designated VHEμa and VHΔa respectively).

Exons are shown as boxes, enhancers are indicated as horizontal ovals (Eμ; 3’ regulatory region = 3’RR), “switch” sequences (sites of class-switch recombination) upstream of the constant region genes are indicated as vertical ovals, constant regions are labeled (e.g. μ, δ, etc.). B1-8VH is the pre-assembled VH gene that is inserted in place of the joining gene (JH) region. As indicated, the constant region genes in the knock-in loci are of the Iga allotype while they are of the Igb allotype in the WT locus. The WTb allele in the heterozygotes is in the germline configuration, but if functionally rearranged, it would produce an Igμb chain distinguishable from that produced by the knock-in loci (Igμa).

Another striking feature of mice heterozygous for the Eμ-deficient allele (VHΔa/WTb) was a defect in allelic exclusion in both the immature and mature B cell pools(28). Approximately 20% splenic B cells expressed Igμ from both the VHΔa knock-in allele and a functionally-rearranged WTb allele (“double-producers”). We found that the B1-8VH knock-in on the Eμ-deficient Igha allele (VHΔa) or on the allele with Eμ (VHEμa) inhibited VH-DJH recombination on the wild-type Ighb allele to the same extent (28). Rare pre-B cells that circumvented this inhibition were present in both VHΔa/WTb and VHEμa/WTb animals. However, thesegave rise to a significant number of “double-producers”, immature B cells only in the VHΔa/WTb mice but not in the VHEμa/WTb animals, revealing an Eμ-dependent “check-point” for IgH allelic exclusion at the pre-B to immature B cell transition. We suggest that this, in fact, is another manifestation of the inability of the VHΔa allele to produce Igμ, and therefore BCR, at levels sufficient for positive selection. Since the functionally assembled IgH gene on the WTb allele retains Eμ, it allows for BCR levels sufficient for positive selection, putting such double-producers at a selective advantage over single-producers (no Eμ) in VHΔa/WTb mice. In the current study, we have tested this hypothesis by asking whether genetic manipulations that augment the pre-B to immature B cell transition for VHΔa/WTb single-producers simultaneously augments allelic exclusion (i.e. reduces numbers of double producers). We discuss our results in the context of other studies of allelic exclusion (31, 32).

Finally, an early prediction made by Burnet, when describing his theory of clonal immune cell selection, was that cells with receptors of more than one specificity would be at risk of co-expressing both protective and autoreactive receptors (33). Since VHΔa/WTb mice produce such cells (double-producers) at a high rate, we have analyzed these cells for evidence of autoimmunity. As described here, we find that these cells are prone to produce dsDNA-specific antibodies, and we discuss the cell selection process that we believe explains their persistence in the peripheral B cell repertoire.

In summary, the current study addresses a fundamental question about the role of IgH intronic enhancer, Eμ, in B cell development and selection. We suggest that besides its role in VH gene assembly, Eμ plays a critical role in the expression of newly formed Igμ genes in pre-B cells. By augmenting Igμ gene expression in these cells, Eμ ensures that most IgH/IgL combinations (emerging BCRs) reach a level sufficient to signal positive selection, and, in those instances where the BCR is autoreactive, to signal negative selection. In this way, a transcriptional enhancer serves to support the development of a broad and protective repertoire, and guards against the development of cells expressing dual receptors with autoreactive properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

VHEμa/VHEμa mice with B1-8VH (a pre-assembled VHDJH gene segment) knock-in on both Igh loci, originally described as B1-8i mice, were supplied by Dr. K. Rajewsky (CBR Institute for Biomedical Research, Boston, MA) (34). The VHΔa/VHΔa mouse line carries the same B1-8VH knock-in but with Eμ removed (28). Both mouse strains were crossed to C57BL/6J mice (WTb/WTb) (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, stock #000664) to generate VHEμa/WTb and VHΔa/WTb heterozygotes. In some cases, the heterozygotes were intercrossed and analyzed. ΔJH/ΔJH mice lack both Eμ and the JH gene segments within the Igh locus, precluding VH region gene assembly (35) (The Jackson Laboratory, B6.129P2-Igh-Jtm1Cgn/J; stock #002438). They were mated to VHEμa/VHEμa and VHΔa/VHΔa mice to generate VHEμa/ΔJH and VHΔa/ΔJH offspring.

RAG1−/− mice are homozygous for RAG1 gene deletion (36) (The Jackson Laboratory, B6.129S7 RAG1 <TM1MOM>/J; stock #002216). They are immunodeficient as they lack both mature B and T lymphocytes. VHEμa/VHEμa and VHΔa/VHΔa mice, mated with RAG1−/− mice on the C57BL/6 background, resulted in VHEμa/WTb RAG1−/− and VHΔa/WTb RAG1−/− progeny. B cell development in these progeny stalls at the pre-B cell stage because of the cells’ inability to undergo light chain gene rearrangements without Rag1 protein.

3-83κ/3-83κ mice with the pre-assembled 3-83Vκ knock-in gene, were supplied by Dr. R. Pelanda (National Jewish Heath, Denver, CO). A previous study showed that the B1-8VH/3-83κ combination yields a BCR with innocuous specificity (37). All mice were maintained under pathogen-free conditions in the Animal Facility at Hunter College, The City University of New York. Hunter College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee reviewed and approved all protocols.

Genotyping by PCR

Presence or absence of Eμ and presence of the B1-8VH knock-in were detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), as were wild-type (germline configuration) Igκ, 3-83κ, wild-type RAG1, and RAG1-deletion loci. Genotyping PCRs were performed with HotStar Plus Taq polymerase (Qiagen, Cat.#203646) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Primers used to amplify tail-tip genomic DNA included: primer numbers 2 & 4, VDJ junction primer, and JH4f (previously described, (28)); primer E3HR (previously described, (29)); wild-type Igκ (forward primer): 5’-GATTCTGGCACTCTCCAAGG-3’ (between Jκ1 and Jκ2 of the WT κ locus; nucl. 39919879-39919898, GenBank NT_039353); wild-type Igκ (reverse primer): 5’-CCAACCTCTTGTGGGACAGT-3’ (between Jκ2 and Jκ3 of the WT κ locus; complementary to nucl. 39920274-39920293, GenBank NT_039353); 3-83κ knock-in (forward primer): 5’-GCGGCCGCACACTATATTTTCCTCCTTC-3’ (upstream of 3-83Vκ coding sequences); 3-83κ knock-in (reverse primer): 5’-GTCGACAACACACAACAAAGAACAAC-3’ (3’end of 3-83Vκ coding sequences); The Jκ1 and Jκ2 region is missing on the 3-83κ knock-in locus, and 3-83κ knock-in primers are both within the 3-83Vκ insertion, which replaces Jκ1-Jκ2 on the WT κ locus (38). RAG1 gene primers and products are described elsewhere (http://jaxmice.jax.org/protocolsdb/f?p=116:2:1551375113031153::NO:2:P2_MASTER_PROTOCOL_ID,P2_JRS_CODE:329,002216). Primer number 4 and E3HR generate an 834 bp product from only the VHEμa allele, but not other Igh alleles. Primer number 2 and VDJ junction primer are specific for the VHΔa allele and generate a 387 bp product. JH4f and primer E3HR generate a 249 bp product from only the wild type Igh (WTb) locus. Wild-type Igκ primers anneal to wild type kappa locus and generate a 415 bp product. 3-83κ knock-in gene primers anneal to 3-83κ gene and generate a 1.1 kb product.

Real-time RT-PCR

To quantify RAG2 and germline Ig-kappa transcripts in pre-B cells, bone marrow B cells were first enriched by positive selection for B220+ cells using the B220 MicroBeads kit (Miltenyi Biotech). Total RNA was extracted by RNeasy mini-prep kit (Qiagen, Cat.#74104), and treated with RNase free DNase (Qiagen, Cat.#79254) to remove genomic DNA. RNA solutions were adjusted to 100 μg/ml in RNase-free water.

One-step, real-time reverse-transcriptase (RT)-dependent PCRs were performed on the isolated RNAs, using the QuantiFast SYBR Green RT-PCR kit (Qiagen, Cat.#204154). Primers for κ germline transcripts (0.8 kb(39); GenBank NT_039353) were 5′-CAGTGAGGAGGGTTTTTGTACAGCCAGACAG-3′ (forward, immediately upstream of Jκ1; nucl. 39919702-39919732) and 5′-CTCATTCCTGTTGAAGCTCTTGACAATGGG-3′ (reverse, within Cκ; complementary to nucl. 39923911-39923940). Primers for detecting RAG2 mRNA were from Qiagen (QuantiTect Primer Assay, QT00253414). Samples were normalized using primers for mRNA from the housekeeping gene hgprt1 (hypoxanthine/guanine phosphoribosyl transferase; QuantiTect Primer Assay, QT00166768). PCR reactions were performed on the 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Data were analyzed with the software supplied by Applied Biosystems (User bulletin #2). Reverse-transcriptase negative controls were included to exclude the possibility of genomic DNA contamination.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

For IgMa and IgMb proteins

VH knock-in (IgMa) and wild-type (IgMb) antibodies were distinguished in a sandwich-type ELISA, using allotype-specific antibodies. Biotinylated mouse anti-mouse IgMa antibody (BD Biosciences, Cat.#553515) or biotinylated mouse anti-mouse IgMb antibody (BD Biosciences, Cat.#553519) was used to detect a or b allotype IgM. For both qualitative and quantitative ELISAs, 96-well immunoplates (NuncMaxisorp, Thermo Scientific) were coated with rat anti-mouse IgM antibody (BD Biosciences, Cat.#553405). Plates were then blocked with 3% BSA (bovine serum albumin with 0.1% NaN3 in phosphate-buffered saline, PBS). To quantify IgMa, mouse sera and culture supernatants were diluted and each dilution was analyzed in duplicate. Biotinylated anti-allotype antibodies were added, and detected by streptavidin-horse radish peroxidase (SA-HRP; BD Biosciences, Cat.#554058). ABTS (Southern Biotech, Cat.#0401-01) was used as the substrate for HRP. Plates were read at 405 nm, using the PowerWave HT microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek, Winooski, VT), and data were analyzed by the software Gen5 (BioTek). A titration curve for each assay was generated with purified mouse immunoglobulin of the relevant Ig allotype. OD405 of all tested samples was in the linear range of the assay.

For anti-dsDNA antibody

Detection of IgMa anti-dsDNA antibodies by ELISA was performed as previously described by others (40). Briefly, calf thymus DNA (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat.#D1501) was sonicated and purified by phenol extraction, and then was diluted to 100-150 μg/ml in PBS and filtered through a 0.45 μm microcellulose filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA) to remove ssDNA. 100 μl dsDNA solution was added to each well of the Immulon-2 HB 96-well plate (Dynatech, Chantilly, VA). Plates were dried for 48 hours at 37°C and blocked with 3% BSA in PBS (pH 7.4). Culture supernatant or diluted sera samples from mice of various genotypes were added and incubated for 2 hours at 37°C. Binding of IgMa molecules to dsDNA was revealed by biotinylated mouse anti-mouse IgMa antibody and streptavidin-HRP. A purified mouse monoclonal IgMa anti-dsDNA antibody, kindly provided by Dr. L. Spatz (Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education, City College of New York), was also serially diluted, beginning with a concentration of 0.5 μg/ml and was used to generate a standard curve. OD405 of all samples analyzed was in the linear range of the standard curve. The relative amounts of IgMa anti-dsDNA antibodies were normalized to IgMa protein levels (total amount of IgMa in each sample was quantified by ELISA as described above). Consistency of all ELISA results was confirmed by 3 repeated assays of each sample.

B cell isolation and culture

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from bone marrow and spleen in cold RPMI-1640 media (Mediatech, Inc. Cat.#17-104-CI) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat.#SH30070.03). ACK lysis buffer (0.15 M NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, and 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) was used to lyse erythrocytes. In some cases, B lineage cells were isolated by magnetic cell sorting. Bone marrow B lineage cells were positively selected with MACS B220 MicroBeads kit (Miltenyi Biotech, 130-049-501), and splenic B cells were enriched by negative selection of CD43-expressing cells with CD43 microbeads (B cell isolation kit, mouse, Miltenyi Biotech, 130-090-862). For some experiments, a FACSVantage (BD Biosciences) was used to identify and separate IgMa+b+ and IgMa+b− cells before placing these separate populations into culture.

For lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated cultures, splenic B cells isolated from 10-week-old mice were cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2, for 7 days starting at a density of 5 × 105 cells/ml in RPMI full media (RMPI-1640, supplemented with 20% FBS; 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, Life Technologies, Cat.#21985-023; 2 mM L-glutamine, Life Technologies, Cat.#25030-081; 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, Life Technologies, Cat.#15140-122; 100 μM non-essential amino acids, Life Technologies, Cat.#11140-050) with 25 μg/ml LPS (Escherichia coli, serotype 055:B5; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat.#L6511). Cell supernatants were collected and assayed by ELISA for the presence of IgMa antibodies to dsDNA and for total IgMa antibodies.

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained for surface and intracellular molecules by standard procedures. In general, 1 × 106 cells were incubated with monoclonal antibodies in FACS staining buffer (1x PBS, 5.6 mM glucose, 0.1% BSA, and 0.1% NaN3), at 4°C for 20 min. Monoclonal antibodies from BD Biosciences included: fluorescein-isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated anti-mouse IgM (BD553408), anti-mouse IgMa (BD553516), anti-mouse Igκ (BD550003); phycoerythrin (PE) conjugated anti-mouse IgMb (BD553521), anti-mouse CD43 (BD553271); allophycocyanin (APC) conjugated anti-mouse B220 (BD553092). Biotin-conjugated antibodies were revealed with streptavidin-PE (BD554061). Monoclonal antibodies from Southern Biotech included: PE conjugated anti-mouse Igλ (Cat.#1175-09), and biotin conjugated anti-mouse IgD (Cat.#1120-08). Dead cells were excluded from analysis by propidium iodide staining.

For cytoplasmic Igμ, Igκ and Igλ staining, bone marrow cells were isolated and incubated with an antibody to B220 (and/or antibodies to other cell surface molecules, as appropriate for the experiment). Cells were then fixed and permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences, Cat.#554714) buffer. Intracellular Igμ was stained with FITC conjugated anti-mouse IgM (BD553437), and intracellular Igκ and Igλ were revealed by antibodies described above.

To detect the phosophorylation status of intracellular signaling molecules, freshly isolated single-cell suspensions (1 × 106 ~ 5×106 bone marrow cells) were surface stained with anti-B220-APC (in some cases also anti-sIgM-PE, BD553409 or anti-sIgM-FITC, BD553408), and then incubated for 5 minutes in prewarmed (37°C) RPMI 1640 medium (upto 5×106 cells/ml). Sodium pervanadatewas then added immediately into the cell suspension to a final concentration of 60 μM and incubated for another 5 minutes at 37°C. Sodium pervanadate inhibits intracellular tyrosine phosphatases, and has been used to analyze the relative amount of tyrosine-phosphorylated protein, which is an indicator of the activity of signaling pathways (17, 18, 41, 42). Cells were washed with PBS, then fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer and incubated with anti-pSyk (BD560081), anti-pErk (BD612592), anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (BD558008) or one of the corresponding isotype matched control antibodies with irrelevant specificity. For phosphorylated Syk: the mouse anti-Syk antibody (I120-772) is specific for mouse Syk phospholytation site tyrosine 342 (pY342). For phosphorylated Erk: the mouse anti-Erk1/2 monoclonal antibody (20A) recognizes the phosphorylated threonine 203 and tyrosine 205 (pT203/pY205) residues in murine Erk1, and the T183/Y185 in murine Erk2. For phosphorylated total tyrosine: the mouse anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (PY20) detects all phosphorylated tyrosine residues.

For all flow-cytometry experiments, cell analysis was on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences), data were acquired with CellQuest (FACS instruments), and data were further analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.). Lymphocytes were gated according to side and forward scatter, and further gates were applied as described in individual experiments.

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests for differences among the mouse lines were performed with GraphPad Prism 5 software. Student's unpaired two-tailed t-test was used to assess the statistical significance of the differences. Differences with a p-value of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Immature B cell compartment is diminished in the bone marrow of Eμ-deficient mice

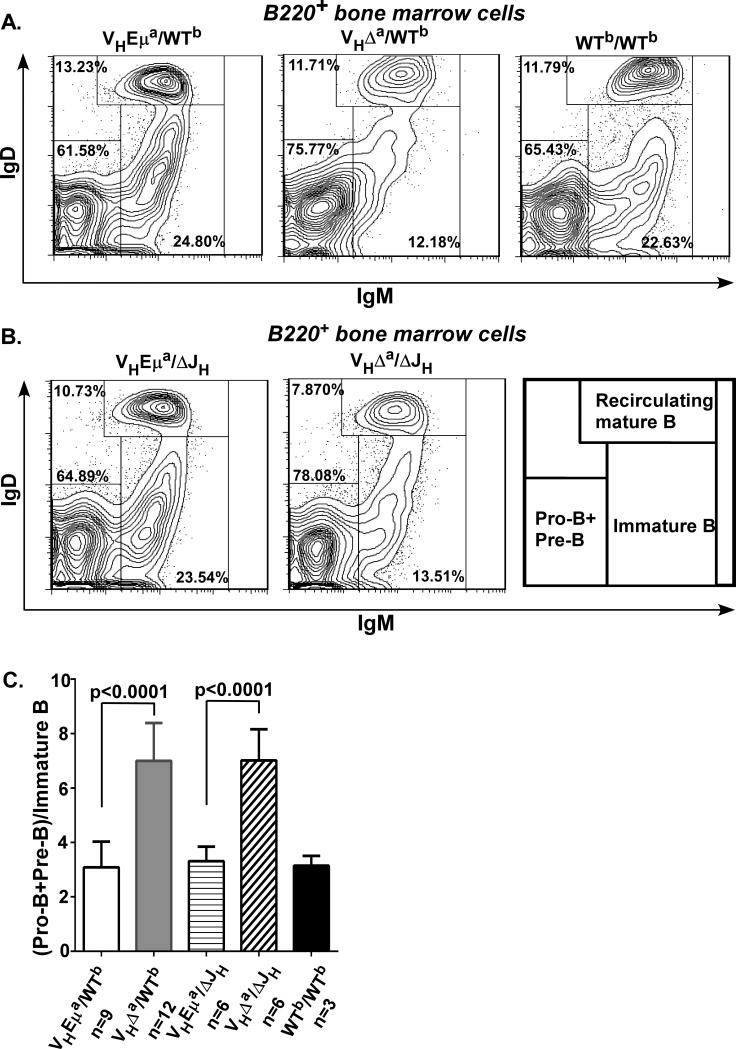

To test the hypothesis that pre-B cells expressing only an enhancer-deficient IgH gene often fail positive selection into the immature B cell compartment, we compared the relative sizes of the pre-B and immature B cell subsets in the bone marrow of B1-8VH knock-in heterozygous mice that retained (VHEμa/WTb) or lacked Eμ (VHΔa/WTb). Because of the B1-8VH knock-in, B cells largely bypass the pro-B cell stage, rapidly progressing to the pre-B cell stage. Antibodies to cell surface markers B220, IgM and IgD were used to identify pro- and pre-B cells (B220+IgM−IgD−), immature B cells (B220+IgM+IgD−), and mature, recirculating B cells (B220+IgM+IgD+). Wild-type C57BL/6 (WTb/WTb) mice were also analyzed as a control. In these control mice, the B220+IgM−IgD− compartment includes not only pre-B cells, but also pro-B cells undergoing VH region gene recombination. As shown in Fig. 2A, the immature B cell compartment in VHΔa/WTb mice (12.18% of total B220+ cells) was ½ the size of that in VHEμa/WTb (24.80%) and WTb/WTb (22.63%) mice. Although the majority (~90%) of immature B cells in VHΔa/WTb mice express only the VHΔa allele(28), the co-expressed WTb allele in “double-producer” precursors could serve to drive at least these cells through the pre-B to immature B cell transition. We therefore also examined B cell subpopulations in “hemizygous” mice where B cell development is entirely dependent upon the knock-in loci. This was done by making the VHEμa and VHΔa alleles heterozygous with an allele that lacks the JH gene segments (ΔJH; no VHregion gene assembly possible). As shown in Fig. 2B, the immature B cell compartment in VHΔa/ΔJH mice was also ~½ that of the VHEμa/ΔJH mice (13.51% versus 23.54%). Data from multiple mice of these and the VHEμa/WTb, VHΔa/WTb and WTb/WTb genotypes were quantified in the bar graphs of Fig. 2C. In all cases, the ratio of Eμ-deficient pro-/pre-B to immature B cells was twice that of Eμ-intact ones, demonstrating that presence of the VHΔa allele resulted in a less efficient transition from the pre-B to immature B cell stage.

Figure 2. Immature B cell compartment is diminished in VHΔa/WTb and VHΔa/ΔJH mice.

A. Representative flow-cytometry plots of bone marrow cells gated for B220+ (B-lineage cells) and analyzed for IgD and IgM surface expression: mature B cells (IgD+IgM+), immature B cells (IgD−IgM+), pro-B+pre-B cells (IgD−IgM−). Gates and percentage cells in gates are indicated (% calculated relative to total B220+ cells). VHΔa/WTb = heterozygous for the wild-type (Ighb) allele and the Eμ-deficient allele with B1-8VH knock-in; VHEμa/WTb differs from VHΔa/WTb only by virtue of the presence of Eμ on the B1-8VH knock-in allele. Both of the knock-in lines are on the C57BL/6 background; WTb/WTb = normal C57BL/6 mouse as control.

B. Representative flow-cytometry plots of bone marrow B-lineage cells from hemizygous VH knock-in mice (VHEμa/ΔJH and VHΔa/ΔJH). Since the allele lacking the JH region (ΔJH) cannot assemble a VH gene, the “knock-in” allele is effectively “hemizygous”. Analyses as in A.

C. Quantification of flow-cytometry data from the indicated numbers (n=) of mice of each genotype. Genotypes explained in A and B above. Ratios of (pro-B + pre-B) to immature B cells are compared (thereby leaving aside comparisons of re-circulating, mature B cells). Animals were age-matched (3-4 months). Error bars indicate Standard Deviation (SD); p-values for differences in means were determined by two-tailed t test obtained (GraphPad Prism 5).

Since broader changes in cell numbers in the bone marrow of these animals could be missed by the above analyses, and to ask whether the observed increase in the ratio of pre-B to immature B cells was due to an abnormal expansion of pre-B cells, absolute cell numbers were determined for each bone marrow subpopulation. The results were consistent with those described above: the only difference among the various genotypes was a reduction of immature B cell numbers in both VHΔa/WTb and VHΔa/ΔJH animals (Supplemental Table). We conclude that in the bone marrow of Eμ-deficient mice, there was no evidence for extra pre-B cell accumulation, but immature B cells did not emerge in normal numbers.

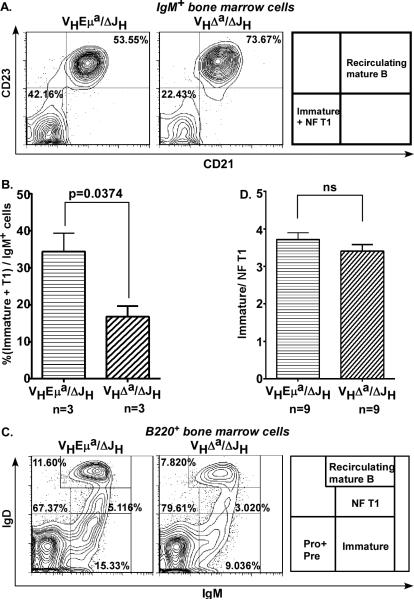

Absence ofEμ does not adversely affect cell development after the immature B cell stage

Immature B cells give rise to “transitional” B cells, and the first in a phenotypically-distinguishable series of such cells is the T1 B cell in the bone marrow. The surface markers CD21, CD23, IgM, and IgD were used to compare the newly formed T1 (NF T1) B cell compartments in the bone marrow of VHEμa/ΔJH and VHΔa/ΔJH mice. Among IgM+ B cells in the bone marrow, the CD21−CD23− cells constitute the combined pool of immature and NF T1 B cells. As shown in Fig. 3A and 3B, this combined pool in VHΔa/ΔJH mice was ½ the size of that in VHEμa/ΔJH mice (22.43% versus 42.16%), consistent with the diminished immature B cell pool in these animals. However, the ratios of immature to NF T1 B cells (distinguished by levels of IgD and IgM expression, (43-46)) were indistinguishable in these two mouse strains (3.72±0.18 versus 3.41±0.18; Fig. 3C, D). The reduced NF T1 B cell compartment in mice expressing the Eμ-deficient allele, therefore, was directly related to the smaller number of immature B cell “precursors” from which they arose. There was no evidence that the efficiency of NF T1 cell development was itself compromised.

Figure 3. Immature and transitional (T1) B cells are found at similar ratios in VHEμa/ΔJH and VHΔa/ΔJHmice.

A. Representative flow-cytometry plots of bone marrow cells gated for IgM+, and analyzed for CD23 and CD21 surface expression. Quadrants for recirculating, mature B cells (CD21+CD23+) and for a mixture of immature B and NF T1 (newly-formed T1) B cells (CD21−CD23−) are indicated. Percentage cells are calculated relative to total IgM+ cells.

B. Bar graphs comparing immature+NF T1 B cell pools in VHEμa/WTb and VHΔa/WTb mice (gated as shown in A. Three (n=3) age-matched animals (2-3 months) of each genotype were analyzed. Error bars show SD. p-value calculated by a two-tailed student's t test.

C. Representative flow-cytometry plots of bone marrow cells gated for B220+ and analyzed for IgM and IgD expression. Gates are shown for immature B cells (IgM+IgD−), NF T1 B cells (IgM+IgDlow), and recirculating, mature B cells (IgM+IgDhigh). Percentage cells are calculated relative to total B220+ cells.

D. Ratios of IgD−/IgDlow (immature/NF T1) B cells in the bone marrow of VHEμa/ΔJH and VHΔa/ΔJH mice. Subsets gated as in C. Numbers of mice analyzed are indicated (n=); mice were 2-3 months of age. Error bars show SD. ns = non-significant (calculated by two-tailed student's t test).

It has been shown by others that, while continuous pre-B cell input is necessary for maintaining a peripheral B cell compartment, the size of that compartment is independent of pre-B cell numbers. In other words, peripheral B cells reach homeostasis autonomously (47). For this reason, it was not surprising to find normal B cell numbers in spleens of VHΔa/WTb mice, despite the immature B cell deficiency evident in the bone marrow ((28) and data not shown). On the other hand, in the spleens of neonatal mice, mature B cells are essentially absent, and, instead, immature B cells predominate throughout the first week of life (48). Consistent with this, B cells in the spleens of VHΔa/WTb newborn mice (analyzed on the day of birth) were ~½ the number found in VHEμa/WTb newborns (Supplemental Fig. 1). We conclude that the early wave of immigrants to spleen is reduced in size in the Eμ-deficient mice, but this is later masked in adult spleen by homeostatic, as well as antigen-induced, B cell proliferation (49).

In summary, when Eμ is missing, B-cell development is impaired at the pre-B to immature B cell transition such that mice do not form an immature B cell compartment of normal size. B cells at other stages of development, however, including the earlier pre-B and the later transitional and mature B cell stages, are unaffected by Eμ's absence.

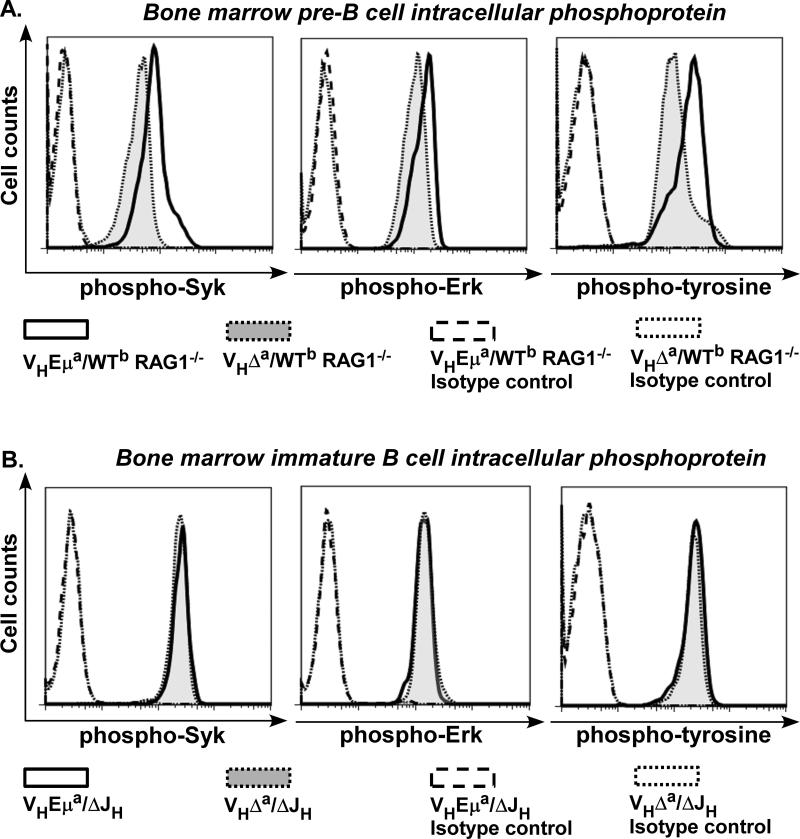

Weaker pre-BCR signaling in the small pre-B cells of VHΔa mice

Light chain gene assembly, with the consequent formation of a signaling-competent B cell receptor, is essential for the transition from pre-B to immature B cell stage. Having confirmed that this transition was compromised in VHΔa/WTb and VHΔa/ΔJH mice, we asked whether the defect could be explained by a decrease in BCR-mediated signaling in cells with newly-formed receptors. In pre-B cells, pre-BCR signals dominate over newly-emerging BCRs because light chain gene assembly is ongoing (i.e. most pre-B cells lack a functional Ig-light chain gene). While our interest was in the signals of newly emerging BCRs, we reasoned that any change in their signal due to the reduced Igμ (as observed in VHΔa/WTb pre-B cells) would similarly affect pre-BCR signals in these cells. We therefore focused on pre-BCR signals in VHΔa/WTb and VHEμa/WTb mice since the receptor structure was identical in both (B1-8 Igμ/SLC), but the amount of Igμ available for pre-BCR assembly differed significantly.

VHEμa/WTb and VHΔa/WTb mice were bred onto the RAG1−/− background, thereby restricting signals to those mediated by the pre-BCR. As previously reported, the progression from pro-B, through large pre-B, to small pre-B cells was the same in both resulting mouse strains, but Igμ expression was reduced in the pre-B cells from VHΔa/WTb RAG1−/− mice to 50% of the levels seen in pre-B cells from VHEμa/WTb RAG1−/− mice ((28) and Supplemental Fig. 2).

Pre-BCR/BCR induces a series of tyrosine phosphorylation to control B cell differentiation and selection (14, 19). Bone marrow B cells from both strains were treated with the protein-tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) inhibitor sodium pervanadate in order to analyze tonic signals mediated by the pre-BCR (17, 50). Sodium pervanadate blocks the activity of intracellular PTPs, thereby stabilizing receptor signals (17, 51). The cells were then permeabilized and incubated with antibodies specific for phosphorylated Erk (pErk, extracellular signal regulated kinase), for phosphorylated Syk (pSyk, spleen tyrosine kinase), and for phospho-tyrosine residues, in general (pTyr). Others have shown that Syk and Erk kinases are essential for both pre-BCR and BCR signaling (25, 52-56), and their phosphorylation depends upon and is directly proportional to B cell receptor signal strength.As shown in Fig. 4A, mean levels of these phosphorylated kinases (and of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins, in general) were lower, in every case, in VHΔa/WTb RAG1−/− pre-B cells.

Figure 4. Pre-BCR signals are attenuated in the small pre-B cells of VHΔa/WTb RAG1−/− mice.

A. Histograms of pre-B cells stained with antibodies to the phosphorylated (activated) forms of the indicated proteins. B220+ cells from bone marrow of VHEμa/WTb RAG1−/− and VHΔa/WTb RAG1−/− mice were treated with the phosphatase inhibitor pervanadate and then fixed and permeablized before incubation with antibodies. pErk = phosphorylated form of “extracellular signal-regulated kinase”; pSyk = phosphorylated form of “spleen tyrosine kinase”; pTyr = phosphorylated tyrosine residues on any/all cell proteins. Controls are pre-B cells stained with isotype-matched antibodies (no specificity for mouse proteins). Histograms shown are representative of 3 independent experiments with 2 month-old mice of the indicated genotypes.

B. Histograms of immature B cells stained with antibodies to the phosphorylated (activated) forms of the indicated proteins as discussed in A. B220lowsIgM+ bone marrow cells from bone marrow of VHΔa/ΔJH and VHEμa/ΔJH mice were analyzed. Histograms shown are representative of 3 independent experiments with 2.5 month-old mice of the indicated genotypes.

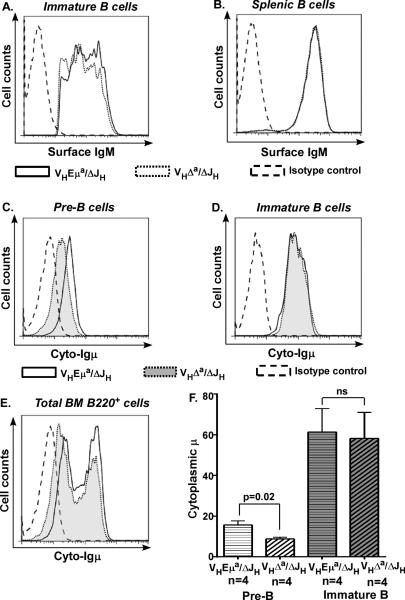

BCR signaling is normal in the immature B cell compartment of Eμ–deficient mice

The BCR signals in immature B cellsrepresent only those sufficient to promote cell survival through both positive and negative selection. Furthermore, we and others have suggested that once cells reach the immature B cell stage, Eμ is no longer required for normal levels of Igμ mRNA and protein (57-59). This is because the 3’ regulatory region (3’RR, a downstream regulatory region at the 3’ end of the Igh locus, Fig. 1) becomes active and can efficiently enhance Igμ expression at this stage. We compared Igμ protein levels in pre-B, immature and mature B cells of VHEμa/ΔJH and VHΔa/ΔJH mice. As pointed out above, B cell development and BCR expression in these mice are entirely dependent upon the VHEμa and VHΔa alleles, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5A, surface IgM levels varied over a broad range in immature B cells from these mice, but the overall profiles overlapped when Eμ was and was not present on the knock-in allele (VHEμa/ΔJH and VHΔa/ΔJH cells, respectively). Similarly, as has been reported before for VHEμa/WTb and VHΔa/WTb mice (28), splenic B cells from VHEμa/ΔJH and VHΔa/ΔJH mice expressed identical levels of surface IgM (Fig. 5B). Cytoplasmic Igμ levels in immature bone marrow cells did not differ between these two genotypes (Fig. 5D, 5F). This contrasts with what was seen in pre-B cells from the same animals. As in VHΔa/WTb RAG1−/− mice (Supplemental Fig. 2C, 2D), cytoplasmic Igμ levels were reduced in VHΔa/ΔJH pre-B cells to almost ½ that in VHEμa/ΔJH pre-B cells (Fig. 5C, 5F). Reduced cytoplasmic-Igμ in pre-B cells and normal cytoplasmic-Igμ levels in immature/mature BM B cells were also evident when the entire population of B220+ bone marrow cells were analyzed (Fig. 5E). Note that the peaks corresponding to cells with high levels of cytoplasmic Igμ (immature/mature B cells) were juxtaposed for B220+ of both genotypes, but the peak for cells with comparatively low cytoplasmic-Igμ (pre-B cells) were displaced from one another, with the peak from VHΔa/ΔJH pre-B cells lying left (lower cytoplasmic-Igμ) of that from VHEμa/ΔJH pre-B cells. In summary, the Eμ-deficient allele produced significantly less Igμ proteins in pre-B cells than did the same gene with Eμ present, but this deficiency was no longer evident in immature B cells (nor in splenic B cells).

Figure 5. Igμ is not reduced in immature B cells expressing an Eμ-deficient allele.

A. Representative histogram of surface IgM-staining on immature B cells of VHEμa/ΔJH and VHΔa/ΔJH mice. Immature B cells identified and gated as B220lowsIgM+. Isotype control = cells incubated with an irrelevant fluorescent antibody with the same isotype as the monoclonal antibody to mouse Igμ. Representative of 4 independent experiments.

B. Representative histogram of surface IgM-staining on splenic B cells of VHEμa/ΔJH and VHΔa/ΔJH mice. B220+ splenic cells were analyzed for surface IgM expression. Representative of 4 independent experiments.

C. Representative histogram of cytoplasmic Igμ-staining in pre-B cells from VHEμa/ΔJH and VHΔa/ΔJH mice. Bone marrow cells gated for B220+sIgM− (pre-B cells). Shown is Representative of 4 independent experiments.

D. Representative histogram of cytoplasmic Igμ-staining in immature B cells of VHEμa/ΔJH and VHΔa/ΔJH mice. Bone marrow cells gated for B220lowsIgM+ (immature B cells). Representative of 4 independent experiments.

E. Representative histogram of cytoplasmic Igμ-staining in bone marrow B220+ cells from VHEμa/ΔJH and VHΔa/ΔJH mice. Peaks on the left correspond to cytoplasmic Igμ in pre-B cells; peaks on right correspond to cytoplasmic Igμ in immature and mature B cells. Representative of 4 independent experiments.

F. Bar graph quantifying cytoplasmic Igμ in pre-B and in immature B cells from bone marrow of VHEμa/ΔJH and VHΔa/ΔJH mice. Mice of each genotype (3 months old) were analyzed in four individual experiments. Error bars show SD. p-value calculated by two-tailed student's t test. ns = non-significant.

We next asked whether this return to equivalent levels of intracellular Igμ (and of surface IgM) would lead to equivalent tonic signaling. B220lowsIgM+ immature B cells from the VHEμa/ΔJH and VHΔa/ΔJH mice were analyzed for signaling in the same manner as described above for pre-B cells. As shown in Fig. 4B, flow-cytometry plots of the phosphorylated (active) forms of the relevant kinases (and overall phosphorylated tyrosine levels) were indistinguishable for the immature B cells from these two mouse strains. This was in striking contrast to the signals from pre-B cells in the same two strains (Fig. 4A).

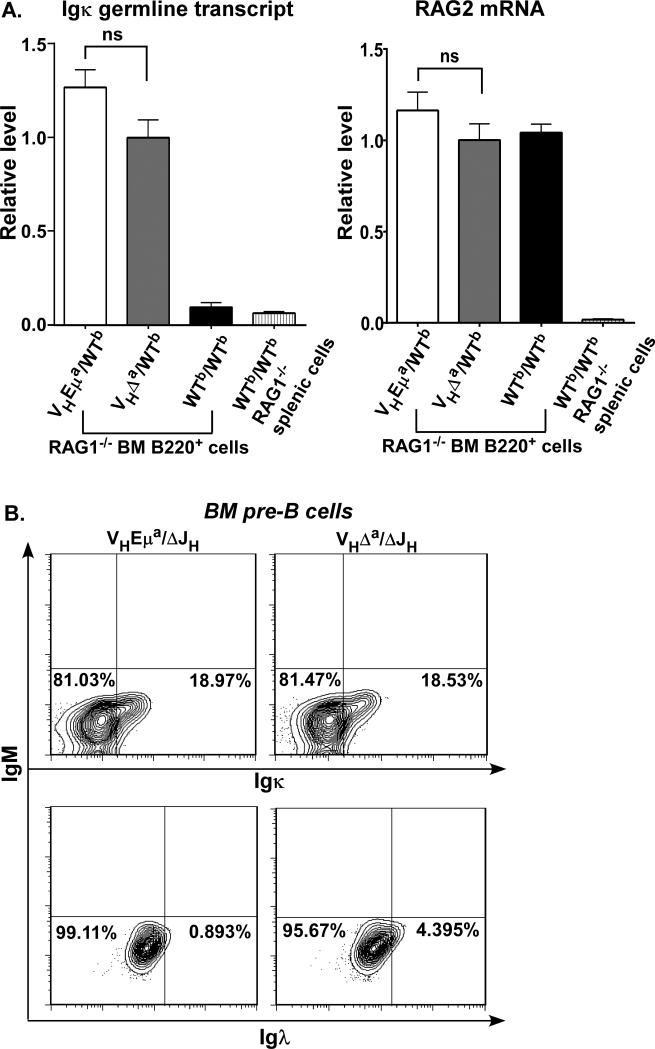

Onset of κ-light chain gene transcription and rearrangement is normal in pre-B cells expressing the Eμ-deficient heavy chain

Since the onset of light chain gene rearrangement is dependent upon pre-BCR signaling (10), and we found that pre-BCR signals were reduced in pre-B cells of VHΔa/WTb RAG1−/− mice (Fig. 4A), we considered the possibility that these reduced signals were responsible for a defect in the activation of light-chain gene assembly, thereby leading to less efficient population of the immature B cell pool. To examine this possibility, we looked at two hallmarks of Igκ locus activation: Igκ germ line transcripts (60) and RAG2 transcription. These were examined by reverse transcriptase-dependent, and quantitative (real-time) PCR. As shown in Fig. 6A, Igκ germ line transcripts and RAG2 transcripts (both essential for subsequent Vκ-Jκ recombination) were present in comparable levels in the pre-B cells from VHEμa/WTb RAG1−/− and VHΔa/WTb RAG1−/− mice. That the Igκ germ line transcripts were dependent upon pre-BCR signals was supported by the fact that B220+ bone marrow cells from RAG1−/− mice without VH knock-in (and therefore unable to make a pre-BCR; WTb/WTb RAG1−/− in Fig. 6A, left panel) were devoid of these transcripts. The same cells from WTb/WTb RAG1−/− mice were positive for RAG2 transcripts (Fig. 6A, right panel), since these are pro-B cells poised to undergo D-JH and VH-DJH recombination but unable to do so because of the absence of RAG1. These results suggested that the onset of light-chain gene rearrangement was not disturbed in VHΔa/WTb pre-B cells, despite the lower pre-BCR signals.

Figure 6. RAG2 and germline kappa light chain (Igκ) gene transcription is normal in pre-B cells of mice expressing the Eμ-deficient allele.

A. Bar graphs comparing RAG2 and germline Igκ transcript levels in B220+ lymphocytes from bone marrow of RAG1-deficient VHΔa/WTb, VHEμa/WTb and WTb/WTb mice. Germline Igκ transcripts (left panel) and RAG2 mRNA (right panel) levels were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Igκ and RAG2 mRNA of VHΔa/WTb RAG1−/− pre-B cells are set as 1.0. Pro-B cells of WTb/WTb, RAG1−/− littermates served as a negative control for Igκ germline transcripts (absence of pre-BCR precludes onset of Igκ transcription) and as a positive control for RAG2 expression (absence of IgH gene assembly sustains expression of the RAG1 and RAG2 genes). mRNAs from WTb/WTb, RAG1−/− splenic cells (no B cells) were included as negative controls for both analyses. All analyses were normalized to hgprt1 mRNA to exclude variations of input RNA templates. Five age-matched animals (2 months) of each genotype were analyzed. Statistical significance (ns: not significant) was determined by two-tailed student's t test.

B. Representative flow-cytometry plots of B220+sIgM− bone marrow lymphocytes (pre-B cells), stained for cytoplasmic Igκ (upper panels) or for cytoplasmic Igλ (lower panels). % positive cells are indicated in the lower right quadrant of each plot. Data are representative of analyses of three age-matched mice (2 months) of each genotype.

In mice that are not deficient for RAG1, Igκ germline transcription and RAG1/RAG2 expression are followed by Vκ assembly and subsequent Igκ protein expression. Vλ assembly and Igλ protein expression can occur later and is generally regarded as evidence of light chain editing (to rescue cells that have not been able to assemble a functional Igκ gene or that express an Igμ/κ BCR with autoreactive properties). We compared percent pre-B cells expressing cytoplasmic Igκ or cytoplasmic Igλ in the pre-B cells of VHEμa/ΔJH and VHΔa/ΔJH mice. The percentages of pre-B cells expressing Igκ were similar in these two mouse strains (18.97% versus 18.53%, Fig. 6B upper panels), again suggesting that onset of Igκ rearrangement was normal in the pre-B cells of VHΔa/ΔJH mice. Interestingly, there was also a detectable subpopulation of pre-B cells expressing cytoplasmic Igλ, but only in the VHΔa/ΔJH mice (4.395%, Fig. 6B lower panels). The latter finding is consistent with our previous study showing increased light-chain editing in splenic B cells from these mice (28). As discussed in more detail later, we believe this light-chain editing resulted not from the expression of autoreactive BCRs but from the inability of many newly-formed BCRs to reach the signaling threshold for transitioning to the immature B cell stage.

In summary, germline Igκ transcripts, RAG2 transcription, and cytoplasmic Igκ protein levels in pre-B cells were unaffected by the deletion of Eμ. We conclude that pre-BCR signaling, while reduced in pre-B cells expressing an Eμ-deficient IgH gene, remained sufficient to induce normal levels of light chain gene assembly. The smaller immature B cell compartment in these animals, therefore, resulted from a deficiency operating after this process.

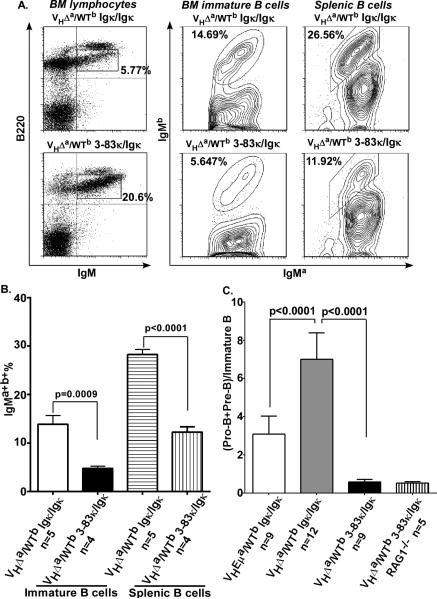

A pre-assembled light chain gene leads to partial rescue of allelic exclusion in mice expressing an Eμ-deficient IgH allele

As described previously, mice heterozygous for a functional, but Eμ-deficient IgH allele (VHΔa/WTb mice) exhibited a profound defect in allelic exclusion, with approximately 20% splenic B cells expressing both the mutant allele and an assembled WTb allele (“double-producers”, (28)). “Single-producers” in the same animals (as well as immature and splenic B cells in VHΔa/ΔJH mice) expressed Igμ exclusively from the Eμ-deficient allele, and such cells showed evidence of having undergone unusually high levels of light-chain editing ((28), and data not shown). We have suggested that both phenotypes result from weak BCR signals (a result of low Igμ) that fail to reach the threshold required for positive selection. To circumvent this problem, cells that have only the Eμ-deficient allele available for expression (“single-producers”) continue to edit their light chain until they generate a BCR with superior signaling ability, while the assembled IgHb allele in “double-producers”, because it retains Eμ, reverses the Igμ deficiency, giving these cells a selective advantage.

To further test the hypothesis that light chain editing in single-producers is functionally related to the outgrowth of double-producers in VHΔa/WTb mice, we asked whether limiting cells to a single light chain sequence would not only affect the pre-B to immature B cell transition of single-producers but also the relative advantage afforded to double-producers in the same animals. VHΔa/WTb micewere bred to a strain carrying a functional 3-83Vκ knock-in (a pre-assembled κ light chain variable region gene) within the Igκ locus. B cell subpopulations were compared in the resulting VHΔa/WTb 3-83κ/Igκ versus VHΔa/WTb mice. As shown in Fig. 7, the relative size of the immature B cell pool was greatly increased in the presence of the 3-83Vκ knock-in (Fig. 7A left panel and Fig. 7C). Importantly, this increase was accompanied by fewer double-producers in both the immature and splenic B cell compartments (Fig. 7A middle and right panels and Fig. 7B). Igλ-producing cells were also reduced in number by the 3-83Vκ knock-in light chain (from 11.3% to 4.7% splenic B cells; Supplemental Fig. 3). We interpret these results as evidence that the B1-8VH/3-83Vκ combination results in a BCR with stronger signaling properties than the average BCR in cells expressing a wide repertoire of light-chain genes. The result is more rapid progression from pre-B to immature B cell stage and a reduction in the selective advantage of double-producers over single-producers in these animals.

Figure 7. 3-83κ knock-in gene reduces the incidence of double-producers in VHΔa/WTb mice.

A. Left panels: Flow cytometry profiles of bone marrow cells gated for lymphocytes, and analyzed for B220 and IgM expression. B220lowIgM+ = immature B cells (% immature B cells indicated). Middle panels: Flow cytometry profiles of bone marrow immature B cells as gated on the left, analyzed for IgMa and IgMb expression (% double producers within immature B cell population indicated). Right panels: Flow cytometry profile of B220+ splenic cells (B cells), analyzed for IgMa and IgMb expression (% double producers within splenic B cells indicated). Data shown are representative of at least 4 age-matched animals (3-4 months) of each genotype.

B. Data of double-producers as analyzed in A. n= number of animals analyzed. p-value determined by two-tailed student t test. Error bars show SD.

C. Ratios of pro/pre-B to immature B cells in the bone marrows of indicated genotypes (calculated as in Fig. 2). n= number of animals analyzed. p-value determined by two-tailed student t test. Error bars show SD.

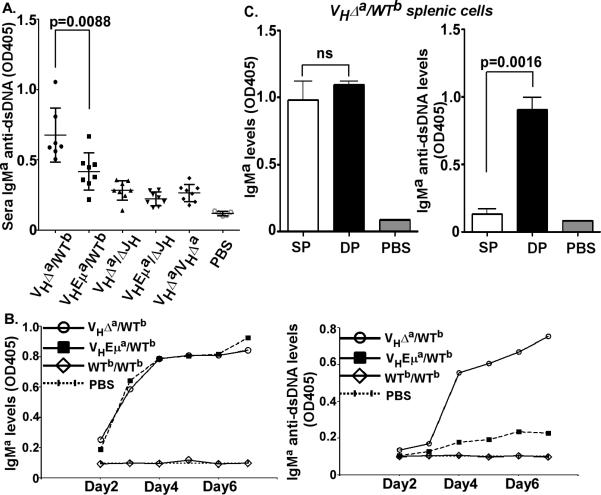

Allelically “included” B cells (expressing 2 different receptors) bear a higher probability of auto-reactivity

A relationship between the expression of two different BCRs and autoreactivity has long been postulated as an evolutionary explanation for the development of “allelic exclusion” in B lymphocytes. Having developed a mouse strain with a profound defect in allelic exclusion, we asked whether the double-producers from these animals were at increased risk of expressing autoreactive receptors. In a preliminary ANA (anti-nuclear antibody) screen for autoimmune antibodies, 8/13 (61%) sera from VHΔa/WTb animals showed moderate to high reactivity to nuclei, while 3/20 (15%) sera from VHEμa/WTb animals showed comparable reactivity (data not shown).

To extend these analyses, we examined sera from mice of these and additional genotypes for anti-dsDNA reactivity by ELISA. Included in these analyses were two mouse strains that carried the VHΔa allele but were unable to generate double-producers, either because they were homozygous for the VHΔa allele (VHΔa/VHΔa) or because they lacked a functional second allele (VHΔa/ΔJH). To directly compare IgM generated from the B1-8VH knock-in allele (present in all genotypes, with or without Eμ), we used anti-Igμa antibody to detect anti-dsDNA antibodies in mouse sera. As shown in Fig. 8A, IgMa in sera from VHΔa/WTb animals contained significantly more anti-dsDNA reactivity than did IgMa from any of the other genotypes (VHEμa/WTb, VHΔa/VHΔa, VHΔa/ΔJH or VHEμa/ΔJH).

Figure 8. Auto-reactivity of B cells expressing 2 different receptors.

A. IgMa (B1-8VH) anti-dsDNA proteins in sera from mice of the indicated genotypes. Y-axis = (OD405 of IgMa anti-dsDNA)/(OD405 of total IgMa) in sera. This ratio of the standard IgMa anti-dsDNA monoclonal antibody is set at 1.0 and not shown in figure. Means and standard deviations are shown as horizontal lines with vertical brackets. Dots correspond to sera from individual animals analyzed at 5-6 months of age. PBS used as negative controls.

B. IgMa (B1-8VH) anti-dsDNA in supernatants of LPS-stimulated cultures, and harvested at the indicated times. Both total IgMa (left panel) and IgMa anti-dsDNA (right panel) in splenic B cell cultures were compared, from VHΔa/WTb, VHEμa/WTb and WTb/WTb mice. PBS used as negative controls. Data shown is representative of 3 individual experiments.

C. IgMa anti-dsDNA antibody secretion by double-producers. VHΔa single-producers (SP, IgMa+b−) and VHΔa/WTb double-producers (DP, IgMa+b+) from spleens of VHΔa/WTb mice were sorted, cultured in LPS and culture supernatants harvested at day 7. Total IgMa produced by SP and DP (left panel); IgMa anti-dsDNA produced by SP and DP (right panel).PBS used as negative controls. Bar graph is a statistical analysis of 3 individual experiments. p-values were calculated by two-tailed student t test (ns= non-significant).

To look more directly for anti-dsDNA BCRs among splenic B cell double-producers, we cultured B220+ spleen cells from VHΔa/WTb mice (~20% double-producers) and VHEμa/WTb mice (no double-producers) with LPS for 7 days. The two cultures produced comparable amounts of IgMa, rising well above background by Day 3 (Fig. 8B, left panel). Culture supernatants from the VHΔa/WTb culture, however, showed a striking rise in IgMa antibodies reactive to dsDNA over time, while this did not occur in the VHEμa/WTb cultures (Fig. 8B, right panel).

To ask whether this IgMa anti-dsDNA antibody (expressed from the VHΔa IgH gene) was being produced by the single-producers and/or by the double-producers from VHΔa/WTb animals, we sorted splenic B cells into these two subpopulations and cultured them separately with LPS. Culture supernatants were analyzed on day 7 for anti-dsDNA antibody. As shown in Fig. 8C, left panel, again, IgMa secretion overall was the same in both cultures. However, only the double-producers secreted IgMa anti-dsDNA antibody (Fig. 8C, right panel). These data suggest that autoreactive BCRs are more prevalent on the double-producers of VHΔa/WTb mice than on single-producers in the same mice or in VHEμa/WTb mice. As discussed below, we interpret this as evidence that the BCRs formed with Igμa from the Eμ-deficient IgH allele are not only of insufficient density to signal positive selection but also are unable to signal negative selection.

As we have previously shown, VHEμa/WTb and VHΔa/WTb mice differ profoundly with respect to allelic exclusion (28). The immature and splenic double-producers, characteristic of VHΔa/WTb mice, are absent in VHEμa/WTb mice. There are, however, some double-producers in VHEμa/WTb mice, and these are restricted to the peritoneal cavity of these mice (28). As a consequence of these cells, IgMb is present in the sera of VHEμa/WTb mice at about the same level as in VHΔa/WTb mice. We used this as a means for asking whether the absence of Eμ (and the resulting lower BCR density) was responsible for the increased frequency of anti-dsDNA antibodies, or, alternatively, any BCR on double-producers (even that encoded by an allele with Eμ) would have a greater likelihood of autoreactivity. We found no difference in serum IgMb anti-dsDNA level in VHEμa/WTb versusVHΔa/WTb versus C57BL/6 mice (WTb/WTb) (data not shown), demonstrating no alteration in the selection of BCRs containing Igμ from the WTb allele. It was only BCRs comprised of Igμa from the Eμ-deficient allele, therefore, that showed evidence of deficient negative selection in double-producers.

DISCUSSION

In both mice and humans, the pre-B to immature B cell transition is an important checkpoint at which emerging BCRs are tested for functionality and autoreactivity (12, 61, 62). Cells expressing anti-self receptors undergo either receptor editing or clonal deletion (37, 63-66), whereas those expressing non-autoreactive receptors continue to differentiate (12, 17). In the present study, we provide evidence that nascent BCRs must reach a signaling threshold in order for cells to be positively selected into the immature B cell pool and that the BCR's ability to reach this threshold is a function of both receptor structure (VH+VL combination) and abundance. The role of the Igh intronic enhancer, Eμ, at this transition, therefore, is to assure high enough abundance (through sufficiently high expression of the IgH gene), so that most IgH/IgL combinations achieve the signaling threshold for positive selection.

In the absence of Eμ, pre-B cells expressed Igμ at half the normal level, and this correlated with a discernible decrease in the active (tyrosine-phosphorylated) forms of signaling molecules acting downstream of the pre-BCR/BCR. We conclude that the low Igμ levels translate into low BCR (and pre-BCR) levels that, in turn, lead to tonic signals of reduced average signal strength. If there were a signaling threshold for positive selection into the immature B cell compartment, then an overall reduced average signal from emerging BCRs should compromise this transition because only the most potent BCRs (VH+VL structure) would surmount this threshold. Consistent with that hypothesis, we found the immature B cell compartment in Eμ-deficient mice was half the size of that in a genetically matched mouse strain where pre-B cells produced twice the amount of Igμ.

These findings extend and refine an earlier study which showed that BCR signals are critical to maintaining immature B cells at the immature B cell stage. In that study, an IgH gene (and, therefore, BCR) was removed from immature B cells by inducible deletion, and the result was “back-differentiation” to the pre-B cell stage with concomitant re-initiation of light chain gene rearrangements (23). The current study further demonstrates that not only BCR ablation, but also reduced BCR signals, result in defective transitioning, revealing a signaling threshold for generating an immature B cell.

While others have described the effects of perturbing Igμ levels and/or BCR signals in genetically-modified mice (e.g.(23, 25, 54, 67-69)), a unique feature of the present experimental system is that Igμ expression is not irreversibly depressed throughout B cell development. In VHΔa mice, Igμ expression returns to wild-type levels in immature B cells and their descendants ((28) and Fig. 5). We, and others, have also shown that IgH transcription remains independent of Eμ in Ig-secreting cells (70-73). This is explained by the presence of a second transcriptional control region within the Igh locus that lies downstream of the heavy chain constant region gene (CH) cluster (3’ regulatory region = 3’RR) (59, 74, 75). The 3’RR becomes active as soon as surface Ig-positive (immature) B cells emerge (57-59), and its deletion in Ig-secreting cells leads to a dramatic decrease in Ig transcription (76-78). Taking these observations together with those of the current study, it can be concluded that when cells reach the immature B cell stage, Eμ's role in Igμ gene transcription is supplanted by the 3’RR. The return to wild-type Igμ levels in immature B cells of VHΔa mice correlates with a return to normal BCR-signaling (as measured by levels of the active forms of Syk and Erk kinases) and resumption of normal development to later B cell stages (Fig. 3, 4, 5), allowing us to identify the specific stage at which Eμ's functions (and its effects on Igμ expression) are critical. Another advantage of this experimental system is that we can directly attribute effects to Igμ mRNA and protein level, without the confounding effects of differences in nucleic acid/amino acid sequence, since all comparisons among cell stages in VHΔa mice and between VHEμa and VHΔa mice are of cells expressing the same IgH gene with identical VH and IgH promoter.

Absence of Eμ affects not only emerging B cell numbers, but also the emerging antibody repertoire. The resulting decrease in Igμ results in continued light chain rearrangements and “editing” in search of an IgH/IgL combination with better signaling properties (current study and (28)). Evidence that IgL structure (V region sequence) influences development in cells expressing low Igμ comes from our study of mice carrying both the Eμ-deficient IgH allele and a 3-83κ knock-in allele. We chose the 3-83κ knock-in gene since the 3-83κ light chain had already been shown to combine with B1-8H-chain to form a functional BCR that supports B cell development(37). We didn't know, however, whether this combination would be able to circumvent the defect caused by low Igμ levels (VHΔa allele). As shown in Fig. 7, addition of the 3-83κ knock-in allele increased the size of the immature B cell compartment of VHΔa/WTb mice so that the ratio of (pro-B+pre-B)/immature B cell was reduced from an average of 7 to less than 1. Had this BCR (B1-8H/3-83κ) been one of those with lower-than-threshold signaling properties, we might have found an even more pronounced stall at the pre-B to immature B cell transition. This is not what we found, however, and so the relative decrease in size of the (pro-B+pre-B) cell compartment and increase of the immature B cell compartment was unremarkable as this is found in all H+L knock-in mice (as long as the BCR is not autoreactive) (e.g. (37)). What was remarkable was the effect on heavy-chain allelic exclusion: double-producers were significantly reduced in number both among immature B cells and splenic B cells. The fact that Ig light chain sequence could affect IgH allelic exclusion is consistent with our hypothesis that double-producers are at a selective advantage at the pre-B to immature B cell transition in VHΔa/WTb mice only because of the signaling defect caused by low Igμ levels in single-producers.

Interestingly, we have found that processes preceding the pre-B to immature B cell transition are much less dependent upon Igμ levels than is the development and selection of immature B cells. We have previously shown that the first “check-point” in allelic exclusion (feedback inhibition of DNA rearrangement on a second allele), while mediated by membrane Igμ and the signaling molecules Igα and Igβ (31, 32, 68, 69, 79), is fully operational in B1-8VH knock-in animals and is unaffected by Eμ deletion (28). The pre-BCR (composed of nascent Igμ chain, SLC, and Igα and Igβ) induces differentiation to the pre-B cell stage, proliferative expansion of large pre-B cells, subsequent down-regulation of SLC expression, and the onset of IgL gene assembly (6, 10, 56, 80-82). Pro- to pre-B cell differentiation appeared normal in the absence of Eμ. In our experimental system, all cells carry a productively rearranged B1-8VH, and, as a result, they should largely bypass the pro-B cell stage and proceed directly to the pre-B cell stages. This proved true for both VHΔa/WTb and VHEμa/WTb mice, with no discernible difference in the size of their pro-B cell compartments (reduced relative to wild-type) (Supplemental Figure 2A, 2B and data not shown). We found equivalent numbers of pre-B cells in the VHΔa/WTb versus VHEμa/WTb mice, as well, suggesting that proliferative expansion and differentiation were also taking place normally in the absence of Eμ. A caveat to this interpretation is that deficient pre-B cell expansion might be masked by these cells’ inefficient, BCR-mediated exit into the immature B cell compartment. Otherwise, pre-B cell numbers might have been expected to rise because of this inefficient exit. Alternatively, pre-BCR-mediated proliferation may be normal, and, instead, apoptosis of BCR signal-deficient cells balances the slow exit. In any case, re-expression of RAG-1 and RAG-2 genes and Igκ locus germ line transcription (preludes to Igκ gene assembly) (10, 82), both being processes mediated by pre-BCR signals, occurred at equivalent levels whether Eμ was present or absent on the expressed Igμ allele (Fig. 6). Taken together, these findings support the conclusion that the signaling threshold for pre-BCR-mediated processes is lower than that of BCR-mediated ones. As a result, pre-BCR signaled events are not affected by the absence of Eμ as long as a functional VH gene (such as B1-8VH) has already been assembled. Rather, after VH gene assembly, Eμ's importance is next manifested at the pre-B to immature B cell transition where BCR (not pre-BCR) signaling is required and tested.

Finally, as we have pointed out, it has long been conjectured that allelic exclusion arose as a means for ensuring that each B cell is separately selected for expansion or for elimination, depending on the specificity of the BCR it displays (83). If B cells were permitted to display more than one receptor, then antigen-induced expansion could result in simultaneous production of a protective (antigen-reactive) antibody and an autoreactive (passenger) one. In support of this notion, several studies have identified expression of either two IgH alleles or two IgL alleles in mouse and human B cells with autoreactive specificity (84-93). In several Ig transgenic or Ig “knock-in” mice, it has been shown that when self-reactive receptors are co-expressed with non–self-reactive ones, the affected B cells escape negative selection and develop into mature, B lymphocytes. Explanations for this “escape” include: 1) the receptor with high avidity to self-antigen is concealed in the cytoplasm so that only when the BCR with innocuous specificity is stimulated is the second, autoreactive antibody revealed through secretion from resulting plasma cells (88, 92) and 2) co-expression of two Igκ alleles or of Igκ and Igλ chains results in competition for assembly with the one available Ig heavy chain, diluting the surface density of both BCRs and thereby making neither sufficiently “visible” for negative selection (85, 86, 91, 92). While all of these studies would suggest that allelic “inclusion” (double-producers) constitutes a risk-factor for autoimmunity, several studies have shown that double-producers are not, a priori, autoreactive (94, 95). For example, when double-producers were specifically examined in a mouse model of autoimmunity (systemic lupus erythematosus, SLE), most were not autoreactive, and, reciprocally, B cells with DNA-specific BCRs were no more likely to be double-producers than were non-autoreactive B cells (94).

The double-producers found in high numbers in VHΔa/WTb mice (but not in VHEμa/WTb mice) provide yet another example of how such cells might contribute to the risk for autoimmunity. In this case, it is the difference in the expression level of Igμ from two different IgH alleles that we suggest explains their ability to transit, unchecked, from pre-B to immature B cells. As we have shown in mice dependent solely upon expression of the VHΔa allele, this Eμ-deficient allele drives expression of a BCR that is often insufficient to drive positive selection. We suggest that this makes it also impervious to negative selection. When the VHΔa allele is expressed together with the WTb allele that retains Eμ, it is the BCR with “wild-type” heavy chain that drives positive selection and is subject to negative selection. Given that a newly formed B cell receptor (IgH+IgL combination) is autoreactive at a frequency as high as 75% (62, 96), the B1-8 H chain (from the VHΔa allele) plus light chain in such double-producers may sometimes prove autoreactive, but it will be invisible to the negative selection process. Consistent with that hypothesis, we found that only in the VHΔa/WTb mice (not in VHEμa/WTb mice expressing the same B1-8 H chain), and only in double-producers from VHΔa/WTb mice, were there anti-dsDNA antibodies associated with the B1-8 H chain (Igμa; Fig. 8). It should be noted, however, that we have found no evidence of autoimmune disease in these animals up to 6 months of age (no proteinuria and normal “blood urea nitrogen” levels as compared to age-matched wild-type animals, data not shown). Assays for IgGa-anti-dsDNA antibodies were also negative, suggesting that the cells secreting IgMa-anti-dsDNA antibodies were not commonly undergoing class-switching (in germinal centers) and forming IgG-secreting plasmacytes. Nevertheless, the difference in the development of IgMa-anti-dsDNA antibodies in the matched mouse strains (VHΔa/WTb versus VHEμa/WTb) and in double- versus single-producers clearly shows that BCR selection is profoundly affected by the presence of a second BCR with alternative specificity. Presumably, if within an autoimmune mouse background, the double-producers of VHΔa/WTb mice would increase the likelihood of autoimmune disorders.

In summary, loss of the intronic enhancer, Eμ, from a productive IgH allele has profound effects on B cell development and Ig repertoire. This results from a reduction in Igμ levels at the critical transition from pre-B to immature B cell. There are other means by which Igμ levels could be modified at this stage (e.g. unusually weak VH promoters, genetic polymorphisms in enhancer sequence and strength, polymorphisms in transcription factors required for enhancer or promoter function), suggesting a mechanism by which individuals may be predisposed to more restricted versus broader Ig repertoires and/or to autoimmunity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Klaus Rajewsky (CBR Institute, Harvard Medical School) for providing the B1-8VH vector, and Dr. Roberta Pelanda (National Jewish Center for Immunology) for providing the 3-83κ mice.

We are grateful to Dr. Betty Diamond (Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System) for assisting with auto-reactivity studies, Dr. Linda Spatz (Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education, City College, CUNY) for supplying materials and instruction with regard to the anti-dsDNA ELISAs, and Dr. Christopher Roman (State University of New York, Downstate Medical Center) for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

We also thank Mr. Joon Kim of the Flow Cytometry Facility at Hunter College (CUNY) for help with cell sorting, and the staff of the Animal Facility at Hunter College (CUNY) for maintaining our mouse colony.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- BM

bone marrow

- pre-BCR

pre-B cell receptor

- SLC

surrogate light chain

- sIgM

surface IgM

- VH region

heavy chain variable region

- WT

wild-type

- 3’RR

3’ regulatory region of Igh locus

Footnotes

This project was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01-AI030653 to LAE. The infrastructure and instrumentation were supported in part by an NIH Research Centers in Minority Institutions (RCMI) award (RR-003037) to Hunter College (CUNY).Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR or NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Osmond DG, Rolink A, Melchers F. Murine B lymphopoiesis: towards a unified model. Immunology Today. 1998;19:65–68. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy RR, Hayakawa K. B CELL DEVELOPMENT PATHWAYS. Annual Review of Immunology. 2001;19:595–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagata K, Nakamura T, Kitamura F, Kuramochi S, Taki S, Campbell KS, Karasuyama H. The Ig alpha/Igbeta heterodimer on mu-negative proB cells is competent for transducing signals to induce early B cell differentiation. Immunity. 1997;7:559–570. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80377-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karasuyama H, Kudo A, Melchers F. The proteins encoded by the VpreB and lambda 5 pre-B cell-specific genes can associate with each other and with mu heavy chain. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1990;172:969–972. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.3.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuentes-Panana EM, Bannish G, Shah N, Monroe JG. Basal Igalpha/Igbeta signals trigger the coordinated initiation of pre-B cell antigen receptor-dependent processes. Journal of immunology. 2004;173:1000–1011. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martensson IL, Keenan RA, Licence S. The pre-B-cell receptor. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zou X, Piper TA, Smith JA, Allen ND, Xian J, Brüggemann M. Block in Development at the Pre-B-II to Immature B Cell Stage in Mice Without Igκ and Igλ Light Chain. The Journal of Immunology. 2003;170:1354–1361. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meffre E, Casellas R, Nussenzweig MC. Antibody regulation of B cell development. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:379–385. doi: 10.1038/80816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang LD, Clark MR. B-cell antigen-receptor signalling in lymphocyte development. Immunology. 2003;110:411–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2003.01756.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geier JK, Schlissel MS. Pre-BCR signals and the control of Ig gene rearrangements. Seminars in immunology. 2006;18:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.HASLER P, ZOUALI M. B cell receptor signaling and autoimmunity. The FASEB Journal. 2001;15:2085–2098. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0860rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurosaki T, Shinohara H, Baba Y. B Cell Signaling and Fate Decision. Annual Review of Immunology. 2010;28:21–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niiro H, Clark EA. Regulation of B-cell fate by antigen-receptor signals. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:945–956. doi: 10.1038/nri955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsueh RC, Scheuermann RH. Tyrosine kinase activation in the decision between growth, differentiation, and death responses initiated from the B cell antigen receptor. Advances in immunology. 2000;75:283–316. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(00)75007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grimaldi CM, Hicks R, Diamond B. B Cell Selection and Susceptibility to Autoimmunity. The Journal of Immunology. 2005;174:1775–1781. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Boehmer H, Melchers F. Checkpoints in lymphocyte development and autoimmune disease. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:14–20. doi: 10.1038/ni.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bannish G, Fuentes-Panana EM, Cambier JC, Pear WS, Monroe JG. Ligand-independent signaling functions for the B lymphocyte antigen receptor and their role in positive selection during B lymphopoiesis. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1583–1596. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.11.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuentes-Panana EM, Bannish G, Monroe JG. Basal B-cell receptor signaling in B lymphocytes: mechanisms of regulation and role in positive selection, differentiation, and peripheral survival. Immunological reviews. 2004;197:26–40. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monroe JG. ITAM-mediated tonic signalling through pre-BCR and BCR complexes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:283–294. doi: 10.1038/nri1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanchez P, Crain-Denoyelle AM, Daras P, Gendron MC, Kanellopoulos-Langevin C. The level of expression of mu heavy chain modifies the composition of peripheral B cell subpopulations. Int Immunol. 2000;12:1459–1466. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.10.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heltemes LM, Manser T. Level of B cell antigen receptor surface expression influences both positive and negative selection of B cells during primary development. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 2002;169:1283–1292. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casola S, Otipoby KL, Alimzhanov M, Humme S, Uyttersprot N, Kutok JL, Carroll MC, Rajewsky K. B cell receptor signal strength determines B cell fate. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:317–327. doi: 10.1038/ni1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tze LE, Schram BR, Lam KP, Hogquist KA, Hippen KL, Liu J, Shinton SA, Otipoby KL, Rodine PR, Vegoe AL, Kraus M, Hardy RR, Schlissel MS, Rajewsky K, Behrens TW. Basal immunoglobulin signaling actively maintains developmental stage in immature B cells. PLoS biology. 2005;3:e82. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xing Y, Li W, Lin Y, Fu M, Li CX, Zhang P, Liang L, Wang G, Gao TW, Han H, Liu YF. The influence of BCR density on the differentiation of natural poly-reactive B cells begins at an early stage of B cell development. Molecular immunology. 2009;46:1120–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rowland SL, DePersis CL, Torres RM, Pelanda R. Ras activation of Erk restores impaired tonic BCR signaling and rescues immature B cell differentiation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207:607–621. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Afshar R, Pierce S, Bolland D, Corcoran A, Oltz EM. Regulation of IgH gene assembly: role of the intronic enhancer and 5'DQ52 region in targeting DHJH recombination. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 2006;176:2439–2447. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perlot T, Alt FW. Chapter 1 Cis-Regulatory Elements and Epigenetic Changes Control Genomic Rearrangements of the IgH Locus. In: Frederick WA, editor. Advances in immunology. Academic Press; 2008. pp. 1–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li F, Eckhardt LA. A role for the IgH intronic enhancer E mu in enforcing allelic exclusion. J Exp Med. 2009;206:153–167. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li F, Yan Y, Pieretti J, Feldman DA, Eckhardt LA. Comparison of identical and functional Igh alleles reveals a nonessential role for Emu in somatic hypermutation and class-switch recombination. Journal of immunology. 2010;185:6049–6057. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luning Prak ET, Monestier M, Eisenberg RA. B cell receptor editing in tolerance and autoimmunity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1217:96–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05877.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brady BL, Steinel NC, Bassing CH. Antigen receptor allelic exclusion: an update and reappraisal. Journal of immunology. 2010;185:3801–3808. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vettermann C, Schlissel MS. Allelic exclusion of immunoglobulin genes: models and mechanisms. Immunological reviews. 2010;237:22–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burnet FM. A modification of Jerne's theory of antibody production using the concept of clonal selection. Aust. J. Sci. 1957;20:67–68. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.26.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sonoda E, Pewzner-Jung Y, Schwers S, Taki S, Jung S, Eilat D, Rajewsky K. B cell development under the condition of allelic inclusion. Immunity. 1997;6:225–233. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gu H, Zou Y-R, Rajewsky K. Independent control of immunoglobulin switch recombination at individual switch regions evidenced through Cre-loxP-mediated gene targeting. Cell. 1993;73:1155–1164. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90644-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mombaerts P, Iacomini J, Johnson RS, Herrup K, Tonegawa S, Papaioannou VE. RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell. 1992;68:869–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90030-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pelanda R, Schwers S, Sonoda E, Torres RM, Nemazee D, Rajewsky K. Receptor Editing in a Transgenic Mouse Model: Site, Efficiency, and Role in B Cell Tolerance and Antibody Diversification. Immunity. 1997;7:765–775. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pelanda R, Schaal S, Torres RM, Rajewsky K. A prematurely expressed Igkappa transgene, but not a VkappaJkappa gene segment targeted into the Igkappa locus, can rescue B cell development in lambda5-deficient mice. Immunity. 1996;5:229–239. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80318-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sato H, Saito-Ohara F, Inazawa J, Kudo A. Pax-5 Is Essential for κ Sterile Transcription during Igκ Chain Gene Rearrangement. The Journal of Immunology. 2004;172:4858–4865. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chu Y-P, Taylor D, Yan H-G, Diamond B, Spatz L. Persistence of partially functional double-stranded (ds) DNA binding B cells in mice transgenic for the IgM heavy chain of an anti-dsDNA antibody. International Immunology. 2002;14:45–54. doi: 10.1093/intimm/14.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]