Abstract

In eukaryotes, chromosomes are encased by a dynamic nuclear envelope. In contrast to metazoans, where the nuclear envelope disassembles during mitosis, many fungi including budding yeast undergo “closed mitosis,” where the nuclear envelope remains intact throughout the cell cycle. Consequently, during closed mitosis the nuclear envelope must expand to accommodate chromosome segregation to the two daughter cells. A recent study by Witkin et al. in budding yeast showed that if progression through mitosis is delayed, for example due to checkpoint activation, the nuclear envelope continues to expand despite the block to chromosome segregation. Moreover, this expansion occurs at a specific region of the nuclear envelope- adjacent to the nucleolus- forming an extension referred to as a “flare.” These observations raise questions regarding the regulation of nuclear envelope expansion both in budding yeast and in higher eukaryotes, the mechanisms confining mitotic nuclear envelope expansion to a particular region and the possible consequences of failing to regulate nuclear envelope expansion during the cell cycle.

Keywords: nuclear envelope, mitosis, nuclear membrane, checkpoint, nucleolus, nuclear envelope breakdown, nuclear morphology

The Nuclear Envelope during Mitosis: Anything but Static

In order to proliferate, cells must accurately transmit their chromosomes from one generation to the next. In eukaryotes, the chromosomes are confined to the nucleus, the perimeter of which is defined by the nuclear envelope. The nuclear envelope is made of a double membrane; the outer nuclear membrane is continuous with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and contains many of the same proteins. The inner nuclear membrane contains a distinct set of proteins, some of which interact with chromatin. The outer and inner nuclear membranes are fused at sites of nuclear pore complexes (NPCs), macromolecular structures that allow selective passage of proteins, RNA and other molecules to and from the nucleus.1 In most eukaryotes, underlying the inner nuclear membrane is a network of proteins, called the nuclear lamina, made of lamins and lamin-associated proteins. This network provides rigidity to the nucleus and contributes to chromatin organization and other nuclear processes. Interestingly, neither plants nor fungi have a lamin-based nuclear lamina, although other structures may serve a similar purpose. Of note, proper maintenance of nuclear morphology is linked to cellular function. In humans, alterations in nuclear shape and size are characteristic of aging and certain disease states, such as various types of cancer.2,3 Thus, understanding how nuclear shape is regulated and identifying genes that contribute to nuclear morphology are of interest from both a medical and a basic biology standpoint.

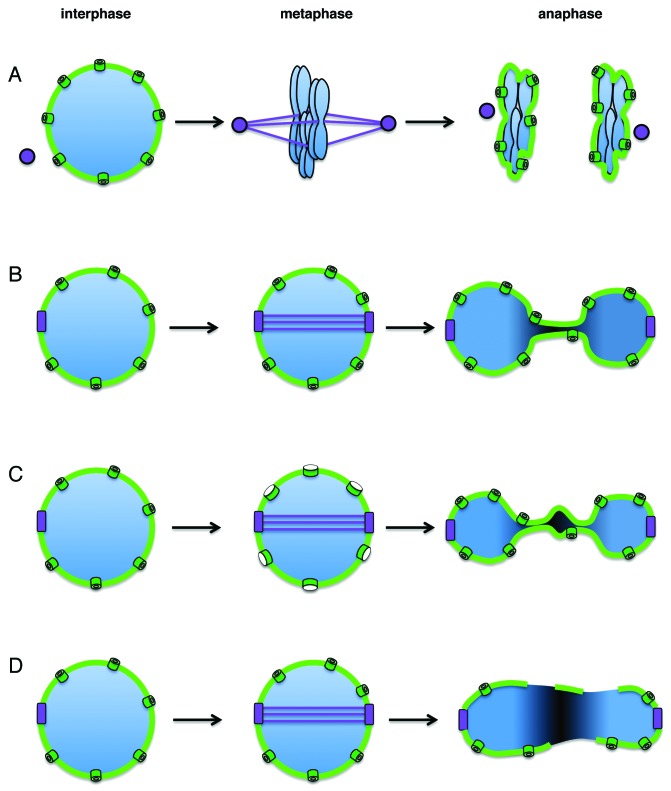

The nuclear envelope not only serves as a diffusion barrier but also as a physical barrier separating the chromosomes from cytoplasmic structures. In most animal cells these cytoplasmic structures include the centrosomes, which function as microtubule organizing centers that nucleate spindle microtubules necessary for chromosome segregation. However, just before mitosis, the nuclear envelope stands between these microtubules and the chromosomes. Different cell types have adopted different strategies to facilitate the access of chromosomes by microtubules: at one end of the spectrum are cells of most metazoans, in which nuclear envelope components, including the two nuclear membranes, the NPCs and the nuclear lamina with their associated proteins, disperse during each and every mitosis4 (Fig. 1A). This type of mitosis is called “open mitosis,” and it necessitates the reassembly of the nuclear envelope around a full complement of chromosomes in each of the daughter cells once chromosome segregation is completed. Parenthetically, the mechanism that ensures the formation of only a single nucleus at the end mitosis, as opposed to several nuclei each encompassing a subset of chromosomes, is not known. At the other end of the spectrum are certain fungi in which the centrosome equivalents, called spindle pole bodies, are either permanently embedded in the nuclear envelope (such as in budding yeast5) or are embedded in the nuclear envelope prior to mitosis (such as in fission yeast6). These cells undergo what is called “closed mitosis,” which occurs without nuclear envelope breakdown, as spindle microtubules that assemble within the nucleus can readily access the chromosomes. However, during closed mitosis, the nucleus must elongate in a manner that is coordinated with chromosome movement as chromosome segregation takes place (Fig. 1B). In most, but not all, cases, this process involves nuclear envelope expansion.

Figure 1. The nuclear envelope during different types of mitosis. (A) Open mitosis. During interphase, the chromatin (blue) is contained within the nuclear envelope (light green). As cells enter mitosis, the nuclear envelope disassembles, allowing spindle microtubules (purple lines) nucleated by centrosomes (purple spheres) to align the chromosomes on the metaphase plate. The nuclear envelope reforms in late anaphase, following chromosome segregation. (B) Closed mitosis. Shown is mitosis as it occurs in S. cerevisiae. The spindle pole body (purple) is embedded in the nuclear envelope throughout the cell cycle. After spindle pole body duplication, an intra-nuclear spindle is formed (S. cerevisiae chromosomes do not condense enough to visualize individual chromosomes or a metaphase plate). During anaphase, the nucleus elongates and the nuclear envelope expands as the sister chromatids move away from each other. (C) Functionally open, structurally closed mitosis. A term defined by Sazer10 to indicate a breakdown in the diffusion barrier while maintaining an intact nuclear envelope. Shown is mitosis as it occurs in Aspergillus nidulans. As in S. cerevisiae, during interphase the spindle pole body is embedded in the nuclear envelope. As cells enter mitosis the nuclear pores (dark green) partially disassemble, significantly reducing the diffusion barrier between the nucleus and cytoplasm. As in closed mitosis, the nucleus elongates to allow chromosome segregation. The bulge in the center of the elongated nucleus during anaphase contains the nucleolus, which is left behind during chromosome segregation.28 The nuclear pores and the nucleolus reassemble at the end of mitosis. (D) Nuclear envelope rupture. Schizosaccharomyces japonicus cells form an intra-nuclear spindle as in cells undergoing closed or partially open mitosis. However, during anaphase, the nuclear envelope ruptures as the nucleus elongates without nuclear envelope expansion.

The historic definition of open vs. closed mitosis was based on cytology: during open mitosis the nuclear envelope disappears, “opening” the nucleus and exposing its content to the cytoplasm, while in closed mitosis the nuclear envelope remains intact. From a functional standpoint, the presence or absence of a nuclear envelope affects at least two processes: the free diffusion of molecules between the cytoplasm and the nucleus (which occurs during open, but not closed, mitosis) and the presence of a physical barrier between the chromosomes and cytoplasmic structures (which exists in closed, but not open, mitosis). Over the years, mitotic divisions that fall somewhere in between open and closed have been described, warranting a brief discussion on how these forms of mitosis should be defined.

In Aspergillus nidulans, which was originally defined as undergoing closed mitosis, NPCs partially disassemble as cells enter mitosis, disrupting the diffusion barrier between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, while maintaining a physical barrier between the chromosomes and cytoplasmic structures7 (Fig. 1C). A breakdown in the diffusion barrier also occurs during a brief period in anaphase of meiosis II of the fission yeast Schisosaccharomyces pombe.8,9 Unlike the situation in A. nidulans, however, the change in permeability in S. pombe meiosis II occurs at only a short window of nuclear division and is not accompanied by changes in either NPC composition or nuclear membrane integrity. This led Sazer to define this type of division as “functionally open but structurally closed”10, a term that can also be applied to A. nidulans mitosis.

Other types of mitosis involve a partial opening in the nuclear membrane itself. In Schisosaccharomyces japonicas, the nuclear envelope does not expand during mitosis, nor does it disassemble. As a result, the nuclear envelope ruptures as the intra-nuclear spindle elongates11,12 (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, rupturing is not a result of forces exerted by the spindle, but rather a programed cell cycle event, the regulation and mechanism of which remain to be discovered.11 In the early embryonic divisions of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans the nuclear envelope is breached in pro-metaphase, allowing diffusion of cytoplasmic proteins into the nuclear space.13 A similar phenomenon is seen during Drosophila syncytial divisions, where the nuclear envelope displays a partial disassembly of nuclear pore complexes and fenestrations near the centrosomes, thereby allowing microtubules to access the chromosomes.14,15 Live cell imaging suggests that just as in closed mitosis, the nuclear envelope during Drosophila syncytial divisions expands as the spindle elongates. In these three cases, however, mitosis is not structurally closed, as nuclear envelope integrity is breached and cytoplasmic structures, such as microtubules, can enter the nucleus. Consequently, the term “functionally open but structurally closed” may not fully apply when describing these types of mitosis, and several studies have previously referred to these mitoses as “semi-open mitosis.” We propose to use “partially open mitosis” as term that encompasses all forms of mitosis that are neither fully closed nor fully open, but that exhibit a change in the diffusion barrier at some point during mitosis that may or may not be accompanied by visible structural change to the nuclear envelope.

Among unicellular eukaryotes there are many variations of nuclear envelope behavior during mitosis (for more examples see refs. 16 and 17), and undoubtedly additional forms of mitosis still remain to be discovered. It is likely that the various types of mitosis have evolved to adapt to a particular environment, although it is currently not known what kinds of selective pressure shaped the different modes of mitosis. A possible driving force is the position of the centrosome, namely in the cytoplasm vs. embedded in the nuclear envelope, which likely coevolved with nuclear envelope behavior. In addition, the evolution of mitosis could have been affected by the need to eliminate rate-limiting diffusion barriers between the nucleus and the cytoplasm as occurs during open and partially open mitosis, but is either not a problem or is somehow overcome in closed mitosis. It is conceivable that, during syncytial divisions, partially open mitosis evolved to overcome the diffusion barrier and microtubule accessibility problems, while protecting chromosomes from aberrant attachments to microtubules from neighboring nuclei. The evolution of different forms of mitosis remains an unresolved, yet fascinating, question.

Closed Mitosis: A Strategy that Generates a Complication

Closed mitosis appears at first glance to be an economical solution to the issue of microtubule-chromosome accessibility: nuclear envelope breakdown is circumvented, the chromosomes do not get “entangled” with cytoplasmic structures, and cells do not have to reassemble the nuclear envelope at the end of mitosis, risking leaving one or more chromosomes outside the nuclear perimeter. However, this mode of mitosis also raises several questions. Chief among them is how the nuclear envelope expands. In particular, how is the timing of nuclear expansion determined? Is it a consequence of spindle elongation or is it an independent process regulated by the cell cycle machinery? And how are nuclear envelope components added? Finally, what happens to nuclear envelope expansion if cells are delayed in mitosis, for example due to checkpoint activation?

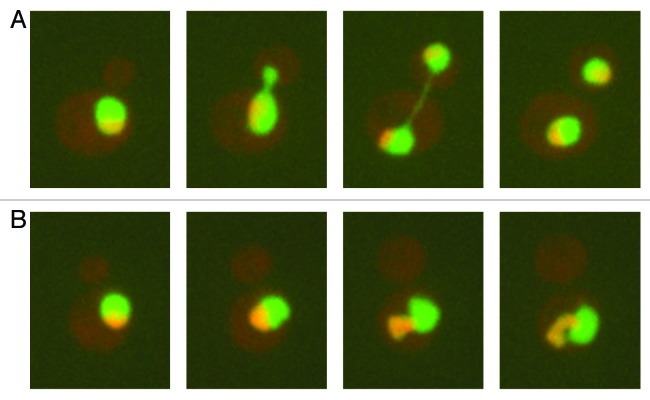

An insight into these questions came from a study by Witkin et al.18 on the shape of the budding yeast nucleus. During normal growth, the budding yeast nucleus is round, except during mitosis when it elongates through the bud neck to accommodate chromosome segregation (Fig. 2A). Witkin et al. screened for genes that when deleted lead to alterations in nuclear shape, aiming to identify genes that affect nuclear envelope dynamics. The authors used a collection of roughly 5000 budding yeast deletion mutants (each deleted for a single non-essential gene), into which they introduced a nuclear GFP marker and a cytoplasmic RFP marker. This strategy then allowed them to screen visually for mutants that displayed abnormal nuclear morphology. One class of nuclear abnormalities was of nuclei that exhibited extensions, referred to as “flares” (Fig. 2B). Further examination of these mutants revealed that this altered nuclear phenotype was not due to a direct involvement of the deleted genes in nuclear morphology, but rather due to the activation of a checkpoint pathway (e.g., the DNA damage checkpoint or the spindle assembly checkpoint) that induced a mitotic delay. In other words, the mutations isolated in the screen likely increased the formation of intracellular damage, which, in turn, led to a mitotic delay through checkpoint activation. Indeed, other conditions that induced a mitotic delay (e.g., depolymerizing microtubules with nocodazole; inhibiting the anaphase promoting complex) also led to the formation of a nuclear flare. Interestingly, the nuclear flare formed due to a mitotic delay was confined to the nuclear envelope region adjacent to the nucleolus (Fig. 2B, and see below), which normally forms a crescent-shaped structure at the nuclear periphery (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. The budding yeast nucleus throughout the cell cycle. Shown are images taken 20 min apart of budding yeast cells expressing a GFP-tagged nucleoplasmic marker (Pus1) and an RFP-tagged nucleolar marker (Nsr1). (A) Untreated cells. (B) Cells treated with nocodazole. See text for details.

Importantly, the change in nuclear morphology was specific to a cell cycle delay in mitosis; Witkin et al. found that nuclei of cells arrested in S phase or G2 were mostly round. Moreover, the formation of the nuclear flare in cells treated with nocodazole began at the same time as nuclear elongation in untreated cells and was dependent on phospholipid synthesis. However, phospholipid synthesis alone was not sufficient to induce flares, as G2 arrested cells accumulated just as much phospholipid as mitotic arrested cells. Taken together, these results suggest that nuclear expansion during closed mitosis of budding yeast is independent of spindle elongation, but rather occurs in response to a cell cycle cue that signals mitotic entry.

Regulation of Nuclear Envelope Expansion

The study by Witkin et al. raises several interesting questions. First, what regulates nuclear envelope expansion? As noted above, the process is independent of spindle elongation, much like nuclear envelope rupture in S. japonicus. Fission yeast also appear to expand their nuclear envelope independent of spindle microtubules.19 Thus, in these yeasts there are likely targets of the cell cycle machinery that affect nuclear envelope dynamics during mitosis. What might be the target in budding yeast? The synthesis of phospholipids, the main components of the nuclear membrane, is required for nuclear envelope expansion, as shown previously for both budding and fission yeast.11,20,21 Moreover, at least one enzyme that negatively regulates membrane expansion, Pah1, is regulated by Cdk1 phosphorylation (ref. 20 and see below). The observation that a nuclear flare forms when checkpoint pathways are activated suggests that phospholipid synthesis is not subjected to checkpoint regulation. However, phospholipid synthesis is unlikely to be the only cell cycle target required for nuclear expansion, because G2-arrested cells accumulate just as much phospholipid as mitotic-arrested cells, yet they don't form a flare (ref. 18; note, however, that it is currently not known whether nuclear envelope of G2 cells also expands, but without forming a flare). It is tempting to speculate that the cell cycle target may be a protein or a process that is responsible for allocating membrane addition specifically to the nuclear envelope, either by localized phospholipid synthesis or by drawing membrane from the ER preferentially during mitosis. Spindle elongation may also play a role in nuclear envelope expansion: although the surface area of the nucleus increases during a mitotic arrest in the absence of a spindle (i.e., during an arrest induced by nocodazole), it is possible that spindle elongation contributes to the rate, and perhaps magnitude, of nuclear envelope expansion.

The Expanding Mitotic Nuclear Envelope Uncovers Discrete Nuclear Envelope Domains

As noted above, Witkin et al. observed that nuclear envelope expansion during a mitotic arrest occurs in a curious fashion: rather than expanding isometrically, thereby generating a larger sphere, the flare occurs at the nuclear envelope that is adjacent to the nucleolus (Fig. 2B). Whether this occurs in other organisms that undergo closed mitosis is currently not known, as cell cycle analyses typically use DNA staining, rather than a nuclear envelope marker, to follow cell cycle progression. Nonetheless, the flare induced by a mitotic arrest is similar to the nuclear expansion observed when the Pah1 pathway is misregulated.22 Pah1 converts phosphatidic acid to diacylglycerol.23 In the absence of Pah1 (or in the absence of its activators, the Nem1 and Spo7 phosphatase complex) the overall levels of certain phospholipids increase, the ER loses its tubular shape in favor of membrane sheets, and the nucleus forms a flare at the nuclear envelope adjacent to the nucleolus. Why, then, in both Pah1 pathway mutants and in a mitotic arrest is the expansion of the nuclear envelope specific to the region adjacent to the nucleolus?

Campbell et al. showed that in a spo7∆ mutant, if the nucleolus is reduced to a tiny sphere the flare still forms, with the diminished nucleolus often at the base of the flare.22 Thus, nucleolar expansion is not driving flare formation. Whether the nucleolus, or its remnant, affects the adjacent nuclear envelope remains unknown. Alternatively, there may be a structure that prevents nuclear envelope expansion around the entire nuclear envelope except in the region adjacent to the nucleolus.24 There are indeed budding yeast nuclear membrane proteins that are excluded from the nucleolus; none of the ones tested had properties consistent with an inhibitor of membrane expansion (our lab, unpublished), but other such proteins may still exist.

As the nuclear envelope expands, where is the additional membrane coming from? Since the nuclear envelope is continuous with the ER, it is quite possible that phospholipids are synthesized at the nuclear envelope itself. If this were the case, it is conceivable that the nuclear envelope adjacent to the nucleolus would have a higher capacity for phospholipid synthesis, or that membrane is added throughout the nuclear envelope, but, as mentioned above, there may be a mechanism that resists expansion everywhere except adjacent to the nucleolus. Alternatively, the membrane could come from the ER, and if this were the case then the cell would have a mechanism for allocating membrane from the ER to the nuclear envelope specifically during mitosis. It is currently not known whether the ER expands during a mitotic arrest, and if so, at what rate. Thus, the mechanisms driving nuclear envelope dynamics, and in particular nuclear envelope expansion, remain to be uncovered.

Conclusions and Open Questions

The study by Witkin et al. highlights the dynamic nature of the nuclear envelope during the cell cycle. The observations in this study support a model whereby the nuclear envelope adjacent to the nucleolus is the preferential site of expansion during a mitotic delay. It is interesting that phospholipid synthesis is not under checkpoint control; consequently, a cell delayed in mitosis needs to somehow deal with increased nuclear envelope surface area in the absence of chromosome segregation. Why, under these conditions, doesn't the nuclear envelope expand isometrically? We can envision at least three possibilities: first, sequestering the added nuclear envelope to the region adjacent to the nucleolus could preserve inter-chromosomal interactions that would otherwise be disrupted were the nucleus to expand isometrically. Second, yeast cells are known to maintain a constant nuclear to cell volume ratio by a yet unknown mechanism.25,26 It is possible that by confining the extra nuclear envelope to a flare, rather than distributing it throughout the entire nuclear surface, the cell is better able to regulate its nuclear volume. Finally, the nuclear envelope adjacent to the nucleolus may be the region of initial nuclear envelope expansion even under normal growth conditions, but in the absence of spindle elongation this expansion is not distributed throughout the entire nuclear surface. Regardless of the mechanism, the appearance of a nuclear flare suggests that the budding yeast nuclear envelope has domains of distinct properties. How these domains differ in their ability to expand is not known. Isolation of mutants that fail to produce a flare during a mitotic arrest will likely shed light on the mechanism that designates distinct nuclear envelope domains and on the function of flare formation.

Finally, can observations in closed mitosis illuminate processes related to the nuclear envelope in cells that undergo open mitosis? As in closed mitosis, the nuclear envelope of metazoans must also expand, not during mitosis but during interphase, immediately following nuclear envelope reassembly.4 Much like in yeast, the source of membrane, and both the temporal and spatial regulation of this process, are unknown. Moreover, in certain cancer cells nuclei become larger and multi-lobed, and during aging the nuclear envelope appears “wrinkled”2,27; could this be a reflection of misregulated nuclear envelope expansion? And if so, do changes in the nuclear envelope have consequences for cell function? Despite the different modes of mitosis in budding yeast and mammalian cells, cell cycle processes have often proved to be based on conserved proteins. Thus, studies on nuclear envelope dynamics in budding yeast will likely shed light on processes related to nuclear envelope formation, tumorigenesis and aging in higher eukaryotes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca Meseroll, John Hanover and Fred Chang for stimulating discussion and comments on the manuscript. The authors were supported by an intramural grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Submitted

05/01/2013

Revised

06/03/2013

Accepted

06/10/2013

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/nucleus/article/25341

References

- 1.Hoelz A, Debler EW, Blobel G. The structure of the nuclear pore complex. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:613–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060109-151030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scaffidi P, Misteli T. Lamin A-dependent nuclear defects in human aging. Science. 2006;312:1059–63. doi: 10.1126/science.1127168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Méndez-López I, Worman HJ. Inner nuclear membrane proteins: impact on human disease. Chromosoma. 2012;121:153–67. doi: 10.1007/s00412-012-0360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kutay U, Hetzer MW. Reorganization of the nuclear envelope during open mitosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:669–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaspersen SL, Winey M. The budding yeast spindle pole body: structure, duplication, and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.022003.114106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding R, West RR, Morphew DM, Oakley BR, McIntosh JR. The spindle pole body of Schizosaccharomyces pombe enters and leaves the nuclear envelope as the cell cycle proceeds. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1461–79. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.8.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Souza CP, Osmani AH, Hashmi SB, Osmani SA. Partial nuclear pore complex disassembly during closed mitosis in Aspergillus nidulans. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1973–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asakawa H, Kojidani T, Mori C, Osakada H, Sato M, Ding DQ, et al. Virtual breakdown of the nuclear envelope in fission yeast meiosis. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1919–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arai K, Sato M, Tanaka K, Yamamoto M. Nuclear compartmentalization is abolished during fission yeast meiosis. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1913–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sazer S. Nuclear membrane: nuclear envelope PORosity in fission yeast meiosis. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R923–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yam C, He Y, Zhang D, Chiam KH, Oliferenko S. Divergent strategies for controlling the nuclear membrane satisfy geometric constraints during nuclear division. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1314–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aoki K, Hayashi H, Furuya K, Sato M, Takagi T, Osumi M, et al. Breakage of the nuclear envelope by an extending mitotic nucleus occurs during anaphase in Schizosaccharomyces japonicus. Genes Cells. 2011;16:911–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2011.01540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayashi H, Kimura K, Kimura A. Localized accumulation of tubulin during semi-open mitosis in the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:1688–99. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-09-0815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stafstrom JP, Staehelin LA. Dynamics of the nuclear envelope and of nuclear pore complexes during mitosis in the Drosophila embryo. Eur J Cell Biol. 1984;34:179–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiseleva E, Rutherford S, Cotter LM, Allen TD, Goldberg MW. Steps of nuclear pore complex disassembly and reassembly during mitosis in early Drosophila embryos. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3607–18. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.20.3607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heath IB. Variant mitoses in lower eukaryotes: indicators of the evolution of mitosis. Int Rev Cytol. 1980;64:1–80. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)60235-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drechsler H, McAinsh AD. Exotic mitotic mechanisms. Open Biol. 2012;2:120140. doi: 10.1098/rsob.120140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Witkin KL, Chong Y, Shao S, Webster MT, Lahiri S, Walters AD, et al. The budding yeast nuclear envelope adjacent to the nucleolus serves as a membrane sink during mitotic delay. Curr Biol. 2012;22:1128–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castagnetti S, Oliferenko S, Nurse P. Fission yeast cells undergo nuclear division in the absence of spindle microtubules. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos-Rosa H, Leung J, Grimsey N, Peak-Chew S, Siniossoglou S. The yeast lipin Smp2 couples phospholipid biosynthesis to nuclear membrane growth. EMBO J. 2005;24:1931–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saitoh S, Takahashi K, Nabeshima K, Yamashita Y, Nakaseko Y, Hirata A, et al. Aberrant mitosis in fission yeast mutants defective in fatty acid synthetase and acetyl CoA carboxylase. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:949–61. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell JL, Lorenz A, Witkin KL, Hays T, Loidl J, Cohen-Fix O. Yeast nuclear envelope subdomains with distinct abilities to resist membrane expansion. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1768–78. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pascual F, Carman GM. Phosphatidate phosphatase, a key regulator of lipid homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1831:514–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webster MT, McCaffery JM, Cohen-Fix O. Vesicle trafficking maintains nuclear shape in Saccharomyces cerevisiae during membrane proliferation. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:1079–88. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jorgensen P, Edgington NP, Schneider BL, Rupes I, Tyers M, Futcher B. The size of the nucleus increases as yeast cells grow. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3523–32. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-10-0973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neumann FR, Nurse P. Nuclear size control in fission yeast. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:593–600. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chow KH, Factor RE, Ullman KS. The nuclear envelope environment and its cancer connections. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:196–209. doi: 10.1038/nrc3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ukil L, De Souza CP, Liu HL, Osmani SA. Nucleolar separation from chromosomes during Aspergillus nidulans mitosis can occur without spindle forces. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2132–45. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]