Abstract

Emerin, a conserved LEM-domain protein, is among the few nuclear membrane proteins for which extensive basic knowledge—biochemistry, partners, functions, localizations, posttranslational regulation, roles in development and links to human disease—is available. This review summarizes emerin and its emerging roles in nuclear “lamina” structure, chromatin tethering, gene regulation, mitosis, nuclear assembly, development, signaling and mechano-transduction. We also highlight many open questions, exploration of which will be critical to understand how this intriguing nuclear membrane protein and its “family” influence the genome.

Keywords: emerin, Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, GAGE cancer-testis antigen, laminopathy, LEM-domain, nuclear envelope, nucleoskeleton, O-GlcNAc transferase, barrier-to-autointegration factor, Nestor-Guillermo progeria

Emerin: One Charted “Island” in the Unexplored Archipelago of Nuclear Membrane Proteins

The nuclear envelope (NE) comprises two membranes (inner and outer) with embedded nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) and underlying networks of nuclear intermediate filaments formed by A-type and B-type lamins.1,2 The NE membrane proteome is large and diverse, and includes both ubiquitous and potentially cell type-specific (“unique”) proteins. Nearly 200 unique NE transmembrane (“NET”) proteins were identified in proteomic studies of three cell types: rat liver (67 proteins),3 rat skeletal muscle (29 proteins)4 and human leukocytes (87 proteins).5 Among leukocyte NETs, 27% were unique to either resting or activated leukocytes.5 Different subsets of NETs contribute to spatial control of the genome,6 cell cycle regulation,7 or cytoskeletal organization,4 through unknown mechanisms. The functions of most NE membrane proteins are unexplored. The exceptions include NE membrane proteins that possess either a KASH-domain or SUN-domain (which form LINC [links the nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton] complexes),2 and the LEM-domain family of proteins, named for founding members Lap2, emerin and Man1.8,9 This review will focus on emerin, an extensively studied LEM-domain protein.

Emerin is a Conserved LEM-Domain Protein

The LEM-domain is a ~40-residue helix-loop-helix fold conserved both in eukaryotes and in prokaryotic DNA/RNA-binding proteins.10 With one exception (Lap2 proteins have a second LEM-domain that binds DNA),10 eukaryotic LEM-domains have one known function: they directly bind a conserved chromatin protein named barrier-to-autointegration factor (BAF).11-14 Atomic structures have been solved for the emerin LEM-domain (residues 1–47) either alone,15,16 or in complex with BAF.15

Human LEM-domain proteins are encoded by seven genes.9,17 These proteins and genes have acquired many names; for clarity this review will employ the “generally used” protein names indicated in Table 1. LEM-domain proteins are conserved in both multicellular and single-celled members of the Opisthokont lineage of eukaryotes, which includes fungi and multicellular animals (“metazoans”).18 For example the nematode worm C. elegans genome encodes three proteins orthologous to human emerin, Lem2 and Ankle1.19 The evolution of the LEM-domain has been thoughtfully discussed.20,21 In metazoans, at least, the LEM-domain appears to have a fundamental role in tethering chromatin to the NE. The fission yeast S. pombe, which lacks lamins and BAF, encodes two LEM-domain proteins orthologous to Lem2 and Man1.21,22 Man1 enriches with Swi6 (orthologous to human heterochromatin protein 1 [Hp1]) near telomeres.23 Overexpression of the LEM- (“Heh”-) domain of either Man1 or Lem2 causes chromatin to compact near the spindle pole body,22 consistent with the competitive release of telomeres (not centromeres) from sites of attachment at the NE.23 The conservation of LEM-domain proteins in yeast, apparently independently of both BAF and lamins, suggests LEM-domain proteins are intrinsically important for genome organization and nuclear structure.

Table 1. Human LEM-domain gene and protein nomenclature.

| NCBI Gene Symbol | HGNC Gene Symbol (name) | Gene AKA | Gene Aliases | Generally used protein name(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

LEMD1 |

LEMD1 (LEM domain containing 1) |

LEM1 |

LEMP-1, CT-50 |

Lem1, Lem5 |

|

LEMD2 |

LEMD2 (LEM domain containing 2) |

LEM2 |

NET25, dJ482C21.1 |

Lem2 |

|

LEMD3 |

LEMD3 (LEM domain containing 3) |

MAN1 |

MAN1 |

Man1 |

|

LEMD4 |

TMPO (Thymopoietin) |

LAP2 |

TP, LAP2, CMD1T, LEMD4, PRO0868, MGC61508 |

Lamina associated polypeptide 2 (Lap2α,β,γ,δ,ε or ζ) |

|

LEMD5 |

EMD (Emerin) |

|

LEMD5, STA, EDMD |

Emerin |

|

LEMD6 |

ANKLE1 (Ankyrin repeat and LEM domain containing 1) |

LEM3 |

LEM3, LEMD6, ANKRD41, FLJ39369 |

Ankle1 or Lem3 |

| LEMD7 | ANKLE2 (Ankyrin repeat and LEM domain containing 2) |

LEM4 | LEMD7, FLJ22280, FLJ36132, KIAA0692 | Ankle2 |

NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; HGNC, Human Gene Nomenclature Database

Emerin Contributes to Nuclear “Lamina” Structure and Function in Multicellular Animals

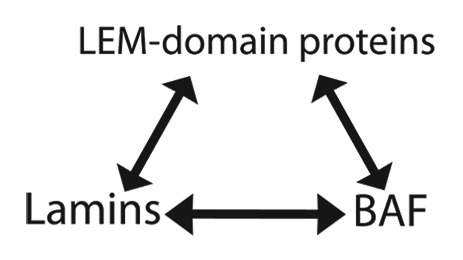

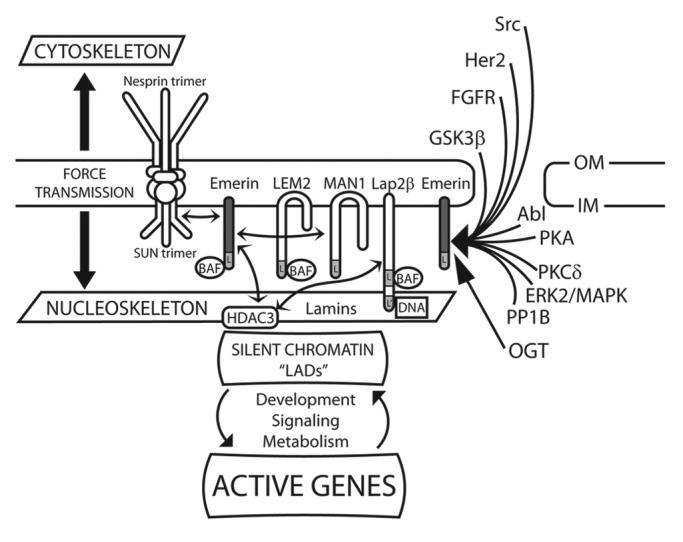

Emerin and several other LEM-domain proteins (e.g., Lap2β, Lem2, Man1) are integral membrane proteins that localize predominantly at the NE inner membrane. These LEM-domain proteins bind directly to lamins (nuclear intermediate filament proteins) and BAF,24 together forming a major component of NE-associated nucleoskeletal structure known as the nuclear “lamina”2,25 (Fig. 1). The structural inter-dependence of this “trio” of components was revealed by downregulating either lamin or BAF-1, or both Emr-1 and Lem-2, in C. elegans embryos— if any one component was missing, the other two failed to co-assemble, with severe consequences for mitotic chromosome segregation and postmitotic nuclear assembly.26-28 In mammalian cells certain LEM-domain proteins localize intriguingly, and dynamically, during mitosis. Lap2α (which is soluble, not membrane anchored) and BAF co-localize on telomeres during anaphase, and during telophase form “core” structures on chromatin at specific regions of nuclear envelope assembly near the spindle pole.29 These “core” structures transiently recruit and concentrate BAF, emerin and A-type lamin(s), and are distinct from neighboring “non-core” regions enriched in Lap2β, LBR and B-type lamins.29-31 “Core” regions are NPC-free, whereas “non-core” regions are NPC-rich.32 The mitotic roles of emerin and other LEM-domain proteins in mammals are major open questions. Further exploration is needed both to define these mitotic roles, which may be shared by multiple LEM-domain proteins (Table 1), and to determine their impact on genome activity, since mitosis appears to be crucial for LEM-domain proteins to establish functional (repressive) contact with silent chromatin.33

Figure 1. Nuclear “lamina” structure has three fundamental components: lamins, LEM-domain proteins and BAF (barrier-to-autointegration factor). These components bind each other with nanomolar affinity in vitro (see text). In C. elegans, loss of any one component (lamin or BAF, or two LEM-domain proteins [Emr-1 and Lem-2]) disrupts co-assembly of the other two and hence blocks nuclear reassembly after mitosis.

Emerin and Other LEM-domain Proteins Organize and Tether Chromatin at the NE

Functional overlap is a major theme for LEM-domain proteins. In C. elegans the two NE-localized LEM-domain proteins, Emr-1 and Lem-2, have overlapping roles in nuclear structure, mitosis and development,34 and are co-essential for viability.26 The two fission yeast proteins, Lem2 and Man1, localize at the NE inner membrane and are co-essential for nuclear structure.22 In mice, emerin and Lem2 have overlapping roles, along with Man1, in the regulation of MAP kinase signaling during myoblast differentiation.35 Emerin can also bind the N-terminal domain of Man1 directly,14 but whether or how this affects their functions is unknown. Among 16 proteins that bind emerin directly (discussed extensively below) are three “shared” partners (in addition to lamins and BAF) that also bind at least one other LEM-domain protein. These shared partners are Btf (BCL-associated transcription factor 1 [BCLAF1]),36 germ cell-less (GCL)37 and the chromatin-silencing enzyme HDAC3 (histone deacetylase 3). HDAC3 directly binds emerin38 and Lap2β.39 HDAC3 and the transcription factor cKrox co-mediate silent chromatin tethering to Lap2β at the NE; as noted above, these tethering complexes are established during mitosis,33 when the nucleoskeleton undergoes complex and dynamic reorganization and then reassembles nuclear structure.2 In all, four LEM-domain proteins—emerin,40 Lap2β,33 Otefin (in Drosophila)41 and Lem-2 (in C. elegans)42—along with A- and B-type lamin filaments40,43 mediate chromatin organization and tethering at the NE (Fig. 2). These discoveries are providing unique and unexpected insight into genome biology.44

Figure 2. Schematic depiction of the regulation, partners and selected functions of emerin at the nuclear envelope. Depiction of emerin and other LEM-domain proteins (Lem2, Man1 and Lap2β) at the inner membrane (IM) of the nuclear envelope. Double-headed arrows connect direct binding partners, including emerin (dark gray), SUN-domain proteins, BAF, HDAC3 and Man1. Direct binding to lamins is not indicated. Emerin has roles in signaling, mechano-transduction, nuclear architecture, chromatin tethering and gene regulation. Also depicted are enzymes and pathways that directly target or regulate emerin. “L” indicates the LEM-domain. “L-prime” [L’] in Lap2β indicates the DNA-binding “LEM-like” domain. OGT, O-GlcNAc transferase. OM, outer membrane.

Discovery of Emerin: Loss of Function Causes Emery-Dreifuss Muscular Dystrophy

The emerin gene (originally STA; renamed EMD) was identified in 1994 by genetic mapping45 of X-linked recessive Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (X-EDMD; Emery and Dreifuss, 1966).46 EDMD is characterized by contractures of major tendons, slowly progressive skeletal muscle wasting and weakness, and dilated cardiomyopathy with potentially lethal ventricular conduction system defects that can cause sudden cardiac arrest.47 In rare cases, EMD mutations cause limb-girdle muscular dystrophy or severe cardiac conduction defects.48,49 Two years after X-EDMD was genetically mapped came a surprise: emerin was revealed as a NE membrane protein.50,51 Emerin was the harbinger of a new category of human disease (“laminopathies”) caused by mutations in lamins or lamin-binding proteins.52,53 Indeed the emerin and lamin “proteomes” have become a rich source of candidate disease genes. For example EDMD is also caused by mutations in at least five other genes: LMNA (A-type lamins; numerous mutations reported),54 SYNE-1 (nesprin-1; three reported mutations),55 SYNE-2 (nesprin-2; one reported mutation),55 TMEM43 (LUMA; two reported mutations)56 or FHL1 (four-and-a-half LIM domains 1; seven reported mutations).57 Four of these proteins (FHL-1 is untested) interact with each other, and with emerin, suggesting EDMD disease is caused by the disruption of NE-anchored “links the nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton” (LINC) complexes that include these proteins2,55,58 (Fig. 2). In contrast to nesprins, SUN-proteins and lamin A, all of which directly transmit mechanical force,59,60 emerin is required to sense force and activate the downstream mechano-sensitive genes IEX-1 and EGR-1.61 The mechanisms by which emerin senses and signals mechanical force are unknown.

Emerin is expressed in essentially all tissues.62 This suggests the relative mildness of EDMD disease, which mainly affects striated muscle, may be due to the presence of another LEM-domain protein(s) that “backs up” or compensates for emerin loss, as seen for emerin and Lem2 during mouse myoblast differentiation.35 “Backup” function might also be provided by unidentified isoform(s) of Lap2, since the Lap2 gene (TMPO; Table 1) is upregulated in EDMD patient muscle,63 and a mutation in Lap2α is genetically linked to cardiomyopathy.64

Emerin Biogenesis and Nuclear Envelope Localization

Emerin is a 254-residue type-II integral membrane protein with a proposed 23-residue hydrophobic (transmembrane) domain near the C-terminus, and a tiny (11-residue) lumenal domain. Consistent with this domain organization, newly synthesized (presumably soluble) emerin polypeptides in the cytoplasm are inserted into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane post-translationally,65,66 possibly mediated by ATP-dependent TRC40/Asna-1 complexes that mediate the “guided entry of tail-anchored” (GET) pathway.67,68 Once inserted, emerin diffuses throughout the contiguous membranes of the ER/NE, including the “pore membrane” surrounding each NPC, where the outer and inner NE membranes are connected. Extensive FLIP and FRAP studies showed membrane-anchored emerin easily “slides past” the NPC because its cytoplasmically-exposed domain is small (~25 kD).66,69 Proteins with larger exposed domains (> 60 kD) fail to accumulate at the inner membrane.70 Alternative mechanisms to reach the inner membrane71,72 may not apply to emerin; emerin lacks “FG-repeats” and its predicted nuclear localization signal (residues 35–47)73,74 is not required for nuclear import,75 as discussed below (Fig. 3). Having reached the inner membrane, evidence suggests emerin is retained and accumulated by binding A-type lamins,76 for which human emerin has high (40 nM) affinity in vitro (Fig. 4).77 Note that emerin retention might alternatively or additionally require another partner disrupted by loss of A-type lamins. By FRAP analysis the diffusion constant of GFP-emerin at the NE is three times slower than the ER (0.10 ± 0.01 vs. 0.32 ± 0.01 μm2/second respectively).66 In cells that lack A-type lamins, emerin is more mobile and distributes equally throughout the NE and ER,69,76 supporting diffusion–retention models for emerin localization at the NE inner membrane.66,69

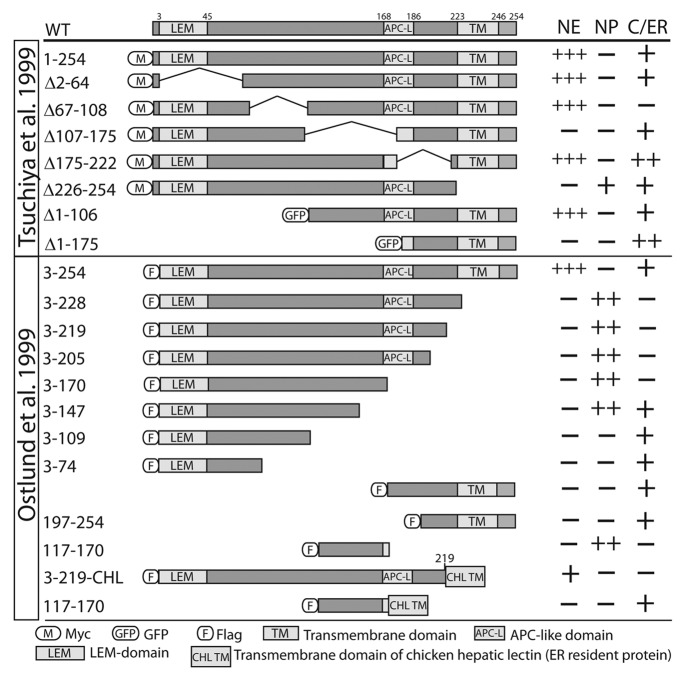

Figure 3. Localizations of epitope-tagged emerin polypeptides in cells. Summary of the localization of epitope-tagged emerin polypeptides (truncations, internal deletions or chimeras) expressed transiently in mammalian cells.66,75WT, wildtype emerin; M, myc-tag; GFP, green fluorescent protein; F, flag tag. Plus or minus indicate polypeptide localization predominately at the nuclear envelope (NE), nucleoplasm (NP) or cytoplasm/endoplasmic reticulum (C/ER), compared with full-length emerin (residues 1–254 or 3–254).

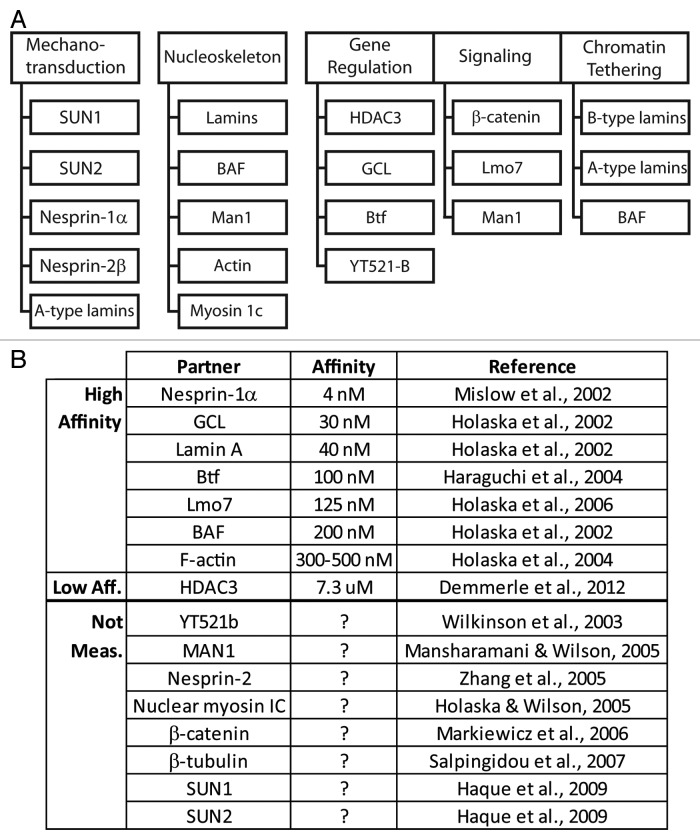

Figure 4. Direct binding partners of emerin. (A) Proteins that bind emerin directly in vitro, grouped based on their known or proposed functions in mechanotransduction, nucleoskeleton, gene regulation, signaling or chromatin tethering. (B) Direct partners and equilibrium binding affinity for human emerin in vitro, if known.

On the other hand, subpopulation(s) of emerin appear to localize elsewhere, including the NE outer membrane and the plasma membrane (see below). Outer membrane localization might be achieved by binding to high-affinity partners (e.g., nesprin-1 isoforms; Fig. 4B) at the NE outer membrane. Unconventional destinations (e.g., plasma membrane) might be achieved, we speculate, either by (1) direct posttranslational insertion of nascent emerin into alternative membrane(s), (2) diffusion onto ER vesicle membranes and trafficking to the plasma membrane, or (3) a hypothetical mechanism that “hides” the hydrophobic domain and thereby allows nascent emerin to associate as a soluble protein with partners outside the nucleus.

Unconventional Locations for Emerin Include the Intercalated Discs (ICDs) of Cardiomyocytes

Emerin localizes predominantly at the NE in skeletal and cardiac muscle.50,51 Similarly, immuno-gold EM labeling and digitonin studies showed emerin is abundant at the NE inner membrane in HeLa cells (e.g., ref. 78) and COS7 cells (e.g., refs 66, 75). Emerin has also been detected in the cytoplasm (presumably ER) of various tissues and cell types,51,74,79,80 the NE outer membrane81 and ER (consistent with its known biogenesis) and — most unexpectedly— the plasma membrane. The main caveat, in each case, is the specificity of emerin detection, since antibodies might recognize similar or identical epitopes on other proteins including other LEM-domain proteins, some of which are located in the cytoplasm (e.g., Lap2α and Lap2ζ).9

Emerin was detected at the NE outer membrane and on ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (“ERGIC”) vesicles in human dermal fibroblasts, and can also bind β-tubulin directly in vitro.81 The microtubule organizing center (“centrosome”), normally located ~1.5 μm from the NE, was more distant in emerin-null X-EDMD patient fibroblasts and in emerin-downregulated human dermal fibroblasts (average distance > 3.0 μm).81 Whether emerin influences centrosome positioning via LINC complexes, emerin-dependent gene misregulation or other mechanisms, and its potential implications for mitosis are open questions.

Endogenous emerin was detected at the plasma membrane in rat cardiomyocytes and in heart tissue from human, rat and mouse.82-84 One affinity-purified polyclonal antibody detected emerin at adhesive junctions of ICDs in human heart cryosections, both by indirect immunofluorescence and immuno-gold EM.82 Another study screened 15 monoclonal emerin antibodies (mAbs) by indirect immunofluorescence staining of ICDs: two were clearly positive, and five were faintly positive;83 note that lack of staining is inconclusive since specific epitopes might be masked by ICD-specific partners or posttranslational modifications. Further evidence was obtained using an affinity-purified antibody (APS20) raised in sheep against rat emerin residues 114–183, which detected the adherens junctions of rat heart tissue by immuno-gold EM labeling and indirect immunofluorescence staining.84 These findings suggest at least two locations for emerin in cardiomyocytes: the NE inner membrane and the adherens junctions of ICDs. How emerin localizes or functions at adherens junctions, which mechanically interconnect neighboring cardiomyocytes,85 and whether loss of this function contributes to EDMD heart pathology, are critical open questions. Of note, two direct partners of emerin, namely β-catenin84 and Lmo7,86 also localize at cardiac adherens junctions.

NE-Targeting Regions identified by expressing emerin polypeptides in cells

In two studies, cells that expressed truncated or internally-deleted emerin polypeptides were stained by indirect immunofluorescence to assess potential localization in the cytoplasm/ER (“C/ER”) or nucleoplasm (“NP”), or enrichment at the NE,66,75 as summarized in Figure 3. Emerin residues 3–219 (comprising almost the entire nucleoplasmic domain) concentrate at the NE inner membrane when fused to the transmembrane and lumenal domains of chicken hepatic lectin (CHL), a type II integral membrane protein normally found in the ER, endosomes and plasma membrane (Fig. 3, Emerin-CHL).66 Emerin residues 107–175 were required to block emerin aggregation in the cytosol (Fig. 3, Δ107–175).75 NE enrichment was reportedly unaffected by loss of residues 2–64, residues 1–106 or residues 175–222, and was slightly improved by deleting residues 67–108 (Fig. 3).75 This study also showed the full C-terminal half of emerin (residues 107–254) was sufficient to enrich at the NE (Fig. 3, GFP-Δ1–106).75

Emerin residues 3–205 and 3–147 accumulated in the nucleoplasm, whereas residues 3–109 remained in the cytoplasm; this suggested residues 110–147 either possess a non-canonical NLS, or associate with an NLS-bearing partner (“piggyback” import; Fig. 3).66 Residues 117–170 are indeed sufficient for import (Fig. 3),66 but the mechanism and relevance to membrane-anchored emerin are unknown. Piggyback mechanisms are possible, since mutations in this region (residues 117–170) disrupt binding to HDAC3, actin and lamin A (see below), all of which are imported into the nucleus as soluble proteins. In summary, the mechanisms of emerin enrichment at the NE are not yet understood, and are likely to involve a partner(s) other than lamins (e.g., nuclear protein 4.1R, discussed later).

Direct Partners and a Mutagenesis-Based Map of Functional Regions in Emerin

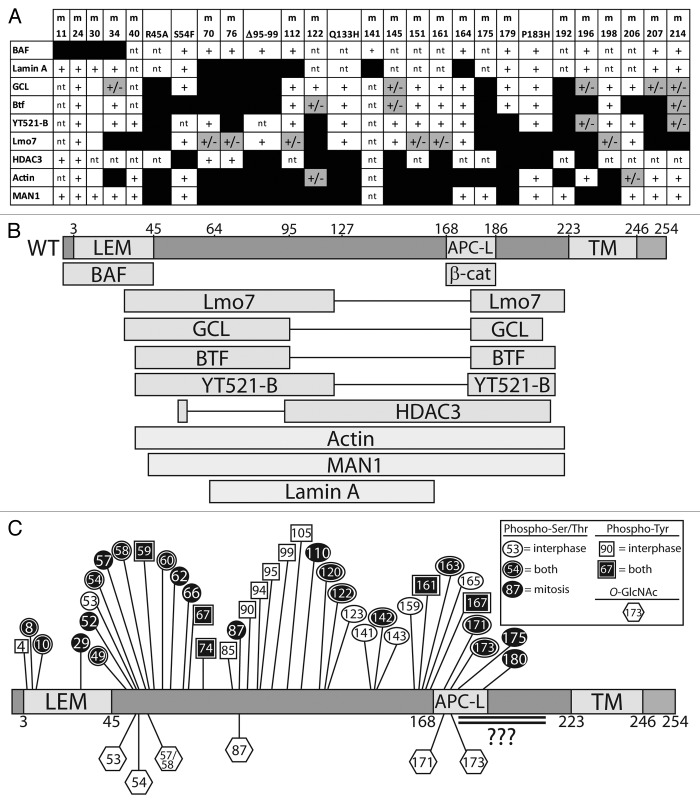

In addition to binding lamin A and BAF (nuclear “lamina” components), human emerin directly binds at least 14 other proteins (Fig. 4). Emerin has no known secondary structure other than its LEM-domain (residues ~4–44)16 and transmembrane domain (residues 223–246). To identify functional regions, two sets of clustered Ala-substitution mutations were generated in recombinant emerin (“m-series” mutations): one set targeted residues homologous or identical between emerin and Lap2β, postulated to mediate conserved or shared functions (Table 2).13 The second set of mutations targeted residues that differ between emerin and LAP2β; these were predicted to disrupt emerin-specific functions (Table 3).37 Also tested were four human mutations (S54F, Q133H, P183H, deletion of residues 95–99 [Δ95–99]) that were unusual: each is sufficient to cause emerin-null EDMD disease, even though the mutant protein localizes normally and is expressed at normal or near-normal (~60%) levels.87,88 Emerin polypeptides bearing these various mutations have been tested in vitro for binding to as many as eight different partners: BAF, lamin A, GCL, Btf, YT521-b, Lmo7, HDAC3, F-actin and Man1 (Fig. 5A). This research yielded a functional map based on the locations of mutations that disrupt binding to each partner (Fig. 5B).

Table 2. Summary of mutations in “conserved” emerin residues identical or homologus in Lap2β.13.

| Name | Wildtype | Mutated |

|---|---|---|

| M11 |

11EL |

11AA |

| M24 |

24GPVV |

24AAA |

| M30 |

30TR |

30AA |

| M34 |

34YEKK |

34AAA |

| S54F* |

54S |

54F |

| m70 |

70DADMY |

70AAMA |

| m76 |

76LPKKEDAL |

76PAKADAA |

| m112 |

112GPSRAVRQSVT |

112AASRAVAAAVA |

| m141 |

114SSSEEECKDR |

141AASAEECKAA |

| m164 |

164ITHYRPV |

164AAHARPA |

| m179 |

179LS |

179AA |

| m196 |

196SS |

196AA |

| m207 |

207RP |

207AA |

| m214 | 214GAGL | 214AAGA |

Sufficient to cause Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy

Table 3. Summary of mutations in emerin-specific residues not conserved in Lap2β.37.

| Name | Wildtype | Mutated |

|---|---|---|

| 45A |

45RRR |

45AAA |

| 45E |

45RRR |

45EEE |

| Δ95–99* |

95YEESY |

Deleted |

| Q133H* |

133Q |

133H |

| m122 |

122TS |

122AA |

| m145 |

145EE |

145AA |

| m151 |

151ER |

151AA |

| m161 |

161YQS |

161AAA |

| m175 |

175SSL |

175AAA |

| P183H* |

183P |

183H or 183T |

| m192 |

192SSSSS |

192ASAAA |

| m198 |

198SSWLTR |

198AAAAA |

| m206 | 206IRPE | 206AAPA |

Sufficient to cause Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy

Figure 5. Functional map based on emerin missense mutations that disrupt binding to specific partners. (A) Summary of binding results for each named partner, tested for binding to each “m-series” (clustered Ala substitutions) or EDMD-causing mutations in emerin (mutations specified in Tables 2 and 3). Scoring: normal binding (+), weakened binding (+/− and gray), and undetectable binding (black box). nt, not tested. (B) Results from (A) mapped schematically to the emerin polypeptide. APC-L, APC-like domain. TM, transmembrane domain. (C) Schematic diagram of known phosphorylation sites in emerin (see Fig. 6). Hexagons, O-GlcNAc sites; circles, phospho-Ser/Thr; squares, phospho-Tyr; white, asynchronous cultures; black, mitotic cultures and conditions. Black with outline, sites identified in both asynchronous and mitotic cells. Double-underlined region has at least two O-GlcNAc sites and potentially other modifications that are uncharacterized due to the large size of the corresponding trypic peptide and poor recovery by mass spectrometry.

Emerin Biochemistry and the Functional Implications of Known Partners

Few NE membrane proteins other than emerin have been studied at the biochemical level. The equilibrium binding affinity of emerin has been measured for eight partners in vitro (Fig. 4B). Human emerin binds with relatively high (4–500 nM) affinity to each of seven partners (nesprin-1α, GCL, lamin A, Btf, Lmo7, BAF and F-actin) and with lower affinity to HDAC3 (7.3 μM; Fig. 4B). Competition studies showed BAF and GCL compete with each other for binding to emerin, whereas GCL and lamin A can co-bind emerin.37 Six distinct emerin-containing multi-protein complexes were purified from HeLa cell nuclei, suggesting emerin might scaffold a variety of multi-protein complexes at the NE.89 We are still far from understanding these complexes or their functions. However studies of proteins that bind emerin, particularly lamin A, BAF, HDAC3 and GCL, discussed below, are beginning to illuminate daily “life” (protein-protein interactions) at the nuclear envelope.

Emerin binds structural components of both the NE (e.g., SUN1, SUN2, nesprins)90,91 and the nucleoskeleton (lamins, actin)77,92 (Fig. 4). Emerin also directly binds signaling transcription factors including β-catenin and Lmo7 (Fig. 4).93,94 These various partners suggest emerin might integrate a variety of mechanical and signaling “inputs,” and by unknown mechanisms convert these inputs into situation- or tissue-appropriate changes in gene activity. Indeed genes that are normally activated in response to mechanical force, fail to activate in emerin-deficient cells.61 Selected partners and their functional implications for emerin and “life at the NE” are summarized below.

Lamin A

Lamins A and C (lamins A/C) are major alternatively-spliced products of the LMNA gene that polymerize to form A-type nuclear intermediate filaments that concentrate near the inner nuclear membrane and are a major component of the nucleoskeleton.2 A-type lamins have roles in chromatin tethering, epigenetic regulation, DNA damage repair, mechanotransduction, replication and development.1,95 Lamin A has 28 reported direct partners besides emerin including Lem2,96 Man114 and BAF.37,97 A-type lamins are regulated by phosphorylation, SUMOylation, O-GlcNAcylation and other modifications (see ref. 97). Over 350 missense mutations in the LMNA gene have been linked to over 13 human diseases including EDMD, lipodystrophy, atypical Werner syndrome and Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS).98 Emerin missense mutations that disrupt binding to lamin A (Fig. 5A and B) are located centrally in emerin (residues 70–164), and affect residues that are identical or conserved in Lap2β (Table 2).13

Barrier-to-Autointegration Factor

The conserved LEM-domain of emerin (and other LEM-domain proteins) confers direct binding to an essential chromatin protein named Barrier-to-Autointegration Factor (BAF).24,99 BAF is an 89-residue (10 kD) protein that is highly conserved in multicellular eukaryotes.99 A homozygous missense mutation (A12T) in human BAF, which appears to destabilize the BAF protein (> 90% reduced protein level), causes Nestor-Guillermo progeria syndrome (NGPS).100,101 This syndrome is proposed to arise from reduced BAF protein. Emerin does not localize efficiently at the NE in NGPS cells,100 suggesting the mislocalization of emerin (and perhaps other LEM-domain proteins) also contributes to this syndrome. NGPS patients and HGPS patients share some clinical features including accelerated skin aging, lipoatrophy, osteoporosis and osteolysis.100 By contrast NGPS patients have no apparent cardiovascular defects, diabetes, or elevated blood triglycerides, which might explain why they are living longer (the two published patients were 24 and 32 y); HGPS patients die in their early teens from stroke or heart failure.102 Further study of NGPS may provide much-needed insight into BAF, a core component of nuclear lamina networks that “bridges” DNA, directly binds LEM-domain proteins, histones H3, H4 and selected linker histones103,104 and influences histone posttranslational modifications.105 BAF can also form higher-order complexes with DNA and Lap2β in vitro,106 and was detected in two distinct emerin-containing complexes isolated from HeLa cells.89 In C. elegans, BAF has a fundamental role in attaching chromatin to the NE inner membrane via LEM-domain proteins; this role is untested in mammalian cells.

BAF is essential for chromosome segregation, cell cycle progression and post-mitotic nuclear assembly.27,107,108 As noted above, BAF localizes to the so-called “core” regions of anaphase chromosomes at the earliest stages of nuclear assembly and is essential to recruit lamin A and emerin to this region of the reforming nuclear envelope.30,31 Genetic analysis of baf-1 null C. elegans showed BAF also has tissue-specific functions and is required for the maturation and survival of the germline, cell migration, vulva formation and muscle maintenance.109

BAF is required for the nuclease activity of a newly characterized human LEM-protein, Ankle1, expressed at highest levels in hematopoietic tissue (Table 1).11 BAF can bind chromatin and the LEM-domain of Ankle1 simultaneously.11 A loss of function mutation of the C. elegans ortholog, Lem3, which (like Ankle1) is a nuclease, causes phenotypes after irradiation that are similar to BAF-null worms,27 including defects in chromosome segregation and anaphase bridge progression.110 Interestingly C. elegans that lacked either emerin (emr-1 null) or Lem2 (lem-2 null) were also hypersensitive to DNA damage.110 Together these studies show BAF and LEM-domain proteins (including C. elegans emerin) have critical role(s) in the DNA damage response and genome integrity. There are hints that human emerin might also influence the DNA damage response, since emerin and BAF co-associate with the DNA repair proteins CUL4A and DDB2 within minutes after cell exposure to UV (UV) light.111 HeLa cells that overexpress laminopathy-causing mutations in GFP-lamin A,112 and HeLa cells downregulated for emerin, both show reduced phosphorylation of H2AX (“γ-H2AX” response) after treatment with inter-strand DNA crosslinking agents such as camptothecin (Berk and Wilson, unpublished results).

HDAC3

Emerin associates with all core components of the nuclear co-repressor (NCoR) complex,89 which represses genes by stably binding chromatin. One NCoR component is HDAC3, which deacetylates specific Lys residues in the histone H4 tail to promote NCoR interaction with chromatin. Emerin also binds HDAC3 directly.38 In the mutation-based functional map of emerin, HDAC3 is sensitive to diverse mutations (Fig. 5A and B), and is the only known partner that is disrupted by all four “special” EDMD-causing mutations.38 Furthermore emerin association increases the enzyme activity (Vmax) of HDAC3 by 2.5-fold in vitro, suggesting emerin enhances HDAC3-dependent gene silencing.38 This finding is consistent with an epigenetic phenotype (globally increased H4K5 acetylation) seen in emerin-downregulated cells and emerin-null mouse fibroblasts.38 Thus HDAC3-emerin association may be fundamentally important for tissue-specific gene repression. The LEM-domain protein LAP2β also binds HDAC3 directly,39 and influences the levels of histone H4 acetylation.113 Notably Lap2β interaction with HDAC3 is required for the NE tethering of Lamina Associated Domains (LADs) of DNA, specifically LADs enriched in cKrox binding sites (GAGA sequence).33 These findings support overlapping roles for emerin and Lap2β in tissue-specific gene silencing and tethering at the NE.

Btf and GCL

Less is known about two other “shared” partners, Btf and GCL. Btf (BCLAF1), which binds emerin36 and Man1,9,14 is a poorly understood, multifunctional protein with roles in DNA damage response,114,115 apoptosis,36,116,117 transcriptional regulation,118 and development.119 In response to DNA damage, Btf localizes to sites of damage114 and can interact with protein kinase C δ to form a complex that activates the p53 promoter.115 Most Btf is sequestered in the cytoplasm by anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, but then accumulates at the NE after apoptosis is induced.36,116 Other work suggests Btf is an mRNA splicing factor36,120,121 that associates with ribonucleoprotein complexes.118,120 The phenotypes of Btf-null mice include polydactyly, deficient ex vivo T cell activation, and postnatal death due to improper lung development.119 Emerin also has poorly understood roles in regulating mRNA splice site selection by another partner, named YT521B.122 Why Btf associates with emerin is unknown, but one can speculate that mRNA splicing or possibly apoptosis might be misregulated in emerin-deficient muscle.

GCL, which binds Lap2β, emerin and Man1,14,37,39 is a conserved protein that directly binds the DP subunit of E2F and DP heterodimers, which activate genes required for entry into S-phase. Emerin or Lap2β, in conjunction with GCL, effectively co-repress E2F and DP-dependent promoters in vivo.37,39,123 These same genes are well known targets of repression by Rb, which directly binds the E2F subunit. This co-repression of E2F-DP dependent promoters by emerin and GCL implicates emerin (and other LEM-domain proteins) in proliferation control. One study reported increased proliferation in emerin-null human fibroblasts.93 Interestingly GCL also associates with, and can recruit to the NE, a family of primate-specific “cancer-testis antigen” proteins named GAGE,124 which are normally expressed only in male germ cells, but are highly upregulated in many cancers.125 Whether GAGE influences the functions of GCL or LEM-domain proteins during cancer are open questions. Whether emerin and its LEM-domain brethren share other partners is unknown, due to gaps in knowledge about most other LEM-domain proteins.

SUN-Domain Proteins and Nesprins

Emerin binds directly to SUN-domain proteins and nesprins,90,91 the core integral membrane components of LINC complexes.126 LINC complexes transmit mechanical force across the NE to the nuclear lamina nucleoskeleton,127 and help maintain a uniform distance between the inner and outer membranes of the NE (for a review, see ref. 2). Emerin binding to nesprins was studied using relatively short isoforms, nesprin-1α and nesprin-2β, which are partly or fully included within most related isoforms.90,128 However it is uncertain which if any nesprin isoforms localize at the NE inner membrane.129 By contrast SUN-domain proteins localize almost exclusively at the NE inner membrane. Emerin binds the nucleoplasmic domains of SUN1 (SUN1 residues 223–302) and SUN2 (specific residues unmapped).91 Much more work is needed to understand how LINC complexes contact lamins and emerin.

F-actin and Nuclear Myosin 1c

Emerin directly binds (and caps) the pointed end of actin filaments, stabilizing F-actin in vitro.92 Emerin also binds the molecular motor, nuclear myosin Ic, directly in vitro even when myosin is “burning” ATP.89 These results suggest emerin might anchor “cortical” actin-myosin networks near the NE. Emerin also associates (at least indirectly; direct binding not tested) with the multifunctional structural protein 4.1R in vivo, which directly binds actin and spectrin to form a ternary complex,130 and is required for mitotic spindle function and nuclear assembly.131,132 The nuclear localizations of emerin and 4.1R are mutually dependent: loss of 4.1R decreases emerin retention at the INM and vice-versa, and loss of either protein increases accumulation of β-catenin in the nucleus.93,133 The nucleoskeletal roles of actin, myosin, spectrin and 4.1 are major understudied areas of cell biology.2

Emerin is required for the nuclear accumulation and activity of the mechanosensitive transcription factor, megakeryoblastic leukemia 1 (MKL1).134 MKL1 localizes predominantly in the cytoplasm, but moves into the nucleus in response to mechanically-induced increases in actin polymerization.135,136 In the nucleus, MKL1 and serum response factor (SRF) co-activate genes encoding cytoskeletal proteins.137 Lmna-/- and Emd-/ymouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) have reduced MKL1 nuclear localization after mechanical stimulation. Ectopic overexpression of GFP-emerin in Lmna-/- or Emd-/y MEFs rescues MKL1 nuclear localization. Three emerin mutants incapable of binding actin (clustered Ala-substitutions m151 or m164, and “special” EDMD-causing mutation Q133H) failed to rescue MKL1 nuclear accumulation,134 suggesting emerin association with actin is required. However other functions of emerin may also contribute to the nuclear accumulation of MKL1: the emerin m151 and Q133H mutations also disrupt binding to the LEM-domain protein Man114 (see Table 3; Fig. 5A) and have not yet been tested for binding to lamin A, and the m164 mutation also disrupts binding to lamin A13 (Table 2; Fig. 5A). Whether MKL1 binds emerin directly is unknown.

Emerin Binds β-catenin and Lmo7 and Regulates Signaling from the Cell Surface

Emerin directly binds two signaling transcription factors that shuttle between the cell surface and nucleus: one is the well-known protein β-catenin,93 which mediates Wnt signaling; the other is Lim-domain-only 7 (Lmo7).94 Emerin binds β-catenin directly, and emerin-null fibroblasts accumulate high levels of β-catenin in the nucleus, grow rapidly, and improperly continue proliferating in low serum.93 This suggests emerin normally attenuates Wnt signaling. Similarly, Lmo7 is widely distributed in the cytoplasm and cell surface (adherens junctions) and also shuttles into the nucleus where its accumulation appears to be inhibited by emerin.86,94 Lmo7 also co-localizes with p130Cas at focal adhesions, and is inhibited by p130Cas (Wozniak et al., forthcoming). Lmo7 is a transcription factor that activates many genes including the emerin gene; evidence suggests Lmo7 binding to emerin protein feedback-regulates emerin gene expression.94 Lmo7 is expressed at elevated levels in heart and muscle, and Lmo7-null mice have dystrophic muscle (JM Holaska, personal communication), suggesting Lmo7 association with emerin is highly relevant to EDMD disease.138,139 Lmo7 activates the promoters of myogenic genes (encoding MyoD, Myf5, Pax3) whose expression is critical for early myogenic differentiation. These genes are turned off after myotubes form, concomitant with increased emerin expression; emerin is proposed to both recruit Lmo7 away from these promoters, and to drive Lmo7 exit from the nucleus.140

Studies of Emerin–Null EDMD Patient Cells and Mouse Models

Emerin-null mice display subtle defects in motor coordination and muscle regeneration and mild atrioventricular conduction defects with age.141,142 This unfortunately has limited their use as an EDMD model.

In EDMD patient muscle and emerin-null mice, loss of emerin misregulates certain muscle-specific and heart-relevant genes regulated by Rb and MyoD.63,142,143 MyoD-dependent genes are crucial for muscle development and repair. Some genes misregulated in EDMD (including CREBBP, NAP1L1 and RBL2), and the emerin gene itself, depend for their transcriptional activation on Lmo7.94 In regenerating emerin-null mouse muscle, Rb remains inappropriately hyper-phosphorylated, and cells that should arrest during differentiation instead continue proliferating.142 The mechanisms by which Rb–MyoD-regulated pathways depend on emerin are unknown, but might involve loss of emerin-dependent gene tethering at the NE. Rb/MyoD-regulated pathways are also required in muscle stem (“satellite”) cells, which express emerin and have long-term roles in muscle homeostasis, repair and regeneration.144 Loss of emerin in satellite cells is proposed to reduce their capacity to repair and regenerate muscle tissue,145 due in part to increased nuclear fragility54 and reduced mechano-transduction.61

Loss of emerin also affects genes regulated by the JNK, MAPK, NF-κB, integrin, Wnt and TGFβ signaling pathways.54 The nuclear localization and activity of ERK1/2 (a MAPK) increases in emerin-null mouse hearts.143 Thus emerin is proposed to block or attenuate the nuclear accumulation of at least three signaling proteins: ERK1/2, Lmo7 and β-catenin. The mechanism(s) by which emerin inhibits nuclear accumulation of these key regulators are important open questions. A different LEM-domain protein, Man1, inhibits TGFβ/BMP signaling during vertebrate development by directly binding and inhibiting R-Smads.146-149 Man1 is proposed to inhibit TGFβ/BMP signaling by stimulating dephosphorylation of Smads and hence favoring nuclear export.150 Interestingly β-catenin export is mediated by two proteins: 14-3-3 (ε and other isoforms) and the Wnt pathway inhibitor Chibby.151,152 We speculate emerin might promote β-catenin export by “scaffolding” its co-association with Chibby and 14-3-3, since 14-3-3 isoforms β, ε and θ were recovered as potential components of two emerin-containing complexes.89

Mechanical Properties of Emerin-Deficient Nuclei and Selective “Pruning” of “Bad” Nuclear Structures by Autophagy

Muscle sections from seven X-linked EDMD patients revealed severe nuclear shape disruptions in a subset of nuclei in fibroblasts, smooth muscle and skeletal muscle. The frequency of abnormal nuclei in muscle tissue increased with patient age, and on average 20–25% of nuclei were misshapen in a manner consistent with apoptosis.153,154 Remarkably, prior to apoptosis, muscle cells first deploy a strategy in which the structurally abnormal (e.g., blebbed or herniated) regions of emerin-null nuclei, including chromatin, are specifically recognized and selectively destroyed by autophagy.141,155 When autophagy was experimentally blocked, the entire nucleus underwent apoptosis.141,155 The pathway(s) that identify structurally defective regions of the NE and trigger “surgical” removal via autophagy are unknown.

In cultured MEFs, the emerin-null condition increases the percentage of cells with nuclear morphology defects, but not as much as the lmna-null condition.61 Emerin-null MEFs also have higher rates of apoptosis after continuous mechanical strain, possibly because they fail to activate the mechanosensitive gene IEX-1, which protects against apoptosis.61 Reduced NE elasticity in emerin-null MEFs may also contribute to nuclear fragility in EDMD patients.156 Collectively these findings suggest emerin contributes to nuclear architecture and is important to maintain the structural integrity and function of the NE.

Extensive Emerin Phosphorylation during Mitosis and Interphase

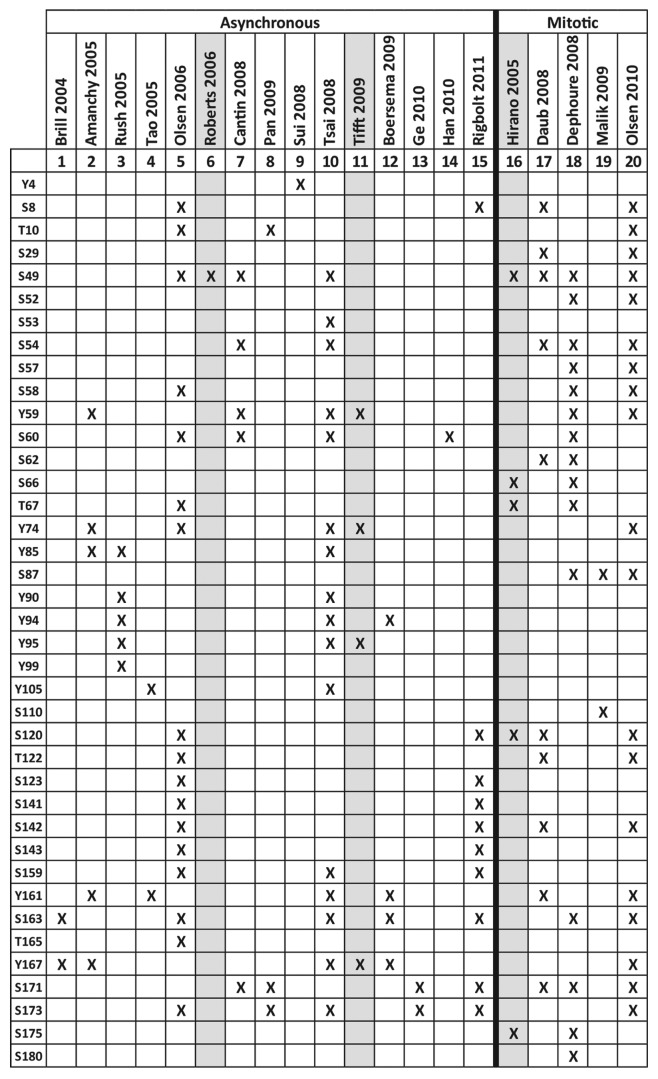

Human emerin has at least 39 published sites of phosphorylation in vivo (25 Ser, 4 Thr, 11 Tyr) as summarized in Figures 5C and 6.157-176 Although the responsible kinases/pathways and functional consequences of emerin phosphorylation remain poorly understood, one broad theme is emerging: emerin appears to be a major target of phosphorylation not only during mitosis but also during interphase.

Figure 6. Published human emerin phosphorylation sites. X indicates emerin phosphorylation sites identified in asynchronous or mitotic cells. Grey columns indicate emerin-specific studies; other columns are high-throughput studies. (S), Ser. (T), Thr. (Y), Tyr. These results are compiled from references 157–176.

Emerin, lamins and other key NE proteins are hyperphosphorylated during mitotic prophase to trigger and regulate their mutual detachment, nucleoskeletal reorganization and NE disassembly.65,173,177,178 Emerin is phosphorylated at 26 sites (including tyrosines) during mitosis,162,174-176 with up to 83–94% stoichiometry.162,175

Emerin is also phosphorylated during interphase at 30 reported sites (Figs. 5C and Fig. 6). Only a few kinases, and one phosphatase, that target emerin have been identified,84,163,167,179-181 as summarized in Table 4. Emerin is phosphorylated on Ser49 and at least one other residue by PKA.163 Emerin is also targeted by the metabolically important kinase GSK3β at unknown site(s) in vitro.84

Table 4. Enzymes that target emerin.

| Identified sites | Assay | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ser/Thr kinases |

PKA |

Roberts et al., 2006 |

S49 |

in vitro, MS |

| |

PKCδ |

Leach et al., 2007 |

(nd) |

in vivo, inhibitors |

| |

ERK2/MAPK |

Bukong et al., 2010 |

(nd) |

in vivo, inhibitors, in vitro |

| |

GSK3β |

Wheeler et al., 2010 |

(nd) |

in vitro |

|

Tyrosine kinases |

Src |

Tifft et al., 2009 |

Y59, Y74, Y95 |

in vitro, MS / in vivo |

| |

Abl |

Tifft et al., 2009 |

Y167 |

in vitro, MS |

| |

Her2 |

Tifft et al., 2009, Bose et al. 2006 |

(nd) |

in vivo |

|

Phosphatases |

PTP1B |

Yip et al., 2012 |

(nd) |

in vivo |

|

Glyco-transferases |

OGT |

Berk et al., submitted |

S53, S54, S57/S58, S87, S171, S173 |

in vitro, MS |

| OGT | Berk et al., submitted | S53, S54, S173 | in vivo |

* MS, mass spectrometry. nd, not determined.

A new pathway was reported in postsynaptic neurons, wherein nascent RNPs exit the nucleus directly through the NE; this pathway involves PKC-dependent hyperphosphorylation of lamin A.182 This pathway is proposed to be exploited in cells infected with Herpes simplex virus type 1, where emerin is targeted by the virus-encoded kinase US3 and cellular PKCδ as a mechanism for the virus to directly bud and exit at the NE.179,183 Emerin is also hyperphosphorylated by the Kaposi sarcoma associated herpesvirus.184 The MAPK pathway kinase ERK2 phosphorylates emerin directly both in vitro, and during nuclear egress of vesicular stomatitis virus G-protein-pseudotyped human and feline immunodeficiency viruses.185 This virus-induced hyper-phosphorylation causes emerin to mislocalize and might represent a viral strategy to hijack the host RNP-egress pathway.179,182,183

Emerin is nearly 10-fold Tyr hyper-phosphorylated in NIH3T3 cells that overexpress Her2.167,181 At least two nonreceptor Tyr kinases target emerin directly: Src specifically phosphorylates at least three residues (Y59, Y74, Y95) and Abl targets at least one (Y167).167 The Src-regulated sites are critical for BAF binding, since the triple Y to F substitution (at Y59, Y74 and Y95) decreases BAF binding by 70% in vivo.167 All three sites are phosphorylated during interphase (Fig. 6).158,166 Emerin is also ubiquitinylated at K88,186,187 but the specific context and consequences of this modification, like phosphorylation, are unknown. These diverse modifications, especially Tyr-phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation (discussed below), suggest emerin is regulated by tissue-specific signaling, potentially as a mechanism for “crosstalk” regulation of gene expression at the NE.

One potential therapy for EDMD, being developed by Worman and colleagues, is based on their discovery that MAP kinase signaling is overactive in lmna- or emerin-deficient mouse hearts; presymptomatic treatment with an ERK kinase inhibitor prevented dilated cardiomyopathy in an autosomal-dominant Lmna EDMD mouse model.188 Additional pharmacological strategies to treat EDMD may emerge from a better understanding of the kinases and other enzymes that regulate emerin itself or other (potentially “compensating”) LEM-domain proteins.

Emerin is Sweet: Regulation by O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine Transferase

Emerin is directly regulated by O-GlcNAc transferase (“OGT”; UDP-N-acetylglucosamine-peptide β-N-acetylglucosaminyl-transferase), an essential enzyme that attaches a single β-N-acetylglucosamine sugar to Ser/Thr residues of target proteins.189 The OGT-null condition in mice is lethal at embryonic stage E4.5, and in embryonic stem cells.189,190 Similarly, mice null for OGA (β-N-acetylglucosaminidase), the enzyme that removes O-GlcNAc, have delayed development and die at birth, with severe defects in mitosis.191 OGT is a pleiotropic enzyme with critical roles in the cellular stress response,192-194 mitosis,195 epigenetic regulation196 and transcriptional regulation.197 O-GlcNAcylation is highly dynamic, influences target proteins at many different levels and can compete or cooperate with phosphorylation to regulate specific sites.189 Emerin is highly O-GlcNAcylated in mammalian cells; in vitro studies identified five sites (Ser53, Ser54, Ser87, Ser171 and Ser173) and revealed at least three additional sites.198 Two sites (Ser53 and Ser54) are each individually critical for overall emerin O-GlcNAcylation not only in cells but also in vitro, suggesting potential control of emerin conformation. A third site (Ser173) is proposed to function as a molecular “switch”: O-GlcNAcylation at Ser173 promotes emerin binding to BAF, whereas Ser173 phosphorylation promotes emerin hyperphosphorylation and reduces BAF association in cells.198 All five identified O-GlcNAc sites in emerin are phosphorylated during mitosis (Fig. 5C), suggesting OGT and mitotic kinases might compete for control of emerin.

Concluding Remarks

Basic biochemical, cellular and genetic studies of emerin have yielded unprecedented insight into the structure and function of the nuclear envelope and nuclear lamina networks, and the fundamental roles of the conserved LEM-domain protein family. Perhaps most surprising, and frustrating in terms of EDMD disease therapy, is the sheer variety of functions to which emerin contributes— from mitosis and chromosome segregation, to silent chromatin tethering, mechano-transduction and signaling. However emerin’s roles in signaling have encouragingly suggested the first potential pharmacological treatment for EDMD. Further biochemical studies and human gene mapping studies will continue to complement each other: proteins that bind emerin represent candidate EDMD genes, and each mapped EDMD gene is a vital clue to understanding both human laminopathy disease and NE-dependent mechanisms of signaling and genome control. Given the many open questions in this young field, we wish to emphasize the dual importance of continuing both directly EDMD-relevant, and basic curiosity-driven, research. Both strategies are crucial to understand emerin and its fellow LEM-domain proteins, and uncover their overlapping vs. unique roles in human physiology that might lead to new therapies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Shelley Sazer, Jim Holaska, Eric Schirmer and Howard Worman for comments on this manuscript, and gratefully acknowledge research funding from the National Institutes of Health (RO1 GM048646 to KLW) and the Mills family.

Submitted

06/17/2013

Revised

07/10/2013

Accepted

07/14/2013

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/nucleus/article/25751

References

- 1.Dittmer TA, Misteli T. The lamin protein family. Genome Biol. 2011;12:222. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-5-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon DN, Wilson KL. The nucleoskeleton as a genome-associated dynamic ‘network of networks’. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:695–708. doi: 10.1038/nrm3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schirmer EC, Florens L, Guan T, Yates JR, 3rd, Gerace L. Nuclear membrane proteins with potential disease links found by subtractive proteomics. Science. 2003;301:1380–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1088176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkie GS, Korfali N, Swanson SK, Malik P, Srsen V, Batrakou DG, et al. Several novel nuclear envelope transmembrane proteins identified in skeletal muscle have cytoskeletal associations. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:003129. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.003129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korfali N, Wilkie GS, Swanson SK, Srsen V, Batrakou DG, Fairley EA, et al. The leukocyte nuclear envelope proteome varies with cell activation and contains novel transmembrane proteins that affect genome architecture. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:2571–85. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.002915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuleger N, Boyle S, Kelly DA, de Las Heras JI, Lazou V, Korfali N, et al. Specific nuclear envelope transmembrane proteins can promote the location of chromosomes to and from the nuclear periphery. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-2-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korfali N, Srsen V, Waterfall M, Batrakou DG, Pekovic V, Hutchison CJ, et al. A flow cytometry-based screen of nuclear envelope transmembrane proteins identifies NET4/Tmem53 as involved in stress-dependent cell cycle withdrawal. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin F, Blake DL, Callebaut I, Skerjanc IS, Holmer L, McBurney MW, et al. MAN1, an inner nuclear membrane protein that shares the LEM domain with lamina-associated polypeptide 2 and emerin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4840–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner N, Krohne G. LEM-Domain proteins: new insights into lamin-interacting proteins. Int Rev Cytol. 2007;261:1–46. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(07)61001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai M, Huang Y, Ghirlando R, Wilson KL, Craigie R, Clore GM. Solution structure of the constant region of nuclear envelope protein LAP2 reveals two LEM-domain structures: one binds BAF and the other binds DNA. EMBO J. 2001;20:4399–407. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brachner A, Braun J, Ghodgaonkar M, Castor D, Zlopasa L, Ehrlich V, et al. The endonuclease Ankle1 requires its LEM and GIY-YIG motifs for DNA cleavage in vivo. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1048–57. doi: 10.1242/jcs.098392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai M, Huang Y, Ghirlando R, Wilson KL, Craigie R, Clore GM. Solution structure of the constant region of nuclear envelope protein LAP2 reveals two LEM-domain structures: one binds BAF and the other binds DNA. EMBO J. 2001;20:4399–407. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee KK, Haraguchi T, Lee RS, Koujin T, Hiraoka Y, Wilson KL. Distinct functional domains in emerin bind lamin A and DNA-bridging protein BAF. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4567–73. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mansharamani M, Wilson KL. Direct binding of nuclear membrane protein MAN1 to emerin in vitro and two modes of binding to barrier-to-autointegration factor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13863–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413020200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai M, Huang Y, Suh JY, Louis JM, Ghirlando R, Craigie R, et al. Solution NMR structure of the barrier-to-autointegration factor-Emerin complex. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14525–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700576200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolff N, Gilquin B, Courchay K, Callebaut I, Worman HJ, Zinn-Justin S. Structural analysis of emerin, an inner nuclear membrane protein mutated in X-linked Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. FEBS Lett. 2001;501:171–6. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02649-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee K, Wilson K. All in the family: evidence for four new LEM-domain proteins Lem2 (NET-25), Lem3, Lem4 and Lem5 in the human genome. Oxford, UK: BIOS Scientific Publishers LTD, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson KL, Dawson SC. Evolution: functional evolution of nuclear structure. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:171–81. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201103171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee KK, Gruenbaum Y, Spann P, Liu J, Wilson KL. C. elegans nuclear envelope proteins emerin, MAN1, lamin, and nucleoporins reveal unique timing of nuclear envelope breakdown during mitosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3089–99. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.9.3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brachner A, Foisner R. Evolvement of LEM proteins as chromatin tethers at the nuclear periphery. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:1735–41. doi: 10.1042/BST20110724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mans BJ, Anantharaman V, Aravind L, Koonin EV. Comparative genomics, evolution and origins of the nuclear envelope and nuclear pore complex. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:1612–37. doi: 10.4161/cc.3.12.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez Y, Saito A, Sazer S. Fission yeast Lem2 and Man1 perform fundamental functions of the animal cell nuclear lamina. Nucleus. 2012;3:60–76. doi: 10.4161/nucl.18824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steglich B, Filion GJ, van Steensel B, Ekwall K. The inner nuclear membrane proteins Man1 and Ima1 link to two different types of chromatin at the nuclear periphery in S. pombe. Nucleus. 2012;3:77–87. doi: 10.4161/nucl.18825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Margalit A, Brachner A, Gotzmann J, Foisner R, Gruenbaum Y. Barrier-to-autointegration factor--a BAFfling little protein. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:202–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burke B, Stewart CL. The nuclear lamins: flexibility in function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:13–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J, Lee KK, Segura-Totten M, Neufeld E, Wilson KL, Gruenbaum Y. MAN1 and emerin have overlapping function(s) essential for chromosome segregation and cell division in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4598–603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730821100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Margalit A, Segura-Totten M, Gruenbaum Y, Wilson KL. Barrier-to-autointegration factor is required to segregate and enclose chromosomes within the nuclear envelope and assemble the nuclear lamina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3290–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408364102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu J, Rolef Ben-Shahar T, Riemer D, Treinin M, Spann P, Weber K, et al. Essential roles for Caenorhabditis elegans lamin gene in nuclear organization, cell cycle progression, and spatial organization of nuclear pore complexes. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3937–47. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.11.3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dechat T, Gajewski A, Korbei B, Gerlich D, Daigle N, Haraguchi T, et al. LAP2alpha and BAF transiently localize to telomeres and specific regions on chromatin during nuclear assembly. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:6117–28. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haraguchi T, Kojidani T, Koujin T, Shimi T, Osakada H, Mori C, et al. Live cell imaging and electron microscopy reveal dynamic processes of BAF-directed nuclear envelope assembly. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2540–54. doi: 10.1242/jcs.033597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haraguchi T, Koujin T, Segura-Totten M, Lee KK, Matsuoka Y, Yoneda Y, et al. BAF is required for emerin assembly into the reforming nuclear envelope. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4575–85. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clever M, Funakoshi T, Mimura Y, Takagi M, Imamoto N. The nucleoporin ELYS/Mel28 regulates nuclear envelope subdomain formation in HeLa cells. Nucleus. 2012;3:187–99. doi: 10.4161/nucl.19595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zullo JM, Demarco IA, Piqué-Regi R, Gaffney DJ, Epstein CB, Spooner CJ, et al. DNA sequence-dependent compartmentalization and silencing of chromatin at the nuclear lamina. Cell. 2012;149:1474–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barkan R, Zahand AJ, Sharabi K, Lamm AT, Feinstein N, Haithcock E, et al. Ce-emerin and LEM-2: essential roles in Caenorhabditis elegans development, muscle function, and mitosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:543–52. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-06-0505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huber MD, Guan T, Gerace L. Overlapping functions of nuclear envelope proteins NET25 (Lem2) and emerin in regulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in myoblast differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5718–28. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00270-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haraguchi T, Holaska JM, Yamane M, Koujin T, Hashiguchi N, Mori C, et al. Emerin binding to Btf, a death-promoting transcriptional repressor, is disrupted by a missense mutation that causes Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:1035–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holaska JM, Lee KK, Kowalski AK, Wilson KL. Transcriptional repressor germ cell-less (GCL) and barrier to autointegration factor (BAF) compete for binding to emerin in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6969–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demmerle J, Koch AJ, Holaska JM. The nuclear envelope protein emerin binds directly to histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) and activates HDAC3 activity. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:22080–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.325308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nili E, Cojocaru GS, Kalma Y, Ginsberg D, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, et al. Nuclear membrane protein LAP2beta mediates transcriptional repression alone and together with its binding partner GCL (germ-cell-less) J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3297–307. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.18.3297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reddy KL, Zullo JM, Bertolino E, Singh H. Transcriptional repression mediated by repositioning of genes to the nuclear lamina. Nature. 2008;452:243–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sui L, Yang Y. Distinct effects of nuclear membrane localization on gene transcription silencing in Drosophila S2 cells and germ cells. J Genet Genomics. 2011;38:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jcg.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ikegami K, Egelhofer TA, Strome S, Lieb JD. Caenorhabditis elegans chromosome arms are anchored to the nuclear membrane via discontinuous association with LEM-2. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R120. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-12-r120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guelen L, Pagie L, Brasset E, Meuleman W, Faza MB, Talhout W, et al. Domain organization of human chromosomes revealed by mapping of nuclear lamina interactions. Nature. 2008;453:948–51. doi: 10.1038/nature06947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bickmore WA, van Steensel B. Genome architecture: domain organization of interphase chromosomes. Cell. 2013;152:1270–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bione S, Maestrini E, Rivella S, Mancini M, Regis S, Romeo G, et al. Identification of a novel X-linked gene responsible for Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1994;8:323–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emery AE, Dreifuss FE. Unusual type of benign x-linked muscular dystrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1966;29:338–42. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.29.4.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonne G, Leturcq F, Ben Yaou R. Emery-Dreifuss Muscular Dystrophy. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, Adam MP, eds. Seattle: GeneReviews, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ura S, Hayashi YK, Goto K, Astejada MN, Murakami T, Nagato M, et al. Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy due to emerin gene mutations. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1038–41. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.7.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vohanka S, Vytopil M, Bednarik J, Lukas Z, Kadanka Z, Schildberger J, et al. A mutation in the X-linked Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy gene in a patient affected with conduction cardiomyopathy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2001;11:411–3. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8966(00)00206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manilal S, Nguyen TM, Sewry CA, Morris GE. The Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy protein, emerin, is a nuclear membrane protein. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:801–8. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.6.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagano A, Koga R, Ogawa M, Kurano Y, Kawada J, Okada R, et al. Emerin deficiency at the nuclear membrane in patients with Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1996;12:254–9. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Méndez-López I, Worman HJ. Inner nuclear membrane proteins: impact on human disease. Chromosoma. 2012;121:153–67. doi: 10.1007/s00412-012-0360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burke B, Stewart CL. The laminopathies: the functional architecture of the nucleus and its contribution to disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:369–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muchir A, Worman HJ. Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2007;7:78–83. doi: 10.1007/s11910-007-0025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Q, Bethmann C, Worth NF, Davies JD, Wasner C, Feuer A, et al. Nesprin-1 and -2 are involved in the pathogenesis of Emery Dreifuss muscular dystrophy and are critical for nuclear envelope integrity. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2816–33. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liang WC, Mitsuhashi H, Keduka E, Nonaka I, Noguchi S, Nishino I, et al. TMEM43 mutations in Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy-related myopathy. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:1005–13. doi: 10.1002/ana.22338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gueneau L, Bertrand AT, Jais JP, Salih MA, Stojkovic T, Wehnert M, et al. Mutations of the FHL1 gene cause Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:338–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson KL, Berk JM. The nuclear envelope at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1973–8. doi: 10.1242/jcs.019042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lombardi ML, Jaalouk DE, Shanahan CM, Burke B, Roux KJ, Lammerding J. The interaction between nesprins and sun proteins at the nuclear envelope is critical for force transmission between the nucleus and cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:26743–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.233700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lammerding J, Schulze PC, Takahashi T, Kozlov S, Sullivan T, Kamm RD, et al. Lamin A/C deficiency causes defective nuclear mechanics and mechanotransduction. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:370–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI19670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lammerding J, Hsiao J, Schulze PC, Kozlov S, Stewart CL, Lee RT. Abnormal nuclear shape and impaired mechanotransduction in emerin-deficient cells. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:781–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tunnah D, Sewry CA, Vaux D, Schirmer EC, Morris GE. The apparent absence of lamin B1 and emerin in many tissue nuclei is due to epitope masking. J Mol Histol. 2005;36:337–44. doi: 10.1007/s10735-005-9004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bakay M, Wang Z, Melcon G, Schiltz L, Xuan J, Zhao P, et al. Nuclear envelope dystrophies show a transcriptional fingerprint suggesting disruption of Rb-MyoD pathways in muscle regeneration. Brain. 2006;129:996–1013. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taylor MR, Slavov D, Gajewski A, Vlcek S, Ku L, Fain PR, et al. Familial Cardiomyopathy Registry Research Group Thymopoietin (lamina-associated polypeptide 2) gene mutation associated with dilated cardiomyopathy. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:566–74. doi: 10.1002/humu.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ellis JA, Craxton M, Yates JR, Kendrick-Jones J. Aberrant intracellular targeting and cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of emerin contribute to the Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy phenotype. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:781–92. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.6.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Östlund C, Ellenberg J, Hallberg E, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Worman HJ. Intracellular trafficking of emerin, the Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy protein. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:1709–19. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.11.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stefanovic S, Hegde RS. Identification of a targeting factor for posttranslational membrane protein insertion into the ER. Cell. 2007;128:1147–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Denic V. A portrait of the GET pathway as a surprisingly complicated young man. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:411–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Östlund C, Sullivan T, Stewart CL, Worman HJ. Dependence of diffusional mobility of integral inner nuclear membrane proteins on A-type lamins. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1374–82. doi: 10.1021/bi052156n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Holmer L, Worman HJ. Inner nuclear membrane proteins: functions and targeting. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:1741–7. doi: 10.1007/PL00000813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zuleger N, Kelly DA, Richardson AC, Kerr AR, Goldberg MW, Goryachev AB, et al. System analysis shows distinct mechanisms and common principles of nuclear envelope protein dynamics. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:109–23. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.King MC, Lusk CP, Blobel G. Karyopherin-mediated import of integral inner nuclear membrane proteins. Nature. 2006;442:1003–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brown CA, Scharner J, Felice K, Meriggioli MN, Tarnopolsky M, Bower M, et al. Novel and recurrent EMD mutations in patients with Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, identify exon 2 as a mutation hot spot. J Hum Genet. 2011;56:589–94. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fairley EA, Kendrick-Jones J, Ellis JA. The Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy phenotype arises from aberrant targeting and binding of emerin at the inner nuclear membrane. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2571–82. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.15.2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tsuchiya Y, Hase A, Ogawa M, Yorifuji H, Arahata K. Distinct regions specify the nuclear membrane targeting of emerin, the responsible protein for Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Eur J Biochem. 1999;259:859–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sullivan T, Escalante-Alcalde D, Bhatt H, Anver M, Bhat N, Nagashima K, et al. Loss of A-type lamin expression compromises nuclear envelope integrity leading to muscular dystrophy. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:913–20. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Holaska JM, Wilson KL, Mansharamani M. The nuclear envelope, lamins and nuclear assembly. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:357–64. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(02)00329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yorifuji H, Tadano Y, Tsuchiya Y, Ogawa M, Goto K, Umetani A, et al. Emerin, deficiency of which causes Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, is localized at the inner nuclear membrane. Neurogenetics. 1997;1:135–40. doi: 10.1007/s100480050020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lattanzi G, Ognibene A, Sabatelli P, Capanni C, Toniolo D, Columbaro M, et al. Emerin expression at the early stages of myogenic differentiation. Differentiation. 2000;66:208–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2000.660407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Manta P, Terzis G, Papadimitriou C, Kontou C, Vassilopoulos D. Emerin expression in tubular aggregates. Acta Neuropathol. 2004;107:546–52. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0851-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Salpingidou G, Smertenko A, Hausmanowa-Petrucewicz I, Hussey PJ, Hutchison CJ. A novel role for the nuclear membrane protein emerin in association of the centrosome to the outer nuclear membrane. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:897–904. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cartegni L, di Barletta MR, Barresi R, Squarzoni S, Sabatelli P, Maraldi N, et al. Heart-specific localization of emerin: new insights into Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:2257–64. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.13.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Manilal S, Sewry CA, Pereboev A, Man N, Gobbi P, Hawkes S, et al. Distribution of emerin and lamins in the heart and implications for Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:353–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wheeler MA, Warley A, Roberts RG, Ehler E, Ellis JA. Identification of an emerin-beta-catenin complex in the heart important for intercalated disc architecture and beta-catenin localisation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:781–96. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0219-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Boggetti B, Niessen CM. Adherens junctions in Mammalian development, homeostasis and disease: lessons from mice. Subcell Biochem. 2012;60:321–55. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-4186-7_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ooshio T, Irie K, Morimoto K, Fukuhara A, Imai T, Takai Y. Involvement of LMO7 in the association of two cell-cell adhesion molecules, nectin and E-cadherin, through afadin and alpha-actinin in epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31365–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401957200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bengtsson L, Wilson KL. Multiple and surprising new functions for emerin, a nuclear membrane protein. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:73–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Morris GE, Manilal S. Heart to heart: from nuclear proteins to Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1847–51. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.10.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Holaska JM, Wilson KL. An emerin “proteome”: purification of distinct emerin-containing complexes from HeLa cells suggests molecular basis for diverse roles including gene regulation, mRNA splicing, signaling, mechanosensing, and nuclear architecture. Biochemistry. 2007;46:8897–908. doi: 10.1021/bi602636m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mislow JM, Holaska JM, Kim MS, Lee KK, Segura-Totten M, Wilson KL, et al. Nesprin-1alpha self-associates and binds directly to emerin and lamin A in vitro. FEBS Lett. 2002;525:135–40. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Haque F, Mazzeo D, Patel JT, Smallwood DT, Ellis JA, Shanahan CM, et al. Mammalian SUN protein interaction networks at the inner nuclear membrane and their role in laminopathy disease processes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3487–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.071910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Holaska JM, Kowalski AK, Wilson KL. Emerin caps the pointed end of actin filaments: evidence for an actin cortical network at the nuclear inner membrane. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Markiewicz E, Tilgner K, Barker N, van de Wetering M, Clevers H, Dorobek M, et al. The inner nuclear membrane protein emerin regulates beta-catenin activity by restricting its accumulation in the nucleus. EMBO J. 2006;25:3275–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Holaska JM, Rais-Bahrami S, Wilson KL. Lmo7 is an emerin-binding protein that regulates the transcription of emerin and many other muscle-relevant genes. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:3459–72. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dechat T, Pfleghaar K, Sengupta K, Shimi T, Shumaker DK, Solimando L, et al. Nuclear lamins: major factors in the structural organization and function of the nucleus and chromatin. Genes Dev. 2008;22:832–53. doi: 10.1101/gad.1652708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brachner A, Reipert S, Foisner R, Gotzmann J. LEM2 is a novel MAN1-related inner nuclear membrane protein associated with A-type lamins. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5797–810. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Simon DN, Wilson KL. Partners and post-translational modifications of nuclear lamins. Chromosoma. 2013;122:13–31. doi: 10.1007/s00412-013-0399-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Worman HJ. Nuclear lamins and laminopathies. J Pathol. 2012;226:316–25. doi: 10.1002/path.2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Segura-Totten M, Wilson KL. BAF: roles in chromatin, nuclear structure and retrovirus integration. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:261–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Puente XS, Quesada V, Osorio FG, Cabanillas R, Cadiñanos J, Fraile JM, et al. Exome sequencing and functional analysis identifies BANF1 mutation as the cause of a hereditary progeroid syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:650–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cabanillas R, Cadiñanos J, Villameytide JA, Pérez M, Longo J, Richard JM, et al. Néstor-Guillermo progeria syndrome: a novel premature aging condition with early onset and chronic development caused by BANF1 mutations. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:2617–25. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Merideth MA, Gordon LB, Clauss S, Sachdev V, Smith AC, Perry MB, et al. Phenotype and course of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:592–604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Montes de Oca R, Lee KK, Wilson KL. Binding of barrier to autointegration factor (BAF) to histone H3 and selected linker histones including H1.1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42252–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509917200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Skoko D, Li M, Huang Y, Mizuuchi M, Cai M, Bradley CM, et al. Barrier-to-autointegration factor (BAF) condenses DNA by looping. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16610–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909077106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Montes de Oca R, Andreassen PR, Wilson KL. Barrier-to-Autointegration Factor influences specific histone modifications. Nucleus. 2011;2:580–90. doi: 10.4161/nucl.2.6.17960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shumaker DK, Lee KK, Tanhehco YC, Craigie R, Wilson KL. LAP2 binds to BAF.DNA complexes: requirement for the LEM domain and modulation by variable regions. EMBO J. 2001;20:1754–64. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]