Abstract

Immunoisolation refers to an immunological strategy in which nonself antigens present on an allograft or xenograft are not allowed to come in contact with the host immune system, and it is implemented to prevent allorecognition and avoid immunosuppression. In this setting, the two most promising technologies, encapsulation of pancreatic islets (EPI) and immunocloaking (IC), are used. In the case of EPI, islets are inserted in capsules that, allow exchange of oxygen, nutrients and other molecules. In the case of IC, a natural nanofilm is injected prior to renal transplantation within the vasculature of the graft with the intent to pave the inner surface of the vascular lumen and camouflage the antigens located on the membrane of endothelia cells. Significant progress achieved in experimental models is leading EPI and IC to clinical translation.

Keywords: immunocloaking, immunoisolation, islet encapsulation, regenerative medicine

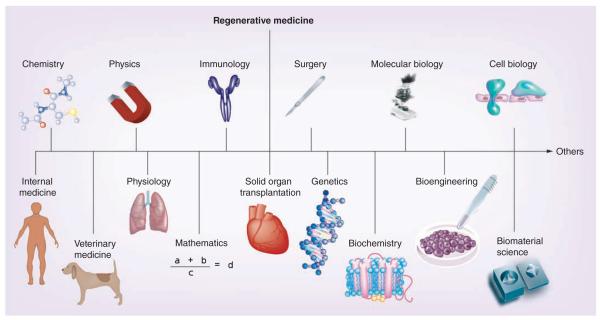

The aim of the present review is to briefly illustrate two biomaterial-based technologies that are currently being developed in organ transplantation, namely encapsulation of pancreatic islets (EPI) and immunocloaking (IC). They both aim to achieve the isolation of nonself antigens expressed by the cellular compartment of grafts genetically different to the recipient, from the host immune system. These donors may belong to the same species, as well as to different species, thus opening the door to xenotransplantation. Importantly, as biomaterial science comes under the umbrella of regenerative medicine (Figure 1), EPI and IC can be referred to as two different regenerative medicine-based strategies aiming to modulate the host immune response [1–4].

Figure 1.

The regenerative medicine umbrella highlighting the multidisciplinary nature of this field.

Organ transplantation as a halfway technology

Solid organ transplantation is one of the greatest achievements in the history of modern medicine, yet it should be referred to as a halfway technology. Introduced by Thomas [5], the concept of halfway technology as applied to the medical field indicates those treatments aiming at alleviating problematic symptoms instead of the root causes of a specific clinical condition. Such treatments are generally implemented when the disease is in advanced stages and possibly life threatening [6], with the intent to manage a disease but without offering any definitive cure [7]. A paradigmatic example is liver transplantation performed for hepatitis C-related cirrhosis. The surgical operation certainly improves the patient’s condition but does not eradicate the virus, which will reinfect the graft immediately after the transplant. The onset of signs of infection and disease recurrence is just a matter of time and progression to cirrhosis and allograft failure requiring retransplantation occurs in 20–30% and 10% of cases, respectively, after 5–10 years from the operation [8].

Overall, when compared with normal individuals, transplant patients experience a significantly lower life expectancy and quality of life, where main culprits are the nonavailability of a definite cure (in most cases) to eradicate the baseline disease and the chronic toxicity deriving from lifelong immunosuppression [9,10]. While the former aspect requires a more thorough understanding of the mechanisms of disease, the latter issue has justified the pursuit – since the early days of the transplant era – of an immunosuppression-free status after organ transplantation, defined as the condition when a transplant recipient retains stable graft function and lacks histological signs of rejection after having been without any immunosuppression for at least 1 year [4,9,10]. The patient in question has received a graft from a genetically different donor and is an otherwise immunocompetent host capable of responding to other immune challenges, including infections or transplantation of organs from third-party donors. Traditionally, this condition has been referred to as clinical operational tolerance. Unfortunately, such immunosuppression-free state is extremely difficult to achieve, is organ dependent and cannot be achieved immediately after the transplant (rather, only several months afterward). Importantly, as the different strategies that have been implemented so far to produce an immunosuppression-free state are burdened by an unacceptable lack of safety and efficacy, as a corollary such tolerogenic strategies cannot be encouraged in routine clinical practice but should be limited to clinical trials to be carried out in experienced centers.

EPI and IC are relatively new technologies that aim to allow transplantation of nonautologous tissues and organs without the need of any immunosuppression at any time after the transplant.

Encapsulation of pancreatic islets

EPI prior to transplantation was conceived more than half a century ago as a strategy to obviate the need for immuno-suppression of transplant recipients and to expand the donor pool [11–14]. However, it was only three decades ago that EPI become popular, after Lim and Sun reported that implantation of microencapsulated islets into diabetic rats was able to restore euglycemia [15]. Since that report, EPI technology has progressed significantly and advanced into the stage of clinical trials. Some of these pilot clinical trials have shown the ability of implanted EPI to reduce exogenous insulin requirements and decrease the occurrence of hyperglycemic episodes [16,17]. However, EPI remains as an experimental therapy because clinical trials have not yet been able to establish long-term insulin independence, but it holds the promise to become a valuable alternative to whole-pancreas transplantation once some major hurdles are overcome. Among these hurdles is the necessity to implant large numbers of islets in order to overcome the loss of islet functionality due to hypoxia [11–24]. EPI is also referred to as bioartificial pancreas.

To transplant cells or islets without any immunosuppression, requires a protective coating (semipermeable) to preserve their viability and function while overcoming rejection from the host immune system. This coating is provided by either larger devices that contain several islets each via macro-encapsulation or through small capsules containing one to two islets each via micro-encapsulation. Each system prevents allorecognition through the isolation of islets from the host environment. Macro-encapsulation systems are either extravascular or intravascular. Intravascular systems are similar to dialysis cartridges, and islets are seeded within the protected tubes and are then perfused by blood flow [25]. Extravascular devices are safer and have several different designs including both membrane and hollow fibers [26]. While there are many examples of macro-encapsulation devices that utilize immunoisolation for EPI, the authors have chosen to focus this review on micro-encapsulation, which provides a larger surface area per islet allowing for better diffusion of oxygen and nutrients thus improving islet cell quality. The biomaterials used to manufacture such capsules or devices are required to be biocompatible, permeable to nutrients and oxygen, as well as to hormones.

Biomaterials to manufacture capsules

Hydrogels are very attractive for making microcapsules, since they provide high permeability for low-molecular-weight nutrients and metabolites. Moreover, the soft and pliable features of the hydrogel reduce the mechanical or frictional irritations to surrounding tissue [27].

The most commonly applied materials for micro-encapsulation are alginate [15], chitosan [28], agarose [29], cellulose [30], poly(hydroxyethylmetacrylate-methyl methacrylate) [31], copolymers of acrylonitrile [32] and polyethylene glycol [33]. However, alginate is currently considered the gold standard for capsule manufacturing, as it provides some major advantages over other systems. For example, alginate molecules are linear block copolymers of β-d-mannuronic (M) and α-l-guluronic acids (G) and are able to form a gel in the presence of divalent ions such as Ca2+ and Ba2+ at physiological conditions. Recent findings have shown that divalent ions crosslink not only G blocks but also blocks of alternating M and G (M–G blocks) [34]. Mainly calcium is used for gelling, as barium is known to be toxic and concerns have been raised about patients’ safety if it is used as the crosslinking agent; however, recent findings indicate that microbeads made with high G alginate gelled with both calcium and barium ions reduce the risk of barium accumulation [35]. The encapsulation can be done at room or body temperature, at physiological pH and in isotonic solutions. Alginate-based capsules have been shown to be stable for years in both animals and human [36]. In addition, since alginates are negatively charged, the attachment of immune cells to the microcapsule is limited due to the negative charge on the cell surface.

Usually the formed beads are postcoated with a cationic poly(amino acid), for example, poly-l-Lysine (PLL) or poly-l-ornithine (PLO), to provide perm selectivity and improve capsule integrity [37]. This is followed by a surface coating of low-viscosity alginate, resulting in a microcapsule morphology that presents encapsulated cells in a sol layer of alginate, followed by PLL/PLO coating and gel layer of alginate on exterior, thus creating an alginate-PLL/PLO-alginate construct known as alginate/poly-L-lysine/alginate microcapsules.

Micro-encapsulation

In most tissues, it has been shown that maximum diffusion distance for effective oxygen and nutrient diffusion from blood capillary to cells is approximately 200 μm. Absence of this convection inside a capsule induces a nutrient gradient from the capsule surface to center of cells. Present insights suggest microcapsules as a preferable system over macrocapsules due to their high surface-to-volume ratio for fast exchange of hormones and nutrients. Micro-encapsulation uses the interfacial precipitation predominantly, where a polyanionic polymer (alginate) gels out with a divalent cation (Ca2+, Ba2+). Cells are suspended in an alginate solution, and its droplets are generated by air jet spray method [38], electrostatic generators [39,40], submerged oscillating coaxial extrusion nozzles [41], conformal coatings [42] and spinning disk atomization [43].

Of these methods, the air jet spray method, which uses a two-channel air droplet micro-encapsulator, is the most commonly used. Two-channel air droplet micro-encapsulators operate by allowing the alginate cell suspension to drip through an inner channel of the device, while the outer channel uses an air jacket to shear off the alginate droplet. Using this method, the diameters of the inner and outer channels, the flow rate of the alginate and air pressure of the outer channel can be adjusted to vary the microcapsule size [44]. In order to prevent hypoxic damage to cells, micro-encapsulation must be done relatively quickly around 4°C.

A reduction in capsule size would benefit the cells and also exponentially decrease the total transplant volume. Therefore, much work has been done with various new technologies to make beads as small as 185 μm (diameter), which is about four-times smaller than conventional beads (800 μm). The smaller the diameter of the capsules, the better the diffusion of nutrients to the cells, and Omer et al. demonstrated that capsules with a diameter of 600 ± 100 μm showed improved stability in vivo over larger capsules with diameters of 1000 ± 100 μm [45]. Although great care should be taken since any exposed islet at the surface of such small microcapsules shall result in an immune reaction.

Immune barrier

Uncoated nonpermeable-selective alginate microbeads have been reported to have a high permeability (>600 kD). Uptake studies with IgG (150 kD) and thyroglobulin (669 kD) suggested they were able to penetrate these uncoated microbeads. Similarly, uncoated alginate microbeads implanted in peritoneum were positive for both IgG and C3 component after only 1 week; while this is not an indication that these materials are damaging to islets, this indicates that they are directly interacting with the transplanted tissue [46]. So, small molecules from macrophages and T cells to smaller cytokine molecules such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ can easily penetrate into the microcapsules and can damage or destroy the encapsulated islets [47]. To obviate this problem, a permeability barrier between the encapsulated cells and the host immune system has been developed. A polyamino acid layer, followed by an additional outer coating of alginate, has been used for this purpose. The positively charged polyamino molecules readily bind to the negatively charged alginate molecules forming a complex membrane [48,49], which significantly reduces the pore size of the microcapsule and prevents immune cells from entering the microcapsule [40,50]. In order to prevent interactions of nonbound polyamines to host tissue, a thin second layer of alginate is added. This polyamino barrier acts as a shell, providing mechanical stability to the microcapsule, allowing for the liquefaction of the inner alginate with sodium citrate solution [51]. The thickness of this barrier can be varied through incubation time and concentration [52].

The most researched permeable-selective biomaterial is PLL, which was the first material used to generate this barrier; however, more recent research has shown that PLO had markedly reduced immune response and has shown to provide more mechanical support to the microcapsules [53]. Since the introduction of the concept of micro-encapsulation of cells, PLL has been routinely used as the selectively permeable membrane for microcapsules. It makes xenotransplantation of cells a feasible option and provides mechanical stability features required for application in large animals and human. After gelation of the beads in calcium, the beads are suspended in polycation solutions such as PLL, which increases membrane integrity via electrostatic association with the anionic alginate. However, unbound PLL has been shown to cause an inflammatory response and result in fibrotic over growth over microcapsules [54,55]. Even in capsule systems that use an outer alginate core, PLL is still present to some extent on the surface of the capsules. This could increase the chance of triggering an inflammatory reaction and fibrotic overgrowth [46,55,56]. In addition, atomic force microscopy indicated that these capsules had an increased surface roughness due to the PLL molecules that is not desired due to increased surrounding tissue irritation [57].

An alternative to PLL is PLO. Like PLL, PLO is a positively charged polyamine which, when applied to alginate microcapsules, forms a semipermeable membrane that significantly reduces the porosity of the microcapsules, allowing for immunoisolation without impairing oxygen and nutrient diffusion. Unlike PLL, PLO has been shown to evoke less of an immune response and has been shown to have improved mechanical properties [21,58–60]. When compared with alginate-PLL microcapsules, alginate-PLO microcapsules have been shown to better resist swelling and bursting under osmotic stress [53]. Bead swelling is an important factor to take into consideration because it can lead to increases in pore size, permeability and shear stress, which leads to decreased islet viability [52,61]. It has been hypothesized that the improved mechanical properties of alginate-PLO microcapsules over alginate-PLL microcapsules is due to the improved bonding of PLO to alginate due to the shorter monomer structure of PLO [60,62]. In addition, while PLL seems to bind to M–G sequences, PLO has been shown to prefer M–M sequences [63]. While there is not yet a consensus on which polyamino coating is superior [64], long-term studies where empty alginate-PLO microcapsules were injected intraperitoneally in rodents, dogs or pigs have always resulted in retrieval of intact and overgrowth-free microcapsules up to 1 year postimplant [65].

Site of implantation

Another critical aspect of EPI implantation is the implantation site. In order for long-term survival, EPI must be implanted close to the blood stream in order to receive sufficient oxygen. However, the size of the EPI makes it difficult to place large numbers of microcapsules all within close proximity to a blood source. Currently, the most common site of implantation is intraperitoneally, since EPI can be implanted through injection or laparoscopic implantation [16,17]. However, implanting EPI directly into the peritoneal cavity limits the control of the placement of the capsules that can result in placing capsules away from blood sources resulting in a delay in insulin uptake and a reduction in the oxygen available to islets. In addition, EPI placed intraperitoneally have been shown to be more vulnerable to an immune response [20]. As a result of these limitations with intraperitoneal implantation, several alternative sites have been investigated including subcutaneous, kidney capsule, liver and omentum pouch implantation sites [66–71]. The omentum pouch has offered several advantages, including well-vascularized sites that can accommodate a large number of EPI [69].

Immunocloaking

IC is a cutting-edge technology consisting of the application of a bioengineered nanofilm termed NB-LVF4 on the luminal surface of blood vessels in order to hide endothelium antigens and prevent allorecognition by the host immune system [3,72–74]. This nanofilm is obtained from the basement membrane of cultured corneal endothelial cells and consists of corneal endothelial cell proteins including type IV collagen, vitrogen, fibronectin and laminin. These components are then injected through the arterial line of the graft immediately prior to implantation creating a 3D, transparent 200-nm thick membrane, which then interacts with the graft’s endothelial cells. Such interactions are mediated by specific domains represented by the laminin and fibronectin portions of the membrane, which are recognized by receptors present on the membrane of endothelial cells and will result in the creation of a physical barrier, thus preventing the detection of alloantigens by the host immune system. Importantly, NB-LVF4 is nonthrombogenic and deters immune-cell migration, while still allowing permeable small compounds, such as nutrients and oxygen, to easily diffuse across the barrier. In addition, nanofilm-treated tissue is able to maintain similar functionality as untreated tissue. Preliminary feasibility investigations of IC technology have been conducted in renal and skin allograft models in dogs and mice, respectively.

Canine renal allograft model

In the first study by Brasile et al., time of onset of acute rejection was investigated in eight foxhounds who received renal allografts [73]. Initially, there were three separate in vitro steps to this study and in each step, the stimulation index (SI) was quantitated in mixed leukocyte lymphocyte culture to determine cellular compatibility within transplantation. A SI of less than 5.0 constituted a negative result while a SI of greater than 5.0 was considered a positive response. The investigators first used canine mononuclear cells alone as a negative control. Next, they utilized a combination of canine mononuclear cell with allogenic vascular endothelial cells (VEC) to represent the positive control. The SI for the positive control was 49.8, which evidenced the fact that the canine lymphocytes proliferated when stimulated by VEC. Subsequently, canine mononuclear cells were mixed with NB-LVF4-treated allogenic VEC, and lymphocyte proliferation was virtually nullified with 99.98% inhibition and an SI of only 1.1. Last, the canine lymphocytes had NB-LVF4 added alone without VEC, and the SI was found to be 0.7. The aforementioned results demonstrated that NB-LVF4 was not immunogenic and did not induce an intrinsic proliferative response. More importantly, this showed that NB-LVF4 was capable of producing an IC effect.

Experiments went on to show that NB-LVF4 was able to provide over 90% coverage of luminal surfaces of renal vasculature, irrespective of caliber. NB-LVF4 was applied for 3 h ex vivo at 37°C in four separate renal nephrectomies and then autotransplanted back into the foxhound. Immunohistochemical stains showed that there were no areas of occlusion in the renal vessels during the 3 h ex vivo period of warm perfusion. After demonstrating that the nanofilm could provide sufficient IC in renal vasculature, the experimenters went on to show that NB-LVF4 did not adversely affect renal function. In all cases, serum creatinine remained stable after transplant, and serum chemistries and hematologic parameters were within normal limits 7 days postoperatively.

Once IC with NB-LVF4 was shown to be efficacious in renal autotransplants, it was attempted in an allograft. Four foxhounds were allotransplanted with native kidney nephrectomy treated with NB-LVF4 (study group), and four were allotransplanted with native kidney nephrectomy not treated with NB-LVF4 (control group). None of the foxhounds were given immunosuppression postoperatively. Using creatinine as a surrogate marker of kidney function, it was found that untreated subjects had a mean onset of rejection on day 6 as opposed to subjects treated with NB-LVF4 who had a mean onset of rejection on day 30. Moreover, the nanofilm neither did occlude the vascular tree at any level nor did it result in deteriorated renal function.

Rodent skin allograft model

Unlike renal allografts, skin allografts have been notorious for short graft survival times due to rejection. Semisynthetic skin equivalents and skin autografts have been the mainstays of treatment for skin loss due to the profound immunologic rejection of skin allografts. Encouragingly, similar striking results seen in the canine renal allograft study were obtained in models of skin allotransplantation in mice [72,74]. Initially, the immunogenicity of NB-LVF4 was tested in vitro by determining the immune response of allogenic peripheral blood mononuclear cells to VECs treated with the nanofilm. The immune response was inhibited by 98.1% in vitro when the nanofilm coated the VECs. Thus, NB-LVF4 coating provides an IC effect.

In the study groups, full-thickness 8 mm skin grafts were cross-transplanted between two genetically unrelated groups of mice (BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice) and sutured in place. BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice possess major H-2 complex incompatibilities, providing a great model for skin allograft transplantation. In one study group, the subdermal surface of the skin grafts was carefully layered with the nanofilm using a sterile syringe and allowed to mature in an incubator at 37°C for 15 min. The nanofilm was applied to the entire subdermal surface of the graft unlike the canine study involving application of NB-LVF4 solely to the endothelial surface of graft vasculature. During the incubation period, an additional 100 μl of the nanofilm was deposited onto the wound bed on each mouse. The treated skin grafts were then allotransplanted onto the coated wound bed. Rejection occurred after a mean time of 28 days, versus 7 days in the control group (no nanofilm). Rejection was defined as graft necrosis >90%. On flow cytometric analysis, the shift in the number of CD4+ cells was reduced in the NB-LVF4 group versus the control group (i.e., fourfold increase in CD4+ cells versus tenfold increase in CD4+ cells, respectively).

In a second study group, FGF-1 was included with the NB-LVF4 before application. FGF-1 is a wound hormone involved in many signaling cascades including those that have angiogenic characteristics, stimulate DNA synthesis, regulate cell growth and inhibit apoptosis. In the present study, FGF-1 theoretically reduced inflammation in the skin graft, and the time the skin allograft is dependent on plasmatic circulation. FGF-1 prevented B-cell ability to produce donor-specific antibodies by interfering with B-cell activation. No donor-specific antibody was detected in grafts treated with FGF-1 with NB-LVF4. In control allografts and grafts treated with NB-LVF4 alone, donor-reactive antibody was detected on day 14 and day 45 post-transplant, respectively. In vitro, exposure of naive B cells to FGF-1 prior to stimulation from allogenic VECs resulted in a 92% inhibition of B-cell activation. B-cell activation was determined by CD25 expression, a protein expressed on activated B cells. CD20+ and CD25+ B cells have been shown to increase levels of immunoglobulins and serve as memory cells that boost the immune response. Presumably, FGF-1 prevented the humoral response to the skin graft by inhibiting B-cell activation. These results provide evidence that the nanobarrier membrane may serve as a targeted drug delivery system to promote immunogenicity of skin allografts.

The addition of FGF-1 to NB-LVF4 represents an initial idea that needs to be expanded on. Adding a variety of compounds to NB-LVF4 prior to polymerization provides opportunity to enhance outcomes. Although FGF-1 with NB-LVF4 did not enhance allograft survival as compared with NB-LVF4 alone, the principle is proven feasible and should be explored further. Likewise, the nature of NB-LVF4 over time must be further elucidated to determine the protective mechanism of the nanobarrier longitudinally over time.

When assessed in totality, the aforementioned studies were groundbreaking as they showed that nanofilms can be used in an animal model to delay the onset of rejection without the use of immunosuppression. A significant barrier that may need to be overcome is the use of nanofilms under conditions of cold perfusion. Routinely, kidneys are prepared under cold perfusion to decrease cell metabolism and hence lessen the accumulation of toxic metabolites. However, this has also meant that application of NB-LVF4 to the luminal vessel in cold conditions is quite difficult due to the significant inhibition of cellular activity.

Importantly, one of the largest limitations of this technology is the necessity for additional tolerogenic regimens. NB-LVF4 itself is not tolerogenic; rather, it provides a 30-day window during which tolerogenic regimens should be administered to allow engraftment and minimize or eliminate the need for immunosuppression. Tolerogenic regimens are given to deplete the cellular compartment of the immune system responsible for allorecognition thereby severely impairing the barriers of the immune system. Meanwhile, graft endothelium-located nonself-antigens are exposed, and donor-derived immunomodulatory hematopoietic cells are administered to induce a degree of chimerism. Thus, the rationale for the use of the nanofilm in question is that camouflage of the aforementioned antigens will ensure that the effector cells of the immune response remain inert for approximately 30 days. Consequently, when the cellular compartment of the host immune system is reconstituted, interactions with donor hematopoietic cells should theoretically minimize the requirement for immunosuppression and build a tolerogenic environment. However, further studies are needed to validate this hypothesis.

The investigators used a very systematic and methodical research design that provided credence to their data. While more studies are needed to further investigate the phenomenon of IC, the preliminary results are very promising and foreshadow the advent of a new age in the field of transplantation.

Expert commentary & five-year view

Immunoisolation represents a potentially valuable alternative to classic immunomodulation. In the case of EPI, encapsulation technology has the potential to allow cell transplantation across species without any immunosuppression. In doing so, it may meet the two major needs of organ transplantation, namely, the achievement of an immunosuppression-free state and the identification of a potentially inexhaustible source of organs. Progress in biomaterial science and the understanding of experimental pathophysiology of EPI, is paving the way to success. It is currently possible to insert more islets into smaller microcapsule sizes. Importantly, the widely adopted purified alginate polymers seem to be the gold standard in reason of their biocompatibility and high efficacy.

In the case of IC, it will be critical to define the most appropriate immunological strategy to adopt during the 4-week window before the nanofilm is degraded. From a transplant immunology perspective, this window is extremely long and justifies the attempt of numerous strategies aiming to either produce an immunosuppression-free state or a significant minimization of the total immunosuppression.

Key issues.

The term immunoisolation refers to a biomaterial (regenerative medicine)-based approach to preventing allorecognition consisting of the isolation of nonself-antigens from the surrounding environment. Such isolation can be obtained by either inserting cells alone or in a cluster (for instance, pancreatic islets) within capsules impermeable to immune cells and antibodies (encapsulation of pancreatic islets) or applying a nanofilm that will camouflage the antigens themselves, so rendering them undetectable to the immune system effectors (immunocloaking).

Biomaterial is defined as a “substance that has been engineered to take a form which, alone or as part of a complex system, is used to direct, by control of interactions with components of living systems, the course of any therapeutic or diagnostic procedure” [101].

Halfway technology refers to a treatment implemented when a disease is life threatening without offering a definitive cure. Organ transplantation is an example of halfway technology because, in most cases, it does not clear the baseline disease which instead will recur in the new organ. Moreover, lifelong antirejection therapy is burdened by severe toxicity that tremendously affects on patient mortality and morbidity.

Encapsulation of pancreatic islets is a technology in which xeno- or allo-pancreatic islets are inserted in capsules. A semipermeable membrane is used to protect islets from mechanical stress and the recipient’s immune system, while allowing bidirectional diffusion of nutrients, oxygen, glucose, hormones and wastes. This technology is also referred to as bioartificial pancreas.

Immunocloaking is a technology in which a natural nanofilm is injected within the vasculature of solid organs. The nanofilm will pave the inner surface of the lumen in order to allow attachment of the components of the nanofilm to nonself-antigens present on endothelia cells. The ultimate goal is to prevent allorecognition.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest

•• of considerable interest

- 1.Orlando G, Bendala JD, Shupe T, et al. Cell and organ bioengineering technology as applied to gastrointestinal diseases. Gut. 2012 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301111. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301111. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orlando G. Transplantation as a subfield of regenerative medicine. Interview by Lauren Constable. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2011;7(2):137–141. doi: 10.1586/eci.10.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orlando G. Immunosuppression-free transplantation reconsidered from a regenerative medicine perspective. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2012;8(2):179–187. doi: 10.1586/eci.11.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orlando G, Wood KJ, Soker S, Stratta RJ. How regenerative medicine may contribute to the achievement of an immunosuppression-free state. Transplantation. 2011;92(8):e36–e38. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31822f59d8. author reply e39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas L. The technology of medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 1971;285(24):1366–1368. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197112092852411. •• Seminal paper in which Thomas first introduced the concept of halfway technology as referred to therapies aiming to alleviating problematic symptoms instead of the root causes of a specific clinical condition.

- 6.Oliver TR. Health care reform as a halfway technology. J. Health Polit. Policy Law. 2011;36(3):603–609. doi: 10.1215/03616878-1271333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas L. Lives of a Cell. Viking Press; New York, NY, USA: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubín A, Aguilera V, Berenguer M. Liver transplantation and hepatitis C. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2011;35(12):805–812. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orlando G, Hematti P, Stratta RJ, et al. Clinical operational tolerance after renal transplantation: current status and future challenges. Ann. Surg. 2010;252(6):915–928. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f3efb0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orlando G, Soker S, Wood K. Operational tolerance after liver transplantation. J. Hepatol. 2009;50(6):1247–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Opara EC, Mirmalek-Sani SH, Khanna O, Moya ML, Brey EM. Design of a bioartificial pancreas(+) J. Investig. Med. 2010;58(7):831–837. doi: 10.231/JIM.0b013e3181ed3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill RS, Cruise GM, Hager SR, et al. Immunoisolation of adult porcine islets for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. The use of photopolymerizable polyethylene glycol in the conformal coating of mass-isolated porcine islets. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1997;831:332–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avgoustiniatos ES, Colton CK. Effect of external oxygen mass transfer resistances on viability of immunoisolated tissue. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1997;831:145–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Sullivan ES, Vegas A, Anderson DG, Weir GC. Islets transplanted in immunoisolation devices: a review of the progress and the challenges that remain. Endocr. Rev. 2011;32(6):827–844. doi: 10.1210/er.2010-0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim F, Sun AM. Microencapsulated islets as bioartificial endocrine pancreas. Science. 1980;210(4472):908–910. doi: 10.1126/science.6776628. •• Seminal paper reporting that single implantation of micro-encapsulated islets into rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes corrected the diabetic state for up to 3 weeks.

- 16.Calafiore R, Basta G, Luca G, et al. Microencapsulated pancreatic islet allografts into nonimmunosuppressed patients with type 1 diabetes: first two cases. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(1):137–138. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elliott RB, Escobar L, Tan PL, Muzina M, Zwain S, Buchanan C. Live encapsulated porcine islets from a type 1 diabetic patient 9.5 yr after xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2007;14(2):157–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2007.00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soon-Shiong P, Feldman E, Nelson R, et al. Successful reversal of spontaneous diabetes in dogs by intraperitoneal microencapsulated islets. Transplantation. 1992;54(5):769–774. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199211000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prokop A. Bioartificial pancreas: materials, devices, function, and limitations. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2001;3(3):431–449. doi: 10.1089/15209150152607213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Groot M, Schuurs TA, van Schilfgaarde R. Causes of limited survival of microencapsulated pancreatic islet grafts. J. Surg. Res. 2004;121(1):141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kizilel S, Garfinkel M, Opara E. The bioartificial pancreas: progress and challenges. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2005;7(6):968–985. doi: 10.1089/dia.2005.7.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pareta RA, McQuilling JP, Farney A, et al. Bioartificial pancreas: evaluation of crucial barriers to clinical application. In: Randhawa G, editor. Organ Donation and Transplantation – Public Policy and Clinical Perspectives. INTECH Publishers; Rijeka, Croatia: 2012. pp. 241–266. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smidsrød O, Skjåk-Braek G. Alginate as immobilization matrix for cells. Trends Biotechnol. 1990;8(3):71–78. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(90)90139-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holtan S, Zhang Q, Strand WI, Skjåk-Braek G. Characterization of the hydrolysis mechanism of polyalternating alginate in weak acid and assignment of the resulting MG-oligosaccharides by NMR spectroscopy and ESI-mass spectrometry. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7(7):2108–2121. doi: 10.1021/bm050984q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maki T, Lodge JP, Carretta M, et al. Treatment of severe diabetes mellitus for more than one year using a vascularized hybrid artificial pancreas. Transplantation. 1993;55(4):713–7. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199304000-00005. discussion 717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zekorn T, Horcher A, Siebers U, Federlin K, Bretzel RG. Islet transplantation in immunoseparating membranes for treatment of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 1995;103(Suppl. 2):136–139. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1211411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Vos P, Hamel AF, Tatarkiewicz K. Considerations for successful transplantation of encapsulated pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 2002;45(2):159–173. doi: 10.1007/s00125-001-0729-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zielinski BA, Aebischer P. Chitosan as a matrix for mammalian cell encapsulation. Biomaterials. 1994;15(13):1049–1056. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(94)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwata H, Amemiya H, Matsuda T, Takano H, Hayashi R, Akutsu T. Evaluation of microencapsulated islets in agarose gel as bioartificial pancreas by studies of hormone secretion in culture and by xenotransplantation. Diabetes. 1989;38(Suppl. 1):224–225. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.1.s224. • First report on the utilization of agarose gel as basic material for encapsulation of islets.

- 30.Risbud MV, Bhonde RR. Suitability of cellulose molecular dialysis membrane for bioartificial pancreas: in vitro biocompatibility studies. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001;54(3):436–444. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20010305)54:3<436::aid-jbm180>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dawson RM, Broughton RL, Stevenson WT, Sefton MV. Microencapsulation of CHO cells in a hydroxyethyl methacrylate-methyl methacrylate copolymer. Biomaterials. 1987;8(5):360–366. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(87)90006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler L, Pinget M, Aprahamian M, Dejardin P, Damgé C. In vitro and in vivo studies of the properties of an artificial membrane for pancreatic islet encapsulation. Horm. Metab. Res. 1991;23(7):312–317. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1003685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cruise GM, Hegre OD, Lamberti FV, et al. In vitro and in vivo performance of porcine islets encapsulated in interfacially photopolymerized poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate membranes. Cell Transplant. 1999;8(3):293–306. doi: 10.1177/096368979900800310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donati I, Holtan S, Mørch YA, Borgogna M, Dentini M, Skjåk-Braek G. New hypothesis on the role of alternating sequences in calcium-alginate gels. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6(2):1031–1040. doi: 10.1021/bm049306e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mørch YA, Qi M, Gundersen PO, et al. Binding and leakage of barium in alginate microbeads. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2012;100(11):2939–2947. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soon-Shiong P, Heintz RE, Merideth N, et al. Insulin independence in a Type 1 diabetic patient after encapsulated islet transplantation. Lancet. 1994;343(8903):950–951. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaikof EL. Engineering and material considerations in islet cell transplantation. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 1999;1:103–127. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.1.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolters GH, Fritschy WM, Gerrits D, van Schilfgaarde R. A versatile alginate droplet generator applicable for microencapsulation of pancreatic islets. J. Appl. Biomater. 1991;3(4):281–286. doi: 10.1002/jab.770030407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hallé JP, Leblond FA, Pariseau JF, Jutras P, Brabant MJ, Lepage Y. Studies on small (<300 microns) microcapsules: II–Parameters governing the production of alginate beads by high voltage electrostatic pulses. Cell Transplant. 1994;3(5):365–372. doi: 10.1177/096368979400300503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsu BR, Chen HC, Fu SH, Huang YY, Huang HS. The use of field effects to generate calcium alginate microspheres and its application in cell transplantation. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 1994;93(3):240–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dawson RM, Broughton RL, Stevenson WT, et al. Microencapsulation of CHO cells in a hydroxyethyl methacrylatemethyl methacrylate copolymer. Biomaterials. 1987;8:360–366. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(87)90006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Desmangles AI, Jordan O, Marquis-Weible F. Interfacial photopolymerization of β-cell clusters: approaches to reduce coating thickness using ionic and lipophilic dyes. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2001;72(6):634–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Senuma Y, Lowe C, Zweifel Y, Hilborn JG, Marison I. Alginate hydrogel microspheres and microcapsules prepared by spinning disk atomization. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2000;67(5):616–622. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(20000305)67:5<616::aid-bit12>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Omer A, Duvivier-Kali V, Fernandes J, Tchipashvili V, Colton CK, Weir GC. Long-term normoglycemia in rats receiving transplants with encapsulated islets. Transplantation. 2005;79(1):52–58. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000149340.37865.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lanza RP, Kühtreiber WM, Ecker D, Staruk JE, Chick WL. Xenotransplantation of porcine and bovine islets without immunosuppression using uncoated alginate microspheres. Transplantation. 1995;59(10):1377–1384. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199505270-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Schilfgaarde R, de Vos P. Factors influencing the properties and performance of microcapsules for immunoprotection of pancreatic islets. J. Mol. Med. 1999;77(1):199–205. doi: 10.1007/s001090050336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bystrický S, Malovíková A, et al. Interaction of alginates and pectins with cationic polypeptides. Carbohydrate Polymers. 1990;13(3):283–294. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thu B, Bruheim P, Espevik T, Smidsrød O, Soon-Shiong P, Skjåk-Braek G. Alginate polycation microcapsules. II. Some functional properties. Biomaterials. 1996;17(11):1069–1079. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)85907-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.King GA, Daugulis AJ, et al. Alginate-polylysine microcapsules of controlled membrane molecular weight cutoff for mammalian cell culture engineering. Biotech. Progress. 1987;3(4):231–240. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kulseng B, Thu B, Espevik T, Skjåk-Braek G. Alginate polylysine microcapsules as immune barrier: permeability of cytokines and immunoglobulins over the capsule membrane. Cell Transplant. 1997;6(4):387–394. doi: 10.1177/096368979700600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Darrabie M, Freeman BK, Kendall WF, Jr, Hobbs HA, Opara EC. Durability of sodium sulfate-treated polylysine-alginate microcapsules. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001;54(3):396–399. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20010305)54:3<396::aid-jbm120>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gugerli R, Cantana E, Heinzen C, von Stockar U, Marison IW. Quantitative study of the production and properties of alginate/poly-l-lysine microcapsules. J. Microencapsul. 2002;19(5):571–590. doi: 10.1080/02652040210140490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Darrabie MD, Kendall WF, Jr, Opara EC. Characteristics of Poly-l-Ornithine-coated alginate microcapsules. Biomaterials. 2005;26(34):6846–6852. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thu B, Bruheim P, Espevik T, Smidsrød O, Soon-Shiong P, Skjåk-Braek G. Alginate polycation microcapsules. I. Interaction between alginate and polycation. Biomaterials. 1996;17(10):1031–1040. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)84680-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Strand BL, Ryan TL, In’t Veld P, et al. Poly-l-Lysine induces fibrosis on alginate microcapsules via the induction of cytokines. Cell Transplant. 2001;10(3):263–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clayton HA, London NJ, Colloby PS, Bell PR, James RF. The effect of capsule composition on the biocompatibility of alginate-poly-l-lysine capsules. J. Microencapsul. 1991;8(2):221–233. doi: 10.3109/02652049109071490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bünger CM, Gerlach C, Freier T, et al. Biocompatibility and surface structure of chemically modified immunoisolating alginate-PLL capsules. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2003;67(4):1219–1227. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brunetti P, Basta G, Faloerni A, Calcinaro F, Pietropaolo M, Calafiore R. Immunoprotection of pancreatic islet grafts within artificial microcapsules. Int. J. Artif. Organs. 1991;14(12):789–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Calafiore R, Basta G, Boselli C, et al. Effects of alginate/polyaminoacidic coherent microcapsule transplantation in adult pigs. Transplant. Proc. 1997;29(4):2126–2127. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(97)00260-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Calafiore R, Basta G, Luca G, et al. Grafts of microencapsulated pancreatic islet cells for the therapy of diabetes mellitus in non-immunosuppressed animals. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2004;39(Pt. 2):159–164. doi: 10.1042/BA20030151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ching CD, Harland RC, Collins BH, Kendall W, Hobbs H, Opara EC. A reliable method for isolation of viable porcine islet cells. Arch. Surg. 2001;136(3):276–279. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Inaki Y, Tohnai N, Miyabayashi K, Miyata M. Isopoly-L-ornithine derivative as nucleic acid model. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1997;37:25–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Castro M, Orive G, Hernandex RM, et al. Comparitive study of microcapsules elaborated with three polycations (PLL, PDL, PLO) for cell immobilization. J. Microsurg. 2008;25(6):387–398. doi: 10.1080/026520405000099893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Toso C, Mathe Z, Morel P, et al. Effect of microcapsule composition and short-term immunosuppression on intraportal biocompatibility. Cell Transplant. 2005;14(2–3):159–167. doi: 10.3727/000000005783983223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dufrane D, Goebbels RM, Saliez A, Guiot Y, Gianello P. Six-month survival of microencapsulated pig islets and alginate biocompatibility in primates: proof of concept. Transplantation. 2006;81(9):1345–1353. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000208610.75997.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dufrane D, Steenberghe M, Goebbels RM, Saliez A, Guiot Y, Gianello P. The influence of implantation site on the biocompatibility and survival of alginate encapsulated pig islets in rats. Biomaterials. 2006;27(17):3201–3208. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.028. • Seminal paper providing evidence that the implantation site impact on the outcome of transplantation of encapsulated islets.

- 67.Kin T, Korbutt GS, Rajotte RV. Survival and metabolic function of syngeneic rat islet grafts transplanted in the omental pouch. Am. J. Transplant. 2003;3(3):281–285. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kobayashi T, Aomatsu Y, Iwata H, et al. Survival of microencapsulated islets at 400 days posttransplantation in the omental pouch of NOD mice. Cell Transplant. 2006;15(4):359–365. doi: 10.3727/000000006783981954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moya ML, Cheng MH, Huang JJ, et al. The effect of FGF-1 loaded alginate microbeads on neovascularization and adipogenesis in a vascular pedicle model of adipose tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31(10):2816–2826. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.12.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Calafiore R, Basta G, Luca G, et al. Microencapsulated pancreatic islet allografts into nonimmunosuppressed patients with Type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(1):137–138. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Vos P, Faas MM, Strand B, Calafiore R. Alginate-based microcapsules for immunoisolation of pancreatic islets. Biomaterials. 2006;27(32):5603–5617. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brasile L, Glowacki P, Stubenitsky BM. Bioengineered skin allografts: a new method to prevent humoral response. ASAIO J. 2011;57(3):239–243. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e3182155e52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brasile L, Glowacki P, Castracane J, Stubenitsky BM. Pretransplant kidney-specific treatment to eliminate the need for systemic immunosuppression. Transplantation. 2010;90(12):1294–1298. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ffba97. •• First report on the application of immunocloaking technology in a solid organ transplant model.

- 74.Stubenitsky BM, Brasile L, Rebellato LM, Hawinkels H, Haisch C, Kon M. Delayed skin allograft rejection following matrix membrane pretreatment. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2009;62(4):520–525. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.12.001. •• First report on the application of immunocloaking technology in a skin-graft model.

Website

- 101.Elsevier www.journals.elsevier.com/biomaterials/