Abstract

Background

The American Indian experience of historical trauma is thought of as both a source of intergenerational trauma responses as well as a potential causative factor for long-term distress and substance abuse among communities. The aims of the present study were to evaluate the extent to which the frequency of thoughts of historical loss and associated symptoms are influenced by: current traumatic events, post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), cultural identification, percent Native American Heritage, substance dependence, affective/anxiety disorders, and conduct disorder/antisocial personality disorder (ASPD).

Methods

Participants were American Indians recruited from reservations that were assessed with the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA), The Historical Loss Scale and The Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale (to quantify frequency of thoughts and symptoms of historical loss) the Stressful-Life-Events Scale (to assess experiences of trauma) and the Orthogonal Cultural Identification Scale (OCIS).

Results

Three hundred and six (306) American Indian adults participated in the study. Over half of them indicated that they thought about historical losses at least occasionally, and that it caused them distress. Logistic regression revealed that significant increases in how often a person thought about historical losses were associated with: not being married, high degrees of Native Heritage, and high cultural identification. Additionally, anxiety/affective disorders and substance dependence were correlated with historical loss associated symptoms.

Conclusions

In this American Indian community, thoughts about historical losses and their associated symptomatology are common and the presences of these thoughts are associated with Native American Heritage, cultural identification, and substance dependence.

Keywords: historical trauma, substance dependence, PTSD, American Indian

1. INTRODUCTION

Historical trauma is a term used to describe the intergenerational collective experience of complex trauma that was inflicted on a group of people who share a specific group identity or affiliation such as a nationality, religious affiliation or ethnicity (Evans-Campbell, 2008). The construct of historical trauma has been used as both a description of trauma responses among a particular group of individuals as well as a potential causative factor for long-term distress among communities (Evans-Campbell, 2008). Much of the early scholarship on historical trauma originated in the 1960s in an attempt to explain the collective distress described by some of the Jewish Holocaust survivors. The early studies called it “survivor syndrome” and suggested it included symptoms such as: denial, depersonalization, isolation, somatization, memory loss, agitation, anxiety, guilt, depression, intrusive thoughts, nightmares, psychic numbing and survivor guilt (Barocas,1975; Niederland,1968, 1981). In addition to the PTSD-like symptoms that the actual victims of the traumas experience, there has been data to suggest that the offspring of the victims of trauma may also suffer from PTSD-like symptoms by a process that is often referred to as “secondary”, “vicarious” or “intergenerational” trauma (Bergmann and Jucovy, 1990; Danieli,1998; Figley,1995; Motta et al., 1994; Rosenheck,1986; Rosenheck and Nathan,1985). This secondary response to the trauma by the next generation is thought to be part of the basis of the persistence of the effects of historical trauma.

Over the last 10 years, there has been much interest in conceptualizing the historical psychological distress among American Indian people in response to the history of genocide, ethnic cleansing, policies of forced acculturation, placement in boarding schools and loss of traditions, in a similar manner to that experienced by Jewish Holocaust victims. Descriptions of the construct of “historical trauma” as observed in American Indian communities has been described elegantly by several authors (Brave Heart, 1998; Brave Heart and DeBruyn, 1998; Braveheart-Jordan and DeBruyn, 1995; Denham, 2008; Evans-Campbell, 2008; Morgan and Freeman, 2009; Szlemko et al., 2006). Native Americans, in current times, also appear to experience a higher rate of traumatic events than has been reported in general population surveys (Beals et al., 2005a). Thus, as pointed out by Whitbeck and colleagues (2004a, 2004b), the losses experienced by American Indian people are not confined to a single catastrophic period but rather they are ongoing and present in their lives. Another additionally complicating factor is the current and historical use and abuse of alcohol and drugs among some Indian communities that may enhance risk for current trauma as well as the impact of historical trauma. Although use of alcohol varies among tribes, as a whole Native Americans suffer high rates of alcohol and drug dependence and higher alcohol related death rates than any other U.S. ethnic group and alcohol dependence rates up to five times that of the general U.S. population (Beals et al., 2005a; Ehlers et al., 2004a, 2006; Kunitz, 2006; May, 1982; May and Smith, 1988; Robin et al., 1998; Shalala et al., 1999). Efforts to delineate factors which may uniquely contribute to increased likelihood of current trauma, the impact of historical trauma, and the increased rates of substance use disorder (SUD) symptoms in Native Americans are important because of the high burden of morbidity and mortality that these phenomena pose to some Native American communities.

Measuring the nature and effects of historical trauma on American Indians is difficult, has not been universally standardized, and as such has mainly been described in theoretical and qualitative terms. More recently, Whitbeck and colleagues (2004a, 2004b, 2009) developed two measures relating to historical trauma among Indian people: The Historical Loss Scale and The Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale (Whitbeck et al., 2004a, 2004b, 2009). These scales quantify 12 types of losses that American Indian tribes might have experienced in the past (e.g., loss of land and language, broken treaties etc.) and how often they are thought about in the present time, and also measure 12 different symptoms they might have experienced as a result of thinking of those losses (e.g., anger, depression, anxiety, etc.).

The results of studies using those scales has shown that American Indian adults and adolescents, in the communities assessed, have frequent thoughts pertaining to historical losses and thoughts of these losses are associated with negative symptomatology. These scales have not been used by other research groups and the relationship between responses on these scales and current trauma, substance dependence, and affective and anxiety disorders has not been investigated. Thus, we sought to evaluate whether and to what extent demographic characteristics, trauma, exposure and the presence of psychiatric diagnoses influence thoughts pertaining to historical loss and the negative emotions associated with those thoughts.

The present report is part of a larger family study exploring risk factors for substance dependence in a community sample of American Indians (Ehlers et al., 2001a, 2001b, 2001c, 2001d, 2004a, 2008c; Gilder et al., 2004, 2006, 2007, 2009). The lifetime prevalence of trauma and substance dependence in this Indian population is high and genetic and environmental risk factors for substance dependence have been identified (Ehlers and Wilhelmsen, 2005, 2007; Ehlers et al., 2004b, 2006, 2007a, 2007b, 2007c, 2008a, 2008b, 2009, 2010a, 2010b, 2011, 2012; Gizer et al., 2011; Wall et al., 2003; Wilhelmsen and Ehlers, 2005). However, a description of the potential effects of current trauma, substance dependence and other mental health issues on thoughts of historical loss and associated symptomatology has not been reported in this Indian population. Therefore, the aims of the present study were: (1) to use the Historical Loss Scale to describe the extent of the experience of historical loss and the frequency of thoughts of historical loss; and to use the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale to describe the associated feelings and emotional responses to the experience of historical loss, in this Native American community; (2) to study the relationship of current traumatic events and diagnoses of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and the frequency of thoughts of historical loss and symptomatology associated with those thoughts; (3) to determine if correlations exist between cultural identification and percent Native American Heritage and thoughts of historical loss and feelings associated with those thoughts; and (4) to determine the association substance dependence, affective/anxiety disorders, and conduct disorder/antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) with the frequency of thoughts of historical loss and feelings associated with those thoughts.

2. METHODS

2.1 Participants

American Indian participants were recruited from eight geographically contiguous reservations with a total population of about 3,000 individuals. Participants were recruited using a combination of a venue-based methods for sampling hard-to-reach populations (Kalton and Anderson, 1986; Muhib et al., 2001) and a respondent-driven procedure (Heckathorn, 1997) that has been described elsewhere (Gilder et al., 2004). To be included in the study, participants had to be at least 1/16th Native American Heritage (NAH), be between the ages of 18 and 70 years, and be mobile enough to be transported from his or her home to The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI). The protocol for the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of TSRI, and the board of Indian Health Council, a tribal review group overseeing health issues for the reservations where recruitment was undertaken. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant after the study was fully explained.

2.2 Measures

Potential participants first met individually with research staff, and during a screening period participants had blood pressure and pulse taken, and completed a questionnaire that was used to gather information on demographics, personal medical history, ethnicity, and drinking history (Schuckit, 1985). Participants were asked to refrain from alcohol and drug usage for 24 hours prior to the testing. Each participant completed an interview with the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA) and the family history assessment module (FHAM; Bucholz et al., 1994), which was used to make substance use disorder and psychiatric disorder diagnoses according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-III-R) criteria, except PTSD which was DSM-IV criteria, in the probands and their family members (American Psychiatric Association, 1987). The SSAGA is a semi-structured, poly-diagnostic psychiatric interview that has undergone both reliability and validity testing (Bucholz et al., 1994; Hesselbrock et al., 1999). It has been used in another Native American sample (Hesselbrock et al., 2000, 2003). Eight hundred thirty five adult Native American participants have currently been evaluated from this community using the SSAGA.

After the study was designed and 539 adult participants had been evaluated, a number of new instruments were added to the study. A trauma questionnaire was supplemented to the SSAGA to assess lifetime quantitative trauma exposure in the participants. The stressful life events and response to stressful-life-events scale was added (Green, 1996). To measure historical trauma, the Historical Loss Scale and the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale (Whitbeck et al., 2004a, 2004b, 2009) were administered to each participant. These scales quantify 12 types of losses that American Indian tribes might have experienced in the past (e.g., loss of land and language, broken treaties etc.) and how often they are thought about in the present time, and also measure 12 different symptoms they might have experienced as a result of thinking about those losses (e.g., anger, depression, anxiety etc.). Currently, 306 participants have been evaluated using these scales. The amount of Native American Heritage (federal Indian blood quantum) was obtained from the subject’s report. Cultural Identification was assessed using the Orthogonal Cultural Identification Scale (OCIS) developed by Oetting and Beauvais (1990, 1991). This scale’s internal consistency for subscale scores was high and both concurrent and discriminant validity were demonstrated in this American Indian population (Venner et al., 2006).

2.3 Data Analysis

Data analyses were based on the 4 specific aims of this study. To investigate each aim, the number and percent of respondents who endorsed feelings of losses and associated symptoms as documented by each item of the two scales were tallied. A median split of the responses for each item of each scale was determined and the item scores were then dichotomized. The count of endorsed items, defined as items with scores above the median, for each of the two historical trauma scales were calculated, and these total scale scores were used as dependent variables in study analyses. The two scales were significantly correlated (r=0.46, p<0.001) suggesting moderate overlap between the two scales. As a result, two analytic approaches were used to address the study aims. The first approach used multivariate models that included both measures of historical loss as correlated dependent variables to estimate their relations with the independent variable(s) while considering the relationship between the dependent variables. These analyses were conducted using Mplus v6.1 (Muthen and Muthen, 2010).The second approach used univariate regression models to analyze each historical loss scale separately. In these models, the measure of historical loss not entered as a dependent variable was included as a covariate to estimate the unique variance in each dependent variable that was explained by the independent variable. These analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics v.20 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Significance was taken at the p < 0.05 level for all analyses.

The first aim of the study was to use the Historical Loss Scale and the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale to describe the extent of the experience of historical loss, the frequency of thoughts of historical loss and feelings associated with thoughts of historical loss in the described Native American community. To further investigate this aim, the effects of age, gender, marital status, number of years of education, and income on the scale scores were analyzed independently using the described multivariate regression approach.

The second aim was to study the relationship of current traumatic events and lifetime diagnoses of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) to frequency of thoughts and feelings of historical loss. To study this aim, select items from the stressful life events scale were used to assess exposure to trauma, and diagnoses of PTSD were derived from the SSAGA. These variables served as independent variables in multivariate regression models analyzing both historical loss scale scores as correlated dependent variables and univariate regression analyses analyzing the scale scores separately. In the first set of analyses, participants who reported yes to having experienced any of 7 assessed types of trauma (military combat, sexual abuse, injury or assault, natural disaster with loss, witnessed trauma, experienced crime without injury, unexpected death) and “assaultive trauma” (military combat, sexual abuse, injury or assault, experienced crime) were compared on total scores on each scale separately, to those who did not. In the second set of analyses, participants with a PTSD diagnosis were compared with those who did not meet diagnostic criteria for the disorder on their total scores on each scale separately.

The third aim analyses were conducted in order to determine if associations existed between cultural identification, percent Native American Heritage, and the frequency of thoughts and feelings of historical loss. In the first set of analyses high cultural identification with the “American Indian way of life” (average item score >3) was indexed on the OCIS and used as an independent variable to predict total scores on the two historical loss scales using the described multivariate and univariate regression approaches. In the second set of analyses each participant’s Native American Heritage (NAH), as indexed by self-report, was dichotomized to those individuals with 50% or greater NAH, and those with less than 50%. This NAH variable was then used as an independent variable in multivariate and univariate regression models predicting scores on the two historical trauma scales.

The fourth aim was to identify significant associations of the frequency of thoughts and feelings of historical loss with: substance dependence, anxiety/affective disorder, and antisocial personality disorder/conduct disorder (ASPD/CD). For this aim, multivariate and univariate regression analyses were conducted with each of the following diagnoses obtained from the SSAGA alternatively serving as the independent variable: substance dependence (SUB DEP) (dependence on any of the following substances: alcohol, cannabis, stimulants, sedatives, opiates, hallucinogens, solvents, nicotine), antisocial personality disorder or conduct disorder (ASPD/CD), and any anxiety or affective disorder (ANY AX/AF) (presence of any of the following anxiety or affective disorders: panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without panic, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, major depressive disorder, bipolar I disorder, and dysthymic disorder). Scores on the historical loss scales served as the dependent variable(s). Notably, PTSD was examined separately in the second aim analyses and not included among the anxiety and affective disorders given conflicting research reports suggesting that PTSD lies solely within the internalizing spectrum of psychopathological disorders (Keyes et al., 2013; Roysamb et al., 2011) and others suggesting it shares features with both internalizing and externalizing spectrum disorders (Freidman et al, 2011; Wolf et al., 2010).

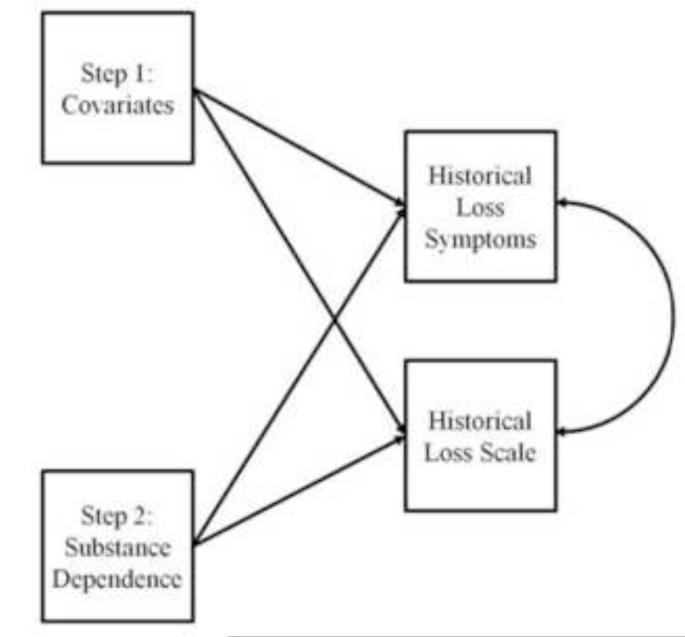

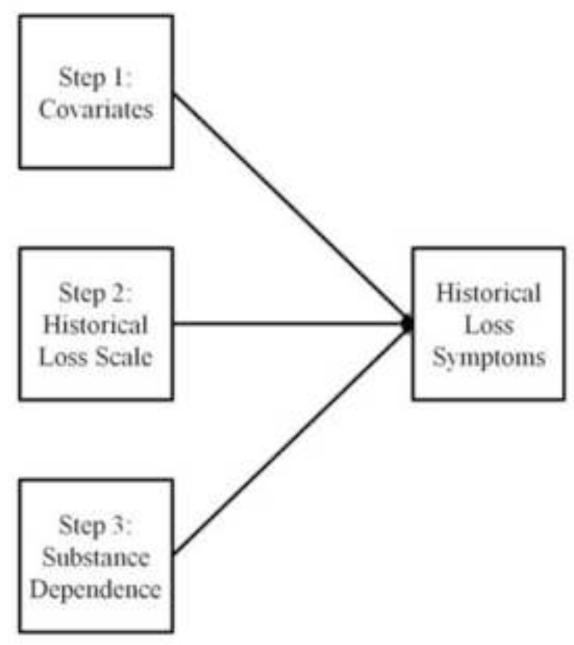

The relations between SUBDEP and ANY AX/AF diagnoses and the two historical loss scales were further explored using hierarchical (or sequential) multivariate and univariate regression models, which can determine the incremental contributions of the effects of an independent variable (e.g., SUBDEP or ANY AX/AF) on the dependent variable (e.g., historical loss) after accounting for the effects of covariates (e.g., demographics). For the multivariate and univariate models, demographic information (i.e., age, gender, education, marital status, and SES), Native American Heritage (i.e., degree of Native American Heritage and cultural identification) and additional diagnostic information (i.e., co-occurring PTSD and ASPD/CD) were entered at the first step. For the univariate models, the measure of historical loss not entered as a dependent variable was entered as an intermediate step (e.g., when modeling the Historical Loss Scale as a dependent variables, the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale was entered in this step), and in the final step for both approaches, the independent variable (SUBDEP or ANY AX/AF) was entered into the model (see figure 1A and 1B for examples of the multivariate and univariate models, respectively). The significance of the incremental contribution of SUBDEP or ANY AX/AF in this final step was determined by the increase in explained variance (i.e., R2) and the associated t-test and β.

Figure 1A.

Example of a multivariate heirarchical regression model with the Historical Loss Scale and Historical Loss Associated Symptom Scale as correlated dependent variables. Baseline variables are entered at Step 1 and the diagnostic variable (substance dependence in this example) is entered at Step 2.

Figure 1B.

Example of a univariate heirarchical regression model with either the Historical Loss Scale or Historical Loss Associated Symptom Scale as the dependent variable (the Historical Loss Associated Symptom Scale in this example). Baseline variables are entered at Step 1, the scale not serving as the dependent variable is entered in Step 2 (the Historical Loss Scale in this example) and the diagnostic variable is entered at Step 3 (substance dependence in this example).

3. RESULTS

Demographic and psychiatric variables of this sample are presented in Table 1. Data analyses for the first aim revealed that responses on the items that make up the Historical Loss Scale, suggest that the kinds of historical loss that the participants thought about and the frequency of those thoughts varied in this Native American community, as seen in Table 2. The Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale also showed a range of responses as seen in Table 3. Some of the demographic variables appeared to significantly impact scores on the two historical losses scales. Specifically, those participants who were married at the time of the assessment exhibited significantly lower scores on the Historical Loss Scale than participants that were not married (β=−0.12, t=−2.17, p=0.030), and participants with annual incomes above $20,000 had significantly lower scores on the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale than participants with annual incomes below $20,000 (β=−0.12, t=−2.00, p=0.045) as suggested by the multivariate regression analyses. All other comparisons were non-significant.

Table 1. Demographic and DSM-IV disorders in 306 Native American study participants.

| % (n) | % (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 52% (159) <30 | 48% (147) ≥30 |

| Gender | 44% (134) Male | 56% (172) Female |

| High School | 57% (173) Completed | 43% (133) Not Completed |

| Yearly Family Income | 59% (157) ≥$20k | 41% (111) <$20k |

| Married | 13% (39) Married | 87% (266) Not Married |

| Native American Heritage | 35% (102) ≥50% | 65% (193) <50% |

| Family History of Alcohol Dependence | 72% (214) FH+ | 28% (85) FH- |

| Alcohol Dependence | 48% (147) Alc Dep | 52% (159) No Alc Dep |

| Any Drug Dependence | 45% (137) Any Drug | 55% (169) No Drug |

| Antisocial Personality Disorder / Conduct Disorder | 19% (58) ASPD/CD | 81% (248) No ASPD/CD |

| Post Traumatic Stress Disorder | 32% (97) PTSD | 68% (209) No PTSD |

| Any Anxiety Disorder | 17% (53) Any AX | 83% (253) No AX |

| Any Affective Disorder | 37% (114) Any AF | 63% (192) No AF |

| Any Anxiety / Affective Disorder | 46% (140) Any AX/AF | 54% (166) No AX/AF |

Abbreviations: n-number of participants, <-less than, ≥-greater than or equal to, AX-anxiety, AF-affective, PTSD-post traumatic stress disorder, ASPD/CD-Antisocial personality disorder/conduct disorder, Alc Dep-Alcohol Dependence, Any Drug-any drug dependence, NAH-Native American heritage, k-1000, Ecostat-economic statistic, +-positive, (−)-negative

Table 2. Frequency of thoughts of historical loss from the Historical Loss Scale.

| Never | Yearly or at special times |

Monthly | Weekly | Daily | Several times a Day |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of our land | 29.0% | 30.9% | 16.7% | 10.4% | 6.7% | 6.3% |

| Loss of our language | 23.8% | 35.7% | 13.4% | 9.7% | 9.7% | 7.8% |

| Losing our traditional spiritual ways | 24.4% | 31.4% | 15.5% | 12.2% | 8.5% | 8.1% |

| The loss of our family ties because of boarding schools |

49.8% | 20.4% | 14.1% | 5.5% | 5.5% | 4.7% |

| The loss of families from the reservation to government relocation |

41.7% | 26.6% | 15.4% | 6.2% | 4.2% | 5.8% |

| The loss of self respect from poor treatment by government officials |

30.9% | 27.9% | 19.0% | 7.4% | 9.3% | 5.6% |

| The loss of trust in whites from broken treaties | 33.1% | 28.2% | 16.5% | 6.8% | 7.9% | 7.5% |

| Losing our culture | 23.9% | 25.4% | 20.8% | 9.8% | 11.4% | 8.7% |

| The losses from the effects of alcoholism on our people |

20.0% | 28.0% | 18.5% | 12.7% | 11.3% | 9.5% |

| Loss of respect by our children and grandchildren for elders |

18.7% | 19.8% | 20.1% | 13.2% | 16.1% | 12.1% |

| Loss of our people through early death | 16.7% | 25.8% | 22.2% | 14.5% | 9.8% | 10.9% |

| Loss of respect by our children for our traditional ways |

19.0% | 24.8% | 21.9% | 15.0% | 9.9% | 9.5% |

Abbreviations: %-percentage

Table 3. Frequency of experiencing emotional responses to losses from the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale.

| Always | Often | Sometimes | Seldom | Never | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sadness or depression | 5.1% | 7.6% | 36.1% | 24.9% | 26.4% |

| Anger | 4.0% | 9.7% | 36.8% | 20.9% | 28.5% |

| Anxiety or nervousness | 2.2% | 7.0% | 16.9% | 21.0% | 52.9% |

| Uncomfortable around white people when you think of these losses |

3.3% | 7.4% | 16.7% | 16.3% | 56.3% |

| Shame when you think of these losses | 2.6% | 6.3% | 26.5% | 18.0% | 46.7% |

| A loss of concentration | 3.0% | 5.9% | 19.9% | 19.2% | 52.0% |

| Feel isolated or distant from other people when you think of these losses |

2.6% | 5.5% | 18.6% | 18.2% | 55.1% |

| A loss of sleep | 3.6% | 3.6% | 15.7% | 16.1% | 60.9% |

| Rage | 2.6% | 5.5% | 15.9% | 17.7% | 58.3% |

| Fearful or distrust the intention of white people | 3.7% | 4.9% | 16.4% | 18.7% | 56.3% |

| Feel like it is happening again | 3.0% | 6.3% | 18.7% | 19.8% | 52.2% |

| Feel like avoiding places or people that remind you of these losses |

1.5% | 3.6% | 18.6% | 17.5% | 58.8% |

| Feel the need to drink or take drugs when thinking of these losses |

2.5% | 4.0% | 10.9% | 10.1% | 72.5% |

Abbreviations: %-percentage

The second aim was to study the relationship of historical loss and associated symptoms to current traumatic events and the diagnoses of PTSD. A very high number (94%) of the participants reported having experienced one of the 7 traumas (unexpected death, injury or assault, crime, witnessing trauma, natural disaster with loss, sexual abuse, military combat), a finding that limited the variance in the subsequent analyses for this variable. Those participants who did report having experienced at least 1 of the seven traumas did not differ on the total scores on either the Historical Loss Scale or the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale. Limiting the traumatic exposure to only those participants who had experienced assaultive trauma (70% of the participants) revealed a significant association with the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale (β=0.16, t=2.76, p=0.006) but not with the Historical Loss Scale in the multivariate regression analysis. Those participants with a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD had significantly higher total scores on the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale (β=0.17, t=3.00, p=0.003) but did not differ on the total scale of the Historical Loss Scale in the multivariate regression analyses (Table 4). Demonstrating the robustness of these results, the significant associations for the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale were similar in magnitude when scores on the Historical Loss Scale were included as a covariate (table 4).

Table 4.

Results of multivariate and univariate regression analyses evaluating Historical Loss Scale and Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale scores as a function of trauma-related and Native American identification variables

| Assaultive Trauma | PTSD | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | P | R2 | β | t | P | R2 | |

| Historical Loss Scale | ||||||||

| Multivariate model | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.949 | <0.01 | 0.03 | 0.47 | 0.639 | <0.01 |

| Univariate model1 | −0.07 | −1.31 | 0.192 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −1.01 | 0.314 | <0.01 |

| Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale | ||||||||

| Multivariate model | 0.16 | 2.76 | 0.006 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 3.00 | 0.003 | 0.03 |

| Univariate model2 | 0.15 | 3.01 | 0.003 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 3.08 | 0.002 | 0.02 |

| Native American Heritage | Native American Cultural Identity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | P | R2 | β | t | P | R2 | |

| Historical Loss Scale | ||||||||

| Multivariate model | 0.17 | 3.05 | 0.002 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 2.48 | 0.013 | 0.02 |

| Univariate model1 | 0.14 | 2.65 | 0.009 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 1.90 | 0.059 | 0.01 |

| Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale | ||||||||

| Multivariate model | 0.08 | 1.37 | 0.170 | <0.01 | 0.10 | 1.67 | 0.100 | <0.01 |

| Univariate model2 | <0.00 | 0.03 | 0.976 | <0.01 | 0.03 | 0.59 | 0.555 | 0.001 |

Note

Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale scores included as covariate

Historical Loss Scale scores included as covariate.

In the third aim analyses were conducted in order to determine if associations existed between cultural identification, percent Native American Heritage, and the frequency of thoughts of historical loss. Roughly half (47%) of the participants endorsed “high identification with the American Indian way of life” and those individuals also had higher total scores on the Historical Loss Scale (β=0.14, t=2.48, p=0.013) but not on the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale as suggested by the multivariate regression analyses. There were no significant associations between “high identification with the White way of life” and either of the Historical Loss Scales. Thirty-five percent of the participants indicated that they had 50% or greater NAH and those individuals also had higher total scores on the Historical Loss Scale (β=0.17, t=3.05, p=0.002) but not on the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale (Table 4). The significant relation between the Historical Loss Scale and American Indian “identification” was weakened to a trend when scores on the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale were included as a covariate in the analysis (β=0.10, t=1.90, p=0.059), whereas the relation between the Historical Loss Scale and NAH was relatively unchanged when scores on the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale were included as a covariate (β=0.14, t=2.65, p=0.009; Table 4).

The fourth aim was to identify significant associations of the frequency of thoughts of historical loss with: SUB DEP, ANY AX/AF, and ASPD/CD. Sixty-six (66%) percent of the participants had a lifetime diagnosis of SUB DEP and those individuals had significantly higher total scores on the Historical Loss Scale (β=0.12, t=2.08, p=0.038) and on the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale (β=0.24, t=4.45, p<0.001) as suggested by the multivariate regression analyses. Nineteen percent (19%) of the participants had a lifetime diagnosis of ASPD/CD, however, those individuals did not differ on their total scores on the Historical Loss Scale or the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale (data not shown). Finally, 46% of the participants had a lifetime diagnosis of ANY AX/AF, and those individuals did not differ on total scores on the Historical Loss Scale (β=−0.03, t=−0.56, p=0.576) but did have higher scores on the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale (β=0.16, t=2.90, p=0.004) as suggested by the multivariate regression analyses.

In order to further explore the relations between SUBDEP and ANY AX/AF diagnoses and the two historical loss scale total scores, we constructed hierarchical regression models to determine the incremental contributions of SUBDEP and ANY AX/AF in explaining participants’ scores on the two historical loss scales over and above relevant demographic, Native American Heritage, and other diagnostic variables using the multivariate and univariate approaches described above. The first approach utilized a multivariate regression model with the two historical loss scales modeled as correlated dependent variables. These analyses indicated statistically significant associations between SUBDEP and both the Historical Loss Scale (β=0.17, t=2.59, p=0.008) and the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale (β=0.23, t=3.43, p<0.001). In contrast, the associations between ANY AX/AF and the Historical Loss Scale (β=−0.09, t=−1.52, p=0.130) and the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale (β=0.10, t=1.65, p=0.098) did not reach statistical significance (table 5).

Table 5. Hierarchical regression analyses examining the relations between Historical Loss Scales and Anxiety and Substance Dependence Diagnoses.

| Any Anxiety or Mood Disorder | Any Substance Dependence | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Diagnosis | |||||||

| β | t | P | ΔR2 | β | t | P | ΔR2 | |

| Multivariate analyses | ||||||||

| Historical Loss Scale | ||||||||

| After Step 1 (demographics, Native American heritage, other diagnoses) |

−0.09 | 1.52 | 0.130 | <0.01 | 0.17 | 2.59 | 0.008 | 0.02 |

| Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale | ||||||||

| After Step 1 (demographics, Native American heritage, other diagnoses) |

0.10 | 1.65 | 0.098 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 3.43 | <0.001 | 0.04 |

| Univariate analyses | ||||||||

| Historical Loss Scale | ||||||||

| After Step 1 (demographics, Native American heritage, other diagnoses) |

-0.08 | 1.30 | 0.195 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 2.07 | 0.040 | 0.02 |

| After Step 2 (Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale) |

−0.13 | 2.37 | 0.018 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.67 | 0.501 | <0.01 |

| Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale | ||||||||

| After Step 1 (demographics, Native American heritage, other diagnoses) |

0.12 | 1.85 | 0.065 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 3.40 | 0.001 | 0.04 |

| After Step 2 (Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale) |

0.15 | 2.72 | 0.007 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 2.76 | 0.006 | 0.02 |

Note: Step 1 variables included age, gender, marital status, annual income above $20,000, high school graduate, Native American ancestry >50%, Native American cultural identification, PTSD, ASPD/CD.

The univariate analyses yielded slightly different results. For the Historical Loss Scale, only SUBDEP showed a significant incremental relation with experiences of historical loss (β=0.14, t=2.07, p=0.040). This relation became non-significant, however, when controlling for scores on the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale (β=0.04, t=0.67, p=0.501). ANY AX/AF showed a relation with the Historical Loss Scale after controlling for scores on the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale but in a direction that was opposite of what would be expected (β=−0.13, t=2.37, p=0.018; Table 5).

For the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale, SUBDEP showed a significant incremental relation (β=0.22, t=3.40, p=0.001), and ANY AX/AF showed a statistical trend for such a relation (β=0.12, t=1.85, p=0.065). Notably, the relation between SUBDEP and the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale remained significant but was weakened after also controlling for scores on the Historical Loss Scale (β=0.16, t=2.76, p=0.006). In contrast, the relation between ANY AX/AF and the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale was strengthened and achieved statistical significance after controlling for scores on the Historical Loss Scale (β=0.15, t=2.72, p=0.007; Table 5).

4. DISCUSSION

The American Indian community that participated in the research described in the present report experienced a number of traumatic historical events capable of inducing thoughts of and feelings associated with historical trauma (Carrico, 1987). The use of the Historical Loss Scale to index how often this Indian community thinks about these historical losses was addressed in the present report. It was found that most participants (~30%) thought about these losses “yearly or at special times”. However, about one quarter of the participants thought “daily” about the loss of culture, language and loss of respect for elders, whereas; a lower percentage (10-15%) thought daily of the history of broken treaties, losses due to boarding school, loss of land, and government relocation. Thus in this Indian community, thoughts of historical losses are certainly part of their thinking in present time.

One important question is whether there is variation in the frequency of thoughts about historical loss or the symptoms associated with those losses between different Indian communities. Thus, a comparison of the findings on the Historical Loss Scale obtained from this reservation-based Indian community to those reported by Whitbeck and colleagues (2004a, 2004b, 2009) for Indian communities living on reservations in the upper Midwestern U.S. and Ontario, Canada is warranted. Approximately the same proportion of individuals in each community thought about the losses “several times a day”, whereas in the U.S./Canada sample 2-3 times as many people thought of the losses “daily” and a larger percentage thought of them “weekly” than in the present sample who thought of them more “yearly or at special times”. The differences between the populations could be due to a number of issues that theoretically could include: the extent of historical losses suffered by each individual community, the impact of current trauma, levels of acculturation, population norms about historical losses, and population admixture. These data do suggest that differences in the experience of Historical loss most likely exist between different Indian communities.

Whitbeck and colleagues (2004a, 2004b) have raised the question of whether current conditions in Indian communities, in particular, economic disadvantage, discrimination, health issues, trauma and high mortality rates might be attributed to historical causes, however, the origins of the symptoms could actually be more related to contemporary experiences. In the present study the potential impact of contemporary trauma exposure and PTSD diagnoses on responses on the historical loss scales were investigated. The present Indian community reported a very high level of contemporary trauma with 94% of the respondents indicating that they had experienced significant life threatening trauma in their lifetime (Ehlers et al., 2012). Among participants who had experienced trauma, one third of them endorsed a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD attributable to the trauma (Ehlers et al., 2012); however, having experienced “any trauma”, “assaultive trauma,” or having a diagnosis of PTSD was not associated with higher scores on the Historical Loss Scale. Thus, the experience of contemporary trauma did not appear to influence how often an individual thought about historical losses. Nonetheless, because of the high rates of trauma exposure such analyses may suffer from methodological issues.

In contrast, the contemporary experience of assaultive trauma PTSD and/or the presence of an anxiety/affective disorder was clearly found to influence how thoughts of historical losses impacted participants emotionally. Significantly higher total scores on the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale were found in individuals who had experienced assaultive trauma, PTSD and/ or anxiety/affective disorder. These relations were further supported in analyses demonstrating that they remained significant even after controlling for scores on the Historical Loss Scale or when both scale scores were analyzed as correlated dependent variables in a multivariate analysis. Interestingly, another disadvantaging contemporary factor that was found to lead to higher scales on the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale but not the Historical Loss Scale was low income (< $20,000 a year). Taken together these data suggest that contemporary experiences may not influence how often an individual thinks about historical losses but might provide “a lens or filter that colors” the emotional experience associated with thoughts of historical loss when they do think about them.

Another important question concerning the American Indian experience of historical loss is whether it is primarily “localized” to the generation of elders who are closer to the losses or to those with more cultural or genetic ties to American Indian heritage. Contrary to this belief, Whitbeck et al. (2009) actually found, in a study of historical loss among North American Indian adolescents, that the adolescents reported “daily or more” thoughts of historical loss at rates similar to their older female caretakers. In the present study, those participants who were under 30 years of age showed no differences in thoughts about historical loss than participants above 30 years of age. In contrast reporting having a higher degree of Native American Heritage or more identification with the “Indian way of life” did impact how often an individual thought about historical losses but only minimally influenced the degree of emotional experience of those losses. This suggests that as population admixture and enculturation increase, the amount of time an individual spends thinking about historical losses may decrease. However, these data also suggest that thoughts of losses do not seem to be waning in the younger generation.

The general theory of historical trauma and substance dependence in American Indians is that historical unresolved grief contributes to or exacerbates the current social pathology of trauma and alcoholism and other social problems among American Indians (Brave Heart and DeBruyn, 1998). A relationship between contemporary experiences of trauma, PTSD and substance dependence has been studied in a number of Indian communities (Brave Heart, 1999; 2003; Gray and Nye, 2001; Morgan and Freeman, 2009; Szlemko et al., 2006; Whitbeck et al., 2004b). In the long standing psychiatric epidemiology study of two northern plains and one southwest American Indian population findings of high rates of alcohol use disorders and traumatic stress were found when compared to other populations (Beals et al., 2005a, 2005b; Boyd-Ball et al., 2006). High rates of trauma, PTSD symptomatology and alcoholism have also been reported in American Indian adolescents in substance abuse treatment (Deters et al., 2006), and in American Indian veterans (Westermeyer et al., 2009). In the present study, sixty-six (66%) percent of the participants had a lifetime diagnosis of SUB DEP and those individuals had significantly higher total scores on both the Historical Loss Scale and on the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale. Nonetheless, the former relation was non-significant after controlling for scores on the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale, whereas the latter relation remained significant after controlling for scores on the Historical Loss Scale. This suggests that individuals with substance dependence experience more distress related to historical losses than those individuals without substance dependence, and this may in turn lead them to think about historical losses more often. Unfortunately, the reviewed and present studies utilized cross-sectional data and cannot conclusively account for the direction of the associations between thoughts of historical trauma, substance dependence, and contemporary trauma and PTSD. Longitudinal studies investigating the onset of the experience of these phenomena will need to be accomplished to shed light on directionality. Additionally, the present report was primarily descriptive and exploratory in nature. As a result, a number of statistical tests were conducted in the present report without correcting for multiple testing, which could have resulted in some spurious results. Nonetheless, the present report provides compelling evidence that in this American Indian community thoughts about historical losses and their associated symptomatology are common and that the presence of these thoughts are associated with high degrees of Native American Heritage and cultural identification, and substance dependence.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Greta Berg, Linda Corey, Philip Lau, Susan Lopez, Evelyn Phillips, Shirley Sanchez, and Derek Wills, for assistance in data collection and analysis.

ROLE OF FUNDING SOURCE

Funding for this study was provided by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH); from the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA) and the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD) 5R37 AA010201 (CLE), and the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) DA030976 (CLE, IRG). NIAAA, NCMHD and NIDA had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONTRIBUTORS

Cindy L. Ehlers and Rachel Yehuda were responsible for the study design. David Gilder was responsible for collecting and coding the clinical data and making all the best final diagnoses. Ian R. Gizer and Jarrod M. Ellingson were responsible for higher level statistical analyses. Cindy L. Ehlers, Rachel Yehuda, and Ian R. Gizer were responsible for the preparation of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnosis and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III-R) American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Barocas HA. Children of purgatory: reflections on the concentration camp survival syndrome. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 1975;21:87–92. doi: 10.1177/002076407502100202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Novins DK, Whitesell NR, Spicer P, Mitchell CM, Manson SM. Prevalence of mental disorders and utilization of mental health services in two American Indian reservation populations: mental health disparities in a national context. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005a;162:1723–1732. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Manson SM, Whitesell NR, Mitchell CM, Novins DK, Simpson S, Spicer P. Prevalence of major depressive episode in two American Indian reservation populations: unexpected findings with a structured interview. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005b;162:1713–1722. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann MS, Jucovy ME. Generations of the Holocaust. Columbia University Press; New York: 1990. Originally published by Basic Books, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Ball AJ, Manson SM, Noonan C, Beals J. Traumatic events and alcohol use disorders among American Indian adolescents and young adults. J. Trauma Stress. 2006;19:937–947. doi: 10.1002/jts.20176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart MYH. The return to the sacred path: healing the historical trauma and historical unresolved grief response among the Lakota through a psychoeducational group intervention. Smith Coll. Stud. Soc. Work. 1998;68:287–305. [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart MY. Gender differences in the historical trauma response among the Lakota. J. Health Soc. Policy. 1999;10:1–21. doi: 10.1300/J045v10n04_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart MY. The historical trauma response among natives and its relationship with substance abuse: a Lakota illustration. J. Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35:7–13. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart MY, DeBruyn LM. The American Indian Holocaust: healing historical unresolved grief. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 1998;8:56–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveheart-Jordan M, DeBruyn LM. So she may walk in balance: integrating the impact of historical trauma in the treatment of Native American Indian women. In: Adleman J, Enguidanos-Clark GM, editors. Racism in the Lives of Women: Testimony, Theory, and Guides to Anti-Racist Practice. Haworth Press; New York: 1995. pp. 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, Jr., Reich T, Schmidt I, Schuckit MA. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1994;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico RL. Strangers in a Stolen Land: American Indians in San Diego, 1850-1880. Sierra Oaks Pub. Co; Sacramento, CA: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Danieli Y. International Handbook of Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma. Plenum Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Denham AR. Rethinking historical trauma: narratives of resilience. Transcult. Psychiatry. 2008;45:391–414. doi: 10.1177/1363461508094673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deters PB, Novins DK, Fickenscher A, Beals J. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology: patterns among American Indian adolescents in substance abuse treatment. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76:335–345. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Wall TL, Garcia-Andrade C, Phillips E. Effects of age and parental history of alcoholism on EEG findings in mission Indian children and adolescents. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2001a;25:672–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Wall TL, Garcia-Andrade C, Phillips E. Auditory P3 findings in mission Indian youth. J. Stud Alcohol. 2001b;62:562–570. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Wall TL, Garcia-Andrade C, Phillips E. EEG asymmetry: relationship to mood and risk for alcoholism in Mission Indian youth. Biol. Psychiatry. 2001c;50:129–136. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Wall TL, Garcia-Andrade C, Phillips E. Visual P3 findings in Mission Indian youth: relationship to family history of alcohol dependence and behavioral problems. Psychiatry Res. 2001d;105:67–78. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Wall TL, Betancourt M, Gilder DA. The clinical course of alcoholism in 243 Mission Indians. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2004a;161:1204–1210. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Gilder DA, Wall TL, Phillips E, Feiler H, Wilhelmsen KC. Genomic screen for loci associated with alcohol dependence in Mission Indians. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2004b;129B:110–115. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Wilhelmsen KC. Genomic scan for alcohol craving in Mission Indians. Psychiatr. Genet. 2005;15:71–75. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200503000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Slutske WS, Gilder DA, Lau P, Wilhelmsen KC. Age at first intoxication and alcohol use disorders in Southwest California Indians. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2006;30:1856–1865. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Wilhelmsen KC. Genomic screen for substance dependence and body mass index in Southwest California Indians. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:184–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Slutske WS, Gilder DA, Lau P. Age of first marijuana use and the occurrence of marijuana use disorders in Southwest California Indians. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2007a;86:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Phillips E, Finnerman G, Gilder D, Lau P, Criado J. P3 components and adolescent binge drinking in Southwest California Indians. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2007b;29:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Wall TL, Corey L, Lau P, Gilder DA, Wilhelmsen K. Heritability of illicit drug use and transition to dependence in Southwest California Indians. Psychiatr. Genet. 2007c;17:171–176. doi: 10.1097/01.ypg.0000242201.56342.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Gilder DA, Slutske WS, Lind PA, Wilhelmsen KC. Externalizing disorders in American Indians: comorbidity and a genome wide linkage analysis. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2008a;147B:690–698. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Lind PA, Wilhelmsen KC. Association between single nucleotide polymorphisms in the mu opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) and self-reported responses to alcohol in American Indians. BMC Med. Genet. 2008b;9:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Gilder DA, Phillips E. P3 components of the event-related potential and marijuana dependence in Southwest California Indians. Addict. Biol. 2008c;13:130–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Gilder DA, Gizer IR, Wilhelmsen KC. Heritability and a genome-wide linkage analysis of a Type II/B cluster construct for cannabis dependence in an American Indian community. Addict. Biol. 2009;14:338–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00160.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Gizer IR, Vieten C, Wilhelmsen KC. Linkage analyses of cannabis dependence, craving, and withdrawal in the San Francisco family study. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2010a;153B:802–811. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Phillips E, Gizer IR, Gilder DA, Wilhelmsen KC. EEG spectral phenotypes: heritability and association with marijuana and alcohol dependence in an American Indian community study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010b;106:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Gizer IR, Gilder DA, Wilhelmsen KC. Linkage analyses of stimulant dependence, craving, and heavy use in American Indians. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2011;156B:772–780. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Gizer IR, Gilder DA, Yehuda R. Lifetime history of traumatic events in an American Indian community sample: heritability and relation to substance dependence, affective disorder, conduct disorder and PTSD. J. Psychiatr..Res. 2012;47:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Campbell T. Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: a multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. J. Interpers..Violence. 2008;23:316–338. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figley CR. Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in Those who Treat the Traumatized. Brunner/Mazel; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MJ, Resick PA, Bryant RA, Strain J, Horowitz M, Spiegel D. Classification of trauma and stressor-related disorders in DSM-5. Depress..Anxiety. 2011;28:737–749. doi: 10.1002/da.20845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilder DA, Wall TL, Ehlers CL. Comorbidity of select anxiety and affective disorders with alcohol dependence in Southwest California Indians. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2004;28:1805–1813. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000148116.27875.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilder DA, Lau P, Dixon M, Corey L, Phillips E, Ehlers CL. Co-morbidity of select anxiety, affective, and psychotic disorders with cannabis dependence in Southwest California Indians. J. Addict. Dis. 2006;25:67–79. doi: 10.1300/J069v25n04_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilder DA, Lau P, Corey L, Ehlers CL. Factors associated with remission from cannabis dependence in southwest California Indians. J. Addict. Dis. 2007;26:23–30. doi: 10.1300/J069v26n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilder DA, Lau P, Ehlers CL. Item response theory analysis of lifetime cannabis-use disorder symptom severity in an American Indian community sample. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:839–849. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gizer IR, Edenberg HJ, Gilder DA, Wilhelmsen KC, Ehlers CL. Association of alcohol dehydrogenase genes with alcohol-related phenotypes in a Native American community sample. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2011;35:2008–2018. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray N, Nye PS. American Indian and Alaska Native substance abuse: co-morbidity and cultural issues. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 2001;10:67–84. doi: 10.5820/aian.1002.2001.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BL. Trauma history questionnaire. In: Stamm BH, editor. Measurement of Stress, Trauma, and Adaptation. Sidran Press; Lutherville, MD: 1996. pp. 366–369. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc. Probl. 1997;44:174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Hesselbrock M, Easton C, Bucholz KK, Schuckit M, Hesselbrock V. A validity study of the SSAGA--a comparison with the SCAN. Addiction. 1999;94:1361–1370. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesselbrock MN, Hesselbrock VM, Segal B, Schuckit MA, Bucholz K. Ethnicity and psychiatric comorbidity among alcohol-dependent persons who receive inpatient treatment: African Americans, Alaska Natives, Caucasians, and Hispanics. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2003;27:1368–1373. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080164.21934.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesselbrock VM, Segal B, Hesselbrock MN. Alcohol dependence among Alaska Natives entering alcoholism treatment: a gender comparison. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2000;61:150–156. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalton G, Anderson DW. Sampling rare populations. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. 1986;149:65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Skodol AE, Wall MM, Grant B, Siever LJ, Hasin DS. Thought disorder in the meta-structure of psychopathology. Psychol. Med. 2013;43(8):1673–83. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunitz SJ. Life-course observations of alcohol use among Navajo Indians: natural history or careers? Med. Anthropol. Q. 2006;20:279–296. doi: 10.1525/maq.2006.20.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA. Substance abuse and American Indians: prevalence and susceptibility. Int. J. Addict. 1982;17:1185–1209. doi: 10.3109/10826088209056349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Smith MB. Some Navajo Indian opinions about alcohol abuse and prohibition: a survey and recommendations for policy. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1988;49:324–334. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan R, Freeman L. The healing of our people: substance abuse and historical trauma. Subst. Use Misuse. 2009;44:84–98. doi: 10.1080/10826080802525678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motta RW, Suozzi JM, Joseph JM. Assessment of secondary traumatization with an emotional Stroop task. Percept. Mot. Skills. 1994;78:1274. doi: 10.2466/pms.1994.78.3c.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhib FB, Lin LS, Stueve A, Miller RL, Ford WL, Johnson WD, Smith PJ. A venue-based method for sampling hard-to-reach populations. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(Suppl. 1):216–222. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. MPlus Users Guide (Version 6.1) [Computer software] Muthen and Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Niederland WG. Clinical observations on the “survivor syndrome”. Int. J. Psychoanal. 1968;49:313–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederland WG. The survivor syndrome: further observations and dimensions. J. Am. Psychoanal. Assoc. 1981;29:413–425. doi: 10.1177/000306518102900207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Beauvais F. Orthogonal cultural identification theory: the cultural identification of minority adolescents. Int. J. Addict. 1990;25:655–685. doi: 10.3109/10826089109077265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Beauvais F. Critical incidents: failure in prevention. Int. J. Addict. 1991;26:797–820. doi: 10.3109/10826089109058921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin RW, Long JC, Rasmussen JK, Albaugh B, Goldman D. Relationship of binge drinking to alcohol dependence, other psychiatric disorders, and behavioral problems in an American Indian tribe. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1998;22:518–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R. Impact of posttraumatic stress disorder of World War II on the next generation. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1986;174:319–327. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198606000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R, Nathan P. Secondary traumatization in children of Vietnam veterans. Hosp. Community Psychiatry. 1985;36:538–539. doi: 10.1176/ps.36.5.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Røysamb E, Kendler KS, Tambs K, Orstavik RE, Neale MC, Aggen SH, Torgersen S, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. The joint structure of DSM-IV Axis I and Axis II disorders. J. Abnorm..Psychol. 2011;120:198–209. doi: 10.1037/a0021660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Genetics and the risk for alcoholism. JAMA. 1985;254:2614–2617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalala DE, Trujillo MH, Hartz PE, Paisano EL. Trends in Indian health 1998-99. United States Department Health and Human Services; Indian Health Service; Division of Program Statistics; Washington, D.C: 1999. http://www.ihs.gov/publicinfo/publications/trends98/trends98.asp. [Google Scholar]

- Szlemko WJ, Wood JW, Thurman PJ. Native Americans and alcohol: past, present, and future. J. Gen. Psychol. 2006;133:435–451. doi: 10.3200/GENP.133.4.435-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venner KL, Wall TL, Lau P, Ehlers CL. Testing of an orthogonal measure of cultural identification with adult mission Indians. Cultur. Divers. Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2006;12:632–643. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.4.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall TL, Carr LG, Ehlers CL. Protective association of genetic variation in alcohol dehydrogenase with alcohol dependence in Native American Mission Indians. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2003;160:41–46. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermeyer J, Canive J, Thuras P, Thompson J, Crosby RD, Garrard J. A comparison of substance use disorder severity and course in American Indian male and female veterans. Am. J. Addict. 2009;18:87–92. doi: 10.1080/10550490802544912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Chen X, Hoyt DR, Adams GW. Discrimination, historical loss and enculturation: culturally specific risk and resiliency factors for alcohol abuse among American Indians. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2004a;65:409–418. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Adams GW, Hoyt DR, Chen X. Conceptualizing and measuring historical trauma among American Indian people. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2004b;33:119–130. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027000.77357.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Walls ML, Johnson KD, Morrisseau AD, McDougall CM. Depressed affect and historical loss among North American Indigenous adolescents. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 2009;16:16–41. doi: 10.5820/aian.1603.2009.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsen KC, Ehlers C. Heritability of substance dependence in a Native American population. Psychiatr. Genet. 2005;15:101–107. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200506000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Miller MW, Krueger RF, Lyons MJ, Tsuang MT, Koenen KC. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the genetic structure of comorbidity. J. Abnorm..Psychol. 2010;119:320–330. doi: 10.1037/a0019035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]