Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine acceptance of donor human milk (DM) for feeding preterm infants and whether offering DM, alters mothers’ milk (MM) feeding.

STUDY DESIGN

Infant feeding data were collected from medical records of 650 very preterm infants enrolled between 2006–2011 in two hospital level III neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) in Cincinnati, Ohio. The study was conducted during the implementation of a program offering 14 days of DM.

RESULT

From 2006–2011, any DM use increased from 8 to 77% of infants, largely replacing formula for the first 2 weeks of life; provision of MM did not change. DM was more likely to be given in the first 2 weeks of life, if infants never received MM or were >1000 g birth weight, but DM use did not differ by sociodemographic factors.

CONCLUSION

Offering DM dramatically increased human milk feeding and decreased formula use, but did not alter MM feeding in hospital.

Keywords: donor human milk, preterm infants, breast milk

INTRODUCTION

The American Academy of Pediatrics supports human milk as the preferred feeding for all infants, including preterm neonates.1 Providing human milk to preterm infants is associated with improved mental and motor development, decreased necrotizing enterocolitis, sepsis, retinopathy of prematurity and rehospitalization after discharge.2–6 Unfortunately, mothers who deliver preterm infants have particular difficulty initiating and sustaining lactation.7,8 A study of 243 preterm infants found that only one-quarter of their mothers provided sufficient breast milk to meet their infants’ needs.9 To provide human milk when mothers’ own milk (MM) is not available, many neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) have begun partnering with milk banks to obtain donor human milk (DM) for feeding preterm infants. The Human Milk Banking Association of North America, established in 1985, now includes 13 operational milk banks and 4 developing banks that provide milk to hospitals throughout North America. DM distributed through these milk banks is collected following standards similar to blood banks, and is additionally, pasteurized10 (https://www.hmbana.org/). Although pasteurization reduces some of the protective factors normally found in breast milk, health outcomes are reported to be significantly improved in infants fed DM compared with formula.2,5,10

Although feeding DM to preterm infants appears to be increasing11, published studies are lacking regarding the extent of use and maternal acceptance of DM. Further, while the intended use of DM is as a temporary substitute for mothers’ own milk, some have expressed concern that the use of DM may decrease mothers’ motivation to provide their own milk.

The purpose of this study was to examine the acceptance and use of DM in two level III NICUs in Cincinnati, Ohio, offering DM to preterm infants and to determine whether its use influences the extent of MM feedings in hospital.

METHODS

Subjects

Two independently developed databases were merged and analyzed for this study. The first database contained feeding data recorded as part of the Human Milk Project, a quality improvement initiative undertaken at University Hospital, Cincinnati, Ohio12, which included 454 preterm infants ≤1500 g birth weight and ≤32 weeks gestational age at delivery, admitted to the University Hospital (UH) NICU between January 2006 and June 2010. Mothers were encouraged to provide their own milk and to consent to DM feeding as a supplement to their own milk when necessary. The data were collected to evaluate the quality improvement goal of improving total human milk feeding of preterm infants through the use of both MM and DM. Maternal and infant demographic data were collected via retrospective chart review. Infant feeding data entered into the database were a cumulative measure of the volume of milk provided from DM, MM or formula for infant days of life (DOL) 1–14. This study was approved by institutional review boards of Cincinnati Children’s and UH.

The second database consisted of data collected from 256 infants admitted to either UH or Good Samaritan Hospital (GSH) NICUs between October 2009 and June 2011, whose mothers consented to the study. This database was generated to support a cohort study sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD, grant to ALM and KRS). UH and GSH instituted the DM program at about the same time, with apparently similar response. The value of this second database was the availability of data from both hospitals, as well as daily infant feeding data collected prospectively over the first 28 DOL. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of each hospital.

Inclusion of standardized common variables, allowed the two databases to be merged to prepare a common file for analysis of infant feeding that included infants in UH from 2006 to 2011 and GSH from 2009 to 2011. The first 14 days of feeding were summarized for all infants. Only 41 infants were found common in both databases; a single merged record was generated for these infants after comparing the original data files. The original data files were highly concordant in the summary infant feeding data over the first 14 days as well as clinical and sociodemographic data. When occasional discrepancies were found, the NICHD 2009–2011 cohort study was used as the standard. Before the introduction of a standard protocol in 2011, feedings were not standardized across the two hospitals except for policy regarding the use of DM as needed for the first 14 DOL until mother’s milk was available. The median time for the initiation of enteral feeds was <48 h in both hospitals, by which time DM consent was usually obtained. If DM was not available or consent was not obtained, feeds were not held. Mothers were also encouraged to provide their own milk by initiation of breast milk pumping in the first 12 h. Hospital-provided breast pumps were available for use. In addition, staff education through posters and newsletters was used to provide families with consistent breastfeeding information.

Statistical analysis

Human milk feeding patterns in study infants were categorized by volumes of MM, DM and formula for DOL 1–14. Changes in milk feeding patterns were analyzed for secular trends between 2006 and 2011 in UH. For infants born in 2009 through 2011 in both hospitals, we analyzed the detailed of daily feeding data available over the first month of life, excluding 19 (7%) infants with the feeding data available for less than four DOL; we grouped DOL as 1–3, 4–14, 15–21 and 22–28. Maternal age, marital status, insurance, multiple gestation, gravida, infant race, gestational age, birth weight and provision of any MM or any formula were analyzed in relation to provision of any DM in the 14 days of hospitalization by logistic regression analysis. All factors were initially included in the model, and a backward elimination procedure was used to remove factors that were not significant. The final model included only significant (P<0.05) factors. Infants, not receiving enteral feeds in the first 3 days were evaluated as a distinct subgroup and did not significantly influence the findings of this study.

RESULTS

Study population

A total of 650 infants were studied, of whom 31% of infants were multiple births, 69% were delivered by cesarean section and 56% were Medicaid patients. Infant median length of stay was 47 days and ranged from 4 to greater than 169 days (Table 1). The patient populations of the hospitals, included in this study differed significantly (P<0.001), as seen in Table 1, specifically, in their percent Medicaid-insured, marital status, multiple vs singleton births and non-hispanic black populations. These characteristics were examined in relation to donor milk use.

Table 1.

Variable, description

| UH | GSH | |

|---|---|---|

| Years enrolled | 2006–2011 | 2009–2011 |

| Number of infants enrolled | 474 | 176 |

| Birth weight, median (range, g) | 1090 (415– 1500) |

1095 (500–1500) |

| Gestational age, median (range, weeks) |

28 (23–32) | 28 (23–32) |

| Cesarean section, n (%) | 328 (69.5) | 119 (67.6) |

| Multiple birth, n (%) | 125 (26.5) | 74 (42.1)a |

| Non-hispanic black, n (%) | 201 (43.2) | 40 (24.5)a |

| Maternal age, median (range, years) |

26 (14–44) | 27 (18–44) |

| Married, n (%) | 148 (31.8) | 87 (49.7)a |

| Medicaid, n (%) | 292 (62.5) | 69 (39.2)a |

Abbreviations: UH, University Hospital; GSH, Good Samaritan Hospital.

Significant difference between hospital study populations, P<0.001.

Secular trends in milk feeding

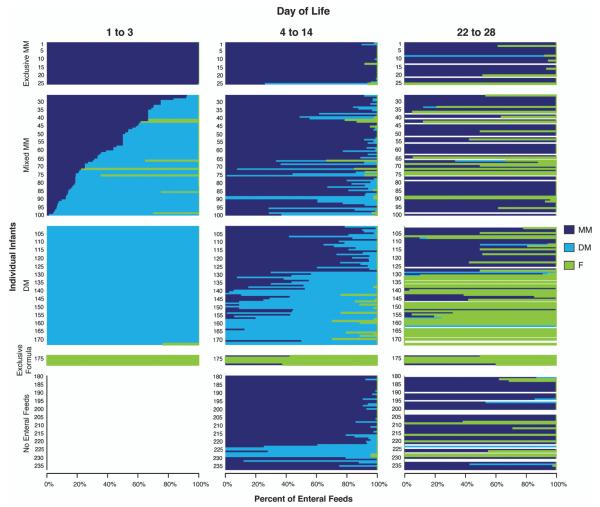

Infant feeding volumes and milk feeding subgroups for UH are shown in Figure 1, beginning with 2006, when the DM feeding program began, to 2011. DM feedings increased, while formula feeding decreased (P<0.001) over this period. In 2006, only 8% of infants received DM, while in 2010–2011, 77% of infants were never fed donor milk. No change was observed over time in the percent of infants fed with mothers’ own milk.

Figure 1.

UH. (a) Annual milk volumes as a percent of total milk feedings of preterm infants for DOL 1–14. (b) Annual frequency of different milk feeding patterns over DOL 1–14. DM, Donor; F, Formula; human milk; MM, mother’s own milk. MM & F group includes infants regardless of whether they received donor milk. Data from UH only, n = 474 infants.

DM acceptance

Before the introduction of the DM program, a convenience sample of 13 mothers at UH were surveyed to anticipate maternal acceptance; 77% of mothers stated that they would consent to the use of DM.12 By 2010–11, 97% of mothers consented to DM. Only a few mothers did not feel comfortable using another mother’s milk. Other instances, in which consent was not obtained included: an H1N1 outbreak, during which critically-ill mothers were unable to give consent; in another case a mother died after delivery and the father was unavailable to provide a consent.

First month feeding patterns

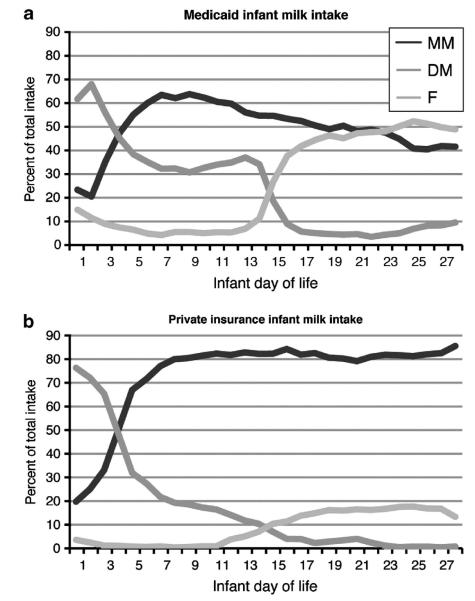

Infant feeding patterns for the first 28 DOL, were analyzed using daily feeding data from 237 infants born between 2009 and 2011, as shown in Figure 2. During DOL, 1 – 3, a total of 179 infants were fed enterally, of whom 25 (14%) were exclusively fed MM; 7 (4%) were exclusively fed formula; 75 (42%) received mixed MM along with either DM or in a few cases, formula; and 72 (40%) were fed DM but no MM in the first 3 days. A total of 140 (78%) were fed at least some DM during days 1 – 3 of life. Among those fed at least some donor milk, two general feeding patterns of DM were identified. Some used DM in the first few days as a bridge to initiate MM feeding by days 4–14 (for example, most of those numbered 80–125 in Figure 2). For these mothers and infants, DM was used as a short-term replacement for MM before it was available. The other major pattern, exemplified by infants numbered 131–170 in Figure 2, had DM as a replacement for formula feeding over the first 14 DOL, when mothers were either unable or unwilling to provide MM; the majority of these infants transitioned to formula feeding after day 14 once DM was no longer available. Figure 2 illustrates other key patterns also. For example, the 25 infants who received early exclusive MM feeding (numbered 1–25 in Figure 2) tended to have continued provision of MM throughout the first month of life. Only seven infants (numbered 174–180) received formula in the first 14 DOL, and they continued to receive only formula for the first month. Of the 56 infants, who did not receive enteral feeds in the first three DOL (infants 180–235), the majority received MM during days 4–14 with a lower percentage of DM feeding; such mothers were encouraged to pump and store their milk while only parenteral feeds were given, and thus, likely had a store of MM available to feed the infant.

Figure 2.

Average daily percent of enteral feeds composed of MM, DM and formula for DOL 1–3, 4–14 and 22–28. Each horizontal bar represents an individual infant’s feeding pattern over time. Infants are grouped based on their feeding pattern during DOL 1–3: Exclusive MM, Mixed MM (MM & any other feeding type), DM (no MM), exclusive formula and no enteral feeds. Data from 2009–2011, both hospitals, n = 237 infants.

By virtue of the feeding protocol, infants still receiving DM during days 4–14 transitioned soon after day 14 to formula feeding if mothers’ milk was not available. By days 22–28, 86% of those previously fed only DM and half of those previously fed more DM than MM transitioned to formula feeding. Among infants who received a combination of MM and formula during DOL 4–14, half continued with this pattern, while one-third transitioned to exclusive formula feeding by DOL 22–28. This latter group, represents mothers who expressed their milk for a few weeks because the clinical staff recommended it, but whose original intention was formula feeding. In contrast, among infants fed any MM during DOL 4–14, MM comprised 91% of feedings during DOL 22–28.

Analysis of factors associated with donor milk use

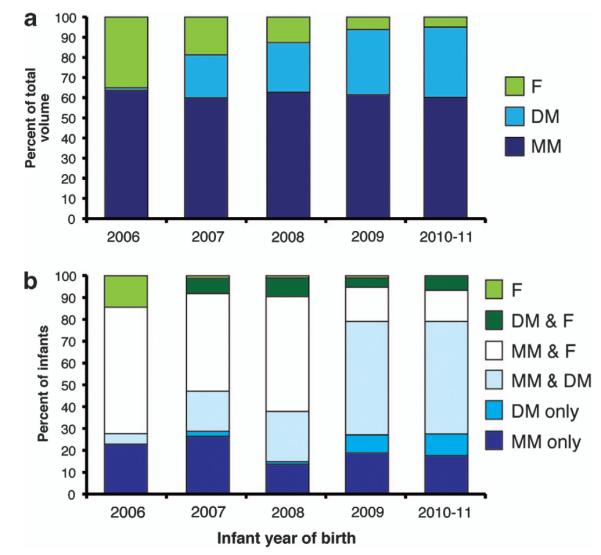

Infant feeding patterns over the first 28 DOL varied significantly by insurance source, a measure of socioeconomic status (Figure 3). Provision of mothers’ own milk was higher in the privately insured (P<0.001) while DM (P<0.001) and formula use (P = 0.01) were higher in the Medicaid-insured. However, multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the combined effects of factors influencing donor milk use, including all sociodemographic and clinical factors in Table 1, and the provision of mother’s own milk. The final model, including only significant factors, is shown in Table 2. Differing patient populations at GSH and UH account for significant differences in feeding patterns. DM was significantly more likely to be given in the first 14 DOL to infants >1000 g birth weight (P<0.001). DM was also significantly less likely to be given if mothers ever gave their own milk (P = 0.008), again indicating that provision of DM did not undercut the provision of MM, but was predominantly replacing formula use.

Figure 3.

Percent of total intake of MM, DM and F for each infant DOL, by insurance type (a) Medicaid insurance; (b) Private insurance). Data from 2009–2011, both hospitals, n = 237 infants.

Table 2.

Independent variables significantly associated with any use of donor milk in the first 14 DOL, 2006–2011, adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) by logistic regression analysis (n = 650)

| Independent variables | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Any MM | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | 0.008 |

| Birth weight >1000 g | 2.5 (1.7–3.3) | <0.001 |

| Hospital | 2.3 (1.3, 3.9) | 0.004 |

| Year of birth | 2.3 (2.0, 2.7) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence intervals; MM, mothers’ milk; OR, odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

As the initiation of DM programs in level III NICUs in Cincinnati, Ohio, there has been a significant increase in use of DM and a proportionate decrease in formula feedings. Maternal or legal guardian signed consent, is required in order to provide DM, indicating maternal acceptance. Despite the increase in DM from 2006 to 2011, provision of MM remained constant, indicating that offering DM did not negatively influence mothers to provide their own milk to their preterm infants in our NICUs. Nevertheless, offering DM while supporting MM feeding dramatically increased the provision of human milk to preterm infants, from 65% of milk volume in 2006 to 94% of milk volume from 2010 to 2011 over the first 14 DOL. Formula feedings decreased proportionately. But as this program provided DM for only the first 14 days, by the third week of hospitalization, infants not receiving MM transitioned to formula.

Two distinct patterns of DM use were identified. Many mothers used DM as a bridge until their own milk supply was adequate to support their infants’ needs. This was evident in infants who were fed a greater volume of MM than DM in the first 2 weeks; the majority of these infants were given exclusive MM feedings by day of life 28. We speculate that increased provision of DM in the first few DOL may be due to the mother’s inability to provide the volume of milk needed by a larger infant. In addition, as the average time for initiation of enteral feeding was <48 h of life, early feedings required the use of DM when MM was not available and contributed to the high proportion of infants ever given DM. Mothers who deliver preterm infants face major barriers in producing sufficient breast milk to meet their infants’ needs.7,13 The onset of copious milk production (lactogenesis stage II, or secretory activation) is often delayed in mothers who deliver preterm infants. Historically, many NICUs have provided formula early in hospitalization to infants whose mothers intend to exclusively breastfeed but whose milk supply is delayed; offering DM provides these mothers and hospital NICUs with another human milk option. Alternatively, a second use of DM was as a temporary substitute for formula feeding. In our study, we found that these infants received primarily DM and little or no mothers’ own milk during the first 2 weeks, with increasing formula use through their hospital stay. A small group of infants not receiving enteral feeds in the first few DOL were also included. The majority of these infants received MM by days 4–14, which may be a result of maternal pumping and saving of MM leading to less DM feeding in the first few DOL.

The two major approaches to DM feeding were to provide a bridge to MM feeding or a short-term replacement for formula. Regardless, DM was widely accepted among mothers of preterm infants. DM was used as a bridge and replacement almost equivalently. For the majority (77%) of mothers, DM filled an important role, providing additional human milk feeding for preterm infants.

DM costs as much as $4.00 per ounce or more, depending on the milk bank, but is provided to NICUs at a cost for the health and nutrition of preterm infants. Wight et al.14 have estimated that for every $1 spent on donor milk purchase, $11 is saved in excess length of stay due to reduced burden of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) or sepsis cases. Nevertheless, MM is the preferred method of infant feeding for many reasons, including its freshness or lack of processing, the immunologic match of MM (for example, specific immunoglobulins) to the common mother-infant environment, mother-infant bonding and sustained affordability. Helping mothers provide their own milk, warrants greater attention in order to optimize the health outcomes of preterm infants not only during hospitalization, but also after discharge.15 A variety of factors influence a mother’s ability to produce milk to feed her preterm infant. In general, key factors influencing breastfeeding include maternal comfort with breastfeeding combined with lack of comfort with formula feeding.16,17 Personal intentions, medical, social and cultural support for breastfeeding vary among mothers depending on race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status,17–19 education20 and age.18,20 In the preterm infant population, additional issues include maternal and infant health complications,18,21 particular concerns about breast milk insufficiency,22 poor infant latch and weak sucking behavior23 and lack of effective pumping.23

Many NICUs across the country are now offering DM, though published reports of their experiences are lacking. A previous report from another hospital in Ohio found, similar to this study, that offering DM caused formula use to decline precipitously. The report also indicated that MM use increased sharply, from less than 20% before offering donor milk to greater than 80% a year after the program was started24, due to systematic outreach that supported mothers pumping and providing their own milk. In our DM program, mothers were encouraged to express their own breast milk, and we note that 87% of mothers provided their milk at some time, but there was no increase in MM feeding during the program in our hospital NICUs. Human milk feeding has developmental, behavioral and cognitive benefits when compared with formula feeding25, including higher developmental index scores, decreased rates of rehospitalization and significant reduction of NEC.5,26 In 2006, the combined NEC rate in the study hospital NICUs was 13.7 cases of NEC Bell’s stage 2 or 3 per 100 surviving infants after seven DOL. The high rate of NEC in our hospitals led to their commitment to this program, which provided DM to preterm neonates for the first 14 days of hospitalization upon maternal consent and is evidenced by the increase of DM feeding from 8% in 2006 to 77% in 2010–2011. However, NEC rates did not decrease in our NICUs during this DM program. We speculate that this may have been due in part to higher occurrence of NEC as human milk feeding transitioned to formula feeding during their hospital stay. Another important consideration may be that the milk fortifiers used in our NICUs are bovine products. A single randomized, controlled trial found that human milk-based fortification of donor or mother’s own milk to ensure exclusive human milk feeding, reduced rates of NEC compared with the use of any non-human milks or fortifiers.5 The complexities of milk feeding and nutrition in preterm infants warrant, further research to confidently identify the feeding policies that optimize health outcomes. We plan to further investigate the relationship of DM feeding with NEC rates. The primary goal of the Human Milk Project was to increase total human milk consumption (combination of DM and MM) in the first 14 days. Specific interventions used to increase human milk feeding during the course of this program starting in early 2007, included provision of DM, staff education, posters and periodic updates in newsletters describing evidence-based improvements in breastfeeding standards, family education during antenatal consults and postnatally, making breast pumps widely available and focusing on early initiation of pumping. The metric used, total human milk delivered—a single volume that was a composite of milk type over an extended period of time, increased significantly. We were surprised, however, that our quality improvement initiative did not result in a larger proportion of mother’s own milk consumption. Given our results, our ongoing quality improvement initiative has since focused on metrics and evidence-based strategies to improve mothers’ own milk volumes. We have changed the pump initiation goal to within 6 h of birth, whereas it had previously been within 12 h. We are providing greater lactation support, skin to skin holding, and greater access to breast pumps. Our NICUs are now systematically improving mother’s own milk expression and increasing DM feeding to 30 days or 32 weeks corrected gestational age, to cover the postnatal age at onset of most of our NEC cases. We will continue to evaluate outcomes over the next few years.

CONCLUSION

DM was readily accepted among mothers in two hospital NICUs. The use of DM did not decrease the provision of mothers’ own milk, but replaced formula in the first 2 weeks of life. DM is an invaluable option to increase human milk feeding in the preterm population. Indeed, the Surgeon General’s Call to Action indicates that the supply of DM needs to be increased to support the feeding of fragile infants.11 In addition to DM programs, increased efforts are needed to improve the provision of MM to preterm infants in hospital and at discharge, and to evaluate the impact of these combined efforts to reduce the rates of NEC in preterm infant populations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was partially supported by NIH grant funding, as follows: P01 HD13021 (ALM), R01 HD059140 (ALM and KRS), the Medical Student Summer Research Program under T35 DK060444 (ND) and NIH/NCRR 5UL1RR026314. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. We appreciate the expert review of the manuscript by Dr Laurie Nommsen-Rivers and gratefully acknowledge the work of Estelle Fischer, Cathy Grisby, Barbara Alexander, Lenora Jackson, Kristin Kirker, Greg Muthig and Donna Wuest.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.AAP Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. American Academy of Pediatrics. Work group on breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 1997;100:1035–1039. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.6.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quigley MA, Henderson G, Anthony MY, McGuire W. Formula milk versus donor breast milk for feeding preterm or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;17:CD002971. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002971.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schanler RJ. Mother’s own milk, donor human milk, and preterm formulas in the feeding of extremely premature infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:S175–S177. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000302967.83244.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schanler RJ, Shulman RJ, Lau C. Feeding strategies for premature infants: beneficial outcomes of feeding fortified human milk versus preterm formula. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1150–1157. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan S, Schanler RJ, Kim JH, Patel AL, Trawöger R, Kiechl-Kohlendorfer U, et al. An exclusively human milk-based diet is associated with a lower rate of necrotizing enterocolitis than a diet of human milk and bovine milk-based products. J Pediatr. 2010;156:562–567. e561. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porcelli PJ, Weaver RG., Jr The influence of early postnatal nutrition on retinopathy of prematurity in extremely low birth weight infants. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cregan MD, De Mello TR, Kershaw D, McDougall K, Hartmann PE. Initiation of lactation in women after preterm delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:870–877. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orun E, Yalcin SS, Madendag Y, Ustunyurt-Eras Z, Kutluk S, Yurdakok K. Factors associated with breastfeeding initiation time in a baby-friendly hospital. Turk J Pediatr. 2010;52:10–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schanler RJ, Lau C, Hurst NM, Smith EO. Randomized trial of donor human milk versus preterm formula as substitutes for mothers’ own milk in the feeding of extremely premature infants. Pediatrics. 2005;116:400–406. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertino E, Giuliani F, Occhi L, Coscia A, Tonetto P, Marchino F, et al. Benefits of donor human milk for preterm infants: current evidence. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:S9–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [Accessed November 7, 2011];The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding. No. Office of the Surgeon General, 2011. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/topics/breastfeeding/calltoactiontosupportbreastfeeding.pdf. [PubMed]

- 12.Ward L, Auer C, Smith C, Schoettker PJ, Pruett R, Shah NY, et al. The human milk project: a quality improvement initiative to increase human milk consumption in very low birth weight infants. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2012;7:234–240. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2012.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu MC, Lange L, Slusser W, Hamilton J, Halfon N. Provider encouragement of breast-feeding: evidence from a national survey. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:290–295. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wight NE. Donor human milk for preterm infants. J of perinatol. 2001;21:249–254. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganapathy V, Hay JW, Kim JH. Costs of necrotizing enterocolitis and cost-effectiveness of exclusively human milk-based products in feeding extremely premature infants. Breastfeeding medicine. 2012;7:29–37. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2011.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nommsen-Rivers LA, Chantry CJ, Cohen RJ, Dewey KG. Comfort with the idea of formula feeding helps explain ethnic disparity in breastfeeding intentions among expectant first-time mothers. Breastfeed Med. 2010;5:25–33. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2009.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guerrero ML, Morrow RC, Calva JJ, Ortega-Gallegos H, Weller SC, Ruiz-Palacios GM, et al. Rapid ethnographic assessment of breastfeeding practices in periurban Mexico City. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:323–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HC, Gould JB. Factors influencing breast milk versus formula feeding at discharge for very low birth weight infants in California. J Pediatr. 2009;155:657–662. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pineda RG. Predictors of breastfeeding and breastmilk feeding among very low birth weight infants. Breastfeeding medicine. 2011;6:15–19. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2010.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostlund A, Nordstrom M, Dykes F, Flacking R. Breastfeeding in preterm and term twins--maternal factors associated with early cessation: a population-based study. J of hum lactat. 2010;26:235–241. doi: 10.1177/0890334409359627. quiz 327-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McInnes RJ, Shepherd AJ, Cheyne H, Niven C. Infant feeding in the neonatal unit. Matern Child Nutr. 2010;6:306–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2009.00210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathur NB, Dhingra D. Perceived breast milk insufficiency in mothers of neonates hospitalized in neonatal intensive care unit. Indian J Pediatr. 2009;76:1003–1006. doi: 10.1007/s12098-009-0204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meier PP, Engstrom JL, Patel AL, Jegier BJ, Bruns NE. Improving the use of human milk during and after the NICU stay. Clin Perinatol. 2010;37:217–245. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valentine CJ, Morrow G, Morrow AL. Division of Dockets Management (HFA-305) FDA (eds) FDA; Rockville, MD: 2010. Promoting Pasteurized Donor Human Milk Use in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) as an Adjunct to Care and to Prevent Necrotizing Enterocolitis and shorten length of Stay; p. 389. 20852. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/PediatricAdvisoryCommittee/UCM251799.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vohr BR, Poindexter BB, Dusick AM, McKinley LT, Wright LL, Langer JC, et al. Beneficial effects of breast milk in the neonatal intensive care unit on the developmental outcome of extremely low birth weight infants at 18 months of age. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e115–e123. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montjaux-Regis N, Cristini C, Arnaud C, Glorieux I, Vanpee M, Casper C. Improved growth of preterm infants receiving mother’s own raw milk compared with pasteurized donor milk. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:1548–1554. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]