Abstract

Background

This community-based participatory research was conducted to provide a preliminary understanding of how Afghan women in Northern California view their breast health.

Methods

Results were based on demographics and in-depth semi-structured interviews conducted with 53 non-English-speaking first-generation immigrant Muslim Afghan women 40 years and older.

Results

Findings showed low levels of knowledge and awareness about breast cancer and low utilization of early-detection examinations for breast cancer among participants.

Conclusions

The findings also suggest a significant need for a community-based breast health education program that recognizes the unique social, cultural, and religious dynamics of the Muslim Afghan community.

Background

The ongoing humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan has resulted in a sharp increase in the number of Afghan immigrants in the USA; it is currently estimated that there are more than 60,000 Afghans in the USA. California's Bay Area is home to the largest Afghan community in the USA [1]. In 2000, about one-third of United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees classified ‘Women at Risk’ (WAR) cases were widows, but by 2001, the number increased to more than half. Like other Afghan refugees, WAR cases have spent an average of 4 years in refugee camps [2,3]. Studies on Afghans in Northern California show that this community has coped with a number of stressors that negatively affect their health and psychological well-being. Identified problems include language and communication barriers, economic and occupational problems, healthcare access, and family and children's issues [4,5].

Despite evidence that early detection leads to reductions in breast cancer mortality, early-detection methods continue to be underused by minority women—particularly new immigrants. Although research indicates that breast cancer incidence is lower among ethnic minority women than among White women in the USA, ethnic minority women also have lower rates of early detection and survival [6,7]. Studies indicate that lower rates of breast and cervical cancer screening, lower socio-economic status, and lack of or inadequate health insurance contribute to ethnic minority women's higher rate of breast and cervical cancer mortality [8–13].

Previous studies of immigrant women in the USA indicate high risk for health problems due to a variety of reasons including lack of access to health services, less education, language barriers, men's gatekeeping, social isolation, and cultural and religious barriers [5].

Fatalism is another factor analyzed as a psychosocial barrier that decreases screening compliance. Fatalism is the belief that situations, such as illnesses or tragic events, happen because of a higher power (such as God), or they are just meant to happen and cannot be avoided. Fatalistic views see illness as divinely ordained (particularly among Catholics), and women with fatalistic belief prefer traditional health practices as a first form of treatment. Some women, facing the prospect of breast cancer, may feel powerless; they reason that this disease was ‘meant’ to happen to them [8–13].

For immigrant women to receive screening, evidence indicates that cultural and social impediments must be addressed. Outreach is particularly essential as women who migrate from countries with low breast cancer surveillance have lower awareness of the importance of screening [14–16]. Immigrant Muslim women in the USA are at risk of poor health outcomes because of factors such as gender roles, social isolation, discrimination, emotional and mental stressors related to war or other political issues, language barriers, and lack of knowledge of the healthcare system [17,18]. They are also at higher risk for mental and physical health problems than men [18]. Muslim women in the USA fulfill multiple roles as wives, mothers, workers outside the home, and sometimes students while trying to preserve their culture and religion. The immigration experience can be challenging and difficult to adjust to especially for older immigrants. Such complex socio-cultural and economic demands may result in lack of self-care and health negligence[18].

No statistics are available on the incidence and prevalence of breast cancer among Muslim women in the USA; available data show low rates of healthcare utilization, especially breast and cervical health care [19–22]. Underwood and colleagues reported that religious beliefs and cultural values and attitudes had an important impact on breast cancer screening behaviors of Muslim women even if they understood its importance [21]. Therefore, cultural and religious factors including being modest, having a sense of privacy, feeling shy about healthcare personnel, not consulting the physician early, and not touching one's own body may contribute to higher cancer mortality rates [7,20–22].

With the sharp increase in the number of immigrants from low-resource countries and the current trend in cultural diversity that is significantly changing the ethnic mix of the population in the USA, it is becoming increasingly essential to identify factors that place immigrant women at high risk for advanced-stage breast cancer at diagnosis [23–25]. This supports the urgent need to explore the beliefs, knowledge, attitudes, information sources, and health behaviors of the Afghan immigrant population in regard to breast health care and early breast cancer detection.

Using community-based participatory research [26], we designed this study to work with the Afghan community to identify what immigrant Afghan women believe to be their greatest concerns and barriers to receiving breast health care, to determine their knowledge, attitudes, and sources of information regarding breast health care, and to identify specific religious and/or social elements that act as barriers for immigrant Muslim Afghan women to seek care. Although this work focused on a specific population (99.9% of the Afghan population identify as Muslim; therefore, the terms Muslim women or Afghan women may be used interchangeably in this paper), findings may be broadly applicable.

Theoretical/conceptual framework

Cultural explanatory models (CEMs) focus on the socio-cultural context and its impact on knowledge, attitudes, and behavior relating to care. The CEM framework provides a deeper understanding of health-seeking behavior by focusing on the socio-cultural context and its impact on Muslim women's knowledge, attitudes, and behavior relating to cervical and breast cancer screening. Women's CEMs are a product of their social, cultural, and religious context, and an understanding of women's CEMs is necessary to identify the barriers to utilization of breast healthcare services among minority populations, such as Afghan refugees. According to this model, culture is understood as a particular group's values, beliefs, norms, and life practices that are learned, shared, and handed down. People generate idea systems of health and illness that they learn by interaction with others of their own culture, especially close family members, friends, and community members. Such CEMs not only shape people's perception and experience of an illness but also influence their decisions about screening, when to seek medical advice, and which treatments to accept [27]. CEMs of breast cancer screening specify three key components that influence health-seeking behaviors: (i) socio-economic factors; (ii) the influence of community and social networks; and (iii) the impact of cultural/religious beliefs [27].

Secondarily, we worked with Chatman's [28] theory of information seeking in the small world of in-groups. In Afghan and other collectivist cultures, minority women's CEMs are particularly important to understand because ‘most people's social behavior is largely determined by goals, attitudes, and values that are shared with some collectivity’ and individual identity is primarily recognized as belonging to a group rather than being a separate entity [29]. In Afghan society, family life is central to culture with the in-group, consisting of kinship ties among extended family members with whom they socialize almost exclusively throughout their lives [30].

Methods

Alameda County California is home to the largest population of Afghan refugees in the USA. With the use of community-based participatory research, this project was a collaboration between the Afghan Coalition located at the Fremont Resource Center in the Southern Alameda County of California and the School of Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley. The Afghan Coalition established in 1996 is a 501(c) (3) non-profit community in the Bay Area.

Study population and sampling

Interviews were conducted with 53 non-English-speaking first-generation immigrant Muslim Afghan women 40 years and older with no history of breast cancer. Maximum variation purposive sampling, the process of deliberately selecting a heterogeneous sample and observing commonalities in their experiences, was used. With input from our Community Advisory Board, participants were recruited by community members and their social networks. Efforts were made to ensure that the sample was diverse in age, length of residency, socio-economic background, and tribal and regional affiliation.

To recruit participants, community members visited Afghan community centers, local mosques, women's gatherings, and social circles. They discussed the purpose of the project, the inclusion criteria, and the importance of their participation. Program announcements about the project were made on local Afghan community TV and other local news outlets.

The mean age of the participants was 46 years (range = 40–87 years). The participants all identified as Muslim, representative of the greater population, which is 99.9% Muslim. The majority of the women considered themselves forced immigrants with the mean length of residence in the USA of 16 years (range = 1–28 years). Table 1 provides a demographic description of the participants.

Table 1. Participant demographic characteristics (N = 53).

| Percent of women | |

|---|---|

| Marital status (%) | |

| Married | 65 |

| Widowed | 35 |

| Employed (%) | 10 |

| English proficiency (%) | |

| Very limited | 40 |

| No English at all | 30 |

| Formal education (%) | |

| >12 years of education | 12 |

| No formal education | 40 |

| Annual household income (%) | |

| Less than $50,000 | 99 |

| Has health insurance | 77 |

Data collection

An interview guide, validated by the Community Advisory Board, was translated into Farsi/Dari and back-translated into English. It included semi-structured questions to stimulate participants' spontaneity and expansiveness in thinking and responding.

Once the pilot project was approved by UC Berkeley's Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, trained bilingual female health navigators started conducting the interviews. Interviewers were experienced bilingual/bicultural women from the Afghan community with more than 25 years of combined experience working in their community. Interviews were carried out between November 2007 and May 2008. Interviews were in person and face to face in a private room and lasted 1–3 h. The interviews began with a warm welcome; tea and refreshments were offered to the participants according to Afghan custom, followed by an introduction about the purpose and importance of the study and a review of the guidelines for participation. Written informed consent was obtained. All interviews were in Farsi/Dari and recorded on audiotape. Notes were taken to document additional comments. Each participant was provided with a gift at the conclusion of the interview.

Taped interviews were transcribed in Farsi and translated into English by a bilingual Afghan American with a Ph.D. in Anthropology. A second bilingual researcher was closely involved in the translation to check the quality and accuracy of translation, making sure that appropriate vocabulary and syntax were used. Verbatim transcripts of audiotapes and interviewer notes served as the primary data for the analyses. To ensure accuracy, the transcripts were rechecked against audiotapes and corrected to produce a hard copy for the preliminary analysis.

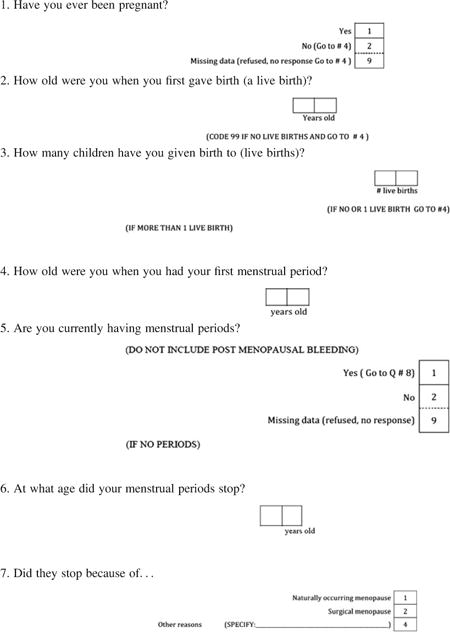

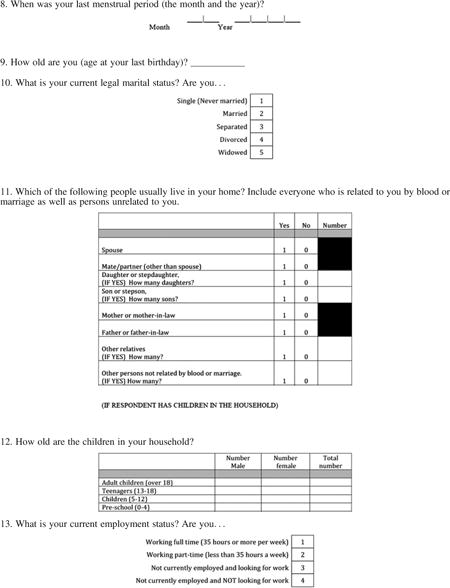

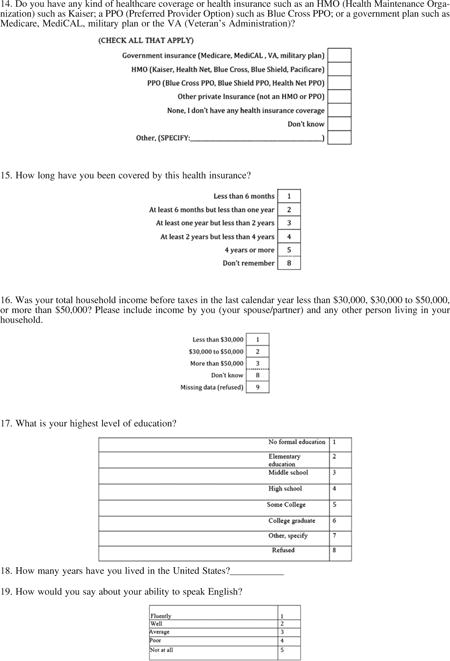

Measures

The semi-structured in-depth interviews covered perceptions of the influence of religious and cultural beliefs on breast care, attitudes, and knowledge towards breast cancer, perceptions of the information sources of their knowledge and attitudes, and perceptions of the importance of receiving breast health care as well as the barriers to breast cancer screening and preferred formats of information about screening. The interview started with a broad opening question: ‘What comes to your mind when you hear about health?’ Probes and follow-up questions were used to clarify responses and increase richness of responses. Socio-demographic, health services utilization data, and family history of breast cancer were also collected (Appendix A).

Analysis

The resulting transcripts were analyzed using both qualitative and quantitative methods. ATLAS.tL was used for the management, evaluation, and visualization of qualitative data. Open coding identified approximately 20 themes and formulated a list of code categories, including their properties and dimensional locations. Codes and categories were sorted, compared, and contrasted until they were ‘saturated’. Non-structured feedback sessions formatted as a focus group with three interviewers and members of the Community Advisory Board (12 members) were conducted after preliminary analysis to ensure the themes were recognized as accurate representations of their views and experiences, and respondent's feedback was incorporated into conclusions. The scientific members of the team also met with the Community Advisory Board throughout the process to discuss interpretations and come to consensus regarding the meaning of the findings.

Results

Among the participants, 37.7% reported having a first-degree relative who had breast cancer, 28.3% had a clinical breast examination less than 2 years ago, and 41% reported never having a clinical breast examination. Among the 65.9% who reported having had a mammogram, more than half reported having had one more than 2 years ago, and almost 34% reported never having had a mammogram (Table 2).

Table 2. Breast cancer screening practices (N = 53).

| Percent of women | |

|---|---|

| Clinical breast exam (%) | |

| Less than 2 years ago | 28.3 |

| More than 2 years ago | 30.2 |

| Never had one | 41.0 |

| Mammogram (%) | |

| Ever had a mammogram | 65.9 |

| More than 2 years ago | 50.1 |

| Never had one | 34.1 |

Following analysis and saturation of thematic material, three major themes, with result and sub-categories, emerged:

-

Greatest concerns and barriers to receiving breast health care.

-

Afghan culture and family structure:

Almost all participant's responses regarding the Afghan family structure and gender roles were indicative of the conservative Afghan patriarchal tribal practices. One woman explained how male family members, particularly husbands, had a substantial influence on the women's screening decisions: ‘I don't know how to drive and can't read anything in English, so I need to have someone take me places and my husband is the one that usually does’.

Forty eight (90%) of the participants indicated that they were dependent on family members' support, particularly their husbands or male relatives, in scheduling appointments, providing transportation, and interpreting and providing general care during health service.

Most women expressed that men's gatekeeping roles regarding interaction outside of the home, together with the traditional understanding and expectation of men as the head of the household and caretaker of the family had a profound effect on their decision-making power regarding their healthcare needs.“In most Afghan family the man makes the important decisions about all things and how to deal with problems, even health problems.”“Husbands wouldn't tell their wives to go to the doctor and get examined.” -

Access barriers often related to limited English proficiency, low health literacy, transportation, and communication:

Participants frequently reported that major access barriers to breast cancer screening were difficulty in understanding and navigating the healthcare system, transportation difficulties (including lack of transportation). Forty (75%) of the participants reported language difficulties, lack of interpreter services, and problems in scheduling appointments as major barrier to healthcare access. They also commented on the lack of translated material in Farsi/Dari and Farsi/Dari-speaking interpreters at medical centers and clinics and questioned why more Farsi/Dari resources were not available.“I can't speak or read English, so is difficult to call the doctor.”“If someone who spoke English was with me, I would go, otherwise I wouldn't.”“I have to ask my son to drive me to the clinic, he is very busy and Idon't want to bother him.” -

Concerns regarding healthcare providers:

In terms of healthcare provider needs, ethnicity and religion of the provider were not important to the majority of the women; more important was the ability to communicate with their provider: ‘. . .to listen to a woman and to let her tell you what is bothering her. To not just ignore her and make her feel small’ and ‘. . .to be gentle, and caring’ and ‘Talk to her, explain everything and speak in Dari’.

Female modesty was an important concern and value for the vast majority of the women, stemming from both religious and cultural traditions. Although some of the participants acknowledged that Islam does not prevent Muslim women from receiving treatment from male doctors, as explained by one woman: ‘Islam doesn't say we can't go to a man doctor but I am Afghan and my culture says it's not right’. Almost all women expressed more comfort with breast cancer screening and gynecological exams with a female provider. The women believed that Afghan Muslim women should conform to the prevailing tradition of cultural privacy and modesty regarding their body when it comes to breast and gynecological exams. This was voiced by one of the participants: ‘As an Afghan woman I feel better with a female doctor’. Some of the women stated that some husbands may also be uncomfortable with it. One of the women addressed this issue by saying, ‘Some husbands don't want another man to touch his wife’.

-

Women's mammography experiences:

Women with positive mammography experience(s) commented that the technologist explained the procedure in ‘plain language’ before conducting the exam. They reported that instructions during the process also helped reduce discomfort during the exam, staff's ‘friendliness and good attitude’ helped them feel relaxed. One woman expressed her frustration with a negative mammography experience by stating, ‘I had no idea what was going to happen’ and ‘felt rushed and did not know what to expect’. Prolonged delays to receive exam results were a major point of stress.

-

-

Women's knowledge, attitudes, and sources of information regarding breast health care.

-

Lack of knowledge about breast cancer and screening guidelines:

Analysis of the findings indicated a very low level of knowledge about breast cancer, lack of awareness of breast cancer symptoms, particularly non-lump symptoms, risk factors for breast cancer, and screening procedures and guidelines. The following are some of the statements made about cancer by the participants:“It's an infection that enters the body, and can't be washed away.”“. . .a lump probably from the dirty blood.”“I don't know why. The pollution, the chemicals in food, stress; everything.”“If you think bad things like cancer you will get it.”“Breast cancer is due to damage of the breast and may be contagious.”Many participants believed mammography to be a diagnostic test rather than a screening test, with most viewing it as a test for cancer or infections rather than for cell abnormalities. One woman stated, ‘If my doctor sends me for mammography it tells me I have the infection in my breasts or something’.

Thirty seven (70%) of the participants reported that culturally and linguistically appropriate breast health education information and programs are not available to them. Many participants said language difficulties, low educational attainment, low health literacy, and social isolation resulted in significant challenges in accessing the health services: ‘We can't read’ and ‘. . .we never went to school’.“Many women feel intimidated when they see a lot of writing.”“Ignorance and lack of information in Afghan language.”“. . .because in our culture it's not good to talk about this disease.”“You can't learn anything when you sit home everyday.”One of the most striking themes expressed by the women was their strong desire to discuss issues related to breast health and screening. The majority of the participants agreed that it was very important to receive information about breast cancer to raise awareness and to provide explanations about what the disease is and how it can be detected early. One participant said: ‘Women in our community don't have information about breast cancer’ and ‘. . .Give us information and educate our community about this illness and how to find it early’. Another woman stated, ‘We need to learn about this subject and attend some classes to learn about it and to know about the places and the services available’.

-

Preferred sources of breast health information:

Women expressed strong preference for educational sources, tools, and formats with visual and oral components through doctors and community health educators: ‘I think written information is not as important as visual information because there is a large number of illiterate women’. They were also enthusiastic about small-group educational sessions, where information is shared in small groups and passed through word of mouth, ‘dastan’.

Women suggested these formats: videos or programs shown on Afghan TV, visual components incorporated into all educational material, and interactive small-group educational sessions.“Personally I don't like it written because I was given pamphlets before but I didn't look at them because I prefer to get the information face-to-face and with other women like me around and be able to ask as many questions as I want.”“Showing such programs on Afghan TV is a good way to educate Afghans.”Finally, many women suggested brochures and flyers in Farsi/Dari language accessible to women with low health literacy. Some commented that even as women who could read and speak English, they find it much more accessible if they received the information in their own language. A participant explained, ‘I speak English but not too well so I rather receive information in my language to be able to understand every word, especially for an important issue like this’.

-

-

Women's perceptions of health and religious elements in discussing breast health issues.

-

Perceptions of health:

Women had positive feelings about taking care of their health. They expressed that goodhealth was an important indicator of ‘good relations with family and community’. Health was not regarded as the absence of disease but as their ability to perform their duties within their families. One woman stated, ‘When a woman is healthy she can take better care of her family’. Women strongly identified with both the nuclear and extended families. They considered a person to be a social being within a communal context, whereas an individual is one who is detached from the community. A 70-year-old participant explained this concept by saying, ‘In the Afghan culture a person's connection to their family is like a finger on your hand’.

Most women acknowledged the needs of the family over their own and expressed that they were more concerned about the well-being of their children and family, hence paying less attention to her own health. Such statements were frequently made:“Most of women don't have time for themselves and they sacrifice all their life to take care of their families.”“A good mother looks after the family first.”The majority of women believed health to be a blessing from God (Allah) and viewed Allahas the ultimate healer and their body as a gift that ‘they should take careof’. The element of ‘Imaan’, belief or faith, was mentioned many times.“We accept God's will while trying to optimize our behavior. We do whatwe can, what is in our control and power, you know, and have faith.”Illness was seen as a divine test, but they also held themselves responsible for doing everything they can to overcome illness, including seeking medical care and treatment. The women commented that this responsibility originated from their ‘Imaan’ and that according to the Quran, life is a sacred trust from God and must be respected and protected with great care.“This body is from God and we are responsible to take care of it.”“Khoda (God in Farsi/Dari) does not say stay at home and let disease kill you you . . . I should do something to get my health back.”Participants commented on Afghan practices that give guardianship and control of men over women as a reflection of traditional cultural practices and not subscribed by Islam, separating religious effects from those attributed to culture. One woman expressed her distress by stating, ‘Afghan women were told that women are for the home only and she should sit at home, serve her husband and children . . . she has no right to go out from home . . . this has nothing to do with Islam’. Women also believed that Islam values learning and considers it a sacred duty for both men and women. One woman commented, ‘In Islam learning is equal for both men and women . . . so why do we have so many illiterates, so many women, the cultural fanatics bring these issues, they will kill her but do not allow her to go to the hospital’.

-

Discussion

Immigrant women face a multitude of barriers in breast cancer screening. Although a number of barriers pertain to all immigrant women, variation among groups by country or region of origin demands close examination to determine and address unique concerns. The present study provides an insight into breast health-seeking behaviors of Muslim immigrant Afghan women, which are characterized by unique socio-cultural and religious factors.

For the breast cancer screening needs and concerns of this population to be met, their cultural beliefs, knowledge, barriers, and healthcare practices must be understood.

Our research did not reveal religious fatalism regarding health; rather, our participants viewed Islam as requiring a pro-active approach to health and health care. We considered this finding very interesting and contrary to the fatalism associated with lower screening rates among other minority groups [31–33]. Religious beliefs for the women in this study encouraged educating one's self and prioritizing both individual and family health. Islamic concepts are part of the culture of these women and are expressed in a variety of ways through their daily life. This is in contrast to previous research in the area of fatalism among other Muslim immigrant communities, which shows fatalism to be a major barrier to screening. For example, a study in New York City, which has one of the highest Muslim Arab immigrant population in the USA, used focus groups on the topic of cancer causes and health-seeking behavior with immigrants from Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Yemen. The study found a strong fatalistic attitude among Arab men and women in the cause, prevention, and treatment of cancer [34]. Women's replies related to cancer prevention included, ‘God only knows . . . I think cancer is from God. It has no reasons. If there were causes, I would go [get screened]’ (p. 434). Similarly, when the women's group discussed cancer treatment, the over-whelming theme was that God is the ultimate healer and also the main source for comfort and consolation. In addition, both men and women had fatalistic thoughts regarding prognosis once diagnosed, which revealed an overwhelmingly pessimistic and external sense of control [34].

Both Islamic and Afghan concepts of modesty have key relevancy in the health care of the participating women. Some believe that rules of Islam prohibit female nudity and self-exposure in front of men other than one's husband. For example, some reasons for not obtaining or delaying breast exams among Muslim women may include the importance placed on observing modesty and maintaining privacy by covering their bodies or their hair, especially among persons outside the immediate family, which would include male healthcare providers. Thus, breast exams performed by male physicians, surgeons, or radiology technologists makes breast examinations especially difficult among some religious Muslim women [20,21]. So despite their knowledge of the benefits of breast cancer screening, Muslim women may not participate in breast cancer screening programs that are not structured in a manner that is consistent with their cultural traditions and religious beliefs [20,21].

The role and responsibility of individuals based on their gender and seniority and position in the family have important implications in the power structure of the Afghan family; therefore, any intervention must focus on women within the context of the family and community. Among traditional families, women rely heavily on their husbands or male relatives for taking them to the doctor and scheduling screening exams. Woman's role as the nurturer of the family and the belief that attending to the family's needs comes first can also complicate a woman's need to take initiative in obtaining medical care. Illness can be perceived as a deficiency in the woman, and she would want to protect herself socially by minimizing her use of health care [17,18].

In terms of barriers to breast cancer screening, this study identified lack of knowledge as a major barrier issue. This was exacerbated by women's limited English proficiency, a problem that is particularly prevalent among Afghan immigrant women. Most first-generation Afghan women in the USA are forced refugees escaping war, and many would have had a disrupted education and, thus, struggle with literacy in both their own language and English [2–4].

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. First, the sample size in this pilot study was relatively small and may not represent all Afghan ethnic groups and cultures. An increased sample size would allow for information to be generalized beyond the target population. Second, this study focused only on first-generation immigrant Muslim Afghan women, and the findings will be less generalizable to subsequent generations whose command of the language and understanding of screening are likely to be improved.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, there have been no published studies exploring the breast health behaviors and needs of immigrant Afghan women in the USA. Therefore, despite these limitations, this study raises a number of important issues that have implications for breast cancer screening delivery among this population. The findings underline the importance of healthcare staff being trained in cultural and religious awareness. This study also indicates that further research and development of a breast health education program requires several things. First, the program works within the entire Afghan community, particularly including the men, and that community women be trained to serve as community educators; second, that information be presented in a variety of media, including the local Afghan language television station, word-of-mouth community meetings, and print materials that contain a minimum of text; and finally, that any work situate breast health within the context of family and community health using positive Islamic messages.

Purposive sampling ensured that a diversity of experiences and attitudes were explored. Furthermore, the use of Afghan community members to recruit and interview participants helped to overcome language and cultural differences. In addition, the use of qualitative methods and the data collected recognized Afghan's strong preference for ‘oral’, which enabled the views of the women with limited or no literacy to be heard.

Our data show that Afghan immigrant women have low rates of breast cancer screening. Low rates of screening have important implications for stage at diagnosis of breast cancer, putting the women in our study at greater risk for late-stage diagnosis; the study also suggests a strong family history of breast cancer among this group (37.7% reported having a first-degree relative who had breast cancer).

Our findings are valuable in beginning to identify the unique complexities in the socio-cultural backgrounds of the rapidly growing Muslim women population in Northern California, which may hinder their access to breast healthcare services. Our future research goals include using the findings from this project for the adaptation and/or expansion of a culturally appropriate evidence-based intervention program to increase breast health care and early detection among Afghan women living in Northern California. In the future, portions of such a program may be transferable to other Muslim communities in the country. Future studies that examine the process of risk assessment among Afghan women who have a family history of breast cancer are also recommended, incorporating measures to assess the influence of healthcare providers, culture (how kinship is defined in different cultures), religion, social networks, and the family.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant from the California Breast Cancer Research Program (CBCRP) and by an NCI (1 U54 CA153506) award.

Appendix A: Interview guide and survey

Interview guide for open-ended questions

-

What comes to your mind when you hear about ‘health’?

Probe: How important is it for you to stay healthy?

Probe: What would you do to stay healthy?

-

Who do you talk to when you have a problem with your health?

Probe: doctor, nurse, other healthcare provider, husband, friend, mother, sister, other family member

-

When do you go to the doctor (or nurse or other healthcare provider)?

Probe: Do you only go to the doctor (or nurse or other healthcare provider) when you have a specific problem about your health?

Probe: Do you ever visit the doctor (or nurse or other healthcare provider) when you are feeling well, like for a mammogram or flu shot or a general check-up?

In the last year, have you visited the doctor (or nurse or other healthcare provider) when you were feeling well? What did you go see the doctor (or nurse or other healthcare provider) for?

-

Do you need to ask someone if it's okay for you to go see the doctor or nurse or other health care provider?

Probe: Who do you ask?

Probe: What do you ask them?

-

Do you need to ask someone if it's okay for you to get medical or health care, like taking medicine, getting an X-ray or mammogram, or agreeing to surgery?

Probe: Who do you ask?

Probe: What do you ask them?

Is there a specific doctor (or nurse or other healthcare provider) or specific place you visit, like a hospital or clinic, when you need health care? Who do you see? Where do you go?

-

Are there reasons/things that make it difficult for you to visit a doctor? If so what are they?

(Probes: too busy, family responsibilities, long waiting time, communication problems, transportation, etc.)

-

Imagine that you, your mother, or sister, needed to find a new healthcare provider (doctor or nurse). What important things would you look for in a new healthcare provider?

Probe: language, ethnicity, gender, cost, convenience (location, hours), religion, quality of care, other

-

How important is it to you that your doctor (or nurse or other healthcare provider) is male or female?

-

Probe: Are there some health services that it doesn't really matter to you if you see a male or female provider?

Probe: dental exam, physical exam, breast exam, gynecological exam?

-

-

Tell me about the times that you would prefer to visit a female doctor (or nurse or other health care provider) rather than a male doctor.

Probe: dental exam, physical exam, breast exam, gynecological exam

-

Are there some health care services that you would refuse to get from a male doctor (or nurse or other health care provider)? What are they? Why?

Probe: dental exam, physical exam, breast exam, gynecological exam

Are there any medical/health services that you, or other Afghan women, would most likely not get at all because of cultural or religious reasons? What are they?

Have you ever received a mammogram? (If no, skip to question 14.)

-

(If yes) Think back to the first time you received a mammogram describe step by step what happened and how you felt, starting with how you decided to get a mammogram and telling the whole story of getting the mammogram and receiving the test results.

Probe: What were you thinking at the time? Feeling?

Probe: What was helpful to you at this time? (What someone said, what you thought, the arrangement of the room, praying, etc.)

Probe: What was hurtful to you or a barrier to you?

Probe: Were there any good or bad results from this experience for you?

Probe: What should be changed in the future to make the experience better?

Have you ever received a breast exam by a doctor or nurse? (If no, skip to question 16).

-

(If yes) Think back to the first time you received a breast exam by a doctor or nurse and describe step by step what happened and how you felt.

Probe: What were you thinking at the time? Feeling?

Probe: What was helpful to you at this time? (What the person said, what you thought, the arrangement of the gown, praying, etc.)

Probe: What was hurtful to you or a barrier to you?

Probe: Were there any good or bad results from this experience for you?

Probe: What should be changed in the future to make the experience better?

-

Do you have any female health problems?

Probe: More specifically, are you concerned about breast health?

-

How do you know if you have healthy breasts? (If they don't know, skip to question 19)

Probe: What do you do to take care of your breasts, if anything?

-

Where did you learn about how to care for the health of your breasts?

Probe: Did someone tell you? What was the source? (Mom, sister, husband, co-worker, doctor, TV commercial, newspaper, etc.)

-

What would be the best way for Afghan women to learn (or learn more) about breast health care?

Probe: Who should tell women? (Mom, sister, husband, co-worker, doctor, TV commercial, newspaper, etc.)

Probe: Why would you want women to learn from _______________?

-

What do you think about when you hear the words ‘breast cancer’?

Probe: Do you know how women get breast cancer? Please explain.

What can you do to protect yourself from breast cancer?

-

Have you heard about breast cancer screening guidelines?

Probe: What do the words ‘breast cancer screening guidelines’ mean to you?

Probe: How did you learn about these guidelines?

Probe: Did someone tell you how to protect yourself? Who?

Probe: When did you learn this information?

Do you have any questions about breast health care? If so, what are they?

Survey

References

- 1.Afghan Coalition. Annual report. 2006. [Accessed October 2006]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poureslami IM, MacLean DR, Spiegel J, Yassi A. Sociocultural, environmental, and health challenges facing women and children living near the borders between Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan (AIP region) Med Gen Med. 2004;6(3):51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNHCR. Afghanistan. UNHCR Center for Documentation and Research Publications; Geneva: 2004. Background Paper On Refugees And Asylum Seekers From; pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipson JG, Hosseini MA, Kabir S, Edmonston F. Health issues among Afghan women in California. Health Care Women Int. 1996;16:279–286. doi: 10.1080/07399339509516181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipson JG, Omidan PA. Afghan refugee issues in the U.S. social environment. West J Nurs Res. 1997;19(1):110–126. doi: 10.1177/019394599701900108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rashidi A, Rajaram S. Middle Eastern Islamic women and breast self-examination. Cancer Nurs. 2000;23:64–71. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200002000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juon HS, Kim MT, Shankar S, Han W. Predictors of adherence to screening mammography among Korean American women. Prev Med. 2004;39:474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goel MS, Burns RB, Phillips RS, Davis RB, Ngo-Metzger Q, McCarthy EP. Trends in breast conserving surgery among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, 1992–2000. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:604–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanjasiri SP, Kagawa-Singer M, Foo MA, et al. Breast cancer screening among Hmong women in California. J Cancer Educ. 2001;16:50–54. doi: 10.1080/08858190109528725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith-Bindman R, Migliorettie DL, Lurie N, et al. Does utilization of screening mammography explain racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer? Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:541–553. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-8-200604180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su X, Grace XM, Seals B, Tan Y, Hausman A. Breast cancer early detection among Chinese women in the Philadelphia area. J Womens Health. 2006;15:507–519. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu T, West B, Chen YW, Hergert C. Health beliefs and practices related to breast cancer screening in Filipino, Chinese, and Asian-Indian women. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.John M, Phipps A, Davis A, Koo J. Migration history, acculturation, and breast cancer risk in Hispanic women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2905–2913. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hedeen AN, White E. Breast cancer size and stage in Hispanic American women, by birthplace: 1992–1995. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:122–125. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.1.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedeen AN, White E, Taylor V. Ethnicity and birthplace in relation to tumor size and stage in Asian American women with breast cancer. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1248–1252. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lattery SC, Meleis A, Lipson J, Solomon M, Omidian P. Assessing Arab-American health care needs. Soc Sci Med. 1989;29:877–883. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norris A, Aroian K. Avoidance symptoms and assessment of post traumatic stress disorder in Arab immigrant women. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21:471–478. doi: 10.1002/jts.20363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain R, Mills P, Patel A. Cancer incidence in the south Asian population of California, 1988–2000. J Carcinog. 2005;4(21):1477–3163. doi: 10.1186/1477-3163-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matin M, LeBaron S. Attitudes toward cervical cancer screening among Muslim women: a pilot study. J Womens Health. 2004;39:63. doi: 10.1300/J013v39n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Underwood M, Shaikha L, Bakr D. Veiled yet vulnerable Breast cancer screening and the Muslim way of life. Cancer Pract. 1999;7(6):285–290. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.76004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan S, Gillani J, Nasreen S, Zai S. Cancer in North West Pakistan and Afghan refugees. J Pak Med Assoc. 1997;47(4):122–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juon HS, Seo YJ, Kim MT. Breast and cervical cancer screening among Korean American elderly women. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2002;6:228–235. doi: 10.1054/ejon.2002.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee YH, Lee E, Shin K, Song M. A comparative study of Korean and Korean-American women in their health beliefs related to breast cancer and the performance of breast self examination. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2004;34:307–314. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2004.34.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lew AA, Moskowitz JM, Ngo L, et al. Effect of provider status on preventive screening among Korean-American women in Alameda County. California Prev Med. 2003;36:141–149. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Israel B, Eng E, Schulz A. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publication; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajaram S, Rashidi A. Minority women and breast cancer screening: the role of cultural explanatory models. Prev Med. 1998;27:757.26. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chatman EA. The impoverished life-world of outsiders. J Am Soc Inf Sci. 1996;47(3):193–206. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Triandis HC. Collectivism v. individualism: a reconceptualisation of a basic concept in cross-cultural social psychology. In: Gudykunst WB, Kim YY, editors. Readings on Communicating with Strangers. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Inc; 1992. pp. 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipson JG, Omidian P. Health issues of Afghan refugees in California. West J Med. 1992;157(3):271–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talber P. The Relationship of Fear and Fatalism with Breast Cancer Screening Among a Selected Target Population of African American Middle Class Women. J Soc Behav Health Sci. 2008;2(1):96–110. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frisby M. Message of hope: health communication strategies that address barriers preventing Black women from screening for breast cancer. J Black Stud. 2002;32(5):489–505. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Straughan PT, Seow A. Fatalism reconceptualized: a concept to predict health screening behavior. J Gend Cult Health. 1998;3(2):85–100. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shah SM, Ayash C, Pharaon NA, Gany FM. Arab American immigrants in New York: health care and cancer knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10(5):429–436. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]