Abstract

Background

This paper analyzes how different types of Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) knowledge influences condom use across the sexes.

Methods

The empirical work was based on a household survey conducted among 1979 households of a representative group of stallholders in Lagos, Nigeria in 2008. Condom use during last sexual intercourse was analyzed using a multivariate model corrected for clustering effects. The data included questions on socioeconomic characteristics, knowledge of the existence of HIV, HIV prevention, HIV stigma, intended pregnancy, and risk perceptions of engaging in unprotected sex.

Results

A large HIV knowledge gap between males and females was observed. Across the sexes, different types of knowledge are important in condom use. Low-risk perceptions of engaging in unprotected sex and not knowing that condoms prevent HIV infection appear to be the best predictors for risky sexual behavior among men. For females, stigma leads to lower condom use. Obviously, lack of knowledge on where condoms are available (9.4% and 29.1% of male and female respondents, respectively) reduced condom use in both males and females.

Conclusion

The results call for programmatic approaches to differentiate between males and females in the focus of HIV prevention campaigns. Moreover, the high predictive power of high-risk perceptions of engaging in unprotected sex (while correcting for other HIV knowledge indicators) calls for further exploration on how to influence these risk perceptions in HIV prevention programs.

Keywords: Africa, condom, males, females, HIV/AIDS, knowledge, prevention, risk perception

Introduction

The first line of attack in the battle to slow down new Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections has been campaigns to improve general knowledge on HIV. Local and international interventions, including extensive HIV prevention programs, have in fact succeeded in improving HIV knowledge and awareness around the globe.1 Although HIV prevalence rates are showing signs of leveling off in recent years, they are not decreasing as fast as hoped for given the large amount of effort and money spend on HIV prevention.1 In 2008, 2.7 million new infections took place, with 71% of those in sub-Saharan Africa.2 It is therefore important to gain a better understanding of which specific knowledge and awareness factors have actually increased the use of preventive measures and which have not, so as to better focus prevention efforts and raise their effectiveness.

Many prevention programs focus on women. For example, in the UNAIDS policy position paper, women and girls are mentioned as one of the key populations to target HIV prevention.3 This stems from the fact that in sub-Saharan Africa, HIV affects women disproportionately. Women account for 60% of HIV infections.1 This is often attributed to biological reasons, socioeconomic status, or lack of bargaining power restricting use of preventive measures.4–6 Moreover, the number of women with comprehensive HIV knowledge in Western Africa is found to be 10%–20% lower than men.7 These differences have led many prevention programs to focus on women. However, if it is male culture or lack of female bargaining power that blocks use of effective prevention methods, HIV prevention campaigns might be more efficient when focused on males. So when diversifying prevention campaigns across the sexes, it is important to know which types of knowledge are relevant for males and females, respectively. In other words, what type of information works and what does not for each of the sexes?

Globally, HIV knowledge has thus far been increased on two levels. First, awareness of the existence and transmission of HIV has been promoted. In Nigeria, this has been relatively successful: in 2009, over 90% of the Nigerian population had heard of HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).8 Second, ways of preventing infection with HIV have been communicated. The famous “abstinence, be faithful, use a condom” (ABC) has now been incorporated in most prevention campaigns all around the world. Condoms are widely available in Lagos and at low cost.9 In 2009, the cheaper brands sold for only NGN6.67 (about USD0.06) each, costing as little as 1% of the average daily consumption. This means that the claim that knowledge about the impact of condom use has no effect because condoms are either not available or are too expensive when they are available is not credible.

Despite the improvement in HIV prevention knowledge, people still engage in unprotected sex, even in countries with high HIV prevalence rates where unprotected sex entails high risks. Many studies have shown low levels of condom use irrespective of infection risks.10–12 This result has been confirmed by a systematic analysis of condom use in four different cities in sub-Saharan Africa, where no significant higher condom use was found among populations with higher HIV prevalence rates.13 A similar result was found among factory workers with a high prevalence rate in Ethiopia, where condom use is low even though knowledge on condoms is widely spread.14 An increase in some forms of risky sexual behaviors was measured in Uganda over the period 1989–2005. Although abstinence increased among adolescents (15–24 year olds) from 23% in 1989 to 42% in 2005, males (15–49 year olds) were found to report more multiple sexual partnerships and sex with non-spousal partners over the 2001–2005 period (25%–29% and 28%–37%, respectively) while condom use with non-spousal partners among male adolescents declined from 65% to 55%.15 This risky sexual behavior is remarkable given the prevention knowledge and reduced risk of HIV contraction when condoms are used consistently.16,17

The literature on the impact of a change in knowledge on condom use shows mixed results. For example, a positive effect of HIV prevention method knowledge on protective sexual behavior was found among a sample in Uganda, Kenya, and Zambia.18 Similarly, a positive effect of knowledge on condom use was found in Zambia.19 But several other studies show little impact on condom use with increased knowledge of its protective benefits.20,21 Reasons for the mixed results found in the literature could be that different measures for HIV knowledge were used and that outcomes may be gender or context specific. In this paper, these potential biases are addressed.

Furthermore, risky sexual behavior in spite of preventive knowledge is less surprising if people are unaware of the level of risk of contracting HIV when having unprotected sex, ie, knowing how to reduce risk may not change behavior if the level of risk is thought to be low. The degree of riskiness of unprotected sex is not often addressed in HIV prevention campaigns. And neither are evaluations on the relation between risk perception and preventive behavior widely incorporated in the empirical research on condom use. Among the exceptions, risk perception is found to be positively related to condom use among young people in urban Cameroon, but the results are only significant when looking at males with a casual partner.22 Sex workers in Nigeria were found to underestimate the risk as many believed that it was God that decided on their fate, leading to low protective behavior.23 A different study also looked at the perception of the individual on his or her chances of getting HIV.26 However, in this analysis on condom use, only a dummy variable for “correct perception” of the risk by the individual was included rather than the level of perception of the risk as such. This study found weak evidence for a positive relation between correct risk perception and condom use. But it is the actual perception of the risks by the individual that matters in their decision making, not whether that perception is known by researchers to be correct or incorrect. Therefore, the relation of risk perception on preventive behavior directly, together with standard knowledge indicators, will be analyzed here.

Stigma attached to HIV may be another factor inhibiting safe sexual behavior. High stigma levels may discourage raising HIV issues when deciding to have sexual intercourse, reducing condom use among HIV-negative individuals who want to prevent HIV contraction and among HIV– positive individuals who want to prohibit HIV transmission. People who feel more confident raising the issue of condom use during sexual intercourse are indeed more likely to use condoms.22 Not taking into account individual stigma levels when analyzing the relation between HIV knowledge and safe sexual behavior could thus lead to biased results. Therefore, this paper explicitly pays attention to stigma issues in the questionnaire and subsequent analysis. Here, too, gender issues may be of paramount importance.

To sum up, the following questions are addressed in this paper:

What is the state of knowledge on HIV prevention methods and are there major gender specific differences?

Does knowledge on prevention methods increase condom use, when taking into account the perception of the risks involved, stigma levels, and potential misperceptions on the ways of transmission?

Is there a difference in the relation between HIV knowledge and risk perception and condom use between men and women?

Data and methods

This paper used data collected for the “Lagos Market Survey” in 2008. It included responses from 1979 low- and middle-income families of persons who sold goods or services from a stall in one of the markets in Lagos, the financial capital of Nigeria. Although Nigeria’s HIV prevalence rates are relatively low compared to Eastern and Southern Africa, recent data show that AIDS is a growing public health problem in Nigeria. Since 2000, the number of AIDS orphans has grown from 1,100,000 to 2,500,000 in 2009.25 In the same year, 3.6% of its population was found to carry the virus based on a national population-based survey that included HIV testing.2

Out of 59 markets, 16 markets were randomly selected, stratified by area and selected with probability proportional to size. Stallholders and their households were approached based on listings provided by the leader of the respective market. Interviews mainly took place in the household dwelling and interviewers aimed at interviewing all household members privately and separately. Local interviewers were trained during an extensive 2-week training program, which included role-plays and actual field tests. The questionnaire contained several questions related to HIV knowledge and perception but also to sexual experience and behavior, and was administered by an interviewer with a medical background. Adult household members were screened for several diseases including HIV/AIDS. From household members aged 12 years and older blood was collected after informed consent was given (for subjects ≤18 years old consent was provided by one of the parents). Eight drops of blood were collected in an ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tube by making a puncture at the fingertip using a sterile lancet. HIV status of the respondents was determined using Determine™ HIV-1/2 rapid test (Waltham, MA, USA), a standard World Health Organization-approved rapid screening test. Respondents were also screened for malaria, diabetes mellitus, and anemia based on blood tests. Moreover, anthropometric measurements were performed for length, weight, waist circumference, and blood pressure. The Lagos State Government Ministry of Health gave approval for the survey and ethical clearance was received from the ethical committee of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital. A detailed description of the survey methodology and the characteristics of the households can be found in the baseline survey report.26 Most of the information was collected for all household members of the stallholders but the financial decision maker of the household was focused on, as only this person was asked to answer the subset of questions on risk perceptions in the survey.

Measures

In the multivariate analyses, the answer to the question “Did you use a condom during the last time you had sex?” was used as the dependent variable. Alternatively, reported condom use as a prevention method could be used but condom use during last sexual intercourse is generally seen as a better proxy for unsafe sexual practices.

Essential to HIV prevention is knowledge on the existence of HIV/AIDS, which was measured by response to the question: “Have you ever heard of HIV/AIDS?”

HIV prevention knowledge was measured using the answers to the interview question: “What can someone do to reduce the risk of contracting HIV?” Respondents could give up to four responses. From the responses, a prevention knowledge indicator ranging from zero to eleven was constructed by assigning points for good answers and subtracting points for giving bad answers. Good answers included abstaining from sex, using condoms, and limiting sex to one partner (two points). Reasonable answers included limiting the number of sexual partners, avoiding sex with prostitutes, avoiding having sex with persons having many partners, avoiding sex with homosexuals, avoiding sex with persons who inject drugs intravenously, and circumcision (one point). Bad answers included avoiding kissing, avoiding mosquito bites, and seeking protection from a traditional practitioner (minus one point). Zero points were given for avoiding injections or blood transfusions. Respondents who had never heard of HIV/AIDS were automatically set to the minimum. The total points scored thus measured two different things together: the quality of knowledge and, put loosely, the amount of knowledge (number of answers given).

In an attempt to separate these two effects, the total number of points scored was divided by the number of responses the respondent gave. As such, the measure is a proxy for the quality of knowledge alone and therefore does not reward respondents who were able to give more than one answer.

Three other prevention knowledge measures include knowledge on each of the famous ABC. Finally, a fifth and sixth prevention knowledge indicator was constructed, showing whether respondents could mention at least one of the ABC or the full ABC, respectively.

Misperceptions on HIV ways of transmission may lead to wrong preventive actions. Using a set of three questions, an HIV misperception indicator ranging from zero to three was created. The indicator included answers to the following questions: “Can people get HIV/AIDS from mosquito bites?”, “Can people get HIV/AIDS by sharing food with a person who has HIV/AIDS?” and “Is it possible for a healthy looking person to have HIV/AIDS?” For each incorrect answer, respondents were penalized by one point. For each answer they did not know, 0.5 penalty points were added.

HIV stigma was included in the questionnaire with four stigma-related questions focused on fear of casual transmission and refusal of contact with people living with HIV/AIDS: “If you learn that a fresh food vendor is HIV positive but not sick, would you buy fresh food from him/her?”, “If a relative of yours became sick with the virus that causes AIDS, would you be willing to care for him/her in your own household?”, “If a member of your family got infected with HIV, would you want it to remain a secret?” and “If a teacher is HIV positive but not sick, should she be allowed to continue teaching in school?” Based on a similar penalty system used for the misperception indicator, a stigma indicator ranging from zero to four was constructed.

HIV preventive behavior was measured by the answers to the following question: “How do you reduce the risk of contracting HIV/AIDS?” Note that providing an answer to this question requires knowledge on HIV prevention methods. Based on the responses, two HIV prevention indicators were created. The first equaled the total score, constructed similarly to the HIV prevention knowledge indicator, and ranged from zero to eleven. The second was the total score divided by the number of responses to the question, ranging from negative four to two. Respondents who had never heard about HIV/AIDS were again assigned the lowest value, ie, zero.

Based on a psychometric risk perception scale, the perceived risks involved in engaging in unprotected sex in addition to the measurement of HIV knowledge were measured. This allowed more insight into understanding why people engage in unprotected sex, while knowing how HIV infection can be prevented. Specifically, as suggested by Blais and Weber,27 respondents indicated on a seven-step psychometric Likert scale how risky they perceived engaging in unprotected sex to be. The involved risk ranged from “not at all risky” to “extremely risky.” To improve respondents’ understanding, the seven-step scale was presented on cards, which respondents pointed at to indicate the step most applicable to them.

Statistical methods

The current state of knowledge and behavior among the study sample was assessed by looking at the mean score on individual items. All available indicators were included: HIV prevention knowledge, HIV misperception, HIV stigma, HIV preventive behavior, and risk perception. Differences between males and females were analyzed by comparing the mean scores for each item separately. The two-tailed nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to assess the statistical significance of the differences.

Of course such bilateral correlations are informative but run the risk of bias due to omitted third variables. Therefore, multivariate regression analysis was used to examine the effect of HIV knowledge and perception indicators on condom use. This analysis included the same indicators as the bivariate analyses except, of course, for the HIV preventive behavior indicators, which became the dependent variable. The specific question on condom use during last sexual intercourse was used as the dependent variable. Because of the discrete binary nature of the dependent variable, a logistics regression was used. The corresponding probability level, odds ratio, and 95% confidence intervals were computed based on the logistic regression. This regression corrected for potential differences between markets, which may be present given the sampling approach in the data collection (clustering at the market level). The analysis was performed on the full sample, on the subsample of all males, and on the subsample of all females.

The multivariate analysis controlled for age, gender, educational level, marital status, and the number of sexual partners in the past 12 months. Age was classified in three age groups: young adults (18–24 year olds, n = 55), adults (25–49 year olds, n = 1131) and elderly (>50 year olds, n = 355). Additional control variables included a dummy variable for not knowing where to get a condom (n = 272), which can be expected to reduce the likelihood of using condoms, and a dummy variable “birth control no condom” to analyze whether condom use differed in partners already using birth control other than condoms (n = 136). Another variable “wants child, one partner” was included to control for faithful respondents that indicated the desire of having a child within 1 year (n = 271). Obviously, these respondents cannot fulfill their child wish when using condoms. It did not make sense to classify their unprotected behavior as risky in the same way as for those respondents not having a near-future child wish or having more sexual partners.

Sample

The analysis excluded respondents that were irrelevant for the analysis, ie, respondents that had never had sex (n = 52) and respondents who had not had sexual intercourse in the past 12 months (n = 159). Respondents who might have chosen to abstain from sex as a way of preventing HIV contraction were also excluded (20.1%). Among those who had had sexual contact during the past 12 months, the abstinence percentage was 14.1%. Respondents who had sexual intercourse during the past 12 months were focused on because the explanatory variables cover behavior over the past 12 months. Finally, respondents that reported to have used condoms to avoid pregnancy (n = 174) were also excluded, as their use was not aimed at avoiding sexually transmitted diseases. The final sample included 1554 sexually active respondents. Due to missing observations for the included socioeconomic explanatory variables, the total number of observations in the statistical models was 6% lower than in the total sample.

Results

Demographics

In the study sample, 49.5% were male. More than half of the respondents reported to be married (66.9% versus 69.2% for males and females, respectively). Marital status did not significantly differ across the sexes. Age ranged from 18–100 years, with an average age of 41.3 years. The average annual income obtained from work was NGN466,468 (approximately USD7,745). A majority of respondents could write (81.0%) and 51.5% had completed secondary education. Almost half of the respondents was Muslim (48.2%) and 51.1% was Christian, among which 9.3% were Catholic. Yoruba was the most prevalent language (75.2%), followed by Igbo (18.1%).

HIV knowledge

Table 1 presents an overview of the HIV/AIDS knowledge and perception indicators for the complete sample and for males and females separately. The other HIV knowledge indicators are presented only for those respondents who reported to have heard of HIV/AIDS (indicated in the table by a left indent); 89.5% of the respondents reported to have heard of HIV/AIDS before. Among those respondents, the mean score on the HIV prevention knowledge indicator was 7.01. Only 8.0% was able to mention four prevention methods and 26.0% was able to mention three methods. For the HIV knowledge indicator based on the average score, 37.48% scored the maximum of two. Although the majority mentioned one ABC (82.2%), only a small minority mentioned all three ways to prevent HIV infection (5.3%). On the HIV transmission misperception indicator, 33.95% scored zero, ie, had no misperceptions on the formulated questions and only 1.28% had the maximum score of three. HIV stigma appeared to be highly prevalent among the respondents: 70.5% scored at least one, 41.6% scored at least two, and 11.5% scored at least three on the HIV stigma indicator.

Table 1.

HIV knowledge and behavior

| Variable | n | Total sample | M | F | P-value† (H0: M = F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge on the existence of HIV/AIDS | |||||

| Never heard of HIV/AIDS | 1929 | 10.5% | 5.5% | 15.3% | 0.000* |

| HIV prevention knowledge# | |||||

| HIV prevention knowledge indicator, total score (0–11)‡ | 1657 | 7.01 | 7.15 | 6.85 | 0.017* |

| HIV prevention knowledge indicator, average score (−1 to 2) | 1657 | 1.43 | 1.52 | 1.33 | 0.000* |

| a. Mentions abstaining from sex can prevent HIV contraction | 1726 | 24.3% | 22.7% | 26.1% | 0.101 |

| b. Mentions being faithful can prevent HIV contraction | 1726 | 51.7% | 50.4% | 53.1% | 0.270 |

| c. Mentions condoms can prevent HIV infection | 1726 | 43.3% | 54.3% | 31.2% | 0.000* |

| Mentions one of the abc | 1726 | 82.2% | 87.1% | 76.6% | 0.000* |

| Mentions abc | 1726 | 5.3% | 5.1% | 5.6% | 0.651 |

| Does not know where to get condoms | 1932 | 19.4% | 9.4% | 29.1% | 0.000* |

| HIV-related perceptions | |||||

| HIV stigma indicator (0–4) | 1723 | 2.09 | 2.04 | 2.16 | 0.023* |

| HIV transmission misperception indicator (0–3) | 1723 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.306 |

| Risk perception of unprotected sex (1–7) | 1914 | 5.46 | 5.52 | 5.40 | 0.258 |

| HIV-related behavior | |||||

| HIV prevention indicator, total score (0–11) | 1676 | 6.67 | 6.78 | 6.54 | 0.158 |

| HIV prevention indicator, average score (−1 to 2) | 1676 | 1.33 | 1.43 | 1.22 | 0.000* |

| a. Mentions abstaining from sex to prevent HIV contraction | 1726 | 17.1% | 14.3% | 20.2% | 0.001* |

| b. Mentions being faithful to prevent HIV contraction | 1726 | 50.8% | 49.4% | 52.4% | 0.225 |

| c. Uses condoms to prevent HIV | 1726 | 37.1% | 47.0% | 26.3% | 0.000* |

| Used condom during most recent sex | 1961 | 18.9% | 27.8% | 10.1% | 0.000* |

| Had more than one sexual partner in past year | 1855 | 12.8% | 23.8% | 1.9% | 0.000* |

| Married respondents that had more than one sexual partner in the past year | 1258 | 10.5% | 19.6% | 1.9% | 0.000* |

| HIV prevalence | 964 | 1.45% | 0.84% | 2.06% | 0.114 |

Notes:

Statistical differences based on Wilcoxon rank-sum test

significant results (P < 0.05)

these results are calculated only for those respondents who had ever heard of HIV (results including those who had never heard of HIV were also calculated, but this hardly changed the results). The difference in abstaining from sex became much less significant (P = 0.78).

Based on a subsample of those who had heard of HIV/AIDS.

Abbreviations: ABC, abstinence, be faithful, use a condom; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; F, female; HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; M, male.

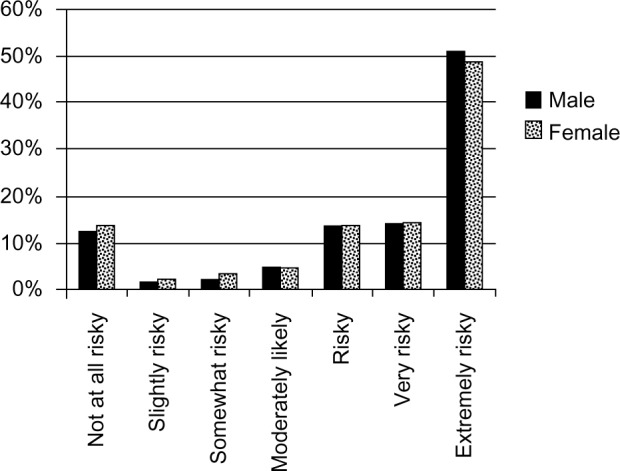

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the answers to the question on the perception of risk in having sex without a condom. About half of the respondents (49.8%) perceived unprotected sex as extremely risky. This was slightly higher among unmarried respondents (50.3%). On the other end of the spectrum, 7.5% of the unmarried respondents reported engaging in unprotected sex not to be risky at all compared to 15.6% of the married respondents.

Figure 1.

Response to risk perception of engaging in unprotected sex.

HIV knowledge and perception statistics across the sexes

Table 1 shows that there are significant differences between males and females on a number of HIV indicators with males generally scoring better. On the question whether the respondent had ever heard of HIV/AIDS, for example, more than 15% of the women answered negatively compared to 5.5% of the men. Among those respondents who had heard of HIV, males also scored significantly better on the prevention knowledge indicator. Men in particular had better knowledge on condoms: over 50% of them mentioned condoms as a way to prevent HIV infection, whereas only slightly over 30% of the women mention this as possible prevention measure. More males (87.1%) mentioned one ABC compared to females (76.6%; P < 0.0001). This result is mostly driven by knowledge of the prevention value of condoms. No significant difference between males and females was observed in the ability to mention abstaining from sex and being faithful. Nevertheless, information on HIV prevention seems to have reached the males better than the females in the studied sample.

Knowledge on where to get condoms by at least one of the sexual partners is a prerequisite for using condoms. In spite of the wide availability of condoms, a large percentage of females did not know where to get condoms (29.1% versus 9.4% for females and males, respectively). There was no significant difference in knowledge on where to get condoms between married and unmarried persons for either of the sexes. Although the stigma indicator did not differ much between males and females, the indicator was significantly lower among males. No significant difference was observed in the HIV transmission misperception indicator or the risk perception of unprotected sex between males and females.

Males’ advantage in knowledge was also reflected in their sexual behavior. Among those who had ever heard of HIV/AIDS, men were more likely to use HIV prevention methods. They scored better on the general HIV prevention indicator, were more likely to use condoms to prevent HIV contraction, and more often used condoms the last time they had sexual intercourse (27.8% versus 10.1% for males and females, respectively; P < 0.001). Singles used condoms significantly more than married persons. Males on average abstained less from sex as an HIV prevention measure (although not significantly so) and reported significantly more often to have more sexual partners compared to females. Among male respondents who currently have a sexual partner, the average number of sexual partners was 1.52; among females, this was 1.03. Blood tests, however, show that HIV prevalence among the females was more than twice as high (0.8% versus 2.1% for males and females, respectively). Of course such bilateral correlations are informative but run the risk of bias due to omitted third variables. Therefore, multivariate regression analyses were used for the remaining results.

Explaining condom use

Table 2 shows the results of an attempt to establish factors influencing condom use through multivariate estimation for the full sample and for males and females separately. The odds ratio (“e” to the power of the relevant estimated coefficient) and 95% confidence interval are listed for each explanatory variable; testing the odds ratio against one is equivalent to testing the significance against zero of the untransformed coefficient in the logistic regression.

Table 2.

Condom use during most recent intercourse across the sexes

| Condom use | Model 1A (AII)

|

Model 1B (males)

|

Model 1C (females)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Risk perception (1–7) | 1.12 | (1.01–1.22)** | 1.15 | (1.03–1.28)** | 1.06 | (0.92–1.21) |

| HIV prevention knowledge indicator (0–11) | 1.02 | (0.94–2.18) | 0.99 | (0.88–1.11) | 1.08 | (0.96–3.05) |

| HIV stigma indicator (0–4) | 0.89 | (0.75–1.05) | 0.92 | (0.77–1.12) | 0.77 | (0.61–1.00)** |

| HIV transmission misperception indicator (0–3) | 0.94 | (0.73–1.17) | 1.07 | (0.82–1.40) | 0.65 | (0.43–0.96)** |

| Number of sexual partners | 1.06 | (0.92–1.23) | 1.05 | (0.9–1.21) | 1.30 | (0.64–2.57) |

| Don’t know where to get condoms# | 0.03 | (0.00–0.31)*** | – | 0.08 | (0.01–0.75)** | |

| Single | 3.62 | (2.57–5.20)*** | 3.77 | (2.54–5.60)*** | 3.27 | (1.70–6.25)*** |

| Divorced | 2.74 | (1.51–4.98)*** | 4.66 | (1.48–14.7)*** | 1.84 | (0.83–3.94) |

| Widowed | 1.41 | (0.52–4.22) | 7.29 | (1.03–51.0)** | 0.46 | (0.07–3.34) |

| Consensual union | 0.88 | (0.63–1.19) | 0.74 | (0.45–1.24) | 1.11 | (0.50–2.40) |

| Birth control, no condom | 0.94 | (0.56–1.48) | 0.55 | (0.06–4.97) | 0.98 | (0.54–1.68) |

| Want child, one partner | 0.58 | (0.38–0.83)*** | 0.51 | (0.30–0.87)** | 0.62 | (0.34–1.11) |

| Male | 2.09 | (1.20–3.09)*** | ||||

| Age 18–24 years | 2.28 | (0.68–7.08) | 2.58 | (0.52–12.9) | 2.36 | (0.81–6.53) |

| Age 25–49 years | 1.71 | (0.97–3.00)* | 1.52 | (0.55–4.24) | 2.50 | (1.05–6.09)** |

| Educational level | 1.05 | (1.01–1.09)** | 1.06 | (1.00–1.11)** | 1.02 | (0.96–1.09) |

| Adjusted r2 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.16 | |||

| Observations | 1405 | 595 | 788 | |||

Notes:

P < 0.01

P < 0.05

P < 0.1

for males, no estimates are provided because this variable predicts non-condom use among males perfectly. All males (n = 62) not knowing where to get condoms had to be dropped from the analysis.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; OR, odds ratio.

The results listed under Model 1A clearly show that a higher risk perception of engaging in unprotected sex increased the propensity to use condoms among the full sample. A better score on the HIV prevention knowledge indicator was, however, not significantly associated with condom use. This may well be because the indicator measured two different things at the same time: how much does the respondent know and what is the quality of his knowledge? The results including the HIV prevention knowledge indicator based on the average score – measuring only the quality of knowledge – are reported below. The other two main indicators – HIV stigma and HIV transmission misperception – were not significant when the equation was estimated over the sample as a whole. Among the other control variables, not knowing where to get condoms significantly reduced condom use. Education, age, and relationship status were also significant. Those who were single or divorced were more likely to have used a condom compared to respondents who were married. Respondents who had a single partner and would like to have a baby within 1 year were less likely to have used a condom during the most recent intercourse. In general, males were 2.09 times more likely to have used a condom than females even after controlling for all the other variables including the number of sexual partners.

To check for any difference in the relation between HIV knowledge and condom use among males and females, condom use during the most recent intercourse was analyzed for both sexes separately (Model 1B and 1C). Strikingly, the risk perception of engaging in unprotected sex was only significant for males. Once again, the aggregate HIV prevention knowledge indicator was not significant for both sexes. For both males and females, not knowing where to get condoms reduced condom use. Being single compared to being married also significantly reduced condom use. Education, being divorced, and wanting a child soon were only significant for males. For females, age was also significant.

Important differences between males and females are apparent, not only in the coefficient of the risk perception indicator but also when looking at the HIV stigma and misperception indicators. These were not significant in the full sample nor for males only, but they were significant when looking at females only. A higher score on either measure reduced the likelihood of using condoms for females.

The lack of significance of the generic prevention knowledge indicator is puzzling. In order to gain a better understanding, the HIV prevention knowledge indicator was replaced by four other, more detailed knowledge indicators. These four indicators were also part of the overall HIV prevention knowledge indicator, which means that all the indicators in the model cannot be included at the same time as this would trigger perfect collinearity among the explanatory variables. All other control variables were again included in the estimation, but the results are not reported as they differ only marginally from those reported in Table 2. Therefore, only the coefficients for the new variables are reported (Table 3).

Table 3.

Other HIV prevention knowledge measures

| Condom use during last sex | Adjusted r2 | Indicator evaluation A (AII)

|

Indicator evaluation B (males)

|

Indicator evaluation C (females)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||

| HIV prevention knowledge indicator, average score (−1 to 2) | 0.18 | 1.66 | (1.26–2.18)** | 1.60 | (1.05–2.42)** | 1.78 | (1.03–3.05)** |

| Never heard of HIV/AIDS | 0.16 | 1.11 | (1.02–1.20)** | 0.84 | (0.24–2.98) | 0.45 | (0.10–1.92) |

| a. Mentions abstaining prevents HIV infection | 0.16 | 0.78 | (0.57–1.06) | 0.68 | (0.41–1.14) | 1.02 | (0.45–2.30) |

| b. Mentions being faithful prevents HIV infection | 0.16 | 0.80 | (0.45–1.43 | 0.70 | (0.34–1.44) | 1.03 | (0.59–1.80) |

| c. Mentions condom prevents HIV infection | 0.17 | 1.98 | (1.17–3.35)** | 2.47 | (1.06–5.74)** | 1.35 | (0.77–2.36) |

| Mentions one of the abc | 0.16 | 1.61 | (1.02–2.55)** | 1.86 | (0.86–4.03) | 1.32 | (0.62–2.84) |

| Mentions full abc | 0.16 | 0.60 | (0.31–1.17) | 0.50 | (0.15–1.67) | 0.86 | (0.93–1.25) |

Notes:

P < 0.05. Estimations of all variables as specified in Table 2 (except for the HIV prevention knowledge indicator).

Abbreviations: ABC, abstinence, be faithful, use a condom; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CI, confidence interval; HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; OR, odds ratio.

Table 3 shows that the HIV prevention knowledge indicator, once it is more narrowly defined as a measure of the quality of knowledge only, became significant for both males and females. This is in contrast to the lack of significance of the more general HIV prevention knowledge indicator included in Table 2. Having never heard of HIV/AIDS reduced the likelihood of condom use but only in the full sample. Knowing that condoms prevent HIV infection increased condom use in the full model and for males. Males who know that condoms prevent HIV were 2.47 times more likely to have used a condom the last time they had sexual intercourse compared to men who don’t know. For both sexes, there was no relation between condom use during last intercourse and mentioning abstinence or being faithful as a method to prevent HIV infection, nor when the number of sexual partners was excluded to avoid potential multicollinearity. Having mentioned at least one ABC had a significant positive effect in the full sample estimation, but not in the model for males and females separately. The significance in the full model was likely to be caused by the fact that a large number of respondents answered that condoms prevent HIV and that this variable was significantly correlated to condom use. This is also supported by the fact that the final variable, having mentioned all three ABC, was not significant in any model.

To sum up, the more detailed specification of the knowledge indicator did restore significance to that indicator, but otherwise does not change the most striking result reported in Table 2, ie, the difference in significance between male and females of the risk perception and the stigma indicators: risk perception had no impact on condom use by females, and stigma had no impact on condom use by males but it did very much have an impact (and negatively so) on condom use by females.

Discussion

The main contribution of this paper to the literature on condom use is the wide range of knowledge indicators that were analyzed, the use of less common control variables such as the willingness to get pregnant and risk perception, and the extensive multivariate analysis focusing on differences between males and females. The study shows that males have better HIV knowledge and that there are significant differences between males and females in the explanation of their likelihood of having used a condom.

Knowledge gap between males and females

Information on HIV prevention in Lagos seems to have reached the males better than the females in the study sample. On almost all of the HIV knowledge indicators (knowledge on the existence of HIV, prevention knowledge, condom knowledge, knowledge on where to get condoms), males scored better than females; in particular, condom knowledge was substantially lower among women. Males also had fewer misperceptions on HIV-related issues and, moreover, stigmatized HIV-positive individuals less than females did. This large knowledge gap between males and females confirms data showing that comprehensive HIV knowledge is substantially lower among women than among men in most West African countries.7

Knowledge on the existence of HIV among the study sample (89.5%) was a little lower than the country average measured in 2009, when 91.1% had heard of HIV/AIDS. The (small) difference is possibly related to the specific characteristics of the respondents in the current study. They all work in the informal sector – a sector characterized by a lower education level.

Differences in sexual behavior

Male respondents were much more likely to have had multiple sexual partners (23.8% versus 1.9%). In-depth studies show higher promiscuous behavior (including paid sex) among males.7 This may partially explain why males were more likely to have used a condom during their last sexual intercourse (27.8% versus 10.1% for males and females, respectively; P < 0.001). The level of condom use among males is comparable to the 25% previously found among Ghanaian men.28 The higher number of sexual partners could also explain why males have more knowledge on HIV-related issues: promiscuous behavior demands more knowledge and protection.

Condom use

The regression results show that the different components of prevention campaigns, eg, spreading knowledge about transmission and combating stigma, may enhance condom use but the impact differs between the sexes.

The HIV prevention knowledge indicator was only significant when taken as the average score. This suggests that quality of knowledge is important in determining condom use, while the amount of knowledge is not. The result holds for both males and females. The difference in the significance of these two measures suggests that empirical results in the literature on condom use are sensitive to the precise definition of the variables. This may explain the large variation in empirical estimates of the effect of knowledge on prevention methods.

The results also show that risk perception was positively related to condom use in the full sample, confirming results from the existing literature.22 Risk perception was not, however, significant for females. A study among couples from South Africa showed that wives’ perception of the risk of getting HIV from their partner was positively related to condom use.29 The nonsignificant result found among the current female sample may be due to cultural effects in Nigeria which might prohibit females from using condoms.9,30 Another possibility is that females would like to use condoms but have low bargaining power, thus being submitted to the desire of males on whether or not a condom is used.6,31 In that case, whether risks are perceived or not does not matter since they do not have free choice. In a similar vein, it was found that risk perception, contrary to males, had no impact on condom use by females. This too is consistent with a low bargaining power explanation. An alternative explanation might be reporting bias; if females are more hesitant to report promiscuous behavior than men, they might underreport condom use even if they do use condoms simply because they do not want or dare to report the sexual activity during which the condoms were used. Previous literature indeed shows that females tend to underreport promiscuous behavior.32,33

Another result may shed light on the question of which explanation best fits the puzzling differences in patterns of condom use between males and females. A stigma indicator was also included in the regression explaining condom use. The variable did not have any significance for males but showed a significantly negative coefficient in the regression explaining condom use for females. This is not easy to reconcile with the reporting bias explanation of male/female differences in condom use. It is not obvious why that bias would be higher for women aware of HIV stigma than for women generally; it is more reasonable to expect no correlation with the stigma indicator rather than a negative correlation. Without correlation with the explanatory variable, errors in the dependent variable did not cause an estimation bias. Therefore, it can be concluded that lack of bargaining power is the more likely explanation of the current findings.

Limitations to this study include the lack of information on the partner of the respondent. It would be very informative to include information on the sexual behavior of the partner in the analysis as that may be an important motivation for preferring to use a condom. The analysis would also benefit from knowing whether the last sexual intercourse was with the regular partner or with a casual partner. A different limitation relates to the possibility of drawing a general conclusion based on a specific regional and highly concentrated sample. Much more research is needed to confirm whether these results can be generalized to other regions of Nigeria, other parts of Africa, and other continents.

Conclusion

Analyzing why people fail to take adequate measures to protect themselves against HIV/AIDS infection is of key importance for the drive to reduce new infections. The results suggest that the relation between condom use and various knowledge indicators is more complex than often thought, in ways that should have consequences for the design of public policies to combat further spread of the disease.

The analyses show that HIV-related prevention knowledge does matter, although the precise definition of the variable was shown to be an issue. Also, the HIV knowledge gap between males and females would seem to suggest that HIV prevention campaigns should focus on improving knowledge among women, as there is more progress to be had in that direction. However, the results also indicate that may not be enough. Condom use analysis across the sexes shows that, in particular, risk perceptions of engaging in unprotected sex did not significantly increase the propensity to use condoms among women. This is in contrast to males, where HIV knowledge and risk perception do lead to preventive actions. This difference between males and females in the impact of risk perceptions on condom use may be related to underreporting bias that has been shown to be more of an issue with women. However, it is not clear why that bias should be correlated with risk perceptions or with fear of stigmatization, both of which show strong differential impact on condom use among men and women. An alternative explanation could be low bargaining power within sexual relations: higher risk perceptions among women can only lead to higher condom use if men accommodate that desire for safer sex. If low bargaining power of women is indeed the mechanism blocking increased condom use by women aware of the risks of engaging in unsafe sex, policies aimed at reducing unprotected sex should arguably be more focused on men in the hope that women will not be forced to subject themselves to risky practices.

Preventive behavior across all females could, if the results can be generalized, be enhanced by reducing HIV stigma, since this factor reduced condom use among females strongly in the study sample. Moreover, knowledge on where to get condoms needs to be improved, as 30% of the females did not know where to get a condom and this lack of knowledge had a significantly negative impact on their condom use. Making condoms more available to females by distributing them, for example, at schools/clinics, bars, and nightclubs is an option worth considering. Although much smaller, the percentage of males who did not know where to get condoms was also too large (approximately 10%).

Besides knowledge of reducing HIV infection risk by using condoms, the perception of the risk of engaging in unprotected sex appears to be important in the decision of whether to use a condom or not, at least among males. Influencing this risk perception among males in HIV prevention programs is underexplored, and developing effective methods to increase this risk perception would seem important.

Of course these results are based on the analysis of a highly specific sample and much more work is needed to establish whether these results can be generalized. If they can be generalized, they have strong implications for the design of public policy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for all colleagues and parties involved in setting up the unique dataset used in this paper: Health Insurance Fund (HIF), The Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, PharmAccess Foundation, Center for Poverty-related Communicable Diseases (CPCD), Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH), and Amsterdam Institute for International Development (AIID). Special gratitude goes to Damien de Walque, Professor JM Baland, and other participants of the annual workshop on the Economics of AIDS. Moreover, the authors thank Ton Vriend for sharing his experiences in HIV prevention in Swaziland, which formed the basis of the analysis on gender differences.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.UNAIDS . Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2008. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. World Health Organization 2009AIDS Epidemic Update Geneva: UNAIDS; 2009Available from: http://data.unaids.org/pub/report/2009/jc1700_epi_update_2009_en.pdfAccessed October 23, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS Intensifying HIV Prevention: A UNAIDS Policy Position Paper Geneva: UNAIDS; 2005Available from: http://data.unaids.org/publications/irc-pub06/jc1165-intensif_hiv-newstyle_en.pdfAccessed October 23, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royce RA, Sena A, Cates W, Jr, Cohen MS. Sexual transmission of HIV/AIDS. New Engl J Med. 1997;336(15):1072–1078. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seeley JA, Malamba SS, Nunn AJ, Mulder DW, Kengeya-Kayondo JF, Barton TG. Socioeconomic status, gender, and risk of HIV-1 infection in a rural community in South West Uganda. Med Anthropol Q. 1994;8(1):78–89. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Gray GE, McIntryre JA, Harlow SD. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet. 2004;363(9419):1415–1421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowndes CM, Alary M, Belleau M, et al. West Africa HIV/AIDS Epidemiology and Response Synthesis. Characterisation of the HIV Epidemic and Response in West Africa: Implications for Prevention Washington, DC: World Bank; 2008Available from: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTHIVAIDS/Resources/375798-1132695455908/WestAfricaSynthesisNov26.pdfAccessed October 23, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) Harmonised Nigeria Living Standards Survey. Abuja: NBS; 2009. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koster W. Secret Strategies: Women and Abortion in Yoruba society, Nigeria. Amsterdam: Aksant Academic Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Walque D, Kline R.Comparing Condom Use with Different Types of Partners: Evidence from National HIV Surveys in Africa Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2009Available from: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/servlet/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2009/11/16/000158349_20091116092821/Rendered/PDF/WPS5130.pdfAccessed October 23, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biraro S, Shafer LA, Kleinschmidt I, et al. Is sexual risk taking behaviour changing in rural south-west Uganda? Behaviour trends in a rural population cohort 1993–2006. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85(Suppl 1):i3–i11. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.033928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed S, Lutaloa T, Wawer M, et al. HIV incidence and sexually transmitted disease prevalence associated with condom use: a population study in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 2001;15(16):2171–2179. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200111090-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagarde E, Auvert B, Chege J, et al. Condom use and its association with HIV/sexually transmitted diseases in four urban communities of sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2001;15(Suppl 4):S71–S78. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahlu T, Kassa E, Agonafer T, et al. Sexual behaviours, perception of risk of HIV infection, and factors associated with attending HIV posttest counseling in Ethiopia. AIDS. 1999;13(10):1263–1272. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199907090-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Opio A, Mishra V, Hong R, et al. Trends in HIV-related behaviors and knowledge in Uganda, 1989–2005: evidence of a shift toward more risk-taking behaviors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(3):320–326. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181893eb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weller S, Davis K. Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):CD003255. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinkerton SD, Abramson PR. Effectiveness of condoms in preventing HIV transmission. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(9):1303–1312. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacIntyre K, Brown L, Sosler S. “It’s not what you know, but who you knew”: examining the relationship between behavior change and AIDS mortality in Africa. AIDS Educ Prev. 2001;13(2):160–174. doi: 10.1521/aeap.13.2.160.19736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magnani RJ, Karim AM, Weiss LA, Bond KC, Lemba M, Morgan GT. Reproductive health risk and protective factors among youth in Lusaka, Zambia. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(1):76–86. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Essien EJ, Mgbere O, Monjok E, Ekong E, Abughosh S, Holstad MM. Predictors of frequency of condom use and attitudes among sexually active female military personnel in Nigeria. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 2010;2:77–88. doi: 10.2147/hiv.s9415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams BG, Taljaard D, Campbell CM, et al. Changing patterns of knowledge, reported behaviour and sexually transmitted infections in a South African gold mining community. AIDS. 2003;17(14):2099–2107. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309260-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meekers D, Klein M. Determinants of condom use among young people in urban Cameroon. Stud Fam Plan. 2002;33(4):335–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2002.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ankomah A, Omoregie G, Akinyemi Z, Anyanti J, Ladipo O, Adebayo S. HIV-related risk perception among female sex workers in Nigeria. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 2011;3:93–100. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S23081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prata N, Morris L, Mazive E, Vahidnia F, Stehr M. Relationship between HIV risk perception and condom use: evidence from a population-based survey in Mozambique. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2006;32(4):192–200. doi: 10.1363/3219206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.UNSTATS Millenium Development Goals Indicators New York: UNSTATS; Available from: http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Data.aspxAccessed July 2, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lammers J, Lange J, Van Spijk J, et al. Impact Evaluation of HIF-Supported Health Insurance Projects in Nigeria: Preliminary Results from the Baseline Survey in Lagos. Amsterdam: AIID-CPCD; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blais AR, Weber EU. A Domain-Specific Risk-Taking (DOSPERT) scale for adult populations. Judgm Decis Mak. 2006;1(1):33–47. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adih WK, Alexander SC. Determinants of condom use to prevent HIV infection among youth in Ghana. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24(1):63–72. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maharaj P, Cleland J. Risk perception and condom use among married or cohabiting couples in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2005;31(1):24–29. doi: 10.1363/3102405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orubuloye IO, Oguntimehin F, Sadiq T. Women’s role in reproductive health decision making and vulnerability to STD and HIV/AIDS in Ekiti, Nigeria. Health Transit Rev. 1997;7(Suppl):329–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andersson N, Ho-Foster A, Mitchell S, Scheepers E, Goldstein S. Risk factors for domestic physical violence: national cross-sectional household surveys in eight southern African countries. BMC Womens Health. 2007;7:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Walque D. Sero-discordant couples in five African countries: implications for prevention strategies. Popul Dev Rev. 2007;33(3):501–523. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nnko S, Boerma JT, Urassa M, Mwaluko G, Zaba B. Secretive females or swaggering males? An assessment of the quality of sexual partnership reporting in rural Tanzania. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(2):299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]