Abstract

Background

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use is common among breast cancer survivors, but little is known about its impact on survival.

Methods

We pooled data from four studies conducted in Hawaii in 1994–2003 and linked to the Hawaii Tumor Registry to obtain long-term follow-up information. The effect of CAM use on the risk of breast cancer-specific death was evaluated using Cox regression.

Results

The analysis included 1443 women with a median follow-up of 11.8 years who had a primary diagnosis of in situ and invasive breast cancer. The majority were Japanese American (36.4%), followed by white (26.9%), Native Hawaiian (15.9%), other (10.6%), and Filipino (10.3%). CAM use was highest in Native Hawaiians (60.7%) and lowest in Japanese American (47.8%) women. Overall, any use of CAM was not associated with the risk of breast cancer-specific death (hazard ratio [HR] 1.47, confidence interval [CI] 0.91-2.36) or all-cause death (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.63-1.06). However, energy medicine was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer-specific death (HR 3.19, 95% CI 1.06-8.52). When evaluating CAM use within ethnic subgroups, Filipino women who used CAM were at increased risk of breast cancer death (HR 6.84, 95% CI 1.23-38.19).

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that, overall, CAM is not associated with breast cancer-specific death but that the effects of specific CAM modalities and possible differences by ethnicity should be considered in future studies.

Introduction

The prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use in breast cancer survivors is estimated to be between 48% and 70% in the United States.1 Given the highly prevalent use of CAM, it is especially important to understand how CAM use impacts outcome measures, such as survival, in this population. Prior studies of CAM in cancer patients have largely focused on correlates of CAM use2–10 and quality of life outcomes.11–16 The limited number of studies that have evaluated the association of CAM use with survival have reported conflicting results.17–20 Many such studies have had limited sample sizes, short follow-up periods, or methodologic issues.5,21–27

Differences in the prevalence and type of CAM across ethnic groups have been reported.5,23–26 In a study of 379 women with recently diagnosed breast cancer, Chinese women were most likely to use herbal remedies, African Americans were most likely to use spiritual healing, and non-Hispanic white and Hispanic white women were most likely to use dietary methods.5 Another study of breast cancer patients in California showed that Hispanic white and African American women used natural products other than botanical supplements more frequently than did Latina and Asian American women and that the use of special diets was more common among Latina women than in other ethnic groups.25

Because of the large number of residents with Asian and Pacific Islander ancestry in Hawaii, previous research studies conducted in the State of Hawaii have included substantial numbers of these individuals. In this study, we pooled data from four population-based studies of ethnically diverse breast cancer survivors in Hawaii. Given the high prevalence of CAM use among women diagnosed with breast cancer and differences in use across ethnic groups, our aim was to establish how different CAM modalities may impact the relative risk of death due to breast cancer as well as breast cancer-specific survival in a large population-based sample and to explore potential differences across ethnic groups.

Materials and Methods

We included in situ and invasive female breast cancer cases from four population-based studies of cancer survivors28–33; the subjects were diagnosed during the years 1964–1999 in Hawaii. Subjects with missing data on CAM modality, education, tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) stage, surgery, chemotherapy, heart disease, or diabetes were excluded (n=30), resulting in 1443 women for the analysis. Data on demographic characteristics included age at diagnosis, ethnicity, education, marital status, and birthplace. Clinical characteristics included the presence of heart disease, diabetes, year of diagnosis, TNM stage, and receipt of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and hormone therapy. Information on survival and cause of death was obtained by linkage to the Hawaii Tumor Registry, which is part of the National Cancer Institute's (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Follow-up was through December 31, 2010.

Definitions of CAM have changed over time, and the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) currently categorizes CAM into five modalities: mind-body medicine (mind), manipulative and body-based practices (body), biologically based products (nature), energy medicine (energy), and whole medical systems (WMS).34 Mind-body medicine focuses on the link among mind, body, and behavior and includes meditation, yoga, tai chi, and hypnotherapy. Manipulative and body-based practices focus primarily on the body's structures (e.g., soft tissue, bones) and systems (circulatory, lymphatic) and include massage therapy and spinal manipulation. Biologically based products include herbs/botanicals, probiotics, and high-dose vitamins. Energy medicine focuses on the manipulation of energy fields and includes magnet therapy and Reiki. Finally, WMSs incorporate elements from the first five categories and include ancient healing systems, such as Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine, as well as more contemporary systems, such as homeopathy and naturopathy.

Table 1 summarizes the four studies and the types of CAM questions that were asked. The four studies were: (1) Quality of Life in Cancer Patients in Hawaii (QOL), the objective of which was to develop, validate, and pilot test an instrument appropriate to assess cancer-related quality of life among the culturally diverse cancer patient population in Hawaii,28,30–32 (2) Beating the Odds: A study of Patients Who Exceed Expected Survival Times (BTO), a study of individuals who were long-term survivors of cancers that are generally associated with poor survival,33 (3) Quality of Life in Patients Who Develop Subsequent Primaries (SP), a study that described the psychologic impact among people experiencing more than one primary cancer,29 and (4) Exploratory Study of Treatment Decision Making in Multiethnic Breast Cancer Patients (TDM), a study that focused on how patients make decisions about their breast cancer treatments. Two studies, BTO and SP, asked subjects: Which of the following remedies have you used for your cancer? and were given seven choices plus an open-ended other. One study, QOL, asked subjects if they used CAM currently or in the past and allowed both open-ended and coded answers. The fourth study, TDM, asked subjects if they used any of 12 CAM modalities plus an open-ended other. None of the patients participated in more than one study. Information on CAM use from each study was combined and categorized according to the NCCAM categories (mind-body medicine, manipulative and body-based practices, biologically based products, energy medicine, and whole medical systems) described previously.34

Table 1.

Summary of the Four Population-Based Studies Included in Current Pooled Analysis

| Study | Population | n | Ethnicity distribution | CAM question | % CAM users |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life in cancer patients (QOL) | Patients 5–6 months post-diagnosis | 118 | 35 Caucasian | Patients asked if they used CAM currently or in the past (open-ended and coded) | 39.8 |

| Study conducted: 1994–1997 | 16 Hawaiian | ||||

| Years of diagnosis: 1994–1996 | 54 Japanese | ||||

| 12 Filipino | |||||

| 1 Other | |||||

| Beating the Odds (BTO) | Patients surviving dire prognosis and controls | 47 | 11 Caucasian | Which of the following remedies have you used for your cancer?” (7 choices plus other) | 85.1 |

| Study conducted: 1998–2001 | 9 Hawaiian | ||||

| Years of diagnosis: 1978–1993 | 17 Japanese | ||||

| 5 Filipino | |||||

| 5 Other | |||||

| Subsequent Primaries (SP) | Patients developing >1 primary cancer and controls | 463 | 109 Caucasian | Patients asked if they had ever used each of 7 CAM modalities (plus open-ended other) and, if so, whether before diagnosis or during treatment and how satisfied they were | 73.2 |

| Study conducted: 1999–2003 | 72 Hawaiian | ||||

| Years of diagnosis: 1964–1999 | 200 Japanese | ||||

| 36 Filipino | |||||

| 46 Other | |||||

| Treatment Decision Making (TDM) | Patients 2 years postdiagnosis | 815 | 233 Caucasian | Patients asked if they used any of 12 CAM remedies (plus open-ended other) before diagnosis, for cancer, during treatment, and how satisfied they were | 40.2 |

| Study conducted: 2000–2003 | 132 Hawaiian | ||||

| Years of diagnosis: 1997–1999 | 254 Japanese | ||||

| 95 Filipino | |||||

| 101 Other |

CAM, complementary and alternative medicine.

Statistical analysis

Prevalence of CAM use by demographic and clinical characteristics was estimated for all cases (in situ and invasive) of breast cancer. Chi-square tests were used to assess differences in CAM use by ethnicity. Cox regression models were used to estimate the relative hazard of death due to breast cancer and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) by categories of CAM. Multivariable-adjusted survival curves using death due to breast cancer as the censoring event were determined by categories of CAM using the Breslow (or cumulative hazards) method. The final regression model was stratified by study and ethnicity and was further adjusted for continuous age at diagnosis, heart disease (no/yes), diabetes (no/yes), TNM stage (0, I: reference, II, III/IV), education (no college: reference, some college, college degree), surgery (no/yes), and chemotherapy (no/yes). Birthplace, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, and marital status were not associated with the risk of breast cancer death and were, therefore, excluded from the final model. Assuming a 12-year follow-up time, a two-tailed type I error rate of 0.05, and 1,443 participants, we had 80% power to detect a hazard ratio (HR) equal to 1.8. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3. All p values were two-sided.

Results

The median follow-up time was 11.8 years (range 0.7–37.6 years). The four studies included 1443 breast cancer cases (227 in situ), with the greatest number of cases (n=815) from the TDM study (Table 1). The prevalence of CAM use varied by study, with the lowest prevalence (39.8%) in TDM and the highest prevalence (85.1%) in the BTO study.

For all studies combined, 26.9% of participants were white, 15.9% were Native Hawaiian, 36.4% were Japanese American, 10.3% were Filipino, and 10.6% were classified as other (Table 2). The prevalence of any CAM use tended to be highest in younger women (p<0.01), women diagnosed with localized disease (p<0.01), women with diabetes (p<0.01), and women who underwent chemotherapy as part of first-course treatment (p=0.04) (Table 2). The use of any CAM was highest in Native Hawaiians (60.7%) and lowest in Japanese American (47.8%) women (p=0.02). Within specific CAM modalities, Native Hawaiian women had the highest prevalence of mind-body-based medicine use (55.0%), and Japanese American women had the lowest (35.2%, p<0.01). Filipino, Native Hawaiian, and white women tended to use WMS (25.0%, 24.9%, and 24.2%, respectively) more frequently than women of ethnicities other than white, Native Hawaiian, Japanese, and Filipino (17.7%, p<0.01).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use by Demographic and Clinical Characteristics (n=1,443)

| Characteristic | n | % | CAM | Body | Mind | Nature | Energy | WMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||||

| 25–49 | 430 | 29.8 | 60.5 | 10.5 | 49.5 | 34.9 | 14.0 | 30.2 |

| 50–59 | 384 | 26.6 | 52.6 | 5.7 | 41.9 | 23.4 | 9.9 | 21.4 |

| 60–69 | 373 | 25.8 | 48.3 | 5.4 | 35.1 | 24.9 | 7.2 | 19.0 |

| 70–95 | 256 | 17.7 | 43.8 | 3.9 | 34.8 | 19.9 | 5.5 | 16.0 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Caucasian | 388 | 26.9 | 52.1 | 9.5 | 39.2 | 27.8 | 13.7 | 24.2 |

| Hawaiian | 229 | 15.9 | 60.7 | 7.4 | 55.0 | 24.5 | 11.8 | 24.9 |

| Japanese | 525 | 36.4 | 47.8 | 5.5 | 35.2 | 28.6 | 5.1 | 20.8 |

| Filipino | 148 | 10.3 | 52.0 | 6.1 | 44.6 | 24.3 | 10.1 | 25.0 |

| Other | 153 | 10.6 | 55.6 | 3.3 | 42.5 | 22.2 | 11.1 | 17.7 |

| Education | ||||||||

| No college | 497 | 34.4 | 48.9 | 6.2 | 38.0 | 22.7 | 5.6 | 17.7 |

| Some college | 476 | 33.0 | 53.6 | 4.6 | 43.5 | 27.1 | 9.7 | 23.1 |

| College degree | 470 | 32.6 | 54.5 | 9.4 | 42.1 | 30.2 | 13.8 | 26.8 |

| Heart disease | ||||||||

| No | 1282 | 88.8 | 52.7 | 6.5 | 41.7 | 26.9 | 9.8 | 22.9 |

| Yes | 161 | 11.2 | 48.5 | 8.7 | 36.7 | 24.2 | 8.1 | 18.6 |

| Diabetes | ||||||||

| No | 1227 | 85.0 | 50.6 | 6.7 | 39.3 | 26.2 | 9.6 | 21.4 |

| Yes | 216 | 15.0 | 61.6 | 6.9 | 51.9 | 29.2 | 9.7 | 28.7 |

| TNM stage | ||||||||

| Stage I | 829 | 57.4 | 50.3 | 6.5 | 40.5 | 25.1 | 9.2 | 21.5 |

| Stage II | 157 | 10.9 | 59.9 | 4.5 | 47.1 | 30.6 | 9.6 | 24.8 |

| Stage III–IV | 230 | 15.9 | 60.4 | 10.9 | 48.3 | 32.6 | 13.5 | 30.0 |

| In situ | 227 | 15.7 | 45.8 | 4.9 | 32.2 | 23.4 | 7.5 | 16.7 |

| Surgery | ||||||||

| No | 13 | 0.9 | 61.5 | 0.0 | 31.0 | 15.4 | 23.1 | 7.7 |

| Yes | 1430 | 99.1 | 52.2 | 6.8 | 41.3 | 26.7 | 9.5 | 22.6 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||

| No | 1072 | 74.3 | 50.7 | 5.9 | 39.7 | 24.6 | 8.8 | 20.8 |

| Yes | 371 | 25.7 | 56.9 | 9.2 | 45.3 | 32.4 | 12.1 | 27.2 |

| Vital status | ||||||||

| Alive | 1141 | 79.1 | 52.3 | 7.0 | 40.9 | 27.1 | 9.7 | 22.9 |

| Death (breast cancer) | 89 | 6.2 | 65.2 | 10.1 | 47.2 | 37.1 | 18.0 | 30.3 |

| Death (other) | 213 | 14.8 | 46.5 | 3.8 | 39.9 | 19.7 | 5.6 | 16.9 |

TNM, tumor, node, metastasis; WMS, whole medical system.

In a minimal model that adjusted for age at diagnosis and stage and included study and ethnicity as strata variables, ever use of CAM was associated with a higher risk of breast cancer-specific death (HR 1.61, 95% CI 1.01, 2.56) but not all-cause mortality (Table 3). However, in the full model that adjusted for age, education, heart disease, diabetes, surgery, chemotherapy, TNM stage, and year of diagnosis and included study and ethnicity as strata variables, the associations for both end points were no longer significant. When we assessed specific CAM modalities, the use of biologically based products (HR 2.23, 95% CI 1.05-4.70) and energy medicine (HR 3.19, 95% CI 1.17-8.75) were significantly associated with an increased risk of breast cancer-specific death in the minimal model (Table 3). In the full model, only energy medicine predicted breast cancer-specific death (HR 3.01, 95% CI 1.06-8.52). None of the CAM modalities were associated with the risk of all-cause death. Restricting the analyses to invasive cases only did not change the results (data not shown). When ethnicity was included in the model as a covariate rather than a strata variable, the risk of breast cancer-specific death did not differ for that of any of the ethnic groups relative to white women; however, Japanese American women had half the risk of all-cause death (HR 0.50, 95% CI 0.37-0.68) relative to white women (data not shown).

Table 3.

Relative Hazard of Breast Cancer-Specific and All-Cause Death by Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use

| |

Death due to breast cancer |

Death due to any cause |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Model 1a |

Model 2b |

Model 1a |

Model 2b |

||||||

| n1c | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | n2c | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Any CAM use | ||||||||||

| Never | 31 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 145 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Ever | 58 | 1.61 | 1.01-2.56 | 1.47 | 0.91-2.36 | 157 | 0.94 | 0.73-1.22 | 0.82 | 0.63-1.06 |

| Specific CAM | ||||||||||

| None | 31 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 145 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Body | 0 | ∼ | ∼ | ∼ | ∼ | 1 | 0.71 | 0.10-5.13 | 0.48 | 0.07-3.49 |

| Mind | 15 | 1.12 | 0.59-2.11 | 1.05 | 0.55-2.00 | 65 | 0.90 | 0.66-1.24 | 0.82 | 0.59-1.14 |

| Nature | 11 | 2.23 | 1.05-4.70 | 1.95 | 0.91-4.17 | 19 | 0.90 | 0.66-1.24 | 0.70 | 0.42-1.17 |

| Energy | 5 | 3.19 | 1.17-8.75 | 3.01 | 1.06-8.52 | 9 | 1.50 | 0.74-3.04 | 1.31 | 0.64-2.71 |

| WMS | 27 | 1.75 | 0.99-3.09 | 1.07 | 0.58-1.96 | 63 | 0.97 | 0.70-1.36 | 0.82 | 0.58-1.16 |

Model 1: adjusted for age and TNM stage; study and ethnicity as strata variables.

Model 2: adjusted for Model 1+education, heart disease, diabetes, surgery, chemotherapy, and year of diagnosis; study and ethnicity as strata variables.

n1, number of breast cancer deaths; n2, number of deaths.

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

In fully adjusted subgroup analyses by ethnicity, ever use of CAM was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer-specific death among Filipino women (HR 6.84, 95% CI 1.23-38.19) but not all-cause death (Table 4). Further subgroup analyses suggested that this was largely attributed to the use of mind-body medicine; Filipino women who used mind-body medicine were at an increased risk of both breast cancer-specific death (HR 10.88, 95% CI 1.51-78.49) and death due to any cause (HR 3.61, 95% CI 1.24-10.48) (data not shown). White women who used biologically based products were at an increased risk of breast cancer-specific death (HR 3.83, 95% CI 1.04-14.20) (data not shown). CAM use was not associated with the risk of breast cancer-specific or all-cause death in any other subgroup.

Table 4.

Relative Hazard of Death for Ever Users of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Compared to Never Users, by Ethnicity

| |

White |

Hawaiian |

Japanese |

Filipino |

Other |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n1 | HR | 95% CI | n1 | HR | 95% CI | n1 | HR | 95% CI | n1 | HR | 95% CI | n1 | HR | 95% CI | |

| Breast cancer deaths | |||||||||||||||

| Never used CAM | 10 | 1.00 | Reference | 5 | 1.00 | Reference | 9 | 1.00 | Reference | 2 | 1.00 | Reference | 5 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Ever used CAM | 16 | 1.90 | 0.80–4.49 | 7 | 0.63 | 0.16–2.55 | 15 | 1.17 | 0.45–3.01 | 19 | 6.84 | 1.23–38.19 | 8 | 0.34 | 0.07–1.68 |

| All-cause deaths | |||||||||||||||

| Never used CAM | 54 | 1.00 | Reference | 22 | 1.00 | Reference | 48 | 1.00 | Reference | 11 | 1.00 | Reference | 10 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Ever used CAM | 43 | 0.68 | 0.43–1.08 | 39 | 1.16 | 0.61–2.20 | 42 | 0.68 | 0.41–1.12 | 18 | 2.13 | 0.89–5.11 | 15 | 0.39 | 0.12–1.28 |

Adjusted for age at diagnosis, education, heart disease, diabetes, surgery, chemotherapy, TNM stage, year of diagnosis, and study and ethnicity as strata variables.

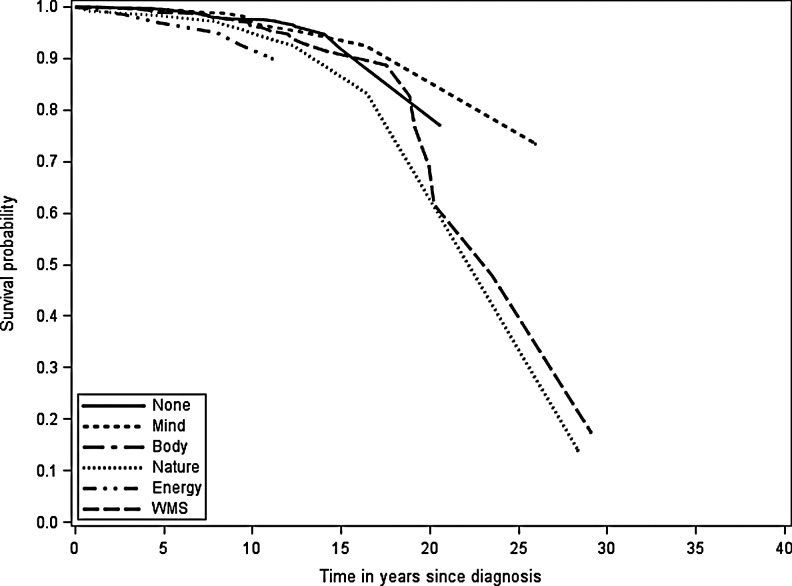

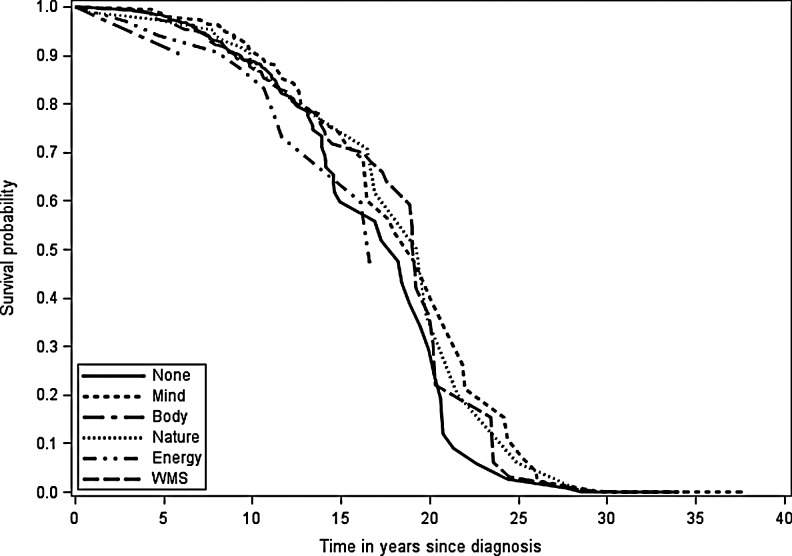

Observed breast cancer-specific and all-cause survival reflected the relative hazard of death estimates (Figs. 1 and 2). At 10 years after diagnosis, breast cancer-specific survival for women using energy medicine was worse than for women using other CAM modalities (Fig. 1). At 25 years after diagnosis, there was greater separation in survival curves, with women using biologically based products and WMS having worse survival than women not using CAM and women who used mind-body medicine. For all-cause survival, women who used manipulative and body-based practices and energy medicine appeared to have worse survival 5 years after diagnosis (Fig. 2). With longer follow-up, all women seemed to have similar all-cause survival.

FIG. 1.

Observed breast cancer-specific survival probability by complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use. WMS, whole medical system.

FIG. 2.

Observed all-cause survival probability by CAM use.

Discussion

In the current study, we observed differences in the prevalence of CAM use across ethnic groups, both overall and within specific modalities. Women who were diagnosed at later TNM stages, had surgery as part of first-course treatment, and had diabetes were more likely to use CAM. After adjusting for these and other covariates, any CAM use was not associated with breast cancer-specific death or all-cause death. There were some differences in breast cancer-specific mortality by ethnicity and CAM modality. The use of energy medicine, but not the other CAM modalities or any CAM use, was associated with a 3-fold higher risk of breast cancer-specific death. There was also evidence that biologically based products and WMS may be associated with an approximately 2-fold increased risk of breast cancer-specific death, although relative risk estimates did not quite reach statistical significance. Furthermore, we observed possible ethnic differences in the relative risk of death within specific CAM modalities. Multivariable-adjusted survival curves were in line with these results. The mechanisms for these observed differences are unclear.

Our findings that the prevalence of CAM use differs across ethnic groups are consistent with prior studies of breast cancer survivors5,35 and all cancer survivors.24,26 The existing studies evaluating CAM use and prognosis have had mixed results,1 with some suggesting an increased risk of death,17,19 others suggesting a decreased risk of death,36 but most reporting no association.18,22,37,38 Inconsistencies may arise because of heterogeneity in the CAM modalities studied, differences in the study populations with respect to clinical, demographic, and other factors that potentially affect prognosis, and nonstandardized definitions of CAM across studies.

Our study had several limitations. Patterns of CAM use among breast cancer survivors may have changed since the four studies in our analysis were conducted. However, although the patterns of CAM use and prognosis for breast cancer patients may have changed in more recent years, the relationship between CAM and prognosis is not likely to have changed substantially. We also did not have information on body mass index (BMI), which is associated with breast cancer prognosis. According to 2007 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data, higher BMI was inversely associated with CAM use.39 Therefore, BMI may have biased our estimates toward the null. In the current study, the relative risk of death and survival estimates were adjusted for factors that may be associated with BMI, particularly diabetes, but also ethnicity and education, potentially mitigating the impact of missing BMI information. We also lacked detailed treatment information, and assessment of CAM use varied slightly across the four studies. Finally, some of the subgroups by ethnicity and CAM modality were small, resulting in either unestimable hazard ratios or wide confidence intervals.

Our study had several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate long-term prognosis by ethnicity and specific CAM modality. By pooling data from four studies, we included nearly 1500 women with breast cancer. Because these women were identified through a population-based cancer registry, annual updates to their vital status could be performed, and the median follow-up time was nearly 12 years. All the studies included in this analysis were conducted in Hawaii and, therefore, included multiethnic participants, who are typically underrepresented in studies of CAM use. By categorizing CAM use according to NCCAM groupings, we achieved greater comparability with past and future studies of CAM.

Conclusions

This analysis suggests that CAM use has little effect on both all-cause death and death due to breast cancer. However, women with more adverse prognostic characteristics, for example, late stage at diagnosis, low education, no surgery, and a diagnosis of diabetes, reported higher CAM use. The increased risk of breast cancer death and worse survival observed for some modalities highlight the need for studies to distinguish between different CAM modalities and to take potential differences by ethnicity into consideration when evaluating the impact of CAM use on prognosis. Because a growing number of breast cancer patients use CAM, the potential benefits and risks of CAM need to be more rigorously studied, particularly because certain CAM therapies may interact with standard treatments. For example, mechanistic and some clinical studies have suggested that antioxidants may have a negative impact on patients receiving cytotoxic therapies. The mechanisms contributing to an increased risk of breast cancer death among women who used energy medicine needs to be better understood, whether it is the CAM itself or correlates of its use. Finally, future studies should consider using standardized definitions of CAM so that studies are more comparable over time.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Nahleh Z. Tabbara IA. Complementary and alternative medicine in breast cancer patients. Palliat Support Care. 2003;1:267–273. doi: 10.1017/s1478951503030256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alferi SM. Antoni MH. Ironson G. Kilbourn KM. Carver CS. Factors predicting the use of complementary therapies in a multi-ethnic sample of early-stage breast cancer patients. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2001;56:120–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helyer LK. Chin S. Chui BK, et al. The use of complementary and alternative medicines among patients with locally advanced breast cancer—A descriptive study. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson JW. Donatelle RJ. Complementary and alternative medicine use by women after completion of allopathic treatment for breast cancer. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10:52–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee MM. Lin SS. Wrensch MR. Adler SR. Eisenberg D. Alternative therapies used by women with breast cancer in four ethnic populations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:42–47. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLay JS. Stewart D. George J. Rore C. Heys SD. Complementary and alternative medicines use by Scottish women with breast cancer. What, why and the potential for drug interactions? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:811–819. doi: 10.1007/s00228-011-1181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saquib J. Madlensky L. Kealey S, et al. Classification of CAM use and its correlates in patients with early-stage breast cancer. Integr Cancer Ther. 2011;10:138–147. doi: 10.1177/1534735410392578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen J. Andersen R. Albert PS, et al. Use of complementary/alternative therapies by women with advanced-stage breast cancer. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2002;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong LC. Chan E. Tay S. Lee KM. Back M. Complementary and alternative medicine practices among Asian radiotherapy patients. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2010;6:357–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-7563.2010.01296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wyatt G. Sikorskii A. Wills CE. Su H. Complementary and alternative medicine use, spending, and quality of life in early stage breast cancer. Nurs Res. 2010;59:58–66. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181c3bd26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burstein HJ. Gelber S. Guadagnoli E. Weeks JC. Use of alternative medicine by women with early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1733–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906033402206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danhauer SC. Crawford SL. Farmer DF. Avis NE. A longitudinal investigation of coping strategies and quality of life among younger women with breast cancer. J Behav Med. 2009;32:371–379. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9211-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danhauer SC. Mihalko SL. Russell GB, et al. Restorative yoga for women with breast cancer: Findings from a randomized pilot study. Psychooncology. 2009;18:360–368. doi: 10.1002/pon.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lengacher CA. Johnson-Mallard V. Post-White J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) for survivors of breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:1261–1272. doi: 10.1002/pon.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matousek RH. Pruessner JC. Dobkin PL. Changes in the cortisol awakening response (CAR) following participation in mindfulness-based stress reduction in women who completed treatment for breast cancer. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2011;17:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sollner W. Maislinger S. DeVries A, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients is not associated with perceived distress or poor compliance with standard treatment but with active coping behavior: A survey. Cancer. 2000;89:873–880. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000815)89:4<873::aid-cncr21>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han E. Johnson N. DelaMelena T. Glissmeyer M. Steinbock K. Alternative therapy used as primary treatment for breast cancer negatively impacts outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:912–916. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hietala M. Henningson M. Ingvar C, et al. Natural remedy use in a prospective cohort of breast cancer patients in southern Sweden. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:134–143. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.484812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawenda BD. Kelly KM. Ladas EJ, et al. Should supplemental antioxidant administration be avoided during chemotherapy and radiation therapy? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:773–783. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenlee H. Kwan ML. Kushi LH, et al. Antioxidant supplement use after breast cancer diagnosis and mortality in the Life After Cancer Epidemiology (LACE) cohort. Cancer. 2012;118:2048–2058. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ernst E. Schmidt K. Baum M. Complementary/alternative therapies for the treatment of breast cancer. A systematic review of randomized clinical trials and a critique of current terminology. Breast J. 2006;12:526–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2006.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson JS. Workman SB. Kronenberg F. Research on complementary/alternative medicine for patients with breast cancer: A review of the biomedical literature. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:668–683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.3.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alferi SM. Carver CS. Antoni MH. Weiss S. Duran RE. An exploratory study of social support, distress, and life disruption among low-income Hispanic women under treatment for early stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2001;20:41–46. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gansler T. Kaw C. Crammer C. Smith T. A population-based study of prevalence of complementary methods use by cancer survivors: A report from the American Cancer Society's studies of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2008;113:1048–1057. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenlee H. Kwan ML. Ergas IJ, et al. Complementary and alternative therapy use before and after breast cancer diagnosis: The Pathways Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117:653–665. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0315-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maskarinec G. Shumay DM. Kakai H. Gotay CC. Ethnic differences in complementary and alternative medicine use among cancer patients. J Altern Complement Med. 2000;6:531–538. doi: 10.1089/acm.2000.6.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenlee H. Hershman DL. Jacobson JS. Use of antioxidant supplements during breast cancer treatment: A comprehensive review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:437–452. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gotay CC. Hara W. Issell BF. Maskarinec G. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in Hawaii cancer patients. Hawaii Med J. 1999;58:94–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gotay CC. Ransom S. Pagano IS. Quality of life in survivors of multiple primary cancers compared with cancer survivor controls. Cancer. 2007;110:2101–2109. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gotay CC. Blaine D. Haynes SN. Holup J. Pagano IS. Assessment of quality of life in a multicultural cancer patient population. Psychol Assess. 2002;14:439–450. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gotay CC. Holup JL. Pagano I. Ethnic differences in quality of life among early breast and prostate cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2002;11:103–113. doi: 10.1002/pon.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gotay CC. Holup J. Ethnic identities and lifestyles in a multi-ethnic cancer patient population. Pac Health Dialog. 2004;11:191–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gotay CC. Isaacs P. Pagano I. Quality of life in patients who survive a dire prognosis compared to control cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2004;13:882–892. doi: 10.1002/pon.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NCCAM publication No D347. Created October 2008, updated July 2011. nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam. [Feb 3;2012 ]. nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam

- 35.Gerber B. Scholz C. Reimer T. Briese V. Janni W. Complementary and alternative therapeutic approaches in patients with early breast cancer: A systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;95:199–209. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9005-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beuth J. Schneider B. Schierholz JM. Impact of complementary treatment of breast cancer patients with standardized mistletoe extract during aftercare: A controlled multicenter comparative epidemiological cohort study. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:523–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goodwin PJ. Weight gain in early-stage breast cancer: Where do we go from here? J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2367–2369. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pavesi L. Ceschini M. Stretched-exponential decay of the luminescence in porous silicon. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 1993;48:17625–17628. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.48.17625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertisch SM. Wee CC. McCarthy EP. Use of complementary and alternative therapies by overweight and obese adults. Obesity. 2008;16:1610–1615. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]