Abstract

Aim

Protein carbamylation through cyanate is thought to have a causal role in promoting cardiovascular disease. We recently observed that the phagocyte protein myeloperoxidase (MPO) specifically induces high-density lipoprotein carbamylation, rather than chlorination, in human atherosclerotic lesions, raising the possibility that MPO-derived chlorinating species are involved in cyanate formation.

Results

Here we show that MPO-derived chlorinating species rapidly decompose the plasma components thiocyanate and urea thereby promoting (lipo)protein carbamylation. Strikingly, the presence of physiologic concentrations of thiocyanate completely prevented MPO-induced 3-chlorotyrosine formation in HDL. Moreover, thiocyanate scavenged a 2.5-fold molar excess of hypochlorous acid, promoting HDL carbamylation, but not chlorination. Carbamylation of HDL resulted in a loss of anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative properties. Cyanate significantly impaired (i) HDL’s ability to activate lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase, (ii) the activity of paraoxonase, a major HDL-associated anti-inflammatory enzyme and (iii) the anti-oxidative activity of HDL.

Innovation

Here we report that MPO-derived chlorinating species preferentially induce protein carbamylation - rather than chlorination - in the presence of physiologically relevant thiocyanate concentrations. Carbamylation of HDL results in the loss of its anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative activities.

Conclusion

MPO-mediated decomposition of thiocyanate and/or urea might be a relevant mechanism for generating dysfunctional HDL in human disease.

Introduction

Recent studies support the hypothesis that protein carbamylation is a pathway intrinsic to inflammation and the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis (15,36). Proteins are carbamylated through cyanate, a reactive species which targets lysine residues to form ε-carbamyllysine (homocitrulline). Cyanate can also interact with cysteine or histidine groups with even higher reactivity, but in a reversible manner (33,34). Humans may be exposed to exogenous cyanate, resulting from the pyrolysis/combustion of tobacco, coal or biomass (28). Endogenously, cyanate is formed by slow breakdown of urea and myeloperoxidase (MPO)-catalyzed oxidation of thiocyanate (2,36). Thiocyanate is a major physiological substrate of MPO and accounts for approximately 50% of H2O2 consumed by MPO (35). Plasma thiocyanate levels vary upon dietary intake, with plasma levels in the range of 20 – 100 μmol/L (25). Plasma thiocyanate levels in smokers are substantially higher (16). At plasma concentrations of thiocyanate and chloride, MPO is far from being saturated, hence MPO catalyzes the oxidation of thiocyanate and chloride simultaneously (35).

Recent findings indicate that cyanate amplifies vascular inflammation linking it to uremia and smoking (10). Leukocyte-derived MPO may serve as an important catalytic source for protein carbamylation at sites of inflammation, based on the observation that protein carbamylation during peritonitis was markedly reduced in MPO-deficient mice (36). Moreover, carbamylated epitopes were found to co-localize with MPO in human atherosclerotic lesions (36).

We have recently reported that HDL is a selectively carbamylated in human atherosclerotic lesions (15). The carbamyllysine content of lesion-HDL correlated with the MPO-specific oxidation product 3-chlorotyrosine, strongly supporting the concept that leukocyte-derived MPO generates significant amounts of cyanate at sites of inflammation. These findings are in line with the observations that (i) MPO associates with HDL in atherosclerotic lesions (6,39), (ii) MPO/HDL interaction increases upon oxidation of HDL and (iii) association of MPO with HDL does not alter MPO activity (22). Interestingly, the carbamyllysine content of lesion-derived HDL is several-fold higher compared with 3-chlorotyrosine levels (15), raising the possibility that MPO-generated chlorinating species are involved in cyanate formation.

In the present study, we propose a role for MPO-derived chlorinating species in mediating rapid decomposition of urea and thiocyanate, as a novel mechanism inducing (lipo)protein carbamylation and describe that MPO-mediated cyanate formation might be an important mechanism in generating dysfunctional HDL.

Results

MPO predominantly generates carbamyllysine in the presence of thiocyanate

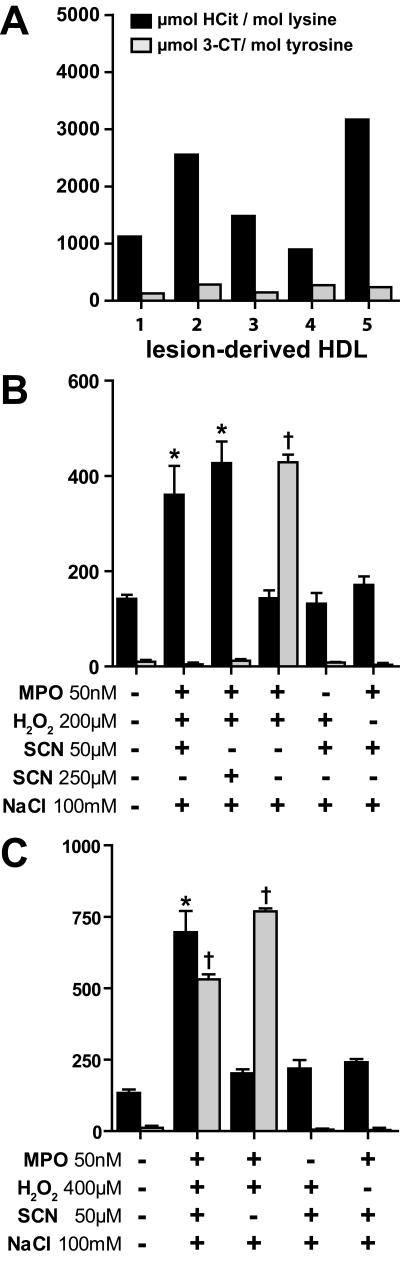

HDL isolated from human atherosclerotic lesions is mainly carbamylated, rather than chlorinated (Figure 1A), raising the possibility that in the presence of thiocyanate, MPO-induced protein carbamylation is favored over chlorination. Carbamyllysine could be detected on lesion-derived apoA-I by immunoblotting using an anti-HCit-antibody, but not on HDL isolated from peripheral blood (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 1. MPO-promoted thiocyanate decomposition induces HDL carbamylation, but not 3-chlorotyrosine formation.

(A) HDL isolated from five atherosclerotic lesions was analyzed for its homocitrulline (HCit) and 3-chlorotyrosine (3-CT) content using LC-MS/MS. (B) Reaction samples contained 2.5 mg/mL HDL, 50 nmol/L MPO, 200 μmol/L H2O2, 100 mM NaCl and thiocyanate (SCN) at 50 or 250 μmol/L. (C) Reaction samples contained 2.5 mg/mL HDL, 50 nmol/L MPO, 400 μmol/L H2O2, 100 mM NaCl and 50 μmol/L SCN.

Reactions were allowed to take place for 48 h at 37°C. Unreacted compounds were removed by gel-filtration. HCit and 3-CT were assessed using LC-MS/MS. * p<0.05, vs. HCit; † p<0.01; vs. 3-CT.

We first sought to investigate whether thiocyanate could alter MPO-induced 3-chlorotyrosine formation in HDL. Incubation of MPO in the presence of physiological- or pathological concentrations of thiocyanate (50 μmol/L or 250 μmol/L, respectively), H2O2 (200 μmol/L) and chloride (100 mmol/L) significantly induced carbamyllysine formation, whereas 3-chlorotyrosine formation was not observed (Figure 1B). When a higher excess of H2O2 (400 μmol/L) over thiocyanate (50 μmol/L) was used, carbamyllysine formation increased further and, as expected, also the formation of 3-chlorotyrosine was observed (Figure 1C). When thiocyanate was removed from the reaction mixtures, 3-chlorotyrosine formation was prominent (Figure 1B, C). In the absence of MPO or H2O2 neither carbamyllysine nor 3-chlorotyrosine formation was observed.

Hypochlorous-acid (HOCl) induces decomposition of thiocyanate and causes protein carbamylation

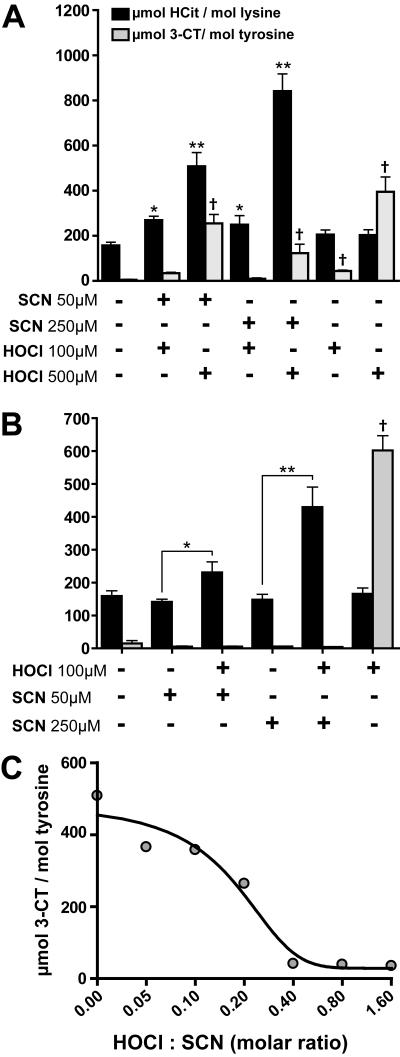

The lack of significant 3-chlorotyrosine formation indicates that thiocyanate is a preferred substrate for MPO and is particularly effective in scavenging reactive chlorinating species, as demonstrated in previous studies (3,24,27,37). Remarkably, when 100 μmol/L HOCl was added to 30 % plasma containing thiocyanate (interstitial fluids contain about 30-40 % of plasma proteins (30,32)), carbamyllysine formation was observed, whereas 3-chlorotyrosine formation was not significantly increased (Figure 2A). When HOCl was added at a higher concentration, the carbamyllysine formation further increased, depending on the thiocyanate concentration. Of note, HOCl added at higher concentrations induced 3-chlorotyrosine formation, even in the presence of thiocyanate (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. HOCl-induced decomposition of thiocyanate promotes HDL carbamylation.

(A) Human plasma (30 %) was incubated in the presence or absence of indicated concentrations of thiocyanate (SCN) and hypochlorite (HOCl) for 16 h at 37 °C. (B) HDL (2.5 mg/mL) was incubated with 50 or 250 μmol/L SCN in the presence or absence of HOCl (100 μmol/L) for 16 h at 37°C. *p<0.05 vs. HCit; **p<0.01 vs. HCit; † p<0.01; vs. 3-CT. (C) Increasing amounts of SCN (5-180 μmol/L) were incubated with 100 μmol/L HOCl for 16 h at 37°C. Unreacted compounds were removed by gel-filtration. HDL was hydrolyzed and homocitrulline (HCit) and 3-chlorotyrosine (3-CT) content were assessed using LC-MS/MS.

Similar results were obtained when HDL was incubated with thiocyanate and HOCl in the absence of serum. Under these experimental conditions, 3-chlorotyrosine formation was completely prevented (Figure 2B). The addition of HOCl in the absence of thiocyanate induced 3-chlorotyrosine formation, as expected.

To estimate the HOCl scavenging potential of thiocyanate, a fixed amount of thiocyanate was incubated with increasing concentrations of HOCl. We observed that thiocyanate completely scavenged a 2.5 fold molar excess of HOCl (Figure 2C). This indicates that over-oxidized products like cyanosulfite or sulphate are formed upon oxidation of thiocyanate with an excess of HOCl or chloroamines, as suggested in a recent study (37). These data indicate, that only in the absence of adequate thiocyanate, overproduction of HOCl by MPO might result in relevant protein chlorination.

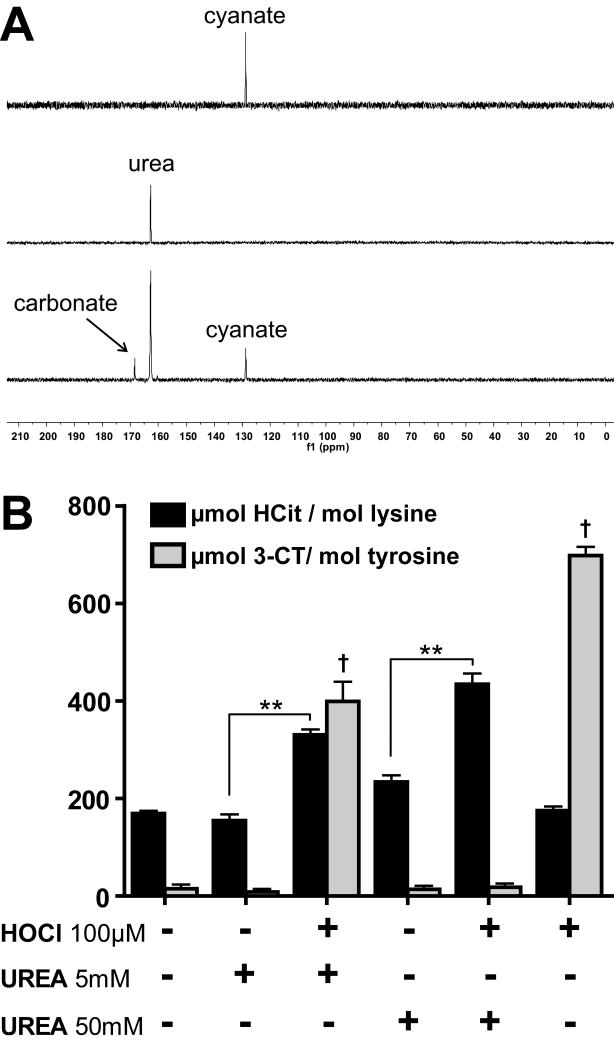

Cyanate formation through HOCl-induced decomposition of urea

Besides the formation of cyanate from thiocyanate oxidation, cyanate is known to be formed by slow decomposition of urea. It is well known that excess HOCl decomposes urea, forming nitrogen and carbon dioxide. We tested whether cyanate is formed as a byproduct. For that purpose, we investigated the decomposition of urea by HOCl using solution state NMR spectroscopy, using a 1 : 0.5 molar ratio of 13C,15N-labeled urea : HOCl. The reaction was monitored by inverse gated decoupling 13C NMR spectra. Upon the addition of HOCl the signal of urea (at 162.8 ppm) decreased within the dead time of the experiment (3 min) and peaks for carbonate and cyanate appeared at 168.5 and 128.7 ppm, respectively (Figure 3A). Longer incubations did not further increase the signal intensity of cyanate, indicating the rapid formation of cyanate. About 25 % of urea is converted to cyanate, demonstrating that high yields of cyanate are formed upon HOCl-induced decomposition of urea. Notably, the addition of HOCl (100 μM) to urea levels observed in control subjects (5 mmol/L) induced significant protein carbamylation and 3-chlorotyrosine formation. Notably, in the presence of high urea concentrations (50 mmol/L, observed in renal patients) the addition of HOCl significantly amplified protein carbamylation, but did not result in 3-chlorotyrosine formation, whereas the addition of HOCl alone induced only 3-chlorotyrosine formation (Figure 3B). High urea concentrations on its own tended to induce protein carbamylation, but only in the presence of HOCl was the extent of carbamylation significantly increased. Based on these results it can be concluded that MPO-derived chlorinating species induce (lipo)protein carbamylation through oxidation of thiocyanate and/or rapid decomposition of urea.

Figure 3. HOCl-induced rapid decomposition of urea generates cyanate.

(A) One-dimensional 13C-NMR spectra of potassium cyanate (upper panel), of 13C,15N-labeled urea (162 ppm) (middle panel) and 13C,15N-labeled urea incubated with 0.5 molar equivalents of HOCl for 3 min (lower panel). Besides the main product cyanate (128 ppm) carbonate was also detected (160 ppm) by inverse gated decoupling 13C NMR spectra. (B) HOCl-induced decomposition of urea results in protein carbamylation. HDL was incubated with 5 or 50 mmol/L urea in presence or absence of HOCl (100 μmol/L) for 16 h at 37°C. Unreacted compounds were removed by gel-filtration, Homocitrulline (HCit) and 3-chlorotyrosine (3-CT) were assessed using LC-MS/MS. ** p<0.01, vs. HCit; † p<0.01; vs. 3-CT.

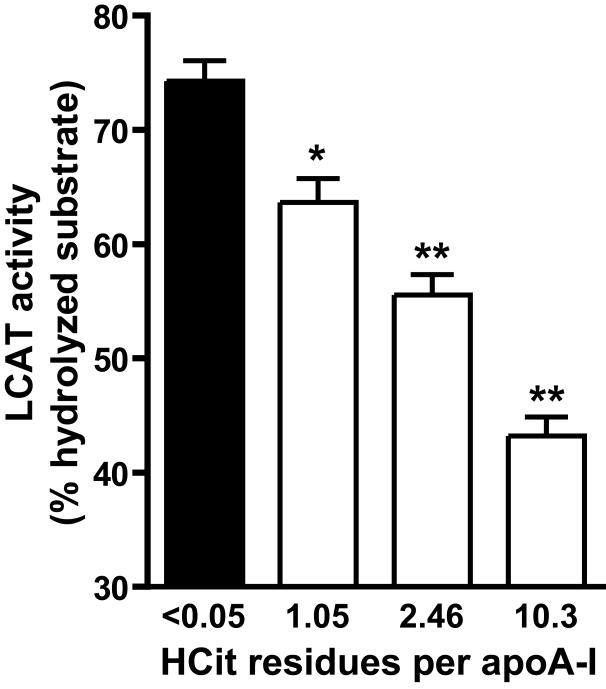

Carbamylated HDL is a less potent substrate for lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT)

LCAT drives the maturation of nascent HDL into spherical HDL, an essential step in reverse cholesterol transport. To assess whether carbamylation of HDL alters LCAT activity, a commercially available assay for serum/plasma LCAT activity was used to measure the efficiency of different HDL preparations to activate LCAT. For that purpose, HDL was labeled with a fluorescent LCAT substrate, which changes its fluorescence emission wavelength from 390 to 460 nm upon hydrolysis by LCAT. The labeled substrate was rapidly incorporated into HDL (Supplemetary Figure S1). The labeled HDL preparations were incubated with a fixed amount of lipoprotein deficient serum as a source for LCAT. As seen in Figure 4, carbamylation dose-dependently decreased the ability of HDL to activate LCAT.

Figure 4. Carbamylation decreases the ability of HDL to activate LCAT.

Native or carbamylated HDL preparations (100 μg/mL) were labeled with a fluorescent LCAT substrate and incubated for 5 h at 37°C with lipoprotein-deficient serum as a source of LCAT. The change in LCAT substrate fluorescence was used to assess LCAT activity. Results represent the mean of duplicate determinations + SEM of three independent experiments. *p<0.05; **p<0.01.

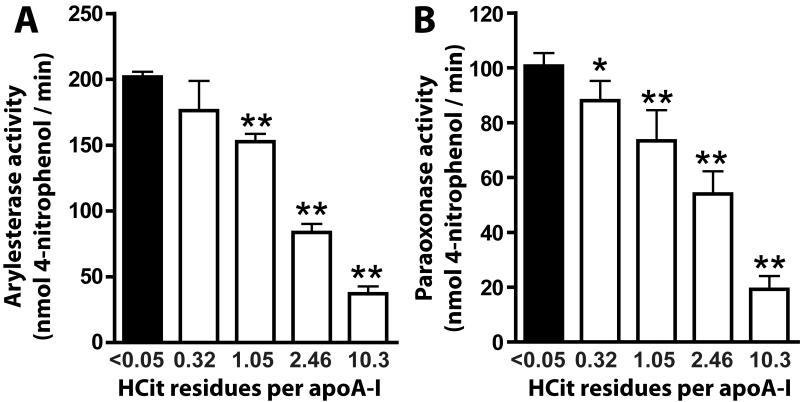

Carbamylation reduces the anti-oxidant properties of HDL and decreases the activity of HDL-associated paraoxonase (PON)

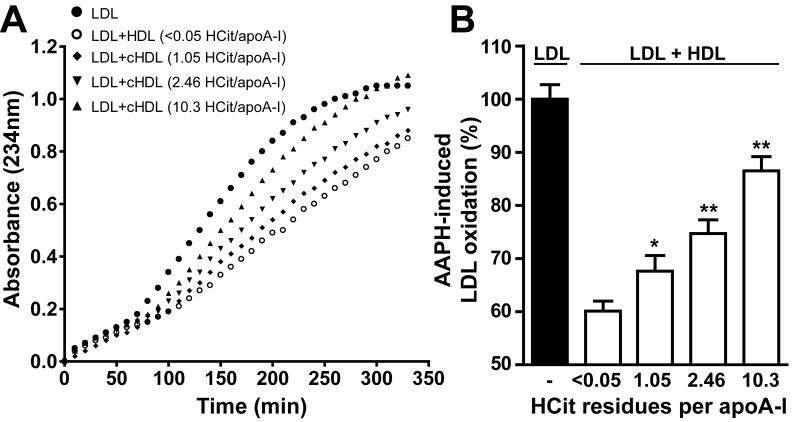

Besides the important role of HDL in lipid metabolism, it also exhibits unique anti-oxidative activity. We investigated the ability of HDL to inhibit radical-induced LDL oxidation. LDL was incubated with the radical inducer 2,2′-azobis-2-methyl-propanimidamide dihydrochloride (AAPH) and a characteristic oxidation curve with lag time and propagation phase was obtained (Figure 5A). The oxidation of LDL could be markedly inhibited by addition of native HDL. However, the ability of HDL to inhibit radical-induced oxidation was significantly decreased upon carbamylation (Figure 5B), which indicates that carbamylation impairs the anti-oxidative properties of HDL.

Figure 5. Carbamylation decreases the ability of HDL to prevent LDL oxidation.

LDL (100 μg/mL) was incubated with AAPH (a free radical inducer) in the presence or absence of HDL (100 μg/mL). (A) A representative time course of an AAPH-induced oxidation process is monitored at 234 nm for 350 min. (B) One time point in the propagation phase (200 min) was selected for quantification. Oxidation in presence of HDL was calculated as a relative value to oxidation of LDL alone, which was set to 100 %. Results represent the mean of triplicate determinations + SEM of three independent experiments.

Recent data suggest that the HDL-associated enzymes PON and LCAT are involved in the anti-oxidant activity of HDL (4,5,13). We analyzed the impact of protein carbamylation on PON-associated paraoxonase and arylesterase activity. Strikingly, when HDL was exposed to cyanate inducing minimal carbamylation, paraoxonase (Figure 6A) and arylesterase activities (Figure 6B) of PON were significantly reduced. PON activity further decreased when HDL was modified with higher cyanate concentrations.

Figure 6. Carbamylation decreases activity of HDL-associated paraoxonase (PON).

(A) Arylesterase activity of HDL-associated PON was measured using phenylacetate as substrate (HDL, 20 μg/mL). (B) Paraoxonase activity of HDL-associated PON was measured using paraoxon as substrate (HDL, 50 μg/mL). The paraoxonase and arylesterase activities of PON were calculated from the slopes of three independent experiments and were expressed as means + SEM. *p<0.05; **p<0.01

Discussion

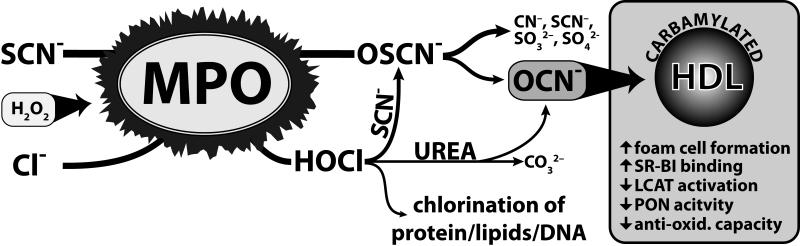

Carbamylated (lipo)proteins are risk factors for cardiovascular disease and seem to have a causal role in disease progression. It was long thought that cyanate formation occurs to a significant extent only during renal dysfunction through the slow decomposition of urea. Approximately, 0.8 % of urea decomposes to cyanate within one week in aqueous solution (8). However, recent studies have unambiguously demonstrated that humans are exposed to additional significant amounts of cyanate formed by pyrolysis/combustion of coal, biomass or tobacco (28), and that cyanate formation is catalyzed by the leukocyte heme-peroxidase MPO (2,36). Here we provide novel evidence of an alternative mechanism for cyanate formation. MPO-derived chlorinating species rapidly decompose thiocyanate and/or urea, forming cyanate therby promoting (lipo)protein carbamylation (Figure 7). Physiologic concentrations of thiocyanate prevented 3-chlorotyrosine formation in HDL, suggesting that MPO preferentially induces protein carbamylation - rather than chlorination - at sites of inflammation. This is in good agreement with the finding that the carbamyllysine content of lesion-derived HDL was more than 20-fold higher in comparison to 3-chlorotyrosine levels, a specific oxidation product of MPO (15). In line with our observations, it was recently demonstrated that thiocyanate effectively scavenges HOCl and protein-associated chloramines, forming cyanate and sulphate (37). This is in agreement with a study showing that the rate constant for the reaction of thiocyanate with chloramines is comparable to the rate constants for the best proteinaceous nucleophiles cysteine and methionine (26).

Figure 7. Cyanate generation by MPO-derived reactive species.

A schematic illustration summarizing MPO-mediated pathways generating cyanate (OCN−). MPO oxidizes thiocyanate (SCN−) and chloride (Cl−) in the presence of H2O2 to hypothiocyanate (OSCN−) and hypochlorite (HOCl). OSCN− decomposes to cyanate (OCN−) and to a variety of other compounds such as cyanide (CN−), sulfite (SO32−), sulfate (SO42−), or back to SCN− (18). HOCl oxidizes SCN− to OSCN− (3), thereby increasing the formation of OCN−. Decomposition of urea through HOCl generates OCN− and carbonate. Cyanate induced carbamylation results in a reduction of potential athero-protective functions of HDL.

Interestingly, hypothiocyanate itself was reported to react even faster with chloramines than thiocyanate (37), likely explaining that in the present study, low concentrations of thiocyanate completely blocked 3-chlorotyrosine formation, since lysinechloramine formation is reported to be involved in tyrosine chlorination (9).

Another important observation in the present study is that the major MPO product HOCl decomposes urea generating high yields of cyanate. Our findings may be of particular relevance, since urea levels can reach 100 mmol/L in patients with chronic renal failure, and elevated MPO activity was demonstrated in patients undergoing hemodialysis with high-grade persistent inflammation (29). Therefore, increased decomposition of urea may generate high yields of cyanate at sites of inflammation. In line with our data, it was previously reported that MPO-containing neutrophils and monocytes of patients with chronic renal disease are highly enriched with carbamylated proteins compared with control subjects (20). The localization of phagocytes in the immediate vicinity of endothelial cells at sites of inflammation may contribute to cyanate-induced expression of endothelial intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1, as observed recently (10). This raises the possibility that cyanate increases endothelial-leukocyte interaction thus forming a vicious circle. In this respect, it was shown that serum MPO levels correlate with levels of inflammatory markers and with mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis (17).

In line with our previous results (15), we observed that carbamyllysine levels are markedly elevated in HDL isolated from human atherosclerotic tissue. These results are in line with previous findings that MPO binds to HDL within human atherosclerotic lesions and might produce reactive species in closest proximity to HDL (6,15,23,39). Interestingly, HDL derived from atherosclerotic lesions was mainly carbamylated - rather than chlorinated - suggesting that MPO-generated chlorinating species are involved in cyanate formation.

In the present study we report that carbamylation of HDL significantly impaires its ability to activate LCAT, an enzyme essential for cholesterol esterification and maturation of HDL. Apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) is recognized as a major activator of LCAT in HDL, however, the mechanism by which apoA-I facilitates cholesterol esterification and particle maturation remains unclear. Previous studies have shown that mutation of charged residues in apoA-I results in marked reductions of LCAT activity, indicating that the elimination of positive charge through carbamylation of apoA-I lysine residues may cause reduced LCAT activity (1). Importantly, cyanate not only targets lysine residues, but also phosphatidyethanolamine (15) and interacts with cysteine groups with even higher reactivity (34). Therefore, the decrease in LCAT activating capability of cyanate-treated HDL might be the result of modification of several reactive groups in HDL-associated apoproteins, enzymes and phospholipids.

In a previous study, we observed that carbamylation increases the binding affinity of HDL to its physiological receptor, scavenger receptor B-I (SR-BI), thereby causing intracellular cholesterol accumulation and lipid-droplet formation in macrophages (15). According to our present study, these data raise the possibility that loss of functional HDL/SR-BI interaction and LCAT-activating ability - as induced by carbamylation - results in impaired reverse-cholesterol transfer capacity.

The anti-atherogenic effect of HDL has been attributed to several mechanisms, including the prevention of LDL oxidation. HDL-mediated inactivation of LDL-associated phospholipid-hydroperoxides involves initial transfer from LDL to HDL, which is governed by the rigidity of the surface monolayer of HDL, and subsequent reduction of hydroperoxides by redox-active methionine residues of apolipoproteins (12,19,38). HDL-associated enzymes may in turn contribute to the hydrolytic inactivation of short-chain oxidized phospholipids. Paraoxonase (PON) is a HDL-associated enzyme hydrolyzing various lactones and organophosphates and was shown to metabolize lipoprotein-associated oxidized lipids (5,21). Importantly, PON was shown to selectively decrease lipid-peroxides in human coronary and carotid atherosclerotic lesions (4) and to protect against atherosclerosis and coronary artery diseases (31). Therefore, the decrease in anti-oxidant activity of carbamylated HDL may be the result of decreased PON activity. However, other cyanate-induced modifications of the protein and phospholipid moiety of HDL may contribute to the impaired anti-oxidative capacity.

In summary, the present study has identified novel mechanisms of protein carbamylation highlighting the link of inflammation and cardiovascular disease with uremia, smoking and air pollution. Carbamylation of HDL in the atherosclerotic intima might critically impair anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of HDL, thereby promoting the development of atherosclerosis.

Innovation

Carbamylation of (lipo)proteins through cyanate generates novel risk factors for cardiovascular disease and are thought to have a causal role in disease progression. We have recently observed that the phagocyte protein myeloperoxidase (MPO) preferentially induces high-density lipoprotein (HDL) carbamylation, rather than chlorination, in human atherosclerotic lesions, raising the possibility that MPO-derived chlorinating species are involved in cyanate formation.

Here we report that MPO-derived reactive chlorinating species promote carbamylation of proteins through decomposition of urea and thiocyanate. Physiological concentrations of thiocyanate prevented 3-chlorotyrosine formation in proteins, suggesting that MPO preferentially induces protein carbamylation - rather than chlorination - at sites of inflammation. Urea levels can reach 100 mmol/L in patients with chronic renal failure; hence a augmented decomposition of urea may generate high yields of cyanate. Importantly, elevated MPO activity was recently demonstrated in patients with inflammation undergoing hemodialysis, supporting the association between inflammation and cumulative oxidative stress. Moreover, here we demonstrate that minimal carbamylation of HDL significantly impairs (i) HDL’s ability to activate lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase, an enzyme essential for cholesterol esterification and HDL maturation, (ii) the activity of the major HDL-associated anti-inflammatory enzyme paraoxonase and (iii) the anti-oxidative capability of HDL. Thus, carbamylation of HDL in the atherosclerotic intima might critically hamper the anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of HDL. These data raise the possibility that protein carbamylation links inflammation, uremia and cardiovascular disease.

Material and Methods

13C,15N-labeled urea was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA, USA). Homocitrulline (carbamyllysine) was purchased from Bachem (Weil am Rhein, Germany) and 13C6-homocitrulline from Ascent Scientific (Bristol, UK), respectively. LCAT activity kit was purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Myeloperoxidase was supplied by Enzo Life Science (Vienna, Austria). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma (Vienna, Austria) unless otherwise specified.

Blood collection

Blood was sampled from healthy volunteers after an informed consent, according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical University of Graz (14).

Isolation of lipoproteins

For lipoprotein isolation, serum density from normolipidemic blood donors was adjusted with KBr to 1.24 g/ml. To optimize lipoprotein separation, long centrifuge tubes (16 × 76 mm; Beckman) were used. A two-layer density gradient was generated by layering the density-adjusted serum (1.24 g/ml) underneath phosphate buffered saline (1.006 g/ml). Tubes were sealed and centrifuged at 90.000 rpm for 4 hours in a 90TI fixed angle rotor (Beckman Instruments, Krefeld, Germany). After centrifugation, the two clearly separated HDL- and LDL-containing bands were collected, desalted via a PD10 column (GE Healthcare, Vienna, Austria) and directly used for experiments. HDL-like particles from human atherosclerotic tissue were isolated as previously described (15).

Modification of HDL

HDL was carbamylated with potassium cyanate as described previously (15). MPO-mediated modification of HDL was performed in 50 mmol/L phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Reaction samples contained 2.5 mg/mL HDL, 50 nmol/L MPO, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 200 or 400 μmol/L H2O2 and 50 or 250 μmol/L thiocyanate. The reactions were allowed to take place for 48 hours at 37°C. Afterwards, samples were placed on ice to stop the reaction and unreacted compounds were removed by gel-filtration. Carbamylation was assessed by LC-MS/MS.

HOCl-induced decomposition of thiocyanate/urea

Thiocyanate (50 - 250 μmol/L) or urea (5 - 50 mmol/L) in PBS were mixed with HOCl (100 μmol/L) and immediately added to a 2.5 mg/mL HDL solution. The reaction mixture was incubated for 16 hours at 37°C. For experiments with human plasma, total plasma was diluted with PBS to 30 %. The diluted plasma was incubated in the absence or presence of 50 or 250 μmol/L thiocyanate and 100 or 500 μmol/L HOCl for 16 hours at 37°C. Afterwards, unreacted compounds were removed by gel-filtration and protein carbamylation was assessed by LC-MS/MS.

NMR spectroscopy

All spectra were recorded on a Bruker 700 MHz Avance III NMR spectrometer, equipped with a 5 mm TCI cryo probe. Inverse gated proton-decoupled 13C-spectra were acquired with 128 scans and an interscan delay of 2 seconds. The pulse-width corresponded to a flip angle of ~30° to reduce any saturation in the spectra. A solution of 50 mM 13C, 15N-labeled urea was mixed with a 750 mM stock solution of HOCl yielding a final concentration of 25 mM HOCl. The experiments were carried out in a PBS buffer (pH 7.4) at 298 K.

Quantification of carbamyllysine and 3-chlorotyrosine

Proteins were hydrolyzed with a fast, low-volume hydrolysis method as described (7). To quantify carbamyllysine and chlorotyrosine formation in HDL, electrospray ionization liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) was used as described previously (15).

Paraoxonase/arylesterase activity assay

Ca2+-dependent paraoxonase (PON) activity was determined as the rate of hydrolysis of paraoxon into 4-nitrophenol, which can be monitored by an increase in absorbance at 405 nm (11). Native or carbamylated HDL (10 μg protein) was placed into a 96-well plate and the reaction was initiated by the addition of 200 μL buffer containing 100 mmol/L Tris, 2 mmol/L CaCl2, 1 mmol/L paraoxon (pH 8.0). The assay was performed at 37°C and readings were taken every 5 minutes at 405 nm on a plate reader to generate a kinetic plot. The slope from the kinetic chart was used to determine ΔAbs405nm / min. Enzymatic activity was calculated with the Beer-Lambert Law from the molar extinction coefficient of 17100 mol*l−1*cm−1. PON activities were expressed as nmol/L 4-nitrophenol formed per minute.

Ca2+-dependent arylesterase activity was determined with a photometric assay using phenylacetate as the substrate (11). Native or carbamylated HDL (2 μg protein) was added to 200 μL buffer containing 100 mmol/L Tris, 2 mmol/L CaCl2 (pH 8.0) and phenylacetate (1 mmol/L). The rate of hydrolysis of phenylacetate was monitored by the increase of absorbance at 270 nm and readings were taken every 30 seconds at room temperature to generate a kinetic plot. The slope from the kinetic chart was used to determine ΔAbs270nm / min. Enzymatic activity was calculated with the Beer-Lambert Law from the molar extinction coefficient of 1310 L*mol−1*cm−1 for phenylacetate.

Carbamylation of HDL and assessment of LCAT activity

LCAT activity was measured using a commercially available kit (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), which was adapted to measure substrate efficiency of HDL preparations. For that purpose, native or carbamylated HDL was pre-incubated with LCAT substrate for 90 minutes at 37°C and unbound substrate was removed using gel-filtration. The binding efficiency was ~95% of the added substrate, determined by fluorescence measurement of the substrate at 470 nm after gel-filtration. The labeled HDL preparations were used to determine the substrate efficiency in response to LCAT enzymatic activity. Lipoprotein-deficient serum (LPDS) was used as the source for LCAT.

The experimental setting was as follows: 100 μg labeled HDL and 10 μL LPDS were completed with LCAT buffer to 200 μL. LCAT buffer contained 150 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L TRIS, 4 mmol/L mercaptoethanol and 1 mmol/L EDTA.

Endpoint readouts were obtained after incubation for 5 hours at 37°C. Results are expressed as percent of substrate hydrolyzed.

Determination of the anti-oxidative capacity of HDL

The anti-oxidative activity of HDL was determined as described previously (69,120). LDL (100 μg/mL protein) was oxidized in-vitro with the free radical initiator 2,2′-azobis-2-methylpropanimidamide-dihydrochloride (AAPH) (1 mmol/L in PBS) in the presence or absence of HDL (100 μg/mL protein) at 37°C. The oxidation was monitored at 234 nm. A time point in the propagation phase (at 200 min) was selected to assess the anti-oxidant activity of HDL. Oxidation in presence of HDL was calculated as relative to oxidation of LDL alone, which was set to 100 %.

Statistical analyses

Data are shown as mean + SEM for n observations unless otherwise stated. Comparison between 2 groups was performed with Student’s t-test and between multiple groups using One-Way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test. Significance was accepted at probability levels of p < 0.05 and p < 0.01. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism version 4.03.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding Michael Holzer and Sanja Curcic were funded by the PhD Program Molecular Medicine of the Medical University of Graz. This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund FWF FWF (Grants P21004-B02, P22521-B18, P22976-B18, P20020 and P22630).

List of Abbreviations

- AAPH

2,2′-azobis-2-methyl-propanimidamide dihydrochloride

- ApoA-I

Apolipoprotein A-I

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- 3-CT

3-chlorotyrosine

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- HCit

homocitrulline, carbamyllysine

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- HOCl

hypochlorous acid

- LCAT

lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LPDS

lipoprotein deficient serum

- Lys

lysine

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- OSCN−

hypothiocyanate

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PON

paraoxonase

- SCN

thiocyanate

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Alexander ET, Bhat S, Thomas MJ, Weinberg RB, Cook VR, Bharadwaj MS, Sorci-Thomas M. Apolipoprotein A-I helix 6 negatively charged residues attenuate lecithincholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) reactivity. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5409–5419. doi: 10.1021/bi047412v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arlandson M, Decker T, Roongta VA, Bonilla L, Mayo KH, MacPherson JC, Hazen SL, Slungaard A. Eosinophil peroxidase oxidation of thiocyanate. Characterization of major reaction products and a potential sulfhydryl-targeted cytotoxicity system. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:215–224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004881200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashby MT, Carlson AC, Scott MJ. Redox buffering of hypochlorous acid by thiocyanate in physiologic fluids. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15976–15977. doi: 10.1021/ja0438361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aviram M, Hardak E, Vaya J, Mahmood S, Milo S, Hoffman A, Billicke S, Draganov D, Rosenblat M. Human serum paraoxonases (PON1) Q and R selectively decrease lipid peroxides in human coronary and carotid atherosclerotic lesions: PON1 esterase and peroxidase-like activities. Circulation. 2000;101:2510–2517. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.21.2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aviram M, Rosenblat M, Bisgaier CL, Newton RS, Primo-Parmo SL, La Du BN. Paraoxonase inhibits high-density lipoprotein oxidation and preserves its functions. A possible peroxidative role for paraoxonase. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1581–1590. doi: 10.1172/JCI1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergt C, Pennathur S, Fu X, Byun J, O’Brien K, McDonald TO, Singh P, Anantharamaiah GM, Chait A, Brunzell J, Geary RL, Oram JF, Heinecke JW. The myeloperoxidase product hypochlorous acid oxidizes HDL in the human artery wall and impairs ABCA1-dependent cholesterol transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13032–13037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405292101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damm M, Holzer M, Radspieler G, Marsche G, Kappe CO. Microwave-assisted high-throughput acid hydrolysis in silicon carbide microtiter platforms--a rapid and low volume sample preparation technique for total amino acid analysis in proteins and peptides. J Chromatogr A. 2010;1217:7826–7832. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dirnhuber P, Schutz F. The isomeric transformation of urea into ammonium cyanate in aqueous solutions. Biochem J. 1948;42:628–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domigan NM, Charlton TS, Duncan MW, Winterbourn CC, Kettle AJ. Chlorination of tyrosyl residues in peptides by myeloperoxidase and human neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16542–16548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Gamal D, Holzer M, Gauster M, Schicho R, Binder V, Konya V, Wadsack C, Schuligoi R, Heinemann A, Marsche G. Cyanate is a novel inducer of endothelial icam-1 expression. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;16:129–137. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gan KN, Smolen A, Eckerson HW, La Du BN. Purification of human serum paraoxonase/arylesterase. Evidence for one esterase catalyzing both activities. Drug Metab Dispos. 1991;19:100–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garner B, Waldeck AR, Witting PK, Rye KA, Stocker R. Oxidation of high density lipoproteins. II. Evidence for direct reduction of lipid hydroperoxides by methionine residues of apolipoproteins AI and AII. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6088–6095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goyal J, Wang K, Liu M, Subbaiah PV. Novel function of lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase. Hydrolysis of oxidized polar phospholipids generated during lipoprotein oxidation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16231–16239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holzer M, Birner-Gruenberger R, Stojakovic T, El-Gamal D, Binder V, Wadsack C, Heinemann A, Marsche G. Uremia Alters HDL Composition and Function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1631–1641. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010111144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holzer M, Gauster M, Pfeifer T, Wadsack C, Fauler G, Stiegler P, Koefeler H, Beubler E, Schuligoi R, Heinemann A, Marsche G. Protein carbamylation renders high-density lipoprotein dysfunctional. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:2337–2346. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Husgafvel-Pursiainen K, Sorsa M, Engstrom K, Einisto P. Passive smoking at work: biochemical and biological measures of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1987;59:337–345. doi: 10.1007/BF00405277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Brennan ML, Hazen SL. Serum myeloperoxidase and mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:59–68. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalmar J, Woldegiorgis KL, Biri B, Ashby MT. Mechanism of Decomposition of the Human Defense Factor Hypothiocyanite Near Physiological pH. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19911–19921. doi: 10.1021/ja2083152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kontush A, Chapman MJ. Antiatherogenic function of HDL particle subpopulations: focus on antioxidative activities. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21:312–318. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32833bcdc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraus LM, Elberger AJ, Handorf CR, Pabst MJ, Kraus AP., Jr Urea-derived cyanate forms epsilon-amino-carbamoyl-lysine (homocitrulline) in leukocyte proteins in patients with end-stage renal disease on peritoneal dialysis. J Lab Clin Med. 1994;123:882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackness MI, Arrol S, Durrington PN. Paraoxonase prevents accumulation of lipoperoxides in low-density lipoprotein. FEBS Lett. 1991;286:152–154. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80962-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marsche G, Furtmuller PG, Obinger C, Sattler W, Malle E. Hypochlorite-modified high-density lipoprotein acts as a sink for myeloperoxidase in vitro. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:187–194. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marsche G, Hammer A, Oskolkova O, Kozarsky KF, Sattler W, Malle E. Hypochlorite-modified high density lipoprotein, a high affinity ligand to scavenger receptor class B, type I, impairs high density lipoprotein-dependent selective lipid uptake and reverse cholesterol transport. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32172–32179. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200503200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan PE, Pattison DI, Talib J, Summers FA, Harmer JA, Celermajer DS, Hawkins CL, Davies MJ. High plasma thiocyanate levels in smokers are a key determinant of thiol oxidation induced by myeloperoxidase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1815–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olea F, Parras P. Determination of serum levels of dietary thiocyanate. J Anal Toxicol. 1992;16:258–260. doi: 10.1093/jat/16.4.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pattison DI, Davies MJ. Reactions of myeloperoxidase-derived oxidants with biological substrates: gaining chemical insight into human inflammatory diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:3271–3290. doi: 10.2174/092986706778773095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pattison DI, Hawkins CL, Davies MJ. What are the plasma targets of the oxidant hypochlorous acid? A kinetic modeling approach. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22:807–817. doi: 10.1021/tx800372d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts JM, Veres PR, Cochran AK, Warneke C, Burling IR, Yokelson RJ, Lerner B, Gilman JB, Kuster WC, Fall R, de Gouw J. Isocyanic acid in the atmosphere and its possible link to smoke-related health effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:8966–8971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103352108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez-Ayala E, Anderstam B, Suliman ME, Seeberger A, Heimburger O, Lindholm B, Stenvinkel P. Enhanced RAGE-mediated NFkappaB stimulation in inflamed hemodialysis patients. Atherosclerosis. 2005;180:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutili G, Arfors KE. Protein concentration in interstitial and lymphatic fluids from the subcutaneous tissue. Acta Physiol Scand. 1977;99:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1977.tb10345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.She ZG, Chen HZ, Yan Y, Li H, Liu DP. The Human Paraoxonase Gene Cluster as a Target in the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011 doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith EB, Staples EM. Distribution of plasma proteins across the human aortic wall--barrier functions of endothelium and internal elastic lamina. Atherosclerosis. 1980;37:579–590. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(80)90065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.STARK GR. Reactions of Cyanate with Functional Groups of Proteins. Ii. Formation, Decomposition, and Properties of N-Carbamylimidazole. Biochemistry. 1965;4:588–595. doi: 10.1021/bi00879a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.STARK GR. On the Reversible Reaction of Cyanate with Sulfhydryl Groups and the Determination of Nh2-Terminal Cysteine and Cystine in Proteins. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:1411–1414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Dalen CJ, Whitehouse MW, Winterbourn CC, Kettle AJ. Thiocyanate and chloride as competing substrates for myeloperoxidase. Biochem J. 1997;327(Pt 2):487–492. doi: 10.1042/bj3270487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Z, Nicholls SJ, Rodriguez ER, Kummu O, Horkko S, Barnard J, Reynolds WF, Topol EJ, DiDonato JA, Hazen SL. Protein carbamylation links inflammation, smoking, uremia and atherogenesis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1176–1184. doi: 10.1038/nm1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xulu BA, Ashby MT. Small molecular, macromolecular, and cellular chloramines react with thiocyanate to give the human defense factor hypothiocyanite. Biochemistry. 2010;49:2068–2074. doi: 10.1021/bi902089w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zerrad-Saadi A, Therond P, Chantepie S, Couturier M, Rye KA, Chapman MJ, Kontush A. HDL3-mediated inactivation of LDL-associated phospholipid hydroperoxides is determined by the redox status of apolipoprotein A-I and HDL particle surface lipid rigidity: relevance to inflammation and atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:2169–2175. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.194555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zheng L, Nukuna B, Brennan ML, Sun M, Goormastic M, Settle M, Schmitt D, Fu X, Thomson L, Fox PL, Ischiropoulos H, Smith JD, Kinter M, Hazen SL. Apolipoprotein A-I is a selective target for myeloperoxidase-catalyzed oxidation and functional impairment in subjects with cardiovascular disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:529–541. doi: 10.1172/JCI21109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.