To the Editor: Rickettsia africae is the most widespread spotted fever group (SFG) rickettsia in sub-Saharan Africa, where it causes African tick-bite fever (1), an acute, influenza-like syndrome. The number of cases in tourists returning from safari in sub-Saharan Africa is increasing (1). In western, central, and eastern sub-Saharan Africa, R. africae is carried by Amblyomma variegatum (Fabricius, 1794) ticks (2); usually associated with cattle, this 3-host tick also can feed on a variety of hosts, including humans (2). R. africae has not been reported in Uganda and rarely reported in Nigeria (3,4). Our objective was to determine the potential risk for human infection by screening for rickettsial DNA in A. variegatum ticks from cattle in Uganda and Nigeria.

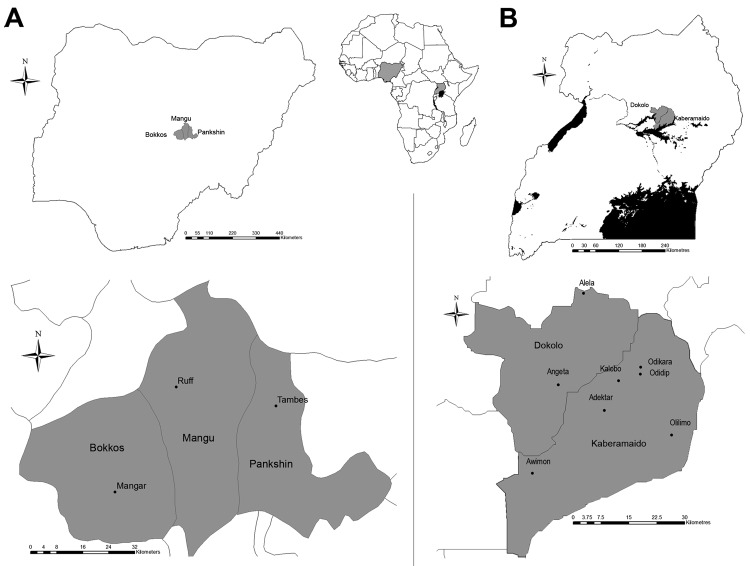

In February 2010, ticks were collected from zebu cattle (Bos indicus) from 8 villages in the districts of Kaberamaido (Adektar [1°81′ N–33°22′ E], Awimon [1°66′ N–33°04′ E], Kalobo [1°88′ N–33°25′ E], Odidip [1°90′ N–33°30′ E], and Odikara [1°91′ N–33°30′ E], Olilimo [1°75′ N–33°38′ E], and Dokolo (Alela [2°09′ N–33°16′ E], and Angeta [1°87′ N–33°10′ E]) in Uganda and, in June 2010, in 3 villages (Mangar [9°14′ N–8°93′ E], Ruff [9°43′ N–9°10′ E], and Tambes [9°38′ N–9°38′ E]) in the Plateau State in Nigeria (Figure). This convenience sample was obtained as part of other ongoing research projects in both countries. Ticks were preserved in 70% ethanol and identified morphologically to the species level by using taxonomic keys (5). Because the anatomic features do not enable an objective assessment of the feeding status of adult male ticks, engorgement level was determined only in female tick specimens and nymphs.

Figure.

Location of areas studied for Rickettsia africae in Amblyomma variegatum ticks in Nigeria (A) and Uganda (B), 2010.

After tick identification, DNA was extracted from ticks by using QIAmp DNeasy kits (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Two PCR targets were assessed within each sample; the primer pair Rp.CS.877p and RpCS.1258n was selective for a 396-bp fragment of a highly conserved gene encoding the citrate synthase (gltA) shared by all Rickettsia spp. (6); the Rr190–70p and Rr190–701n primer pair amplified a 629–632-bp fragment of the gene encoding the 190-kD antigenic outer membrane protein A (ompA), common to all SFG rickettsiae (6,7). DNA extracted from 2 A. variegatum tick cell lines (AVL/CTVM13 and AVL/CTVM17), previously amplified and sequenced by using primers for Rickettsia 16S rRNA, ompB, and sca4 genes revealing >98% similarity with R. africae (8), was used as a positive control. Negative controls consisted of DNA from 2 male and female laboratory-reared Rhipicephalus appendiculatus ticks and distilled water. DNA of positive samples was recovered, and confirmation of amplicon authenticity was obtained through sequence analysis by using nucleotide BLAST (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

A total of 39 ticks were collected in Uganda (32 adult males, 5 females, and 2 nymphs), and 141 were collected in Nigeria (80 males, 59 females, and 2 nymphs); all were identified as A. variegatum (Technical Appendix Table). SFG rickettsiae DNA was amplified in 26 (67%) of 39 ticks from Uganda and 88 (62%) of 141 ticks from Nigeria by using the ompA gene primers; amplicons of the gltA genes were obtained in 16 (41%) of 39 ticks and 84 (60%) of 141 ticks, respectively (Technical Appendix Table). Overall, 81 (45%) of 180 ticks were positive by gltA and ompA PCRs (Technical Appendix Table). DNA sequences of the 22 gltA and ompA products from Uganda and the 22 from Nigeria showed 100% similarity with published sequences of R. africae (GenBank accession nos. U59733 and RAU43790, respectively). For both countries, ticks positive for Rickettsia spp. and SFG rickettsiae DNA were male and female specimens (Technical Appendix Table). Among females, both unengorged and engorged specimens contained DNA from rickettsiae and SFG rickettsiae (Technical Appendix Table).

These findings represent a novelty for Uganda. With reference to Nigeria, our results contrast with the prevalence of 8% recorded in a similarly sized sample (n = 153) of A. variegatum ticks collected from cattle in the same part of the country (3); this discrepancy might be the result of previous targeting of the rickettsial 16S rDNA gene. In the study reported here, the SFG-specific ompA PCR proved to be more sensitive than gltA for detecting rickettsiae DNA, as has also been reported in previous work (9). Although finding R. africae DNA in engorged female and nymphal tick specimens might be attributable to prolonged rickettsemia in cattle (10), the presence of R. africae in distinctly unengorged female ticks indicates the potential for A. variegatum ticks to act as a reservoir of this SFG rickettsia (2).

This study extends the known geographic range of R. africae in A. variegatum ticks in sub-Saharan Africa. The number of potentially infective ticks recorded in Uganda and Nigeria suggests that persons in rural areas of northern Uganda and central Nigeria might be at risk for African tick-bite fever. Awareness of this rickettsiosis should be raised, particularly among persons who handle cattle (e.g., herders and paraveterinary and veterinary personnel). Physicians in these areas, as well as those who care for returning travelers, should consider African tick-bite fever in their differential diagnosis for patients with malaria and influenza-like illnesses.

Results of PCR screening of Amblyomma variegatum ticks.

Acknowledgments

We thank Abraham Goni Dogo for helping with tick collections in Nigeria, Lesley Bell-Sakyi and Pilar Alberdi for providing positive controls, Tim Connelley for providing laboratory-reared ticks to be used as negative controls, Cristina Socolovschi for her valuable suggestions on the molecular proceedings, and Albert Mugenyi for his indispensable assistance with map design.

The research leading to these results received funding from the UK Department for International Development under the umbrella of the Stamp Out Sleeping Sickness Programme, the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council under the Combating Infectious Diseases in Livestock for International Development scheme, and the European Union's Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 221948, Integrated Control of Neglected Zoonoses.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Lorusso V, Gruszka KA, Majekodunmi A, Igweh A, Welburn S, Picozzi K. Rickettsia africae in Amblyomma variegatum ticks, Uganda and Nigeria [letter]. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2013 Oct [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1910.130389

References

- 1.Parola P, Paddock CD, Raoult D. Tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: emerging diseases challenging old concepts. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:719–56. 10.1128/CMR.18.4.719-756.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Socolovschi C, Huynh TP, Davoust B, Gomez J, Raoult D, Parola P. Transovarial and trans-stadial transmission of Rickettsiae africae in Amblyomma variegatum ticks. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15(Suppl. 2):317–8. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02278.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogo NI, de Mera IG, Galindo RC, Okubanjo OO, Inuwa HM, Agbede RI, et al. Molecular identification of tick-borne pathogens in Nigerian ticks. Vet Parasitol. 2012;187:572–7. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reye AL, Arinola OG, Hübschen JM, Muller CP. Pathogen prevalence in ticks collected from the vegetation and livestock in Nigeria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:2562–8. 10.1128/AEM.06686-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker AR, Bouattour A, Camicas JL, Estrada-Peña A, Horak IG, Latif A. el al. Ticks of domestic animals in Africa. A guide to identification of species. Edinburgh (UK). Bioscience Reports; 2003.

- 6.Regnery RL, Spruill CL, Plikaytis BD. Genotypic identification of rickettsiae and estimation of intraspecies sequence divergence for portions of two rickettsial genes. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1576–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fournier PE, Roux V, Raoult D. Phylogenetic analysis of spotted fever group rickettsiae by study of the outer surface protein rOmpA. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:839–49. 10.1099/00207713-48-3-839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alberdi MP, Dalby MJ, Rodriguez-Andres J, Fazakerley JK, Kohl A, Bell-Sakyi L. Detection and identification of putative bacterial endosymbionts and endogenous viruses in tick cell lines. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2012;3:137–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Robinson JB, Eremeeva ME, Olson PE, Thornton SA, Medina MJ, Sumner JW, et al. New approaches to detection and identification of Rickettsia africae and Ehrlichia ruminantium in Amblyomma variegatum (Acari: Ixodidae) ticks from the Caribbean. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:942–51. 10.1603/033.046.0429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly PJ, Mason PR, Manning T, Slater S. Role of cattle in the epidemiology of tick-bite fever in Zimbabwe. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:256–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Results of PCR screening of Amblyomma variegatum ticks.