Abstract

Laboratory-confirmed cases of subclinical infection with avian influenza A(H5N1) virus in humans are rare, and the true number of these cases is unknown. We describe the identification of a laboratory-confirmed subclinical case in a woman during an influenza A(H5N1) contact investigation in northern Vietnam.

Keywords: avian influenza A(H5N1), influenza, avian influenza, H5N1, Vietnam, human, subclinical, viruses, asymptomatic, clades, poultry

In 2012, a debate was published in Science about the number of humans who have experienced subclinical infection with avian influenza A H5 and how this unknown denominator could affect the case-fatality rate reported by the World Health Organization (1,2). The controversy rests, to a large extent, on interpretation of serologic tests used to detect prior H5 infection and the paucity of virologically confirmed subclinical or mild cases. Here we describe a case of subclinical avian influenza A H5 infection, confirmed both virologically and serologically.

The Case

The subclinical case was detected in 2011 during a contact investigation of a 40-year-old man suspected of having influenza A(H5N1) virus infection. The man’s household had sick poultry that were consumed by household members. The chickens roamed close to the sleeping area of the household members. The index case-patient, his daughter, and his daughter-in-law were involved in slaughtering and preparing the chickens. The index case-patient had fever, cough, dyspnea, and diarrhea that progressed over 2 days, leading to hospital admission. Despite intensive care and treatment with oseltamivir and antibiotics, the disease progressed, and he died 2 days later.

A throat swab taken from the index case-patient on day 3 of illness was tested by reverse transcription PCR, and results were positive for influenza A(H5N1) virus. Hemagglutination inhibition (HI) and microneutralization (MN) tests for H5N1-specific antibodies were negative in samples taken during the acute phase of illness (Technical Appendix).

On day 5 of illness of the index case-patient, a contact investigation was initiated. Throat swab specimens were collected from 4 household members and 1 close contact of the index case-patient: his spouse (age 47 years), daughter (age 18 years), daughter-in-law (age 25 years), and grandson (age 1 year) and an unrelated man (age 43 years). None of the contacts had signs or symptoms. Infection control measures were initiated, and all household members were given oseltamivir (75 mg/d) for 1 week and instructed to seek immediate health care if fever or respiratory symptoms developed. Results of HI testing of serum samples collected during the acute illness phase of the index case-patient were negative.

The human throat swab samples were tested by conventional RT-PCR. The sample from the index case-patient’s daughter, collected 6 days after the woman had slaughtered a chicken, was positive for influenza A/H5 by real-time RT-PCR, and virus was recovered on day 10 of inoculation on MDCK cells (Technical Appendix). The virus was identified by sequencing as influenza A/H5, clade 2.3.2.1. The woman had no signs or symptoms at the time the throat swab was collected, nor did she report any symptoms to health authorities during the subsequent week. Chickens were also tested, and 4 chickens in the commune tested positive for influenza A(H5N1) virus by RT-PCR of throat and cloacal swab specimens.

Repeat throat swab specimens collected from the 4 household contacts 6 days after the initial collection yielded negative test results for influenza/H5. Serologic testing showed seroconversion only in the woman with subclinical infection; her HI titer increased from <20 to 160 against both clade 2.3.4 and 2.3.2.1 viruses (Table 1). During a second contact investigation 1 month later, 20 other members of the commune were screened by RT-PCR of throat swab specimens and serologic testing. All results were negative for influenza A(H5N1) virus.

Table 1. HHI and MN assay titers for serum samples from woman with subclinical influenza A(H5N1) virus infection, Vietnam, 2011.

| Clade and sample |

HHI |

MN |

| Clade 1 | ||

| First sample, day 5 | <20 | ND |

| Second sample, day 11 | 40 | <10 |

| Third sample, day 41 |

40 |

<10 |

| Clade 2.3.2.1 | ||

| First sample, day 5 | <20 | ND |

| Second sample, day 11 | 80 | 80 |

| Third sample, day 41 |

160 |

160 |

| Clade 2.3.4 | ||

| First sample, day 5 | <20 | ND |

| Second sample, day 11 | 80 | 40 |

| Third sample, day 41 | 160 | 40 |

*Sample days are days since disease onset in index case-patient. HHI, horse hemagglutination inhibition; MN microneutralization; ND, not done.

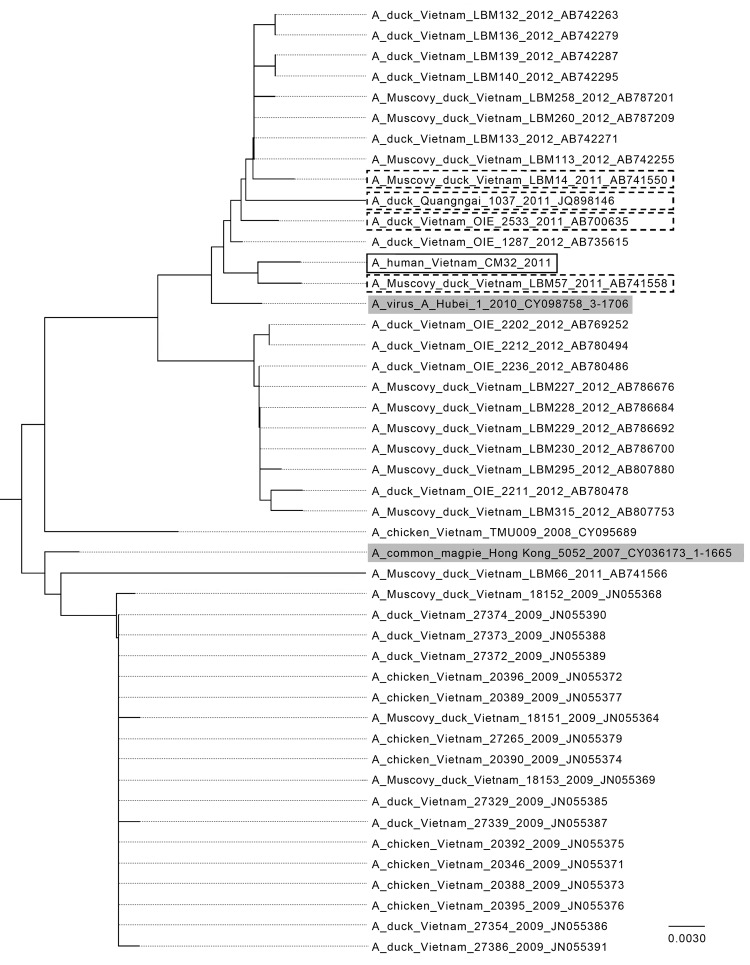

The full genome of the identified virus strain (A/CM32/2011) was sequenced (Technical Appendix) and confirmed to be clade 2.3.2.1 by using the Highly Pathogenic H5N1 Clade Classification Tool (3). The open reading frames of the genes were translated and aligned with all clade 2.3.2.1 sequences available from the Influenza Research Database (www.fludb.org). Amino acid changes are summarized in Table 2. A phylogenetic analysis of clade 2.3.2.1 from Vietnam sequences showed a high homology between the samples, including A/CM32/2011 (Figure). To identify possible changes specific to human infection, the differences between the clade consensus and A/CM32/2011 were compared with influenza A(H5N1) virus samples from Asia. No amino acid changes were preferentially seen in human samples compared with the avian samples. A/CM32/2011 contains the N170D (4) and T172A mutations in HA that are associated with airborne transmissibility of influenza A(H5N1) virus in ferrets (5); these mutations are found in most avian influenza A(H5N1) clade 2.3.2.1 samples (Table 2, Appendix). The results indicate that the virus is a typical influenza A(H5N1) clade 2.3.2.1 virus, with no remarkable changes.

Table 2. Amino acid changes detected in first passage of full-genome sequence analysis of influenza A(H5N1) virus isolate from subclinical human infection, Vietnam.

| Gene and mutation |

Mutation frequency, % |

| Polybasic 2, n = 112 | |

| S107N | 15 |

| I261T | 2 |

| K312R | 15 |

| Nucleoprotein, n = 125 | |

| I33V | 48 |

| H52Y | 50 |

| R77K | 45 |

| T395N | 49 |

| Polymerase, n = 51 | |

| A20T | 12 |

| D27S | 12 |

| V63A | 29 |

| T85T | 33 |

| K142R | 12 |

| Y241C | 45 |

| Q259P | 33 |

| L261M | 29 |

| A263T | 43 |

| D272E | 12 |

| V323I | 2 |

| E352D | 12 |

| R353K | 29 |

| R391K | 29 |

| S400P | 35 |

| A404S | 29 |

| D547N | 2 |

| A552T | 37 |

| N614T | 29 |

| G631S | 29 |

| S648C | 2 |

| L711I | 2 |

| Polybasic 1, n = 129 | |

| K54E | 22 |

| S158N | 49 |

| T182I | 2 |

| N314S | 2 |

| D383E | 30 |

| L384I | 7 |

| I525V | 9 |

| S633N | 2 |

| K635R | 19 |

| Hemagglutinin, n = 244 | |

| T9A | 49 |

| L82M | 36 |

| S139T | 6 |

| S152P | 36 |

| D199N | 2 |

| F455Y | 1 |

| K461R | 8 |

| Neuraminidase, n = 177 | |

| I8V | 16 |

| V13I | 27 |

| I16V | 21 |

| A46T | 14 |

| T64A | 1 |

| A66S | 1 |

| H106N | 1 |

| M107L | 23 |

| V143I | 10 |

| T168I | 2 |

| G200R | 49 |

| A212T | 1 |

| S265A | 36 |

| T312E | 1 |

| M318V | 26 |

| I326V | 21 |

| N346H | 13 |

| V369M | 19 |

| Nonstructural 1, n = 145 | |

| S73P | 11 |

| D87E | 6 |

| M118I | 28 |

| V123I | 28 |

| E148K | 1 |

| S166G | 25 |

| M217L | 1 |

| T220A | 6 |

Figure.

Phylogentic analysis of avian influenza A(H5N1) virus clade 2.3.2.1 hemagglutinin DNA sequences from Vietnam compared with other isolates. Solid black box indicates isolate from the subclinical human case investigated in this study, A/CM32/2011; dashed boxes indicate sequences from Vietnam in 2011; gray shading indicates World Health Organization vaccine candidates A/common magpie/Hong Kong/5052/2007 and A/Hubei/1/2010 for clade 2.3.2.1. The sequences were downloaded from the Influenza Research Database (www.fludb.org), imported into MEGA 5.2 (www.megasoftware.net), and aligned by using MUSCLE (EMBL-EBI, Cambridgeshire, UK). The neighbor-joining tree was generated from the aligned sequences using standard settings. Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site.

Conclusions

We report subclinical infection with avian influenza A(H5N1) virus in a human in Vietnam, confirmed by RT-PCR, virus isolation from throat swab, and detection of specific antibodies. A subclinical case was also reported from Pakistan in 2008 (6). Sequence analysis of the Vietnam case showed that the infecting virus belonged to influenza A(H5N1) clade 2.3.2.1. This clade was first detected in poultry in northern Vietnam in early 2010 and replaced clade 2.3.4 in that area, whereas clade 1 remains predominant in southern Vietnam, with 4 confirmed cases reported in early 2012 (7). The recent clade 2.3.2.1 has evolved from clade 2.3.2 viruses that has circulated among poultry in eastern Asia since 2005 and has become predominant in several Asian countries. Since clade 2.3.2.1 viruses were initially detected in Vietnam, prevalence has increased in poultry, but no associated rise in detection of human cases has been observed (7). Similarly, clade 2.3.2.1 virus has been circulating in poultry in India, but no human cases have been reported (8). The HA sequence of this virus is similar to an influenza A(H5N1) virus detected by RT-PCR in a 3-year-old patient with influenza-like illness investigated as part of the National Influenza System Surveillance in 2010 (M.Q. Le, unpub. data). This patient had mild symptoms and survived, which raises the possibility that this strain represents a less virulent form of influenza A(H5N1) in humans.

In our investigation, the case-patient with subclinical infection was treated with oseltamivir while she was asymptomatic, which may explain why she did not develop clinical disease. Studies using human volunteers indicate that seasonal influenza virus shedding may occur ≈24 hours before symptom onset in 25%–30% of patients (9). Likewise, community cohort studies show presymptomatic shedding and asymptomatic shedding in 15%–20% of patients infected with seasonal influenza viruses and with influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus (10–12). Oseltamivir is known to prevent disease when given before inoculation in human volunteers and to shorten duration and lessen the severity of illness in natural infection (13), but we found no evidence in clinical and volunteer studies from the literature suggesting that oseltamivir may prevent clinical illness once detectable infection has been established, as we found in this subclinical case (13,14). The patient we investigated probably was exposed during slaughtering of a chicken 6 days before her positive throat swab was collected. However, because chickens in the commune tested positive at the time of the contact investigation, ongoing exposure to influenza A(H5N1) cannot be excluded as the source of infection. Furthermore, the patient may not have reported symptoms to the health authorities for personal reasons.

Thus far, evidence of subclinical influenza A(H5N1) virus infections has been collected on the basis of serologic testing only (1), but it is unclear whether serologic testing reliably detects subclinical cases. According to the World Health Organization, MN titers >80 are indicative of infection but must be confirmed by a second serologic test because of the possibility of cross-reactivity (1). The interpretation of results from a single serum sample is limited by the specificity or sensitivity of serologic tests, and viral shedding times may mean that infected cases may be missed. Estimating the incidence of asymptomatic influenza A(H5N1) virus infection in humans exposed to sick poultry or human case-patients requires further careful study using early collection of swab samples and paired acute and convalescent serum samples.

Detailed methods of isolation and sequencing for influenza A(H5N1) virus from subclinical human case, Vietnam.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology, the Preventive Medical Centre Bac Kan, and the Academic Medical Center for their support.

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust (UK), the South East Asian Infectious Disease Clinical Research Network (SEAICRN, Vietnam), and the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme under the project “European Management Platform for Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious disease Entities” (EMPERIE).

Biography

Dr Mai Quynh Le is a virologist and the head of the National Influenza Center of Vietnam at the National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology in Hanoi. Her research interests are the evolution and co-evolution of animal and human influenza viruses and zoonotic infectious diseases.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Le MQ, Horby P, Fox A, Nguyen HT, Nguyen HKL, Hoang PMV, et al. Subclinical avian influenza A(H5N1) virus infection in human, Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2013 Oct [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1910.130730

References

- 1.Wang TT, Parides MK, Palese P. Seroevidence for H5N1 influenza infections in humans: meta-analysis. Science. 2012;335:1463. 10.1126/science.1218888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Kerkhove MD, Riley S, Lipsitch M, Guan Y, Monto AS, Webster RG, et al. Comment on “Seroevidence for H5N1 influenza infections in humans: meta-analysis.”. Science. 2012;336:1506–, author reply 1506.. 10.1126/science.1221434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Squires RB, Noronha J, Hunt V, Garcia-Sastre A, Macken C, Baumgarth N, et al. Influenza Research Database: an integrated bioinformatics resource for influenza research and surveillance. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2012;6:404–16. 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00331.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herfst S, Schrauwen EJ, Linster M, Chutinimitkul S, de Wit E, Munster VJ, et al. Airborne transmission of influenza A/H5N1 virus between ferrets. Science. 2012;336:1534–41. 10.1126/science.1213362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imai M, Watanabe T, Hatta M, Das SC, Ozawa M, Shinya K, et al. Experimental adaptation of an influenza H5 HA confers respiratory droplet transmission to a reassortant H5 HA/H1N1 virus in ferrets. Nature. 2012;486:420–8 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Human cases of avian influenza A (H5N1) in North-West Frontier Province, Pakistan, October-November 2007. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2008;83:359–64 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen T, Rivailler P, Davis CT, Thi Hoa D, Balish A, Hoang Dang N, et al. Evolution of highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) virus populations in Vietnam between 2007 and 2010. Virology. 2012;432:405–16. 10.1016/j.virol.2012.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagarajan S, Tosh C, Smith DK, Peiris JS, Murugkar HV, Sridevi R, et al. Avian influenza (H5N1) virus of clade 2.3.2 in domestic poultry in India. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31844. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carrat F, Vergu E, Ferguson NM, Lemaitre M, Cauchemez S, Leach S, et al. Time lines of infection and disease in human influenza: a review of volunteer challenge studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:775–85. 10.1093/aje/kwm375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suess T, Remschmidt C, Schink SB, Schweiger B, Heider A, Milde J, et al. Comparison of shedding characteristics of seasonal influenza virus (sub)types and influenza A(H1N1)pdm09; Germany, 2007–2011. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e51653. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu Y, Komiya N, Kamiya H, Yasui Y, Taniguchi K, Okabe N. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 transmission during presymptomatic phase, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1737–9. 10.3201/eid1709.101411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patrozou E, Mermel LA. Does influenza transmission occur from asymptomatic infection or prior to symptom onset? Public Health Rep. 2009;124:193–6 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayden FG, Treanor JJ, Fritz RS, Lobo M, Betts RF, Miller M, et al. Use of the oral neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir in experimental human influenza: randomized controlled trials for prevention and treatment. JAMA. 1999;282:1240–6. 10.1001/jama.282.13.1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayden FG, Jennings L, Robson R, Schiff G, Jackson H, Rana B, et al. Oral oseltamivir in human experimental influenza B infection. Antivir Ther. 2000;5:205–13 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detailed methods of isolation and sequencing for influenza A(H5N1) virus from subclinical human case, Vietnam.