Abstract

We have investigated the previously published ‘metabolon hypothesis’ postulating that a close association of the anion exchanger 1 (AE1) and cytosolic carbonic anhydrase II (CAII) exists that greatly increases the transport activity of AE1. We study whether there is a physical association of and direct functional interaction between CAII and AE1 in the native human red cell and in tsA201 cells coexpressing heterologous fluorescent fusion proteins CAII-CyPet and YPet-AE1. In these doubly transfected tsA201 cells, YPet-AE1 is clearly associated with the cell membrane, whereas CAII-CyPet is homogeneously distributed throughout the cell in a cytoplasmic pattern. Förster resonance energy transfer measurements fail to detect close proximity of YPet-AE1 and CAII-CyPet. The absence of an association of AE1 and CAII is supported by immunoprecipitation experiments using Flag-antibody against Flag-tagged AE1 expressed in tsA201 cells, which does not co-precipitate native CAII but co-precipitates coexpressed ankyrin. Both the CAII and the AE1 fusion proteins are fully functional in tsA201 cells as judged by CA activity and by cellular HCO3− permeability ( ) sensitive to inhibition by 4,4′-Diisothiocyano-2,2′-stilbenedisulfonic acid. Expression of the non-catalytic CAII mutant V143Y leads to a drastic reduction of endogenous CAII and to a corresponding reduction of total intracellular CA activity. Overexpression of an N-terminally truncated CAII lacking the proposed site of interaction with the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail of AE1 substantially increases intracellular CA activity, as does overexpression of wild-type CAII. These variously co-transfected tsA201 cells exhibit a positive correlation between cellular

) sensitive to inhibition by 4,4′-Diisothiocyano-2,2′-stilbenedisulfonic acid. Expression of the non-catalytic CAII mutant V143Y leads to a drastic reduction of endogenous CAII and to a corresponding reduction of total intracellular CA activity. Overexpression of an N-terminally truncated CAII lacking the proposed site of interaction with the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail of AE1 substantially increases intracellular CA activity, as does overexpression of wild-type CAII. These variously co-transfected tsA201 cells exhibit a positive correlation between cellular  and intracellular CA activity. The relationship reflects that expected from changes in cytoplasmic CA activity improving substrate supply to or removal from AE1, without requirement for a CAII–AE1 metabolon involving physical interaction. A functional contribution of the hypothesized CAII–AE1 metabolon to erythroid AE1-mediated HCO3− transport was further tested in normal red cells and red cells from CAII-deficient patients that retain substantial CA activity associated with the erythroid CAI protein lacking the proposed AE1-binding sequence. Erythroid

and intracellular CA activity. The relationship reflects that expected from changes in cytoplasmic CA activity improving substrate supply to or removal from AE1, without requirement for a CAII–AE1 metabolon involving physical interaction. A functional contribution of the hypothesized CAII–AE1 metabolon to erythroid AE1-mediated HCO3− transport was further tested in normal red cells and red cells from CAII-deficient patients that retain substantial CA activity associated with the erythroid CAI protein lacking the proposed AE1-binding sequence. Erythroid  was indistinguishable in these two cell types, providing no support for the proposed functional importance of the physical interaction of CAII and AE1. A theoretical model predicts that homogeneous cytoplasmic distribution of CAII is more favourable for cellular transport of HCO3− and CO2 than is association of CAII with the cytoplasmic surface of the plasma membrane. This is due to the fact that the relatively slow intracellular transport of H+ makes it most efficient to place the CA in the vicinity of the haemoglobin molecules, which are homogeneously distributed over the cytoplasm.

was indistinguishable in these two cell types, providing no support for the proposed functional importance of the physical interaction of CAII and AE1. A theoretical model predicts that homogeneous cytoplasmic distribution of CAII is more favourable for cellular transport of HCO3− and CO2 than is association of CAII with the cytoplasmic surface of the plasma membrane. This is due to the fact that the relatively slow intracellular transport of H+ makes it most efficient to place the CA in the vicinity of the haemoglobin molecules, which are homogeneously distributed over the cytoplasm.

Key points

Controversial results have been reported on the hypothesis that the cytosolic carbonic anhydrase II (CAII) of the red cell is largely bound to the cell's Cl−/HCO3− exchanger AE1, forming a ‘metabolon complex’ that greatly enhances transport activity of AE1.

In examining so far untested aspects of this hypothesis, we report that fluorophore-labelled AE1 and CAII proteins, expressed in tsA201 cells, neither colocalize at the cell membrane nor show close proximity by Förster resonance emission spectroscopy.

Antibody against Flag-tagged AE1 expressed in tsA201 cells co-immunoprecipitates coexpressed ankyrin but not CAII.

CAII-deficient human red blood cells with substantial CAI activity exhibit HCO3− permeabilities identical to those of normal red cells.

A mathematical model of CO2/HCO3− transport of red cells indicates that this process occurs more rapidly when the CA of the cell is distributed homogeneously across the cytoplasm rather than being bound to the membrane interior.

Introduction

The erythroid Cl−/HCO3− exchanger 1 (AE1/SLC4A1) is responsible for the so-called Hamburger shift, which exchanges Cl− for HCO3− across the red cell membrane during the blood's CO2 uptake in the tissue and CO2 release in the lung. This mechanism results in a major augmentation of the CO2 binding capacity of the blood by mediating transfer into the plasma of a major part of the HCO3− that is formed from CO2 inside red blood cells (RBCs) by the action of intracellular carbonic anhydrase (CA).

The present study addresses the question of whether carbonic anhydrase II (CAII) in the human red cell is largely bound to the internal side of the plasma membrane, specifically to the short cytoplasmic C-terminal tail of AE1 (see Fig. S1, Supplemental Data). The study additionally examines the hypothesis, originally proposed by Vince and Reithmeier (1998), that CAII binding to AE1 activates the latter such that the two proteins form a ‘metabolon’ mediating enhanced HCO3− transport across the red cell membrane.

It was postulated long ago that substantial CAII is bound to the interior of the red cell membrane (Enns, 1967). Subsequent investigations with red cell ghosts repeatedly washed before resealing led three groups to conclude that various wash procedures removed CAII almost completely from the red cell membrane (Rosenberg & Guidotti, 1968; Tappan, 1968; Randall & Maren, 1972). These latter studies together suggested the absence of a high affinity association between CAII and the cytoplasmic surface of the red cell membrane.

However, Parkes and Coleman (1989) later observed that addition of human red cell ghost fragments increased human CAII activity by 3.5-fold. Kifor et al. (1993) reported that addition of DIDS (4,4′-Diisothiocyano-2,2′-stilbenedisulfonic acid; presumed to bind mainly to AE1) altered the fluorescence of dansylsulfonamide bound to intra-erythrocyte CA, consistent with direct interaction between AE1 and CAII. Vince and Reithmeier (1998) then revived interest in the field with the following findings:

in (unwashed) red cell ghosts CAII immunofluorescence was predominantly detected close to the membrane inner surface (as also reported in confocal images of intact erythrocytes by Campanella et al. 2005). Tomato lectin application to red cell ghosts caused clustering of both AE1 and CAII, although colocalization of AE1 and CAII in these clusters was not demonstrated;

CAII and AE1 could be co-immunoprecipitated with antibody recognizing the N terminus of AE1 (but not with antibody recognizing the AE1 C terminus);

a solid phase binding assay revealed binding of detergent-solubilized intact band 3 to immobilized CAII with Kd of 70 nm, and binding was inhibited by antibody against the AE1 C terminus;

another solid-phase binding assay showed an interaction of immobilized CAII with soluble phase AE1 C-terminal cytoplasmic tail (Ct) fused at its N-terminal end with glutathione-S-transferase (GST). This enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) later identified the CAII binding region within the AE1-Ct as the four residues 887DADD890 (Vince & Reithmeier, 2000). The authors pointed out that AE1 transporters of many other species show the same or very similar sequences, e.g. DGDD in mouse and rat and DADD in bovine RBCs (Fig. S1). The elements essential for binding were three, or at least two, negatively charged Asp residues within these four amino acids, always preceded by an aliphatic residue. The GST-AE1-Ct ELISA also revealed within the N-terminal 17 residues of CAII a binding site of six positively charged His or Lys residues, proposed to interact with the AE1 C-terminal cytoplasmic tail DADD motif described above (Vince et al. 2000; see Fig. S1). CAI, which lacks all of these six residues, did not bind to AE1. A corollary of these studies derives from (i) the presence in human red cells of ∼106 copies of AE1 and ∼106 copies of CAII (yielding an ∼20 μm CAII concentration if distributed throughout the cytosolic volume), and from (ii) the above mentioned 70 nm Kd for binding of AE1 and CAII. These values predict an intra-erythrocyte equilibrium concentration of unbound (free cytosolic) CAII of only 1.2 μm, implying that 94% of RBC CAII should be AE1-bound, and thus effectively membrane-bound. In contrast, Piermarini et al. (2007) in a reinvestigation reported no detectable in vitro binding interaction between a synthetic AE1-C-terminal peptide and CAII as assayed either by ELISA or by surface plasmon resonance.

While the results of Reithmeier and colleagues strongly suggest significant binding of CAII to AE1, formation by the two interacting proteins of a ‘metabolon’ (i.e. with enhancement of the transport function of AE1) remained an open question. Such enhancement could occur through an allosteric effect of CAII binding on AE1, potentially independent of CAII enzymatic activity, or through the close proximity of CA catalytic activity to the intracellular substrate transport site of AE1, effectively allowing instantaneous conversion of HCO3− to CO2 after anion translocation, and thus maintaining an optimal transmembrane HCO3− gradient. The latter mechanism could require either simple proximity of the AE1 transport site and CAII catalytic activity, or it could imply a more specific interaction between the AE1 transport site and the catalytic centre of CAII to facilitate HCO3− translocation across the permeability barrier within the AE1 polypeptide.

A first test of functional interaction between CAII and AE1 activity was reported by Sterling et al. (2001a,b), who overexpressed AE1 in HEK293 cells containing endogenous CAII. They found that: (i) the CA inhibitor acetazolamide reduced the stimulation of Cl−/HCO3− exchange by extracellular Cl− removal and restoration, respectively, by 50%, thus showing that CAII activity accelerates AE1 activity; (ii) AE1 with mutated DADD (the proposed CAII binding site in the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail) exhibited 90% reduction of transport activity in HEK293 cells, which they attributed to reduced AE1 binding of CAII (however, transport activities of these mutants were not tested in the absence of CAII); and (iii) in HEK293 cells cotransfected with cDNA encoding the catalytically inactive CAII-V143Y mutant resulted in a 60% reduction of AE1 transport rates, interpreted as reflecting displacement of endogenous CAII of HEK293 cells from its AE1 binding site by the inactive heterologous mutant CAII. The implication of this interpretation is that CAII binding to AE1 is required to enhance AE1 transport activity.

The present study reinvestigates the AE1–CAII metabolon hypothesis by probing the following questions that have not been examined to date:

Is fluorophore-labelled CAII in intact cells expressing heterologous AE1 indeed concentrated predominantly at the internal side of the plasma membrane, as postulated for RBCs? We investigate this by expressing yellow fluorescent protein-labelled AE1 in tsA201 cells (SV40-transformed HEK293 cells) and studying the distribution of coexpressed cyan fluorescent protein-labelled CAII using confocal microscopy.

Is CAII directly bound to AE1? We probe this by studying Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) between the two coexpressed fusion proteins.

Can association between native CAII and AE1 be demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation of the two proteins when expressed in tsA201 cells?

What is the effect of coexpressing the catalytically inactive CAII mutant V143Y on HCO3− transport by intact AE1-expressing tsA201 cells? How can the results be interpreted, when total intracellular CA activity is taken into account?

What is the effect of expressing a truncated CAII whose N-terminal amino acids 1–24 have been deleted (Fig. S1), thereby removing all proposed AE1 binding residues of CAII and thus preventing the proposed AE1 binding to the CAII N terminus?

Is concentration of CA activity at the inner face of the plasma membrane indeed better for maximizing Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity than a homogeneous cytoplasmic distribution of CA activity? We address this problem by applying a mathematical model simulating membrane transport in conjunction with intracellular diffusion and reaction processes of CO2, HCO3− and H+.

Does AE1-mediated HCO3− transport in CAII-deficient human red cells differ from that in normal human red cells? This is an interesting model in which to test the metabolon hypothesis, because CAII-deficient RBCs still express substantial CA activity due to CAI which, however, does not bind to AE1.

Methods

Blood samples

Human red cells were taken from several members of our laboratory and used for mass spectrometric experiments on the same and the following day. Repeating the measurement 4 days after taking the blood made no difference in terms of mass spectrometric records. Two different CAII-deficient blood samples were taken from a member of a US family (CAII deficiency due to a 145–148 GTTT del mutation in exon 2; Shah et al. 2004) and from an Arabian patient (CAII deficiency due to a point mutation (G→A transition) at the exon 2–intron 2 junction; Hu et al. 1992). All red cells were washed three times in physiological saline before being used in the mass spectrometric experiments and were controlled for haemolysis. Haematocrit and blood cell count were taken to determine mean corpuscular volumes. Informed consent was sought and given in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. CAII-deficient blood samples were shipped chilled and red cells were used within 2–4 days after the samples were taken.

Cell culture

The tsA201 cell line was obtained from the European Collection of Cell Cultures. The cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2. For confocal laser scanning microscopy the cells were seeded on 35 mm (9.6 cm2) glass bottom dishes (MatTek Corp., Ashland, MA 01721, USA) with 2 ml culture medium and ∼8 × 104 cells per ml culture medium. For mass spectrometric measurements the cells were seeded on 100 mm (78.5 cm2) plastic dishes with 10 ml culture medium and ∼4.3 × 104 cells per ml culture medium. For Western blot analysis, cells were seeded in an 80 cm2 cell culture flask with 20 ml culture medium and 4.3 × 104 cells per ml medium.

Transfection with fusion proteins

Cells were transfected according to the manufacturer's protocol with GeneJuice (Novagen, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). YPet-mAE1, YPet-hAE1, CAII-CyPet, CAII-V143Y-CyPet or truncated CAII-CyPet (truncation of the N terminus of CAII, see Fig. S1) were transfected or co-transfected in different combinations of mAE1 and CAII. For transfections, 6 μg of each plasmid was applied per dish. For confocal laser scanning microscopy, transfection was done 24 h after seeding, and for mass spectrometric measurements 48 h after seeding. Transfection efficiency was 30–40%.

Construction of CyPet- and YPet-tagged AE1 and CAII

The yellow and cyan fluorescent tags used in this study are fluorescent protein variants optimized for FRET and encoded by the vectors pECyPet-N1 and pEYPet-C1, kindly provided by Dr Patrick S. Daugherty, University of California, Santa Barbara (Nguyen & Daugherty, 2005). For AE1 tagged N-terminally with YPet, an XhoI-SalI PCR product of the human AE1 and XhoI-EcoRI PCR product of murine AE1 were generated using Taq DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). The recognition sequences of the restriction endonucleases were added up- and downstream of the AE1 cDNA sequence using PCR primers. The resulting products were gel-purified and ligated 3′ into the pEYPet-C1 vector cut with suitable endonucleases.

For C-terminal tagging of the CAII constructs with CyPet, a BglII-SalI PCR product of human CAII was generated as described above. The stop codon was replaced with the amino acid tryptophan. The PCR product was ligated into vector pECyPet-N1.

The truncated CAII was produced by PCR-mediated deletion of codons 1–24, encoding the reported binding site for the AE1 C-terminal sequence DADD (Vince et al. 2000). The PCR product was ligated into the host vector as described above.

The CAII-V143Y cDNA (encoding a mutant polypeptide with enzymatic activity 3000-fold lower than that of wild-type CAII; Fierke et al. 1991) kindly provided by Dr Joe Casey, University of Alberta, was ligated into pECyPet-N1 as described above. To obtain an AE1 construct labelled at both the N and the C terminus, the XhoI-EcoRI PCR product encoding the murine AE1 with the stop codon replaced by glycine was subcloned into a CyPet-YPet tandem protein expression vector, upon opening of the latter between the CyPet and YPet sequence via an XhoI/EcoRI double digest. This procedure produced CyPet-AE1-YPet, which we used as a membrane-associated, positive FRET control.

Confocal microscopy and FRET measurements

Twenty-four (or occasionally 48) hours post-transfection, the culture dishes were mounted onto the stage of an inverse FV1000 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Olympus Deutschland, Hamburg, Germany), and cells were observed under oil immersion using a 60× objective. CyPet and YPet were excited using a 440 nm blue diode and the 514 nm argon line, respectively, directed to the cells via a 458/514 nm dual dichroic mirror. CyPet and YPet emission intensities were photometrically detected using Olympus filters BA465-495 and BA535-565, respectively. When simultaneous excitation of both CyPet and Ypet was desired (as in Fig. 5A, see below) the excitation wavelength was 458 nm.

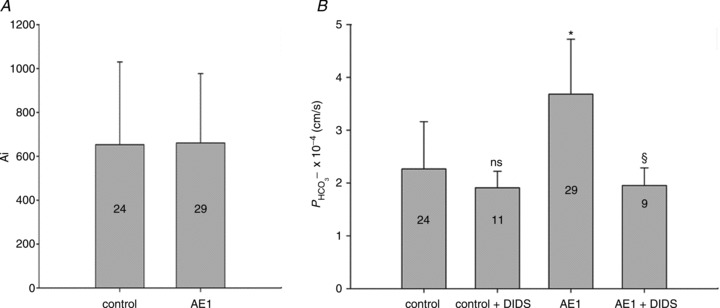

Figure 5. Carbonic anhydrase activity and HCO3− permeability in native and YPet-mAE1-expressing tsA201 cells.

A, intracellular CA activities measured in lysates of untreated tsA201 cells (control) and tsA201 cells transfected with YPet-mAE1 (AE1), using the mass spectrometric 18O technique. B, cellular  measured in untreated tsA201 cells (control) and in tsA201 cells expressing YPet-mAE1 (AE1), in the absence or presence of DIDS (10−5

m), a strong inhibitor of AE1 transport function. DIDS showed no effect on

measured in untreated tsA201 cells (control) and in tsA201 cells expressing YPet-mAE1 (AE1), in the absence or presence of DIDS (10−5

m), a strong inhibitor of AE1 transport function. DIDS showed no effect on  of control cells, but inhibited the AE1-associated increase in

of control cells, but inhibited the AE1-associated increase in  . ns, P > 0.05, *P < 0.02, §P < 0.02. Number of measurements are inside the columns. Error bars represent SD values.

. ns, P > 0.05, *P < 0.02, §P < 0.02. Number of measurements are inside the columns. Error bars represent SD values.

The experimental procedure to check for FRET was as described by Papadopoulos et al. (2004), who demonstrated the close proximity of regions of two proteins from determinations of FRET with dyes similar to those applied here. In brief, the intensity of CAII-CyPet emission (ICy) during excitation with the 440 nm line was measured photometrically before (ICy,Pre) and after (ICy,Post) complete bleaching of the potential FRET acceptor YPet-mAE1. Bleaching was conducted using the full laser power (100% setting) of the 514 nm argon line, a wavelength close to the excitation maximum of YPet, but with no excitation of CyPet. The entire cell was subjected to bleaching, but ICy,Post and ICy,Pre were determined exclusively for regions populated with the potential energy acceptor YPet-mAE1, i.e. at the cell membrane. In analysing an acceptor bleaching experiment, the finding of ICy,Post > ICy,Pre would indicate pre-bleach energy transfer from CAII-CyPet to YPet-mAE1. Since the latter phenomenon is measurable only when the two fluorophores are separated by <8–10 nm, FRET in this case would confirm the close proximity of CAII and mAE1, compatible with direct, physical interaction.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

An expression vector for 3xFlag-tag attached to the N terminus of the human anion exchanger 1 (hAE1) was generated by cloning 3xFlag-tagged hAE1 cDNA, generated by PCR using forward (F), 5′-CTGTCAAAG CTTATGGACTACAAAGACCATGACGGTGATTATAAA GATCATGACATCGATTACAAGGATGACGATGACAAG CTAGTGGAGGAGCTGCAGGATGA-3′, and reverse (R), 5′-CTGTCACTCGAGTCACACAGGCATGGCCACTT-3′, primers, into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). A human ankyrin 1 (hANK1) expression vector was generated by cloning hANK1 cDNA (a gift from Dr V. Bennett), generated by PCR using F, 5′-ACGTGGTACC ATGCCCTATTCTGTGGGCTTCC-3′, and R, 5′-ACTGG AATTCTTAAACCTTATCGTCGTCATCC-3′, primers into pcDNA3.

tsA201 cells were transfected at 70–80% confluence in serum-free DMEM with 6 μg pcDNA3–3xFlag-hAE1 expression plasmid and 6 μg pcDNA-hANK1 expression plasmid or empty expression vector, and 3 μl μg−1 DNA of Gene Juice transfection reagent (Novagen) in 100 mm dishes. After 24 h, the transfection medium was changed to DMEM. After a further 24 h, cells were harvested and washed once with ice-cold PBS. After addition of 500 μl IP-lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mm EGTA, pH 7.0, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm glycerol phosphate, 50 mm sodium fluoride, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 5 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 1% Triton X-100, 0.27 m saccharose, 1 tablet cOmplete Mini, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany)/10 mL buffer), cells were scraped, vortexed, and after 20 min on ice, centrifuged for 20 min (13,000 r.c.f.) at 4°C. The supernatant (lysate) was stored at −80°C.

Anti-Flag M2 affinity gel suspension (30 μl; Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) was washed three times with 1 ml IP-buffer (centrifugation for 5 min at 3500 r.c.f., 4°C). The affinity gel was resuspended with 200 μl IP-lysis buffer and 500 μl cell lysate was added. After incubation overnight at 4°C in an overhead shaker, the affinity gel was centrifuged and washed five times with 1 ml IP-buffer. The supernatant of the first centrifugation was stored at −80°C for Western blot analysis.

For Western blot analysis, the affinity gel was incubated for 20 min at 37°C with 20 μl 2× SDS sample buffer, cooled on ice and centrifuged at 4°C. The supernatant (eluate) was run on a 10% SDS-PAGE and analysed using anti-ANK1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Heidelberg, Germany), anti-CAII (Acris Antibodies, Herford, Germany) and anti-Flag (Stratagene, Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) antibodies (CAII ∼ 29 kDa; hANK1 ∼ 200 kDA; 3xFlag-hAE1 ∼ 98 kDa).

Mass spectrometric determination of bicarbonate permeability and cellular CA activity

This method was described in detail previously (Endeward & Gros, 2005; Endeward et al. 2006). Suspensions of human red cells (final haematocrit 0.03%) or tsA201 cell (final cytocrit 0.3%) were used in the mass spectrometric chamber at constant pH of 7.40 and temperature of 37°C. Briefly, in the presence of a solution of 18O-labelled HCO3− the time course of the decay of C18O16O in the suspension was followed via the special mass spectrometric inlet system described earlier. From these time courses (e.g. as shown in Endeward et al. 2008; Endeward & Gros, 2009), the permeabilities of the cells for HCO3−,  , and CO2,

, and CO2,  , were obtained in two steps: (1) preliminary estimates of

, were obtained in two steps: (1) preliminary estimates of  and

and  were inserted into the set of differential equations describing the process of 18O exchange (as given by Endeward & Gros, 2005) and used to calculate a ‘theoretical’ curve of C18O16O decay; (2) this calculated curve was compared with the experimental decay curve, and parameters

were inserted into the set of differential equations describing the process of 18O exchange (as given by Endeward & Gros, 2005) and used to calculate a ‘theoretical’ curve of C18O16O decay; (2) this calculated curve was compared with the experimental decay curve, and parameters  and

and  were varied by a fitting procedure, again as described by Endeward and Gros (2005), until the pair of

were varied by a fitting procedure, again as described by Endeward and Gros (2005), until the pair of  and

and  values was obtained that best described the experimental curve. Usually, the fit produces a curve of C18O16O decay that is virtually indistinguishable from the experimental curve (Endeward & Gros, 2009). The sensitivity of the fitted values of

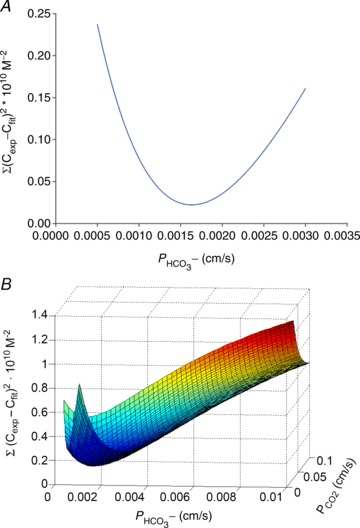

values was obtained that best described the experimental curve. Usually, the fit produces a curve of C18O16O decay that is virtually indistinguishable from the experimental curve (Endeward & Gros, 2009). The sensitivity of the fitted values of  to the parameters used in the differential equations has been described previously (Endeward et al. 2008). Figure 1A shows that, for a given

to the parameters used in the differential equations has been described previously (Endeward et al. 2008). Figure 1A shows that, for a given  , the minimum of the sum of squared deviations between the C18O16O concentrations of the experimental decay curves and those of the curves calculated from the fit defines

, the minimum of the sum of squared deviations between the C18O16O concentrations of the experimental decay curves and those of the curves calculated from the fit defines  very well. Figure 1B shows that the experimental data allow us equally well to derive the optimal combination of

very well. Figure 1B shows that the experimental data allow us equally well to derive the optimal combination of  and

and  values. In Fig. 1A and B there is one single minimum for the sum of squares and no local minima whatsoever.

values. In Fig. 1A and B there is one single minimum for the sum of squares and no local minima whatsoever.

Figure 1. Determination of  and

and  from the mass spectrometric records by minimizing the sum of squared deviations.

from the mass spectrometric records by minimizing the sum of squared deviations.

Illustration of the fitting procedure used to determine

Illustration of the fitting procedure used to determine  at a given

at a given  of 0.12 cm s−1 (A) or both

of 0.12 cm s−1 (A) or both  and

and  (B). The sum of squares of deviations between experimental concentrations of C18O16O and their counterparts from the calculated C18O16O decay curve as obtained with the fitted values of

(B). The sum of squares of deviations between experimental concentrations of C18O16O and their counterparts from the calculated C18O16O decay curve as obtained with the fitted values of  /

/ are plotted vs. the value of

are plotted vs. the value of  (A) or vs. both the values of

(A) or vs. both the values of  and

and  (B).

(B).

Evaluation of  from the time courses of C18O16O requires knowledge of the intracellular CA activity (Endeward & Gros, 2005). This was obtained by lysing cell suspensions of defined haematocrit or cytocrit, followed by centrifugation at 100,000 g (1 h), and determining the CA activity of the solutions by mass spectrometry. Conditions were 37°C and, approximating intracellular conditions, pH 7.20 with final Cl− concentrations of 60 mm for haemolysates and 10 mm for tsA cell lysates.

from the time courses of C18O16O requires knowledge of the intracellular CA activity (Endeward & Gros, 2005). This was obtained by lysing cell suspensions of defined haematocrit or cytocrit, followed by centrifugation at 100,000 g (1 h), and determining the CA activity of the solutions by mass spectrometry. Conditions were 37°C and, approximating intracellular conditions, pH 7.20 with final Cl− concentrations of 60 mm for haemolysates and 10 mm for tsA cell lysates.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was tested by Student's t test where applicable, or by ANOVA followed by a suitable post-test (Bonferoni, comparing selected pairs of data groups, or Tukey, for multiple comparisons).

Mathematical Model of HCO3− and CO2 transport across cell membranes

The purpose of this mathematical model is to simulate the processes of CO2 and HCO3− transfer across the cell membrane, together with the associated diffusion and reaction processes in the intracellular space (see Fig. S2). The transfer of CO2 or HCO3− across the membrane is given by:

| (1) |

where dmX,M is the amount of X (either CO2 or HCO3−) transferred across the membrane per unit time, PX is the membrane permeability of CO2 or HCO3−, respectively, A is the membrane diffusion area (140 μm2 for a human red cell; Geigy, 1960) and d[X] is the concentration difference across the membrane for either of the two substrates. The rates of the CO2 hydration–dehydration reaction in the intracellular compartment are described by:

| (2) |

where ku is the forward reaction rate constant of CO2 hydration (0.15 s−1 at 37°C; cf. Endeward & Gros, 2009), ACA is the factor by which this reaction rate is accelerated due to CA, [CO2], [H+] and [HCO3−] are the concentrations of physically dissolved CO2, of protons and HCO3−, respectively, t is time, and K1′ is the first apparent dissociation constant of carbonic acid (7.9 × 10−7 m at 37°C). K1′ treats the CO2 hydration reaction by assuming a direct conversion of CO2 and H2O to HCO3− and H+ (omitting the intermediate H2CO3), which is correct in the case of the CA-catalysed reaction but constitutes a (generally employed) simplified description of the uncatalysed reaction. As indicated in Fig. S2 (upper part), in the standard case CA was assumed to be homogeneously distributed in the intracellular space; in special cases all intracellular CA was assumed to be concentrated in the immediate neighbourhood of the internal side of the membrane (Fig. S2, lower part). An equation analogous to eqn (2) is used to describe the change of HCO3− concentration per time, d[HCO3−]/dt. The intracellular diffusion processes of CO2 and HCO3− are expressed by:

| (3) |

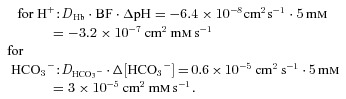

where dmX/dt indicates the movement of substance per unit time between small volume elements of the intracellular space, DX is the diffusion coefficient in the intracellular space, A is the diffusion area between the volume elements considered, and d[X]/dx is the concentration gradient of CO2 or HCO3−, respectively.  was taken be 1.2 × 10−5 cm2 s−1, and

was taken be 1.2 × 10−5 cm2 s−1, and  0.6 × 10−5 cm2 s−1 (cf. Endeward & Gros, 2009). A modified version of eqn (3) had to be used to describe intracellular diffusion of H+, which, due to the extremely low intracellular concentrations and concentration gradients of free H+, occurs almost entirely by haemoglobin-facilitated proton diffusion (Gros & Moll, 1972, 1974; Gros et al. 1976):

0.6 × 10−5 cm2 s−1 (cf. Endeward & Gros, 2009). A modified version of eqn (3) had to be used to describe intracellular diffusion of H+, which, due to the extremely low intracellular concentrations and concentration gradients of free H+, occurs almost entirely by haemoglobin-facilitated proton diffusion (Gros & Moll, 1972, 1974; Gros et al. 1976):

| (4) |

where dmH+/dt is the total amount of protons transferred across the segment at the considered position x, DHb is the intra-erythrocytic diffusion coefficient of haemoglobin (6.4 × 10−8 cm2 s−1 at 37°C; Moll, 1966), BF is the intra-erythrocytic non-bicarbonate buffering power in moles H+/L/ΔpH, mainly due to haemoglobin (63 mm/ΔpH), and dpH/dx is the intracellular pH gradient. The minor contribution of the intra-erythrocytic buffers of lower molecular weight (2,3-bisphosphoglycerate, 2,3-BPG, and adenosine triphosphate, ATP) is ignored in this treatment.

This system of equations is largely analogous to that used previously to describe the exchange of C18O16O between red cells and the extracellular space (Endeward & Gros, 2009), with the exception of proton transport, which did not have to be considered in the earlier model. Also, unlike the treatment there, the extracellular space was treated here as a well-stirred compartment of infinite size, and unstirred layers around the cells were not considered. The example of a cell considered here was the human RBC, whose parameters were inserted into the equations (for details see Endeward & Gros, 2009). The diffusion and reaction processes in the intracellular compartment were modelled by dividing the effective half-thickness of the erythrocyte of 0.8 μm (Forster, 1964) into 80 segments, as indicated in Fig. S2, and with these a finite difference method (as available in MATLAB 2008b) was used to solve the equations numerically.

The equations were solved in such a way as to obtain the amount of substance, i.e. CO2 or HCO3−, taken up into the cell per unit membrane area (in units of moles cm−2) as a function of time (as shown in Figs 8 and 9). The fact that HCO3− transfer across the cell membrane approaches an intracellular HCO3− concentration that is not equal to but in Donnan equilibrium with the extracellular concentration was taken into account as described previously (Itada & Forster, 1977; Endeward & Gros, 2005). The condition of maintaining the Donnan distribution for HCO3− has also the consequence that HCO3− uptake is accompanied by a CO2 efflux (as seen in Fig. 9B).

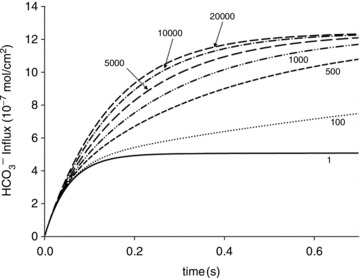

Figure 8. Time courses of bicarbonate influx, expressed as mol HCO3− (cm2 membrane surface area)−1, for various intra-erythrocytic CA activities, calculated with the model illustrated in Fig. S2 (upper scheme).

The numbers on the curves indicate the acceleration factors of CO2 hydration. Therefore, 1 indicates the absence of CA activity, and 20,000 an activity of (20,000 – 1). The dependence of HCO3− influx on CA activity is most pronounced between 1 and 1000, and becomes minor between 5000 and 20,000.

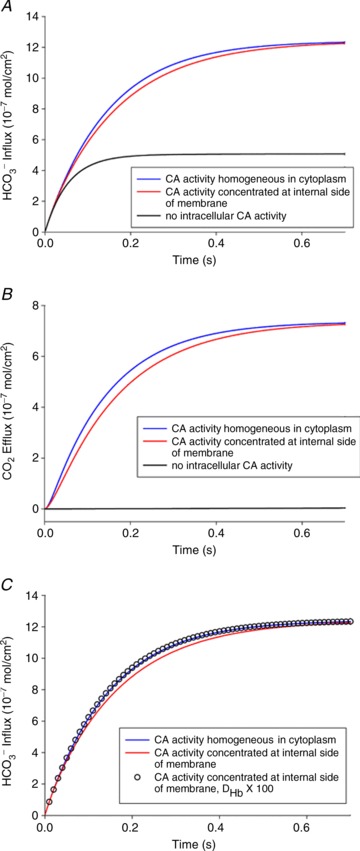

Figure 9. Significance of the subcellular localization of CA for uptake of HCO3− and the associated CO2 release in human red cells.

Uppermost curves (in blue): calculated for a homogeneous intracellular distribution of CA in the cytoplasm of red cells (upper scheme in Fig. S2). Middle curves (in red): calculated for an accumulation of all the CA of the red cell in a thin (0.01 μm) layer immediately adjacent to the internal side of the red cell membrane (lower scheme in Fig. S2). Lowermost curves (black, in A and B): complete absence of CA activity inside a red cell. A, HCO3− influx after a step change in extracellular HCO3− from 25 to 35 mm. B, the efflux of CO2 following the influx of HCO3− shown in A. C, effect of haemoglobin diffusivity on the kinetics of HCO3− exchange. The two curves are identical to the uppermost (blue) and middle (red) curves of A. The results represented by open circles were calculated for the accumulation of all red cell CA at the cytoplasmic side of the membrane, as in the lower (red) curve, with the exception that the diffusivity of haemoglobin was set to 100-fold its true value. This makes both types of CA distribution equivalent in terms of HCO3−/CO2 exchange, indicating that intra-erythrocytic Hb-facilitated proton transport causes the limitation of the process when CA is associated with the membrane.

Results

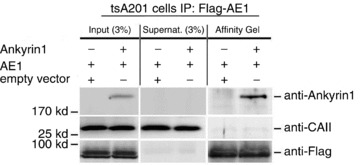

Co-IP of AE1 and CAII

To investigate a possible direct physical interaction between AE1 and CAII in tsA201 cells, a Co-IP assay was performed using an anti-Flag affinity gel. In lysates from tsA201 cells transiently expressing Flag-tagged hAE1, nearly no Co-IP of CAII was found (Fig. 2, right-hand column). Instead, the bulk of CAII protein remained in the supernatant of the Co-IP assay. As a positive control for Co-IP, a protein well known for interaction with hAE1, hANK1 (Bennett & Stenbuck, 1979; Michaely & Bennett, 1995), was coexpressed with Flag-tagged hAE1. Figure 2 shows that hANK1 was indeed co-immunoprecipitated with hAE1, constituting a positive control of the assay. Therefore, the Co-IP assay demonstrates that AE1 and CAII do not interact in tsA cells.

Figure 2. Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) demonstrates interaction of AE1 with ANK1, but not with CAII.

Western blot analysis of aliquots from cell lysates (Input; 3% of the volume of cell lysate added to the affinity gel was applied to the SDS-PAGE gel) from tsA201 cells transfected with pcDNA3–3xFlag-hAE1 expression plasmid (AE1) and pcDNA-hANK1 expression plasmid (Ankyrin) or empty expression vector (empty vector), of aliquots from supernatants of the Co-IP (Supernat.; 3% of the supernatant after centrifugation of the affinity gel was applied to the SDS-PAGE gel), and of eluates from the affinity gel (all of the eluate was applied to the SDS-PAGE gel), using anti-ANK1, anti-CAII or anti-Flag antibodies.

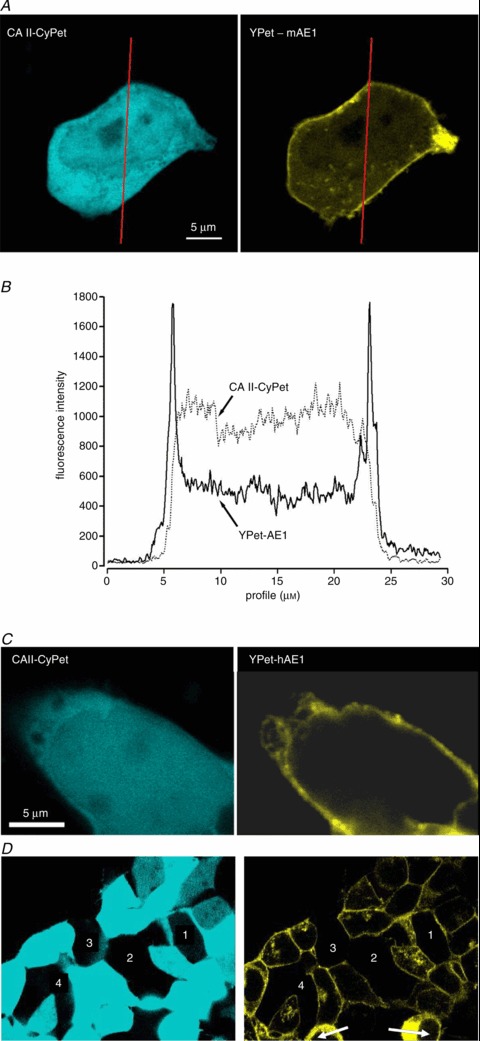

Expression, localization and FRET signal of YPet-AE1 and CAII-CyPet coexpressed in tsA cells

Western Blots were performed as described by Itel et al. (2012) and illustrate in the supplementary Fig. S3 the expression of native CAII and of the fusion proteins CAII-CyPET (see also Fig. 3A) and CAII-V143Y-YPet (see also supplemental Fig. S4b) in tsA201 cells. The molecular mass of the two latter proteins was the expected ∼57 kDa. Figure 3A shows the subcellular localizations of CAII-CyPet (left) and murine YPet-mAE1 (right). It is apparent that the AE1 fusion protein is enriched at the plasma membrane of the tsA cell, with some minor association with intracellular vesicular structures, whereas the CAII fusion protein is homogeneously distributed throughout the cytoplasm, without evident enrichment at the plasma membrane. This is confirmed by the fluorescence intensity profiles of Fig. 3B that were recorded along the red lines shown in Fig. 3A. YPet-mAE1 exhibits low fluorescence intensity in the cytoplasm and marked intensity peaks associated with the plasma membranes. CAII-CyPet shows a high and rather homogeneous intensity across the cell cytoplasm region without enrichment of fluorescence intensity in the region of the plasmalemma. The same distribution pattern is seen for CAII-CyPet and human YPet-hAE1 in Fig. 3C. This suggests that the CAII fusion protein behaves as a typical cytosolic protein without detectable enrichment at the plasma membrane. Figure 3D shows that in a patch of doubly transfected confluent tsA201 cells, regions containing non-transfected cells free of either blue or yellow fluorescence can serve as negative fluorescence controls.

Figure 3. Confocal microscopy of the fluorescent fusion proteins CA II and AE1.

A, confocal microscopic images of a tsA291 cell co-transfected with human CAII-CyPet and murine YPet-AE1 fusion proteins. CyPet was linked to the C terminus of CAII and YPet was linked to the N-terminus of mAE1 B, fluorescence emission intensity profiles at wavelengths appropriate for CyPet and for YPet as recorded along the red lines in A. C, confocal microscopic images of a tsA201 cell co-transfected with human YPet-AE1 and human CAII-CyPet. Comparison of A and C indicates that localization of mAE1 and hAE1 are identical. D, fluorescence control. The figure shows an overview over a patch of confluent tsA201 cells co-transfected with CAII-CyPet and YPet-AE1. Regions 1–4 represent non-transfected cells. Note the absence of non-specific fluorescence in the non-transfected cells, even with saturation of CyPet fluorescence (left panel). Non-saturated CyPet images were devoid of peripheral membrane enhancement (not shown). Arrows in right panel indicate morphologically unhealthy cells.

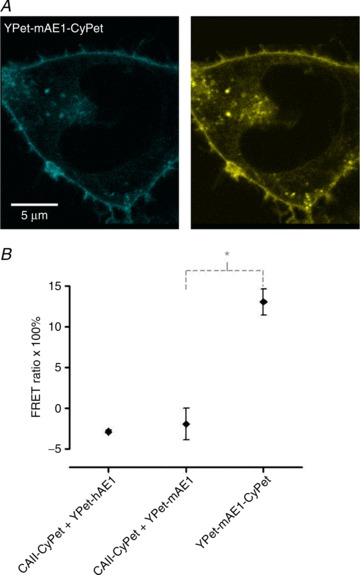

So as not to overlook subtle interactions between CAII and AE1, we checked for evidence of FRET. As described in the Methods, the potential FRET acceptors YPet-mAE1 and YPet-hAE1 were bleached, after which the cells were examined for possible increase in FRET donor emission (ICy,post) over their prebleaching value ICy,pre. An increase in ICy,post, expressed in Fig. 4B as FRET ratio = (ICy,post–ICy,pre)/ICy,post, was never observed in cells coexpressing CAII-CyPet with either YPet-mAE1 or YPet-hAE1 (Fig. 4B). The absence of FRET is evidence against physical interaction of CAII fusion protein with AE1 fusion protein. In contrast, in tsA201 cells expressing the intramolecular FRET control construct CyPet-mAE1-Ypet, YPet bleaching elicited a significant increase in CyPet fluorescence intensity (Fig. 4B). The double-tagged mAE1 thus constitutes a positive FRET control, validating the negative results with the single-tagged CAII and AE1 fusion proteins. The double-labelled mAE1 construct is illustrated in Fig. 4A, in which excitation at 458 nm produced simultaneous blue and yellow fluorescence emission of the membrane-associated mAE1.

Figure 4. FRET measurements of CyPet- and YPet-labelled fusion proteins in tsA201 cells.

A, confocal microscopic images of a tsA201 cell transfected with the doubly labelled construct of mAE1 N-terminally fused with YPet and C-terminally fused to CyPet. Illumination with 458 nm excites both CyPet (left) and YPet (right), the two dyes yielding an identical pattern. This construct gives the positive FRET signal seen in Fig. 5B. B, results of FRET experiments with tsA cells cotransfected with CAII-CyPet and YPet-hAE1 (left), with CAII-CyPet and YPet-mAE1 (centre), and a FRET control in cells transfected with YPet-mAE1-CyPet (right). This latter construct ensures proximity of the two dyes, reflected in its significantly positive FRET signal. *P < 0.01 (t test); n from left to right is 3, 7 and 7. Bars represent SE values.

Figure S4 demonstrates that both CAII constructs, that truncated at the N terminus and the acatalytic CAII-V143Y, are well expressed, exhibit a cytosolic distribution identical to that of the WT CAII fusion protein shown in Fig. 3, and do not affect expression of AE1. Thus, all tested WT and mutant CAII fusion proteins expressed here are homogeneously distributed in the cytoplasm and exhibit no enrichment at the plasma membrane.

Functional effects of the expression of YPet-mAE1 in tsA201 cells

Figure 5 shows that the AE1 fusion protein is functional in tsA201 cells. Figure 5A shows that the CA activity (acceleration factor of CO2 hydration minus 1) of lysed tsA201 cells as measured by 18O mass spectrometry is slightly over 600 in control as well as in AE1-expressing tsA cells (37°C). Figure 5B presents 18O mass spectrometric determinations of  in tsA201 cells. Control cells exhibit a

in tsA201 cells. Control cells exhibit a  of ∼2 × 10−4 cm s−1 (37°C), and this value is not significantly altered in the presence of 10−5

m DIDS, indicating that AE1 is not responsible for the basal HCO3− permeability of tsA cells. Expression of the AE1 fusion protein almost doubles

of ∼2 × 10−4 cm s−1 (37°C), and this value is not significantly altered in the presence of 10−5

m DIDS, indicating that AE1 is not responsible for the basal HCO3− permeability of tsA cells. Expression of the AE1 fusion protein almost doubles  (P < 0.02), and DIDS restores this value to control level (P < 0.02). We conclude that the AE1 fusion protein is functional when expressed in tsA cells, markedly increasing cellular HCO3− permeability.

(P < 0.02), and DIDS restores this value to control level (P < 0.02). We conclude that the AE1 fusion protein is functional when expressed in tsA cells, markedly increasing cellular HCO3− permeability.

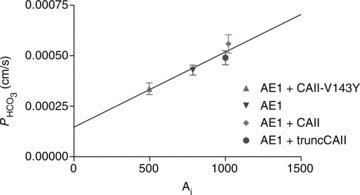

Bicarbonate permeabilities of tsA201 cells expressing YPet-mAE1 together with various CAII-CyPet fusion proteins

Figure 6 shows  values measured in AE1-transfected tsA201 cells coexpressing fluorophore-labelled WT-CAII, truncated CAII and the acatalytic CAII mutant, and plotted vs. corresponding lysate CA activities measured as described above. All data points shown in Fig. 6 are mean values from several preparations. First, the figure shows that expression of tagged WT-CAII as well as of tagged truncated CAII results in enhanced cytosolic CA activity, but expression of CAII-V143Y does not. Secondly, the data are well described by a linear regression line consistent with a positive correlation of

values measured in AE1-transfected tsA201 cells coexpressing fluorophore-labelled WT-CAII, truncated CAII and the acatalytic CAII mutant, and plotted vs. corresponding lysate CA activities measured as described above. All data points shown in Fig. 6 are mean values from several preparations. First, the figure shows that expression of tagged WT-CAII as well as of tagged truncated CAII results in enhanced cytosolic CA activity, but expression of CAII-V143Y does not. Secondly, the data are well described by a linear regression line consistent with a positive correlation of  and intracellular CA activity. The second point from the left (▾) represents tsA201 cells expressing mAE1 together with endogenous CAII only (the conditions of Fig. 5A, right column, and Fig. 5B, third column, which we will call here ‘control’ conditions) with

and intracellular CA activity. The second point from the left (▾) represents tsA201 cells expressing mAE1 together with endogenous CAII only (the conditions of Fig. 5A, right column, and Fig. 5B, third column, which we will call here ‘control’ conditions) with  of 4.3 × 10−4 cm s−1. The leftmost data point (▴) representing expression of acatalytic CAII (see Fig. S4b) with

of 4.3 × 10−4 cm s−1. The leftmost data point (▴) representing expression of acatalytic CAII (see Fig. S4b) with  of 3.4 × 10−4 cm s−1 is moderately but significantly lower than the control value (P < 0.02), and unexpectedly shows marked reduction in endogenous intracellular CA activity. We have confirmed this effect of expression of the CAII-V143Y fusion protein on endogenous CA activity for the untagged CAII-V143Y protein: in this additional series of experiments expression of the CAII mutant reduced intracellular CA activity also by a similar 30% (P < 0.001, n= 8) and, associated with this, a

of 3.4 × 10−4 cm s−1 is moderately but significantly lower than the control value (P < 0.02), and unexpectedly shows marked reduction in endogenous intracellular CA activity. We have confirmed this effect of expression of the CAII-V143Y fusion protein on endogenous CA activity for the untagged CAII-V143Y protein: in this additional series of experiments expression of the CAII mutant reduced intracellular CA activity also by a similar 30% (P < 0.001, n= 8) and, associated with this, a  decreased by ∼22%. This shows that a significant reduction of endogenous CAII expression is induced by expression of both tagged and untagged CAII-V143Y. Moreover, in preliminary experiments with HEK293 cells, we observe also in these cells a strong reduction of intracellular CA activity when coexpressing hAE1-YPet together with CAII-V143Y-CyPet (own unpublished experiments). The rightmost data point in Fig. 6 (♦) represents tsA201 cells expressing the fusion protein with WT CAII (see Fig. S3A). This leads to increased intracellular CA activity in parallel with a statistically significantly increased HCO3− permeability (5.6 × 10−4 cm s−1; P < 0.01). The third data point from the left in Fig. 6 (•) reflects tsA201 cells expressing the fusion protein containing N-terminally truncated CAII (see also Fig. S4A), which should not bind to the AE1 C-terminal cytoplasmic tail. This truncated CAII increased intracellular CA activity to the same level as did WT CAII, from ∼ 800 to ∼ 1000.

decreased by ∼22%. This shows that a significant reduction of endogenous CAII expression is induced by expression of both tagged and untagged CAII-V143Y. Moreover, in preliminary experiments with HEK293 cells, we observe also in these cells a strong reduction of intracellular CA activity when coexpressing hAE1-YPet together with CAII-V143Y-CyPet (own unpublished experiments). The rightmost data point in Fig. 6 (♦) represents tsA201 cells expressing the fusion protein with WT CAII (see Fig. S3A). This leads to increased intracellular CA activity in parallel with a statistically significantly increased HCO3− permeability (5.6 × 10−4 cm s−1; P < 0.01). The third data point from the left in Fig. 6 (•) reflects tsA201 cells expressing the fusion protein containing N-terminally truncated CAII (see also Fig. S4A), which should not bind to the AE1 C-terminal cytoplasmic tail. This truncated CAII increased intracellular CA activity to the same level as did WT CAII, from ∼ 800 to ∼ 1000.  in the presence of truncated CAII is 4.9 × 10−4 cm s−1, significantly higher than control (P < 0.05). Note that the only modest increases in intracellular CA activity by expression of WT-CAII and of truncated CAII expression might result from a suppression of endogenous CAII similar to that observed with CAII-V143Y expression. In conclusion, in cells coexpressing AE1 with all tested CAII variants, the HCO3− permeabilities follow a regression line of

in the presence of truncated CAII is 4.9 × 10−4 cm s−1, significantly higher than control (P < 0.05). Note that the only modest increases in intracellular CA activity by expression of WT-CAII and of truncated CAII expression might result from a suppression of endogenous CAII similar to that observed with CAII-V143Y expression. In conclusion, in cells coexpressing AE1 with all tested CAII variants, the HCO3− permeabilities follow a regression line of  rising moderately with increasing intracellular CA activity. The correlation coefficient of the linear regression of the data points in Fig. 6 is r= 0.96 and the slope of the regression line Δ

rising moderately with increasing intracellular CA activity. The correlation coefficient of the linear regression of the data points in Fig. 6 is r= 0.96 and the slope of the regression line Δ /ΔAi= 3.7 × 10−7 cm s−1 is statistically significantly different from zero (P < 0.05).

/ΔAi= 3.7 × 10−7 cm s−1 is statistically significantly different from zero (P < 0.05).

Figure 6. Bicarbonate permeability of tsA201 cells as a function of intracellular CA activity, Ai.

tsA201 cells transfected with YPet-mAE1 (‘control’) (▾); tsA201 cells co-transfected with CAII-V143Y-CyPet and YPet-mAE1 (▴); co-transfection with WT CAII-CyPet and YPet-AE1 (♦); co-transfection with N-terminally truncated CAII-CyPet and YPet-mAE1 (•). Observed variations of  are linearly related to intracellular CA activity. Correlation coefficient r= 0.90. Bars represent SE values. Number of determinations n= 17, 18, 17 and 33 (from left to right). All permeabilities under expression of the various CAII's are statistically significantly different from the mean control

are linearly related to intracellular CA activity. Correlation coefficient r= 0.90. Bars represent SE values. Number of determinations n= 17, 18, 17 and 33 (from left to right). All permeabilities under expression of the various CAII's are statistically significantly different from the mean control  value (▾, transfection with YPet-mAE1 only). P values between <0.01 and <0.05.

value (▾, transfection with YPet-mAE1 only). P values between <0.01 and <0.05.

CA activity and  in normal and CAII-deficient human RBCs

in normal and CAII-deficient human RBCs

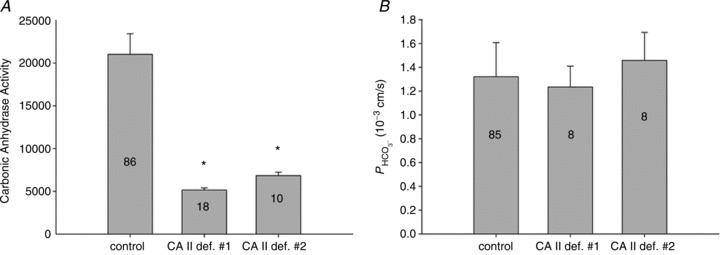

Here, we employ a different approach to test a functionally significant interaction between CAII and AE1, by examining red cells from two patients with homozygous CAII deficiency. Red cells in this disease lack all CAII activity, but maintain substantial erythroid CA activity due to the normal presence of CAI (Sly et al. 1983; Dodgson et al. 1988). While the intracellular CA activity of normal human RBCs at 37°C is 20,000 (Fig. 7A), in agreement with previous determinations (Endeward et al. 2008), the activity in RBCs from both patients is around 5000. Thus, erythroid CAI sustains 25% residual total erythroid CA activity, far in excess of that required for gas exchange at rest and with exercise (Dodgson et al. 1988). Figure 7B shows that the HCO3− permeabilities of normal and CAII-deficient RBCs are indistinguishable at 1.2–1.4 × 10−4 cm s−1, in agreement with previously reported normal values (Endeward et al. 2006, 2008). We conclude that AE1 transport activity in human RBCs is independent of the presence or absence of CAII activity. This complete lack of an effect of CAII on erythroid HCO3− transport may be compared with the moderate, albeit significant, effect of CAII expression in AE1-expressing tsA201 cells, which becomes apparent at a much lower level of absolute CA activity values of ≤1000 (Fig. 6).

Figure 7. Intra-erythrocytic CA activity and bicarbonate permeability of normal (control) and CAII-deficient human red blood cells (the latter from two individuals 1 and 2).

A, while normal human red cells exhibit a CA activity of 20,000, CAII-deficient red cells have an activity of ∼ 5000 due to the remaining CAI in these cells (* indicates statistically significant difference from control CA activity, P < 0.01). B,  is identical regardless of whether CAII is present or completely absent. Numbers of measurements are given inside each column. Bars represent SD.

is identical regardless of whether CAII is present or completely absent. Numbers of measurements are given inside each column. Bars represent SD.

Mathematical simulation of the effect of CA on HCO3− uptake by red cells

These calculations were performed for the conditions of the human RBC, but in principle apply qualitatively to any CA-containing cell. Figure 8 portrays calculated time courses of HCO3− uptake at different intracellular CA activities. The time axis ends at 0.7 s, the capillary transit time in human lung and tissues. It is apparent that for the physiological intracellular CA activity of human RBCs of 20,000 (Fig. 7A), the process of erythroid HCO3− uptake is complete within the capillary transit time. Even for a CA activity of ∼5000, as observed in CAII-deficient RBCs, the capillary transit time suffices to reach completion of HCO3− uptake. However, below a CA activity of 1000 and extending to the complete absence of CA activity (equal to an acceleration factor of CO2 hydration of 1), further deceleration of HCO3− uptake progressively decreases the total HCO3− influx achieved within the capillary transit time. The dependence of the process on CA activity is also reflected in the prediction by the mathematical model, 100 ms after initiation of HCO3− uptake, of a nearly linear gradient of intracellular pHi (ΔpHi of ∼0.02 over the 0.8 μm half-thickness of the red cell) when Ai= 20,000 (with an average pHi of 7.27), but of virtually no intracellular pH gradient when Ai= 1 (pHi= 7.20 everywhere in the cell). Across the range of CA activities between 1 and 1000, erythroid HCO3− uptake depends strongly on intracellular CA activity. Comparison of the initial rates of HCO3− uptake from curves with Ai= 1 and Ai= 500 in Fig. 8 reveals a >2-fold increase, whereas the initial rates from slopes with Ai= 5000 and Ai= 20,000 show only minimal Ai dependence. It is clear from Fig. 8 that AE1-mediated HCO3− fluxes or permeabilities cannot be appraised without knowledge of intracellular CA activity.

Mathematical simulation of membrane HCO3− and CO2 transport, with intracellular CA activity either homogeneously distributed in the cytoplasm or associated with the membrane

Again, these calculations were performed assuming conditions of the human RBC. The aim was to determine whether it makes a difference for the process of HCO3− or CO2 uptake by red cells if total intracellular CA activity is (1) homogeneously distributed in the cytoplasm, as held by classical views, or (2) concentrated at the internal side of the membrane due to binding to membrane protein, as postulated for CAII by Vince and Reithmeier (1998). Figure 9A shows the result for HCO3− uptake by RBCs, when, starting from standard conditions of  = 40 mmHg and extracellular pH (pHe) of 7.40 at 37°C, the extracellular HCO3− concentration [HCO3−]e is subjected to a step increase from 25 to 35 mm. It is apparent that total absence of CA in the cell (the lowermost curve) leads to a drastic slowing of the process of HCO3− uptake, which after a rapid initial influx becomes extremely slow because the reaction required to convert HCO3− in the cell to CO2, thereby maintaining a significant driving force for HCO3− across the cell membrane, is uncatalysed. After a capillary transit time of 0.7 s, HCO3− uptake is far from completion, as also shown in Fig. 9A. If the normal intra-erythrocytic CA activity of 20,000 is assumed to be homogeneously distributed in the cell interior (uppermost curve, in blue) HCO3− uptake is considerably accelerated and reaches completion after about 0.5 s. This is similar for the case when all CA activity of the cell is concentrated in a layer of 0.01 μm thickness (1/80 of 0.8 μm) immediately adjacent to the internal side of the cell membrane (middle curve, in red). However, this latter condition does not lead to a faster HCO3− uptake compared with the homogeneously distributed CA activity, as might have been expected, but to a slightly slower one. In other words, it is somewhat more advantageous for HCO3− uptake to have the CA distributed all over the cell interior than to have it all very close to the membrane. Figure 9B illustrates the process of CO2 efflux associated with HCO3− uptake, reflecting the amount of CO2 leaving the cell after it has been produced by dehydration of the HCO3− taken up. The behaviour of the CO2 efflux is a mirror image of that of the HCO3− influx: an extreme retardation in the absence of CA, and a slightly faster kinetics for homogeneously distributed CA than for a membrane-associated CA. We note that a distribution of the same total CA activity as used in the calculations of Fig. 9, split half-way between cytoplasmic and membrane-bound localization, produces curves intermediate between the middle and the uppermost curves of Fig. 9A and B.

= 40 mmHg and extracellular pH (pHe) of 7.40 at 37°C, the extracellular HCO3− concentration [HCO3−]e is subjected to a step increase from 25 to 35 mm. It is apparent that total absence of CA in the cell (the lowermost curve) leads to a drastic slowing of the process of HCO3− uptake, which after a rapid initial influx becomes extremely slow because the reaction required to convert HCO3− in the cell to CO2, thereby maintaining a significant driving force for HCO3− across the cell membrane, is uncatalysed. After a capillary transit time of 0.7 s, HCO3− uptake is far from completion, as also shown in Fig. 9A. If the normal intra-erythrocytic CA activity of 20,000 is assumed to be homogeneously distributed in the cell interior (uppermost curve, in blue) HCO3− uptake is considerably accelerated and reaches completion after about 0.5 s. This is similar for the case when all CA activity of the cell is concentrated in a layer of 0.01 μm thickness (1/80 of 0.8 μm) immediately adjacent to the internal side of the cell membrane (middle curve, in red). However, this latter condition does not lead to a faster HCO3− uptake compared with the homogeneously distributed CA activity, as might have been expected, but to a slightly slower one. In other words, it is somewhat more advantageous for HCO3− uptake to have the CA distributed all over the cell interior than to have it all very close to the membrane. Figure 9B illustrates the process of CO2 efflux associated with HCO3− uptake, reflecting the amount of CO2 leaving the cell after it has been produced by dehydration of the HCO3− taken up. The behaviour of the CO2 efflux is a mirror image of that of the HCO3− influx: an extreme retardation in the absence of CA, and a slightly faster kinetics for homogeneously distributed CA than for a membrane-associated CA. We note that a distribution of the same total CA activity as used in the calculations of Fig. 9, split half-way between cytoplasmic and membrane-bound localization, produces curves intermediate between the middle and the uppermost curves of Fig. 9A and B.

Figure 9C serves to illustrate the mechanism responsible for the difference between the uppermost and middle curves in Fig. 9A and B. The curves represented by the open circles were calculated with the identical assumption underlying the middle curves of Fig. 9, namely accumulation of all intra-erythrocytic CA at the internal side of the membrane. However, the intracellular diffusion coefficient of haemoglobin was increased 100-fold above its actual value of 6.4 × 10−8 cm2 s−1, and as apparent from Fig. 9C, this causes the open circles to coincide with the uppermost curves. This shows that the relatively slow diffusion of intra-erythrocytic haemoglobin and thus the relatively slow intra-erythrocytic facilitated proton transport are responsible for a retardation of HCO3− uptake and CO2 release when CA is concentrated at the internal side of the membrane rather than being, like haemoglobin, distributed homogeneously across the intracellular space (see Discussion).

Discussion

CA supports membrane HCO3− transport most efficiently when it is homogeneously distributed in the cytoplasm

Figure 9 shows that a homogeneous presence of CA in the cytoplasm is predicted to be more favourable for uptake of HCO3− and release of CO2 than restriction of intracellular CA to a 10 nm-thick layer immediately adjacent to the membrane. Although the latter situation guarantees that any HCO3− or CO2 transferred across the membrane has instantaneous access to an extremely high CA activity, it nonetheless slows down the uptake process. This situation is reflected in the model calculation, which 100 ms after the start of HCO3− uptake shows in the immediate vicinity of the membrane a pHi slightly higher when CA is concentrated at the membrane (7.28) than when CA is homogeneously distributed in the cytoplasm (7.27), and a 50% greater intracellular pH gradient of ΔpH = 0.03 over 0.8 μm compared with the value under homogeneous CA distribution (ΔpH = 0.02). Thus, in the former case protons right at the membrane are consumed somewhat more rapidly by the HCO3− dehydration reaction, but in the entire remainder of intracellular space the dehydration reaction is extremely slow and the development of the intracellular gradients of H+ and HCO3− depends essentially on diffusion processes alone. A model in which the CA is partly concentrated at the membrane and partly distributed in the cytoplasm yields uptake curves intermediate between the middle and uppermost curves of Fig. 9, i.e. such a model is also inferior to that with homogeneous intracellular CA distribution. This result may appear counterintuitive. Indeed, the intuitive view that CA concentrated in the vicinity of the membrane should favour faster HCO3− transport has added to the great attractiveness of the metabolon concept. What is the reason for the contrary result? The answer is given in Fig. 9C, which shows that 100-fold acceleration of intracellular haemoglobin diffusion causes the difference in uptake kinetics between the two models to disappear. Since haemoglobin is the major intra-erythrocytic buffer, and its property of being a (mobile) buffer is its only function in the present model, this result leads to the following interpretation: when, for example, HCO3− has permeated the membrane and the catalysed dehydration reaction sets in, consuming protons to form CO2, the reaction can only continue as far as sufficient amounts of protons are available at the site where the reaction takes place. The available protons, however, are bound to the major buffer haemoglobin, and the haemoglobin is homogeneously distributed across the intra-erythrocytic space. Thus, delivery of protons from the cell interior towards the membrane region by haemoglobin-facilitated H+ diffusion becomes rate-limiting, as free diffusion of cytosolic protons is negligible at the low intracellular H+ concentration. The slow diffusion of haemoglobin inside the red cell is also slow in comparison with the rates of other components of the uptake process (Moll, 1966; Gros & Moll, 1972, 1974; Junge & McLaughlin, 1987). If haemoglobin diffusion were 100 times faster, this limitation would not exist. Note that this problem is not restricted to RBCs, but applies to all cells, because the total H+ buffer capacity in most cells reaches 30–50% that of RBCs, although the average buffer mobility is somewhat greater (Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002; Zaniboni et al. 2003; Swietach & Vaughan-Jones, 2005; Swietach et al. 2005, 2010). We conclude that for all cells, colocalization of CA with the major buffers maximizes rates of HCO3− transport. This situation applies when both are distributed homogeneously in the cytoplasm. This requires HCO3− (in the case of AE1-mediated HCO3− uptake, with HCO3− diffusion tightly coupled to oppositely directed diffusion of Cl−) to diffuse to the locations of buffer and CA. These diffusion processes are much faster than facilitated proton transport because both HCO3− and Cl− have rather high intracellular diffusivities (see Methods). The following illustrative example assumes identical concentration gradients of HCO3− and buffered protons. These intracellular concentration gradients must be identical due to the 1:1 stoichiometry of the reaction of H+ and HCO3−. However, the gradients have opposite signs because, in the given example, we look either at the diffusion of HCO3− from the membrane into the cell interior (CA homogeneously distributed in the cytoplasm), or, alternatively, at the diffusional transport of protons from the cell interior towards the membrane (CA concentrated at the internal side of the membrane). In both cases, electroneutrality of these intracellular ion fluxes will be maintained by the intracellular Cl− fluxes required to maintain the Hamburger shift. With an arbitrarily chosen concentration difference of 5 mm for both HCO3− and bound protons (the free H+ being negligible), the products of diffusion coefficients and concentration gradients then are

|

HCO3− diffusion inside cells – and similarly Cl− diffusion – thus is two orders of magnitude faster than proton transport. We note that an entirely analogous consideration applies to the process of CO2 uptake, where CO2 diffusion into the cell interior is much faster than proton transport into the cell interior. This fact makes it more efficient for the cell to localize the CA to the site(s) of optimal buffering.

Neither CAII colocalization with AE1 nor FRET signal attributable to an AE1–CAII interaction is detectable in CAII-expressing tsA201 cells

No subcellular localization studies of intact non-erythroid cells coexpressing AE1 and CAII have been reported to date. In Figs 3, 4 and S4 we present clear evidence that the fluorescent fusion proteins WT human CAII, N-terminally truncated CAII and the acatalytic V143Y CAII are all distributed homogeneously across the cytoplasm of transfected tsA201 cells. Qualitatively as well as quantitatively, the CAII fluorescence intensities show no accumulation of either CAII variant in the vicinity of the membrane. In contrast, fluorescent human and murine AE1 fusion proteins clearly colocalize with the cell surface membranes (with a small fraction of AE1 associated with intracellular vesicular structures). This clear result is confirmed by the absence of a FRET signal arising from coexpressed CyPet-labelled CAII and YPet-labelled human or murine AE1, whereas a doubly labelled AE1 provides a strong positive FRET signal. Thus, the present morphological studies show no evidence for physical association between CAII and AE1 within a distance of 8–10 nm. Note that the present fusion proteins have a molecular weight around 27 kDa greater than the native proteins CAII (29 kDa) and AE1 (∼100 kDa). This could in principle disturb a close interaction of the two proteins. For this reason the dyes were attached to the C terminus of CAII and the N terminus of AE1, whereas the sites proposed to interact are the N terminus of CAII and the C terminus of AE1, in the hope of minimizing potential steric hindrance to the postulated interaction. For the case of CAII, a suppression of AE1–CAII interaction by the fluorophore attached to CAII can be ruled out by the finding described above that fluorophore-tagged and untagged CAII-V143Y reduce  in the same way. A further strong argument against a CAII–AE1 complex in the present cell model is the absence of CAII–AE1 co-immunoprecipitation, in which native CAII and AE1 tagged at the N terminus with the small 2.7 kDa Flag were studied. We conclude that the two heterologous proteins in the present expression model do not form a physical complex at the plasma membrane.

in the same way. A further strong argument against a CAII–AE1 complex in the present cell model is the absence of CAII–AE1 co-immunoprecipitation, in which native CAII and AE1 tagged at the N terminus with the small 2.7 kDa Flag were studied. We conclude that the two heterologous proteins in the present expression model do not form a physical complex at the plasma membrane.

Vince and Reithmeier (1998) investigated red cell ghosts washed only once, i.e. mildly in comparison with earlier studies (Tappan, 1968; Rosenberg & Guidotti, 1968; Randall & Maren, 1972). Immunofluorescence imaging of smears of these pink ghosts revealed both CAII and AE1 homogeneously distributed across the ghosts. Upon treatment with the AE1-binding tomato lectin to promote clustering of AE1, they observed clustering of both AE1 and CAII. Since the authors did not co-stain with antibodies to both AE1 and CAII, co-localization of the two proteins in the clusters was not definitively shown. On the other hand, Campanella et al. (2005) observed co-localization of AE1 and CAII by confocal immunofluorescence analysis of intact human RBCs fixed in 0.5% acrolein and subsequently permeabilized in 0.1% Triton. Whereas AE1 immunostaining of the red cell membrane was continuous, CAII immunostaining was consistently punctate, and did not entirely coincide with that of AE1. The authors did not exclude the possibility of a fixation artifact, especially as more aggressive fixation promoted restriction to the cell periphery even of haemoglobin staining. This latter result was tentatively explained by binding of denatured or oxidized haemoglobin to the AE1 N terminus. Thus, additional approaches to assess CAII localization in intact red cells would be useful.

Lack of evidence for a functional metabolon of CAII and AE1 in tsA201 cells

Figure 8 shows clearly that calculated HCO3− uptake rate by cells, as when induced by an extracellular step change in HCO3− or Cl− concentration and observed by an intracellular pH dye, depends very strongly on intracellular CA activity. This dependency is most pronounced in the CA activity range between 0 and ∼1000, exactly the activity range of cell lines such as HEK293, tsA201 or MDCK cells. Therefore, valid comparisons of HCO3− fluxes between cells in which various CAII constructs are expressed can be made only if the intracellular CA activity is carefully controlled. These controls have often been missing in the literature reporting such flux measurements.

The present method of measuring HCO3− permeability differs from this classical type of experimental approach. We estimate  by observing the exchange of 18O between CO2, HCO3− and H2O under conditions of perfect chemical – but not isotopic – equilibrium (Endeward & Gros, 2005; Endeward et al. 2006). The moderate dependency of

by observing the exchange of 18O between CO2, HCO3− and H2O under conditions of perfect chemical – but not isotopic – equilibrium (Endeward & Gros, 2005; Endeward et al. 2006). The moderate dependency of  on Ai that we see in Fig. 6 is due to the fact that the calculation of

on Ai that we see in Fig. 6 is due to the fact that the calculation of  from 18O exchange measurements assumes perfect stirring of the intracellular space (Endeward & Gros, 2005). As we have shown previously (Endeward & Gros, 2009), this is of course not realistic and the lack of intracellular mixing causes a delay in the cellular uptake of the substance considered, due to a build-up of the substance transferred into the cell at the internal side of the membrane. For CO2 and HCO3−, this delay is diminished with increasing intracellular CA activity, which promotes interconversion between CO2 and HCO3−, thus reducing the build-up of CO2 or HCO3− at the membrane and accelerating the respective fluxes. As a consequence, slightly increasing HCO3− fluxes and slightly increasing

from 18O exchange measurements assumes perfect stirring of the intracellular space (Endeward & Gros, 2005). As we have shown previously (Endeward & Gros, 2009), this is of course not realistic and the lack of intracellular mixing causes a delay in the cellular uptake of the substance considered, due to a build-up of the substance transferred into the cell at the internal side of the membrane. For CO2 and HCO3−, this delay is diminished with increasing intracellular CA activity, which promotes interconversion between CO2 and HCO3−, thus reducing the build-up of CO2 or HCO3− at the membrane and accelerating the respective fluxes. As a consequence, slightly increasing HCO3− fluxes and slightly increasing  are expected to parallel increases in Ai, as evident in Fig. 6 between CA activities of 500 and 1000. Between CA activities of 5000 and 20,000, such an effect is no longer visible (Fig. 7), consistent with prediction (Fig. 8).

are expected to parallel increases in Ai, as evident in Fig. 6 between CA activities of 500 and 1000. Between CA activities of 5000 and 20,000, such an effect is no longer visible (Fig. 7), consistent with prediction (Fig. 8).

From expression of the three types of CAII constructs in tsA201 cells, the following conclusions can be drawn from Fig. 6:

1. WT CAII. Expression of heterologous wild-type CAII fusion protein (◆) increases Ai over that in the mere presence of endogenous CAII (▾), and in parallel causes a moderate but significant increase in  (P < 0.01). This could potentially be compatible with increased concentration of an AE1–CAII metabolon. However, in view of the general dependence of

(P < 0.01). This could potentially be compatible with increased concentration of an AE1–CAII metabolon. However, in view of the general dependence of  on Ai, such an explanation is not required. The fact that in the present study expression of WT CAII has a noticeable effect on

on Ai, such an explanation is not required. The fact that in the present study expression of WT CAII has a noticeable effect on  is at variance with the report by Sterling et al. (2001a,b), who found no effect of WT CAII expression in HEK293 cells, and proposed that the endogenous CAII activity of HEK293 cells is sufficient for a full metabolon effect. The cause of this discrepancy with the present results is not clear, but does not affect the current finding that

is at variance with the report by Sterling et al. (2001a,b), who found no effect of WT CAII expression in HEK293 cells, and proposed that the endogenous CAII activity of HEK293 cells is sufficient for a full metabolon effect. The cause of this discrepancy with the present results is not clear, but does not affect the current finding that  is positively and linearly related to Ai (Fig. 6).

is positively and linearly related to Ai (Fig. 6).

2. Acatalytic CAII. Expressing the (almost) acatalytic CAII mutant V143Y fusion protein decreases endogenous CA activity from ∼800 to ∼480. This pronounced effect causes a reduction in  , which follows the general dependency of