Abstract

Vasodilator-induced elevation of intracellular cyclic AMP (cAMP) is a central mechanism governing arterial relaxation but is incompletely understood due to the diversity of cAMP effectors. Here we investigate the role of the novel cAMP effector exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac) in mediating vasorelaxation in rat mesenteric arteries. In myography experiments, the Epac-selective cAMP analogue 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP-AM (5 μm, subsequently referred to as 8-pCPT-AM) elicited a 77.6 ± 7.1% relaxation of phenylephrine-contracted arteries over a 5 min period (mean ± SEM; n= 6). 8-pCPT-AM induced only a 16.7 ± 2.4% relaxation in arteries pre-contracted with high extracellular K+ over the same time period (n= 10), suggesting that some of Epac's relaxant effect relies upon vascular cell hyperpolarization. This involves Ca2+-sensitive, large-conductance K+ (BKCa) channel opening as iberiotoxin (100 nm) significantly reduced the ability of 8-pCPT-AM to reverse phenylephrine-induced contraction (arteries relaxed by only 35.0 ± 8.5% over a 5 min exposure to 8-pCPT-AM, n= 5; P < 0.05). 8-pCPT-AM increased Ca2+ spark frequency in Fluo-4-AM-loaded mesenteric myocytes from 0.045 ± 0.008 to 0.103 ± 0.022 sparks s-1μm-1 (P < 0.05) and reversibly increased both the frequency (0.94 ± 0.25 to 2.30 ± 0.72 s−1) and amplitude (23.9 ± 3.3 to 35.8 ± 7.7 pA) of spontaneous transient outward currents (STOCs) recorded in isolated mesenteric myocytes (n= 7; P < 0.05). 8-pCPT-AM-activated STOCs were sensitive to iberiotoxin (100 nm) and to ryanodine (30 μm). Current clamp recordings of isolated myocytes showed a 7.9 ± 1.0 mV (n= 10) hyperpolarization in response to 8-pCPT-AM that was sensitive to iberiotoxin (n= 5). Endothelial disruption suppressed 8-pCPT-AM-mediated relaxation in phenylephrine-contracted arteries (24.8 ± 4.9% relaxation after 5 min of exposure, n= 5; P < 0.05), as did apamin and TRAM-34, blockers of Ca2+-sensitive, small- and intermediate-conductance K+ (SKCa and IKCa) channels, respectively, and NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester, an inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase (NOS). In Fluo-4-AM-loaded mesenteric endothelial cells, 8-pCPT-AM induced a sustained increase in global Ca2+. Our data suggest that Epac hyperpolarizes smooth muscle by (1) increasing localized Ca2+ release from ryanodine receptors (Ca2+ sparks) to activate BKCa channels, and (2) endothelial-dependent mechanisms involving the activation of SKCa/IKCa channels and NOS. Epac-mediated smooth muscle hyperpolarization will limit Ca2+ entry via voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels and represents a novel mechanism of arterial relaxation.

Key points

Relaxation of vascular smooth muscle, which increases blood vessel diameter, is often mediated through vasodilator-induced elevations of intracellular 3′-5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), although the mechanisms are incompletely understood.

In this study we investigate the role of the novel cAMP effector exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac) in mediating vasorelaxation in rat mesenteric arteries.

We show that Epac mediates vasorelaxation in mesenteric arteries by facilitating the opening of several subtypes of Ca2+-sensitive K+ channel within the endothelium and on vascular smooth muscle.

Epac-mediated hyperpolarization of the smooth muscle membrane brought about by opening of these channels acts to limit Ca2+ entry via voltage-gated Ca2+ channels leading to vasorelaxation.

This represents a potentially important, previously uncharacterised mechanism through which vasodilator-induced elevation of cAMP can regulate vascular tone and thus blood flow.

Introduction

The relaxation of vascular smooth muscle, which increases blood vessel diameter, is often mediated through vasodilator-induced elevations of intracellular 3′-5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) (Morgado et al. 2012). cAMP levels rise within vascular cells following the binding of vasodilators such as adrenaline and adenosine to cell surface Gs-coupled receptors that stimulate the activity of the cAMP-producing enzyme adenylyl cyclase. The vasculature expresses three distinct classes of cAMP effector proteins: cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) ion channels and the more recently discovered exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac) (de Rooij et al. 1998; Kawasaki et al. 1998). This diversity in effectors suggests that the mechanisms by which cAMP induces vasorelaxation are likely to be both varied and complex and to differ between species and vascular bed. In general, cAMP induces arterial relaxation either by decreasing cytosolic Ca2+ within smooth muscle cells, or by altering the Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile proteins. These effects have been largely attributed to the activation of PKA and subsequent downstream phosphorylation events that lead to:

Increased Ca2+ uptake into intracellular stores or a decrease in the net influx of Ca2+ into smooth muscle cells (Mundina-Weilenmann et al. 2000; Akata, 2007a).

Activation of K+ currents that hyperpolarize the smooth muscle cell membrane and reduce Ca2+ influx by decreasing the activity of voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels (Nelson et al. 1990; Nelson & Quayle, 1995).

Decreased Ca2+ sensitivity of myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation, leading to a reduction in actin–myosin cross-bridge formation and thus relaxation (Akata, 2007b).

Disruption of the relationship between MLC phosphorylation and the interaction of actin and myosin filaments (Beall et al. 1999; Woodrum et al. 1999; Salinthone et al. 2008).

cAMP also facilitates vasorelaxation originating from the activation of Gs-coupled receptors on the endothelium. In endothelial cells, adenosine- and adrenaline-elicited increases in intracellular cAMP levels have been shown to induce Ca2+ influx by directly activating CNG ion channels (Cheng et al. 2008; Shen et al. 2008). The elevation of endothelial Ca2+ acts as a trigger for the generation and release of a range of mediators from the endothelium that induce relaxation of the underlying smooth muscle. These Ca2+-dependent signals include nitric oxide (NO), prostacyclin and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) (Serban et al. 2010). The ‘classical’ EDHF pathway involves the opening of Ca2+-sensitive, small- and intermediate-conductance K+ (SKCa and IKCa) channels which causes endothelial hyperpolarization (Edwards et al. 2010). In some vessels these hyperpolarizing currents spread to subjacent smooth muscle via gap junctions (de Wit & Griffith, 2010), and here cAMP has been shown to facilitate electrotonic spread by regulating the permeability and conductance of myoendothelial gap junctions (Chaytor et al. 2002; Griffith et al. 2002). Activation of PKA in endothelial cells can also stimulate the production of NO in a Ca2+-independent manner by phosphorylating nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and increasing its sensitivity to Ca2+-calmodulin (Ferro et al. 2004).

The vasorelaxant roles of the third and most recently identified cAMP effector, Epac, are understandably less well defined than those involving PKA or CNG ion channels. Epacs, which act as guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) for the small Ras-related G proteins Rap1 and Rap2 (de Rooij et al. 1998; Kawasaki et al. 1998), are abundant in the vasculature where they modulate cytokine signalling, strengthen endothelial barrier function, participate in vascular remodelling and regulate ion channel function (Yokoyama et al. 2008; Doebele et al. 2009; Purves et al. 2009; Parnell et al. 2012). Recent reports also suggest roles for Epac in the cAMP-induced regulation of vascular tone (Sukhanova et al. 2006; Roscioni et al. 2011; Zieba et al. 2011). These involve changes in the sensitivity of the contractile proteins through Rap-initiated alteration of MLC phosphorylation. Since a hallmark of Epac's activity in numerous other cell types is its ability to mobilize Ca2+ from internal stores, either through the modulation of ryanodine receptors (RyRs) and/or through inositol trisphosphate (IP3)-dependent pathways (Schmidt et al. 2001; Kang et al. 2003; Pereira et al. 2007; Oestreich et al. 2009; Purves et al. 2009), we investigated whether Epac could also modulate vascular contractility through changes in cytosolic Ca2+.

Here we report a novel role for Epac in the regulation of rat mesenteric vascular tone whereby Epac modulates intracellular Ca2+ levels to activate several classes of Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels known to induce membrane hyperpolarization. Using a combination of myography, Ca2+ imaging and electrophysiology, we show that selective activation of Epac within mesenteric myocytes increases the frequency of localized Ca2+ release from areas of the sarcoplasmic reticulum close to the plasma membrane and that these sub-membrane Ca2+ sparks activate surface Ca2+-activated large-conductance K+ (BKCa) channels. As a result, sustained BKCa channel activation induces a membrane hyperpolarization which will limit Ca2+ entry via voltage-gated Ca2+ channels leading to cAMP-induced, but PKA-independent, vasorelaxation. We also demonstrate that a significant proportion of Epac's vasorelaxant effect originates in the endothelium where activation of Epac induces a sustained increase in cytosolic Ca2+ and where activation of the Ca2+-sensitive enzyme NOS and the opening of SKCa and IKCa channels are involved in the initiation of arterial relaxation.

Methods

Animals

Tissues were obtained from adult male Wistar rats (175–200 g; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA) which were killed via a rising concentration of CO2 followed by cervical dislocation. Animal care conformed to the requirements of the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

Myography

First- or second-order branches of rat superior mesenteric arteries were dissected in a physiological saline solution (PSS) containing (mm): 137 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 0.44 NaH2PO4, 0.42 Na2HPO4, 4.17 NaHCO3, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 Hepes and 10 glucose (pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). Ring segments of mesenteric arteries were mounted onto a pair of jaws of a small artery myograph (model 500A; DMT, Aarhus, Denmark). Arteries were allowed to rest in PSS while the bath temperature was raised to 37°C. Passive tension was adjusted to optimise the detection of active force during isometric contraction. Contraction of arteries was induced by application either of a 80 mm K+ solution, made by replacing 74.6 mm NaCl in the PSS with KCl, or of 3 μm phenylephrine to the normal PSS. Only arteries showing a sustained contraction (relaxation less than 15% over a 5 min period following peak contraction) were used. The presence or absence of functional endothelium was assessed by application of 10 μm acetylcholine (ACh) (Furchgott & Zawadzki, 1980). In experiments requiring a functional endothelium, only arteries showing a >90% relaxation to ACh were analysed. In some experiments the endothelium was mechanically disrupted by insertion of a human hair into the lumen of the vessel. Here, only arteries showing a <20% relaxation to ACh following endothelial disruption were analysed. Where indicated, arteries were pre-treated with 100 nm iberiotoxin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) for 5 min, a combination of 1 μm TRAM-34 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 100 nm apamin (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) for 10 min, or 50 μm l-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester (l-NAME) for 1 h prior to contraction.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry the following antibodies were used: mouse anti-Epac (sc-28366) primary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), rabbit anti-von Willebrand Factor (A 0082) primary antibody (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Mesenteric arteries were embedded using CRYO-M-BED (Bright Instrument, Huntingdon, UK) on a cork disc and frozen with isopentane chilled using liquid N2. Transverse sections (12 μm) were cut using a Leica CM 1950 cryostat and collected on 0.2% (w/v) gelatin-coated slides. Slices were fixed for 5 min using 2% (w/v) paraformaldehyde dissolved in PBS (in mm: 2.7 KCl, 1.5 KH2PO4, 137 NaCl, 2.16 Na2HPO4, pH 7.4) and quenched for 10 min using a 100 mm glycine buffer (pH 7.4). Slices were then permeabilized for 10 min using PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 (pH 7.4) and washed three times with PBS for 5 min each time. Slices were blocked for 1 h with antibody buffer containing 2% (v/v) goat serum, 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.05% (v/v) Triton X-100 dissolved in sodium/sodium citrate buffer (SSC) containing (mm): 150 NaCl, 15 Na3-citrate, pH 7.2. Slices were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies were diluted with antibody buffer at a dilution of: anti-Epac, 1:200; anti-von Willebrand factor, 1:300. Primary antibodies were washed three times with SSC containing 0.05% (v/v) Triton-X 100 for 10 min each. Slices were then incubated with secondary antibodies, diluted at ×500 with antibody buffer, at room temperature for 1 h. Secondary antibodies were washed three times with SSC containing 0.05% Triton-X 100 for 10 min each. Slices were then washed with distilled water, and air-dried. Finally, slices were mounted using DAKO fluorescent mounting medium (Dako) and covered with size 1 coverslips. Fluorescent signals were detected using a Leica (SP2 AOBS) microscope system.

Cell isolation

Rat mesenteric arterial smooth muscle cells were isolated by enzymatic digestion of second-order branches of the rat superior mesenteric artery as previously described (Hayabuchi et al. 2001). Intact sheets of rat mesenteric artery endothelial cells were isolated using a method adapted from Snead et al. (1995). Briefly, arteries were cut into ring segments measuring approximately 2 mm in length, and were digested by incubation in a solution containing (mg ml−1): 0.6 collagenase, 0.4 DNase I, 0.8 papain, 0.6 1, 4-dithioerythritol and 1.0 BSA in PSS containing 0.1 mm CaCl2, at 37°C for 45 min. The resultant cell suspension was centrifuged at 200 g for 5 min, prior to re-suspension of the cell pellet in a small volume of PSS containing 0.1 mm CaCl2. The cell suspension contained mesenteric myocytes, as well as morphologically identifiable sheets of endothelial cells.

Expression of GST-RalGDS-RBD

The fusion protein GST-RalGDS-RBD, consisting of glutathione S-transferase (GST) fused to the Rap binding domain (RBD) of Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator (RalGDS), was expressed from the pGEX4T3-GST-RalGDS-RBD plasmid, kindly donated by Professor Johannes Bos (University Medical Centre, Utrecht, The Netherlands), in the BL21 strain of Escherichia coli as described previously (Van Triest et al. 2001).

Rap1·GTP pull-down assay

Two hundred microlitres of glutathione-sepharose 4B beads, 10% (v/v) in PBS (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK), was washed twice in lysis buffer (mm): 50 Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 200 NaCl; 2 MgCl2; containing 1% (v/v) IGEPAL® CA-630; 10% (v/v) glycerol and 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (all Sigma-Aldrich). E. coli lysate (3 μg of total protein) containing GST-RalGDS-RBD was mixed with the beads for 1 h at 4°C. Second-order proximal rat superior mesenteric arteries were incubated with 5 μm 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-2′-O-methyladenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate-AM (8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP-AM; Biolog Life Science Institute, Bremen, Germany) in PBS at room temperature (18–22°C) for 10 min, homogenised in 300 μl ice-cold lysis buffer (per artery) and centrifuged at 16,100 g for 10 min at 4°C. One-tenth of the supernatant was removed and heated at 98°C for 5 min in 2× Laemmli sample buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) for later assessment of total Rap1 levels. The remaining supernatant was mixed with the washed GST-RalGDS-RBD-bound sepharose beads for 1 h at 4°C. After washing the beads four times in ice-cold lysis buffer, proteins were eluted in 2× Laemmli sample buffer and heated at 98°C for 5 min. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide-Tris gels and transferred electrophoretically onto nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond ECL, GE Healthcare). Immunoblotting was performed as previously described (Sampson et al. 2003). Anti-Rap1A/1B antibody was used to assess the levels of Rap1 and active GTP-bound Rap1 (Rap1·GTP) in each sample.

Detection of phosphorylated vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) Ser157

Second-order proximal rat superior mesenteric arteries were incubated with 5 μm 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP-AM in PBS at room temperature (18–22°C) for 10 min then homogenized as above. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with antibodies against phospho-VASP Ser157. Rat mesenteric arterial smooth muscle cells were kept in short-term culture in fully supplemented Medium 231 containing 100 U ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin (all Gibco, Paisley, UK). Cells were serum-starved for 48 h in serum-free Medium 231 prior to stimulation with the indicated concentrations of: 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP-AM; N6- benzoyladenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (N6-Bnz-cAMP); N6-benzoyladenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate, acetoxymethyl ester (N6-Bnz-cAMP-AM); (Biolog Life Science Institute); forskolin (Merck-Millipore, Nottingham, UK) or the equivalent volume of vehicle (DMSO) for 30 min at 37°C prior to cell lysis. In some experiments, cells were pre-incubated with PKI-(Myr-14–22)-amide (Enzo Life Sciences, Exeter, UK), for 20 min to inhibit PKA. Cells were lysed by scraping in ice-cold lysis buffer containing 0.5% (v/v) Triton-X 100 and 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail. Lysates were centrifuged at 16,100 g for 10 min at 4°C and supernatants heated at 98°C for 5 min in 2× Laemmli sample buffer. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting as described above. Where indicated, membranes were stripped at room temperature for 20 min with membrane stripping buffer (mm): 200 glycine; 1% (w/v) SDS; 1% (v/v) Tween-20, pH 2.2, then washed thoroughly in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.001% (v/v) Tween-20 (TBS-T), prior to incubation in blocking buffer (5% (w/v) BSA in TBS-T) and re-probing of the membrane with anti-α smooth muscle actin.

Antibodies

For immunoblotting the primary antibodies used were: Epac1 (5D3) mouse mAb (#4155); Rap1A/Rap1B (26B4) rabbit mAb (#2399); phospho-VASP (Ser157) antibody (#3111); and VASP antibody (#3112) (New England Biolabs, Hitchin, UK). Monoclonal anti-α smooth muscle actin antibody (A 2547) was bought from Sigma-Aldrich. The secondary antibodies used were: anti-mouse IgG (H+L) polyclonal antibody and anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) polyclonal antibody (Stratech Scientific, Newmarket, UK).

Ca2+ measurements

Freshly isolated mesenteric myocytes were incubated with 5 μm Fluo-4-AM (Molecular Probes, Paisley, UK) in PSS containing 0.1 mm CaCl2 for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. De-esterification was achieved by placing the cells in PSS containing 0.1 mm CaCl2 for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. Intracellular Ca2+ stores were replenished by placing cells in buffered saline bath solution (mm): 6 KCl, 134 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 Hepes, 10 glucose (pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH) for 5 min at room temperature. Freshly isolated sheets of rat mesenteric artery endothelial cells were incubated with 1 μm Fluo-4-AM in PSS containing 2 mm CaCl2 for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. De-esterification was allowed to take place for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Cells were viewed using a Carl Zeiss LSM 510 high-speed confocal laser-scanning microscope, coupled to an Axio Observer Z1 inverted microscope equipped with a Fluar 40×/1.30 Oil M27 oil objective lens (Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany). Fluo-4-AM-loaded cells were excited with 488 nm light from an argon ion laser and the emitted fluorescence was collected using a 500–550 nm band-pass filter. Ca2+ spark activity in mesenteric myocytes was captured by line scans in the sub-plasmalemma of the cell, parallel to the cell membrane in unstimulated cells, in cells that had been exposed to 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP-AM, or in cells that had been exposed to 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP-AM following a 20 min pre-incubation with 5 μm PKI-(Myr-14–22)-amide (Enzo Life Sciences). Images were captured at 960 μs per scan and 3000 scans were made on each line. Global [Ca2+]i was measured in Fluo-4-AM-loaded endothelial cells by capturing frame scans via a Neofluar 40×/1.30 Oil DIC oil objective lens every 983 ms over 600 frames. Data were captured and analysed by region of interest analysis using AIM software, version 3.2 SP2 (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany).

Electrophysiology

Spontaneous transient outward currents (STOCs) were recorded in freshly isolated mesenteric myocytes using the whole-cell recording technique and an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The pipette-filling solution contained (mm): 140 KCl, 3 MgCl2, 0.2 EGTA, 10 Hepes and 3 Na2ATP, pH 7.2. The superfusing bath solution contained (in mm): 6 KCl, 134 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2 and 10 Hepes, pH 7.4. STOCs were recorded at a holding potential of −20 mV and defined as events deviating from the baseline by a factor of 4 standard deviations above baseline noise. Iberiotoxin and ryanodine were from Sigma-Aldrich and Merck-Millipore, respectively. All experiments were performed at room temperature (18–22°C)

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Intergroup differences were analysed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Student–Newman–Keuls test for multiple comparisons, or Student's t test for simple comparisons; levels of significance were *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Results

Selective activation of Epac relaxes isolated segments of mesenteric artery

Epac1 is ubiquitously expressed and is detectable in both smooth muscle and endothelial cells in rat mesenteric arteries (Fig. 1A). We were unable to confirm the expression of Epac2 in this vascular bed as antibodies against Epac2 produced multiple immunoreactive bands on Western blots of mesenteric lysates (data not shown). Epac2 is believed to be expressed predominantly in brain, neuroendocrine and endocrine tissues (Kawasaki et al. 1998), although Epac2 expression has been reported in human airway smooth muscle cells and human microvascular endothelial cells (Hong et al. 2007; Roscioni et al. 2009). Epac1/2 can be selectively activated within cells by the well-characterised Epac-specific cAMP analogue 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (Enserink et al. 2002), or its more membrane permeant acetoxymethyl (AM) ester version (Vliem et al. 2008). The activation of Epac by cAMP promotes GDP for GTP exchange on the small monomeric G-protein Rap1 and thus the amount of GTP-bound Rap1 (Rap1·GTP) within a cell can give an indication of the level of Epac activity. To confirm that 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP-AM (hereafter 8-pCPT-AM) selectively activates Epac in rat superior mesenteric artery, we assessed the effects of this compound on Rap1·GTP levels in whole arteries, as well as on the phosphorylation status of VASP Ser157, a PKA substrate (Butt et al. 1994; Smolenski et al. 1998). Rap1·GTP levels were determined by incubating arterial lysates with fusion proteins comprising GST and the Rap-binding domain of Ral-guanine nucleotide-dissociation stimulator (GST-RalGDS-RBD), which binds only to the active GTP-bound form of Rap1. Glutathione-sepharose beads were then used to specifically pull-down Rap1·GTP, which was quantified by Western blot analysis. Figure 1B (top panel left) shows that addition of 5 μm 8-pCPT-AM causes an increase in Rap1·GTP in mesenteric arteries, indicating Epac activation. Importantly, 5 μm 8-pCPT-AM did not induce phosphorylation of VASP at Ser157, thus showing that the PKA pathway is not activated under these conditions (Fig. 1B, top panel right). Indeed, exposure of mesenteric myocytes to considerably higher concentrations of 8-pCPT-AM (200 μm) did not cause phosphorylation of VASP (Ser157), indicating no cross-activation of PKA (Fig. 1B, bottom panel). By contrast, stimulation with N6-Bnz-cAMP, a specific activator of PKA, and forskolin, an adenylyl cyclase activator, both induced VASP (Ser157) phosphorylation in these cells.

Figure 1. Selective Epac activation relaxes isolated segments of mesenteric artery by mechanisms that depend upon membrane hyperpolarization.

A, Top: confocal images of thin transverse sections of rat mesenteric artery labelled with (left) or without (right) anti-Epac1 and visualized by addition of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibodies. Middle: magnified section of rat mesenteric artery dual labelled with mouse anti-Epac1 and rabbit anti-von Willebrand Factor (vWF), an endothelial marker. Vessel lumen is on the right of each image. Epac1 distribution was visualized by the addition of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibodies (left); and vWF by the addition of Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (centre). Image overlay shows co-localization of Epac1 and vWF (yellow) in the endothelial cell layer. Bottom: Western blot analyses of rat brain, aorta and mesenteric artery homogenates immunoblotted with anti-Epac1. B, Top: exposure to 8-pCPT-AM increases the amount of activated, GTP-bound Rap1 (Rap1·GTP) in second-order rat mesenteric arteries (left), but does not induce phosphorylation of the PKA substrate VASP (Ser157) (right). The total Rap1 level in these lysates was assessed by immunoblotting non-pull-down fractions with anti-Rap1A/1B (Rap1 Total). Membranes immunoblotted with anti-phospho-VASP Ser157 (pVASP Ser157) were stripped and re-probed with anti-α smooth muscle actin as a loading control. Bottom: exposure to 200 μm 8-pCPT-AM does not induce phosphorylation of the PKA substrate VASP (Ser157). Rat mesenteric myocytes were incubated with 8-pCPT-AM, N6-Bnz-cAMP or forskolin. Cells in the control lane were incubated in vehicle (DMSO) alone. Cells were lysed and the proteins within the lysates separated and immunoblotted with antibodies against total VASP (top) or phospho-VASP Ser157 (pVASP Ser157) (bottom). In lysates immunoblotted with anti-VASP (top), phosphorylated VASP appears as a slower-migrating band. C and D, segments of second-order branches of rat mesenteric artery were mounted in a two-channel artery myograph and constricted with 3 μm phenylephrine (PE) (C) or exposure to an extracellular solution containing 80 mm K+ (D). Relaxation responses were measured in the absence (control) or presence of 8-pCPT-AM (5 μm). E, bar chart summarizing experiments in C and D and showing percentage relaxation over a 5 min period following peak contraction. **P < 0.01.

Having established that exposure to 5 μm 8-pCPT-AM activates Epac in mesenteric arteries, while concentrations as high as 200 μm have no effect on PKA activity, we investigated the effects of 8-pCPT-AM upon arterial relaxation. Isolated segments of rat mesenteric artery were constricted with phenylephrine and the presence of functional endothelium was assessed by application of 10 μm ACh, which relies upon an intact endothelium to induce relaxation (Furchgott & Zawadzki, 1980) (Fig. 1C). Application of phenylephrine alone caused a sustained contraction, with arteries relaxing by only 7.1 ± 1.5% over 5 min following peak contraction (n= 6). Application of 5 μm 8-pCPT-AM to arteries pre-constricted with phenylephrine induced a relaxation of 77.7 ± 7.1% over the same time period (P < 0.01, n= 6; Fig. 1C, E).

8-pCPT-AM was much less effective at inducing relaxation in arteries pre-constricted with an extracellular solution containing high potassium (80 mm K+; Fig. 1D). Exposure to 80 mm K+-containing solutions induced a well-sustained contraction with arteries relaxing by only 4.6 ± 0.8% over a period of 5 min following peak contraction (n= 10). Application of 8-pCPT-AM (5 μm) to arteries pre-constricted with 80 mm K+ induced a relaxation of 16.7 ± 2.4% over the same time period (n= 10, P < 0.01). High K+ solutions constrict arteries by directly depolarizing the smooth muscle membrane and increasing Ca2+ entry through voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels. Since the membrane potential is effectively clamped to depolarized values under these conditions, relaxation mechanisms that rely on membrane hyperpolarization are inactive. This suggests that in rat mesenteric arteries a substantial part of Epac's mechanism of action relies upon the ability to hyperpolarize endothelial and/or smooth muscle cell membranes.

Epac-induced arterial relaxation is partially dependent upon the activation of BKCa channels

In smooth muscle cells, BKCa channel activation is known to play a pivotal role in cell membrane hyperpolarization prior to relaxation (Nelson et al. 1990; Nelson & Quayle, 1995). We thus assessed the sensitivity of Epac-induced vasorelaxation to iberiotoxin, a potent and selective BKCa channel inhibitor. Pre-incubation with iberiotoxin (100 nm) significantly reduced the ability of 8-pCPT-AM to induce relaxation in arteries pre-constricted with phenylephrine (Fig. 2). 8-pCPT-AM induced only a 35.0 ± 8.5% relaxation over a 5 min period compared to 77.7 ± 7.1% under control conditions (n= 5 and 6, P < 0.05; Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Epac-induced relaxation of isolated segments of mesenteric artery is partially dependent upon activation of BKCa channels.

A, pre-incubation in the selective BKCa channel inhibitor iberiotoxin (100 nm) for 5 min prior to contraction with phenylephrine (PE; 3 μm) significantly reduced the ability of 8-pCPT-AM to relax segments of rat mesenteric artery. B, bar chart summarizing percentage relaxation induced by 8-pCPT-AM over a 5 min period following peak contraction with PE in the presence and absence of iberiotoxin. *P < 0.05.

A number of potential mechanisms could account for Epac-induced activation of BKCa channels. A range of smooth muscle relaxants that raise intracellular levels of cAMP have, for example, been shown to increase the activity of ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ release channels (RyRs) located on regions of the sarcoplasmic reticulum in close proximity to the inner side of the plasma membrane (Porter et al. 1998; Mauban et al. 2001; Pucovsky et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2006). Localized Ca2+ release from RyRs (subsurface Ca2+ sparks) is known to activate plasma membrane BKCa channels and induce membrane hyperpolarization, which decreases Ca2+ entry via voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, lowering global Ca2+ and exerting a vasorelaxing effect (Jaggar et al. 2000). We thus investigated the possibility that Epac induces vasorelaxation by modulating Ca2+ spark activity in mesenteric myocytes.

Epac activation increases the frequency of submembrane Ca2+ sparks in mesenteric myocytes

Figure 3A shows submembrane Ca2+ sparks recorded in Fluo-4-AM-loaded cells isolated from rat mesenteric artery following stimulation with 8-pCPT-AM (5 μm). Under basal conditions, sparks were observed at a frequency of 0.045 ± 0.008 s-1μm-1 and with an amplitude of 2.51 ± 0.21 F/F0 (Fig. 3B and C; n= 38 sparks recorded from 18 cells). The rise time was 23.3 ± 1.3 ms and the decay half-time, t1/2, was 31.9 ± 3.8 ms (Fig. 3D and E). These parameters are in keeping with Ca2+ sparks recorded from other vascular beds (Jaggar et al. 2000), including mesenteric arteries from mice (Zheng et al. 2008). Application of 8-pCPT-AM (5 μm) caused an approximate 2-fold increase in spark frequency to 0.103 ± 0.022 s-1μm-1 (P < 0.05; Fig. 3B; n= 52 recorded from 14 cells). Importantly, this increase was also seen in the presence of PKI-(Myr-14–22)-amide (5 μm), a potent, cell-permeant and highly specific inhibitor of PKA (Dalton & Dewey, 2006; Murray, 2008). Incubation with 5 μm PKI-(Myr-14–22)-amide under conditions equivalent to those used for spark recordings inhibits the phosphorylation of VASP in mesenteric myocytes, indicating that PKA is inactive under these conditions and thus unable to contribute to 8-pCPT-AM-induced increases in spark activity (Fig. 3F). Application of 8-pCPT-AM had no significant effect on spark amplitude, rise time or decay half-time (Fig. 3C–E).

Figure 3. Epac activation increases the frequency of submembrane Ca2+ sparks in mesenteric smooth muscle cells.

A, i and ii, Ca2+ sparks recorded in freshly isolated Fluo-4-AM-loaded mesenteric myocytes following application of 8-pCPT-AM (5 μm). Ca2+ spark activity was captured by line scans in the sub-plasmalemma of the cell, parallel to the cell membrane. Line scan data showing submembrane Ca2+ sparks recorded over a period of 3 s along a 16 μm line in the cell shown in i. iii, fractional fluorescence (F/F0) changes with time, where F is ‘spark-related’ fluorescence and F0 background fluorescence for spark activity shown in ii above. B–E, bar charts summarizing spark frequency (B), amplitude (C), rise time (D) and decay half-time (E) under unstimulated (basal) conditions, following application of 8-pCPT-AM (5 μm) alone, or after pre-incubation with the selective PKA inhibitor PKI-(Myr-14–22)-amide (PKI; 5 μm for 20 min) followed by application of 8-pCPT-AM (5 μm) in the presence of PKI. Application of vehicle (DMSO) alone had no effect on spark frequency, amplitude, rise time or decay half time (data not shown). *P < 0.05; n.s., not significant. F, incubation of mesenteric myocytes with 5 μm PKI inhibits phosphorylation of the PKA substrate VASP (Ser157). Rat mesenteric myocytes were left untreated, or were pre-incubated with PKI (5 μm) for 20 min, prior to stimulation with N6-Bnz-cAMP-AM (100 nm) or forskolin (100 nm). Cells were lysed and proteins within the lysates separated on 10% polyacrylamide-Tris gels and immunoblotted with an antibody directed against phospho-VASP Ser157 (pVASP Ser157). The membrane was then stripped, and re-probed with anti-α smooth muscle actin as a loading control.

Selective activation of Epac increases STOC frequency and amplitude in mesenteric myocytes

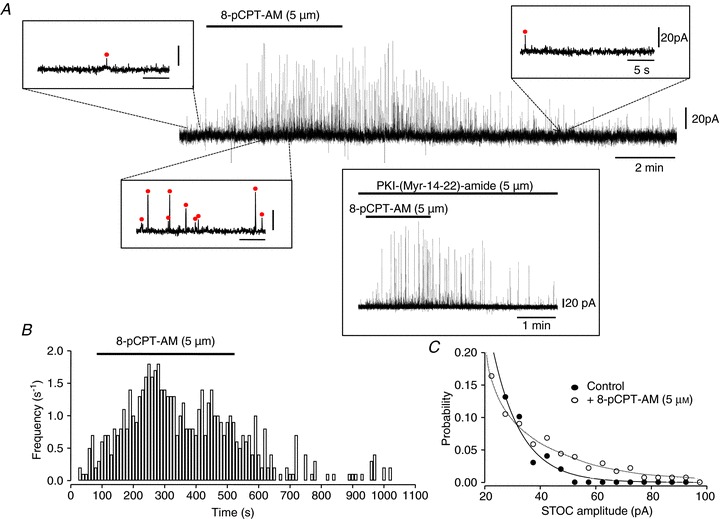

To assess whether the observed increase in Ca2+ spark frequency affects BKCa channel activity, we used the whole-cell recording technique to record STOCs in isolated mesenteric myocytes under control conditions and following the activation of Epac (Fig. 4). STOCs are generated by the synchronised opening of groups of BKCa channels, and thus changes in STOC frequency or amplitude give a direct indication of changes in underlying BKCa channel behaviour. Application of 8-pCPT-AM (5 μm) significantly increased the frequency of STOCs recorded in isolated mesenteric myocytes from 0.94 ± 0.25 to 2.30 ± 0.72 s−1 (n= 7, P < 0.05; Fig. 4A and B). There was also an increase in STOC amplitude (from 23.9 ± 3.3 to 35.8 ± 7.7 pA; n= 7, P < 0.05) due to an increase in the probability of larger events occurring in the presence of 8-pCPT-AM (Fig. 4C). These 8-pCPT-AM-induced changes in STOC activity were insensitive to the potent PKA inhibitor PKI-(Myr-14–22)-amide (5 μm; n= 4, Fig. 4A inset), indicating that they occur independently of PKA activation. 8-pCPT-AM-induced currents were, however, sensitive to iberiotoxin (100 nm; n= 6), confirming that they were mediated by the opening of BKCa channels (Fig. 5A and B), and to ryanodine (30 μm; n= 5; Fig. 5C and D), confirming that they are activated by the underlying activity of RyRs. This increase in outward current would be expected to induce membrane hyperpolarization, and in support of this, current clamp recordings of single isolated mesenteric myocytes showed a 7.9 ± 1.0 mV (n= 10) hyperpolarization in response to exposure to 5 μm 8-pCPT-AM, which could be reversed by the application of iberiotoxin (100 nm; n= 5; Fig. 5E).

Figure 4. Epac activation increases the activity of STOCs in mesenteric smooth muscle cells.

A, spontaneous transient outward currents (STOCs) recorded in isolated mesenteric myocytes using the whole-cell recording technique at a holding potential of −20 mV. Addition of 8-pCPT-AM (5 μm) to the superfusing bath solution at the point indicated by the bar above the trace reversibly increased both STOC frequency and amplitude. Examples of STOCs recorded in the presence and absence of 8-pCPT-AM are also shown on an expanded timescale. STOCs were defined as events deviating from the baseline by a factor of 4 standard deviations above baseline noise (indicated by a circle above an individual event). Pre-incubation of cells with 5 μm PKI-(Myr-14–22)-amide for 20 min before recording had no effect on the ability of 8-pCPT-AM to increase STOC activity (inset; n= 4). In these experiments, PKI-(Myr-14–22)-amide was also included in the pipette-filling solution. B, histogram of STOC frequency against time for trace shown in A. C, probability against STOC amplitude for trace shown in A.

Figure 5. Epac-induced activation of STOCs is sensitive to ryanodine and iberiotoxin and induces membrane hyperpolarization.

STOCs recorded in isolated mesenteric myocytes using the whole-cell recording technique application of iberiotoxin (100 nm; A, B) or ryanodine (30 μm; C, D) to the superfusing bath solution reversed the increases in STOC frequency and amplitude induced by the application of 8-pCPT-AM (5 μm). E, current clamp recordings of single isolated myocytes show a 7.9 ± 1.0 mV (n= 10) hyperpolarization in response to exposure to 8-pCPT-AM (5 μm), which is blocked by the application of iberiotoxin (100 nm; n= 5). The resting membrane potential recorded in these cells was −53.2 ± 3.1 mV (n= 10).

Epac-induced relaxation of mesenteric artery is partially dependent on an intact endothelium

Since our data indicate that Epac-mediated relaxation relies heavily on the ability to hyperpolarize vascular cell membranes (Fig. 1C), we also investigated the involvement of the endothelium. Endothelial cell hyperpolarization is associated with the classical EDHF pathway and follows from the opening of endothelial SKCa and IKCa channels (Edwards et al. 2010). Figure 6A shows that mechanical disruption of the endothelium suppressed the ability of 8-pCPT-AM (5 μm) to reverse phenylephrine-induced constriction. In arteries showing less than 20% relaxation to ACh following disruption of the endothelial cell layer, 8-pCPT-AM induced only a 24.8 ± 4.9% relaxation over 5 min following peak contraction, compared to 77.7 ± 7.1% relaxation when the endothelium was functionally intact (n= 5 and 6, P < 0.05; Figs 1C, E and 6A, D).

Figure 6. Epac-mediated relaxation is partially dependent on an intact endothelium: involvement of calcium-sensitive K+ channels and NOS.

A–C, mechanical disruption of the endothelial cell layer (A) or pre-incubation with a combination of TRAM-34 and apamin (1 μm and 100 nm, respectively) for 10 min (B) or l-NAME (50 μm) for 1 h (C) significantly reduces the ability of 8-pCPT-AM (5 μm) to induce relaxation in arteries pre-constricted with phenylephrine (PE; 3 μm). Disruption of the endothelium was assessed by the ability of ACh to induce relaxation. D, bar chart summarizing data shown in A–C. E, mean fractional fluorescence (F/F0) against time for 12 responsive Fluo-4-AM-loaded mesenteric endothelial cells within a freshly isolated sheet. Application of 8-pCPT-AM (10 μm) to bath indicated by bar. Application of vehicle (DMSO) alone had no effect.

Arteries with functionally intact endothelium (as determined by ACh-induced relaxation) were next incubated in a combination of 100 nm apamin and 1 μm TRAM-34 for 10 min to selectively block SKCa and IKCa channels, respectively, prior to contraction with phenylephrine. Pre-incubation in apamin and TRAM-34 significantly reduced the ability of 8-pCPT-AM to induce relaxation, with arteries relaxing by only 44.5 ± 8.2% over a 5 min period (n= 10, P < 0.05; Fig. 6B, D). Similarly, pre-incubation with l-NAME (50 μm), a potent inhibitor of NOS1, 2 and 3, for 1 h prior to constriction with phenylephrine significantly reduced the ability of 8-pCPT-AM to induce relaxation (arteries relaxed by only 19.2 ± 3.5% over a 5 min period; n= 6, Fig. 6C, D). These data imply that activation of both SKCa and IKCa channels and NOS is involved in Epac-induced vasorelaxation.

A potential mechanism by which Epac could activate both SKCa and IKCa channels and NOS in endothelial cells is via an elevation of cytosolic Ca2+. We thus measured Ca2+ levels in freshly isolated sheets of mesenteric endothelial cells following application of 8-pCPT-AM (Fig. 6E). In Fluo-4-AM-loaded mesenteric cells 8-pCPT-AM (10 μm) induced a sustained increase in cytosolic Ca2+ in 67.8 ± 11.3% of cells within four separate endothelial sheets (n= 140 cells).

Discussion

cAMP has long been recognised as a primary mediator of relaxant signals in the vasculature (Murray, 1990). While three major classes of cAMP-binding effector proteins have now been identified, only pathways involving its traditional target PKA have been elucidated in any detail. This represents a shortfall in our understanding of the signalling mechanisms involved in regulating the contractile state of smooth muscle cells and ultimately the control of blood flow. A number of studies have highlighted the existence of cAMP-dependent relaxant pathways that persist following PKA inhibition (EcklyMichel et al. 1997; White et al. 2001), but the origin of these PKA-independent effects has remained elusive. Our data suggest that the novel cAMP effector Epac mediates vasorelaxation in mesenteric arteries by previously undescribed pathways that are strongly dependent on the ability to hyperpolarize endothelial and/or smooth muscle cell membranes and involve the opening of several classes of Ca2+-sensitive vascular K+ channel.

Epac-mediated vasorelaxation comprises an endothelial-dependent component and a component that persists following disruption of the endothelial cell layer. This latter element is consistent with reports from other vascular (portal vein), intestinal and airway smooth muscles that show that Epac activation affects the phosphorylation of the contractile proteins by a Rap1-induced reduction in the activity of the small GTPase RhoA (Roscioni et al. 2011; Zieba et al. 2011). Our data suggest that other Epac-induced pathways work in conjunction with this. We show that 8-pCPT-AM is much less effective at inducing relaxation in arteries pre-constricted with high K+-containing solutions than in arteries pre-constricted with phenylephrine. Phenylephrine and high K+ both induce constriction by raising intracellular Ca2+, but via different routes, and Epac's differential effect on relaxation implies an inability to directly or indirectly inhibit Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, which are opened by high K+-induced membrane depolarization. One explanation for this is that part of Epac's mechanism of action relies upon the ability to hyperpolarize the membrane, a mechanism that is rendered inoperative by high extracellular K+. In support of this we show that under physiological conditions activation of Epac in mesenteric smooth muscle cells increases the activity of sub-surface Ca2+ sparks, which activates surface BKCa channels and induces a membrane hyperpolarization of ∼10 mV. This level of hyperpolarization will decrease the activity of smooth muscle voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, reducing Ca2+ influx and promoting relaxation. Modulation of Ca2+ spark activity is known to be a key mechanism controlling vascular function. Smooth muscle relaxants that elevate intracellular levels of cAMP have been shown to increase both spark frequency and the activity of BKCa channels (Porter et al. 1998; Mauban et al. 2001; Pucovsky et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2006), and defective coupling between Ca2+ sparks and BKCa channels has been linked to dysregulation of vasorelaxation and to hypertension (Amberg et al. 2003). There is also evidence that spark–STOC coupling regulates blood pressure in intact animals, as decreased coupling in mice in which the β-subunit of BKCa channels has been ablated is associated with elevated blood pressure and left ventricular hypertrophy (Brenner et al. 2000; Pluger et al. 2000).

Ca2+ sparks originate from the opening of single or tightly clustered groups of RyRs on the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and Epac activation is known to modulate the open probability of these channels in a number of different tissues. In pancreatic β cells, Epac2 induces Ca2+-dependent exocytosis and insulin secretion by mobilising Ca2+ through RyRs (Ozaki et al. 2000; Kashima et al. 2001). In cardiac myocytes, a large cAMP-regulated macromolecular complex containing both Epac and RyRs has been reported (Dodge-Kafka et al. 2005), and functional studies show Epac-mediated modulation of RyR activity (Pereira et al. 2007; Oestreich et al. 2009). Epac may increase RyR activity through direct interaction between Rap1 and RyRs (Kang et al. 2003; Tsuboi et al. 2003), or via the activation of intermediate kinases to phosphorylate and increase the Ca2+ sensitivity of the RyR channel. A current consensus view in the cardiac literature is that Epac's effect on RyRs is mediated through Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII)-dependent phosphorylation (Pereira et al. 2007, 2012, 2013; Hothi et al. 2008; Oestreich et al. 2009). The Ca2+ required to activate this Ca2+-sensitive enzyme is released from IP3-sensitive stores following Rap-dependent activation of phospholipase Cɛ (PLCɛ), phosphoinositol hydrolysis and the formation of IP3 (Schmidt et al. 2001; Oestreich et al. 2009; Pereira et al. 2012). The Epac-mediated PLC, IP3R and CaMKII pathway has also recently been implicated in the modulation of cardiac intranuclear Ca2+ and the activation of the prohypertrophic transcription factor myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) (Pereira et al. 2012). This provides a possible mechanistic basis for previous reports linking Epac activation to the induction of hypertrophic gene expression and the development of cardiac hypertrophy (Morel et al. 2005), and emphasises the need to understand signalling via this pathway in terms of both cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology.

The mechanisms by which cAMP induces vasorelaxation are likely to vary between vascular beds. We have previously shown that activation of Epac in aortic myocytes induces a transient increase in intracellular Ca2+ as opposed to an increase in spark activity (Purves et al. 2009). The physiological significance of this difference is unclear but may relate to fundamental differences in the function of the aorta as opposed to smaller resistive vessels. The aorta has a unique structure and function amongst vascular beds. It is a large vessel that is exposed to high levels of mechanical strain and the elastic properties of its vascular wall allow it to dampen pulses in pressure during the cardiac cycle while maintaining a continuous flow at the level of the capillaries between beats. While frequency modulation of Ca2+ sparks, and consequently STOCs, has been shown to regulate the membrane potential and arterial tone in cerebral resistance arteries, coronary arteries and the mesenteric artery (Benham & Bolton, 1986; Nelsonet al. 1995; Bychkovet al. 1997; Jaggaret al. 1998; Porteret al. 1998), STOCs do not routinely occur in the aorta. This in itself suggests that aortic and mesenteric responses to Epac activation may be different between resistive and conduit arteries.

Our data also demonstrate that disruption of the endothelial cell layer, or selective inhibition of SKCa and IKCa channels, substantially reduces the ability of 8-pCPT-AM to induce relaxation in phenylephrine-contracted arteries. This suggests that activation of Epac triggers the classical EDHF pathway in mesenteric arteries, which involves the opening of SKCa and IKCa channels located on the surface of endothelial cells and, in the case of IKCa channels, on endothelial projections that protrude through the internal elastic lamina that separates the endothelium from the underlying smooth muscle (Sandow et al. 2006). The endothelial hyperpolarization that results from outward K+ currents flowing through open SKCa and IKCa channels can spread directly to the smooth muscle via myoendothelial gap junctions (Sandow et al. 2002) or, alternatively, the effluxing K+ can activate Na+/K+-ATPase and inwardly rectifying K+ channels on smooth muscle cells to induce smooth muscle hyperpolarization (Edwards et al. 1998).

Pre-incubation with the potent NOS inhibitor l-NAME also significantly attenuated the effects of 8-pCPT-AM (from 80% relaxation under control conditions to only 20% following inhibition of NOS), suggesting that the generation and release of NO is also a central feature of Epac's mode of action. Epac potentially triggers both NO and EDHF pathways separately through the global elevation of endothelial [Ca2+]i. Alternatively, opening of SKCa and IKCa channels and membrane hyperpolarization may precede, and be a requirement for, activation of NOS. In this model, localized subcellular increases of Ca2+ would selectively activate SKCa and/or IKCa, inducing membrane hyperpolarization and enhancing Ca2+ influx through (voltage-insensitive) Ca2+-permeable channels by increasing the inward electrochemical gradient for Ca2+ (Nilius & Droogmans, 2001). This Ca2+ influx may then be responsible for the activation of NOS. A similar mechanism has been proposed for ACh-evoked NO release in rat superior mesenteric artery (Stankevicius et al. 2006), although other studies using the same artery suggest that store depletion, rather than hyperpolarization, may be the key driving force behind Ca2+ entry (McSherry et al. 2005). Interestingly, our data show that activation of Epac within endothelial cells induces a transient Ca2+ peak followed by a slight shoulder and plateau. This may be indicative of rapid Ca2+ release from the internal stores followed by a slower and sustained Ca2+ influx. A recent study of cultured human microvascular endothelial (HMEC-1) cells showed that β2-adrenoceptor-mediated activation of Epac induced IP3 accumulation and an increase in intracellular Ca2+, suggesting that Epac may target IP3-sensitive stores as a primary mode of action in the endothelium (Mayati et al. 2012).

In summary, we demonstrate for the first time that activation of the cAMP effector Epac mediates vasorelaxation in mesenteric arteries by facilitating the opening of several subtypes of Ca2+-sensitive K+ channel within the endothelium and on vascular smooth muscle. In endothelial cells, Epac activates SKCa and IKCa channels, which underlie the classical EDHF pathway, to induce hyperpolarization of the endothelium, which will spread to the subjacent smooth muscle. This happens in conjunction with the activation of NOS, either via simultaneous activation due to a rise in global Ca2+, or because hyperpolarization or store depletion induces additional Ca2+ influx. NOS presumably produces NO, which diffuses to the smooth muscle to induce relaxation via cGMP/protein kinase G and the activation of K+ channels. In addition, in smooth muscle, Epac activation separately increases the frequency of Ca2+ sparks, which activate surface BKCa channels to induce membrane hyperpolarization. Epac-mediated hyperpolarization of the smooth muscle membrane brought about by a combination of these pathways will act to limit Ca2+ entry via voltage-gated Ca2+ channels leading to cAMP-mediated, but PKA-independent, vasorelaxation. This mechanism is likely to work in conjunction with Epac-induced changes in the sensitivity of the contractile proteins and represents a potentially important, previously uncharacterised mechanism through which the vasodilator-induced elevation of cAMP can regulate vascular tone.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Johannes Bos (University Medical Centre, Utrecht, the Netherlands) for the pGEX4T3-GST-RalGDS-RBD plasmid.

Glossary

- 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP-AM

8-(4-chloro-phenylthio)-2′-O-methyladenosine-3′, 5-cyclic mono-phosphate-AM

- ACh

acetylcholine

- AM

acetoxymethyl

- BKCa

Ca2+-sensitive, large-conductance K+ channel

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- cAMP

3′-5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CaMKII

Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II

- CNG

cyclic nucleotide-gated

- EDHF

endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor

- Epac

exchange protein directly activated by cAMP

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- IKCa

Ca2+-sensitive, intermediate-conductance K+ channel

- IP3

inositol trisphosphate

- l-NAME

l-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester

- MLC

myosin light chain

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- PE

phenylephrine

- PKA

cAMP-dependent protein kinase

- PLCɛ

phospholipase Cɛ

- PSS

physiological saline solution

- RalGDS-RBD

Ral-guanine nucleotide-dissociation stimulator Rap-binding domain

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- SKCa

Ca2+-sensitive, small-conductance K+ channel

- SSC

sodium/sodium citrate buffer

- STOCs

spontaneous transient outward currents

- VASP

vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein

- vWF

von Willebrand factor

Additional information

Competing interests

None.

Author contributions

O.Ll. R.: Ca2+ measurements in vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells, active Rap1 pull-down assay, detection of phosphorylated VASP (Ser157), immunoblotting, conception and design of experiments, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. T.K.: myography experiments, immunohistochemistry, conception and design of experiments, analysis and interpretation of data, revising the article critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. R.B.-J.: analysis and interpretation of STOC data, membrane potential recordings, drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. J.M.Q.: conception and design of experiments, revising the article critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. C.D.: electrophysiology experiments, conception and design of experiments, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. All experiments were conducted in the Institute of Integrative Biology, Biosciences Building and Institute of Translational Medicine, Sherrington Buildings, and Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease, UCD Building, University of Liverpool.

Funding

This work was supported by a British Heart Foundation project grant PG/10/018.

References

- Akata T. Cellular and molecular mechanisms regulating vascular tone. Part 1: basic mechanisms controlling cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and the Ca2+-dependent regulation of vascular tone. J Anesth. 2007a;21:220–231. doi: 10.1007/s00540-006-0487-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akata T. Cellular and molecular mechanisms regulating vascular tone. Part 2: regulatory mechanisms modulating Ca2+ mobilization and/or myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Anesth. 2007b;21:232–242. doi: 10.1007/s00540-006-0488-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberg GC, Bonev AD, Rossow CF, Nelson MT, Santana LF. Modulation of the molecular composition of large conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channels in vascular smooth muscle during hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:717–724. doi: 10.1172/JCI18684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall A, Bagwell D, Woodrum D, Stoming TA, Kato K, Suzuki A, Rasmussen H, Brophy CM. The small heat shock-related protein, HSP20, is phosphorylated on serine 16 during cyclic nucleotide-dependent relaxation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11344–11351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham CD, Bolton TB. Spontaneous transient outward currents in single visceral and vascular smooth muscle cells of the rabbit. J Physiol. 1986;381:385–406. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner R, Perez GJ, Bonev AD, Eckman DM, Kosek JC, Wiler SW, Patterson AJ, Nelson MT, Aldrich RW. Vasoregulation by the β1 subunit of the calcium-activated potassium channel. Nature. 2000;407:870–876. doi: 10.1038/35038011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt E, Abel K, Krieger M, Palm D, Hoppe V, Hoppe J, Walter U. cAMP-dependent and cGMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation sites of the focal adhesion vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) in vitro and in intact human platelets. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14509–14517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bychkov R, Gollasch M, Ried C, Luft FC, Haller H. Regulation of spontaneous transient outward potassium currents in human coronary arteries. Circulation. 1997;95:503–510. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaytor AT, Taylor HJ, Griffith TM. Gap junction-dependent and -independent EDHF-type relaxations may involve smooth muscle cAMP accumulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1548–H1555. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00903.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng KT, Leung YK, Shen B, Kwok YC, Wong CO, Kwan HY, Man YB, Ma X, Huang Y, Yao XQ. CNGA2 channels mediate adenosine-induced Ca2+ influx in vascular endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:913–918. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.148338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton GD, Dewey WL. Protein kinase inhibitor peptide (PKI): a family of endogenous neuropeptides that modulate neuronal cAMP-dependent protein kinase function. Neuropeptides. 2006;40:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij J, Zwartkruis FJT, Verheijen MHG, Cool RH, Nijman SMB, Wittinghofer A, Bos JL. Epac is a Rap1 guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP. Nature. 1998;396:474–477. doi: 10.1038/24884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit C, Griffith TM. Connexins and gap junctions in the EDHF phenomenon and conducted vasomotor responses. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:897–914. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge-Kafka KL, Soughayer J, Pare GC, Michel JJC, Langeberg LK, Kapiloff MS, Scott JD. The protein kinase A anchoring protein mAKAP coordinates two integrated cAMP effector pathways. Nature. 2005;437:574–578. doi: 10.1038/nature03966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doebele RC, Schulze-Hoepfner FT, Hong J, Chlenski A, Zeitlin BD, Goel K, Gomes S, Liu Y, Abe MK, Nor JE, Lingen MW, Rosner MR. A novel interplay between Epac/Rap1 and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 5/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 (MEK5/ERK5) regulates thrombospondin to control angiogenesis. Blood. 2009;114:4592–4600. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-217042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EcklyMichel A, Martin V, Lugnier C. Involvement of cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases in cyclic AMP-mediated vasorelaxation. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;122:158–164. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Dora KA, Gardener MJ, Garland CJ, Weston AH. K+ is an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in rat arteries. Nature. 1998;396:269–272. doi: 10.1038/24388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Feletou M, Weston AH. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarising factors and associated pathways: a synopsis. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:863–879. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0817-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enserink JM, Christensen AE, de Rooij J, van Triest M, Schwede F, Genieser HG, Doskeland SO, Blank JL, Bos JL. A novel Epac-specific cAMP analogue demonstrates independent regulation of Rap1 and ERK. Nature Cell Biol. 2002;4:901–906. doi: 10.1038/ncb874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferro A, Coash M, Yamamoto T, Rob J, Ji Y, Queen L. Nitric oxide-dependent β2-adrenergic dilatation of rat aorta is mediated through activation of both protein kinase A and Akt. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:397–403. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furchgott RF, Zawadzki JV. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature. 1980;288:373–376. doi: 10.1038/288373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith TM, Chaytor AT, Taylor HJ, Giddings BD, Edwards DH. cAMP facilitates EDHF-type relaxations in conduit arteries by enhancing electrotonic conduction via gap junctions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6392–6397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092089799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayabuchi Y, Davies NW, Standen NB. Angiotensin II inhibits rat arterial K-ATP channels by inhibiting steady-state protein kinase A activity and activating protein kinase Ca. J Physiol. 2001;530:193–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0193l.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J, Doebele RC, Lingen MW, Quilliam LA, Tang W-J, Rosner MR. Anthrax edema toxin inhibits endothelial cell chemotaxis via Epac and Rap1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19781–19787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hothi SS, Gurung IS, Heathcote JC, Zhang YM, Booth SW, Skepper JN, Grace AA, Huang CLH. Epac activation, altered calcium homeostasis and ventricular arrhythmogenesis in the murine heart. Pflugers Arch. 2008;457:253–270. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0508-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggar JH, Porter VA, Lederer WJ, Nelson MT. Calcium sparks in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C235–C256. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.2.C235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggar JH, Stevenson AS, Nelson MT. Voltage dependence of Ca2+ sparks in intact cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C1755–C1761. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.6.C1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang GX, Joseph JW, Chepurny OG, Monaco M, Wheeler MB, Bos JL, Schwede F, Genieser HG, Holz GG. Epac-selective cAMP analog 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP as a stimulus for Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release and exocytosis in pancreatic beta-cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8279–8285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211682200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashima Y, Miki T, Shibasaki T, Ozaki N, Miyazaki M, Yano H, Seino S. Critical role of cAMP-GEFII.Rim2 complex in incretin-potentiated insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46046–46053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108378200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H, Springett GM, Mochizuki N, Toki S, Nakaya M, Matsuda M, Housman DE, Graybiel AM. A family of cAMP-binding proteins that directly activate Rap1. Science. 1998;282:2275–2279. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Han IS, Koh SD, Perrino BA. Roles of CaM kinase II and phospholamban in SNP-induced relaxation of murine gastric fundus smooth muscles. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C337–C347. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00397.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauban JRH, Lamont C, Balke CW, Wier WG. Adrenergic stimulation of rat resistance arteries affects Ca2+ sparks, Ca2+ waves, and Ca2+ oscillations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2399–H2405. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.5.H2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayati A, Levoin N, Paris H, N’Diaye M, Courtois A, Uriac P, Lagadic-Gossmann D, Fardel O, Le Ferrec E. Induction of intracellular calcium concentration by environmental benzo(α)pyrene involves a β2-adrenergic receptor/adenylyl cyclase/Epac-1/inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate pathway in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4041–4052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.319970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSherry IN, Spitaler MM, Takano H, Dora KA. Endothelial cell Ca2+ increases are independent of membrane potential in pressurized rat mesenteric arteries. Cell Calcium. 2005;38:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel E, Marcantoni A, Gastineau M, Birkedal R, Rochais F, Garnier A, Lompre AM, Vandecasteele G, Lezoualc’h F. cAMP-binding protein Epac induces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2005;97:1296–1304. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000194325.31359.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgado M, Cairrao E, Santos-Silva AJ, Verde I. Cyclic nucleotide-dependent relaxation pathways in vascular smooth muscle. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:247–266. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0815-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundina-Weilenmann C, Vittone L, Rinaldi G, Said M, De Cingolani GC, Mattiazzi A. Endoplasmic reticulum contribution to the relaxant effect of cGMP- and cAMP-elevating agents in feline aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1856–H1865. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.6.H1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray AJ. Pharmacological PKA inhibition: all may not be what it seems. Sci Signal. 2008;1:re4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.122re4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray KJ. Cyclic-AMP and mechanisms of vasodilation. Pharmacol Therapeut. 1990;47:329–345. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90060-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Cheng H, Rubart M, Santana LF, Bonev AD, Knot HJ, Lederer WJ. Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science. 1995;270:633–637. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Patlak JB, Worley JF, Standen NB. Calcium channels, potassium channels, and voltage dependence of arterial smooth-muscle tone. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:C3–C18. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.1.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1995;268:C799–C822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Droogmans G. Ion channels and their functional role in vascular endothelium. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1415–1459. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oestreich EA, Malik S, Goonasekera SA, Blaxall BC, Kelley GG, Dirksen RT, Smrcka AV. Epac and phospholipase regulate Ca2+ release in the heart by activation of protein kinase Cɛ and calcium-calmodulin kinase II. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1514–1522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806994200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki N, Shibasaki T, Kashima Y, Miki T, Takahashi K, Ueno H, Sunaga Y, Yano H, Matsuura Y, Iwanaga T, Takai Y, Seino S. cAMP-GEFII is a direct target of cAMP in regulated exocytosis. Nature Cell Biol. 2000;2:805–811. doi: 10.1038/35041046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnell E, Smith BO, Palmer TM, Terrin A, Zaccolo M, Yarwood SJ. Regulation of the inflammatory response of vascular endothelial cells by EPAC1. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166:434–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01808.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira L, Cheng H, Lao DH, Na L, van Oort RJ, Brown JH, Wehrens XHT, Chen J, Bers DM. Epac2 mediates cardiac β1-adrenergic-dependent sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak and arrhythmia. Circulation. 2013;127:913–922. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.12.148619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira L, Metrich M, Fernandez-Velasco M, Lucas A, Leroy J, Perrier R, Morel E, Fischmeister R, Richard S, Benitah JP, Lezoualc’h F, Gomez AM. The cAMP binding protein Epac modulates Ca2+ sparks by a Ca2+/calmodulin kinase signalling pathway in rat cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 2007;583:685–694. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.133066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira L, Ruiz-Hurtado G, Morel E, Laurent AC, Metrich M, Dominguez-Rodriguez A, Lauton-Santos S, Lucas A, Benitah JP, Bers DM, Lezoualc’h F, Gomez AM. Epac enhances excitation–transcription coupling in cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluger S, Faulhaber J, Furstenau M, Lohn M, Waldschutz R, Gollasch M, Haller H, Luft FC, Ehmke H, Pongs O. Mice with disrupted BK channel β1 subunit gene feature abnormal Ca2+ spark/STOC coupling and elevated blood pressure. Circ Res. 2000;87:E53–E60. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.11.e53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter VA, Bonev AD, Knot HJ, Heppner TJ, Stevenson AS, Kleppisch T, Lederer WJ, Nelson MT. Frequency modulation of Ca2+ sparks is involved in regulation of arterial diameter by cyclic nucleotides. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C1346–C1355. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.5.C1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucovsky V, Gordienko DV, Bolton TB. Effect of nitric oxide donors and noradrenaline on Ca2+ release sites and global intracellular Ca2+ in myocytes from guinea-pig small mesenteric arteries. J Physiol. 2002;539:25–39. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves GI, Kamishima T, Davies LM, Quayle JM, Dart C. Exchange protein activated by cAMP (Epac) mediates cAMP-dependent but protein kinase A-insensitive modulation of vascular ATP-sensitive potassium channels. J Physiol. 2009;587:3639–3650. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.173534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscioni SS, Kistemaker LEM, Menzen MH, Elzinga CRS, Gosens R, Halayko AJ, Meurs H, Schmidt M. PKA and Epac cooperate to augment bradykinin-induced interleukin-8 release from human airway smooth muscle cells. Resp Res. 2009;10:88. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscioni SS, Maarsingh H, Elzinga CRS, Schuur J, Menzen M, Halayko AJ, Meurs H, Schmidt M. Epac as a novel effector of airway smooth muscle relaxation. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1551–1563. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinthone S, Tyagi M, Gerthoffer WT. Small heat shock proteins in smooth muscle. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;119:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson LJ, Leyland ML, Dart C. Direct interaction between the actin-binding protein filamin-A and the inwardly rectifying potassium channel, Kir2.1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41988–41997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307479200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandow SL, Neylon CB, Chen MX, Garland CJ. Spatial separation of endothelial small- and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (K–Ca) and connexins: possible relationship to vasodilator function. J Anat. 2006;209:689–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00647.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandow SL, Tare M, Coleman HA, Hill CE, Parkington HC. Involvement of myoendothelial gap junctions in the actions of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Circ Res. 2002;90:1108–1113. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000019756.88731.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M, Evellin S, Weernink PAO, vom Dorp F, Rehmann H, Lomasney JW, Jakobs KH. A new phospholipase-C – calcium signalling pathway mediated by cyclic AMP and a Rap GTPase. Nature Cell Biol. 2001;3:1020–1024. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serban DN, Nilius B, Vanhoutte PM. The endothelial saga: the past, the present, the future. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:787–792. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0805-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen B, Cheng KT, Leung YK, Kwok YC, Kwan HY, Wong CO, Chen ZY, Huang Y, Yao XQ. Epinephrine-induced Ca2+ influx in vascular endothelial cells is mediated by CNGA2 channels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45:437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolenski A, Bachmann C, Reinhard K, Honig-Liedl P, Jarchau T, Hoschuetzky H, Walter U. Analysis and regulation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein serine 239 phosphorylation in vitro and in intact cells using a phosphospecific monoclonal antibody. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20029–20035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snead MD, Papapetropoulos A, Carrier GO, Catravas JD. Isolation and culture of endothelial cells from the mesenteric vascular bed. Methods Cell Sci. 1995;17:57–262. [Google Scholar]

- Stankevicius E, Lopez-Valverde V, Rivera L, D Hughes A, Mulvany MJ, Simonsen U. Combination of Ca2+-activated K+ channel blockers inhibits acetylcholine-evoked nitric oxide release in rat superior mesenteric artery. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149:560–572. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhanova IF, Kozhevnikova LM, Popov EG, Podmareva ON, Avdonin PV. Activators of Epac proteins induce relaxation of isolated rat aorta. Dokl Biol Sci. 2006;411:441–444. doi: 10.1134/s0012496606060044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboi T, Xavier GD, Holz GG, Jouaville LS, Thomas AP, Rutter GA. Glucagon-like peptide-1 mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ and stimulates mitochondrial ATP synthesis in pancreatic MIN6 beta-cells. Biochem J. 2003;369:287–299. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Triest M, De Rooij J, Bos JL. Measurement of GTP-bound Ras-like GTPases by activation-specific probes. Methods Enzymol. 2001;333:343–348. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)33068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vliem MJ, Ponsioen B, Schwede F, Pannekoek WJ, Riedl J, Kooistra MRH, Jalink K, Genieser HG, Bos JL, Rehmann H. 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP-AM: an improved Epac-selective cAMP analogue. Chembiochem. 2008;9:2052–2054. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R, Bottrill FE, Siau D, Hiley CR. Protein kinase A-dependent and -independent effects of isoproterenol in rat isolated mesenteric artery: Interactions with levcromakalim. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:917–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodrum DA, Brophy CM, Wingard CJ, Beall A, Rasmussen H. Phosphorylation events associated with cyclic nucleotide-dependent inhibition of smooth muscle contraction. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H931–H939. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.3.H931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama U, Minamisawa S, Quan H, Akaike T, Jin MH, Otsu K, Ulucan C, Wang X, Baljinnyam E, Takaoka M, Sata M, Ishikawa Y. Epac1 is upregulated during neointima formation and promotes vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H1547–H1555. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01317.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng YM, Wang QS, Liu QH, Rathore R, Yadav V, Wang YX. Heterogeneous gene expression and functional activity of ryanodine receptors in resistance and conduit pulmonary as well as mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells. J Vasc Res. 2008;45:469–479. doi: 10.1159/000127438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieba BJ, Artamonov MV, Jin L, Momotani K, Ho R, Franke AS, Neppl RL, Stevenson AS, Khromov AS, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Somlyo AV. The cAMP-responsive Rap1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor, Epac, induces smooth muscle relaxation by down-regulation of RhoA activity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:16681–16692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.205062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]