Abstract

Context

Large randomized trials have previously shown that high-dose micronutrient supplementation can increase CD4 counts and reduce human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease progression and mortality among individuals not receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART); however, the safety and efficacy of such supplementation has not been established in the context of HAART.

Objective

To test the hypothesis that high-dose multivitamin supplementation vs standard-dose multivitamin supplementation decreases the risk of HIV disease progression or death and improves immunological, virological, and nutritional parameters in patients with HIV initiating HAART.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of high-dose vs standard-dose multivitamin supplementation for 24 months in 3418 patients with HIV initiating HAART between November 2006 and November 2008 in 7 clinics in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Intervention

The provision of daily oral supplements of vitamin B complex, vitamin C, and vitamin E at high levels or standard levels of the recommended dietary allowance.

Main Outcome Measure

The composite of HIV disease progression or death from any cause.

Results

The study was stopped early in March 2009 because of evidence of increased levels of alanine transaminase (ALT) in patients receiving the high-dose multivitamin supplement. At the time of stopping, 3418 patients were enrolled (median follow-up, 15 months), and there were 2374 HIV disease progression events and 453 observed deaths (2460 total combined events). Compared with standard-dose multivitamin supplementation, high-dose supplementation did not reduce the risk of HIV disease progression or death. The absolute risk of HIV progression or death was 72% in the high-dose group vs 72% in the standard-dose group (risk ratio [RR], 1.00; 95% CI, 0.96–1.04). High-dose supplementation had no effect on CD4 count, plasma viral load, body mass index, or hemoglobin level concentration, but increased the risk of ALT elevations (1239 events per 1215 person-years vs 879 events per 1236 person-years; RR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.11–1.87) vs standard-dose supplementation.

Conclusion

In adults receiving HAART, use of high-dose multivitamin supplements compared with standard-dose multivitamin supplements did not result in a decrease in HIV disease progression or death but may have resulted in an increase in ALT levels.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00383669

During the last 15 years, the provision of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has significantly decreased morbidity and mortality associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1–3 Despite the substantial health benefits resulting from HAART, there are certain limitations to its efficacy—immune reconstitution may not be complete or sustained and the risk of opportunistic infection and death can remain high.4–6 In addition, antiretro-viral therapy (ART) is associated with toxic adverse effects contributing to increased morbidity and decreased quality of life.7

To maximize the benefits of HAART, the provision of adjuvant treatments may be considered. Multivitamins are key factors in maintaining immune function and neutralizing oxidative stress8,9 and could play an important role in reducing morbidity associated with HIV disease and treatment. Among individuals not receiving HAART, 2 large randomized trials10,11 have demonstrated that high doses of B-complex vitamins, vitamin C, and vitamin E with and without other micronutrients reduced the risk of morbidity and mortality due to HIV. Among patients receiving HAART, the evidence is mixed. Several small randomized studies12–15 suggest a potential benefit of high-dose vitamin supplementation on immunological and virological end points. However, limited by small samples and short follow-up, these studies remain insufficient to determine whether prolonged high-dose multivitamin supplementation in the context of HAART is safe and can improve clinical outcomes.

We have previously shown that high-dose multivitamin supplementation compared with placebo reduced the risk of HIV disease progression and increased CD4 counts among women infected with HIV not receiving HAART.10 To test the hypothesis that high-dose multivitamin supplementation compared with standard-dose supplementation decreases the risk of HIV disease progression or death and improves immunological, virological, and nutritional parameters in patients infected with HIV receiving HAART, we conducted a double-blind, randomized controlled trial of multivitamin supplementation (including vitamin B complex, vitamin C, and vitamin E) in adults initiating ART in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. A single level of the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) was provided as the comparator regimen, rather than placebo, to increase the generalizability of our findings to patients in developed and developing countries where a standard RDA multivitamin supplement may be consumed.

METHODS

Study Design

The Trial of Vitamins and HAART in HIV Disease Progression was a double-blind, randomized controlled trial involving men and women with HIV initiating HAART in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Participants were recruited between November 2006 and November 2008 and were randomly assigned to receive daily oral supplements of vitamin B complex, vitamin C, and vitamin E at high or standard levels of the RDA16,17 for a minimum of 24 months. The primary goal was to determine whether high-dose vs standard-dose daily oral supplements of vitamin B complex, vitamin C, and vitamin E administered to individuals infected with HIV initiating HAART reduced the risk of HIV disease progression or death. All patients provided written informed consent to participate. Patients participating in this study were not included in any other research study.

The study included 3418 patients presenting to 7 clinics providing HAART under the Tanzania National AIDS Control Program with the support of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief program and in collaboration with the Harvard School of Public Health, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, and the City of Dar es Salaam Regional Office of Health. At the time of the study, all patients with World Health Organization (WHO) clinical stage IV disease or CD4 count of less than 200/μL, or with WHO clinical stage III disease and CD4 count of less than 350/μL, were initiated to receive HAART.18 First-line drug combinations included stavudine, lamivudine, nevirapine, zidovudine, and efavirenz. As part of standard care, all patients receiving HAART attended clinic visits with nurse counselors and collected medications on a monthly basis. Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis was provided when CD4 counts were less than 200/μL and treatment for all opportunistic infections was provided according to the national and WHO guidelines. HAART regimens were changed with evidence of toxicity or treatment failure.19

Individuals were eligible for the study if they were aged 18 years or older, infected with HIV, initiating ART at the time of study enrollment (within 2 weeks), and intending to stay in the city of Dar es Salaam for at least 2 years. Women who were pregnant or lactating were excluded from the study and were provided with high-dose multi-vitamin supplements given earlier findings that high-dose multivitamin supplements reduced the risk of fetal loss, low birth weight, and prematurity among pregnant women not receiving HAART.20

Intervention and Randomization

Eligible participants were individually randomized at each study site to receive daily oral supplements of vitamin B complex, vitamin C, and vitamin E at high or standard levels of the RDA (Table 1). The high-dose supplements provided 2 to 21 times the RDA for the B vitamins, 2 times the RDA for vitamin E, and 6 times the RDA for vitamin C. These doses were similar to those used in our previous placebo-controlled randomized trial, in which multivitamins reduced the risk of HIV disease progression or death among women.10 They were chosen on the basis of evidence from previous observational studies, which suggested that individuals infected with HIV require higher dietary intakes of micronutrients to achieve normal serum concentrations.21,22 Vitamin B complex, vitamin C, and vitamin E at the single level of the RDA were provided as the comparator regimen, rather than placebo. This choice of comparator regimen was made to increase the generalizability of our findings to patients in developed and developing countries where a standard RDA multivitamin supplement may be consumed.23

Table 1.

Daily Multivitamin Content of Study Regimens

| Vitamin | Standard-Dose Regimen | High-Dose Regimen |

|---|---|---|

| Thiamin | 1.2 mg | 20 mg |

| Riboflavin | 1.2 mg | 20 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 1.3 mg | 25 mg |

| Niacin | 15 mg | 100 mg |

| Vitamin B12 | 2.4 μg | 50 μg |

| Folic acid | 0.4 mg | 0.8 mg |

| Vitamin C | 80 mg | 500 mg |

| Vitamin E | 15 mg | 30 mg |

Allocation was performed according to a computer-generated randomization sequence generated by a statistician for the data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) using blocks of size 20. At enrollment, research staff assigned each eligible person to the next numbered bottle at that site. At each subsequent visit, study supplements were dispensed in identically coded bottles labeled with the patient’s study identification number prepared by independent pharmacists who had no contact with the patients or study team. All participants and research staff were blinded to the intervention allocation. The 2 types of study supplements were manufactured as tablets by Tishcon Corporation and were indistinguishable from one another in appearance and taste.

Enrollment and Follow-up

Patients initiating HAART at the 7 study clinics in Dar es Salaam were referred to research staff for screening and recruitment. At the initial recruitment visit, HIV status was confirmed using 2 sequential enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, with discordant results confirmed by Western blot test. Study procedures and the schedule of follow-up visits were explained at the same visit. All participants who provided written informed consent to participate were asked to come back 1 week later, when research staff confirmed eligibility and performed randomization and enrollment.

At enrollment, a full clinical examination was conducted and a standardized questionnaire was administered to collect information on sociodemographic information, including age, education, and socioeconomic and marital status. At enrollment and subsequent monthly visits, study physicians performed a complete physical examination and assessed HIV disease stage according to the WHO staging criteria. Clinical algorithms based on clinical examination, medical history, and available diagnostics were developed to assist physicians in the diagnosis of all HIV disease staging events (suspected or confirmed). Training on these clinical algorithms was conducted every 6 months. At enrollment and subsequent monthly visits, study nurses recorded the occurrence of any illness in the previous month and performed anthropometric measurements (height at enrollment; weight; and waist, hip, mid-thigh, and mid-arm circumferences at enrollment and monthly visits) according to standard techniques. Adherence was assessed by study nurses at each visit by pill count and direct questioning of supplement use.

Determination of absolute count of T cell subsets (FACSCalibur flow cytometer, Becton Dickinson), complete blood cell count (AcT5 Diff AL analyzer, Beckman Coulter), and alanine transaminase (ALT; Cobas Integra 400 Plus analyzer, Roche Diagnostics Systems) was conducted every 4 months. Plasma viral load assessment, not a primary end point or part of standard of care in this setting due to the high cost, was to be performed at enrollment and every 4 months thereafter, subject to the availability of reagents (Cobas Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor test version 1.5, Roche Diagnostics Systems). All venous blood samples were collected by trained phlebotomists using EDTA vacutainer tubes. EDTA whole blood was used for determination of absolute T cell subsets and complete blood cell counts without processing. Plasma sample was separated from whole blood within 30 hours of collection by centrifugation at 1600g for 20 minutes at room temperature (18°C–25°C). Plasma specimens were stored at −70°C until the time for batch testing of viral load tests. Serum sample was collected using plain vacutainer tubes and separated within the same day of collection by centrifugation at 1600g for 10 minutes and stored up to 7 days at 2°C to 8°C for ALT analyses. Screening for hepatitis B surface antigen and antibodies to hepatitis C was conducted at enrollment and as indicated thereafter using rapid test strips (ACON Laboratories Inc). Dietary intake, including alcohol intake, was measured with the use of semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire at enrollment and every 12 months thereafter.

Home visits were made in the event that a scheduled clinic visit was missed, and neighbors and relatives were contacted to obtain information on the survival status of those who had left Dar es Salaam. For participants who died, data to determine cause of death were collected using medical record review and standard verbal autopsy techniques, including open-ended and closed-ended questions on the clinical condition and treatments received in the period before death. The verbal autopsy data were coded by 2 senior HIV clinicians who established cause of death by consensus. Similar verbal autopsy procedures (eg, clinician coding of structured interviews with relatives to identify cause of death) have been recommended by the WHO24 and validated for diagnosing HIV-related mortality.25 Participants were followed up until the date of death, loss to follow-up, or study closure, whichever occurred first.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was the composite of HIV disease progression or death from any cause. The study was powered to detect a treatment effect for this outcome alone. HIV disease progression events comprised a new or recurrent episode of any of the following: pulmonary tuberculosis (TB), pneumonia, Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, chronic diarrhea, cryptococcal meningitis, cytomegalovirus retinitis, TB meningitis, mucocutaneous herpes simplex virus, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, HIV encephalopathy, histoplasmosis, coccidiomycosis, esophageal candidiasis, atypical mycobacterial infection, extrapulmonary TB, lymphoma, and Kaposi sarcoma. These end points are standard HIV disease staging end points as identified by the WHO.26 Secondary outcomes included AIDS-related death (defined as death due to P jiroveci pneumonia, pulmonary TB, extrapulmonary TB, Kaposi sarcoma, wasting, HIV/AIDS with opportunistic infection, or invasive cervical carcinoma27) and changes in CD4 count, plasma viral load, body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), and hemoglobin level concentrations. We also evaluated other clinical and laboratory complications that were reported during the month before each study visit or diagnosed at the study visit as secondary outcomes. These included fatigue, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, severe anemia (hemoglobin level <8.5 g/dL), skin rashes or lesions, peripheral neuropathy, genital discharge or ulcers, and increased levels of ALT (above the upper level of normal: ALT >40 IU/L and 5 times the upper level of normal: ALT >200 IU/L).

Sample Size

A sample size of 3000 patients was calculated for the study to have more than 90% power to detect a 25% decrease in the risk of the primary end point, HIV disease progression or death from any cause, assuming a 2-sided type 1 error of .05. This calculation was based on an assumed incidence of HIV disease progression or death of 10 per 100 person-years, as reported in similar populations in sub-Saharan Africa while receiving ART,28,29 and allowed for a 20% cumulative loss to follow-up rate over a mean 3-year study duration. The assumed 25% treatment effect is consistent with previous studies, in which high-dose multivitamin supplements compared with placebo resulted in a 29% reduction in risk of progression to WHO stage IV or AIDS-related death (relative risk, 0.71; P =.0410) and a 47% reduction in mortality (hazard ratio, 0.53; P = .1011).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were based on the intention-to-treat principle and comprised all randomized patients who began the assigned treatment regimen at the time of HAART initiation. We assessed baseline characteristics for clinically relevant differences by treatment group using the χ2 test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. We used the χ2 test to assess the statistical significance of any difference observed in the proportion of patients who experienced HIV disease progression or death from any cause, death from any cause, or AIDS-related death by treatment group.

We used generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with an exchangeable correlation matrix and robust standard errors to assess the statistical significance of any difference observed between baseline and postrandomization levels of CD4 count, plasma viral load, BMI, and hemoglobin level concentrations, and the occurrence of clinical complications by intervention group.30 Continuous end points were analyzed using the identity link and Gaussian variance function, with P values estimated from a GEE for parallel-group design.30 Binary end points were analyzed using a robust regression approach with the log link function and a working Poisson variance function. All available measurements were included in the GEE analyses. In post hoc analyses for all end points, we examined whether the effects of the high-dose supplement were modified by the following baseline characteristics: sex, BMI (<16 vs ≥16), CD4 count (<100/ μL, 100–199/μL, or ≥200/μL), hemoglobin level (<8.5 g/dL vs ≥8.5 g/dL), and HAART regimen.

To assess the statistical significance of each interaction, we used the Wald test for risk-ratio homogeneity in the risk analyses and the score test in the GEE analyses. All P values were 2-sided with P <.05 considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc). No adjustment for multiple comparisons was made because we only considered a single primary end point. All other analyses included are secondary end points best regarded as exploratory; any significant findings for these end points would need to be confirmed in future studies.

Data and Safety Monitoring

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Harvard School of Public Health, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Tanzania Food and Drugs Authority, and National Institute of Medical Research. An independent DSMB reviewed study progress and directed interim analyses for assessing treatment effects in terms of safety and efficacy every 6 months during the trial. Peto stopping guidelines were adopted, with cutoff P values of .05 for safety end points and .001 for the primary end point. Preliminary results of an interim analysis indicated an increased risk of death with high-dose supplementation, and the DSMB recommended all patients receive standard-dose supplements between November 30, 2007, and March 16, 2008. In March 2008, based on further analyses suggesting that the increased risk of death due to the high-dose multivitamin supplementation was restricted to severely malnourished patients, the DSMB recommended that patients with a BMI of less than 16 be excluded from enrollment and enrolled patients be switched to standard-dose supplementation for any period during which their BMI was less than 16.

According to the intention-to-treat principle, all person-time and events recorded during follow-up were attributed to the assigned treatment group. The study was stopped early in March 2009 (29 months after study initiation) on the recommendation of the DSMB because of evidence of increased levels of ALT, a proxy for liver function, among patients receiving the high-dose multivitamin supplement. At the time of stopping, 3418 patients had been enrolled with a median 15 months of follow-up for the primary end point. All patients enrolled in the study between November 30, 2007, and March 16, 2008, received open-label multivitamin supplementation as per the DSMB recommendation. These patients (n = 612) therefore did not fulfill the eligibility criteria of the study protocol. To account for these enrolled individuals, an increase in the study sample size (rounded to 4000 patients) was requested and approved by the institutional review board in April 2008. Therefore, at the time of early stopping in March 2009, 3418 patients had been enrolled according to the study protocol, which comprised the study population. The power to detect a 10% reduction in the risk of HIV disease progression or death at the time of early study termination was more than 90% (2-sided type 1 error = .05).

RESULTS

Study Population

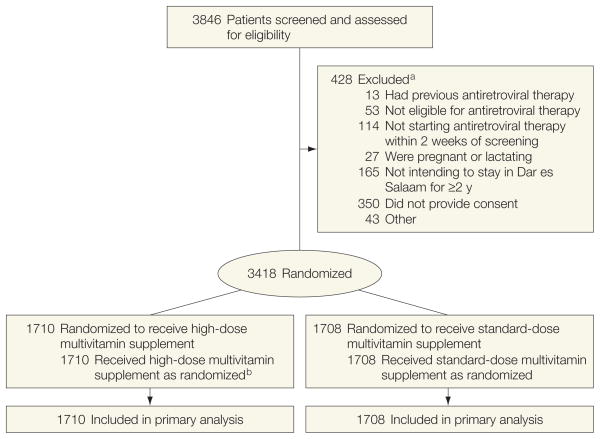

The flow of participants through the trial is shown in the Figure. A total of 3418 patients were randomized between November 2006 and November 2008 to receive either daily oral supplementation at the high dose or standard dose. The study was stopped early in March 2009, with a median length of follow-up of 15 months (interquartile range, 6–19) in both the standard-dose and high-dose groups. Treatment groups were comparable with respect to sex, education, clinical characteristics, and HAART regimen (Table 2). Adherence, calculated as the number of tablets absent from the returned bottles divided by the total number the individual should have taken, was high and did not vary by group (90% for the high-dose group vs 90% for the standard-dose group, P = .74).

Figure. Study Flow of Patients.

All 3418 patients randomized were included in the primary analysis.

a Reasons for exclusion do not sum to 428 because patients could be excluded for more than 1 reason.

b As recommended by the data and safety monitoring board, all patients received standard-dose multivitamin supplements between November 30, 2007, and March 16, 2008.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Populationa

| Characteristics | Standard-Dose Regimen (n = 1708) | High-Dose Regimen (n = 1710) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 38.4 (8.6) | 37.8 (8.6) |

|

| ||

| Female sex | 1181 (69.2) | 1141 (66.7) |

|

| ||

| Highest attained education, primary | 766 (60.7) | 769 (62.1) |

|

| ||

| BMI | ||

| Mean (SD) | 21.1 (4.1) | 21.0 (4.2) |

|

| ||

| <16 | 111 (6.5) | 116 (6.9) |

|

| ||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | ||

| Mean (SD) | 10.1 (2.1) | 10.2 (2.3) |

|

| ||

| <8.5 | 366 (22.5) | 352 (21.8) |

|

| ||

| CD4 count/μL | ||

| Mean (SD) | 137.4 (104.3) | 129.8 (97.1) |

|

| ||

| <100 | 674 (40.9) | 702 (43.0) |

|

| ||

| 100–199 | 611 (37.1) | 617 (37.8) |

|

| ||

| ≥200 | 362 (22.0) | 313 (19.2) |

|

| ||

| Viral load, mean (SD), log copies/mL | 5.2 (0.7) | 5.2 (0.7) |

|

| ||

| ALT, mean (SD), IU/L | 24.7 (22.0) | 24.6 (22.7) |

|

| ||

| HAART regimen | ||

| Stavudine, lamivudine, and nevirapine | 1013 (59.3) | 970 (56.7) |

|

| ||

| Stavudine, lamivudine, and efavirenz | 171 (10.0) | 179 (10.5) |

|

| ||

| Zidovudine, lamivudine, and nevirapine | 130 (7.6) | 147 (8.6) |

|

| ||

| Zidovudine, lamivudine, and efavirenz | 394 (23.1) | 414 (24.2) |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Data are No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. Because of missing values, sums may be less than the totals.

HIV Disease Progression and Mortality

A total of 2374 HIV disease progression events and 453 deaths were observed (n=2460 for combined end point of HIV disease progression or death from any cause). HIV disease progression or death occurred in 1231 of 1710 patients (72.0%) in the high-dose group and in 1229 of 1708 patients (72.0%) in the standard-dose group. Compared with the standard-dose supplementation, high-dose supplementation had no effect on the overall risk of HIV disease progression or death (risk ratio [RR], 1.00; 95% CI, 0.96–1.04) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of High-Dose Multivitamin Supplementation on HIV Disease Progression and Mortality

| Outcome | No. (%) of Patients

|

High-Dose Multivitamins, RR (95% CI) | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard-Dose Regimen (n = 1708) | High-Dose Regimen (n = 1710) | |||

| HIV disease progression or death from any cause | ||||

|

| ||||

| All patients | 1229 (72.0) | 1231 (72.0) | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | .98 |

|

| ||||

| By baseline BMIb | ||||

| ≥16 | 1127 (71.1) | 1120 (71.1) | 1.00 (0.96–1.05) | .99 |

|

| ||||

| <16 | 92 (82.9) | 99 (85.3) | 1.03 (0.92–1.15) | .61 |

|

| ||||

| Death from any cause | ||||

| All patients | 220 (12.9) | 233 (13.6) | 1.06 (0.89–1.26) | .52 |

|

| ||||

| By baseline BMIb | ||||

| ≥16 | 187 (11.8) | 183 (11.6) | 0.98 (0.81–1.19) | .88 |

|

| ||||

| <16 | 31 (27.9) | 44 (37.9) | 1.36 (0.93–1.98) | .11 |

|

| ||||

| AIDS-related death | ||||

| All patients | 64 (3.8) | 73 (4.3) | 1.14 (0.82–1.58) | .44 |

|

| ||||

| By baseline BMIb | ||||

| ≥16 | 54 (3.4) | 57 (3.6) | 1.06 (0.74–1.53) | .75 |

|

| ||||

| <16 | 8 (7.2) | 14 (12.1) | 1.67 (0.73–3.84) | .22 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; RR, risk ratio.

By χ2 test.

P values were calculated by test for interaction from the Wald test for risk-ratio homogeneity. Test for interaction by baseline BMI, P=.63 for HIV disease progression or death from any cause; P=.14 for death from any cause; and P=.32 for AIDS-related death.

Among the 453 deaths observed, the most frequent causes of death included pneumonia (n = 65), P jiroveci pneumonia (n = 21), pulmonary TB (n = 24), vomiting (n = 30), diarrhea (n = 42), meningitis (n = 19), malaria (n = 25), severe anemia with congestive heart failure (n = 24), and HIV/ AIDS with opportunistic infections (n=89) (eTable, available at http://www.jama.com). There was no difference in death from any cause (13.6% vs 12.9%; RR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.89–1.26) or AIDS-related death (4.3% vs 3.8%; RR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.82–1.58) by treatment group. There was no appreciable difference between groups in the risk of HIV progression or death from any cause, death from any cause, or AIDS-related death by sex, baseline CD4 count, hemoglobin level, or HAART regimen, but there was a statistically nonsignificant difference in the risk of death by baseline BMI (P for interaction=.14). Among patients with BMI of at least 16, we found no effect of high-dose multivitamin supplementation compared with standard-dose supplementation on the risk of death (11.6% vs 11.8%; RR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.81–1.19; P = .88). Among patients with BMI of less than 16 at baseline, for high-dose multivitamin supplementation compared with standard-dose supplementation, the risk of death was elevated but the result did not reach statistical significance (44/116 [37.9%] vs 31/111 [27.9%]; RR, 1.36; 95% CI, 0.93–1.98; P = .11). The most frequent causes of death among patients with BMI of less than 16 at baseline included pneumonia (n = 7), pulmonary TB (n=4), vomiting (n=5), diarrhea (n = 14), malaria (n = 5), severe anemia with congestive heart failure (n = 5), and HIV/AIDS with opportunistic infections (n = 18).

CD4 Count, Plasma Viral Load, BMI, and Hemoglobin Level Concentrations

The mean difference in CD4 count (mean difference, −6/μL; 95% CI, −16 to 4/μL) and plasma viral load (mean difference, −0.1 log copies/mL; 95% CI, −0.4 to 0.3 log copies/mL) over time did not differ between groups (Table 4). No significant differences were noted between groups in BMI or hemoglobin level concentrations.

Table 4.

Effect of High-Dose Multivitamin Supplementation on Clinical and Laboratory Markers of Health Statusa

| Laboratory Outcomes | Standard-Dose Regimen (n = 1708)

|

High-Dose Regimen (n = 1710)

|

Mean Difference (95% CI)b | P Valuec | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients (Measurements) | Mean (SD) | No. of Patients (Measurements) | Mean (SD) | |||

| CD4 count/μL | 1394 (5221) | 324 (163) | 1374 (5215) | 312 (159) | −6 (−16 to 4) | .18 |

|

| ||||||

| Plasma viral load, log copies/mL | 109 (140) | 3.7 (1.2) | 127 (166) | 3.5 (1.2) | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.3) | .66 |

|

| ||||||

| BMI | 1602 (13 927) | 22.4 (5.7) | 1593 (13 655) | 22.2 (4.3) | 0.0 (−0.2 to 0.1) | .42 |

|

| ||||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 1467 (5844) | 11.0 (1.9) | 1468 (5866) | 11.1 (1.9) | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0.0) | .26 |

|

| ||||||

| Clinical Outcomes | No. of Patients (Measurements) | Events per Person-Yearsd | No. of Patients (Measurements) | Events per Person-Yearsd | Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI)e | P Valuee |

|

| ||||||

| Fatigue | 1581 (24 392) | 1175 per 1854 | 1596 (24 196) | 1115 per 1835 | 0.95 (0.85 to 1.07) | .43 |

|

| ||||||

| Nausea or vomiting | 1581 (24 392) | 744 per 1854 | 1596 (24 196) | 729 per 1853 | 0.99 (0.87 to 1.14) | .90 |

|

| ||||||

| Diarrhea | 1581 (24 392) | 709 per 1854 | 1596 (24 196) | 657 per 1835 | 0.92 (0.80 to 1.07) | .29 |

|

| ||||||

| Severe anemia | 1530 (6057) | 612 per 1616 | 1544 (6112) | 581 per 1615 | 0.82 (0.60 to 1.12) | .22 |

|

| ||||||

| Rashes or lesions | 1581 (24 392) | 3529 per 1854 | 1596 (24 196) | 3446 per 1835 | 1.00 (0.91 to 1.10) | .98 |

|

| ||||||

| Neuropathy | 1255 (19 129) | 1365 per 1450 | 1310 (19 802) | 1213 per 1503 | 0.81 (0.70 to 0.94) | .004 |

|

| ||||||

| Genital discharge or sores | 1581 (24 392) | 305 per 1854 | 1596 (24 196) | 293 per 1835 | 0.92 (0.75 to 1.13) | .44 |

|

| ||||||

| ALT >40 IU/L | 1468 (5383) | 879 per 1236 | 1453 (5387) | 1239 per 1215 | 1.44 (1.11 to 1.87) | .006 |

|

| ||||||

| ALT >200 IU/L | 1468 (5383) | 25 per 1236 | 1453 (5387) | 41 per 1215 | 1.12 (0.50 to 2.50) | .79 |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Venous blood samples were collected for determination of CD4 count and complete blood cell count every 4 months. Anthropometry and the incidence of clinical complications were assessed on a monthly basis. Viral load was to be assessed at enrollment and every 4 months thereafter, subject to the availability of reagents. The number of patients and available measurements contributing to generalized estimating equation (GEE) analysis in parentheses are shown. Data are the means (SDs) of measurements during follow-up. Severe anemia is defined as hemoglobin level of less than 8.5 g/dL.

Data are the mean difference between the high-dose group and the standard-dose group. The mean differences (95% CIs) are from GEEs using the identity link and Gaussian variance function with the difference between baseline and postrandomization measures as the outcome and study regimen as the exposure.

From a GEE for parallel-group designs.30

Number of events is based on the occurrence of clinical and laboratory complications reported during the month before each study visit or diagnosed at the study visit over follow-up time. Person-years is based on the follow-up time contributed by each patient from enrollment until the last study visit.

The incidence rate ratios, 95% CIs, and corresponding P values are from GEEs using the log link and Poisson variance function.

Clinical and Laboratory Complications

Table 4 summarizes the occurrence of clinical complications during follow-up. The occurrence of fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, and severe anemia were similar across treatment groups. Compared with standard-dose supplementation, high-dose supplementation reduced the risk of neuropathy, which was reported in 42% of patients (1213 events per 1503 person-years vs 1365 events per 1450 person-years; incidence rate ratio [IRR], 0.81; 95% CI, 0.70–0.94). The ALT above the upper level of normal (ALT >40 IU/L) and the ALT 5 times the upper level of normal (ALT >200 IU/L) were reported in 38% (n = 1118) and 2% (n = 54) of patients with ALT measurements, respectively. The incidence of ALT above the upper level of normal was significantly greater among patients in the high-dose supplementation group than the standard-dose supplementation group (1239 events per 1215 person-years vs 879 events per 1236 person-years; IRR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.11–1.87).

COMMENT

In light of increasing access to HAART worldwide, it is essential to document the safety and effectiveness of prolonged multivitamin supplementation in patients receiving combination therapy. In the first randomized trial to evaluate the effect of high-dose multi-vitamin supplementation on clinical outcomes in the context of HAART, we found that the provision of high-dose multivitamin supplementation from the initiation of HAART did not reduce the risk of HIV disease progression or death from any cause and had no effect on the secondary end points of CD4 count, plasma viral load, BMI, or hemoglobin level concentrations compared with standard-dose multivitamin supplementation. We found a nonstatistically significant risk of death with the high-dose multivitamin supplementation among severely malnourished patients in secondary analysis, and the study was stopped early due to an increase in the risk of ALT elevations with high-dose multivitamin supplementation.

High doses of multivitamins were considered in our study based on the rationale that individuals infected with HIV may require nutritional intakes at multiples of the RDA to achieve adequate nutrient status. Early observational studies have demonstrated a high prevalence of vitamin deficiencies among HIV-infected individuals reporting intakes at the RDA level21,22 and suggested that vitamin intakes at levels several times greater than the RDA may be necessary to slow the progression to AIDS or death.31–33 We previously reported that a high-dose regimen of vitamin B complex, vitamin C, and vitamin E administered to untreated women with HIV in early stages of HIV disease resulted in significant reductions in disease progression, and improved CD4 counts and several other important outcomes.10 In a study from Thailand among individuals infected with HIV, the majority of whom were not receiving HAART, high-dose multivitamin supplementation also reduced mortality among individuals with baseline CD4 count of less than 100/ μL.11 To our knowledge, there is no other evidence to suggest that high-dose multivitamin supplementation increases ALT levels among individuals with or without HIV.

We found that high-dose multivitamin supplementation provided no benefit to patients with HIV initiating HAART compared with standard-dose multivitamin supplementation. Previous evidence among patients receiving ART, although limited by small sample sizes and short follow-up, suggested that high-dose supplementation with vitamin E, or vitamins E and C, may provide some benefit by increasing lymphocyte viability12 or decreasing viral load15 and oxidative stress.13,34 In a small trial among patients with HIV receiving HAART in the United States, multiple micronutrient supplementation for 12 weeks also increased CD4 counts.14 It is possible that the inconsistency between this study and earlier work is in part due to the choice of comparator regimens, as the latter were all placebo-controlled. The existence of a threshold at the standard dose, beyond which there is no further benefit, would be consistent with the observation of significant benefit of high-dose vitamin supplementation when compared with placebo, but not when compared with a standard dose. The absence of comparison groups receiving placebo or other low doses of multivitamins in our study limits our ability to evaluate this hypothesis. We found that high-dose multivitamin supplementation reduced the risk of neuropathy, a common complication of HIV infection in this setting. The exact mechanism for this effect is unclear, though may be related to correction of vitamin E deficiency, which has been associated with peripheral neuropathy.35

Although the provision of high-dose vitamin supplements has been safe among patients infected with HIV not receiving HAART,10,11 safety cannot be presumed in the context of potent combination therapies due to potential negative interactions among nutrients and antiretroviral drugs.36 We found in our study that high-dose multivitamin supplementation from the time of HAART initiation increased the risk of ALT elevation above the upper level of normal and contributed to a nonstatistically significant risk of death among severely malnourished patients. Several studies have suggested that ART may cause an increase in levels of ALT,37–39 and the provision of antioxidants at the time of HAART initiation could be considered a plausible adjuvant treatment to reduce drug-related hepatotoxicity.

To the contrary, we observed a significant increase in levels of ALT associated with high-dose multivitamin supplementation. The exact mechanism of action for high-dose multivitamins to cause ALT elevation in the context of HAART is unknown but may be modified by specific drug regimens or other risk factors for ALT elevations (eg, heavy alcohol consumers or those patients infected with hepatitis B or C virus). Unfortunately, the very low prevalence of alcohol intake and hepatitis coinfection in this population limits further consideration of these factors herein. Overall, the ALT elevation of more than 200 IU/L was observed in a small proportion of patients and the relevance of an increased risk of ALT of more than 40 IU/L for clinical outcomes in the context of HIV infection remains unclear. Continued monitoring of ALT levels is recommended in future intervention studies among individuals infected with HIV and receiving HAART, and attention to the severity and duration of ALT elevation may help to differentiate between persistent and isolated increases in levels of ALT and to guide clinical concern.

Increased mortality after HAART initiation has been observed among patients with low BMI in several analyses from sub-Saharan Africa.40–42 Although the cause is likely multifactorial, it has been suggested that the metabolic abnormalities consistent with muscle depletion in HIV-associated wasting may lead to disturbances in the homeostasis of key nutrients when food intake increases with HAART initiation43; this phenomenon has been termed the “re-feeding syndrome.” It is conceivable that multivitamin regimens that are overly aggressive or poorly timed may propagate similar metabolic disturbances and contribute to poor clinical outcomes among patients who are severely malnourished.

The principle of appropriate timing in the provision of micronutrient supplementation has long been recognized in the treatment of severe acute malnutrition; iron, for example, is withheld during the initial or stabilization phase of nutritional rehabilitation, while potassium and magnesium are provided early in treatment to correct deficits.44 The timing of therapeutic interventions in the context of HIV and TB infection has similarly been shown to be important. A negative effect of early micronutrient supplementation during TB treatment in Mwanza, Tanzania, has been reported (multiple micronutrients provided in a daily biscuit for the first 2 months of TB treatment decreased weight gain among patients with HIV but had no effect among patients without HIV).45 More recently, early compared with later initiation of ART increased the risk of TB-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome but decreased the risk of death among individuals coinfected with HIV and TB.46,47 The metabolic pathways through which adverse effects may occur with supplementation soon after treatment initiation are currently not well described but warrant further consideration. The potential for multivitamin supplementation that follows a period of stabilization after ART initiation to be safe and efficacious should be considered in future studies.

Further investigation is required to understand how micronutrient supplements can be best positioned alongside antiretroviral drugs to reduce morbidity and mortality due to HIV. As different doses may have different effects, dose-finding trials with a placebo control are warranted to confirm the potential benefits of multivitamin supplementation on clinical outcomes, and to identify the lowest safe and effective dose in the context of HAART. Research from a variety of settings will be needed as the effect of specific micronutrient interventions, and thus the optimal dose, will likely depend on many factors, including background micronutrient intake and the prevalence of coinfection. To better understand the mechanisms of action underlying the adverse effect found herein, further investigation is recommended on the effect of micronutrients on plasma levels of antiretroviral drugs and specific immune parameters, including lymphocyte proliferation and Th-1 cytokine production. In addition, the use of supplementary foods, including ready-to-use foods and fortified blended flours, to deliver multiple micronutrients and energy is increasing within HIV care and treatment programs in sub-Saharan Africa.48,49 Nutritional support may increase treatment adherence50 and contribute to weight gain,51,52 but data are lacking on the clinical benefit of such interventions.53,54 The potential of providing multiple micronutrients with food to safely improve nutritional status and clinical outcomes of individuals with HIV warrants immediate consideration.

In conclusion, the provision of high-dose multivitamin supplementation from the initiation of HAART did not reduce the risk of HIV disease progression or mortality compared with standard-dose multivitamin supplements and had no effect on CD4 count, plasma viral load, or BMI. The adverse effect of high-dose multivitamins compared with standard-dose multivitamins to increase ALT level is a reason for concern, but the mechanism by which multivitamins resulted in this adverse effect is not well understood. In the absence of clear evidence of the benefit of high-dose micronutrient supplementation on morbidity and mortality in adults receiving HAART, it is prudent to follow current recommendations to promote and support adequate dietary intake of micronutrients at RDA levels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported by grant R01 HD32257 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Role of the Sponsor: The study sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

Online-Only Material: The eTable is available at http://www.jama.com.

Author Contributions: Dr Fawzi had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Mugusi, Aboud, Guerino, Fawzi.

Acquisition of data: Mugusi, Hawkins, Okuma, Aboud, Guerino, Fawzi.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Isanaka, Hawkins, Spiegelman, Okuma, Aboud, Guerino, Fawzi.

Drafting of the manuscript: Isanaka, Okuma.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Mugusi, Hawkins, Spiegelman, Okuma, Aboud, Guerino, Fawzi.

Statistical analysis: Isanaka, Spiegelman, Okuma.

Obtained funding: Fawzi.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Hawkins, Guerino, Fawzi.

Study supervision: Mugusi, Aboud, Guerino, Fawzi.

Additional Contributions: We thank all of the patients who contributed to this study. Susie Welty, MPH (Harvard School of Public Health, currently with University of California, San Francisco) and Jeremy C. Kane, MPH (Harvard School of Public Health, currently with Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health) provided supervision of the study implementation; and Ellen Hertzmark, MA (Harvard School of Public Health) provided support in data analysis. Ms Welty, Mr Kane, and Ms Hertzmark contributed to the study as employees of the Harvard School of Public Health and received no additional compensation for their contributions.

References

- 1.Autran B, Carcelain G, Li TS, et al. Positive effects of combined antiretroviral therapy on CD4+T cell homeostasis and function in advanced HIV disease. Science. 1997;277(5322):112–116. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fairall LR, Bachmann MO, Louwagie GM, et al. Effectiveness of antiretroviral treatment in a South African program: a cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):86–93. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palella FJ, Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, et al. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(13):853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lederman HM, Williams PL, Wu JW, et al. AIDS Clinical Trials Group 889 Study Team. Incomplete immune reconstitution after initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with severe CD4+ cell depletion. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(12):1794–1803. doi: 10.1086/379900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.May MT, Sterne JA, Costagliola D, et al. Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) Cohort Collaboration. HIV treatment response and prognosis in Europe and North America in the first decade of highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis. Lancet. 2006;368(9534):451–458. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehandru S, Poles MA, Tenner-Racz K, et al. Lack of mucosal immune reconstitution during prolonged treatment of acute and early HIV-1 infection. PLoS Med. 2006;3(12):e484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carr A, Cooper DA. Adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy. Lancet. 2000;356(9239):1423–1430. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02854-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandra RK, editor. Nutrition and Immunology. New York, NY: Alan R. Liss; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webb AL, Villamor E. Update: effects of antioxidant and non-antioxidant vitamin supplementation on immune function. Nutr Rev. 2007;65(5):181–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fawzi WW, Msamanga GI, Spiegelman D, et al. A randomized trial of multivitamin supplements and HIV disease progression and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(1):23–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiamton S, Pepin J, Suttent R, et al. A randomized trial of the impact of multiple micronutrient supplementation on mortality among HIV-infected individuals living in Bangkok. AIDS. 2003;17(17):2461–2469. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200311210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Souza Júnior O, Treitinger A, Baggio GL, et al. alpha-Tocopherol as an antiretroviral therapy supplement for HIV-1-infected patients for increased lymphocyte viability. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43 (4):376–382. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2005.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaruga P, Jaruga B, Gackowski D, et al. Supplementation with antioxidant vitamins prevents oxidative modification of DNA in lymphocytes of HIV-infected patients. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32 (5):414–420. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00821-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiser JD, Campa AM, Ondercin JP, Leoung GS, Pless RF, Baum MK. Micronutrient supplementation increases CD4 count in HIV-infected individuals on highly active antiretroviral therapy: a prospective, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42(5):523–528. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000230529.25083.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spada C, Treitinger A, Reis M, et al. An evaluation of antiretroviral therapy associated with alpha-tocopherol supplementation in HIV-infected patients. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2002;40(5):456–459. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2002.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1998. A Report of the Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and its Panel on Folate, Other B Vitamins, and Choline and Subcommittee on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000. Panel on Dietary Antioxidants and Related Compounds, Subcommittee on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients, Subcommittee on Interpretation and Uses of DRIs, Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Scaling Up Antiretroviral Therapy in Resource-Limited Settings: Treatment Guidelines for a Public Health Approach. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ministry of Health of the United Republic of Tanzania. National Guidelines for the Clinical Management of HIV/AIDS. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: National AIDS Control Programme (NACP); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fawzi WW, Msamanga GI, Spiegelman D, et al. Randomised trial of effects of vitamin supplements on pregnancy outcomes and T cell counts in HIV-1-infected women in Tanzania. Lancet. 1998;351(9114):1477–1482. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baum M, Cassetti L, Bonvehi P, Shor-Posner G, Lu Y, Sauberlich H. Inadequate dietary intake and altered nutrition status in early HIV-1 infection. Nutrition. 1994;10(1):16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baum MK, Shor-Posner G, Bonvehi P, et al. Influence of HIV infection on vitamin status and requirements. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;669:165–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb17097.x. discussion 173–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coyne-Meyers K, Trombley LE. A review of nutrition in human immunodeficiency virus infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Nutr Clin Pract. 2004;19(4):340–355. doi: 10.1177/0115426504019004340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Verbal Autopsy Standards: Ascertaining and Attributing Cause of Death. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamali A, Wagner HU, Nakiyingi J, Sabiiti I, Kengeya-Kayondo JF, Mulder DW. Verbal autopsy as a tool for diagnosing HIV-related adult deaths in rural Uganda. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25(3):679–684. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.3.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach, 2010 Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach, 2006 Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laurent C, Ngom Gueye NF, Ndour CT, et al. ANRS 1215/1290 Study Group. Long-term benefits of highly active antiretroviral therapy in Senegalese HIV-1-infected adults. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38(1):14–17. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200501010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wester CW, Kim S, Bussmann H, et al. Initial response to highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1C-infected adults in a public sector treatment program in Botswana. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40(3):336–343. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000159668.80207.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fitzmaurice G, Laird N, Ware J. Applied Longitudinal Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abrams B, Duncan D, Hertz-Picciotto I. A prospective study of dietary intake and acquired immune deficiency syndrome in HIV-seropositive homosexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6(8):949–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang AM, Graham NM, Saah AJ. Effects of micronutrient intake on survival in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143(12):1244–1256. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang AM, Graham NM, Semba RD, Saah AJ. Association between serum vitamin A and E levels and HIV-1 disease progression. AIDS. 1997;11(5):613–620. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199705000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allard JP, Aghdassi E, Chau J, et al. Effects of vitamin E and C supplementation on oxidative stress and viral load in HIV-infected subjects. AIDS. 1998;12(13):1653–1659. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199813000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Traber MG, Sokol RJ, Ringel SP, Neville HE, Thellman CA, Kayden HJ. Lack of tocopherol in peripheral nerves of vitamin E-deficient patients with peripheral neuropathy. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(5):262–265. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198707303170502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slain D, Amsden JR, Khakoo RA, Fisher MA, Lalka D, Hobbs GR. Effect of high-dose vitamin C on the steady-state pharmacokinetics of the protease inhibitor indinavir in healthy volunteers. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25(2):165–170. doi: 10.1592/phco.25.2.165.56945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.González de Requena D, Núñez M, Jiménez-Nácher I, Soriano V. Liver toxicity caused by nevirapine. AIDS. 2002;16(2):290–291. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martínez E, Blanco JL, Arnaiz JA, et al. Hepatotoxicity in HIV-1-infected patients receiving nevirapine-containing antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2001;15 (10):1261–1268. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200107060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sulkowski MS, Thomas DL, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Hepatotoxicity associated with antiretroviral therapy in adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus and the role of hepatitis C or B virus infection. JAMA. 2000;283(1):74–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johannessen A, Naman E, Ngowi BJ, et al. Predictors of mortality in HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy in a rural hospital in Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stringer JS, Zulu I, Levy J, et al. Rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy at primary care sites in Zambia: feasibility and early outcomes. JAMA. 2006;296 (7):782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zachariah R, Fitzgerald M, Massaquoi M, et al. Risk factors for high early mortality in patients on antiretroviral treatment in a rural district of Malawi. AIDS. 2006;20(18):2355–2360. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801086b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koethe JR, Heimburger DC. Nutritional aspects of HIV-associated wasting in sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(4):1138S–1142S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28608D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health Organization. Management of Severe Malnutrition: A Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 45.PrayGod G, Range N, Faurholt-Jepsen D, et al. Daily multi-micronutrient supplementation during tuberculosis treatment increases weight and grip strength among HIV-uninfected but not HIV-infected patients in Mwanza, Tanzania. J Nutr. 2011;141(4):685–691. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.131672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo K, Grobler A, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral drugs during tuberculosis therapy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(8):697–706. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blanc FX, Sok T, Laureillard D, et al. CAMELIA (ANRS 1295–CIPRA KH001) Study Team. Earlier versus later start of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults with tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(16):1471–1481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mamlin J, Kimaiyo S, Lewis S, et al. Integrating nutrition support for food-insecure patients and their dependents into an HIV care and treatment program in western Kenya. Am J Public Health. 2009;99 (2):215–221. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.137174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. [Accessed September 19, 2012];Policy guidance on the use of emergency plan funds to address food and nutrition needs. http://www.pepfar.gov/guidance/77980.htm.

- 50.Cantrell RA, Sinkala M, Megazinni K, et al. A pilot study of food supplementation to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy among food-insecure adults in Lusaka, Zambia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(2):190–195. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818455d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ndekha MJ, Manary MJ, Ashorn P, Briend A. Home-based therapy with ready-to-use therapeutic food is of benefit to malnourished, HIV-infected Malawian children. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94(2):222–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb01895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Oosterhout JJ, Ndekha M, Moore E, Kumwenda JJ, Zijlstra EE, Manary M. The benefit of supplementary feeding for wasted Malawian adults initiating ART. AIDS Care. 2010;22(6):737–742. doi: 10.1080/09540120903373581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koethe JR, Chi BH, Megazzini KM, Heimburger DC, Stringer JS. Macronutrient supplementation for malnourished HIV-infected adults: a review of the evidence in resource - adequate and resource-constrained settings. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(5):787–798. doi: 10.1086/605285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mahlungulu S, Grobler LA, Visser ME, Volmink J. Nutritional interventions for reducing morbidity and mortality in people with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD004536. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004536.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.