Abstract

Objectives

To determine the efficacy of a video-based dog bite prevention intervention at increasing child knowledge and describe any associated factors; and to assess the acceptability of providing this intervention in a pediatric emergency department (PED).

Methods

This cross-sectional, quasi experimental study enrolled a convenience sample of 5–9 year old patients and their parents, presenting to a PED with non-urgent complaints or dog bites. Children completed a 14-point simulated scenario test used to measure knowledge about safe dog interactions pre-/post- a video intervention. Based on previous research, a passing score (≥11/14) was defined a priori. Parents completed surveys regarding sociodemographics, dog-related experiential history and the intervention.

Results

There were 120 child/parent pairs. Mean child age was 7 (SD 1) and 55% were male. Of parents, 70% were white, 2/3 had more than high school education, and half had incomes <$40,000. Current dog ownership was 77%; only 6% of children had received prior dog bite prevention education. Test pass rate was 58% pre-intervention; 90% post-intervention. Knowledge score increased in 83% of children; greatest increases were in questions involving stray dogs or dogs that were fenced or eating. Younger child age was the only predictor of failing the post-test (p<0.001). Nearly all parents found the intervention informative; 93% supported providing the intervention in the PED.

Conclusions

Child knowledge of dog bite prevention is poor. The video-based intervention we tested appears efficacious at increasing short-term knowledge in 5–9 year old children and is acceptable to parents. Parents strongly supported providing this education.

Keywords: dog bite, injury prevention, pediatric, emergency department, education, knowledge

INTRODUCTION

Dog bites to children represent a serious and significant mechanism of pediatric injury, and contribute to the burden of emergency medical services nationwide. Of the approximately 4.5 million annual dog bites in the United States (US), nearly 1 million of the victims are less than 18 years of age.1 Among these children, those aged 5–9 years have the highest incidence of reported and medically treated dog bites1 and alone account for nearly 45,000 emergency department (ED) visits each year, or approximately 200 visits per 100,000 population.2 The associated direct and indirect lifetime costs for dog bite injuries to this 5–9 year old population are estimated to sum to over 280 million dollars.3

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recognizes the importance of dog bite prevention in children and promotes consistent messaging on how to prevent these bites.4 These safety messages include knowledge tips such as “Do not disturb a dog that is sleeping, eating, or caring for puppies”; “Never reach through or over a fence to pet a dog”; and what to do if approached by an unknown dog. Our prior work has shown that children generally lack knowledge of these dog bite prevention tips, that younger children have the least knowledge, and that less than 30% of children or their parents have ever received dog bite prevention education although nearly 90% of parents desire it.5

Many dog bite prevention programs teach children how to be safe around dogs. The majority are school-based and primarily conducted in-person, which can be expensive and involved. Few programs have been empirically studied. Those that have were effective in increasing child knowledge of safe dog interactions6 and improving safe behaviors around a live dog.7 Video-based dog bite prevention programs are less costly, less involved and more easily disseminated than in-person education, although little evidence exists as to their efficacy.

The overarching aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of video-based prevention education offered in a clinical setting, the pediatric ED (PED), as EDs have been suggested as venues which offer “teachable moments” for injury prevention.8–10 We evaluated the dog bite prevention knowledge of children aged 5–9 years before and after the video intervention, and explored factors that that might be associated with knowledge change. We hypothesized that children aged 5–9 years would have increased dog bite prevention knowledge after receiving a video-based dog bite prevention intervention, and that knowledge change would be unaffected by sociodemographic or dog-related experiential factors.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Collection

This cross-sectional, quasi experimental study enrolled a convenience sample of 5–9 year old patients and their parents/legal guardians who presented to the ED of a Level 1 pediatric trauma center for any non-emergent chief complaint and/or a stable dog bite. This ED has over 90,000 annual pediatric visits and treats over 300 child dog bite victims each year. Between January 2011 and August 2011, a trained Clinical Research Coordinator (CRC) screened for potential participants by reviewing an electronic medical record in real time. Participants were excluded if they were non-English speaking, had been previously enrolled in this study, or the child was unable complete the study because of severe illness, injury, or developmental delay. The study was approved by the hospital institutional review board. Informed written consent was obtained from all parent/legal guardian participants; assent was obtained from all child participants.

After enrolling in the study, and during natural wait times during their PED visit, child participants completed a 14-point simulated scenario knowledge test about safe dog interactions.5 Test questions included seven text and seven picture scenarios that portrayed dogs in specific situations. Pictures were 8”×11” colored photographs of either a black shepherd mix dog or a golden retriever dog in settings such as behind a fence, lying on a dog bed with a toy, eating dog food out of a bowl, or sitting in a car with the window down. All questions were posed to elicit “yes” or “no” answers, for example “Should you pet this dog”. If the child could not read, the CRC read the question to the child and documented the child’s answer. Parents were not allowed to assist the child during the test. After this pre-test, the child viewed the didactic session of a video-based dog bite prevention program entitled “Dogs, Cats & Kids” (approximately 20 minutes).11 This video which is commercially-available from the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and other venues, entails lessons on how to be safe around dogs. The parent was allowed to watch the video with the child. After viewing the video intervention, the child repeated the identical 14-point simulated scenario knowledge test in the same manner. All questions asked in this knowledge test were addressed in the dog bite prevention intervention. Parents completed surveys which included questions regarding sociodemographic factors, dog ownership, prior dog bites, previous dog bite prevention education, and perceived acceptability regarding the video intervention. At the end of the study, all participants received the AAP dog bite prevention pamphlet.4 Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools.12

Data Analysis

Child knowledge scores were calculated by summing the number of correct answers to the 14 simulated scenario knowledge test questions. There were no missing values for knowledge test questions. Based on prior research with questions from the dog bite prevention test, we set an a priori pass rate of 11/14 questions correct (78.5%). We have previously had found a mean knowledge score of 70% (<10/14 questions correct) for children aged 5–9 years.13 Given the hypothesis that there is increased knowledge after a video-based dog bite prevention intervention, we predicted that the mean knowledge test score would increase to ≥85% (≥12/14 questions correct) after receiving this intervention. A sample size of 120 was determined a priori to detect this 15% difference with 80% power and a two-sided significance level of 0.05. Comparisons between groups used student’s t test or Fisher’s Exact test. Pre- and post- intervention scores were compared using the Wilcoxen signed-rank test and McNemar's test, 95% confidence intervals were calculated. All analyses were conducted using SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Of 273 parent/child pairs approached, 120 completed the study and were included in this analysis. Mean child age was 7 years (SD 1); 66 (55%) were male. Fourteen (12%) children presented to the PED for a dog bite, the remaining 106 (88%) children presented for other non-urgent complaints. Of parents, 105 (88%) were female, 84 (70%) were white, 80 (67%) had more than a high school education, and 60 (50%) reported incomes less than $40,000. The majority (92; 77%), currently owned a dog, with dog bite prevalence among parents at 35%. Only 7 (6%) children and 17 (14%) parents had ever received formal dog bite prevention education (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample demographics and predictors of child post-test knowledge score

| Total (N = 120) |

Pass (n = 108) |

Fail (n = 12) |

P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | |||||||

| Age, y (SD) | 7 | (1) | 7 | (1) | 5 | (1) | <0.001 |

| Female | 54 | 45% | 49 | 45% | 5 | 42% | 1.00 |

| Current visit for dog bite | 14 | 12% | 13 | 12.% | 1 | 8% | 1.00 |

| Previous formal dog bite prevention education | 7 | 6% | 6 | 6% | 1 | 8% | 0.53 |

| Parent | |||||||

| Age, y (SD) | 34 | (7) | 34 | (7) | 31 | (5) | 0.10 |

| Female | 105 | 88% | 94 | 87% | 11 | 92% | 1.00 |

| White | 84 | 70% | 78 | 72% | 6 | 50.% | 0.18 |

| More than high school education | 80 | 67% | 75 | 69% | 5 | 42% | 0.10 |

| Income less than $40,000 | 60 | 50% | 53 | 49% | 7 | 58% | 0.76 |

| Current dog owner | 92 | 77% | 83 | 77% | 9 | 75% | 1.00 |

| Previous dog bite | 41 | 35% | 38 | 36% | 3 | 25% | 0.54 |

| Previous formal dog bite prevention education | 17 | 14% | 15 | 14% | 2 | 17% | 0.68 |

Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

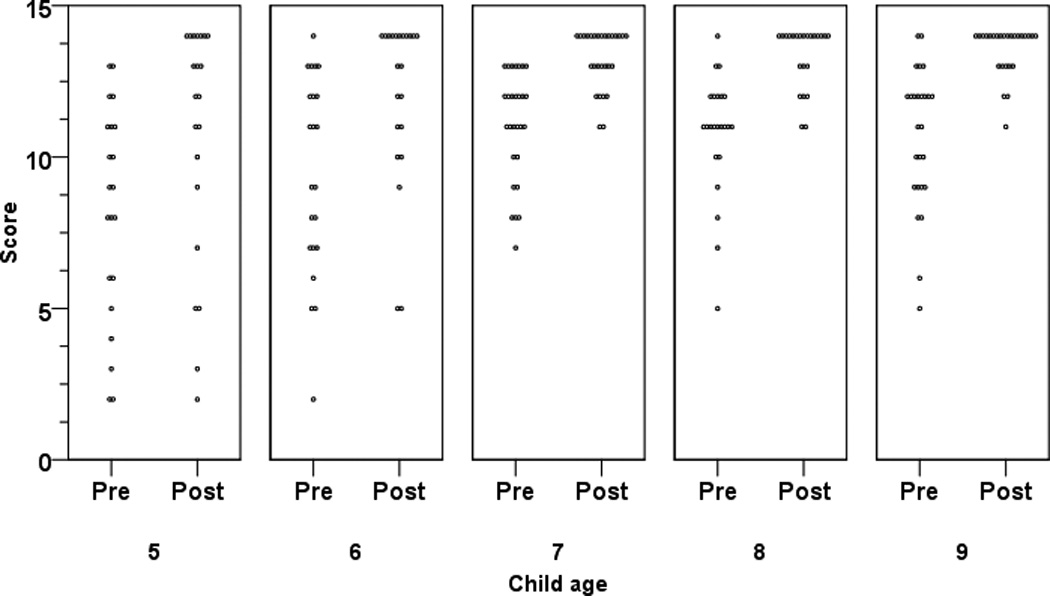

Pre-intervention, the median child knowledge score was 11 (range 2–14) while post-intervention the median child knowledge score was 14 (range 2–14) (difference in medians 3, 95% CI 2.5 – 3.5, p<0.001). The pass rate increased from 58% to 90% (difference in proportions 32%, 95% CI 23% – 40%, p<0.001). One hundred (83%) children had increased knowledge scores after the intervention, with a median of 3 more questions answered correctly (Table 2). Post-test raw scores and subsequent pass rates increased with advancing age (Figure 1.) All children that passed the knowledge test pre-intervention also passed post-intervention test. Of those children that failed the pre-test, 38/50 (76%) had passing scores post-intervention. Younger child age was the only predictor of failing the post-test (p<0.001). No significant relationship was found between failing the post-test and other sociodemographic variables or dog-experiential history (eg, dog ownership, previous dog bites, or prior dog bite education (Table 1)).

Table 2.

Change in number of questions answered correctly post-intervention (N = 120)

| Pre-test number correct | Change in number correct | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | Median | Min | Max | Median | Min | Max | |

| Increase | 100 | 83% | 11 | 2 | 13 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 9.0 |

| Decrease | 6 | 5% | 8.5 | 5 | 13 | −1.5 | −3.0 | −1.0 |

| No change | 14 | 12% | 12.5 | 2 | 14 | -- | -- | -- |

Figure 1.

Dot plot of pre- and post-intervention raw scores paneled by child age; passing score is ≥ 11. Each dot represents a single case (N=120).

All test questions were answered correct more frequently in the post-test than the pre-test (Table 3). Questions with the largest increases in correct answers post-intervention compared to pre-intervention were those related to: what to do when an unknown dog approaches (difference range 24–55%), petting a fenced dog (difference range 16–33%) and petting dog that is eating (difference range 13–28%). In comparison, questions that were most often answered correctly both pre-intervention and post-intervention were those related to: asking permission before petting an unknown dog (difference 5%), petting a sleeping dog (difference 6%), and trying to capture a stray dog (difference 7%).

Table 3.

Number and percentage of correct responses: pre-test versus post-test

| Pre-test | Post-test | Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 120) | (N = 120) | (N = 120) | ||||

| Question | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| A strange dog comes near you and starts barking; do you run away? | 37 | 31 | 103 | 86 | 66 | 55 |

| Should you pet this dog? (Picture of a yellow dog behind a fence) | 66 | 55 | 106 | 88 | 40 | 33 |

| Should you pet this dog? (Picture of a yellow dog with a toy) | 61 | 51 | 96 | 80 | 35 | 29 |

| Should you pet this dog? (Picture of a yellow dog that is eating) | 77 | 64 | 110 | 92 | 33 | 28 |

| A dog you don’t know runs up to you; do you stand very still and wait for the dog to walk away? | 86 | 72 | 115 | 96 | 29 | 24 |

| Should you pet this dog? (Picture of a black dog behind a fence) | 92 | 77 | 111 | 93 | 19 | 16 |

| Should you pet this dog? (Picture of a black dog that is eating) | 91 | 76 | 107 | 89 | 16 | 13 |

| Your friend’s dog is tied in the yard; do you pet the dog? | 93 | 78 | 109 | 91 | 16 | 13 |

| Should you pet this dog? (Picture of a black dog in a car) | 95 | 79 | 111 | 93 | 16 | 13 |

| A dog you don’t know is sniffing a tree in the neighbor’s yard; do you reach out and try to grab the dog? | 108 | 90 | 116 | 97 | 8 | 7 |

| Your neighbor’s dog is sleeping; do you try petting the dog? | 105 | 88 | 112 | 93 | 7 | 6 |

| Your cousin’s dog is playing with a toy; do you take the toy? | 108 | 90 | 114 | 95 | 6 | 5 |

| Your uncle gets a new dog; do you ask him before petting the dog? | 110 | 91 | 116 | 97 | 6 | 5 |

| Should you pet this dog? (Picture of a black dog with a toy) | 88 | 73 | 93 | 78 | 5 | 4 |

Interestingly, among pictorial questions involving two different phenotypes of dog in similar settings, children more frequently answered incorrectly those involving a yellow dog (retriever) on the pre-test, as compared to those involving a black dog (shepherd mix). The identical post-test pictoral questions, however, had similar correct answer frequencies, thus translating to larger increases in post-intervention knowledge in pictoral questions involving a yellow dog (difference range 28–33%) versus those involving a black dog (difference range 4–16%).

Ninety-one parents (76%) reported watching the video. Of these, 90 (99%) felt that the video intervention taught their child how to be safe around dogs, and 87 (96%) agreed that the information provided would help their child prevent dog bites. Additionally, 83 (91%) of parents rated the video as “good” or “very good”, and 85 (93%) felt that playing the video in the PED was a “good idea”.

DISCUSSION

Dog bites are a significant injury problem and account for numerous ED visits every year. National organizations recommend consistent strategies on how to prevent dog bites and suggest that such discussions be a part of routine anticipatory guidance for injury control in certain age groups. Most children, however, have not received any formal dog bite prevention education and lack basic knowledge about how to prevent these injuries.5 Although dog bite prevention programs exist, few have been formally evaluated and none have been studied as the exclusive injury prevention topic in the PED setting. The results of our study suggest a video-based dog bite prevention program delivered in the PED is acceptable to parents and can increase child knowledge of how to be safe around dogs.

At baseline, nearly half of children in our study failed the dog bite prevention knowledge test. In comparison, after the viewing the brief video intervention, 90% of children passed the identical knowledge test. Despite variability in our participant’s sociodemographics, dog-related experiential factors (i.e. dog ownership, prior dog bite, previous dog bite education), and presenting complaints, younger age was the only predictor of not passing the dog bite prevention knowledge test after receiving the intervention. This finding of increased dog bite prevention knowledge for nearly all children after viewing a relatively brief educational video is especially important considering that others have shown that dog bite prevention education can increase a child’s safe behaviors around a live dog.7 More research is warranted to prospectively evaluate the effectiveness of such types of video-based or multimedia interventions, in measuring behavior change and/or injury rates as outcomes.

In addition to showing an overall increase in dog bite prevention knowledge, our study revealed several themes of dog bite prevention knowledge that appear less well known by children and which were particularly affected by the educational intervention. For example, themes of what to do when a stray dog approaches, not approaching a fenced dog and not petting a dog that is eating, consistently had the largest percentage of children answering the question incorrectly on the pre-test but correctly on the post-test. This proportion of children who incorrectly answered pre-test questions, but correctly answered the identical post-test questions, suggests that such dog bite recommendation themes were most affected by the intervention. Children’s lack of knowledge of these dog bite prevention themes may be critical in understand why the majority of dog bites to children occur in circumstances of “resource guarding” (e.g., a child pets a dog that is eating or chewing on toys)14 and/or why over one-third of fatal dog bites to children occur in circumstances of a child gaining unauthorized access to a fenced dog.15 Increasing knowledge of these essential dog bite prevention themes is likely to have the highest benefit in preventing future dog bites, and our data suggest the video intervention may help to achieve this goal.

Our results bring up an interesting safety issue that has not been previously described —children may identify certain dogs as more or less safe than others based on appearance. This incidental finding suggests the need for further work to determine whether children incorrectly assume certain phenotypes or breeds of dog are more or less likely to bite given similar settings. While others may debate whether certain types of dog are more or less vicious, what is clear is that children need to be aware that all dogs can and may bite given the right settings. Misperceptions based on dog breed and/or phenotype could adversely impact the benefits of dog bite prevention. Ultimately, children should be taught the basic strategies of dog bite prevention for all dogs, recommended by national organizations. We encourage further research to understand disparities among dog bite prevention themes and potentially dog phenotypes so as to elaborate risk and develop more effective prevention interventions.

Lastly, our findings reveal that delivery of a video-based dog bite prevention intervention in the PED setting is very well-accepted. Parent endorsement was nearly universal, and more than 90% of parents rated the video positively. Over three-quarters of parents in our study were current dog owners, yet only 6% of their children had ever received formal dog bite prevention education. Thus, it is no surprise that the vast majority of parents felt that providing such type of dog bite prevention education in the PED was a “good idea”. The broad support for providing brief video interventions in the PED is invaluable to promoting clinical settings as a venue for offering low-cost, minimally involved, multimedia interventions, such as the one we evaluated. Whether the effectiveness of the intervention in the PED differs from other venues remains to be established.

Within the scope of our study there were several limitations. First, we recruited a convenience sample of ED patients presenting to a regional pediatric trauma center. This sample may not be generalizable to all populations or settings, although we note our sample was diverse and has similar demographics to our overall PED population. Though our recruitment rate was nearly 50%, an increased rate may have been achieved by offering incentives to participate, however we elected against this option to increase the generalizability to most ED settings where such incentives to participate may not be available. Additionally, although our sample size for our primary hypothesis was calculated a priori, the overall number of participants was relatively small, thus subgroup comparisons should be interpreted with caution. We encourage validation of our findings in other settings and with larger participant groups. Second, while the video length of nearly 20 minutes was feasible for this study; this duration may not be practical in other settings. To be sustainable in the ED, such multimedia prevention interventions may require additional resources such a video/DVD player and would likely benefit from being more brief and occurring during natural wait times, so as to not obstruct patient throughput. Third, although the knowledge test was developed from dog bite prevention recommendations espoused by the AAP, neither the questionnaire nor the use of a passing threshold have been validated. While our questions may not completely capture knowledge, or might be affected by scale and range issues, we contend that the changes observed reflect an increase in knowledge arising from the video intervention. Fourth, our evaluation of which knowledge domains were poorly understood and which were most impacted by the education is descriptive, and there is scope for future work to better target themes of dog bite prevention, and to include such considerations of dog phenotypes. Last, our post-study assessment was given immediately after the intervention and does not address the important outcomes of long term knowledge change, behavior change or dog bite incidence. It is unknown whether increased scores on our knowledge test translates to safer behavior and thus decreased injury rates. Research that evaluates the effectiveness of dog bite prevention interventions on changing behaviors by measuring dog bite incidence and/or injury severity is lacking, and we strongly support recommendations for “high quality studies that measure dog bite rates as an outcome.”16

CONCLUSIONS

This study reveals that children who are most at risk of dog bites – those aged 5–9 years – lack knowledge of how to stay safe around dogs and are rarely educated on this important injury topic. The brief video-based intervention we tested in the PED increased knowledge of nationally espoused dog bite prevention recommendations in nearly all children. With the exception of younger child age, neither demographics nor dog experiential history influenced this increase in dog bite prevention knowledge. Additionally, our study describes several dog bite prevention themes that are lesser known and more often affected by education. The impact of the video intervention on knowledge, combined with strong parental support, suggest offering video education in a PED would be helpful in addressing the dog bite problem in children.

What’s Known on This Subject

Dog bites are a significant injury risk to children and contribute to the burden of emergency medical services nationally. Dog bite prevention recommendations and programs exist, though few have been studied and none have been exclusive evaluated in emergency settings.

What This Study Adds

Child knowledge of dog bite prevention is poor. The video-based intervention we tested appears efficacious at increasing dog bite prevention knowledge in children and is very well-accepted by parents. Parents strongly supported providing this education in the emergency setting.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This publication was supported in part by an Institutional Clinical and Translational Science Award, NIH/NCRR Grant Number 5UL1RR026314-03. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- CRC

Clinical research coordinator

- ED

Emergency department

- PED

Pediatric emergency department

- PI

Principal investigator

- REDCap

Research Electronic Data Capture

- SD

Standard deviation

- US

United States

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor’s Statement

Cinnamon A. Dixon, DO, MPH: Dr. Dixon conceptualized and designed the study, created study instruments, coordinated and supervised data collection, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Wendy J. Pomerantz, MD, MS: Dr. Pomerantz helped conceptualize and design the study, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Kimberly W. Hart, MA: Ms. Hart performed the data analyses, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Christopher J. Lindsell, PhD: Dr. Lindsell helped conceptualize and design the study, oversaw data analysis, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

E. Melinda Mahabee-Gittens, MD, MS: Dr. Mahabee-Gittens helped conceptualize and design the study, oversaw study procedures, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gilchrist J, Sacks JJ, White D, Kresnow MJ. Dog bites: still a problem? Inj Prev. 2008;14(5):296–301. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.016220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC) [Accessed December 2011];. WISQARS Leading Causes of Nonfatal Injury Reports. Available at: http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/nfilead2001.html.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC) [Accessed Accessed December 2011];WISQARS Cost of Injury Reports. Available at: http://wisqars.cdc.gov:8080/costT/

- 4.American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Healthy Children Organization. What you should know about dog bite prevention. [Accessed Jan 2012]. Available at: http://www.healthychildren.org/English/news/Pages/Dog-Bite-Prevention.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon CA, Mahabee-Gittens EM, Hart KW, Lindsell CJ. Dog bite prevention: an assessment of child knowledge. J Pediatr. 2012;160(2):337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson F, Dwyer F, Bennett P. Prevention of dog bites: Evaluation of a brief educational intervention program for preschool children. J Comm Psychol. 2003;31(1):75–86. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman S, Cornwall J, Righetti J, Sung L. Preventing dog bites in children: randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention. BMJ. 2000;320(7248):1512–1513. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7248.1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babcock Irvin C, Wyer PC, Gerson LW. Preventive care in the emergency department, Part II: Clinical preventive services--an emergency medicine evidence-based review. Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Public Health and Education Task Force Preventive Services Work Group. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(9):1042–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gittelman MA, Pomerantz WJ, Fitzgerald MR, Williams K. Injury prevention in the emergency department: a caregiver's perspective. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(8):524–528. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318180fddd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gittelman MA, Pomerantz WJ, Frey LK. Use of a safety resource center in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25(7):429–433. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181ab77e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dogs, Cats & Kids [DVD] Chicago, Illinois: Donald Manelli & Associates; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon C, Mahabee-Gittens E, Hart K, Lindsell C. Dog bite prevention: an assessment of child knowledge. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.07.016. Unpublished data. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reisner I, Shofer F, Nance M. Behavioral assessment of child-directed canine aggression. Inj Prev. 2007;13(5):348–351. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.015396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sacks J, Sattin R, Bonzo S. Dog bite-related fatalities from 1979 through 1988. JAMA. 1989;262:1489–1492. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.11.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duperrex O, Blackhall K, Burri M, Jeannot E. Education of children and adolescents for the prevention of dog bite injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD004726. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004726.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]