Abstract

Current treatments for Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) involve surgery, radiotherapy, and cytotoxic chemotherapy; however, these treatments are not effective and there is an urgent need for better treatments. We investigated GBM cell killing by a novel drug combination involving DT-EGF, an Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-targeted bacterial toxin, and Tumor Necrosis Factor-Related Apoptosis Inducing Ligand (TRAIL) or antibodies that activate the TRAIL receptors DR4 and DR5. DT-EGF kills GBM cells by a non apoptotic mechanism whereas TRAIL kills by inducing apoptosis. GBM cells treated with DT-EGF and TRAIL were killed in a synergistic fashion in vitro and the combination was more effective than either treatment alone in vivo. Tumor cell death with the combination occurred by caspase activation and apoptosis due to DT-EGF positively regulating TRAIL killing by depleting FLIP, a selective inhibitor of TRAIL receptor-induced apoptosis. These data provide a mechanism-based rationale for combining targeted toxins and TRAIL receptor agonists to treat GBM.

Keywords: Diphtheria toxin, TRAIL, apoptosis, autophagy

Introduction

There are an estimated 20,500 new cases of brain and nervous system cancers and 12,700 brain cancer deaths each year in the United States [1]. Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), is the most common and aggressive type of primary brain tumor [2] and these tumors are usually recalcitrant to current therapies [3]. This results in a five year survival rate of less then five percent that has been essentially unchanged for decades [4] and creates a great need for improved treatment strategies for this disease.

Fusion toxins [5, 6] combine a toxin such as diphtheria toxin (DT) with a ligand that recognizes a receptor found on cancer cells. After endocytosis of the targeted receptor, DT ADP-ribosylates the translation factor EF-2, which leads to the inhibition of protein synthesis [7] and cell death [8, 9]. Nearly 50% of GBM's overexpress epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and this increased expression correlates with poorer prognosis [10]. Thus, the EGF receptor is a good target for the development of a fusion toxin for treating this disease and by fusing EGF to diphtheria toxin (DT-EGF), we showed that we could kill GBM cells and cause GBM tumor regression in an EGFR-dependent manner [11, 12]. Protein therapeutics such as DT-EGF, TRAIL or antibodies are suitable for treatment of brain tumors because they can be administered by convection enhanced delivery, which uses the blood brain barrier to confine the drugs to the brain [13, 14].

Apoptosis is executed through two main pathways (the extrinsic or intrinsic pathways), which can both be targeted therapeutically [15]. One extrinsic, or death receptor, pathway is activated by Tumor Necrosis Factor-Related Apoptosis Inducing Ligand (TRAIL), which normally functions to inhibit tumor development and progression [16]. TRAIL activates two death receptors called DR4 and DR5 [16, 17], which are targeted therapeutically by several drugs that are in clinical trials both as monotherapy and combined with other drugs [18, 19]. Activated DR4 and DR5 recruit an adaptor protein, Fas associated death domain protein (FADD), which in turn recruits and activates procaspase 8 [20]. Active caspase 8 then cleaves procaspase 3 resulting in its catalytic activation and stimulation of the apoptosis cascade. Multiple mechanisms influence TRAIL sensitivity and resistance [21]. For example, TRAIL sensitivity can be reduced by increasing molecules that block TRAIL receptor induced apoptosis such as Flice-like inhibitory protein (FLIP), which is a caspase 8 like protein that interacts with FADD and inhibits death receptor-induced apoptosis at the level of the receptor complex [22]. TRAIL sensitivity is also determined by more general apoptosis inhibitors including inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) such as XIAP [23].

The main premise of combinatorial drug therapy is that cancer cells are more effectively killed and less likely to develop resistance to combinations of drugs especially if they have different mechanisms of action [24] and the majority of successful chemotherapy treatments use a multiple drug approach that was usually determined empirically. A major ongoing effort in cancer research is to develop more rational, mechanism-based approaches to determine which drugs to combine [24]. Combining DT-EGF and TRAIL in GBM cells is attractive because they kill by quite different mechanisms; our recent work showed that DT-EGF activates autophagy in GBM cells and that this autophagy inhibits apoptosis and thus causes DT-EGF to kill via a non-apoptotic mechanism [25], whereas TRAIL receptor agonists directly activate caspases and kill through apoptosis [16, 17]. Here, we asked if combining agents that work in such different ways is effective by combining DT-EGF with TRAIL receptor agonists. We found that this results in synergistic GBM cell killing in vitro and improved anti-tumor response in vivo. We further found that the synergy occurs because DT-EGF causes a reduction in FLIP, which potentiates TRAIL receptor-induced cell death by significantly increasing the efficiency of caspase activation by TRAIL receptors.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

GBM cells were obtained from American Type Culture collection and maintained in MEM growth medium (HyClone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Logan, UT) in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37°C. DT-EGF was prepared and used as described previously [11, 26]. Unless otherwise noted, chemicals and reagents were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Cycloheximide at 5ug/ml, 3,4-Dihydro-5[4-(1-piperindinyl)butoxy]-1(2H)-isoquinoline (DPQ) at 30 μM, carbobenzoxy-valyl-alanyl-aspartyl-[O-methy]- fluoromethylketone (zVADfmk) (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA) at 25 μM. TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Lexatumumab and Mapatumumab (HGS, Rockville, MD)

Immunoblotting

At the indicated times, 1 × 106 cells were harvested, and lysates were prepared by boiling in SDS buffer 10 min prior to gel electrophoresis. Lysates were resolved on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Blots were incubated with antibodies that recognize X-IAP, FLIP, Bid, Caspase 3, PARP (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA), and β-Actin (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Blots were then incubated with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA). Detection was performed using the chemiluminescent ECL reagent (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA), and developed on Blue Basic Autorad Film (ISC Bioexpress, Kaysville, UT).

siRNA

SMARTpool siRNAs targreting FLIP and XIAP were obtained from Dharmacon (Thermo Scientific Dharmacon Products, Lafayette, CO). 24hours prior to transfection plate cells at 300,000 cells/ 60mm dish in MEM without penicillin/streptomycin (P/S). Transfection media reagent was prepared by mixing 20 μl of smartpool (Dharmafect) siRNA (20μM concentration) with 380μl of OptiMEM in a 1.5ml microcentrifuge tube and incubate for 5 minutes. In another microcentrifuge tube 6μl of Dharmafect 1 reagent and 394μl of OptiMEM was mixed and incubated for 5 minutes. The two tubes were mixed together and incubated for another 20minutes. siRNA mixture was added onto cells dropwise while covering the entire dish. 24 hours later media was replaced with fresh MEM complete with P/S.

Caspase 3/7 Activity

Plate cells in a 96 well black-walled plate at a concentration of 3,000 cells per well. Add drugs in triplicate at timepoint of interest. 1 hour prior to the end of assay add Caspase-Glo 3/7 reagent (Promega, Madison, WI) to each well at a 1:1 ratio according to manufacturers' instructions. Incubate in the dark for 1 hour. Measure samples using Veritas microplate luminometer (Turner BioSystems, Sunnyvale, CA). This assay specifically recognizes caspase 3/7 activity.

MTS cell viability

Cells are plated in a 96 well format at 3,000 cells per well. Drugs are added to triplicate wells. 1 hour prior to the end of the experiment cells are treated with 20 μl of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt (MTS) (Promega, Madison, WI) according to manufacturers' intructions. MTS reagent is light sensitive; therefore, the plate should be incubated for 1 hour in the dark at 37°C. Measure samples with a Bio-Rad Benchmark Plus Microplate Spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) at an absorbance value of 490nm.

Light Microscopy

U87MG cells were plated in six well dishes at a density of 50,000 cells per well 24hrs prior to treatment. U87MG cells were treated with their respective stimulants and representative micrographs were taken at the required time points with 10× magnification.

Animals studies

Female athymic nude mice (ages 4-6 weeks) were obtained from NIH. The mice were allowed to adjust to their environment for one week. U87MG cells were injected at a concentration of 10 million cells in 0.1ml into both flanks of the mice (day 1). The tumors were allowed to grow to ∼150 mm3, then on day 8 five animals per group were treated with the specific drug regimen by interstitial injection. Each respective group received phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (HyClone, Logan, Utah), DT-EGF (0.5 ug), Lexatumumab (1.0 ug) and DT-EGF and Lexatumumab in combination. The animals were observed every other day and tumors measured with digital calipers (Mitutoyo Corp., Japan). On day 33 the tumors were measured and the animals euthanized. ANOVA software was used to calculate the correlation between drug treatment and tumor size.

Results

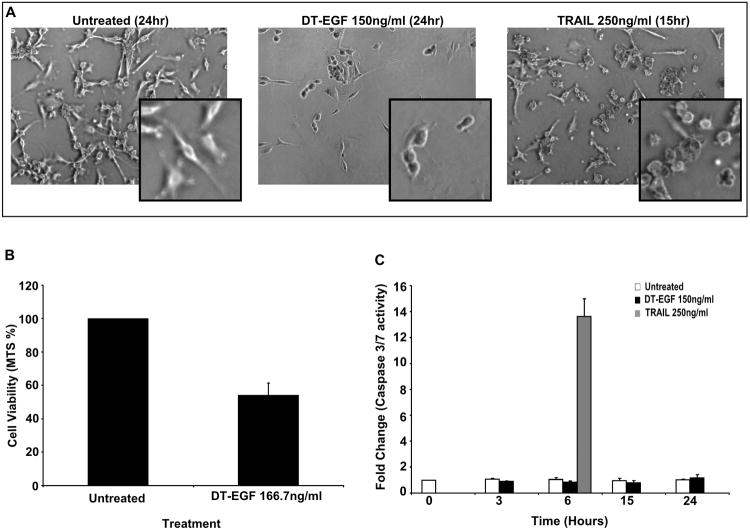

DT-EGF treatment of GBM cells induces non-apoptotic cell death

DT fusion toxins can kill different tumor cells by different mechanisms [27-29]. We recently showed that DT-EGF kills U87MG cells (and other GBM cell lines) by a mechanism that involves autophagy induction that suppresses caspase activation so that GBM killing occurs by a caspase-independent mechanism [30, 31]. To ask if the same tumor cells could be killed by something else through classical apoptosis, we compared U87MG killing by DT-EGF and TRAIL using doses of the drugs that depletes the number of viable cells by about half after 24hrs (Figure 1B). Morphological studies showed that the DT-EGF treated cells appear rounded and lack the characteristic blebbing that is typical of caspase-dependent apoptosis that can be seen in cells treated with TRAIL (Figure 1A) Measurement of effector caspase-3 and -7 activity indicated that DT-EGF treatment does not activate caspases similar to control cells; conversely, a single dose of TRAIL at 6hrs induces significant caspase activity indicating that these cells are capable of undergoing caspase dependent apoptosis (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. DT-EGF kills U87MG cells by a caspase independent cell death mechanism.

(A) Representative micrographs of U87MG cells treated with either DT-EGF (150ng ml−1) or TRAIL (250ng ml−1) depicting morphological differences in dying cells. (B) Cell viability of U87MG cells as determined by MTS assays after 24hours of treatment with DT-EGF (150ng ml−1)(mean +/− SEM from 3 replicates). (C) Effector caspase activity was measured using a caspase 3/7 specific luminogenic substrate on U87MG cells treated with DT-EGF (150ng ml−1) or TRAIL (250ng ml−1) (mean +/− SEM from 3 replicates).

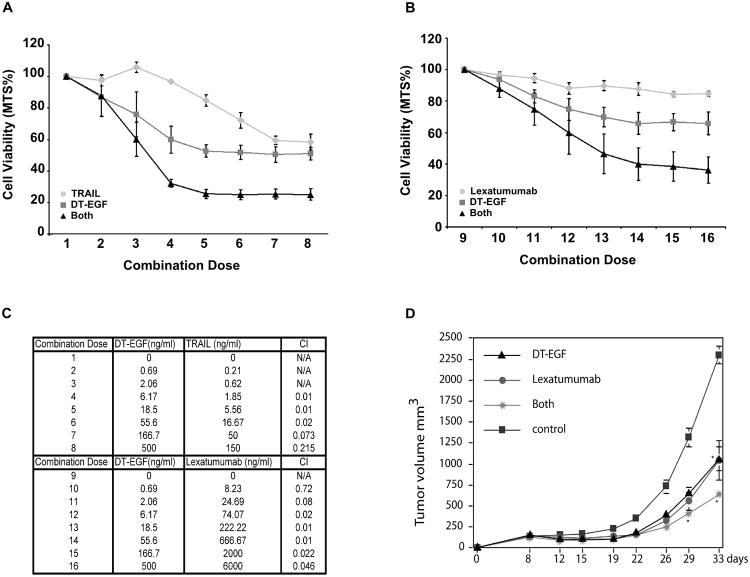

DT-EGF synergizes with TRAIL Receptor-targeted drugs

To test if DT-EGF causes synergistic tumor cell killing when combined with anti-cancer agents that directly activate the apoptosis machinery, we combined DT-EGF and TRAIL or agonistic antibodies (Figure 1C) and measured synergy using the Calcusyn program, which determines synergy using the median effect principal [32, 33]. The combination of TRAIL and DT-EGF (Figure 2A) results in combination index (CI) values of less than 0.3 for multiple combinations (combinations 4-8) indicating that the drugs are synergistic (Figure 2C). Combinations 1-3 were not evaluated as these concentrations included doses where one of the drugs had no detectable effect and the Calcusyn program cannot evaluate combinations under these circumstances. We next tested combinations of agonistic TRAIL receptor monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and DT-EGF. An increase in the overall cell killing was observed with the combination of DT-EGF and lexatumumab, a mAb targeted against the DR5 receptor (Figure 2B) even though lexatumumab on its own was poorly effective at killing U87MG cells. The CI values calculated for the combination of DT-EGF and lexatumumab were under 0.3 for multiple combinations, which again indicates that these drugs work synergistically (Figure 2C). In contrast, mapatumumab, an agonistic mAb targeted against DR4, had no cytotoxic effect on U87MG cells on its own, and DT-EGF does not increase the amount of dying U87MG cells above that achieved by DT-EGF alone (data not shown). To test if synergy occurs in other GBM cells, we tested combinations of DT-EGF and TRAIL in four other GBM cell lines. Marked synergy with CI values < 0.3 were found for 42MGBA, GMS10, and SNB19 cells. There was no synergy in U373 cells, which displayed no killing by TRAIL (Table 1). These data show that DT-EGF can synergize with TRAIL receptor targeted drugs to kill GBM cells in vitro. To test if the combined drugs are also more effective in vivo, we used a xenograft system that previously demonstrated that DT-EGF reduces GBM tumor growth in vivo [12]. Treatment with limiting doses of either DT-EGF or lexatumumab alone had a modest effect on tumor growth rate however combining the two agents at the same doses resulted in significantly greater inhibition of tumor growth (Figure 2D) indicating that the improved tumor cell killing with the combination also occurs when tumors are treated in vivo.

Figure 2. DT-EGF potentiates TRAIL receptor mediated killing in vitro and in vivo.

(A) MTS assay quantifying cell viability of U87MG cells in response to DT-EGF and TRAIL either alone or in combination (mean +/− SEM from 3 replicates). (B) MTS assay quantifying cell viability of U87MG cells in response to DT-EGF and Lexatumumab either alone or in combination (mean +/− SEM from 3 replicates). (C) Table of combination doses between DT-EGF and the TRAIL receptor-targeted drugs. CI value for DT-EGF and TRAIL or Lexatumumab combinations calculated using Calcusyn. (D) U87MG tumor cells were implanted in the flanks of nude mice and tumors were allowed to grow for one week. Tumors were then treated with interstitial as previously described [12] with DT-EGF (0.5 μg), Lexatumumab (1.25 μg), or both in combination. Two-way repeated ANOVA showed a difference *p<0.001 for the combination compared to the single treatment groups (mean +/− SD from 3 replicates).

Table 1.

DT-EGF and TRAIL synergy in GBM cell lines.

| GBM Cell Line | % Cell Death DT-EGF (167ng/ml) | % Cell Death TRAIL (50ng/ml) | % Cell Death Combination | CI | Synergy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U87MG | 50% | 41% | 75% | 0.073 | Yes |

| 42MGBA | 19% | 34% | 68% | 0.21 | Yes |

| GMS10 | 12% | 22% | 30% | 0.214 | Yes |

| SNB19 | 26% | 4% | 30% | 0.265 | Yes |

| U373 | 36% | 1% | 36% | 3.596 | No |

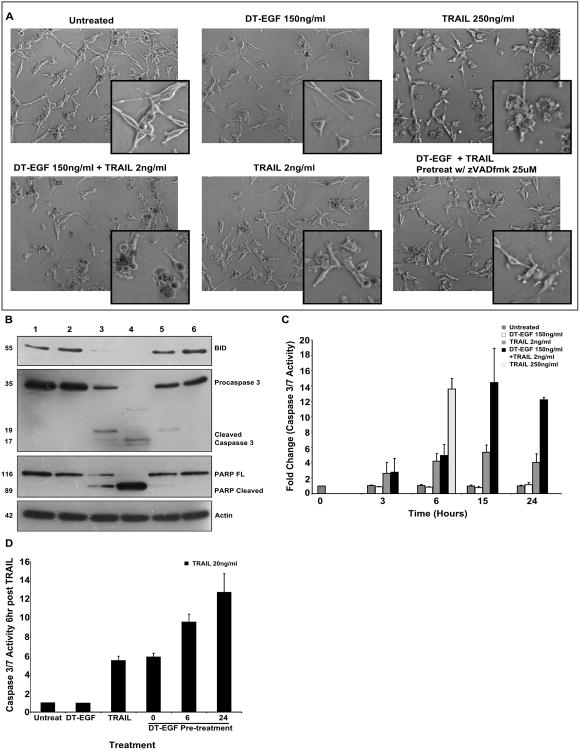

U87MG cells treated with DT-EGF and TRAIL die by apoptosis

Because DT-EGF activates autophagy, which prevents caspase activation in U87MG cells [25], we asked if the death mechanism due to the combination treatment was also independent of caspase activation. We treated cells with a combination of DT-EGF (150ng/ml) and a low dose of TRAIL (2ng/ml) and observed cell morphology that was characteristic of apoptosis and similar to cells treated with a much higher dose of TRAIL (250ng/ml) (Figure 3A). The U87MG cells were completely viable and appear similar to untreated cells in the presence of the low dose of TRAIL alone. We next performed western blot analysis of a well characterized substrate of caspase 3, Poly-ADP ribosyl polymerase (PARP), which was cleaved in response to treatment with DT-EGF and low dose TRAIL to a greater extent than that achieved by the high dose of TRAIL (Figure 3B). Similarly, the combination resulted in greater cleavage of the caspase-8 substrate Bid (Figure 3B) and the caspase 3/7 catalytic activity in response to the combination of DT-EGF and low dose TRAIL was at least equivalent to high doses of TRAIL alone (Figure 3C). Treatment with a pan-caspase inhibitor zVADfmk resulted in protection from apoptotic death as shown in the micrographs (Figure 3A), and no caspase-dependent cleavage in the western analysis (Figure 3B, lane 6). These results indicate that U87MG cells undergo caspase-dependent apoptosis when treated with the combination of DT-EGF and a low dose of TRAIL that was not sufficient to kill the cells alone. Additionally, these data (e.g. compare lanes 3 and 4 in Figure 3B) show that the effect of DT-EGF is to significantly increase the efficiency with which TRAIL receptors can activate caspase-8 and then effector caspases such that the efficiency of TRAIL-induced caspase activity when DT-EGF is present is at least equivalent to that achieved with 75 times more TRAIL when DT-EGF is not present.

Figure 3. DT-EGF and TRAIL kill cells in a caspase dependent apoptotic fashion.

(A) Representative micrographs of U87MG cells treated with either 1. untreated, 2. DT-EGF (150ng ml−1), 3. TRAIL (250ng ml−1), 4. DT-EGF (150ng ml−1) + TRAIL (2ng ml−1), 5. TRAIL (2ng ml−1), 6. DT-EGF (150ng ml−1) + TRAIL (2ng ml−1) + zVADfmk (25 μM) depicting morphological differences in dying cells. (B) Western blot analysis of key apoptotic protein levels in U87MG cells in response to conditions 1-6 from Figure 3A. (C) Effecter caspase activity was measured using a caspase 3/7 specific luminogenic substrate on U87MG cells treated with DT-EGF (150ng ml−1), TRAIL (2ng ml−1), DT-EGF (150ng ml−1) + TRAIL (2ng ml−1), and TRAIL (250ng ml−1) (mean +/− SEM from 3 replicates). (D) Effector caspase activity was measured using a caspase 3/7 specific luminogenic substrate on U87MG cells treated for 6 hours with DT-EGF (150ng ml−1), TRAIL (20ng ml−1), 0 (DT-EGF (150ng ml−1) + TRAIL (20ng ml−1)), 6 (pretreat with DT-EGF (150ng ml−1) for 6 hours then treat with TRAIL (20ng ml−1)), 24 (pretreat with DT-EGF (150ng ml−1) for 24 hours then treat with TRAIL (20ng ml−1)), (mean +/− SEM from 3 replicates).

DT-EGF/TRAIL synergy occurs through depletion of FLIP

Although the maximum amount of caspase activity was similar, there was a delay in caspase 3/7 activation with the combination of low dose TRAIL and DT-EGF compared to high doses of TRAIL alone (Figure 3C). This suggests that the ability of DT-EGF to stimulate TRAIL-induced caspase activation takes several hours to be manifested. To test this hypothesis, we pre-treated cells with DT-EGF for 6 or 24 hours prior to low dose TRAIL (20ng/ml) treatment for 6 hours. This resulted in an increase in caspase 3/7 activity at the 6 hour time point compared to treating cells with the combination of drugs at the same time (Figure 3D) showing that the delay in caspase activation that occurs with the combination treatment can be overcome if DT-EGF is present for six hours prior to TRAIL treatment. Because DT-EGF inhibits protein synthesis [7], we hypothesized that the molecular mechanism by which the time dependent stimulation of TRAIL induced caspase activation is achieved is through the turnover of a protein that inhibits TRAIL receptor signaling. The two strongest candidates for such a protein are the anti-apoptotic proteins FLIP and XIAP, which have relatively short half-lives and which can both inhibit TRAIL induced apoptosis.

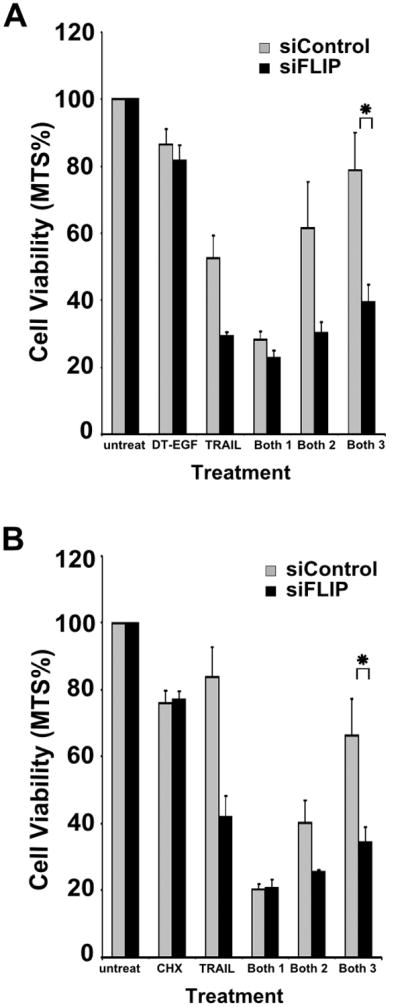

Treatment with DT-EGF, or the combination of DT-EGF and a low dose of TRAIL (2ng/ml) caused depletion of both FLIP and XIAP as determined by western blotting (Figure 4A). Interestingly, the combination of the drugs depleted XIAP further, but did not deplete FLIP any more than DT-EGF alone due to the fact that DT-EGF depletes FLIP levels essentially completely on its own. To test if depletion of these anti-apoptotic proteins is necessary for synergy, we used siRNA to knock down FLIP and XIAP levels (Figure 4B) then exposed the cells to varying doses of DT-EGF in combination with a low dose of TRAIL (2ng/ml). If depletion of the anti-apoptotic proteins is not responsible for DT-EGF's ability to stimulate TRAIL-induced apoptosis, then the amount of cell death for any given dose of DT-EGF plus TRAIL should be similar whether or not the anti-apoptotic protein was knocked down. Conversely, if depletion of the anti-apoptotic protein is responsible for synergy, we should find that, with limiting doses of DT-EGF, the addition of siRNA against the relevant protein should increase cell death to a level similar to that observed with high dose DT-EGF plus TRAIL. Figure 4C shows that siRNA against XIAP does not cause additional death in cells treated with TRAIL and either high (150ng/ml) or lower (10ng/ml, 2ng/ml) doses of DT-EGF. These data suggest that although DT-EGF treatment causes a depletion of XIAP levels, this is not a major mechanism for the synergy with TRAIL. However, when we treated cells with lower (10ng/ml, 2ng/ml) doses of DT-EGF, FLIP depletion was able to stimulate cell death to a level that is equivalent to high dose DT-EGF (150ng/ml) plus TRAIL (2ng/ml) (Figure 4C). To test if the mechanism requires the catalytic activity of DT, we used a chemical inhibitor (DPQ) of the ADP-ribosylation activity of DT. When the catalytic activity of the toxin was inhibited, potentiation of TRAIL-induced killing only occurred when FLIP levels were depleted with siRNA (data not shown) indicating that the inhibition of protein synthesis is required for DT-EGF to have these effects. We repeated these experiments using a chemical protein synthesis inhibitor, cycloheximide (chx) and found that here too, synergy was associated with depletion of FLIP rather than XIAP (Figure 4D). As expected, DPQ had no effect on chx-induced effects (data not shown). To test if the same mechanism of synergy applied in another GBM cell line, we repeated the FLIP knockdown experiments with 42MGBA cells. Figure 5 shows that FLIP knockdown increased TRAIL induced killing with low doses of DT-EGF (Figure 5A) or chx (Figure 5B) such that the total amount of cell death was equivalent to that achieved with high dose DT-EGF or chx. Therefore in both GBM cell types, FLIP downregulation is able to mimic the synergistic effect of DT-EGF in promoting TRAIL-induced apoptosis.

Figure 4. DT-EGF potentiates TRAIL by depleting FLIP.

(A) Western blot analysis of FLIP and XIAP protein levels in U87MG cells treated with DT-EGF (150ng ml−1), TRAIL (2ng ml−1), and Both (DT-EGF(150ng ml−1) and TRAIL (2ng ml−1)). (B) U87MG cells treated with siRNA targeting XIAP or FLIP for 48 and 72 hrs were harvested and western blot analysis was performed to determine XIAP or FLIP levels respectively. (C) Cells treated with control siRNAs or siRNA targeting XIAP or FLIP were treated with DT-EGF (150ng ml−1), TRAIL (250ng ml−1), Both 1 (DT-EGF (150ng ml−1) + TRAIL (2ng ml−1)), Both 2 (DT-EGF (10ng ml−1) + TRAIL (2ng ml−1)), and Both 3 (DT-EGF (2ng ml−1) + TRAIL (2ng ml−1)) and viability determined by MTS assay, data shows mean +/− SEM from 3 replicates, * indicates statistically significant difference by t-test p<0.05 between the sicontrol and siFLIP cells with low dose TRAIL. (D) Cells treated with siRNA's as in panel C then treated with with Chx (5 μg ml−1), TRAIL (250ng ml−1), Both 1 (Chx (5μg ml−1) + TRAIL (2ng ml−1)), Both 2 (Chx (0.15μg ml−1) + TRAIL (2ng ml−1)), and Both 3 (Chx (0.015μg ml−1) + TRAIL (2ng ml−1). Data shows mean +/− SEM from 3 replicates, * indicates statistically significant difference by t-test p<0.05 between the sicontrol and siFLIP cells with low dose TRAIL.

Figure 5. DT-EGF potentiates TRAIL by depleting FLIP in 42MGBA cells.

(A) Cells treated with siRNA targeting FLIP or control cell were treated with DT-EGF (150ng ml−1), TRAIL (250ng ml−1), Both 1 (DT-EGF (150ng ml−1) + TRAIL (2ng ml−1)), Both 2 (DT-EGF (10ng ml−1) + TRAIL (2ng ml−1)), and Both 3 (DT-EGF (2ng ml−1) + TRAIL (2ng ml−1)). The data represent mean +/− SEM from 3 replicates. (B) Cells treated with siRNA targeting FLIP or control cell were treated with Chx (5μg ml−1), TRAIL (250ng ml−1), Both 1 (Chx (5μg ml−1) + TRAIL (2ng ml−1)), Both 2 (Chx (0.15μg ml−1) + TRAIL (2ng ml−1)), and Both 3 (Chx (0.015μg ml−1) + TRAIL (2ng ml−1)). The data represent mean +/− SEM from 3 replicates.

Discussion

Effective anti-cancer treatments usually involve combinations of drugs and it is generally thought that such combinations may be better if they involve agents that work by different mechanisms. Therefore, because GBM cells are killed by DT-EGF through a non apoptotic cell death mechanism [31], it was particularly interesting to combine this agent in GBM cells with TRAIL receptor-targeted drugs, which directly activate the apoptosis machinery. Previous results from Kawakami et al suggest that IL-13 cytotoxin kills GBM cells in a caspase dependent manner [34, 35] and, our studies [31] showed that although DT-EGF kills GBM cells in a non-apoptotic manner unless autophagy is blocked, it kills epithelial tumor cells by caspase-dependent apoptosis. We also previously showed that a DT-GMCSF toxin kills different AML cell lines by different mechanisms [36]. Together, these data indicate that the mechanism of targeted toxin-induced cell death differs for different cancer cells. Thus, combining targeted toxins with apoptosis inducers may also allow regulation of the mechanism of cell death and this may be especially important in those cases where non-apoptotic death is the preferred mechanism by which the toxin kills. Our results show that the combination of DT-EGF and TRAIL results in synergistic tumor cell killing in vitro and more effective inhibition of tumor growth (which is at least an additive effect) in vivo. Unlike with DT-EGF alone, the combination caused high levels of caspase activity such that a low dose of TRAIL in the presence of DT-EGF was as effective (albeit after a delay) at activating caspases as a dose of TRAIL that is 75 times higher. The delay in caspase activation with the combination treatment relative to high dose TRAIL alone was due to the time required for down-regulation of anti-apoptotic proteins, the most important of which is FLIP indicating that the mechanism of synergy is through the protein synthesis inhibition effects of the targeted toxin leading to depletion of this inhibitor of TRAIL receptor signaling. Our previous work showed that DT-EGF's ability to induce autophagy was responsible for blocking caspase activation in GBM cells [31] however, this effect clearly did not block the ability of TRAIL receptor agonists to activate caspases. Consistent with this idea, autophagy can prevent apoptosis in response to various activators of the intrinsic caspase activation pathway but is less effective at inhibiting death receptor-induced caspase activation [37]. Inhibition of DT-EGF-induced autophagy might further stimulate the ability of TRAIL receptor agonists to activate apoptosis [38]. It has also been demonstrated that bispecific targeting of the toxin can significantly increase efficacy- for example GBM are more effectively killed and a broader selection of tumor cells can be targeted by a DT molecule that is fused to both EGF and IL13 ligands than is achieved by targeting either receptor alone [39]. We anticipate that combining with TRAIL receptor-targeted drugs would further enhance tumor killing with such improved targeted toxins too.

Clinical studies with another EGFR-targeted cytotoxin in GBM patients have produced mixed results. In a recent study, it was found that the EGFR-targeted toxin TP-38 was well tolerated at effective doses and there were some encouraging radiographic responses; however neurologic toxicities were observed and the authors concluded that there were limitations caused by inconsistent and ineffective infusion in many patients [40]. Thus, if we could maintain or increase the potency of EGFR-targeted cytotoxins while decreasing the normal tissue toxicity, it might be possible to combine this with improvements in the delivery method to make this a more viable therapy. One way to achieve this goal is through combination therapy with lower doses of EGFR-targeted cytotoxin combined with another agent that synergizes with it. Ideally, the other agent should be something that itself does not target normal tissue. Because TRAIL has been shown to be unable to kill normal astrocytes while retaining sensitivity in malignant glioma cells [41] and, in clinical studies for other tumor types, TRAIL Receptor-targeted agents have had very low toxicity [19], combination therapy with EGFR-targeted toxin and TRAIL Receptor agonists may allow this kind of strategy to be developed. As with targeted toxins [6], brain tumors can be treated with TRAIL (or antibodies that activate TRAIL receptors) using convection enhanced delivery [42], thus we suggest that combining these agents may provide a more effective way to treat brain tumors than can be achieved with either agent alone. Moreover, because the half-life of the agonistic TRAIL receptor antibodies in humans is much greater than that of TRAIL [18], our data indicate the value of understanding of the mechanism of synergy with other agents such as DT-EGF. For example, in vivo, we might expect that sequencing of the agents would be valuable and pre-treatment with DT-EGF would be particularly important when TRAIL is used but perhaps less important if an antibody was used. In conclusion, these studies provide a mechanistic rationale for combination treatments with TRAIL receptor agonists and targeted toxins to treat brain tumors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Manuel Morena and Lisa Hines for assistance with the animal experiments. Supported by National Institutes of Health grant CA111421 (A.T.).

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polednak AP, Flannery JT. Brain, other central nervous system, and eye cancer. Cancer. 1995;75:330–337. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950101)75:1+<330::aid-cncr2820751315>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleihues P, Louis DN, Scheithauer BW, Rorke LB, Reifenberger G, Burger PC, Cavenee WK. The WHO classification of tumors of the nervous system. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:215–225. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.3.215. discussion 226-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanzawa T, Ito H, Kondo Y, Kondo S. Current and Future Gene Therapy for Malignant Gliomas. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2003;2003:25–34. doi: 10.1155/S1110724303209013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thorburn A, Thorburn J, Frankel AE. Induction of apoptosis by tumor cell-targeted toxins. Apoptosis. 2004;9:19–25. doi: 10.1023/B:APPT.0000012118.95548.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pastan I, Hassan R, Fitzgerald DJ, Kreitman RJ. Immunotoxin therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:559–565. doi: 10.1038/nrc1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes RK. Biology and molecular epidemiology of diphtheria toxin and the tox gene. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(1):S156–167. doi: 10.1086/315554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morimoto H, Bonavida B. Diphtheria toxin- and Pseudomonas A toxin-mediated apoptosis ADP ribosylation of elongation factor-2 is required for DNA fragmentation and cell lysis and synergy with tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Immunol. 1992;149:2089–2094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kageyama A, Kusano I, Tamura T, Oda T, Muramatsu T. Comparison of the apoptosis-inducing abilities of various protein synthesis inhibitors in U937 cells. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2002;66:835–839. doi: 10.1271/bbb.66.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakada M, Nakada S, Demuth T, Tran NL, Hoelzinger DB, Berens ME. Molecular targets of glioma invasion. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:458–478. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6342-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu TF, Cohen KA, Ramage JG, Willingham MC, Thorburn AM, Frankel AE. A diphtheria toxin-epidermal growth factor fusion protein is cytotoxic to human glioblastoma multiforme cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1834–1837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu TF, Hall PD, Cohen KA, Willingham MC, Cai J, Thorburn A, Frankel AE. Interstitial diphtheria toxin-epidermal growth factor fusion protein therapy produces regressions of subcutaneous human glioblastoma multiforme tumors in athymic nude mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:329–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall WA, Rustamzadeh E, Asher AL. Convection-enhanced delivery in clinical trials. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;14:e2. doi: 10.3171/foc.2003.14.2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall WA, Sherr GT. Convection-enhanced delivery: targeted toxin treatment of malignant glioma. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;20:E10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashkenazi A, Herbst RS. To kill a tumor cell: the potential of proapoptotic receptor agonists. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1979–1990. doi: 10.1172/JCI34359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnstone RW, Frew AJ, Smyth MJ. The TRAIL apoptotic pathway in cancer onset, progression and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:782–798. doi: 10.1038/nrc2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thorburn A. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) pathway signaling. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:461–465. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31805fea64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camidge DR. The potential of death receptor 4- and 5-directed therapies in the treatment of lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2007;8:413–419. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2007.n.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashkenazi A. Directing cancer cells to self-destruct with pro-apoptotic receptor agonists. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2008;7:1001–1012. doi: 10.1038/nrd2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin Z, El-Deiry WS. Distinct signaling pathways in TRAIL- versus tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8136–8148. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00257-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thorburn A, Behbakht K, Ford H. TRAIL receptor-targeted therapeutics: Resistance mechanisms and strategies to avoid them. Drug Resist Updat. 2008;11:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irmler M, Thome M, Hahne M, Schneider P, Hofmann K, Steiner V, Bodmer JL, Schroter M, Burns K, Mattmann C, Rimoldi D, French LE, Tschopp J. Inhibition of death receptor signals by cellular FLIP. Nature. 1997;388:190–195. doi: 10.1038/40657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkinson JC, Wilkinson AS, Scott FL, Csomos RA, Salvesen GS, Duckett CS. Neutralization of Smac/Diablo by inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs) A caspase-independent mechanism for apoptotic inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51082–51090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dancey JE, Chen HX. Strategies for optimizing combinations of molecularly targeted anticancer agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:649–659. doi: 10.1038/nrd2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thorburn J, Horita H, Redzic J, Hansen K, Frankel AE, Thorburn A. Autophagy regulates selective HMGB1 release in tumor cells that are destined to die. Cell Death Differ. 2008 doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu TF, Willingham MC, Tatter SB, Cohen KA, Lowe AC, Thorburn A, Frankel AE. Diphtheria Toxin-Epidermal Growth Factor Fusion Protein and Pseudomonas Exotoxin-Interleukin 13 Fusion Protein Exert Synergistic Toxicity against Human Glioblastoma Multiforme Cells. Bioconjug Chem. 2003;14:1107–1114. doi: 10.1021/bc034111+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Komatsu N, Oda T, Muramatsu T. Involvement of both caspase-like proteases and serine proteases in apoptotic cell death induced by ricin, modeccin, diphtheria toxin, and pseudomonas toxin. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1998;124:1038–1044. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horita H, Frankel AE, Thorburn A. Acute myeloid leukemia-targeted toxins kill tumor cells by cell type-specific mechanisms and synergize with TRAIL to allow manipulation of the extent and mechanism of tumor cell death. Leukemia. 2008;22:652–655. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorburn J, Frankel AE, Thorburn A. Apoptosis by leukemia cell-targeted diphtheria toxin occurs via receptor-independent activation of Fas-associated death domain protein. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:861–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thorburn J, Frankel AE, Thorburn A. Regulation of HMGB1 release by autophagy. Autophagy. 2009;5:93–95. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.2.7552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorburn J, Horita H, Redzic J, Hansen K, Frankel AE, Thorburn A. Autophagy regulates selective HMGB1 release in tumor cells that are destined to die. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:175–183. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chou TC. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:621–681. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawakami M, Kawakami K, Puri RK. Intratumor administration of interleukin 13 receptor-targeted cytotoxin induces apoptotic cell death in human malignant glioma tumor xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:999–1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawakami M, Kawakami K, Puri RK. Tumor regression mechanisms by IL-13 receptor-targeted cancer therapy involve apoptotic pathways. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:45–52. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horita H, Frankel AE, Thorburn A. Acute-myeloid-leukemia-targeted toxins kill tumor cells by cell-type-specific mechanisms and synergize with TRAIL to allow manipulation of the extent and mechanism of tumor cell death. Leukemia. 2008;22:652–655. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ravikumar B, Berger Z, Vacher C, O'Kane CJ, Rubinsztein DC. Rapamycin pre-treatment protects against apoptosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1209–1216. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han J, Hou W, Goldstein LA, Lu C, Stolz DB, Yin XM, Rabinowich H. Involvement of protective autophagy in TRAIL resistance of apoptosis-defective tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:19665–19677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710169200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stish BJ, Oh S, Vallera DA. Anti-glioblastoma effect of a recombinant bispecific cytotoxin cotargeting human IL-13 and EGF receptors in a mouse xenograft model. J Neurooncol. 2008;87:51–61. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9499-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sampson JH, Akabani G, Archer GE, Berger MS, Coleman RE, Friedman AH, Friedman HS, Greer K, Herndon JE, 2nd, Kunwar S, McLendon RE, Paolino A, Petry NA, Provenzale JM, Reardon DA, Wong TZ, Zalutsky MR, Pastan I, Bigner DD. Intracerebral infusion of an EGFR-targeted toxin in recurrent malignant brain tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10:320–329. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pollack IF, Erff M, Ashkenazi A. Direct stimulation of apoptotic signaling by soluble Apo2l/tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand leads to selective killing of glioma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1362–1369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saito R, Bringas JR, Panner A, Tamas M, Pieper RO, Berger MS, Bankiewicz KS. Convection-enhanced delivery of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand with systemic administration of temozolomide prolongs survival in an intracranial glioblastoma xenograft model. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6858–6862. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]