Abstract

When referring to named objects, speakers can choose either a name (mbira) or a description (that gourd-like instrument with metal strips); whether the name provides useful information depends on whether the speaker’s knowledge of the name is shared with the addressee. But, how do speakers determine what is shared? In 2 experiments a naïve participant (director) learned names for novel objects, then instructed another participant (matcher), who viewed 3 objects, to click on the target object. Directors learned novel names in 2 phases. First, the director and the matcher learned (shared) names either together or alone; second, the director learned (privileged) names alone. Directors typically used a name for items with shared names and a description for items with privileged names. When the director and matcher learned the names individually but with knowledge of what the other learned, directors were much more likely to use privileged names than when director and matcher learned shared names together. Experiment 1b separated effects of collaborative learning from partner-specific effects, showing collaborative learning experience with 1 person helps a speaker distinguish shared and privileged information with a new partner who has the same knowledge. Experiment 2 showed that partner-specific effects persisted even when semantic category was a reliable cue to which names were privileged. The results are interpreted as evidence that ordinary memory processes provide access to shared knowledge in real-time production of referring expressions and that shared experience when learning shared names provides a strong memory cue to the ground status of names.

Keywords: language production, common ground, reference, memory, shared experience

Language allows us to converse with others about the world as well as about our own thoughts and ideas. But conversational partners do not always share the same perspective or knowledge about the topic of conversation, and thus interlocutors need to be able to take their partner’s knowledge and perspective into account in deciding what to say and how to interpret what was said. One basic aspect of language where this knowledge is particularly relevant is when referring to a particular object or individual in the world. In recent years, following earlier pioneering work by Clark and Marshall (1978, 1981), definite reference has emerged as an important domain for studying perspective taking in conversation. A central question has been whether speakers and listeners distinguish between potential referents that are shared, that is referents that are in common ground, and potential referents that are known to only one of the interlocutors, that is referents that are in privileged ground. In this article, we report results from two experiments that investigated the role of shared experience in guiding the form of a speaker’s referring expressions. We begin with a brief review of the literature on perspective taking in comprehension and production.

Common Ground and Comprehension of Referring Expressions

There is now an extensive literature on perspective taking in comprehension. A series of studies beginning with Keysar, Barr, Balin, and Brauner (2000) have combined the visual world paradigm (Cooper, 1974; Tanenhaus, Spivey-Knowlton, Eberhard, & Sedivy, 1995) with referential communication tasks (Krauss & Weinheimer, 1966) in order to explore questions relating to perspective taking. In these studies, a confederate director and a naïve addressee are seated on opposite sides of an actual or virtual workspace containing a set of cubbyholes with objects in them. Addressees follow instructions from the speaker in order to put the objects in the correct locations. In these experiments, the contents of most of the cubbyholes are visible to both participants and thus are in common ground by virtue of physical co-presence (Clark & Marshall, 1981), but one or more of the cubbyholes is blocked so that the director cannot see the contents. Therefore, the contents of the blocked cubbyholes are in the addressee’s privileged ground. Addressees in the Keysar et al. (2000) study often made eye movements to an object that was in their privileged ground when it was a better referential fit for the speaker’s referring expression than potential referents in common ground. This result, along with results from similar studies (Keysar, Lin, & Barr, 2003), led Keysar, Barr, and colleagues to conclude that initial comprehension processes are egocentric. These results have since been qualified by evidence that when referential fit is controlled for, addressees make use of information about physical co-presence from the earliest moments of reference resolution (Brown-Schmidt, 2009b; Hanna & Tanenhaus, 2004; Hanna, Tanenhaus, & Trueswell, 2003; Heller, Grodner, & Tanenhaus, 2008; Nadig & Sedivy, 2002; but cf. Barr, 2008). Moreover, addressees are sensitive to aspects of utterance form that mark speaker knowledge (Brown-Schmidt, 2009b; Brown-Schmidt, Gunlogson, & Tanenhaus, 2008), for example, immediately interpreting an information-seeking question as referring to information in their privileged ground.

Brennan and colleagues (Brennan & Hanna, 2009; Metzing & Brennan, 2003) have also shown that addressees can use speaker-specific information when comprehending referring expressions. In their experiments, participants played a referential communication game where the speaker (a confederate) used consistent referring expressions for particular items. Later, participants played the referential communication game again with either the same speaker or a different speaker. Participants were slower to identify the target and searched the display more when the original partner used a referring expression that was different from the one used in the first part of the study, suggesting that participants store partner-specific information about the use of particular referring expressions. In a similar study that used prerecorded instructions, Kronmüller and Barr (2007) found that partner-specific effects do not affect the earliest moments of reference resolution, which they interpreted as support for egocentric initial comprehension. However, Brown-Schmidt (2009a) found early use of speaker-specific information when participants interacted with a live speaker, but late use when participants listened to prerecorded instructions as in the Kronmüller and Barr study.

In sum, then, the comprehension literature suggests that at least under some conditions, addressees are able to make use of information about ground from the earliest moments of processing. Galati and Brennan (2010) proposed that simple “one-bit” representations of partner knowledge could underlie these abilities; when information about the conversational partner’s knowledge or perspective is clear and easy to compute, as in cases where there are only two alternatives relating to the partner’s knowledge or perspective (e.g., My partner can see this object or not), it can be easily used. It is unclear, however, whether the representations of partner knowledge used in conversation can truly be captured with only a single bit of information or whether a more probabilistic approach that allows for graded representations and integration of multiple sources of evidence is required, as proposed by Hanna et al. (2003) and Brown-Schmidt (2011).

Common Ground and Production of Referring Expressions

In contrast to the extensive literature on comprehension, the literature on perspective taking in reference generation is relatively sparse. There are reasons to believe that perspective taking might be different, or at least more challenging, for speakers. Unlike addressees, speakers cannot simply focus on common ground when producing an utterance; speakers must keep track of the shared versus privileged distinction in order to contribute new information to the conversation in a way that the addressee can understand. Speakers also have to balance the cognitive demands in formulating and producing utterances against potentially resource-demanding considerations of computing what knowledge is shared with the listener and what is privileged. Thus, it might be more difficult for a speaker to consider information about ground in planning a referring expression than it is for an addressee to use the same information in understanding a referring expression.

Indeed, several studies suggest that there are limits on how effectively speakers use information about shared knowledge. Horton and Keysar (1996) and Wardlow Lane, Groisman, and Ferriera (2006) examined speakers’ use of prenominal modification when both members of a contrast set (e.g., a large and a small circle) are only visible to the speaker. In Horton and Keysar’s study, the speaker was required to refer to a circle in a display, which also contained another bigger circle. This bigger circle could be visible to both participants, and thus in common ground, or visible only to the speaker, and thus in privileged ground. On the assumption that the prenominal modification is restrictive, speakers should modify only when it is necessary for the addressee to uniquely identify the referent. Horton and Keysar found that speakers used modification on 24% of the trials when the bigger circle was in privileged ground and did so even more when they were under time pressure. Similarly, Wardlow Lane, et al. found that speakers increased modification rates when referring to an object that contrasted in size to a hidden object compared to when the hidden object was not a contrast member. Moreover, speakers modified even more frequently when they were instructed to conceal the identity of the hidden object. These results suggest that speakers may ignore their addressee’s perspective during initial utterance planning. It is important to note, however, that the modification rates in these studies are considerably lower than typical modification rates when both objects are in common ground (Brown-Schmidt & Tanenhaus, 2006; Carbary, Frohning, & Tanenhaus, 2010; Sedivy, 2003), suggesting that information about ground might indeed be influencing modification.

Although modification based on contrast can provide important insights into a speaker’s use of shared knowledge in reference generation, it also has some limitations. A strong determinant of whether a speaker chooses to use prenominal modification is whether her attention is drawn to both the intended referent and a potential contrast member (Brown-Schmidt & Tanenhaus, 2006), and the experiments we have just reviewed draw attention to the contrasting pair of objects by design. In addition, during collaborative tasks the referential domains of interlocutors become closely aligned (Brown-Schmidt & Tanenhaus, 2008; Richardson, Dale, & Kirkham, 2007; Richardson, Dale, & Tomlinson, 2009). Therefore, speakers typically share the same referential domain as their interlocutor.

A complementary approach is to examine when speakers choose to use names and descriptions. When referring to an object with a name, speakers need to decide whether to use a name (e.g., mbira) or a description (e.g., that gourd-like instrument with metal strips). It would clearly be more efficient for the speaker to retrieve a well-learned name rather than to expend the effort to plan a more complex, less precise description, but for reference to be successful, the addressee must also know the name. Whether a speaker chooses to use a name or a description is a useful domain, then, for investigating speakers’ abilities for perspective taking and representing common ground.

One important question regards the nature of the representations speakers use to keep track of what is shared and what is privileged with respect to their addressee. Clark and Marshall (1978) proposed that interlocutors tracked common ground by constructing a record of partner-specific experiences, which they termed a reference diary. When considering whether to use a name, a speaker could search the reference diary for evidence about shared experience, which might suggest whether the addressee was likely to know the name. Wu and Keysar (2007) argued that instead of tracking whether individual pieces of information are shared with a particular addressee, which could prove to be prohibitively difficult in at least some conversational settings, speakers might instead use a global information overlap heuristic, where the overall amount of information shared by a speaker and addressee serves as a cue to whether a particular item is shared. Using this heuristic, speakers could safely assume that they can rely on their own knowledge when the overlap in information between themselves and their addressee is extensive.

Wu and Keysar (2007) tested the overlap hypothesis using a referential communication task where pairs of naïve participants learned novel names for novel shapes. They had either high information overlap and learned 18 of the 24 names together or low overlap and learned only 6 of the 24 names together. The remaining names were taught only to the speaker, making them privileged information. During a subsequent matching task in which speakers had to instruct their partner to select a target shape from an array of three shapes, speakers used more names overall in the high overlap condition, which Wu and Keysar interpreted as support for the information overlap heuristic. However, speakers used substantially more names (rather than descriptions) when a name was shared than when it was privileged. Thus, speakers were in fact storing and retrieving some item-specific information about what knowledge was shared and what was privileged.

Heller, Gorman, and Tanenhaus (2012) used the same paradigm as Wu and Keysar (2007) and found a similar pattern of name use. However, a more detailed analysis of the form of the speakers’ utterances demonstrated that even when using a privileged name, speakers were sensitive to whether that name was privileged or shared. When speakers used a privileged name, it was typically followed by a description, uttered in the same prosodic phrase as the name, an utterance type they labeled as name-then-description. In contrast, when speakers used a shared name, they typically uttered only the name without any description, then waited for a response, an utterance type they labeled as name-alone. Heller et al. suggested that speakers might use the name-then-description form as a way to teach privileged names to their addressee. However, there are other alternatives. Speakers might begin the utterance with the name because it is more available than the description, thus allowing more time for utterance planning or because they have some uncertainty about the ground status of the name. It might also be used to probe the addressee’s knowledge, although that use of the form would presumably be marked by a distinctive pitch accent on the name. Regardless of why speakers use the name-then-description form, these results suggest that speakers were indeed tracking the shared versus privileged status of the individual items.

Heller et al.’s (2012) results raise the question of how speakers are so adept at storing and accessing information about shared information when choosing whether to use a name or a description. A plausible framework for addressing this question was proposed by Horton and Gerrig (2005a, 2005b). They argued that information about common ground is represented as a by-product of ordinary memory processes, which contain context-specific episodic traces. They suggested that when speakers want to refer to something, they activate episodic memories for that object. If the episodic memory links the name for the referent with their addressee, the speaker uses that name. Using a paradigm in which participants are given training that leads them to associate particular item categories with particular partners, Horton and Gerrig (2005b) found stronger effects of audience design, as measured by speed of picture naming, when partner-specific associations were easier to distinguish in memory. Horton (2007) demonstrated that the partner-specific priming found in a similar task was not driven by explicit recall of partner-specific associations; though participants in his study were quite good, overall, at keeping track of which partner a particular item was learned with, explicit recall was not correlated with higher levels of partner-specific priming for the names of those items.

Recent results from the spoken word recognition literature also suggest that speakers might indeed have automatic access to speaker-specific episodic traces for names. Goldinger (1998) proposed that the representation of a word includes speaker-specific information. He summarized evidence from several paradigms in which after exposure to a word, addressees perform better in recognition tasks when a word is spoken by the same speaker at test compared to when it is spoken by a different speaker. Creel and her colleagues have further demonstrated that speaker-specific information is accessed during the earliest moments of spoken word recognition (Creel, Aslin, & Tanenhaus, 2008; Creel & Tumlin, 2011; but cf. McLennan & Luce, 2005).

Investigating the Implicit Memory Hypothesis

The current experiments focus on the role of shared experience in real-time production of referring expressions, using the paradigm introduced by Wu and Keysar (2007). If speakers depend primarily on partner-specific episodic memory traces, shared experience with their addressee should play a critically important role in speakers’ ability to distinguish between shared and privileged information. When the name for an item is learned together, it should be easy to know that it is shared due to a rich episodic representation from the learning environment that links particular information with the addressee. This episodic representation would be missing if, instead of establishing common ground via shared learning experience, interlocutors were simply told about what their partner knows and doesn’t know. Shared experience could provide powerful cues to shared knowledge, but this cue to common ground is also somewhat restricted in natural settings. Often shared knowledge is established via community membership, where interlocutors do not have direct shared experience with each other but rather infer that knowledge due to shared experiences with other people who are likely to have similar knowledge as their interlocutor. When and how interlocutors are able to make these inferences are poorly understood, but some type of generalization between partners and/or categories of knowledge would be required.

We report two experiments that examined the role of shared experience and categorical information structure in determining knowledge-appropriate referring expressions with names. Based on the results of Heller et al. (2012), we focused our analyses on speakers’ use of the name-alone form, as it is most diagnostic of when speakers believe a name to be shared, and the name-then-description form, since this is the most common form when a name is used for a privileged item.

In Experiment 1, we tested the hypothesis that interlocutors need to engage in shared experiences with their addressee in order for speakers to easily distinguish between shared and privileged information. In Experiment 1a, we used the Wu and Keysar (2007) paradigm to compare the effects of having shared experience as a basis for establishing common ground with being told that a partner learned the same names separately. We predicted that even though speakers would know which names were shared and privileged in both conditions, they would be far more likely to generate knowledge-appropriate referring expressions in the shared learning condition. In Experiment 1b, we examined whether shared experience needs to be partner specific, or whether shared experience with another partner also provides a useful memory cue when speakers are told that their addressee learned the same names as the other partner. Experiment 1b compared the results of Experiment 1a with an additional condition where the speaker did not have representations established through shared experience with her addressee but instead had shared experience with another partner.

In Experiment 2, we manipulated the category structure of the information to determine whether speakers rely on partner-specific knowledge even when the category structure of privileged and shared knowledge provides a reliable top-down memory cue.

Experiment 1a

In this experiment, participants learned novel names for a collection of monsters and robots. In one condition, the director and matcher learned the names for all shared items together, and the director learned the names for privileged items alone. In the other condition, the director and matcher learned shared items separately, and the director learned privileged items alone; in this condition, participants were still aware of which items they both had learned and which only the director had learned, but would not have the rich episodic representations associated with having learned shared items together with their addressee. We hypothesized that directors use of knowledge appropriate names would be strongly enhanced in the shared learning condition.

Method

Participants

Twenty-six pairs of native English speakers from the University of Rochester community were paid for their participation. Five additional pairs participated but were excluded from analysis due to experimenter error (three pairs), equipment failure (one pair), or failure to follow task instructions (one pair). Each pair knew each other prior to the experiment and chose to participate together. One participant was randomly assigned the role of director and the other the role of matcher. Half of the pairs were assigned to the shared experience condition, and half were assigned to the alone condition.

Materials

Eighteen novel clipart images of monsters and six of robots from clipart.com were used for the training phase of this experiment (see Figure 1 for sample items). Each was randomly assigned an artificial name (e.g., Grampent, Molget) from those used by Wu and Keysar (2007). The monsters and robots were evenly distributed between shared and privileged items such that there were nine monsters and three robots used for each type. An additional 30 images of monsters and robots were used as distractor images or for practice trials during testing.

Figure 1.

Sample of monsters (top) and robots (bottom).

Procedure

Training phase

The names of the 24 items were taught to the participants by an experimenter using 5″× 8″ flashcards of each item. There were four training blocks, which contained six items each. For each item, the experimenter presented a card showing the picture of that item, said the name, and waited for the participant(s) to repeat the name before proceeding to the next card. After going through the six items in the block twice, the experimenter just presented the card and waited for the participant(s) to name the shape. The experimenter then said the name or corrected any errors if the participant(s) could not name the item correctly. The experimenter repeated this procedure until the participant(s) could name all six items flawlessly, and then moved on to the next block. When trained together, both participants needed to perform flawlessly before moving on. After all of the blocks had been learned, the experimenter had the participants name the shapes in each block a final time before proceeding to the testing phase. For each block, the final review was conducted individually or together, replicating the original training condition.

In the shared experience condition, the two participants sat together across a table from the experimenter during the first two blocks and were allowed to freely converse with each other, and during the third and fourth blocks, the director learned the remaining names alone with the experimenter while the matcher played a nonlinguistic computer game and listened to instrumental music over headphones.

In the alone condition, the participants were told that the director would learn the names for some of the items, then the matcher would learn the names for the same items, and then the director would learn the names for the remaining items, which would not be subsequently taught to the matcher. As in the shared experience condition, when participants were not learning the names, they played a nonlinguistic computer game while listening to instrumental music over headphones.

Testing phase

During the testing phase, participants played a referential communication game. Participants sat in front of two different computers and were free to converse over a network, but they could not see each other. The director was presented with one item: shared (items both participants learned), privileged (items only the director learned), or new (unlearned items, of which half were monsters and half were robots). The director instructed the matcher, who saw three items, to click the target item “as quickly and accurately as possible.” The matcher’s display contained the target item, another item from the training set, and one unnamed item from the set of distractor items.

Trials ended when the matcher clicked on any item: If the matcher clicked the wrong item, an error sound was heard, but participants could not correct the error. The referential communication task had two practice trials followed by 24 experimental trials, nine that were shared (six monsters and three robots), nine that were privileged (six monsters and three robots), and six that were new (three monsters and three robots).

The participants’ utterances were recorded to a computer and later transcribed by the experimenter.

Posttests

After completing the referential communication task, the director completed two additional tasks. First, directors were presented with each of the 24 items they had learned during training and had to determine whether both participants learned the name of that item or if only they had learned it. The computer presented the items one at a time in random order, and the director had to click learned together or learned alone.

Directors then completed a task where they had to name each of the shapes. The computer presented the items one at a time in random order, and the director had to say its name, which was recorded. A response was coded as correct when no more than one phoneme was incorrect.

Results

Task performance

In the referential communication task, matchers clicked on the correct item on 99% of the trials. Directors’ accuracy on the first posttest measured their ability to explicitly distinguish between the items they and their partners both learned and those they learned alone. Overall, directors were quite good at distinguishing between shared and privileged names in both the shared experience (98%) and alone conditions (89%). Nonetheless, the difference between the shared experience and alone conditions was significant (β = 1.87, SE = 0.61, p < .01).1 Director’s accuracy on the second posttest, which tested their memory for the names, was 81% and did not differ between conditions.

Directors’ utterances

We assigned the directors’ first turn of each trial to one of six categories: description-only (a description without using a learned name), name-in-description (a shared name used nonreferentially as part of the description; e.g., looks like Grampent), description-then-name (a description followed by a name), name-then-description (a name followed by a description), knowledge-query (asking if their partner knows the name), and name-alone (a name without any description of the item). We present the distribution for all forms in the figures, but we focus our statistical analyses on the name-alone and the name-then-description forms.

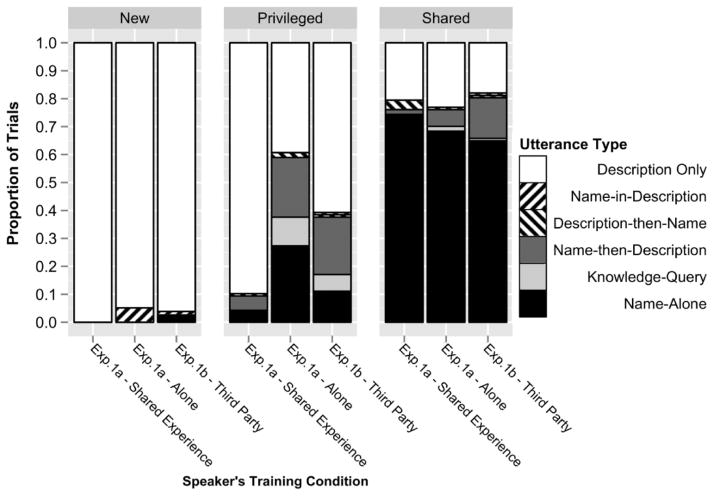

Each panel of Figure 2 shows the distribution of directors’ utterances for a particular type of trial (new, privileged, shared), and the left two bars of each panel compare the alone and shared experience conditions. For new items (left panel) in both conditions, directors almost exclusively used the description-only form, which is expected given that they did not learn names for these items. For privileged items (middle panel) and shared items (right panel), the shared experience condition replicates Heller et al. (2012): Directors rarely used names for privileged items (middle panel) but mainly used the name-then-description form when they did, and used the name-alone form frequently for shared items. There was no statistical difference between the training conditions in the use of the name-alone form for shared items (74% for shared experience; 68% for alone). However, for privileged items, directors used the name-alone form significantly more when they learned the shared shapes individually (4% for shared experience; 27% for alone).

Figure 2.

Experiments 1a and 1b: Each panel shows the distribution of directors’ utterances for new, privileged, and shared items for each training condition (alone, shared experience, and third party). Experiment 1a compared the alone and shared experience conditions, and Experiment 1b compared the alone, shared experience, and third party conditions. Exp. = experiment.

We analyzed the data using a multilevel logistic regression model that predicted the likelihood of an utterance form with trial type (shared, privileged), training type (shared experience, alone), and their interaction as fixed effects and with items and participants as random slopes and intercepts. When we predicted directors’ use of name-alone, there was a main effect of trial type (β = 2.00, SE = 0.28, p < .001) such that name-alone was used more for shared than privileged items; a main effect of training (β = 0.74, SE = 0.29, p < .01) such that name-alone was used more in the alone condition; and a significant interaction (β = 0.86, SE = 0.26, p < .001).

When we predicted directors’ use of name-then-description, there was a main effect of trial type (β = 1.22, SE = 0.35, p < .001) such that name-then-description was used more for privileged items than shared items, which is consistent with Heller et al. (2012). In addition, we found a main effect of training (β = 1.32, SE = 0.35, p < .001) such that name-then-description was used more in the alone condition.

Another notable difference in directors’ utterances when they do not have a shared learning experience with the matcher is that they sometimes used a knowledge-query form (e.g., Do you know Inta?). This form of utterance occurred in 10% of privileged-ground trials in the alone condition, whereas it never occurred in the shared experience condition in this experiment and in Heller et al. (2012).

Discussion

Regardless of whether common ground was established through shared learning experience or through being explicitly told of their partner’s knowledge, speakers used names more frequently for shared items than for privileged items. However, when common ground was not established via shared learning experience, speakers were far more likely to erroneously use names for privileged items and to be uncertain about their partner’s knowledge, as indicated by knowledge queries. They also were more likely to use the name-then-description form for items in privileged ground, which is consistent with the hypothesis that the name-then-description form signals increased uncertainty about the ground status of a privileged name. Thus, shared learning experience is an important factor in establishing representations of common ground that allow speakers to appropriately recognize items as privileged.

These results are consistent with the hypothesis that implicit partner-specific memory traces play a crucial role in guiding speakers’ choice of referring expressions. There is, however, another possible explanation for the pattern of results in Experiment 1a. The collaborative learning in the shared experience condition might indeed provide better context cues that distinguish between shared and privileged information, but those cues might not depend on shared learning with the same partner.

In the shared experience condition, the episodes in which shared items were learned might be more easily distinguishable in memory from those in which privileged items were learned because the learning experience was highly interactive. For instance, many pairs collaboratively created memory cues to help remember the names. If the memory cues created by the richer learning experience transfer to a new partner that shares a similar experience, then partner-specific memories, per se, might play a more limited role than the results of Experiment 1a would suggest. In addition, if shared experience transfers to a third party, then this would help provide a memory-based explanation for some aspects of common ground based on community membership.

Experiment 1b

Experiment 1b compared the results from Experiment 1a with an additional condition that was designed to examine the effects of shared learning experience with a different partner. Here, directors in the third party condition learned names alongside another individual as in the shared experience condition, but directors then completed the referential communication task with a different matcher, who learned the shared items by him- or herself as in the alone condition. In the third party condition, the shared learning experience with the third party corresponded to the common ground they had with the matcher but any speaker-specific memory associations would have to be generalized to the new partner.

Method

Participants

Thirteen trios of native English speakers from the University of Rochester community were paid for their participation. Two additional trios participated but were excluded from analysis due to experimenter error (one trio) and failure to follow task instructions (one trio). All trios knew each other prior to the experiment and chose to participate together. One participant was randomly assigned the role of director, another the role of third party, and the other the role of matcher.

Materials

The materials were identical to those used for Experiment 1a.

Procedure

The procedure was a blend of the alone and shared experience conditions from Experiment 1a. The procedure for matchers was identical to the alone condition; they learned shared items separately from the director and were aware of what the other had been taught. When the director learned the shared items, his or her training was conducted with the third participant in the same way as the shared experience condition; the directors were alone when they learned privileged items. As in the previous experiments, when participants were not learning the names, they played a nonlinguistic computer game while listening to instrumental music over headphones.

Results

The results of Experiment 1b will be called the third party condition and are compared to the shared experience and alone conditions of Experiment 1a.

Task performance

Again, matchers’ task performance was excellent (they clicked on the correct item on 99% of the trials). Directors’ accuracy on the first posttest (distinguishing between items both they and their partners knew and those only they learned) was 94% for the third party condition, which was significantly better than the alone condition (89%; β = 0.86, SE = 0.43, p < .05) but did not differ from the shared experience condition (98%; p = .14). This suggests that the collaborative experience did, in fact, create stronger memory traces than the alone condition. Directors’ accuracy on the second posttest (memory for the items’ names) was 85% for the third party condition, which did not significantly differ from the alone and shared experience conditions (79% and 84%, respectively).

Directors’ utterances

Figure 2 shows the distribution of directors’ utterances for the third party condition in addition to the alone and shared experience conditions from Experiment 1a. Inspection of Figure 2 suggests that the directors’ behavior in the third party condition differs from both the shared experience and alone conditions for privileged items. Directors used the name-alone form less in the third party condition than in the alone condition, but used the name-then description form more than in the shared experience condition.

We conducted statistical analyses using multilevel logistic regression models that predicted the likelihood of a particular utterance form with trial type (shared, privileged), training type (shared experience, third party, alone), and their interaction as fixed effects and with items and participants as random slopes and intercepts, unless stated otherwise. The three levels of training type were dummy coded as comparisons between the third party condition and the alone condition and between the third party condition and the shared experience condition.

Across all three conditions, directors used the name-alone form more for shared items than for privileged items (β = 2.06, SE = 0.25, p < .001). For shared items (the right panel), there was no significant difference in the use of the name-alone form between the three training conditions. For privileged items (the middle panel), directors’ use of the name-alone form (an error) in the third party condition (11%) was numerically and statistically less than in the alone condition (27%; β = 0.97, SE = 0.47, p < .05) and numerically greater than in the shared condition (4%). Statistically, however, the third party condition did not differ from the shared experience condition (p = .21). Because differences in use of the name-alone form occurred primarily with privileged items, we conducted an additional multilevel logistic regression model for only privileged items. This analysis confirmed that directors’ use of name-alone in the third party condition was less than in the alone condition (β = 0.91, SE = 0.46, p < .05) but did not differ from the shared experience condition (p = .14). In sum, then, use of name-alone forms does not reliably distinguish the third party and the shared conditions.

As in Experiment 1a and Heller et al. (2012), overall the directors used the name-then-description form more for privileged items than for shared items (β = 0.88, SE = 0.24, p < .001). Directors’ use of this form for privileged items varied between the training conditions. For privileged items, directors used the name-then-description form more frequently in the third party condition (20%) compared to the shared experience condition (5%; β = 2.11, SE = 0.75, p < .005). However, use of the name-then-description form in the third party condition did not differ from the alone condition (21%; p = .98).

Taken together, then, these results suggest that shared experience with a third party provides memory cues that allow directors to track shared and privileged information, more effectively than when there is no collaborative experience but less effectively than when experience is shared.

Discussion

In the third party condition, when directors learned information with a partner who was not the addressee in the matching task but whose knowledge corresponded to the addressee’s knowledge, they were equally good at avoiding the name-alone form for privileged names as directors in the shared experience condition. If we assume, following Heller et al. (2012), that the name-alone form indicates that the director believes that a name is shared, then collaborative experience provides information that will transfer to a new partner who the speaker believes shares similar experiences. This suggests that memory cues from shared learning help distinguish between shared and privileged knowledge even when that shared learning was with a different partner. This is one of the foundations of community membership.

However, the results also provide evidence that directors who learned with a third party are less certain about the status of privileged information than directors who learned with the same partner. For privileged items they used the name-then-description form more and also used the knowledge-query form—asking their partner if the partner knows a particular item—similar to directors in the alone condition. This suggests that (contrary to Heller et al., 2012) the name-then-description form might be used when the speaker has some degree of uncertainty about whether a name is shared. We return to this point in the general discussion. In sum, the memory information provided by third party experience is intermediate between that provided by learning alone and being told that an interlocutor shares one’s experience and having shared experience with that interlocutor.

Experiment 2

Experiment 1 established that shared experience can be a powerful cue to shared information, but these results may overestimate speakers’ ability to use common ground. It is possible that in the real world, tracking specific pieces of information is used only in special circumstances and usually interlocutors track information over domains of knowledge. For example, if a speaker knows that she and her addressee are both knowledgeable about knitting, but that only she knows much about gardening, that could help her decide whether she can use a specific name for a particular gardening implement. Knowledge of which categories are likely to be shared and which are likely to be privileged might take precedence over tracking specific experiences using the name for that implement with that partner. Thus we might be overestimating the effects of partner-specific memory in the previous studies because other cues are not available to speakers. Experiment 2 provided structured semantic categories that speakers could use instead of using shared experience to distinguish between shared and privileged items. If categorical knowledge is preferred for determining common ground status, names may be used infelicitously when some knowledge in a category is shared and some is privileged. Additionally, when an entire category is shared or privileged, this category information should improve speakers’ ability to distinguish shared and privileged names, since the category of a particular item could serve as a reliable cue to its ground status. However, the memory-trace hypothesis predicts that effects of category structure will be relatively weak compared to effects of shared experience, which creates rich partner-specific memory traces.

Heller et al. (2012) also attempted to use categorical knowledge in this way; however, they created categories based on phonological onsets. In one condition, privileged shapes all shared a/fl/onset. They found no effects of this category manipulation. However, in natural language there is a relatively weak mapping between form and meaning. Therefore, most cues to shared and privileged information will rely on semantic properties, which might more closely correlate with different categories of information such as gardening, knitting, or styles of music. Horton and Gerrig (2005a, 2005b) have found effects of this type of semantic category structure on speakers’ ability to distinguish between information shared with one of two matchers. Experiment 2 aimed to investigate whether this kind of structure can also override shared experience when distinguishing between shared and privileged information.

Method

Participants

Twenty pairs participated in Experiment 2. Three additional pairs participated but were excluded from analysis due to equipment failure.

Materials

The materials were identical to that of Experiment 1, but the distribution of monsters and robots across shared and privileged ground varied between conditions, such that the monsters were both shared and privileged, and thus the category does not provide a consistent cue to the ground status of the items, whereas the robots were consistently either shared or privileged (see Table 1). In the shared-category condition, all six robots were shared, and most monsters (12 of 18) were privileged. In the privileged-category condition, all robots were privileged, whereas most monsters were shared. When robots and monsters were both in privileged or shared ground, the items were interleaved within training blocks. These conditions were compared to the shared experience condition of Experiment 1, which we call the mixed condition here. In the mixed condition, monsters and robots were evenly distributed between shared and privileged ground with nine monsters and three robots in shared ground and nine monsters and three robots in privileged ground, so the category information was never a consistent cue to ground status.

Table 1.

Distribution of Monsters and Robots in Experiment 2

| Condition | Shared

|

Privileged

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1 | Block 2 | Block 3 | Block 4 | |

| Mixed | 4 monsters | 5 monsters | 5 monsters | 4 monsters |

| 2 robots | 1 robot | 1 robot | 2 robots | |

| Privileged-category | 6 monsters | 6 monsters | 3 monsters | 3 monsters |

| 3 robots | 3 robots | |||

| Shared-category | 3 monsters | 3 monsters | 6 monsters | 6 monsters |

| 3 robots | 3 robots | |||

Procedure

The training, testing, and posttest procedures were identical to the shared experience condition of Experiment 1. During the referential communication task, all participants were presented with six trials of the following types of items: shared monsters, privileged monsters, robots (who may be in shared or privileged ground depending on the training condition), and new. The same test items were presented for all training conditions.

Results

Task performance

Matchers clicked on the correct item on 99% of the trials. Directors’ accuracy on the first posttest, which tested their ability to explicitly distinguish between items they and their partners both learned and those they learned alone, was 97% with no significant differences between the training conditions. Director’s accuracy on the second posttest, which tested their knowledge for the names of the items, was 76% (70% for privileged-category, 75% for shared-category, 84% for mixed) with no significant differences between the training conditions.

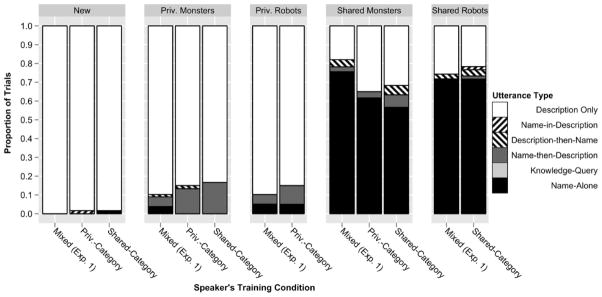

Directors’ utterances

As in Experiment 1, we assigned the directors’ first turn of each trial to one of six categories: description-only, name-in-description, description-then-name, name-then-description, knowledge-query, and name-alone.

For statistical analyses, we collapsed the shared-category and privileged-category conditions and used multilevel logistic regression models to predict whether directors used a particular utterance form with the presence of category cues (category; mixed), the ground status of the test item (shared; privileged), the category type of the test item (robot; monster), and their two-way interactions as fixed effects and subjects and items as random slopes2 and intercepts. The three-way interaction could not be included in the models because the data for each utterance type were too sparse in certain conditions.

Each panel of Figure 3 shows the distribution of the speakers’ utterance types for a particular type of trial in each training condition. For new items (far left panel), directors almost exclusively used the description-only form, as expected. Overall, directors distinguished between shared items (far right panels) and privileged items (the second and third panels) in the form of their referring expressions, regardless of the category structure: Directors rarely used names for privileged items but mainly used the name-then-description form when they did (as in Heller et al. (2012) and the shared experience condition of Experiment 1), and used the name-alone form frequently for shared items regardless of whether the items were monsters or robots. In the model predicting directors’ use of the name-alone form, this was reflected by a significant main effect of ground status (β = 3.30, SE = 0.42, p < .001) such that name-alone was used more for shared items. In the model predicting directors’ use of the name-then-description form, there was a significant main effect of ground status (β = 0.92, SE = 0.42, p < .03) such that name-then-description was used more for privileged items.

Figure 3.

Experiment 2: Each panel shows the distribution of directors’ utterances for different types of items (new, privileged monster/robots, shared monsters/robots). The distribution of the categories (monsters, robots) varied on the basis of the training conditions (mixed, privileged-category, shared-category). Priv. = privileged; Exp. = experiment.

The category manipulation had only weak effects on how the directors used the name-alone form. If category information was a strong cue, we would have expected name-alone use to increase for privileged monsters (an error) since members of this category are both shared and privileged and using the category would lead to errors. However, speakers’ use of name-alone for privileged items did not increase in the category conditions. There were small changes in the predicted direction for speakers’ use of name-alone for shared items. For shared monsters (the 4th panel), speakers used the name-alone form slightly less in the two category conditions (62% for shared-category; 57% for privileged-category) than in the mixed condition (76%), as would be predicted if the category information led to reduced use of shared experience. For shared robots (the right panel), speakers used name-alone the same amount in the shared-category condition (72%) as in the mixed condition (72%). Thus, the presence of category cues does not make directors more likely to use the name-alone form for items when all of the items in that category are shared, but does make them slightly less likely to use the name-alone form when there is a category cue and only some of items in that category are shared. In the model predicting directors’ use of the name-alone form, this was reflected by a marginal interaction of category cues and an item’s category type (β = −1.22, SE = 0.63, p < .06) such that name-alone is used more for monsters when there are no category cues, but this pattern is absent for robots.

Finally, we asked whether there was a relationship between directors’ explicit judgments about whether a particular item was shared or privileged (as measured by the posttest) and their behavior during the referential communication task. We added the explicit posttest response (whether the director believed an item was shared or privileged) and an interaction between the posttest response and the actual ground status of the item as fixed effects in the logistic regression model for name-alone described above. If directors’ utterance type is determined in the same way as their explicit judgments, then we would expect the interaction to be a significant predictor in the model. However, including the interaction resulted in no improvement in the model (χ2 = 1.99), and the interaction is not a significant predictor. We note, however, that these results are only suggestive because accuracy was so high in the posttest.

Discussion

Overall, speakers are adept at distinguishing between shared and privileged names in this task where shared knowledge is established via shared experience. The category manipulation produced only marginal changes in their behavior. These results further confirm that partner-specific memory traces are a powerful determinant of whether a speaker will assume that a name is shared or privileged. The dissociation between the results of the explicit test and the speaker’s use of a name is also consistent with the hypothesis that partner-specific episodic traces arise as an automatic consequence of name retrieval, although more research aimed at testing this will be needed given that speakers in this task performed so close to ceiling in both the posttest and referential communication task.

General Discussion

These experiments demonstrate that speakers are adept at tracking the common ground status of a particular name with respect to a particular addressee, and shed some light on the nature of the memory representations that support that ability. When shared knowledge is established through shared experience, speakers accurately track the status of names and use them appropriately in a referential communication task. This lends support to Horton and Gerrig’s (2005a, 2005b) memory-based hypothesis. Shared learning experience should create a strong episodic memory cue linking the partners to names, thus encoding ground status.

When the learning experience is instead shared with a third party whose knowledge perfectly corresponds with the addressee’s, speakers are generally quite good at distinguishing shared from privileged items, as indicated by their appropriate use of names without any descriptive content; however, they also seem to be somewhat less certain about ground status, as demonstrated by their increased use of names followed by descriptions for privileged items and explicit knowledge queries. This suggests that although this type of indirect cue helps speakers to distinguish between shared and privileged knowledge, the lack of direct evidence from having a shared learning experience with a conversational partner is still evident in their productions. Thus, speakers’ productions vary based on the type of the evidence linking the addressee to the name of an item. This in turn suggests that speakers are relying on representations that are more graded than a “one-bit” model of their partner would allow. Given the inherently probabilistic nature of many of the cues to common ground status, this is not surprising; no cue can tell an interlocutor with certainty whether his or her partner shares knowledge about a particular item (after all, even for information learned together, the partner may not have paid as much attention or may not have as good a memory for the information), and thus a representation of common ground should allow for the representation of graded information about the quality of the evidence linking the addressee to a particular piece of information.

The current experiments also provide insight into why directors use the name-then-description form when they use a name for a privileged item. Heller et al. (2012) speculated that directors might be teaching the names to matchers because they assume that the shapes would be used more than once as targets in the referential task. However, in a pilot study in which participants were explicitly told that no items would be repeated, we found the same proportion of name-then-description utterances as in Heller et al. and in the current experiments. A second possibility is that directors initially uttered the name and then became aware that it was privileged in a subsequent monitoring stage. We cannot definitively rule out that possibility, but we think it is unlikely for three reasons discussed in Heller et al. (2012). First, the form of the utterances is generally different from explicit repairs, which typically include disfluencies and editing expressions. Second, Heller et al. showed that the name itself is produced differently in name-alone and name-then-description utterances. Moreover, upon hearing just the name, naïve listeners can reliably judge whether the name will be followed by additional information.3 Third, the time to initiate utterances did not differ in the name-then-description conditions compared to the description-alone conditions, as one might expect if there was some kind of revision of the message prior to speaking.

Our results suggest that the name-then-description form is used when the speaker has some degree of uncertainty and thus plans both the name and a description. Alternatively, if information about ground becomes available as the name is retrieved, then the name will still be highly available after the ground status is determined, leading speakers to begin the utterance with the name as they are planning the description. These two possibilities are not mutually exclusive. Resolving this question is beyond the scope of the current experiments, so we leave it for future research.

Further study will also be needed to more thoroughly address the question of how these memory processes scale up to more realistic kinds of world knowledge in more realistic conversational settings and how speakers use cues like shared experience and categorical structure under these conditions. Experiment 1 provides evidence that shared experience with different people can generalize to a new conversational partner, but it is unclear how this occurs when the speaker has more uncertainty about exactly what information is shared and what is privileged. In other research, we are currently exploring how categorical knowledge is used to establish common ground in a less controlled setting. In particular, we are investigating the hypothesis that once conversational partners establish shared experience for one or more referring expressions within a domain, then that knowledge will generalize to other names that are linked to those names within knowledge domains. This could help interlocutors make inferences about shared and privileged information in the context of normal conversations, where the number of individual items whose status would need to be tracked can be quite large.

Clearly there are important unanswered questions about the full range of representations that speakers can use when evaluating the knowledge of their interlocutor and how speakers update this information in response to feedback. The current experiments provide evidence that (a) speakers have access to partner-specific information about which names are shared and which are privileged; and (b) speakers can generalize that information to a third party, though there are traces of uncertainty. Finally, speakers’ assumptions about shared knowledge, including their confidence in these assumptions, are reflected in the form of their referential descriptions. Therefore the form of a speaker’s utterance is likely to provide probabilistic cues about the speaker’s knowledge to his or her addressee during conversation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HD-27206 to Michael K. Tanenhaus and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to Kristen S. Gorman. We are grateful to Dana Subik for recruiting participants and providing technical support, to Alex Fine and Harry Reis for helpful discussions about statistics, and to Judith Degen for inspiring Experiment 1b. We are especially grateful to Jennifer Arnold for numerous helpful suggestions that drew our attention to some of the subtler patterns in the data. This resulted in a more nuanced but ultimately more interesting study.

Footnotes

To test for significance on posttest performance, we conducted a multilevel regression analysis that predicted whether the director would respond correctly or incorrectly with a fixed effect of training condition and random intercepts for participants and items.

Only random slopes for the main effects were included in this model because it could not converge with a full random effects structure.

The speakers in the current experiments produced name-then-description utterances in a similar way to Heller et al. (2012), so we would expect naïve listeners to have the same success at categorization.

References

- Barr DJ. Pragmatic expectations and linguistic evidence: Listeners anticipate but do not integrate common ground. Cognition. 2008;109:18– 40. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan SE, Hanna JE. Partner-specific adaptation in dialog. Topics in Cognitive Science. 2009;1(2):274–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-8765.2009.01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Schmidt S. Partner-specific interpretation of maintained referential precedents during interactive dialog. Journal of Memory and Language. 2009a;61(2):171–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Schmidt S. The role of executive function in perspective-taking during on-line language comprehension. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2009b;16:893–900. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.5.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Schmidt S. Beyond common and privileged: Gradient representations of common ground in real-time language use. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2011;27:62–89. doi: 10.1080/01690965.2010.543363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Schmidt S, Gunlogson C, Tanenhaus MK. Addressees distinguish shared from private information when interpreting questions during interactive conversation. Cognition. 2008;107:1122–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Schmidt S, Tanenhaus MK. Watching the eyes when talking about size: An investigation of message formulation and utterance planning. Journal of Memory and Language. 2006;54:592– 609. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2005.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Schmidt S, Tanenhaus MK. Real-time investigation of referential domains in unscripted conversation: A targeted language game approach. Cognitive Science. 2008;32(4):643– 684. doi: 10.1080/03640210802066816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbary K, Frohning E, Tanenhaus M. Context, syntactic priming, and referential form in an interactive dialogue task: Implications for models of alignment. In: Ohlsson S, Catrambone R, editors. Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Austin, TX: Cognitive Science Society; 2010. pp. 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Clark HH, Marshall C. Reference diaries. In: Waltz DL, editor. Theoretical issues in natural language processing, TINLAP-2. New York, NY: ACM; 1978. pp. 57–63. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark HH, Marshall CM. Definite reference and mutual knowledge. In: Joshi AK, Webber BL, Sag IA, editors. Elements of discourse understanding. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1981. pp. 10–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper RM. The control of eye fixation by the meaning of spoken language: A new methodology for the real-time investigation of speech perception, memory, and language processing. Cognitive Psychology. 1974;6:84–107. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(74)90005-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creel SC, Aslin RN, Tanenhaus MK. Heeding the voice of experience: The role of talker variation in lexical access. Cognition. 2008;106:633– 664. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creel SC, Tumlin MA. On-line acoustic and semantic interpretation of talker information. Journal of Memory and Language. 2011;65:264–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2011.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galati A, Brennan SE. Attenuating repeated information: For the speaker, or for the addressee? Journal of Memory and Language. 2010;62:35–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2009.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldinger SD. Echoes of echoes? An episodic theory of lexical access. Psychological Review. 1998;105:251–279. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.105.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna JE, Tanenhaus MK. Pragmatic effects on reference resolution in a collaborative task: Evidence from eye movements. Cognitive Science. 2004;28:105–115. doi: 10.1207/s15516709cog2801_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna JE, Tanenhaus MK, Trueswell JC. The effects of common ground and perspective on domains of referential interpretation. Journal of Memory and Language. 2003;49:43– 61. doi: 10.1016/S0749-596X(03)00022-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heller D, Gorman KS, Tanenhaus MK. To name or to describe: Shared knowledge affects referential form. Topics in Cognitive Science. 2012;4:290–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-8765.2012.01182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller D, Grodner D, Tanenhaus MK. The role of perspective in identifying domains of reference. Cognition. 2008;108(3):831– 836. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton WS. The influence of partner-specific memory associations on language production: Evidence from picture naming. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2007;22:1114–1139. doi: 10.1080/01690960701402933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton WS, Gerrig R. Conversational common ground and memory processes in language production. Discourse Processes. 2005a;40(1):1–35. doi: 10.1207/s15326950dp4001_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horton WS, Gerrig R. The impact of memory demands on audience design during language production. Cognition. 2005b;96:127–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton WS, Keysar B. When do speakers take into account common ground? Cognition. 1996;59:91–117. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(96)81418-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keysar B, Barr DJ, Balin JA, Brauner JS. Taking perspective in conversation: The role of mutual knowledge in comprehension. Psychological Science. 2000;11:32–38. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keysar B, Lin S, Barr DJ. Limits on theory of mind use in adults. Cognition. 2003;89(1):25– 41. doi: 10.1016/S0010-0277(03)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss RM, Weinheimer S. Concurrent feedback, confirmation, and the encoding of referents in verbal communication. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1966;4:343–346. doi: 10.1037/h0023705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronmüller E, Barr DJ. Perspective-free pragmatics: Broken precedents and the recovery-from-preemption hypothesis. Journal of Memory and Language. 2007;56:436– 455. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2006.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLennan CT, Luce PA. Examining the time course of indexical specificity effects in spoken word recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2005;31:306–321. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.31.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzing C, Brennan S. When conceptual pacts are broken: Partner-specific effects on the comprehension of referring expressions. Journal of Memory and Language. 2003;49(2):201–213. doi: 10.1016/S0749-596X(03)00028-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadig AS, Sedivy JC. Evidence for perspective-taking constraints in children’s on-line reference resolution. Psychological Science. 2002;13:329–336. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2002.00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson DC, Dale R, Kirkham NZ. The art of conversation is coordination: Common ground and the coupling of eye movements during dialogue. Psychological Science. 2007;18:407– 413. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson DC, Dale R, Tomlinson JM. Conversation, gaze coordination, and beliefs about visual context. Cognitive Science. 2009;33(8):1468–1482. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-6709.2009.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedivy JC. Pragmatic versus form-based accounts of referential contrast: Evidence for effects of informativity expectations. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 2003;32:3–23. doi: 10.1023/A:1021928914454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanenhaus MK, Spivey-Knowlton MJ, Eberhard KM, Sedivy JC. Integration of visual and linguistic information in spoken language comprehension. Science. 1995 Jun 16;268(5217):1632–1634. doi: 10.1126/science.7777863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardlow Lane L, Groisman M, Ferreira VS. Don’t talk about pink elephants! Speakers’ control over leaking private information during language production. Psychological Science. 2006;17:273–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01697.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Keysar B. The effect of information overlap on communication effectiveness. Cognitive Science. 2007;31:169–181. doi: 10.1080/03640210709336989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]