SUMMARY

How innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) in the thymus and gut become specialized effectors is unclear. The prototypic innate-like γδ T cells (Tγδ17) are a major source of interleukin-17 (IL-17). We demonstrate that Tγδ17 cells are programmed by a gene regulatory network consisting of a quartet of High Mobility Group box (HMG) transcription factors, SOX4, SOX13, TCF1 and LEF1, and not by conventional TCR signaling. SOX4 and SOX13 directly regulated the two requisite Tγδ17 cell-specific genes, Rorc and Blk, whereas TCF1 and LEF1 countered the SOX proteins and induced genes of alternate effector subsets. The T cell lineage specification factor TCF1 was also indispensable for the generation of IL-22 producing gut NKp46+ ILCs and restrained cytokine production by Lymphoid Tissue inducer-like effectors. These results indicate that similar gene network architecture programs innate sources of IL-17, independent of anatomical origins.

INTRODUCTION

ILCs and innate-like T cells (ILTC) producing IL-17 and IL-22 have emerged as the central players in mucosal immunity (Spits and Di Santo, 2011). Upon infection or alterations in cellular environments, ILCs lacking clonal antigen receptors and T cells expressing γδ TCR rapidly produce effector cytokines and growth factors to promote pathogen clearance and tissue repair (O’Brien et al., 2009; Sonnenberg et al., 2011). γδTCR+ ILTCs, similar to adaptive αβ CD4+ T cells, are segregated into effector subsets. However, unlike αβ T effectors, γδTCR+ effector subsets can be classified by the germline-encoded TCR chains and they are generated in the thymus (Jensen et al., 2008; Narayan et al., 2012; Ribot et al., 2009). More than half of Vγ2 TCR+ (designated as V2) cells are intrathymically programmed to produce IL-17 (Tγδ17) and express RORγt (Rorc), the primary transcription factor (TF) controlling IL-17 and IL-22 expression in all lymphocytes (Ivanov et al., 2006). The emergent immature (CD24hi) γδ thymocyte subsets are further distinguished by TF networks that may specify effector fates. Most of these, including the HMG TFs SOX4 and SOX13, are expressed highly only at the early effector programming phase, their expression subsiding once effector capacity has been established at the mature (CD24lo) stage. Whether this “early” wave of TFs dominantly programs ILTC subset function was unknown.

In addition to Tγδ17 ILTCs, there are at least four other RORγt+ ILTC and ILC subsets producing IL-17 and/or IL-22: αβTCR+ invariant NKT (Rachitskaya et al., 2008), Lymphoid Tissue inducer (LTi)-like (Sawa et al., 2010; Takatori et al., 2009), NK cell receptor expressing IL-22 producer (NKp46+ NCR22 (Luci et al., 2009; Sanos et al., 2009; Satoh-Takayama et al., 2008; Vonarbourg et al., 2010)), and ILC17 cells (Buonocore et al., 2010), with the latter three subsets primarily localized in the gut associated lymphoid tissues (GALTs). How ILTCs and ILCs are programmed towards distinct effectors is not well understood. In particular, whether they share a unifying genetic blueprint for differentiation distinct from that specifying adaptive helper IL-17+ T cells (Th17) is unknown. To answer these questions we determined the mechanism of innate effector programming of Tγδ17 cells and its possible involvement in GALT ILC differentiation. We showed that the HMG TF TCF1 and LEF1, and their interacting partners SOX4 and SOX13, are expressed at particularly high amounts in the precursors of Tγδ17 cells (Narayan et al., 2012). HMG TFs are transcription complex architectural proteins that bind to related sequences in the minor groove of DNA, and their cell type-specific combinatorial clustering at target genes cooperatively control transcription (Badis et al., 2009). TCF1, the nuclear effector of WNT signaling, is the best characterized HMG TF and is critical for T cell lineage specification downstream of Notch (Germar et al., 2011; Weber et al., 2011). We show here that the HMG TFs, not conventional TCR signaling, programmed IL-17 production in γδ ILTCs. Moreover, TCF1 controlled cytokine production in postnatal GALT ILCs and was absolutely required for NCR22 ILC generation. These results identify shared gene network architecture centered on TCF1 underpinning IL-17 and IL-22 production by ILTCs and GALT ILCs.

RESULTS

To determine if a common gene network controls innate lymphoid effector differentiation, we first identified genes selectively required to generate V2 Tγδ17 cells. Emergent γδ ILTC subsets are marked with gene expression profiles predictive of their eventual effector functions upon thymic egress (Narayan et al., 2012). Hence, the γδ T effector subtype-specific core TF networks were candidates for specifying innate effector lineage fate. Tγδ17 precursors, immature V2 (immV2, CD24hi) thymocytes, express genes encoding three HMG TFs, Sox4, Sox13 and Tcf7 (encoding TCF1), at the highest amounts, whereas the HMG TF Lef1 is expressed at similar amounts relative to other γδ cell subsets (Narayan et al., 2012). Aside from Lef1, the HMG TF expression precedes that of TCR ((Melichar et al., 2007; Schilham et al., 1997; Verbeek et al., 1995; Weber et al., 2011), Immgen.org). To determine whether this expression pattern programs Tγδ17 cell differentiation and function we examined γδ T cell subsets in Sox13−/− (Melichar et al., 2007), Sox4-deficient and Tcf7−/− (Verbeek et al., 1995) mice and determined HMG TF chromatin occupancies in ex vivo Tγδ17 precursors

Sox13 programs V2 cell Tγδ17 differentiation

We found that Sox13-deficiency eliminated all V2 Tγδ17 cells, whereas other γδ effector subsets were largely intact (Figure 1). Sox13 was identified as a γδ T cell-specific TF that interacts with TCF1 and LEF1 (Melichar et al., 2007), potentially modulating their function. Whereas all immature γδTCR+ thymocytes express Sox13, Tγδ17 precursors express the protein at the highest level (Figure S1A), with its expression rapidly extinguished upon thymic maturation (Narayan et al., 2012). Thus, all alterations in ILTCs associated with the absence of SOX13 must originate in the precursors or at the CD24hi stage. In Sox13−/− mice, the frequencies of CD44hi V2 cells were severely reduced in peripheral tissues, and CD24lo mature (mat) V2 thymocytes were diminished to ~50% of the WT (Figures 1A, S1B and S1C). The numbers of other γδ effectors were only marginally lower (Figure S1C and data not shown). Critically, the V2 cells that were specifically absent in Sox13−/− mice were RORγt+CCR6+CD27−CD44hiCD62L− Tγδ17 cells (Narayan et al., 2012). Fetal and adult RORγt+ matV2 thymocytes, the immediate precursors of peripheral Tγδ17 cells, were missing (Figures 1B and S1D), while the number of immV2 cells was not significantly altered. The remaining V2 cells in Sox13−/− mice did not synthesize IL-17 (or IL-17F, data not shown) ex vivo (Figure 1B), even after stimulation with the TLR2 ligand, Zymosan (Figure 1C). These results demonstrate that the high SOX13 expression in developing immV2 thymocytes is a critical factor in Tγδ17 cell differentiation.

Figure 1. SOX13 is essential for Tγδ17generation.

(A) Frequencies of activated and mature Vγ2+ T cells in γδTCR+ cells in the spleen and thymus, respectively, of WT and Sox13−/− mice. Representative data (numbers within the gates represent percents of total) from one experiment of at least four are shown. Similar results were obtained with T-Sox13−/−mice (B6). (B) The defects in Tγδ17 generation originate in the thymus. LN and thymic mature (CD24lo) Vγ2+ cells from WT and Sox13−/− mice were analyzed for the expression of RORγt and EOMES (an activator of Ifng transcription), cell surface CCR6 and CD27 and intracellular IL-17A and IFNγ in matV2 cells. Frequencies less than 0.5% are left as blanks. (C) Intracellular staining for IL-17 in splenic V2 cells isolated from mice 4 hr post Zymosan administration. (D) Left, Intracellular and nuclear staining for the two markers of Tγδ17 cells, BLK and RORγt, in V2 thymocytes from neonatal mice at different maturational stages. Right, Staining of Abs to BLK and RORγt in CD4+ αβ thymocytes was used as negative controls. (E) SOX13 partly regulates RORγt expression in CD24hi immV2 thymocytes. A decrease in Rorc transcription (Top) as indicated by GFP expression from Rorc-Gfp substrate introduced to Sox13−/− mice, and intranuclear RORγt protein expression (Bottom). Representative data from one of two experiments is shown. (F) Intracellular staining for BLK in two maturation stages of Vγ2+ and Vγ2− γδ thymocytes from LCKp-Sox13 Tg mice. (G) Intracellular staining for IL-17A in Sox13 Tg+ LN γδ T cells. See also Fig. S1.

The loss of V2 Tγδ17 cells occurred in both fetal and adult Sox13−/− thymus. Fetal-derived Vγ4+ (V4) γδ T cells are the alternate IL-17 producers (Shibata et al., 2008). Vγ4 gene rearrangements, which predominate in early fetal stages, precede that of Vγ2 and the fetal Vγ4 chain is paired with the germline encoded Vδ1TCR. While V4 Tγδ17 cells were negatively impacted in the fetal thymus by the absence of SOX13, these effectors were present in neonatal and adult Sox13−/− mice (Figures S1E, S1F and S1G). This result suggests that despite the lineage and functional relatedness (Narayan et al., 2012), developmental requirements for V2 and V4 Tγδ17 cells are distinct.

B lymphocyte kinase (BLK) is essential for Tγδ17 development (Laird et al., 2010). Ectopic Sox13 expression induces Blk expression in αβ thymocytes (Melichar et al., 2007) and among γδ T cells, BLK+ cells are the sole source of IL-17 during pathogen challenge (Laird et al., 2010; Narayan et al., 2012). In Sox13−/− mice, V2 Tγδ17 precursors (immV2 cells) expressing normal amounts of BLK were depleted and the BLK and RORγt co-expressors were specifically absent (Figure 1D). Analysis of RorcGfp/+:Sox13−/− mice showed decreased, but still significant, transcription of Rorc in the mutant immV2 cells (Figure 1E). These results suggested that SOX13-regulated BLK expression at the immature stage is critical for Tγδ17 cell differentiation. In support of this interpretation, transgenic (Tg) expression of Sox13 in all developing γδ cells (Melichar et al., 2007) increased the proportions of BLK+ γδTCR+ cells, as well as the amount of BLK expression per cell, independent of TCR repertoire (Figure 1F). Correspondingly, more γδ T cells in peripheral tissues produced IL-17 (Figure 1G). This enhancement was pronounced for V4 γδ T cells (Vγ2−), while high ectopic Sox13 expression was particularly detrimental for the survival of V2 cells that express the highest endogenous amount of Sox13 (Melichar et al., 2007), confounding their analysis in the gain-of-function model system. The absence of V2 Tγδ17 cells in Sox13−/− mice, and the increased IL-17 production from γδ T cells by the ectopic expression of SOX13 indicate that SOX13 is necessary for programming IL-17 production in ILTCs.

Sox4 regulates RORγt expression and is necessary for IL-17-mediated skin inflammation

Thymic precursors lacking SOX4 also did not generate V2 Tγδ17 ILTCs in vivo (Figure 2). SOX4 is expressed highly in T and B cell precursors as well as in immature αβ CD4+CD8+ double positive (DP) and γδ thymocyte subsets (Immgen.org). SOX4 is a transcriptional activator and was shown to also physically interact with TCF1 and LEF1 ((Sinner et al., 2007) and data not shown). We generated T cell specific Sox4-deficient (T-Sox4−/−) mice to evaluate SOX4’s function in ILTCs by breeding CD2 promoter driven Cre (CD2p-Cre) transgenic (Tg) mice to Sox4fl/fl mice (Penzo-Mendez et al., 2007). Mature adaptive αβ thymocytes were generated in T-Sox4−/− mice. Strikingly, V2 Tγδ17 ILTCs were not observed in T-Sox4−/− mice, while other γδ effector subsets were present (Figure 2A and data not shown). As in Sox13−/− mice the V2 cells that were completely lost in peripheral lymphoid tissues were RORγt+CCR6+CD27−CD44hiCD62L− Tγδ17 cells (Figure 2A and 2B). RORγt+CCR6+CD27lo matV2 thymocytes were virtually undetectable in fetal and adult T-Sox4−/− mice (Figure 2A and data not shown), while immV2 cells were present in normal proportions (Figure S2A) and did not exhibit decreased rates of survival or proliferation (Figure S2B). Accordingly, the remaining differentiated V2 cells in T-Sox4−/− mice did not produce IL-17 ex vivo (Figure 2A). The block in Tγδ17 cells correlated with a loss of Rorc transcription (based on RorcGfp/+:T-Sox4−/− mice) and RORγt protein expression beginning in immV2 thymocytes (Figures 2B and S2C). This loss was nearly absolute, more severe than the decrease observed in Sox13−/− mice (Figure 1E). In contrast, RORγt expression in αβ DP thymocytes was unaffected by the loss of SOX4 (Figure 2C), indicating that SOX4 is a γδ ILTC-specific modulator of RORγt expression.

Figure 2. SOX4 regulates RORγt expression during Tγδ17 generation.

(A) LN and mature thymic Vγ2+ cells from WT (CD2p-Cre:Sox4+/+) and T-Sox4−/− mice were analyzed for the expression of RORγt, CCR6 and CD27 and intracellular IL-17 and IFNγ. Representative data from one of four experiments is shown. (B) SOX4 regulates RORγt expression in immV2 thymocytes. The loss of Rorc transcription (Top) as indicated by the loss of GFP expression from Rorc-Gfp substrate introduced to T-Sox4−/− mice, and intranuclear RORγt protein expression (Bottom). Representative data from one of three experiments is shown. (C) Overlayed histograms of RORγt staining in αβ DP thymocytes in WT and T-Sox4−/− mice. The shaded histogram is the internal negative control for RORγt staining, gated on αβ CD4+ thymocytes that do not express Rorc. (D) PASI scoring was used to quantify the severity of psoriatic inflammation in IMQ treated mice. See also Fig. S2. Data is represented as mean+/− SEM.

Tγδ17 cells have been implicated in the dermal inflammation-driven psoriasis-like disease in mice (Cai et al., 2011; Pantelyushin et al. 2012). The disease can be induced by the application of the TLR7 ligand Imiquimod (IMQ) to skin. Tγδ17 cells residing in the dermis have been shown to be the primary lymphoid responders responsible for the disease. To determine whether SOX4 is necessary to generate pathogenic dermal Tγδ17 cells, we first assessed the distribution of γδ T cell subsets in the dermis of T-Sox4−/− mice. V2, but not V4, Tγδ17 cells were greatly reduced in T-Sox4−/− dermal tissues before treatment (Figures S2D and S2E). After topical application of IMQ for five days we observed significant thickening, scaling and erythema in WT mice. However, T-Sox4−/−mice did not show overt inflammation (Figures S2F and S2G), which was quantified by the adapted Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scoring system (Figure 2D). The lack of inflammation was correlated with significantly decreased proportions of V2 Tγδ17 cells (Figures S2D and S2E) and CD11b+Gr-1+ Neutrophils (Figure S2H) in the treated T-Sox4−/−dermis.

Unlike the dermis, V2 Tγδ17 cells were a minor population relative to Vδ1+IL-17+ V4 cells in skin draining LNs of resting WT mice (Figures S2I and S2J). Vδ1+IL-17+ V4 cells were decreased in number in the fetal T-Sox4−/− thymus (~30% of the WT number), and reduced but substantial numbers of these fetal-derived effectors were found in adult T-Sox4−/− thymus and lymph nodes (LNs, Figure S2I and data not shown). V4 LN T cells responded to IMQ, as indicated by an increase in the proportion of IL-17 producers (Figure S2I). However, this response, and the persistence of dermal V4 cells in T-Sox4−/− mice (Figures S2D and S2E), was insufficient to precipitate the fulminant inflammatory condition in the skin. In conjunction with previously published reports (Cai et al., 2012; Pantelyushin et al. 2012), these results indicate that SOX4-dependent V2 Tγδ17 cells are the primary ILTCs mediating IMQ-mediated skin inflammation. In addition, the results showed that fetal-derived V4 Tγδ17 cells, while acutely dependent on SOX13 during gestation, have compensatory mechanisms to bypass the SOX4 requirement and replenish their numbers in peripheral tissues in the absence of either TFs. In contrast, the “late” V2 Tγδ17 cells are not produced in the absence of Sox4 or Sox13, reinforcing the conclusion that these two ILTC subsets are generated under distinct conditions and are not functionally interchangeable.

TCF1 restrains IL-17+ cell generation

Tcf7 is turned on by Notch signaling to specify the T cell fate (Germar et al., 2011; Weber et al., 2011). Notch signaling also controls GALT ILC differentiation (Lee et al., 2012; Possot et al., 2011), raising the possibility that TCF1 is the core regulator of innate effector differentiation. In the absence of TCF1, development of thymic precursors and αβ T cells is aberrant (Verbeek et al., 1995). While the total γδ thymocyte number is not significantly decreased in young Tcf7−/− mice (Verbeek et al., 1995), we found that the effector programs of γδ ILTCs were extensively distorted (Figures S3A and S3B). In particular, thymic and peripheral V2 cells exhibited skewed ratios of CCR6+ (marking Tγδ17 cells) to CD27+ (IFNγ producers, (Ribot et al., 2009)) populations, with the latter subset being undetectable in some Tcf7−/− mice (Figure 3A). More than 80% of Tcf7−/− V2 cells produced IL-17, twice the frequency observed in WT V2 cells, and they were uniformly RORγt+ (Figure 3A). The bias towards IL-17 production was not V2 cell-specific as the number of thymic mature Vγ1.1+ (normally IFNγ+) cells expressing IL-17 was also increased by >10 fold (Figure S3C). This pattern was not observed in Tcrb−/− mice (N.M., unpublished), indicating that the deregulated effector programming is not simply a consequence of the decreased production of αβ thymocytes in Tcf7−/− mice.

Figure 3. TCF1 constrains Tγδ17generation.

(A) Deregulated IL-17 production in Tcf7−/− mice. Differentiation of Tγδ17 thymocytes was examined by analyses of RORγt and EOMES, CCR6 and CD27, and intracellular IL-17A and IFNγ expression in mature (CD24lo) Vγ1.1+ and Vγ2+ γδ T cells. Similar results were obtained when peripheral γδ T cell subsets were analyzed. Representative profiles from one of at least five independent experiments, each with minimum of three mice/genotype, are shown. (B) Expression of CD27 expression on Tcf7−/− immV2 thymocytes. A similar trend for increased ratio of CCR6/CD27 was observed with other γδ thymic subtypes. (C) Left, Intranuclear staining for RORγt and LEF1 in LN Vγ1.1+ (top) and Vγ2+ (bottom) T cells from WT and Tcf7−/− mice shows mutually exclusive expression of the TFs and the loss of LEF1+ γδ T cells when TCF1 is non-functional. TCF1 expression, while biased, is not starkly separated from RORγt expressors in any γδ T cell subsets. Staining controls are shown in Figure S3E. (D) Intranuclear staining for LEF1 in immature (CD24hi) and mature (CD24lo) Vγ2+ thymocytes from WT and Tcf7−/− mice. See also Fig. S3.

In all thymic γδ subtypes, the decreased expression of CD27 was already evident at the immature stage (Figure 3B). This pattern, along with a relatively normal cell cycle status of Tcf7−/ − γδ thymocytes (Figure S3D), suggested that the proclivity of TCF1-deficient γδ ILTCs towards the IL-17 effector fate is an early developmental event, not a consequence of altered maintenance of mature effectors. This interpretation was further supported by the LEF1 expression pattern. LEF1 was a discriminatory regulator of γδ effectors, as evidenced by its mutually exclusive expression to RORγt inγδ thymocytes (Figures 3C and S3E) and the partial and complete loss of LEF1+ subsets in Vγ1.1+ and V2 cells, respectively, when TCF1 was absent (Figures 3C and 3D), again starting at the immature stage of differentiation (Fig. 3D). Lef1 expression is primarily controlled by TCF1 (Driskell et al., 2007). Given the precedent that some TCF1 target gene expression can be inhibited by SOX13 (Marfil et al., 2010; Melichar et al., 2007), high amounts of SOX13 in immV2 thymocytes may interfere with TCF1-mediated induction of Lef1. Consistent with this, immature γδTCR+ thymocytes from Sox13Tg mice expressed significantly lower amounts of LEF1 and CD27 (Figure S3F). Taken together, TCF1 is necessary for pan-γδ T cell development (Figures S3G and S3H) and it programs γδ T effector subset differentiation, promoting and inhibiting IFNγ and IL-17 production, respectively, whereas SOX4 and SOX13 have the opposite function.

HMG TF chromatin occupancy

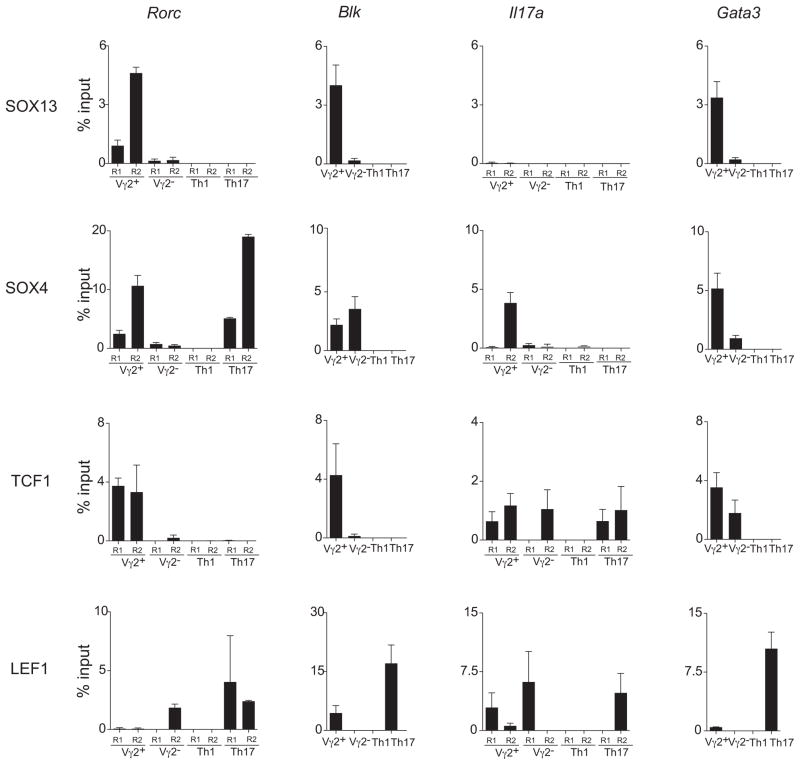

Fetal and adult immV2 thymocytes share the TF transcriptome (Figures S4A and S4B). To determine whether HMG TFs directly regulate the Tγδ17 gene network, we examined their chromatin occupancies at three gene loci (Blk, Rorc and Il17a) that are the hallmarks of Tγδ17 cells, along with the ubiquitously active Gata3 locus as a control, in ex vivo immature Vγ2+ and Vγ2− thymocytes. First, we established epigenetic chromatin modifications of the gene loci. For comparison, in vitro differentiated adaptive Th1 and Th17 αβ T cells were examined. Among γδ T cell subsets, Blk and Rorc are most abundantly expressed in V2 cells (Narayan et al., 2012). Accordingly, the Blk and Rorc loci were selectively enriched for active H3K4me3 (and acetylated H3, data not shown) modifications in immVγ2+ cells. Conversely, the Rorc locus was repressed in immVγ2− cells as indicated by H3K27me3 markings (Figure S4C). In contrast, Il17a was decorated exclusively with repressive H3K27me3 chromatin marks in the immature γδ thymocytes, consistent with its restricted expression in mature γδ thymocytes (Narayan et al., 2012). These results indicate that the distinct effector gene expression profiles of immature γδ cell subsets are foremost regulated at the chromatin level.

Next, we determined HMG TF occupancy of Blk, Rorc and Il17a loci. SOX13 was localized to the Blk and Rorc loci in immature Vγ2+, but not Vγ2−, thymocytes (Figure 4). The low signals in Vγ2− thymocytes can be accounted for by low SOX13 protein expression in the cells (Figure S1A). While SOX4 was detected at all four loci assessed in γδ thymocytes, only the docking at the Rorc loci was conserved in αβ Th17 cells. Moreover, SOX4 was particularly enriched at the Region 2 (R2) near the transcription start site dedicated for RORγt production in Vγ2+ thymocytes (Ruan et al., 2011). These results supported the above finding (Figure 2) that SOX4 is an essential regulator of Rorc expression in Tγδ17 cells.

Figure 4. ChIP assay for TF binding near the transcriptional regulatory sites of Rorc, Blk, il17a and Gata3 loci.

Immature Vγ2+ and Vγ2− thymocytes, the immediate precursors of mature thymic effectors, were compared to in vitro differentiated control Th1 and Th17 CD4 αβ T cells. Analysis of mature γδ thymocytes was not possible due to their low numbers in mice. Graphs show quantitative PCR detection for relative enrichment of target DNA sequences from ChIP using Abs to indicated TF and control IgG (Fig. S4). The regions examined are described in Fig. S4 legend. Quantitative real-time PCR data are plotted as average percentage (%) of input +/−SD from two independent experiments. Binding of the TFs to TCF consensus sequences at the control MyoG promoter was undetectable in T cells (data not shown). See also Fig. S4.

TCF1 was enriched at the Blk and Rorc loci in immature Vγ2+ cells, but not in immature Vγ2− cells. TCF1 and LEF1 occupancy at the Il17a locus exhibited distinct modality with TCF1 preferentially enriched at the intronic R2, previously shown to be a docking region in αβ T cells (Yu et al., 2011), in both thymic subsets and LEF1 at the promoter upstream R1, particularly in immature Vγ2− thymocytes. Consistent with the TCF1 chromatin occupancy in precursor cells (Weber et al., 2011), TCF1 was found docked onto the Gata3 locus in γδ thymocyte subsets, but LEF1 was not. LEF1 was associated with the Blk locus in Vγ2+ thymocytes, presumably in the RORγt− fraction, based on the mutually exclusive expression of RORγt and LEF1 in V2 thymocytes (Figure 3C). That LEF1 docking at the Blk locus is neutral to suppressive for transcription is supported by a selective enrichment at the locus in αβ Th17 cells that do not express Blk. As expected, LEF1 was excluded from the Rorc locus in Vγ2+ thymocytes. Integrated with the results from the genetic studies, these results indicate that the HMG TFs are direct transcriptional regulators of the Tγδ17 genes. SOX13 and SOX4 cooperatively orchestrate Tγδ17 differentiation by primarily controlling Blk and Rorc transcription, respectively. TCF1, implicated as a negative regulator of Tγδ17 cells, was associated with all the loci examined. Its docking at the Rorc and Blk loci was Vγ2+ cell type-specific, a pattern overlapping with SOX13 and SOX4, and raises the likelihood that a combinatorial assortment of HMG TFs at each target gene locus is directly controlling ILTC effector fate specification.

Conventional TCR signaling alone cannot specify Tγδ17 fate

A potential mechanistic explanation for the distinct global gene expression profiles of immature γδ effector subsets is that different γTCR chains (for example, Vγ1.1/Vγ5 versus Vγ2/Vγ4) convey different signals to establish diverse differentiation programs. For extrathymic adaptive Th17 cell differentiation, TCR signaling-induced IRF4 (Brustle et al., 2007) and ITK-NFAT (Gomez-Rodriguez et al., 2009) are critical regulators of Rorc and Il17a expression, respectively. IRF4 is dispensable for Tγδ17 cell differentiation (Powolny-Budnicka et al., 2011). The role of ITK in Tγδ17 differentiation was unknown. Peripheral Itk−/− γδ T cells were impaired in their Ca2+ response when they were activated via TCR stimulation in vitro (Figure S5A), establishing ITK as a key signal integrator of γδTCR signaling. In the absence of ITK, the transcriptomes of immV2 thymocytes converged with other γδ cell subsets, as indicated by principal component analysis (PCA, Figure 5A) that clusters related populations based on the major components of gene expression variability. ITK signaling was responsible for ~90% of the unique immV2 thymocyte transcriptome (Figure S5B). However, the characteristic TF profile of immV2 cells was mostly insulated from change when ITK was absent, as shown by hierarchical clustering (Figure 5B), correlating with the relatively normal generation of Tγδ17 cells in Itk−/− mice (Figure S5C). These results demonstrate that while Vγ2TCR-ITK signaling is central to the establishment of distinct transcriptomes of γδ subsets it is not responsible for the wiring of γδ effector subset-specific TF networks at the immature stage. Together, these results indicate that the conventional TCR signaling pathways so far implicated in adaptive Th17 differentiation do not dominantly specify the Tγδ17 cell fate.

Figure 5. Constrained impact of TCR signaling in effector specification.

(A) PCA of the discriminatory gene signature of Itk−/− immV2 cells. PCA of the 15% most variable genes among the populations of cells shown (colors of bars and labels indicate population; MEV > 120 in at least one population; 1,433 genes). The first three principal components (PC1–PC3) are shown, along with the proportion of the total variability represented by each component (in parentheses along axes). (B) A heat map of relative gene expression of TFs in immature γδ subsets from WT and Itk−/− mice. Data were gene row normalized and hierarchically clustered by gene and subset. Genes are color coded (see legend) to display relative gene expression. (C) LN cells from WT and Tcrgv2 transgenic mice (with and without normal Sox13) that express a functional Vγ2-Jγ1-Cγ1 (Tcr Vg2 Tg) chain in nearly all γδ T cells (top) were analyzed for the expression of intracellular IL-17A in Vγ2+ T cells. Representative profiles from one of two experiments are shown, each with a minimum of three/group. Similar results were observed with thymocytes. (D) γδ T cell progenies of c-Kithi ETPs and c-Kit− DN3 (CD25+CD44−CD3−CD4−CD8−) precursors cultured on OP9-DL1 stromal monolayers were assayed for CCR6 and CD27 expression. Representative FACS plots of V2 cells (top) and a summary of the frequencies (bottom, Student t-test P-values) of CCR6+CD27− Tγδ17 cells generated from ETPs (103 cells/well) or DN3 (5 ×103 cells/well) precursors are shown. Similar results were obtained with varying cell numbers/well. Average cell numbers obtained from DN1 or DN3 were 3.5 × 105 or 4.6 × 104/well, respectively. V1/V6 = Vγ1.1+ cells. Data are combined from 3 independent experiments, ETP n=18; DN3 n=38. See also Fig. S5.

To directly assess the role of the γδTCR in Tγδ17 cell differentiation, γδ T effector development was tracked in Vγ2 TCR Tg mice where nearly all γδ T cells express the identical Vγ2 TCR chain (Kang et al., 1998). Vγ2 TCR Tg expression on the cell surface is controlled by endogenous TCRδ chain gene rearrangement and expression. If the TCR is deterministic for effector fate, expression of a functional Vγ2+ TCR in all γδ T cells should enhance the generation of Tγδ17 cells. The Tg mice, however, did not produce a significantly enhanced number of IL-17+ γδ cells, nor could the Tcrg Tg expression in Sox13−/− mice rescue the Tγδ17 differentiation defect (Figure 5C). These results indicated that specific Vγ2 TCR signaling per se is not the dominant determinant of effector lineage specification.

If the TCR signaling alone cannot specify ILTC effector fates, an alternate possibility was that distinct effector programs are pre-set at different developmental stages. To test whether T cell developmental intermediates possess unique effector generative capacity we compared the ability of the early c-Kit (CD117)+ T progenitors (ETP) versus the late c-Kitneg DN3 precursors to generate Tγδ17 effectors. ETPs (fetal and adult) generated CCR6+CD27− Tγδ17 V2 cells in the standard OP9-DL1 culture system (Figure 5D). However, no significant generation of CCR6+CD27− V2 cells was detectable from DN3 precursors. Further, the late precursors were markedly biased to produce V1 and V2 CD27+ γδ cells (Figure S5D and data not shown). Together, these findings suggest that the maturational state of the precursors, and not TCR signaling alone, is a key determinant of Tγδ17 effector lineage specification.

TCF1 is necessary for GALT ILC differentiation

One implication of the dominance of the HMG TF network in ILTC effector differentiation was that a similar regulatory gene network may operate to generate GALT ILCs that lack clonal antigen receptors. GALT ILCs express several HMG TFs at the mRNA level. These include Tcf7, Sox4 and Tox (Aliahmad et al., 2010), though not Sox13 ((Reynders et al., 2011) and data not shown). To determine if HMG TF networks control innate effector differentiation extrathymically we first established the ILC subset-specific expression pattern of TCF1 and LEF1 proteins and Axin2, a canonical TCF1-WNT signaling target that can serve as a reporter of TCF1 as a transcriptional activator (Lustig et al., 2002). In mLN and splenic CD3−CD19− cells, TCF1 was expressed highly in IL-7R+ subsets, with all IL-7RhiRORγt+ LTi-like ILCs uniformly positive. The majority of mLN IL-7R+NKp46+ NCR22 cells also expressed TCF1 (Figures 6A, 6B and S6A), whereas <10% of the RORγt−IL-7R− was TCF1+. Expression of TCF1 and CD4, a classic marker of LTi cells, was mostly concordant, with only some CD4+IL-7Rlo-neg cells lacking TCF1. LEF1, co-expressed with TCF1 in adaptive T cells, was not expressed in LTi-like or NCR22 ILCs (Figure 6A), paralleling its exclusion from γδ thymocytes fated for IL-17 production (Figure 3C). Similar results were obtained with neonatal intestinal Lamina Propria (LP) ILC subsets (data not shown). Axin2 was variably expressed in TCF1+ ILC subsets, with LTi-like ILCs (c-Kit+IL-7R+Lin−, α4β7+/−, >50% Axin2+) considerably enriched for WNT signaling activity than in NCR22 ILCs (~10% Axin2+) (Figure S6B). These results indicate that while TCF1 is expressed in most, but not all ILCs, it is likely to have broad activities beyond that of the canonical WNT signaling transcriptional activator.

Figure 6. TCF1 regulates the differentiation and function of GALT ILCs.

(A) TCF1/LEF1 expression in CD3−CD19− mLN ILCs of adult mice. ILCs were segregated based on RORγt and IL-7R expression. CD4, NKp46, intranuclear TCF1 and LEF1 expression was assessed on the three indicated subsets. Data shown are representative profiles from one of three independent studies. (B) TCF1 expression in CD3−CD19−CD11b− mLN ILCs segregated based on NKp46 and IL-7R was analyzed. (C) TCF1 is required for the development of NCR22 cells. Intestinal LP and splenic ILCs (CD3−CD19−IL-7R+) from Tcf7−/− neonates were stained with CD4 and NKp46 to track NCR22 cells. Data shown are representative profiles from one of four studies. (D) Frequencies of CCR6+ and CD25+ in neonatal LP ILCs from Tcf7+/− heterozygotes (HET) and Tcf7−/− mice. Lines represent the mean, and Student t-test P-values are shown. Similar results in mLN. (E) Numerical reduction in the ILC subsets in the mLN of 3 wk old Tcf7−/− mice. The total cell number of IL-7R+ ILCs, RORγthi and RORγtlo ILCs, and Nkp46+ and Nkp46− RORγtlo ILCs is shown. Data are combined from two experiments, n=5/group. Data is represented as mean+− SEM. (F) Representative histograms showing the frequency of NCR22 cells in the mLNs of 3 wk old Tcf7−/− mice. (G) Increased expression of RORγt in Tcf7−/− ILCs. Averages of MFI (+/−SEM) of RORγt expression in the CD3−CD19−IL-7Rhi spleen cells is provided (n=5/group; one representative experiment of four). (H) TCF1 restrains IL-17 and IL-22 production in the ILCs. Intracellular staining for IL-17 and IL-22 in the ex vivo splenic ILCs (CD3−CD19−IL-7RhiCD4+CD25+) was perfomed post-Zymosan administration. Unlike in other tissues, the number of splenic RORγt+ ILCs were marginally increased in adult Tcf7−/− mice. Profiles shown were obtained in two additional experiments. See also Fig. S6.

To determine the range of TCF1 function, ILC subset composition and function in the small intestine, mLN and spleen of Tcf7−/− mice were examined. In Tcf7−/− neonatal intestines and spleens, NKp46+IL-7R+ NCR22 ILCs were specifically absent, whereas CD4+ LTi-like ILCs were over-represented proportionally, but only marginally increased in numbers (Figure 6C and data not shown). LTi-like ILCs are CCR6+CD25+ (Sawa et al., 2010; Vonarbourg et al., 2010) and the frequency of the CCR6+ fraction was elevated, a trend that was already evident in Tcf7+/− heterozygotes (Figure 6D). However, Tcf7−/− LTi-like ILCs lost CD25 expression, most likely indicating that as in T cell precursors (Weber et al., 2011), TCF1 may be a positive regulator of Cd25 transcription in ILCs.

In 3–4 week old Tcf7−/− mice, the number of RORγt+ ILCs was reduced to one third of normal in the mLN, while IL-7R+CD3−CD19−RORγtneg-lo fraction was decreased by 10 fold (Figure 6E). As in neonates, NKp46+ ILCs were specifically depleted (Figures 6E, 6F, and S6C). These results show that TCF1 is absolutely required for NCR22 cell generation, whereas LTi-like ILC production per se appears less dependent on TCF1. During Tγδ17 differentiation, TCF1 dampened effector capacity (Figure 3). To determine whether TCF1 functions similarly in differentiated ILCs, the effector capacity of Tcf7−/− ILCs was assessed. All RORγt+ ILCs in Tcf7−/− mice expressed higher amounts of RORγt/cell (Figure 6G) and were capable of enhanced IL-17 production (Figure 6H, top row). Upon activation with TLR2 agonist Zymosan, IL-17 and IL-22 production from Tcf7−/− LTi-like ILCs was significantly elevated (Figures 6H and S6C). Thus, as in γδ ILTC development, TCF1 has a dual function in ILC development, coordinating normal gene induction to ensure proper differentiation of ILC subsets and controlling effector function by restraining RORγt expression and IL-17/22 production.

Discussion

We showed that dermal SOX13 and SOX4-dependent V2 Tγδ17 cells are the primary innate lymphoid mediators of psoriasis-like disease in C57BL/6 mice and they develop in the thymus under the control of a HMG TF regulatory network. Adaptive Th17 cell differentiation in peripheral tissues requires TCR signaling and its downstream targets ITK (Gomez-Rodriguez et al., 2009) and IRF4 (Brustle et al., 2007), the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 and its signal mediator STAT3 (Zhou et al., 2007) as well as TGFβ activated SMAD2 (Malhotra et al., 2010). None of these factors are essential for Tγδ17 ILTC development in the thymus (Lochner et al., 2008; Malhotra et al., 2010; Powolny-Budnicka et al., 2011). Instead, a complex network of HMG TFs cooperatively controls thymic ILTC differentiation by direct regulation of key genes involved in effector function. Among them, SOX4 and SOX13 are the central positive regulators of Tγδ17 differentiation, by primarily inducing RORγt and BLK, respectively, and potentially localizing their interacting partner TCF1 to select chromatin sites. Given that HMG TFs operate in conjunction with co-factors, a detailed understanding of target gene-specific function of SOX4 and SOX13 awaits the full characterization of transcriptional complexes assembled by each factor.

During early fetal dendritic epidermal γδ T cell (Vγ3+) differentiation, cell surface SKINT signaling normally suppresses Rorc and Sox13 expression to block IL-17 production (Turchinovich and Hayday, 2011), underscoring the importance of SOX13 in positively enforcing IL-17 effector fate that must be circumvented to generate alternate innate effector cells in the fetuses. SOX13 regulates several key factors of V2 Tγδ17 cell differentiation, including Blk, Rorc and Etv5 (K.S., unpublished). The exclusion of LEF1 from developing Tγδ17 cells is also likely to be established by SOX13, as suggested by the diminished Lef1 expression in Sox13Tg mice. While published studies to date support protein-protein interactions as the main regulatory mode of SOX13-TCF1 functions, it remains possible that each can impact chromatin occupancy of the other. For instance, the loss of TCF1 may result in more precursors with SOX13 bound to the Rorc locus, thereby leading to the enhanced generation of Tγδ17 cells. However, Tcf7−/− γδ cells do not express LEF1, and the loss of LEF1-dependent effector developmental potential may also indirectly enhance Tγδ17 cell production. A systemic approach that can simultaneously track all relevant HMG TFs during Tγδ17 differentiation from thymic precursors will be necessary to define the rules governing functional connectivities of HMG TFs.

The mechanism by which the temporally disparate emergence of γδ effector subtypes is linked to specific TCRγ and δ repertoire remains to be determined. We have identified ITK as a discriminatory signal mediator of TCR that is required for the molecular divergence of V2 cells from other γδ cell subsets. Previously, it has been shown that some IL-17+ Vγ2+ T cells can be generated in the absence of ligand recognition, whereas TCR triggering led to the capacity to produce IFNγ (Jensen et al., 2008). In vitro assays, however, showed that the cell surface expression of Vγ2TCR itself is uniquely able to trigger signaling, akin to the preTCR signaling that generates αβ DP cells. Given the substantial, but constrained, alterations of V2 cells in Itk−/− mice, we propose that the Vγ2TCR-ITK signaling constitutes a developmental checkpoint related to the β-selection for αβ thymocytes, but that this tonic signaling alone does not regulate the TF transcriptome that programs the Tγδ17 effectors.

Published data (Jensen et al., 2008; Ribot et al., 2009; Turchinovich and Hayday, 2011) and our results from the in vitro cultures and TCRγ Tg mice indicate at least two other factors that can contribute to the observed correlation between TCR repertoire and effector function: developmental timing and limiting permissive niches. In the OP9 culture system DN3 cells and their progenies cannot generate Tγδ17 cells, indicating a developmental stage-specific gene program, perhaps linked to an ordered Tcrgv gene rearrangement process. However, the enforced expression of Vγ2TCR does not enhance the number of Tγδ17 cells generated in vivo, indicating that Vγ2TCR-specific signals alone cannot dictate effector fate and that there exists a limit to the number of Tγδ17 cells that can be produced regardless of the TCR repertoire.

Recently, it has been concluded that most Tγδ17 cells are generated during gestation (Haas et al., 2012). While this can account for the correlation for V4 cells, whether V2 Tγδ17 cells also originate exclusively during gestation remains to be clarified. The requirements for SOX4 and SOX13 in the generation of V2 and V4 Tγδ17 cells are distinct, with V2 Tγδ17 cells showing an absolute dependence, while V4 Tγδ17 cells are mostly dependent on SOX13, but even here only the fetal thymic cellularity was significantly impacted by the loss of Sox13. These distinct developmental requirements between V2 and V4 cells is observed despite their overall molecular similarity at the gene expression level (Narayan et al., 2012), suggesting T cell-extrinsic environmental signals differentially affecting the early (Vγ4+) versus late (Vγ2+) Tγδ17 cell development.

The high Tcf7 expression is an unifying feature of developing thymocytes and GALT ILCs. Notch signaling has been shown to directly induce Tcf7 transcription (Germar et al., 2011; Weber et al., 2011). Based on the known targets of TCF1 in T cells and their precursors, TCF1 may directly regulate the expression of several markers of GALT ILCs, including Id2 (Germar et al., 2011; Rockman et al., 2001), Il7r (Germar et al., 2011), Cd4 (Huang et al., 2006) and Cd25 (Weber et al., 2011). For ILCs, Tcf7-deficiency led to the selective loss of NCR22 cells that have been shown to be most dependent on Notch signaling for development (Lee et al., 2012). Other RORγt+ ILCs are mostly spared, although their functional profiles are altered when TCF1 is absent, as evidenced by the hyper production of cytokines, reminiscent of Tcf7−/− γδ ILTCs. Thus, TCF1 is a negative regulator of IL-17 and IL-22 production in differentiated innate lymphoid effectors. An analogous (Yu et al., 2011) or distinct (Muranski et al., 2011) function of TCF1 in adaptive T cells has been proposed, but in vivo, TCF1 may primarily impact Th17 cell survival or renewal. This difference in the repertoire of TCF1 function in innate versus adaptive lymphocytes is likely linked to the dominance of TCR and cytokine receptor signaling in specifying adaptive effector differentiation, whereas the production of fast-acting innate lymphoid effectors is acutely dependent on intrinsic gene networks programmed in the tissues of origin. TCF1 may also be required for fetal LTi development as Tcf7−/− mice do not generate Peyer’s patches (N.M. unpublished), similar to mice lacking the HMG TF Tox (Aliahmad et al., 2010). Together, these results suggest that the diversity of RORγt+ innate lymphoid subsets can be generated by unique combinatorial usage of HMG TFs in precursors arising in distinct tissues.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

Mice

Sox13−/− (129/J), Sox13 Tg (Melichar et al., 2007), TcrVg2 Tg (C57BL/6) (Kang et al., 1998), Axin2lz/+ (H. Birchmeier, MDC Berlin), Tcrb−/−, Rorc-Gfp (JAX), Itk−/− (Felices et al., 2009) and Tcf7−/− mice (Verbeek et al., 1995) were previously described. Sox4fl/fl mice were generated by V. Lefebvre (Penzo-Mendez et al., 2007) and crossed to CD2p-CreTg mice. All mice were housed in a specific pathogen free barrier facility and experiments performed were approved by the IACUC.

Flow cytometry

Antibodies (Abs) used are detailed in Supplementary Information. Data was acquired on a BD LSRII cytometer and was analyzed using FlowJo (Treestar).

Ex vivo stimulation, Zymosan activation and OP9 culture

Freshly isolated thymic and LN cells were cultured (2×106/well) with PMA (10ng/ml) and Ionomycin (1μg/ml) for 4 hrs at 37°C, with Golgi Stop and Golgi Plug (BD Biosciences) added after 1 hr. After stimulation, cells were stained for cell surface markers and intracellular cytokine production using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences). To activate innate effectors, mice were injected intra-peritoneally with Zymosan (Sigma) in PBS (6mg/mouse). Four hrs post-injection, lymphocytes were isolated from the mLN and spleens. Cells were stimulated with PMA/Iono and intracellular staining for IL-22 and IL-17 in γδ ILTCs and ILCs was performed. Intestinal LP lymphocytes from 10 day old mice was isolated as described (Qiu et al., 2012). Sorted fetal and adult ETPs (c-Kit+CD4−CD8−CD3−CD25−CD44+) or c-Kit− DN3 (CD4−CD8−CD3−CD25+CD44−) cells were plated onto OP9-DL1 monolayers (J. C. Zuniga-Pflucker) at varous concentrations in αMEM media containing 20% FBS (Gibco), 1ng/ml IL-7 (R&D Systems) and 5ng/ml Flt3L (R&D Systems). After 5–12 days of culture, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Psoriasis induction

Aldara (5% Imiquimod, 3M Pharmaceuticals) or control vehicle cream was applied daily for five days on the back and ear. The disease severity in mice was scored by a modified PASI normally used to rank human psoriasis severity (Fredriksson and Pettersson, 1978). The scale thickness and erythema were scored from 0–4 (slight, moderate, severe, very severe), and the total area of the inflammation covering the back was scored from 0–6 (0%, 10–29%, 30–49%, 50–69%, 70–89%, 90–100%). The scores for the scales and erythema were added and multiplied by the score for the body area to obtain the total score ranging from 0 (No disease) to 48. Dermal cells were obtained according to a published protocol (Suffia et al., 2005).

Microarray analysis

Samples were processed and analyzed according to the standard operating protocol of the Immunological Genome Project (Immgen.org and Supplemental Information). GEO:GSE15907.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

Sorted immature Vγ2+ and Vγ2− thymocyte subsets were used to determine HMG TF chromatin occupancy at the Blk, Rorc, Il17a and Gata3 loci using commercially available Abs, reagents and kits. In vitro differentiated Th1 and Th17 cells were used as controls. Detailed method is provided in Supplemental Information.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

SOX4, SOX13, LEF1 and TCF1 coordinately program innate IL-17 producing γδ T cells

SOX4 directly regulates RORγt induction

TCR signaling components of adaptive IL-17+ cells do not drive innate IL-17+ cells

TCF1 controls the production of innate IL-17 and IL-22 in the gut mucosa

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Bix and E. Huseby for comments on the manuscript, the ImmGen core team (M. Painter, J. Ericson, S. Davis) for help with data generation and processing, eBioscience, Affymetrix, and Expression Analysis for support of the ImmGen Project, and H. Birchmeier and H. Clevers for mice. Supported by NIH/NCI CA100382 to J.K., NIH/NIAID AI084987 to L.J.B., AI072073 to ImmGen and NIH/NIAMS AR54153 to V.L.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aliahmad P, de la Torre B, Kaye J. Shared dependence on the DNA-binding factor TOX for the development of lymphoid tissue-inducer cell and NK cell lineages. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:945–952. doi: 10.1038/ni.1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badis G, Berger MF, Philippakis AA, Talukder S, Gehrke AR, Jaeger SA, Chan ET, Metzler G, Vedenko A, Chen X, et al. Diversity and complexity in DNA recognition by transcription factors. Science. 2009;324:1720–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.1162327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brustle A, Heink S, Huber M, Rosenplanter C, Stadelmann C, Yu P, Arpaia E, Mak TW, Kamradt T, Lohoff M. The development of inflammatory Th17 cells requires interferon-regulatory factor 4. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:958–966. doi: 10.1038/ni1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonocore S, Ahern PP, Uhlig HH, Ivanov II, Littman DR, Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Innate lymphoid cells drive IL-23-dependent innate intestinal pathology. Nature. 2010;464:1371–1375. doi: 10.1038/nature08949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Shen X, Ding C, Qi C, Li K, Li X, Jala VR, Zhang HG, Wang T, Zheng J, Yan J. Pivotal role of dermal IL-17-producing γδT cells in skin inflammation. Immunity. 2011;35:596–610. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driskell RR, Goodheart M, Neff T, Liu X, Luo M, Moothart C, Sigmund CD, Hosokawa R, Chai Y, Engelhardt JF. Wnt3a regulates Lef-1 expression during airway submucosal gland morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2007;305:90–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felices M, Yin CC, Kosaka Y, Kang J, Berg LJ. Tec kinase Itk in γδT cells is pivotal for controlling IgE production in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8308–8313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808459106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis--oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica. 1978;157:238–244. doi: 10.1159/000250839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germar K, Dose M, Konstantinou T, Zhang J, Wang H, Lobry C, Arnett KL, Blacklow SC, Aifantis I, Aster JC, Gounari F. TCF-1 is a gatekeeper for T-cell specification in response to Notch signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:20060–20065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110230108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Rodriguez J, Sahu N, Handon R, Davidson TS, Anderson SM, Kirby MR, August A, Schwartzberg PL. Differential expression of IL-17A and -17F is coupled to TCR signaling via inducible T cell kinase. Immunity. 2009;31:587–597. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas JD, Ravens S, Duber S, Sandrock I, Oberdorfer L, Kashani E, Chennupati V, Fohse L, Naumann R, Weiss S, et al. Development of IL-17-Producing γδT Cells Is Restricted to a Functional Embryonic Wave. Immunity. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Xie H, Ioannidis V, Held W, Clevers H, Sadim MS, Sun Z. Transcriptional regulation of CD4 gene expression by TCF-1/β-catenin pathway. J Immunol. 2006;176:4880–4887. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, Cua DJ, Littman DR. The orphan nuclear receptor RORγt directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen KD, Su X, Shin S, Li L, Youssef S, Yamasaki S, Steinman L, Saito T, Locksley RM, Davis MM, et al. Thymic selection determines γδT cell effector fate: antigen-naive cells make IL-17 and antigen-experienced cells make IFNγ. Immunity. 2008;29:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Coles M, Cado D, Raulet DH. The developmental fate of T cells is critically influenced by TCRγδ expression. Immunity. 1998;8:427–438. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80548-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RM, Laky K, Hayes SM. Unexpected role for the B cell-specific Src family kinase BLK in the development of IL-17-producing γδT cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:6518–6527. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Cella M, McDonald KG, Garlanda C, Kennedy GD, Nukaya M, Mantovani A, Kopan R, Bradfield CA, Newberry RD, Colonna M. AHR drives the development of gut ILC22 cells and postnatal lymphoid tissues via pathways dependent on and independent of Notch. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:144–151. doi: 10.1038/ni.2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochner M, Peduto L, Cherrier M, Sawa S, Langa F, Varona R, Riethmacher D, Si-Tahar M, Di Santo JP, Eberl G. In vivo equilibrium of proinflammatory IL-17+ and regulatory IL-10+ Foxp3+ RORγt+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1381–1393. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luci C, Reynders A, Ivanov II, Cognet C, Chiche L, Chasson L, Hardwigsen J, Anguiano E, Banchereau J, Chaussabel D, et al. Influence of the transcription factor RORγt on the development of NKp46+ cell populations in gut and skin. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:75–82. doi: 10.1038/ni.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig B, Jerchow B, Sachs M, Weiler S, Pietsch T, Karsten U, van de Wetering M, Clevers H, Schlag PM, Birchmeier W, Behrens J. Negative feedback loop of Wnt signaling through upregulation of conductin/axin2 in colorectal and liver tumors. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1184–1193. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1184-1193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra N, Robertson E, Kang J. SMAD2 is essential for TGF beta-mediated Th17 cell generation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:29044–29048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.156745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marfil V, Moya M, Pierreux CE, Castell JV, Lemaigre FP, Real FX, Bort R. Interaction between Hhex and SOX13 modulates Wnt/TCF activity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5726–5737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.046649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melichar HJ, Narayan K, Der SD, Hiraoka Y, Gardiol N, Jeannet G, Held W, Chambers CA, Kang J. Regulation of γδ versus αβ T lymphocyte differentiation by the transcription factor SOX13. Science. 2007;315:230–233. doi: 10.1126/science.1135344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muranski P, Borman ZA, Kerkar SP, Klebanoff CA, Ji Y, Sanchez-Perez L, Sukumar M, Reger RN, Yu Z, Kern SJ, et al. Th17 cells are long lived and retain a stem cell-like molecular signature. Immunity. 2011;35:972–985. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan K, Sylvia KE, Malhotra N, Yin CC, Martens G, Vallerskog T, Kornfeld H, Xiong N, Cohen NR, Brenner MB, et al. Intrathymic programming of effector fates in three molecularly distinct γδT cell subtypes. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:511–518. doi: 10.1038/ni.2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien RL, Roark CL, Born WK. IL-17-producing γδT cells. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:662–666. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelyushin S, Haak S, Ingold B, Kulig P, Heppner FL, Navarini AA, Becher B. Rorγt+ innate lymphocytes and γδ T cells initiate psoriasiform plaque formation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2252–2256. doi: 10.1172/JCI61862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzo-Mendez A, Dy P, Pallavi B, Lefebvre V. Generation of mice harboring a Sox4 conditional null allele. Genesis. 2007;45:776–780. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possot C, Schmutz S, Chea S, Boucontet L, Louise A, Cumano A, Golub R. Notch signaling is necessary for adult, but not fetal, development of RORγt(+) innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:949–958. doi: 10.1038/ni.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powolny-Budnicka I, Riemann M, Tanzer S, Schmid RM, Hehlgans T, Weih F. RelA and RelB transcription factors in distinct thymocyte populations control lymphotoxin-dependent IL-17 production in γδT cells. Immunity. 2011;34:364–374. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Heller JJ, Guo X, Chen ZM, Fish K, Fu YX, Zhou L. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates gut immunity through modulation of innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2012;36:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachitskaya AV, Hansen AM, Horai R, Li Z, Villasmil R, Luger D, Nussenblatt RB, Caspi RR. Cutting edge: NKT cells constitutively express IL-23 receptor and RORγt and rapidly produce IL-17 upon receptor ligation in an IL-6-independent fashion. J Immunol. 2008;180:5167–5171. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynders A, Yessaad N, Vu Manh TP, Dalod M, Fenis A, Aubry C, Nikitas G, Escaliere B, Renauld JC, Dussurget O, et al. Identity, regulation and in vivo function of gut NKp46+RORγt+ and NKp46+RORγt- lymphoid cells. Embo J. 2011;30:2934–2947. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribot JC, deBarros A, Pang DJ, Neves JF, Peperzak V, Roberts SJ, Girardi M, Borst J, Hayday AC, Pennington DJ, Silva-Santos B. CD27 is a thymic determinant of the balance between iIFNγ- and IL-17-producing γδT cell subsets. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:427–436. doi: 10.1038/ni.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockman SP, Currie SA, Ciavarella M, Vincan E, Dow C, Thomas RJ, Phillips WA. Id2 is a target of the β-catenin/TCF pathway in colon carcinoma. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45113–45119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107742200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan Q, Kameswaran V, Zhang Y, Zheng S, Sun J, Wang J, DeVirgiliis J, Liou HC, Beg AA, Chen YH. The Th17 immune response is controlled by the Rel-RORγ-RORγt transcriptional axis. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2321–2333. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanos SL, Bui VL, Mortha A, Oberle K, Heners C, Johner C, Diefenbach A. RORgammat and commensal microflora are required for the differentiation of mucosal IL- 22-producing NKp46+ cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:83–91. doi: 10.1038/ni.1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh-Takayama N, Vosshenrich CA, Lesjean-Pottier S, Sawa S, Lochner M, Rattis F, Mention JJ, Thiam K, Cerf-Bensussan N, Mandelboim O, et al. Microbial flora drives IL-22 production in intestinal NKp46+ cells that provide innate mucosal immune defense. Immunity. 2008;29:958–970. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa S, Cherrier M, Lochner M, Satoh-Takayama N, Fehling HJ, Langa F, Di Santo JP, Eberl G. Lineage relationship analysis of RORγt+ ILCs. Science. 2010;330:665–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1194597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilham MW, Moerer P, Cumano A, Clevers HC. Sox4 facilitates thymocyte differentiation. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1292–1295. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata K, Yamada H, Nakamura R, Sun X, Itsumi M, Yoshikai Y. Identification of CD25+ gamma delta T cells as fetal thymus-derived naturally occurring IL-17 producers. J Immunol. 2008;181:5940–5947. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.5940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinner D, Kordich JJ, Spence JR, Opoka R, Rankin S, Lin SC, Jonatan D, Zorn AM, Wells JM. Sox17 and Sox4 differentially regulate β-catenin/TCF activity and proliferation of colon carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:7802–7815. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02179-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg GF, Fouser LA, Artis D. Border patrol: regulation of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis at barrier surfaces by IL-22. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:383–390. doi: 10.1038/ni.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spits H, Di Santo JP. The expanding family of innate lymphoid cells: regulators and effectors of immunity and tissue remodeling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:21–27. doi: 10.1038/ni.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suffia I, Reckling SK, Salay G, Belkaid Y. A role for CD103 in the retention of CD4+CD25+ Treg and control of Leishmania major infection. J Immunol. 2005;174:5444–5455. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takatori H, Kanno Y, Watford WT, Tato CM, Weiss G, Ivanov II, Littman DR, O’Shea JJ. Lymphoid tissue inducer-like cells are an innate source of IL-17 and IL-22. J Exp Med. 2009;206:35–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchinovich G, Hayday AC. Skint-1 identifies a common molecular mechanism for the development of IFNγ-secreting versus IL-17-secreting γδT cells. Immunity. 2011;35:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek S, Izon D, Hofhuis F, Robanus-Maandag E, te Riele H, van de Wetering M, Oosterwegel M, Wilson A, MacDonald HR, Clevers H. An HMG-box-containing T-cell factor required for thymocyte differentiation. Nature. 1995;374:70–74. doi: 10.1038/374070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Belle AB, de Heusch M, Lemaire MM, Hendrickx E, Warnier G, Dunussi-Joannopoulos K, Fouser LA, Renauld JC, Dumoutier L. IL-22 is required for IMQ-induced psoriasiform skin inflammation in mice. J Immunol. 2012;188:462–469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonarbourg C, Mortha A, Bui VL, Hernandez PP, Kiss EA, Hoyler T, Flach M, Bengsch B, Thimme R, Holscher C, et al. Regulated expression of nuclear receptor RORgammat confers distinct functional fates to NK cell receptor-expressing RORgammat(+) innate lymphocytes. Immunity. 2010;33:736–751. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber BN, Chi AW, Chavez A, Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Yang Q, Shestova O, Bhandoola A. A critical role for TCF-1 in T-lineage specification and differentiation. Nature. 2011;476:63–68. doi: 10.1038/nature10279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Sharma A, Ghosh A, Sen JM. TCF-1 negatively regulates expression of IL-17 family of cytokines and protects mice from EAE. J Immunol. 2011;186:3946–3952. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Ivanov II, Spolski R, Min R, Shenderov K, Egawa T, Levy DE, Leonard WJ, Littman DR. IL-6 programs Th17 cell differentiation by promoting sequential engagement of the IL-21 and IL-23 pathways. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:967–974. doi: 10.1038/ni1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.