Abstract

Advances in task-based functional MRI (fMRI), resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI), and arterial-spin labeled (ASL) perfusion MRI have occurred at a rapid pace in recent years. These techniques for measuring brain function have great potential to improve the accuracy of prognostication for civilian and military patients with traumatic coma. In addition, fMRI, rs-fMRI, and ASL have provided novel insights into the pathophysiology of traumatic disorders of consciousness, as well as mechanisms of recovery from coma. However, functional neuroimaging techniques have yet to achieve widespread clinical use as prognostic tests for patients with traumatic coma. Rather, a broad spectrum of methodological hurdles currently limits the feasibility of clinical implementation. In this review, we discuss the basic principles of fMRI, rs-fMRI and ASL and their potential applications as prognostic tools for patients with traumatic coma. We also discuss future strategies for overcoming the current barriers to clinical implementation.

Keywords: traumatic brain injury (TBI), traumatic axonal injury (TAI), coma, functional MRI (fMRI), resting state functional MRI (rs-fMRI), arterial-spin labeled (ASL) perfusion MRI, default mode network (DMN), traumatic coma

Introduction

Motivation for fMRI as a Prognostic Tool in Traumatic Coma

Traumatic coma affects more than 1 million civilians worldwide each year [1–3]. In addition, it is estimated that hundreds of military personnel have experienced a traumatic coma since the start of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq [4, 5]. Some civilians and veterans remain in a vegetative state (VS) [6] or a minimally conscious state (MCS) [7] for months to years after emergence from coma [8, 9]. Yet, recent evidence from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs “Emerging Consciousness” Program and the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems suggests that a majority of patients with traumatic coma ultimately recover consciousness [9–11]. In addition, recovery of functional independence is possible in both civilian [10, 12, 13] and military [4] patients after traumatic coma. Outcome data from a recent series of studies have revealed that 1) a substantial minority of patients in VS and MCS for at least one year demonstrate ongoing improvement through 5 years [8, 10, 14–16], 2) up to 20% of patients eventually achieve household independence and/or return to work or school [8, 10], and 3) patients in traumatic MCS show more prolonged recoveries and are left with significantly less functional disability than those in VS and non-traumatic MCS [14]. Therefore, it is critical to identify as early as possible those patients who are severely injured but likely to demonstrate meaningful functional improvement.

Given the profound implications of neurological recovery for the patient, family and society, significant attention has been dedicated in recent years to the development of assessment tools to predict outcomes after traumatic coma. The largest such efforts to date have been the International Mission for Prognosis and Analysis of Clinical Trials in TBI (IMPACT) [17] and the Medical Research Council (MRC) CRASH [3] models. These prognostic tools utilize neurological examination and laboratory data, as well as imaging data from head computed tomography (CT), which continues to be the preferred acute neuroimaging technique for patients with traumatic coma because of its accessibility and speed of acquisition. Over the past decade, efforts have been made to incorporate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data into prognostic models, since several studies have demonstrated that MRI provides superior prognostic value compared to CT [12, 18, 19]. Yet despite the benefit that MRI provides over CT for prognostication in traumatic coma, conventional MRI has been shown to have significant limitations as an early predictive tool of long-term outcomes [20].

Further complicating efforts at prognostication are recent data demonstrating that standard bedside neurological examinations are often inaccurate for patients with traumatic disorders of consciousness (DOC). For example, consensus-based diagnosis of post-traumatic VS is associated with a misdiagnosis rate of up to 43% [21–23] when compared to a standardized neurobehavioral evaluation with the Coma Recovery Scale-Revised (CRS-R) [24]. This alarming statistic may be attributed to fluctuations in arousal, or impairments in visual, auditory, motor, or language function that limit the patient’s ability to interact with the examiner [23]. The high misdiagnosis rate in patients with traumatic DOC has significant implications for prognosis, since patients in post-traumatic MCS have significantly greater potential for neurological recovery than those in post-traumatic VS [16, 25].

Given the limitations of CT, MRI, and clinical consensus in predicting outcomes for patients with traumatic DOC, interest has grown in recent years in the application of functional neuroimaging techniques to identify brain activity and improve prognostic accuracy in patients recovering from traumatic coma. Advanced functional imaging techniques have begun to provide extraordinary insights into residual cognitive function in patients with traumatic DOC that could not be otherwise revealed by bedside examination or conventional neuroimaging. In addition, task-based functional MRI (fMRI), resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI), and arterial-spin labeled (ASL) perfusion MRI have the potential to identify patients who may benefit from pharmacologic and electrophysiologic therapies aimed at restoring consciousness [26–28].

This review aims to provide an overview of recent advances in functional neuroimaging that are relevant to outcome prediction in patients with traumatic coma. The methodological principles and clinical applications of task-based fMRI, rs-fMRI, and ASL perfusion MRI are described, with particular attention directed toward feasibility and clinical implementation. In addition, future directions for further study and overcoming barriers to clinical implementation are discussed.

Task-based fMRI

Principles and Methods

Task-based fMRI is based on the principle that an MRI scanner can detect signal changes within the brain when a patient is exposed to a stimulus or asked to perform a cognitive task while in the scanner. The type of signal contrast that is most commonly used in fMRI studies is blood-oxygen level dependent (BOLD) MRI [29, 30]. The BOLD technique takes advantage of activation-flow coupling within the brain. Specifically, when brain metabolic activity increases in response to a stimulus or task, so does local cerebral blood flow (CBF), assuming that cerebrovascular autoregulation is intact [31]. In BOLD fMRI, the physiological aspect of the activation-flow coupling response that is measured is the decrease in regional deoxyhemoglobin caused by a CBF response that exceeds the metabolic demands of the activated neurons. This decreased concentration of paramagnetic deoxyhemoglobin causes a susceptibility distortion of the magnetic field, and hence an increase in the T2* properties of the tissue that is detected by the MRI receiver coil.

In an example task-based fMRI study, the patient is exposed to an auditory stimulus administered via headphones or a visual stimulus administered via eye goggles or a video screen that is located behind the MRI scanner and viewed from a mirror attached to the head coil. Alternatively, a patient may be provided verbal instructions via headphones to perform a cognitive task, such as imagining that one is swimming or playing tennis [32]. There are two major experimental designs for fMRI – event-related design and block-designs. Event-related designs are typically used to estimate the hemodynamic response to stimuli while block-designs are more sensitive for detecting activation. For the purposes for predicting outcome in traumatic coma, sensitivity is critically important and therefore most studies have utilized block designs. In a block design, stimuli are presented in discreet epochs (i.e., 16 sec to 1 min), and the BOLD signal during the stimulus-blocks (“on”) is compared to the BOLD signal during a control-block (“off”), such as a rest period. Brain “activation maps” are then derived from regions with statistically significant differences in the BOLD signal between “on” and “off” periods. There are many statistical approaches for detecting these differences (e.g., general linear modeling), but these methods are beyond the scope of this review and are discussed in more detail elsewhere [33].

Task-Based fMRI Correlations with Outcome in Traumatic Coma

In considering recent data from fMRI studies in traumatic coma, it is important to recognize that the majority of studies have been performed in the subacute-to-chronic stage of injury and have focused on correlations between fMRI data and neurocognitive and/or behavioral tests performed at the time of the fMRI scan. This limitation reflects the significant difficulty of acquiring fMRI early enough in the course of traumatic coma to provide an acute prognostic biomarker. Intracranial hypertension, hemodynamic instability, motor restlessness and a variety of other clinical factors often limit the feasibility of performing acute fMRI. Nevertheless, the potential clinical utility of fMRI has been demonstrated by studies showing that abnormal brain activation patterns detected by fMRI correlate with a broad range of neurocognitive and functional deficits in patients with prior traumatic coma, including memory impairment [34, 35] and motor dysfunction [36]. In a particularly noteworthy study, BOLD signal changes during an “n-back” memory paradigm correlated with working memory performance and with diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) measures of white matter connectivity in patients in the chronic stage of severe TBI [35].

Functional MRI has also been used to elucidate the mechanisms involved in neuroplasticity. In a cohort of adolescents (age 12 to 19 years) with chronic moderate-to-severe TBI, patients performing a perspective-taking task (i.e. thinking of the self from a third-person perspective) exhibited BOLD signal changes in regions such as the cuneus and parahippocampal gyrus that were not observed in controls [37]. Differential fMRI brain activation patterns were present despite the fact that patients exhibited normal performance scores on neurocognitive tests conducted outside the MRI scanner. These results suggest that recovery of neurocognitive function may be dependent upon the recruitment of additional neuroanatomic networks that were not previously associated with a particular function.

For patients with chronic traumatic DOC, fMRI has not only begun to elucidate the mechanisms involved in recovery and plasticity, it has also challenged classical concepts about the diagnosis of altered consciousness. In one of several groundbreaking studies, a 23-year-old woman in a traumatic VS was asked to perform motor and spatial imagery tasks (imagining playing tennis or walking through her house) while being imaged in the MRI scanner [38]. FMRI activation patterns in the patient were similar to those observed in healthy controls: the supplementary motor area contingently activated during the motor imagery task, while the parahippocampal gyrus, posterior parietal cortex, and lateral premotor cortex activated during the spatial imagery task. These activations were detected despite the absence of any behavioral evidence of awareness of self or environment on detailed neurological examination by a multidisciplinary team. This provocative finding of fMRI revealing active cognitive processing that is undetectable at the bedside has been reproduced in patients with MCS and VS in studies using a variety of motor imagery, spatial imagery, language, and visual paradigms [39–55] (Table 1). In the largest such study to date, Monti and colleagues found that five of 54 patients with DOC (23 in VS and 31 in MCS; 33 with severe TBI) had brain activation patterns during command-following paradigms involving motor and spatial imagery that were similar to controls (all five patients had traumatic DOC). Strikingly, one subject in traumatic MCS answered questions while in the MRI scanner by linking the two imagery tasks described above to “yes” and “no” answers [53]. Collectively, these studies suggest that task-based fMRI may provide evidence of conscious awareness that evades detection on bedside examination, thus raising the intriguing question as to whether fMRI data should be incorporated into clinical definitions of consciousness. In addition, the potential prognostic utility of these fMRI paradigms was highlighted in a recent study in which hierarchical language-related fMRI activation patterns correlated with the degree of behavioral recovery 6 months after the fMRI scan, as defined by the follow-up CRS-R score [40]. Although the fMRI data for the 41 patients (22 VS, 19 MCS; 11 TBI) were acquired in the subacute-to-chronic stages of recovery (2 to 122 months), the strong correlation between fMRI data and 6-month behavioral outcomes suggests that acute fMRI may provide similar prognostic utility.

Table 1.

Functional MRI studies using “passive” sensory stimuli or active tasks in patients recovering from traumatic coma

| Authors (year) | N | Dx | Time to fMRI |

Stimulus or task | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive Stimulus fMRI Studies | |||||

| Bekinschtein et al. (2004) [46] | 1 | MCS | 5 months | Auditory (familiar voice) | High level activation |

| Bekinschtein et al. (2005) [47] | 1 | VS | 2 months | Auditory (words) | Low level activation |

| Schiff et al. (2005) [44] | 2* | MCS | 18–24 months | Auditory (speech), tactile | High level activation |

| Di et al. (2007) [48] | 11* | 7 VS 4 MCS |

2–48 months | Auditory (familiar voice own name) | High (MCS and VS) and low (VS) level activation |

| Coleman et al. (2007) [41] | 12* | 7 VS 5 MCS |

9–108 months | Auditory (forward/backward speech, ambiguity) | High (VS and MCS) and low (VS and MCS) level activation |

| Fernandez-Espejo et al. (2008) [45] | 7 | 3 VS 4 MCS |

1–11 months | Auditory (forward/backward speech) | High (VS and MCS) and low (VS and MCS) level activation |

| Coleman et al. (2009) [40] | 41* | 22 VS 19 MCS |

2–120 months | Auditory (forward/backward speech, ambiguity) | High (VS and MCS) and low (VS and MCS) level activation |

| Zhu et al. (2009) [49] | 9* | MCS | 1–2 months | Visual (emotional picture) | High level activation |

| Newcombe et al. (2010) [39] | 12* | VS* | 3 months – 4 years | Auditory (forward/backward speech, ambiguity) | Level of activation correlated with DTI measures of white matter integrity |

| Qin et al. (2010) [50] | 11* | 7 VS 4 MCS |

2–48 months | Auditory (familiar voice own name) | High (MCS) and low (VS) level activation |

| Fernandez-Espejo et al. (2010) [51] | 1 | VS | 1 month, 12 months | Auditory (speech forward/backward) | High level activation |

| Heelmann et al. (2010) [52] | 6 | 5 VS 1 MCS |

<2 months, 6–14 months | Visual (flash) | High (MCS) and low (VS) level activation |

| Active Task fMRI Studies | |||||

| Owen et al. (2006) [38] | 1 | VS | 5 months | Motor and spatial mental imagery | Activation of SMA for motor task. Activation of PHG, PPC, and PMC for spatial task |

| Monti et al. (2010) [53] | 54* | 23 VS 31 MCS |

1 month – 25 years | Motor and spatial mental imagery | Activation of SMA for motor task in 4 VS and 1 MCS. Activation of PHG for spatial task in 3 VS and 1 MCS. Also, 1 MCS patient provided correct responses to yes (motor imagery) or no (spatial imagery) in expected brain regions in 5 of 6 questions. |

| Rodriguez Moreno et al. (2010) [43] | 10* | 3 VS 5 MCS 1 EMCS 1 LIS |

2 months – 7 years | Silent picture naming | Activation of left superior temporal, inferior frontal and pre-SMA in 1 VS, 2 MCS, 1 LIS, 1 EMCS. |

| Bekinschtein et al. (2011) [54] | 5* | VS | 5 – 20 months | Motor task | Activation of contralateral dorsal PMC in 2VS |

| Bardin et al. (2011) [55] | 7* | 6 MCS 1 LIS |

6 months – 3 years | Motor mental imagery (6 subjects), binary and multiple choice tasks (4 subjects) | Activation of SMA in 2 MCS, 1 LIS during motor imagery task. Incorrect responses in expected brain regions in 1 MCS in binary/multiple choice tasks. |

| Monti et al. (2013) [42] | 1 | MCS | 18 months | Visual (light, color, motion, shapes, objects, voluntary visual attention) | Activation in the right FFA when instructed to look at face. Activation in PPA when instructed to focus on house. |

Adapted from Laureys and Schiff [32]. Detailed neurological examination data from the time of injury are not provided in all of the above studies. We therefore included all studies in which at least one TBI patient was classified as having a severe TBI (typically based on an admission Glasgow Coma Scale score ≤ 8).

An asterisk (*) indicates a study that enrolled subjects with both TBI and non-TBI. The term “low level activation” refers to activation within primary sensory cortices, whereas “high level activation” refers to activation that is believed to indicate intentional perception.

Abbreviations: Dx diagnosis, DTI diffusion tensor imaging, EMCS emerged from minimally conscious state, FFA fusiform face area, LIS locked-in syndrome, MCS minimally conscious state, PHG parahippocampal gyrus, PMC, premotor cortex, PPC posterior parietal cortex, PPA parahippocampal place area, SMA supplementary motor area, VS vegetative state.

Limitations of Task-Based fMRI and Considerations for Clinical Implementation

As clinicians consider incorporating fMRI into the prognostic evaluation of patients with traumatic coma and other DOC, it is important to emphasize that the sensitivity and specificity of these techniques for detecting evidence of conscious awareness remains unknown pending large, multi-center studies. Along these lines, an international consortium of neuroimaging centers funded by the James S. McDonnell Foundation has launched an initiative to develop common structural and functional imaging paradigms to inform diagnosis and prognosis. There are also several methodological considerations that may affect fMRI data interpretation. These include patient motion, sedation, and delayed responses to stimuli due to slow cognitive processing [55]. Furthermore, standardized methods for analyzing BOLD fMRI data in the traumatic DOC population have not been adequately validated, and recent evidence suggests that a newly developed multivariate pattern analysis classification approach may be superior to the more commonly used general linear model-based univariate approach [56]. These methodological issues and potential confounders suggest that further research is needed before stimulus-based fMRI can become part of the routine assessment of patients with traumatic coma and other DOCs.

Resting-State Functional MRI (rs-fMRI)

Principles and Methods

Rs-fMRI is based on the principle that spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity are temporally correlated in functionally related brain regions at rest. Identification of resting correlations in brain activity has led to the concept of “resting state networks,” which include the “default mode network” (DMN) [57–60], “salience network” [61], thalamocortical networks [62], and the “executive control network” [61]. Notably, activity within the DMN typically decreases during active, goal-directed cognitive tasks, a physiologic property of the brain that has led to the concept of anticorrelated “task positive” and “task negative” networks [63]. From a methodological standpoint, functional connectivity within a network is defined by temporal correlations in the low frequency (<0.1 Hz), spontaneous fluctuations of the BOLD signal [64]. Rs-fMRI network connectivity can be analyzed using a variety of approaches, which include independent component analysis, frequency domain analysis and seed-based techniques [65–68]. In the latter approach, a region of interest is placed in a central hub within a network and the connected hubs are identified based on the correlations in spontaneous fluctuations of the BOLD signal.

Rs-fMRI Correlations with Outcome in Traumatic Coma

To date, the resting state network that has received the most attention in patients recovering from traumatic coma is the DMN. The grey matter nodes of this widely distributed network include the posterior cingulate/retrosplenial cortex, precuneus, medial prefrontal cortex, inferior parietal lobule (angular gyrus and supramarginal gyrus), and hippocampal formation [69, 70]. Several studies have demonstrated that DMN connectivity is altered in patients recovering from traumatic coma [71–77] (Table 2). In addition, longitudinal increases in DMN connectivity have been correlated with functional recovery [72], and the severity of DMN dysfunction has been shown to predict neurocognitive task performance [71, 73, 74]. Moreover, functional connectivity of cortical nodes within the DMN, as measured by rs-fMRI, correlates with the structural injury of white matter pathways connecting these nodes, as measured by DTI [71, 73, 74]. This correlative rs-fMRI/DTI finding suggests that functional connectivity measurements may be firmly rooted in structural neuroanatomy, as has been similarly shown in healthy human control subjects [78, 79]. Perhaps most notably, the strength of functional connectivity within the DMN, as determined by rs-fMRI, has been to shown to correlate linearly with the level of consciousness after traumatic coma, as determined by the CRS-R [76].

Table 2.

Resting-state fMRI studies in patients recovering from traumatic coma

| Authors (year) | N | Dx | Time to fMRI | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cauda et al. (2009) [75] | 3* | VS | 20 months | DMN disconnections |

| Vanhaudenhuyse et al. (2010) [76] | 14* | 5 Coma 4 VS 4 MCS 1 LIS |

<1 month – 5 years | DMN connectivity correlates with level of consciousness (LIS > MCS > VS > Coma). |

| Sharp et al. (2011) [71] | 20* | Prior Severe TBI |

6 months – 6 years | DMN connectivity increased in TBI patients vs. controls. Higher DMN connectivity correlated with better neurocognitive test performance and less white matter injury on DTI. |

| Hillary et al. (2011) [72] | 10 | Prior Severe TBI |

3 and 6 months after emerging from PTA | Increased DMN connectivity in TBI patients versus controls during first 6 months of recovery after emergence from PTA. |

| Bonnelle et al. (2011) [73] | 28 | Prior Severe TBI |

3 months – 6 years | Decreased resting DMN functional connectivity, and increased DMN activation during an attention task, both correlate with sustained attention impairment and with DMN white matter injury detected by DTI. |

| Bonnelle et al. (2012) [74] | 57 | Prior Severe TBI |

2 months – 8 years | Decreased deactivation in nodes of DMN (e.g., precuneus, posterior cingulate cortex) during a stop-signal task. Note: rs-fMRI analysis was not performed; rather deactivation of the DMN during an active task was analyzed. |

| Soddu et al. (2012) [77] | 11* | 8 VS 1 MCS 2 LIS |

1 month – 4 years | Decreased DMN connectivity in VS compared to LIS and controls. Unilateral DMN connectivity present in MCS patient, which correlated with PET measurements of metabolic activity. |

| Ovadia-Caro et al. (2012) [100] | 8* | 1 BD 2 Coma 2 VS 2 MCS 1 LIS |

1 week – 4 years | Resting connectivity in the extrinsic “task positive” network decreased in patients versus controls. Inter-hemispheric functional connectivity correlated with level of consciousness. |

Adapted from Laureys and Schiff [32]. Of note, detailed neurological examination data from the time of injury are not always provided in the above studies. We therefore included all studies in which at least one TBI patient was classified as having a severe TBI (typically based on an admission Glasgow Coma Scale score ≤ 8).

An asterisk (*) indicates a study that enrolled subjects with both TBI and non-TBI.

Abbreviations: BD brain dead, DMN default mode network, Dx diagnosis, DTI diffusion tensor imaging, LIS locked-in syndrome, MCS minimally conscious state, PET positron emission tomography, PTA post-traumatic amnesia, VS vegetative state.

Limitations of rs-fMRI and Considerations for Clinical Implementation

Several important limitations to the rs-fMRI technique should be considered. First, the BOLD signal in rs-fMRI studies (and task-based fMRI studies) is affected by CBF, blood volume and oxygen consumption, and therefore is not a direct measure of neuronal activity. Second, the BOLD signal reflects changes in venous blood oxygenation that cannot be quantified in an absolute manner or with physiologic units. Third, there are potential sources of artifacts in the rs-fMRI signal that are not related to neuronal activity or cerebrovascular hemodynamics. These include the behavioral state of the patient (i.e., eyes closed, eyes open and inattentive, or eyes open and fixated on a visual target) [80], as well as hardware noise [81] and physiological artifacts such as respiration and cardiac pulsation [77]. Care must therefore be taken when comparing results across cohorts that the data were acquired under similar study conditions and that potential artifacts are appropriately accounted for.

Arterial-spin Labeled (ASL) Perfusion MRI

Principles and Methods

ASL perfusion MRI utilizes a radiofrequency pulse to label water protons in blood flowing through the carotid arteries by inverting their spins, thereby generating an endogenous contrast. The dissipation of these labeled spins in the distal cerebral vasculature provides an indirect measure of CBF. ASL can also be used in stimulus-based fMRI studies to detect brain activation in response to a stimulus or a cognitive task, by pair-wise subtraction of the MRI signal acquired during labeled and unlabeled acquisitions [31]. The ASL technique provides several methodological advantages, in that it can be performed rapidly [82], it has high test-retest reliability [83], and it can be repeated within a single scanning session to measure longitudinal changes in CBF [84]. Furthermore, unlike BOLD, ASL provides a direct measurement of arterial perfusion that can theoretically be quantified in absolute units of CBF (cc/100 gm/min) if the longitudinal relaxation rate of blood and tissue, as well as the labeling efficiency and arterial transit delays are known. The ASL signal should therefore correlate directly with neuronal activity as long as cerebrovascular autoregulation and activation-flow-coupling mechanisms are intact [31].

ASL Perfusion MRI Correlations with Outcome in Traumatic Coma

ASL perfusion imaging studies have revealed alterations in global and regional resting CBF in patients recovering from traumatic coma. Patients in the chronic stage of moderate-to-severe TBI have reduced global CBF in the resting state, as well as decreased regional perfusion in the thalamus, posterior cingulate cortex, and frontal cortex [85]. Reductions in thalamic perfusion correlate with thalamic atrophy, suggesting that ASL perfusion measurements may reflect the functional capacity of injured neurons. Furthermore, a correlation has been observed between decreased resting CBF in a neuroanatomic region and altered task-related activation of that region during an ASL fMRI working memory paradigm [86]. These findings suggest that ASL measurements of resting CBF may predict functional potential for recovery.

ASL perfusion MRI has also been used to characterize global and regional changes in CBF associated with traumatic DOC. In one ASL study of patients with traumatic MCS, CBF was preserved in the precuneus/posterior cingulate region but was decreased in the anterior nodes of the DMN (e.g., medial prefrontal cortex) [87]. These findings suggest reintegration of the posterior cingulate/precuneus into the DMN may be necessary for the transition from VS to MCS to occur, whereas reintegration of the medial prefrontal cortex into the DMN may be necessary for emergence from MCS. Indeed, several fMRI and positron emission tomography studies support these ASL results by showing that VS is associated with decreased function within the posterior nodes of the DMN [76, 88, 89], and recovery of metabolic activity and/or perfusion within these nodes is associated with recovery of conscious awareness [76, 88].

Limitations of ASL Perfusion MRI and Considerations for Clinical Implementation

Several potential confounders should be considered when interpreting the results of an ASL study in a patient recovering from traumatic coma. First, cerebrovascular autoregulation may be altered, and thus the ASL (and BOLD) signals may be confounded by decoupling of neural activity from CBF. Second, the manner in which the radiofrequency pulse is applied to label water protons in carotid blood may affect the perfusion measurements. Currently available labeling schemes include pulsed ASL, continuous ASL, pseudocontinuous ASL and velocity-selective ASL. A discussion of the specific features of each ASL technique is beyond the scope of this review, but we wish to emphasize that signal-to-noise properties vary among the techniques, and there is no current consensus regarding the optimal labeling scheme. Therefore, cross-center comparisons may be confounded. Third, variability in the transit time for radiofrequency-labeled blood to flow from the tagging region to downstream sites of image acquisition can confound ASL perfusion measurements in patients with extracranial and/or intracranial cerebrovascular stenoses. Finally, ASL relies on relatively small signal differences compared to BOLD signal changes, and it is therefore particularly susceptible to artifacts, such as those caused by EEG leads or patient motion. Currently, versions of pseudocontinuous ASL are available from three major MRI scanner manufacturers as either product or research sequences, but for commercially available ASL sequences, the reproducibility of results across scanner manufacturers has yet to be established.

Prognostic Utility of Task-Based fMRI vs. rs-fMRI vs. ASL Perfusion MRI

In considering the relative prognostic utility of each respective technique, it is important to emphasize that there is currently insufficient data to evaluate the prognostic value of any of these techniques individually, much less to compare them. Nonetheless, the studies summarized above have begun to provide critical insights into the settings in which each respective tool might provide prognostic value. With regard to the timing of data acquisition and prognostication, the administration of sedative medications during the acute stage of traumatic coma can clearly alter a patient’s ability to respond to an imagery task or auditory stimulus [90], and therefore task-related fMRI may not be an ideal technique to pursue acutely. In contrast, rs-fMRI may be used to investigate resting state networks across the spectrum of states of consciousness, throughout each stage of the sleep-wake cycle, and even during anesthesia [67, 91, 92], although interpretation of the results may be confounded by altered metabolic status. Another important advantage of the rs-fMRI technique is its ability to analyze multiple resting state networks within a single dataset, thereby reducing data acquisition time for patients with traumatic coma who may not be able to tolerate a prolonged MRI scan needed to investigate multiple tasks. A major advantage of ASL is its ability to provide direct repeated measurements of global and/or regional CBF within the same scanning session, before and after administration of a therapy. ASL may thus be used to detect individualized responses to stimulant medications [84], providing potentially relevant therapeutic and prognostic information about the potential for activation of latent neural networks.

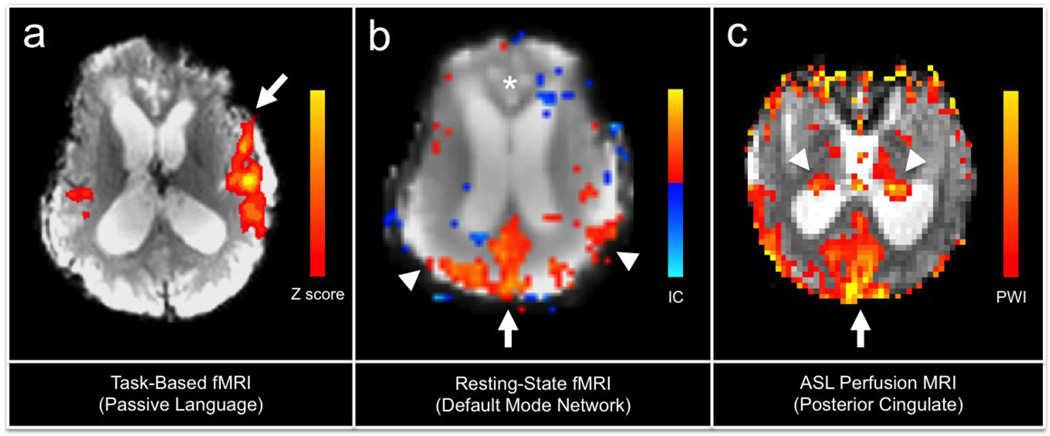

Importantly, task-based fMRI currently has the most data supporting its use as a tool for detecting evidence of conscious awareness, which has significant prognostic relevance given that patients in post-traumatic MCS have been shown to have greater potential for recovery than patients in post-traumatic VS. Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that task-based fMRI paradigms may be used to investigate brain processing of pain [93], which is of critical importance to the care of patients recovering from traumatic coma who may not be able to verbalize discomfort. Ultimately, the multimodal integration of task-based fMRI, rs-fMRI, and ASL perfusion MRI is likely to provide the highest prognostic yield, since each technique provides potentially unique information about the functional status of the injured brain (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Task-based fMRI, resting-state fMRI, and arterial-spin labeled (ASL) perfusion MRI data from a 23-year-old woman scanned 146 days (5 months) after traumatic coma caused by a motor vehicle accident. At the time of the scan, the patient was in a minimally conscious state according to a standardized examination on the Coma Recovery Scale-Revised. In (a), activation within the left (arrow) > right hemispheric peri-Sylvian language networks is observed during a passive language stimulus (spoken narrative). FMRI data processing was carried out using FEAT (FMRI Expert Analysis Tool) Version 5.98, part of FSL (FMRIB's Software Library, www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl), and the color scalar bar indicates the Z scores. In (b), an independent component resting-state fMRI analysis reveals that the posterior cingulate/precuneus region of the default mode network (arrow) retains partial functional connectivity with the inferior parietal lobules (arrow heads), but connectivity with the medial prefrontal cortex (*) has been disrupted. Independent component analysis was carried out using Probabilistic Independent Component Analysis [66] as implemented in MELODIC (Multivariate Exploratory Linear Decomposition into Independent Components) Version 3.10, part of FSL. The color scalar bar indicates the thresholded independent component (IC) map, with yellow-red colors indicating positive correlations, and blue colors indicating negative correlations (anticorrelations). In (c), an ASL perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI) map using pulsed ASL demonstrates cerebral perfusion in the posterior cingulate/precuneus region (arrow) and thalami (arrow heads). The color scalar bar indicates relative cerebral perfusion.

Future Directions

Although major advances have been made in recent years in understanding the functional basis of awareness in patients with traumatic DOC, current understanding about arousal (wakefulness) lags far behind. Arousal is critical to the recovery of consciousness, since without arousal awareness is not possible. The current lack of understanding about the pathophysiological mechanisms that cause altered arousal in traumatic DOC can be explained by the inability of conventional imaging tools to identify the complex neuroanatomic connectivity of the brainstem ascending reticular activating system (ARAS). Since the discovery of the ARAS by Moruzzi and Magoun in 1949 [94], the vast majority of structural and functional analyses of this arousal network have been performed in animal models [95]. Indeed, the neuroanatomic connectivity of the human ARAS has only recently being mapped in preliminary ex vivo and in vivo tractography studies [96, 97].

For clinicians to accurately determine a patient’s chances of recovery, advanced imaging techniques must be developed to delineate the functional integrity of not only the hemispheric pathways that mediate awareness, but also the ARAS pathways that mediate arousal. This goal is fundamentally important to predicting recovery after traumatic coma, because the human ARAS network appears to contain redundant circuitry that may enable recovery of arousal when some, but not all components of the network are disrupted [98].

Finally, if fMRI data are to be integrated into clinical practice, it remains to be determined whether the data should be analyzed in each TBI patient’s “native space,” or whether each patient’s data should be normalized to a standard neuroanatomic atlas, such as the coordinate system of the Montreal Neurological Institute atlas (MNI152 also known as ICBM152) [99]. Normalization enables population-based analyses and group comparisons of fMRI data and is typically feasible in patients with mild-to-moderate TBI but can be difficult in severe TBI patients with tissue shifts and mass effects.

Major methodological hurdles remain and significant additional research addressing sensitivity/specificity and positive/negative predictive value is needed before the functional neuroimaging techniques discussed in this review can be implemented into clinical practice. Furthermore, automated analysis tools will need to be developed and validated in this patient population to enable rapid, robust and reproducible interpretation of advanced imaging data at the point of care, so that clinicians are able to use these data to inform clinical decisions. Nevertheless, just as conventional MRI has been shown to be superior to CT for prognostication in traumatic coma, there is a rapidly growing body of evidence that functional neuroimaging techniques will surpass conventional MRI in their prognostic utility [20].

Conclusions

Task-based fMRI, rs-fMRI, and ASL perfusion MRI have the potential to provide clinically relevant information about the functional integrity of neural networks that are critical to recovery of consciousness and independent function. As advances in functional neuroimaging begin to elucidate the complex pathophysiology of traumatic coma and the mechanisms of recovery, a major challenge that will confront clinicians is how to apply these advanced imaging techniques to the benefit of their patients on an individualized basis. With each new technology, there are a myriad of methodological factors that must be considered for accurate interpretation. Nevertheless, as standardized protocols for data acquisition and analysis are validated and implemented, we expect that fMRI, rs-fMRI, and ASL perfusion MRI, when used in association with standardized neurobehavioral methods, will improve the accuracy of prognostication, facilitate the development of novel therapies, and allow families to make more informed decisions about goals of care.

Acknowledgments

The contents of this manuscript were developed with support from the National Institutes of Health (R25NS065743), the Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology (Boston, MA), and the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, United States Department of Education (H133A120085 [Spaulding-Harvard TBI Model System]). However, the contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and endorsement by the federal government should not be assumed.

Joseph T. Giacino has been a consultant for Craig Rehabilitation Hospital and Frazier Rehabilitation Hospital; has served as an expert witness consultant on 5 legal cases over the last 36 months involving patients with disorders of consciousness concerning diagnosis, prognosis, pain and suffering and adequacy of treatment; and has received grant support from James S. McDonnell Foundation.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Brian L. Edlow declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ona Wu declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Brian L. Edlow, Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street – Lunder 650, Boston, MA 02114, USA, bedlow@partners.org

Joseph T. Giacino, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, 300 First Avenue, Charlestown, MA 02129, USA, jgiacino@partners.org

Ona Wu, Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, 149 13th Street, CNY 2301, Charlestown, MA 02129, USA, ona@nmr.mgh.harvard.edu

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

* Of importance

** Of major importance

- 1.Bruns J, Jr, Hauser WA. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: a review. Epilepsia. 2003;44(Suppl 10):2–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.44.s10.3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faul M, Xu L, Wald MM, et al. Traumatic brain injury in the United States: emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths. Atlanta (GA): Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perel P, Arango M, Clayton T, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: practical prognostic models based on large cohort of international patients. BMJ. 2008;336:425–429. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39461.643438.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell RS, Vo AH, Neal CJ, et al. Military traumatic brain and spinal column injury: a 5-year study of the impact blast and other military grade weaponry on the central nervous system. J Trauma. 2009;66:S104–S111. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31819d88c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DuBose JJ, Barmparas G, Inaba K, et al. Isolated severe traumatic brain injuries sustained during combat operations: demographics, mortality outcomes, and lessons to be learned from contrasts to civilian counterparts. J Trauma. 2011;70:11–16. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318207c563. discussion 6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jennett B, Plum F. Persistent vegetative state after brain damage. A syndrome in search of a name. Lancet. 1972;1:734–737. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)90242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giacino JT, Ashwal S, Childs N, et al. The minimally conscious state: definition and diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 2002;58:349–353. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz DI, Polyak M, Coughlan D, et al. Natural history of recovery from brain injury after prolonged disorders of consciousness: outcome of patients admitted to inpatient rehabilitation with 1–4 year follow-up. Prog Brain Res. 2009;177:73–88. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17707-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zoroya G. For troops with brain trauma, a long journey back. USA Today. Tampa. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakase-Richardson R, Whyte J, Giacino JT, et al. Longitudinal outcome of patients with disordered consciousness in the NIDRR TBI Model Systems Programs. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:59–65. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNamee S, Howe L, Nakase-Richardson R, et al. Treatment of disorders of consciousness in the Veterans Health Administration polytrauma centers. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2012;27:244–252. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e31825e12c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skandsen T, Kvistad KA, Solheim O, et al. Prognostic value of magnetic resonance imaging in moderate and severe head injury: a prospective study of early MRI findings and one-year outcome. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:691–699. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gennarelli TA, Spielman GM, Langfitt TW, et al. Influence of the type of intracranial lesion on outcome from severe head injury. J Neurosurg. 1982;56:26–32. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.56.1.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lammi MH, Smith VH, Tate RL, et al. The minimally conscious state and recovery potential: a follow-up study 2 to 5 years after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:746–754. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estraneo A, Moretta P, Loreto V, et al. Late recovery after traumatic, anoxic, or hemorrhagic long-lasting vegetative state. Neurology. 2010;75:239–245. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e8e8cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luaute J, Maucort-Boulch D, Tell L, et al. Long-term outcomes of chronic minimally conscious and vegetative states. Neurology. 2010;75:246–252. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e8e8df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray GD, Butcher I, McHugh GS, et al. Multivariable prognostic analysis in traumatic brain injury: results from the IMPACT study. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:329–337. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Firsching R, Woischneck D, Diedrich M, et al. Early magnetic resonance imaging of brainstem lesions after severe head injury. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:707–712. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.5.0707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lagares A, Ramos A, Perez-Nunez A, et al. The role of MR imaging in assessing prognosis after severe and moderate head injury. Acta neurochirurgica. 2009;151:341–356. doi: 10.1007/s00701-009-0194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edlow BL, Wu O. Advanced neuroimaging in traumatic brain injury. Seminars in Neurology. 2012;32:372–398. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1331810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andrews K, Murphy L, Munday R, et al. Misdiagnosis of the vegetative state: retrospective study in a rehabilitation unit. BMJ. 1996;313:13–16. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7048.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Childs NL, Mercer WN, Childs HW. Accuracy of diagnosis of persistent vegetative state. Neurology. 1993;43:1465–1467. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.8.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schnakers C, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Giacino J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the vegetative and minimally conscious state: clinical consensus versus standardized neurobehavioral assessment. BMC neurology. 2009;9:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giacino JT, Kalmar K, Whyte J. The JFK Coma Recovery Scale-Revised: measurement characteristics and diagnostic utility. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:2020–2029. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giacino JT, Kalmar K. The vegetative and minimally conscious states: A comparison of clinical features and functional outcome. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1997;12:36–51. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giacino JT, Whyte J, Bagiella E, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of amantadine for severe traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:819–826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whyte J, Myers R. Incidence of clinically significant responses to zolpidem among patients with disorders of consciousness: a preliminary placebo controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88:410–418. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181a0e3a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schiff ND, Giacino JT, Kalmar K, et al. Behavioural improvements with thalamic stimulation after severe traumatic brain injury. Nature. 2007;448:600–603. doi: 10.1038/nature06041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwong KK, Belliveau JW, Chesler DA, et al. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of human brain activity during primary sensory stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5675–5679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ogawa S, Tank DW, Menon R, et al. Intrinsic signal changes accompanying sensory stimulation: functional brain mapping with magnetic resonance imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5951–5955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Detre JA, Wang J. Technical aspects and utility of fMRI using BOLD and ASL. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;113:621–634. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laureys S, Schiff ND. Coma and consciousness: paradigms (re)framed by neuroimaging. Neuroimage. 2012;61:478–491. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donaldson DI, Buckner RL. Effective paradigm design. In: Jezzard P, Matthews PM, Smith SM, editors. Functional MRI: An introduction to methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kasahara M, Menon DK, Salmond CH, et al. Traumatic brain injury alters the functional brain network mediating working memory. Brain Inj. 2011;25:1170–1187. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2011.608210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palacios EM, Sala-Llonch R, Junque C, et al. White matter integrity related to functional working memory networks in traumatic brain injury. Neurology. 2012;78:852–860. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824c465a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kasahara M, Menon DK, Salmond CH, et al. Altered functional connectivity in the motor network after traumatic brain injury. Neurology. 2010;75:168–176. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e7ca58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newsome MR, Scheibel RS, Hanten G, et al. Brain activation while thinking about the self from another person's perspective after traumatic brain injury in adolescents. Neuropsychology. 2010;24:139–147. doi: 10.1037/a0017432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Owen AM, Coleman MR, Boly M, et al. Detecting awareness in the vegetative state. Science. 2006;313:1402. doi: 10.1126/science.1130197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newcombe VF, Williams GB, Scoffings D, et al. Aetiological differences in neuroanatomy of the vegetative state: insights from diffusion tensor imaging and functional implications. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:552–561. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.196246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Coleman MR, Davis MH, Rodd JM, et al. Towards the routine use of brain imaging to aid the clinical diagnosis of disorders of consciousness. Brain. 2009;132:2541–2552. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp183. In this fMRI study of 41 patients with VS (n=22) and MCS (n=19), a passive language stimulus was used to investigate language networks. Hierarchical language-related fMRI activation patterns correlated with the degree of behavioral recovery 6 months after the fMRI scan.

- 41.Coleman MR, Rodd JM, Davis MH, et al. Do vegetative patients retain aspects of language comprehension? Evidence from fMRI. Brain. 2007;130:2494–2507. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monti MM, Pickard JD, Owen AM. Visual cognition in disorders of consciousness: From V1 to top-down attention. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013;34:1245–1253. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodriguez Moreno D, Schiff ND, Giacino J, et al. A network approach to assessing cognition in disorders of consciousness. Neurology. 2010;75:1871–1878. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181feb259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schiff ND, Rodriguez-Moreno D, Kamal A, et al. fMRI reveals large-scale network activation in minimally conscious patients. Neurology. 2005;64:514–523. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150883.10285.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernandez-Espejo D, Junque C, Vendrell P, et al. Cerebral response to speech in vegetative and minimally conscious states after traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2008;22:882–890. doi: 10.1080/02699050802403573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bekinschtein T, Leiguarda R, Armony J, et al. Emotion processing in the minimally conscious state. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:788. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.034876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bekinschtein T, Tiberti C, Niklison J, et al. Assessing level of consciousness and cognitive changes from vegetative state to full recovery. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2005;15:307–322. doi: 10.1080/09602010443000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Di HB, Yu SM, Weng XC, et al. Cerebral response to patient's own name in the vegetative and minimally conscious states. Neurology. 2007;68:895–899. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000258544.79024.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu J, Wu X, Gao L, et al. Cortical activity after emotional visual stimulation in minimally conscious state patients. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:677–688. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qin P, Di H, Liu Y, et al. Anterior cingulate activity and the self in disorders of consciousness. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31:1993–2002. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fernandez-Espejo D, Junque C, Cruse D, et al. Combination of diffusion tensor and functional magnetic resonance imaging during recovery from the vegetative state. BMC neurology. 2010;10:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-10-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heelmann V, Lippert-Gruner M, Rommel T, et al. Abnormal functional MRI BOLD contrast in the vegetative state after severe traumatic brain injury. International journal of rehabilitation research Internationale Zeitschrift fur Rehabilitationsforschung Revue internationale de recherches de readaptation. 2010;33:151–157. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0b013e328331c5b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Monti MM, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Coleman MR, et al. Willful modulation of brain activity in disorders of consciousness. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:579–589. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905370. This study includes the largest cohort of patients with DOC to be assessed with spatial and motor imagery fMRI paradigms (n=54). Five of 54 patients (all with TBI) had patterns of brain activation during the command-following paradigms that were similar to controls, and one patient in MCS could link the two imagery tasks to “yes” and “no” answers.

- 54.Bekinschtein TA, Manes FF, Villarreal M, et al. Functional imaging reveals movement preparatory activity in the vegetative state. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2011;5:5. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2011.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bardin JC, Fins JJ, Katz DI, et al. Dissociations between behavioural and functional magnetic resonance imaging-based evaluations of cognitive function after brain injury. Brain. 2011;134:769–782. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bardin JC, Schiff ND, Voss HU. Pattern classification of volitional functional magnetic resonance imaging responses in patients with severe brain injury. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:176–181. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, et al. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raichle ME, Snyder AZ. A default mode of brain function: a brief history of an evolving idea. Neuroimage. 2007;37:1083–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.041. discussion 97-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shulman GL, Fiez JA, Corbetta M, et al. Common blood flow changes across visual tasks: II. Decreases in cerebral cortex. J Cogn Neurosci. 1997;9:648–663. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.5.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Binder JR, Frost JA, Hammeke TA, et al. Conceptual processing during the conscious resting state. A functional MRI study. J Cogn Neurosci. 1999;11:80–95. doi: 10.1162/089892999563265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2349–2356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tang L, Ge Y, Sodickson DK, et al. Thalamic resting-state functional networks: disruption in patients with mild traumatic brain injury. Radiology. 2011;260:831–840. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, et al. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9673–9678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, et al. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:537–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fox MD, Greicius M. Clinical applications of resting state functional connectivity. Frontiers in s ystems neuroscience. 2010;4:19. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beckmann CF, Smith SM. Probabilistic independent component analysis for functional magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2004;23:137–152. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.822821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boly M, Phillips C, Tshibanda L, et al. Intrinsic brain activity in altered states of consciousness: how conscious is the default mode of brain function? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1129:119–129. doi: 10.1196/annals.1417.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Biswal BB, Mennes M, Zuo XN, et al. Toward discovery science of human brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4734–4739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911855107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain's default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:1–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fransson P, Marrelec G. The precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex plays a pivotal role in the default mode network: Evidence from a partial correlation network analysis. Neuroimage. 2008;42:1178–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sharp DJ, Beckmann CF, Greenwood R, et al. Default mode network functional and structural connectivity after traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2011;134:2233–2247. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hillary FG, Slocomb J, Hills EC, et al. Changes in resting connectivity during recovery from severe traumatic brain injury. International journal of psychophysiology : official journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology. 2011;82:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bonnelle V, Leech R, Kinnunen KM, et al. Default mode network connectivity predicts sustained attention deficits after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2011;31:13442–13451. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1163-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bonnelle V, Ham TE, Leech R, et al. Salience network integrity predicts default mode network function after traumatic brain injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4690–4695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113455109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cauda F, Micon BM, Sacco K, et al. Disrupted intrinsic functional connectivity in the vegetative state. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:429–431. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.142349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Vanhaudenhuyse A, Noirhomme Q, Tshibanda LJ, et al. Default network connectivity reflects the level of consciousness in non-communicative brain-damaged patients. Brain. 2010;133:161–171. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp313. In this rs-fMRI study of patients with coma (n=5), VS (n=4), MCS (n=4) and LIS (n=1), the strength of functional connectivity within the DMN correlated linearly with the level of consciousness.

- 77.Soddu A, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Bahri MA, et al. Identifying the default-mode component in spatial IC analyses of patients with disorders of consciousness. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33:778–796. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Teipel SJ, Bokde AL, Meindl T, et al. White matter microstructure underlying default mode network connectivity in the human brain. Neuroimage. 2010;49:2021–2032. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Greicius MD, Supekar K, Menon V, et al. Resting-state functional connectivity reflects structural connectivity in the default mode network. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:72–78. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yan C, Liu D, He Y, et al. Spontaneous brain activity in the default mode network is sensitive to different resting-state conditions with limited cognitive load. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jo HJ, Saad ZS, Simmons WK, et al. Mapping sources of correlation in resting state FMRI, with artifact detection and removal. Neuroimage. 2010;52:571–582. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.04.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fernandez-Seara MA, Edlow BL, Hoang A, et al. Minimizing acquisition time of arterial spin labeling at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:1467–1471. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen Y, Wang DJ, Detre JA. Test-retest reliability of arterial spin labeling with common labeling strategies. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;33:940–949. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kim J, Whyte J, Patel S, et al. Methylphenidate modulates sustained attention and cortical activation in survivors of traumatic brain injury: a perfusion fMRI study. Psychopharmacology. 2012;222:47–57. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2622-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim J, Whyte J, Patel S, et al. Resting cerebral blood flow alterations in chronic traumatic brain injury: an arterial spin labeling perfusion FMRI study. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1399–1411. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kim J, Whyte J, Patel S, et al. A Perfusion fMRI Study of the Neural Correlates of Sustained-Attention and Working-Memory Deficits in Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2012;26:870–880. doi: 10.1177/1545968311434553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Liu AA, Voss HU, Dyke JP, et al. Arterial spin labeling and altered cerebral blood flow patterns in the minimally conscious state. Neurology. 2011;77:1518–1523. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318233b229. In this ASL perfusion MRI study of patients with traumatic MCS, cerebral blood flow was preserved in the precuneus/posterior cingulate region but was decreased in the anterior nodes of the DMN (e.g., medial prefrontal cortex).

- 88.Laureys S, Lemaire C, Maquet P, et al. Cerebral metabolism during vegetative state and after recovery to consciousness. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:121. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Silva S, Alacoque X, Fourcade O, et al. Wakefulness and loss of awareness: brain and brainstem interaction in the vegetative state. Neurology. 2010;74:313–320. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cbcd96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brown EN, Lydic R, Schiff ND. General anesthesia, sleep, and coma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2638–2650. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0808281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Greicius MD, Kiviniemi V, Tervonen O, et al. Persistent default-mode network connectivity during light sedation. Hum Brain Mapp. 2008;29:839–847. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fukunaga M, Horovitz SG, van Gelderen P, et al. Large-amplitude, spatially correlated fluctuations in BOLD fMRI signals during extended rest and early sleep stages. Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:979–992. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wager TD, Atlas LY, Lindquist MA, et al. An fMRI-based neurologic signature of physical pain. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1388–1397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moruzzi G, Magoun HW. Brain stem reticular formation and activation of the EEG. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1949;1:455–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Steriade M. Arousal: revisiting the reticular activating system. Science. 1996;272:225–226. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Edlow BL, Takahashi E, Wu O, et al. Neuroanatomic connectivity of the human ascending arousal system critical to consciousness and its disorders. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71:531–546. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182588293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Edlow BL, Haynes RL, Takahashi E, et al. Disconnection of the ascending arousal system in traumatic coma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013 doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182945bf6. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Parvizi J, Damasio AR. Neuroanatomical correlates of brainstem coma. Brain. 2003;126:1524–1536. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mazziotta J, Toga A, Evans A, et al. A probabilistic atlas and reference system for the human brain: International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM) Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:1293–1322. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ovadia-Caro S, Nir Y, Soddu A, et al. Reduction in inter-hemispheric connectivity in disorders of consciousness. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]