Abstract

SUMMARY

Daptomycin is a lipopeptide antimicrobial with in vitro bactericidal activity against Gram-positive bacteria that was first approved for clinical use in 2004 in the United States. Since this time, significant data have emerged regarding the use of daptomycin for the treatment of serious infections, such as bacteremia and endocarditis, caused by Gram-positive pathogens. However, there are also increasing reports of daptomycin nonsusceptibility, in Staphylococcus aureus and, in particular, Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis. Such nonsusceptibility is largely in the context of prolonged treatment courses and infections with high bacterial burdens, but it may occur in the absence of prior daptomycin exposure. Nonsusceptibility in both S. aureus and Enterococcus is mediated by adaptations to cell wall homeostasis and membrane phospholipid metabolism. This review summarizes the data on daptomycin, including daptomycin's unique mode of action and spectrum of activity and mechanisms for nonsusceptibility in key pathogens, including S. aureus, E. faecium, and E. faecalis. The challenges faced by the clinical laboratory in obtaining accurate susceptibility results and reporting daptomycin MICs are also discussed.

INTRODUCTION

In the era of antimicrobial resistance, there is a diminishing arsenal for the treatment of serious infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-positive bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE). Vancomycin is almost universally accepted as the first-line drug of choice for the treatment of known or suspected MRSA infections (1). However, multiple shortcomings for vancomycin have been recognized, including less rapid bactericidal activity than that of β-lactams (2, 3) and poor tissue and intracellular penetration. Reduced vancomycin antistaphylococcal activity (vancomycin MIC creep) has been observed in recent years at some institutions (4–6), albeit it was not identified in a U.S.-wide, multi-institutional study, suggesting considerable interhospital variability (7). Further, many studies have demonstrated that vancomycin MICs at the high end of susceptible (e.g., 2 μg/ml) are independently associated with mortality in patients with MRSA bloodstream infections (8). This finding may in part be attributed to difficulty in attaining appropriate vancomycin serum concentrations and, hence, adequate target area under the curve (AUC)/MIC ratios in these patients. Interestingly, vancomycin MICs of 2 μg/ml were also associated with mortality in patients who were treated with flucloxacillin for bacteremia caused by methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) in a single study (9). This may indicate that other pathogen factors are hidden within this microbiological phenotype and are responsible for the vancomycin MIC-mortality relationship.

Treatment options for VRE are extremely limited given the paucity of antimicrobials with activity against this organism. Linezolid and quinupristin-dalfopristin, which are both bacteriostatic in vivo, are the only antimicrobials approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for VRE infection. Quinupristin-dalfopristin has no activity against Enterococcus faecalis, has a high frequency (>30%) of painful myalgias, and is limited to a central catheter route of administration. Linezolid treatment is associated with reversible myelosuppression, mostly in the form of thrombocytopenia, which limits the treatment course of linezolid for some patients to less than 2 weeks (10).

Daptomycin, a lipopeptide with in vitro bactericidal activity against Gram-positive bacteria, is approved for the treatment of complicated skin and skin structure infections at a 4-mg/kg/day dose and for treatment of bacteremia and right-sided endocarditis caused by S. aureus at 6 mg/kg/day. Daptomycin is being used with increasing frequency as a primary agent for the treatment of S. aureus bacteremia, particularly to treat persistent bacteremia in which vancomycin MICs are 2 μg/ml. Indeed, two recent studies suggest that daptomycin may be more efficacious than vancomycin for the treatment of such infections (11, 12). In these two studies, daptomycin was found to be associated with decreased 30-day (12) or 60-day (11) mortality and fewer instances of persistent bacteremia (12). Similarly, daptomycin is commonly employed for the treatment of difficult VRE infections, such as bacteremia, based on in vitro activity and data from individual cases reports, despite the lack of clinical trial data that demonstrate efficacy (13).

This article provides a review of daptomycin, including an overview of the mechanism of action, mechanisms for bacterial nonsusceptibility to daptomycin, and clinical laboratory considerations for testing and reporting daptomycin susceptibility results.

DAPTOMYCIN MECHANISM OF ACTION AND SPECTRUM OF ACTIVITY

Daptomycin Interaction with the Gram-Positive Cell Membrane and Wall

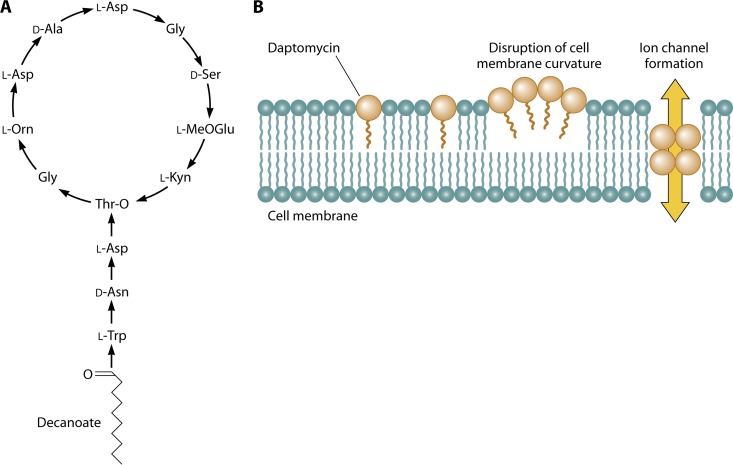

Daptomycin is a cyclic lipopeptide produced by Streptomyces roseosporus using nonribosomal peptide synthetases (14). Daptomycin consists of 13 amino acids: 10 C-terminal residues that form a ring closed by an ester bond and a 3-amino-acid exocyclic side chain with a terminal tryptophan linked to the fatty acyl residue, decanoic acid (15) (Fig. 1A). Several of the amino acid residues that make up daptomycin are nonstandard, including three d-amino acids, ornithine, 3-methyl-glutamic acid, and kynurinine.

Fig 1.

Daptomycin structure (A) and interaction with the cytoplasmic membrane (B).

The initial binding event between daptomycin and the target Gram-positive membrane has not yet been defined but may be via interaction with the bacterial membrane lipid, phosphatidylglycerol (PG). Evidence for this interaction is derived from experiments with perylene-daptomycin, a compound in which the decanoyl chain of daptomycin is replaced with perylene-butanoic acid, a substitution associated with a minimal increase in MIC for Bacillus subtilis (16). Perylene-daptomycin binds PG on liposomes (16), an interaction that drives oligomerization of perylene-daptomycin on both liposomes and the Gram-positive membrane (16, 17). The activity of daptomycin is strictly dependent on the presence of physiological levels of Ca2+, which induce conformational changes in daptomycin (18, 19). These changes also facilitate daptomycin oligomerization and membrane insertion (20, 21), possibly by increasing exposure of hydrophobic moieties in the molecule (19).

Daptomycin is an anionic molecule, and in addition to the effect on daptomycin's structure, calcium ions are believed to allow daptomycin to overcome the charge-charge repulsion between daptomycin and the anionic phospholipid heads of the bacterial membrane (20). Gram-negative cytoplasmic membranes contain a significantly lower proportion of anionic phospholipids than Gram-positive bacteria, due to a higher phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) content (22), although exceptions to this trend can be found. Notably, relative to that of other Gram-positive bacteria, the PE content of Bacillus cereus is high (22), and yet daptomycin retains activity against this organism (23). Regardless, an overall less anionic surface may be why daptomycin does not demonstrate detectable activity against Gram-negative bacteria, even when the outer membrane is compromised (24).

Insertion of the daptomycin oligomers into the Gram-positive membrane are thought to generate an ion conduction structure in a process akin to that of the pore-forming toxins, which oligomerize in target membranes to form ring-like pores (17). This theoretical ion-conducting channel would disrupt the functional integrity of the Gram-positive membrane, resulting in intracellular potassium ion release, membrane depolarization, and cell death with initial preservation of bacterial cell integrity, all of which are observed in daptomycin-treated cells (25–27). However, direct evidence of oligomer involvement in membrane permeabilization is still lacking. Furthermore, the absence of S. aureus cell lysis when treated with daptomycin (28) suggests that membrane pore formation, in the traditional sense, does not occur.

Pogliano and colleagues recently evaluated the membrane structure of B. subtilis in the presence of lethal and sublethal doses of daptomycin using time-lapse fluorescence microscopy (29) and the fluorescein BODIPY-labeled daptomycin, which retains antibacterial activity, albeit at a slightly reduced potency compared to that of the native molecule. These authors observed that daptomycin-BODIPY bound preferentially at regions of active peptidoglycan synthesis and membrane curvature, including the leading edges of nascent cell wall septa during binary fission or sporulation (29, 30). The authors postulated that membrane stress at these sites facilitated daptomycin insertion into the membrane. Focal membrane structure distortion was also observed at regions in the membrane that colocalized with daptomycin (29). Insertion of daptomycin oligomers into the membrane may thus yield localized alteration of the membrane curvature (29) via the relative “conical” structure of daptomycin compared to that of other lipids in the membrane (e.g., a large head group and short lipid tail) (Fig. 1B). Oligomerization of daptomycin in in vitro model membranes has similarly been shown to induce curved membrane patches (31).

The bacterial protein DivIVA colocalizes with these daptomycin-induced curved membrane patches (29). DivIVA is a protein conserved across Gram-positive bacteria that specifically targets sites of strong negative membrane curvature (32), where it serves to recruit proteins involved in cell division (33), chromosome segregation (34, 35), genetic competence (36), and secretion (37). In B. subtilis, DivIVA has specifically been shown to recruit the MinC/MinD proteins (38), inhibitors of FtsZ polymerization during cell division, and the competence-specific inhibitor of cell division Maf (36). DivIVA may thus incorrectly recognize the site of daptomycin-induced membrane curvature as a location of potential cell division and induce local activation of peptidoglycan biogenesis (29). The lack of corresponding changes around the cell wall may explain the observations of cell bending in rod-shaped cells such as B. subtilis and aberrant division septa in S. aureus in the presence of sublethal doses of daptomycin (28). Interestingly, in Streptomyces, DivIVA assembly determines the site of hyphal branch development. Pogliano and colleagues hypothesized that in the natural environment when expressed by Streptomyces roseosporus, daptomycin serves as a molecular signal by which this organism initiates hyphal branching (29); this very interesting hypothesis awaits further study. Exposure to daptomycin induces cell wall stress response in S. aureus and B. subtilis (30, 39), and the numbers of membrane distortions observed by Pogliano et al. were proportional to daptomycin concentration (29). Presumably, at concentrations above the MIC, the cell's ability to respond to these distortions is overwhelmed, resulting in leakage of ions and loss of membrane potential, without pore formation.

Daptomycin Pharmacokinetics

Daptomycin exerts its bactericidal activity in a concentration-dependent manner (maximum concentration [Cmax]/MIC), has a long half-life (8 h), and demonstrates a prolonged postantibiotic effect of up to 6.8 h (40). For these reasons, together with the fact that the adverse event of skeletal muscle injury can be predicted to occur at a daptomycin trough of > 22 mg/liter, once-daily dosing is used clinically, via either a 30-min intravenous infusion or a 2-min intravenous injection (41). While doses of 4 mg/kg and 6 mg/kg are approved by the U.S. FDA for the treatment of soft tissue infection and S. aureus bacteremia, respectively, abundant in vitro and animal data suggest that higher doses may improve activity and reduce resistance development (a particular concern when daptomycin is used in vancomycin salvage therapy). Thus, the expert authors of the IDSA MRSA treatment guidelines recommend 10-mg/kg dosing when daptomycin is used in this setting (42). The safety and tolerability of daptomycin and linear dose-proportional pharmacokinetics through the 6- to 12-mg/kg/day dosing range have been demonstrated in healthy volunteers (43).

Since daptomycin is excreted through the kidneys, the dosing interval is increased to every 48 h (q48h) in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance of <30 ml/min). For patients on hemodialysis, 6-mg/kg posthemodialysis dosing 3 times per week provides adequate drug exposure, even after the 68-h interdialytic period. However, insufficient concentrations will result if the dose is administered during rather than after the dialysis treatment (44). In patients in intensive care, those undergoing extended dialysis should receive 6 mg/kg once daily to prevent suboptimal drug exposure, whereas those on continuous venovenous hemodialysis should receive 8 mg/kg every 48 h (45, 46).

Daptomycin is highly bound to serum proteins (90%) and is distributed primarily in the extracellular fluid with penetration to vascular tissues (47). Daptomycin does not cross the blood-brain barrier, nor does it penetrate the cerebrospinal fluid of normal individuals. However, 11.5% penetration relative to that in serum is observed in patients with suspected or confirmed neurological infections (48). Daptomycin data for pediatric patients are limited, as the safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics in children have not been established, although preliminary data suggest that much higher doses than those that are FDA approved are needed to achieve serum concentrations comparable to those in adult patients (49).

Daptomycin in Pneumonia Models

An important aspect of daptomycin activity is its inhibition by pulmonary surfactant, a complex lipid-protein mixture that serves to reduce surface tension in lung alveoli. Daptomycin activity against both S. aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae is inhibited by bovine-derived surfactant in vitro such that daptomycin MICs for these organisms, measured by broth microdilution (BMD), increase by greater than 100-fold by the addition of 10% surfactant to test medium and by 16 to 32-fold in the presence of 1% surfactant (50). In these experiments, daptomycin appears to insert irreversibly into lipid aggregates of bovine surfactant in a calcium-dependent manner, rendering daptomycin inactive (50). In vivo, both S. pneumoniae and S. aureus have been shown to persist in the lung following daptomycin treatment in murine models of bronchio-alveolar pneumonia, even at elevated daptomycin doses (50). In contrast, ceftriaxone reduces the bacterial burden in this setting by greater than 5 orders of magnitude (50). In phase 3 clinical trials, daptomycin dosed at 4 mg/kg failed to achieve statistical noninferiority to ceftriaxone for the treatment of hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia (51).

Daptomycin efficacy has been demonstrated in models of hematogenous pneumonia induced by S. aureus (50, 52) and pulmonary anthrax infections (53). The pathophysiology of these infections, both of which induce significant destruction of tissue integrity and consequent bacteremia, differs significantly from that of bronchio-alveolar pneumonia, which is largely confined to the intra-alveolar space (50). Thus, daptomycin efficacy in pulmonary anthrax and hematogenous pneumonia is likely due to (i) effective killing of organisms that exit the alveolar space into the lung tissue and blood, (ii) significant dilution of surfactant by large amounts of blood and other extra-alveolar contents that enter the alveolar space upon disruption of its integrity, and (iii) dispersion of surfactant outside its usual intra-alveolar space. The first suggestion is supported by the observed differences in daptomycin efficacy in a murine model of pneumonia induced by strains of pneumococcus with differing virulence (54). Daptomycin was found to be as effective as ceftriaxone at preventing pneumococcal sepsis and death induced by the highly virulent serotype 2 S. pneumoniae strain, despite S. pneumoniae persistence in the lung parenchyma of daptomycin-treated mice (54). In contrast, daptomycin was not effective for the treatment of pneumococcal pneumonia induced by a serotype 19 strain with low-level virulence (54). Mice treated with daptomycin in this setting had a survival rate of 40%, compared to 100% survival in ceftriaxone-treated mice. Post hoc analysis from a clinical trial of patients treated for right-sided endocarditis revealed that the overall daptomycin success for the treatment of patients with septic pulmonary emboli caused by MRSA was 75% (3/4), compared to 60% (3/5) among vancomycin-treated patients (P > 0.05) (55). Nevertheless, the empirical use of daptomycin in patients with S. aureus infections who have pulmonary infiltrates is severely limited in clinical practice settings given that differentiating hematogenous versus bronchio-alveolar pneumonia may be extremely difficult.

Daptomycin Activity against Gram-Positive Bacteria

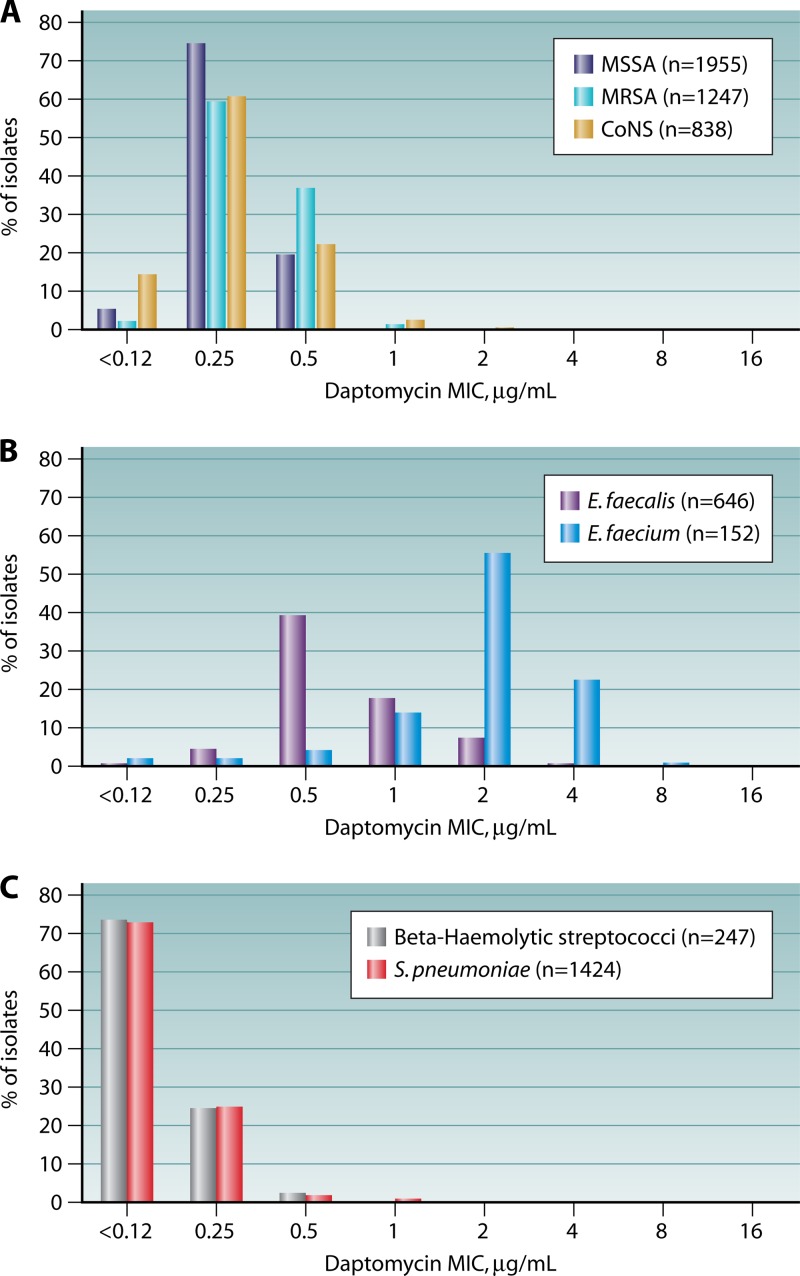

A study of Gram-positive clinical isolates collected in 2002, prior to the approval of daptomycin for clinical use, from over 70 medical centers located in Europe, North America, and South America demonstrated that 99.4% of isolates were inhibited by ≤2 μg/ml daptomycin (56) (Fig. 2). Daptomycin's spectrum of activity encompasses both MSSA and MRSA, vancomycin-susceptible and -resistant Enterococcus, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, S. pneumoniae (including penicillin-resistant strains), and other streptococci (S. pyogenes, S. agalactiae, and S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis). An S. aureus MIC “creep” (57), such as observed by some for vancomycin, has not been observed for daptomycin in the 10 years since its approval for clinical use (7). Indeed, daptomycin MIC distributions have not changed appreciably for any of the Gram-positive pathogens for which it is approved (58, 59). The MIC90 for daptomycin remains 0.5 μg/ml among staphylococci (Fig. 2A) (60). In contrast, daptomycin MICs for wild-type strains of enterococci are typically 1 to 2 2-fold dilutions higher than those for the staphylococci. The Enterococcus faecium MIC90 is higher than that of E. faecalis (4 μg/ml versus 1 μg/ml) (Fig. 2B). Streptococcus spp. are exquisitely susceptible to daptomycin, with MIC90 of 0.5 μg/ml (Fig. 2C).

Fig 2.

MIC distributions for Gram-positive clinical isolates collected in Europe, North America, and South America in 2002, before the introduction of daptomycin for clinical use. (Based on data from reference 56.)

Some species of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus display decreased susceptibility to daptomycin. In particular, Staphylococcus auricularis, Staphylococcus warneri, and Staphylococcus capitis display elevated MIC90s compared to those for other staphylococci, at 1 μg/ml (61). Greater than 95% of these coagulase-negative staphylococcal species remain susceptible to daptomycin. In contrast, only 71.7% daptomycin susceptibility was observed among 46 Staphylococcus sciuri isolates; this species has an MIC90 of 2 μg/ml to daptomycin (61). Eighty-five percent of these S. sciuri isolates investigated were susceptible to vancomycin (61).

Daptomycin also has in vitro activity against Corynebacterium spp. (62, 63), Leuconostoc (64), Pediococcus (64), and a variety of Gram-positive anaerobes, including the clostridia (62–64). In vitro MICs to Listeria monocytogenes are elevated compared to those to other Gram-positive bacteria, with an MIC90 of 4 μg/ml (64, 65). The L. monocytogenes cell membrane is rich in branched fatty acids (66, 67), which may prohibit optimal insertion and oligomerization of daptomycin in the cell membrane, but this has not been specifically demonstrated. Daptomycin does not display in vitro activity against the rapidly growing mycobacteria (68) or Rhodococcus or Nocardia species (64).

DAPTOMYCIN BREAKPOINTS

Both CLSI and the FDA have established daptomycin breakpoints for S. aureus and the beta-hemolytic streptococci. Whereas CLSI provides a daptomycin breakpoint for all enterococci, the FDA provides a breakpoint only for vancomycin-susceptible isolates of E. faecalis. CLSI additionally provides daptomycin breakpoints for coagulase-negative staphylococci, the viridans group streptococci, Corynebacterium, and Lactobacillus (Table 1). As is common for newer antimicrobial agents, for which few microbiological or clinical data exist by which to define a clear distinction between susceptible and resistant isolates, susceptible-only breakpoints were established for daptomycin by these two organizations for all the aforementioned organisms. Only 2 nonsusceptible (NS) isolates were observed in daptomycin phase 2 and 3 clinical trials conducted prior to the establishment of FDA and CLSI breakpoints, among more than 1,000 patient isolates studied (69). A daptomycin-NS S. aureus strain (MIC, 4.0 μg/ml) emerged in a patient treated with suboptimal daptomycin therapy for the first 5 days of treatment (e.g., <1.6 mg/kg q12h), and a daptomycin-NS E. faecalis (MIC, 32 μg/ml) was isolated from a patient with a chronic decubitus ulcer and 44 days of 4-mg/kg daily daptomycin treatment (69). Isolates that test with MICs above the susceptible breakpoint are referred to as nonsusceptible (NS). The NS designation does not necessarily indicate that an organism harbors a resistance mechanism but rather that the isolate falls outside the wild-type distribution of MICs (70) and/or may not be susceptible based on pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters.

Table 1.

Daptomycin MIC breakpoints established by the CLSI, FDA, and EUCAST

| Organism | MIC breakpoint (μg/ml) established bya: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLSI |

FDA |

EUCAST |

||||

| S | R | S | R | S | R | |

| Staphylococcus | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1 | >1 | ||

| Enterococcus | ≤4 | ≤4b | ||||

| Beta-hemolytic Streptococcus | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1 | >1 | ||

| Viridans group Streptococcus, excluding S. pneumoniae | ≤1 | |||||

| Corynebacterium | ≤1 | |||||

| Lactobacillus | ≤4 | |||||

S, susceptible; R, resistant; CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; EUCAST, European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing.

Due to the lack of clinical data, the FDA clinical breakpoint is approved for vancomycin-susceptible E. faecalis alone.

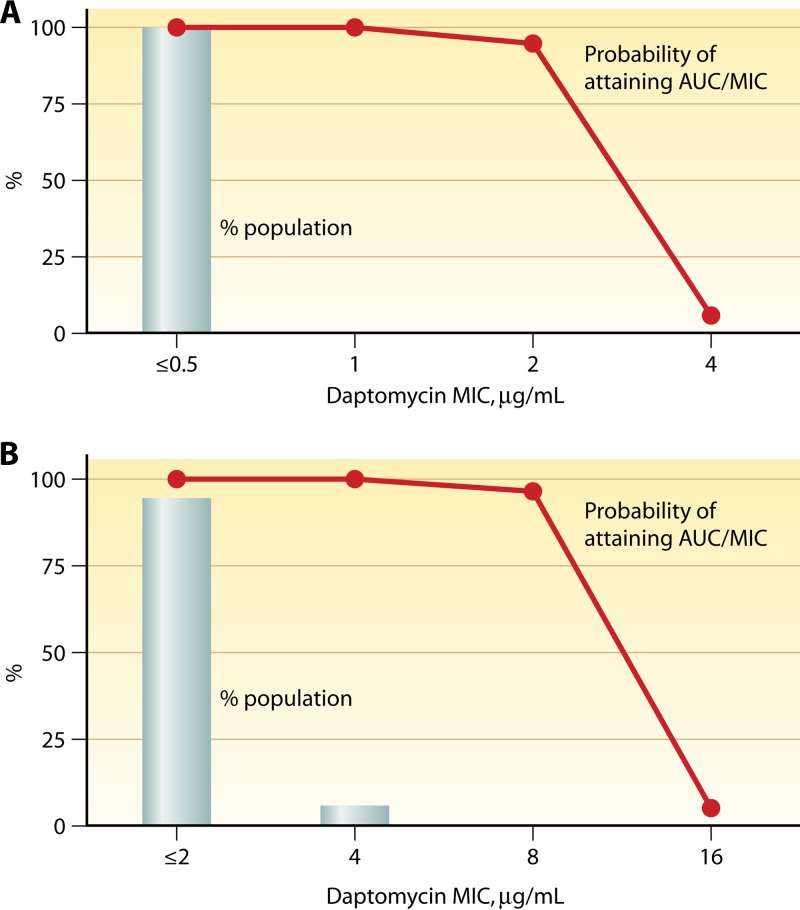

In addition to clinical trial data, Monte Carlo simulations were used to establish the daptomycin susceptible-only breakpoints. In these models, human pharmacokinetic data (AUC) were applied as a variable against pharmacodynamic exposure criteria (AUC/MIC) for efficacy (40) using single MIC values to test breakpoint hypotheses (71). AUC/MIC targets of 180, 160, and 48 for S. aureus, Streptococcus, and Enterococcus were established using neutropenic murine thigh (S. aureus, Streptococcus, and Enterococcus) and renal (Enterococcus) infection model data. For these experiments, the equivalent of a 4-mg/kg q24h daptomycin dose was used, which at the time was the only FDA-approved dose for daptomycin. A 95% probability of achieving these targets was found for Staphylococcus and beta-hemolytic streptococci if the daptomycin MIC was ≤2 μg/ml, compared to a 6% probability of target attainment if the daptomycin MIC was 4 μg/ml (Fig. 3A) (71). For E. faecium and E. faecalis, a 96.2% probability of target attainment was calculated if the daptomycin MIC was ≤8 μg/ml, whereas <5% target attainment was predicted if an MIC of ≥16 μg/ml was used (Fig. 3B) (71). Higher daptomycin dosing, such as the 6-mg/kg dose approved for S. aureus bloodstream infections or even higher doses as suggested by some for enterococcal infections (72), may allow treatment of isolates with elevated MICs, although this has not been well defined.

Fig 3.

Percent probability of pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic target attainment for area under the curve targets of 180 for S. aureus (A) and 48 for E. faecalis (B). Data were generated from Monte Carlo analysis by applying a total drug AUC/MIC criterion of 180 or 48 for efficacy, based on murine thigh and thigh and renal models for S. aureus and E. faecalis, respectively. A 4-mg/kg q24h dose of daptomycin with an AUC of 494 ± 75 μg · h/ml was used in this simulation.

In contrast to the American organizations, the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) has set both susceptible (≤1 μg/ml) and resistant (>1 μg/ml) breakpoints for Staphylococcus and beta-hemolytic streptococci. EUCAST has not established breakpoints for Enterococcus, with the rationale that enterococci infrequently cause skin and soft tissue infections and therefore insufficient clinical evidence existed for a breakpoint. EUCAST has, however, published on their website an epidemiological cutoff (ECOFF) value for E. faecium and E. faecalis of ≤4 μg/ml (http://mic.eucast.org/Eucast2/). The ECOFF is established through evaluation of the wild-type MIC distribution of a large collection of isolates and may serve, similar to the NS designation provided by CLSI and FDA, to indicate that an isolate has an MIC that is elevated compared to those for other isolates of the same genera and species.

Since the daptomycin susceptible-only breakpoints were established by FDA and CLSI in 2003 and 2004, respectively, few prospective data have emerged to validate these breakpoints. Tables 2 and 3 present pooled data from all available studies and case reports to present cure rates stratified by daptomycin MIC for MRSA and VRE infection, respectively. Numerous caveats exist in regard to these data. The patient populations investigated were heterogeneous and difficult to compare, both within and across studies. Further, there are many important determinants of clinical outcome beyond MIC, such as pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic factors, dosing, patient comorbidities, administration of other antibiotics, nonmedical management, severity and site of infection, including the presence of deep-seated foci, and prosthetic or foreign material (73–75). Nearly all treatment failures described for daptomycin in these studies occurred when patients did not undergo appropriate surgical intervention or removal of foreign material, where necessary. In such cases, it is possible that an MIC is driven by, and not causing, secondary clinical failure. More detail on the studies from which the pooled data were derived are available in Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material.

Table 2.

Daptomycin cure rate of MRSA infections by daptomycin MICa

| Daptomycin MIC, μg/mlb | Cure, nc | Total, nd | Cure rate, % (95% CI)e | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤1 | 376 | 434 | 86.6 (83.4–89.8) | 11, 12, 73, 202–217 |

| 2 | 15 | 31 | 48.4 (30.8–66.0) | 12, 98, 202, 216–222 |

| 4 | 3 | 14 | 21.4 (0.0–42.9) | 12, 216, 217,223, 224 |

| ≥8 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 76, 77 |

MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

MIC by broth microdilution, Etest, or automated method. The isolate with the highest MIC was included. Etest results were rounded up to the nearest dilutional integer for comparison.

Microbiological or clinical cure. Where both were presented in a relevant study, the lower cure rate was chosen for a more conservative estimate.

Data pooled from multiple studies and case reports, with additional data clarification by the study authors where possible. See Table S1 in the supplemental material for further details.

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table 3.

Daptomycin cure rate of VRE infections by daptomycin MICa

| Daptomycin MIC, μg/mlb | Cure, nc | Total, nd | Cure rate, % (95% CI)e | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤1 | 6 | 7 | 85.7 (60.6–100) | 79, 225–227 |

| 2 | 12 | 19 | 63.2 (37.5–88.9) | 79, 225, 228–231 |

| 4 | 33 | 44 | 75.0 (52.3–97.7) | 79, 225, 230–233 |

| ≥8 | 0 | 5 | 0.0 | 75, 160, 183, 234, 235 |

VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus, including E. faecalis, E. faecium, E. raffinosus, and E. gallinarum.

MIC by broth microdilution, Etest, or automated method. The isolate with the highest MIC was included. Etest results were rounded up to nearest dilutional integer for comparison.

Microbiological or clinical cure. Where both were presented in a relevant study, the lower cure rate was chosen for a more conservative estimate.

Data pooled from multiple studies and case reports, with additional data clarification by study authors where possible. See Table S2 in the supplemental material for further details.

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

In spite of these factors, a crude relationship between MIC and clinical outcomes of published MRSA infections presented in Table 2 may be deduced. At an MIC of ≤1 μg/ml, cure rates of 86.6% (376/434) were observed across the studies evaluated, whereas cure was observed in less than half of cases (15/31) with an MIC of 2 μg/ml and in less than a quarter of cases (3/14) with an MIC of 4 μg/ml (Table 2). No successful outcomes were seen in the two cases where an MIC of ≥8 μg/ml to daptomycin was documented (76, 77). A lower cure rate was observed across studies for the treatment of daptomycin-susceptible VRE (e.g., with an MIC of ≤4 μg/ml), with 72.8% (51/70) of cases resulting in cure. Similar to the case for MRSA, none of the 5 cases documented with a daptomycin MIC of ≥8 μg/ml were associated with cure (Table 3). The data for VRE include both E. faecium and E. faecalis, as the CLSI interpretive criteria for VRE do not differentiate between these species. However, significant differences in daptomycin response exist between these two organisms, as can be seen between the wild-type daptomycin MIC distributions (Fig. 2). Further investigation is needed to elucidate whether a separate daptomycin breakpoint might be considered for these two organisms. In particular, concern has emerged regarding the appropriateness of the CLSI daptomycin breakpoint for E. faecium, even with a 6-mg/kg/day dose (78). Clinical experience with daptomycin for the treatment of enterococcal infections, and in particular E. faecium, is limited to retrospective, observation studies of patients with bacteremia. Success rates in case series vary from 57% to 78.2% (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Mutations associated with daptomycin nonsusceptibility (such as liaFSR) in daptomycin-susceptible enterococci (78) and inferior daptomycin treatment outcomes in E. faecium bacteremia caused by isolates with daptomycin MICs of >2 μg/ml (79) both suggest the daptomycin susceptible breakpoint should be reevaluated and possibly lowered from ≤4 μg/ml to ≤2 μg/ml. To further support this notion, Munita and colleagues demonstrated that an E. faecalis isolate with a daptomycin-susceptible MIC of 4 μg/ml but a mutated liaF allele introduced via allelic exchange was daptomycin tolerant in vitro (80). In these experiments, no daptomycin bactericidal activity was found for this mutated isolate at 40 μg/ml and 80 μg/ml daptomycin (5 and 10 times the MIC, respectively, when measured in brain heart infusion [BHI]). In contrast, the wild-type E. faecalis isolate demonstrated a >3-log decrease in CFU/ml when tested in daptomycin held at 10 μg/ml and 20 μg/ml (80).

Many feel that in order to overcome the decreased potency of daptomycin against enterococci, higher doses of daptomycin may be required, in particular in the setting of infective endocarditis. However, a retrospective study of VRE bacteremia did not find a difference in time to microbiological cure in patients treated with ≤6 mg/kg versus >6 mg/kg daptomycin daily (72). Interestingly, the investigators who noted a reduced clinical efficacy for daptomycin at MICs of 3 to 4 μg/ml (measured by Etest) in VRE bacteremia also showed that clinical efficacy can be “restored” with concomitant β-lactam therapy (79). As such, combination therapy with β-lactams may reestablish clinical efficacy seen with daptomycin in cases of VRE bacteremia where the daptomycin MIC is 4 μg/ml (81). However, it is to be cautioned that the data on the use of concomitant β-lactam therapy for the treatment of enterococcal infections have been presented only in abstract format, and further peer-reviewed studies are required to substantiate these findings.

DAPTOMYCIN NONSUSCEPTIBILITY

Daptomycin hydrolysis has been described among nonpathogenic environmental isolates. The actinomycetes inactivate daptomycin by hydrolytic ring opening or deacylation of daptomycin's lipid tail (82). Recently, daptomycin nonsusceptibility was identified in Paenibacillus laulus isolates recovered from a New Mexico cave that had been isolated from human, animal, and water contact for over 4 million years (83). These isolates expressed an EDTA-sensitive esterase that opened the daptomycin ring by cleaving the bond between daptomycin's threonine and kynurenine residues (83). Such nonsusceptibility predates human use of antibiotics and is thought to be the result of competitive microbial interactions in this environment. However, these environmental organisms may serve as a reservoir for daptomycin nonsusceptibility with the potential of mobilization into clinical isolates; indeed, the vanA and vanB genes, which confer vancomycin resistance to the enterococci, are found in environmental Paenibacillus and Rhodococcus spp. (84). Such transmissible resistance has not been documented for daptomycin to date. Rather, the overarching mechanism for daptomycin nonsusceptibility among clinical isolates investigated to date appears to be complex adaptations in cell wall homeostasis and membrane phospholipid metabolism.

Daptomycin Nonsusceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus

A number of case reports have documented the emergence of daptomycin-NS S. aureus isolates during unsuccessful therapy with this agent (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) (76, 85–90). In most instances, NS isolates emerged in the setting of recalcitrant, deep-seated infections and those associated with a high burden of the infecting organism, such as endocarditis, catheter-related bacteremia, or an undrained abscess (Table 2) (91). Frequently, NS isolates are observed when attempts were made to treat with antimicrobial therapy alone rather than by prompt source removal of the foci of infection (e.g., a foreign body or abscess). In a large, multinational randomized clinical trial of S. aureus bacteremia and endocarditis, among 120 patients who received daptomycin therapy, 6 experienced microbiological failure that coincided with the emergence of daptomycin-NS isolates (74); in this study, treatment failure was most frequently associated with deep-seated infection that did not receive surgical intervention (74). Sharma and colleagues reported NS daptomycin MICs for 6 of 10 patients at a single center with persistent bacteremia, ranging from 1 to 21 days, who were treated with daptomycin as vancomycin salvage therapy (85). In this study, an intravenous catheter was the most common source of bacteremia, and the initial daptomycin dose was suboptimal, at 4 mg/kg, for 40% of the patients (85). We have also noted a stepwise increase in daptomycin MIC in a patient who was bacteremic over multiple days (92). These data illustrate the need for frequent monitoring of daptomycin susceptibility in patients who remain bacteremic while on treatment. It is our opinion that laboratories should consider performing susceptibility testing on each repeat isolate of MRSA for patients who are persistently bacteremic. Indeed, the daptomycin FDA package insert recommends testing for daptomycin susceptibility when S. aureus is isolated from the blood of a patient with persistent bacteremia (41).

Mechanisms of nonsusceptibility in S. aureus.

S. aureus nonsusceptibility to daptomycin is multifactorial, the pathway of which appears to be isolate specific, involving alterations to both the cell membrane and the cell wall via adaptations in metabolic function and stress response regulatory pathways (93). Recently, whole-genome sequencing was performed on a collection of clinical daptomycin-susceptible S. aureus strains and their isogenic daptomycin-NS daughter strains, isolated from nine patients who had failed daptomycin therapy (94). This study also evaluated three laboratory strains in which daptomycin nonsusceptibility was induced through serial passage in sublethal concentrations of daptomycin (94). This group found that the laboratory-derived, daptomycin-NS isolates harbored fewer genomic mutations (average of 2) than the clinically derived, daptomycin-NS isolates (average of 6) (94). Whether laboratory or clinically derived, all daptomycin-NS isolates in this study had at least one mutation in one of three genes coding for phospholipid synthesis: mprF, cls2, or pgsA (94). All clinically derived isolates harbored a mutation in mprF (encoding the multiple peptide resistance factor), whereas only one laboratory-derived daptomycin-NS isolate harbored a mutation in mprF (94). Appreciation of this dichotomy between clinically derived in vivo daptomycin nonsusceptibility and ex vivo daptomycin nonsusceptibility cannot be overemphasized. The in vivo environment, even in the absence of administered antibiotics, may provide a selective pressure milieu that influences resistance to antistaphylococcal antibiotics such as vancomycin and daptomycin.

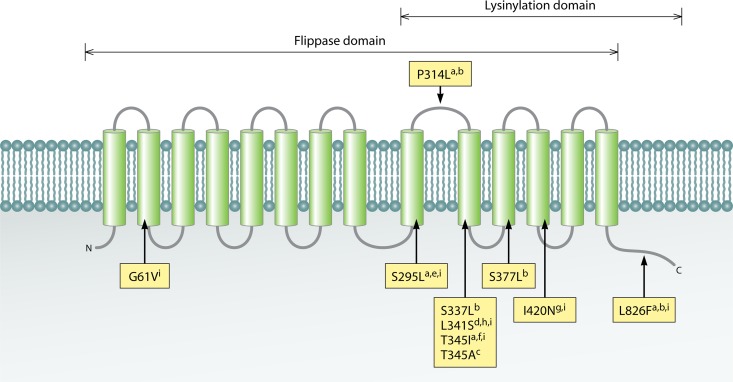

Mutations in mprF, typically in the form of single-nucleotide polymorphisms, have been identified in most daptomycin-NS S. aureus strains investigated to date (88–90, 95–98). In one study of a laboratory-derived daptomycin-NS S. aureus strain, mutation to mprF was shown, by array-based DNA hybridization and comparison, to consistently be the first genetic adaptation accompanying a daptomycin MIC of >1 μg/ml (96). mprF encodes a bifunctional membrane protein that catalyzes the lysinylation of PG to form the positively charged membrane phospholipid lysyl-phosphatidylglycerol (L-PG) in the inner leaflet of the membrane. MprF subsequently translocates (flips) L-PG to the outer leaflet of the membrane via the flippase domain (99). Together, these activities result in a partial neutralization of the normally anionic bacterial cell surface (99). MprF is composed of 10 N-terminal hydrophobic transmembrane domains and a hydrophilic C-terminal domain (Fig. 4). Ernst and colleagues demonstrated that the N-terminal domain of MprF from S. aureus is involved in flippase activity, whereas the C-terminal domain provides lysinylation activity, when expressed in Escherichia coli (100). Deletion of mprF in S. aureus yields increased susceptibility to both daptomycin and the host defense peptides (HDPs) (100, 101), which also are microbicidal cationic peptides and are discussed further below. Inactivation of mprF expression through the use of mprF-specific antisense RNA has been shown to reestablish daptomycin susceptibility to daptomycin-NS isolates (102). Logically, the mprF polymorphisms described to date that are associated with daptomycin-NS phenotypes are gain-in-function mutations (89, 94), via either increased expression (93, 103) or activity (93, 98, 101) of MprF. Mutation to both domains of mprF has been documented, at a variety of loci (Fig. 4). Dependent on the domain of mprF mutated, L-PG flippase or synthase, the result is either increased flipping of L-PG to the outer leaflet of the membrane or excess L-PG production in the inner leaflet, respectively (89, 100, 104, 105). Increased pools of L-PG in the inner leaflet may indirectly enhance translocation of L-PG to the outer leaflet, in a gradient-dependent manner (94), thereby rendering the surface of the bacterium less anionic than that of the isogenic daptomycin-susceptible strain.

Fig 4.

Mutations in MprF identified in daptomycin-NS S. aureus. MprF consists of an N-terminal flippase domain and a C-terminal phosphatidylglycerol lysylination domain. Mutations have been identified in both domains, as outlined in the following references: a, reference 96; b, reference 101; c, reference 88; d, reference 98; e, reference 103; f, reference 115; g, reference 90; h, reference 201; i, reference 94.

However, the association between daptomycin-NS S. aureus and mprF mutation is likely not strictly based on charge repulsion. Cell surface charge among daptomycin-NS isolates with mprF mutations is not always significantly different from that of the daptomycin-susceptible parent strain (101, 106). Further, in model membrane systems, initial cationic peptide interactions with the membrane are not linearly correlated to L-PG content and are unaffected until a very high concentration of L-PG is incorporated into the membrane (107). As an alternative hypothesis, increased MprF lysinylation of PG may serve to deplete the membrane of PG, although this has not been explicitly demonstrated (89, 107). Decreased PG membrane content is significant in the context of daptomycin nonsusceptibility, as data generated from B. subtilis indicate that PG participates in the initial docking and oligomerization of daptomycin within the membrane (16, 108). To support this hypothesis, mutation to a second gene involved in the synthesis of PG, pgsA, was recently identified as associated with the conversion from a daptomycin-susceptible to a daptomycin-NS phenotype in laboratory-derived daptomycin-NS isolates (94). Low PG membrane content has also been reported for daptomycin-NS B. subtilis (108) and for Enterococcus, which is further discussed below.

Returning to the charge repulsion hypothesis for daptomycin nonsusceptibility in S. aureus, mutations in genes in the dlt operon and cls2 were recently proposed to increase the net positive surface charge in daptomycin-NS S. aureus (109, 110). dlt encodes a protein involved in cell wall teichoic acid alanylation, and mutation to this gene was observed in a daptomycin-NS isolate with an increased net positive surface charge specifically associated with overexpression of this operon (109). cls encodes cardiolipin synthetase, a membrane-bound enzyme that, like MprF, modifies PG, in this case condensing two PG molecules to yield cardiolipin and glycerol (111). S. aureus harbors two cls genes (110), cls1 and cls2; cls2 is thought to have the predominant role of cardiolipin synthesis, whereas cls1 supplements cardiolipin synthesis under conditions that induce membrane stress, such as high salinity or low pH (110, 112). In two laboratory-derived NS isolates, mutation to cls2 was the only polymorphism identified across the genome compared to the daptomycin-susceptible parent isolates (94). cls expression was also shown to be repressed in a third daptomycin-NS laboratory-derived isolate (113). While the exact role of repressed cardiolipin synthesis in daptomycin-NS isolates remains to be elucidated, reduced cardiolipin content in the membrane may similarly yield an overall less anionic surface charge to S. aureus.

Susceptibility to both daptomycin and the HDPs has also been associated with relative cell membrane fluidity (89, 114). While the exact mechanism for this is unclear, alternations in membrane fluidity presumably modify the ability of such molecules to bind to, and/or oligomerize within, the membrane. Membrane fluidity is modulated via numerous mechanisms, including alteration to the fatty acid content of the membrane or increased expression of carotenoid (staphyloxantin), which serves as a membrane scaffold in S. aureus (105, 115). The synthetic pathway of staphyloxanthin in S. aureus is homologous to that of cholesterol biosynthesis in mammalian cells (with production similarly inhibited by statins); further, it also serves a similar function in membrane fluidity as does cholesterol in mammalian cells (116). Interestingly, whereas in vivo-derived daptomycin-NS isolates have been shown to have a hyperfluid membrane (89, 114), in vitro-derived isolates appear to have a more rigid membrane (97). These seemingly conflicting observations have been referred to as the “Goldilocks effect,” whereby both too much and too little membrane order are prohibitive to optimal daptomycin binding (117). Further, it would appear that not all S. aureus strains respond to daptomycin exposure by adapting membrane fluidity (115).

Many, but not all, daptomycin-NS S. aureus strains exhibit a thickened cell wall phenotype. Such thickened cell walls are observed in vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) (97, 104, 113, 118) and correlate directly with HDP resistance (114). Thus, it is difficult to determine which resistance phenotype drives the adaptive cell wall thickness response, and indeed resistance to these three agents may emerge in parallel. Regardless, daptomycin-NS vancomycin-susceptible S. aureus (VSSA) strains have been shown to display a thickened cell wall compared to parental, daptomycin-susceptible isolates (94, 104, 119). A thickened cell wall may act as a physical barrier to daptomycin's cell membrane target (97, 118). Numerous key genes in cell wall synthesis are activated following in vitro exposure of S. aureus cells to both daptomycin and vancomycin (39), including some involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis (murAB, lrgA, lrgB, tcaA, pbp2, and lytM) (39). Further, these genes and others involved in cell wall metabolism, i.e., the mecA, pbp2, sgtB, cap and tag genes, and also sgtA, yycI, yycJ, lytN, and lytH were found to be upregulated in daptomycin-NS versus daptomycin-susceptible S. aureus (93, 101). Polymorphism in genes associated with cell wall turnover, including yycG (walK), agr, and slp1, have been found in daptomycin-NS isolates (94). Many of the genes are part of the cell wall stimulon and under the control of the two-component regulator vraSR (120, 121). vraSR is similarly upregulated in daptomycin-NS and -susceptible S. aureus (93, 101, 113). Inactivation of vraSR in a daptomycin-NS strain yielded reversion to a susceptible daptomycin MIC, along with a thinner cell wall (101). In contrast, upregulation of vraSR is associated with in vitro development of daptomycin nonsusceptibility in S. aureus (113). Irrespective of the mechanism, clinical daptomycin-NS VISA isolates have peptidoglycan profiles which are characterized by increased cross-linking and decreased O acetylation of muramic acid, compared to those in the daptomycin-susceptible parental isolates (90). In contrast, these features were not found in a daptomycin-NS VSSA isolate with a thickened cell wall; in this case, the daptomycin-NS phenotype correlated with enhanced capacity to synthesize and d-alanylate cell wall teichoic acid (119). The tag gene ensemble, which is responsible for teichoic acid production, was upregulated in this NS isolate (93). As discussed above, expression profiling of the dlt gene cluster, which is responsible for d-analylation of cell wall teichoic acid, is also upregulated in daptomycin-NS isolates (109). Together, these data may suggest differing mechanisms of cell wall thickening between VISA and VSSA strains that are daptomycin NS.

Tying these many pathways to daptomycin nonsusceptibility together is the observation that many studies have identified mutations to the yycFG operon in daptomycin-NS isolates (93, 94, 96, 114). YycFG (also known as WalK/WalR because of its essential role in cell wall homeostasis [122]) is an essential two-component regulatory system, composed of the YycG histidine kinase and the YycF cognate response regulator. YycG colocalizes with the cell wall biosynthesis complex at nascent septa during S. aureus division (123, 124), which, as described above, is also a target site for daptomycin insertion into the membrane (29, 30). Here, it is thought that YycG alters its kinase activity in response to local membrane changes, perhaps via sensing alteration of membrane fluidity (125). In S. aureus, YycFG primarily regulates expression of genes involved in cell wall metabolism (122, 126). These include many genes associated with daptomycin nonsusceptibility, including mprF, phoP (which in turn regulates expression of the tagA operon), alt, lytM, and ftsZ (93). Recently, Howden and colleagues investigated VISA phenotypes by whole-genome sequencing of VISA and VSSA strain pairs (127). Mutations in yycFG in these VISA isolates were found to be responsible for an increase in the daptomycin MIC (127). However, these authors found that the costs of such mutations to yycFG were reduced virulence and biofilm formation (127).

Susceptibility relationship between daptomycin, vancomycin, and HDPs in S. aureus.

Daptomycin nonsusceptibility appears to be linked in some S. aureus isolates to increased vancomycin MICs. Vancomycin is a molecule which, like daptomycin in the presence of calcium, is cationic and targets the cell wall. Among susceptible isolates, daptomycin and vancomycin MICs trend together, in that elevated daptomycin MICs (e.g., 1.0 μg/ml) are observed in S. aureus strains with similarly elevated vancomycin MICs (118, 128–131). A daptomycin-NS phenotype is observed in 38 to 83% of vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) isolates and in up to 15% of S. aureus isolates with vancomycin heteroresistance (hVISA) (90, 118, 132, 133) (Table 4). It is important to note that vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) isolates retain 100% susceptibility to daptomycin (129, 134), because vancomycin resistance in these isolates is mediated by vanA, which does not affect daptomycin susceptibility (129). The highest incidence (62%) of daptomycin susceptibility among VISA strains was documented in an Australian study of isolates recovered from patients prior to the release of daptomycin for clinical use in that country (133). This finding demonstrates that daptomycin nonsusceptibility can emerge in the absence of daptomycin selective pressure. However, there are a substantial number of daptomycin-NS isolates described to date that remain vancomycin susceptible, reinforcing the fact that susceptibility to these two drugs is not linked in all isolates (92, 101).

Table 4.

Daptomycin susceptibilities of S. aureus strains with various vancomycin susceptibility phenotypes

| S. aureus phenotypea | No. of isolates tested | % Daptomycin susceptibility | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| hVISA | 27 | 85 | 133 |

| 88 | 100 | 60 | |

| VISA | 70 | 17b | 129 |

| 33 | 30 | 134 | |

| 17 | 53 | 60 | |

| 13 | 62 | 133 | |

| VRSA | 13 | 100 | 129, 134 |

hVISA, vancomycin-heteroresistant S. aureus; VISA, vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus; VRSA, vancomycin-resistant S. aureus.

Includes isolates with vancomycin MICs of 16 μg/ml.

Given the relationship between daptomycin and vancomycin susceptibility in some S. aureus isolates, the thought that vancomycin exposure might prime S. aureus to develop a daptomycin-NS phenotype during daptomycin therapy is of concern. Indeed, mutations associated with daptomycin nonsusceptibility have been observed during vancomycin therapy (127). Whether such mutations preprogram S. aureus for subsequent daptomycin nonsusceptibility is unclear. In an in vitro model of endocarditis, Rose and colleagues investigated the effect of exposing a daptomycin-susceptible parental S. aureus strain to vancomycin. This isolate was recovered from a patient in whom a daptomycin-NS S. aureus strain emerged following suboptimal daptomycin dosing for endocarditis (135). Neither 8 days of exposure to daptomycin nor 4 days of vancomycin followed by 4 days of daptomycin resulted in a daptomycin-NS phenotype (135), suggesting that vancomycin exposure does not “prime” for daptomycin NS, even in an isolate that might be predisposed to develop daptomycin nonsusceptibility. In vivo, however, elevated (but susceptible) daptomycin and vancomycin MICs were observed in S. aureus isolated from the blood of patients treated with one or more vancomycin doses in the prior 30 days, compared to patients not exposed to vancomycin (128). This trend achieved statistical significance only for vancomycin. Daptomycin, but not vancomycin, remained bactericidal in the S. aureus isolated from these patients (128). Similarly, a history of vancomycin use did not affect the clinical outcome of daptomycin therapy in patients with MRSA bacteremia and endocarditis (74), and in a retrospective case-control study, no daptomycin-NS isolates were recovered from patients who were treated with daptomycin as salvage therapy for vancomycin failure (11).

In addition to vancomycin resistance, daptomycin nonsusceptibility in S. aureus is coupled to resistance to cationic host defense peptides (HDPs). HDPs are generally 12 to 50 amino acids in length with 2 to 9 lysine or arginine residues and 50% hydrophobic amino acids. In mammals, different HDPs are present in various tissue and cell types. In addition to having direct microbicidal activity, it is becoming apparent that they also modulate host immunity. Expression of HDPs may be inducible or constitutive, and frequently precursor peptides are proteolytically processed into more active forms (136).

Antimicrobial peptides such as cathelicidins and platelet microbicidal proteins (PMPs) are important components of innate immunity in bloodstream infection. For example, low serum concentrations of cathelicidin predict infectious disease mortality in dialysis patients (137), and staphylococcal resistance to PMPs is associated with complicated bacteremia and endocarditis (138, 139). We have previously documented clear cross-resistance between vancomycin and PMP in S. aureus, whereby exposure to vancomycin in vitro and in vivo selects for a PMP-resistant phenotype, emerging with a VISA phenotype in the setting of agr dysfunction (140).

As noted above, the daptomycin-calcium complex resembles HDPs because of charge, peptide content, and membrane target. In S. aureus, reduced susceptibility to daptomycin is associated with cross-resistance to some endovascular HDPs (114). This may suggest that exposure to daptomycin could confer reduced susceptibility to these HDPs, thereby generating an isolate that is more resistant to the innate immune response to endovascular infection (138, 141). More importantly, in cases of prolonged bacteremia, S. aureus persistence in the bloodstream may allow continued selection pressure by HDPs, thereby further selecting a daptomycin-NS phenotype, even in the absence of daptomycin itself. This hypothesis would suggest that S. aureus strains from cases of endocarditis, which in themselves are more resistant to HDPs such as PMPs, may have de novo higher daptomycin MICs. In another study of S. aureus strains isolated from the blood of patients prior to the release of daptomycin in the United States, resistance to PMP was associated with elevated daptomycin MICs (e.g., 1 μg/ml) (142). Interestingly, daptomycin MICs were not correlated with resistance to the neutrophil-derived HDP hNP-1 (142). Regardless, these data support an endogenous priming model, by which persistence in the host via resistance to HDPs such as PMP may be a risk factor for subsequent daptomycin nonsusceptibility. Thus, prompt clearance of bacteremia may be viewed as critical not only in reducing mortality and complications but also potentially in preserving the activity of antimicrobial therapy.

Beta-Lactam Antibiotics and Daptomycin

An interesting phenotype, commonly referred to as “the seesaw effect,” is observed in VISA and VRSA isolates; in this phenotype, the vancomycin MIC is inversely related to that of the antistaphylococcal β-lactams (97, 143, 144). The seesaw effect was first observed in VISA and VRSA strains that had excised the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec element (SCCmec) that carries mecA, the gene responsible for the MRSA phenotype (145). Subsequently, phenotypic oxacillin susceptibility was observed in VISA isolates that retained mecA (146–148). In vivo, these isolates revert to antistaphylococcal β-lactam resistance after discontinuation of vancomycin therapy (146). A similar effect is seen in some daptomycin-NS isolates, whereby oxacillin MICs are reduced, but not necessarily to below the susceptible breakpoint of 4 μg/ml (143). In murine models of infective endocarditis, oxacillin treatment alone did not reduce bacterial densities for such isolates, despite their increased oxacillin susceptibility (143). However, the combination of oxacillin plus daptomycin exhibited better overall efficacy than daptomycin alone at reducing the burden of daptomycin-NS S. aureus in target organs in these experiments (143). In vitro, synergy between oxacillin and daptomycin has been observed for both daptomycin-susceptible and -NS S. aureus strains (149–151); such synergy is observed even in daptomycin-NS isolates that maintain high oxacillin MICs (151). Mechanistically, coincubation of daptomycin with a β-lactam (including oxacillin, amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, and imipenem) induces a significant reduction in cell net positive surface charge, resulting in a reversion to daptomycin susceptibility (151, 152). The precise mechanism for this is unknown, but it has been postulated to relate to β-lactam-induced release of lipoteichoic acid from the cell wall (152). Enhanced daptomycin cell surface binding to a daptomycin-NS VISA isolate, in the presence of nafcillin, has been directly observed using a fluorescently labeled daptomycin molecule (152). Ceftaroline, an anti-MRSA β-lactam, in combination with daptomycin was additionally found to reduce cell wall thickness in a daptomycin-NS VISA isolate (153). Clinically, daptomycin plus antistaphylococcal β-lactam therapy was found to be effective at clearing daptomycin-NS S. aureus bacteremia among 7 patients with refractory bloodstream infections (152). The addition of ceftaroline to daptomycin after the emergence of daptomycin-NS S. aureus in a patient with endocarditis similarly resulted in clearance of the infection. Ceftaroline was shown to improve daptomycin bactericidal activity in vitro for this patient's isolate (154).

Synergy between daptomycin and β-lactams is also seen for ampicillin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. This combination therapy strategy was used to eradicate a persistent VRE bacteremia using daptomycin plus ampicillin, and better killing was achieved in vitro using simulated daptomycin at 4 mg/kg/day plus ampicillin than daptomycin 10-mg/kg/day monotherapy. As was described above for MRSA, ampicillin increased daptomycin binding to the bacterial surface (155). Most recently, ceftaroline has shown excellent synergy with daptomycin to treat a case of E. faecalis endocarditis with high-level gentamicin resistance (156).

Given the discussions above paralleling mechanisms of action and resistance between daptomycin and HDPs, it is not surprising that β-lactam antibiotics potentiate the antimicrobial properties of HDPs. Growth of MRSA and VRE strains that are highly resistant to β-lactams with either nafcillin or ampicillin, respectively, at concentrations far below the MIC results in a marked sensitization to killing by a variety of HDPs (155). The mechanism for the seesaw effect and the synergy between daptomycin and β-lactams remains to be explained at the cellular level. While daptomycin appears to bind better to the surface of β-lactam-treated MRSA, the changes that lead to this phenotype are not known. Nevertheless, this combination may prove to be the most potent one yet against MRSA and may be considered in salvage antibiotic regimens for persistent MRSA bacteremia.

Daptomycin Nonsusceptibility in Enterococcus

Emergence of daptomycin nonsusceptibility in Enterococcus, and in particular in vancomycin-resistant E. faecium and E. faecalis, during daptomycin therapy has been extensively documented (157–161). In addition, infections caused by daptomycin-NS enterococci have been observed in patients naive to daptomycin therapy (158, 159, 161). Daptomycin MICs for NS isolates from these patients are lower than those for daptomycin-NS enterococci isolated from patients with a daptomycin treatment history (e.g., geometric mean MIC of 28 μg/ml versus 6 μg/ml) (158). Fewer data exist to describe the mechanism of daptomycin-NS phenotypes in the enterococci compared to those described above for S. aureus. However, whole-genome sequencing of daptomycin-susceptible and -NS E. faecium (157, 160, 162) and E. faecalis (163, 164) strain pairs suggests that limited mutations in the bacterial genome are sufficient to elicit daptomycin MICs above the CLSI breakpoint of 4 μg/ml. Like in S. aureus, mutations to both cell envelope stress response system and genes specifically involved in phospholipid biosynthesis have been identified in daptomycin-NS Enterococcus.

The LiaFSR three-component regulatory system orchestrates cell envelope response to antimicrobial and HDP stress (165) and is analogous to the vraSR regulatory system in S. aureus (166). Mutation to this system has been identified in daptomycin-NS E. faecalis (164); introduction of the mutated liaF allele, which causes deletion of an isoleucine at position 177, into a daptomycin-susceptible parent strain by allelic exchange was shown to elevate the daptomycin MIC from 1 to 4 μg/ml (164), and this renders the isolate daptomycin tolerant (80). Similarly, many E. faecium strains with MICs on the high end of susceptible harbor mutations in one or more of liaF, liaS, and liaR genes (78), whereas E. faecium strains with daptomycin MICs of ≤2 μg/ml harbor wild-type alleles. Together, these data suggest that mutation to this system may be associated with initial genetic changes associated with development of daptomycin nonsusceptibility. However, this is not a universal mechanism for daptomycin nonsusceptibility in enterococci, as mutation to liaFSR is observed in only some of the daptomycin-NS Enterococcus isolates studied to date by whole-genome sequencing (157, 160, 162–164). Furthermore, the association between MIC and liaFSR mutation is observed only when MICs are measured by Etest (78). Nonetheless, these data suggest that the CLSI daptomycin breakpoint, for E. faecium in particular, may need to be reassessed. Recently, mutation to yycG, also a cell wall response regulator, was identified in a daptomycin-NS E. faecium strain (162).

Mutation to cls is also frequently associated with daptomycin-NS E. faecium and E. faecalis (Table 5). As mentioned above, Cls is a membrane-associated protein that catalyzes the formation of cardiolipin from two PG molecules. The Cls enzyme is comprised of two N-terminal putative transmembrane helices and two phosphatidylcholine-hydrolyzing phospholipase domains (PLDs). In Enterococcus (and Staphylococcus), each of the two PLD domains harbors a single conserved histidine kinase motif with an H217 putative active-site nucleophile (167). Various mutations to cls, predominantly in the region of the gene that encodes the N-terminal transmembrane helix, the linker region between the transmembrane domains and the PLD domains, and PLD1, have been observed in both in vivo- and in vitro-selected daptomycin-NS E. faecium and E. faecalis (Table 5). Unique cls mutations have been described in isogenic strain sets of daptomycin-NS E. faecium, suggesting that independent mutational events may occur in the same genetic background and lead to daptomycin nonsusceptibility (157, 160).

Table 5.

Mutations in the cardiolipin synthetase gene, cls, identified among daptomycin-nonsusceptible Enterococcus strains

| Species and mutation | Predicted Cls domain | Daptomycin MIC (μg/ml) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus faecium | |||

| H215R | Proximal to the PLD1 active site (within 10 Å) | 48a | 164 |

| H270R | Spacer regions between PLD1 and PLD2 | 32 | 157 |

| K60T | Linker region | 32 | 160 |

| MPL insertion at 110 | Linker region | 24a | 164 |

| N13I | N-terminal transmembrane helix | 32a | 164 |

| N13S | N-terminal transmembrane helix | 192 | 157 |

| N13T | N-terminal transmembrane helix | >256 | 160 |

| R218Q | HKD of PLD1 | 32a | 164 |

| R218Q | HKD of PLD1 | 48a | 164 |

| R218Q | HKD of PLD1 | 16 | 162 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | |||

| Deletion of K61 | Linker region | 12 | 164 |

| R218Q | HKD of PLD1 | 256 | 163 |

| N77-Q79 del | Linker region | 256 | 163 |

| R218Q | HKD of PLD1 | 512 | 163 |

MIC measured by Etest.

The specific mechanisms by which the various cls mutations lead to enterococcal daptomycin nonsusceptibility are currently being studied. Overexpression of Cls with the mutation R218Q in a daptomycin-susceptible E. faecalis strain was shown to result in an MIC increase from 4 μg/ml to 64 μg/ml (163). Paradoxically, introduction of this same mutation by allelic exchange into a daptomycin-susceptible E. faecium strain had no effect on the daptomycin MIC (162), although R281Q mutation has been observed in numerous daptomycin-NS E. faecium isolates (Table 5). The activity of purified, recombinant Cls from E. faecium harboring R218Q and H215R mutations was assessed in vitro (167). Both enzymes were associated with increased cardiolipin production compared to that with the wild-type enzyme (167), but differences in cardiolipin content were not observed when daptomycin-NS and -susceptible E. faecium and E. faecalis strains were evaluated (168). E. faecalis and E. faecium have significantly different phospholipid membrane contents, in that the E. faecalis membrane is more diverse in phospholipid content (168). Regardless, evaluation of E. faecium and E. faecalis cell membrane phospholipids by two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography revealed significantly lower PG and glycerolphospho-diglycodiacylglycerol contents in NS than in susceptible isolates (168). From this, it is possible to speculate that enhanced Cls activity may serve to alter membrane properties by depleting the membrane of PG, in a scenario analogous to that for MprF activity in S. aureus.

Recombinant Cls from both E. faecium and E. faecalis is strongly associated with the cell lipid bilayer, despite these proteins being cloned in the absence of the putative hydrophobic membrane-spanning domains to facilitate enzyme purification (167). The role of mutation to the transmembrane regions is therefore uncertain at present, although mutation at position 13, found in the N-terminal transmembrane helix, has been observed as the only cls mutation in three daptomycin-NS E. faecium strains (Table 5). Our own observations imply that mutation to N13 is found in enterococci with very high daptomycin MICs (e.g., 192 μg/ml) (157, 160), but this finding needs to be validated by evaluating the effect of this mutation on the daptomycin MIC when introduced into a daptomycin-susceptible strain.

Mutation in gdpD has been demonstrated in a daptomycin-NS E. faecalis strain (164). Like Cls, GdpD is involved in PG metabolism, but when the NS gdpD allele is introduced into a daptomycin-susceptible E. faecalis strain, it is not sufficient to confer nonsusceptibility to daptomycin (164). Interestingly, when coupled with mutation to liaF, mutation to gdpD results in a daptomycin-NS MIC (e.g., 24 μg/ml) (164).

In addition to these genes, a mutation was noted in the gene for cyclopropane fatty acid synthase (Cfa), an enzyme involved in the synthesis of cyclic fatty acids, which are important components of cell phospholipids that may affect fluidity and stabilization of the cell membrane, in daptomycin-NS E. faecium (162). In this isolate, the substitution found between the susceptible and NS isolates was a reversion to wild type in the NS isolate. The authors speculated that the change may have occurred as a compensatory response to daptomycin exposure in the patient. Some, but not all, daptomycin-NS E. faecium strains appear to have a less fluid cell membrane than the daptomycin-susceptible parental strain (157, 168), and similar to the case for S. aureus, cell membrane fluidity may impact the ability of daptomycin to insert into the membrane. Additional phenotypic changes to the cell wall have been associated with daptomycin-NS isolates. These include increased cell wall thickness, which was observed in some daptomycin-NS E. faecium (169) and E. faecalis (164) strains but not in others (157). Increased septal structures in daptomycin-NS versus -susceptible E. faecium and E. faecalis have also been noted by transmission electron microscopy (157, 164). We have found mutations to ezrA, which encodes a transmembrane protein that acts as a negative regulator of septation ring formation (ftsZ), in E. faecium with this phenotype (157).

Daptomycin Nonsusceptibility in Other Gram-Positive Bacteria

Clinical data regarding the use of daptomycin for the treatment of infections caused by the viridans group streptococci are limited, but for penicillin-resistant strains, daptomycin has been proposed as an alternative treatment to vancomycin for the treatment of serious infections. This possibility was evaluated in a rabbit model of aortic valve infective endocarditis caused by a penicillin-resistant Streptococcus mitis strain. High daptomycin MICs (e.g., >256 μg/ml) were observed in this study among 63 to 67% of S. mitis isolates recovered from endocardial vegetations in animals treated with 6 mg/kg/day and 10 mg/kg/day daptomycin, respectively (170). Interestingly, the seesaw effect was noted in these isolates, where the penicillin MIC dropped from 8 μg/ml to 1 μg/ml, concomitant with the daptomycin MIC increase (170). In vitro, daptomycin MICs of >256 μg/ml were observed in viridans streptococci of both the Mitis and Anginosus groups following exposure to inhibitory concentrations of daptomycin (170). Similarly, in an in vitro pharmacodynamics model of simulated endocardial vegetations, viridans group streptococci from the Mitis group (3 Streptococcus oralis isolates, 1 S. mitis isolate, and 1 S. gordonii isolate) all developed daptomycin MICs of >256 μg/ml within 72 h of a daptomycin dose equivalent to 8 mg/kg, although these data have not been peer reviewed to date (171). In contrast, using a rat fibrin clot model and a daptomycin dose to simulate the AUC of 8 mg/kg/day, a bactericidal effect was demonstrated for Streptococcus constellatus, Streptococcus oralis, and Streptococcus salivarius (172). None of these isolates developed elevated daptomycin MICs following daptomycin exposure (172). To our knowledge, only two case reports have documented clinical daptomycin failures associated with daptomycin-NS viridans streptococci (173, 174). Tascini and colleagues reported on a patient with mitral and aortic native valve S. oralis endocarditis treated with 6-mg/kg/day daptomycin. Despite defervescence and negative blood cultures, an increase in the mitral valve vegetation size was noted by transthoracic echocardiogram, with severe mitral regurgitation. The patient's aortic and mitral valves were replaced surgically, and S. oralis isolated from the mitral vegetation revealed an NS daptomycin MIC of 4 μg/ml, whereas the initial blood culture isolate had a daptomycin MIC of 0.094 μg/ml, as measured by Etest (173). The patient was treated with ceftriaxone with clinical success. In a second case, Palacio and colleagues reported on a patient treated with 6-mg/kg/day daptomycin for osteomyelitis and bacteremia caused by MRSA (174). Following 21 days of therapy, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit in septic shock with daptomycin-NS S. anginosus (MIC = 4 μg/ml) bacteremia. These data suggest the possibility of nonsusceptible isolates in patients treated with daptomycin off-label for endocarditis caused by viridans group Streptococcus.

Similar to the case for the viridans group streptococci, daptomycin MICs of >256 μg/ml have been reported among the Corynebacterium spp. A daptomycin-NS Corynebacterium striatum strain was recovered from the blood of a patient following two 6-week courses of daptomycin for the treatment of MRSA bacteremia and osteomyelitis (175), and a daptomycin-NS Corynebacterium jeikeium strain was isolated from a febrile neutropenic patient with 3 days of prior daptomycin therapy (176). Development of high-level daptomycin MICs in normal flora is a possible collateral effect of daptomycin therapy, although it is rarely observed.

SUSCEPTIBILITY TESTING

Broth Microdilution, Disk Diffusion, and Etest

Achieving reliable susceptibility results for daptomycin is complicated by the marked influence of inoculum concentration and calcium content in test media on daptomycin MICs. Both enterococcal and staphylococcal MICs increase greater than 5-fold when 107 CFU/ml is used in place of the standard inoculum of 105 CFU/ml (177, 178). The calcium concentration in the test medium is inversely related to daptomycin activity, and as such media with low calcium concentrations yield artificially high MICs. Optimal performance of broth microdilution (BMD) methods is achieved by supplementing Mueller-Hinton broth with calcium chloride salt to a final concentration of 50 mg/liter Ca2+(70), which must be confirmed prior to use of each lot of prepared medium by atomic absorption or a similar method. The addition of lysed horse blood or pyridoxal, supplements used for testing fastidious bacteria, does not appear to affect the calcium concentration or daptomycin MICs (179). In contrast, the control of calcium content in agar-based media is more problematic. Numerous studies have demonstrated variability in Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) between manufacturers and between lots of media produced by the same manufacturer (180, 181). For this reason, agar dilution is not recommended for daptomycin testing (70), as poor essential agreement (EA) with BMD is observed (182).

Disk diffusion testing is also not recommended for daptomycin by the CLSI, EUCAST, or FDA. In addition to variability in MHA calcium concentrations, the high molecular weight of daptomycin causes slow diffusion of this molecule through agar-based media. As such, similar to what is seen for vancomycin and the polymyxins, the observed difference in disk diffusion zone sizes between daptomycin-susceptible and -NS isolates is small. The impact of this was not recognized until after CLSI published disk diffusion breakpoints in 2005, when reports of clinical daptomycin failures in patients infected with isolates that tested daptomycin NS by BMD but susceptible by disk diffusion emerged (86, 183). Further studies revealed 13 to 100% very major errors (VME) (e.g., false susceptibility) among MRSA isolates with daptomycin-NS MICs by BMD (60, 184). Consequently, disk diffusion breakpoints were removed from CLSI standards in 2006, and daptomycin disks were removed from the U.S. market.

In contrast, Etest, another agar-based method, is frequently used by clinical laboratories to determine daptomycin MICs. The problems associated with variability in the calcium content of various MHAs have been addressed to a large extent by the addition of the equivalent of 40 mg/liter calcium along the length of the daptomycin gradient strip. Regardless, the performance of Etest remains dependent on test media, and reliable results can be achieved only if MHA is used (package insert). Early studies with daptomycin Etest strips further indicated that MHA containing ≤20 mg/liter calcium yielded Etest MIC results that were 2 to 4 log2 dilutions above those obtained using BMD (185). Conversely, calcium concentrations of >40 mg/liter have been shown to yield MICs 1 to 2 log2 dilutions lower than those obtained by BMD (186). The latter effect has not been evaluated for daptomycin-NS isolates, and so whether this may result in VME is unknown. Studies performed by AB Biodisk further narrowed this range, indicating that optimal performance of the daptomycin Etest strips is with MHA with Ca2+ concentrations of 25 to 40 mg/liter (187). However, no recommendation the on calcium content of MHA is currently included in the daptomycin Etest package insert (188). Rather, laboratories are instructed to perform quality control (QC) on each lot of MHA to qualify the lot for the daptomycin Etest (188). The use of QC strains may not be a sensitive measure by which to monitor calcium content in MHA: calcium at 2 mg/liter below the optimal range (23 mg/liter) was found to generate 40% major errors (ME) (e.g., false nonsusceptibility) among clinical MRSA isolates, whereas 100% of S. aureus ATCC 29213 and E. faecalis ATCC 29212 results fell within CLSI-defined QC ranges (187). However, the calcium effect is not the only factor associated with Etest performance. Using BBL MHA with a calcium concentration confirmed by atomic absorption to be 22 to 24 mg/liter, 13.5% VME were observed among 74 S. aureus strains that were NS by BMD (184). The authors of this study attributed the errors to the lack of an intermediate interpretative category for daptomycin, as this study was enriched with isolates with MICs at or near the daptomycin MIC breakpoint. Lot-to-lot variability in Etest performance has been documented, with categorical agreement (CA) (e.g., agreement in interpretation of susceptible versus NS) and essential agreement (e.g., agreement in MIC of ±1 doubling dilution) between Etest strip lots of as low as 73 and 74%, respectively (189). Compared to BMD, this interlot variability yielded 3 to 9% VME and 6 to 35% ME among clinical S. aureus strains (189). Etest MICs trend 0.5 to 1 log2 dilution higher than those obtained by BMD (190); essential agreement with BMD for S. aureus ranges from 79 to 100% (184, 191; reviewed in reference 179) and that for E. faecium and E. faecalis from 66.7 to 100% (179). This difference in performance of Etest between the enterococci and staphylococci may relate to the relative poor growth of Enterococcus on MHA, yielding Etest ellipses that may be more difficult for some observers to interpret (R. M. Humphries, unpublished observation). Thus, Etest may be used to reliably determine susceptibility to daptomycin by clinical laboratories, provided that MHA with an appropriate calcium content is used, as documented in the product specifications.

Performance of Commercial Susceptibility Test Systems in Evaluating Daptomycin MICs

Few published data are available on the performance of the automated susceptibility test systems for achieving accurate daptomycin MICs, although all major systems now include options for testing daptomycin. Performance data for the automated systems compared to CLSI reference BMD are summarized in Table 6. It is important to note that the few published studies contain few, if any, NS isolates (Table 6), and thus the ability of these test systems to identify daptomycin-NS isolates is largely unknown. Indeed, BD indicates that the ability of their system to detect daptomycin nonsusceptibility is unknown (192), although neither Siemens nor bioMérieux indicates this as a limitation in their respective product literature (193–195).

Table 6.

Essential agreement and error rates for automated antimicrobial test systems versus the CLSI reference broth microdilution methoda