Abstract

Aminoglycoside resistance in Campylobacter has been routinely monitored in the United States in clinical isolates since 1996 and in retail meats since 2002. Gentamicin resistance first appeared in a single human isolate of Campylobacter coli in 2000 and in a single chicken meat isolate in 2007, after which it increased rapidly to account for 11.3% of human isolates and 12.5% of retail isolates in 2010. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis indicated that gentamicin-resistant C. coli isolates from retail meat were clonal. We sequenced the genomes of two strains of this clone using a next-generation sequencing technique in order to investigate the genetic basis for the resistance. The gaps of one strain were closed using optical mapping and Sanger sequencing, and this is the first completed genome of C. coli. The two genomes are highly similar to each other. A self-transmissible plasmid carrying multiple antibiotic resistance genes was revealed within both genomes, carrying genes encoding resistance to gentamicin, kanamycin, streptomycin, streptothricin, and tetracycline. Bioinformatics analysis and experimental results showed that gentamicin resistance was due to a phosphotransferase gene, aph(2″)-Ig, not described previously. The phylogenetic relationship of this newly emerged clone to other Campylobacter spp. was determined by whole-genome single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), which showed that it clustered with the other poultry isolates and was separated from isolates from livestock.

INTRODUCTION

Campylobacter is one of the leading bacterial causes of food-borne illness in the United States and worldwide. Human illnesses are associated primarily with Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. In patients with culture-confirmed campylobacteriosis who require antimicrobial therapy, erythromycin and azithromycin are preferred for treatment. Fluoroquinolones are often used for empirical treatment because these drugs are also effective against Salmonella spp. Based on in vitro activity, other antimicrobials such as gentamicin, meropenem, and clindamycin may be viable alternative therapies.

The National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) is a national public health surveillance system that monitors the trends of antibiotic resistance in food-borne bacteria. The NARMS data showed that gentamicin resistance (Genr) in Campylobacter spp. has been very rare, occurring sporadically in human isolates since 2000 and first appearing in retail chicken in 2007 (0.7% prevalence) (1, 2). Since then, the number of Genr C. coli isolates from retail chicken has increased each year, rising to 12.8% in 2010, while no resistance was found in C. jejuni. Almost all Genr C. coli strains were isolated from western states of the United States and displayed very similar pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) patterns, suggesting a recent clonal expansion (2).

There have been several reports on the mechanisms of gentamicin resistance in Campylobacter. The gentamicin resistance gene aacA4 was reported in C. jejuni from a U.S. broiler house (3). In addition, a conjugative plasmid carrying resistance to gentamicin and other aminoglycosides was described in a clinical isolate of C. jejuni from a U.S. soldier deployed to Thailand (4). The plasmid-borne gene was initially annotated as aac(6′)-Ie/aph(2″)-Ia (also named aacA/aphD) that encodes a bifunctional enzyme. The determinant was later found to encode only the phosphotransferase activity and was named aph(2″)-If (5). A third example of aminoglycoside resistance in Campylobacter was associated with a genomic island carrying resistance to gentamicin and other aminoglycosides in a C. coli isolate recently reported from China (6). In this case, gentamicin resistance was attributed to an aac(6′)-Ie/aph(2″)-Ia gene. In order to investigate the mechanism of gentamicin resistance in C. coli recently emergent in U.S. retail chicken, we determined the genomic DNA sequences of two related strains. Although many C. coli genomes have been sequenced, none of the sequences were completed (7, 8). In this study, we have closed the gaps for one of the strains and described the first completed genome sequence of C. coli. We also determined the complete sequence of the multidrug-resistant (MDR) conjugative plasmid carried by this Genr C. coli strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture and MIC testing.

C. coli N29710 and N29716 were both isolated from retail chicken purchased in California, USA, in March 2011. C. jejuni N18880 was isolated from retail chicken purchased in Tennessee, USA, in August 2008. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed with a Sensititre (Trek Diagnostic Systems, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Cleveland, OH) according to the standardized NARMS protocols (2). Campylobacter was grown on blood plates (Remel, Lenexa, KS) or Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar plates (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD) under microaerophilic conditions (5% oxygen, 10% carbon dioxide, 85% nitrogen). Escherichia coli DH5α, used as host for cloning and expression, was grown on LB agar (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD).

Genome sequencing and analysis.

Genomic DNA was extracted with a DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was performed using a 454 GS FLX+ platform (Life Sciences, Branford, CT), and assembly was with Newbler V2.6 (Life Sciences, Branford, CT). The genome coverages are 108× and 98× for N29710 and N29716, respectively. The program BLAST (9, 10) was used to compare gene similarities. Contigs were mapped to other Campylobacter genomes in GenBank by NUCMER (11). Contigs with no match to the reference genome were compared to sequences in GenBank. If the contigs were similar to plasmid sequences in GenBank, raw sequencing reads of these contigs were searched by BLAST in an attempt to find reads that can circularize the plasmid. The contigs of N29710 were oriented by optical mapping (see details below). Gaps were closed by direct PCR and sequencing on an ABI 3730XL (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The genomes were annotated by the NCBI Prokaryotic Genomes Automatic Annotation Pipeline. Ten completed genome sequences of C. jejuni and 44 draft genomes of C. coli were downloaded from GenBank for comparative genomic analysis (7). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for each genome were called by NUCMER using the N29710 genome as the reference (11). In-house Perl scripts were used to extract SNPs from homologous regions of all genomes. Whole-genome SNPs were concatenated by position and used to construct a phylogenetic tree using FastTree (12).

Optical mapping.

Optical mapping was performed in-house. Colonies of N29710 grown overnight were picked into buffer, washed, and lysed according to the manufacturer's protocols (OpGen, Gaithersburg, MD) under conditions to minimize shear and prepare very high-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA. Several dilutions (1:5, 1:10, and 1:20) were prepared and allowed to equilibrate at room temperature for an hour to allow unspooling of HMW DNA. DNA concentration, quality, and length were determined, and 0.4 μl DNA of an appropriate dilution was applied to a derivatized glass coverslip and processed through washes, restriction digestion with NcoI, and Jo-Jo staining on the Argus mapping station (OpGen). The station then collected 5,000 to 50,000 molecular images in total from 40 to 45 microchannels, determined the size and order of restriction fragments for each molecule, and assembled the molecules into circular chromosomal maps with a minimum 30-fold coverage for each fragment.

Conjugation.

Conjugation was performed as described before (13). Briefly, a loopful of bacteria from an agar plate was resuspended in 200 μl MH broth; 10 μl of donor strain (N29710 or N29716) was spotted on top of 10 μl recipient strain C. jejuni N18880 on an MH agar plate and then incubated overnight. Each coculture was scraped from the plate, resuspended in MH broth, and plated on blood agar plates supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (tetracycline, 8 μg/ml; erythromycin, 64 μg/ml) to select for transconjugants.

Cloning and expression.

The coding region of aph(2″)-Ig was synthesized and cloned into the HindIII site in vector pUC57 by the company Genscript (Genscript, Piscataway, NJ). One extra base was added in front of the starting codon to ensure in-frame translation with the lacZ gene start codon. The construct was screened for the desired orientation. The plasmids were then transformed into E. coli DH5α. Ampicillin (100 μg/ml) was added to the growth medium to maintain the plasmids. To induce expression of aph(2″)-Ig, isopropylthio-β-galactoside (IPTG) (final concentration, 0.5 mM) was added to the MH broth (Sensititre, Trek Diagnostic Systems, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Cleveland, OH), which was used to grow E. coli for MIC testing, and the expression of aph(2″)-Ig was measured by determining the MICs of gentamicin and kanamycin against the E. coli host (see Table 2).

Table 2.

MICs for bacterial strains studied

| Strain | MIC (mg/ml)a |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP | AZI | ERY | GEN | KAN | STR | SIX | TET | |

| C. coli | ||||||||

| Donors | ||||||||

| N29710 | 2 | 0.03 | 0.12 | >32 | >64 | ≤32 | 64 | >64 |

| N29716 | 2 | 0.03 | 0.12 | >32 | >64 | ≤32 | 64 | 64 |

| Recipient N18880 | ≤1 | >64 | >64 | 0.5 | ≤8 | ≤32 | 128 | 0.5 |

| Transconjugants | ||||||||

| N29710 × N18880 | ≤1 | >64 | >64 | >32 | >64 | ≤32 | 64 | >64 |

| N29716 × N18880 | ≤1 | >64 | >64 | >32 | >64 | ≤32 | 128 | >64 |

| E. coli | ||||||||

| DH5α/puc57 | >32 | 4 | 64 | 0.25 | ≤8 | ≤32 | ≤16 | ≤4 |

| DH5α/puc57 + aph(2″)-Ig | >32 | 2 | 64 | 32 | >64 | ≤32 | ≤16 | ≤4 |

Abbreviations: AMP, ampicillin; AZI, azithromycin; ERY, erythromycin; GEN, gentamicin; KAN, kanamycin; STR, streptomycin; SIX, sulfisoxazole; TET, tetracycline; TMP, trimethoprim; SMZ, sulfamethoxazole.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under accession numbers ANMS00000000, CP004066, CP004067, and CP004068 for the N29716 and N29710 chromosomes, plasmid pN29710-1, and plasmid pN29710-2, respectively.

RESULTS

Genomes and phylogeny.

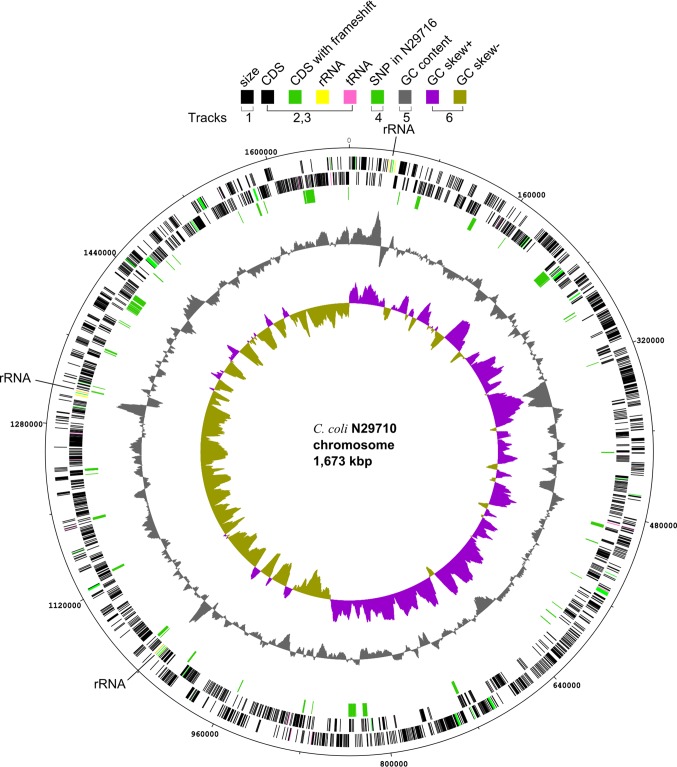

The genome of C. coli strain N29710 was completely sequenced and closed, which revealed one circular chromosome of 1,673,221 bp (Fig. 1). The size of the C. coli genome was similar to those of the published genomes of C. jejuni, which ranged from 1.62 Mb to 1.85 Mb (8, 14–20). The sequence of strain N29716 consisted of 23 contigs, with an N50 length of 308 kb. The GC content of both genomes was 31.4%. The GC skew [(G − C)/(G + C)] plot showed an asymmetric compositions of G and C on two sides of the chromosome, suggesting the replication origin and terminus (21). This asymmetric GC skew was observed previously in other Campylobacter and Salmonella genomes (7, 22). The two Genr strains were highly similar to each other, differing in only 2,107 (0.001%) chromosomal SNPs. The SNP distribution on the genomes was not random (Fig. 1), and 98% of the SNPs (n = 2,061) were clustered in 20 small regions in 12% of the genome, with each region having 15 to 268 SNPs per 10-kb region. The rest of the genome had an average of 0.3 SNP per 10-kb region. In closely related strains, a high density of SNPs indicates recombination (23, 24). We therefore inferred that the clustered SNPs were the results from recombination, that there had been at least 20 recombination events since the split of these two closely related strains, and that these events introduced most of the variation between these strains.

Fig 1.

Chromosome features of Campylobacter coli strain N29710. Tracks are numbered from outside in, and the color code is given in the top of the figure. Track 1, size. Tracks 2 and 3, coding sequence (CDS), rRNA, and tRNA on forward and reverse strands, respectively. Three copies of rRNA operons are also marked on the map. Track 4, SNP between N29710 and N29716. Track 5, GC content. Track 6, GC skew [(G − C)/(G+C)]. The circular map was drawn using dnaplotter (22).

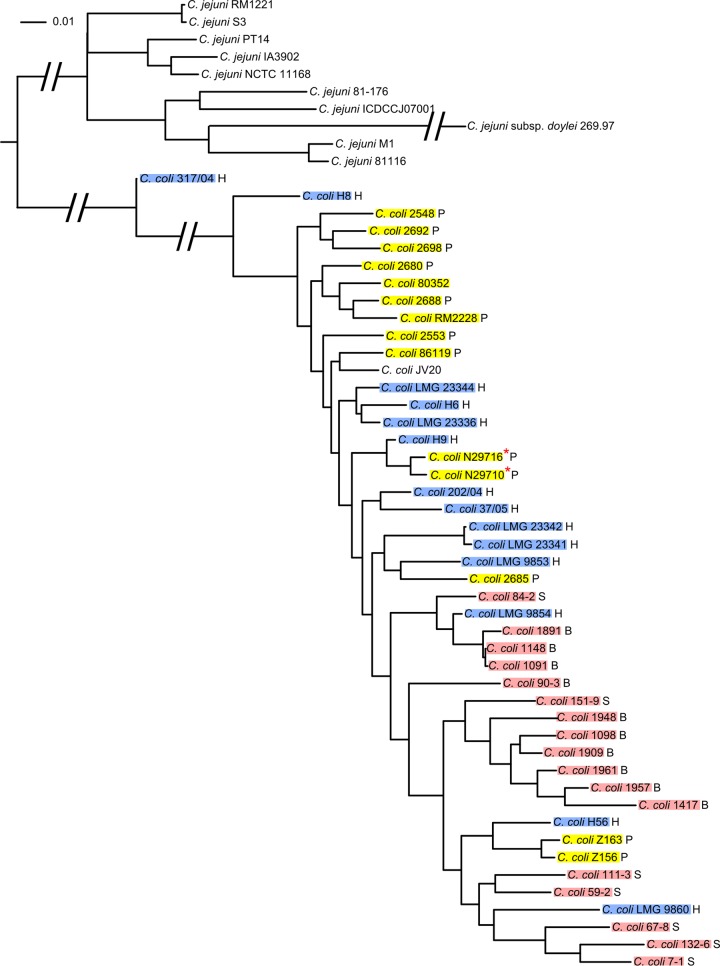

In order to understand the phylogenetic relationship of the gentamicin-resistant clones to other C. coli and C. jejuni strains, whole-genome SNPs were extracted from all draft genomes of C. coli and all completed genomes of C. jejuni in GenBank at the time of this study. A total of 110,051 SNPs have been identified and were used to construct a phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2). The two gentamicin-resistant strains are closely related to each other and clustered together with the other C. coli isolates from poultry. Interestingly, they are also closely related to a human clinical isolate, H9, from Switzerland. In the phylogenetic tree, isolates from the same animal source (poultry or livestock) generally clustered together, and isolates from different sources were separated in different clusters, while human clinical isolates were embedded in different clusters. This implies that variations may exist to differentiate C. coli isolates by animal source.

Fig 2.

Phylogenetic tree generated from whole-genome SNPs. WGS data for C. coli and the complete genome sequence of C. jejuni were downloaded from GenBank (see Materials and Methods) and compared to those for C. coli N29710. H, human isolate; P, poultry isolate; B, bovine isolate; S, swine isolate. Human isolates are shaded blue, poultry isolates are shaded yellow, and swine and bovine isolates are shaded pink. The two strains sequenced in this study are marked with red stars. All bootstrap values are above 99% and are not shown.

Plasmids and ARGs.

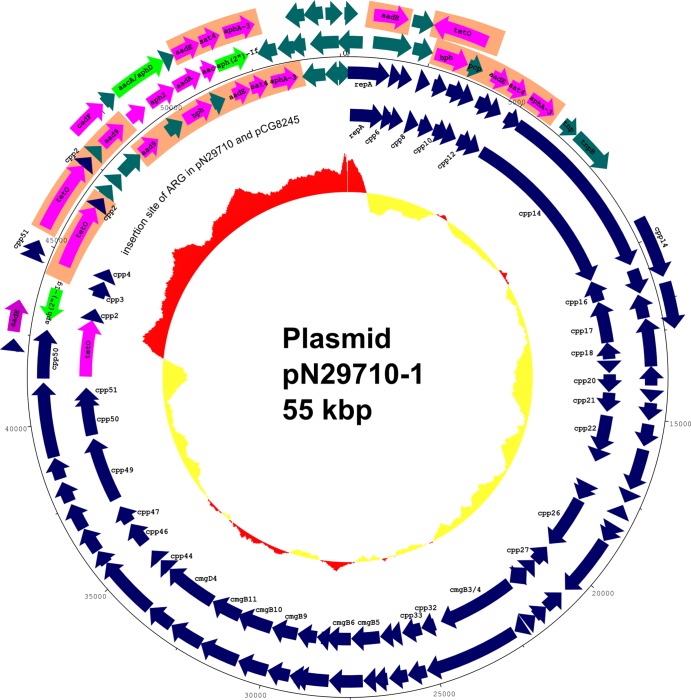

The genome sequence of the two Genr C. coli strains revealed that an essentially identical multiple-drug resistance (MDR) plasmid, pN29710-1, was present in both strains. The plasmids differed only in three unconfirmed SNPs. pN29710-1 is approximately 55 kbp and can be described as a mosaic plasmid that has multiple antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) inserted into a conjugative plasmid backbone. The plasmid backbone of pN29710-1 is highly similar to the previously reported pTet plasmid (25), sharing 95% identity in nucleotide sequence on average. However, except for the tet(O) gene, the other ARGs in pN29710-1 are absent in pTet and are likely a recent addition to the plasmid. One gene was inserted upstream of tet(O), while the others were inserted downstream of cpp2 and replaced cpp3 and cpp4 in pTet (Fig. 3; Table 1). The GC contents of the backbone and ARG cluster differ significantly. The backbone has 28.3% GC, which is closer to the GC content of the C. coli chromosome. The ARG cluster has a 42.5% GC, suggesting a recent exogenous acquisition of these genes by Campylobacter.

Fig 3.

Features of multidrug resistance plasmid pN29710-1 and comparison of antimicrobial resistance gene clusters in pN29710-1, SX81, and pCG8245. Tracks are numbered from outside in. Track 1, antimicrobial resistance island in SX81 (6). Track 2, antimicrobial resistance gene cluster in pCG8245 (4). Track 3, size of pN29710-1. Track 4, pN29710-1. Track 5, pTet (25), with large open area corresponding to insertion site of ARG clusters of pCG8245 and pN29710-1. Track 6, GC content of pN29710-1. Regions of GC content above average for the entire plasmid are drawn outside the ring and in red, while regions of GC content below average are inside the ring and in yellow. Gentamicin resistance genes are colored green, other antimicrobial resistance genes are colored magenta, and homologous regions in the antibiotic gene clusters are shaded orange.

Table 1.

Annotation of genes in the ARG region of pN29710-1

| Gene or ORF | Codon region | Length (amino acids) of: |

Amino acid identity (%) | Annotation/Blast hit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein in pN29710-1 | Homologous proteina | ||||

| aph(2″)-Ig | 43008–43928 | 306 | 299 | 148/283 (52) | Putative aminoglycoside phosphotransferase/Enterococcus faecium/3HAM_A |

| tet(O) | 44627–46546 | 639 | 639 | 637/639 (99) | Tetracycline resistance protein/Campylobacter jejuni/YP_005655562 |

| ccp2 | 46598–46771 | 57 | 57 | 57/57 (100) | Hypothetical protein/Campylobacter jejuni/YP_063447 |

| orf4 | 46969–47358 | 129 | 170 | 128/129 (99) | Hypothetical protein/pTet_35 in Campylobacter jejuni/YP_247563 |

| orf5 | 47382–47762 | 126 | 265 | 126/126 (100) | Hypothetical protein/Bacteroides sp./ZP_07940482 |

| pnp | 47787–48557 | 256 | 256 | 256/256 (100) | Uridine phosphorylase/Bacteroides sp./ZP_06089331 |

| aad9 | 48582–49238 | 218 | 258 | 216/216 (100) | Streptomycin 3″-adenylyltransferase/Bacteroides sp./ZP_06089332 |

| orf8 | 49560–50105 | 181 | 181 | 174/181 (96) | Hypothetical protein/Bacteroides nordii/ZP_00371008 |

| hph | 50165–51082 | 305 | 305 | 305/305 (100) | Hygromycin resistance protein/Campylobacter coli/ZP_00371007 |

| pcp | 51087–51506 | 139 | 139 | 139/139 (100) | Pyroglutamyl-peptidase/Bacteroides sp./ZP_04541315 |

| aadE | 51750–52283 | 177 | 206 | 177/177 (100) | Streptomycin aminoglycoside 6-adenyltransferase/Phascolarctobacterium succinatutens/ZP_08076821 |

| sat4 | 52280–52822 | 180 | 180 | 179/180 (99) | Streptothricin acetyltransferase/Staphylococcus epidermidis/YP_187540 |

| aphA-3 | 52915–53709 | 264 | 264 | 264/264 (100) | Aminoglycoside 3′-phosphotransferase/Staphylococcus epidermidis/YP_187539 |

Homologous protein from the organism listed in the annotation/Blast hit column.

To confirm that the function of pN29710-1 is related to resistance, conjugation was performed using N29710 or N29716 as the donor strain and C. jejuni N18880 as the recipient. The donor strains are resistant to tetracycline and gentamicin and susceptible to erythromycin, while the recipient strain is susceptible to tetracycline and gentamicin and resistant to erythromycin. Transconjugants were selected by incubating the strains in medium containing tetracycline and erythromycin. Phenotypic expression of the antimicrobial resistance genes was demonstrated by determining the MIC. The results indicated that transconjugants were resistant to tetracycline, gentamicin, and erythromycin (Table 2).

The ARG cluster in pN29710-1 has at least seven genes related to antibiotic resistance (Table 1). Comparison of this cluster to other gentamicin resistance islands/plasmids described in Campylobacter indicated that the cluster shares similarity with the multiple aminoglycoside resistance genomic island present in C. coli SX81 (6) and the multidrug resistance plasmid pCG8245 in C. jejuni (4) but also has unique genes of its own (Fig. 1). All three of them have an identical gene cluster of aadE-sat4-aphA-3 (Fig. 1), which confer resistance to streptomycin, streptothricin, and kanamycin, respectively (4). In addition, both pN29710-1 and pCG8245 have full-length tet(O) coding regions, in contrast to a truncated one in SX81, as well as a hygromycin resistance gene and a streptomycin modification gene, aad9. However, the gentamicin resistance determinant in pN29710-1 is distinct. A bifunctional enzyme encoded by aac(6′)-Ie/aph(2″)-Ia is responsible for the gentamicin resistance phenotype in C. coli SX81. A phosphotransferase gene, aph(2″)-If, is responsible for the gentamicin resistance in pCG8245. The aph(2″)-Ia and aph(2″)-If genes share 82% amino acid identity. We identified a novel gene in pN29710-1 that shares 52% amino acid identity to another aminoglycoside-2″-phosphotransferase gene, which gives rise to high level of gentamicin resistance in Enterococcus faecium (26). We designated this allele aph(2″)-Ig to follow the naming scheme used for the last described aph(2″) gene (5). The aph(2″)-Ig shares 29% and 28% aa identity to aph(2″)-Ia and aph(2″)-If, respectively.

To test whether aph(2″)-Ig in pN29710 confers resistance to gentamicin, we had this gene synthesized and cloned in plasmid puc57 under control of the lacZ promoter by Genscript (Piscataway, NJ). We then expressed the gene in E. coli DH5α with the addition of 0.5 mM IPTG to the growth medium. The MIC of gentamicin tested against DH5α/puc57 with aph(2″)-Ig increased 128-fold (from 0.25 to 32 μg/ml) compared to that for the vector alone [DH5α/puc57 without aph(2″)-Ig]. The MIC of kanamycin also increased 8-fold, from 8 to 64 μg/ml. This indicated that the aph(2″)-Ig confers resistance to both gentamicin and kanamycin.

No other genes encoding known antibiotic-modifying enzymes were found in the chromosome of either C. coli strain. In addition to the large conjugative plasmid pN29710-1, N29710 also harbored a small, 3.7-kb plasmid, pN29710-2, which encodes a replication protein, a transportation protein, a mobilization protein, and a hypothetical protein. It does not carry any genes related to antibiotic resistance. Plasmid pN29710-2 was not present in N29716.

DISCUSSION

The recent appearance of gentamicin resistance in Campylobacter, particularly C. coli, has occurred suddenly, in strains from both food and human clinical cases (1, 2). Although the human isolates have diverse PFGE patterns, the C. coli strains isolated from retail meat have very similar PFGE patterns, indicating spread by clonal expansion in the U.S. retail meat supply. Our whole-genome sequencing data revealed that the gentamicin resistance determinant is carried on a plasmid backbone common in Campylobacter but previously known to carry mainly tetracycline resistance (25). The plasmid, designated pN29710-1, appears to have evolved recently from a pTet plasmid ancestor by insertion of multiple antibiotic resistance genes. Considering the mobility of the conjugative plasmid, the gentamicin resistance could be expected to spread to the other clones of C. coli and C. jejuni in the future, particularly in poultry production environments where gentamicin is routinely used. These plasmids also may act as a vehicle to pick up and spread other antibiotic resistance genes in C. coli and C. jejuni. pTet-like plasmids are widely spread in Campylobacter. Our survey of the whole genome sequence in GenBank indicated that 30% of the C. coli and 15% of the C. jejuni strains harbored a similar plasmid. Other antibiotic resistance genes had been reported to have inserted into the plasmid at the same site in a strain from Thailand (4). Our experimental results suggest that the gentamicin resistance phenotype might be due to a novel phosphotransferase allele, APH(2″)-Ig. Six other forms of the aph(2″) gene have been described, and two of them have been reported in Campylobacter and caused gentamicin resistance (4, 6). The prevalence of aph(2″) in Campylobacter suggests that it may be a common mechanism for gentamicin resistance in this genus.

Our comparative genomics analysis of the two closely related strains of C. coli suggests that most of the strain variations originated from lateral gene transfer and that lateral gene transfer may play a more significant role than point mutations in the evolution of C. coli. This is consistent with the finding from comparative genomics analysis of 27 Campylobacter strains by Snipen et al., which suggest that Campylobacter is not very clonal and evolves from frequent exchange of large segments of horizontally transmitted DNA (27). There is evidence from multilocus sequence typing (MLST) studies that there is DNA exchange in Campylobacter, even between the two species C. coli and C. jejuni (28, 29). In the two strains we sequenced, regions of lateral gene transfer included a housekeeping gene, gltA, which is one of the seven markers in the current MLST scheme for Campylobacter (www.pubmlst.net). Recent recombination events that cause variations in one locus will likely have a large impact on the MLST results for Campylobacter spp. because the assay is based on just seven loci. Therefore, a typing method based on a whole-genome approach would be more accurate for assessing strain relatedness in Campylobacter.

MLST data show that different sequence types are associated with Campylobacter strains from different hosts, and it is possible to estimate the source of contamination by the genotype of the isolate (30–32). The phylogenetic tree of C. coli based on SNPs of the WGS data confirms that isolates from poultry and livestock generally cluster by source. The human isolates are distributed across distinct poultry and livestock clusters, suggesting that the original source of contamination for human cases may be attributed with more certainty if whole-genome sequence information is used for typing of isolates.

WGS is becoming an important tool for investigating the epidemiology of infectious diseases and the evolutionary relationships among pathogens. In this study, we used WGS to understand an emergent antibiotic resistance phenomenon. Although the genomes of many C. coli strains had been sequenced, none of the sequences was completed. As the methods for molecular epidemiology are established, the availability of complete reference genomes is important. This completed genome sequence of C. coli can now be used as a reference strain in future WGS studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Beilei Ge for suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript and the FDA NARMS team for laboratory support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 August 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System Enteric bacteria 2010 human isolates final report. http://www.cdc.gov/narms/pdf/2010-annual-report-narms.pdf Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Food and Drug Administration National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System NARMS retail meat annual report, 2011. http://www.fda.gov/AnimalVeterinary/SafetyHealth/AntimicrobialResistance/NationalAntimicrobialResistanceMonitoringSystem/default.htm U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee MD, Sanchez S, Zimmer M, Idris U, Berrang ME, McDermott PF. 2002. Class 1 integron-associated tobramycin-gentamicin resistance in Campylobacter jejuni isolated from the broiler chicken house environment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3660–3664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nirdnoy W, Mason CJ, Guerry P. 2005. Mosaic structure of a multiple-drug-resistant, conjugative plasmid from Campylobacter jejuni. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2454–2459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toth M, Frase H, Antunes NT, Vakulenko SB. 2013. Novel aminoglycoside (2″) phosphotransferase identified in a Gram-negative pathogen. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:452–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qin S, Wang Y, Zhang Q, Chen X, Shen Z, Deng F, Wu C, Shen J. 2012. Identification of a novel genomic island conferring resistance to multiple aminoglycoside antibiotics in Campylobacter coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:5332–5339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lefebure T, Bitar PD, Suzuki H, Stanhope MJ. 2010. Evolutionary dynamics of complete Campylobacter pan-genomes and the bacterial species concept. Genome Biol. Evol. 2:646–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fouts DE, Mongodin EF, Mandrell RE, Miller WG, Rasko DA, Ravel J, Brinkac LM, DeBoy RT, Parker CT, Daugherty SC, Dodson RJ, Durkin AS, Madupu R, Sullivan SA, Shetty JU, Ayodeji MA, Shvartsbeyn A, Schatz MC, Badger JH, Fraser CM, Nelson KE. 2005. Major structural differences and novel potential virulence mechanisms from the genomes of multiple Campylobacter species. PLoS Biol. 3:e15. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delcher AL, Phillippy A, Carlton J, Salzberg SL. 2002. Fast algorithms for large-scale genome alignment and comparison. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:2478–2483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. 2010. FastTree 2—approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One 5:e9490. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Bystricky P, Adeyeye J, Panigrahi P, Ali A, Johnson JA, Bush CA, Morris JG, Jr, Stine OC. 2007. The capsule polysaccharide structure and biogenesis for non-O1 Vibrio cholerae NRT36S: genes are embedded in the LPS region. BMC Microbiol. 7:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parkhill J, Wren BW, Mungall K, Ketley JM, Churcher C, Basham D, Chillingworth T, Davies RM, Feltwell T, Holroyd S, Jagels K, Karlyshev AV, Moule S, Pallen MJ, Penn CW, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Rutherford KM, van Vliet AH, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. 2000. The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature 403:665–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearson BM, Gaskin DJ, Segers RP, Wells JM, Nuijten PJ, van Vliet AH. 2007. The complete genome sequence of Campylobacter jejuni strain 81116 (NCTC11828). J. Bacteriol. 189:8402–8403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofreuter D, Tsai J, Watson RO, Novik V, Altman B, Benitez M, Clark C, Perbost C, Jarvie T, Du L, Galan JE. 2006. Unique features of a highly pathogenic Campylobacter jejuni strain. Infect. Immun. 74:4694–4707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang M, He L, Li Q, Sun H, Gu Y, You Y, Meng F, Zhang J. 2010. Genomic characterization of the Guillain-Barre syndrome-associated Campylobacter jejuni ICDCCJ07001 Isolate. PLoS One 5:e15060. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friis C, Wassenaar TM, Javed MA, Snipen L, Lagesen K, Hallin PF, Newell DG, Toszeghy M, Ridley A, Manning G, Ussery DW. 2010. Genomic characterization of Campylobacter jejuni strain M1. PLoS One 5:e12253. 10.1371/journal.pone.0012253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Revez J, Schott T, Rossi M, Hanninen ML. 2012. Complete genome sequence of a variant of Campylobacter jejuni NCTC 11168. J. Bacteriol. 194:6298–6299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper KK, Cooper MA, Zuccolo A, Law B, Joens LA. 2011. Complete genome sequence of Campylobacter jejuni strain S3. J. Bacteriol. 193:1491–1492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frank AC, Lobry JR. 1999. Asymmetric substitution patterns: a review of possible underlying mutational or selective mechanisms. Gene 238:65–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carver T, Thomson N, Bleasby A, Berriman M, Parkhill J. 2009. DNAPlotter: circular and linear interactive genome visualization. Bioinformatics 25:119–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Croucher NJ, Harris SR, Fraser C, Quail MA, Burton J, van der Linden M, McGee L, von Gottberg A, Song JH, Ko KS, Pichon B, Baker S, Parry CM, Lambertsen LM, Shahinas D, Pillai DR, Mitchell TJ, Dougan G, Tomasz A, Klugman KP, Parkhill J, Hanage WP, Bentley SD. 2011. Rapid pneumococcal evolution in response to clinical interventions. Science 331:430–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris SR, Feil EJ, Holden MT, Quail MA, Nickerson EK, Chantratita N, Gardete S, Tavares A, Day N, Lindsay JA, Edgeworth JD, de Lencastre H, Parkhill J, Peacock SJ, Bentley SD. 2010. Evolution of MRSA during hospital transmission and intercontinental spread. Science 327:469–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Batchelor RA, Pearson BM, Friis LM, Guerry P, Wells JM. 2004. Nucleotide sequences and comparison of two large conjugative plasmids from different Campylobacter species. Microbiology 150:3507–3517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young PG, Walanj R, Lakshmi V, Byrnes LJ, Metcalf P, Baker EN, Vakulenko SB, Smith CA. 2009. The crystal structures of substrate and nucleotide complexes of Enterococcus faecium aminoglycoside-2″-phosphotransferase-IIa [APH(2″)-IIa] provide insights into substrate selectivity in the APH(2″) subfamily. J. Bacteriol. 191:4133–4143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snipen L, Wassenaar T, Altermann E, Olson J, Kathariou S, Lagesen K, Takamiya M, Knochel S, Ussery DW, Meinersmann RJ. 2012. Analysis of evolutionary patterns of genes in Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli. Microb. Inform. Exp. 2:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dingle KE, Colles FM, Falush D, Maiden MC. 2005. Sequence typing and comparison of population biology of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:340–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheppard SK, McCarthy ND, Falush D, Maiden MC. 2008. Convergence of Campylobacter species: implications for bacterial evolution. Science 320:237–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCarthy ND, Colles FM, Dingle KE, Bagnall MC, Manning G, Maiden MC, Falush D. 2007. Host-associated genetic import in Campylobacter jejuni. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13:267–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheppard SK, Dallas JF, MacRae M, McCarthy ND, Sproston EL, Gormley FJ, Strachan NJ, Ogden ID, Maiden MC, Forbes KJ. 2009. Campylobacter genotypes from food animals, environmental sources and clinical disease in Scotland 2005/6. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 134:96–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheppard SK, Dallas JF, Strachan NJ, MacRae M, McCarthy ND, Wilson DJ, Gormley FJ, Falush D, Ogden ID, Maiden MC, Forbes KJ. 2009. Campylobacter genotyping to determine the source of human infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:1072–1078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]