Abstract

It is unclear whether the genetic background of drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa was disseminated from a certain clone. Thus, we performed MLST (multilocus sequence typing) of 896 P. aeruginosa isolates that were nonsusceptible to imipenem, meropenem, or ceftazidime. This revealed 254 sequence types (STs), including 104 new STs and 34 STs with novel alleles. Thirty-three clonal complexes and 404 singletons were found. In conclusion, drug-resistant P. aeruginosa clones can be developed from diverse genetic backgrounds.

TEXT

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most common opportunistic pathogens and can cause severe diseases in humans, especially patients in intensive care units, burn centers, and cystic fibrosis centers (1–4). Infections caused by P. aeruginosa are often difficult to treat and are a great challenge to physicians and patients, raising morbidity and mortality rates (5, 6). Previous studies have revealed that the number of drug-resistant P. aeruginosa strains is increasing and the rate of resistance to carbapenems goes up every year (7–9). For instance, The CAPITAL surveillance program tested the susceptibility of 2,722 P. aeruginosa isolates, which revealed that the rates of resistance to imipenem, meropenem, and ceftazidime were 21.9, 15.4, and 15.2%, respectively (10). MLST (multilocus sequence typing) is an unambiguous molecular typing method that is used mostly to assess local outbreaks of infections (11–13). Study of population genetic backgrounds is also an application for MLST. For example, previous studies have indicated that the P. aeruginosa population structure is nonclonal (14–17). Specifically, Kidd et al. collected 501 P. aeruginosa isolates from an extensive region and various sources and identified 274 different sequence types (STs) that were confirmed as nonclonal (18). Some studies have focused on different geographic areas, but the samples used were of limited size or from the environment (16, 18). A large-scale epidemiological study of drug-resistant P. aeruginosa based on MLST has not been conducted in China. This study was conducted in order to investigate the drug resistance of P. aeruginosa in China and its genetic background based on MLST.

A total of 2,818 P. aeruginosa isolates were collected in 2010 from 65 hospitals in 22 regions of China. Susceptibilities to 16 antimicrobial agents were evaluated by the disk diffusion method. The results were interpreted according to the 2012 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (19), and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 was used as the control. The results showed that carbapenems (imipenem and meropenem), cephalosporins (cefepime and ceftazidime), penicillins (piperacillin and tazobactam-piperacillin), quinolones (ciprofloxacin), and aminoglycosides (amikacin and gentamicin) were more active than other drugs, with susceptibility rates ranging from 71.2 to 85.2%. The rates of isolate resistance to imipenem, meropenem, and ceftazidime were 23.1, 18.1, and 15.3%, respectively. Cefoperazone, sulbactam-cefoperazone, and aztreonam were less active, with susceptibility rates ranging from 48.7 to 55.1% and intermediate-susceptibility rates (19.1 to 28.5%) higher than those of other drugs. Colistin was the most active of these antimicrobials (95.8% susceptibility).

Since carbapenems and ceftazidime are currently the most widely used effective anti-Pseudomonas drugs, we selected 896 imipenem-, meropenem-, or ceftazidime-nonsusceptible isolates for a further MLST study to investigate the clonal relationships among drug-nonsusceptible isolates. This MLST study was performed in accordance with the study of Curran et al. (14), and the results were compared to the MLST database of P. aeruginosa (http://pubmlst.org/paeruginosa/). Of the 896 isolates, 632 belonged to 116 known STs, 201 demonstrated 104 new STs (new combinations of known alleles), and 63 others belonged to 34 new STs (STs contain novel alleles of certain genes). Ten STs with 10 or more isolates made up the primary part of the total STs (38.17%), i.e., ST244, ST277, ST235, ST274, ST292, ST316, ST699, ST357, ST270, and ST313.

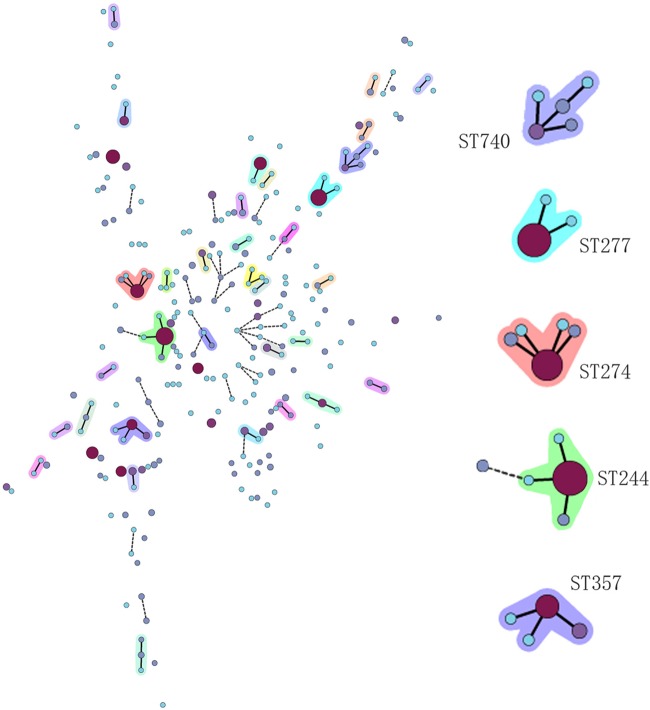

To investigate the clonal relationships of our 896 isolates, BioNumerics (version 6.6.4; Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) was used to create a minimum spanning tree and cluster STs into clonal complexes (CCs) (Fig. 1). A CC was composed of at least two STs with single-locus variants (SLVs), in which every ST shared at least six of the seven loci with at least one other member of the complex. A singleton was defined as an ST that was not grouped into any CC. A total of 33 CCs were detected. Four main CCs had more than two SLVs in the cluster, i.e., CC244, CC274, CC357, and CC740. Another four CCs, CC231, CC313, CC527, and CC620, had two SLVs in their clusters. The other 25 CCs had just one SLV in their clusters. Four hundred four isolates belonged to singletons, which were scattered around with no SLVs. Generally, a nonclonal epidemic structure was observed, which was in accordance with previous studies, such as that of Kidd et al. (18).

Fig 1.

Minimum spanning tree. Each circle represents one ST, and the larger the circle area, the greater the number of isolates. A solid or dashed line between circles means that the two linked circles have at least six or five of seven loci in common, respectively. The circles without links are singletons or STs different at more than four of seven loci. The shaded circles are CCs. On the right are the five large CCs.

Although the whole population was nonclonal, there were several large CCs, which meant that the population was partially clonal, and some of those CCs contained globally spread STs and were related to local outbreaks of P. aeruginosa infections, such as ST235, ST244, ST357, etc. Spain reported two outbreaks of P. aeruginosa in 2007 and 2008, one of which was caused by ST235 in a hematology department (20). South Korea also reported the dissemination of multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa belonging to ST235 (21). ST244 and ST235 were responsible for an outbreak of infections with P. aeruginosa that carried the PER-1 β-lactamase in Poland (11). ST357 producing the IMP-7 metallo-β-lactamase has been reported in Singapore, and it also spread in the Czech-Polish border region (22).

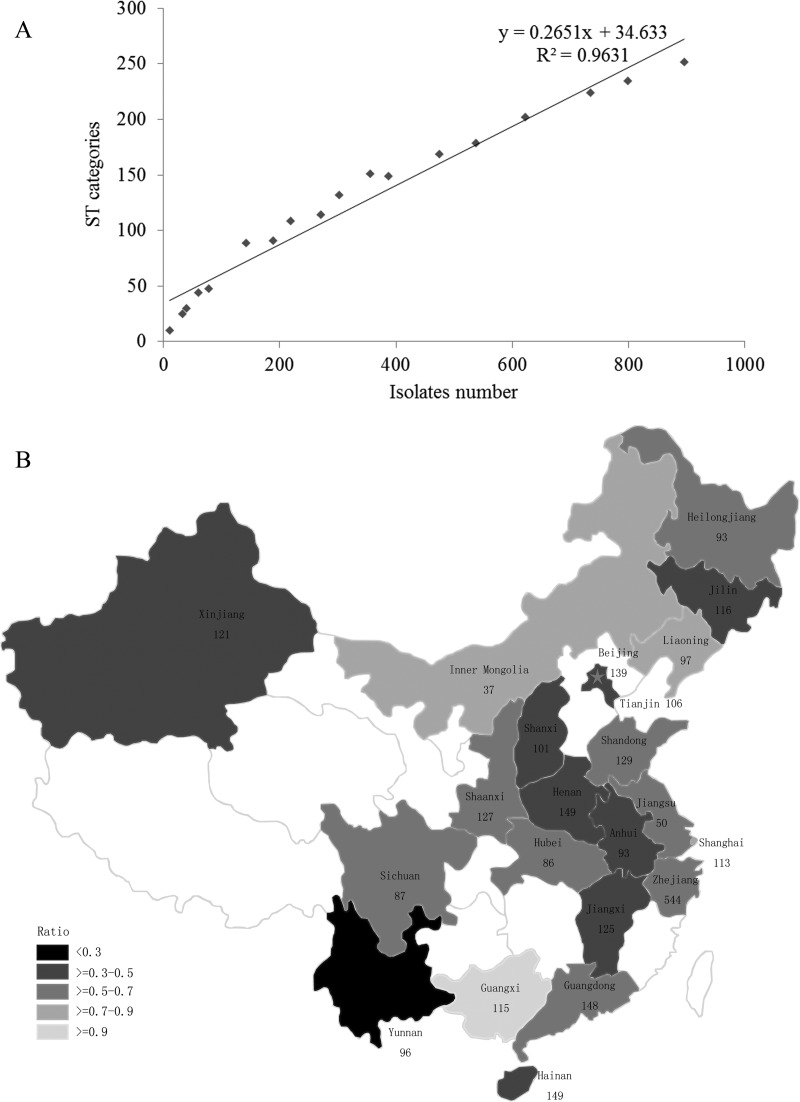

The relatedness between STs and numbers of isolates was evaluated by generating a correlation curve. A marked linear relationship between ST categories and numbers of isolates was observed in the correlation curve (Fig. 2A), which meant that the number of ST categories increased with the addition of isolates. The square of the correlation coefficient was 0.9631, and the slope was 0.2651. The ratio of the number of ST categories to the number of isolates (MLST performed) in every region was calculated (Fig. 2B). Compared with the correlation curve slope, all of the ratios were larger than 0.2651, except that of the Yunnan region, which was 0.2453, indicating a concentrated ST distribution. The reason for this might be that the major isolates in the Yunnan region came from the same hospital. Of the regions with ratios larger than the slope, Guangxi showed the highest ratio at 0.9167. The high ratio of the number of ST categories to the number of isolates in most regions demonstrated that the STs of Chinese drug-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates were diverse. The significant linear relationship between the number of ST categories and the number of isolates revealed that the number of STs of drug-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates was not fixed number but rather increased with the number of isolates. Kidd et al. created a rarefaction curve of the number of unique STs to the number of isolates in their river sample, and it was not saturated either (18).

Fig 2.

(A) Correlation curve showing the relatedness between ST categories and numbers of isolates. (B) Numbers of isolates collected in different regions, making up a total of 2,818 isolates. The star indicates the Beijing region. The ratios of ST categories to numbers of isolates (MLST performed) in the different regions are indicated by the darkness of shading. The darker the shading, the lower the ratio.

In addition, the regional distribution of the top 10 STs revealed the geographic dispersion of STs (Table 1). Five of the top 10 STs were distributed in more than 10 regions, i.e., ST274, ST244, ST235, ST277, and ST357 were found in 16, 13, 11, 10, and 10 regions, respectively. This suggested that they were more common in China. In order to investigate the dominant clone in a P. aeruginosa population, Wiehlmann et al. collected 240 isolates from diverse habitats and geographic regions, which demonstrated 103 clones (15). Of these clones, the 16 most common ones constituted half of the isolates and were also geographically widespread (15). The susceptibility rates of the top 10 STs (Table 1) showed that ST270 had the highest rates of susceptibility to imipenem (85.7%) and meropenem (71.4%), while it had the lowest rate of susceptibility to ceftazidime (14.3%). ST316 had the lowest rates of susceptibility to imipenem (3.3%) and meropenem (10.0%) and a medium level of susceptibility to ceftazidime (30%). Also, the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of the 10 STs did not show a unique pattern of resistance, although their rates of resistance to carbapenems and ceftazidime were high. This also demonstrated the diversity of resistance profiles, and no ST was related to any specific resistance profile.

Table 1.

Isolate numbers, region numbers, and susceptibility rates of 10 primary STs

| ST | Profilea | No. (%) of isolates | No. of regions | Rate of susceptibility (%)b to: |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPM | MEM | FEP | CAZ | PIP | TZP | SCF | ATM | CIP | AMK | GEN | CST | ||||

| 244 | 17-5-12-3-14-4-7 | 68 (7.59) | 13 | 29.4 | 26.5 | 45.6 | 58.8 | 25 | 29.4 | 13.2 | 11.8 | 47.1 | 82.4 | 38.2 | 97.1 |

| 277 | 39-5-9-11-27-5-2 | 60 (6.70) | 10 | 10 | 18.3 | 33.3 | 31.7 | 15 | 18.3 | 11.7 | 11.7 | 33.3 | 93.3 | 53.3 | 98.3 |

| 235 | 38-11-3-13-1-2-4 | 41 (4.58) | 11 | 29.3 | 36.6 | 22 | 46.3 | 4.9 | 26.8 | 7.3 | 14.6 | 7.3 | 51.2 | 14.6 | 97.6 |

| 274 | 23-5-11-7-1-12-7 | 40 (4.46) | 16 | 35 | 50 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 50 | 20 | 20 | 72.5 | 72.5 | 62.5 | 95 |

| 292 | 109-10-73-3-4-4-3 | 34 (3.79) | 6 | 8.8 | 14.7 | 17.6 | 38.2 | 2.9 | 8.8 | 11.8 | 32.4 | 0 | 70.6 | 5.9 | 97.1 |

| 316 | 13-8-9-3-1-6-9 | 30 (3.35) | 6 | 3.3 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 10 | 16.7 | 10 | 10 | 6.7 | 16.7 | 13.3 | 100 |

| 699 | 7-5-7-3-4-1-7 | 23 (2.57) | 4 | 39.1 | 34.8 | 8.7 | 56.5 | 4.3 | 17.4 | 4.3 | 0 | 8.7 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 100 |

| 357 | 2-4-5-3-1-6-11 | 21 (2.34) | 10 | 14.3 | 38.1 | 76.2 | 76.2 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 42.9 | 14.3 | 66.7 | 81 | 47.6 | 100 |

| 270 | 22-3-17-5-2-10-7 | 14 (1.56) | 4 | 85.7 | 71.4 | 21.4 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 28.6 | 21.4 | 7.1 | 71.4 | 85.7 | 21.4 | 92.9 |

| 313 | 47-8-7-6-8-11-40 | 11 (1.23) | 7 | 9.1 | 54.5 | 81.8 | 90.9 | 63.6 | 81.8 | 54.5 | 54.5 | 63.6 | 100 | 72.7 | 100 |

ST profile in the order acsA-aroE-guaA-mutL-nuoD-ppsA-trpE.

Abbreviations: IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; FEP, cefepime; CAZ, ceftazidime; PIP, piperacillin; TZP, tazobactam-piperacillin; SCF, sulbactam-cefoperazone; ATM, aztreonam; CIP, ciprofloxacin; AMK, amikacin; GEN, gentamicin; CST, colistin.

Our work has demonstrated that drug-resistant P. aeruginosa clones can be developed from diverse genetic backgrounds, which is markedly different from other bacteria, such as the multidrug-resistant clonal spread of Acinetobacter baumannii (23). However, further investigation is needed to explore the reason for the clone diversity of drug-resistant P. aeruginosa.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by research grants from the Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China (no. 200802107) and the Science Technology Department of Zhejiang Province (no. 2008C13029-1).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 12 August 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Pagani L, Colinon C, Migliavacca R, Labonia M, Docquier JD, Nucleo E, Spalla M, Li Bergoli M, Rossolini GM. 2005. Nosocomial outbreak caused by multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing IMP-13 metallo-beta-lactamase. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:3824–3828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibson RL, Burns JL, Ramsey BW. 2003. Pathophysiology and management of pulmonary infections in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 168:918–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan NH, Ishii Y, Kimata-Kino N, Esaki H, Nishino T, Nishimura M, Kogure K. 2007. Isolation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from open ocean and comparison with freshwater, clinical, and animal isolates. Microb. Ecol. 53:173–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pirnay JP, Matthijs S, Colak H, Chablain P, Bilocq F, Van Eldere J, De Vos D, Zizi M, Triest L, Cornelis P. 2005. Global Pseudomonas aeruginosa biodiversity as reflected in a Belgian river. Environ. Microbiol. 7:969–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jean SS, Hsueh PR. 2011. High burden of antimicrobial resistance in Asia. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 37:291–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyczak JB, Cannon CL, Pier GB. 2002. Lung infections associated with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:194–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H, Chen M, China Nosocomial Pathogens Resistance Surveillance Study Group 2005. Surveillance for antimicrobial resistance among clinical isolates of gram-negative bacteria from intensive care unit patients in China, 1996 to 2002. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 51:201–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodford N, Turton JF, Livermore DM. 2011. Multiresistant Gram-negative bacteria: the role of high-risk clones in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35:736–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goto H, Shimada K, Ikemoto H, Oguri T, Study Group on Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Pathogens Isolated from Respiratory Infections 2009. Antimicrobial susceptibility of pathogens isolated from more than 10,000 patients with infectious respiratory diseases: a 25-year longitudinal study. J. Infect. Chemother. 15:347–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrow BJ, Pillar CM, Deane J, Sahm DF, Lynch AS, Flamm RK, Peterson J, Davies TA. 2013. Activities of carbapenem and comparator agents against contemporary US Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from the CAPITAL surveillance program. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 75:412–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Empel J, Filczak K, Mrowka A, Hryniewicz W, Livermore DM, Gniadkowski M. 2007. Outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections with PER-1 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase in Warsaw, Poland: further evidence for an international clonal complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:2829–2834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson RK, Minenza N, Nicol M, Bamford C. 2012. VIM-2 metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa causing an outbreak in South Africa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:1797–1798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elias J, Schoen C, Heinze G, Valenza G, Gerharz E, Gerharz H, Vogel U. 2010. Nosocomial outbreak of VIM-2 metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa associated with retrograde urography. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:1494–1500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curran B, Jonas D, Grundmann H, Pitt T, Dowson CG. 2004. Development of a multilocus sequence typing scheme for the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:5644–5649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiehlmann L, Wagner G, Cramer N, Siebert B, Gudowius P, Morales G, Kohler T, van Delden C, Weinel C, Slickers P, Tummler B. 2007. Population structure of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:8101–8106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maatallah M, Cheriaa J, Backhrouf A, Iversen A, Grundmann H, Do T, Lanotte P, Mastouri M, Elghmati MS, Rojo F, Mejdi S, Giske CG. 2011. Population structure of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from five Mediterranean countries: evidence for frequent recombination and epidemic occurrence of CC235. PLoS One 6:e25617. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pirnay JP, Bilocq F, Pot B, Cornelis P, Zizi M, Van Eldere J, Deschaght P, Vaneechoutte M, Jennes S, Pitt T, De Vos D. 2009. Pseudomonas aeruginosa population structure revisited. PLoS One 4:e7740. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kidd TJ, Ritchie SR, Ramsay KA, Grimwood K, Bell SC, Rainey PB. 2012. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exhibits frequent recombination, but only a limited association between genotype and ecological setting. PLoS One 7:e44199. 10.1371/journal.pone.0044199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.CLSI 2012. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-second informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S22 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viedma E, Juan C, Villa J, Barrado L, Orellana MA, Sanz F, Otero JR, Oliver A, Chaves F. 2012. VIM-2-producing multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa ST175 clone, Spain. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18:1235–1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoo JS, Yang JW, Kim HM, Byeon J, Kim HS, Yoo JI, Chung GT, Lee YS. 2012. Dissemination of genetically related IMP-6-producing multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa ST235 in South Korea. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 39:300–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hrabák J, Cervena D, Izdebski R, Duljasz W, Gniadkowski M, Fridrichova M, Urbaskova P, Zemlickova H. 2011. Regional spread of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ST357 producing IMP-7 metallo-beta-lactamase in Central Europe. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:474–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu Y, Zhou J, Zhou H, Yang Q, Wei Z, Yu Y, Li L. 2010. Wide dissemination of OXA-23-producing carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clonal complex 22 in multiple cities of China. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:644–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]