Abstract

Cryptococcus gattii is responsible for an expanding epidemic of serious infections in Western Canada and the Northwestern United States (Pacific Northwest). Some patients with these infections respond poorly to azole antifungals, and high azole MICs have been reported in Pacific Northwest C. gattii. In this study, multiple azoles (but not amphotericin B) had higher MICs for 25 Pacific Northwest C. gattii than for 34 non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii or 20 Cryptococcus neoformans strains. We therefore examined the roles in azole resistance of overexpression of or mutations in the gene (ERG11) encoding the azole target enzyme. ERG11/ACT1 mRNA ratios were higher in C. gattii than in C. neoformans, but these ratios did not differ in Pacific Northwest and non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains, nor did they correlate with fluconazole MICs within any group. Three Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains with low azole MICs and 2 with high azole MICs had deduced Erg11p sequences that differed at one or more positions from that of the fully sequenced Pacific Northwest C. gattii strain R265. However, the azole MICs for conditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae erg11 mutants expressing the 5 variant ERG11s were within 2-fold of the azole MICs for S. cerevisiae expressing the ERG11 gene from C. gattii R265, non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii strain WM276, or C. neoformans strains H99 or JEC21. We conclude that neither ERG11 overexpression nor variations in ERG11 coding sequences was responsible for the high azole MICs observed for the Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains we studied.

INTRODUCTION

Cryptococcus gattii is a basidiomycetous yeast-like fungus that infects both healthy and immunocompromised individuals (1–5). C. gattii infection is usually acquired by inhalation, which can be followed by pneumonia and/or dissemination to the central nervous system (6). C. gattii was once believed to cause serious infections only in tropical or subtropical regions of Africa, Asia, and Australia (4), but an outbreak of 59 human cases of C. gattii infection was recognized on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, in 2002 (5, 7). Since then, many more cases have been documented in the Pacific Northwest (8, 9), including 218 proven or probable cases in British Columbia through 2007 (10) and 83 proven cases in residents of Washington or Oregon between December 2004 and June 2011 (1). The growing importance of C. gattii infections in the northwestern United States is further shown by the fact that the number of cases per year rose each year from 2004 to 2010 (1) and that the overall mortality rate among the northwestern U.S. cases was 33% (1), which is much higher than the 13% mortality rate observed in people with C. gattii infections in Australia from 2000 to 2007 (11).

It was recognized in the 1990s that some patients infected with C. gattii respond slowly or incompletely to antifungal therapy (3, 12), and poor responses to azole therapy have also been observed among C. gattii patients in the northwestern United States (1). Although multiple factors probably contribute to unfavorable responses to therapy, several past studies suggest that resistance to antifungal drugs may play a role. For example, several groups have reported higher MICs of several azole antifungals for C. gattii than for C. neoformans (1, 13), and two recent studies reported higher azole MICs for C. gattii strains with genotypes prevalent in the Pacific Northwest than for C. gattii with other genotypes or C. neoformans (14, 15).

The major mechanisms by which medically important fungi acquire resistance to azole antifungals are (i) overexpression of the ERG11 gene (also known as CYP51) encoding the azole target enzyme lanosterol 14-α demethylase (16, 17), (ii) mutations in ERG11 that result in decreased susceptibility of lanosterol 14-α demethylase (Erg11p) to inhibition by azoles (17–20), and (iii) overexpression of one or more plasma membrane proteins that pump azoles out of the cell (21, 22). Most past studies of azole resistance mechanisms have been in Candida albicans or Aspergillus species, but a few groups have examined potential roles in azole resistance of ERG11 (19, 23, 24) and of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters (25) in C. neoformans. We are not aware that mechanisms of azole resistance have previously been examined in C. gattii isolated from patients in the Pacific Northwest or elsewhere (non-Pacific Northwest). Therefore, the present study compared the MICs of several azole antifungals and the polyene antifungal amphotericin B for 25 C. gattii strains isolated from patients in the Pacific Northwest, 34 C. gattii strains from other geographic regions, and 20 C. neoformans strains. We also examined the role of ERG11 in azole resistance by (i) comparing ERG11 mRNA levels in the C. gattii and C. neoformans strains, (ii) sequencing the ERG11 genes in the 25 Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains, and (iii) comparing the azole MICs of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that expressed wild-type and selected mutant Cryptococcus ERG11 cDNAs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

The tetracycline-repressible erg11 mutant Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain DSY3961 (MATa ura3-52 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 GAL2 CMVp(tetR′-SSN6)::LEU2trp1::Tta ERG11::kanMX-tetO7 pdr5Δ::HIS3kanMX) (18) was obtained from D. Sanglard (University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland), C. albicans SC5314 was obtained from W. Fonzi (Georgetown University), and C. albicans strain 17 (which bears the erg11 R467K mutation and is resistant to fluconazole) (26) was obtained from T. White (University of Missouri, Kansas City, MO). S. cerevisiae DSY3961 transformants were grown on 0.67% yeast nitrogen base supplemented with Complete Supplement Mixture lacking histidine, leucine, and uracil (YNB −His, Leu, Ura) and containing either 2% glucose or both 3% galactose and 2% raffinose, with or without 2 μg doxycycline per ml. C. gattii R265 is a genotype VGIIa strain that was isolated from a patient on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, and C. gattii WM276 is an environmental strain from Australia. These are the two C. gattii strains for which complete genome sequences are available (Cryptococcus gattii Sequencing Project, Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT [http://www.broadinstitute.org/]). The C. gattii and C. neoformans clinical strains were provided by T. Mitchell (Duke University) or K. Datta (Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR [OHSU]), or they were collected by the Division of Infectious Diseases at OHSU. The molecular genotypes of Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains were provided by E. Debess (Oregon Health Division, Portland, OR) or S. Lockhart (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA). As far as we know, all Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains in this study were initial isolates from unique patients in British Columbia, Washington, or Oregon. Cryptococcus strains were grown in YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) with or without fluconazole. Plasmids were amplified in Escherichia coli strain DH5α in Luria-Bertani medium with 100 μg ampicillin per ml.

Antifungal susceptibility testing.

The CLSI M27-A3 broth microdilution method (27) was used to test C. neoformans and C. gattii for susceptibility to fluconazole, voriconazole, itraconazole, posaconazole, and amphotericin B. Due to poor growth of S. cerevisiae in RPMI medium, the CLSI M27-A3 broth microdilution method was modified to test the S. cerevisiae transformants by replacing RPMI medium with YNB plus His plus Leu with or without Ura containing either 2% glucose or 3% galactose and 2% raffinose, with or without doxycycline (2 μg/ml). The 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare MIC values between different groups.

Cloning and expression of ERG11 cDNAs and ORFs.

The synthetic oligonucleotide primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. The ERG11 cDNAs from C. neoformans strains H99 and JEC21 and from C. gattii strains R265 and WM276 were amplified from total RNA by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, and the resulting amplicons were ligated into the BamHI and SalI sites in plasmid YEp51 (28). BamHI- and EcoRI-digested fragments of YEp51 containing the S. cerevisiae GAL10 promoter with or without the Cryptococcus cDNAs of interest were inserted into the low-copy-number, centromere-containing plasmid pRS316 (29). The ERG11 open reading frames (ORFs) from C. albicans strains SC5314 and 17 or from S. cerevisiae DSY3961 were amplified from genomic DNA by PCR; the ERG11 cDNAs from C. gattii strains C3, C16, C17, and C71 were amplified from total RNA by RT-PCR; and the resulting amplicons were ligated into the BamHI and SalI sites of plasmid pRS316 containing the GAL10 promoter (pRS316GAL) and sequenced by standard methods. Proofreading DNA polymerases were used for all PCRs. Plasmids were introduced into S. cerevisiae using the Alkali-Cation Yeast Kit (MP Biomedicals).

Table 1.

Synthetic oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| No. | Primer name | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | S. cerevisiae ERG11-5 | CTTCTTGTCGACATGTCTGCTACCAAGTCAATCGTT |

| 2 | S. cerevisiae ERG11-3 | CTTCTTGGATCCTTAGATCTTTTGTTCTGGATTTCTC |

| 3 | C. albicans ERG11-5 | CTTCTTCTCGAGATGGCTATTGTTGAAACTGTCATTG |

| 4 | C. albicans ERG11-3 | CTTCTTGGATCCTTAAAACATACAAGTTTCTCTTTTTTCCC |

| 5 | Cryptococcus ERG11-5 | GCCACGCTCGAGATGTCGGCAATCATCCCCCA |

| 6 | H99 ERG11-3 | GCCACGGGATCCTCAATTCATACTAAAACTCGCACCATC |

| 7 | JEC21 ERG11-3 | GCCACGGGATCCTCATACCTCCTGCTTGACCTC |

| 8 | R265, WM276 and C71 ERG11-3 | GCCACGGGATCCTTACACCTCCTGCTTGACCTC |

| 9 | ERG11 Northern Probe-5 | AAGGGTAACAACCTTTCTTTG |

| 10 | ERG11 Northern Probe-3 | TGAAGAAATCTTCGCATTCGC |

| 13 | RT-PCR ACT1-5 | CCAAGCAGAACCGAGAGAAGATG |

| 14 | RT-PCR ACT1-3 | GGACAGTGTGGGTGACACCGT |

| 15 | RT-PCR ERG11-5 | CCATGTCCGAGCTCATCATTCTT |

| 16 | RT-PCR ERG11-3 | ACTGGGAAGGGGCAAGTTGG |

ERG11 mRNA levels.

RNA was extracted with the Aurum Total RNA Fatty and Fibrous Tissue Kit (Bio-Rad) from samples grown to mid-log phase in YPD medium. The sizes of the ERG11 mRNAs were estimated by Northern hybridization (30), using a probe generated by (i) amplifying a portion of the C. neoformans H99 ERG11 cDNA by PCR with primers 9 and 10 (Table 1) and (ii) labeling with [α-32P]CTP using the random-primer method. Cryptococcus ERG11 and ACT1 mRNAs were quantified by RT-PCR using primers 13 to 16 (Table 1) and the iScript One-Step RT-PCR Kit with SYBR green (Bio-Rad). The 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare expression levels between populations, and regression analysis was performed to correlate mRNA levels with log2 fluconazole MICs.

ERG11 gene sequences.

Genomic DNAs from 25 Pacific Northwest C. gattii clinical isolates, C. neoformans strains H99 and JEC21, and C. gattii strains R265 and WM276 were isolated using the MasterPure Yeast DNA Purification Kit (Epicentre). The ERG11 coding sequences were amplified from genomic DNA by PCR with primers 5 to 8 (Table 1) and a proofreading DNA polymerase, and the amplicons were sequenced by standard methods. DNA and deduced peptide sequences were aligned using BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor software.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The ERG11 cDNA sequences from C. neoformans H99 and JEC21 and from C. gattii R265 and WM276 have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers JF965441, JF965442, JF965443, and JF965444, respectively.

RESULTS

Susceptibilities of Cryptococcus strains to azoles and amphotericin B.

The geometric mean MICs, MIC50s, and MIC90s of all azole antifungals tested were approximately 2-fold higher for 25 Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains than for 34 non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains or for 20 C. neoformans strains, but there were no significant differences in the MICs of the polyene antifungal amphotericin B for the 3 groups (Table 2). Among all 25 Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains, the log2 MICs of fluconazole correlated with the log2 MICs of voriconazole (slope, 0.67; r = 0.587; P = <0.05), itraconazole (slope, 0.48; r = 0.636; P < 0.001), and posaconazole (slope, 0.40; r = 0.502; P < 0.05), but not with the log2 MICs of amphotericin B (slope, −0.39; r = 0.073; P = 0.73).

Table 2.

Antifungal susceptibilities of C. gattii and C. neoformans

| Drug | Pacific Northwest C. gattii (n = 25) |

Non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii (n = 34) |

C. neoformans (n = 20) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMa | MIC50/MIC90 (μg/ml) | GM | MIC50/MIC90 (μg/ml) | GM | MIC50/MIC90 (μg/ml) | |

| Fluconazole | 20 | 16/64 | 9.9b | 8/32 | 8.6b | 8/32 |

| Voriconazole | 0.53 | 0.5/1 | 0.28b | 0.25/1 | 0.24b | 0.25/0.5 |

| Itraconazole | 0.76 | 1/1 | 0.58b | 0.5/1 | 0.57b | 0.5/2 |

| Posaconazole | 0.95 | 1/2 | 0.48b | 0.5/1 | 0.36b | 0.25/1 |

| Amphotericin B | 0.69 | 0.5/1 | 0.72 | 0.5/1 | 0.68 | 0.5/1 |

GM, geometric mean MIC from at least 3 independent experiments.

P < 0.05 vs. Pacific Northwest C. gattii.

The 25 Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains included 18 genotype VGIIa strains, 3 genotype VGIIc strains, 2 genotype VG1 strains, 1 VGIIb strain, and 1 genotype VGIII strain. Fluconazole MICs ≥32 μg/ml were observed for 5 of 18 strains with genotype VGIIa, 2 of 3 with genotype VGIIc, 1 of 1 with genotype VGIIb, 0 of 2 with genotype VG1, and 0 of 1 with genotype VGIII (Table 3).

Table 3.

Amino acid substitutions encoded by C. gattii or C. neoformans ERG11 cDNAsa

| Strainb | Genotype | Fluconazole MIC (μg/ml) | Q7R | V8A | V15L | Y18F | I19F | H21P | T24A | L30V | I32V | V33A | I37V | F42L | I43V | G45C | H50Q | R57K | R57T | R58K | D59N | D80N | I99L | M101T | I105V | S191P | I196A | S203A | E223V | N249D | R256K | F268L | G293S | V307I | V340I | E349Q | K362R | A404S | A457V | T460S | N533T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R265 | VGIIa | 16 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| WM 276 | VGI | 4 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| H99 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||||||||

| JEC21 | 4 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||

| C1 | VGIIb | 64 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C6 | VGIIa | 64 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C8 | VGIIa | 64 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C71 | VGIIc | 64 | + | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C2 | VGIIa | 32 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C14 | VGIIc | 32 | + | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C59 | VGIIa | 32 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C61 | VGIIa | 32 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C4 | VGIIa | 16 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C5 | VGIIa | 16 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C7 | VGIIa | 16 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C9 | VGIIa | 16 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C11 | VGIIa | 16 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C15 | VGIIc | 16 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C16 | VGI | 16 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C57 | VGIIa | 16 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C60 | VGIIa | 16 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C62 | VGIIa | 16 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C63 | VGIIa | 16 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C66 | VGIIa | 16 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C67 | VGIIa | 16 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C3 | VGIII | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C10 | VGIIa | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C17 | VGI | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C64 | VGIIa | 8 |

+, substitution encoded. Amino acids that differ from C. gattii R265 Erg11p are listed.

All except C. neoformans H99 and JEC21 are C. gattii.

Identification and heterologous expression of C. gattii ERG11.

A search of the genome sequences of C. gattii strains R265 and WM276 identified orthologs of the ERG11 genes of C. neoformans and several other fungi. The corresponding cDNAs were cloned by RT-PCR from total RNA from C. gattii strains R265 and WM276 and from C. neoformans strains H99 and JEC21. The C. gattii R265 cDNA encoded a 550-amino-acid deduced peptide that was 98, 97, and 96% identical, respectively, to the corresponding deduced peptides from C. gattii WM276, C. neoformans H99, and C. neoformans JEC21. To verify that the Cryptococcus cDNAs of interest were derived from full-length mRNAs, Northern blots of total RNAs from the four strains of interest were hybridized with a probe derived from the C. neoformans H99 ERG11 cDNA. All four mRNAs were approximately 1.65 kb in length, as predicted from the corresponding cDNAs (data not shown).

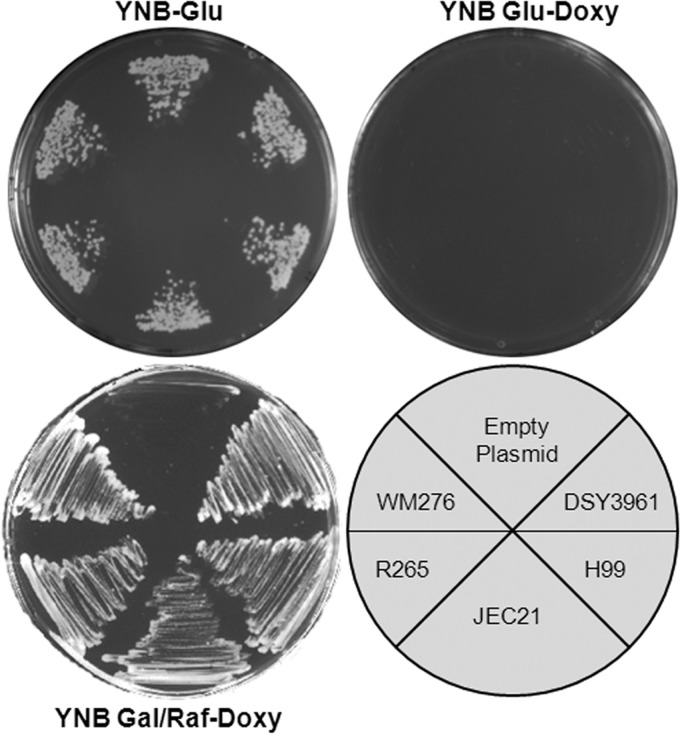

We used the GAL10-regulated expression plasmid pRS316GAL to determine if the Cryptococcus cDNAs of interest would complement S. cerevisiae DSY3961, in which ERG11 expression is tightly repressed by tetracycline. The strain also lacks the PDR5 gene, which makes it highly susceptible to azoles (18). When host cell ERG11 expression was repressed with doxycycline, growth was observed only when heterologous expression of the C. neoformans or C. gattii cDNAs of interest or the S. cerevisiae ERG11 ORF was induced with galactose, but not when expression of the Cryptococcus cDNAs or S. cerevisiae ERG11 was repressed with glucose (Fig. 1). Since these results established that the Cryptococcus cDNAs of interest encode functional Erg11p proteins, the ERG11 cDNA sequences from C. neoformans H99 and JEC21 and from C. gattii R265 and WM276 have been deposited in GenBank.

Fig 1.

Complementation of an S. cerevisiae erg11 mutant. S. cerevisiae DSY3961 cells expressing ERG11 cDNAs from C. neoformans (H99 and JEC21) or C. gattii (R265 or WM276) or ERG11 from S. cerevisiae (DSY3961) under the control of the GAL10 promoter grew well when heterologous ERG11 expression was repressed with 2% glucose (YNB-Glu), did not grow when heterologous ERG11 expression was repressed with 2% glucose and when chromosomal ERG11 expression was repressed with 2 μg/ml doxycycline (YNB Glu-Doxy), and grew well when chromosomal ERG11 expression was repressed with doxycycline and when heterologous ERG11 expression was induced with 3% galactose and 2% raffinose (YNB Gal/Raf-Doxy).

ERG11 mRNA levels.

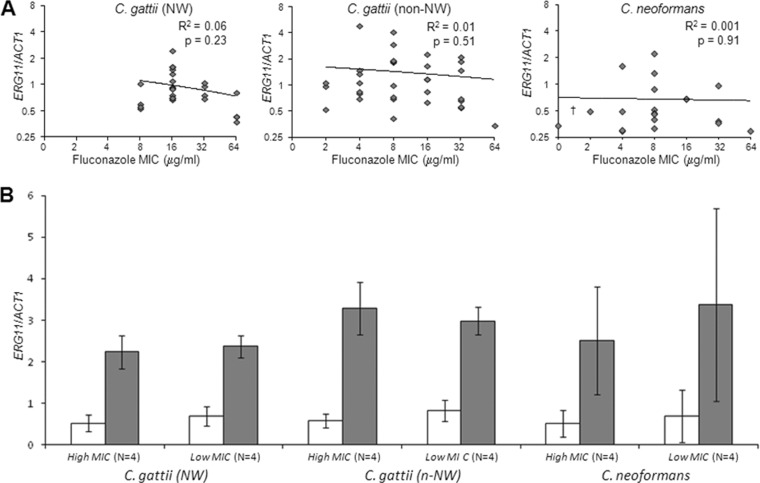

Whether azole resistance was associated with ERG11 overexpression was examined by comparing the ratios of ERG11 mRNA to ACT1 mRNA in the 25 Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains, 34 non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains, and 20 C. neoformans strains, all of which were grown to mid-log phase in liquid YPD medium. The ERG11/ACT1 mRNA ratios (median [interquartile range]) in the 59 Pacific Northwest and non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains (0.94 [0.70 to 1.51]) were higher than in the 20 C. neoformans strains (0.48 [0.36 to 0.74]) (P = 0.0002), but the ERG11/ACT1 mRNA ratios in the Pacific Northwest (0.82 [0.68 to 1.06]) and non-Pacific Northwest (1.09 [0.71 to 1.88]) C. gattii strains were not significantly different (P = 0.08) (data not shown). There also were no significant correlations between ERG11/ACT1 mRNA ratios and fluconazole MICs within any of the 3 groups listed above (Fig. 2A) or within the subsets of Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains with genotype VGIIa (n = 18) or genotypes VGIIa, VGIIb, and VGIIc (n = 22) (data not shown).

Fig 2.

ERG11 expression. (A) ERG11/ACT1 mRNA ratios did not correlate with log2 fluconazole MICs in 25 Pacific Northwest C. gattii, 34 non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii, and 20 C. neoformans clinical isolates. (B) The ERG11/ACT1 mRNA ratios were higher when 4 strains with the highest and the 4 strains of Pacific Northwest C. gattii, non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii, or C. neoformans with the lowest fluconazole MICs were incubated in the presence of 8 μg/ml fluconazole for 2 h (gray bars) than in cells incubated in the absence of fluconazole (white bars), but there were no significant differences in ERG11/ACT1 mRNA ratios between the 3 groups or between the 4 strains with the high and low fluconazole MICs within each group. Shown are geometric means ± standard deviations from 3 experiments.

Whether ERG11 expression was induced by fluconazole exposure was examined by measuring the ratios of ERG11 mRNA to ACT1 mRNA when 8 strains each of Pacific Northwest C. gattii, non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii, and C. neoformans (4 with the highest and 4 with the lowest fluconazole MICs) were exposed to fluconazole. The ERG11/ACT1 mRNA ratios rose in all strains tested following exposure to 8 μg fluconazole per ml for 2 h, and the magnitudes of ERG11 induction did not differ significantly between the 3 groups of Cryptococcus strains or between the 4 strains within each group with the highest and lowest fluconazole MICs (Fig. 2B). Similar responses were observed when the Cryptococcus strains were exposed to 0.5 times each strain's fluconazole MIC for 2 h or 100 h (data not shown).

C. gattii ERG11 sequences.

Since azole resistance was not associated with ERG11 overexpression in the Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains we studied, we next examined whether azole resistance was associated with variations in Erg11p peptide sequences. We therefore (i) sequenced the ERG11 genes in C. gattii strain R265, C. gattii strain WM276, and the 25 Pacific Northwest C. gattii clinical strains; (ii) aligned the C. gattii R265 and WM276 ERG11 genes and cDNAs to identify the coding sequences; and (iii) deduced each strain's Erg11p peptide sequence. The deduced Erg11p sequences from C. gattii strains R265 and WM276 differed at 9 positions. Seven of these 9 varying amino acids in C. gattii R265 Erg11p and 4 of the 9 varying amino acids in C. gattii WM276 Erg11p were also present in the deduced Erg11p proteins of C. neoformans H99 and/or JEC21 (Table 3).

The deduced Erg11p sequences of 20 Pacific Northwest C. gattii clinical isolates (including all 18 VGIIa strains, the single VGIIb strain, and 1 of 3 VGIIc strains) were identical to that of C. gattii R265, and these 20 strains' fluconazole MICs ranged from 8 to 64 μg/ml. In contrast, the deduced Erg11p sequences of 5 Pacific Northwest C. gattii clinical isolates (both VG1 strains, 2 of 3 VGIIc strains, and the single VGIII strain) differed from that of C. gattii R265 at one or more positions. Three of these 5 strains (2 VGI and 1 VGIII) had low fluconazole MICs (8 to 16 μg/ml), and all of these 3 strains' deduced Erg11p sequences differed from that of C. gattii R265 at multiple positions, many of which (H21P, H50Q, R57K, R58K, and I196A) were also present in the deduced Erg11p sequences of C. neoformans H99, C. neoformans JEC21, and/or C. gattii WM276. In contrast, 2 VGIIc strains had high fluconazole MICs (32 to 64 μg/ml), and these strains' deduced Erg11p sequences contained a single amino acid substitution (N249D) that was not present in the deduced Erg11p sequence of any other C. gattii strain or in C. neoformans H99 or JEC21 (Table 3).

Azole inhibition of recombinant fungal Erg11p proteins.

To determine if any of the observed differences in Erg11p sequences was responsible for differences in azole MICs, we used plasmid pRS316GAL to express Cryptococcus cDNAs of interest in S. cerevisiae DSY3961, and we measured the resulting transformants' azole MICs. To verify that this heterologous expression system could be used for this purpose, we compared the azole MICs of S. cerevisiae DSY3961 cells that expressed wild-type C. albicans ERG11 or a mutant allele that encodes an amino acid substitution (R467K) that has been shown to increase the fluconazole MIC by 4-fold (31). When chromosomal ERG11 expression was repressed with doxycycline and heterologous ERG11 expression was induced with galactose, the fluconazole MIC was 4-fold higher in S. cerevisiae transformants expressing the C. albicans ERG11(R467K) allele than in controls expressing wild-type C. albicans ERG11.

The MICs of all azoles tested for S. cerevisiae expressing the ERG11 cDNAs from C. neoformans H99 or JEC21 did not differ significantly from those for S. cerevisiae expressing the ERG11 cDNAs from C. gattii R265 or WM276. The azole MICs for S. cerevisiae expressing the C. gattii R265 ERG11 cDNA were approximately 2-fold higher than the MICs for S. cerevisiae expressing the C. gattii WM276 ERG11 cDNA. However, the azole MICs for S. cerevisiae expressing cDNAs encoding all of the variant Erg11p sequences observed in this study differed very little from the azole MICs for S. cerevisiae expressing wild-type C. gattii R265 ERG11 cDNA. Moreover, none of the S. cerevisiae transformants expressing a variant ERG11 cDNA had a higher MIC of any azole than did S. cerevisiae expressing the ERG11 cDNA from C. gattii R265. Lastly, the MICs of the polyene antibiotic amphotericin B were the same for all of the S. cerevisiae transformants we examined (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effects of heterologous ERG11 expression on susceptibility of S. cerevisiae DSY3961 to antifungals

| Source of ERG11 | Geometric mean of the MIC (μg/ml)a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluconazole | Voriconazole | Itraconazole | Posaconazole | Amphotericin B | |

| Empty plasmidb | 1 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.128 | 2 |

| S. cerevisiae DSY3961 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 |

| C. albicans SC5314 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 2 |

| C. albicans 17 (R467K) | 32 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 2 |

| C. neoformans H99 | 0.250 | 0.002 | 0.031 | 0.063 | 2 |

| C. neoformans JEC21 | 0.125 | 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.063 | 2 |

| C. gattii R265 | 0.250 | 0.002 | 0.036 | 0.055 | 2 |

| C. gattii WM276 | 0.149 | 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.031 | 2 |

| C. gattii C71 (N249D) | 0.250 | 0.002 | 0.015 | 0.041 | 2 |

| C. gattii C3 | 0.177 | 0.002 | 0.015 | 0.026 | 2 |

| C. gattii C16 | 0.210 | 0.001 | 0.018 | 0.031 | 2 |

| C. gattii C17 | 0.149 | 0.002 | 0.015 | 0.024 | 2 |

MICs were measured in YNB − His, Leu, Ura containing 3% galactose, 2% raffinose, and 2 μg doxycycline/ml. n = 3 or more for all azoles; n = 2 for amphotericin B.

Empty-plasmid controls were tested without doxycycline.

DISCUSSION

The goals of the present study were (i) to compare the MICs of multiple azoles and of amphotericin B for 25 Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains, 34 non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains, and 20 C. neoformans strains and (ii) to determine if either ERG11 overexpression or mutations in the ERG11 coding sequences was associated with high azole MICs in the Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains. We found that the MICs of multiple azole antifungals for 25 Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains were approximately 2-fold-higher than for the 34 non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains or the 20 C. neoformans strains. Also, 8 of 25 (32%) Pacific Northwest C. gatti strains had fluconazole MICs of ≥32 μg/ml. Other groups have reported higher azole MICs for C. gattii than for C. neoformans (13, 32) and also higher azole MICs for C. gattii with molecular genotypes that are common in the Pacific Northwest than for C. gattii with other genotypes (14, 15), but we are unaware of prior studies that directly compared the azole MICs for C. gattii strains isolated from people infected in the Pacific Northwest to those for strains isolated elsewhere. Whether the higher azole MICs we observed for Pacific Northwest C. gattii than for non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii or C. neoformans play a causal role in clinical outcomes is not known, but the high azole MICs that we or others (14, 15) have found for Pacific Northwest C. gattii correlate with poor outcomes and high mortality rates in people with Pacific Northwest C. gattii infections (1). Lastly, our observation that high fluconazole MICs among Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains correlated with high MICs of other azoles suggests that using voriconazole, itraconazole, or posaconazole instead of fluconazole is unlikely to overcome the problem of azole resistance.

Since Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains were more resistant to multiple azoles than were other C. gattii strains or C. neoformans, we next examined whether ERG11 overexpression was associated with azole resistance. The first step was to identify C. gattii ERG11, which was done by searching the C. gattii R265 and WM276 genome databases for orthologs of known fungal ERG11 genes and then by showing that these genes' cDNAs complemented the conditional erg11 mutation in S. cerevisiae DSY3961. When we tested the strains of interest for ERG11 overexpression, the mean ratios of ERG11 mRNA to ACT1 mRNA were higher in C. gattii than in C. neoformans. However, the mean ERG11 mRNA levels did not differ between the Pacific Northwest and non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains, nor did they correlate with fluconazole MICs within any group. Also, ERG11 mRNA levels did not differ significantly when the Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains with the highest and lowest fluconazole MICs were exposed to fluconazole. ERG11 overexpression is known to cause azole resistance in C. albicans (24), but not in C. neoformans (20). These results indicated that overexpression of ERG11 was not responsible for azole resistance in the Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains we studied.

When we analyzed the 25 Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains' deduced Erg11p sequences, we found that variations in these proteins' sequences correlated better with the strains' molecular genotypes than with their azole MICs. For example, 18 of 18 genotype VGIIa, 1 of 1 VGIIb, and 1 of 3 VGIIc clinical isolates had deduced Erg11p sequences that were identical to that of VGIIa strain C. gattii R265, and these 20 strains' fluconazole MICs varied widely from 8 to 64 μg/ml. In contrast, 2 of 3 VGIIc, 1 of 1 VGIII, and 2 of 2 VGI strains had deduced Erg11p sequences that differed at one or more positions from that of C. gattii R265. Three of these strains had low fluconazole MICs, and multiple amino acid substitutions observed in these strains were also found in the deduced Erg11p sequences of the fluconazole-susceptible genotype I C. gattii strain WM276, C. neoformans H99, and C. neoformans JEC21 (33). The one finding that suggested a link between azole resistance and sequence variations in Erg11p was that 2 genotype VGIIc C. gattii strains with high fluconazole MICs had a single amino acid substitution (N249D) that was not observed in any other strain in this study and also had not been described previously. Notably, none of the Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains in this study had any of the Erg11p amino acid substitutions that had previously been described in azole-resistant C. albicans or C. neoformans (20, 24).

We used the tetracycline-repressible erg11 mutant S. cerevisiae DSY3961 to compare the azole MICs of transformants expressing the C. neoformans and C. gattii ERG11 cDNAs observed in this study. This heterologous expression system was similar to the system used by Alcazar-Fuoli et al. (18) to study the effects of specific amino acid substitutions on azole susceptibility in C. albicans Erg11p, except that we used a centromere-containing plasmid that replicates at a low copy number per cell instead of 2μ-containing plasmids to minimize the effects of variable plasmid copy numbers on azole MICs. We verified that this method can be used for this purpose by confirming the earlier observation that S. cerevisiae cells expressing the C. albicans ERG11(R467K) allele had 4-fold-higher fluconazole MICs than controls expressing wild-type C. albicans ERG11 (30). The higher azole MICs we observed for S. cerevisiae DSY3961 cells expressing the ERG11 genes from S. cerevisiae or C. albicans under the control of the S. cerevisiae GAL10 promoter than for empty-vector controls incubated without tetracycline were not surprising because ERG11 overexpression is a known cause of azole resistance (16, 17). The lower azole MICs observed for S. cerevisiae DSY3961 cells expressing C. neoformans or C. gattii ERG11 cDNAs were likely due to differences in codon usage, translational efficiency, and/or mRNA stability when basidiomycete ERG11 cDNAs were expressed in an ascomycete host. We did not examine these possibilities experimentally because the objective of these studies was to compare the effects on azole MICs of specific amino acid substitutions in the Erg11p proteins of closely related fungi.

When S. cerevisiae DSY3961 cells expressing the ERG11 cDNAs from 2 wild-type strains each of C. gattii and C. neoformans were tested for susceptibility to multiple azoles, we found no significant differences between the cDNAs derived from C. gattii and C. neoformans. The MICs of multiple azoles were approximately 2-fold higher in S. cerevisiae expressing the ERG11 cDNA from Pacific Northwest C. gattii strain R265 than in S. cerevisiae expressing the ERG11 cDNA from non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii strain WM276, which corresponded to our observation that the MICs of several azoles for 25 Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains were approximately 2-fold higher than those for 34 non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains. However, we observed only minor differences in azole MICs when the ERG11 cDNAs encoding all of the variant Erg11p sequences observed in this study were expressed in S. cerevisiae, and no transformant expressing a variant ERG11 cDNA had a higher MIC of any azole than did S. cerevisiae expressing the ERG11 cDNA from C. gattii R265. We concluded from these observations that the marked differences in azole MICs observed in the 25 Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains we studied cannot be explained either by inherent resistance of Pacific Northwest C. gattii's Erg11p to inhibition by azoles or by the presence of any of the single or multiple Erg11p amino acid substitutions observed in this study.

In summary, we have shown that the MICs of multiple azole antifungals for 25 Pacific Northwest C. gattii clinical isolates were higher than those for 34 non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii or 20 C. neoformans isolates. Among these C. gattii and C. neoformans isolates, high azole MICs were not associated with ERG11 mRNA levels in either the presence or absence of fluconazole induction. We also found that (i) C. gattii Erg11p was no more resistant to inhibition by azoles than was C. neoformans Erg11p, (ii) the Erg11p of Pacific Northwest C. gattii R265 was no more than 2.4-fold more resistant to inhibition by any azole tested than was Erg11p from non-Pacific Northwest C. gattii WM276, and (iii) the amino acid substitutions observed in the deduced Erg11p sequences of 5 Pacific Northwest C. gattii strains were not associated with differences in the susceptibilities of these proteins to inhibition by azoles. Since these results imply that ERG11 does not play a significant role in azole resistance in Pacific Northwest C. gattii, the focus of our ongoing studies of mechanisms of azole resistance in Pacific Northwest C. gattii is the identification and characterization of plasma membrane azole efflux pumps. Plasma membrane azole efflux pumps are known to cause azole resistance in C. albicans, C. neoformans, and other fungi (21, 22, 25), but they have not yet been studied in C. gattii.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Emlio DeBesse and Shawn R. Lockhart for genotyping Pacific Northwest C. gattii clinical isolate strains.

This work was supported by NIH U54 AI-811680 and by a presidential grant from OHSU.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 26 August 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Harris JR, Lockhart SR, Debess E, Marsden-Haug N, Goldoft M, Wohrle R, Lee S, Smelser C, Park B, Chiller T. 2011. Cryptococcus gattii in the United States: clinical aspects of infection with an emerging pathogen. Clin. Infect. Dis. 53:1188–1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2010. Emergence of Cryptococcus gattii—Pacific Northwest, 2004–2010. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 59:865–868 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Speed B, Dunt D. 1995. Clinical and host differences between infections with the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin. Infect. Dis. 21:28–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorrell TC. 2001. Cryptococcus neoformans variety gattii. Med. Mycol. 39:155–168 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Upton A, Fraser JA, Kidd SE, Bretz C, Bartlett KH, Heitman J, Marr KA. 2007. First contemporary case of human infection with Cryptococcus gattii in Puget Sound: evidence for spread of the Vancouver Island outbreak. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:3086–3088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bovers M, Hagen F, Boekhout T. 2008. Diversity of the Cryptococcus neoformans-Cryptococcus gattii species complex. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 25:S4–S12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoang LM, Maguire JA, Doyle P, Fyfe M, Roscoe DL. 2004. Cryptococcus neoformans infections at Vancouver Hospital and Health Sciences Centre (1997–2002): epidemiology, microbiology and histopathology. J. Med. Microbiol. 53:935–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Datta K, Bartlett KH, Baer R, Byrnes E, Galanis E, Heitman J, Hoang L, Leslie MJ, MacDougall L, Magill SS, Morshed MG, Marr KA. 2009. Spread of Cryptococcus gattii into Pacific Northwest region of the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:1185–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byrnes EJ, Bildfell RJ, Frank SA, Mitchell TG, Marr KA, Heitman J. 2009. Molecular evidence that the range of the Vancouver Island outbreak of Cryptococcus gattii infection has expanded into the Pacific Northwest in the United States. J. Infect. Dis. 199:1081–1086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galanis E, Macdougall L. 2010. Epidemiology of Cryptococcus gattii, British Columbia, Canada, 1999–2007. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:251–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen SC, Slavin MA, Heath CH, Playford EG, Byth K, Marriott D, Kidd SE, Bak N, Currie B, Hajkowicz K, Korman TM, McBride WJ, Meyer W, Murray R, Sorrell TC. 2012. Clinical manifestations of Cryptococcus gattii infection: determinants of neurological sequelae and death. Clin. Infect. Dis. 55:789–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell DH, Sorrell TC, Allworth AM, Heath CH, McGregor AR, Papanaoum K, Richards MJ, Gottlieb T. 1995. Cryptococcal disease of the CNS in immunocompetent hosts: influence of cryptococcal variety on clinical manifestations and outcome. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:611–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez-Lopez A, Zaragoza O, Dos Anjos Martins M, Melhem MC, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Cuenca-Estrella M. 2008. In vitro susceptibility of Cryptococcus gattii clinical isolates. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14:727–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lockhart SR, Iqbal N, Bolden CB, DeBess EE, Marsden-Haug N, Worhle R, Thakur R, Harris JR. 2012. Epidemiologic cutoff values for triazole drugs in Cryptococcus gattii: correlation of molecular type and in vitro susceptibility. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 73:144–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iqbal N, DeBess EE, Wohrle R, Sun B, Nett RJ, Ahlquist AM, Chiller T, Lockhart SR. 2010. Correlation of genotype and in vitro susceptibilities of Cryptococcus gattii strains from the Pacific Northwest of the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:539–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albertson GD, Niimi M, Cannon RD, Jenkinson HF. 1996. Multiple efflux mechanisms are involved in Candida albicans fluconazole resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2835–2841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franz R, Kelly S, Lamb D, Kelly D, Ruhnke M, Morschhäuser J. 1998. Multiple molecular mechanisms contribute to a stepwise development of fluconazole resistance in clinical Candida albicans strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:3065–3072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alcazar-Fuoli L, Mellado E, Cuenca-Estrella M, Sanglard D. 2011. Probing the role of point mutations in the cyp51A gene from Aspergillus fumigatus in the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Med. Mycol. 49:276–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodero L, Mellado E, Rodriguez AC, Salve A, Guelfand L, Cahn P, Cuenca-Estrella M, Davel G, Rodriguez-Tudela JL. 2003. G484S amino acid substitution in lanosterol 14-alpha demethylase (ERG11) is related to fluconazole resistance in a recurrent Cryptococcus neoformans clinical isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3653–3656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sionov E, Chang YC, Garraffo HM, Dolan MA, Ghannoum MA, Kwon-Chung KJ. 2012. Identification of a Cryptococcus neoformans cytochrome P450 lanosterol 14α-demethylase (Erg11) residue critical for differential susceptibility between fluconazole/voriconazole and itraconazole/posaconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:1162–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cannon RD, Lamping E, Holmes AR, Niimi K, Baret PV, Keniya MV, Tanabe K, Niimi M, Goffeau A, Monk BC. 2009. Efflux-mediated antifungal drug resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 22: 291–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basso LR, Gast CE, Mao Y, Wong B. 2010. Fluconazole transport into Candida albicans secretory vesicles by the membrane proteins Cdr1p, Cdr2p, and Mdr1p. Eukaryot. Cell 9:960–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sionov E, Lee H, Chang YC, Kwon-Chung KJ. 2010. Cryptococcus neoformans overcomes stress of azole drugs by formation of disomy in specific multiple chromosomes. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000848. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morschhäuser J. 2002. The genetic basis of fluconazole resistance development in Candida albicans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1587:240–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B, La Sorda M, Torelli R, Fiori B, Santangelo R, Delogu G, Fadda G. 2006. Role of AFR1, an ABC transporter-encoding gene, in the in vivo response to fluconazole and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 74:1352–1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White TC. 1997. The presence of an R467K amino acid substitution and loss of allelic variation correlate with an azole-resistant lanosterol 14alpha demethylase in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1488–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2008. M27-A3 reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts: approved standard, 3rd ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inouye M. 1983. Experimental manipulation of gene expression. Academic Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sikorski RS, Hieter P. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122:19–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kayingo G, Martins A, Andrie R, Neves L, Lucas C, Wong B. 2009. A permease encoded by STL1 is required for active glycerol uptake by Candida albicans. Microbiology 155:1547–1557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanglard D, Ischer F, Koymans L, Bille J. 1998. Amino acid substitutions in the cytochrome P-450 lanosterol 14alpha-demethylase (CYP51A1) from azole-resistant Candida albicans clinical isolates contribute to resistance to azole antifungal agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:241–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torres-Rodríguez JM, Alvarado-Ramírez E, Murciano F, Sellart M. 2008. MICs and minimum fungicidal concentrations of posaconazole, voriconazole and fluconazole for Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:205–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Revankar SG, Fu J, Rinaldi MG, Kelly SL, Kelly DE, Lamb DC, Keller SM, Wickes BL. 2004. Cloning and characterization of the lanosterol 14alpha-demethylase (ERG11) gene in Cryptococcus neoformans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 324:719–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]