Abstract

Objective To evaluate the effect of intrathecal therapy with human antitetanus immunoglobulin on clinical progression of and mortality from tetanus.

Design Randomised controlled trial.

Setting Intensive care unit of a university hospital, Pernambuco, Brazil.

Participants 120 patients with tetanus allocated to antitetanus immunoglobulin by either the intrathecal and intramuscular route (n = 58) or the intramuscular route (n = 62; control group).

Main outcome measures Clinical progression of disease, duration of hospital stay, duration of occurrence of spasms, complications, respiratory infection, respiratory failure or mechanical ventilation, duration of respiratory assistance, and mortality.

Results Patients in the treatment group showed a better clinical progression than those in the control group (χ2 for trend 7.752, P = 0.005; difference in proportion of patients with improvement 20%, 95% confidence interval 4% to 35%). The duration of occurrence of spasms, hospital stay, and respiratory assistance were all shorter in patients the treatment group: respectively, 14.96, 0.0001 (difference in proportion of patients with spasms lasting ≤ 10 days 36%, 18% to 55%); 4.56, 0.03; and 6.56, 0.01 (proportion of patients who needed assistance for ≤ 10 days 69.2% in the treatment group and 30.8% in the control group (difference 38%, 12% to 65%)).

Conclusion Patients treated with antitetanus immunoglobulin by the intrathecal route show better clinical progression than those treated by the intramuscular route.

Introduction

Tetanus is a universal public health problem, with around one million cases a year and a mortality between 6% and 60%.1 Over the past 30 years only nine randomised controlled trials have studied the prevention and treatment of tetanus.2 Recent advances in treating tetanus are ascribed to the more frequent and effective use of aggressive treatments that utilise tracheotomy, artificial paralysis, and artificial respiration.2-4

Treating tetanus by neutralising the toxin is still controversial, especially dosage and route of administration.5-15 A meta-analysis of intrathecal therapy was inconclusive in adults.16 We evaluated the effect of such therapy on clinical progression of and mortality from tetanus.

Methods

Our study sample was patients with tetanus admitted to the intensive care unit of the Oswaldo Cruz University Hospital, Recife, Brazil. Potential participants were aged 12 or more and had secondary sex characteristics. They were randomised to receive antitetanus immunoglobulin by either the intrathecal and intramuscular routes (treatment group) or the intramuscular route (control group).

Sample size calculations

Our sample size was based on two outcomes: disease progression and mortality.17 Clinical progression was based on the study by Gupta and coworkers, where 6% of patients worsened after treatment compared with 21% in the control group.7 Assuming an α of 5% and a β of 20% (80% power), we needed 112 patients, 56 in each group.

In the past 15 years, mortality from tetanus at our hospital has been up to 35%.18 Taking previous studies as reference, we estimated a reduction in mortality to 18%.5,7,8 Assuming an α of 5% and a β of 40% (60% power), we needed 132 patients, 66 in each group.

Data collection

After obtaining written informed consent, we randomised participants to either the treatment group or the control group. Randomisation was based on blocks of 20, and treatment allocation was concealed in sealed envelopes. We classified tetanus as grade 1, trismus, dysphagia, and generalised rigidity with no spasms; grade 2, mild and occasional spasms; grade 3, severe and recurrent spasms—usually triggered by minor or imperceptible stimuli; and grade 4, features of grade 3 and overactivity of the sympathetic nervous system.19 Meetings were held weekly to discuss and verify these criteria. The grade was recorded on admission.20,21 Using a standardised form we collected data on clinical progression and outcome of each case, as well as re-evaluations as outpatients. The occurrence of spasms was recorded daily on another form.

Although blinding effectively minimises bias, placebo would be unethical in our study. We therefore used several approaches to minimise observation bias: the doctors who classified the disease were rotated on alternate days for 10 days after patients were admitted; the clinical stage was recorded on a form devoid of information on treatment or previous classifications; treatment allocation was known only by certain members of the research team; and regular meetings were held to discuss problems.

For intrathecal therapy, we used 1000 IU of a lyophilised human immunoglobulin, free of preservatives to avoid irritating the meninges and the need for corticosteroids. The immunoglobulin was diluted in distilled water to a volume of 4 ml, injected by lumbar, or preferably suboccipital, puncture after removal of the corresponding volume of cerebrospinal fluid. Both groups received 3000 IU of immunoglobulin with preservative by the intramuscular route. All patients were treated according to the standardised protocol.

Data processing and analysis

We used EPI INFO 6.0 for analyses and we made double entries. The frequency of each outcome was compared by χ2 test or relative risks with 95% confidence intervals. For ordered categories we used the χ2 test for linear trend. The t test was used for mean comparisons. Participants who failed to undergo the therapeutic procedure were analysed according to the group to which they were allocated.

Results

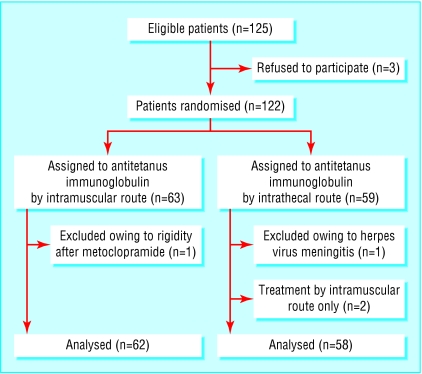

From July 1997 to July 2001 we recruited 120 patients; 58 were allocated to the treatment group and 62 to the control group (figure). Potential confounders were similarly distributed between the groups (table 1).

Figure 1.

Trial profile

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients treated for tetanus by the intramuscular route (control group) or intrathecal route

| Characteristic | No (%) in control group (n=62) | No (%) in study group (n=58) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 52 (84) | 53 (91) |

| Age (years): | ||

| 12-30 | 21 (34) | 14 (24) |

| 31-50 | 18 (29) | 24 (41) |

| 51-70 | 18 (29) | 13 (22) |

| >70 | 5 (8) | 7 (12) |

| Incubation period (days)*: | ||

| ≤10 | 32 (52) | 38 (66) |

| >10 | 21 (34) | 18 (31) |

| Unknown | 9 (15) | 2 (3) |

| Period of onset (hours)*: | ||

| ≤48 | 30 (48) | 30 (52) |

| >48 | 24 (39) | 18 (31) |

| Unknown | 1 (2) | 2 (3) |

| With no progression to spasms | 7 (11) | 8 (14) |

| Time between start of symptoms and admission (hours)*: | ||

| ≤36 | 15 (24) | 18 (32) |

| >36 | 47 (76) | 39 (68) |

| Prognostic classification†: | ||

| 1A | 7 (11) | 9 (12) |

| 2A | 23 (37) | 20 (35) |

| 3A | 32 (52) | 29 (50) |

| Clinical grade on admission: | ||

| I | 24 (39) | 21 (36) |

| II | 23 (37) | 23 (40) |

| III | 15 (24) | 13 (22) |

| IV | — | 1 (2) |

Three patients refused to participate. They were treated in accordance with normal routine and were eventually discharged from hospital. In two patients it proved technically difficult to achieve suboccipital or lumbar puncture; they received treatment by the intramuscular route only, but for analyses they were considered in the intrathecal group. We excluded one patient randomised to each group owing to misclassification of diagnosis: one had herpes virus meningitis and the other muscular rigidity due to metoclopramide.

The treatment group showed better clinical progression than the control group (χ2 for trend 7.82, P = 0.0052; table 2). Most of the participants were classified with either grade I or II disease. Up to 10 days after admission most patients in the treatment group had grade I or II disease and most patients in the control group had grade III or IV disease (table 3).

Table 2.

Clinical progression of patients treated for tetanus by the intramuscular route (control group) or intrathecal route

| Clinical progression | No (%) in control group (n=60) | No (%) in study (n=58) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improvement

|

10 (17)

|

21 (36)

|

χ2=7.752;0.005 |

| Stabilisation and improvement

|

13 (22)

|

15 (26)

|

|

| Deterioration† | 37 (62) | 22 (38) |

χ2 for linear trend.

Smaller risk of deterioration or death within first 10 days in study group (relative risk 0.6, 95% confidence interval 0.4 to 0.9).

Table 3.

Severity of tetanus within 10 days of admission. Values are numbers (percentages) of patients

|

Grade of tetanus

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days after admission | I | II | III | IV |

| Day 2: | ||||

| Control | 15 (27) | 13 (24) | 19 (35) | 8 (15) |

| Study | 20 (36) | 22 (39) | 13 (23) | 1 (2) |

| Day 4: | ||||

| Control | 10 (19) | 13 (25) | 20 (38) | 10 (19) |

| Study | 19 (36) | 23 (43) | 9 (17) | 2 (4) |

| Day 6: | ||||

| Control | 11 (21) | 12 (23) | 17 (33) | 12 (23) |

| Study | 18 (39) | 21 (46) | 7 (15) | — |

| Day 8: | ||||

| Control | 9 (18) | 16 (31) | 17 (33) | 9 (18) |

| Study | 23 (52) | 16 (36) | 05 (11) | — |

| Day 10: | ||||

| Control | 9 (21) | 11 (26) | 17 (40) | 6 (14) |

| Study | 22 (56) | 10 (26) | 5 (13) | 2 (5) |

82 patients were evaluated on day 10, 20 had been discharged, seven had died, and 11 missed appointments.

We excluded 23 patients on the basis of spasms: 17 had none during hospital stay, five died during the period that spasms occurred, and in one the record of daily spasms was mislaid. The study group had shorter duration of occurrence of spasms (χ2 for trend 14.96, P = 0.0001; table 4). Among the 106 patients who survived, duration of hospital stay varied from 2 to 80 days. The treatment group had a shorter duration of hospital stay (4.56, 0.03; table 4); a smaller proportion had complications during this time, although the difference was not significant (P = 0.071; table 5).

Table 4.

Duration of occurrence of spasms and hospital stay and need for respiratory assistance in patients treated for tetanus by the intramuscular route (control group) or intrathecal route

| Duration (days) of outcome | Control group | Study group | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permanence of spasms: | n=51 | n=46 | |

| ≤10

|

14 (32)

|

30 (68)

|

14.96;0.0001† |

| 11-20

|

18 (62)

|

11 (38)

|

|

| >20 | 19 (80) | 5 (21) | |

| Hospital stay: | n=52 | n=54 | |

| ≤15

|

14 (27)

|

23 (43)

|

4.56;0.03‡ |

| 16-30

|

17 (33)

|

19 (35)

|

|

| >30 | 21 (40) | 12 (22) | |

| Respiratory assistance: | n=30 | n=20 | |

| ≤10

|

4 (31)

|

9 (70)

|

6.56;0.01§ |

| 11-20

|

12 (63)

|

7 (37)

|

|

| >20 | 14 (78) | 4 (22) |

χ2 for linear trend.

P=0.001 (t test).

P=0.13 (t test).

P=0.01 (t test).

Table 5.

Complications and mortality in patients treated for tetanus by the intramuscular route (control group) or intrathecal route

| Outcome | Control group (n=62) | Study group (n=58) | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications

|

46 (74)

|

33 (57)

|

1.30 (1.00 to 1.70) | 0.071 |

| No complications | 16 (26) | 25 (43) | ||

| Respiratory infection

|

42 (68)

|

29 (50)

|

1.35 (0.99 to 1.85) | 0.073 |

| No respiratory infection | 20 (32) | 29 (50) | ||

| Respiratory failure or mechanical ventilation

|

34 (55)

|

22 (38)

|

1.45 (0.97 to 2.16) | 0.094 |

| No respiratory failure or mechanical ventilation | 28 (45) | 36 (62) | ||

| Died

|

10 (16)

|

4 (7)

|

2.34 (0.78 to 7.05) | 0.197 |

| Did not die | 52 (84) | 54 (93) |

Respiratory infection was the most common complication. It occurred less frequently in the treatment group, although the difference was not significant (P = 0.073; table 5). The relative risk of patients developing respiratory failure that required artificial respiration was smaller in the treatment group than in the control group, but the difference was not significant (P = 0.094; table 5). However, the difference in the duration of respiratory assistance among 50 patients in both groups (six died during respiratory assistance) was significant (χ2 for trend 6.56, P = 0.01; see table 4).

The relative risk of death was smaller among patients in the treatment group, although the difference was not significant (P = 0.2). The wide confidence interval (0.78 to 7.05) suggests that the sample size was too small to detect a difference of this magnitude (table 5).

In general, all results showed improvement among patients in the treatment group. Differences were not significant for mortality and complications only.

Five patients had mild headache during the intrathecal procedure. In only one did this continue after the flow rate of the drug was reduced and the procedure finished; the headache stopped after 500 mg dipirona was given intravenously. We observed no meningeal irritation or meningitis among patients given intrathecal therapy. Among the 106 patients who were discharged, 64 returned to the outpatient clinic for a check up, in accordance with the study protocol. Of these, 37 belonged to the treatment group; they had no side effects.

Fourteen patients died during the study. The cause of death was not determined in seven, four died from septicaemia or septic shock, one died in an anoxic coma after prolonged cardiorespiratory arrest, one died from respiratory infection, and one died from acute respiratory failure. Half of these patients died within 10 days of admission. The others died between days 16 and 89. No particular pattern was observed for deaths.

Discussion

Patients treated for tetanus with human antitetanus immunoglobulin by the intrathecal route show better clinical progression than patients treated by the intramuscular route. They also showed fewer complications, particularly respiratory ones, and needed less intervention if they did and had a shorter duration of occurrence of spasms.

The use of mortality as an indicator of treatment response is common in evaluating therapeutic measures in tetanus. Indicators of morbidity and disease progression have been used in several studies.5-8,11,12,14,22 We monitored disease progression by grade of tetanus.19 Grade I and II predominated in the treatment group and grade III and IV predominated in the control group. Such differences were perceptible in the early stages of hospital stay and may be attributed to intrathecal therapy.

To our knowledge no studies have compared the duration of occurrence of spasms.5-8,11-15,22 Spasm is easily identified and a relatively reliable indicator. The duration of occurrence of spasms was shorter among patients in the treatment group. Duration of hospital stay was also shorter in the treatment group, which agrees with previous studies.8,12,22

What is already known on this topic

Neutralisation of tetanus toxin as part of tetanus therapy is still controversial, especially the dosage and route of administration

A meta-analysis of intrathecal therapy with antitetanus immunoglobulin was inconclusive in adults

What this study adds

Giving antitetanus immunoglobulin by the intrathecal route shows several clinical benefits

Patients treated by the intrathecal route had a better disease progression than those treated by the intramuscular route

Complications from tetanus, especially respiratory ones, are often followed by death.21,23 Studies have shown benefits on respiratory complications from intrathecal therapy. In one study, treated patients needed artificial respiration less and for shorter duration than controls.14 In another, tracheotomy and mechanical ventilation were less likely to be needed by patients with mild tetanus.

Over half of the patients in our study had some type of complication, such as respiratory infection or respiratory failure, most often in the control group. Although the differences were not statistically significant, in both cases the probability was close to the cut-off point. Patients in the treatment group who did require artificial respiration needed less assistance than those in the control group. The difference was statistically significant.

Fourteen of our 120 patients died; 10 had undergone conventional treatment and four intrathecal therapy. Although the difference was not statistically significant, the result is in the same direction as those for all other outcomes compared. It is possible that the sample was too small to study mortality, as suggested by the large confidence interval.

To calculate our sample size we chose the outcome of reduction in mortality. During the early stage of data collection the intensive care unit was created and mortality from tetanus decreased from 35% to almost 12%. This may have had made it more difficult to show a statistically significant difference between the groups.

An analysis of the causes of death, the circumstances in which it occurred, and the time from admission to death did not provide any important information with which to compare the two groups. Seven of the 14 deaths occurred suddenly and the cause was not determined; similar proportions have been reported elsewhere.4,23,24

Contributors: DBMF, RAAX, and AAB conceived and designed the study, analysed and interpreted the data, and drafted the article. VLV, AGV, and VMGA helped conceive the study and collect and interpret the data. DBMF will act as guarantor for the paper. The guarantor accepts full responsibility for the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: This study was funded by the Foundation of Support to Science and Technology of the State of Pernambuco, Health Foundation Amaury de Medeiros and Health Secretariat of the State of Pernambuco-Northeast Project; National Center of Epidemiology and National Health Foundation and Health Ministry of Brazil.

Ethical approval. This study was approved by the national ethics committee.

References

- 1.Bleck TP. Clostridium tetani (tetanus). In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Man-dell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2000: 2537-43.

- 2.Thwaites CL, Farrar JJ. Preventing and treating tetanus. The challenge continues in the face of neglect and lack of research. BMJ 2003;326: 117-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edmondson RS, Flowers MW. Intensive care in tetanus: management, complications and mortality in 100 cases. BMJ 1979;1: 1401-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harding-Goldson HE, Hanna WJ. Tetanus: a recurring intensive care problem. J Trop Med Hyg 1995;98: 179-84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanders RKM, Martyn B, Joseph R, Peacock ML. Intrathecal antitetanus serum (horse) in the treatment of tetanus. Lancet 1977;1: 974-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vakil BJ, Armitage P, Clifford RE, Laurence DR. Therapeutic trial of intracisternal human tetanus immunoglobulin in clinical tetanus. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1979;73: 579-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta PS, Goyal S, Kapoor R, Batra VK, Jain BK. Intrathecal human tetanus immunoglobulin in early tetanus. Lancet 1980;2: 439-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keswani NK, Singh AK, Upadhyana KD. Intrathecal tetanus anti-toxin in moderate and severe tetanus. J Indian Med Assoc 1980;75: 67-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossano C, Giugliano F. Prime esperienze e risultati terapeutici con immunoglobuline umane antitetaniche per via subaracnoidea. Minerva Anestesiol 1970;36: 725-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ildirim I. Intrathecal treatment of tetanus with antitetanus serum and prednisolone mixture. In: International Conference on Tetanus, São Paulo. Pan American Health Organisation - Scient public 1972;253: 119-26. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veronesi R, Bizzini B, Hutzler RU, Focaccia R, Mazza CC, Feldman C, et al. Eficácia do tratamento do tétano com antitoxina tetânica por via raquideana e/ou venosa. Estudo de 101 casos, com pesquisa sobre a permanência da gamaglobulina humana - F(ab)2 no1íqüor e no sangue. Revista brasileira Clínica e Terapêutica 1980;9: 301-19. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun KO, Chan YW, Cheung RTF, So PC, Yu YL, Li PCK. Management of tetanus: a review of 18 cases. J R Soc Med 1994;87: 135-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallais, H. Intérêt de l'administration intrathécale de sérum antitétanique et de corticoïdes pour le treatment du tétanos déclaré. La Nouvelle Presse médicale 1977;6: 571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.List WF. The immediate treatment of tetanus with high doses of human tetanus antitoxin. Notfallmedizin 1981;7: 731-3. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas PP, Crowell EB, Mathew M. Intrathecal anti-tetanus serum (ATS) and parenteral betamethasone in treatment of tetanus. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1982;76: 620-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abrutyn E, Berlin JA. Intrathecal therapy in tetanus, a meta-analysis. JAMA 1991;266: 2262-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman LM, Furberg CD, Demets DL. Fundamentals of clinical trials, 3rd ed. St Louis, MI: Mosby, 1996.

- 18.Miranda Filho DB, Ximenes RAA, Bernardino SN, Escarião AG. Caracterização epidemiológica do tétano no estado de Pernambuco no período de 1981 a 1995. Resumos do IX Congresso Brasileiro de Infectologia; 1996; Aug 25-9; Recife. Sociedade Brasileira de Infectologia.

- 19.Miranda Filho D, Ximenes R, Barone A, Vaz V, Vieira. Classificação clínica de pacientes com tétano para monitoramento da resposta a medidas terapêuticas. Braz J Infect Dis 2003;7(suppl 1): S18. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armitage P, Clifford R. Prognosis in tetanus: use of data from therapeutic trial. J Infect Dis 1978;138: 1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miranda Filho DB, Ximenes RAA, Bernardino SN, Escarião AG. Identification of risk factors for death from tetanus in Pernambuco, Brazil. A case control study. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2000;42: 333-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agarwal M, Thomas K, Peter JV, Jeyaseelan L, Cherian AM. A randomised double-blind sham controlled study of intrathecal human anti-tetanus immunoglobulin in the management of tetanus. Natl Med J India 1998;11: 209-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barone AA, Raineri HC, Ferreira JM. Tétano: aspectos epidemiológicos, clínicos e terapêuticos. Análise de 461 casos. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo 1976;31: 215-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Udwadia FE, Lall A, Udwadia ZF, Sekhar M, Vora A. Tetanus and its complications: intensive care and management experience in 150 Indian patients. Epidemiol Infect 1987;99: 675-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]