Abstract

Morphological transitions play an important role in virulence and virulence-related processes in a wide variety of pathogenic fungi, including the most commonly isolated human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. While environmental signals, transcriptional regulators, and target genes associated with C. albicans morphogenesis are well-characterized, considerably little is known about morphological regulatory mechanisms and the extent to which they are evolutionarily conserved in less pathogenic and less filamentous non-albicans Candida species (NACS). We have identified specific optimal filament-inducing conditions for three NACS (C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii), which are very limited, suggesting that these species may be adapted for niche-specific filamentation in the host. Only a subset of evolutionarily conserved C. albicans filament-specific target genes were induced upon filamentation in C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii. One of the genes showing conserved expression was UME6, a key filament-specific regulator of C. albicans hyphal development. Constitutive high-level expression of UME6 was sufficient to drive increased filamentation as well as biofilm formation and partly restore conserved filament-specific gene expression in both C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis, suggesting that evolutionary differences in filamentation ability among pathogenic Candida species may be partially attributed to alterations in the expression level of a conserved filamentous growth machinery. In contrast to UME6, NRG1, an important repressor of C. albicans filamentation, showed only a partly conserved role in controlling NACS filamentation. Overall, our results suggest that C. albicans morphological regulatory functions are partially conserved in NACS and have evolved to respond to more specific sets of host environmental cues.

INTRODUCTION

Candida species, which are normally found as commensals in the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, skin, and/or vagina of healthy individuals, are a major cause of both systemic and mucosal infections in a wide variety of immunocompromised patients (1). AIDS patients, organ transplant recipients, and cancer patients on immunosuppressive therapies are particularly susceptible to opportunistic infections (2–6). Candida species now represent the 4th leading cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections in the United States, with an attributable mortality rate of ∼40% (7, 8). Approximately 50% of invasive Candida infections can be attributed to Candida albicans, a major human fungal pathogen. Most of the remaining infections are caused by less pathogenic species, including Candida dubliniensis, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, Candida guilliermondii, and Candida glabrata (9–11). The frequencies of infections by individual species are known to vary by geographical region, previous exposure to antifungals, and patient population (11, 12). In addition, certain non-albicans Candida species (NACS) are known to more frequently infect specific niches within the host. For example, C. tropicalis is more commonly found on mucosal surfaces and is also associated with neutropenia and hematological malignancies (1, 13, 14). C. parapsilosis, frequently found on the skin and nails, typically forms biofilms on medical devices such as intravenous catheters and parenteral nutrition tubes and is associated with bloodstream and neonate infections (15–18). C. guilliermondii is an emerging fungal pathogen with a higher incidence in Latin America that has been encountered more frequently in nail infections but can also cause invasive infection in rare cases (19–21).

In general, C. albicans is significantly more virulent than NACS in a wide variety of infection models (22, 23). In part, this can be attributed to a generally increased ability of C. albicans to adhere to host cells and secrete degradative enzymes compared to that of most NACS (23–26). In addition, C. albicans also has the ability to undergo a morphological transition from yeast form (single ovoid cells) to pseudohyphal and hyphal filaments (elongated cells attached end-to-end) in response to a wide variety of environmental conditions (1, 27). C. albicans filamentation is required for virulence and important for several virulence-related processes, including invasion of epithelial cell layers, breaching of endothelial cells, lysis of macrophages, biofilm formation, and contact sensing (thigmotropism) (28–32). While many NACS can undergo the yeast-filament transition, they generally do not filament as readily, frequently, or robustly as C. albicans in response to a wide variety of environmental cues. More specifically, while nearly all pathogenic Candida species can grow as pseudohyphae, only 3 species (C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, and C. tropicalis) are capable of forming true hyphae (23, 33). This observation, combined with the finding that certain NACS infect particular host niches more frequently, raises the intriguing possibility that NACS may be adapted to filament more readily in specific host environments. An important step toward addressing this hypothesis is to determine optimal filament-inducing conditions for specific Candida species.

How exactly C. albicans evolved to become more pathogenic than NACS remains a central question in the field. Whole-genome sequencing has revealed that pathogenic Candida species show a significant expansion of gene families associated with virulence-related processes (e.g., Als-like adhesin and secreted lipase genes) compared to their nonpathogenic relatives (34). While certain Candida species (e.g., C. guilliermondii) generally have fewer members of genes in these families than C. albicans, others (e.g., C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis) do not, suggesting that gene family expansion alone cannot account for evolutionary differences. In the case of Candida dubliniensis, a large number of pseudogenes with intact C. albicans positional orthologs (several involved in filamentous growth) have been identified, suggesting that reductive evolution may partially account for differences in virulence (22, 35). In general, however, very little is known about molecular mechanisms that may explain how and why C. albicans evolved to become more pathogenic than other Candida species.

The most comprehensive studies to date that address this question have involved comparisons of C. albicans biofilm formation and filamentation with that of C. parapsilosis and C. dubliniensis, respectively. Specifically, the key transcriptional regulator Bcr1 has been shown to play an evolutionarily conserved role in the formation of biofilms in vitro and in vivo by both C. albicans and C. parapsilosis (36, 37). A comparative transcriptional analysis revealed that Bcr1 also shows conserved regulation of the CFEM gene family in both species; interestingly, while CFEM family members play a conserved role in iron acquisition by both C. albicans and C. parapsilosis, their role in biofilm formation appears to be specific to C. albicans (37). In C. dubliniensis, filamentation has been shown to occur more readily in response to nutrient-poor conditions and appears to be under negative control of the Tor pathway (38, 39). A comparison of the whole-genome transcriptional profiles of C. albicans and C. dubliniensis undergoing the yeast-filament transition identified a conserved core set of genes induced in both species. This gene set included cell surface/secreted genes as well as genes involved in stress response, DNA replication, cytoskeleton formation, and glycosylation; a starvation response involving the expression of genes in the glyoxylate cycle and fatty acid oxidation was also specifically observed in C. dubliniensis due to the experimental conditions used to induce filamentation in this species (38). In addition, UME6, which encodes a key filament-specific transcriptional regulator of C. albicans hyphal extension (40, 41), was induced during C. dubliniensis filamentation, and constitutive expression of UME6 was sufficient to drive hyphal growth in both species (38). Conversely, NRG1, a critical C. albicans filamentous growth repressor (42, 43), was shown to be downregulated upon filamentation in C. albicans and C. dubliniensis, and deletion of NRG1 increased filamentation in both species. Interestingly, in C. dubliniensis, UME6 induction and NRG1 downregulation occurred only in response to nutrient-poor filament-inducing conditions and not in response to the standard nutrient-rich C. albicans filament-inducing conditions (38). This finding suggested that while the basic C. albicans filamentous growth regulatory circuitry and target genes remain intact in C. dubliniensis, they have been rewired to respond to more specific environmental cues.

While previous studies comparing C. albicans filamentous growth regulatory mechanisms to those of C. dubliniensis are informative, C. dubliniensis is by far the most closely related NACS to C. albicans and one of the few Candida species also capable of forming true hyphae (23, 33, 34). Therefore, similarities in target gene expression and regulatory circuits are not entirely unexpected. However, very little is known about the extent to which filament-specific gene expression and regulatory circuits controlling C. albicans morphology are evolutionarily conserved in the more distantly related pathogenic Candida species, which account for the majority of NACS infections (9–11). In order to address this question, in this study we optimized the filament-inducing conditions for three commonly isolated NACS: C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii. In addition to examining the expression of several evolutionarily conserved filament-specific target genes under these conditions, we also demonstrated that C. albicans UME6- and NRG1-directed regulatory circuits are only partially conserved among these species. In addition, we determined the extent to which evolutionary “weaknesses” in NACS filamentation and filament-specific gene expression can be overcome by UME6 expression. Our results provide new insights into the evolution of mechanisms important for morphology and virulence-related processes in Candida species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and DNA constructions.

Strains used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Please note that C. tropicalis exhibits a decreased ability to filament upon extended cryogenic storage. To address this issue, a lyophilized starter culture was maintained on yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YEPD) plates at 30°C without freezing. Please see the supplemental material for a detailed description of all strain and DNA constructions. Primers used in this study are described in Table S2.

Media and growth conditions.

The standard non-filament-inducing conditions for all species were YEPD (2% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 1% glucose [wt/vol]) at 30°C (44). Filament-inducing media included liquid YEPD plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for C. albicans, Lee's pH 3.25 medium (45) for C. guilliermondii, synthetic defined (SD) medium (6.7 g/liter yeast nitrogen base without amino acids [BD Biosciences]) for C. tropicalis, and synthetic complete (SC) medium (6.7 g/liter yeast nitrogen base without amino acids [BD Biosciences], 5 g/liter uracil, 10 g/liter tryptophan, 5 g/liter histidine HCl, 5 g/liter arginine HCl, 5 g/liter methionine, 7.5 g/liter tyrosine, 15 g/liter leucine, 7.5 g/liter isoleucine, 7.5 g/liter lysine HCl, 12 g/liter l-phenylalanine, 37 g/liter valine, 50 g/liter threonine, 50 g/liter serine, 5 g/liter adenine, 2% glucose) for C. parapsilosis. CAF2-1 was used as the C. albicans wild-type control for the experiment to determine the effect of deletion of NRG1 on colony morphology (solid medium). C. albicans liquid filament inductions were performed as described previously (40), using strain DK318; the zero-hour sample was collected just prior to induction. In order to induce C. tropicalis filamentation, four 10-ml cultures were grown in a roller drum in YEPD at 30°C overnight. These cultures were then combined, washed twice in water to remove traces of YEPD, and used to inoculate 60 ml of inducing (SD plus 0.75% glucose plus 50% fetal bovine serum [Atlanta Biologicals] at 37°C) or noninducing (YEPD at 30°C) medium at an initial optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.5, and cultures were shaken at 200 rpm. Samples for the zero-hour time point were collected immediately following dilution into fresh medium. For C. parapsilosis filament induction, cells were grown in YEPD at 30°C overnight, washed in sterile water, and resuspended in 5 ml SD. The cells were then diluted in SD and grown at 30°C (200 rpm) to an OD600 of 4. Next, cells were resuspended in 10 ml SD and used to inoculate 60 ml each of inducing (SC plus 20% fetal bovine serum [Atlanta Biologicals] at 37°C) and non-filament-inducing (YEPD at 30°C) media at an initial OD600 of 0.6. The zero-hour sample was taken immediately prior to inoculation into fresh medium. Cultures were shaken at 200 rpm. C. guilliermondii filament inductions were performed by initially growing cells in YEPD at 30°C (200 rpm) overnight. The culture was then pelleted at 3,000 × g, resuspended in 10 ml H2O, and used to inoculate 125 ml of inducing (Lee's pH 3.25) or noninducing (YEPD) medium at an initial OD600 of 0.5. Both cultures were incubated at 30°C (200 rpm). The zero-hour sample was taken just prior to inoculation into fresh medium. The tetO-CtUME6 strain and corresponding C. tropicalis wild-type control strain were grown in 5 ml YEPD plus 100 ng/ml doxycycline (Dox) overnight, the next morning each culture was washed twice with water and resuspended in 5 ml sterile water, and 10 μl of each cell suspension was then diluted in 10 ml sterile water. Twenty-five microliters of this dilution was used to inoculate 50 ml YEPD supplemented with 50% FBS in the absence or presence of the indicated Dox concentration. Cultures were grown at 30°C, and aliquots of cells were harvested at 24 h for RNA preparation and fixation. The tetO-CpUME6 strain and corresponding C. parapsilosis wild-type control strain were grown in 5 ml YEPD plus 10 ng/ml Dox overnight at 30°C, washed twice in water, and resuspended in 5 ml sterile water. Ten microliters of each suspension was diluted into 10 ml sterile water, and 250 μl of this dilution was used to inoculate 50 ml SC in the absence or presence of the indicated Dox concentration. Cultures were grown at 30°C, and aliquots of cells were harvested at 36 h for fixation and RNA extraction.

RNA preparation and analysis.

C. albicans total RNA was prepared by using an SV Total RNA isolation kit (Promega), with the following modifications: cells were resuspended in 225 μl buffer RLT and bead beated for 5 min (hyphae) or 2.5 min (yeast), with resting for 1 min on ice for every 2.5 min of bead beating. C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii total RNAs were prepared by using a Maxwell16 instrument system (Promega) and a Maxwell16 LEV simplyRNA cell kit (Promega). Initially the cells were bead beated with 700 μl beads plus 700 μl TRIzol for 2.5 min and then chilled on ice for 1 min. The cells were then centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 × g and 4°C, and the supernatant was extracted using 150 μl chloroform. After centrifuging, 100 μl of supernatant was loaded on Maxwell16 LEV simplyRNA columns, and the standard kit procedure was followed. DNase treatments were performed using DNase I (Life Technologies), and the purified RNA was converted to cDNA by use of a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Life Technologies). Total RNAs for the tetO-CtUME6 and tetO-CpUME6 strains and the corresponding wild-type strains were prepared using the hot acid phenol method as described previously (46). Real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using SYBR green PCR master mix (Life Technologies) on a Chromo4 real-time PCR detector (Bio-Rad). Due to the relatively high levels of RDN18 (encoding 18S rRNA) compared to NRG1 and UME6, cDNA was diluted 1:1,000 in order to quantitate the RDN18 transcript. Northern analysis was performed as described previously (40), with the modifications that hybridizations were performed at 50°C and blots were washed 3 times (for 30 min each) at 70°C. Primers used to detect transcripts by qRT-PCR and to generate probes for Northern analysis are described in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

Biofilm assays.

Biofilm formation was performed using a standard 96-well assay as described previously (47, 48). Levels of biofilm formation were assessed using a standard semiquantitative colorimetric 2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide (XTT) reduction assay (47, 49).

RESULTS

Optimization of filamentous growth conditions for C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii.

In order to compare the expression patterns of C. albicans filamentous growth regulators and target genes with those of other Candida species, we sought to optimize liquid filament-inducing conditions for several of these species. Wild-type cultures of each species were grown under a wide variety of conditions, including most conditions previously known to induce filamentation in C. albicans, such as Spider medium, Lee's pH 6.8 medium, YEPD at 37°C, YEPD plus 10% serum at 37°C, RPMI medium, alpha minimum essential medium (α-MEM), cornmeal, and synthetic low ammonia plus 2% dextrose (SLAD; nitrogen starvation medium) (1, 27). Additional conditions included YEPD at 30°C, SD medium, SC medium, Lee's medium (at various pHs), tryptic soy broth supplemented with whole sheep blood, glucose and amino acid starvation media. Aside from media, other variables tested included the length of incubation, temperature, inoculum cell density, rotary shaker speed, percentage of fetal bovine serum or sheep blood, CO2 levels, anaerobic conditions, and preculture conditions. Criteria for determining the level of filamentation included the percentage of cells in filamentous form, filament length, number of cells per filament, and frequency of hyphal filaments (C. tropicalis only). Based on this exhaustive battery of assays, we were able to optimize liquid filament-inducing conditions for C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii, as shown in Table 1. Although several other NACS were tested, our attempts to optimize filamentation in liquid medium for these species were unsuccessful, and as a consequence, we have chosen to focus on the species listed above. Interestingly, as is the case with C. dubliniensis (38), we found that filamentation of C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii was inhibited in media containing peptone and other rich nutrients (e.g., YEPD), suggesting that the nutrient-sensing Tor pathway may play a conserved role in repressing the yeast-filament transition for multiple NACS. Despite numerous attempts, we were unable to identify a common liquid filament-inducing condition for all species.

Table 1.

Optimized liquid filament induction conditions for specific Candida species

| Parameter | Descriptiona |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | C. tropicalis | C. parapsilosis | C. guilliermondii | |

| Inducing conditions | YEPD + 10% FBS, 37°C | SD + 0.75% glucose + 50% FBS, 37°C | SC + 20% FBS, 37°C | Lee's pH 3.25, 30°C |

| Noninducing conditions | YEPD, 30°C | YEPD, 30°C | YEPD, 30°C | YEPD, 30°C |

| Inoculum OD600b | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

All cultures for all species were grown at 200 rpm.

Please note that optimal filamentation was observed using the indicated inoculum OD600 and specific culture volumes as indicated in Materials and Methods.

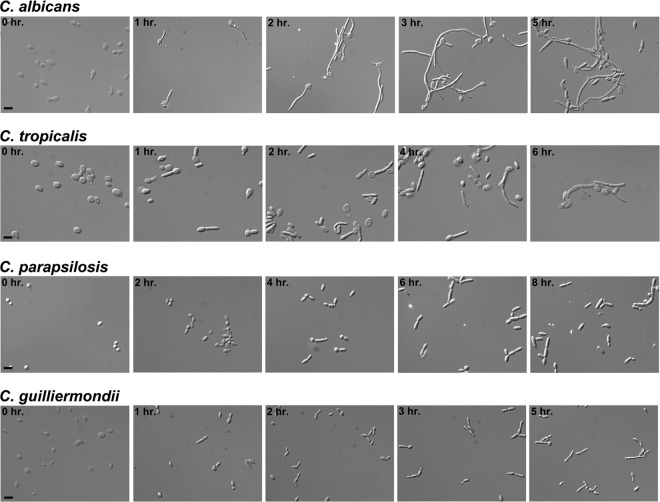

A comparison of C. albicans filament induction with that observed in C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii is shown in Fig. 1 (note that there are natural differences in cell size among the species). As previously demonstrated (50), in the presence of YEPD plus 10% serum at 37°C, most C. albicans cells formed germ tubes by the 1-hour postinduction time point. Nearly all the cells were growing as extended hyphae by the 2- and 3-hour time points, whereas at the 5-hour time point, the induction declined and the population showed larger numbers of pseudohyphae and elongated yeast cells. For C. tropicalis, germ tubes were also apparent at 1 hour postinduction in SD plus 0.75% glucose plus 10% serum at 37°C, although their frequency was lower, and virtually all were in pseudohyphal form. C. tropicalis grew mostly as a combination of yeast, elongated yeast, and short pseudohyphae for the remaining time points, with a few hyphal filaments apparent at the 6-hour time point; please note that due to extensive clumping (and an inability of the species to tolerate sonication), it was difficult to accurately assess the ratio of morphologies in the C. tropicalis culture. For C. parapsilosis, pseudohyphal germ tubes were observed at 4 hours postinduction in SC plus 20% serum at 37°C. At the 6- and 8-hour time points, C. parapsilosis grew as a mixture of yeast and short pseudohyphal filaments, which were typically no longer than about 3 cells in length. A similar filamentation pattern was observed for C. guilliermondii grown in Lee's pH 3.25 medium at 30°C, although the overall time course was shorter. All species grew in the yeast form under standard non-filament-inducing conditions (YEPD at 30°C), as indicated in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. Our ability to directly compare filamentation in all four species was somewhat limited given the necessity of using different filament-inducing conditions. Overall, however, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii generally showed fewer filamentous cells, shorter filaments, and either no hyphae or significantly fewer hyphae than C. albicans, even in the presence of optimized liquid filament-inducing conditions. These results are consistent with previous reports that NACS do not undergo the yeast-filament transition as frequently or strongly as C. albicans (1, 23, 33).

Fig 1.

Optimized filament induction time courses for C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii. Wild-type strains of each species were induced by growth under the corresponding species-specific optimal filament-inducing conditions described in Table 1. Aliquots of cells were harvested, fixed in 4.5% formaldehyde, washed twice with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and visualized using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy. Bars = 10 μm.

Transcriptional regulation of UME6, but not NRG1, is evolutionarily conserved upon filamentation in C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii.

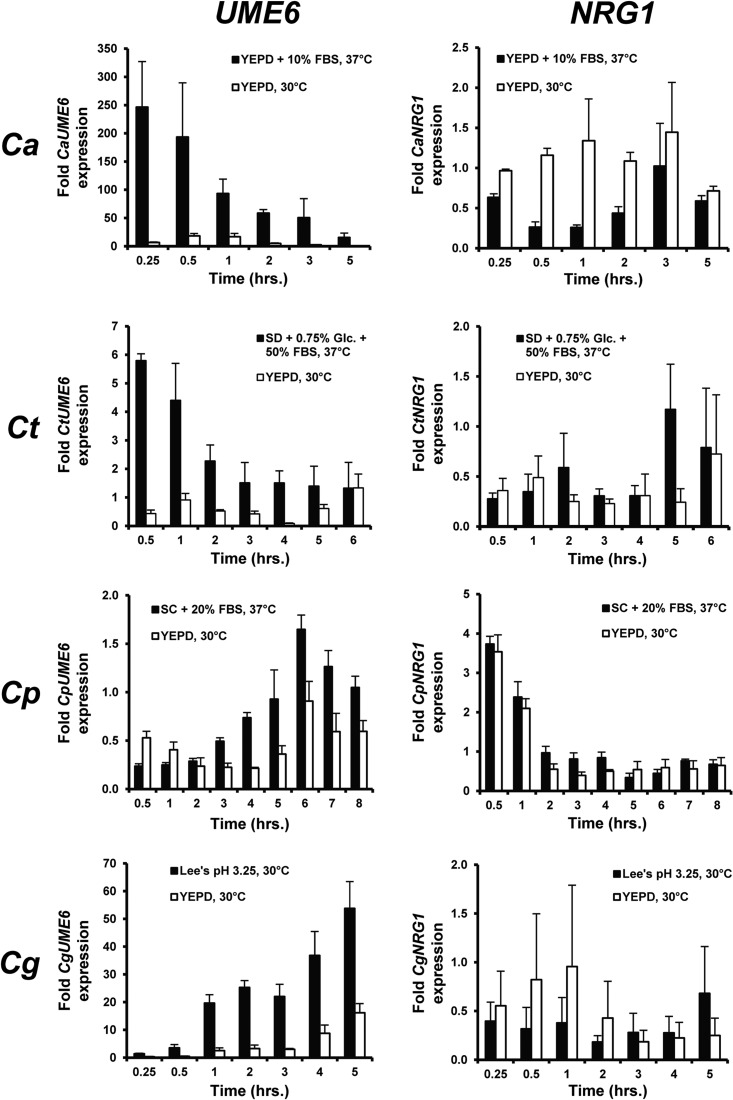

Using the optimized filament-inducing conditions described above, we next sought to determine the extent to which two key C. albicans filamentous growth regulatory events, induction of UME6 and downregulation of NRG1, are conserved in C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii. Cells from a wild-type strain of each species were grown as described for Fig. 1, and total RNA was prepared for quantitative RT-PCR analysis. As indicated in Fig. 2, C. albicans UME6 was significantly induced (>200-fold) at 15 min postinduction and showed gradually lower induction levels as the time course proceeded. A similar expression pattern was observed for C. tropicalis UME6, except that the overall fold induction (∼5- to 6-fold at maximum) was significantly lower. In the case of C. parapsilosis, UME6 showed a modest but reproducible increase in expression under filament-inducing versus noninducing conditions, which first became apparent at the 3-hour time point and continued through the remainder of the time course. C. guilliermondii showed strong induction of UME6 (>15-fold) starting at the 1-hour time point and through the end of the time course. Interestingly, UME6 induction appeared to correlate more closely with the timing of maximal filament formation (Fig. 1) in C. parapsilosis and C. guilliermondii than in C. albicans and C. tropicalis.

Fig 2.

Filament-specific induction of UME6, but not downregulation of NRG1, is evolutionarily conserved in C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii. Aliquots of cells grown for Fig. 1 and for Fig. S1 in the supplemental material were harvested for total RNA preparation. Transcript levels for UME6 and NRG1 were determined by qRT-PCR analysis and normalized to either an ACT1 (C. albicans and C. parapsilosis) or 18S rRNA (C. tropicalis and C. guilliermondii) internal control. Fold expression was determined by dividing normalized UME6 or NRG1 expression values for each time point by the corresponding normalized expression value for the zero-hour time point. Data shown represent the means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) for three biological replicates run in technical duplicates. Glc., glucose; FBS, fetal bovine serum; Ca, C. albicans; Ct, C. tropicalis; Cp, C. parapsilosis; Cg, C. guilliermondii.

Consistent with previous studies (42, 43, 50), NRG1, a key repressor of filamentation, was downregulated ∼4-fold in C. albicans upon filament induction by growth in YEPD plus 10% serum at 37°C. In contrast to UME6, however, there was generally not a significant difference between NRG1 transcript levels when cells were grown under filament-inducing versus noninducing conditions for C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii. Overall changes in NRG1 transcript levels which occurred under both conditions over the time courses may have been due to dilution and/or cell density-dependent effects. Therefore, induction of the key C. albicans morphology regulator UME6, but not downregulation of the C. albicans filamentous growth repressor NRG1, appears to be evolutionarily conserved during filament induction in C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii.

Partial evolutionary conservation of C. albicans filament-specific gene expression in C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii.

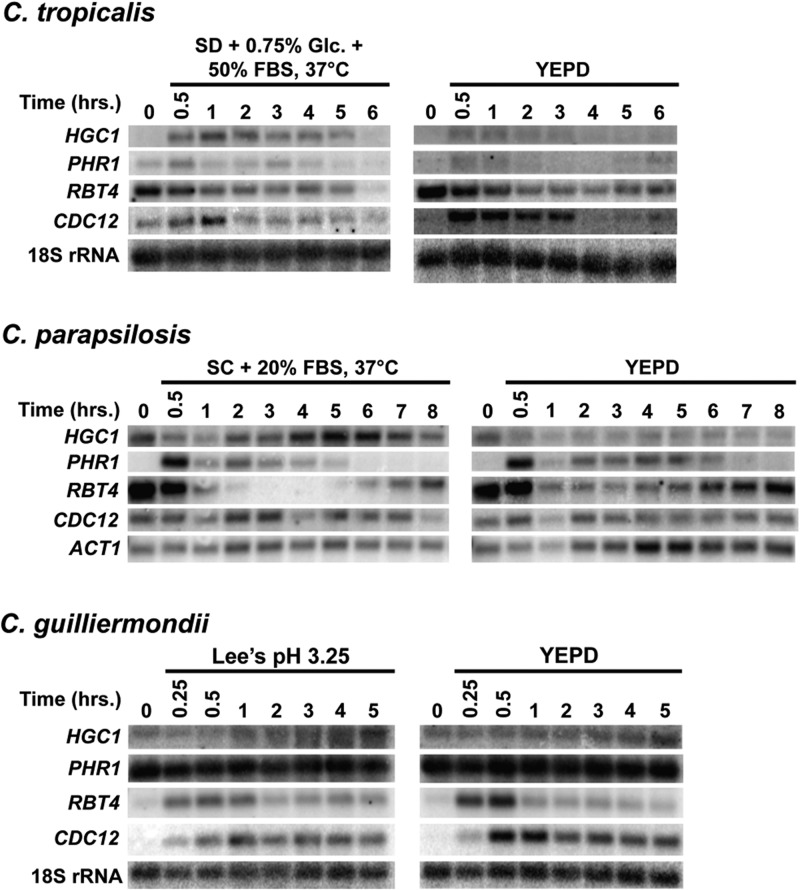

We next sought to determine the extent to which C. albicans filament-specific gene expression was conserved during filamentation in C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii. Using total RNA from cells grown as described for Fig. 1, Northern analysis was performed to examine the expression of four evolutionarily conserved (as defined using the SYNERGY algorithm [51; http://www.broadinstitute.org/regev/orthogroups/]) C. albicans filament-specific target genes in C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii under both filament-inducing and noninducing conditions. HGC1 encodes a G1 cyclin-related protein important for hyphal development (52), PHR1 encodes a putative cell wall glycosidase important for virulence (53, 54), RBT4 encodes a secreted plant pathogenesis-related (PR) protein also associated with virulence (55, 56), and CDC12 encodes a septin involved in hyphal growth (57). All of these genes have previously been shown to be significantly induced in response to filament-inducing conditions in C. albicans, including growth in serum at 37°C (50, 52, 58–60). The C. tropicalis HGC1 ortholog showed the greatest induction early in the time course (Fig. 3); a similar induction pattern was previously observed for C. albicans HGC1 in YEPD plus serum at 37°C (58). In C. parapsilosis, HGC1 appeared to be expressed at the zero time point prior to induction but still showed increased expression over the time course, particularly at the later time points and compared to expression under noninducing conditions. A similar expression pattern was also observed for the C. guilliermondii HGC1 ortholog upon filamentation. Strikingly, however, PHR1, RBT4, and CDC12 did not show significant differences in expression patterns under filament-inducing versus noninducing conditions (in certain cases, there actually appeared to be slightly greater expression under non-filament-inducing conditions) (Fig. 3). Interestingly, at the zero time point, just prior to induction, C. parapsilosis RBT4 appeared to be expressed strongly under both conditions. C. guilliermondii PHR1 also appeared to be highly expressed throughout the time course, regardless of filament induction. Please note that because variations in ACT1 gene expression were observed during the C. tropicalis and C. guilliermondii time courses, 18S rRNA was used as an internal loading control for these species. Overall, these results suggest that C. albicans filament-specific gene expression is only partially conserved during filamentation by C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii.

Fig 3.

Partial conservation of C. albicans filament-specific gene expression during filamentation in C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii. Wild-type strains of the indicated species were grown as described for Fig. 1 and Fig. S1 in the supplemental material, and cells were harvested at the indicated time points for total RNA preparation. Northern analysis was performed using 3 μg of total RNA and probes for the indicated conserved genes. ACT1 (C. parapsilosis) or 18S rRNA (C. tropicalis and C. guilliermondii) was included as a loading control. Glc., glucose; FBS, fetal bovine serum.

Nrg1 functions as a conserved repressor of filamentation in C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis but not C. guilliermondii.

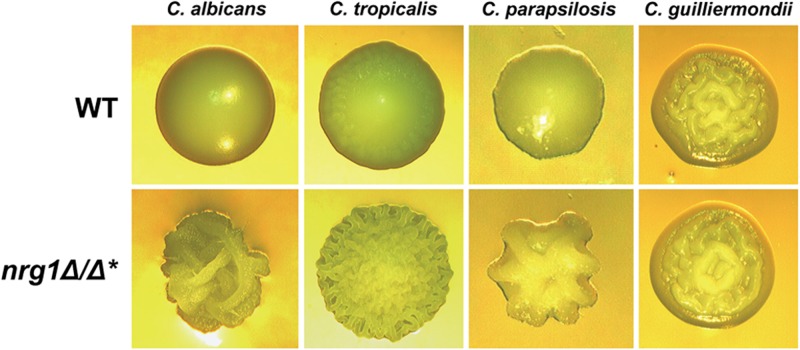

In C. albicans, Nrg1 directs strong repression of both filamentation and filament-specific target genes (42, 61). C. albicans nrg1Δ/Δ mutants are highly filamentous under both liquid and solid non-filament-inducing conditions. To determine whether the C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii NRG1 orthologs function in a similar manner, we deleted NRG1 in all three species. When the strains were grown under liquid inducing or non-filament-inducing conditions, none of these mutants showed significant differences in morphology compared to the parental wild-type strains (data not shown). However, under solid non-filament-inducing conditions, the C. tropicalis nrg1Δ/Δ mutant showed significantly greater filamentation than the wild-type strain, as reflected by a highly wrinkled colony morphology (Fig. 4). A similar increase in filamentation by the C. parapsilosis nrg1Δ/Δ mutant was observed at an early time point when cells were grown under mild filament-inducing conditions on agar medium. In contrast, the C. guilliermondii nrg1Δ mutant failed to show an increase in filamentous growth compared to the wild-type strain even under solid filament-inducing conditions. Microscopic examination of cells grown on solid plates confirmed the presence of increased filaments in the C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis nrg1Δ/Δ mutants (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Overall, our results indicate that NRG1 plays a partially conserved role in the repression of filamentation by NACS.

Fig 4.

NRG1 represses filamentation of C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis, but not C. guilliermondii, on solid medium. Images show colonies formed on solid agar by wild-type (WT) and nrg1 strains of the indicated species. C. albicans and C. tropicalis were grown on YEPD at 30°C for 2 and 3 days, respectively. C. parapsilosis was grown on SD plus 10 mM lysine at 30°C for 3 days, and C. guilliermondii was grown on YEPD plus 10% serum for 2 days at 37°C. All images were taken at a magnification of ×2, except for those of C. parapsilosis, which were taken at a magnification of ×4. *Please note that C. guilliermondii, a haploid species, is a nrg1Δ strain.

High-level UME6 expression is sufficient to drive enhanced filamentous growth and partially restore evolutionarily conserved filament-specific gene expression in C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis.

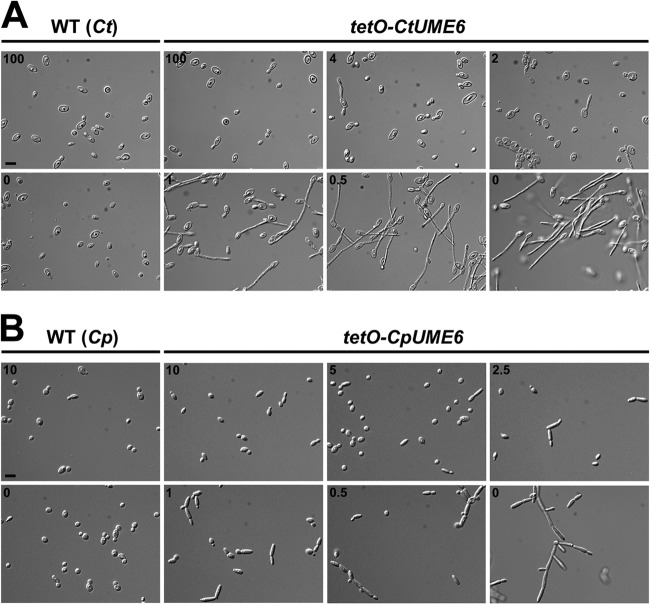

We previously demonstrated that under non-filament-inducing conditions, expression levels of UME6 are sufficient to determine C. albicans morphology (62). More specifically, low-level UME6 specifies a largely pseudohyphal population, whereas constitutive high-level expression of UME6 drives nearly complete hyphal growth. In order to determine whether this critical morphological regulatory function has been conserved, the orthologs of UME6 in C. tropicalis (CtUME6) and C. parapsilosis (CpUME6) were placed under the control of an E. coli tet operator in a strain expressing constitutively high levels of a tetracycline-repressible transactivator. Due to technical and experimental limitations, we were unable to successfully generate a C. guilliermondii UME6 expression strain. As shown in Fig. 5, UME6 was expressed at high levels in both tetO-CtUME6 and tetO-CpUME6 strains, only in the absence, but not the presence, of Dox, a tetracycline derivative. In addition, no significant induction of UME6 was observed in the corresponding wild-type control strains in either the absence or presence of Dox. Under solid non-filament-inducing conditions, C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis UME6 expression caused a significant increase in filamentation, as evidenced by highly wrinkled colony morphologies of the tetO-CtUME6 and tetO-CpUME6 strains, specifically in the absence, but not the presence, of Dox (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). As indicated in Fig. 6, both C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis wild-type strains grew largely in the yeast form in liquid media, regardless of the presence of Dox. The tetO-CtUME6 strain also grew as a yeast in the presence of 100 ng/ml Dox but started to show a few pseudohyphal filaments at the 4-ng/ml Dox concentration when UME6 was first expressed at very low levels (Fig. 5A and 6A). As UME6 levels increased at 1 ng/ml Dox, a significantly greater proportion of cells grew as filaments, and a mixture of yeast, pseudohyphae, and hyphae was observed. In the absence of Dox, there was a larger proportion of hyphal filaments, although yeast and pseudohyphae were still observed. Calcofluor white staining verified that hyphal filaments generated by C. tropicalis upon expression of UME6 contained true septal junctions (see Fig. S4). The tetO-CpUME6 strain grew largely as yeast cells at the 10-ng/ml Dox concentration (Fig. 6B). While a few short pseudohyphal germ tubes were apparent at the 5-ng/ml Dox concentration, there was a significant increase in the frequency of pseudohyphae at the 2.5-ng/ml and 1-ng/ml Dox concentrations, which corresponded to a large rise in UME6 transcript levels (Fig. 5B). In general, the overall level and frequency of filamentation of the tetO-CtUME6 and tetO-CpUME6 strains in the absence of Dox appeared to be greater than those observed for the corresponding C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis wild-type strains grown under optimized liquid filament-inducing conditions (although, as previously explained, this was somewhat difficult to assess for the C. tropicalis wild-type strain due to clumping). These results strongly suggest that the ability of UME6 expression to drive enhanced filamentous growth is conserved in both C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis; however, unlike the case of C. albicans, maximal UME6 expression is not capable of driving nearly complete hyphal growth in either of these species.

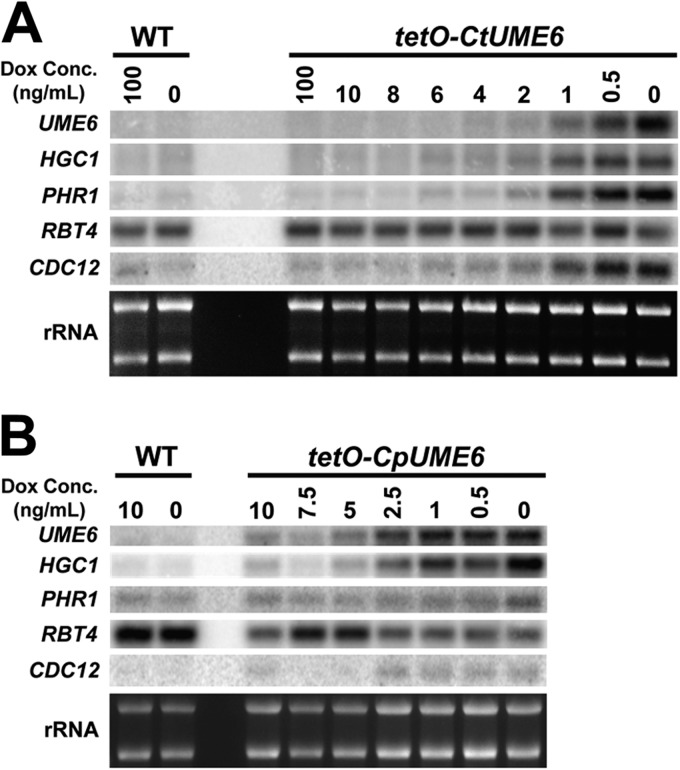

Fig 5.

UME6 expression is sufficient to induce evolutionarily conserved filament-specific genes in C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis. Aliquots of cells grown as described for Fig. 6 were harvested for total RNA preparation. Northern analysis was performed using 3 μg of total RNA from the indicated C. tropicalis (A) or C. parapsilosis (B) strains and probes for the indicated conserved genes in each species. rRNA is shown as a loading control. Ct, C. tropicalis; Cp, C. parapsilosis.

Fig 6.

UME6 expression is sufficient to drive filamentous growth in C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis. The indicated strains of C. tropicalis (A) and C. parapsilosis (B) were grown in YEPD plus 50% FBS for 24 h and SC for 36 h, respectively, at 30°C in the presence of the indicated Dox concentrations (ng/ml). Aliquots of cells were fixed in 4.5% formaldehyde, washed twice with 1 × PBS, and visualized using DIC microscopy. Bars = 10 μm. Ct, C. tropicalis; Cp, C. parapsilosis.

We next sought to determine whether UME6 expression was sufficient to induce the C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis orthologs of evolutionarily conserved C. albicans filament-specific transcripts. Total RNA was prepared from cells grown as described for Fig. 6, and Northern analysis was used to assess HGC1, PHR1, RBT4, and CDC12 transcript levels. Each of these transcripts was previously shown to be induced by UME6 in C. albicans (62, 63). As indicated in Fig. 5, none of the transcripts showed significant expression differences in the C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis wild-type strains in the presence or absence of Dox. Interestingly, however, CtHGC1, CtPHR1, and CtCDC12 transcripts appeared to be significantly induced in the tetO-CtUME6 strain as Dox levels declined and CtUME6 levels rose (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the CtRBT4 transcript was not affected by increased CtUME6 and was expressed at constitutive levels in both the wild-type and tetO-CtUME6 strains at all Dox concentrations. Similar results were observed for the tetO-CpUME6 strain, except that CpPHR1 and CpCDC12 were only weakly induced and the CpRBT4 level slightly declined in response to increased CpUME6 expression (Fig. 5B). Overall, our results indicate that UME6 functions as a conserved regulator of morphology determination in C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis and that high-level UME6 expression is sufficient to partially restore evolutionarily conserved filament-specific gene expression in these species.

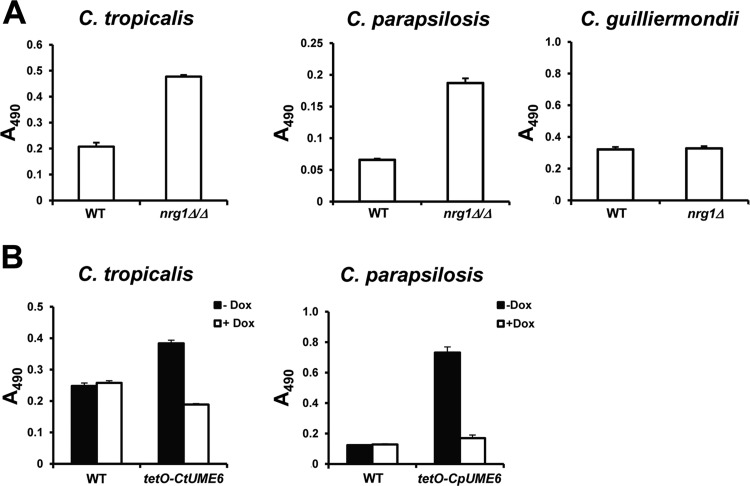

NRG1 and UME6 function as conserved regulators of biofilm formation in C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis.

In order to determine whether NRG1 and UME6 also play conserved roles in other virulence-related processes of Candida species, we examined biofilm formation. Candida biofilms are complex microbial communities joined by an exopolymeric matrix that can form on and adhere strongly to host tissues as well as catheters and implanted medical devices. These biofilms are highly resistant to antifungal therapies, protect against host immune defenses, and serve as reservoirs for infection (64–67). In C. albicans, filamentation is known to play an important role in biofilm formation (68, 69). Expression of the C. albicans NRG1 filamentous growth repressor was previously shown to strongly inhibit this process (70). Conversely, expression of UME6 is known to enhance biofilm formation in C. albicans (71). To determine whether NRG1 also functions as a repressor of biofilm formation in C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii, the nrg1 deletion mutants of these species were compared to their corresponding wild-type control strains using a standard biofilm assay on polystyrene plates. As shown in Fig. 7A, deletion of NRG1 caused a significant increase in both C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis biofilm formation, suggesting that in these species, NRG1 is also a repressor of biofilm formation. In contrast, the C. guilliermondii nrg1Δ mutation did not cause a significant difference in biofilm formation, even when these assays were performed under a variety of different environmental conditions (Fig. 7A and data not shown). As previously shown for C. albicans (71), constitutive high-level UME6 expression was sufficient to cause enhanced C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis biofilm formation, to levels above those observed in the corresponding wild-type control strains (Fig. 7B). These results indicate that NRG1 and UME6 function as evolutionarily conserved regulators of biofilm formation in both C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis and that NRG1 appears to have lost this function in C. guilliermondii.

Fig 7.

Regulation of biofilm formation by NRG1 and UME6 in C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis. Suspensions (1 × 106 cells/ml) of nrg1 (A) or tetO-UME6 (B) strains and corresponding wild-type (WT) control strains from the indicated species were allowed to form biofilms for 24 h at 30°C on 96-well polystyrene plates in YEPD (C. parapsilosis), SC (C. tropicalis), or Lee's pH 3.25 (C. guilliermondii) medium. For panel B, biofilms were formed in the presence or absence of 20 μg/ml Dox. Biofilm formation was assessed by a standard colorimetric XTT reduction assay (47, 49). Error bars represent standard errors (n = 8).

DISCUSSION

Infections by Candida species remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality for a wide variety of immunocompromised individuals (2–8). While NACS account for approximately 50% of all Candida infections (9–11), considerably more research has focused on the major human fungal pathogen C. albicans, and far less is known about the mechanisms by which NACS infect host tissues. In this study, we focused on a key C. albicans virulence trait, the ability to undergo a morphological transition from yeast to filaments, and determined the extent to which environmental conditions, transcriptional regulatory functions, and target gene expression are evolutionarily conserved in three pathogenic NACS: C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii.

Our finding that none of these species share the same optimal filament-inducing conditions is consistent with a previous report that C. dubliniensis has different optimal inducing conditions from those for C. albicans (38) and suggests that each NACS may have evolved to form filaments in response to specific host niches. Consistent with this hypothesis, certain NACS have been found to more frequently colonize and infect particular host environments. C. tropicalis is commonly found on mucosal surfaces (oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, and vagina) (1, 13), which may explain its ability to filament in response to serum in the presence of glucose at 37°C without peptone or other nutrients. Although mucosal surfaces are not necessarily “nutrient poor,” C. tropicalis in this environment faces significant competition from other bacterial and fungal flora, which limits nutrient availability. We also observed that C. parapsilosis forms filaments more readily under stationary conditions, again in the presence of serum at 37°C but lacking rich nutrients, which may account for its propensity to grow and form biofilms on catheters and implanted medical devices and to infect solid tissue surfaces, such as skin, nails, bones, and joints (15–18). Our finding that C. guilliermondii shows optimal filamentation under nitrogen limitation at low pH (Lee's pH 3.25 medium) and 30°C is consistent with the observation that this species is found more commonly in subcutaneous host environments (e.g., nails), which are known to have a reduced pH (20, 72). Finally, our observation that media such as YEPD, containing peptone and other rich nutrients, inhibit filamentation of C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii, combined with a previous report that this is also the case for C. dubliniensis (38), suggests that all of these NACS, to some extent, have retained filamentation as an evolutionarily conserved starvation/scavenging response. This ancient filamentation response is present even in many yeasts that have not evolved as pathogens, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which undergoes the transition to pseudohyphae under nitrogen starvation conditions (73). In this respect, C. albicans, which has retained the starvation response but also acquired the ability to robustly filament under a variety of nutrient-rich conditions, appears to be better adapted for colonization and infection of a wider range of host niches. A recent report that C. albicans opaque cells, which are mating competent, can undergo filamentation in response to distinct environmental cues also suggests that C. albicans further evolved cell type-specific filamentation for particular host niches (74).

Even under optimal filament-inducing conditions, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii do not filament as robustly as C. albicans, suggesting that additional mechanisms, besides nutrient sensing, may account for evolutionary differences in filamentation ability. In order to address this hypothesis, we sought to determine whether two key regulators of C. albicans filamentous growth played conserved roles in NACS filamentation. Our demonstration that UME6, a critical regulator of C. albicans morphology determination and hyphal extension (40, 41, 62), is transcriptionally induced during filamentation in all four species, combined with a previous report that UME6 is also highly induced upon filamentation in C. dubliniensis (38), strongly suggests that this morphological regulatory pathway has been evolutionarily conserved but rewired to respond to different environmental cues. Importantly, C. albicans, which filaments more robustly than NACS, showed the highest levels of UME6 induction. In addition, although UME6 was not induced as highly in C. tropicalis, the induction pattern was very similar to that of C. albicans, with the highest expression levels observed at early time points. C. tropicalis is more closely related to C. albicans than C. parapsilosis or C. guilliermondii (34) and is one of the only other Candida species capable of forming true hyphae. Our findings therefore suggest that in C. tropicalis, as in C. albicans, early induction of UME6 is important for amplifying the level and duration of filament-specific gene expression in order to promote hyphal extension. In contrast, C. parapsilosis and C. guilliermondii, which are more distantly related to C. albicans and only capable of forming pseudohyphae (1, 34), show UME6 induction at later time points which are more closely associated with maximal filamentation. This result suggests the possibility of species-specific differences in the kinetics of filamentous growth regulatory events. Our finding that, as in C. albicans, increased expression of UME6 in C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis is sufficient to drive filamentous growth as well as filament-specific gene expression, in combination with the previous finding that UME6 expression promotes C. dubliniensis hyphal growth (38), provides further evidence that UME6 functions as an evolutionarily conserved regulator of morphology in Candida species. In C. albicans, UME6 has been shown to direct hyphal growth via a pathway involving the HGC1-encoded cyclin-related protein (58). Our demonstration that HGC1 is also induced upon filamentation in C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii, shows similar induction kinetics to those of UME6 in each species, and can be induced by high-level UME6 expression in C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis strongly suggests that this filamentation pathway has also been evolutionarily conserved among Candida species.

In C. albicans, UME6 has been shown to function in a transcriptional feedback loop with NRG1, which ultimately leads to the amplification of filament-specific gene expression (40). C. albicans NRG1 is also under negative control by the protein kinase A-cyclic AMP (PKA-cAMP) pathway (75). In the presence of strong filament-inducing conditions, the NRG1 transcript is downregulated in response to this pathway, and Nrg1 is displaced from target promoters to relieve repression of filament-specific genes and initiate hyphal growth. Hyphal growth, in turn, is maintained by inhibition of the Tor pathway, which allows a strong activator of filamentation, Brg1, to occupy hypha-specific promoters in place of Nrg1 (76). A previous study has indicated that in C. dubliniensis, the Candida species most closely related to C. albicans, NRG1 is also downregulated in response to strong filament-inducing conditions (38). Our observation that transcriptional downregulation of NRG1 does not occur exclusively during filamentation in the distantly related species C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii suggests that the mechanism to drive hyphal growth described above has evolved more recently. In addition, because UME6 is induced upon filamentation in all species, but NRG1 downregulation is filament specific only in C. albicans and C. dubliniensis, our results suggest that the development of a transcriptional feedback loop between UME6 and NRG1 may also be a more recent evolutionary event. Interestingly, however, NRG1 appears to have retained its function as a repressor of filamentation in both C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis, but not C. guilliermondii. However, increased filamentation of C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis nrg1Δ/Δ mutants was observed only under specific growth conditions and, in the case of C. parapsilosis, required the additional presence of weak filament-inducing signals. Given that C. guilliermondii is more distantly related to C. albicans than C. parapsilosis and that C. parapsilosis is more distantly related to C. albicans than C. tropicalis (34), our findings suggest that NRG1 initially evolved from a very weak repressor of filamentation to a strong repressor that was subsequently integrated into existing filamentous growth regulatory circuits in Candida species. In S. cerevisiae, NRG1 is known to function as a strong transcriptional repressor of glucose-repressed genes and, together with the paralog NRG2, also directs repression of diploid pseudohyphal growth in response to nitrogen starvation via a pathway involving the Snf1 protein kinase (77–79). In this respect, NRG1 generally appears to function as an evolutionarily conserved repressor of filamentation in both S. cerevisiae and Candida species. It is unclear at this point why NRG1 does not appear to be associated with C. guilliermondii filamentation. A BLAST analysis suggests that this species does not have any additional NRG1 paralogs which could compensate for the loss of this gene in the C. guilliermondii nrg1Δ mutant.

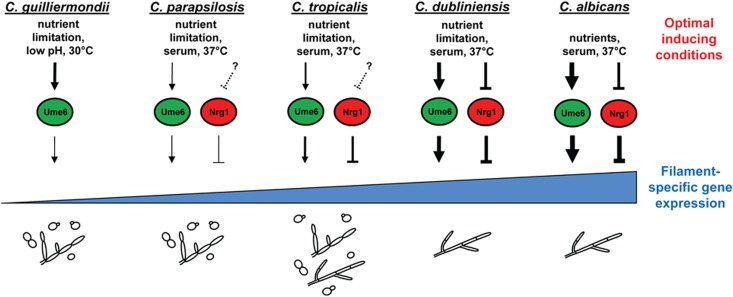

Perhaps the greatest insights into the evolution of morphology in Candida species can be gained by examining target gene expression. Of the approximately 105 genes known to be involved in C. albicans filamentation (50, 80), 75 are conserved in C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii (as defined using the SYNERGY algorithm [51; http://www.broadinstitute.org/regev/orthogroups/]). This observation suggests that the transcriptional program important for directing filamentous growth has remained largely intact in Candida species. However, our finding that several evolutionarily conserved C. albicans filament-specific target genes are not expressed in C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii under optimal filament-inducing conditions suggests either that these genes are no longer controlled by filamentous growth signals or that the strength of induction in response to these signals is not sufficiently high. Results from our UME6 expression experiment indicate that both of these possibilities are occurring. In the case of RBT4, gene expression is clearly not induced in response to UME6-driven filamentation in both C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis, suggesting that this gene may no longer be a component of the filamentous growth programs of these species. In contrast, however, two other conserved filament-specific genes not induced under optimal filament-inducing conditions in C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii, PHR1 and CDC12, are induced in response to high-level UME6 expression in C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis. These results, in combination with our finding that UME6 expression directs a somewhat higher level of filamentation than that observed with optimal environmental filament-inducing conditions, suggest that expression levels of the filamentous growth program have changed during the evolution of Candida species. More specifically, the inability of NACS to filament as robustly as C. albicans may be attributed at least partly to a reduced expression level of their filamentous growth machinery. Consistent with this hypothesis, whole-genome transcriptional profiling experiments have indicated that while the orthologs of many genes in the C. albicans filamentous growth program are induced upon C. dubliniensis filamentation, the expression levels of most, but not all, of these genes are somewhat lower in C. dubliniensis than in C. albicans (38). Lower expression of filamentation programs in NACS may have occurred as a consequence of a reduced ability of these species to sense environmental filament-inducing conditions, transduce these signals strongly, and/or activate target genes via transcriptional regulators (Fig. 8). Our demonstration that while UME6 expression can partially overcome the evolutionary “weakness” in C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis filamentation and cause strong expression of C. tropicalis PHR1 and CDC12 but only very weak expression of these genes in C. parapsilosis suggests that evolutionary changes have occurred at the levels of both signal transduction and transcriptional regulation. Consistent with the latter possibility, the C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, and C. tropicalis predicted Ume6 proteins all contain a glutamine-rich putative transcriptional activation domain, and the size of this domain decreases with evolutionary distance from C. albicans. Predicted proteins encoded by C. parapsilosis and C. guilliermondii UME6 orthologs appear to lack the glutamine-rich domain sequence entirely. Also consistent with the notion that transcriptional regulators in Candida species have evolved, a recent study showed that the C. albicans master regulator of white-opaque switching, WOR1, has a dual role in both white-opaque switching and filamentation in C. tropicalis (81). An alternative explanation for our observation that certain evolutionarily conserved C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis target genes are induced in response to UME6 expression but not in response to environmental conditions is that there may be additional conditions in the host environment which are capable of driving even higher levels of filamentation and filament-specific gene expression than those we have observed in vitro. However, given that the identity of these putative conditions is currently unknown, this remains a difficult possibility to test.

Fig 8.

Model for evolution of morphological regulatory functions in Candida species. NACS are listed in the order of their evolutionary distance from C. albicans (34). For all species, the indicated optimal filament-inducing conditions (see Table 1 for more details) cause transcriptional induction of UME6 (the strength of induction is indicated by the arrow thickness). NRG1 does not appear to play a role in the C. guilliermondii morphological transition, and at this point, it is unclear whether NRG1 functions as a constitutive repressor of C. parapsilosis and C. tropicalis filamentation or is downregulated by other filament-inducing conditions which have not yet been determined (dashed lines). In both C. dubliniensis and C. albicans, the NRG1 transcript is known to be downregulated by the indicated conditions (38, 42, 43). Ume6 and Nrg1 function to activate and repress, respectively, the expression of filament-specific genes (the strength of transcriptional activity is indicated by the line thickness). As a consequence of evolutionary changes in signaling pathways and/or transcriptional regulators such as Ume6 and Nrg1, there is an increase in the number of filament-specific genes induced, as well as their overall expression level. The resulting morphological outcome for each species is shown at the bottom. Please note that the ratio of morphologies (yeast/pseudohyphae/hyphae) shown is not necessarily precise. Evolutionary changes in a significant number of additional signaling pathways and transcriptional regulators (not shown in this model) are also likely to affect morphological outcomes, and other evolutionary mechanisms (not depicted) are also likely to play important roles in this process.

It is important to bear in mind that the ability to undergo a morphological transition from yeast to filaments is only one virulence property of Candida species. For certain Candida species (e.g., Candida glabrata), filamentation does not appear to play a major role in pathogenicity (82). Our demonstration that UME6 is a conserved enhancer of biofilm formation in C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis, as well as our finding that NRG1 functions as a conserved biofilm repressor in C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis but not in C. guilliermondii, suggests partial evolutionary conservation of regulatory functions that control additional virulence-related properties in Candida species. Consistent with this notion, Bcr1 functions as a conserved biofilm regulator in C. albicans and C. parapsilosis, while CFEM family members play a conserved role in C. parapsilosis iron acquisition but not biofilm formation (36, 37). Future studies, particularly those which employ genomic and proteomic approaches, are likely to shed more light on the degrees to which both regulatory functions and the expression of target genes are evolutionarily conserved for additional virulence properties of Candida species. Ultimately, these studies will provide greater insight into how and why C. albicans evolved to become a major human fungal pathogen.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Brian Wickes for a critical reading of the manuscript as well as for fruitful discussions during the course of the experiments. We also thank Martha Arnaud (Candida Genome Database) for bioinformatics assistance, as well as Brian Wickes, Cletus Kurtzman, Julia Köhler, Nicolas Papon, and Brian Wong for strains, plasmids, and/or use of equipment.

E.L., G.V., and D.S.C. were supported by COSTAR fellowships (T32DE14318). D.S.C. also received support from an NRSA predoctoral fellowship from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (5F31DE021930). This work was also supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant 5RO1AI083344 as well as by a Voelcker Young Investigator Award from the Max and Minnie Tomerlin Voelcker Fund to D.K.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 2 August 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/EC.00164-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Odds FC. 1988. Candida and candidosis, 2nd ed. Baillière Tindall, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dupont PF. 1995. Candida albicans, the opportunist. A cellular and molecular perspective. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 85:104–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weig M, Gross U, Muhlschlegel F. 1998. Clinical aspects and pathogenesis of Candida infection. Trends Microbiol. 6:468–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filler SG, Kullberg BJ. 2002. Deep-seated candidal infections, p 341–348 In Calderone R. (ed), Candida and candidiasis. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannon RD, Chaffin WL. 1999. Oral colonization by Candida albicans. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 10:359–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dongari-Bagtzoglou A, Wen K, Lamster IB. 1999. Candida albicans triggers interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 responses by oral fibroblasts in vitro. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 14:364–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edmond MB, Wallace SE, McClish DK, Pfaller MA, Jones RN, Wenzel RP. 1999. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in United States hospitals: a three-year analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent SM, Seifert H, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. 2004. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:309–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horn DL, Neofytos D, Anaissie EJ, Fishman JA, Steinbach WJ, Olyaei AJ, Marr KA, Pfaller MA, Chang CH, Webster KM. 2009. Epidemiology and outcomes of candidemia in 2019 patients: data from the prospective antifungal therapy alliance registry. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:1695–1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfaller MA, Andes D, Diekema DJ, Espinel-Ingroff A, Sheehan D. 2010. Wild-type MIC distributions, epidemiological cutoff values and species-specific clinical breakpoints for fluconazole and Candida: time for harmonization of CLSI and EUCAST broth microdilution methods. Drug Resist. Updat. 13:180–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krcmery V, Barnes AJ. 2002. Non-albicans Candida spp. causing fungaemia: pathogenicity and antifungal resistance. J. Hosp. Infect. 50:243–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruhnke M. 2006. Epidemiology of Candida albicans infections and role of non-Candida albicans yeasts. Curr. Drug Targets 7:495–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedderwick SA, Lyons MJ, Liu M, Vazquez JA, Kauffman CA. 2000. Epidemiology of yeast colonization in the intensive care unit. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:663–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wingard JR. 1995. Importance of Candida species other than C. albicans as pathogens in oncology patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:115–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Asbeck EC, Clemons KV, Stevens DA. 2009. Candida parapsilosis: a review of its epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical aspects, typing and antimicrobial susceptibility. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 35:283–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nosek J, Holesova Z, Kosa P, Gacser A, Tomaska L. 2009. Biology and genetics of the pathogenic yeast Candida parapsilosis. Curr. Genet. 55:497–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin AS, Costa SF, Mussi NS, Basso M, Sinto SI, Machado C, Geiger DC, Villares MC, Schreiber AZ, Barone AA, Branchini ML. 1998. Candida parapsilosis fungemia associated with implantable and semi-implantable central venous catheters and the hands of healthcare workers. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 30:243–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trofa D, Gacser A, Nosanchuk JD. 2008. Candida parapsilosis, an emerging fungal pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21:606–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chakrabarti A, Chatterjee SS, Rao KL, Zameer MM, Shivaprakash MR, Singhi S, Singh R, Varma SC. 2009. Recent experience with fungaemia: change in species distribution and azole resistance. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 41:275–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghannoum MA, Hajjeh RA, Scher R, Konnikov N, Gupta AK, Summerbell R, Sullivan S, Daniel R, Krusinski P, Fleckman P, Rich P, Odom R, Aly R, Pariser D, Zaiac M, Rebell G, Lesher J, Gerlach B, Ponce-De-Leon GF, Ghannoum A, Warner J, Isham N, Elewski B. 2000. A large-scale North American study of fungal isolates from nails: the frequency of onychomycosis, fungal distribution, and antifungal susceptibility patterns. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 43:641–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Mendez M, Kibbler C, Erzsebet P, Chang SC, Gibbs DL, Newell VA. 2006. Candida guilliermondii, an opportunistic fungal pathogen with decreased susceptibility to fluconazole: geographic and temporal trends from the ARTEMIS DISK antifungal surveillance program. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:3551–3556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moran GP, Coleman DC, Sullivan DJ. 2012. Candida albicans versus Candida dubliniensis: why is C. albicans more pathogenic? Int. J. Microbiol. 2012:205921. 10.1155/2012/205921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moran GP, Sullivan DJ, Coleman DC. 2002. Emergence of non-Candida albicans Candida species as pathogens, p 37–53 In Calderone RA. (ed), Candida and candidiasis. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hube B. 1996. Candida albicans secreted aspartyl proteinases. Curr. Top. Med. Mycol. 7:55–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King RD, Lee JC, Morris AL. 1980. Adherence of Candida albicans and other Candida species to mucosal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 27:667–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klotz SA, Drutz DJ, Harrison JL, Huppert M. 1983. Adherence and penetration of vascular endothelium by Candida yeasts. Infect. Immun. 42:374–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown AJ. 2002. Expression of growth form-specific factors during morphogenesis in Candida albicans, p 87–93 In Calderone RA. (ed), Candida and candidiasis. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumamoto CA, Vinces MD. 2005. Contributions of hyphae and hypha-co-regulated genes to Candida albicans virulence. Cell. Microbiol. 7:1546–1554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korting HC, Hube B, Oberbauer S, Januschke E, Hamm G, Albrecht A, Borelli C, Schaller M. 2003. Reduced expression of the hyphal-independent Candida albicans proteinase genes SAP1 and SAP3 in the efg1 mutant is associated with attenuated virulence during infection of oral epithelium. J. Med. Microbiol. 52:623–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lo HJ, Kohler JR, DiDomenico B, Loebenberg D, Cacciapuoti A, Fink GR. 1997. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell 90:939–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gow NA, Brown AJ, Odds FC. 2002. Fungal morphogenesis and host invasion. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:366–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saville SP, Lazzell AL, Monteagudo C, Lopez-Ribot JL. 2003. Engineered control of cell morphology in vivo reveals distinct roles for yeast and filamentous forms of Candida albicans during infection. Eukaryot. Cell 2:1053–1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson DS, Carlisle PL, Kadosh D. 2011. Coevolution of morphology and virulence in Candida species. Eukaryot. Cell 10:1173–1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butler G, Rasmussen MD, Lin MF, Santos MA, Sakthikumar S, Munro CA, Rheinbay E, Grabherr M, Forche A, Reedy JL, Agrafioti I, Arnaud MB, Bates S, Brown AJ, Brunke S, Costanzo MC, Fitzpatrick DA, de Groot PW, Harris D, Hoyer LL, Hube B, Klis FM, Kodira C, Lennard N, Logue ME, Martin R, Neiman AM, Nikolaou E, Quail MA, Quinn J, Santos MC, Schmitzberger FF, Sherlock G, Shah P, Silverstein KA, Skrzypek MS, Soll D, Staggs R, Stansfield I, Stumpf MP, Sudbery PE, Srikantha T, Zeng Q, Berman J, Berriman M, Heitman J, Gow NA, Lorenz MC, Birren BW, Kellis M, Cuomo CA. 2009. Evolution of pathogenicity and sexual reproduction in eight Candida genomes. Nature 459:657–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackson AP, Gamble JA, Yeomans T, Moran GP, Saunders D, Harris D, Aslett M, Barrell JF, Butler G, Citiulo F, Coleman DC, de Groot PW, Goodwin TJ, Quail MA, McQuillan J, Munro CA, Pain A, Poulter RT, Rajandream MA, Renauld H, Spiering MJ, Tivey A, Gow NA, Barrell B, Sullivan DJ, Berriman M. 2009. Comparative genomics of the fungal pathogens Candida dubliniensis and Candida albicans. Genome Res. 19:2231–2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ding C, Butler G. 2007. Development of a gene knockout system in Candida parapsilosis reveals a conserved role for BCR1 in biofilm formation. Eukaryot. Cell 6:1310–1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ding C, Vidanes GM, Maguire SL, Guida A, Synnott JM, Andes DR, Butler G. 2011. Conserved and divergent roles of Bcr1 and CFEM proteins in Candida parapsilosis and Candida albicans. PLoS One 6:e28151. 10.1371/journal.pone.0028151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Connor L, Caplice N, Coleman DC, Sullivan DJ, Moran GP. 2010. Differential filamentation of Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis is governed by nutrient regulation of UME6 expression. Eukaryot. Cell 9:1383–1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sullivan DJ, Moran GP. 2011. Differential virulence of Candida albicans and C. dubliniensis: a role for Tor1 kinase? Virulence 2:77–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banerjee M, Thompson DS, Lazzell A, Carlisle PL, Pierce C, Monteagudo C, Lopez-Ribot JL, Kadosh D. 2008. UME6, a novel filament-specific regulator of Candida albicans hyphal extension and virulence. Mol. Biol. Cell 19:1354–1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeidler U, Lettner T, Lassnig C, Muller M, Lajko R, Hintner H, Breitenbach M, Bito A. 2009. UME6 is a crucial downstream target of other transcriptional regulators of true hyphal development in Candida albicans. FEMS Yeast Res. 9:126–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braun BR, Kadosh D, Johnson AD. 2001. NRG1, a repressor of filamentous growth in C. albicans, is down-regulated during filament induction. EMBO J. 20:4753–4761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murad AMA, Leng P, Straffon M, Wishart J, Macaskill S, MacCallum D, Schnell N, Talibi D, Marechal D, Tekaia F, d'Enfert C, Gaillardin C, Odds FC, Brown AJP. 2001. NRG1 represses yeast-hypha morphogenesis and hypha-specific gene expression in Candida albicans. EMBO J. 20:4742–4752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guthrie C, Fink GR. 1991. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. Academic Press, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee KL, Buckley HR, Campbell CC. 1975. An amino acid liquid synthetic medium for the development of mycelial and yeast forms of Candida albicans. Sabouraudia 13:148–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. 1992. Current protocols in molecular biology. Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley-Interscience, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pierce CG, Uppuluri P, Tristan AR, Wormley FL, Jr, Mowat E, Ramage G, Lopez-Ribot JL. 2008. A simple and reproducible 96-well plate-based method for the formation of fungal biofilms and its application to antifungal susceptibility testing. Nat. Protoc. 3:1494–1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramage G, Vande Walle K, Wickes BL, Lopez-Ribot JL. 2001. Standardized method for in vitro antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida albicans biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2475–2479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramage G, Vandewalle K, Wickes BL, Lopez-Ribot JL. 2001. Characteristics of biofilm formation by Candida albicans. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 18:163–170 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kadosh D, Johnson AD. 2005. Induction of the Candida albicans filamentous growth program by relief of transcriptional repression: a genome-wide analysis. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:2903–2912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wapinski I, Pfeffer A, Friedman N, Regev A. 2007. Automatic genome-wide reconstruction of phylogenetic gene trees. Bioinformatics 23:i549–i558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zheng X, Wang Y, Wang Y. 2004. Hgc1, a novel hypha-specific G1 cyclin-related protein regulates Candida albicans hyphal morphogenesis. EMBO J. 23:1845–1856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ghannoum MA, Spellberg B, Saporito-Irwin SM, Fonzi WA. 1995. Reduced virulence of Candida albicans PHR1 mutants. Infect. Immun. 63:4528–4530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fonzi WA. 1999. PHR1 and PHR2 of Candida albicans encode putative glycosidases required for proper cross-linking of beta-1,3- and beta-1,6-glucans. J. Bacteriol. 181:7070–7079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rohm M, Lindemann E, Hiller E, Ermert D, Lemuth K, Trkulja D, Sogukpinar O, Brunner H, Rupp S, Urban CF, Sohn K. 2013. A family of secreted pathogenesis-related proteins in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 87:132–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Braun BR, Head WS, Wang MX, Johnson AD. 2000. Identification and characterization of TUP1-regulated genes in Candida albicans. Genetics 156:31–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Warenda AJ, Konopka JB. 2002. Septin function in Candida albicans morphogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:2732–2746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carlisle PL, Kadosh D. 2010. Candida albicans Ume6, a filament-specific transcriptional regulator, directs hyphal growth via a pathway involving Hgc1 cyclin-related protein. Eukaryot. Cell 9:1320–1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saporito-Irwin SM, Birse CE, Sypherd PS, Fonzi WA. 1995. PHR1, a pH-regulated gene of Candida albicans, is required for morphogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:601–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Braun BR, Johnson AD. 2000. TUP1, CPH1 and EFG1 make independent contributions to filamentation in Candida albicans. Genetics 155:57–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murad AM, d'Enfert C, Gaillardin C, Tournu H, Tekaia F, Talibi D, Marechal D, Marchais V, Cottin J, Brown AJ. 2001. Transcript profiling in Candida albicans reveals new cellular functions for the transcriptional repressors CaTup1, CaMig1 and CaNrg1. Mol. Microbiol. 42:981–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carlisle PL, Banerjee M, Lazzell A, Monteagudo C, Lopez-Ribot JL, Kadosh D. 2009. Expression levels of a filament-specific transcriptional regulator are sufficient to determine Candida albicans morphology and virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:599–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carlisle PL, Kadosh D. 2013. A genome-wide transcriptional analysis of morphology determination in Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 24:246–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ramage G, Saville SP, Thomas DP, Lopez-Ribot JL. 2005. Candida biofilms: an update. Eukaryot. Cell 4:633–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Douglas LJ. 2003. Candida biofilms and their role in infection. Trends Microbiol. 11:30–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kojic EM, Darouiche RO. 2004. Candida infections of medical devices. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:255–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chandra J, Kuhn DM, Mukherjee PK, Hoyer LL, McCormick T, Ghannoum MA. 2001. Biofilm formation by the fungal pathogen Candida albicans: development, architecture, and drug resistance. J. Bacteriol. 183:5385–5394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Finkel JS, Mitchell AP. 2011. Genetic control of Candida albicans biofilm development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9:109–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ramage G, VandeWalle K, Lopez-Ribot J, Wickes B. 2002. The filamentation pathway controlled by the Efg1 regulator protein is required for normal biofilm formation and development in Candida albicans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 214:95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Uppuluri P, Pierce CG, Thomas DP, Bubeck SS, Saville SP, Lopez-Ribot JL. 2010. The transcriptional regulator Nrg1p controls Candida albicans biofilm formation and dispersion. Eukaryot. Cell 9:1531–1537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Banerjee M, Uppuluri P, Zhao XR, Carlisle PL, Vipulanandan G, Villar CC, Lopez-Ribot JL, Kadosh D. 2013. Expression of UME6, a key regulator of Candida albicans hyphal development, enhances biofilm formation via Hgc1- and Sun41-dependent mechanisms. Eukaryot. Cell 12:224–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Murdan S, Milcovich G, Goriparthi GS. 2011. An assessment of the human nail plate pH. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 24:175–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gimeno CJ, Ljungdahl PO, Styles CA, Fink GR. 1992. Unipolar cell divisions in the yeast S. cerevisiae lead to filamentous growth: regulation by starvation and RAS. Cell 68:1077–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Si H, Hernday AD, Hirakawa MP, Johnson AD, Bennett RJ. 2013. Candida albicans white and opaque cells undergo distinct programs of filamentous growth. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003210. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lu Y, Su C, Wang A, Liu H. 2011. Hyphal development in Candida albicans requires two temporally linked changes in promoter chromatin for initiation and maintenance. PLoS Biol. 9:e1001105. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lu Y, Su C, Liu H. 2012. A GATA transcription factor recruits Hda1 in response to reduced Tor1 signaling to establish a hyphal chromatin state in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002663. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kuchin S, Vyas VK, Carlson M. 2002. Snf1 protein kinase and the repressors Nrg1 and Nrg2 regulate FLO11, haploid invasive growth, and diploid pseudohyphal differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:3994–4000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Park SH, Koh SS, Chun JH, Hwang HJ, Kang HS. 1999. Nrg1 is a transcriptional repressor for glucose repression in STA1 gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:2044–2050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhou H, Winston F. 2001. NRG1 is required for glucose repression of the SUC2 and GAL genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Genet. 2:5. 10.1186/1471-2156-2-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nantel A, Dignard D, Bachewich C, Harcus D, Marcil A, Bouin AP, Sensen CW, Hogues H, van het Hoog M, Gordon P, Rigby T, Benoit F, Tessier DC, Thomas DY, Whiteway M. 2002. Transcription profiling of Candida albicans cells undergoing the yeast-to-hyphal transition. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:3452–3465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Porman AM, Hirakawa MP, Jones SK, Wang N, Bennett RJ. 2013. MTL-independent phenotypic switching in Candida tropicalis and a dual role for Wor1 in regulating switching and filamentation. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003369. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Do Carmo-Sousa L. 1969. Distribution of yeasts in nature, p 79–105 In Rose AH, Harrison JS. (ed), The yeasts, vol 1 Academic Press, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.