Abstract

Human lungs are constantly exposed to bacteria in the environment, yet the prevailing dogma is that healthy lungs are sterile. DNA sequencing-based studies of pulmonary bacterial diversity challenge this notion. However, DNA-based microbial analysis currently fails to distinguish between DNA from live bacteria and that from bacteria that have been killed by lung immune mechanisms, potentially causing overestimation of bacterial abundance and diversity. We investigated whether bacterial DNA recovered from lungs represents live or dead bacteria in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and lung samples in young healthy pigs. Live bacterial DNA was DNase I resistant and became DNase I sensitive upon human antimicrobial-mediated killing in vitro. We determined live and total bacterial DNA loads in porcine BAL fluid and lung tissue by comparing DNase I-treated versus untreated samples. In contrast to the case for BAL fluid, we were unable to culture bacteria from most lung homogenates. Surprisingly, total bacterial DNA was abundant in both BAL fluid and lung homogenates. In BAL fluid, 63% was DNase I sensitive. In 6 out of 11 lung homogenates, all bacterial DNA was DNase I sensitive, suggesting a predominance of dead bacteria; in the remaining homogenates, 94% was DNase I sensitive, and bacterial diversity determined by 16S rRNA gene sequencing was similar in DNase I-treated and untreated samples. Healthy pig lungs are mostly sterile yet contain abundant DNase I-sensitive DNA from inhaled and aspirated bacteria killed by pulmonary host defense mechanisms. This approach and conceptual framework will improve analysis of the lung microbiome in disease.

INTRODUCTION

Microbes are the predominant inhabitants of our world. Therefore, humans are constantly exposed to bacteria in the environment, including air, drinking water, and food. Concentrations of airborne bacteria can reach levels of 106 CFU/m3 in outdoor air, resulting in inhalation of up to 107 CFU per day in normal lungs under resting conditions (1, 2). In addition, bacteria in the oropharyngeal cavity are constantly aspirated by healthy humans (3). Despite constant exposure to these high bacterial loads, the lungs are normally uninfected.

Whether the surface of healthy lungs is normally sterile or colonized by symbiotic bacteria has been the subject of debate for more than a century (4). While dogma dictates that healthy lungs are normally sterile, more recent data based on DNA sequencing and quantification suggest the presence of a bacterial biomass in the lungs (5–7). In diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cystic fibrosis, specific profiles of lung bacterial communities are associated with disease exacerbation, treatment with antimicrobials, and other host factors (6, 8–13). In other respiratory diseases, such as asthma, in which the role of airway bacteria is less clear, there are also interesting associations between specific bacterial diversity profiles and disease severity (7, 10, 11). Moreover, some of the bacterial populations described in these studies correspond to bacteria that are unculturable in currently available growth media and conditions and would have otherwise gone undetected before the advent of DNA-based bacterial identification.

Multiple mechanisms can effectively kill bacteria in the lungs; therefore, a generally overlooked problem in newer DNA-based studies of microbial diversity in the lungs and elsewhere is that the DNA being studied is likely to be a combination of DNA from live bacteria and from bacteria that were dead when the sample was obtained (14). This suggests that DNA-based analysis of bacterial diversity may overestimate abundance and function under certain conditions. Moreover, the current gold standard in most studies of lung microbial diversity is the sample obtained by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) or the protected specimen brush. In both cases, contamination from the oropharyngeal flora may confound results (5).

In the 1980s and 1990s, Chastre, Torres, and others developed and validated quantitative BAL as a method to diagnose pulmonary infections (15–20). During these studies, lung histology and bacterial culture obtained after thoracotomy immediately after death were used as the gold standard to determine the accuracy of quantitative BAL. A bacterial threshold of 103 CFU/ml or more was established as an indicator of bacterial pneumonia. The significance of levels of less than 103 CFU/ml in BAL samples remains unknown, and these levels are generally dismissed as contamination from the oropharyngeal flora.

Similar studies to validate newer DNA-based methods of bacterial diversity analysis would be extremely complicated. A recent study analyzed samples obtained with BAL and protected specimen brushes in humans and showed the similarities in bacterial communities in the airways and oral cavity, concluding that the airways contain a variable and low-biomass microbiome (5). Whether the detected bacterial DNA sequences correspond to dead or living bacteria has remained unanswered in most studies of the airway microbiome.

In this study, we investigated whether bacterial DNA in the lungs corresponds to live or dead bacteria. We compared culture and quantitative PCR (qPCR)-based bacterial quantification in BAL fluid and lung samples obtained under sterile conditions in young healthy pigs, which allowed the use of the same type of instruments and procedures used in human studies. Moreover, we describe a method that allowed us to distinguish DNA belonging to intact bacteria and that of damaged or dead bacteria for bacterial quantification in the lungs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects.

All studies were performed on pigs (Sus scrofa) between 5 and 6 weeks of age and fed antibiotic-free food for at least 7 days prior to euthanasia for unrelated experiments, after which a sterile right thoracotomy was performed to sample lung tissue from the right lower lobe.

Transbronchial BAL.

In order to obtain bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid samples without any contamination from the oral cavity, we inserted a sterile 14-gauge needle and catheter into the right lower lobe bronchus after thoracotomy as described above and performed a BAL with normal saline. This was done in the same airway to be accessed transorally by bronchoscopy as described below in order to obtain matched samples.

Transoral BAL.

A fiber optic bronchoscope (BF-P10; Olympus, Philadelphia, PA) was cleaned with a detergent (Asepti-Zyme; Ecolab, St. Paul, MN) by wiping and suction channel aspiration, followed by immersion for an hour. A sterile water rinse and air drying were performed, after which right lower lobe bronchoscopy (without lidocaine) and BAL were performed according to the guidelines of the American Thoracic Society and Busse et al. (21).

DNA extraction and DNase I treatment.

Five hundred microliters of BAL fluid or a homogenate (02-542; Fisher Healthcare, Houston, TX) of 100 mg lung tissue in 2 ml of 0.9% NaCl was incubated with 500 μg/ml DNase I (10104159001; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Manheim, Germany) or DNase I buffer at 37°C for 10 min, followed by DNase I inactivation at 75°C for 10 min. Samples were then mixed with RLT Plus buffer plus β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME) (1053393; Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA), followed by 35 s of bead beating (693; Biospec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, OK) in a Lysing Matrix E tube (6914-100; MP Biomedicals LLC, Solon, OH). After lysis, the standard DNeasy blood and tissue kit (69506; Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) protocol was followed with elution in 100 μl H2O. The sample DNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE).

qPCR.

Bacterial 16S rRNA gene quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed in quadruplicate using 5 μl of a 1:10 dilution of DNA template and TaKaRa SYBR Premix Taq (RR081A; Shiga, Japan) on a 7900HT fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY). The protocol was 1 cycle of 95°C for 30 s and 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 30 s. Primers (22) were UniF (ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGT) and UniR (ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGGC (IDT, Coralville, IA). A standard curve with E. coli DNA (700926D; ATCC, Manassas, VA) was used. Control samples of DNase I-treated H2O spiked with E. coli DNA showed no PCR inhibition. Only results above the lower range of detection in standard curve (150 CFU/ml) are reported. No-template controls (NTC) were included in all experiments.

Culture protocol.

Organisms were quantified in each sample in triplicate and identified using standard aerobic microbiological procedures (23) in blood, chocolate, mannitol salt, MacConkey, and Burkholderia cepacia selective agars (Remel Products, Lenexa, KS). Some identifications were confirmed by API 20E or API 20NE (bioMérieux) or Vitek (bioMérieux) analysis.

In vitro validation of DNase I treatment.

Strain SH1000 of Staphylococcus aureus was grown to log phase in tryptic soy broth (TSB) (211825; Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD). Cells were resuspended in 1% (vol/vol) TSB in H2O, followed by incubation with lysozyme (100 μg/ml) (L1667), lactoferrin (10 μg/ml) (L0520), human β-defensins 1 and 2 (25 ng/ml) (D9565 and D9690, respectively), and LL-37 (200 ng/ml) (94261; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 1 h at 37°C. DNase I treatment and bacterial quantification were performed as previously described. Data shown are representative of those from 4 different trials.

Microbiome analysis.

DNA for microbiome analysis was processed for sequencing in a Roche GS FLX 454 Titanium series instrument (454 Life Sciences, Branford, CT) at the University of Iowa DNA facility using standard protocols. Human Microbiome Project mock bacterial community (HM-278D; BEI Resources) was used as an additional quality control. BAL fluid and lung homogenate DNA samples were used in triplicate. The V1-2 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the FastStart high-fidelity PCR system (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Each 25-μl reaction mixture contained 25 ng of DNA template, 2.5 μl FastStart 10× buffer, 0.25 FastStart HiFi polymerase, 0.4 μM modified primer 8F (also referred to as 27F in some publications) (5′-CCTATCCCCTGTGTGCCTTGGCAGTCTCAGAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′, a composite of GS FLX Titanium primer B [underlined], a four-base library key [bold], and the universal bacterial primer 8F [italic]), and 0.4 μM modified primer 338R (5′-CCATCTCATCCCTGCGTGTCTCCGACTCAGNNNNNNNNNNNNTGCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT-3′, consisting of GS FLX Titanium primer A [underlined], a four-base library key [bold], a unique 12-base Golay-corrected barcode [Ns], and the broad-range bacterial primer 338R [italic]) (24). Ultramer primers were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) in a 96-well plate containing a set of 96 distinct barcoded primers. Cycling conditions were 94°C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 60°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 1 min. The size and quality of the resulting PCR products were confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Replicate PCR products were pooled and amplicons purified using Qiagen (Valencia, CA) MinElute columns. Subsequent steps for sequencing were performed following the manufacturer's recommended protocols.

We generated approximately 10,000 high-quality sequences per sample. Sequences were demultiplexed and analyzed using QIIME (25) in N3phele, a cloud-based environment (http://www.n3phele.com/). Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were generated using sequences with >97% similarity, and the RDP classification method was used to assign a taxonomic identity, based on the most current RDP database, to a representative sequence from each OTU. A taxonomy summary chart at the family level was used to generate heat maps showing the relative abundance of each OTU in each sample. Heat maps were made using GENE-E (Joshua Gould, Broad Institute) (http://www.broadinstitute.org/cancer/software/GENE-E/index.html).

Statistical procedures.

Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism 5 for MacOSX. The unpaired t test or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test (paired t test) was used as indicated. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant (26).

RESULTS

Bacterial DNA is abundant in the lungs.

Studies measuring the abundance and diversity of bacterial DNA in BAL fluid or protected specimen brush samples suggest the presence of bacterial communities in the lungs. Other studies in which lung samples obtained under sterile conditions have been cultured suggest that healthy lungs can be sterile.

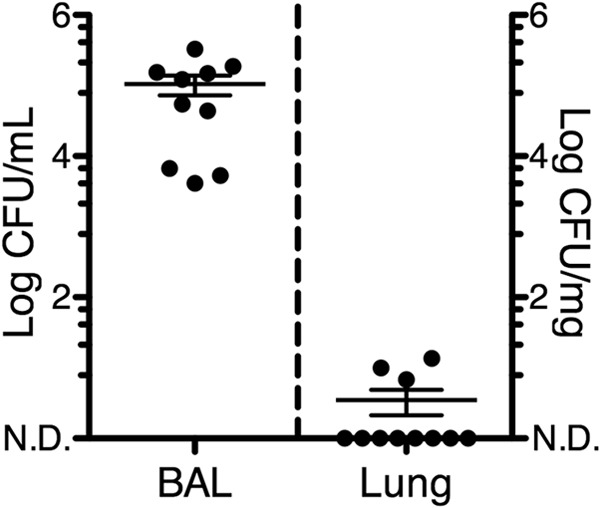

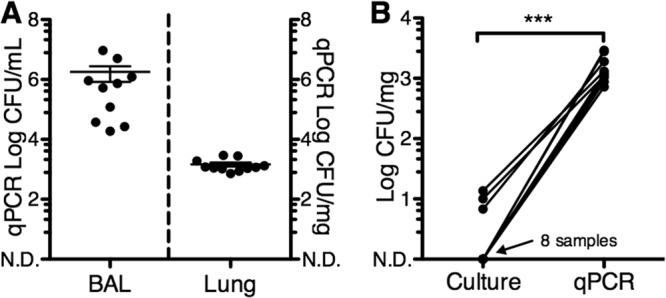

In order to quantify the abundance of culturable bacteria in the lungs, we performed aerobic cultures of right lower lobe transoral BAL fluid samples and lung homogenates from the lungs of healthy 6-week-old pigs (Fig. 1). We focused on aerobic conditions because the environment of a normal lung is considered mostly aerobic. While BAL fluid samples had a total average bacterial load of 1.05 × 105 ± 3.3 × 104 CFU/ml, we were unable to culture bacteria in 8 out of 11 lung homogenates. Next, to determine the total bacterial DNA loads in BAL fluid and lung homogenates, we performed qPCR using “universal” primers for the 16S rRNA gene of bacteria. BAL fluid samples had a total average qPCR bacterial DNA load of 1.79 × 106 ± 9.5 × 105 CFU/ml, more than 1 log higher than the culturable bacteria load. Moreover, lung homogenates had an average of 1.46 × 103 ± 2.2 × 102 CFU/ml (Fig. 2A). Bacteria were detected by qPCR in all samples, including samples with no culturable bacteria (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that the majority of bacteria present in the distal lungs cannot grow under the culture conditions used. However, an alternative hypothesis is that bacterial DNA in the lungs corresponds to dead bacteria.

Fig 1.

Quantification of bacteria in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and lung tissue by standard culture. BAL fluid samples and lung homogenates were incubated on multiple aerobic culture media, and isolates were identified with standard procedures. The total bacterial load (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]) is shown. n = 10 for BAL fluid samples and 11 for lung homogenates. Each symbol corresponds to a sample from an individual pig. N.D., nondetectable (<1 CFU/ml or CFU/mg).

Fig 2.

Quantification of bacteria in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and lung tissue by qPCR. (A) DNA was extracted from BAL fluid samples and lung homogenates and used for 16S rRNA qPCR using “universal” bacterial primers. Means ± SEMs are shown. (B) Comparison of total bacterial load by culture (CFU) and qPCR (CFU equivalents) in lung homogenate samples. n = 10 for BAL fluid samples and 11 for lung homogenates. N.D., nondetectable; ***, P < 0.001 (paired t test).

DNA from dead bacteria is DNase I sensitive.

Bacterial death results in increased permeability of the cell wall and eventual cell lysis (27). During the series of events leading to cell lysis, the internal components of bacterial cells become susceptible to interaction with the external environment. Bacterial DNA, which is normally inaccessible to extracellular enzymes, becomes susceptible to DNase from the host or from other bacteria (28–30). Therefore, DNA in live bacterial cells is mostly DNase resistant, while DNA from dead bacterial cells becomes DNase sensitive.

DNase I has been used to purify intact DNA in viruses with capsids and/or envelopes from mixtures containing DNase I-sensitive free and protein-associated DNA without a capsid (31). In the food industry, DNase-treated DNA PCR (DTD-PCR) has been used to detect DNA from live bacteria contaminating food accurately and with minimal cytotoxic effects on bacteria (32, 33). In order to determine whether bacterial DNA quantified with qPCR corresponded to intact or dead bacteria, we treated samples with DNase I and followed this with heat inactivation before cell lysis as the initial step for sample DNA extraction; comparison of treated and untreated samples would determine the ratio of DNA from intact bacteria to that from total bacteria.

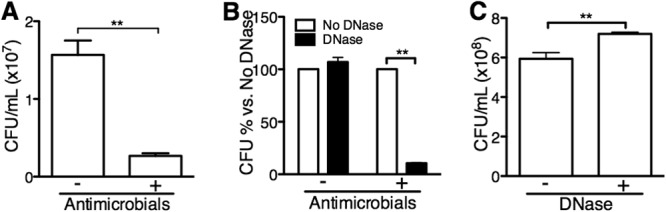

As proof of principle, we exposed cells of S. aureus to a combination of human antimicrobials, which resulted the in death of 83% of bacterial cells, as shown in Fig. 3A. Unexposed and exposed samples were then treated with DNase I before cell lysis during the DNA extraction process. In samples unexposed to antimicrobials, the total bacterial DNA load was unaffected by DNase I treatment. In contrast, bacterial death due to exposure to antimicrobials resulted in a decrease of 90% in total bacterial DNA load upon treatment with DNase I (Fig. 3B).

Fig 3.

DNase I treatment before cell lysis allows quantification of DNA from dead bacteria and from intact bacterial cells. S. aureus cells were treated with a combination of lysozyme, lactoferrin, and human β-defensins 1 and 2 for 1 h. (A and B) Bacterial quantification by culture (A) and by qPCR with and without DNase I treatment (B). (C) S. aureus quantification by culture with and without DNase I treatment. n = 6; **, P < 0.01 (unpaired t test).

To determine whether DNase I treatment directly results in bacterial death, we incubated S. aureus with DNase I and determined viability after incubation by dilution plating (Fig. 3C). DNase I treatment of S. aureus resulted in an increase of 15 to 20% in counts using the plate dilution method. This was not detectable when using qPCR (Fig. 3B, no antimicrobials). We speculate that this effect could be caused by DNase improving individual cell dispersion prior to plating, perhaps by dissolving biofilms, but this does not seem to enhance bacterial growth. We conclude that DNase treatment before cell lysis is not cytotoxic to bacteria and allows discernment of DNA of intact bacteria from that of dead bacteria and free bacterial DNA.

The majority of bacterial DNA in the lungs is DNase I sensitive.

In order to determine the load of DNA from live bacteria in the lungs, we used DNase I treatment before cell lysis followed by 16S rRNA qPCR in BAL fluid samples and compared them to lung homogenates from healthy pigs. Inhaled and aspirated bacteria are more likely to be present in the segments of the airways that are predominantly sampled by BAL than in the alveolar parenchyma (5). We hypothesized that the bacterial DNA obtained from BAL fluid samples would be a mixture of DNase I-sensitive and -resistant DNA, whereas bacterial DNA in lung tissue would be mostly DNase I sensitive.

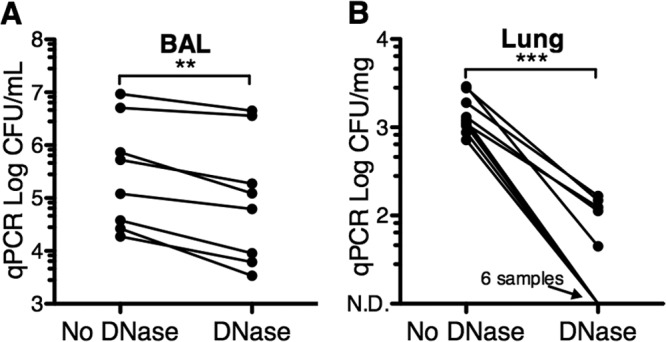

We found that all BAL fluid samples had a mixture of DNase I-sensitive and -resistant DNA, with DNase I treatment reducing the measured bacterial load in BAL fluid samples by 63%, to an average of 1.05 × 106 ± 6.5 × 105 CFU/ml (Fig. 4A). In 6 out of the 11 lung homogenates, all DNA was DNase I sensitive, suggesting the absence of live bacteria (Fig. 4B). On average, 94.4% of the bacterial DNA was DNase I sensitive in lung homogenates. We conclude that healthy pig lungs are mostly sterile and that most of the bacterial DNA in the lung parenchyma is from dead bacteria.

Fig 4.

DNase I treatment reveals that bacterial DNA in the lungs is predominantly from dead bacteria. DNA was extracted from BAL fluid samples and lung homogenates after DNase I or buffer control treatment before cell lysis. Bacterial quantification was performed with 16S rRNA qPCR (CFU equivalents) using “universal” bacterial primers. n = 8 for BAL fluid and 11 for lung homogenate samples; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01 (paired t test). N.D., nondetectable.

Abundant bacteria in airways sampled by BAL are similar to those in the oral cavity.

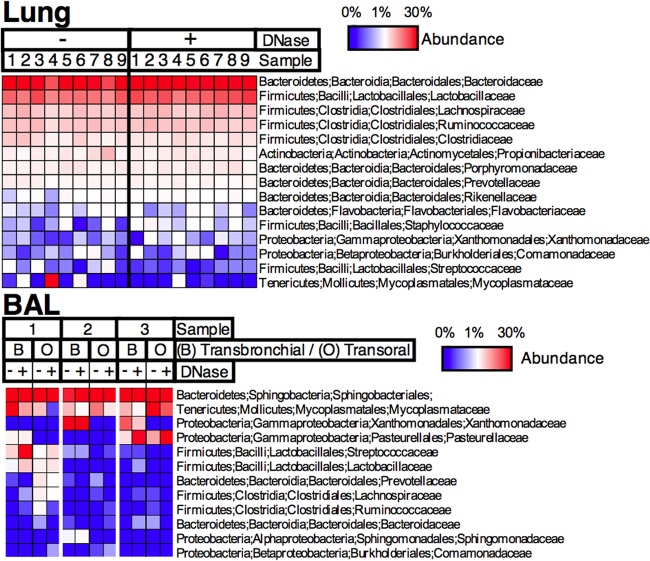

We asked whether bacteria in lung parenchyma and airways sampled by BAL would approximate those in the oral cavity and upper airways (Fig. 5). We therefore used 16S rRNA gene high-throughput sequencing to identify bacterial taxa present in both DNase I-treated and untreated airway samples. We compared BAL fluid samples obtained transorally to samples obtained previously from the same bronchi using a transbronchial approach and therefore bypassing the mouth and contamination from the upper airways. We found that bacteria in transbronchial BAL fluid samples were similar to those in transoral BAL fluid samples, with clear dominance from bacteria in the Sphingobacteriales order and Mycoplasmataceae, Xanthomonadaceae, and Pasteurellaceae families and with some samples containing abundant Streptococcaceae and Lactobacillaceae, among others. This suggests that, as suggested by work in humans by Charlson et al. (5), bacterial diversity in the airways is similar to that in the oral cavity and upper airways.

Fig 5.

Bacterial diversity in lung homogenates. Lung homogenates were treated with DNase I or buffer control before cell lysis, followed by DNA extraction. Bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences were amplified and used to determine bacterial diversity. Columns in the heat map show samples, and rows show OTU taxonomy assignment (phylum; class; order; family).

Similar bacterial taxa detected in lung DNase I-sensitive and resistant bacterial DNA.

The presence of a small amount of DNase I-resistant DNA in some but not all of the lung homogenate samples may represent a community of symbiotic bacteria. We hypothesized that DNase I-resistant DNA would show an overrepresentation of specific taxa compared to DNase I-untreated samples. This would be consistent with a model in which most inhaled and aspirated bacteria are killed except for those able to survive the longest in the lungs, perhaps as symbionts. Alternatively, it could mean that the sensitivity or availability of DNA from dead bacteria is variable according to species.

We found that in samples in which bacteria were detectable by qPCR, most 16S rRNA gene sequences corresponded to the Bacteroidaceae, Lactobacillaceae, Lachnospiraceae, and Ruminococcaceae families, with similar proportions in DNase-treated and untreated samples (Fig. 5, lung). Interestingly, the bacteria were mostly different from those found in the BAL fluid samples. These data suggest that no specific taxa survive longer than others in the lungs and either that there is a small number of unselected bacteria surviving in the lungs or that all bacteria are being killed by antimicrobial mechanisms, the endpoint of which would normally be sterility.

DISCUSSION

A primary goal of our work was to resolve the discrepancy between the long-standing dogma that dictates that the lungs are sterile and recent data using DNA sequencing-based methodology that suggest abundant and diverse bacterial communities in the healthy lungs. The answer to this long-standing problem has been elusive (4, 34, 35), partly due to the difficulty in sampling the lower airways while avoiding contamination of the sampling device in the mouth and because of aspiration and the communication between the airways and the oral cavity (1–3, 15–20, 36).

Our results suggest that most of the detectable bacterial DNA in the lung parenchyma is DNase I sensitive and corresponds to dead bacteria. Therefore, lung parenchyma is most likely normally sterile or in a constant process of sterilization. In contrast, bacterial DNA in airways sampled by BAL is a mixture of DNA from both live and dead bacteria. Interestingly, bacteria in lung parenchyma (low abundance) are different from those in BAL fluid samples (high abundance). This could mean that some bacteria are able to reach the lung parenchyma better or that they are able to survive antimicrobial mechanisms in the distal lungs (alveolar products, etc.) better than others. Whether they are actually symbionts is still open to exploration, but our data would suggest that if they were, they would survive at a very low absolute abundance and not in all lungs. Additionally, it is possible that dead bacteria that have not been lysed might exist within the lungs (14). This would result in a false-positive group of bacteria that are detectable by qPCR/16S rRNA sequencing even after DNase I treatment but which would be undetectable by culture and thus contribute to erroneously increasing diversity in the sample. Current DNA sequencing-based methods of bacterial diversity analysis may therefore overestimate the bacterial load and diversity in BAL fluid or bronchial brush samples.

A limitation in our study is that we analyzed exclusively samples from pigs. Lung parenchyma samples in humans could be obtained during surgical procedures involving the chest cavity, but these would most likely correspond to sick lungs, and it may be very difficult to simultaneously obtain BAL fluid samples for comparison. Nevertheless, others have gained important insight into the role of the lung microbiome by analyzing explanted human lungs (36–38). Alternatively, focusing on the immune response to the lung microbiome would overcome some of these limitations (39, 40).

Although there is some intrinsic DNase activity in the airway surface (41), DNA can remain in the lungs for a significant time under certain conditions. A dramatic example is that of cystic fibrosis, where a significant proportion of mucus and mucopurulent secretions is associated with DNA (42). In this case, exogenous DNase is actually used as a therapeutic agent that results in decreased mucus viscosity and improved pulmonary function (43–45). We speculate that constant exposure to bacteria results in some constant levels of DNase-sensitive bacterial DNA in the lungs.

Free bacterial DNA in the lungs may play a role in preventing bacterial infections by stimulating Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) (46) or by another, as-yet-uncharacterized mechanism. In addition, we speculate that analysis of bacterial DNA in the lungs can yield insight into the patterns of bacterial exposure in different environments. In a clinical setting, analyzing the proportion of DNase I-resistant DNA of total DNA from a specific bacterial species in pulmonary infections may allow determination of whether an adequate response to antibiotic treatment occurred, particularly in cases in which culture of the pathogen becomes difficult due to the presence of antibiotics in the sample.

This work facilitates analysis of changes in the lung microbiome in diseases such as COPD, cystic fibrosis, and asthma. Applying the methodology described here to distinguish between lung bacteria that have been killed by airway antimicrobials and those that colonize the airways will allow a better understanding of the roles of these bacterial communities in human lungs. Moreover, this approach can easily be generalized to analyze the microbiomes of samples from any organ or environment and may improve the capacity to understand active symbiotic bacterial communities and their role in health and disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michael J. Welsh, Paul B. McCray, Jr., and Douglas B. Hornick for insightful discussion. We also thank Peter J. Taft, Paula S. Ludwig, Alexander J. Tucker, Krista R. Young, and Kelli Mohn for excellent technical support.

This work was internally funded by the Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine.

We have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 July 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Jager E, Ruden H, Zeschmar-Lahl B. 1994. Composting facilities. 2. Aerogenic microorganism content at different working areas of composting facilities. Zentralbl. Hyg. Umweltmed. 196:367–379 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai FC, Macher JM. 2005. Concentrations of airborne culturable bacteria in 100 large US office buildings from the BASE study. Indoor Air 15:71–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johanson WG, Pierce AK, Sanford JP. 1969. Changing pharyngeal bacterial flora of hospitalized patients. Emergence of gram-negative bacilli. N. Engl. J. Med. 281:1137–1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones FS. 1922. The source of the microorganisms in the lungs of normal animals. J. Exp. Med. 36:317–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charlson ES, Bittinger K, Haas AR, Fitzgerald AS, Frank I, Yadav A, Bushman FD, Collman RG. 2011. Topographical continuity of bacterial populations in the healthy human respiratory tract. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 184:957–963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erb-Downward JR, Thompson DL, Han MK, Freeman CM, McCloskey L, Schmidt LA, Young VB, Toews GB, Curtis JL, Sundaram B, Martinez FJ, Huffnagle GB. 2011. Analysis of the lung microbiome in the “healthy” smoker and in COPD. PLoS One 6:e16384. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilty M, Burke C, Pedro H, Cardenas P, Bush A, Bossley C, Davies J, Ervine A, Poulter L, Pachter L, Moffatt MF, Cookson WO. 2010. Disordered microbial communities in asthmatic airways. PLoS One 5:e8578. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox MJ, Allgaier M, Taylor B, Baek MS, Huang YJ, Daly RA, Karaoz U, Andersen GL, Brown R, Fujimura KE, Wu B, Tran D, Koff J, Kleinhenz ME, Nielson D, Brodie EL, Lynch SV. 2010. Airway microbiota and pathogen abundance in age-stratified cystic fibrosis patients. PLoS One 5:e11044. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao J, Schloss PD, Kalikin LM, Carmody LA, Foster BK, Petrosino JF, Cavalcoli JD, Vandevanter DR, Murray S, Li JZ, Young VB, Lipuma JJ. 2012. Decade-long bacterial community dynamics in cystic fibrosis airways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:5809–5814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang YJ, Kim E, Cox MJ, Brodie EL, Brown R, Wiener-Kronish JP, Lynch SV. 2010. A persistent and diverse airway microbiota present during chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. OMICS 14:9–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang YJ, Nelson CE, Brodie EL, Desantis TZ, Baek MS, Liu J, Woyke T, Allgaier M, Bristow J, Wiener-Kronish JP, Sutherland ER, King TS, Icitovic N, Martin RJ, Calhoun WJ, Castro M, Denlinger LC, Dimango E, Kraft M, Peters SP, Wasserman SI, Wechsler ME, Boushey HA, Lynch SV. 2011. Airway microbiota and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in patients with suboptimally controlled asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 127:372–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klepac-Ceraj V, Lemon KP, Martin TR, Allgaier M, Kembel SW, Knapp AA, Lory S, Brodie EL, Lynch SV, Bohannan BJ, Green JL, Maurer BA, Kolter R. 2010. Relationship between cystic fibrosis respiratory tract bacterial communities and age, genotype, antibiotics and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ. Microbiol. 12:1293–1303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willner D, Haynes MR, Furlan M, Schmieder R, Lim YW, Rainey PB, Rohwer F, Conrad D. 2012. Spatial distribution of microbial communities in the cystic fibrosis lung. ISME J. 6:471–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein DA. 2011. Bulk extraction-based microbial ecology: three critical questions. Microbe 6:377 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chastre J, Fagon JY, Domart Y, Gibert C. 1989. Diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia in intensive care unit patients. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 8:35–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torres A, el-Ebiary M, Padro L, Gonzalez J, de la Bellacasa JP, Ramirez J, Xaubet A, Ferrer M, Rodriguez-Roisin R. 1994. Validation of different techniques for the diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Comparison with immediate postmortem pulmonary biopsy. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 149:324–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heyland D, Ewig S, Torres A. 2002. Pro/con clinical debate: the use of a protected specimen brush in the diagnosis of ventilator associated pneumonia. Crit. Care 6:117–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torres A, Puig de la Bellacasa J, Xaubet A, Gonzalez J, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Jimenez de Anta MT, Agusti Vidal A. 1989. Diagnostic value of quantitative cultures of bronchoalveolar lavage and telescoping plugged catheters in mechanically ventilated patients with bacterial pneumonia. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 140:306–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chastre J, Fagon JY, Soler P, Bornet M, Domart Y, Trouillet JL, Gibert C, Hance AJ. 1988. Diagnosis of nosocomial bacterial pneumonia in intubated patients undergoing ventilation: comparison of the usefulness of bronchoalveolar lavage and the protected specimen brush. Am. J. Med. 85:499–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chastre J, Viau F, Brun P, Pierre J, Dauge MC, Bouchama A, Akesbi A, Gibert C. 1984. Prospective evaluation of the protected specimen brush for the diagnosis of pulmonary infections in ventilated patients. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 130:924–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Busse WW, Wanner A, Adams K, Reynolds HY, Castro M, Chowdhury B, Kraft M, Levine RJ, Peters SP, Sullivan EJ. 2005. Investigative bronchoprovocation and bronchoscopy in airway diseases. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 172:807–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amann RI, Binder BJ, Olson RJ, Chisholm SW, Devereux R, Stahl DA. 1990. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1919–1925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray PR, Baron EK, Jorgensen JH, Landry ML, Pfaller MA. (ed). 2007. Manual of clinical microbiology, 9th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fierer N, Hamady M, Lauber CL, Knight R. 2008. The influence of sex, handedness, and washing on the diversity of hand surface bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:17994–17999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. 2010. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7:335–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Motulsky H. 1995. Intuitive biostatistics. Oxford University Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rice KC, Bayles KW. 2008. Molecular control of bacterial death and lysis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72:85–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulcahy H, Charron-Mazenod L, Lewenza S. 2010. Pseudomonas aeruginosa produces an extracellular deoxyribonuclease that is required for utilization of DNA as a nutrient source. Environ. Microbiol. 12:1621–1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nijland R, Hall MJ, Burgess JG. 2010. Dispersal of biofilms by secreted, matrix degrading, bacterial DNase. PLoS One 5:e15668. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tetz VV, Tetz GV. 2010. Effect of extracellular DNA destruction by DNase I on characteristics of forming biofilms. DNA Cell Biol. 29:399–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allander T, Emerson SU, Engle RE, Purcell RH, Bukh J. 2001. A virus discovery method incorporating DNase treatment and its application to the identification of two bovine parvovirus species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:11609–11614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahesha L, Sigera NN, Rakshit SK. 2007. The effect of DNaseI enzyme on food pathogens subjected to different food processing treatments. J. Natl. Sci. Found. Sri Lanka 35:167–173 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mukhopadhyay UK, Mukhopadhyay A. 2002. A low-cost, rapid, sensitive and reliable PCR-based alternative method for predicting the presence of possible live microbial contaminants in food. Curr. Sci. 83:53–56 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dickson RP, Erb-Downward JR, Huffnagle GB. 2013. The role of the bacterial microbiome in lung disease. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 7:245–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang YJ, Charlson ES, Collman RG, Colombini-Hatch S, Martinez FD, Senior RM. 2013. The role of the lung microbiome in health and disease. A National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop report. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 187:1382–1387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goddard AF, Staudinger BJ, Dowd SE, Joshi-Datar A, Wolcott RD, Aitken ML, Fligner CL, Singh PK. 2012. Direct sampling of cystic fibrosis lungs indicates that DNA-based analyses of upper-airway specimens can misrepresent lung microbiota. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:13769–13774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borewicz K, Pragman AA, Kim HB, Hertz M, Wendt C, Isaacson RE. 2013. Longitudinal analysis of the lung microbiome in lung transplantation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 339:57–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sze MA, Dimitriu PA, Hayashi S, Elliott WM, McDonough JE, Gosselink JV, Cooper J, Sin DD, Mohn WW, Hogg JC. 2012. The lung tissue microbiome in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 185:1073–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larsen JM, Steen-Jensen DB, Laursen JM, Sondergaard JN, Musavian HS, Butt TM, Brix S. 2012. Divergent pro-inflammatory profile of human dendritic cells in response to commensal and pathogenic bacteria associated with the airway microbiota. PLoS One 7:e31976. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Segal LN, Alekseyenko AV, Clemente JC, Kulkarni R, Wu B, Chen H, Berger KI, Goldring RM, Rom WN, Blaser MJ, Weiden MD. 2013. Enrichment of lung microbiome with supraglottic taxa is associated with increased pulmonary inflammation. Microbiome 1:19. 10.1186/2049-2618-1-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenecker J, Naundorf S, Rudolph C. 2009. Airway surface liquid contains endogenous DNase activity which can be activated by exogenous magnesium. Eur. J. Med. Res. 14:304–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lethem MI, James SL, Marriott C, Burke JF. 1990. The origin of DNA associated with mucus glycoproteins in cystic fibrosis sputum. Eur. Respir. J. 3:19–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones AP, Wallis C. 2010. Dornase alfa for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 17:CD001127. 10.1002/14651858.CD001127.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Konstan MW, Wagener JS, Pasta DJ, Millar SJ, Jacobs JR, Yegin A, Morgan WJ. 2011. Clinical use of dornase alpha is associated with a slower rate of FEV1 decline in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 46:545–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shak S, Capon DJ, Hellmiss R, Marsters SA, Baker CL. 1990. Recombinant human DNase I reduces the viscosity of cystic fibrosis sputum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:9188–9192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knuefermann P, Baumgarten G, Koch A, Schwederski M, Velten M, Ehrentraut H, Mersmann J, Meyer R, Hoeft A, Zacharowski K, Grohe C. 2007. CpG oligonucleotide activates Toll-like receptor 9 and causes lung inflammation in vivo. Respir. Res. 8:72. 10.1186/1465-9921-8-72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]