Abstract

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is an important pathogen that probably survives well in the modern food chain. However, little is known about the mechanisms that allow the growth of this pathogen in foods under stress conditions. The expression of rpoE encoding σE was defined by quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR. Expression of rpoE was induced at 3°C, 37°C, and 42°C, under exposure to 3% NaCl, 3% ethanol, or high and low pH, in relation to its expression at the optimum growth temperature of 28°C of Y. pseudotuberculosis. Mutation of rpoE either impaired or abolished growth under stresses caused by low or high temperature, low pH, and ethanol. In addition, the growth temperature range of the mutant was significantly diminished compared to that of the wild-type strain IP32953. The results were confirmed with complementation of the mutant. Thus, σE plays a significant role in the stress tolerance of Y. pseudotuberculosis IP32953 and probably contributes to the survival of this pathogen in the food chain.

INTRODUCTION

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is an important food-borne Gram-negative pathogen that has caused several outbreaks through raw vegetables or contaminated water (1–5). The average incidence of Y. pseudotuberculosis infections between the years 1995 and 2006 in Finland was 1.9/100,000 population (varied between 0.6 and 4.8) (6). Y. pseudotuberculosis tolerates stressful conditions in the environment and in the modern food chain. It is able to survive over winter in soil (2) and at least 1 month in food storage facilities (1), and it can grow in pHs ranging from 5.0 to 9.6, at temperatures from 0 to 42°C (7), and in a NaCl concentration of 5% (6).

The mechanisms that allow survival and growth of Y. pseudotuberculosis under stressful conditions are poorly understood (7). It is known that the histidine kinase CheA of the CheA/CheY two-component system (8) and the RNA helicase CsdA (9) are needed for optimal growth of Y. pseudotuberculosis at low temperature. The role of alternative sigma factors in counteracting environmental stresses has been elucidated for many other food pathogens (10–13), but their role in Y. pseudotuberculosis is not known. Understanding the means bacteria use to tolerate stress can provide new ways to control the growth of pathogens in foods.

The envelope of Gram-negative bacteria consists of the cell membrane, periplasm, and the outer membrane. The alternative sigma factor σE controls the composition and folding of proteins in the cell envelope (14). Heat (15), increased expression (14), unfolding or misfolding of the outer membrane proteins (16), ethanol (17), and high osmolality (18) induce σE-dependent envelope stress response (reviewed in references 19 and 20). The most important regulator of σE activity is the inner membrane protein RseA, which is an anti-sigma factor (21, 22). Under nonstress conditions, σE is bound by RseA and activity of σE is thus inhibited (21, 22). In the σE-dependent envelope stress response, σE is released from its anti-sigma factor by proteases (16, 23–30). This leads to transcription of several genes involved in protein delivery, assembly, and degradation in order to restore normal protein folding and reset the σE-dependent envelope stress response (19).

To our knowledge, there are no studies on the roles of σE under stress in Y. pseudotuberculosis. In Escherichia coli, expression of rpoE encoding σE is induced by low temperature (31). In this investigation, we studied the expression of rpoE and the role of σE under different stress conditions in Y. pseudotuberculosis. We show that σE is needed at both low and high temperatures and under stresses caused by low pH and ethanol in Y. pseudotuberculosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Y. pseudotuberculosis strain IP32953 (gratefully received from Elisabeth Carniel, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) and an E. coli strain comparable to DH5α (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO), having recA1 and endA1 mutations, were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar. Y. pseudotuberculosis was incubated at 28°C and E. coli at 37°C with shaking.

RNA isolation.

RNA isolation was performed as described previously (8). In brief, three biological replicates originating from separate colonies were grown in LB broth at 28°C and 3°C, in LB broth with 5 mM CaCl2 at 28°C, 37°C, and 42°C to inhibit the release of Yersinia outer membrane proteins (32), and in LB broth at pH 5.0 (adjusted with 1 M HCl), at pH 9.0 (adjusted with 1 M NaOH), with 3% NaCl, or with 3% ethanol at 28°C. Samples were taken at early (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 0.5 to 0.8) and late (OD600, 1.1 to 2.2) logarithmic growth phases. During total RNA isolation using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany), on-column DNase digestion was done by following the manufacturer's instructions. A DNA-free kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used for an additional DNase treatment. The A260/A280 ratio was measured with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA), and the integrity of RNA was investigated with the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA).

Reverse transcription and RT-qPCR.

Reverse transcription and quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-qPCR) were done as described previously (8). In short, reverse transcription of the RNAs into cDNAs was done in duplicate (reverse transcription replicates) by using the Dynamo cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The Dynamo Flash SYBR green qPCR kit (Thermo Scientific) was used in RT-qPCR by following the manufacturer's instructions. The total reaction volume of 20 μl contained 4 μl of template cDNA and a 0.5 μM concentration of each primer, designed with the Primer3 software (33, 34) (Table 1). The cycling protocol of Rotor-Gene 3000 (Qiagen) included initial denaturation at 95°C for 7 min, 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 s, annealing at 60°C for 15 s, and extension at 72°C for 20 s, with a final extension at 60°C for 1 min. After each extension step, fluorescence data were acquired. A melt curve after a temperature upshift from 60°C to 98°C (0.5°C/5 s) was analyzed after each run. The amplification reaction efficiencies for each primer pair were defined with dilution series of pooled cDNA. The Rotor-Gene 3000 software was used to set the threshold fluorescence levels for each primer pair and to calculate the reaction efficiencies as , where M is the slope of the straight line from a semilogarithmic plot of the quantification cycle (Cq) as a function of the cDNA concentration. Reaction efficiencies of rpoE (locus tag YPTB2897) RT-qPCR primers under different stresses are shown in Table 2. The relative expression levels of rpoE under different stresses were normalized to 16S rrn, calibrated to samples taken at 28°C, and quantified by calculating the expression ratios (R) using the equation

| (1) |

(35), where ErpoE is the amplification reaction efficiency of the rpoE transcript, E16Srrn is the amplification reaction efficiency of 16S rrn transcripts, ΔCq,rpoE is the Cq deviation between calibrator and sample for the rpoE transcript, and ΔCq,16Srrn is the Cq deviation between calibrator and sample for the 16S rrn transcripts. Samples collected at 37°C and 42°C were calibrated to samples grown at 28°C with 5 mM CaCl2. Student's t test was used to investigate the significance of the differences between the relative expression levels of rpoE under different growth conditions.

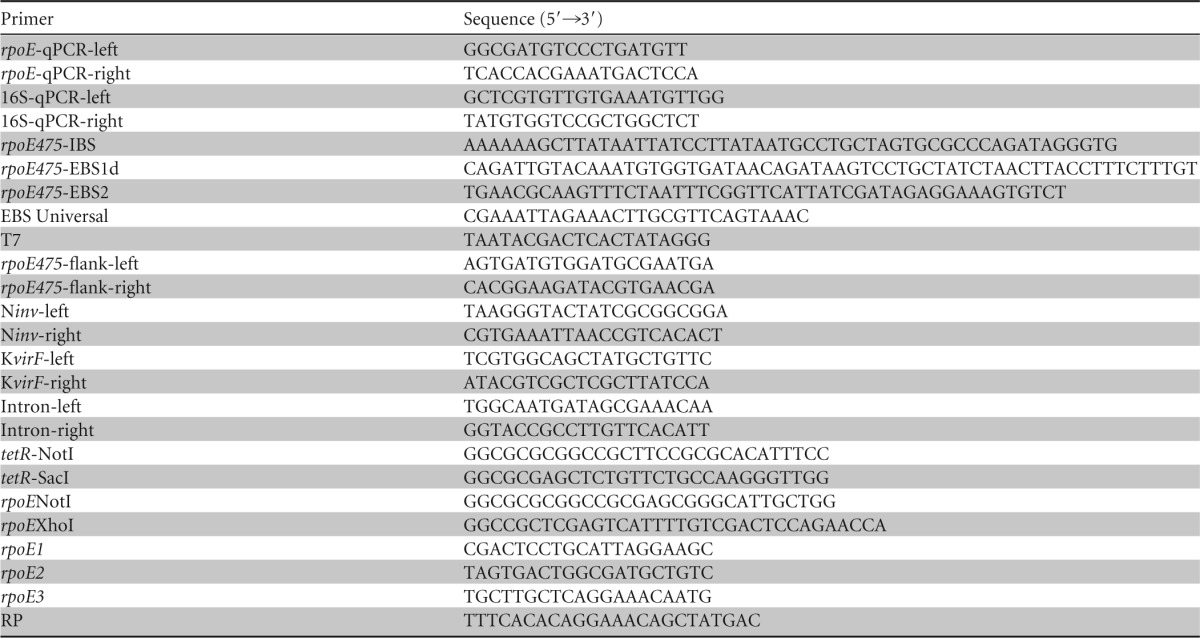

Table 1.

Primers used in this study

Table 2.

Reaction efficiencies, average quantification cycle () values, average expression ratios calibrated to 28°C, and standard deviations of average expression ratios of rpoE under different stress conditions at the early and late logarithmic growth phasesac

| Condition | E | Early logarithmic growth phase |

Late logarithmic growth phase |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | c | SD (R) | P value | b | c | SD (R) | P value | ||

| 3°C | 0.86 | 14.17 | 3.2 | 0.6 | 0.007 | 15.02 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 0.184 |

| 37°C | 0.95 | 15.28 | 2.2 | 0.3 | 0.011 | 16.21 | 2.2 | 0.4 | 0.008 |

| 42°C | 0.99 | 14.27 | 3.9 | 0.4 | 0.002 | 16.24 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 0.035 |

| pH 5.0 | 1.01 | 18.43 | 13.0 | 4.3 | 0.007 | 20.74 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 0.235 |

| pH 9.0 | 0.90 | 19.17 | 3.9 | 0.6 | 0.005 | 21.22 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.599 |

| 3% NaCl | 0.97 | 20.01 | 7.2 | 1.6 | 0.004 | 22.22 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.737 |

| 3% ethanol | 0.94 | 16.85 | 8.5 | 3.0 | 0.010 | 16.65 | 13.1 | 13.4 | 0.102 |

E, reaction efficiencies; R, average expression ratios.

Average of the reverse transcription replicates, PCR replicates, and biological replicates.

, where .

Mutagenesis.

An rpoE475-476::Ltr Kanr mutant (hereafter called rpoE475) was constructed by using the TargeTron gene knockout system (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) according to the manufacturer's instructions as reported earlier (8). Primers (Table 1) were designed with the Primer3 software (33, 34) or generated using the TargeTron algorithm (Sigma-Aldrich Co.). Primers rpoE475-IBS, rpoE475-EBS1d, rpoE475-EBS2, and EBS Universal (Table 1) were used in PCR to retarget the RNA segment of the intron. The PCR product was subsequently ligated into the plasmid pACD4K-C (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) and transformed to E. coli by heat shock. Correct retargeting of the intron in an antisense orientation in rpoE was verified by sequencing with T7 primer (Table 1). Y. pseudotuberculosis IP32953 was made electrocompetent as described previously (36), and plasmid pAR1219 (Sigma-Aldrich Co.), a source of T7 RNA polymerase, was introduced into Y. pseudotuberculosis IP32953 by electroporation using 0.1-cm cuvettes with 25 μF, 200 Ω, and 1.8 kV. After electroporation, cells were incubated in superoptimal broth with catabolite repression (SOC) for 3 h and plated on LB agar containing 100 μg/ml of ampicillin. Y. pseudotuberculosis IP32953 containing pAR1219 was made competent, and pACD4K-C was introduced in this strain by electroporation. After incubation for 3 h in SOC, incubation was continued overnight in LB broth containing 100 μg/ml of ampicillin and 25 μg/ml of chloramphenicol. The culture was diluted (1:50) in fresh LB broth containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol and grown to an OD600 of 0.2. Intron expression and insertion were induced by adding 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside and continuing incubation overnight. Cells were centrifuged, resuspended in fresh LB broth, incubated for 3 h, and plated on LB agar containing 50 μg/ml of kanamycin. Insertion was confirmed by PCR using primer pairs rpoE-flank-left and rpoE-flank-right and rpoE-flank-right and EBS Universal (Table 1). To confirm the species Y. pseudotuberculosis and the presence of the virulence plasmid pYV, primer pairs Ninv-left and Ninv-right (37) and KvirF-left and K-virF-right (38), respectively, were used in PCR (Table 1).

Southern blotting.

Single-intron insertion in the mutant genome was confirmed by Southern blotting as reported earlier (8). Briefly, a 199-bp digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probe was synthesized using a PCR DIG probe synthesis kit (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions using primers intron-left and intron-right (34) (Table 1). Genomic DNA was isolated from the wild-type and mutant strains. HindIII-digested DNAs and pACD4K-C were transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane and hybridized with the probe as recommended by the manufacturer.

Complementation of the rpoE mutant strain.

The tetracycline resistance gene in pBR322 (39) was amplified by PCR with primers tetR-NotI and tetR-SacI (Table 1). The PCR product and pBluescript II KS+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) were digested with NotI and SacI and ligated, yielding pBluescript-tetR (hereafter called pBlue-tetR). A 2,713-bp region of the chromosome of Y. pseudotuberculosis IP32953 (33), containing the coding sequences of rpoE, rseA, and rseB, and 500 bp upstream of the start codon of rpoE were amplified by PCR using primers rpoENotI and rpoEXhoI (Table 1). The resulting PCR product and pBlue-tetR were digested with NotI and XhoI and ligated, producing pBlue-tetR-rpoE. The correct sequence of pBlue-tetR-rpoE was confirmed by sequencing with T7, rpoE1, rpoE2, rpoE3, rpoE475-flank-left, and RP primers (Table 1). The rpoE475 mutant was cured of pAR1219 by being subcultured several times in LB broth without ampicillin. The ampicillin-sensitive clone of rpoE475 was confirmed with primers rpoE-flank-left and rpoE-flank-right for the presence of the intron and with primers Ninv (37) and KvirF (38) for the species Y. pseudotuberculosis and the presence of the pYV, respectively (Table 1). pBlue-tetR (vector control) and pBlue-tetR-rpoE were introduced into the rpoE475 mutant by electroporation and plated on LB containing 100 μg/ml of ampicillin. The presence of pBlue-tetR-rpoE in the mutant was confirmed by PCR with primers T7 and rpoE-flank-right (Table 1). The vector control and the complemented mutant carrying pBlue-tetR-rpoE were confirmed with primers rpoE-flank-left and rpoE-flank-right and with primers Ninv (37) and KvirF (38) (Table 1).

Growth experiments.

Three separate colonies of the Y. pseudotuberculosis IP32953 wild-type strain, the rpoE475 mutant, and the rpoE475 mutant with pBlue-tetR-rpoE or pBlue-tetR were individually inoculated into fresh LB broth containing 200 μg/ml of ampicillin when appropriate and grown overnight with shaking. To study growth at 3°C, 28°C, 37°C, and 42°C, cultures were diluted (1:100) into fresh LB broth containing ampicillin when appropriate. For experiments at 37°C and 42°C, LB broth was supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 to inhibit the release of Yersinia outer membrane proteins (32). To study growth at 28°C under pH, salt, or ethanol stress, cultures were diluted (1:100) into LB broth adjusted to pH 5.0 (with 1 M HCl) or pH 9.0 (with 1 M NaOH) or containing NaCl 30 g/liter or ethanol 3%, plus ampicillin when appropriate. A quantity of 300 μl of each dilution was pipetted into wells of microtiter plates in triplicate. The plates were placed in the turbidity reader Bioscreen C MBR (Oy Growth Curves Ab, Helsinki, Finland). Turbidity of the cultures was monitored at 15-min intervals, or at 1-h intervals at 3°C, with agitation of the culture before each measurement. Growth curves were constructed by plotting the OD600 values against time. Correspondence between OD600 values and the number of viable bacteria of the wild type and rpoE475, rpoE475+pBlue-tetR-rpoE, and rpoE475+pBlue-tetR was verified in duplicate by inoculating 1 ml of an overnight culture grown at 28°C into 100 ml of LB or LB supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 (32), 3% NaCl, 3% ethanol, or ampicillin or with pH adjusted to 5.0 or 9.0. Bacteria were grown at 3°C, 28°C, 37°C, and 42°C with shaking, and OD600 and CFU/ml were determined immediately and during the growth by plating on plate count agar.

Minimum and maximum growth temperatures.

The minimum and maximum growth temperatures of the wild-type strain, the rpoE475 mutant, the complemented mutant, and the vector control were defined by using the Gradiplate W10 temperature gradient incubator (BCDE Group, Helsinki, Finland) as described previously (40), with some modifications. In brief, overnight cultures in LB broth, containing ampicillin when appropriate, originating from three separate colonies (biological replicates) were diluted 1:100 in peptone water and transferred by stamping with a piece of glass to cuvettes containing tryptic soy agar with either 1.5% (minimum growth temperature run) or 2.5% (maximum growth temperature run) agar supplemented with ampicillin when appropriate. The cuvettes were placed in the Gradiplate incubator for 10 days for measuring the minimum growth temperatures, and for 2 days for measuring the maximum growth temperatures, under aerobic conditions. The temperature gradient was set to range from 0.8°C to 9.5°C for minimum growth temperature determinations and from 29.7°C to 44.6°C for maximum growth temperature determinations. Limits of growth were detected with a Nikon SMZ-U stereomicroscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and set to the boundary of growth and no growth. Student's t test was used to evaluate the significance of differences between growth temperatures.

RESULTS

RNA isolation and stability of 16S rrn.

The integrity of RNA was negatively affected by sodium chloride. Other stresses did not have substantial effects on RNA integrity. Stability of the 16S rrn, used as a normalization reference in the RT-qPCR analysis of rpoE, and the reaction efficiencies of the 16S rrn primers are reported in Table 3. The expression of 16S rrn was generally stable, and the coefficient of variance as a percentage of the Cq value varied between 1.52 and 6.82.

Table 3.

Stability of the reference gene 16S rrn at different stress conditions at early and late logarithmic growth phases in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP32953

| Parameters | Value at: |

Ea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early logarithmic growth phase | Late logarithmic growth phase | Both growth phases | ||

| 3°C and 28°C | 1.05 | |||

| Arithmetic mean (Cq) | 16.91 | 17.00 | 16.96 | |

| Geometric mean (Cq) | 16.90 | 17.00 | 16.95 | |

| Avg deviation | 0.63 | 0.30 | 0.46 | |

| CV (% Cq)b | 3.89 | 2.00 | 3.10 | |

| 37°C and 28°C | 0.94 | |||

| Arithmetic mean (Cq) | 18.40 | 18.27 | 18.34 | |

| Geometric mean (Cq) | 18.40 | 18.26 | 18.33 | |

| Avg deviation | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.24 | |

| CV (% Cq)b | 1.60 | 1.23 | 1.48 | |

| 42°C and 28°C | 0.95 | |||

| Arithmetic mean (Cq) | 17.83 | 17.64 | 17.74 | |

| Geometric mean (Cq) | 17.83 | 17.63 | 17.73 | |

| Avg deviation | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.27 | |

| CV (% Cq)b | 1.52 | 2.08 | 1.90 | |

| pH 5.0 and 28°C | 1.04 | |||

| Arithmetic mean (Cq) | 13.97 | 13.84 | 13.90 | |

| Geometric mean (Cq) | 13.96 | 13.82 | 13.89 | |

| Avg deviation | 0.35 | 0.53 | 0.44 | |

| CV (% Cq)b | 2.84 | 4.28 | 3.65 | |

| pH 9.0 and 28°C | 0.93 | |||

| Arithmetic mean (Cq) | 18.38 | 18.13 | 18.25 | |

| Geometric mean (Cq) | 18.36 | 18.11 | 18.24 | |

| Avg deviation | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.73 | |

| CV (% Cq)b | 4.07 | 4.35 | 4.26 | |

| 3% NaCl and 28°C | 0.94 | |||

| Arithmetic mean (Cq) | 18.98 | 18.48 | 18.73 | |

| Geometric mean (Cq) | 18.94 | 18.45 | 18.69 | |

| Avg deviation | 1.29 | 1.04 | 1.16 | |

| CV (% Cq)b | 6.85 | 5.78 | 6.49 | |

| 3% ethanol and 28°C | 0.95 | |||

| Arithmetic mean (Cq) | 17.91 | 17.78 | 17.85 | |

| Geometric mean (Cq) | 17.90 | 17.77 | 17.84 | |

| Avg deviation | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.51 | |

| CV (% Cq)b | 2.88 | 3.35 | 3.14 | |

E, reaction efficiency.

CV, coefficient of variance as a percentage of the Cq value.

RT-qPCR analysis of rpoE.

The relative expression levels of rpoE under different stress conditions were investigated by RT-qPCR in Y. pseudotuberculosis IP32953. Expression ratios of rpoE under different stresses are shown in Table 2. At 3°C in early logarithmic growth phase, the relative expression level of rpoE was 3.2-fold higher than that at 28°C in the same growth phase. In late logarithmic growth phase, there was no statistically significant difference between the relative expression levels at 3°C and 28°C. At 37°C the relative expression ratio of rpoE was 2.2 in both early and late logarithmic growth phases compared to its expression at 28°C at the respective growth phases. At 42°C the relative expression levels of rpoE during early and late logarithmic growth phases were 3.9- and 1.8-fold higher, respectively, than the relative expression levels at 28°C in the corresponding growth phases. Stress caused by pH 5.0 induced the highest relative expression level of rpoE, 13.0-fold higher than the relative expression level at 28°C in the early logarithmic growth phase. In addition, stresses caused by pH 9.0, 3% NaCl, and 3% ethanol significantly increased the relative expression levels of rpoE in the early logarithmic growth phase, the ratios being 3.9, 7.2, and 8.5, respectively. Exposure to pH 5.0, pH 9.0, 3% NaCl, and 3% ethanol did not affect the relative expression levels of rpoE in the late logarithmic growth phase (Table 2).

Growth experiments with the rpoE475 mutant and the complemented strain.

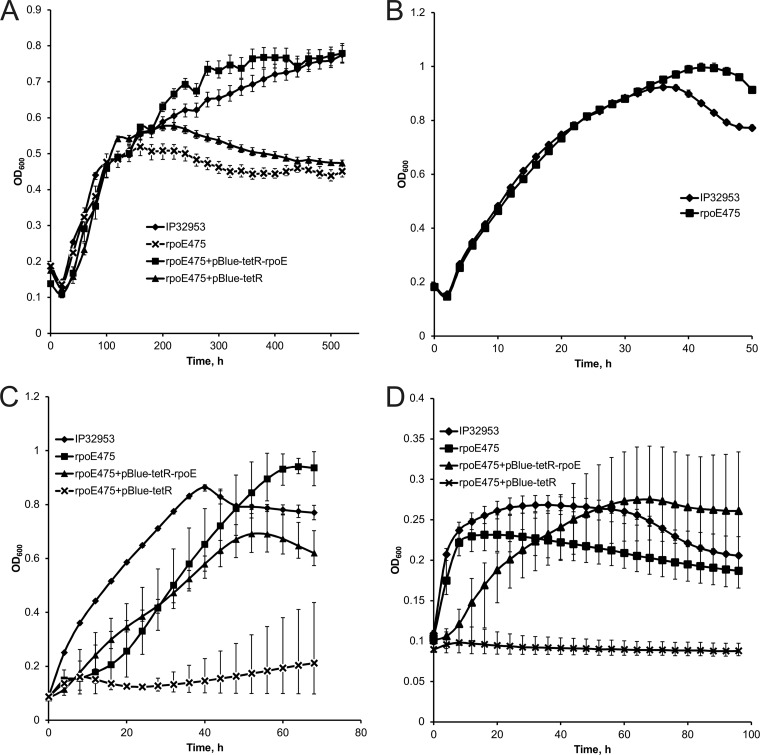

The growth of the rpoE475 mutant was investigated at 3°C, 28°C, 37°C, and 42°C and at 28°C at pH 5.0, pH 9.0, 3% NaCl, and 3% ethanol. At 3°C, the rpoE475 mutant showed growth similar to that of the wild type until the late logarithmic growth phase, after which the growth of the mutant ceased (Fig. 1A). Complementation of the rpoE mutation by the plasmid pBlue-tetR-rpoE, containing the coding sequences of rpoE, rseA, and rseB and 500 bp upstream of rpoE, restored the wild-type level of growth (Fig. 1A). Growth of the vector control did not differ from growth of the mutant (Fig. 1A). At the optimal growth temperature of 28°C, growth of the rpoE475 mutant did not differ from that of the wild type (Fig. 1B). At 37°C, the rpoE475 mutant had a longer lag phase than the wild type. The complemented mutant had a shortened lag phase but slower growth than the wild-type strain (Fig. 1C). Growth of the vector control was impaired (Fig. 1C). A relatively wide variation in the OD600 values of the mutant, complemented mutant, and vector control was observed at 37°C (Fig. 1C). At 42°C, the rpoE475 mutant did not reach as high an OD600 as the wild type (Fig. 1D). Growth of the complemented mutant was slower than that of the wild type, but OD600 levels similar to those for the wild type were attained, while the vector control did not grow at all (Fig. 1D). The rpoE475 mutant and the complemented mutant had relatively large variation in their OD600 values at 42°C (Fig. 1D).

Fig 1.

Growth curves of the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP32953 wild-type strain, rpoE475 mutant strain, complemented mutant, and vector control at 3°C (A), 28°C (B), 37°C (C), and 42°C (D). Measured OD600 values are shown at 20-h intervals (A), at 2-h intervals (B), and at 4-h intervals (C and D). Error bars indicate minimum and maximum values.

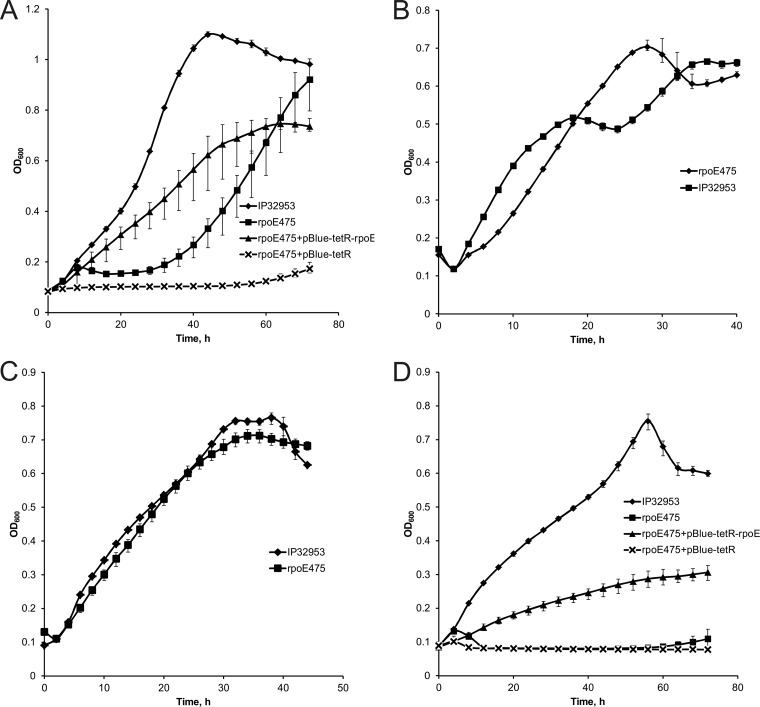

Under acid stress at pH 5.0, the rpoE475 mutant had a longer lag phase than the wild type (Fig. 2A). In the complemented mutant the lag phase was restored to the wild-type level, but the growth of the complemented mutant was slower than that of the wild type (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the vector control showed impaired growth (Fig. 2A). Growth of the rpoE475 mutant under alkali stress at pH 9.0 or under osmotic stress in 3% NaCl did not differ from growth of the wild type (Fig. 2B and C). In contrast, ethanol abolished the growth of the mutant (Fig. 2D). The growth of the complemented mutant was improved, while the vector control did not grow at all (Fig. 2D).

Fig 2.

Growth curves of the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP32953 wild-type strain, rpoE475 mutant strain, complemented mutant, and vector control at pH 5.0 (A), pH 9.0 (B), 3% NaCl (C), and 3% ethanol (D). Measured OD600 values are shown at 4-h intervals (A and D) and at 2-h intervals (B and C). Error bars indicate minimum and maximum values.

Minimum and maximum growth temperatures.

In the minimum-growth-temperature experiment, the wild-type strain IP32953 grew over the temperature gradient (0.8 to 9.5°C) within 10 days, indicating that the minimum growth temperature of IP32953 is lower than 0.8°C. The minimum growth temperature of the rpoE475 mutant in the time frame of 10 days was 1.2°C and thus statistically significantly higher than that of the wild-type strain (P < 0.05). The complemented rpoE475 mutant had a minimum growth temperature of 1.3°C. The minimum growth temperature of the vector control was 2.5°C. The maximum growth temperature of the rpoE475 mutant (36.1°C) within 2 days was significantly lower than that of the wild-type strain IP32953 (43.5°C, P < 0.05). The maximum growth temperature of the complemented mutant was 41.3°C and that of the vector control was 31.7°C. Thus, the rpoE475 mutation was successfully complemented, but the plasmids appeared to hinder growth slightly.

DISCUSSION

We studied the role of rpoE, the gene encoding the alternative σ factor σE, under temperature, pH, osmotic, and ethanol stresses in Y. pseudotuberculosis IP32953. We demonstrated that the expression of rpoE is induced by several stresses, and a mutation in rpoE impairs the tolerance of Y. pseudotuberculosis IP32953 to stresses caused by high or low temperature, low pH, and ethanol and narrows the growth temperature range.

We established by RT-qPCR that the transcription of rpoE is induced by low or high temperature, acidic or alkaline pH, increased osmolality, and 3% ethanol in Y. pseudotuberculosis IP32953. Most of these expression changes took place in the early logarithmic growth phase, which is not surprising, as many genes belonging to the σE regulon are involved in the synthesis of outer membrane components, which is particularly associated with active cell division (41). In E. coli, heat (15), increased expression of outer membrane proteins (14), unfolding or misfolding of outer membrane proteins (16), ethanol (17), and high osmolality (18) are known to induce σE-dependent envelope stress responses. However, in studies using DNA microarrays or reporter strains in E. coli and Yersinia enterocolitica, rpoE expression was not induced under the same stress response-inducing conditions, or the results were controversial (31, 42–44). Such differences in the rpoE expression results are probably explained by the different methods, strains, and test temperatures used. By using RT-qPCR, even small changes in gene expression can be detected (35), provided that the normalization reference gene is stable over the test conditions used. Stability of expression is demonstrated by a low coefficient of variance as a percentage of the Cq value (45). In our study, the expression of the reference gene 16S rrn was generally stable (Table 3) and in line with findings with Listeria monocytogenes, in which 16S rrn was documented to be the most stably expressed reference gene (46). Thus, we expect our gene expression results to be reliable. This is further supported by our finding that in Y. pseudotuberculosis, IP32953 rpoE expression is increased by the known inducers of σE-dependent envelope stress response of E. coli.

Apart from transcriptional control, rapid increase in σE activity under stress is contributed by the release of σE from its anti-sigma factor RseA (19). To gain further information on the role of σE, we used mutational analysis and studied growth under different conditions. Growth of the rpoE475 mutant was impaired at pH 5.0, at 3°C, at 37°C, and at 42°C, suggesting that functional rpoE is needed for optimal growth under acid, cold, and heat stress. Moreover, under ethanol stress the rpoE475 mutant did not grow at all. These findings support the RT-qPCR results suggesting an important role for rpoE in stress responses of Y. pseudotuberculosis. This role was further confirmed by successful complementation of the rpoE475 mutation with a plasmid containing the coding sequences of rpoE, rseA, and rseB and 500 bp upstream of the start codon of rpoE, and restoration of growth under the indicated stress conditions.

The growth temperature range of the rpoE475 mutant (1.2°C to 36.1°C) was narrower than the growth temperature range of the wild-type strain, IP32953 (<0.8°C to 43.5°C). The complemented rpoE475 mutant had a larger (1.3°C to 41.3°C) and the vector control had a narrower (2.5°C to 31.7°C) growth temperature range than the mutant alone. Large plasmids are known burdens for bacterial cells, retarding the lag phase and reducing the overall fitness of cells (47). In addition, a high copy number of a plasmid and the presence of tetracycline resistance gene in a plasmid can inhibit cell growth (48). Thus, the hampered growth of the rpoE475 mutant carrying the complementation plasmid at stressful conditions is not surprising.

The σE regulon of E. coli and related organisms contains genes involved in pathogenesis (41). In several Gram-negative pathogens, σE promotes survival in the host and is thus related to pathogenesis and needed for full virulence (49). At an early stage of Y. enterocolitica infection in mice, rpoE is expressed in Peyer's patches (43, 50). In Y. pseudotuberculosis, σE regulates the Ysc-Yop type III secretion system (51). The observed dramatic effect of the rpoE mutation on the maximum growth temperature, which was below the mammalian body temperature in the rpoE475 mutant, supports the proposed role of σE in virulence in Y. pseudotuberculosis (51).

In E. coli, rpoE is essential (52, 53), and its constitutive expression but not stress-related induction is indispensable for viability (54). As σE maintains cell envelope integrity (55), rpoE mutants are prone to have suppressor mutations to survive (52, 56). In E. coli, σE-mediated stress response is also needed for stress-induced mutagenesis, which increases genetic diversity and thus enables cell survival in harsh conditions (54). In Y. enterocolitica, rpoE is assumed to be indispensable because deletion mutants could not be created (43). An essential role for rpoE in Y. pseudotuberculosis YPIII has been suggested, since an rpoE deletion mutant was unstable (51). However, as previously stated, in E. coli (57) the successful complementation of the rpoE475 mutant demonstrates that the observed phenotypic characteristics of rpoE475 are indeed due to inactivated rpoE and less likely due to suppressor mutations.

Y. pseudotuberculosis can grow in wide temperature and pH ranges and thus survives well in the modern food chain. Our study demonstrates that functional σE is vital to tolerance of this pathogen to many stresses present during food production and storage.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was performed at the Finnish Centre of Excellence in Microbial Food Safety Research and was funded by the Academy of Finland (grants 118602 and 141140), the Doctoral Program of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of the University of Helsinki, the Finnish Veterinary Foundation, the Walter Ehrström Foundation, and the Medical Fund of the University of Helsinki.

We thank Esa Penttinen, Erika Pitkänen, Kirsi Ristkari, and Heimo Tasanen for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 July 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Rimhanen-Finne R, Niskanen T, Hallanvuo S, Makary P, Haukka K, Pajunen S, Siitonen A, Ristolainen R, Pöyry H, Ollgren J, Kuusi M. 2009. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis causing a large outbreak associated with carrots in Finland, 2006. Epidemiol. Infect. 137:342–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jalava K, Hakkinen M, Valkonen M, Nakari UM, Palo T, Hallanvuo S, Ollgren J, Siitonen A, Nuorti JP. 2006. An outbreak of gastrointestinal illness and erythema nodosum from grated carrots contaminated with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 194:1209–1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nuorti JP, Niskanen T, Hallanvuo S, Mikkola J, Kela E, Hatakka M, Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Lyytikainen O, Siitonen A, Korkeala H, Ruutu P. 2004. A widespread outbreak of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis O:3 infection from iceberg lettuce. J. Infect. Dis. 189:766–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukushima H, Gomyoda M, Shiozawa K, Kaneko S, Tsubokura M. 1988. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection contracted through water contaminated by a wild animal. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:584–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukushima H, Gomyoda M, Ishikura S, Nishio T, Moriki S, Endo J, Kaneko S, Tsubokura M. 1989. Cat-contaminated environmental substances lead to Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection in children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:2706–2709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Lindström M, Korkeala H. 2010. Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, p 164–180 In Juneja VK, Sofos JN. (ed), Pathogens and toxins in foods: challenges and interventions. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palonen E, Lindström M, Korkeala H. 2010. Adaptation of enteropathogenic Yersinia to low growth temperature. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 36:54–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palonen E, Lindström M, Karttunen R, Somervuo P, Korkeala H. 2011. Expression of signal transduction system encoding genes of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP32953 at 28°C and 3°C. PLoS One 6:e25063. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palonen E, Lindström M, Somervuo P, Johansson P, Björkroth J, Korkeala H. 2012. Requirement for RNA helicase CsdA for growth of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP32953 at low temperatures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:1298–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Österberg S, del Peso-Santos T, Shingler V. 2011. Regulation of alternative sigma factor use. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65:37–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raimann E, Schmid B, Stephan R, Tasara T. 2009. The alternative sigma factor σL of L. monocytogenes promotes growth under diverse environmental stresses. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 6:583–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mattila M, Somervuo P, Rattei T, Korkeala H, Stephan R, Tasara T. 2012. Phenotypic and transcriptomic analyses of sigma L-dependent characteristics in Listeria monocytogenes EGD-e. Food Microbiol. 32:152–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahlsten E, Kirk D, Lindström M, Korkeala H. 2013. Alternative sigma factor SigK has a role in stress tolerance of group I Clostridium botulinum strain ATCC 3502. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79:3867–3869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mecsas J, Rouviere PE, Erickson JW, Donohue T, Gross CA. 1993. The activity of σE, an Escherichia coli heat-inducible σ-factor, is modulated by expression of outer membrane proteins. Genes Dev. 7:2618–2628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erickson JW, Gross CA. 1989. Identification of the σE subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: a second alternate σ factor involved in high-temperature gene expression. Genes Dev. 3:1462–1471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh NP, Alba BM, Bose B, Gross CA, Sauer RT. 2003. OMP peptide signals initiate the envelope-stress response by activating DegS protease via relief of inhibition mediated by its PDZ domain. Cell 113:61–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raina S, Missiakas D, Georgopoulos C. 1995. The rpoE gene encoding the σE (σ24) heat shock sigma factor of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 14:1043–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bianchi AA, Baneyx F. 1999. Hyperosmotic shock induces the σ32 and σE stress regulons of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 34:1029–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ades SE. 2008. Regulation by destruction: design of the σE envelope stress response. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11:535–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alba BM, Gross CA. 2004. Regulation of the Escherichia coli σE-dependent envelope stress response. Mol. Microbiol. 52:613–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Missiakas D, Mayer MP, Lemaire M, Georgopoulos C, Raina S. 1997. Modulation of the Escherichia coli σE (RpoE) heat-shock transcription-factor activity by the RseA, RseB and RseC proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 24:355–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Las Peñas A, Connolly L, Gross CA. 1997. The σE-mediated response to extracytoplasmic stress in Escherichia coli is transduced by RseA and RseB, two negative regulators of σE. Mol. Microbiol. 24:373–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ades SE, Connolly LE, Alba BM, Gross CA. 1999. The Escherichia coli σE-dependent extracytoplasmic stress response is controlled by the regulated proteolysis of an anti-σ factor. Genes Dev. 13:2449–2461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alba BM, Leeds JA, Onufryk C, Lu CZ, Gross CA. 2002. DegS and YaeL participate sequentially in the cleavage of RseA to activate the σE-dependent extracytoplasmic stress response. Genes Dev. 16:2156–2168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanehara K, Ito K, Akiyama Y. 2002. YaeL (EcfE) activates the σE pathway of stress response through a site-2 cleavage of anti-σE, RseA. Genes Dev. 16:2147–2155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaba R, Alba BM, Guo MS, Sohn J, Ahuja N, Sauer RT, Gross CA. 2011. Signal integration by DegS and RseB governs the σE-mediated envelope stress response in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:2106–2111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kulp A, Kuehn MJ. 2011. Recognition of β-strand motifs by RseB is required for σE activity in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 193:6179–6186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akiyama Y, Kanehara K, Ito K. 2004. RseP (YaeL), an Escherichia coli RIP protease, cleaves transmembrane sequences. EMBO J. 23:4434–4442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaba R, Grigorova IL, Flynn JM, Baker TA, Gross CA. 2007. Design principles of the proteolytic cascade governing the σE-mediated envelope stress response in Escherichia coli: keys to graded, buffered, and rapid signal transduction. Genes Dev. 21:124–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flynn JM, Levchenko I, Sauer RT, Baker TA. 2004. Modulating substrate choice: the SspB adaptor delivers a regulator of the extracytoplasmic-stress response to the AAA protease ClpXP for degradation. Genes Dev. 18:2292–2301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moen B, Janbu AO, Langsrud S, Langsrud O, Hobman JL, Constantinidou C, Kohler A, Rudi K. 2009. Global responses of Escherichia coli to adverse conditions determined by microarrays and FT-IR spectroscopy. Can. J. Microbiol. 55:714–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulder B, Michiels T, Simonet M, Sory MP, Cornelis G. 1989. Identification of additional virulence determinants on the pYV plasmid of Yersinia enterocolitica W227. Infect. Immun. 57:2534–2541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chain PSG, Carniel E, Larimer FW, Lamerdin J, Stoutland PO, Regala WM, Georgescu AM, Vergez LM, Land ML, Motin VL. 2004. Insights into the evolution of Yersinia pestis through whole-genome comparison with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:13826–13831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. 2000. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol. 132:365–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pfaffl MW. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:2002–2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conchas RF, Carniel E. 1990. A highly efficient electroporation system for transformation of Yersinia. Gene 87:133–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakajima H, Inoue M, Mori T, Itoh K, Arakawa E, Watanabe H. 1992. Detection and identification of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica by an improved polymerase chain reaction method. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:2484–2486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaneko S, Ishizaki N, Kokubo Y. 1995. Detection of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis from pork using the polymerase chain reaction. Contrib. Microbiol. Immunol. 13:153–155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bolivar F, Rodriguez RL, Greene PJ, Betlach MC, Heyneker HL, Boyer HW, Crosa JH, Falkow S. 1977. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. II. A multipurpose cloning system. Gene 2:95–113 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hinderink K, Lindström M, Korkeala H. 2009. Group I Clostridium botulinum strains show significant variation in growth at low and high temperatures. J. Food Prot. 72:375–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rhodius VA, Suh WC, Nonaka G, West J, Gross CA. 2006. Conserved and variable functions of the σE stress response in related genomes. PLoS Biol. 4:e2. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.White-Ziegler CA, Um S, Perez NM, Berns AL, Malhowski AJ, Young S. 2008. Low temperature (23°C) increases expression of biofilm-, cold-shock- and RpoS-dependent genes in Escherichia coli K-12. Microbiology 154:148–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heusipp G, Schmidt MA, Miller VL. 2003. Identification of rpoE and nadB as host responsive elements of Yersinia enterocolitica. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 226:291–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maxson ME, Darwin AJ. 2004. Identification of inducers of the Yersinia enterocolitica phage shock protein system and comparison to the regulation of the RpoE and Cpx extracytoplasmic stress responses. J. Bacteriol. 186:4199–4208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Jonge HJ, Fehrmann RS, de Bont ES, Hofstra RM, Gerbens F, Kamps WA, de Vries EG, van der Zee AG, te Meerman GJ, ter Elst A. 2007. Evidence based selection of housekeeping genes. PLoS One 2:e898. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tasara T, Stephan R. 2007. Evaluation of housekeeping genes in Listeria monocytogenes as potential internal control references for normalizing mRNA expression levels in stress adaptation models using real-time PCR. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 269:265–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith MA, Bidochka MJ. 1998. Bacterial fitness and plasmid loss: the importance of culture conditions and plasmid size. Can. J. Microbiol. 44:351–355 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Valenzuela MS, Ikpeazu EV, Siddiqui K. 1996. E. coli growth inhibition by a high copy number derivative of plasmid pBR322. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 219:876–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raivio TL. 2005. Envelope stress responses and Gram-negative bacterial pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 56:1119–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young GM, Miller VL. 1997. Identification of novel chromosomal loci affecting Yersinia enterocolitica pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 25:319–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carlsson KE, Liu J, Edqvist PJ, Francis MS. 2007. Extracytoplasmic-stress-responsive pathways modulate type III secretion in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 75:3913–3924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Las Peñas A, Connolly L, Gross CA. 1997. σE is an essential sigma factor in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:6862–6864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:2006.0008. 10.1038/msb4100050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gibson JL, Lombardo MJ, Thornton PC, Hu KH, Galhardo RS, Beadle B, Habib A, Magner DB, Frost LS, Herman C, Hastings PJ, Rosenberg SM. 2010. The σE stress response is required for stress-induced mutation and amplification in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 77:415–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hayden JD, Ades SE. 2008. The extracytoplasmic stress factor, σE, is required to maintain cell envelope integrity in Escherichia coli. PLoS One 3:e1573. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Button JE, Silhavy TJ, Ruiz N. 2007. A suppressor of cell death caused by the loss of σE downregulates extracytoplasmic stress responses and outer membrane vesicle production in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 189:1523–1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Egler M, Grosse C, Grass G, Nies DH. 2005. Role of the extracytoplasmic function protein family sigma factor RpoE in metal resistance of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 187:2297–2307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]