Most general practitioners and physicians are familiar with the risk factors, clinical presentation, and management of retinopathy in patients with diabetes mellitus, commonly termed diabetic retinopathy. Fewer doctors are fully informed about other ocular and systemic causes of retinopathy or the clinical significance of retinopathy in patients without diabetes (referred to as non-diabetic retinopathy in this review). However, retinopathy is fairly common in adults without diabetes,1-4 and doctors routinely encounter such patients in whom clinical or laboratory evidence of hyperglycaemia is consistently absent.

Although some patients with retinopathy will have an obvious aetiology (for example, severe anaemia, systemic lupus erythematosis, or underlying carotid disease), many do not have an easily identifiable cause for their retinal signs. What course of action should the doctor take when faced with retinopathy in a patient without diabetes? What are the common ocular and systemic causes of retinopathy? What is the clinical significance of these retinopathy lesions? These and other matters are discussed in this review.

Sources and selection criteria

We reviewed studies on ocular and systemic causes of “retinopathy” from Medline and textbooks. We specifically excluded “diabetic retinopathy.”

Non-diabetic retinopathy

Non-diabetic retinopathy has been defined in different studies to include microaneurysms, retinal haemorrhages (dot, blot, and flame shaped), hard exudates, cotton wool spots, retinal venular abnormalities (venous beading and tortuosity), intraretinal microvascular abnormalities, and new vessels.1-3 The ocular and systemic causes of retinopathy in people without diabetes are varied (see table on bmj.com).

Ocular causes of non-diabetic retinopathy

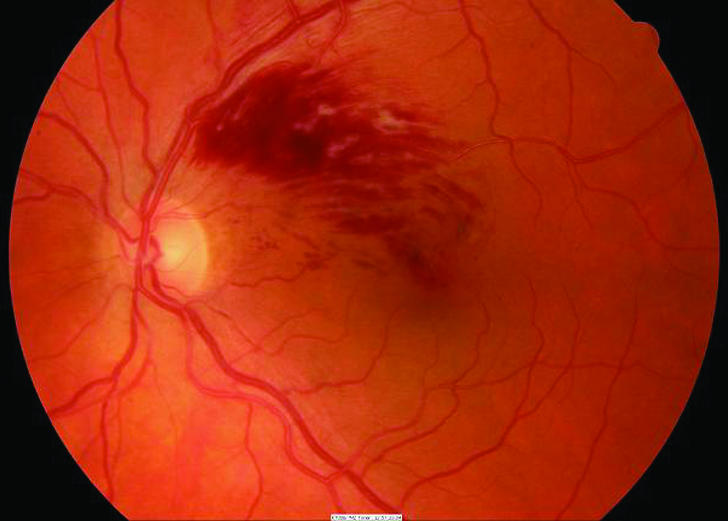

Retinal vein occlusion

Central retinal vein occlusion and branch retinal vein occlusion can present with non-diabetic retinopathy. The appearance on funduscopy is usually characteristic, with flame shaped haemorrhages present within the distribution of the affected vein (fig 1). The patient may complain of a sudden painless unilateral loss of vision or visual field (for example, inferior field defects for superior branch retinal vein occlusion) or may be asymptomatic. If loss of vision is severe a relative afferent pupillary defect may exist, indicating retinal ischaemia. Important systemic risk factors for retinal vein occlusion include hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and other conditions such as hyperhomocystinaemia.5 Glaucoma is an important ocular risk factor. The prevalence of retinal vein occlusion was noted in one study to be 1.6% in people above 49 years of age.6 Given the possible severe associations of this condition and its relatively high prevalence, retinal vein occlusion should not be overlooked.

Fig 1.

Branch retinal vein occlusion in a patient with hypertension

Summary points

Many people without diabetes may have signs of retinopathy (microaneurysms, retinal haemorrhages, cotton wool spots)

Ocular conditions associated with retinopathy in non-diabetic patients include retinal vein occlusions, retinal telangiectasia, and retinal macroaneurysms

Systemic conditions associated with retinopathy in non-diabetic patients include systemic hypertension, carotid atherosclerotic diseases, blood dyscrasias, systemic infections, and past radiotherapy to the head

Doctors should be aware of the common causes and clinical significance of these conditions, as retinopathy may be associated with visual loss (for example, retinal vein occlusion) or increased incidence of cardiovascular diseases (for example, hypertensive retinopathy)

Appropriate investigations and referral, if necessary, are advisable in the management of patients presenting with non-diabetic retinopathy

Retinal telangiectasia

Patients with retinal telangiectasia may present with retinopathy. In younger patients this is referred to as Coats' disease. It usually occurs in young men aged less than 20 years (median age 5 years7). Vision may be greatly affected in advanced cases. A milder form of the same disease, termed Leber's miliary aneurysms, can present later in life as a localised cluster of dilated capillaries, aneurysms, and telangiectasia, typically in the temporal quadrants of the retina. Either of these conditions should be suspected in young patients with retinopathy. About 8% of cases are asymptomatic.

Retinal macroaneurysm

Retinal macroaneurysm refers to an isolated aneurysmal dilatation of a major arterial or arteriolar branch that is often associated with leakage of exudate and multiple retinal haemorrhages. It usually occurs in older women and is strongly associated with hypertension and an increased incidence of cardiovascular and atherosclerotic vessel disease.8

Systemic causes of non-diabetic retinopathy

Hypertension

Hypertension is probably the best known systemic condition associated with non-diabetic retinopathy. In people with hypertension, retinopathy is often referred to as hypertensive retinopathy, although this definition has sometimes been expanded to include retinal arteriolar signs such as arteriovenous nicking and focal and generalised arteriolar narrowing.9 Retinopathy has been found to be present in about 11% of hypertensive non-diabetic people over 43 years of age.2

An appreciable proportion (average 6%) of normotensive non-diabetic people may also have retinopathy.1-3 In two population based studies, more than 50% of the participants with non-diabetic retinopathy did not have a history of hypertension.2,3 Retinopathy may thus represent the cumulative effects of elevated blood pressure throughout life in people not classified as having hypertension.

Atherosclerosis

The relation between atherosclerosis and retinopathy is not well studied. Carotid atherosclerotic vessel disease causing greater than 90% occlusion of the carotid artery system is known to cause ocular ischaemic syndrome, which may manifest as retinopathy.10 Several large epidemiological studies of non-diabetic retinopathy in relation to less severe atherosclerotic vessel disease have recently shown retinopathy to be linked to the presence of carotid artery plaques,4,11 increased intima-media thickness of the common and internal carotid arteries,4 and high concentrations of serum total cholesterol.11 One study found abdominal obesity, as measured by the waist:hip ratio, to be independently associated with the incidence of non-diabetic retinopathy developing after 10 years.1 Increased waist:hip ratio may be a manifestation of the metabolic syndrome encompassing conditions including atherosclerosis, diabetes, and hypertension.

Systemic vasculitis

Various systemic connective tissue diseases may also manifest in the eye as retinopathy. Cotton wool spots and intraretinal haemorrhages constitute the most common ocular manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosis.12 Although the clinical features may be similar to those of diabetic retinopathy, this retinopathy is usually associated with less ischaemia and visual loss. Other ocular features of systemic lupus erythematosis may provide clues, including scleritis, keratitis, and, rarely, corneal perforation.12 Retinopathy may improve after treatment of the systemic disease; however, exacerbations of retinopathy are common during relapses.13

Patients with the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome—typically women under the age of 50—commonly present with non-diabetic retinopathy independent of their systemic lupus erythematosis status.14 Screening for the antiphospholipid and anticardiolipin antibodies may thus be useful in such patients presenting with non-diabetic retinopathy, to direct appropriate subsequent management.

Behcet's disease characteristically presents with white patches of retinitis associated with cotton wool spots and retinal haemorrhages,15 as well as retinal vein occlusion and venous inflammation. Cotton wool spots may also be seen in other systemic vasculitides, such as polyarteritis nodosa, temporal arteritis, or Wegener's granulomatosis. Many of these conditions have multiple systemic manifestations that may aid in the diagnosis.

Blood dyscrasias

Severe anaemia of any cause is a known cause of retinopathy. Specific types of anaemia, such as sickle cell disease, may mimic diabetic retinopathy in its proliferative form.16 Pre-proliferative sickle cell retinopathy has a predilection for the peripheral retina and is usually asymptomatic in the early stages. Aplastic anaemia may manifest as non-diabetic retinopathy and may even present initially with preretinal haemorrhages in up to 13% of patients.17 Leukaemia can similarly present with cotton wool spots before diagnosis.18 Haematological and hypercoagulable states, such as deficiency of protein C or protein S, have also been reported to cause retinopathy and retinal vein occlusion (fig 2).5 Because some of these conditions are life threatening, a careful clinical examination and appropriate investigations may be necessary.

Fig 2.

Central retinal vein occlusion in a patient with protein C deficiency

Systemic infections

Patients with AIDS often develop retinal microangiopathy, typically resulting in isolated or multiple cotton wool spots and haemorrhages.19 This must be differentiated from signs of cytomegalovirus retinitis,19 which commonly occurs when the CD4 count falls below 200 cells/mm3. Toxoplasmosis may occasionally present with cotton wool spots and retinal vasculitis, usually adjacent to a classical punched-out white chorioretinal scar with associated pigment. Other clinical findings may include iritis, vitritis, swelling of the optic disc, and secondary retinal vein occlusion. Old, inactive “toxo” lesions in the other eye are common.

Patients with infective endocarditis may have Roth spots, which are pale-centred retinal haemorrhages caused by a localised thrombus. Other less common causes of non-diabetic retinopathy include infections such as tuberculosis and syphilis. Appropriate investigation of infectious causes is essential, as many conditions are treatable.

Radiation

Retinopathy due to radiation is known to occur up to 10 years after cranial or maxillary radiation and may not be readily distinguished from diabetic retinopathy on clinical examination.20 Hard exudates have been found to be more prevalent after brachytherapy, whereas intraretinal haemorrhages and microaneurysms are more commonly found after teletherapy.20 A careful history will often exclude this diagnosis.

Clinical significance of non-diabetic retinopathy

Whereas diabetic retinopathy is often associated with impairment of vision and blindness, the clinical significance of retinopathy in patients without diabetes is varied, particularly in cases of systemic disease.

Retinal vein occlusion and other retinal vascular disorders

Retinal vein occlusions and other retinal vascular disorders with signs of retinopathy are potentially sight threatening conditions. Ischaemic central retinal vein occlusion is associated with an increased risk of new vessel formation in the iris and subsequent secondary neovascular glaucoma, which can develop up to 24 months after initial presentation.5 Branch retinal vein occlusion can also lead to new vessel formation in the retina or optic disc, and both central retinal vein occlusion and branch retinal vein occlusion may lead to persistent macular oedema, causing permanent loss of vision. Prompt diagnosis and referral to an ophthalmologist for consideration of appropriate laser treatment are warranted. Retinal macroaneurysms may resolve spontaneously by thrombosis, or may be associated with recurrent leakage with retinal and vitreous haemorrhage. Laser photocoagulation may be indicated.8 Early treatment of Coats' disease can reduce the extent of visual loss.21

Severity of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and mortality

Retinopathy is a prognostic marker in patients with hypertension. In the Keith-Wagener-Barker classification, presence of retinal haemorrhages and cotton wool spots, when present with other retinal changes, is categorised as grade 3 retinopathy, signifying severe hypertensive disease.9 In epidemiological studies, retinopathy has consistently been reported to occur more often in people with uncontrolled or undetected and untreated hypertension than in normotensive people and those with adequately treated hypertension.2,3,22

Retinopathy has been linked with lower glomerular filtration rates and microalbuminuria, and it occurs in parallel with left ventricular hypertrophy early in the course of blood pressure elevation.8 More recent studies have also shown an independent association between the presence of retinopathy and cerebrovascular disease.22 Furthermore, retinopathy has been found to be independently associated with increased all cause mortality.23 The association between non-diabetic retinopathy and ischaemic heart disease, however, is not well established.4

Preclinical diabetes

An interesting question is whether retinopathy is a marker of future risk of diabetes. Few data are available on this subject. One study found that retinopathy was associated with increasing fasting blood sugar concentrations in people not classified as having diabetes mellitus,24 although another study did not find this association.3

Other systemic diseases

Retinopathy in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosis is a known marker for the active phase of the disease.12 Severe retinopathy and other ischaemic retinal changes have also been associated with central nervous system systemic lupus erythematosis.25 White patches of retinitis in Behcet's disease may be indicative of reactivation of the disease process.15

Non-diabetic retinopathy in an AIDS patient is associated with increased systemic severity of the disease.19 A specific correlation of the number of cotton wool spots with increasing systemic severity of AIDS and decreased cerebral blood flow is not well established.

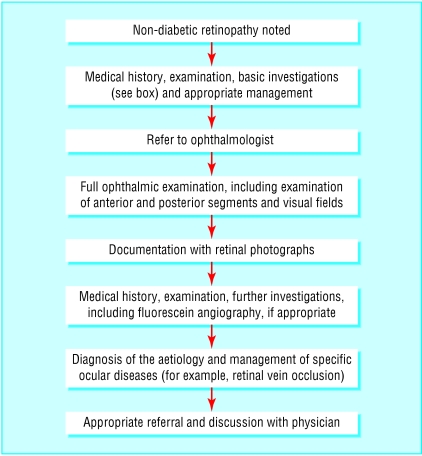

Clinical approach to management

Retinopathy has many severe implications and grave associations. It would thus be prudent for the doctor to investigate thoroughly and ascertain the aetiology in a patient presenting with non-diabetic retinopathy, to allow for the early institution of appropriate treatment. Figure 3 and the box present an algorithm, relevant aspects of which can be incorporated in the individual management of a patient with non-diabetic retinopathy. This approach should consist of a thorough history, medical examination, and appropriate laboratory investigations. Referral to an ophthalmologist for a full ophthalmic examination, including the use of fundus fluorescein angiography, should be considered.

Fig 3.

Initial management of non-diabetic retinopathy

Conclusion

Retinopathy lesions are commonly seen in middle aged and elderly people without diabetes. Common ocular conditions associated with retinopathy in non-diabetic patients include retinal vein occlusions, retinal telangiectasia, and retinal macroaneurysms. Common systemic causes include systemic hypertension, carotid atherosclerotic diseases, blood dyscrasias, systemic infections, and past radiotherapy. Doctors should be aware of these conditions and should appropriately investigate, refer, and manage these patients.

Additional education resources

Websites for doctors

www.emedicine.com—comprehensive, established, and regularly updated website containing extensively peer reviewed articles written by specialists on diseases spanning 62 medical specialties, including retinopathy

www.revoptom.com/HANDBOOK/default.htm—good site developed by optometrists outlining salient clinical and management principles of ocular disease, including many of the conditions predisposing to retinopathy

www.eyeweb.org—site developed and maintained by resident ophthalmologists at the American University of Beirut Medical Centre, providing short outlines of common ophthalmological conditions, including hypertensive retinopathy and retinal vein occlusion, tailored to primary care physicians

Websites for patients

www.emedicinehealth.com—recently developed branch website of the established web based medical reference emedicine.com, providing basic, well reviewed medical information on many conditions, including some diseases associated with retinopathy

www.intelihealth.com/IH/ihtIH/WSIHW000/408/408.html—website providing patients with basic information on various medical conditions, including some retinopathy related diseases, from sources such as Harvard Medical School

www.pennhealth.com/ency/content/index.html—website managed by the University of Pennsylvania Health System, containing information for patients on a multitude of medical conditions, including some retinopathy related diseases

www.eyemdlink.com/Conditions.asp—website dedicated to providing relevant information, contributed by American board certified ophthalmologists, to patients on ocular conditions, including retinopathy

Investigation of retinopathy

Medical history

Diabetes mellitus

Hypertension

History of cardiovascular disease (stroke, ischaemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease)

History of thrombosis

Anaemia (for example, sickle cell disease)

Drug history (for example, aplastic anaemia)

Connective tissue disease (for example systemic lupus erythematosis)

Radiotherapy (for example, central nervous system or nasopharyngeal tumours, thyroid eye disease)

Malignancy (for example, leukaemia)

AIDS

Physical examination

General health (pallor, cachexia, lymphadenopathy)

Blood pressure assessment

Cardiovascular assessment

Neurological assessment

Investigations

Full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate

Fasting glucose concentrations and oral glucose tolerance test

Lipids (total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides)

Infectious disease investigations (for example, chest x ray, syphilis and HIV serology)

Neurological investigations (for example, carotid ultrasound)

Connective tissue investigations (C reactive protein, antinuclear antibodies, anti-dsDNA)

Haematological investigations (activated protein C resistance, protein C activity, protein S activity, antithrombin III activity, antiphospholipid antibodies, and anticardiolipin antibodies)

Further special diagnostic investigations as indicated from preliminary results

Supplementary Material

A table appears on bmj.com

A table appears on bmj.com

We thank Tien Y Wong for his critical review of the paper.

Contributors: JV conducted the literature review and wrote the initial and final drafts. PM reviewed the manuscript and provided additional intellectual content and overall supervision.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Van Leiden HA, Dekker JM, Moll AC, Nijpels G, Heine RJ, Bouter LM, et al. Risk factors for incident retinopathy in a diabetic and nondiabetic population: the Hoorn study. Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121: 245-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE, Wang Q. Hypertension and retinopathy, arteriolar narrowing, and arteriovenous nicking in a population. Arch Ophthalmol 1994;112: 92-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu T, Mitchell P, Berry G, Li W, Wang JJ. Retinopathy in older persons without diabetes and its relationship to hypertension. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116: 83-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong TY, Klein R, Sharrett AR, Manolio TA, Hubbard LD, Marino EK, et al. The prevalence and risk factors of retinal microvascular abnormalities in older persons: the cardiovascular health study. Ophthalmology 2003;110: 658-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williamson TH. Central retinal vein occlusion: what's the story? Br J Ophthalmol 1997;81: 698-704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell P, Smith W, Chang A. Prevalence and associations of retinal vein occlusion in Australia: the Blue Mountains eye study. Arch Ophthalmol 1996;114: 1243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shields JA, Shields CL, Honavar SG, Demirci H. Clinical variations and complications of Coats disease in 150 cases: the 2000 Sanford Gifford memorial lecture. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;131: 561-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabb MF, Gagliano DA, Teske MP. Retinal arterial macroaneurysms. Surv Ophthalmol 1988;33: 73-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee S, Chattopadhya S, Hope-Ross M, Lip PL. Hypertension and the eye: changing perspectives. J Hum Hypertens 2002;16: 667-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown GC, Magargal LE. The ocular ischemic syndrome: clinical, fluorescein angiographic and carotid angiographic features. Int Ophthalmol 1988;11: 239-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein R, Sharrett AR, Klein BE, Chambless LE, Cooper LS, Hubbard LD, et al. Are retinal arteriolar abnormalities related to atherosclerosis? The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000;20: 1644-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jabs DA. Rheumatic diseases. In: Ryan SJ, Schachat AP, eds. Retina, 3rd ed, vol 2. St Louis, MO: Mosby, 2001: 1410-33. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klinkhoff AV, Beattie CW, Chalmers A. Retinopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus: relationship to disease activity. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29: 1152-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demirci FY, Kucukkaya R, Akarcay K, Kir N, Atamer T, Demirci H, et al. Ocular involvement in primary antiphospholipid syndrome: ocular involvement in primary APS. Int Ophthalmol 1998;22: 323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dominguez LN, Irvine AR. Fundus changes in Behcet's disease. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1997;95: 367-82, discussion 382-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charache S. Eye disease in sickling disorders. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 1996;10: 1357-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mansour AM, Salti HI, Han DP, Khoury A, Friedman SM, Salem Z, et al. Ocular findings in aplastic anaemia. Ophthalmologica 2000;214: 399-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schachat AP, Markowitz JA, Guyer DR, Burke PJ, Karp JE, Graham ML. Ophthalmic manifestations of leukaemia. Arch Ophthalmol 1989;107: 697-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jabs DA, Green WR, Fox R, Polk BF, Bartlett JG. Ocular manifestations of acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology 1989;96: 1092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown GC, Shields JA, Sanborn G, Augsburger JJ, Savino PJ, Schatz NJ. Radiation retinopathy. Ophthalmology 1982;89: 1494-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Budning AS, Heon E, Gallie BL. Visual prognosis of Coats' disease. J AAPOS 1998;2: 356-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong TY, Klein R, Klein BE, Tielsch JM, Hubbard L, Nieto FJ. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and their relationship with hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and mortality. Surv Ophthalmol 2001;46: 59-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schouten EG, Vandenbroucke JP, van der Heide-Wessel C, van der Heide RM. Retinopathy as an independent indicator of all-causes mortality. Int J Epidemiol 1986;15: 234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stolk RP, Vingerling JR, de Jong PT, Dielemans I, Hofman A, Lamberts SW, et al. Retinopathy, glucose, and insulin in an elderly population: the Rotterdam study. Diabetes 1995;44: 11-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jabs DA, Miller NR, Newman SA, Johnson MA, Stevens MB. Optic neuropathy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Ophthalmol 1986;104: 564-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.