Abstract

Colistin methanesulfonate (CMS), the inactive prodrug of colistin, is administered by inhalation for the management of respiratory infections. However, limited pharmacokinetic data are available for CMS and colistin following pulmonary delivery. This study investigates the pharmacokinetics of CMS and colistin following intravenous (i.v.) and intratracheal (i.t.) administration in rats and determines the targeting advantage after direct delivery into the lungs. In addition to plasma, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was collected to quantify drug concentrations in lung epithelial lining fluid (ELF). The resulting data were analyzed using a population modeling approach in S-ADAPT. A three-compartment model described the disposition of both compounds in plasma following i.v. administration. The estimated mean clearance from the central compartment was 0.122 liters/h for CMS and 0.0657 liters/h for colistin. Conversion of CMS to colistin from all three compartments was required to fit the plasma data. The fraction of the i.v. dose converted to colistin in the systemic circulation was 0.0255. Two BAL fluid compartments were required to reflect drug kinetics in the ELF after i.t. dosing. A slow conversion of CMS (mean conversion time [MCTCMS] = 3.48 h) in the lungs contributed to high and sustained concentrations of colistin in ELF. The fraction of the CMS dose converted to colistin in ELF (fm,ELF = 0.226) was higher than the corresponding fractional conversion in plasma after i.v. administration. In conclusion, pulmonary administration of CMS achieves high and sustained exposures of colistin in lungs for targeting respiratory infections.

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary administration of antibiotics for the treatment of respiratory infections has gained significant interest over the last decade, due to the potential for achieving high local drug concentrations at the site of infection (1–4). Other favorable attributes for targeting antibiotics to the respiratory tract include a rapid onset, while minimizing systemic exposure and adverse effects (1–4). Several antibiotics are in clinical development for the treatment of lung infections, with tobramycin, aztreonam, and colistin methanesulfonate (CMS) currently approved for inhalational administration in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients (5).

Colistin (also known as polymyxin E) was introduced into the market in the late 1950s for parenteral delivery but, due to the development of adverse effects, including nephro- and neurotoxicity, was replaced by other antibiotics (6–8). In the last 2 decades, however, there has been a resurgence in the use of colistin as last-line therapy against multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacteria, particularly Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter baumannii (6, 7, 9). Clinically, the inactive prodrug of colistin, CMS (10), is administered, with formation of colistin a prerequisite for antibacterial activity (11). CMS is administered via the pulmonary route in CF patients for the treatment of initial colonization of P. aeruginosa in the airways (12) and as maintenance therapy in chronic infections (13, 14). Effective treatment with inhaled CMS is crucial for delaying lung function deterioration (12–14). More recently, inhaled CMS has been introduced as adjunctive therapy in critically ill patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) caused by P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii (15, 16).

Despite the increase in inhalational administration of CMS, there are limited pharmacokinetic (PK) data available for CMS and formed colistin after pulmonary dosing. Recently, pharmacokinetic evaluation in rats (17), CF patients (18), and critically ill patients (19) has reported on CMS and/or formed colistin exposure in sputum or epithelial lining fluid (ELF) and plasma following inhalation of a single dose of CMS. Relative to plasma exposure, high CMS and/or formed colistin exposure in sputum/ELF was evident in all studies (17–19). However, none of these studies characterized the lung and systemic pharmacokinetics following administration of both CMS and colistin via the pulmonary and intravenous (i.v.) route. This information is required to accurately identify colistin absorption and disposition from the kinetics of formation following CMS conversion.

Therefore, the principal objective of the current study was to investigate the pharmacokinetics of CMS and colistin following i.v. and pulmonary administration of both compounds in rats. The development of a population pharmacokinetic model provided a better understanding of the CMS-to-colistin conversion kinetics and the disposition in plasma and ELF. Overall, the study identified the targeted advantage achieved following direct dosing of CMS into the lungs compared to i.v. administration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Colistin sulfate and sodium colistin methanesulfonate were from Sigma-Aldrich (Missouri, USA) and Link Pharmaceuticals Ltd. (Auckland, New Zealand), respectively. All other chemicals were of analytical reagent grade, and solvents were of at least high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade.

Animals.

All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes. The study protocols were reviewed and approved by the Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences Animal Ethics Committee. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (300 to 320 g) were acclimated for a minimum of 7 days in the faculty animal house within a temperature range of 18 to 24°C, 40 to 70% relative humidity, and 12-h light/dark cycles. Food and water were available ad libitum during the acclimation period and throughout the study. The day prior to the pharmacokinetic study, the right carotid artery of each rat was cannulated for collection of blood samples; the jugular vein was cannulated for i.v. dosing. Following surgery, rats were individually housed in metabolic cages and allowed 24 h for recovery.

Drug formulations and administration.

Immediately prior to i.v. and pulmonary administration, CMS (sodium) and colistin (sulfate) dosing solutions were freshly prepared in sterile 0.9% sodium chloride (Baxter Healthcare Pty Ltd., New South Wales, Australia). For the i.v. studies, CMS or colistin solutions were administered by a bolus injection via the jugular vein cannula. Intratracheal (i.t.) instillation was utilized as the technique for pulmonary administration, as it delivers an accurate and reproducible volume of dosing solution into a localized region of the lungs (20). For i.t. instillation, rats were lightly anesthetized with gaseous isoflurane (Delvert Pty Ltd., New South Wales, Australia) and rested in a supine position against a restraining board angled at approximately 60 to 70° from the horizontal. The tongue of the rat was gently pulled outwards using forceps, and the blade of a small animal laryngoscope (PennCentury Inc., Pennsylvania, USA) was positioned in the distal part of the mouth to enable visualization of the vocal cords. A 2.5-cm polyethylene tube (PE) (0.96 by 0.58 mm [outer diameter by inner diameter]) attached to a 23-gauge needle and 1-ml syringe was then maneuvered past the vocal cords to the trachea-bronchus bifurcation. A 100-μl aliquot of dosing solution followed by a 200-μl bolus of air was then delivered into the rat lungs. The air was administered to ensure complete delivery of the dosing solution from the syringe and cannula. Following i.t. instillation, rats were returned to metabolism cages where they rapidly recovered from the isoflurane anesthesia.

Pharmacokinetic studies.

Animals were administered i.v. CMS at doses of 14 mg/kg of body weight, 28 mg/kg or 56 mg/kg (n = 3 rats per dose). Blood samples (320 μl) were collected via the carotid artery prior to dosing and at 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 h postdosing. In an independent study, rats were administered i.v. colistin at doses of 0.21 mg/kg, 0.41 mg/kg, or 0.62 mg/kg (n = 3 rats per dose); blood samples (200 μl) were collected prior to dosing and at 0.02, 0.05, 0.08, 0.17, 0.33, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, and 4 h postdose. In the dose-ranging CMS study described above, blood samples were immediately placed on ice prior to centrifugation (6,700 × g, 4°C, 10 min), to minimize any potential in vitro conversion of CMS to colistin. Additionally, any potential in vitro conversion was minimized by storage of plasma samples at −80°C and subsequent HPLC analysis within 4 months of collection (21).

For the pulmonary dosing studies, two cohorts of animals were required to fully characterize systemic and lung exposure. Rats in the first cohort were administered i.t. CMS at doses of 14 mg/kg or 28 mg/kg (n = 3 rats per dose). Blood samples (320 μl) were collected predose and at 0.08, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 8 h postdose. In the second cohort, rats received a pulmonary dose of 14 mg/kg CMS, to allow for the collection of terminal bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and a corresponding blood sample. Samples were collected at 0.08, 0.5, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 h postdose (n = 3 rats per time point). In a separate study, rats in the first cohort were administered colistin at i.t. doses of 0.41 mg/kg, 0.62 mg/kg, 0.99 mg/kg, or 1.49 mg/kg (n = 3 rats per dose). Blood samples were collected as described above following i.v. colistin dosing. A second cohort of rats received an i.t. dose of 0.62 mg/kg colistin; terminal BAL fluid and blood samples were collected as described for i.t. dosing of CMS. Blood samples were processed as described above, and the plasma was collected to quantify drug and urea concentrations (for the second cohort of rats). Bronchoalveolar lavage and processing of BAL fluid samples were undertaken as detailed below.

The lowest dosages in these studies were selected based on the quantification limits of the analytical methods in both plasma and in BAL fluid, whereas the higher dosages for i.v. CMS were defined on the basis of known tolerability in rats (22). Intratracheal administration of 56 mg/kg CMS was not well tolerated, and therefore only two CMS i.t. dosages were evaluated. Colistin dosages were selected to achieve plasma concentrations known to be well tolerated by the animals.

Bronchoalveolar lavage.

Rats were anesthetized with gaseous isoflurane and sacrificed via exsanguination. For BAL fluid, the trachea was exposed and a small incision was made to allow the insertion of a PE tube (1.70 by 1.20 mm [outer diameter by inner diameter]) attached to an 18-gauge needle. The lungs were gently lavaged with 5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4, 4°C) for three cycles, using fresh PBS each time. The recovered lavage fluid was pooled and centrifuged (6,700 × g, 4°C, 10 min), and the resulting supernatant was removed and stored at −80°C prior to HPLC analysis.

Plasma and bronchoalveolar fluid analysis.

The concentrations of colistin and CMS in plasma and BAL fluid were determined using previously validated HPLC assays (23, 24) with minor modifications. Briefly, the analytical methods involved quantification of colistin before and after forced in vitro conversion from CMS; the concentration of CMS was calculated as the difference between the two assay results and adjusted for molecular weight (23, 24). For each colistin and CMS assays, calibration standards and quality control (QC) samples were from independently prepared stock solutions. For the plasma assay, colistin and CMS calibration standards were prepared in drug-free rat plasma and ranged from 0.08 to 3.3 mg/liter and 0.70 to 47 mg/liter, respectively. For the analysis in BAL fluid, calibration standards were prepared in drug-free rat BAL fluid-acetonitrile (50:50, vol/vol) and ranged from 0.20 to 6.60 mg/liter (colistin) and 0.70 to 47 mg/liter (CMS). Rat plasma and BAL fluid samples with colistin and CMS concentrations above the upper end of the respective plasma and BAL fluid calibration curve were diluted to within the linear range with drug-free matrix; QC samples of colistin and CMS were treated similarly to confirm satisfactory assay performance. The limit of quantification (LOQ) was defined as the lowest concentration in the calibration curve, at which the accuracy and precision were within ±20%; at all other concentrations, the accuracy and precision were within ±15%.

Urea concentrations in plasma and BAL fluid were determined using a commercially available kit, QuantiChrom urea assay kit (BioAssay Systems, California, USA). Urea is an endogenous marker of dilution and was used to estimate the apparent volume of the ELF (VELF) (25). The apparent VELF was calculated as follows: VELF = ([Urea]BAL fluid/[Urea]Plasma) × VBALF, where [Urea]BAL fluid, [Urea]Plasma, and VBALF are the urea concentration in BAL fluid (mg/dl) and plasma (mg/dl) and the volume of recovered BAL fluid, respectively. The VELF was used to calculate the concentration of CMS or colistin in ELF ([CMS/Colistin]ELF) as follows: [CMS/Colistin]ELF = [CMS/Colistin]BALF × (VBALF/VELF), where [CMS/Colistin]BALF is the concentration of CMS or colistin in the recovered BAL fluid.

Pharmacokinetic modeling.

Initially, a noncompartmental analysis (NCA) of dose-normalized concentration-versus-time profiles was conducted using WinNonlin (version 5.3; Pharsight Corporation, USA) to guide model development. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of the observed (non-dose-normalized) concentrations was then performed using nonlinear mixed-effects modeling in S-ADAPT (version 1.57) facilitated by S-ADAPT-TRAN (26). Initially, models were independently developed for CMS and colistin following i.v. administration. One-, two-, three-, and four-compartment models were tested to obtain key disposition parameters of CMS or colistin in plasma. The concentration-versus-time data of CMS and colistin in plasma, BAL fluid, and ELF were then combined to simultaneously analyze the pharmacokinetic profiles after i.v. and i.t. administration. Two compartments (BAL fluid1 and BAL fluid2) were required to reflect drug kinetics in the BAL fluid. The total amount of drug in the BAL fluid was therefore represented by the sum of the predicted amounts in BAL fluid1 and BAL fluid2. These total drug amounts were divided by VELF, for the prediction of CMS or colistin concentrations in the ELF. This approach was used because direct estimation of ELF drug concentrations gave rise to model instability, probably due to the very low values derived for VELF.

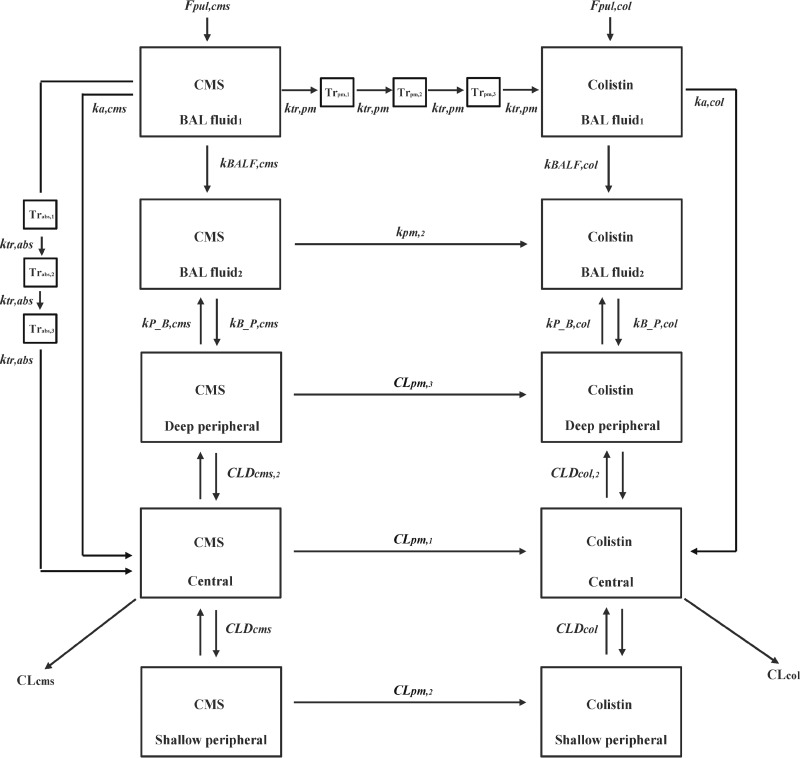

First-order and mixed-order kinetics were tested to describe the conversion of CMS to colistin and the absorption of both compounds from the lungs into the systemic circulation. These models also explored whether a delay (represented by a series of transit [Tr] compartments) in conversion or absorption was required to adequately fit the data. Figure 1 illustrates the structure of the final composite model. The corresponding differential equations for the structural model are provided in Appendix (equations A1 to A16).

Fig 1.

Structure of the population pharmacokinetic model for CMS and colistin following intravenous and intratracheal dosing in rats. Abbreviations are defined in Table 1.

The between-subject variability (BSV) in parameter estimates was assumed to follow a log-normal distribution, with the magnitude reported as a coefficient of variation (CV). Residual unexplained variability (RUV) in the plasma model was evaluated using a combined exponential and additive random error. For the BAL fluid and ELF model, the exponential and additive components were fixed to assay precision (15%) and LOQ (0.18 μmol/liter for colistin and 0.45 μmol/liter for CMS), respectively. This allowed for the estimation of BSV, since only a single observation was obtained from each rat due to terminal BAL sampling. Data below the LOQ were handled using a likelihood-based (M3) method (27).

Visual inspection of diagnostic scatter plots, the objective function value (OBJ; reported as −1 × log likelihood in S-ADAPT), and the biological plausibility of the parameter estimates were used for model selection. Statistical comparison of the models was performed using a χ2 test; a decrease in the OBJ of 1.92 units (α = 0.05) was considered significant.

The final model was evaluated by performing a visual predictive check (VPC). For this, 1,000 data sets were simulated from the final parameter estimates using the original data. The median and the 10th and 90th percentiles (25th and 75th percentiles for the ELF models) of the simulated predictions were computed and plotted against the observed values. All reported parameter estimates and VPCs were from the simultaneous modeling of CMS and colistin pharmacokinetics after i.v. and i.t. dosing. For clinical relevance, all concentrations are reported in units of mg/liter (although the model was developed in units of μmol/liter to facilitate accurate estimation of CMS-to-colistin conversion kinetics).

Histopathology.

Histopathology examination was undertaken to determine whether cellular damage to the lung epithelium occurred following pulmonary dosing of CMS or colistin. Two control groups (n = 3 rats per group) were dosed with 100 μl of blank saline via i.t. instillation; the treatment groups (n = 3 rats per group) received either 14 mg/kg CMS or 0.62 mg/kg colistin (doses corresponding to the studies where BAL fluid was collected) in a 100-μl aliquot. Following dosing, rats were anesthetized and sacrificed via exsanguination at 4 h (for CMS) or 0.75 h (for colistin); sample collection times reflect maximal concentrations in plasma. The trachea was exposed and an incision made to allow for the insertion of an 18-gauge needle. The trachea/lungs were then immediately fixed with 5 ml of formalin solution (neutral buffered, 10%; Sigma-Aldrich) and stored in 10 ml of formalin solution. Histopathology examination (Cerberus Sciences, South Australia, Australia) was performed on the following lung tissues: (i) trachea in the lumen, mucosa, submucosa, submucosal glands, connective tissue, and cartilage regions, and (ii) lung lobes in the external/internal bronchi, terminal bronchioles/alveolar ducts, tracheal bifurcation (lumen, mucosa, submucosa, connective tissues), pleura, blood vessels, and the bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue regions. BAL was not performed prior to tissue harvesting to ensure that the histopathology was not affected by excess fluid in the alveoli.

RESULTS

Pharmacokinetics following intravenous administration.

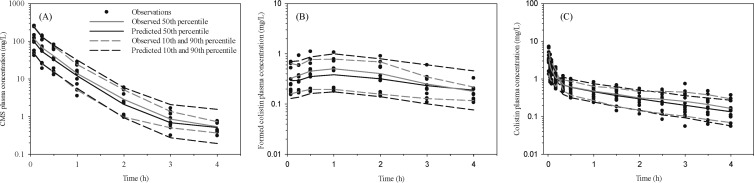

Following administration of i.v. CMS, average maximal plasma concentrations of CMS were 44 mg/liter (lowest dose) and 201 mg/liter (highest dose) and declined by approximately three orders of magnitude over the study period (Fig. 2A). The corresponding concentrations of formed colistin in plasma were quantifiable at the first sampling time (5 min), with mean peak concentrations of 0.20 mg/liter (lowest dose) and 0.81 mg/liter (highest dose) (Fig. 2B). These maximal concentrations were achieved between 0.5 to 1 h after CMS administration and declined relatively slowly during the sampling period (Fig. 2B). Administration of the active antibacterial moiety, colistin, was undertaken to characterize the disposition in plasma, with average maximal plasma concentrations ranging from 1.2 to 4.7 mg/liter, and concentrations declining exponentially over the 4-h sampling period (Fig. 2C).

Fig 2.

Visual predictive check for CMS (A) and formed colistin plasma concentration (B) following intravenous (i.v.) CMS dosing and colistin plasma concentration (C) following i.v. colistin dosing in Sprague-Dawley rats. The model-predicted median and 10th and 90th percentiles closely match corresponding observed percentiles, indicating the suitability of the pharmacokinetic model. Closed circles represent actual observed data in rats.

Pharmacokinetics following intratracheal instillation.

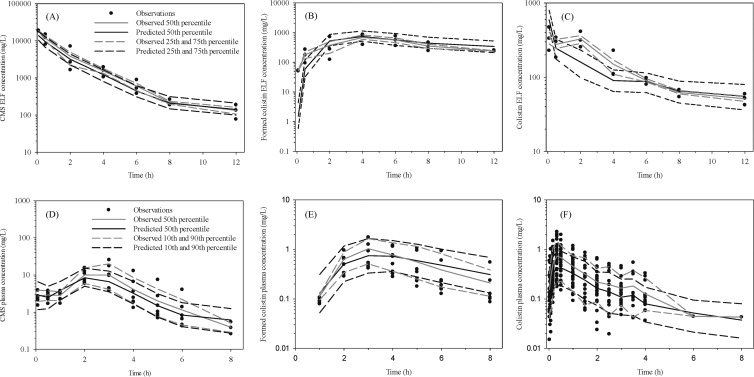

Pulmonary administration of CMS resulted in average ELF concentrations of 21,391 mg/liter at 5 min postdose, and thereafter concentrations declined over the 12-h sampling period (Fig. 3A). Maximal concentrations of formed colistin in ELF were achieved at 4 h after CMS dosing, with relatively high concentrations maintained throughout the 12-h sampling period (Fig. 3B). Measured concentrations of urea after i.t. CMS were 56 ± 13 mg/dl in plasma and 0.35 ± 0.13 mg/dl in BAL fluid, with an estimated apparent VELF of 0.084 ± 0.016 ml. Similar urea concentrations (50 ± 9.2 mg/dl and 0.41 ± 0.14 mg/dl in plasma and BAL fluid, respectively) and apparent VELF estimates (0.11 ± 0.023 ml) were obtained after i.t. administration of colistin.

Fig 3.

Visual predictive check for CMS (A), formed colistin in ELF following intratracheal (i.t.) CMS dosing (B), and colistin in ELF following i.t. colistin dosing (C); CMS (D), formed colistin in plasma after i.t. CMS dosing (E), and colistin in plasma following i.t. colistin dosing (F) in Sprague-Dawley rats. The model-predicted median and 25th/75th and 10th/90th percentiles broadly match corresponding observed percentiles, suggesting reasonably good predictive performance. Closed circles represent actual observed data in rats. The 25th and 75th percentiles are presented for the ELF profiles, due to the small number of observations obtained via this sampling route.

Population pharmacokinetic model.

In the full composite model, the disposition of both CMS and colistin in plasma was best described by a three-compartment model. Table 1 presents the parameter estimates from the final model. The estimated mean clearance from the central compartment was 0.122 liters/h (BSV, 10.7%) for CMS and 0.0657 liters/h (BSV, 24.7%) for colistin. Steady-state volumes of distribution were 0.292 liters and 0.170 liters for CMS and colistin, respectively. Conversion of CMS to colistin in the central compartment was described by a first-order process (CLpm = 0.0016 liters/h; corresponding rate constant of 0.102 h−1). Similar conversion clearances were incorporated from the shallow and deep peripheral compartments to fit the high concentrations of formed colistin at 2 h after i.v. administration of CMS. In the absence of these peripheral conversion terms, the model was statistically inferior (ΔOBJ, +20.1). The rate constant for central conversion was more than 3-fold faster than that estimated in shallow (0.0303 h−1) and deep (0.00121 h−1) peripheral compartments. The estimated fraction of the i.v. CMS dose converted to colistin (fm,systemic) was 0.0255. Figure 2 presents the VPCs for both compounds after their i.v. administration.

Table 1.

Population pharmacokinetic parameter estimates for CMS and colistin after intravenous and pulmonary dosing

| Sample type and antibiotic or residual error | Parameter | Description | Unit | Estimated value | BSV (CV%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | |||||

| Colistin | VCcol | Central vol of distribution | Liter | 0.0464 | 20.9 |

| CLcol | First-order central compartment clearance | Liter/h | 0.0657 | 24.7 | |

| VPcol,1 | Shallow peripheral vol of distribution | Liter | 0.0294 | 128 | |

| CLDcol | Shallow peripheral intercompartmental clearance | Liter/h | 0.366 | 23.5 | |

| VPcol,2 | Deep peripheral vol of distribution | Liter | 0.0942 | 23.6 | |

| CLDcol,2 | Deep peripheral intercompartmental clearance | Liter/h | 0.0402 | 32.0 | |

| CMS | VCcms | Central vol of distribution | Liter | 0.0157 | 17.9 |

| CLcms | First-order central compartment clearance | Liter/h | 0.122 | 10.7 | |

| VPcms,1 | Shallow peripheral vol of distribution | Liter | 0.0432 | 6.65 | |

| CLDcms | Shallow peripheral intercompartmental clearance | Liter/h | 0.356 | 16.1 | |

| VPcms,2 | Deep peripheral vol of distribution | Liter | 0.233 | 31.8 | |

| CLDcms,2 | Deep peripheral intercompartmental clearance | Liter/h | 0.0178 | 35.2 | |

| CLpm,1a | Central compartment clearance of CMS to colistin | Liter/h | 0.00160 | 16.4 | |

| CLpm,2a | Shallow peripheral clearance of CMS to colistin | Liter/h | 0.00131 | 20.4 | |

| CLpm,3a | Deep peripheral clearance of CMS to colistin | Liter/h | 0.000282 | 71.8 | |

| Lung | |||||

| Colistin | Fpul,col | Fractional dose available for pulmonary disposition | 0.485 | 69.6 | |

| ka,col | First-order rate constant for lung absorption | 1/h | 2.15 | 20.6 | |

| kBALF,col | First-order transfer from BAL fluid1 to BAL fluid2 | 1/h | 0.397 | 29.1 | |

| kB_P,col | Distribution from BAL fluid2 to deep peripheral | 1/h | 0.0843 | 24.9 | |

| kP_B,col | Distribution from deep peripheral to BAL fluid2 | 1/h | 0.00416 | 69.5 | |

| CMS | Fpul,cms | Fractional dose available for pulmonary disposition | 0.409 | 54.5 | |

| ka,cms | First-order rate constant for lung absorption | 1/h | 0.936 | 45.1 | |

| Durabs,cms | Duration for zero-order absorption | h | 2.21 | 13.3 | |

| MTTcms,abs | Mean transit time for pulmonary absorption | h | 1.50 | 10.4 | |

| kBALF,cms | First-order transfer from BAL fluid1 to BAL fluid2 | 1/h | 3.17 | 27.8 | |

| kB_P,cms | Distribution from BAL fluid2 to deep peripheral | 1/h | 0.608 | 9.45 | |

| kP_B,cms | Distribution from deep peripheral to BAL fluid2 | 1/h | 0.0121 | 35.6 | |

| MCTcms,conv | Mean conversion time for CMS in BAL fluid1 | h | 3.48 | 16.5 | |

| kpm,2 | Rate constant for CMS conversion in BAL fluid2 | 1/h | 0.0154 | 162 | |

| Residual errorb | SDslcol,plasma | Exponential error for colistin in plasma | % | 18.1 | |

| SDslCMS,plasma | Exponential error for CMS in plasma | % | 16.7 |

Plasma kpm,1, kpm,2, and kpm,3 were 0.102, 0.0303, and 0.00121 h−1, respectively.

Residual error for the BAL fluid and ELF model was fixed to the assay precision and limit of quantification, since only a single observation was obtained from each rat due to terminal BAL sampling.

Following i.t. instillation, the fractional dose (Fpul) available for exposure to the lungs was 40.9% for CMS and 48.5% for colistin. Two compartments (BAL fluid1 and BAL fluid2) described drug movement from the i.t. dosing site to the remaining regions of the respiratory airways (see Fig. 1). For CMS, the estimated mean time (1/kBALF) for movement from BAL fluid1 to BAL fluid2 was 0.315 h, which was faster than that for colistin (2.52 h). Additional first-order terms were included to describe the distribution of both compounds from the lung lining fluid to the deep peripheral compartment in the plasma model.

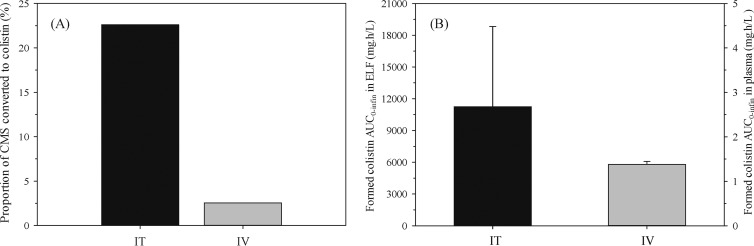

The model required a low rate of CMS conversion (mean conversion time [MCTCMS] = 3.48 h in BAL fluid1) to describe the high concentrations of colistin maintained in the ELF (Fig. 3B; Fig. 3 provides the VPCs for both compounds in ELF and in plasma after i.t. dosing). This slow conversion adequately explained the subsequent delay in absorption of colistin into plasma (Fig. 3E). In contrast, only a single first-order term (kpm = 0.0154 h−1) was required to describe the kinetics of CMS to colistin conversion in BAL fluid2. The estimated fraction of the CMS dose converted to colistin in ELF (fm,ELF) was 0.226 and was almost 9-fold higher than the corresponding fractional conversion in plasma (0.0255) after i.v. administration (Fig. 4A).

Fig 4.

Percentage of i.t. (14 mg/kg) and i.v. (dose-ranging) CMS doses converted to colistin in ELF (black) and plasma (gray) (A) and formed colistin exposure (AUC0–∞, μmol · h/liter) in ELF and plasma following i.t. and i.v. administration of 14 mg/kg CMS, respectively (B). Formed colistin exposure was approximately 8,000-fold higher in ELF after i.t. dosing than in plasma after i.v. dosing. For panel B, note the different scale for the right y axis.

First-order kinetics best described the absorption of both CMS (kacms = 0.936 h−1) and colistin (kacol = 2.15 h−1) from the i.t. dosing compartment (BAL fluid1) to plasma. For CMS, an additional pathway incorporating zero-order with sequential delayed first-order absorption was required to fit the high concentrations observed at 2 to 3 h in plasma (Fig. 3D). This route was a minor component of the model and contributed only to 0.3% of total CMS absorption.

Exposure of formed colistin following intratracheal instillation.

Following i.t. instillation of CMS (14 mg/kg), the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) of formed colistin in ELF was 11,245 ± 7,568 mg · h/liter. Of this, only 0.03% of formed colistin from ELF was absorbed into plasma (AUC = 3.01 ± 0.476 mg · h/liter). After i.v. dosing of CMS, the AUC of formed colistin in plasma was 1.38 ± 0.0746 mg · h/liter. Thus, i.t. dosing gave a formed colistin exposure in ELF that was 8,000-fold higher than that in plasma after i.v. dosing (Fig. 4B).

Histopathology examination.

Histopathology examination of the trachea and lung lobes following i.t. administration of either CMS or colistin showed no significant difference between the control and treatment groups (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The current study evaluates the pharmacokinetics of CMS and colistin following i.v. and i.t. administration of both compounds in rats. The data showed that direct administration of CMS into the lungs achieved high ELF exposure to formed colistin, thus demonstrating the potential for local targeting of antibiotics for the treatment of respiratory infection. Population pharmacokinetic analysis was advantageous in this study, because it allowed for the simultaneous modeling of plasma sampled via serial bleeds in one cohort of animals and ELF data from a second cohort where terminal BAL samples were obtained. The pharmacokinetic model provided a better understanding of the conversion kinetics for CMS to colistin in ELF and in plasma. The population pharmacokinetic analysis identified that high colistin concentrations in ELF were obtained due to slow and sustained conversion kinetics of CMS in ELF after i.t. administration.

Intravenous dose-ranging studies demonstrated linear pharmacokinetics for CMS and colistin, consistent with the findings by Marchand et al. in Sprague-Dawley rats (28). The pharmacokinetic parameter estimates were broadly consistent with previously reported values arising from NCA after i.v. administration of CMS (17, 28, 29) and colistin (30) in rats.

There is limited knowledge on the mechanism by which colistin is formed from CMS in vitro and in vivo (21, 31, 32). Conversion of CMS generates a complex mixture of partially sulfomethylated derivatives and colistin, formation of the latter being a prerequisite for antibacterial activity (10, 32). While previous studies in rats have reported on the fraction of an i.v. CMS dose that is converted to colistin systemically (17, 29), the kinetics of this conversion are currently unknown. Li et al. (29) and Marchand et al. (17) estimated a fractional systemic conversion of ∼6% and ∼13%, respectively, which is higher than that estimated in the present study (3%). The population pharmacokinetic model required conversion in all three disposition compartments (central, shallow, and deep peripheral), to characterize the gradual appearance of formed colistin in plasma following i.v. administration of CMS. Maximal plasma concentrations of formed colistin were achieved at 0.5 to 1 h post-CMS administration, which was in contrast to results of studies by Li et al. (29) and Marchand et al. (17, 28), where peak concentrations of formed colistin were observed at the initial sampling time of 5 min. The interstudy variation in the conversion kinetics is potentially the result of the use of different brands of sodium CMS, which can have various ratios of fully and partially sulfomethylated CMS derivatives and yield different plasma concentration-versus-time courses for formed colistin (33). Importantly, in all of the above-described preclinical evaluations, a low proportion (∼3 to 13%) of the i.v. dose of CMS was converted to colistin.

This study demonstrates that direct pulmonary administration of CMS achieves high ELF exposure to formed colistin compared to the exposure in plasma. The concentrations of colistin in ELF were maintained, over the 12-h sampling period, above the MIC required for 50 to 90% inhibition of bacterial growth based on clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp. (MIC50–90) of 1.0 mg/liter (34). The high concentrations of CMS and formed colistin in ELF described here are consistent with the findings by Marchand et al., following i.t. nebulization to rats at a dose equivalent to 14 mg/kg CMS (17).

Population pharmacokinetic analysis identified slower conversion kinetics in the lung following i.t. instillation, with a greater fraction of the CMS dose (23%) converted to colistin in ELF than in plasma after i.v. administration (3%) (Fig. 4A). This slow and sustained conversion (in BAL fluid1) contributed to the high colistin concentrations in ELF and the corresponding delay in its plasma appearance after i.t. administration of CMS. With limited information available about the conversion mechanism of CMS to colistin, one potential explanation for the slower but ultimately more extensive conversion observed in the lungs is that while CMS resides within the lung, it is not available for renal clearance, which is the major systemic clearance mechanism (11). A further contributing factor to the increased ELF exposure is that CMS will be dissolved within a relatively small volume of lung lining fluid (ELF volume estimated to be 0.084 ± 0.016 ml) and thereby creating a reservoir of CMS available for ongoing conversion to colistin, which will be reflected in the high exposure of formed colistin in ELF and a greater fractional conversion of CMS in the lungs. Marchand et al. proposed similar explanations for observations of high CMS concentrations in ELF (slow conversion and absorption), with the authors reporting a slightly higher fraction of the i.t. CMS dose converted to colistin (39%) in the lungs than in plasma (17).

Two BAL fluid compartments were included in the model to reflect the site of i.t. dosing and the movement of drug over time to other regions of the lungs. Thus, BAL fluid1 potentially represents localized antibiotic concentrations in the trachea, upper airways, and to some extent the peripheral airways, followed by monodirectional transfer into the remaining peripheral lung regions (represented as BAL fluid2). Relative to CMS, a slower movement of colistin into the peripheral airways may have occurred due to colistin binding to lung tissues (35–37). Several sites have been proposed for the binding of lipophilic basic amines (pKa > 8.5) in the lungs (38–41). Further antibiotic distribution from the ELF to the deep peripheral compartment suggests that this compartment could equate to the lung tissue, although additional studies are required to confirm this hypothesis.

In the current model, the absorption of CMS and colistin from the lungs into the systemic circulation was best described by first-order kinetics, with an additional minor (<1%) delayed pathway for the former compound. Appearance of colistin in plasma following i.t. administration of colistin was more rapid (plasma concentrations quantifiable at 1 to 10 min postdose, Fig. 3F) than for formed colistin (1 h postdose) after i.t. dosing of CMS (Fig. 3E). For formed colistin, this is likely to be due to the ongoing conversion from CMS in the lungs. Given the physicochemical properties of CMS (average Mw of 1,633 Da, polar surface area [PSA] of 741 Å, log P of −12.09) and colistin (average Mw of 1,163 Da, PSA of 490 Å, log P of 3.42), the proposed mechanism of absorption is passive diffusion via paracellular transport mechanisms. This is supported by Schanker and colleagues, who reported that the rat lung epithelium is characteristic of the classic lipoid pore of biological membrane (42–44). Tronde et al. have also illustrated passive diffusion as the dominant transport mechanism for drug absorption from the rat lungs (45, 46). In the present study, the slow absorption of CMS from the lungs was consistent with the low apparent permeability for CMS through Calu-3 cells (apical-to-basolateral direction) (17).

Notwithstanding the extensive lung exposure to formed colistin, its relative systemic exposure following i.t. administration of CMS (14 mg/kg) was 2-fold higher than the systemic exposure after i.v. administration of the same dose of CMS. The greater fraction of CMS dose converted to colistin in the ELF (23%) and absorption of a proportion of this presystemically formed colistin are the most likely causes for these findings. These results are, in part, consistent with findings by Marchand et al., who reported that 39% of the i.t. CMS dose was converted to colistin in the lungs prior to absorption into the systemic circulation, which the authors speculated led to the increased exposure to formed colistin in plasma (17). The potential for lung epithelium damage and resultant increased drug permeability was considered an alternative explanation for the increased plasma exposure to formed colistin in this study; however, histopathological analysis of lung tissue following i.t. administration confirmed that this was not the case. This study in rats suggests that a reduction in the pulmonary CMS dose could achieve colistin concentrations in ELF above the MIC50-90 of 1.0 mg/liter (34) and still reduce total systemic exposure and hence reduce the likelihood of adverse effects.

Population pharmacokinetic analysis demonstrated good predictive performance of a model that simultaneously fits six dependent variables. While minor model misspecification is apparent in some profiles (e.g., colistin in ELF following i.t. administration of colistin; Fig. 3C), these would not alter the pharmacological implications of the exposure achieved after direct (targeted) administration to the lungs. Future applications of the current model could test whether similar CMS-to-colistin conversion occurs with the use of different inhalational formulations (e.g., dry powder) in the preclinical setting. Furthermore, the model serves as a basis for the translation of CMS and colistin pharmacokinetics from rodents to larger animal models and humans. While the current structural model is developed in noninfected animals, it can be adapted to the estimation of known PK differences in infected murine models (47–49). Ultimately, these models could be usefully employed to develop inhalational dosing recommendations for CMS in CF patients that simultaneously consider target endpoints in respiratory infection while avoiding potential adverse effects.

In conclusion, we have for the first time developed a detailed model that describes the pharmacokinetics of CMS and colistin after both i.v. and i.t. administration. We demonstrate that high concentrations of colistin in rat ELF are achieved as a result of slow and sustained CMS conversion following i.t. instillation. Slow absorption of CMS into the systemic circulation and less competing clearance pathways for CMS in the lungs contribute to the greater fractional conversion in the lungs. The higher colistin systemic exposure after i.t. administration than exposure after i.v. dosing of CMS is a result of absorption of formed colistin from the lungs. This has the potential to increases systemic toxicity but may be modulated by a dose reduction, since colistin exposures in the current study were well above the MICs of P. aeruginosa. The current population pharmacokinetic model can be utilized to further investigate the conversion kinetics of CMS and to characterize the disposition of CMS and formed colistin following inhalational administration in larger animals and in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Carl Kirkpatrick, Jürgen Bulitta, and Cornelia Landersdorfer for advice and assistance with development of the population pharmacokinetic model.

There are no transparency declarations to make.

S.W.S.Y. was supported by a Monash Postgraduate Research Scholarship.

APPENDIX

Equations describing the structural PK model for CMS and colistin.

Changes in the amount of CMS in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (ABALF,cms) were calculated using equations A1 and A2:

| (A1) |

| (A2) |

where the absorption of CMS from BALF1 was partitioned into a fraction (Fka) via first-order kinetics, with the remaining fraction (1 − Fka) via a minor zero-order component. Adperi,cms is the amount of CMS in the plasma deep peripheral compartment, and all other parameters are defined in Table 1.

The slow conversion kinetics of CMS to colistin through 3 transit (Tr) compartments in BALF1 are described by equations A3 to A5:

| (A3) |

| (A4) |

| (A5) |

The minor zero-order absorption of CMS followed by first-order transit through 3 compartments is described by equations A6 to A8:

| (A6) |

| (A7) |

| (A8) |

Changes in the amount of colistin in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (ABALF,col) were calculated by equations A9 and A10:

| (A9) |

| (A10) |

The CMS model in plasma is described by equations A11 to A13:

| (A11) |

| (A12) |

| (A13) |

The colistin model in plasma is described by equations A14 to A16:

| (A14) |

| (A15) |

| (A16) |

where cent, speri, and dperi represent the central, shallow peripheral, and deep peripheral compartments in plasma, respectively, and C is the concentration of CMS or colistin.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 5 August 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Geller DE. 2009. Aerosol antibiotics in cystic fibrosis. Respir. Care 54:658–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antoniu SA, Cojocaru I. 2012. Inhaled colistin for lower respiratory tract infections. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 9:333–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Labiris N, Dolovich M. 2003. Pulmonary drug delivery. Part I: physiological factors affecting therapeutic effectiveness of aerosolized medications. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 56:588–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer LB. 2011. Aerosolized antibiotics in the intensive care unit. Clin. Chest Med. 32:559–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hewer SL. 2012. Inhaled antibiotics in cystic fibrosis: what's new? J. R. Soc. Med. 105(Suppl 2):S19–S24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J, Nation R, Milne R, Turnidge J, Coulthard K. 2005. Evaluation of colistin as an agent against multi-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 25:11–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falagas ME, Kasiakou SK. 2005. Colistin: the revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:1333–1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landman D, Georgescu C, Martin DA, Quale J. 2008. Polymyxins revisited. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21:449–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nation RL, Li J. 2009. Colistin in the 21st century. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 22:535–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergen PJ, Li J, Rayner CR, Nation RL. 2006. Colistin methanesulfonate is an inactive prodrug of colistin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1953–1958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Milne RW, Coulthard K, Rayner CR, Paterson DL. 2006. Colistin: the re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6:589–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen CR, Pressler T, Hoiby N. 2008. Early aggressive eradication therapy for intermittent Pseudomonas aeruginosa airway colonization in cystic fibrosis patients: 15 years experience. J. Cyst. Fibros. 7:523–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doring G, Conway SP, Heijerman HG, Hodson ME, Hoiby N, Smyth A, Touw DJ. 2000. Antibiotic therapy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: a European consensus. Eur. Respir. J. 16:749–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doring G, Hoiby N. 2004. Early intervention and prevention of lung disease in cystic fibrosis: a European consensus. J. Cyst. Fibros. 3:67–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michalopoulos A, Fotakis D, Virtzili S, Vletsas C, Raftopoulou S, Mastora Z, Falagas ME. 2008. Aerosolized colistin as adjunctive treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia due to multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: a prospective study. Respir. Med. 102:407–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korbila IP, Michalopoulos A, Rafailidis PI, Nikita D, Samonis G, Falagas ME. 2010. Inhaled colistin as adjunctive therapy to intravenous colistin for the treatment of microbiologically documented ventilator-associated pneumonia: a comparative cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:1230–1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchand S, Gobin P, Brillault J, Baptista S, Adier C, Olivier JC, Mimoz O, Couet W. 2010. Aerosol therapy with colistin methanesulfonate: a biopharmaceutical issue illustrated in rats. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3702–3707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ratjen F, Rietschel E, Kasel D, Schwiertz R, Starke K, Beier H, van Koningsbruggen S, Grasemann H. 2006. Pharmacokinetics of inhaled colistin in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:306–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Athanassa ZE, Markantonis SL, Fousteri MZ, Myrianthefs PM, Boutzouka EG, Tsakris A, Baltopoulos GJ. 2012. Pharmacokinetics of inhaled colistimethate sodium (CMS) in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 38:1779–1786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brain JD, Knudson DE, Sorokin SP, Davis MA. 1976. Pulmonary distribution of particles given by intratracheal instillation or by aerosol inhalation. Environ. Res. 11:13–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dudhani RV, Nation RL, Li J. 2010. Evaluating the stability of colistin and colistin methanesulphonate in human plasma under different conditions of storage. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1412–1415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallace SJ, Li J, Nation RL, Rayner CR, Taylor D, Middleton D, Milne RW, Coulthard K, Turnidge JD. 2008. Subacute toxicity of colistin methanesulfonate in rats: comparison of various intravenous dosage regimens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1159–1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Milne R, Nation R, Turnidge J, Coulthard K, Johnson D. 2001. A simple method for the assay of colistin in human plasma, using pre-column derivatization with 9-fluorenylmethyl chloroformate in solid-phase extraction cartridges and reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 761:167–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li J, Milne RW, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Coulthard K, Valentine J. 2002. Simple method for assaying colistin methanesulfonate in plasma and urine using high-performance liquid chromatography. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3304–3307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rennard SI, Basset G, Lecossier D, O'Donnell KM, Pinkston P, Martin PG, Crystal RG. 1986. Estimation of volume of epithelial lining fluid recovered by lavage using urea as a marker of dilution. J. Appl. Physiol. 60:532–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bauer R. 2008. S-ADAPT/MCPEM user's guide (version 1.57). Software for pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and population data analysis. Biomedical Simulations Resource, Berkeley, CA [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beal SL. 2001. Ways to fit a PK model with some data below the quantification limit. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 28:481–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marchand S, Lamarche I, Gobin P, Couet W. 2010. Dose-ranging pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulphonate (CMS) and colistin in rats following single intravenous CMS doses. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1753–1758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, Milne R, Nation R, Turnidge J, Smeaton T, Coulthard K. 2004. Pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulphonate and colistin in rats following an intravenous dose of colistin methanesulphonate. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:837–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J, Milne RW, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Smeaton TC, Coulthard K. 2003. Use of high-performance liquid chromatography to study the pharmacokinetics of colistin sulfate in rats following intravenous administration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1766–1770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallace SJ, Li J, Rayner CR, Coulthard K, Nation RL. 2008. Stability of colistin methanesulfonate in pharmaceutical products and solutions for administration to patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3047–3051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li J, Milne RW, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Coulthard K. 2003. Stability of colistin and colistin methanesulfonate in aqueous media and plasma as determined by high-performance liquid chromatography. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1364–1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He H, Li J, Nation R, Jacob J, Chen G, Lee H, Tsuji B, Thompson P, Roberts K, Velkov T, Li J. 7 June 2013. Pharmacokinetics of four different brands of colistimethate and formed colistin in rats. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. [Epub ahead of print.] 10.1093/jac/dkt207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gales AC, Jones RN, Sader HS. 2011. Contemporary activity of colistin and polymyxin B against a worldwide collection of Gram-negative pathogens: results from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2006-09). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:2070–2074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ziv G, Nouws JF, van Ginneken CA. 1982. The pharmacokinetics and tissue levels of polymyxin B, colistin and gentamicin in calves. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Therapeut. 5:45–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kunin CM, Bugg A. 1971. Binding of polymyxin antibiotics to tissues: the major determinant of distribution and persistence in the body. J. Infect. Dis. 124:394–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Craig WA, Kunin CM. 1973. Dynamics of binding and release of the polymyxin antibiotics by tissues. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 184:757–765 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson MW, Orton TC, Pickett RD, Eling TE. 1974. Accumulation of amines in the isolated perfused rabbit lung. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 189:456–466 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vestal RE, Kornhauser DM, Shand DG. 1980. Active uptake of propranolol by isolated rabbit alveolar macrophages and its inhibition by other basic amines. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 214:106–111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson AG, Sar M, Stumpf WE. 1982. Autoradiographic study of imipramine localization in the isolated perfused rabbit long. Drug Metab. Dispos. 10:281–283 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshida H, Okumura K, Kamiya A, Hori R. 1989. Accumulation mechanism of basic drugs in the isolated perfused rat lung. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 37:450–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schanker LS. 1978. Drug absorption from the lung. Biochem. Pharmacol. 27:381–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Enna SJ, Schanker LS. 1972. Absorption of drugs from the rat lung. Am. J. Physiol. 223:1227–1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burton JA, Schanker LS. 1974. Absorption of antibiotics from the rat lung. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 145:752–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tronde A, Norden B, Marchner H, Wendel AK, Lennernas H, Bengtsson UH. 2003. Pulmonary absorption rate and bioavailability of drugs in vivo in rats: structure-absorption relationships and physicochemical profiling of inhaled drugs. J. Pharm. Sci. 92:1216–1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tronde A, Norden B, Jeppsson AB, Brunmark P, Nilsson E, Lennernas H, Bengtsson UH. 2003. Drug absorption from the isolated perfused rat lung—correlations with drug physicochemical properties and epithelial permeability. J. Drug Target. 11:61–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crandon JL, Kim A, Nicolau DP. 2009. Comparison of tigecycline penetration into the epithelial lining fluid of infected and uninfected murine lungs. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:837–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keel RA, Crandon JL, Nicolau DP. 2012. Pharmacokinetics and pulmonary disposition of tedizolid and linezolid in a murine pneumonia model under variable conditions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:3420–3422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valcke Y, Pauwels R, Van der Straeten M. 1990. The penetration of aminoglycosides into the alveolar lining fluid of rats. The effect of airway inflammation. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 142:1099–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]