Abstract

Despite antibiotic therapy, acute and long-term complications are still frequent in pneumococcal meningitis. One important trigger of these complications is oxidative stress, and adjunctive antioxidant treatment with N-acetyl-l-cysteine was suggested to be protective in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. However, studies of effects on neurological long-term sequelae are limited. Here, we investigated the impact of adjunctive N-acetyl-l-cysteine on long-term neurological deficits in a mouse model of meningitis. C57BL/6 mice were intracisternally infected with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Eighteen hours after infection, mice were treated with a combination of ceftriaxone and placebo or ceftriaxone and N-acetyl-l-cysteine, respectively. Two weeks after infection, neurologic deficits were assessed using a clinical score, an open field test (explorative activity), a t-maze test (memory function), and auditory brain stem responses (hearing loss). Furthermore, cochlear histomorphological correlates of hearing loss were assessed. Adjunctive N-acetyl-l-cysteine reduced hearing loss after pneumococcal meningitis, but the effect was minor. There was no significant benefit of adjunctive N-acetyl-l-cysteine treatment in regard to other long-term complications of pneumococcal meningitis. Cochlear morphological correlates of meningitis-associated hearing loss were not reduced by adjunctive N-acetyl-l-cysteine. In conclusion, adjunctive therapy with N-acetyl-l-cysteine at a dosage of 300 mg/kg of body weight intraperitoneally for 4 days reduced hearing loss but not other neurologic deficits after pneumococcal meningitis in mice. These results make a clinical therapeutic benefit of N-acetyl-l-cysteine in the treatment of patients with pneumococcal meningitis questionable.

INTRODUCTION

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common etiological agent of bacterial meningitis in adults in the United States and Europe (1). Despite advanced antibiotic therapy and supportive intensive care, it still has a high case fatality rate of about 20% (2, 3). This unfavorable clinical outcome is often caused by intracranial and systemic complications, such as brain edema, hydrocephalus, cerebrovascular complications, and intracranial hemorrhage. Up to 50% of survivors suffer from long-term deficits, such as hearing loss (2, 4, 5). One reason for the development of acute and long-term intracranial and cochlear complications is collateral tissue damage from the host's own immune response, which is meant to fight the invasive pathogen. Activated immune cells and neutrophils that invade the subarachnoid space produce massive amounts of reactive oxygen (ROS) and nitrogen species (RNS), including superoxide anion (O2−) and nitric oxide (NO) (6). The simultaneous production of O2− and NO leads to the formation of peroxynitrite (ONOO−). ROS, RNS, and especially ONOO− can exert a variety of toxic actions, including lipid peroxidation (which leads to endothelial cell dysfunction), DNA strand breakage [followed by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) activation and subsequent cellular energy depletion associated with cell death], and activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (leading to the degradation of extracellular matrix and the production of inflammatory cytokines) (7–11).

The first evidence for the clinical relevance of ROS and RNS in meningitis came from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies: footprints of O2−, NO, and ONOO− were found in the CSF of patients with pneumococcal meningitis, and the CSF levels of nitrotyrosine (NT-3; a reaction product of ONOO− and tyrosine) correlated with the clinical outcomes (6, 12). This led to the investigation of several O2− and ONOO− scavengers and inhibitors of the isoforms of nitric oxide synthases (NOS) in models of pneumococcal meningitis, with conflicting results depending on the inhibitor and the animal model used (13–19). So far, quite promising results have been obtained using N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC). NAC protects against oxidative stress by direct antioxidative properties and indirectly by increasing intracellular glutathione levels (20). NAC, which has already been in clinical use for a long time without remarkable side effects (e.g., for therapy of acetaminophen intoxication) (20–22), was shown to reduce brain edema, intracranial pressure (ICP), and CSF pleocytosis in adult rats (16) and to attenuate cortical neuronal necrosis in infant rats during the acute stage of pneumococcal meningitis (23, 24). Furthermore, an attenuation of acute and long-term hearing loss and its morphological correlates was found in rats with pneumococcal meningitis (25). Just recently, NAC was reported to reduce neurocognitive deficits in adult rats who survived experimental pneumococcal meningitis (26). Thus, NAC was considered a promising therapeutic agent for adjunctive therapy of pneumococcal meningitis. However, long-term animal studies focusing on effects of adjunctive therapy with NAC on clinical symptoms throughout the course of the disease and after recovery are limited, and moreover, the currently published data were obtained in adult and infant rats with pneumococcal meningitis only (16, 23–25). Before experimental data can be considered eligible for a clinical trial, a beneficial therapeutic effect of a drug needs to be proven powerful enough to show up under different conditions. This is especially important since differences in species are a known factor that can influence the outcome of a study (27, 28). Therefore, here, we investigated NAC in an adult mouse model of pneumococcal meningitis to see whether an effect of NAC could also be translated from rat models into another species, which would be one important prerequisite for taking it under consideration for a clinical trial in humans with pneumococcal meningitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse model of pneumococcal meningitis.

A well-characterized mouse model (male, C57BL/6) of pneumococcal meningitis was used (29–32). Briefly, after clinical testing (see below), meningitis was induced by transcutaneous intracisternal injection of 15 μl of a bacterial suspension containing 106 CFU/ml of S. pneumoniae D39 or placebo under short-term anesthesia with isoflurane. Mice were weighed, put into cages, allowed to wake up, and fed with a standard diet and water ad libidum. Eighteen hours after infection, when all mice showed clinical signs of meningitis, animals were treated intraperitoneally with ceftriaxone (100 mg/kg of body weight daily) for a total of 4 days. Furthermore, animals received adjunctive NAC or placebo (see experimental groups). Two weeks after infection, mice were assessed for neurological deficits and hearing loss. Then, animals were sacrificed with an intraperitoneal overdose of thiopental (300 mg/kg of body weight) and perfused transcardially with 15 ml of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) containing 10 U/ml heparin (Braun, Melsungen, Germany). The temporal bones and brains were dissected, decalcified in PBS containing 10% EDTA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), fixed in 4% formalin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and embedded in paraffin. All animal experiments were approved by the government of Upper Bavaria, Germany.

Experimental groups.

The following groups were investigated: (i) mice intracisternally injected with 15 μl PBS (uninfected controls; n = 8), (ii) mice intracisternally injected with S. pneumoniae and treated with 100 mg/kg ceftriaxone (Roche, Grenzach-Wyhlen, Germany) every day for 4 days and 0.5 ml isotonic saline every 8 h for a total of 4 days (ceftriaxone and placebo; n = 15), and (iii) mice intracisternally injected with S. pneumoniae and treated with 100 mg/kg ceftriaxone every day for 4 days and 100 mg/kg NAC every 8 h for a total of 4 days (ceftriaxone and NAC, n = 11). The chosen dosage of NAC equals the dosage that is given during acute acetaminophen intoxication (33). Treatment was begun 18 h after infection. All groups were followed for 14 days. To investigate the effect of an adjunctive treatment, animals who received adjunctive therapy with NAC (ceftriaxone and NAC) were compared with placebo-treated mice (ceftriaxone).

Clinical assessment of mice. (i) Clinical score.

Animals were investigated clinically before infection and 18 h, 24 h, 42 h, 66 h, and 2 weeks after infection, and clinical scores (CS) were determined as previously described (34–36), ranging from 0 points if there were no clinically noticeable signs of disease to 12 points if the animal died. In brief, the following criteria were assessed: (i) beam balancing, (ii) postural reflexes, (iii) piloerection, (iv) epileptic seizures, and (v) level of consciousness.

(ii) Explorative activity.

For determination of explorative activity, each mouse was put in the middle of a 42- by 42-cm box divided into 9 squares and allowed to explore the box for 2 min. The number of squares which the mouse passed through within the 2-min time interval was counted.

(iii) T-maze.

For determination of memory function, mice were investigated by t-maze (37). A T-shaped open box was used (one long arm measuring 30- by 15-cm and two short arms measuring 20- by 15-cm each). One short arm (arm B) was initially closed, and the other short arm was initially open (arm A). Mice were placed in the long arm of the T and were allowed to explore freely for 5 min. After a break of 30 min (animals were allowed to rest in the cage), mice were placed again in the long arm of the T, with both short arms now being open. Again, the mouse was allowed to explore, now for 2 min. The percentage of time the mouse spent exploring in the previously closed arm B was measured and set into correlation with the total time that the mouse spent exploring arm A and arm B. This was described by the formula “time in arm B/(time in arm A + time in arm B).” Healthy mice usually remember the previously explored arm A and, therefore, spend more time in the previously closed and yet-to-be explored arm B. If a mouse spends similar times in both short arms during the second exploration round, this is indicative for a loss of short-term memory.

Determination of hearing.

Hearing was determined by auditory brain stem responses (ABRs) at the end of the experiment. Mice were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg ketamine and 5 mg/kg xylazine injected intraperitoneally. Needle electrodes were placed over each mastoid (negative pole), the vertex (positive pole), and the neck (reference). Impedances were controlled to be below 5 kΩ. Square-wave click impulses (duration, 100 ms; frequency, 20 Hz) and tone bursts of 1 and 10 kHz (duration, 4 ms; frequency, 23.4 Hz) were delivered by earphones (E-A-RTONE3A; Aearo Company, Indianapolis, IN). ABRs were amplified (×250,000), band-pass filtered (150 to 10,000 Hz), and averaged (n = 1,000) using a Neuroscreen Plus (Jaeger-Toennies, Freiburg, Germany). To determine the hearing threshold, we started with an impulse of 105-dB sound pressure level (SPL) and reduced the intensity in 5-dB SPL steps. The lowest stimulus intensity that elicited ABRs was considered to be the hearing threshold. If a response could not be elicited at 105-dB SPL, stimulus intensities of up to 130-dB SPL were tested.

Histologic assessment of cochleae.

For histological analysis, midmodiolar sections (thickness, 7 μm) of mouse temporal bones were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and stained with Mayer's hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Sections were digitized using an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus Optical, Hamburg, Germany) connected to a camera (Moticam 5000; Motic Deutschland GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). Three representative sections of each cochlea were analyzed, and the means were calculated for the following parameters. For determination of the density of spiral ganglion neuronal cells in the cochlea, the area of each spiral ganglion was measured (Image Tool version 3.00; University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX), and morphologically intact spiral ganglion neurons (criteria were an intact cell body containing a round nucleus with nucleolus and homogenous cytoplasm) were counted within this area. The degree of occlusion of the perilymphatic spaces (the beginning of labyrinthitis ossificans) was evaluated by measurement of the occluded area of the basal turn of the tympanic scala (Image Tool version 3.00; University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio). The occluded area was calculated as the percentage of the total area of the basal scala tympani.

Statistical analysis.

All experimental procedures were performed in a blinded fashion. Data were analyzed with SYSTAT 9 (SPSS, Chicago, IL), using a t test for independent variables. Mortality was compared using the Chi2 test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. The box plots in Fig. 1, 2, and 4 display the median (line), the mean (dashed line), and the 25th (bottom of box), 75th (top of box), 5th (lower whisker), and 95th (upper whisker) percentiles.

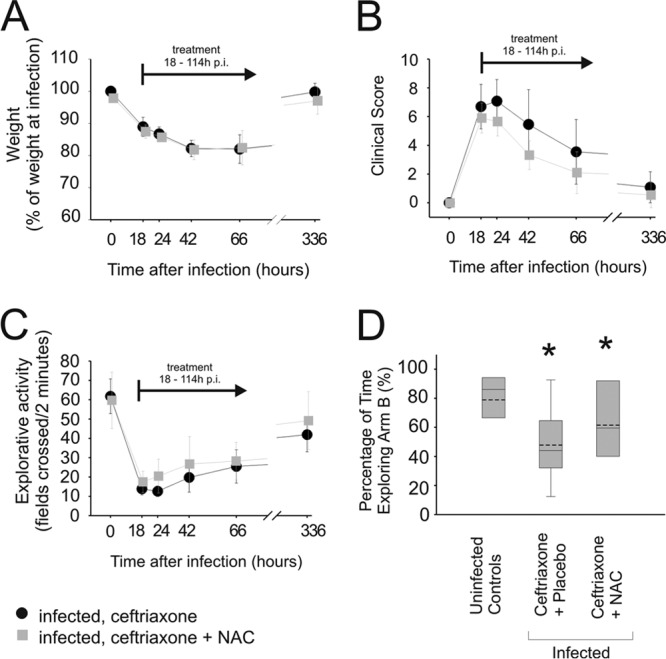

Fig 1.

Clinical signs of meningitis. All infected mice showed clinical signs of disease 18 h after injection, reflected in significant weight loss (A), an elevated clinical score (B), and reduced explorative activity (C). (D) Two weeks after injection, animals also suffered from impaired memory function as observed by a reduction of memory function: whereas healthy animals that had received an injection of sterile saline 2 weeks earlier spent only a little time in the previously explored arm of a T-shaped box and almost 85% of the time in a previously unknown arm, infected mice tended to explore both arms equally [data displayed were calculated with the formula “time spent in previously closed arm B/(time in arm A plus time in arm B)”]. See Materials and Methods for parameters shown by box plots. *, P < 0.05. An effect of NAC on weight loss (A), clinical score (B), explorative activity (C), or memory function was not observed (D).

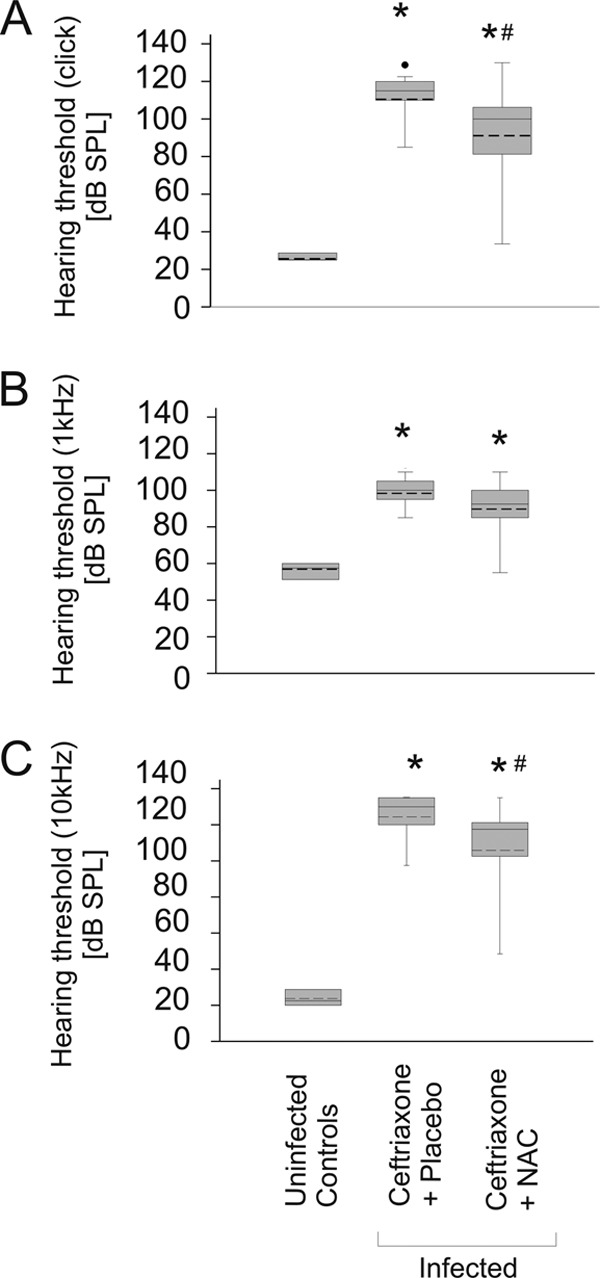

Fig 2.

Adjunctive NAC therapy only has a mild effect on hearing loss. Mice were assessed for click stimuli (A), low-frequency hearing (1-kHz stimuli) (B), and high-frequency hearing (10-kHz stimuli) (C). In infected animals, a significant increase of hearing thresholds was observed. The elevation of hearing thresholds was most severe for high-frequency hearing. Adjunctive treatment with NAC mildly improved hearing for click (A) and 10-kHz stimuli (C) but not for 1-kHz stimuli (B) compared to the thresholds in mice treated with ceftriaxone plus placebo. *, P < 0.05 compared to uninfected controls; #, P < 0.05 compared to infected animals treated with ceftriaxone and placebo.

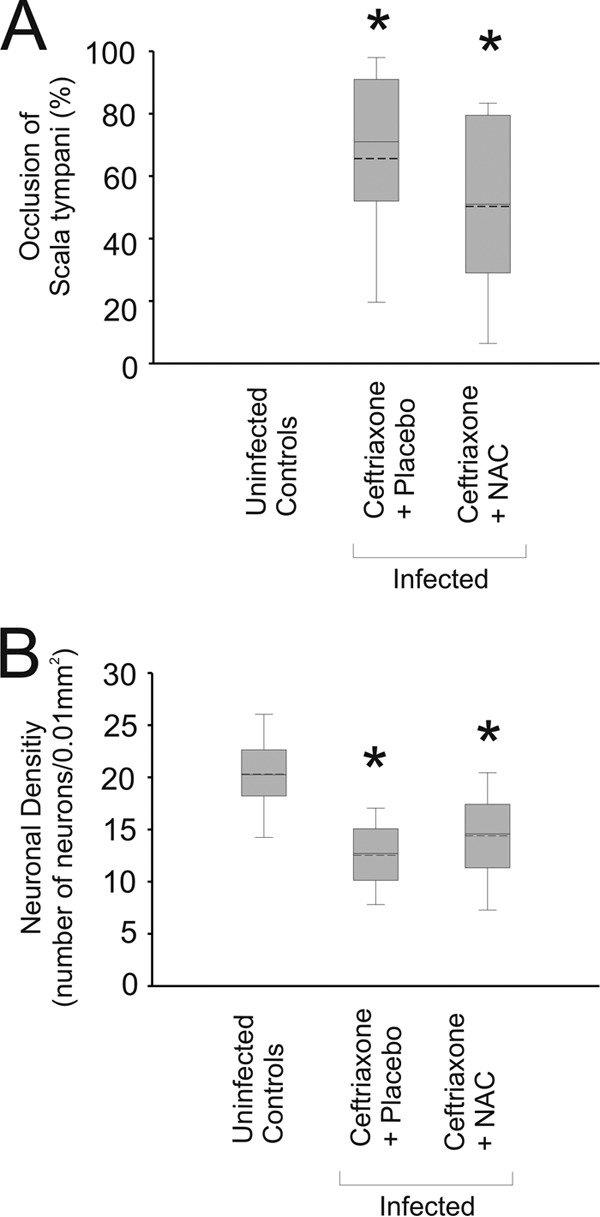

Fig 4.

Adjunctive NAC does not decrease spiral ganglion neuronal loss. Pneumococcal meningitis led to significant occlusion of the scala tympani (A) and a reduction of the neuronal cell counts in the spiral ganglion (B). Adjunctive therapy with NAC was not able to significantly reduce the occlusion of the scala tympani (A) and failed to significantly counteract the loss of neurons in the spiral ganglion (B) after pneumococcal meningitis. *, P < 0.05 compared to uninfected controls.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of meningitis.

At the time point when antibiotic therapy was begun, 18 h after infection, all infected mice displayed clinical signs of bacterial meningitis. This was reflected in an increase of the clinical score, reduced explorative activity, and substantial weight loss. The clinical condition of the infected mice improved within the first 24 h after the beginning of therapy. Two weeks after infection, the severity of clinical signs of acute meningitis had decreased and mice had regained weight (Fig. 1A). Only minor long-term residues were observed using the clinical score (Fig. 1B) and the explorative activity test (Fig. 1C). Memory function was impaired in mice after meningitis, since during the second exploration round of the t-maze test, infected animals spent equal times in the previously closed and yet-to-be-explored arm B of the T and in the previously explored arm A (Fig. 1D).

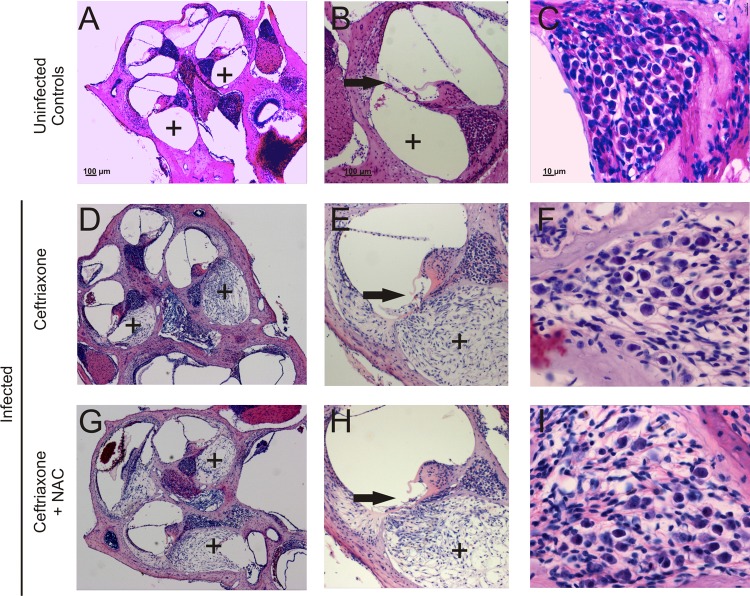

Infected mice that were treated with ceftriaxone and placebo suffered from hearing impairment (Fig. 2), which was aggravated for high frequencies (Fig. 2C). The main morphological correlates of hearing impairment were occlusion of the scala tympani by loose fibrocytic tissue and loss of neurons in the spiral ganglion (Fig. 3 and 4). Matching the aggravation of hearing loss in the high-frequency hearing range (10 kHz), cochlear damage was most severe in the lower turns of the cochlea, where high-frequency hearing takes place.

Fig 3.

Pathological alterations in the cochlea. (A to C) Cochleae of uninfected control animals showed an intact cochlear architecture with patent scala tympani (plus signs) (A, B) and a dense population of neurons in the spiral ganglion (C). (D to F) In infected animals that were treated with ceftriaxone and placebo, dense fibrocytic occlusion of the scala tympani (plus signs) was observed (D, E) and neuronal density was decreased (F). (G to I) Adjunctive treatment with NAC did not result in significant changes of the fibrocytic cochlear occlusion (G, H). (I) Furthermore, adjunctive NAC therapy did not significantly rescue neuronal ganglion cells from death. Staining was performed with H&E.

Adjunctive NAC did not improve the clinical outcome.

Adjunctive therapy with NAC did not improve mortality in infected mice (mortality in mice receiving ceftriaxone and placebo was 3/15, versus 2/11 in mice receiving ceftriaxone and NAC; P = 1.00). The clinical score and the explorative activity were equal in both treatment groups (Fig. 1B and C). Memory function that was impaired in infected mice as assessed by using the t-maze was not improved by adjunctive therapy with NAC (Fig. 1D).

Adjunctive NAC had a mild effect on hearing loss.

Therapy with ceftriaxone and adjunctive NAC showed a significant but mild improvement of hearing loss compared to therapy with ceftriaxone and placebo at 2 weeks after infection (Fig. 2). In animals who received ceftriaxone and NAC, the hearing thresholds were slightly lower for click stimuli (110- ± 16-dB SPL [mean ± standard deviation] with ceftriaxone and placebo versus 89- ± 27-dB SPL with ceftriaxone and NAC; P = 0.02) and for 10-kHz stimuli (124- ± 15-dB SPL with ceftriaxone and placebo versus 106- ± 26-dB SPL with ceftriaxone and NAC; P = 0.02). For 1-kHz stimuli, the reduction in hearing loss did not reach statistical significance (98- ± 9-dB SPL with ceftriaxone and placebo versus 90- ± 15-dB SPL with ceftriaxone and NAC; P = 0.06).

Adjunctive NAC failed to protect animals from cochlear damage.

Adjunctive therapy with NAC only led to a mild but nonsignificant reduction of fibrocytic occlusion in comparison to that in animals who received ceftriaxone and placebo (P = 0.13) (Fig. 4A). Adjuvant therapy with NAC also did not lead to a significant increase of intact neurons in the spiral ganglion in comparison with the amount of intact neurons in animals who were treated with ceftriaxone only (P = 0.18) (Fig. 4B). In summary, adjunctive therapy with NAC did not protect animals from long-term structural damage to the cochlea.

DISCUSSION

The major findings of this study were that adjunctive therapy with NAC (i) had a mild positive effect on meningitis-associated hearing loss but failed to protect mice with pneumococcal meningitis from (ii) death, (iii) memory loss, or (iv) cochlear damage.

The mouse model that was used mimics the disease course in humans with pneumococcal meningitis very well. This is reflected by the fact that the typical complications of pneumococcal meningitis are found (38) and that mortality was 20% in infected animals. This is very similar to the mortality seen in humans in central Europe (2, 3). Furthermore, we previously found that adjunctive dexamethasone significantly decreased hearing loss and its morphological correlates in the model of pneumococcal meningitis that was used here (34). Likewise, such a positive otoprotective effect of dexamethasone has been shown in adult patients with pneumococcal meningitis (39). Altogether, this underscores that the mouse model used here is clinically relevant and mimics the clinical situation in its value in the assessment of adjunctive treatment options.

Given the very promising results of previously published studies, the mild effect of NAC was somewhat surprising. Possibly, the difference of the power of NAC to reduce the otologic sequelae may be related to differences in the animal models used. Indeed, compared with the hearing thresholds in uninfected control animals, the hearing thresholds were elevated by 60 dB in rats with meningitis (25), whereas the hearing thresholds were up to 90 dB higher in mice with meningitis (current study). This may be related to a higher vulnerability of mice to cochlear damage, as evidenced by differences in histopathology. For example, infected mice often develop hemorrhages in the spiral ganglion, which are usually not found in rats with pneumococcal meningitis-associated hearing loss (29, 40). Also, different pneumococcal serotypes were used in the two experimental setups, namely, serotype 3 in the rat model (25) and serotype 2 in this current mouse model. As differences in pneumococcal serotype are known to account for differences in the development of hearing loss in adults with pneumococcal meningitis (41) and pathophysiologic alterations in animal models of pneumococcal meningitis (42), this may have added further to the variations seen between the two models.

Here, unlike in a very recent study on adult rats, memory function was not improved by NAC. Again, differences in the species (adult rats in the study from Barichello et al. [26] versus mice in our study) and a different pneumococcal serotype (serotype 3 in the study from Barichello et al. [26] versus serotype 2 in our study) may have contributed to the differences. Such differences were also reflected in the mortality rates: whereas about half of the animals died in the rat model, the mortality in mice was 20%. Furthermore, the diagnostic tests that were used to evaluate memory function were different. However, the missing effect of NAC on memory function in our study is in line with an earlier study in which pretreatment with NAC improved cortical but not hippocampal injury in an infant rat model of pneumococcal meningitis (23), and memory function is known to be located in the hippocampus.

It is also important to keep in mind that the effective dosage of NAC might have been different between rats and mice, as pharmacokinetics may vary among species. As the NAC dosage that was used here has been shown previously to be systemically effective in C57BL6 mice (43), we have not tested other regimens of NAC. However, we cannot rule out that species-dependent pharmacokinetics might be one factor that contributes to the variations in the results between this and the rat studies.

If compared with the data on dexamethasone in meningitis, the effect of NAC seems rather low: dexamethasone reduced hearing loss (for click, 1-kHz, and 10-kHz stimuli) and decreased the loss of spiral ganglion neuronal cells in the model that was also used in this study (34). Dexamethasone, which was shown to be effective in human patients in central Europe (3, 44), was of benefit not only in mice but also in meningitis models using adult rats, rabbits, and gerbils (34, 45–47). Nevertheless, even though dexamethasone seems of relatively strong benefit in these studies, its positive effect seems limited to patients treated in developed countries (39). Combined, the various results argue against a potential role of adjunctive treatment with NAC in patients with pneumococcal meningitis and against its evaluation in a clinical trial.

One limitation of this study is that we could not find an explanation for the discrepancy in there being a (minor) functional benefit of NAC on hearing whereas an effect on its morphological correlates was missing. Probably, this mainly reflects the fact that the effect of NAC was not very powerful in general. Furthermore, the evaluation of mouse cochleae was limited to meningitis-associated structural alterations that could be observed by histological techniques and a benefit of NAC in cochlear dysfunction that could possibly have resulted from other, nonvisible alterations, such as variations in the composition of the endolymph, or a nonstructural dysfunction of hair cells or neuronal cells may have been missed.

In summary, systemically applied adjunctive NAC at a dosage of 300 mg/kg of body weight intraperitoneally for 4 days was not powerful enough to ameliorate clinical parameters other than hearing loss after pneumococcal meningitis in our well-established mouse model of pneumococcal meningitis, and the overall effect on hearing was mild. Combined with data from previous studies, this study shows the importance of evaluating potential therapeutic agents for pneumococcal meningitis in more than one model before they can be taken under consideration for assessment in a human clinical trial.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sven Hammerschmidt (University of Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany) for providing the pneumococci. We thank Michael K. Schmidt for excellent technical assistance.

We are grateful for the financial aid of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), the Friedrich Baur Stiftung, and the Else Kroener Fresenius Foundation (EKFS) and the University of Munich (FöFoLe).

All authors declare that they do not have any competing interests.

The work presented here was carried out in collaboration between all authors. Experiments were planned by M.K., T.H., H.-W.P., and U.K. Experimental procedures were carried out by T.H., C.D., and M.K. with technical assistance from B.A. Histological assessment of slides was performed by T.H., M.K., U.K., and A.G. The manuscript was written by T.H. and M.K. and discussed and edited by all coauthors. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 July 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Brouwer MC, Tunkel AR, van de Beek D. 2010. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and antimicrobial treatment of acute bacterial meningitis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23:467–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kastenbauer S, Pfister HW. 2003. Pneumococcal meningitis in adults: spectrum of complications and prognostic factors in a series of 87 cases. Brain 126:1015–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brouwer MC, Heckenberg SG, de Bans J, Spanjaard L, Reitsma JB, van de Beek D. 2010. Nationwide implementation of adjunctive dexamethasone therapy for pneumococcal meningitis. Neurology 75:1533–1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auburtin M, Porcher R, Bruneel F, Scanvic A, Trouillet JL, Bedos JP, Regnier B, Wolff M. 2002. Pneumococcal meningitis in the intensive care unit: prognostic factors of clinical outcome in a series of 80 cases. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 165:713–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weisfelt M, van de Beek D, Spanjaard L, Reitsma JB, de Gans J. 2006. Clinical features, complications, and outcome in adults with pneumococcal meningitis: a prospective case series. Lancet Neurol. 5:123–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein M, Koedel U, Pfister HW. 2006. Oxidative stress in pneumococcal meningitis: a future target for adjunctive therapy? Prog. Neurobiol. 80:269–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kastenbauer S, Koedel U, Pfister HW. 1999. Role of peroxynitrite as a mediator of pathophysiological alterations in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. J. Infect. Dis. 180:1164–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kastenbauer S, Klein M, Koedel U, Pfister HW. 2001. Reactive nitrogen species contribute to blood-labyrinth barrier disruption in suppurative labyrinthitis complicating experimental pneumococcal meningitis in the rat. Brain Res. 904:208–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein M, Koedel U, Kastenbauer S, Pfister HW. 2008. Nitrogen and oxygen molecules in meningitis-associated labyrinthitis and hearing impairment. Infection 36:2–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paul R, Lorenzl S, Koedel U, Sporer B, Vogel U, Frosch M, Pfister HW. 1998. Matrix metalloproteinases contribute to the blood-brain barrier disruption during bacterial meningitis. Ann. Neurol. 44:592–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szabo C. 2003. Multiple pathways of peroxynitrite cytotoxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 140-141:105–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kastenbauer S, Koedel U, Becker BF, Pfister HW. 2002. Oxidative stress in bacterial meningitis in humans. Neurology 58:186–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abuja PM. 1999. Ascorbate prevents prooxidant effects of urate in oxidation of human low density lipoprotein. FEBS Lett. 446:305–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boje KM. 1995. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase partially attenuates alterations in the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier during experimental meningitis in the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 272:297–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kastenbauer S, Koedel U, Becker BF, Pfister HW. 2002. Pneumococcal meningitis in the rat: evaluation of peroxynitrite scavengers for adjunctive therapy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 449:177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koedel U, Pfister HW. 1997. Protective effect of the antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine in pneumococcal meningitis in the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 225:33–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leib SL, Kim YS, Black SM, Tureen JH, Tauber MG. 1998. Inducible nitric oxide synthase and the effect of aminoguanidine in experimental neonatal meningitis. J. Infect. Dis. 177:692–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loeffler JM, Ringer R, Hablutzel M, Tauber MG, Leib SL. 2001. The free radical scavenger alpha-phenyl-tert-butyl nitrone aggravates hippocampal apoptosis and learning deficits in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. J. Infect. Dis. 183:247–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winkler F, Koedel U, Kastenbauer S, Pfister HW. 2001. Differential expression of nitric oxide synthases in bacterial meningitis: role of the inducible isoform for blood-brain barrier breakdown. J. Infect. Dis. 183:1749–1759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly GS. 1998. Clinical applications of N-acetylcysteine. Altern. Med. Rev. 3:114–127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant LM, Rockey DC. 2012. Drug-induced liver injury. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 28:198–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millea PJ. 2009. N-acetylcysteine: multiple clinical applications. Am. Fam. Physician 80:265–269 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Auer M, Pfister LA, Leppert D, Tauber MG, Leib SL. 2000. Effects of clinically used antioxidants in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. J. Infect. Dis. 182:347–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christen S, Schaper M, Lykkesfeldt J, Siegenthaler C, Bifrare YD, Banic S, Leib SL, Tauber MG. 2001. Oxidative stress in brain during experimental bacterial meningitis: differential effects of alpha-phenyl-tert-butyl nitrone and N-acetylcysteine treatment. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 31:754–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein M, Koedel U, Pfister HW, Kastenbauer S. 2003. Meningitis-associated hearing loss: protection by adjunctive antioxidant therapy. Ann. Neurol. 54:451–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barichello T, Generoso JS, Collodel A, Moreira AP, Almeida SM. 2012. Pathophysiology of acute meningitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae and adjunctive therapy approaches. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 70:366–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonfanti L, Peretto P. 2011. Adult neurogenesis in mammals—a theme with many variations. Eur. J. Neurosci. 34:930–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mestas J, Hughes CC. 2004. Of mice and not men: differences between mouse and human immunology. J. Immunol. 172:2731–2738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein M, Schmidt C, Kastenbauer S, Paul R, Kirschning CJ, Wagner H, Popp B, Pfister HW, Koedel U. 2007. MyD88-dependent immune response contributes to hearing loss in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. J. Infect. Dis. 195:1189–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koedel U, Winkler F, Angele B, Fontana A, Flavell RA, Pfister HW. 2002. Role of caspase-1 in experimental pneumococcal meningitis: evidence from pharmacologic caspase inhibition and caspase-1-deficient mice. Ann. Neurol. 51:319–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koedel U, Angele B, Rupprecht T, Wagner H, Roggenkamp A, Pfister HW, Kirschning CJ. 2003. Toll-like receptor 2 participates in mediation of immune response in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. J. Immunol. 170:438–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koedel U, Rupprecht T, Angele B, Heesemann J, Wagner H, Pfister HW, Kirschning CJ. 2004. MyD88 is required for mounting a robust host immune response to Streptococcus pneumoniae in the CNS. Brain 127:1437–1445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferner RE, Dear JW, Bateman DN. 2011. Management of paracetamol poisoning. BMJ 342:d2218. 10.1136/bmj.d2218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Demel C, Hoegen T, Giese A, Angele B, Pfister HW, Koedel U, Klein M. 2011. Reduced spiral ganglion neuronal loss by adjunctive neurotrophin-3 in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. J. Neuroinflammation 8:7. 10.1186/1742-2094-8-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koedel U, Winkler F, Angele B, Fontana A, Pfister HW. 2002. Meningitis-associated central nervous system complications are mediated by the activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 22:39–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paul R, Winkler F, Bayerlein I, Popp B, Pfister HW, Koedel U. 2005. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor regulates leukocyte recruitment during experimental pneumococcal meningitis. J. Infect. Dis. 191:776–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deacon RM, Rawlins JN. 2006. T-maze alternation in the rodent. Nat. Protoc. 1:7–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klein M, Paul R, Angele B, Popp B, Pfister HW, Koedel U. 2006. Protein expression pattern in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. Microbes Infect. 8:974–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brouwer MC, McIntyre P, Prasad K, van de Beek D. 2013. Corticosteroids for acute bacterial meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 6:CD004405. 10.1002/14651858.CD004405.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caye-Thomasen P, Worsoe L, Brandt CT, Miyazaki H, Ostergaard C, Frimodt-Moller N, Thomsen J. 2009. Routes, dynamics, and correlates of cochlear inflammation in terminal and recovering experimental meningitis. Laryngoscope 119:1560–1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heckenberg SG, Brouwer MC, van der Ende A, Hensen EF, van de Beek D. 2012. Hearing loss in adults surviving pneumococcal meningitis is associated with otitis and pneumococcal serotype. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:849–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tauber MG, Burroughs M, Niemoller UM, Kuster H, Borschberg U, Tuomanen E. 1991. Differences of pathophysiology in experimental meningitis caused by three strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 163:806–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Downs I, Liu J, Aw TY, Adegboyega PA, Ajuebor MN. 2012. The ROS scavenger, NAC, regulates hepatic Valpha14iNKT cells signaling during Fas mAb-dependent fulminant liver failure. PLoS One 7:e38051. 10.1371/journal.pone.0038051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Gans J, van de Beek D. 2002. Dexamethasone in adults with bacterial meningitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:1549–1556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhatt SM, Cabellos C, Nadol JB, Jr, Halpin C, Lauretano A, Xu WZ, Tuomanen E. 1995. The impact of dexamethasone on hearing loss in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 14:93–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rappaport JM, Bhatt SM, Burkard RF, Merchant SN, Nadol JB., Jr 1999. Prevention of hearing loss in experimental pneumococcal meningitis by administration of dexamethasone and ketorolac. J. Infect. Dis. 179:264–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim HH, Addison J, Suh E, Trune DR, Richter CP. 2007. Otoprotective effects of dexamethasone in the management of pneumococcal meningitis: an animal study. Laryngoscope 117:1209–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]