Abstract

Methanol is considered an interesting carbon source in “bio-based” microbial production processes. Since Corynebacterium glutamicum is an important host in industrial biotechnology, in particular for amino acid production, we performed studies of the response of this organism to methanol. The C. glutamicum wild type was able to convert 13C-labeled methanol to 13CO2. Analysis of global gene expression in the presence of methanol revealed several genes of ethanol catabolism to be upregulated, indicating that some of the corresponding enzymes are involved in methanol oxidation. Indeed, a mutant lacking the alcohol dehydrogenase gene adhA showed a 62% reduced methanol consumption rate, indicating that AdhA is mainly responsible for methanol oxidation to formaldehyde. Further studies revealed that oxidation of formaldehyde to formate is catalyzed predominantly by two enzymes, the acetaldehyde dehydrogenase Ald and the mycothiol-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase AdhE. The Δald ΔadhE and Δald ΔmshC deletion mutants were severely impaired in their ability to oxidize formaldehyde, but residual methanol oxidation to CO2 was still possible. The oxidation of formate to CO2 is catalyzed by the formate dehydrogenase FdhF, recently identified by us. Similar to the case with ethanol, methanol catabolism is subject to carbon catabolite repression in the presence of glucose and is dependent on the transcriptional regulator RamA, which was previously shown to be essential for expression of adhA and ald. In conclusion, we were able to show that C. glutamicum possesses an endogenous pathway for methanol oxidation to CO2 and to identify the enzymes and a transcriptional regulator involved in this pathway.

INTRODUCTION

Methylotrophic microorganisms utilize reduced C1 compounds, such as methane, methylamines, or methanol, as a sole carbon and energy source and play an important role in the global carbon cycle (1, 2). A key step in methylotrophic metabolism is the oxidation of methanol to formaldehyde. Whereas this oxidation step is catalyzed by flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-dependent methanol oxidases with concomitant reduction of oxygen to hydrogen peroxide in methylotrophic yeast and fungi (3), Gram-negative methylotrophic bacteria, such as Methylobacterium extorquens, use pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ)-dependent methanol dehydrogenases to oxidize methanol in the periplasm (4). Gram-positive thermotolerant Bacillus strains usually contain NAD+-dependent cytoplasmic methanol dehydrogenases (5). In methylotrophic metabolism, cytotoxic formaldehyde represents a crucial central metabolic intermediate. The toxicity of formaldehyde arises from nonenzymatic reactions with biological macromolecules such as proteins and DNA, leading to irreversible alkylations and cross-linkages (6–8). Formaldehyde detoxification can occur either by assimilation into cell material or by oxidation to carbon dioxide (9, 10). Pathways for formaldehyde oxidation to CO2 are widely distributed and are not limited to methylotrophs, since virtually all organisms have to cope with toxic formaldehyde as a by-product of numerous environmental processes and various cellular demethylation and oxidation reactions. Hence, nature developed diverse strategies for its detoxification by efficient capture of formaldehyde by cofactors, such as glutathione, mycothiol, tetrahydrofolate, or tetrahydromethanopterin, and subsequent oxidation of the products (9, 10).

The soil bacterium Corynebacterium glutamicum can grow on various carbon sources, such as sugars, organic acids, alcohols, or aromatics, but presumably not on C1 compounds since none of the known assimilation pathways is encoded in the genome. In agreement, it was reported that C. glutamicum strain R does not grow on methanol (11). In industrial biotechnology, highly productive strains of C. glutamicum serve to produce several million tons of amino acids annually, in particular the flavor enhancer l-glutamate and the feed additive l-lysine. In addition, strains have been developed for a variety of other commercially interesting compounds (12), such as organic acids (13–15), diamines (16–18), or alcohols (19–21). Moreover, C. glutamicum is also an efficient host for the production of heterologous proteins (see reference 22 and references therein).

Since methanol can be produced from renewable carbon sources (23), it is an interesting carbon source for “bio-based” production of chemicals or proteins. As a first step toward the goal of making C. glutamicum a methylotroph, we studied the response of this organism to methanol at the metabolic level and at the gene expression level. As a result, we describe the identification and characterization of an endogenous pathway for the oxidation of methanol to CO2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used or constructed in the course of this work are listed in Table 1, and oligonucleotides are listed in in Table S1 in the supplemental material. C. glutamicum was routinely cultivated aerobically in 500-ml baffled shake flasks with 50 ml medium on a rotary shaker (120 rpm) at 30°C. Either LB medium (30) or modified CGXII minimal medium (29) containing 28 to 222 mM glucose and/or 100 mM ethanol as a carbon and energy source was used. Methanol was added to the culture medium in concentrations from 50 mM to 3,000 mM using a 5 M stock solution. For strain construction and maintenance, either LB or BHIS agar plates (brain heart infusion [BHI] agar [Difco, Detroit, MI, USA] supplemented with 0.5 M sorbitol) were used. Media used in the course of gene deletion using pK19mobsacB were described before (31). Escherichia coli DH5α was used for cloning purposes and was grown aerobically on a rotary shaker (170 rpm) at 37°C in 5 ml LB medium or on LB agar plates (LB medium with 1.8% [wt/vol] agar). If appropriate, kanamycin was added to final concentrations of 25 μg ml−1 (C. glutamicum) or 50 μg ml−1 (E. coli). Growth was determined by measuring of the optical density at 600 nm (OD600).

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | F− ϕ80dlacΔ(lacZ)M15 Δ(lacZYA-argF) U169 endA1 recA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) deoR thi-1 phoA supE44 λ− gyrA96 relA1 | Invitrogen (Karslruhe, Germany) |

| C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 | Biotin-auxotrophic wild-type strain | 24 |

| C. glutamicum ΔfdhF strain | Derivative of ATCC 13032 with in-frame deletion of fdhF gene | 25 |

| C. glutamicum ΔadhA strain | Derivative of ATCC 13032 with in-frame deletion of adhA gene | This work |

| C. glutamicum ΔadhC strain | Derivative of ATCC 13032 with in-frame deletion of adhC gene | This work |

| C. glutamicum ΔadhE strain | Derivative of ATCC 13032 with in-frame deletion of adhE gene | This work |

| C. glutamicum Δald strain | Derivative of ATCC 13032 with in-frame deletion of ald gene | This work |

| C. glutamicum Δcg2714 strain | Derivative of ATCC 13032 with in-frame deletion of cg2714 | This work |

| C. glutamicum Δcg0273 strain | Derivative of ATCC 13032 with in-frame deletion of cg0273 | This work |

| C. glutamicum Δald ΔadhE strain | Derivative of Δald strain with additional in-frame deletion of adhE gene | This work |

| C. glutamicum Δald Δcg0388 strain | Derivative of Δald strain with additional in-frame deletion of cg0388 | This work |

| C. glutamicum Δald Δcg2193 strain | Derivative of Δald strain with additional in-frame deletion of cg2193 | This work |

| C. glutamicum RG2 | Derivative of ATCC 13032 with partial deletion of ramA gene | 26 |

| C. glutamicum ΔmshC strain | Derivative of ATCC 13032 with in-frame deletion of mshC gene | 27 |

| C. glutamicum Δald ΔmshC strain | Derivative of Δald strain with additional in-frame deletion of mshC gene | This study |

| C. glutamicum ΔadhA/pAN6-adhA strain | Plasmid-based complementation of adhA deletion | This work |

| C. glutamicum ΔadhA/pAN6 strain | Control strain | This work |

| C. glutamicum Δald/pAN6-ald strain | Plasmid-based complementation of ald deletion | This work |

| C. glutamicum ΔadhE/pAN6-adhE strain | Plasmid-based complementation of adhE deletion | This work |

| C. glutamicum Δald ΔadhE/pAN6-ald-adhE strain | Plasmid-based complementation of ald-adhE deletion | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pK19mobsacB | Kanr; mobilizable E. coli vector used for allelic exchange in C. glutamicum (pK18 oriVE.c. oriT sacB lacZ) | 28 |

| pK19ΔadhA | Kanr; pK19mobsacB derivative containing 1,010-bp PCR product covering upstream and downstream regions of adhA | This work |

| pK19ΔadhC | Kanr; pK19mobsacB derivative containing 966-bp PCR product covering upstream and downstream regions of adhC | This work |

| pK19Δald | Kanr; pK19mobsacB derivative containing 1,017-bp PCR product covering upstream and downstream regions of ald | This work |

| pK19ΔadhE | Kanr; pK19mobsacB derivative containing 1,042-bp PCR product covering upstream and downstream regions of adhE | This work |

| pK19Δcg0273 | Kanr; pK19mobsacB derivative containing 1,037-bp PCR product covering upstream and downstream regions of cg0273 | This work |

| pK19Δcg2714 | Kanr; pK19mobsacB derivative containing 1,084-bp PCR product covering upstream and downstream regions of cg2714 | This work |

| pK19Δcg0388 | Kanr; pK19mobsacB derivative containing 1,089-bp PCR product covering upstream and downstream regions of cg0388 | This work |

| pK19Δcg2193 | Kanr; pK19mobsacB derivative containing 1,063-bp PCR product covering upstream and downstream regions of cg2193 | This work |

| pK18mobsacBΔncgl1457 | Kanr; pK18mobsacB derivative containing PCR product covering upstream and downstream regions of ncgl1457 (mshC) | 27 |

| pAN6 | Kanr; C. glutamicum/E. coli shuttle vector; derivative of pEKEx2 (Ptac, lacIq, pBL1 oriVC.g., pUC18 oriVE.c.) | 29 |

| pAN6-adhA | Kanr; pAN6 derivative containing adhA under control of Ptac | This work |

| pAN6-ald | Kanr; pAN6 derivative containing ald under control of Ptac | This work |

| pAN6-adhE | Kanr; pAN6 derivative containing adhE under control of Ptac | This work |

| pAN6-ald-adhE | Kanr; pAN6 derivative containing ald and adhE under control of Ptac | This work |

Recombinant DNA techniques.

The enzymes for recombinant DNA work were obtained from Fermentas (St. Leon-Rot, Germany) and Merck Millipore (Billerica, Massachusetts, USA). Chromosomal DNA from C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 was prepared as described previously (32). E. coli was transformed by the RbCl method (33) and C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 by electroporation (34). Routine methods like PCR, restriction, or ligation were carried out according to standard protocols (30). The oligonucleotides used for cloning were obtained from Eurofins MWG Operon (Ebersberg, Germany) and are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The in-frame gene deletion mutants of C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 were constructed via a two-step homologous recombination procedure as described previously (31). The deletions in the chromosome were verified by PCR analysis using oligonucleotides hybridizing approximately 500 bp upstream and 500 bp downstream of the target gene (see Table S1). The coding regions of adhA (cg3107), ald (cg3096), and adhE (cg0387) were amplified by PCR using the oligonucleotide pairs P_adhA_fw_NdeI/P_adhA_rev_NheI, P_ald_fw_NdeI/P_ald_rev_NheI, and P_adhE_fw_NdeI/P_adhE_rev_NheI, respectively (see Table S1), digested with NdeI and NheI, and cloned into the expression vector pAN6 for complementation studies. The cloned regions were checked by DNA sequencing using plasmid-specific primers (see Table S1).

Determination of glucose and formate by HPLC.

The concentrations of glucose and formate in cell-free culture supernatants were determined by HPLC analysis using an Agilent 1100 system (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) equipped with a cation exchange column (organic acid refill column, 300 by 8 mm [CS-Chromatographie Service GmbH, Langerwehe, Germany]) as described previously (35).

Determination of methanol by gas chromatography.

The quantitative detection of methanol in the cell-free supernatant of C. glutamicum cultures was performed via capillary gas chromatography (GC) using an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany)] equipped with an HP-5 column [(5% phenyl)-methylpolysiloxane, 30 m, 0.32 mm, 0.25 μm (Agilent Technologies Waldbronn, Germany)]. Helium was used as a carrier gas with a flow rate of 2.8 ml/min. The sample (1 μl) was injected via split injection (1:50), employing a Combi PAL GC autosampler (CTC Analytics GmbH, Zwingen, Germany). The injector temperature was set to 250°C, and the column temperature was kept constant at 40°C. Detection was performed using a flame ionization detector (FID) at a detector temperature of 250°C. Calibration was performed with methanol as an external standard. Butanol (60 mM) was used as an internal standard and was added to the samples in the same volume ratio. Concentrations were calculated from peak areas using calibration with external methanol and internal butanol standards.

Determination of formaldehyde.

Formaldehyde concentrations were determined via a colorimetric photometric assay as described by Nash (36). This assay is based on the condensation of acetylacetone and free formaldehyde in the presence of excess ammonium salt to the chromophore diacetyldihydrolutidine (Hanztsch reaction), which is characterized by an absorption maximum at 412 nm and an extinction coefficient of 7.7 mM−1 cm−1. For the determination of formaldehyde concentrations, samples of 0.5 ml cell-free culture supernatant were taken at various time points during cultivation, mixed with 0.5 ml Nash reagent (2 M ammonium acetate, 50 mM acetic acid, and 20 mM acetylacetone), and incubated for 10 min at 60°C. Subsequently, the absorption at 412 nm was measured for each sample. A calibration curve showed that the assay was linear between 20 μM and 1.5 mM formaldehyde.

DNA microarray analysis.

Whole-genome DNA microarray analyses were performed to monitor changes in the global gene expression of the C. glutamicum wild type in response to the presence of methanol. Cells of a preculture in LB medium were used to inoculate a second preculture in CGXII minimal medium with 111 mM glucose. To test the influence of methanol in the presence of glucose, two parallel main cultures in CGXII minimal medium with 111 mM glucose were inoculated with the second preculture to an OD600 of 0.5. After reaching an OD600 of 5, 100 mM methanol was added to one culture, whereas water was added to the second one as a control. After continuing incubation for 30 min, cells of both cultures were harvested in precooled (−20°C) ice-filled tubes via centrifugation (6,900 × g, 10 min, 4°C) and used for RNA isolation. To test the influence of methanol in the absence of glucose, a preculture in CGXII medium with 111 mM glucose was incubated until an OD600 of 8 was reached. Cells were washed with CGXII minimal medium without a carbon source and resuspended in this medium to an OD600 of 5. The cell suspensions were incubated for 2 h, and then 100 mM methanol was added to one of the suspensions and water to the second one. After incubation for another 30 min, cells were harvested and used for RNA isolation.

RNA isolation and synthesis of fluorescently labeled cDNA were carried out as described previously (37). For cDNA synthesis, 25 μg total RNA of each sample was used. Custom-made DNA microarrays for C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 printed with 70-er oligonucleotides were obtained from Operon (Cologne, Germany) and were based on the genome sequence entry NC_006958 (38). Processing of DNA microarrays and evaluation of the obtained data were performed as previously described (29). The normalized and processed data were saved in the in-house microarray database (39). All DNA microarray experiments were performed in three replicates.

Determination of alcohol dehydrogenase activities in crude extracts.

For the determination of alcohol dehydrogenase activity in vitro, the C. glutamicum wild type was cultivated in CGXII minimal medium either with 56 mM glucose, with 56 mM glucose and 100 mM ethanol, or with 56 mM glucose and 100 mM methanol. Cells were grown until the early stationary phase (OD600 of ∼22), and 50-ml culture samples were harvested by centrifugation for 15 min at 4,500 × g and 4°C. After washing in 25 ml buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl and 30% [vol/vol] glycerol, pH 7.5), cells were resuspended in 2 ml 100 mM Tris-HCl, 30% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 1 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.5. Cells were disrupted by sonication (6 min; cycle, 0.5; amplitude, 50) using a UP200S sonifier (Hielscher GmbH, Stuttgart, Germany) with cooling on ice. After centrifugation (30 min, 16,000 × g, 4°C), the supernatant was used for enzyme assays. The protein concentration of the cell extracts was determined by the method of Bradford (40) using bovine serum albumin as the standard. The assay was performed as described previously (11) with slight modifications. The assay mixtures (1 ml total volume) contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.6), 4 mM NAD+, and 10 μl cell extract. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 340 mM ethanol and monitored by following the increase in absorption at 340 nm over 2 min using an Ultraspec 3100pro photometer (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Freiburg, Germany) at 30°C. One unit of alcohol dehydrogenase activity is defined as the reduction of 1 μmol NAD+ per minute.

Determination of 13CO2 and 12CO2.

The conversion of methanol to CO2 by C. glutamicum was monitored in 13C labeling experiments. Cells were grown in 200 ml CGXII medium with 56 mM glucose in a Dasgip parallel bioreactor system (Dasgip AG, Jülich, Germany), and 100 mM 13C-labeled methanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the culture medium immediately before inoculation. During cultivation, pH, dissolved oxygen concentration, and off-gas (CO2 and O2) were monitored online via the Dasgip monitoring system (Dasgip Control 4.0). Whereas the pH was not controlled during cultivation, the dissolved O2 saturation was kept at >30%, varying the stirrer speed between 400 and 1,200 rpm at a constant airflow rate of 4 standard liters (sl)/h. If required, antifoam 204 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added. Growth was monitored offline by OD600 measurements. 13CO2 and 12CO2 off-gas analysis and quantification were performed using an FT-IR gas analyzer (Gasmet CR-2000i [Ansyco, Karlsruhe, Germany]) and the Calcmet software program, version 10 (Gasmet Technologies Oy, Helsinki, Finland).

Microarray data accession number.

The microarray data were deposited in the GEO database with the accession number GSE49936.

RESULTS

Methanol is metabolized by C. glutamicum in stationary growth phase.

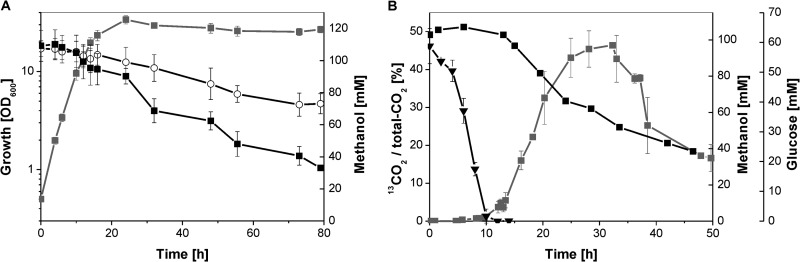

Initial cultivation experiments of the C. glutamicum wild type in CGXII minimal medium containing 111 mM glucose and methanol at concentrations ranging from 0.05 M to 3 M showed that the growth rate (μ) decreased with increasing methanol concentrations. The following values were obtained: 0.41 h−1 at 0 mM, 0.33 h−1 at 0.05 M, 0.28 h−1 at 0.1 M, 0.24 h−1 at 0.2 M, 0.21 h−1 at 0.7 M, 0.19 h−1 at 1 M, 0.17 h−1 at 1.3 M, and 0.09 h−1 at 1.5 M (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). At 3 M methanol, growth was almost completely inhibited. Cultivation experiments in minimal medium with 111 mM glucose and 120 mM methanol revealed that the C. glutamicum wild type consumes methanol against the background of methanol evaporation with a rate of 63.2 μmol h−1 (g cell dry weight [CDW])−1 (Fig. 1A). After 72 h of cultivation, only 41 mM methanol remained in the minimal medium, whereas 73 mM methanol could be detected in the control flask without C. glutamicum cells. Since C. glutamicum was not able to grow on methanol as a sole carbon source and does not possess one of the known pathways for methanol assimilation (data not shown), we assumed that methanol is oxidized to CO2. To test this assumption, cultivation experiments were performed in bioreactors using CGXII minimal medium with 56 mM glucose and 100 mM 13C-labeled methanol. During these experiments, 13C-labeled CO2 was detected by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) as soon as methanol consumption started in the stationary growth phase, when glucose had been completely consumed (Fig. 1B).

Fig 1.

(A) Methanol consumption (■) and growth (■, in gray) of the C. glutamicum wild type in CGXII minimal medium supplemented with 111 mM glucose and 120 mM methanol. Four independent experiments were performed in shake flasks, always accompanied by a methanol evaporation control without cells (○). (B) 13CO2 formation as 13CO2/total CO2 ratio (■, in gray), methanol consumption (■), and glucose consumption (▼) during growth of the C. glutamicum wild type in bioreactors with 56 mM glucose in the presence of 100 mM 13C-labeled methanol. The C. glutamicum wild type showed a growth rate of 0.27 ± 0.01 h−1 and a final OD600 of 20.4 ± 1.8.

FdhF is responsible for oxidation of formate to carbon dioxide.

Oxidation of methanol to CO2 is catalyzed stepwise by specific dehydrogenases via the intermediates formaldehyde and formate (10). Whereas no genes coding for methanol-or formaldehyde dehydrogenase have been annotated in the genome of C. glutamicum (41, 42), we recently identified genes coding for a molybdenum-containing formate dehydrogenase (25). To test the involvement of this enzyme in methanol oxidation, growth experiments similar to those described for Fig. 1A were conducted with a C. glutamicum ΔfdhF mutant (25), which resulted in a slightly reduced methanol consumption (27 mM ± 4 mM) compared to that of the wild type (34 mM ± 6 mM) after 72 h against an evaporation background. Most important, the mutant formed an equimolar concentration of formate (27 mM ± 2 mM) in the culture supernatant, whereas the wild type formed only 18 mM ± 4 mM. This result shows that FdhF is responsible for formate oxidation to CO2 in the wild type and confirms that methanol or formaldehyde is not assimilated by C. glutamicum. Additionally, the formate accumulation during growth of the wild type in methanol-containing medium indicated that the oxidation of formate to CO2 is the limiting factor in the endogenous methanol oxidation pathway in C. glutamicum.

Search for genes involved in methanol oxidation to CO2 by global gene expression analysis.

In order to identify genes that might be involved in the oxidation of methanol and formaldehyde, we tested the influence of methanol on global gene expression using DNA microarray analysis. Gene expression was considered to be influenced by methanol if mRNA levels in at least two out of three biological replicates differed from those of the control without methanol. In total, 20 genes were up- and 19 genes were downregulated in the presence of 100 mM methanol (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Interestingly, two genes known to be essential for the oxidation of ethanol to acetate in C. glutamicum were among the upregulated genes: adhA (cg3107; 4.4-fold), encoding an alcohol dehydrogenase (11, 43), and ald (cg3096; 2.1-fold), encoding acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (44).

Besides adhA, four other genes have been annotated as putative alcohol dehydrogenase genes in the genome of C. glutamicum (43): cg0273, cg0387 (adhE), cg0400 (adhC), and cg2714. Their expression levels were not altered in the presence of methanol. To determine the relevance of adhA, ald, and the other putative alcohol dehydrogenase genes for methanol or formaldehyde oxidation in C. glutamicum, in-frame deletion mutants lacking these genes were constructed and characterized.

AdhA is mainly responsible for oxidation of methanol to formaldehyde.

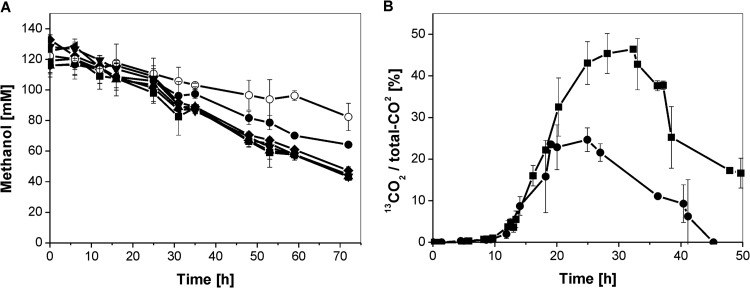

The ΔadhA, ΔadhC, ΔadhE, Δcg2714, and Δcg0273 C. glutamicum deletion mutants were analyzed regarding their ability to oxidize methanol. All deletion mutants showed the same growth behavior in CGXII medium containing 111 mM glucose and 120 mM methanol (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). However, whereas the methanol oxidation rate of the ΔadhC, ΔadhE, Δcg2714, and Δcg0273 strains (70.0 ± 20, 73 ± 4, 70 ± 4, and 61 ± 3 μmol h−1 [g CDW]−1, respectively) were similar to that of the wild type (63.3 ± 10 μmol h−1 [g CDW]−1), the rate for the ΔadhA mutant was reduced by about 62%, to 26.1 ± 6.1 μmol h−1 (g CDW)−1 (Fig. 2A). Complementation of the ΔadhA strain with the expression plasmid pAN6-adhA (plus 1.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside [IPTG]) restored the wild-type methanol oxidation rate (data not shown). [13C]Methanol labeling experiments confirmed the participation of AdhA in methanol oxidation, since the ΔadhA mutant generated 60% less 13CO2 than the wild type (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that the first step in methanol oxidation by C. glutamicum is predominantly catalyzed by AdhA but that at least one additional dehydrogenase of hitherto unknown identity is also involved.

Fig 2.

(A) Methanol oxidation of C. glutamicum wild type (■), ΔadhA strain (●), ΔadhC strain (▲), ΔadhE strain (▼), Δcg2714 strain (♦), and Δcg0273 strain (◀) in CGXII minimal medium supplemented with 111 mM glucose and 120 mM methanol. Two to four independent experiments in shake flasks were performed, always accompanied by a methanol evaporation control (○). (B) 13CO2 formation as 13CO2/total CO2 ratio of C. glutamicum wild type (■) and ΔadhA strain (●) during cultivation in bioreactors in the presence of 100 mM 13C-labeled methanol. Experiments to determine 13CO2 generation in the C. glutamicum wild type were performed in triplicate and those for the ΔadhA mutant in duplicate. Mean values are shown.

Enzyme assays with C. glutamicum crude extracts revealed that cells cultivated in minimal medium with 56 mM glucose and 100 mM methanol possessed a 3-fold higher alcohol dehydrogenase activity (280 ± 22 U/g protein) in stationary phase than cells grown solely with 56 mM glucose (96 ± 60 U/g), suggesting that adhA expression is induced by methanol. Previous studies with C. glutamicum strain R are in agreement with this result (11).

Ald oxidizes formaldehyde to formate.

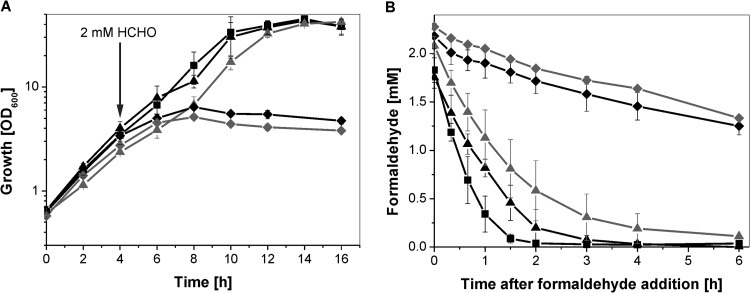

In preliminary experiments, we tested growth of the C. glutamicum wild type in the presence of various concentrations of formaldehyde. In the presence of 2 mM formaldehyde, it showed a slight growth inhibition, and it showed a strong growth defect at 4 mM formaldehyde (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). As displayed in Fig. 3A, growth of the Δald mutant was slightly more inhibited by 2 mM formaldehyde than growth of the wild type, indicating a decreased ability of the mutant to metabolize formaldehyde. This was confirmed by the finding that the rate of formaldehyde disappearance as measured by the Nash assay was only 0.66 ± 0.1 mM formaldehyde h−1 for the Δald mutant, but it was 1.17 mM ± 0.18 mM h−1 for the wild type (Fig. 3B). Complementation of the Δald mutant with the expression plasmid pAN6-ald (plus 0.3 mM IPTG) led to a formaldehyde oxidation rate of 2.2 mM ± 0.3 mM h−1. These results clearly indicate that Ald plays an important role in formaldehyde oxidation to formate but that another enzyme involved in formaldehyde consumption must be present in C. glutamicum.

Fig 3.

Growth(A) or formaldehyde oxidation (B) of C. glutamicum wild type (■) and Δald (●), ΔadhE (▲, in gray), Δcg0273 (▼, in gray), and Δald ΔadhE (♦) mutant strains in CGXII minimal medium with 111 mM glucose. After cultivation for 4 h, 2 mM formaldehyde was added (indicated by an arrow in panel A). Mean values and standard deviations for three biological replicates are shown, always accompanied by an evaporation control (○).

Mycothiol-dependent oxidation of formaldehyde via AdhE.

Inspection of the genome sequence of C. glutamicum for further candidates involved in formaldehyde oxidation led to the identification of Cg0387 (AdhE). As mentioned above, AdhE is annotated as alcohol dehydrogenase but shares 66 to 69% amino acid sequence identity to mycothiol-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenases of Amycolatopsis methanolica (45), Mycobacterium smegmatis (46), and Rhodococcus erythropolis (47). These proteins catalyze the NAD+-dependent oxidation of a spontaneously formed product of mycothiol and formaldehyde, S-hydroxymethyl-mycothiol, to S-formyl-mycothiol, which can subsequently be hydrolyzed to formate and mycothiol (48–50). Similar to the case with the C. glutamicum Δald strain, the deletion of adhE resulted in slightly impaired growth in the presence of 2 mM formaldehyde (Fig. 3A), and the rate of formaldehyde disappearance was reduced to 0.74 ± 0.06 mM h−1, compared to 1.17 mM ± 0.18 mM h−1 observed for the wild type (Fig. 3B). Complementation of the ΔadhE mutant with the expression plasmid pAN6-adhE (plus 0.3 mM IPTG) led to a formaldehyde oxidation rate of 1.7 mM ± 0.7 mM h−1. Thus, besides Ald, AdhE is also involved in formaldehyde oxidation in C. glutamicum.

To test for additional formaldehyde oxidation enzymes, the C. glutamicum Δald ΔadhE double mutant was constructed and characterized. As shown in Fig. 3A, growth of the Δald ΔadhE strain stopped shortly after addition of 2 mM formaldehyde to the minimal medium, and formaldehyde consumption was almost completely prevented (Fig. 3B). Plasmid-based expression of ald and adhE in the C. glutamicum Δald ΔadhE strain with pAN6-ald-adhE (plus 0.3 mM IPTG) restored the ability to oxidize formaldehyde (2.3 mM ± 0.1 mM h−1). [13C]Methanol labeling experiments further confirmed the participation of Ald and AdhE in the methanol oxidation pathway, since the Δald ΔadhE strain generated 75% less 13CO2/total CO2 than the wild type (data not shown). However, 13CO2 was still generated, and although the methanol oxidation rate of the Δald ΔadhE strain was lower than that of the wild type (32.9 ± 3.3 μmol h−1 [g CDW]−1 versus 63.3 ± 10 μmol h−1 [g CDW]−1), C. glutamicum possesses another possibility for detoxifying formaldehyde besides using Ald and AdhE.

To verify the mycothiol-dependence of AdhE in C. glutamicum, a strain deficient in mycothiol biosynthesis (C. glutamicum ΔmshC [27]) was investigated regarding its capability to oxidize formaldehyde. The deletion of mshC resulted in an impaired growth in the presence of 2 mM formaldehyde (Fig. 4A), and similar to the case with the C. glutamicum ΔadhE strain, the formaldehyde oxidation rate was reduced (0.54 mM ± 0.11 mM h−1) in comparison to that of the wild type (1.7 mM ± 0.7 mM h−1) (Fig. 4B). In addition, the C. glutamicum Δald ΔmshC double deletion mutant was constructed. It showed a phenotype similar to that of the C. glutamicum Δald ΔadhE strain, with respect to growth and its capability to oxidize formaldehyde; growth stopped shortly after addition of 2 mM formaldehyde to the minimal medium, and formaldehyde consumption was almost completely prevented (Fig. 4B). These results clearly support that formaldehyde oxidation by AdhE is strictly dependent on mycothiol.

Fig 4.

Growth (A) or formaldehyde oxidation (B) of C. glutamicum wild type (■) and ΔadhE (▲), ΔmshC (▲, in gray), Δald ΔadhE (♦), and ΔaldΔmshC (♦, in gray) mutant strains in CGXII minimal medium with 111 mM glucose. After cultivation for 4 h, 2 mM formaldehyde was added (indicated by an arrow in panel A). Mean values and standard deviations for three biological replicates are shown.

Three possible pathways for conversion of S-formyl-mycothiol were reported: spontaneous hydrolysis to formate and mycothiol, hydrolysis to formate and mycothiol by an S-formyl-mycothiol hydrolase (FMH), or oxidation by a molybdoprotein aldehyde dehydrogenase to S-carboxy-mycothiol, which spontaneously decomposes to carbon dioxide and mycothiol (46, 51). The latter possibility appears unlikely for C. glutamicum, since the ΔfdhF mutant converted methanol stoichiometrically to formate. The gene located immediately downstream of adhE in C. glutamicum, cg0388, is annotated as Zn-dependent hydrolase, and the derived protein sequence has 65% sequence identity to that of the proposed R. erythropolis FMH (47). In addition, the putative lysophospholipase (cg2193) shows 38% sequence identity to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv2854 protein, which is expected to be an FMH. It is located in an operon with the NADPH-dependent mycothiol reductase gene mtr, and the organization of these genes is conserved in most mycobacteria and corynebacteria, as well as in C. glutamicum (49).

To test the role of the genes cg0388 and cg2193 in methanol oxidation, both genes were individually deleted in the C. glutamicum Δald background. Growth experiments in CGXII minimal medium containing 56 mM glucose and 120 mM methanol revealed that the C. glutamicum Δald Δcg0388 strain and the C. glutamicum Δald Δcg2193 strains accumulate as much formate (15.1 ± 0.5 mM and 17.5 ± 0.5 mM, respectively) within 60 h as the wild type (16.7 ± 0.4 mM) and significantly more than the Δald ΔadhE mutant (6.1 ± 0.7 mM), suggesting that neither Cg0388 nor Cg2193 is essential for conversion of S-formyl-mycothiol to mycothiol and formate, but this does not exclude that they possess such an activity. These results hint at a spontaneous hydrolysis of S-formyl-mycothiol to formate and mycothiol.

Methanol consumption by C. glutamicum is subject to catabolite repression.

As shown above (Fig. 1), methanol oxidation is subject to carbon catabolite repression by glucose, since it starts in the stationary growth phase after glucose has been consumed. Such a behavior is quite unusual for C. glutamicum, since the majority of carbon sources, such as acetate (52) and gluconate (29), are consumed in parallel by this bacterium. Two known exceptions are glutamate (53) and ethanol (11, 54). In the case of ethanol, adhA expression was shown to be subject to a complex transcriptional control involving RamA as an essential activator and RamB and SucR as repressors (43, 55). RamA and RamB are global transcriptional regulators in C. glutamicum and control genes for enzymes of the central metabolism (26, 56, 57). SucR is now termed AtlR (58). In the case of ald, RamA was described as an essential activator and RamB as a weak repressor (44). Since AdhA was shown to be the major enzyme responsible for methanol oxidation to formaldehyde, we tested methanol consumption by a C. glutamicum ΔramA mutant (26) and observed that its capability to oxidize methanol was strongly reduced (see Fig. S4A in the supplemental material) and was comparable to that of a ΔadhA mutant. Further support for the methanol oxidation defect of the ΔramA mutant was obtained by [13C]methanol labeling experiments. They revealed that the ΔramA mutant produced 86% less 13CO2/total CO2 than the wild type (see Fig. S4B). These results are in agreement with the essential role of RamA for adhA expression.

To determine the methanol oxidation capacity of C. glutamicum under optimal conditions, i.e., in the absence of carbon catabolite repression (which in the case of adhA is seen not only with glucose but also with acetate [43]), we analyzed cells cultivated in CGXII minimal medium containing 100 mM methanol and 100 mM ethanol. Under these conditions, the specific methanol consumption rate was 366 ± 19 μmol h−1 (g CDW)−1, compared to 170 ± 60 μmol h−1 (g CDW)−1 in medium containing 100 mM methanol and 28 mM glucose.

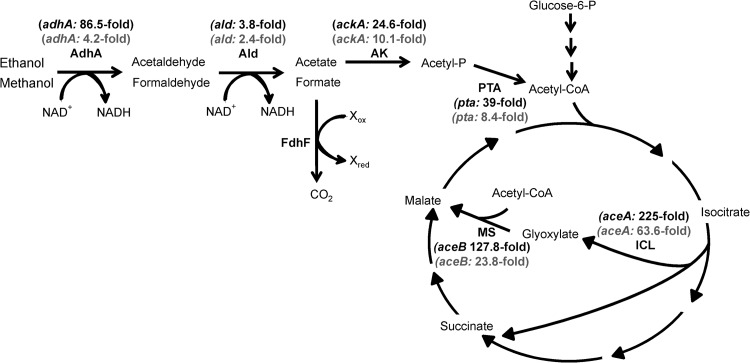

The DNA microarray experiments reported above were performed with cells cultivated in the presence of 111 mM glucose and 100 mM methanol. To test whether methanol alone provokes a more pronounced up- or downregulation of relevant genes, another set of DNA microarray experiments was performed in which RNA was prepared from resting cells incubated with or without methanol as a sole carbon source. In this case, an about 5-fold-higher expression of genes involved in methanol, ethanol, and acetate metabolism was observed than in the previous DNA microarray experiment, confirming the negative effect of glucose on these genes (Fig. 5). The total number of genes showing altered expression in these experiments was much larger due to the usage of resting cells (see Table S3 in the supplemental material).

Fig 5.

Influence of methanol on expression of selected genes in C. glutamicum. DNA microarray experiments showed that genes participating in ethanol catabolism and methanol oxidation are upregulated in the presence of methanol (AdhA, alcohol dehydrogenase; Ald, acetaldehyde dehydrogenase; AK, acetate kinase; PTA, phosphotransacetylase; MS, malate synthase; ICL, isocitrate lyase). The influence of methanol was more pronounced when methanol was added to resting cells in the absence of glucose (black numbering) than after the addition of methanol to cells grown with glucose (gray numbers).

DISCUSSION

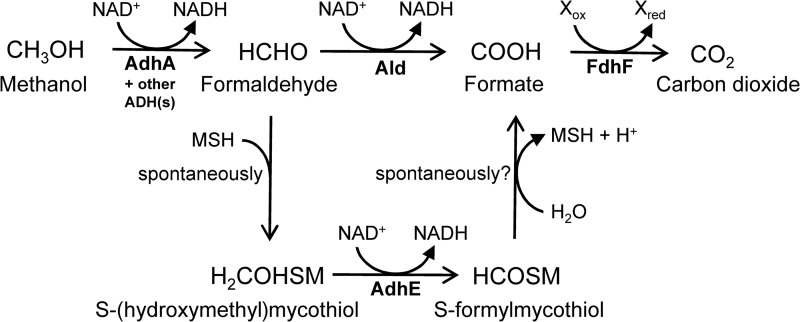

In this study, the capability of C. glutamicum for oxidation of methanol to CO2 was demonstrated for the first time, and the key enzymes involved in this endogenous pathway were identified (Fig. 6). The dissimilation of C1 compounds is widespread in nature and has also been found in other members of the Actinomycetales, such as Amycolatopsis methanolica, R. erythropolis, or M. smegmatis (59–61).

Fig 6.

Overview of the methanol oxidation pathway in C. glutamicum. Methanol is oxidized to formaldehyde by the alcohol dehydrogenase AdhA and at least one additional unknown dehydrogenase. Formaldehyde is then either directly oxidized to formate by the acetaldehyde dehydrogenase Ald or spontaneously forms S-(hydroxymethyl)mycothiol with mycothiol (MSH). Subsequently, AdhE oxidizes S-(hydroxymethyl)mycothiol to S-formylmycothiol, which hydrolyzes to mycothiol and formate. Finally, formate is oxidized to carbon dioxide by the formate dehydrogenase FdhF, which is dependent on a yet-unknown redox cofactor.

Our results revealed that the NAD+- and zinc-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase AdhA is primarily responsible for methanol oxidation. This is in line with the finding that AdhA of C. glutamicum strain R, which has 98% sequence identity to AdhA of strain ATCC 13032, is active not only with ethanol but also with methanol, propanol, and butanol (11). Besides AdhA, one or more additional dehydrogenase(s) capable of oxidizing methanol must be present in C. glutamicum. In contrast to the ΔadhA strain, the ΔadhC, ΔadhE, Δcg2714, and Δcg0273 deletion mutants did not show a reduction of the methanol oxidation rate, arguing against an important role of the encoded putative alcohol dehydrogenases in methanol catabolism.

The oxidation of formaldehyde by C. glutamicum was shown to be predominantly catalyzed by the enzymes Ald (Cg3096) and AdhE (Cg0387). Similar to AdhA, Ald is essential for growth on ethanol, since it catalyzed the oxidation of acetaldehyde to acetate (44). Interestingly, Ald of C. glutamicum shows 70% sequence identity to an NAD+-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase (AldhR) from R. erythropolis UPV-1 (62). This enzyme is characterized by broad substrate specificity for aliphatic aldehydes, such as n-hexanal, n-octanal, and formaldehyde. Hence, it is no surprise that Ald of C. glutamicum also accepts formaldehyde as the substrate.

Sequence similarity analyses revealed that AdhE belongs to the class III zinc-dependent alcohol dehydrogenases but also exhibits high sequence identity to the MSH-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase AdhC of R. erythropolis. In this organism, AdhC oxidizes aliphatic alcohols ranging from ethanol to octanol but not methanol in an MSH-independent manner in addition to the MSH-dependent oxidation of formaldehyde (60). The mycothiol dependence of formaldehyde oxidation by AdhE of C. glutamicum was confirmed by the fact that a mycothiol-defective mutant (ΔmshC) showed the same phenotype as a ΔadhE mutant and a Δald ΔmshC double mutant behaved similarly to a Δald ΔadhE mutant. In C. glutamicum, mycothiol was reported to contribute to resistance to alkylating agents, glyphosate, ethanol, antibiotics, heavy metals, and aromatic compounds (63). Our findings indicate that C. glutamicum, similar to R. erythropolis (47), can oxidize formaldehyde in an MSH-dependent manner via AdhE and in an NAD-dependent manner via Ald.

In the case of MSH-dependent oxidation of formaldehyde, the intermediate S-formylmycothiol is formed. In M. tuberculosis, a gene (Rv2854) is found which might code for an S-formylmycothiol hydrolase (FMH). However, no thiol esterase activity converting S-formylmycothiol to formate was detected in M. tuberculosis, suggesting that S-formylmycothiol might be oxidatively converted by a molybdoprotein aldehyde dehydrogenase to an unstable carbon dioxide ester, which then spontaneously decomposes to CO2 and MSH (51). A C. glutamicum Δald mutant still accumulates the same amount of formate as the wild type, indicating that S-formylmycothiol generated by AdhE is not oxidized to CO2 but is hydrolyzed to formate and mycothiol either spontaneously or by an FMH. The genes cg0388 and cg2193 show sequence similarity to putative FMHs of R. erythropolis and M. tuberculosis. However, the Δald Δcg0388 and Δald Δcg2193 double mutants were unaltered with respect to formate accumulation, indicating that the Cg0388 and Cg2193 proteins are not required for hydrolysis of S-formyl-mycothiol and that this step may occur spontaneously.

The last step in the methanol oxidation pathway, the oxidation of formate to CO2, was shown to be catalyzed by the previously identified molybdenum cofactor-dependent formate dehydrogenase FdhF (25). The electron acceptor of this enzyme has not yet been identified.

During this study, we observed that methanol oxidation in C. glutamicum is subject to catabolite repression by glucose. Repression of adhA and ald expression by glucose has been described first for studies of ethanol catabolism in C. glutamicum (44). Expression of both genes is strictly dependent on the transcriptional regulator RamA, since a ramA-deficient strain was no longer able to grow on ethanol as a carbon source (26, 44, 54, 56). Our DNA microarray experiments confirmed the upregulation of adhA and ald in the presence of methanol, and enzyme assays with cell extracts revealed that the NAD-dependent ethanol dehydrogenase activity of cells cultivated in minimal medium with glucose and methanol was 3-fold higher than that in cells grown solely with glucose. Thus, not only ethanol but also methanol apparently is capable of triggering transcription of RamA-activated genes. The deletion mutant C. glutamicum ΔramA was strongly impaired in its ability to oxidize methanol, in line with the fact that RamA is essential for transcriptional activation of adhA and ald. Until now, it has not been clear how RamA activity is controlled at the protein level. Our results clearly indicate that not only C2 metabolites but also C1 metabolites are capable of activating RamA.

In summary, we identified four enzymes (AdhA, Ald, AdhE, and Fdh) and one transcriptional regulator (RamA) that are involved in the endogenous oxidation of methanol to CO2 by C. glutamicum. As indicated in the introduction, methanol could be an interesting carbon source for the microbial production of food and feed additives or fine chemicals (23). To date, only a few methylotrophic bacteria, such as Bacillus methanolicus or Methylophilus methylotrophus, were engineered for the production of amino acids from methanol (64, 65). As an alternative approach, it might be possible to establish the ability to utilize methanol as a carbon source in naturally nonmethylotrophic C. glutamicum production strains by introducing suitable heterologous pathways, such as the ribulose monophosphate pathway or the serine pathway. The elucidation of the route for methanol dissimilation to carbon dioxide and its regulation achieved in this study represents a first step toward this goal.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Sabrina Witthoff is an associate fellow of the CLIB-Graduate Cluster Industrial Biotechnology.

We thank Bernhard Eikmanns (University of Ulm) for providing C. glutamicum strain RG2, Jörn Kalinowski (University of Bielefeld) for providing the C. glutamicum ΔmshC strain and plasmid pK18mobsacBΔncgl1457, and Steffen Ostermann (Forschungszentrum Jülich) for assistance during the 13C labeling experiments.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 6 September 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02705-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chistoserdova L, Kalyuzhnaya MG, Lidstrom ME. 2009. The expanding world of methylotrophic metabolism. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63:477–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chistoserdova L. 2011. Modularity of methylotrophy, revisited. Environ. Microbiol. 13:2603–2622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goswami P, Chinnadayyala SS, Chakraborty M, Kumar AK, Kakoti A. 2013. An overview on alcohol oxidases and their potential applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97:4259–4275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakagawa T, Mitsui R, Tani A, Sasa K, Tashiro S, Iwama T, Hayakawa T, Kawai K. 2012. A catalytic role of XoxF1 as La3+-dependent methanol dehydrogenase in Methylobacterium extorquens strain AM1. PLoS One 7:e50480. 10.1371/journal.pone.0050480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arfman N, Watling EM, Clement W, van Oosterwijk RJ, de Vries GE, Harder W, Attwood MM, Dijkhuizen L. 1989. Methanol metabolism in thermotolerant methylotrophic Bacillus strains involving a novel catabolic NAD-dependent methanol dehydrogenase as a key enzyme. Arch. Microbiol. 152:280–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen NH, Counago RM, Djoko KY, Jennings MP, Apicella MA, Kobe B, McEwan AG. 2013. A glutathione-dependent detoxification system is required for formaldehyde resistance and optimal survival of Neisseria meningitidis in biofilms. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18:743–755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolt HM. 1987. Experimental toxicology of formaldehyde. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 113:305–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heck HD, Casanova M, Starr TB. 1990. Formaldehyde toxicity—new understanding. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 20:397–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vorholt JA. 2002. Cofactor-dependent pathways of formaldehyde oxidation in methylotrophic bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 178:239–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yurimoto H, Kato N, Sakai Y. 2005. Assimilation, dissimilation, and detoxification of formaldehyde, a central metabolic intermediate of methylotrophic metabolism. Chem. Rec. 5:367–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotrbova-Kozak A, Kotrba P, Inui M, Sajdok J, Yukawa H. 2007. Transcriptionally regulated adhA gene encodes alcohol dehydrogenase required for ethanol and n-propanol utilization in Corynebacterium glutamicum R. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 76:1347–1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becker J, Wittmann C. 2012. Bio-based production of chemicals, materials and fuels—Corynebacterium glutamicum as versatile cell factory. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 23:631–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okino S, Noburyu R, Suda M, Jojima T, Inui M, Yukawa H. 2008. An efficient succinic acid production process in a metabolically engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum strain. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 81:459–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Litsanov B, Brocker M, Bott M. 2012. Toward homosuccinate fermentation: metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for anaerobic production of succinate from glucose and formate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:3325–3337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wieschalka S, Blombach B, Bott M, Eikmanns BJ. 2013. Bio-based production of organic acids with Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microb. Biotechnol. 6:87–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider J, Wendisch VF. 2011. Biotechnological production of polyamines by bacteria: recent achievements and future perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 91:17–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mimitsuka T, Sawai H, Hatsu M, Yamada K. 2007. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for cadaverine fermentation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71:2130–2135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kind S, Wittmann C. 2011. Bio-based production of the platform chemical 1,5-diaminopentane. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 91:1287–1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inui M, Kawaguchi H, Murakami S, Vertes AA, Yukawa H. 2004. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for fuel ethanol production under oxygen-deprivation conditions. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 8:243–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith KM, Cho KM, Liao JC. 2010. Engineering Corynebacterium glutamicum for isobutanol production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 87:1045–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blombach B, Riester T, Wieschalka S, Ziert C, Youn JW, Wendisch VF, Eikmanns BJ. 2011. Corynebacterium glutamicum tailored for efficient isobutanol production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:3300–3310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheele S, Oertel D, Bongaerts J, Evers S, Hellmuth H, Maurer KH, Bott M, Freudl R. 2013. Secretory production of an FAD cofactor-containing cytosolic enzyme (sorbitol-xylitol oxidase from Streptomyces coelicolor) using the twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microb. Biotechnol. 6:202–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schrader J, Schilling M, Holtmann D, Sell D, Filho MV, Marx A, Vorholt JA. 2009. Methanol-based industrial biotechnology: current status and future perspectives of methylotrophic bacteria. Trends Biotechnol. 27:107–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abe S, Takayama K, Kinoshita S. 1967. Taxonomical studies on glutamic acid producing bacteria. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 13:279–301 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Witthoff S, Eggeling L, Bott M, Polen T. 2012. Corynebacterium glutamicum harbours a molybdenum cofactor-dependent formate dehydrogenase which alleviates growth inhibition in the presence of formate. Microbiology 158:2428–2439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cramer A, Gerstmeir R, Schaffer S, Bott M, Eikmanns BJ. 2006. Identification of RamA, a novel LuxR-type transcriptional regulator of genes involved in acetate metabolism of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 188:2554–2567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng J, Che Y, Milse J, Yin YJ, Liu L, Ruckert C, Shen XH, Qi SW, Kalinowski J, Liu SJ. 2006. The gene ncgl2918 encodes a novel maleylpyruvate isomerase that needs mycothiol as cofactor and links mycothiol biosynthesis and gentisate assimilation in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Biol. Chem. 281:10778–10785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schäfer A, Tauch A, Jäger Kalinowski WJ, Thierbach G, Pühler A. 1994. Small mobilizable multipurpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19—selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frunzke J, Engels V, Hasenbein S, Gätgens C, Bott M. 2008. Co-ordinated regulation of gluconate catabolism and glucose uptake in Corynebacterium glutamicum by two functionally equivalent transcriptional regulators, GntR1 and GntR2. Mol. Microbiol. 67:305–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Russell D. 2001. Molecular cloning. A laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niebisch A, Bott M. 2001. Molecular analysis of the cytochrome bc1-aa3 branch of the Corynebacterium glutamicum respiratory chain containing an unusual diheme cytochrome c1. Arch. Microbiol. 175:282–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eikmanns BJ, Thum-Schmitz N, Eggeling L, Lüdtke KU, Sahm H. 1994. Nucleotide sequence, expression and transcriptional analysis of the Corynebacterium glutamicum gltA gene encoding citrate synthase. Microbiology 140:1817–1828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanahan D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Rest ME, Lange C, Molenaar D. 1999. A heat shock following electroporation induces highly efficient transformation of Corynebacterium glutamicum with xenogeneic plasmid DNA. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 52:541–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koch-Koerfges A, Kabus A, Ochrombel I, Marin K, Bott M. 2012. Physiology and global gene expression of a Corynebacterium glutamicum DF1FO-ATP synthase mutant devoid of oxidative phosphorylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817:370–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nash T. 1953. The colorimetric estimation of formaldehyde by means of the Hantzsch reaction. Biochem. J. 55:416–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Möker N, Brocker M, Schaffer S, Krämer R, Morbach S, Bott M. 2004. Deletion of the genes encoding the MtrA-MtrB two-component system of Corynebacterium glutamicum has a strong influence on cell morphology, antibiotics susceptibility and expression of genes involved in osmoprotection. Mol. Microbiol. 54:420–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brand S, Niehaus K, Pühler A, Kalinowski J. 2003. Identification and functional analysis of six mycolyltransferase genes of Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032: the genes cop1, cmt1, and cmt2 can replace each other in the synthesis of trehalose dicorynomycolate, a component of the mycolic acid layer of the cell envelope. Arch. Microbiol. 180:33–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wendisch VF. 2003. Genome-wide expression analysis in Corynebacterium glutamicum using DNA microarrays. J. Biotechnol. 104:273–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalinowski J, Bathe B, Bartels D, Bischoff N, Bott M, Burkovski A, Dusch N, Eggeling L, Eikmanns BJ, Gaigalat L, Goesmann A, Hartmann M, Huthmacher K, Krämer R, Linke B, McHardy AC, Meyer F, Möckel B, Pfefferle W, Pühler A, Rey DA, Rückert C, Rupp O, Sahm H, Wendisch VF, Wiegrabe I, Tauch A. 2003. The complete Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 genome sequence and its impact on the production of L-aspartate-derived amino acids and vitamins. J. Biotechnol. 104:5–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ikeda M, Nakagawa S. 2003. The Corynebacterium glutamicum genome: features and impacts on biotechnological processes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 62:99–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arndt A, Eikmanns BJ. 2007. The alcohol dehydrogenase gene adhA in Corynebacterium glutamicum is subject to carbon catabolite repression. J. Bacteriol. 189:7408–7416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Auchter M, Arndt A, Eikmanns BJ. 2009. Dual transcriptional control of the acetaldehyde dehydrogenase gene ald of Corynebacterium glutamicum by RamA and RamB. J. Biotechnol. 140:84–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Norin A, Van Ophem PW, Piersma SR, Persson B, Duine JA, Jornvall H. 1997. Mycothiol-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase, a prokaryotic medium-chain dehydrogenase/reductase, phylogenetically links different eukaroytic alcohol dehydrogenases—primary structure, conformational modelling and functional correlations. Eur. J. Biochem. 248:282–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vogt RN, Steenkamp DJ, Zheng R, Blanchard JS. 2003. The metabolism of nitrosothiols in the mycobacteria: identification and characterization of S-nitrosomycothiol reductase. Biochem. J. 374:657–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshida N, Hayasaki T, Takagi H. 2011. Gene expression analysis of methylotrophic oxidoreductases involved in the oligotrophic growth of Rhodococcus erythropolis N9T-4. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 75:123–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newton GL, Buchmeier N, Fahey RC. 2008. Biosynthesis and functions of mycothiol, the unique protective thiol of Actinobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72:471–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rawat M, Av-Gay Y. 2007. Mycothiol-dependent proteins in actinomycetes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 31:278–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jothivasan VK, Hamilton CJ. 2008. Mycothiol: synthesis, biosynthesis and biological functions of the major low molecular weight thiol in actinomycetes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 25:1091–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duine JA. 1999. Thiols in formaldehyde dissimilation and detoxification. BioFactors 10:201–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wendisch VF, De Graaf AA, Sahm H, Eikmanns BJ. 2000. Quantitative determination of metabolic fluxes during coutilization of two carbon sources: comparative analyses with Corynebacterium glutamicum during growth on acetate and/or glucose. J. Bacteriol. 182:3088–3096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krämer R, Lambert C, Hoischen C, Ebbighausen H. 1990. Uptake of glutamate in Corynebacterium glutamicum. 1. Kinetic properties and regulation by internal pH and potassium. Eur. J. Biochem. 194:929–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arndt A, Auchter M, Ishige T, Wendisch VF, Eikmanns BJ. 2008. Ethanol catabolism in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 15:222–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Auchter M, Laslo T, Fleischer C, Schiller L, Arndt A, Gaigalat L, Kalinowski J, Eikmanns BJ. 2011. Control of adhA and sucR expression by the SucR regulator in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Biotechnol. 152:77–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gerstmeir R, Cramer A, Dangel P, Schaffer S, Eikmanns BJ. 2004. RamB, a novel transcriptional regulator of genes involved in acetate metabolism of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 186:2798–2809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Auchter M, Cramer A, Huser A, Rückert C, Emer D, Schwarz P, Arndt A, Lange C, Kalinowski J, Wendisch VF, Eikmanns BJ. 2011. RamA and RamB are global transcriptional regulators in Corynebacterium glutamicum and control genes for enzymes of the central metabolism. J. Biotechnol. 154:126–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Laslo T, von Zaluskowski P, Gabris C, Lodd E, Ruckert C, Dangel P, Kalinowski J, Auchter M, Seibold G, Eikmanns BJ. 2012. Arabitol metabolism of Corynebacterium glutamicum and its regulation by AtlR. J. Bacteriol. 194:941–955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Misset-Smits M, van Ophem PW, Sakuda S, Duine JA. 1997. Mycothiol, 1-O-(2′-[N-acetyl-L-cysteinyl]amido-2′-deoxy-alpha-D-glucopyranosyl)-D-myo-inositol, is the factor of NAD/factor-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase. FEBS Lett. 409:221–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eggeling L, Sahm H. 1985. The formaldehyde dehydrogenase of Rhodococcus erythropolis, a trimeric enzyme requiring a cofactor and active with alcohols. Eur. J. Biochem. 150:129–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Ophem PW, Van Beeumen J, Duine JA. 1992. NAD-linked, factor-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase or trimeric, zinc-containing, long-chain alcohol dehydrogenase from Amycolatopsis methanolica. Eur. J. Biochem. 206:511–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jaureguibeitia A, Saa L, Llama MJ, Serra JL. 2007. Purification, characterization and cloning of aldehyde dehydrogenase from Rhodococcus erythropolis UPV-1. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 73:1073–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu YB, Long MX, Yin YJ, Si MR, Zhang L, Lu ZQ, Wang Y, Shen XH. 2013. Physiological roles of mycothiol in detoxification and tolerance to multiple poisonous chemicals in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Arch. Microbiol. 195:419–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heggeset TM, Krog A, Balzer S, Wentzel A, Ellingsen TE, Brautaset T. 2012. Genome sequence of thermotolerant Bacillus methanolicus: features and regulation related to methylotrophy and production of L-lysine and L-glutamate from methanol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:5170–5181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gunji Y, Yasueda H. 2006. Enhancement of L-lysine production in methylotroph Methylophilus methylotrophus by introducing a mutant LysE exporter. J. Biotechnol. 127:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.