Abstract

The homeodomain transcription factor Pdx-1 has important roles in pancreatic development and β-cell function and survival. In the present study, we demonstrate that adenovirus-mediated overexpression of Pdx-1 in rat or human islets also stimulates cell replication. Moreover, cooverexpression of Pdx-1 with another homeodomain transcription factor, Nkx6.1, has an additive effect on proliferation compared to either factor alone, implying discrete activating mechanisms. Consistent with this, Nkx6.1 stimulates mainly β-cell proliferation, whereas Pdx-1 stimulates both α- and β-cell proliferation. Furthermore, cyclins D1/D2 are upregulated by Pdx-1 but not by Nkx6.1, and inhibition of cdk4 blocks Pdx-1-stimulated but not Nkx6.1-stimulated islet cell proliferation. Genes regulated by Pdx-1 but not Nkx6.1 were identified by microarray analysis. Two members of the transient receptor potential cation (TRPC) channel family, TRPC3 and TRPC6, are upregulated by Pdx-1 overexpression, and small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of TRPC3/6 or TRPC6 alone inhibits Pdx-1-induced but not Nkx6.1-induced islet cell proliferation. Pdx-1 also stimulates extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) phosphorylation, an effect partially blocked by knockdown of TRPC3/6, and blockade of ERK1/2 activation with a MEK1/2 inhibitor partially impairs Pdx-1-stimulated proliferation. These studies define a pathway by which overexpression of Pdx-1 activates islet cell proliferation that is distinct from and additive to a pathway activated by Nkx6.1.

INTRODUCTION

Type 1 diabetes mellitus is caused by autoimmune destruction of pancreatic islet β cells, whereas type 2 diabetes involves the combined loss of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) and functional β-cell mass by nonautoimmune mechanisms (1–3). Because both forms of diabetes are characterized by insulinopenia, transplantation of functional β cells or delivery of agents that induce β cells to replicate in a controlled manner have been considered as therapeutic strategies. These potential interventions require identification of pathways that maintain or augment islet proliferation with retention of function, but such strategies have remained elusive, especially when dealing with human islets (4).

In most cases, factors that induce β-cell replication also cause loss of desired phenotypes, such as insulin content and GSIS (5, 6). Rare exceptions to this include cyclin D or cdk6 overexpression, which is sufficient to promote human β-cell proliferation with no discernible loss of function (7), although recent studies suggest that these factors may also promote DNA damage and eventual cell cycle arrest (8). In addition, our laboratory has shown that Nkx6.1 overexpression is sufficient to promote proliferation while potentiating GSIS in isolated rat islets (9). It should be noted that in another study with inducible Nkx6.1 transgenic mice, an increase in islet cell proliferation was not observed (10), which may be attributed to the level of Nkx6.1 overexpression or a difference in species. It is also important to devise methods to protect islet cells against cytotoxic agents encountered in diabetes, including cytokines, elevated lipids, and toxins produced by immune responses (11, 12). Thus, factors that maintain functionality, provide protection, and stimulate proliferation are of great interest. Pdx-1 is known to regulate pancreatic islet function and protect against cell death (13–16). Therefore, the current investigation was focused on determining if Pdx-1 could be used as a tool for inducing islet cell proliferation.

Many years of research have led to an understanding of a temporal sequence of expression of a family of transcription factors that coordinate the development of α, β, and δ cells in pancreatic islets. Brn4, Pax4, Pax6, Mafa, Mafb, Nkx2.2, Nkx6.1, and Pdx-1 are among the factors that are important for late-stage differentiation of mature α, β, and δ cells (17). These factors are also important for maintaining differentiated functions of adult islet cells. Pdx-1 is essential for pancreatic development, as demonstrated by complete pancreatic agenesis in Pdx-1−/− mice (18, 19). Reduced expression of Pdx-1 leads to impaired GSIS (13), but importantly, Pdx-1 overexpression does not impair function (20). A potential concern is raised by a recent report linking Pdx-1 to malignant phenotypes in pancreatic cancers (21). In contrast, no evidence of an oncogenic phenotype was reported in pancreata of Pdx-1 transgenic mice (22). Pdx-1 is also necessary for maintenance of β-cell mass, as demonstrated by studies in β-cell-specific Pdx-1+/− mice (23). Moreover, Pdx-1 deficiency leads to increased apoptosis, autophagy, and susceptibility to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (14–16), suggesting that Pdx-1 is essential for β-cell survival. Pdx-1 expression has been associated with proliferation or increased β-cell mass in remnant islets (24) and in pancreatic ductal cells after partial (90%) pancreatectomy (25). While Pdx-1 transgenic mice have a 2-fold increase of 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling in β cells compared to wild-type mice (22), the impact of acute expression of Pdx-1 on proliferation in isolated islets has not been studied, and the mechanisms by which Pdx-1 might induce proliferation are unknown.

In the present study, we show that Pdx-1 overexpression stimulates rat islet cell proliferation as measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation, and phospho-histone H3 (pHH3) staining. We also show that Pdx-1 overexpression stimulates [3H]thymidine incorporation in human islets. Moreover, we demonstrate that the cooverexpression of Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 results in an additive proliferative effect and that the two factors activate islet proliferation via two separate pathways. We show that unlike Nkx6.1, which stimulates mainly β-cell proliferation, Pdx-1 stimulates both α- and β-cell proliferation. We also demonstrate that the cyclin D-cdk4 complex is essential for Pdx-1-stimulated but not Nkx6.1-stimulated proliferation. Finally, we show that the transient receptor potential cation (TRPC) channels TRPC3 and TRPC6, as well as activated extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), are required to support the proliferative effect of Pdx-1. Our findings map out a new pathway for stimulation of β-cell replication that may contain targets for expansion of functional β-cell mass in diabetes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, reagents, and use of recombinant adenoviruses.

INS-1-derived 832/13 rat insulinoma cells were cultured as previously described (26). Pancreatic islets were isolated from male Wistar rats and cultured as previously described (9, 27, 28) under a protocol approved by the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Human islets were obtained from the Integrated Islet Distribution Program (http://iidp.coh.org). The cdk4 inhibitor (PD0332991) was a kind gift from Ned Sharpless at the University of North Carolina (UNC)—Chapel Hill. Cyclosporine and the MEK1/2 inhibitor (U0126) were purchased from Calbiochem.

For gene overexpression studies, cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter-driven recombinant adenoviruses containing hamster Nkx6.1, mouse Pdx-1, bacterial β-galactosidase (β-Gal), green fluorescent protein (GFP), and constitutively active calcineurin (CnA) cDNAs were used as previously described (20, 29, 30). We constructed CMV promoter-driven human Flag-tagged TRPC3 and human Myc-tagged TRPC6 adenoviruses by cloning cDNA constructs into the pAdTrack shuttle vector and using the Ad-Easy system to generate the recombinant adenoviruses as previously described (31).

For gene suppression studies in isolated rat islets, adenoviruses containing small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) specific to rat TRPC3/TRPC6 (siT3/T6) or rat TRPC6 (siT6) or with no known gene homology (scrambled siRNA [siScr]) were constructed and used as described previously (32).

All recombinant adenoviruses were shown to be E1A deficient using a reverse transcription (RT)-PCR screen as previously described (33). Pools of 200 islets were cultured in 2 ml of RPMI medium (10% fetal calf serum [FCS] and 8 mM glucose), treated with viruses at a concentration of ∼2 × 109 particles/ml medium for 18 h, and then cultured in virus-free medium until the islets were collected for assays 78 h postransduction, unless otherwise indicated. For gene overexpression studies in 832/13 cells, cells were treated with viruses at a concentration of ∼0.2 × 109 particles/ml medium for 18 h and then cultured in virus-free medium until the cells were collected for assays 48 h postransduction.

For gene suppression studies in 832/13 cells, siRNA duplexes targeting TRPC3 and TRPC6 were purchased and used according to the manufacturer's protocol (Dharmacon) at a final concentration of 50 nM. A duplex with no known target (siScr) was used as a control (34). Before the transfection of the siRNA duplexes, 832/13 cells were first treated with an adenovirus overexpressing Pdx-1 for 4 h. The medium was then changed, and the transfection was performed 2 h later. Cells were harvested after an additional 72 h of culture.

[3H]thymidine incorporation.

DNA synthesis rates were measured as described previously (9, 35) with some modifications. Briefly, [3H]thymidine was added at a final concentration of 1 μCi/ml to pools of approximately 200 islets during the last 18 h of cell culture. Three groups of 20 islets were picked, washed once in medium, and washed once in 1× PBS. Islets were collected by centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 5 min at room temperature. DNA was precipitated by adding 500 μl of cold 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) for 20 min on ice followed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm at 4°C for 20 min. The pellet was solubilized with 80 μl of 0.3 N NaOH. The amount of [3H]thymidine incorporated into DNA was measured by liquid scintillation counting and normalized to total cellular protein (36).

EdU incorporation.

For EdU labeling, a 1:1,000 dilution of EdU-labeling reagent (Invitrogen) was added to islet culture medium during the last 18 h of cell culture. For immunohistochemistry (IHC), islets were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 h at room temperature. The islets were prepared for immunohistochemistry as previously described (35) with some modifications. After mixing the islets with Affi-Gel blue beads (Bio-Rad), warm HistoGel (Thermo Scientific) (55°C) was added to the slurry. After cooling, the histogel containing the islet-bead mixture was embedded in paraffin and sectioned. Five-micrometer sections were deparaffinized and subjected to antigen retrieval as previously described (9). EdU was detected using the Click-iT kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. For insulin and glucagon staining, slides were incubated overnight with goat anti-guinea pig insulin (Dako; catalog number A0564) and goat anti-rabbit glucagon (Dako; catalog number A0565) antibodies followed by detection with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig secondary antibody and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody, respectively (Invitrogen; catalog numbers A11073 and A21245, respectively). The slides were counterstained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). Images were captured and analyzed using OpenLab software, and cells were quantitated using ImageJ software.

For immunofluorescence, islets were dispersed using trypsin-EDTA, plated on poly-d-lysine-coated coverslips (BD Biosciences), and fixed using neutral buffered formalin. EdU detection, insulin staining, pHH3 (Cell Signaling; catalog number 2577) staining, and phospho-γH2AX (γH2AX) (Cell Signaling; catalog number 3377) staining were performed as described above for IHC. Cells were counterstained with DAPI. Images were captured and analyzed using OpenLab software, and cells were quantitated using ImageJ software.

Microarray analysis.

Rat islets were left untreated (no virus [NV]) or treated for 18 h with recombinant adenovirus (β-Gal or Pdx-1) and cultured for an additional 30 h. Islets were harvested 48 h postransduction, and total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). cDNA microarray analysis was performed on the Rat Genome 230 2.0 array (Affymetrix) with 31,042 probe sets corresponding to over 28,000 annotated genes in the Duke University Microarray Core Facility. Replicate (n = 5) microarray studies were performed for each treatment. Analysis of gene expression data was conducted with modules from GenePattern (http://genepattern.broadinstitute.org). An expression matrix was generated from the raw Affymetrix data using the robust multiarray average (RMA) algorithm in the ExpressionFileCreator module. The raw intensity values were background corrected, log2 transformed, and then quantile normalized. A linear model was next fitted to the normalized data to obtain an expression measure for each probe set on each array. The data set was filtered using the PreprocessDataset module to set thresholds and eliminate genes exhibiting minimal changes. Differential expression between the experimental and control conditions was determined using the ComparativeMarkerSelection module. Testing was done by a two-sided t test with cutoffs determined by false discovery rate (FDR) by the Benjamini and Hochberg procedure with P values of less than 0.05. Gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed using DAVID v6.7.

Electrophysiology.

Currents were recorded in the whole-cell voltage clamp mode using a MultiClamp-700A amplifier with the Digidata 1322A interface and analyzed with pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments) as described previously (37). The patch pipettes had a resistance of 2 to 3 MΩ when filled with a pipette solution containing 140 mM Cs aspartate, 5 mM NaCl, 1 mM Mg-ATP, 10 mM HEPES, and 10 mM BAPTA [1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid] (pH 7.3). The external solution contained 140 mM NaCl, 2.8 mM KCl, 2 mM BaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 5 mM glucose (pH 7.4). Currents were induced by a 200-ms voltage ramp protocol (1 mV/ms; from 100 to −100 mV) every 3 s from a holding potential of 0 mV (K+ channel blocked by Cs in the internal solution, L-type Ca2+ channel blocked by 10 μM verapamil in the external solution, voltage-dependent Na+ channel inactivated by the stimulation protocol, and chloride current inhibited by reduced and equal Cl− concentrations in the external and internal solutions or by 1 mM anthracene-9-carboxylic acid [9-AC] in the external solution). Experiments were performed at room temperature (20 to 22°C), with a sample rate of 4 kHz (filtered at 2 kHz). Currents were measured at −80 and +80 mV, and the currents were normalized by membrane capacitance.

Measurement of RNA levels.

RNA was isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen), and cDNA was made using iScript (Bio-Rad). Real-time PCR assays were performed using the ViiA7 detection system and software (Applied Biosystems). The primers used for rat cyclins E1, E2, D1, D2, and D3 as well as rat cdk4 were TaqMan-based Assays on Demand (Applied Biosystems). All other primers were designed and used with SYBR green (Bio-Rad). Primer sequences are available upon request.

Immunoblot analysis.

Cells or islets were harvested and lysed in ice-cold RIPA buffer (Sigma) containing protease (BD Biosciences) and phosphatase (Sigma) inhibitors. Lysates were precleared by centrifugation (13,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min), resolved on 4 to 12% NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen), and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween (TBS-T) for 30 min, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with the following diluted primary antibodies: Nkx6.1 (Iowa Development Hybridoma Bank; catalog number F55A10), Pdx-1 (Abcam; catalog number 47267), γ-tubulin (Sigma; catalog number T5326), TRPC6 (Genetex; catalog number GTX113858), Myc (Abcam; catalog number 34773-100), Flag M2 peroxidase (Sigma; catalog number A8592), phospho-p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (Cell Signaling, catalog number 4370, and Millipore, catalog number 05-797R clone AW39R), and p42/44 MAPK (Cell Signaling; catalog number 4695). Sheep anti-mouse (1:10,000) and goat anti-rabbit (1:10,000) antibodies (GE Healthcare; catalog numbers NXA931 and NA934V, respectively) coupled to horseradish peroxidase were used to detect primary antibodies, followed by detection with SuperSignal West Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific). Goat anti-mouse IRDye 800CW (1:10,000) and Alexa Fluor 680–goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000) antibodies were also used to detect primary antibodies, followed by detection using the Odyssey CLx system (Li-Cor). Quantitation of immunoblots was performed by measuring pixel density using Adobe Photoshop CS4.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± standard errors of the mean (SEM). For statistical significance determinations, data were analyzed by the two-tailed t test. For multiple group comparisons, analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Bonferroni posttest or Tukey's test was used. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Microarray data accession number.

The data files have been deposited in the NCBI GEO database (accession no. GSE49786).

RESULTS

Pdx-1 overexpression stimulates rat and human islet cell proliferation and is additive to Nkx6.1.

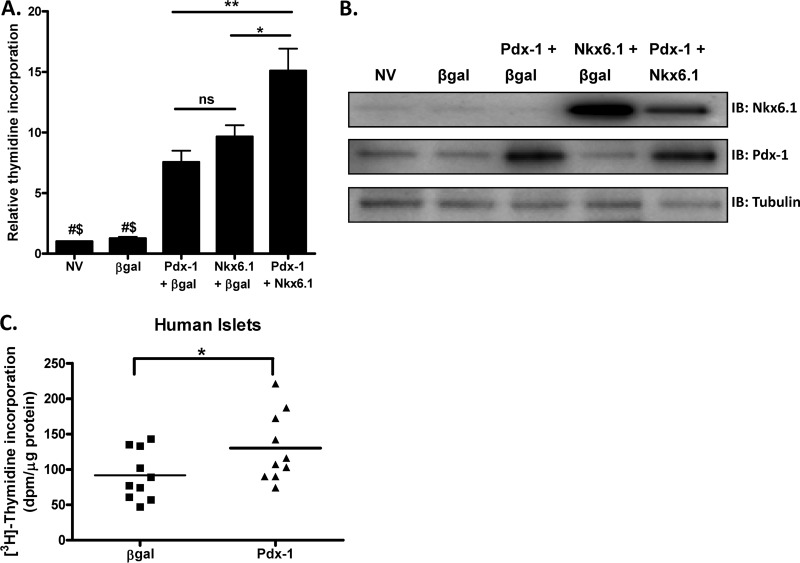

Pdx-1 is essential for pancreatic development, β-cell function, and β-cell survival (14, 18, 23), but its effects on islet cell proliferation are not well defined. Here, we tested if adenovirus-mediated overexpression of Pdx-1 is sufficient to increase proliferation, either alone or combined with overexpression of Nkx6.1, a transcription factor that we have previously reported to stimulate proliferation in isolated rat islets while enhancing GSIS (9, 20). Pdx-1 overexpression stimulated [3H]thymidine incorporation in rat islets by approximately 7- and 6-fold compared to control islets treated with NV or with a β-Gal-expressing adenovirus, respectively (Fig. 1A). Importantly, our previous work has shown that overexpression of Pdx-1 does not interfere with GSIS in rat islets (20). When Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 were cooverexpressed, an additive proliferative effect was observed (15-fold increase) compared to the effect of either transcription factor alone (8- and 10-fold increase with Pdx-1 or Nkx6.1 expression, respectively) (Fig. 1A). Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 protein levels for these experiments are shown in Fig. 1B. These data demonstrate that Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 can independently stimulate rat islet proliferation and that the combination of both factors has an additive proliferative effect.

Fig 1.

Effects of overexpressed Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 on rat islet cell proliferation and effect of Pdx-1 on human islet cell proliferation. Primary rat islets were left untreated or treated with recombinant adenoviruses (AdCMV) expressing β-Gal, Pdx-1 plus β-Gal, Nkx6.1 plus β-Gal, or Pdx-1 plus Nkx6.1, as indicated, for 18 h and cultured for an additional 78 h. (A) [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured. The data represent the means and SEM of five independent experiments. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001; ns, not significant; #, P < 0.01 versus Pdx-1; $, P < 0.001 versus Nkx6.1 and Pdx-1 plus Nkx6.1 (n = 5). (B) Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 protein expression levels as measured by immunoblot (IB) analysis. The immunoblot is representative of five independent experiments. (C) Human islets from 10 separate donors were treated with adenoviruses expressing either β-Gal or Pdx-1 for 18 h and cultured for an additional 78 h, and [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured. The data represent the means ± SEM of 10 independent experiments. *, P < 0.01 according to a paired t test.

We also studied the effect of Pdx-1 overexpression in human islets and found a significant enhancement (approximately 50%) of [3H]thymidine incorporation compared to the β-Gal control in experiments involving 10 separate islet donors (Fig. 1C). The modest proliferative effect in human islets relative to that observed in rat islets is similar to what we have reported for Nkx6.1 (8) and is consistent with the generally refractory nature of human islets to proliferative stimuli.

Pdx-1 induces proliferation of both α and β cells, whereas Nkx6.1 induces mainly β-cell proliferation.

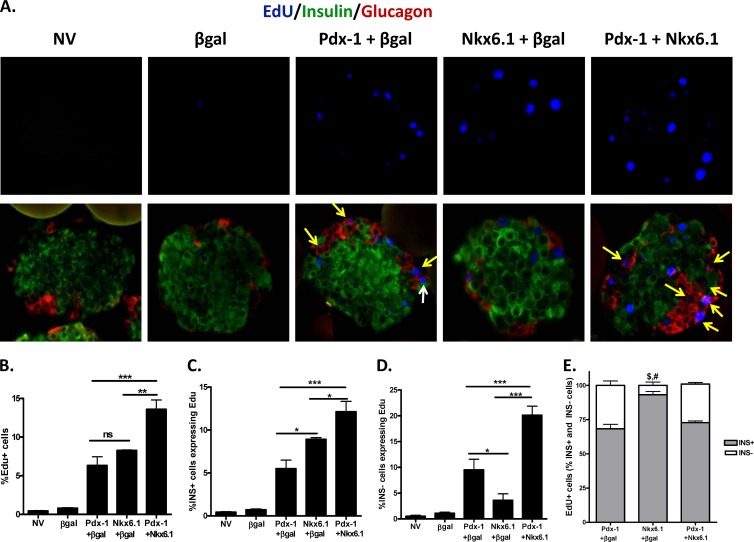

In both our prior study (9) and the current study, the adenoviruses utilized to overexpress Nkx6.1 or Pdx-1 use the CMV promoter, which is active in all mammalian cells, to drive gene expression. To identify the islet cell types that proliferate in response to overexpression of each transcription factor, islets were transduced with AdCMV–Pdx-1, AdCMV-Nkx6.1, or both adenoviruses (Pdx-1 plus Nkx6.1). Sections of paraffin-embedded rat islets from four independent experiments were treated with antibodies and were imaged by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2A). Among the four experiments, a total of 62,833 cells were counted, with at least 7,900 cells counted for each treatment. The percentages of EdU-positive cells among all islet cells were 6.3, 8.3, and 13.6% with overexpression of Pdx-1, Nkx6.1, or Pdx-1 plus Nkx6.1, respectively, relative to NV and β-Gal controls in which <1% of islet cells were EdU positive (Fig. 2B). Importantly, the additive effect of Nkx6.1 plus Pdx-1 on EdU incorporation (Fig. 2B) is in full agreement with the [3H]thymidine incorporation data (Fig. 1A). When considering cell type specificity, a significant increase in β-cell proliferation was observed when the two factors were coexpressed (12.1% ± 1.2% INS+ EdU+ cells) relative to either transcription factor alone (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, Pdx-1 caused a much larger increase in EdU incorporation into non-β cells (mainly α cells) than Nkx6.1 (9.5% versus 3.6% INS− EdU+ cells, respectively; P < 0.05) (Fig. 2D). Conversely, Nkx6.1 caused a significant increase in EdU incorporation into insulin-positive cells (β cells) relative to Pdx-1 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2C). In agreement with our previous work (9), Nkx6.1 stimulated mainly β-cell proliferation (approximately 93% of EdU+ cells were insulin positive), whereas Pdx-1 stimulated replication of both α and β cells (approximately 68 and 31% of EdU+ cells were insulin or glucagon positive, respectively) (Fig. 2E). Cooverexpression of Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 created a pattern of EdU incorporation resembling that observed with Pdx-1 overexpression. Taken together, these data show that the impact of combined overexpression of Nkx6.1 plus Pdx-1 on [3H]thymidine incorporation (Fig. 1A) is due to increased β-cell proliferation induced by both factors as well as additional α-cell proliferation that is mainly driven by Pdx-1.

Fig 2.

Pdx-1 stimulates proliferation of both α and β cells, whereas Nkx6.1 stimulates mainly β-cell proliferation. Primary rat islets were left untreated or treated with recombinant adenoviruses (AdCMV) expressing β-Gal, Pdx-1 plus β-Gal, Nkx6.1 plus β-Gal, or Pdx-1 plus Nkx6.1, as indicated, for 18 h and cultured for an additional 78 h. Islets were collected, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and used for histochemical analysis. (A) EdU was detected using the Click-iT kit (top row), and antibodies that detect insulin and glucagon were used to stain the sections (overlay of EdU, insulin, and glucagon) (bottom row). The yellow arrows indicate glucagon-positive cells (α cells) with EdU incorporation, and the white arrow indicates insulin- and glucagon-negative cells with EdU incorporation. All other Edu+ cells shown are insulin-positive cells (β cells). (B to D) Percentages of total cells expressing EdU (B), insulin-positive cells (β cells) expressing EdU (C), and insulin-negative cells (mainly α cells) expressing EdU (D). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ns, not significant (n = 4). (E) Comparison of insulin-positive (INS+) and insulin-negative (INS−) EdU+ cells (percent). #, P < 0.001 versus Pdx-1 and Pdx-1 plus Nkx6.1 for INS+ cells; $, P < 0.001 versus Pdx-1 and Pdx-1 plus Nkx6.1 for INS− cells. The data represent the means and SEM of four independent experiments.

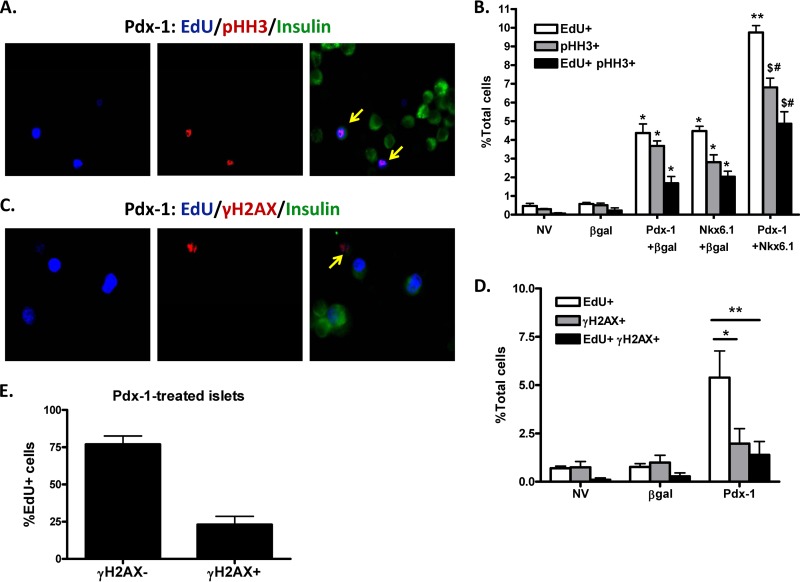

Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 increase pHH3, and Pdx-1 does not significantly increase the DNA damage marker phospho-γH2AX in rat islets.

EdU incorporation is a marker for DNA replication, an early step in cell division. To determine the extent to which cells also completed DNA synthesis and moved past the G2 checkpoint to undergo mitosis, we used pHH3 as a marker. The total number of cells positive for pHH3 was less than the number of EdU-positive cells under all conditions (Fig. 3A and B), which can be attributed to the transient phosphorylation of HH3 during the cell cycle. Nevertheless, there were approximately 7-, 9-, and 21-fold more double-positive (EdU+ pHH3+) cells in the AdCMV–Pdx-1-, AdCMV-Nkx6.1-, and ACMV–Pdx-1 plus AdCMV-Nkx6.1-treated islets, respectively, than among AdCMV–β-Gal-treated islets. Moreover, coexpression of Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 increased the number of double-positive cells relative to either factor alone (Fig. 3B). These data demonstrate that Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 induce both early and late events in the cell cycle.

Fig 3.

Both Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 promote increased pHH3 staining, but Pdx-1 does not significantly increase γH2AX staining. (A and B) Primary rat islets were left untreated or treated with recombinant adenoviruses (AdCMV) expressing β-Gal, Pdx-1 plus β-Gal, Nkx6.1 plus β-Gal, or Pdx-1 plus Nkx6.1, as indicated, for 18 h and cultured for an additional 78 h. (A) EdU was detected using the Click-iT kit, and antibodies that detect insulin and pHH3 were used for staining (overlay of EdU, pHH3, and insulin [right]). The arrows indicate double-positive cells (EdU+ pHH3+). (B) Percentages of total EdU+, pHH3+, and EdU+ pHH3+ cells were calculated. The data represent the means and SEM of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.001 versus NV and β-Gal; **, P < 0.001 versus Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1; $, P < 0.001 versus Nkx6.1; #, P < 0.01 versus Pdx-1 (n = 3). (C to E) Primary rat islets were left untreated or treated with recombinant adenoviruses expressing β-Gal or Pdx-1, as indicated, for 18 h and cultured for an additional 78 h. (C) EdU was detected using the Click-iT kit, and antibodies that detect insulin and γH2AX were used for staining (overlay of EdU, γH2AX, and insulin [right]). The arrow indicates double-positive cells (EdU+ γH2AX+). (D) Percentages of total EdU+, γH2AX+, and EdU+ γH2AX+ cells were calculated. *, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.001. (E) Percentage of γH2AX staining of EdU+ cells in Pdx-1-treated islets. The data represent the means and SEM of three independent experiments.

Recent studies involving overexpression of other proliferative factors, such as HNF4α, cdk6, and cyclin D3, in human islets have demonstrated clear increases in early proliferative markers but have also reported that the same factors induce markers of DNA damage and eventual cell cycle arrest (8). To investigate this important issue, we used γH2AX as a marker for DNA damage response (Fig. 3C). Control cells (NV or β-Gal) had <1% EdU incorporation and also were <1% positive for γH2AX staining, with only rare EdU+ γH2AX+ cells (Fig. 3D). Although the percentage of γH2AX+ cells in Pdx-1-treated islets was slightly increased (1.97% ± 0.77%) compared to β-Gal-treated islets (0.99% ± 0.38%; P > 0.05), the percentage of Edu+ cells was far greater than the percentage of cells that were γH2AX+ or EdU+ γH2AX+ (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 3D). Importantly, considering only the EdU+ cells in islets treated with the Pdx-1 adenovirus, approximately 75% of the EdU+ cells were negative for γH2AX staining, suggesting that the majority of cells induced to proliferate by Pdx-1 lack a DNA damage response (Fig. 3E).

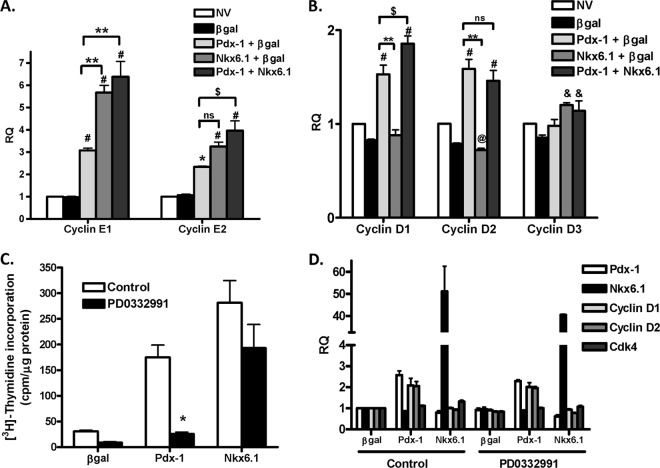

The cyclin D-cdk4 complex is necessary for Pdx-1-stimulated but not Nkx6.1-stimulated proliferation.

We next measured the mRNA levels of cyclins E1, E2, D1, D2, and D3 to understand their regulation by Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1. Pdx-1, Nkx6.1, and Pdx-1 plus Nkx6.1 increased the mRNA levels of both cyclins E1 and E2 compared to controls (Fig. 4A). In contrast, increases in cyclin D1 and D2 mRNAs occurred only in response to Pdx-1 (alone or in combination with Nkx6.1) (Fig. 4B). Thus, these data suggest that Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 exert their effects on proliferation via different components of the core cell cycle machinery.

Fig 4.

Pdx-1 but not Nkx6.1 increases cyclin D1/D2 levels and requires the cyclin D-cdk4 complex to stimulate rat islet proliferation. Primary rat islets were left untreated or treated with recombinant adenoviruses (AdCMV) expressing β-Gal, Pdx-1 plus β-Gal, Nkx6.1 plus β-Gal, or Pdx-1 plus Nkx6.1, as indicated, for 18 h and cultured for an additional 78 h. (A and B) Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to measure mRNA levels of cyclins E1, E2, D1, D2, and D3 (RQ, relative quantity). The data represent the means and SEM of five independent experiments. #, P < 0.001, and *, P < 0.01 compared to NV or β-Gal; @, P < 0.05 compared to NV; &, P < 0.01 compared to β-Gal; $, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001; ns, not significant (n = 5). (C and D) Primary rat islets were treated with recombinant adenoviruses (AdCMV) expressing β-Gal, Pdx-1, or Nkx6.1, as indicated, for 18 h and cultured for an additional 78 h. During the last 48 h of culture, vehicle or 300 nM PD0332991 (a specific cdk4 inhibitor) was added to the culture media. (C) [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured. (D) qRT-PCR was used to measure mRNA levels of Pdx-1, Nkx6.1, cyclin D1, cyclin D2, and cdk4. The data represent the means and SEM of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.01 versus control (n = 3).

To further test if cyclins D1 and D2 are necessary for Pdx-1- or Nkx6.1-stimulated rat islet proliferation, we tested the effect of disrupting the cyclin D-cdk4 complex with the cdk4-specific inhibitor, PD0332991. The inhibitor completely blocked Pdx-1-stimulated rat islet proliferation but did not significantly affect Nkx6.1-stimulated rat islet proliferation (Fig. 4C). Importantly, the cdk4 inhibitor did not affect the mRNA levels of Pdx-1, Nkx6.1, cyclin D1, cyclin D2, or cdk4 (Fig. 4D). Together, these data show that Pdx-1 but not Nkx6.1 stimulates islet cell proliferation via activation of the cyclin D-cdk4 complex.

Pdx-1 stimulates rat islet proliferation and upregulates TRPC3/6 expression 48 h after adenoviral transduction.

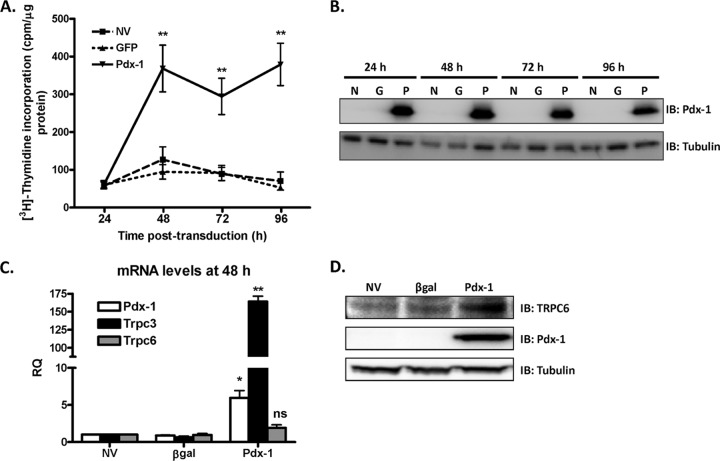

We next studied the time course of Pdx-1-mediated islet cell proliferation. Pdx-1 stimulates rat islet proliferation as early as 48 h and maintains proliferation through 96 h postransduction (Fig. 5A) while maintaining constant Pdx-1 protein levels (Fig. 5B). This experiment demonstrates another important difference between Pdx-1- and Nkx6.1-stimulated proliferation, as Nkx6.1-stimulated proliferation has a slower time course, with the first detectable effects on [3H]thymidine incorporation occurring at 72 h (9).

Fig 5.

Pdx-1 stimulates rat islet proliferation and upregulates TRPC3/6 expression as early as 48 h postransduction. (A) Time course of [3H]thymidine incorporation into rat islets using AdCMV–Pdx-1, AdCMV-GFP, or NV control. The data represent the means ± SEM of three independent experiments. **, P < 0.001 compared to NV and GFP (n = 3). (B) Time course of Pdx-1 protein expression levels as measured by immunoblot analysis. The immunoblot is representative of three independent experiments (N, untreated; G, GFP; P, Pdx-1). (C) qRT-PCR was used to measure mRNA levels of Pdx-1, TRPC3, and TRPC6 at 48 h postransduction of AdCMV–Pdx-1, AdCMV–β-Gal, or NV control (RQ, relative quantity). The data represent the means and SEM of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001; ns, not significant compared to NV or β-Gal controls (n = 3). (D) 832/13 cells were left untreated or treated with AdCMV–β-Gal or AdCMV–Pdx-1. Cells were harvested 48 h postransduction, and TRPC6 and Pdx-1 protein levels were measured via immunoblot analysis. The immunoblot is representative of three independent experiments.

To further investigate the pathway by which Pdx-1 stimulates islet cell replication, we performed microarray analyses on untreated islets and islets treated with either β-Gal or Pdx-1 adenovirus at the 48-h time point. RNA from five independent islet samples for each of the three conditions was hybridized to the Rat Genome 230 2.0 Affymetrix microarray. Compared to the β-Gal control and considering only those genes that exhibited a 2-fold change in expression level with a P value of less than 0.05, 264 genes were upregulated by Pdx-1 and 44 genes were downregulated by Pdx-1 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). To elucidate the Pdx-1-specific effect on rat islet proliferation, we investigated only those genes induced by Pdx-1 and not by Nkx6.1 by comparing the present microarray data to data previously collected from rat islets transduced with AdCMV-Nkx6.1 for 48 h (J. Tessem, unpublished data). To further classify Pdx-1-regulated genes, the microarray data were subjected to gene ontology and pathway analysis. GO pathway analysis revealed a cluster of genes related to calcium homeostasis and signaling that was strongly induced by Pdx-1 but not Nkx6.1, including the genes for calbindin 1, calbindin 2, calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type 1D (Camk1d), cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1), and protein kinase Cβ1 (PKCβ1). Treatment of islets with overexpression adenoviruses for each of these genes or expression of constitutively active forms of Camk1d and PKCβ1 was not sufficient to increase islet cell proliferation (data not shown). Moreover, treatment of Pdx-1-transduced islets with Camk1d siRNA, CB1 siRNA, Camk1d dominant-negative (DN) or PKCβ1DN adenovirus did not affect Pdx-1-induced islet cell replication (data not shown).

In addition to the above-mentioned genes, two members of the TRPC channel family, TRPC3 and TRPC6, were significantly upregulated in rat islets overexpressing Pdx-1 but not Nkx6.1. Importantly, TRPC3 and TRPC6 have been implicated in cellular proliferation in other cellular systems (38–40). To verify the microarray data, we measured mRNA levels via real-time PCR and found that TRPC3 and TRPC6 mRNA levels were approximately 150- and 3-fold higher, respectively, in AdCMV–Pdx-1-treated islets than in control islets (Fig. 5C). Although the Pdx-1-induced increase in TRPC6 mRNA at 48 h was not statistically significant compared to control islets, the increase in TRPC6 mRNA levels induced by Pdx-1 at 96 h was significant (see Fig. 7E). Pdx-1 overexpression also induced TRPC6 protein levels at 48 h postransduction in 832/13 cells (Fig. 5D). These data demonstrate that Pdx-1 stimulates rat islet proliferation as early as 48 h and suggest that TRPC3/6 may be involved in the mechanism of Pdx-1-stimulated proliferation.

Fig 7.

TRPC3/6 are necessary but not sufficient for Pdx-1-stimulated rat islet proliferation. Primary rat islets were treated with recombinant adenoviruses (AdCMV) expressing β-Gal, Pdx-1, Flag-TRPC3, or Myc-TRPC6, as indicated, for 18 h and cultured for an additional 78 h. (A) [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured. The data represent the means and SEM of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.01 (n = 3). (B) Protein expression levels as measured by immunoblot analysis. The immunoblot is representative of three independent experiments. (C to F) Primary rat islets were treated with recombinant adenoviruses containing siScr, siT3/T6, or siT6, as indicated, for 18 h. The medium was then changed, and the islets were treated with adenoviruses (AdCMV) overexpressing β-Gal, Pdx-1, or Nkx6.1, as indicated, for 18 h and cultured for an additional 84 h. (C) [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured. The data represent the means and SEM of three independent experiments. Results are for three independent experiments using the indicated adenoviruses. *, P < 0.01, and **, P < 0.001 compared to siScr (n = 3). (D to F) qRT-PCR was used to measure mRNA levels of TRPC3 (D), TRPC6 (E), and cyclin D2 (F) (RQ, relative quantity). The data represent the means and SEM of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.01, and **, P < 0.001 compared to siScr (n = 3).

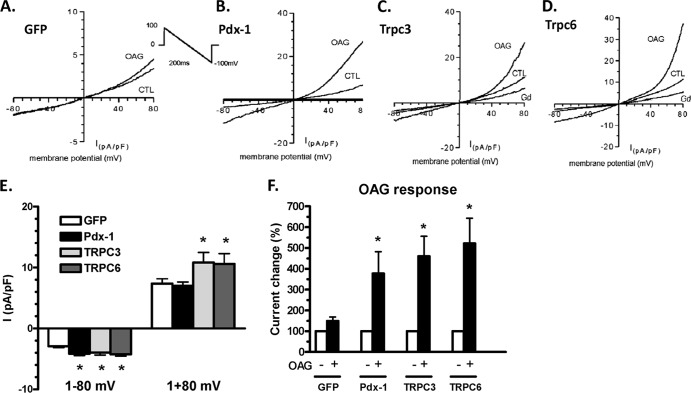

Pdx-1, TRPC3, or TRPC6 overexpression increases channel activity in 832/13 cells.

To test if Pdx-1, TRPC3, and TRPC6 regulate channel activity in β cells, as suggested by the GO analysis, we measured nonselective cation currents (INSC) by a whole-cell voltage clamp method in 832/13 rat insulinoma cells following adenovirus-mediated overexpression of Pdx-1, Flag-TRPC3, or Myc-TRPC6 (Fig. 6A to D). Currents were significantly higher in cells overexpressing Pdx-1, Flag-TRPC3, and Myc-TRPC6 than in control cells at −80 mV (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6E). As expected for TRPC channels, the current was increased after perfusion with 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG), a cell-permeable analog of diacylglycerol (DAG), and was inhibited by gadolinium (Fig. 6C and D). OAG increased INSC by 4- to 5-fold in cells overexpressing Pdx-1, Flag-TRPC3, or Myc-TRPC6 but caused only a slight increase (approximately 50%) in GFP-treated control cells (Fig. 6F). These data demonstrate that overexpressed TRPC3 and TRPC6 proteins are fully functional and that Pdx-1 induces a current consistent with increased expression of these channels.

Fig 6.

Pdx-1, TRPC3, and TRPC6 increase TRP channel activity in 832/13 cells. Membrane currents (INSC) were recorded by a whole-cell voltage clamp method in 832/13 cells with adenovirus-mediated overexpression of Pdx-1, TRPC3, or TRPC6 for 48 h. The current was induced by a 200-ms voltage ramp protocol (1 mV/ms, from 100 mV to −100 mV, and holding potential of 0 mV [A, inset]), and it was normalized by membrane capacitance I(pA/pF) represents the normalized membrane current (membrane current normalized to membrane capacitance; expressed as picoampere/picofarad). (A to D) Examples of current-voltage (I-V) relation of INSC and OAG responses recorded from individual 832/13 cells expressing GFP (A), Pdx-1 (B), TRPC3 (C), and TRPC6 (D). To verify TRP channel activity, 20 μM Gd was added to block TRP channel activity. (E) Group mean values of baseline INSC at −80 mV and +80 mV in control GFP-expressing cells (n = 20), Pdx-1-expressing cells (n = 39), TRPC3-expressing cells (n = 20), and TRPC6-expressing cells (n = 14). *, P < 0.05. (F) Group mean changes (%) of INSC at −80 mV caused by perfusion of 50 μM OAG in cells expressing GFP, Pdx-1, TRPC3, and TRPC6. *, P < 0.05.

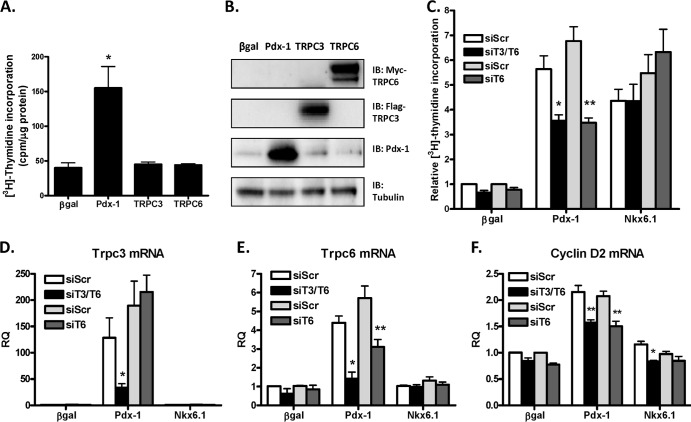

TRPC3/6 is necessary but not sufficient for Pdx-1-stimulated rat islet proliferation.

We next tested if overexpression of TRPC3 and TRPC6 was sufficient to induce rat islet proliferation. Neither Flag-TRPC3 nor Myc-TRPC6 expression stimulated rat islet proliferation compared to control islets (Fig. 7A), even with robust protein overexpression (Fig. 7B), and cooverexpression of Flag-TRPC3 and Myc-TRPC6 also had no effect (data not shown). These data demonstrate that increased expression of TRPC3 and TRPC6 is not sufficient to promote rat islet proliferation.

To test if TRPC3/6 is necessary for Pdx-1-stimulated proliferation, we treated rat islets with adenoviruses expressing an siRNA targeting a sequence common to TRPC3 and TRPC6 (siT3/T6), a separate siRNA specific for TRPC6 (siT6), or a nontargeting scrambled siRNA sequence (siScr). We then treated the same islets with adenovirus overexpressing β-Gal, Pdx-1, or Nkx6.1. Treatment with the siT3/T6 virus resulted in 75 and 70% knockdown of TRPC3 and TRPC6 mRNA levels, respectively, whereas an approximate 50% knockdown of TRPC6 mRNA levels was obtained in response to treatment with the siT6 adenovirus. Pdx-1-stimulated rat islet proliferation was inhibited by 38 and 50% in response to knockdown of TRPC3/6 and TRPC6, respectively (Fig. 7C to E). The similar impacts of the two knockdown adenoviruses are likely due to the fact that endogenous expression of TRPC6 is higher than that of TRPC3, making TRPC6 the more physiologically relevant channel. In contrast, Nkx6.1-stimulated rat islet proliferation was unaffected by knockdown of both TRPC3 and TRPC6 or TRPC6 alone (Fig. 7C). Importantly, downregulation of TRPC3/6 and TRPC6 caused a significant decrease in cyclin D2 mRNA levels (Fig. 7F). Together, these data demonstrate that TRPC3 and TRPC6 are not sufficient but are necessary for maximal Pdx-1-mediated proliferation. These results further define distinct mechanisms by which Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 regulate rat islet proliferation.

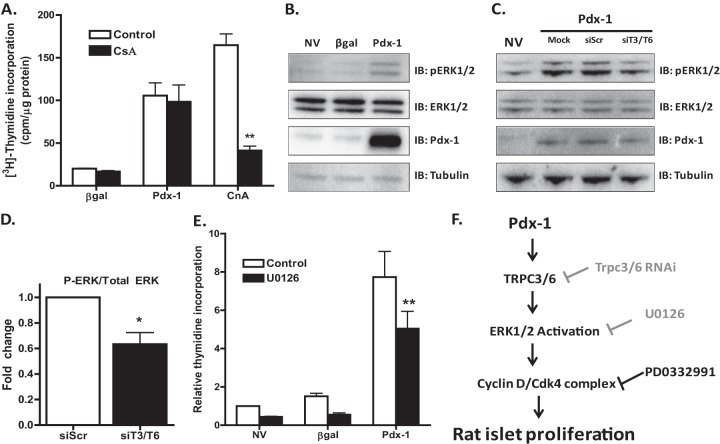

Activated ERK1/2 are downstream of TRPC3/6 and are required for maximal Pdx-1-stimulated rat islet proliferation.

Because TRPC3/6 have been shown to activate calcineurin/NFAT signaling (41), which has been implicated in β-cell proliferation, function, and survival (42, 43), we next tested if this pathway was necessary for Pdx-1-stimulated rat islet cell proliferation by blocking calcineurin activity with cyclosporine. While cyclosporine completely blocked rat islet proliferation induced by CnA overexpression, it was unable to block Pdx-1-stimulated rat islet proliferation (Fig. 8A).

Fig 8.

Pdx-1 requires ERK1/2 activation for maximal proliferative effect. Primary rat islets were treated with recombinant adenoviruses (AdCMV) expressing β-Gal, Pdx-1, or CnA, as indicated, for 18 h and cultured for an additional 78 h. During the last 48 h, 1 μM cyclosporine (CsA) was added to the culture medium. (A) [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured. **, P < 0.001 compared to control (n = 3). (B) Primary rat islets were left untreated or treated with recombinant adenoviruses (AdCMV) expressing β-Gal or Pdx-1, as indicated, for 18 h and cultured for an additional 78 h. Phosphorylation and protein levels were measured by immunoblot analysis. The immunoblot is representative of three independent experiments. (C and D) 832/13 cells were left untreated or treated with an adenovirus overexpressing Pdx-1 for 4 h. The medium was then changed, and transfection of 50 nM siRNAs was performed 2 h later. Cells were harvested after an additional 72 h of culture. The immunoblot is representative of three independent experiments. (D) Quantification of protein levels. Fold change is the pixel density ratio of phosphorylated ERK1/2 protein levels to total ERK1/2 protein levels normalized to the siScr control. *, P < 0.05 (n = 3). (E) Primary rat islets were left untreated or treated with recombinant adenoviruses (AdCMV) expressing β-Gal or Pdx-1, as indicated, for 18 h and cultured for an additional 78 h. During the last 48 h, 10 μM U0126 was added to the culture medium, and [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured. **, P < 0.001 compared to the control (n = 3). The data represent the means and SEM of three independent experiments. (F) Model of Pdx-1-stimulated rat islet proliferation. The gray text indicates partial inhibition.

We next measured the phosphorylation levels of several signaling molecules and found that Pdx-1 clearly increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation levels in rat islets compared to controls (Fig. 8B). Pdx-1 overexpression and simultaneous knockdown of TRPC3/6 (approximately 60% knockdown of TRPC3/6, as verified by real-time PCR [data not shown]) in 832/13 cells inhibited Pdx-1-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 by approximately 40% relative to siScr control cells (Fig. 8C and D). Furthermore, inhibition of ERK1/2 with the specific MEK1/2 inhibitor (U0126) caused a 35% decrease in Pdx-1-stimulated rat islet proliferation (Fig. 8E). Overall, these data define a novel pathway in which Pdx-1 overexpression induces expression of the calcium channel proteins TRPC3/6, which in turn activate ERK1/2. This pathway is required for full activation of rat islet proliferation and the cyclin D-cdk4 complex in response to Pdx-1 overexpression (a model is shown in Fig. 8F).

DISCUSSION

Loss of functional β-cell mass is central to the development of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Much effort is therefore being directed toward developing strategies for inducing the remaining β cells to proliferate in a controlled manner or growing functional β cells ex vivo for transplantation into diabetic patients. To achieve these goals, it is crucial to understand the mechanisms for inducing β-cell proliferation with retention of key functions. In the present study, we demonstrate that Pdx-1 induces rat islet cells to proliferate and that cooverexpression of Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 causes an additive proliferative effect. Subsequent experiments showed that the two transcription factors mediate proliferation by completely separate mechanisms, including differences in cell type specificity, timing of proliferation, target genes, signaling pathways, and activation of distinct components of the core cell cycle machinery.

Whereas Nkx6.1 induces mainly β-cell proliferation, Pdx-1 stimulates both α- and β-cell proliferation, even though both transcription factors are expressed in all islet cells from the constitutive CMV promoter. While the importance of increasing β-cell proliferation is well known (44), the significance of increasing α-cell proliferation was not fully recognized until recently. Recent studies have suggested that α cells can act as a pool of precursors for α-cell conversion to β cells, leading to β-cell regeneration (45, 46). Several models involving β-cell depletion have been used to demonstrate transdifferentiation of mature α cells into β cells. In one study involving β-cell ablation with diphtheria toxin and lineage tracing, several months were required for complete α-cell conversion to β cells, but impressively, mice eventually became normoglycemic, suggesting that α cells might be a physiologically relevant depot of β-cell progenitors (45). In another model, using pancreatic duct ligation coupled with destruction of β cells with alloxan, α-cell conversion to β cells was demonstrated within 2 weeks (46). More recently, forced expression of Pdx-1 in early endocrine progenitors was shown to cause α-cell conversion to β cells (47). Thus, if Pdx-1 overexpression is sufficient to promote proliferation of mature α cells, as demonstrated in the present study, perhaps Pdx-1 can be used to enhance the efficiency and extent of α-cell transdifferentiation to β cells by increasing the pool of α cells. Further lineage-tracing studies will be required to determine if α cells that are proliferating as a result of Pdx-1 expression undergo cell type conversion.

Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 also differ with regard to the timing of their proliferative effects such that Pdx-1 stimulates proliferation as early as 48 h postransduction (the present study) and Nkx6.1 activates proliferation 72 h postransduction (9). We have recently found that Nkx6.1-mediated proliferation requires upregulation of the orphan nuclear receptors Nr4a1 and Nr4a3. These genes are induced by Nkx6.1 in the first 24 to 48 h of Nkx6.1 overexpression and then require an additional 48 h to exert their effects, thereby explaining the slow induction of proliferation by Nkx6.1 (Tessem, unpublished). In contrast, Pdx-1 induces TRPC3/6 expression, ERK activation, and cyclin D upregulation within 48 h of its expression.

With regard to downstream target genes, both Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 affect the expression of a diverse array of genes. When microarray data sets obtained in primary rat islets 48 h after Pdx-1 or Nkx6.1 overexpression were compared, only 20 genes were found to be commonly induced, whereas approximately 260 and 430 genes were induced by Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 alone, respectively. In addition to the TRPC channels, other calcium-related genes found to be highly upregulated by Pdx-1 in the microarray analysis included the calbindin 1, calbindin 2, Camk1d, CB1, and PKCβ1 genes. These genes have been previously implicated in proliferation, although mostly in non-islet cell studies. However, overexpression or inhibition of these genes via knockdown or use of dominant-negative constructs did not affect islet cell proliferation or interfere with Pdx-1-stimulated proliferation. In contrast, knockdown of TRPC3 and/or TRPC6 significantly inhibited Pdx-1-stimulated rat islet proliferation, underscoring the specific and selective role of these channels in mediating the Pdx-1 proliferative effect. TRP channels are divided into seven subfamilies, and three subfamilies (TRPC, TRPM, and TRPV) have been detected in pancreatic β cells (48). TRP channels are involved in sensing intracellular calcium levels in β cells to mediate different aspects of insulin secretion (49, 50) and may be involved in β-cell stress and islet inflammation via regulation of neuropeptide release from surrounding neuronal cells (51). While TRP channels have been implicated in cellular proliferation in other cell types (38–40), only TRPV2 has been linked to β-cell proliferation in studies with the Min6 mouse insulinoma cell line (52). Thus, to our knowledge, the present study is the first to implicate TRPC3/6 in the regulation of proliferation in adult islet cells.

A pathway downstream of TRP channels that is known to lead to hypertrophy (41) and β-cell proliferation (42, 43) is the calcineurin/NFAT pathway. However, our studies demonstrate that the calcineurin/NFAT pathway is not required for Pdx-1-induced proliferation. Thus, we investigated other potential downstream signaling pathways and found that Pdx-1 increases the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, a known cell cycle regulator (53) that is activated in concert with β-cell expansion and induction of HNF4α (54). Furthermore, it has been shown that calcium influx via TRPC3 can sustain PKCβ and ERK1/2 activation in B cells (55), consistent with our finding that TRPC3/6 expression is necessary for the full activation of ERK1/2 by Pdx-1. The fact that TRPC3/6 knockdown or ERK1/2 inhibition only partially impairs Pdx-1-mediated islet cell proliferation suggests that Pdx-1 may activate additional pathways upstream of the cyclin D-cdk4 complex. Further studies will be required to identify such pathways.

We attempted to define a mechanism by which Pdx-1 regulates TRPC channels by transfecting 832/13 insulinoma cells with an 1,800-bp fragment of the human TRPC3 promoter driving a luciferase reporter gene (30) and then overexpressing Pdx-1 via our adenoviral vector. In these assays, Pdx-1 caused only a trend toward increased luciferase reporter activity that was not statistically significant. Moreover, we analyzed a recent chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis of Pdx-1 binding sites (56) and found that it did not reveal any sites in the vicinity of the TRPC3 or TRPC6 gene, consistent with the lack of signal in the reporter gene analysis. Possible explanations for these findings include the need for other regulatory sequences at some distance from the TRPC genes or Pdx-1 producing its effects via an indirect mechanism.

The final difference between Pdx-1- and Nkx6.1-stimulated proliferation uncovered in this study is the involvement of different core cell cycle factors. Previous studies have shown that cdk4, cyclin D2, and cyclin D1/D2 knockout mice have decreased β-cell mass, resulting in diabetes (57, 58). The present study shows that the cyclin D-cdk4 complex is required for Pdx-1-stimulated proliferation but also demonstrates that these core cell cycle molecules are not required in all instances of adult β-cell proliferation, because blocking the cyclin D-cdk4 complex does not inhibit Nkx6.1-stimulated proliferation. This is consistent with our prior studies showing that Nkx6.1 induces the expression of cyclins E, A, and B but not D and that overexpression of cyclin E is sufficient to activate islet cell replication (9). Interestingly, a previous study has shown that cyclin D2-cdk4-GLP1 overexpression preferentially induces β-cell proliferation, whereas cyclin D2-cdk4 overexpression preferentially induces α-cell proliferation (59). This suggests the possibility that additional factors acting upstream of cyclin D-cdk4 exist that focus the proliferative effects of Pdx-1 in β cells. Further studies are required to elucidate the potential cell-type-specific mechanisms of Pdx-1-stimulated proliferation.

In conclusion, our findings map out a novel pathway by which Pdx-1 stimulates islet cell replication. Knowledge of this pathway and the separate one by which Nkx6.1 induces proliferation may lead to identification of small molecules that target key components of these pathways for expansion of functional β-cell mass in diabetes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health β-Cell Biology Consortium (BCBC) (U01 DK-089538) to H.E.H. and C.B.N., Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) grants 17-2011-15 (to C.B.N.) and 17-2011-614 (to H.E.H.), and a JDRF postdoctoral fellowship to H.L.H. (3-2009-561).

We thank Samuel Stephens and Jeffery Tessem for helpful advice and discussion, as well as Danhong Lu, Helena Winfield, Lisa Poppe, and Paul Anderson for expert technical assistance. We thank the Duke Microarray Core facility (a Duke National Cancer Institute and a Duke Institute for Genome Sciences and Policy shared resource facility) for their assistance in generating the microarray data reported in the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 12 August 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00469-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weir GC, Bonner-Weir S. 2004. Five stages of evolving beta-cell dysfunction during progression to diabetes. Diabetes 53(Suppl 3):S16–S21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouwens L, Rooman I. 2005. Regulation of pancreatic beta-cell mass. Physiol. Rev. 85:1255–1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muoio DM, Newgard CB. 2008. Mechanisms of disease: molecular and metabolic mechanisms of insulin resistance and beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:193–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hohmeier HE, Newgard CB. 2005. Islets for all? Nat. Biotechnol. 23:1231–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de la Tour D, Halvorsen T, Demeterco C, Tyrberg B, Itkin-Ansari P, Loy M, Yoo SJ, Hao E, Bossie S, Levine F. 2001. Beta-cell differentiation from a human pancreatic cell line in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Endocrinol. 15:476–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beattie GM, Montgomery AM, Lopez AD, Hao E, Perez B, Just ML, Lakey JR, Hart ME, Hayek A. 2002. A novel approach to increase human islet cell mass while preserving beta-cell function. Diabetes 51:3435–3439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiaschi-Taesch NM, Salim F, Kleinberger J, Troxell R, Cozar-Castellano I, Selk K, Cherok E, Takane KK, Scott DK, Stewart AF. 2010. Induction of human beta-cell proliferation and engraftment using a single G1/S regulatory molecule, cdk6. Diabetes 59:1926–1936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rieck S, Zhang J, Li Z, Liu C, Naji A, Takane KK, Fiaschi-Taesch NM, Stewart AF, Kushner JA, Kaestner KH. 2012. Overexpression of hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha initiates cell cycle entry, but is not sufficient to promote beta-cell expansion in human islets. Mol. Endocrinol. 26:1590–1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schisler JC, Fueger PT, Babu DA, Hohmeier HE, Tessem JS, Lu D, Becker TC, Naziruddin B, Levy M, Mirmira RG, Newgard CB. 2008. Stimulation of human and rat islet beta-cell proliferation with retention of function by the homeodomain transcription factor Nkx6.1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28:3465–3476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaffer AE, Yang AJ, Thorel F, Herrera PL, Sander M. 2011. Transgenic overexpression of the transcription factor Nkx6.1 in beta-cells of mice does not increase beta-cell proliferation, beta-cell mass, or improve glucose clearance. Mol. Endocrinol. 25:1904–1914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hohmeier HE, Tran VV, Chen G, Gasa R, Newgard CB. 2003. Inflammatory mechanisms in diabetes: lessons from the beta-cell. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 27(Suppl 3):S12–S16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaminitz A, Stein J, Yaniv I, Askenasy N. 2007. The vicious cycle of apoptotic beta-cell death in type 1 diabetes. Immunol. Cell Biol. 85:582–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brissova M, Shiota M, Nicholson WE, Gannon M, Knobel SM, Piston DW, Wright CV, Powers AC. 2002. Reduction in pancreatic transcription factor PDX-1 impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 277:11225–11232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson JD, Ahmed NT, Luciani DS, Han Z, Tran H, Fujita J, Misler S, Edlund H, Polonsky KS. 2003. Increased islet apoptosis in Pdx1+/− mice. J. Clin. Invest. 111:1147–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujimoto K, Hanson PT, Tran H, Ford EL, Han Z, Johnson JD, Schmidt RE, Green KG, Wice BM, Polonsky KS. 2009. Autophagy regulates pancreatic beta cell death in response to Pdx1 deficiency and nutrient deprivation. J. Biol. Chem. 284:27664–27673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sachdeva MM, Claiborn KC, Khoo C, Yang J, Groff DN, Mirmira RG, Stoffers DA. 2009. Pdx1 (MODY4) regulates pancreatic beta cell susceptibility to ER stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:19090–19095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Habener JF, Kemp DM, Thomas MK. 2005. Minireview: transcriptional regulation in pancreatic development. Endocrinology 146:1025–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonsson J, Carlsson L, Edlund T, Edlund H. 1994. Insulin-promoter-factor 1 is required for pancreas development in mice. Nature 371:606–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Offield MF, Jetton TL, Labosky PA, Ray M, Stein RW, Magnuson MA, Hogan BL, Wright CV. 1996. PDX-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development 122:983–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stephens SB, Schisler JC, Hohmeier HE, An J, Sun AY, Pitt GS, Newgard CB. 2012. A VGF-derived peptide attenuates development of type 2 diabetes via enhancement of islet beta-cell survival and function. Cell Metab. 16:33–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu SH, Patel S, Gingras MC, Nemunaitis J, Zhou G, Chen C, Li M, Fisher W, Gibbs R, Brunicardi FC. 2011. PDX-1: demonstration of oncogenic properties in pancreatic cancer. Cancer 117:723–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kushner JA, Ye J, Schubert M, Burks DJ, Dow MA, Flint CL, Dutta S, Wright CV, Montminy MR, White MF. 2002. Pdx1 restores beta cell function in Irs2 knockout mice. J. Clin. Invest. 109:1193–1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahlgren U, Jonsson J, Jonsson L, Simu K, Edlund H. 1998. Beta-cell-specific inactivation of the mouse Ipf1/Pdx1 gene results in loss of the beta-cell phenotype and maturity onset diabetes. Genes Dev. 12:1763–1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feanny MA, Fagan SP, Ballian N, Liu SH, Li Z, Wang X, Fisher W, Brunicardi FC, Belaguli NS. 2008. PDX-1 expression is associated with islet proliferation in vitro and in vivo. J. Surg. Res. 144:8–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu T, Wang CY, Gou SM, Wu HS, Xiong JX, Zhou J. 2007. PDX-1 expression and proliferation of duct epithelial cells after partial pancreatectomy in rats. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 6:424–429 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hohmeier HE, Mulder H, Chen G, Henkel-Rieger R, Prentki M, Newgard CB. 2000. Isolation of INS-1-derived cell lines with robust ATP-sensitive K+ channel-dependent and -independent glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes 49:424–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milburn JL, Jr, Hirose H, Lee YH, Nagasawa Y, Ogawa A, Ohneda M, Beltran del Rio H, Newgard CB, Johnson JH, Unger RH. 1995. Pancreatic beta-cells in obesity. Evidence for induction of functional, morphologic, and metabolic abnormalities by increased long chain fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem. 270:1295–1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naber SP, McDonald JM, Jarett L, McDaniel ML, Ludvigsen CW, Lacy PE. 1980. Preliminary characterization of calcium binding in islet-cell plasma membranes. Diabetologia 19:439–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schisler JC, Jensen PB, Taylor DG, Becker TC, Knop FK, Takekawa S, German M, Weir GC, Lu D, Mirmira RG, Newgard CB. 2005. The Nkx6.1 homeodomain transcription factor suppresses glucagon expression and regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in islet beta cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:7297–7302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg P, Hawkins A, Stiber J, Shelton JM, Hutcheson K, Bassel-Duby R, Shin DM, Yan Z, Williams RS. 2004. TRPC3 channels confer cellular memory of recent neuromuscular activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:9387–9392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He TC, Zhou S, da Costa LT, Yu J, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. 1998. A simplified system for generating recombinant adenoviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:2509–2514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bain JR, Schisler JC, Takeuchi K, Newgard CB, Becker TC. 2004. An adenovirus vector for efficient RNA interference-mediated suppression of target genes in insulinoma cells and pancreatic islets of Langerhans. Diabetes 53:2190–2194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lavine JA, Raess PW, Davis DB, Rabaglia ME, Presley BK, Keller MP, Beinfeld MC, Kopin AS, Newgard CB, Attie AD. 2010. Contamination with E1A-positive wild-type adenovirus accounts for species-specific stimulation of islet cell proliferation by CCK: a cautionary note. Mol. Endocrinol. 24:464–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ronnebaum SM, Ilkayeva O, Burgess SC, Joseph JW, Lu D, Stevens RD, Becker TC, Sherry AD, Newgard CB, Jensen MV. 2006. A pyruvate cycling pathway involving cytosolic NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 281:30593–30602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cozar-Castellano I, Takane KK, Bottino R, Balamurugan AN, Stewart AF. 2004. Induction of beta-cell proliferation and retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation in rat and human islets using adenovirus-mediated transfer of cyclin-dependent kinase-4 and cyclin D1. Diabetes 53:149–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winn MP, Conlon PJ, Lynn KL, Farrington MK, Creazzo T, Hawkins AF, Daskalakis N, Kwan SY, Ebersviller S, Burchette JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Howell DN, Vance JM, Rosenberg PB. 2005. A mutation in the TRPC6 cation channel causes familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Science 308:1801–1804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding X, He Z, Zhou K, Cheng J, Yao H, Lu D, Cai R, Jin Y, Dong B, Xu Y, Wang Y. 2010. Essential role of TRPC6 channels in G2/M phase transition and development of human glioma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 102:1052–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woo JS, Cho CH, Kim do H, Lee EH. 2010. TRPC3 cation channel plays an important role in proliferation and differentiation of skeletal muscle myoblasts. Exp. Mol. Med. 42:614–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeng B, Yuan C, Yang X, Atkin SL, Xu SZ. 2013. TRPC channels and their splice variants are essential for promoting human ovarian cancer cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 13:103–116 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Onohara N, Nishida M, Inoue R, Kobayashi H, Sumimoto H, Sato Y, Mori Y, Nagao T, Kurose H. 2006. TRPC3 and TRPC6 are essential for angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. EMBO J. 25:5305–5316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heit JJ, Apelqvist AA, Gu X, Winslow MM, Neilson JR, Crabtree GR, Kim SK. 2006. Calcineurin/NFAT signalling regulates pancreatic beta-cell growth and function. Nature 443:345–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soleimanpour SA, Crutchlow MF, Ferrari AM, Raum JC, Groff DN, Rankin MM, Liu C, De Leon DD, Naji A, Kushner JA, Stoffers DA. 2010. Calcineurin signaling regulates human islet {beta}-cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 285:40050–40059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weir GC, Cavelti-Weder C, Bonner-Weir S. 2011. Stem cell approaches for diabetes: towards beta cell replacement. Genome Med. 3:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thorel F, Nepote V, Avril I, Kohno K, Desgraz R, Chera S, Herrera PL. 2010. Conversion of adult pancreatic alpha-cells to beta-cells after extreme beta-cell loss. Nature 464:1149–1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chung CH, Hao E, Piran R, Keinan E, Levine F. 2010. Pancreatic beta-cell neogenesis by direct conversion from mature alpha-cells. Stem Cells 28:1630–1638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang YP, Thorel F, Boyer DF, Herrera PL, Wright CV. 2011. Context-specific alpha- to-beta-cell reprogramming by forced Pdx1 expression. Genes Dev. 25:1680–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uchida K, Tominaga M. 2011. The role of thermosensitive TRP (transient receptor potential) channels in insulin secretion. Endocr. J. 58:1021–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uchida K, Tominaga M. 2011. TRPM2 modulates insulin secretion in pancreatic beta-cells. Islets 3:209–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Colsoul B, Vennekens R, Nilius B. 2011. Transient receptor potential cation channels in pancreatic beta cells. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 161:87–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Razavi R, Chan Y, Afifiyan FN, Liu XJ, Wan X, Yantha J, Tsui H, Tang L, Tsai S, Santamaria P, Driver JP, Serreze D, Salter MW, Dosch HM. 2006. TRPV1+ sensory neurons control beta cell stress and islet inflammation in autoimmune diabetes. Cell 127:1123–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hisanaga E, Nagasawa M, Ueki K, Kulkarni RN, Mori M, Kojima I. 2009. Regulation of calcium-permeable TRPV2 channel by insulin in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes 58:174–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chambard JC, Lefloch R, Pouyssegur J, Lenormand P. 2007. ERK implication in cell cycle regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1773:1299–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gupta RK, Gao N, Gorski RK, White P, Hardy OT, Rafiq K, Brestelli JE, Chen G, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Kaestner KH. 2007. Expansion of adult beta-cell mass in response to increased metabolic demand is dependent on HNF-4alpha. Genes Dev. 21:756–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Numaga T, Nishida M, Kiyonaka S, Kato K, Katano M, Mori E, Kurosaki T, Inoue R, Hikida M, Putney JW, Jr, Mori Y. 2010. Ca2+ influx and protein scaffolding via TRPC3 sustain PKCbeta and ERK activation in B cells. J. Cell Sci. 123:927–938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khoo C, Yang J, Weinrott SA, Kaestner KH, Naji A, Schug J, Stoffers DA. 2012. Research resource: the pdx1 cistrome of pancreatic islets. Mol. Endocrinol. 26:521–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rane SG, Dubus P, Mettus RV, Galbreath EJ, Boden G, Reddy EP, Barbacid M. 1999. Loss of Cdk4 expression causes insulin-deficient diabetes and Cdk4 activation results in beta-islet cell hyperplasia. Nat. Genet. 22:44–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kushner JA, Ciemerych MA, Sicinska E, Wartschow LM, Teta M, Long SY, Sicinski P, White MF. 2005. Cyclins D2 and D1 are essential for postnatal pancreatic beta-cell growth. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:3752–3762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen S, Shimoda M, Chen J, Matsumoto S, Grayburn PA. 2012. Transient overexpression of cyclin D2/CDK4/GLP1 genes induces proliferation and differentiation of adult pancreatic progenitors and mediates islet regeneration. Cell Cycle 11:695–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.