Abstract

Dilated chronic cardiomyopathy (DCC) from Chagas disease is associated with myocardial remodeling and interstitial fibrosis, resulting in extracellular matrix (ECM) changes. In this study, we characterized for the first time the serum matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) and MMP-9 levels, as well as their main cell sources in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients presenting with the indeterminate (IND) or cardiac (CARD) clinical form of Chagas disease. Our results showed that serum levels of MMP-9 are associated with the severity of Chagas disease. The analysis of MMP production by T lymphocytes showed that CD8+ T cells are the main mononuclear leukocyte source of both MMP-2 and MMP-9 molecules. Using a new 3-dimensional model of fibrosis, we observed that sera from patients with Chagas disease induced an increase in the extracellular matrix components in cardiac spheroids. Furthermore, MMP-2 and MMP-9 showed different correlations with matrix proteins and inflammatory cytokines in patients with Chagas disease. Our results suggest that MMP-2 and MMP-9 show distinct activities in Chagas disease pathogenesis. While MMP-9 seems to be involved in the inflammation and cardiac remodeling of Chagas disease, MMP-2 does not correlate with inflammatory molecules.

INTRODUCTION

Chagas disease, a neglected disease caused by Trypanosoma cruzi, remains a serious public health problem and affects about 10 million people in Latin America (1). During the chronic phase, most patients remain in the asymptomatic clinical form (indeterminate), which can last their whole lifetimes. However, about 20 to 30% of the patients develop the cardiac form of the disease, which can be complicated by cardiac arrhythmias, heart failure, stroke, and sudden death (2, 3). Chagas heart disease is characterized by intense myocarditis of an inflammatory nature with a progressive fibrotic process affecting the myocardium of both ventricles, which leads to myocardial remodeling, interstitial fibrosis, and changes in the extracellular matrix (ECM) (4–6). The ECM remodeling is regulated by proteolytic enzymes, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (7).

MMPs are important enzymes that participate in many physiological and pathological conditions by degrading ECM molecules (e.g., collagen, laminin, and fibronectin) and by releasing cryptic epitopes from the ECM (7–11). However, these enzymes have a spectrum of biological functions and also act on several biomolecules, including cytokines, hormones, and chemokines (7, 8).

Among the MMPs, MMP-2 and MMP-9 are well known for their involvement in the pathogenesis of a wide spectrum of cardiovascular disorders (9, 10, 12–16) and are able to degrade all components of the heart matrix, contributing to the ECM remodeling that occurs with progressive ventricular dilatation (12–14).

The participation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 has been studied in experimental T. cruzi infection. Gutierrez et al. (17) showed in experimental T. cruzi infection that the inhibition of MMP-2 and MMP-9 decreased inflammation and improved the prognosis of the infected animals. However, the involvement of MMPs in human Chagas disease has not yet been explored. In this study, we showed for the first time that MMP-2 and MMP-9, as well as interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), may be differentially involved in cardiac remodeling in patients with the indeterminate and cardiac forms of Chagas disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

The patients with Chagas disease who agreed to participate in this study were identified and selected at the Referral Outpatient Center for Chagas Disease at the Clinical Hospital of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), Minas Gerais, Brazil, and at Evandro Chagas Clinical Research Institute (IPEC) at Fundação Oswaldo Cruz-Rio de Janeiro (FIOCRUZ-RJ), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Patients who consented to participate in this study were enrolled in a prospective cohort study initiated 15 years ago as previously described (18). The patients were grouped as indeterminate (IND) and cardiac (CARD) patients, as previously reported (5, 6). The IND group included individuals ranging in age from 36 to 65 years (average age, 53 ± 17 years), with no significant alterations in their electrocardiograms, chest X-rays, echocardiograms, esophagograms, and barium enemas. The CARD patients included individuals ranging in age from 35 to 69 years (average age, 52 ± 17 years). All patients in the CARD group presented with dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure, and their left ventricle ejection fractions averaged 42% ± 14%. Healthy individuals, ranging in age from 30 to 49 years (average age, 39 ± 9 years), with a normal physical examination, electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram and negative serological tests for Chagas disease, were included as a control group (noninfected [NI]).

Ethics statement.

Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals prior to their inclusion in the study. This study was carried out in full accordance with all International and Brazilian accepted guidelines and was approved by the Ethics Committee at Centro de Pesquisas René Rachou-FIOCRUZ (15/2011 CEPSH-IRR), UFMG (ETIC 001/97), and IPEC (CAAE 0058.0.009.000-09).

Serum MMP-2 and MMP-9 measurement.

Ten milliliters of peripheral blood was collected without anticoagulant for serum separation. MMP-2 and MMP-9 concentrations were determined using a Milliplex Kit (Lifescience) with Luminex xMAP technology. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions at a serum dilution of 1:20. Briefly, the methodology uses digital signal processing capable of classifying polystyrene beads (microspheres) dyed with distinct proportions of two fluorophores. A fluorescent Streptavidin-phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antibody is added for the identification of MMP concentrations by their mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). The results are expressed in nanograms per milliliter.

Gelatin zymography.

MMP-2 and MMP-9 were examined by gelatin zymography of serum samples. Forty micrograms of protein from serum were electrophoresed through a 12% polyacrylamide gel copolymerized with gelatin (1 mg/ml; type A from porcine skin; Sigma). After electrophoresis, the gels were washed with 2.5% Triton X-100 diluted in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, and incubated overnight at 37°C in 50 mM Tris and 10 mM CaCl2 solution. Staining was performed using Coomassie brilliant blue (R-250; Bio-Rad), and the gels were destained using specific solution (250 ml ethanol, 80 ml acetic acid). Clear gelatinolytic bands on a uniform blue background were measured by densitometry with the image analyzer GS-800 Calibrated Densitometer (Bio-Rad). Band intensities were quantified using Quantity One software.

Flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood.

Whole blood was collected in Vacutainer tubes containing EDTA (Becton, Dickinson, USA), and 100-μl samples were mixed in tubes with 2 μl of undiluted monoclonal antibodies conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), PE, peridinin chlorophyll protein complex (PerCP), or allophycocyanin (APC) for the following molecules: CD14 (MΦP9), CD8 (HIT8a), CD8 (SK1), and CD4 (RPA-T4) (BD Pharmingen USA). Antibodies were added, and the cells were incubated and washed after erythrocyte lysis. The cells were then permeabilized and incubated with monoclonal antibodies against MMP-2 (1A10) or MMP-9 (56129) (R&D Systems, USA) conjugated with PE or FITC, respectively. After incubation, the cells were fixed, and phenotypic analyses were performed by flow cytometry using a Becton, Dickinson FACSCalibur cytometer. The analyses were performed using FlowJo software (Treestar, USA), gating 7 × 104 cells according to their forward and side scatter properties. Specific gating strategies were used to select the lymphocyte and monocyte populations, as previously described (19).

Detection of cytokine and chemokine levels in sera with a CBA.

The Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) immunoassay kit (BD Biosciences, USA) was used for TNF-α and IL-1β measurements as recommended by the manufacturer and as previously described (18, 20). Data were acquired in a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton, Dickinson), and the analyses were performed using CBA software (Becton, Dickinson). The results were expressed in picograms per milliliter.

Primary cardiac cell cultures and cardiac spheroid serum treatment.

Swiss Webster mice were obtained from CECAL-FIOCRUZ. They were bred and manipulated according to approved recommendations of the FIOCRUZ Ethics Committee for Animal Use (CEUA-FIOCRUZ protocol 232/04). The hearts of 18-day-old mouse embryos were subjected to enzymatic dissociation using 0.05% trypsin and 0.01% collagenase in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2) at 37°C, as previously described (21). To allow formation of cardiac spheroids (three-dimensional [3D] microtissues), 2.5 × 104 cardiomyocytes were plated in agarose-coated 96-U-well plastic plates as described previously (22). After 1 week of culture, the 3D microtissues were incubated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 5% sera from patients with Chagas disease or noninfected individuals in a 24-well plate. The cultures were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 72 h.

Immunoblotting.

The immunoblotting technique was performed as previously described (23, 24). Briefly, after serum treatment, cardiac spheroids were washed, lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM ethylene glycol-bis-(β-amino-ethyl ether)N,N,N′,N′-tetra-acetic acid, pH 8.0, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)], and sonicated, and the protein concentration was measured using the RC-DC protein quantification kit (Bio-Rad). Proteins in the lysates (10 μg/lane) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (12%), followed by transfer and incubation with specific antibodies. The antibodies used were anti-MMP-2 (1:1,000), anti-MMP-9 (1:1,000), anti-laminin (1:1,000), anti-fibronectin (1:5,000), and anti-connexin 43 (1:10,000), all from Sigma, and rabbit polyclonal anti-collagen type 1 (1:5,000) from Novatec. After incubation with a secondary goat anti-rabbit-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) IgG and secondary goat anti-mouse-HRP IgG antibody (Pierce Thermo Scientific), the membranes were washed and incubated with a Super Signal West Pro chemiluminescence kit (Pierce Biotechnology) and exposed to X-ray film. The films were scanned, and protein quantification was performed with Quantity One software. Western blot results were normalized by values of GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) for each sample in the same gel.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 software (San Diego, CA, USA). The following nonparametric tests were performed: the Mann-Whitney test when comparing two groups and the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's post hoc analysis test when comparing three or more groups. Correlation analyses were done using Pearson's correlation coefficient (JMP software; SAS). In all cases, significance was considered to be a P value of ≤0.05.

RESULTS

Serum levels of MMP-9 are associated with the severity of Chagas disease.

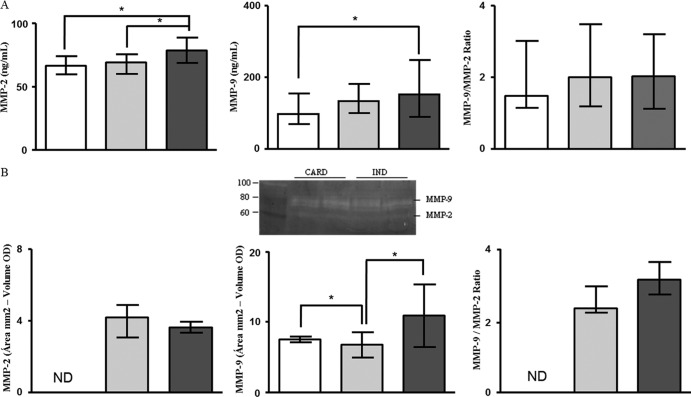

Several studies have shown that extracellular matrix degradation by MMPs, specifically MMP-2 and MMP-9, is involved in the pathogenesis of a wide spectrum of cardiovascular disorders (9, 12–15, 25). In order to investigate the involvement of these MMPs in Chagas disease, we measured the levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in sera from patients with Chagas disease and noninfected individuals by Milliplex assay and zymography. Milliplex is based on immunoreactivity and may also measure the MMP-tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP) complex (indistinguishable from free MMP) and degradation products. On the other hand, zymography visualizes only enzyme forms, not the MMP-TIMP complex, and this type of analysis might give the false impression that the samples contain activity (16, 26). The results of the Milliplex assay showed that patients from the CARD group presented higher levels of MMP-2 in serum than the IND (P = 0.006) and NI (P = 0.002) groups (Fig. 1A). The serum MMP-9 levels from the CARD group were also higher than those from the NI group (P = 0.04) (Fig. 1A). Aiming to compare the MMP-9 and MMP-2 levels, we calculated the relative index, considering the MMP-9/MMP-2 ratio. Although the serum MMP-9 levels were higher than those of MMP-2, the MMP-9/MMP-2 ratio did not show any significant differences between the groups (Fig. 1A).

Fig 1.

Analysis of serum levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9. The analysis of serum levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 by Milliplex assay (A) and by zymography (B) was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The groups evaluated were IND (n = 23; gray bars), CARD (n = 27; dark-gray bars), and NI (n = 25; white bars). The serum level data are expressed as medians with interquartile ranges. The results of zymography were obtained by subtracting the values of the area (mm2) of the selected band and the volume (optical density [OD]) and are expressed as medians with interquartile ranges. The proteolytic band that indicates MMPs is represented in panel B. Significant differences (P < 0.05) in the charts are identified by connecting lines and asterisks for comparisons between the groups.

Gelatin zymography was carried out on sera from the same patients in order to confirm the above-described results. MMP-2 levels were undetectable in serum samples from NI individuals, and no statistical difference was observed between the IND and CARD groups (Fig. 1B). The results still showed that MMP-9 levels were higher in serum samples from the CARD group than in those from the IND group (P = 0.003). Moreover, MMP-9 levels were lower in serum samples from the IND group than in those from NI individuals (P = 0.002) (Fig. 1B). The MMP-9/MMP-2 level ratios were similar between the IND and CARD groups (Fig. 1B). A correlation analysis between the Milliplex and zymography data was done, but significant correlations were not found (data not shown).

CD8+ T cells are the main mononuclear leukocyte source of MMP-2 and MMP-9 molecules.

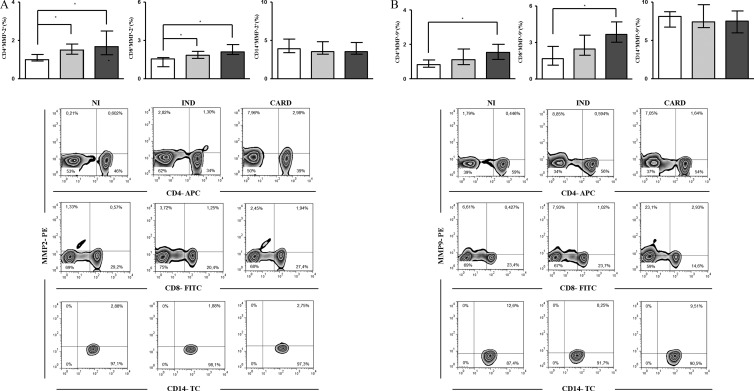

The increased levels of MMP-9 in serum samples from CARD patients suggested a role of this MMP in the pathogenesis of cardiomyopathy. Some previous studies showed that monocytes/macrophages and lymphocytes are able to secrete MMPs (27, 28). Considering that monocytes/macrophages and lymphocytes are important during T. cruzi infection and play a major role in driving distinct patterns of the immune response in the IND and CARD groups (29, 30), we investigated the frequencies and cellular sources of MMP-2- and MMP-9-producing cells within the mononuclear leukocyte population. Our findings demonstrated that both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from IND and CARD patients showed higher intracellular expression of MMP-2 than CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from NI individuals (P < 0.005) (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, only the CARD group showed a percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells coexpressing MMP-9 higher than that of the NI group (P < 0.005) (Fig. 2B). However, no difference was observed in the MMP-2 or MMP-9 expression by monocytes (CD14+ cells) in all groups (Fig. 2A and B).

Fig 2.

Ex vivo analysis of intracytoplasmic levels of MMP-2 (A) and MMP-9 (B) in lymphocytes and monocytes. The groups evaluated were IND (n = 7; gray bars), CARD (n = 10; dark-gray bars), and NI (n = 6; white bars). The data are expressed as the median percentages of T lymphocytes and monocytes with interquartile ranges. Significant differences (P < 0.05) in the charts are identified by connecting lines and asterisks for comparisons between the groups. Flow cytometric analyses are shown below.

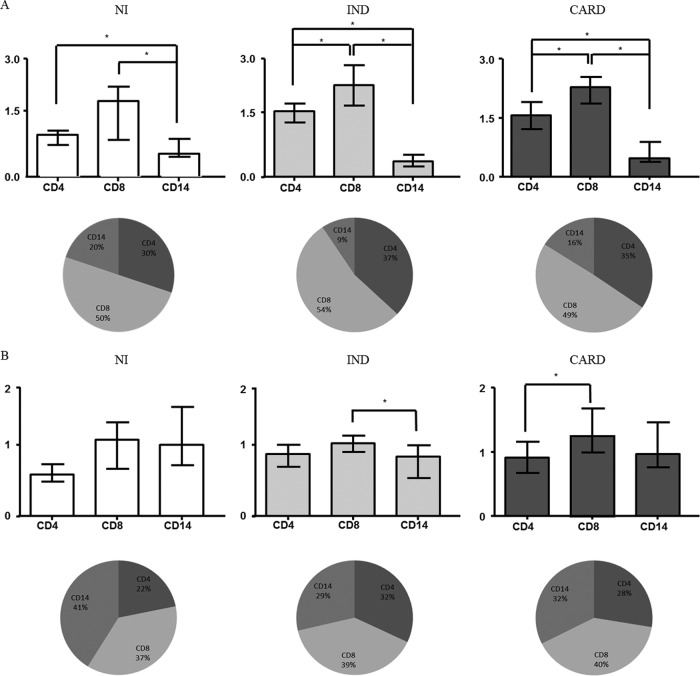

In order to identify the most relevant source of MMP-2 and MMP-9 within the mononuclear cell subsets, additional analysis was carried out to provide evidence regarding the number of MMP-2+ and MMP-9+ mononuclear cells (Fig. 3). Our results showed that, in all groups, CD8+ T cells are the main cell source for MMP-2 production among the cells evaluated (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, in patients with Chagas disease, the majority of MMP-9 production was also derived from CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3B).

Fig 3.

Evaluation of MMP-2- and MMP-9-producing peripheral blood mononuclear cells and their subpopulations. Shown is analysis of the most relevant sources of MMP-2 (A) and MMP-9 (B) within the mononuclear cell subsets. The cells evaluated were monocytes and CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. The data are expressed as the median numbers of MMP-producing cells with interquartile ranges. The data are also shown as pie charts, which represent the proportions of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and CD14 monocytes within MMP-2- and MMP-9-producing mononuclear cells. Significant differences (P < 0.05) in the charts are identified by connecting lines and asterisks for comparisons between the groups.

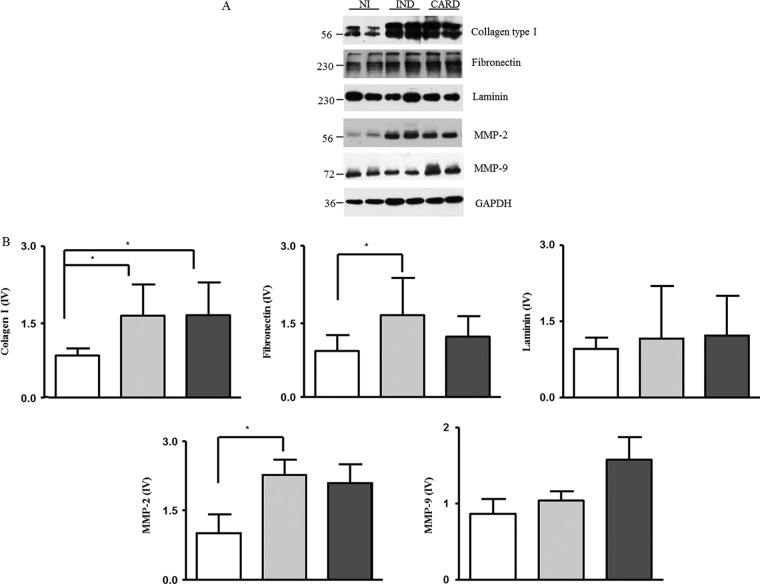

Sera from patients with Chagas disease induced an increase in the extracellular matrix components in cardiac spheroids.

We performed three-dimensional cardiomyocyte culture experiments to test whether the sera from patients with Chagas disease are capable of inducing the expression of extracellular matrix proteins by cardiomyocytes. Our results showed a higher expression of collagen type I when spheroids were incubated in contact with sera from the IND and CARD groups than with sera from the NI group (P = 0.003 and P = 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 4). The fibronectin and MMP-2 expression levels were higher in spheroids stimulated with sera from the IND group than in those stimulated with sera from the NI group (P = 0.01 and P = 0.03, respectively) (Fig. 4). On the other hand, laminin and MMP-9 expression levels were not different between the groups. However, we observed a tendency toward higher expression of MMP-9 in spheroids in contact with sera from CARD patients (Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

Evaluation of matrix protein expression in cardiac spheroids. (A) Bands that represent the expression of each matrix protein. (B) The matrix proteins were evaluated from 3D microtissues incubated with sera from individuals from the NI group (n = 10; white bars) and patients with IND (n = 10; gray bars) and CARD (n = 10; dark-gray bars) Chagas disease. The data are expressed as the means of matrix protein expression plus standard errors. Significant differences (P < 0.05) in the charts are identified by connecting lines and asterisks for comparisons between the groups.

MMP-2 and MMP-9 are correlated with the cardiac spheroid remodeling induced by sera of patients with Chagas disease.

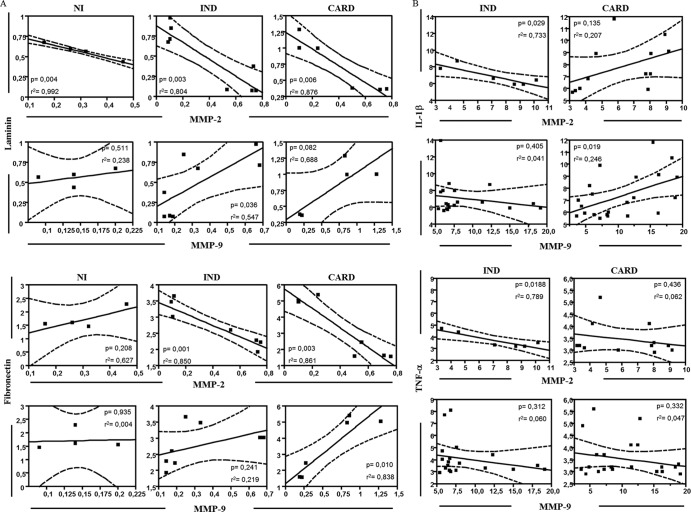

The MMPs are involved in the remodeling of cardiac tissue by degrading ECM molecules (7, 31). In order to confirm if the presence of MMPs correlates with ECM proteins and a possible role of these molecules in the cardiac remodeling of Chagas disease, we performed a correlative analysis. A significant negative correlation was seen between MMP-2 expression and laminin expression in all groups (Fig. 5A). However, a significant positive correlation was observed between MMP-9 expression and laminin expression in the IND group (Fig. 5A). Regarding fibronectin, a significant negative correlation was seen between MMP-2 expression and fibronectin expression in the IND and CARD groups (Fig. 5A). However, a significant positive correlation was observed between MMP-9 expression and fibronectin expression in the CARD group (Fig. 5A). There was no significant correlation between MMPs and collagen expression in the studied groups (data not shown).

Fig 5.

Correlation analysis of MMP-2 and MMP-9 with matrix proteins and inflammatory cytokines. (A) Correlation analysis of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression with laminin and fibronectin was done with data from cardiac spheroid culture. (B) Correlation analysis of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression with IL-1β and TNF-α was done with data from sera. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used for correlation analysis, and results with a P value of <0.05 were considered significant. Significant differences (P value) are indicated in each graph, together with the r2 value. The filled squares represent the samples evaluated. The solid lines represent the linear regression lines. The dashed lines represent the distribution of the samples from the linear regression lines. For MMPs, the unit of measurement is ng/ml. For cytokines IL-10 and TNF-α, the units of measurement are MFI. For laminin and fibronectin, there are no units of measurement, because the values were obtained from evaluation of the variation index of protein expression.

MMP-9 seems to be involved with the inflammation and cardiac remodeling of Chagas disease, whereas MMP-2 does not correlate with inflammatory molecules.

Our next step was to analyze the correlation between serum TNF-α and IL-1β levels and MMP levels measured by zymography, since TNF-α and IL-1β are the main cytokines involved in MMP activation (10, 32, 33). A significant negative correlation was seen between MMP-2 levels and serum IL-1β levels in the IND group (Fig. 5B). However, a positive correlation was observed between MMP-2 levels and serum IL-1β levels in the CARD group (Fig. 5B). A negative correlation was seen between MMP-9 levels and serum IL-1β levels in the IND group (Fig. 5B). On the other hand, a significant positive correlation was observed between MMP-9 levels and serum IL-1β levels in the CARD group (Fig. 5B). Regarding TNF-α levels, a significant negative correlation was seen between MMP-2 levels and TNF-α levels in the IND group (Fig. 5B). However, no significant correlation was observed either between MMP-2 levels and TNF-α levels in the CARD group (Fig. 5B) or between MMP-9 levels and TNF-α levels in both the IND and CARD groups (Fig. 5B).

Overall, our results suggest that MMP-2 and MMP-9, as well as IL-1β and TNF-α, may be differentially involved in cardiac remodeling in the IND and CARD groups.

DISCUSSION

Chronic Chagas disease has a great variety of clinical presentations even within patients with the cardiac form. Although the classification of the cardiac form into stages helps to distinguish patients with worse prognosis (34), sudden death and other major clinical events still occur among patients in the initial stages of Chagas heart disease. Therefore, one of the most important goals of studying physiopathological mechanisms in Chagas disease is the identification of potential risk factors for the occurrence of major clinical events (sudden death, heart failure, malignant arrhythmias, and stroke) or disease progression among patients still in the indeterminate form or in initial stages of the cardiac form (5, 6). Chagas heart disease is characterized by an intense and progressive fibrotic process (4), and the study of biomarkers involved in the establishment and development of fibrosis is essential to identify such potential risk factors (35).

In this study, we characterized for the first time the serum levels of MMP-2 and -9, their potential proteolytic activity, as well as their main sources within mononuclear cells in human Chagas disease. Although there are no reports about the putative role of MMPs in human Chagas disease, the involvement of MMPs in other cardiac diseases, particularly in the cardiac matrix remodeling that occurs in heart failure and after acute myocardial infarction, has been widely studied (12–14, 36, 37, 38, 48).

Our results showed that patients with Chagas heart disease complicated by heart failure present higher serum levels of MMP-9 (Fig. 1). Moreover, experimental studies pointed out that MMP serum levels may be associated with cardiovascular complications of hypertension (49). Polyakova et al. (14) showed that elevated expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 is associated with collagen maturation in heart failure, demonstrating an important role of these enzymes in fibrosis through collagen configuration, activation, and deposition. In experimental models of Chagas disease, high MMP-2 and -9 proteolytic activity had already been described, which suggested an important role for MMPs in T. cruzi-induced acute myocarditis (17). Here, we showed elevated levels of these enzymes in chronic Chagas disease. Furthermore, the ratio analysis showed that MMP-9 levels were higher than those of MMP-2 (Fig. 1A), which is corroborated by others (12) who reported that MMP-2 is produced at lower levels than MMP-9 by several cell types.

Our group previously showed the essential role of immune cells, such as monocytes (39) and lymphocytes (18, 40), in Chagas disease pathogenesis. In the present study, we observed that CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and CD14+ monocytes are able to produce MMP-2 and MMP-9 (Fig. 2), in agreement with published data (16, 26, 41). Moreover, MMP-9 production was higher in CD8+ T lymphocytes from the CARD group. Furthermore, the analysis of mononuclear cell contributions to MMP-2 and MMP-9 production showed that CD8+ T lymphocytes were the major mononuclear cell contributors to MMP-2 production in all groups (Fig. 3A) and were also highlighted as cellular contributors to MMP-9 production in patients with Chagas disease (Fig. 3B). The participation of MMPs in immune cell migration has been demonstrated (17), and their production by lymphocytes could be justified, especially because CD8+ T lymphocytes are the main inflammatory-cell source in the heart during Chagas disease (42). Other immune cells, such as neutrophils (16), and many different cell types, including cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells (16, 27), are able to produce and secrete MMP-2 and MMP-9. All of them are found in a myocarditis scenario and are able to contribute to the serum MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels measured in this study and, more importantly, to the MMP-2 and MMP-9 active in the myocardia of patients with Chagas disease.

In this study, we used the 3D cardiomyocyte culture system, which is a new strategy for the study of Chagas disease pathogenesis that shows great similarity to the in vivo studies (22), in order to verify the impact of sera from patients with Chagas disease on cardiac spheroids. The sera from the IND and CARD groups induced overexpression of matrix proteins (Fig. 4), suggesting the existence of different soluble factors that could be able to influence matrix protein expression, since sera from the IND group induced fibronectin and MMP-2 expression whereas sera from the CARD group showed a tendency to induce MMP-9 expression. All matrix proteins are essential for the maintenance of ECM architecture, and their abnormal expression may contribute to pathological processes. The digestion process of matrix proteins by MMPs does not necessarily reduce the quantity of these proteins; on the contrary, it may release growth factors and other molecules capable of inducing the synthesis of additional matrix proteins, increasing the proteins' deposition on the ECM (12). The correlation analysis showed that while MMP-2 had a negative correlation with fibronectin and laminin, MMP-9 showed a positive correlation with both proteins (Fig. 5A). These results led us to hypothesize that MMP-9 may act on the inflammatory process whereas MMP-2 would have an anti-inflammatory effect. MMP-2 has been localized to the nuclei of cardiac cells, where the protein would play a protective role by avoiding apoptosis (31). Furthermore, increased MMP-9 and decreased MMP-2 were associated with left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with hypertension (43). In an experimental arthritis model, MMP-2 and MMP-9 had opposite roles in the progression of arthritis. While MMP-2 had a suppressive role, MMP-9 was associated with the development of inflammatory joint disease (44).

Our data also showed a negative correlation between MMP-2 and the IL-1β and TNF-α cytokines, while MMP-9 showed a positive correlation with these inflammatory cytokines in patients with chronic Chagas disease (Fig. 5B). T. cruzi-infected cardiomyocytes elicit a strong immune response, characterized by the production of IL-1β and TNF-α, which is associated with the hypertrophic effect in these cells (45). Moreover, MMP-9 can cleave and activate these cytokines and thus intensify the process of cardiac remodeling (8, 45, 46).

Heart failure is characterized by activation of different cytokines and enzymes, including MMPs, which have been implicated in the left ventricular remodeling common to different heart failure etiologies (38, 47, 48). Thus, the increased MMP values described by us could be a consequence of the heart failure per se and not a specific change secondary to Chagas disease. However, we also found changes in MMP expression in the group of patients with the indeterminate form versus controls. These patients do not have heart dilation or failure that favors the hypothesis of a specific change in MMP expression contributing to Chagas disease physiopathology.

Overall, the results of the present study indicate that there is differential involvement of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in Chagas disease pathogenesis. We hypothesize that whenever there is a predominance of MMP-9 levels, the cardiac remodeling is intensified and favors the development of the cardiac form of Chagas disease. Conversely, when the MMP-2 levels predominate, the cardiac remodeling is less intense and the patient remains in the indeterminate phase of Chagas disease. Those processes may be IL-1β and TNF-α dependent. These data are innovative and represent an advance in the knowledge of the mechanisms involved in the establishment/maintenance of Chagas heart disease pathology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) (grant 478846/2009-6), the Fundação de Amparo Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG) (grant APQ-02601-10), the Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ), the Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia em Doenças Tropicais (INCT-DT), and the National Institutes of Health.

We thank the staff at the Laboratório de Imunologia Celular e Molecular, FIOCRUZ, for technical assistance. We also thank the Program for Technological Development in Tools for Health (PDTIS), FIOCRUZ, for the use of its facilities. R.C.-O., M.O.C.R., A.T.-C., and J.A.S.G. thank CNPq for fellowships (Bolsa de produtividade em Pesquisa).

We declare that no competing interests exist.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 15 July 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization August 2012. Fact sheet 340. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int Accessed 29 October 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moncayo A, Silveira AC. 2009. Current epidemiological trends for Chagas disease in Latin America and future challenges in epidemiology, surveillance and health policy. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 104(Suppl I):17–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanowitz HB, Machado FS, Jelicks LA, Shirani J, de Carvalho AC, Spray DC, Factor SM, Kirchhoff LV, Weiss LM. 2009. Perspectives on Trypanosoma cruzi-induced heart disease (Chagas disease). Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 51:524–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nunes MP, Colosimo EA, Reis RC, Barbosa MM, da Silva JL, Barbosa F, Botoni FA, Ribeiro AL, Rocha MO. 2012. Different prognostic impact of the tissue Doppler-derived E/e= ratio on mortality in Chagas cardiomyopathy patients with heart failure. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 31:634–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rocha MO, Ribeiro AL, Teixeira MM. 2003. Clinical management of chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy. Front. Biosci. 1:44–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rocha MO, Teixeira MM, Ribeiro AL. 2007. An update on the management of Chagas cardiomyopathy. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 5:727–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geurts N, Opdenakker G, Van den Steen PE. 2012. Matrix metalloproteinases as therapeutic targets in protozoan parasitic infections. Pharmacol. Ther. 133:257–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parks WC, Wilson CL, Lopez-Boado YS. 2004. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:617–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagase H, Visse R, Murphy G. 2006. Structure and function of matrix metalloproteinases and TIMPs. Cardiovasc. Res. 69:562–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu J, Van den Steen PE, Sang QX, Opdenakker G. 2007. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors as therapy for inflammatory and vascular diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6:480–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kupai K, Szucs G, Cseh S, Hajdu I, Csonka C, Csont T, Ferdinandy P. 2010. Matrix metalloproteinase activity assays: importance of zymography. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 61:205–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li YY, McTiernan CF, Feldman AM. 2000. Interplay of matrix metalloproteinases, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases and their regulators in cardiac matrix remodeling. Cardiovasc. Res. 46:214–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanhoutte D, Schellings M, Pinto Y, Heymans S. 2006. Relevance of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors after myocardial infarction: a temporal and spatial window. Cardiovasc. Res. 69:604–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polyakova V, Loeffler I, Hein S, Miyagawa S, Piotrowska I, Dammer S, Risteli J, Schaper J, Kostin S. 2010. Fibrosis in endstage human heart failure: severe changes in collagens metabolism and MMP/TIMP profiles. Int. J. Cardiol. 151:18–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao CQ, Sawicki G, Suarez-Pinzon WL, Csont T, Wozniak M, Ferdinandy P, Schulz R. 2003. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 mediates cytokine-induced myocardial contractile dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Res. 57:426–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Opdenakker G, Van den Steen PE, Van Damme J. 2001. Gelatinase B: a tuner and amplifier of immune functions. Trends Immunol. 22:571–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutierrez FR, Lalu MM, Mariano FS, Milanezi CM, Cena J, Gerlach RF, Santos JE, Torres-Dueñas D, Cunha FQ, Schulz R, Silva JS. 2008. Increased activities of cardiac matrix metalloproteinases matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 are associated with mortality during the acute phase of experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J. Infect. Dis. 197:1468–1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Araújo FF, Corrêa-Oliveira R, Rocha MO, Chaves AT, Fiuza JA, Fares RC, Ferreira KS, Nunes MC, Keesen TS, Damasio MP, Teixeira-Carvalho A, Gomes JA. 2012. Foxp3+CD25(high) CD4+ regulatory T cells from indeterminate patients with Chagas disease can suppress the effector cells and cytokines and reveal altered correlations with disease severity. Immunobiology 217:768–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomes JA, Bahia-Oliveira LMG, Rocha MOC, Correa-Oliveira R. 2003. Evidence that development of severe cardiomyopathy in human Chagas disease is due to a non-balanced Th1 specific immune response. Infect. Immun. 71:1185–1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen QJ, Lu L, Peng WH, Hu J, Yan XX, Wang LJ, Zhang Q, Zhang RY, Shen WF. 2009. Polymorphisms of MMP-3 and TIMP-4 genes affect angiographic coronary plaque progression in non-diabetic and type 2 diabetic patients. Clin. Chim. Acta 405:97–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meirelles MN, de Araujo Jorge TC, Miranda CF, de Souza W, Barbosa HS. 1986. Interaction of Trypanosoma cruzi with heart muscle cells: ultrastructural and cytochemical analysis of endocytic vacuole formation and effect upon myogenesis in vitro. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 41:198–206 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garzoni LR, Adesse D, Soares MJ, Rossi MI, Borojevic R, de Meirelles MN. 2008. Fibrosis and hypertrophy induced by Trypanosoma cruzi in three-dimensional cardiomyocyte-culture system. J. Infect. Dis. 197:906–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adesse D, Lisanti MP, Spray DC, Machado FS, Meirelles MN, Tanowitz HB, Garzoni LR. 2010. Trypanosoma cruzi infection results in the reduced expression of caveolin-3 in the heart. Cell Cycle 9:1639–1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Oliveira FL, Araújo-Jorge TC, de Souza EM, de Oliveira GM, Degrave WM, Feige JJ, Bailly S, Waghabi MC. 2012. Oral administration of GW788388, an inhibitor of transforming growth factor beta signaling, prevents heart fibrosis in Chagas disease. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6:e1696. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Opdenakker G. 2001. New insights in the regulation of leukocytosis and the role played by leukocytes in septic shock. Verh. K. Acad. Geneeskd. Belg. 63:531–538 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vandooren J, Geurts N, Martens E, Van den Steen PE, Opdenakker G. 2013. Zymography methods for visualizing hydrolytic enzymes. Nat. Methods 10:211–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunner S, Kima JO, Methe H. 2010. Relation of matrix metalloproteinase-9/tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 ratio in peripheral circulating CD14+ monocytes to progression of coronary artery disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 105:429–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edsparr K, Basse PH, Goldfarb RH, Albertsson P. 2011. Matrix metalloproteinases in cytotoxic lymphocytes impact on tumour infiltration and immunomodulation. Cancer Microenviron. 4:351–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomes JA, Bahia-Oliveira LM, Rocha MO, Busek SC, Teixeira MM, Silva JS, Correa-Oliveira R. 2005. Type 1 chemokine receptor expression in Chagas' disease correlates with morbidity in cardiac patients. Infect. Immun. 73:7960–7966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Souza PE, Rocha MO, Menezes CA, Coelho JS, Chaves AC, Gollob KJ, Dutra WO. 2007. Trypanosoma cruzi infection induces differential modulation of costimulatory molecules and cytokines by monocytes and T cells from patients with indeterminate and cardiac Chagas' disease. Infect. Immun. 75:1886–1894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mannello F, Medda V. 2012. Nuclear localization of matrix metalloproteinases. Prog. Histochem. Cytochem. 47:27–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lockwood CJ, Oner C, Uz YH, Kayisli UA, Huang SJ, Buchwalder LF, Murk W, Funai EF, Schatz F. 2008. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) expression in preeclamptic decidua and MMP9 induction by tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 1 beta in human first trimester decidual cells. Biol. Reprod. 78:1064–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deschamps AM, Spinale FG. 2006. Pathways of matrix metalloproteinase induction in heart failure: bioactive molecules and transcriptional regulation. Cardiovasc. Res. 69:666–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrade JP, Marin-Neto JA, Paola AA, Vilas-Boas F, Oliveira GM, Bacal F, Bocchi EA, Almeida DR, Fragata Filho AA, Moreira MC, Xavier SS, Oliveira Junior WA, Dias JC. 2011. Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia. Latin American guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of Chagas cardiomyopathy. Chagásica Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 97(Suppl. 3):1–48 (In Portuguese.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menezes C, Costa GC, Gollob KJ, Dutra WO. 2011. Clinical aspects of Chagas disease and implications for novel therapies. Drug Dev. Res. Sep. 72:471–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schulz R. 2007. Intracellular targets of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in cardiac disease: rationale and therapeutic approaches. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 47:211–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adair-Kirk TL, Senior RM. 2008. Fragments of extracellular matrix as mediators of inflammation. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 40:1101–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelly D, Cockerill G, Ng LL, Thompson M, Khan S, Samani NJ, Squire IB. 2007. Plasma matrix metalloproteinase-9 and left ventricular remodelling after acute myocardial infarction in man: a prospective cohort study. Eur. Heart J. 28:711–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomes JA, Campi-Azevedo AC, Teixeira-Carvalho A, Silveira-Lemos D, Vitelli-Avelar D, Sathler-Avelar R, Peruhype-Magalhães V, Silvestre KF, Batista MA, Schachnik NC, Correa-Oliveira R, Eloi-Santos S, Martins-Filho OA. 2012. Impaired phagocytic capacity driven by downregulation of major phagocytosis-related cell surface molecules elicits an overall modulatory cytokine profile in neutrophils and monocytes from the indeterminate clinical form of Chagas disease. Immunobiology 217:1005–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keesen TS, Gomes JA, Fares RC, de Araújo FF, Ferreira KS, Chaves AT, Rocha MO, Correa-Oliveira R. 2012. Characterization of CD4(+) cytotoxic lymphocytes and apoptosis markers induced by Trypanossoma cruzi infection. Scand. J. Immunol. 76:311–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clark RT, Nance JP, Noor S, Wilson EH. 2011. T-cell production of matrix metalloproteinases and inhibition of parasite clearance by TIMP-1 during chronic Toxoplasma infection in the brain. ASN Neuro. 3:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reis DD, Jones EM, Chapadeiro E, Tostes S, Gazzinelli G, Colley DG, McCurley T. 1993. Characterization of inflammatory infiltrates in chronic chagasic myocardial lesions: presence of TNF-alpha and dominance of granzyme A+, CD8+ lymphocytes. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 48:637–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fontana V, Silva PS, Gerlach RF, Tanus-Santos JE. 2012. Circulating matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in hypertension. Clin. Chim. Acta 413:656–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Itoh T, Matsuda H, Tanioka M, Kuwabara K, Itohara S, Suzuki R. 2002. The role of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in antibody-induced arthritis. J. Immunol. 169:2643–2647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manque PA, Probst CM, Pereira MC, Rampazzo RC, Ozaki LS, Pavoni DP, Silva Neto DT, Carvalho MR, Xu P, Serrano MG, Alves JM, Meirelles MN, Goldenberg S, Krieger MA, Buck GA. 2011. Trypanosoma cruzi infection induces a global host cell response in cardiomyocytes. Infect. Immun. 79:1855–1862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aoki MP, Carrera-Silva EA, Cuervo H, Fresno M, Gironès N, Gea S. 2012. Nonimmune cells contribute to crosstalk between immune cells and inflammatory mediators in the innate response to Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J. Parasitol. Res. 2012:737324. 10.1155/2012/737324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spinale FG, Janicki JS, Zile MR. 2013. Membrane-associated matrix proteolysis and heart failure. Circ. Res. 112:195–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsunaga T, Abe N, Kameda K, Hagii J, Fujita N, Onodera H, Kamata T, Ishizaka H, Hanada H, Osanai T, Okumura K. 2005. Circulating level of gelatinase activity predicts ventricular remodeling in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int. J. Cardiol. 105:203–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahmed SH, Clark LL, Pennington WR, Webb CS, Bonnema DD, Leonardi AH, McClure CD, Spinale FG, Zile MR. 2006. Matrix metalloproteinases/tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: relationship between changes in proteolytic determinants of matrix composition and structural, functional, and clinical manifestations of hypertensive heart disease. Circulation 113:2089–2096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]