Abstract

Clostridium perfringens beta-toxin is an important agent of necrotic enteritis and enterotoxemia. Beta-toxin is a pore-forming toxin (PFT) that causes cytotoxicity. Two mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways (p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase [JNK]-like) provide cellular defense against various stresses. To investigate the role of the MAPK pathways in the toxic effect of beta-toxin, we examined cytotoxicity in five cell lines. Beta-toxin induced cytotoxicity in cells in the following order: THP-1 = U937 > HL-60 > BALL-1 = MOLT-4. In THP-1 cells, beta-toxin formed oligomers on lipid rafts in membranes and induced the efflux of K+ from THP-1 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. The phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and JNK occurred in response to an attack by beta-toxin. p38 MAPK (SB203580) and JNK (SP600125) inhibitors enhanced toxin-induced cell death. Incubation in K+-free medium intensified p38 MAPK activation and cell death induced by the toxin, while incubation in K+-high medium prevented those effects. While streptolysin O (SLO) reportedly activates p38 MAPK via reactive oxygen species (ROS), we showed that this pathway did not play a major role in p38 phosphorylation in beta-toxin-treated cells. Therefore, we propose that beta-toxin induces activation of the MAPK pathway to promote host cell survival.

INTRODUCTION

Clostridium perfringens beta-toxin is known to be the primary pathogenic factor of necrotic enteritis and enterotoxemia in type C strains (1, 2). This disease is characterized by an acute sudden onset, severe hemorrhage into the lumen of the small intestine, and early death. Beta-toxin possesses lethal, dermonecrotic, plasma extravasation, and pressor activities (2–6).

Beta-toxin is an essential virulence factor for type C strains (7–9). Beta-toxin bound to intestinal endothelial cells in pigs and a human patient (10, 11). In addition, the toxin was toxic to primary porcine and human endothelial cells (12, 13). Gurtner et al. (12) reported that beta-toxin-induced endothelial damage plays a role in the necrotizing enteritis caused by C. perfringens type C strains.

The deduced amino acid sequence of beta-toxin resembles that of pore-forming toxins, such as Staphylococcus aureus alpha-toxin, leucocidin, and gamma-toxin (2, 14). Shatursky et al. (15) and Tweten (16) reported that the lethal action of C. perfringens beta-toxin was based on the formation of cation-selective pores in susceptible cells. We reported that beta-toxin induced the swelling and lysis of HL-60 cells, and that the toxin formed a functional oligomer of 228 kDa, which was linked to its cytotoxicity, in the lipid rafts of HL-60 cells (17). Steinthorsdottir et al. (18) showed that beta-toxin formed oligomeric complexes on the membranes of human umbilical vein endothelial cells and induced the release of arachidonic acid and inositol from these cells. These characteristics of beta-toxin resemble those of pore-forming toxins (PFT), which suggests that beta-toxin belongs to the same family as alpha-toxin, which forms a functional oligomer in membranes (2, 14). However, little is known about the relationship between the biological activities and oligomer formation of the toxin.

Several studies have reported that p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) is activated as a defense response to different PFTs in several eukaryotic cells (19–23). MAPK signaling is a conserved response to various cell stresses and is essential for survival following toxin-mediated membrane disruption. The proper regulation of MAPK activation is important in order to prevent excessive inflammatory responses that may lead to host tissue damage (24). Ratner et al. (21) reported that low concentrations of bacterial PFTs provided a mechanism for epithelial cells to initiate proinflammatory responses early in infection. In the present study, we showed that beta-toxin induced the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and JNK, and that activation of the MAPK pathway provided cellular defense against the toxin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

The expression and purification of beta-toxin from C. perfringens was carried out as described previously (25). Rabbit anti-beta-toxin antibody was prepared as described previously (26). Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MbCD), lipopolysaccharide (LPS; from Escherichia coli, serotype 0127:B8), and a protease inhibitor mixture were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Mouse anti-caveolin-1 and anti-β-actin antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit anti-phospho-p38 MAPK, anti-p38 MAPK, anti-phospho-JNK, and anti-JNK antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG), horseradish peroxidase-labeled sheep anti-mouse IgG, and an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western blotting kit were purchased from GE Healthcare (Tokyo, Japan). SB203580, SP600125, and N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) were purchased from Wako Pure Chem (Osaka, Japan). RPMI 1640 medium (RPMI) and Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) were obtained from Gibco BRL (New York, NY).

Cell culture.

THP-1 is a human monocytic cell line derived from an acute monocytic leukemia patient. HL-60 is a predominantly neutrophilic promyelocyte (precursor) cell line derived from an acute promyelocytic leukemia patient. U937 is a human macrophage-like cell line derived from a histiocytic lymphoma patient. BALL-1 is a human B-cell line derived from an acute lymphoblastic leukemia patient. MOLT-4 is a human leukemic T-cell line derived from an acute lymphoblastic leukemia patient. THP-1, HL-60, MOLT-4, and BALL-1 were obtained from Riken Cell Bank (Tsukuba, Japan). U937 was purchased from JCRB Cell Bank (Osaka, Japan). They were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 2 mM glutamine (FCS-DMEM). All incubation steps were carried out at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. K+-normal medium refers to Hanks buffer (140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.36 mM K2HPO4, 0.44 mM KH2PO4, 5.5 mM d-glucose, 4.2 mM NaHCO3), and the K+-high medium was identical with the exception of the NaCl (5 mM) and KCl concentrations (140 mM). In K+-free medium, KCl was replaced with NaCl.

Cell viability.

Cell viability was determined by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (Promega) inner salt conversion assay (MTS assay). Absorbance was read at 490 nm using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plate reader. Cell viability was calculated as the mean absorbance of the toxin group divided by that of the control (17, 27). In some experiments, heat-inactivated beta-toxin was prepared by heating at 95°C for 10 min.

Measurement of K+ flux.

THP-1 cells (1 × 106 cells/ml) were inoculated in 6-well plates in HBSS. Cells were incubated with the toxin at 37°C for various times for the K+ efflux assay. K+ concentrations in the supernatants were determined at the given times with an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Hitachi Z-8200; Tokyo, Japan) as described previously (17, 28).

Sucrose gradient fractionation.

The separation of lipid rafts was carried out by flotation-centrifugation on a sucrose gradient (27, 29). THP-1 cells were incubated in fresh medium containing beta-toxin at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were rinsed with HBSS, left untreated or treated with 1% Triton X-100 for 30 min at 4°C in HBSS containing the protease inhibitor mixture, and then sonicated with 20-s pulses (two and six times, respectively) using a tip-type sonicator. The lysates were adjusted to 40% (wt/vol) sucrose, overlaid with 2.4 ml of 36% sucrose and 1.2 ml of 5% sucrose in HBSS, centrifuged at 45,000 rpm (250,000 × g) for 18 h at 4°C in a SW55 rotor (Beckman Instruments, Palo Alto, CA), and fractionated from the top (0.4 ml each; total of 10 fractions). The aliquots were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using the anti-beta-toxin antibody. Cholesterol contents were assayed spectrophotometrically using a diagnostic kit (cholesterol C-test; Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan) (17).

Immunoblot analysis.

Immunoblotting was carried out as described previously (29). The protein concentration of the samples was determined by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Each cell lysate containing 20 μg of protein was heated in 2% SDS sample buffer at 95°C for 3 min, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon P; Millipore). The membrane was blocked with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 2% Tween 20 and 5% skim milk. It was incubated first with the primary antibody in TBS containing 1% skim milk and then with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, and finally the membrane was subjected to analysis by using an enhanced chemiluminescence analysis kit (GE Healthcare).

Measurement of ROS.

Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production was measured using the cell-permeable probe 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) (Sigma). DCFH-DA penetrates the cells and is hydrolyzed by intracellular esterases to nonfluorescent DCFH, which can be rapidly oxidized to highly fluorescent 2,7-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) in the presence of ROS. THP-1 monocytes were inoculated into six-well plates; the number of cells was 2 × 105 cells/well. After the loading of cells with substrate (10 min at 37°C with DCF at 10 μM final concentration), cells were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and beta-toxin was added to yield a final concentration of 5 μg/ml. Incubation was continued for 30 min. LPS (1 μg/ml) served as a positive control. Cells were washed and suspended in PBS. Fluorescence in the fluorescein channel was recorded by flow cytometry with a FACScan instrument (Beckman Coulter, Japan).

RESULTS

Cytotoxicity of beta-toxin.

We reported that beta-toxin induced the swelling and lysis of HL-60 cells (17). To investigate the cytotoxicity of beta-toxin, the MTS assay was performed with five immune cell lines, including myelocytic and monocytic leukemia cells as well as leukemic T and B cells (Fig. 1A). Five human cell lines were confirmed to be sensitive to the toxin to various degrees. The results indicated that BALL-1 and MOLT-4 cells have low beta-toxin sensitivity, HL-60 cells have intermediate sensitivity, and U937 and THP-1 cells are highly sensitive. The cytotoxicity of the toxin was in the following order: THP-1 = U937 > HL-60 > MOLT-4 = BALL-1.

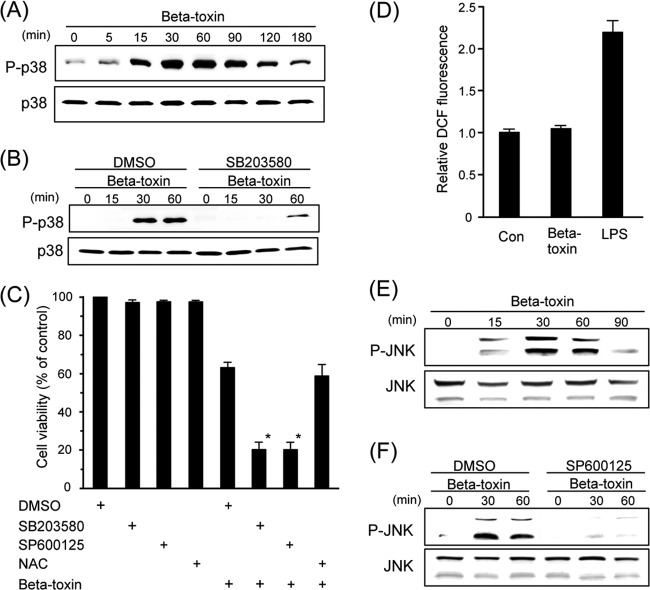

Fig 1.

Cytotoxicity and oligomer formation of beta-toxin. (A) The cytotoxicity of beta-toxin on various cells. Cells were treated with various amounts of beta-toxin at 37°C for 4 h. Cell viability was determined via an assay with MTS, and the number of live cells is shown as a percentage of the value for untreated controls (means ± standard deviations [SD] from four independent experiments). (B) Oligomer formation of beta-toxin on various cells. Cells were incubated with beta-toxin (5 μg/ml) at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were rinsed and subjected to Western blot analysis of beta-toxin and β-actin (control). A typical result from one of three experiments is shown. (C) Oligomer formation of beta-toxin in the lipid rafts of THP-1 cells. THP-1 cells were incubated with beta-toxin (5 μg/ml) at 37°C for 30 min. Triton X-100-insoluble cell extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE as described in Materials and Methods. Fractions containing lipid rafts were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using the anti-caveolin-1 antibody. A typical result from one of three experiments is shown.

Binding of beta-toxin to cells.

To compare the binding and oligomer formation of beta-toxin with five immune cells, the toxin was incubated with various cells (5 × 105 cells) in RPMI-10% FCS at 37°C for 30 min. Treated cells were dissolved in SDS-sample solution and analyzed by SDS-7.5% PAGE without heating. Beta-toxin was analyzed by Western blotting with the anti-beta-toxin antibody (Fig. 1B). Beta-toxin formed oligomers with molecular masses of 191 and 228 kDa (corresponding to the size of hexameric and heptameric structures) as described previously (17). THP-1 and U937 cells bound more beta-toxin and formed more oligomer. HL-60 cells bound the same amount of beta-toxin as THP-1 and U937 cells and more of this toxin than MOLT-4 or BALL-1 cells. The rank order of binding of the beta-toxin oligomer directly correlated with the rank order of cytotoxicity caused by the toxin.

We reported that beta-toxin acted on HL-60 cells by binding to lipid rafts and forming a functional oligomer (17). To investigate the binding of beta-toxin to the lipid rafts of THP-1 cells, beta-toxin was incubated with THP-1 cells in RPMI-10% FCS at 37°C for 30 min, and cells were treated with 1% Triton X-100 at 4°C for 60 min. Membranes treated with Triton X-100 were fractionated by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. Fractions were dissolved in SDS-sample solution without heating and subjected to Western blotting of beta-toxin. As shown in Fig. 1C, the oligomer of beta-toxin was detected in the detergent-insoluble fractions. Caveolin-1 was detected in the insoluble fractions (fractions 3 to 5) (Fig. 1C) in which >85% of the cholesterol was detected (data not shown), which indicated that fractions 3 to 5 were lipid rafts. No oligomer of the toxin was detected when the heat-inactivated toxin was incubated with THP-1 cells at 37°C for 30 min (data not shown). Incubating cells with 10 mM MbCD, an efficient drug that extracts cholesterol from membranes, caused a reduction in toxin-induced cell death (data not shown). These results indicated that beta-toxin strongly causes cell death in THP-1 cells via oligomer formation in the lipid rafts of the cells.

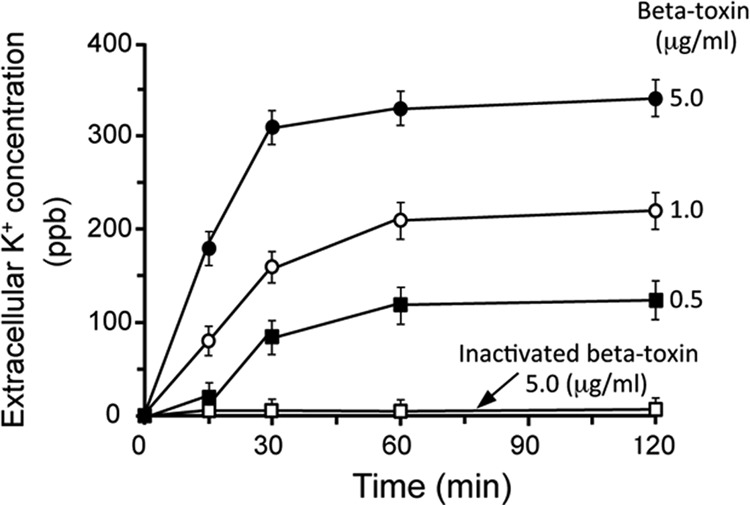

K+ release from THP-1 cells by beta-toxin.

We reported that beta-toxin induced the release of K+ from HL-60 cells (17). Potassium leakage by other PFTs was shown to trigger subsequent events, such as the activation of a variety of signaling cascades, including MEK, p38 MAPK, and caspase-1 (30). To investigate whether beta-toxin affected the membrane permeability of THP-1 cells, we measured the efflux of K+ from these cells. As shown in Fig. 2, beta-toxin at concentrations from 0.5 to 5.0 μg/ml induced the release of K+ from cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. The release of K+ was not evoked by heat-inactivated beta-toxin.

Fig 2.

Effect of beta-toxin on K+ release from THP-1 cells. Beta-toxin-induced K+ release from THP-1 cells. THP-1 cells were incubated with beta-toxin at 37°C. K+ concentrations in the medium were determined at given times by atomic absorption spectrometry. Data are the means ± SD from four independent experiments.

Incubation of the cells in the absence of beta-toxin at 37°C or in the presence of beta-toxin at 4°C induced no release of K+ (data not shown). When the toxin was preincubated with anti-beta-toxin antibody for 30 min at room temperature, K+ release induced by beta-toxin was neutralized by the anti-beta-toxin antibody (data not shown).

Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK by beta-toxin.

The p38 MAPK pathway was shown to play a crucial role in triggering defense responses to several PFTs in different eukaryotic cells, and the loss of intracellular potassium was required for p38 MAPK activation by other PFTs (24). To test whether the treatment of THP-1 cells with beta-toxin induced the activation of p38 MAPK, cells were incubated with it at 37°C for the indicated periods. The treated cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-phospho-p38 MAPK (Fig. 3A). The phosphorylation of p38 MAPK reached a maximum within 60 min under the conditions used. No phosphorylation of p38 MAPK was evoked by heat-inactivated beta-toxin and mock treatment (data not shown). This result indicated that incubation of the cells with beta-toxin resulted in the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK.

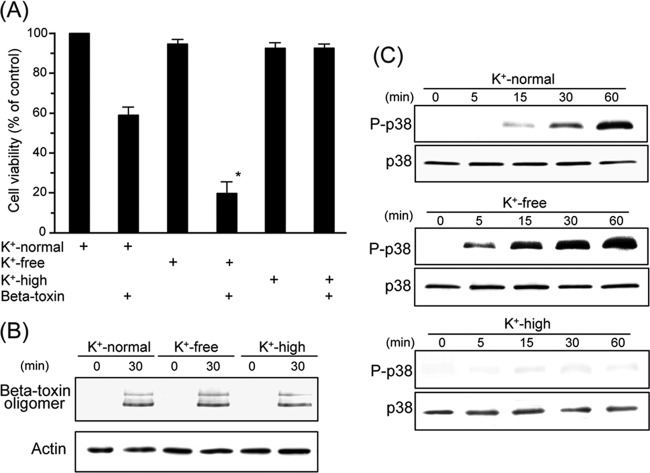

Fig 3.

Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and JNK in THP-1 cells treated with beta-toxin. (A and E) THP-1 cells were incubated with beta-toxin (0.5 μg/ml) for the indicated time periods. P-p38 and P-JNK, phosphorylated p38 MAPK and JNK, respectively. (B and F) THP-1 cells treated with DMSO, 10 μM SB203580 (B), or 10 μM SP600125 (F) at 37°C for 60 min were incubated with beta-toxin (0.5 μg/ml) for the indicated time periods. Cells were subsequently lysed and detected by Western blotting using specific antibodies. Typical results from one of four experiments are shown. (C) THP-1 cells treated with DMSO, 10 μM SB203580, 10 μM SP600125, or 2.5 mM NAC at 37°C for 60 min were treated with beta-toxin (0.5 μg/ml) at 37°C for 4 h. Cell viability was determined via an assay with MTS. Data are reported as percentages of the values obtained with untreated controls (means ± SD from four independent experiments). Significant differences (Student t test) from control cells are indicated. An asterisk indicates P < 0.01, which is significantly different from DMSO plus beta-toxin. (D) THP-1 cells were treated with beta-toxin (5 μg/ml) or with LPS (1 μg/ml) at 37°C for 30 min. Intracellular ROS levels were then determined by flow-cytometric analysis of DCF fluorescence as described in Materials and Methods. Data are the means ± SD from four independent experiments. Con, control.

We then examined the effects of an inhibitor of p38 MAPK on the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK induced by beta-toxin. The p38 MAPK-specific inhibitor SB203580 inhibited the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK induced by beta-toxin (Fig. 3B). Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) alone or SB203580 alone did not induce the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK (data not shown). MAPK pathways have been shown to protect mammalian cells against PFTs. To examine whether activation of the p38 MAPK pathway contributed to beta-toxin-induced cell death, we pretreated THP-1 cells with the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (Fig. 3C). Beta-toxin-induced cell death was significantly higher with the addition of SB203580 than with DMSO plus beta-toxin. The cytotoxicity of beta-toxin alone was similar to that of DMSO plus the toxin (data not shown). Treatment of THP-1 cells with beta-toxin in the presence of SB203580 had no effect on the binding and oligomerization of beta-toxin to cells (data not shown). The results described above indicate that activation of the p38 MAPK pathway is caused by stress responses and is not required for beta-toxin-induced cell death.

The generation of ROS was shown to induce the activation of p38 MAPK (20). We examined whether ROS was involved in p38 MAPK activation by beta-toxin. As shown in Fig. 3D, ROS production could not be detected in beta-toxin-treated THP-1 cells. As a positive control, ROS production was detected when THP-1 cells were incubated with LPS. NAC, an ROS scavenger, did not affect the cytotoxicity of beta-toxin (Fig. 3C).

Phosphorylation of JNK by beta-toxin.

The JNK pathway is activated in stress response to PFTs, UV irradiation, cadmium, and DNA damaging agents (24). Treatment of THP-1 cells with beta-toxin led to the phosphorylation of JNK (Fig. 3E). No phosphorylation of JNK was evoked by heat-inactivated beta-toxin and mock treatment (data not shown). The JNK-specific inhibitor SP600125 inhibited the phosphorylation of JNK induced by beta-toxin (Fig. 3F). Furthermore, SP600125 significantly increased cell death induced by beta-toxin (Fig. 3C). SP600125 alone did not induced the phosphorylation of JNK (data not shown). Treatment of THP-1 cells with beta-toxin in the presence of SP600125 had no effect on the binding and oligomerization of beta-toxin to cells (data not shown).

Effect of K+ concentration on the medium.

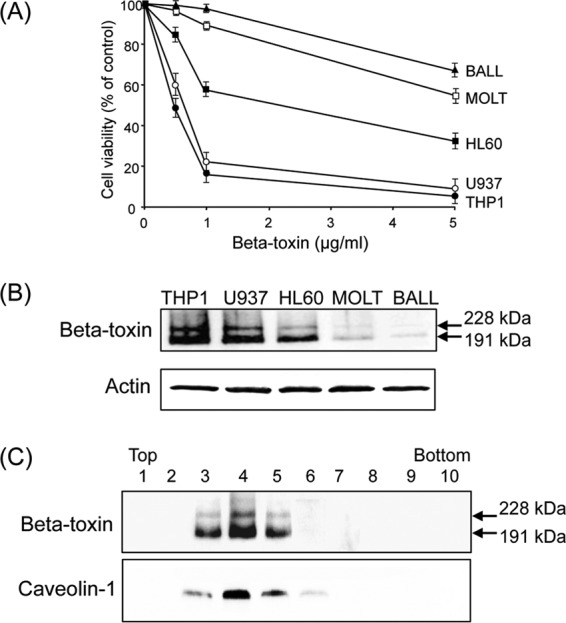

The phosphorylation of p38 MAPK induced by PFT was shown to be influenced by potassium levels in the medium (24, 30). We investigated the effect of K+ concentrations on beta-toxin-induced cytotoxicity. THP-1 cells were incubated with K+-normal, K+-free, or K+-high medium (Fig. 4A). Cytotoxicity induced by the toxin was stronger with K+-free medium than with K+-normal medium. On the other hand, K+-high medium prevented toxin-induced cytotoxicity. To test the binding and oligomerization of beta-toxin on THP-1 cells, cells were incubated with beta-toxin in media containing various K+ concentrations at 37°C for 30 min. The treated cells were dissolved in SDS-sample buffer without heating and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Beta-toxin was detected by Western blotting with the anti-beta-toxin antibody (Fig. 4B). When THP-1 cells were incubated with beta-toxin in K+-normal, K+-free, or K+-high medium, the oligomer of beta-toxin was detected at equal levels. We then evaluated the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in cells treated with beta-toxin under various K+ concentrations (Fig. 4C). With beta-toxin present, the level of p38 MAPK phosphorylation was more intense in K+-free medium than in K+-normal medium. On the other hand, K+-high medium blocked the activation of p38 MAPK by beta-toxin.

Fig 4.

Effect of extracellular potassium levels on cytotoxicity, p38 MAPK phosphorylation, and binding of the toxin in THP-1 cells treated with beta-toxin. (A) THP-1 cells were incubated either in K+-normal, K+-free, or K+-high medium with beta-toxin (0.5 μg/ml) at 37°C. After incubation for 4 h, cell viability was determined via an assay with MTS. Data are reported as percentages of the values obtained with untreated controls (means ± SD from four independent experiments). Significant differences (Student's t test) from control cells are indicated. An asterisk indicates P < 0.01, significantly different from K+-normal medium plus beta-toxin. (B) THP-1 cells were incubated with beta-toxin (1 μg/ml) at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were subsequently lysed, and beta-toxin and β-actin (control) were detected by Western blotting using specific antibodies. A typical result from one of three experiments is shown. (C) After incubation with beta-toxin (0.5 μg/ml) for the indicated time periods, cells were subsequently lysed, and phosphorylated p38 MAPK and p38 MAPK were detected by Western blotting using specific antibodies. Typical results from one of four experiments are shown.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrated that beta-toxin (i) exhibited cytotoxicity in THP-1 cells, (ii) bound to lipid rafts and formed an oligomer, and (iii) caused activation of the p38 MAPK pathway. Our results indicated that the activation of p38 MAPK induced by the toxin is a stress response for survival rather than a direct contribution to beta-toxin-induced cell death.

We reported that beta-toxin induced the swelling and lysis of HL-60 cells (17). In this study, beta-toxin killed five human hematopoietic tumor cell lines (THP-1, U937, HL-60, BALL-1, and MOLT-4). THP-1 and U937 were more sensitive to beta-toxin than HL-60. We demonstrated that beta-toxin bound preferentially to sensitive cells. Our study indicates that beta-toxin attacks the immune cells.

PFTs induce a decrease in cellular potassium levels. This in turn activates various signaling cascades (24, 30). Kloft et al. (22) also reported that PFTs trigger the p38 MAPK pathway by causing the loss of cellular K+. We reported previously that beta-toxin induced the release of K+ from HL-60 cells (17). In the present study, beta-toxin caused the release of K+ from THP-1 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. The toxin formed a functional oligomer on HL-60 cells, which is linked to its cytotoxicity, in lipid rafts of the membranes (17). These results imply that toxin-induced K+ release is induced through pores formed by the toxin in the lipid rafts of THP-1 cells.

The treatment of THP-1 cells with beta-toxin led to the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK. The addition of the chemical inhibitor of p38 MAPK activity, SB203580, significantly increased beta-toxin-induced cell death. These results indicated that activation of the p38 MAPK pathway by beta-toxin is caused by stress responses and is not required for toxin-induced cytotoxicity. It has previously been reported that ROS generation is responsible for the phosphorylation and activation of p38 MAPK (20). However, beta-toxin did not produce ROS, and NAC, a potent antioxidant, did not affect toxin-induced cytotoxicity. Therefore, the release of K+ from cells induced by beta-toxin is sufficient to activate p38 MAPK. Intracellular K+ depletion seems to be a key event controlling this activation.

Previous studies have shown that high extracellular K+ levels prevented PFT-induced p38 MAPK activation and cell death (22, 24, 31). We observed that beta-toxin did not lead to cell death or the activation of p38 MAPK in THP-1 cells in K+-high medium, which indicated that K+ efflux through the toxin pore activates the p38 MAPK defense response. On the other hand, when cells were incubated in K+-free medium, cell death and p38 MAPK activation caused by beta-toxin were increased. These results reveal that K+ efflux by beta-toxin contributes to p38 MAPK activation. These results also confirm the crucial role of K+ concentrations in regulating the activation of p38 MAPK and cell death in THP-1 cells. How K+ efflux elicited by beta-toxin contributes to the activation of the MAPK pathway warrants further studies.

Similar to p38 MAPK, the JNK pathway is important for the innate immune response in mammals. The JNK pathway was shown to have broader functions than the p38 MAPK pathway responding to various stress agents (24). Beta-toxin leads to the phosphorylation of JNK. The JNK inhibitor SP600125 inhibited the phosphorylation of JNK by the toxin and increased toxin-induced cell death. We found that a second MAPK pathway is also required for protection against beta-toxin. The role of both the p38 MAPK and JNK pathways in protecting against beta-toxin is unknown. The function of one pathway may be to activate the other, although we found no evidence of this. Alternatively, it is possible that the two pathways act independently to promote protection against beta-toxin.

MAPK families are considered to be stress-activated protein kinases controlling host defense systems involved in the recovery of plasma membrane integrity, cell survival, and adaptation (24). PFTs lead to cell cytolysis. Epithelial cells were shown to detect the osmotic stress associated with sublytic concentrations of PFTs and initiate immune responses through the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK (21). The detection of sublytic, nanomolar concentrations of bacterial PFTs may provide a mechanism for epithelial cells to initiate proinflammatory responses early in infection when the bacterial density is still low (24). These observations have implications for our understanding of immune responses to pathogens at the mucosal surface. Pathways that sense cell stress may represent a novel arm of the mucosal innate immune response. In the present study, we found that beta-toxin induced activation of the MAPK pathway in human THP-1 monocytes. Therefore, we propose a novel defense mechanism for beta-toxin in the host immune system. Our finding of cross talk between the mechanisms of pathogen recognition and epithelial osmosensing is a novel observation. MAPK signaling is a conserved response to various cell stresses and is essential for survival following toxin-mediated membrane disruption. Further investigations are required to delineate the molecular defense mechanisms of p38 MAPK activation by beta-toxin.

In conclusion, K+ efflux by beta-toxin in THP-1 cells induced the activation of p38 MAPK and JNK. This activation was not essential for beta-toxin-induced cell death; rather, it was a stress response to the toxin for cell survival. Our studies indicate that the MAPK pathway is activated in THP-1 cells to protect the cells against beta-toxin.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, MEXT.SENRYAKU, 2012.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 July 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Songer JG. 1996. Clostridial enteric diseases of domestic animals. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:216–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakurai J, Nagahama M. 2006. Clostridium perfringens beta-toxin: characterization and action. Toxin Rev. 25:89–108 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakurai J, Fujii Y, Matsuura M. 1980. Effect of oxidizing agents and sulfhydryl group reagents on beta toxin from Clostridium perfringens type C. Microbiol. Immunol. 24:595–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakurai J, Fujii Y, Dezaki K, Endo K. 1984. Effect of Clostridium perfringens beta toxin on blood pressure of rats. Microbiol. Immunol. 28:23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagahama M, Morimitsu S, Kihara A, Akita M, Setsu K, Sakurai J. 2003. Involvement of tachykinin receptors in Clostridium perfringens beta-toxin-induced plasma extravasation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 138:23–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagahama M, Kihara A, Kintoh H, Oda M, Sakurai J. 2008. Involvement of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in Clostridium perfringens beta-toxin-induced plasma extravasation in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 153:1296–1302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sayeed S, Uzal FA, Fisher DJ, Saputo J, Vidal JE, Chen Y, Gupta P, Rood JI, McClane BA. 2008. Beta toxin is essential for the intestinal virulence of Clostridium perfringens type C disease isolate CN3685 in a rabbit ileal loop model. Mol. Microbiol. 67:15–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vidal JE, McClane BA, Saputo J, Parker J, Uzal FA. 2008. Effects of Clostridium perfringens beta-toxin on the rabbit small intestine and colon. Infect. Immun. 76:4396–4404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vidal JE, Ma M, Saputo J, Garcia J, Uzal FA, McClane BA. 2012. Evidence that the Agr-like quorum sensing system regulates the toxin production, cytotoxicity and pathogenicity of Clostridium perfringens type C isolate CN3685. Mol. Microbiol. 83:179–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miclard J, Jäggi Sutter ME, Wyder M, Grabscheid B, Posthaus H. 2009. Clostridium perfringens beta-toxin targets endothelial cells in necrotizing enteritis in piglets. Vet. Microbiol. 137:320–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miclard J, van Baarlen J, Wyder M, Grabscheid B, Posthaus H. 2009. Clostridium perfringens beta-toxin binding to vascular endothelial cells in a human case of enteritis necroticans. J. Med. Microbiol. 58:826–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gurtner C, Popescu F, Wyder M, Sutter E, Zeeh F, Frey J, von Schubert C, Posthaus H. 2010. Rapid cytopathic effects of Clostridium perfringens beta-toxin on porcine endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 78:2966–2973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Popescu F, Wyder M, Gurtner C, Frey J, Cooke RA, Greenhill AR, Posthaus H. 2011. Susceptibility of primary human endothelial cells to C. perfringens beta-toxin suggesting similar pathogenesis in human and porcine necrotizing enteritis. Vet. Microbiol. 153:173–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunter SE, Brown JE, Oyston PC, Sakurai J, Titball RW. 1993. Molecular genetic analysis of beta-toxin of Clostridium perfringens reveals sequence homology with alpha-toxin, gamma-toxin, and leukocidin of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 61:3958–3965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shatursky O, Bayles R, Rogers M, Jost BH, Songer JG, Tweten RK. 2000. Clostridium perfringens beta-toxin forms potential-dependent, cation-selective channels in lipid bilayers. Infect. Immun. 68:5546–5551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tweten RK. 2001. Clostridium perfringens beta-toxin and Clostridium septicum alpha-toxin: their mechanisms and possible role in pathogenesis. Vet. Microbiol. 82:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagahama M, Hayashi S, Morimitsu S, Sakurai J. 2003. Biological activities and pore formation of Clostridium perfringens beta-toxin in HL 60 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278:36934–36941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinthorsdottir V, Halldórsson H, Andrésson OS. 2000. Clostridium perfringens beta-toxin forms multimeric transmembrane pores in human endothelial cells. Microb. Pathog. 28:45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huffman DL, Abrami L, Sasik R, Corbeil J, van der Goot FG, Aroian RV. 2004. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways defend against bacterial pore-forming toxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:10995–11000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Husmann M, Dersch K, Bobkiewicz W, Beckmann E, Veerachato G, Bhakdi S. 2006. Differential role of p38 mitogen activated protein kinase for cellular recovery from attack by pore-forming S. aureus alpha-toxin or streptolysin O. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 344:1128–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratner AJ, Hippe KR, Aguilar JL, Bender MH, Nelson AL, Weiser JN. 2006. Epithelial cells are sensitive detectors of bacterial pore-forming toxins. J. Biol. Chem. 281:12994–12998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kloft N, Busch T, Neukirch C, Weis S, Boukhallouk F, Bobkiewicz W, Cibis I, Bhakdi S, Husmann M. 2009. Pore-forming toxins activate MAPK p38 by causing loss of cellular potassium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 385:503–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bebien M, Hensler ME, Davanture S, Hsu LC, Karin M, Park JM, Alexopoulou L, Liu GY, Nizet V, Lawrence T. 2012. The pore-forming toxin β hemolysin/cytolysin triggers p38 MAPK-dependent IL-10 production in macrophages and inhibits innate immunity. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002812. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porta H, Cancino-Rodezno A, Soberón M, Bravo A. 2011. Role of MAPK p38 in the cellular responses to pore-forming toxins. Peptides 32:601–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakurai J, Fujii Y. 1987. Purification and characterization of Clostridium perfringens beta toxin. Toxicon 25:1301–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakurai J, Fujii Y, Matsuura M, Endo K. 1981. Pharmacological effect of beta toxin of Clostridium perfringens type C on rats. Microbiol. Immunol. 25:423–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagahama M, Umezaki M, Oda M, Kobayashi K, Tone S, Suda T, Ishidoh K, Sakurai J. 2011. Clostridium perfringens iota-toxin b induces rapid cell necrosis. Infect. Immun. 79:4353–4360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagahama M, Nagayasu K, Kobayashi K, Sakurai J. 2002. Binding component of Clostridium perfringens iota-toxin induces endocytosis in Vero cells. Infect. Immun. 70:1909–1914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagahama M, Hagiyama T, Kojima T, Aoyanagi K, Takahashi C, Oda M, Sakaguchi Y, Oguma K, Sakurai J. 2009. Binding and internalization of Clostridium botulinum C2 toxin. Infect. Immun. 77:5139–5148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzalez MR, Bischofberger M, Frêche B, Ho S, Parton RG, van der Goot FG. 2011. Pore-forming toxins induce multiple cellular responses promoting survival. Cell. Microbiol. 13:1026–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imre G, Heering J, Takeda AN, Husmann M, Thiede B, zu Heringdorf DM, Green DR, van der Goot FG, Sinha B, Dötsch V, Rajalingam K. 2012. Caspase-2 is an initiator caspase responsible for pore-forming toxin-mediated apoptosis. EMBO J. 31:2615–2628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]