Abstract

Background

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an uncommon type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma with poor overall prognosis, requiring the development of new therapies. Lenalidomide is an immunomodulatory agent demonstrating antitumor and antiproliferative effects in MCL. We report results from a long-term subset analysis of 57 patients with relapsed/refractory MCL from the NHL-003 phase II multicenter study of single-agent lenalidomide in patients with aggressive lymphoma

Design

Lenalidomide was administered orally 25 mg daily on days 1–21 every 28 days until progressive disease (PD) or intolerability. The primary end point was overall response rate (ORR).

Results

Fifty-seven patients with relapsed/refractory, advanced-stage MCL had a median of three prior therapies. The ORR was 35% [complete response (CR)/CR unconfirmed (CRu) 12%], with a median duration of response (DOR) of 16.3 months (not yet reached in patients with CR/CRu) by blinded independent central review. The median time to first response was 1.9 months. Median progression-free survival was 8.8 months, and overall survival had not yet been reached. The most common grade 3/4 adverse events (AEs) were neutropenia (46%), thrombocytopenia (30%), and anemia (13%).

Conclusions

These results show the activity of lenalidomide in heavily pretreated, relapsed/refractory MCL. Responders had a durable response with manageable side-effects. Clinical trial number posted on www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT00413036.

Keywords: lenalidomide, mantle cell lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma

introduction

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an uncommon type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) comprising <10% of all newly diagnosed patients [1, 2]. Classified as an aggressive NHL subtype, MCL has the worst prognosis of B-cell subtypes owing to its aggressive clinical disease course and incurability with standard chemotherapy. Conventional first-line therapy for bulky or advanced disease primarily consists of chemotherapy combined with rituximab, with possible consolidation with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) for younger patients in remission to improve overall patient outcomes. However, options for relapsed MCL are limited although several single agents have been studied. Bortezomib and temsirolimus first received regulatory approval for relapsed/refractory MCL, demonstrating overall response rates (ORRs) of 22%–41% (temsirolimus) and 32% (bortezomib), although their durations of response (DOR, ≤9.2 months) were relatively short and treatment-related toxicity was challenging for some patients [3–5]. Tolerable therapies that prolong remission and improve survival are greatly needed for patients with relapsing MCL, particularly for those receiving multiple prior therapies.

Lenalidomide (Revlimid®; Celgene Corporation, Summit, NJ) is an immunomodulatory agent initially studied in multiple myeloma and myelodysplastic syndromes [6], with antitumor and antiproliferative preclinical activities in MCL [7–9]. Clinical activity was previously reported in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory NHL in two separate studies, NHL-002 [10] and NHL-003 [11]. Heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory MCL (median four prior therapies) from the NHL-002 study showed an ORR of 53% [20% complete response (CR)], a median DOR of 13.7 months, and a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 5.6 months following 12 or less cycles of lenalidomide by investigator assessments [10, 12]. Patients responded despite prior therapy; hematologic grade 3/4 adverse events (AEs) were the most common with no cases of tumor lysis syndrome (TLS). The current report is a subset analysis of MCL patients from the larger NHL-003 clinical trial [11], reporting long-term outcomes and using more rigorous blinded central review of efficacy data. These results confirm consistent activity and safety of lenalidomide with durable responses in heavily pretreated, relapsed/refractory MCL patients.

patients and methods

Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee approved the study at each institution in accordance with local rules and regulations. Study sites reviewed protocol and patient-provided informed consent before study initiation. Ethical requirements were met as per the International Conference on Harmonization, Title 21 of the US Code of Federal Regulations, and Declaration of Helsinki.

study design

The single-arm, multicenter, phase II NHL-003 trial (NCT00413036) examined the safety and efficacy of lenalidomide in relapsed/refractory aggressive NHL. Lenalidomide 25 mg was self-administered orally on days 1–21 of each 28-day cycle until progressive disease (PD) or intolerability. Patients terminating treatment by choice or due to toxicity were monitored until PD or initiation of another lymphoma treatment. Safety data were monitored by an internal data monitoring committee throughout the study.

patients

Patients were ≥18 years old with a biopsy-proven lymphoma that had relapsed after or was refractory to one or more prior chemotherapy. Patients had to have measurable disease of ≥2 cm by computed tomography scan, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) 0–2, creatinine clearance ≥50 ml/min, absolute neutrophil count ≥1500 cells/mm3, platelets ≥60 000/mm3, and adequate organ function. Detailed eligibility criteria were previously described [11].

assessments and statistical analyses

The primary end point was ORR; secondary end points included CR, CR unconfirmed (CRu), partial response (PR), DOR (all patients and CR/CRu only), PFS, time to first response (TTFR), and safety. Tumor response was evaluated as per the 1999 International Workshop Lymphoma Response Criteria (IWLRC) [13]. ORR was calculated with two-sided 95% confidence intervals. Response durations and survival were analyzed by Kaplan–Meier estimates. AEs were categorized by NCI CTCAE, version 3.0.

Along with site-specific investigator assessments, an independent review committee (i.e. central review) with no affiliation to the study sponsor examined blinded tumor response data for impartial and independent efficacy assessments in two sequential components. First, two radiologists conducted radiology review by separately assessing each individual's image data sequentially by time point, which was reviewed twice. A third radiologist was consulted as needed. Second, an oncologist conducted the clinical data review and radiologic assessment for overall clinical findings including best overall response, date of response, and/or date of progression according to IWLRC [13].

results

patient demographics

Fifty-seven of 217 patients enrolled in the NHL-003 study had MCL and were evaluated from October 2006 through an April 2011 data cut-off) [11]. MCL patients had a median age of 68 years, and 77% were males (Table 1). Patients had previously received a median of three prior therapies, including 35% refractory to their last therapy and 25% who had prior ASCT. The most common prior anticancer therapies for MCL patients (single-agent or in combination) were rituximab (97%), cyclophosphamide (93%), vincristine (90%), doxorubicin (84%), prednisone (65%), etoposide (42%), cytarabine (35%), and bortezomib (32%).

Table 1.

Demographics and patient characteristics at study entry for patients with relapsed/refractory MCL

| Characteristic | Patients (n = 57) |

|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 68 (33–82) |

| ≥65 years, n (%) | 36 (63) |

| Males, n (%) | 44 (77) |

| Median time from diagnosis to first dose of lenalidomide, years (range) | 3.9 (0.6–10.7) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |

| 0 | 27 (47) |

| 1 | 24 (42) |

| 2 | 6 (11) |

| NHL stage at baselinea, n (%) | |

| II | 6 (11) |

| III | 11 (19) |

| IV | 39 (68) |

| MIPI risk at enrollment, n (%) | |

| Low | 29 (51) |

| Intermediate | 17 (30) |

| High | 11 (19) |

| Median prior treatment regimens, n (range) | 3 (1–13) |

| Refractory to last therapy, n (%) | 20 (35) |

| Refractory to last prior chemotherapy, n (%) | 17 (30) |

| Most common types of prior treatment regimen, n (%) | |

| Rituximab single agent or in combination with chemotherapy | 55 (97) |

| Rituximab in combination with chemotherapy | 54 (95) |

| R-CHOP | 27 (47) |

| Rituximab single agent | 22 (39) |

| Cytarabine single agent or in combination | 20 (35) |

| Bortezomib single agent or in combination | 18 (32) |

| ASCT | 14 (25) |

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MIPI, MCL International Prognostic Index; R, rituximab.

aOne patient was missing NHL staging.

efficacy

Efficacy was measured by local investigators and central reviewers for all patients (Table 2). ORR by central review was 35% (95% CI, 23–49%), with a 12% CR/CRu (95% CI, 5–24%). By central review, six patients showed improved response during treatment from PR to CR/CRu; nine patients improved from stable disease (SD) to PR/CR/CRu. One patient showed an improvement both from SD to PR and then CRu.

Table 2.

Efficacy outcomes with single-agent lenalidomide in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL (n = 57)

| Outcomes | Central review | Investigator review |

|---|---|---|

| Response ratesa, n (%) | ||

| ORRb | 20 (35) | 25 (44) |

| CR/CRu | 7 (12) | 12 (21) |

| PR | 13 (23) | 13 (23) |

| SD | 25 (44) | 13 (23) |

| PD | 12 (21) | 12 (21) |

| No response assessment/missing | 0 | 7 (12) |

| Median TTFRc, month (range) | 1.9 (1.6–24.2) | 1.9 (1.6–15.2) |

| Median DOR, month (95% CI) | 16.3 (7.1-NR) | NR (15.4-NR) |

| Median DOR for CR/CRu, month (95% CI) | NR (9.7-NR) | NR (28.8-NR) |

| Median PFS, month (95% CI) | 8.8 (5.5–23.0) | 5.7 (2.7–10.7) |

| Median TTP, month (95% CI) | 8.8 (5.5–23.0) | 7.3 (3.6–17.2) |

CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; CRu, complete response unconfirmed; DOR, duration of response; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; NR, not reached; ORR, overall response rate; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; TTFR, time to first response; TTP, time to progression.

aDefined as best treatment result during the treatment phase of the study.

bORR = CR + CRu + PR.

cTime to first response = time to first CR or CRu or PR.

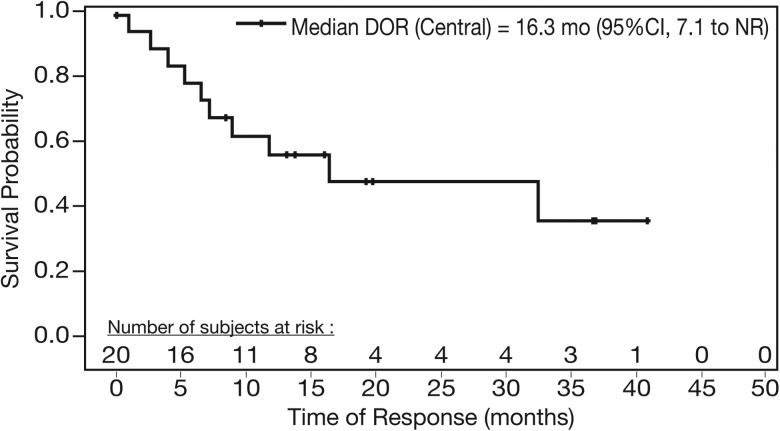

The median TTFR was 1.9 months and the median DOR was 16.3 months by central review (median 19.96-month follow-up for all responders; Figure 1). The DOR for patients with CR/CRu was not reached (NR) by central or investigator review, with a median 31.8-month follow-up for all central review-identified complete responders.

Figure 1.

Median duration of response (DOR) of single-agent lenalidomide for responders with relapsed/refractory MCL (central review).

The median PFS was 8.8 months per central review (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online), NR (95% CI, 13.5-NR) for CR/CRu patients, 23.0 months (95% CI, 13.1-NR) for all responders, and was 8.8 months (95% CI, 5.5-NR) for patients with SD. At study closure, six patients with MCL continued receiving lenalidomide.

ORR following lenalidomide was independent of baseline characteristics, prior ASCT, number of prior therapies, and inclusion of rituximab in prior treatments (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Eight of 14 patients (57%) receiving prior ASCT responded to lenalidomide per central and investigator reviews. ORR was 28% for patients without a prior ASCT, and 30% for patients refractory to their last therapy.

safety

The median duration of treatment was 100 days (range 4–1050); median dose was 25 mg/day lenalidomide (range 7–25). Thirty-four of 57 (60%) patients had one or more dose reduction/interruption due to an AE; the median time to the first dose reduction/interruption was 42.5 days. Initial AE-related dose interruptions lasted a median of 13 days. Neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were the most common treatment-related AEs leading to dose reductions/interruptions (33% and 26%, respectively) or discontinuations (7% and 11%, respectively). Seven patients died within 30 days of the last dose of lenalidomide. Five deaths were due to PD; the remaining two (grade 5 pleural effusion and respiratory failure) were unrelated to lenalidomide.

AEs related to lenalidomide treatment were experienced in 51 of 57 (90%) patients, including 33 (58%) grade 3/4 AEs and 13 (23%) serious AEs. The most common types of all-grade hematologic AEs regardless of causality were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia (Table 3). For patients experiencing grade 3/4 neutropenia, grade 3/4 febrile neutropenia was present in 4 (7%) patients, 4 (7%) had infections associated with neutropenia, and growth factors used in 16 (12%; average 2.7 days) to manage their neutropenia. Three patients (5%) were administered platelet transfusions for grade 3 thrombocytopenia; there were no reported bleeding events related to thrombocytopenia.

Table 3.

Treatment-related grade 3/4 adverse events (AEs) occurring in ≥5% of patients (n = 57)

| Adverse event | All grade, n (%) | Grade 3/4, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hematologic | ||

| Neutropenia | 30 (53) | 26 (46) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 25 (44) | 17 (30) |

| Anemia | 20 (35) | 7 (12) |

| Nonhematologic | ||

| Fatigue | 22 (39) | 5 (9) |

| Diarrhea | 16 (28) | 3 (5) |

| Dyspnea | 9 (16) | 3 (5) |

| Pleural effusion | 7 (12) | 4 (7) |

| Pain | 3 (5) | 3 (5) |

Common nonhematologic AEs were mainly grade 1/2, including fatigue (39%), diarrhea (28%), and rash (26%; none grade 3/4). One patient demonstrated grade 2-tumor flare reaction (TFR) starting day 9, cycle 1 and resolved ≤2 days with treatment (i.e. ibruprofen) without disrupting dosing. There were no reports of TLS. Three patients with no previous history of thromboembolic events (TEE, thus not considered high risk and did not receive prophylaxis) experienced one grade 1-superficial thrombophlebitis/left ankle swelling due to superficial vein thrombosis, one grade 2-thrombosis, and one grade 3-deep vein thrombosis (DVT). The third patient had heavily pretreated stage IV MCL, and underwent dose reductions for grade 3-thrombocytopenia and grade 3-neutropenia before grade 3 DVT, all resolving with treatment.

Second primary malignancies (SPMs) were reported in four patients after the initiation of lenalidomide, including one acute myeloid leukemia (AML), one prostate cancer, and two squamous cell carcinomas of the skin. The diagnoses of AML and prostate cancer occurred shortly after beginning lenalidomide (137 and 38 days, respectively), suggesting that these malignancies may not have been related to lenalidomide exposure. Also, the patient with AML was heavily pretreated with prior anti-lymphoma therapies, including rituximab and multiple cytotoxic chemotherapies (cyclophosphamide, daunorubicin, mitoxantrone, fludarabine, etoposide, and procarbazine), and the patient with prostate cancer received prior rituximab, cyclophosphamide, and fludarabine. The two squamous cell carcinomas of the skin were diagnosed 261 and 1206 days after initiating lenalidomide treatment; both successfully surgically excised. Three of these four patients achieved a PR with lenalidomide.

discussion

This long-term evaluation permitted assessment of antitumor activity of single-agent lenalidomide (35% ORR; 12% CR/CRu), including durability of response by a rigorous central review efficacy assessment. The longer median 19.96 month-follow-up in responders demonstrated a median DOR of 16.3 months, not yet been reached at the median 7.1 month-follow-up reported earlier [11]. The median DOR was not yet reached in CR/CRu patients at a median 31.76-month follow-up. The median PFS was 8.8 months (not reached in CR/CRu). Investigator assessment showed 44% ORR, DOR not yet reached, and PFS of 5.7 months. These data confirm earlier reports based on investigator assessments [10–12].

Patients in the current study were heavily pretreated (median three prior therapies), including a third refractory to their last prior therapy, 32% who received prior bortezomib, and 25% with prior ASCT. All but two patients received one or more prior rituximab-containing therapy (95% rituximab combination chemotherapy), and 35% deemed refractory to rituximab/chemotherapy. No significant differences in responses to lenalidomide were reported based on the baseline characteristics or prior therapy.

These results were supported by previous phase II studies of single-agent lenalidomide in MCL [10, 12]. In 15 heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory MCL (median four prior therapies) from the NHL-002 study [10, 12], patients received the same regimen of lenalidomide as in the current study, but for up to 52 weeks rather than until PD or intolerability, as shown here. Prior efficacy results showed an ORR of 53% (CR 20%), a median DOR of 13.7 months (95% CI, 4.0-not reached), and a median PFS of 5.6 months (95% CI, 2.6–18.2) by investigator assessment. Patients responded to lenalidomide despite prior transplantation (four of five patients) or bortezomib (two of five patients). The most common grade 3/4 AEs were hematologic, and no reported cases of TFR/TLS. A recently published phase II study in 26 relapsed/refractory MCL patients examined lenalidomide dosed at 25 mg/days, days 1–21/28 for six or less cycles, with lower maintenance lenalidomide 15 mg/day, days 1–21/28 in responders until PD/intolerability [14]. Eight patients responded during the initial treatment phase (31% ORR; 8% CR), with 11 receiving less than two cycles of lenalidomide due to PD, AEs, or withdrawal of consent. The median DOR was 22.2 months, PFS 3.9 months (14.6 months for 11 patients receiving one or more cycle of maintenance), and OS 10.0 months.

Consistent with other reports of lenalidomide [10, 12], the most common grade 3/4 AEs were cytopenias and were managed with dose reductions/interruptions. Neutropenia was associated with an infrequent usage of growth factors and low incidence of infections; thrombocytopenia was associated with infrequent platelet transfusions and no bleeding events. These data are consistent with the low incidence of clinical problems secondary to cytopenia in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma patients treated with lenalidomide/dexamethasone [15, 16].

There were no reports of TLS in this study, in contrast to the higher incidence of TLS/TFR in CLL patients receiving lenalidomide [17, 18]. Eve et al. [14, 19] reported four cases of TFR in MCL, three shown within the first 8 days of treatment. In the current study, one patient developed grade 2 TFR on day 9 that resolved without disrupting dosing. Reports of TFR are relatively low in lymphoma studies; TLS has not been reported for lenalidomide in MCL patients.

Thromboembolic events were reported in three patients (5%) with no previous history of TEEs and who did not receive prophylaxis for TEEs; two TEEs were grade 1/2, one was grade 3 and resolved with treatment. Definitive conclusions to determine the need for TEE prophylaxis could not be drawn based on the low number of events and single-arm study design of this study. Four patients were diagnosed with SPMs here. Patients with MCL may be at an increased risk of SPMs due to older age and prolonged exposure to chemotherapy and total body irradiation. Five-year cumulative incidence of SPMs of 11% was reported in MCL [20] and treatment with alkylating agents in NHL is associated with an increased risk of AML/MDS of 1%–1.5%/year within 2–10 years following initiation of primary chemotherapy [21].

Approved agents with reported activity in relapsed MCL include proteasome inhibitor bortezomib and mTOR inhibitor temsirolimus. Bortezomib was approved in the United States based on a single-arm phase II study (PINNACLE), showing ORR of 32% (8% CR/CRu) and DOR of 9.2 months in 155 relapsed/refractory MCL patients [4]. At a median follow-up of 26.4 months, bortezomib showed a median PFS of 6.5 months, and median time to next therapy of 7.4 months. Grade 3/4 AEs included 67% lymphopenia and 13% peripheral neuropathy. Temsirolimus was approved for relapsed/refractory MCL in the EU based on a randomized study, showing an ORR of 22% (1 CR) with a median DOR of 7.1 months [5]. The most common grade 3/4 AEs with temsirolimus included thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and anemia, thrombocytopenia most commonly causing dose reductions. The data in this report highlight some important differences between lenalidomide and other agents. Although bortezomib and temsirolimus demonstrated relatively similar PFS (and ORR with bortezomib) with lenalidomide in relapsed/refractory MCL, lenalidomide showed more durable DOR with manageable tolerability.

In summary, the results from the long-term evaluation of patients with relapsed/refractory MCL from the NHL-003 study further confirm the activity of single-agent oral lenalidomide and show durable response with manageable toxicity. These results support continued investigation of lenalidomide in MCL.

funding

The NHL-003 study was a Celgene-sponsored study and therefore, there was no grant number associated with the study.

disclosure

MSC has received consulting fees from Celgene. HT, MSC, JMV, and TEW have received research funding from Celgene to conduct clinical studies. PLZ, CH, CBR, and JP have no financial relationships to disclose. LZ, KP, and JL are employees of Celgene and have received Celgene stock and stock options.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

The authors received editorial support in the preparation of this manuscript from Anna Bratta, MS, and Julie Kern, PhD, CMPP, of Bio Connections LLC, funded by Celgene Corporation. The authors directed development of the manuscript and were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions.

references

- 1.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Non-Hodgkin's Lymphomas. 2013. Version 1. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.McKay P, Leach M, Jackson R, et al. Guidelines for the investigation and management of mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2012;159:405–426. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ansell SM, Inwards DJ, Rowland KM, Jr, et al. Low-dose, single-agent temsirolimus for relapsed mantle cell lymphoma: a phase 2 trial in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group. Cancer. 2008;113:508–514. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goy A, Bernstein SH, Kahl BS, et al. Bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma: updated time-to-event analyses of the multicenter phase 2 PINNACLE study. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:520–525. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hess G, Herbrecht R, Romaguera J, et al. Phase III study to evaluate temsirolimus compared with investigator's choice therapy for the treatment of relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3822–3829. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.PI R. 2013. REVLIMID (lenalidomide) prescribing information. June.

- 7.Qian Z, Zhang L, Cai Z, et al. Lenalidomide synergizes with dexamethasone to induce growth arrest and apoptosis of mantle cell lymphoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Leuk Res. 2011;35:380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu L, Adams M, Carter T, et al. Lenalidomide enhances natural killer cell and monocyte-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity of rituximab-treated CD20+ tumor cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4650–4657. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L, Qian Z, Cai Z, et al. Synergistic antitumor effects of lenalidomide and rituximab on mantle cell lymphoma in vitro and in vivo. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:553–559. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiernik PH, Lossos IS, Tuscano JM, et al. Lenalidomide monotherapy in relapsed or refractory aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4952–4957. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.3429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Witzig TE, Vose JM, Zinzani PL, et al. An international phase II trial of single-agent lenalidomide for relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1622–1627. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Habermann TM, Lossos IS, Justice G, et al. Lenalidomide oral monotherapy produces a high response rate in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:344–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244–1253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eve HE, Carey S, Richardson SJ, et al. Single-agent lenalidomide in relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma: results from a UK phase II study suggest activity and possible gender differences. Br J Haematol. 2012;159:154–163. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimopoulos M, Spencer A, Attal M, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2123–2132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weber DM, Chen C, Niesvizky R, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma in North America. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2133–2142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrajoli A, Lee BN, Schlette EJ, et al. Lenalidomide induces complete and partial remissions in patients with relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:5291–5297. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chanan-Khan AA, Chitta K, Ersing N, et al. Biological effects and clinical significance of lenalidomide-induced tumour flare reaction in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: in vivo evidence of immune activation and antitumour response. Br J Haematol. 2011;155:457–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eve HE, Rule SA. Lenalidomide-induced tumour flare reaction in mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2010;151:410–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barista I, Cabanillas F, Romaguera JE, et al. Is there an increased rate of additional malignancies in patients with mantle cell lymphoma? Ann Oncol. 2002;13:318–322. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armitage JO, Carbone PP, Connors JM, et al. Treatment-related myelodysplasia and acute leukemia in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:897–906. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.