Abstract

The Lithistida sponges have been an important source of structurally complex natural products with potent biological activities. Examples of compounds marketed as biological markers along with recent advances in defining the modes of action and biomedical potential of lithistid derived compounds is presented.

Introduction

The Lithistida represent a polyphyletic assemblage of sponges loosely grouped together based upon the presence of an interlocking siliceous desma skeleton that can confer on the sponges consistencies that range from firm to rock hard [1]. These sponges occur in both deep and shallow water habitats world-wide and have been the source of over 300 natural products (see Supplementary Table S1 for examples of the major classes of bioactive compounds). The literature describing Lithistida-derived natural products has been reviewed through 2002 [2,3] and provides support that sponges of this order represent an outstanding source of structurally complex natural products many of which possess potent biological activities. Early work by Bewley and Faulkner [4] laid the foundations for later findings that many of these compounds are synthesized by microbes that live in association with the sponges [5-7]. The current review will highlight some of the more important compounds found in these sponges and recent advances in defining their modes of action and therapeutic potential.

Commercially available biochemical probes from Lithistida sponges

The calyculins represent a class of complex polyketide-derived compounds that demonstrate low nanomolar inhibition of the serine/threonine protein phosphatases 1 and 2A. Protein phosphorylation by kinases and dephosphorylation by phosphatases is integral to the regulation of many biochemical pathways and the calyculins have been important tool molecules for investigating cellular processes. Calyculin A, 1, the parent molecule in the series, was first isolated from the sponge Discodermia calyx [8]. Eighteen additional calyculins including the calyculinamides, the clavosines, the hemicalyculins, the geometricins and swinhoeiamide A have been isolated. The calyculins belong to the okadaic acid class of protein phosphatase inhibitors [9] but in contrast to okadaic acid, calyculin A shows moderate selectivity for PP1 providing some advantages as biochemical probes. The structures, biological activities and synthesis of the calyculin-class of compounds have been recently reviewed [10].Other protein phosphatase inhibitors reported from lithistid sponges which are commercially available are the motopurins (nodularin V) and congeners [11].

The complex polyketides swinholide A, 2, [12] and bistheonellide A [13] are important biochemical probes used to study actin dynamics. They are dimeric polyketide macrolides with C2 symmetry and differ from each other only in the presence of an additional C2 unit in the polyketide backbone of bistheonellide A. Both compounds show nanomolar potency against tumor cell lines and are potent actin poisons but differ slightly in their effects on actin. Swinholide A has been shown to disrupt the actin cytoskeleton in cultured cells, sequester actin dimers in vitro in both polymerizing and depolymerizing buffers with a stoichiometry of one molecule of swinholide A per actin dimer, and to rapidly sever F-actin [14,15]. Bistheonellide A has been shown to inhibit polymerization of G-actin and to depolymerize F-actin in a concentration dependent fashion [15]. In contrast to swinholide A, it does not sever F-actin and it increases the rate of nucleotide exchange in G-actin while swinholide A decreases the rate of nucleotide exchange. These differences are thought to occur due to different conformational changes in actin upon binding of the natural product and have led in part to their utility in studies aimed at understanding actin dynamics and structure [16]. Other actin disrupting compounds from the Lithistida are the kabiramides [17], sphinxolides [18] and reidispongiolides [18], but these compounds are not commercially available.

Antifungal and Anti-HIV peptides from the Lithistida-a common mechanism of action?

Lithistid sponges have been the source of many peptides and depsipeptides with antifungal activity (see Supplementary Table S1 for examples). In an elegant example that demonstrates the utility of yeast genetic methodologies in defining the mode of action of natural products, a molecular barcoded yeast open reading frame library (MoBY-ORF) [19] has been used to identify the mode of action of theopalauamide, 3 [20]. In the MoBY-ORF method, individual genes are introduced via barcoded plasmids into a recessive drug-resistant mutant where resistance is associated with a single gene. The transformants are pooled and grown in the presence and absence of drug. The plasmids from the two pools are extracted and PCR conducted to amplify the barcodes. The barcodes are then hybridized to a barcode array. Because the wild-type copy of the drug resistant gene will complement a recessive drug-resistant phenotype, its corresponding barcode should be depleted relative to the others in the pool after treatment with drug. These studies identified mevalonate pyrophosphate decarboxylase, an enzyme involved in ergosterol biosynthesis, as a potential target for theopalauamide. Additional studies to define whether theopalauamide acted on the enzyme itself or on downstream products were conducted and it was determined that theopalauamide directly interacts with ergosterol. Cells could be rescued by treatment with excess of ergosterol or cholesterol. This work was extended to the structurally related theonellamide A, which was shown to share this mechanism of action [19]. A second study, also using a yeast chemical biology approach [21], indicated a mechanistic link between theonellamide F and 1,3-beta-D-glucan synthesis and showed that theonellamide F induced overproduction of 1,3-beta-D-glucan in a Rho1-dependent manner. Subcellular localization and binding studies using a fluorescent theonellamide F derivative indicated that theonellamide F binds to 3β-hydroxysterols including ergosterol. Theopalauamide and the theonellamides represent a novel, structurally unprecedented class of sterol binding agents and it remains to be seen whether they will be selective enough to have clinical utility.

Many of the cyclic peptides and depsipeptides reported from the Lithistida demonstrate potent anti-HIV activity [22]. Examples include: papuamides A-D from Theonella spp.; callipeltin A from Callipelta sp.; mirabamides A-D from Siliquaria mirabilis; homophymines from Homophymia sp.; and the koshikamides from Theonella sp.. Features common to many of the compounds are the presence of a highly methylated lipophilic side chain, a 2,3-dimethylglutamine residue, N-terminal aliphatic hydroxyl acid moieties and in many, but not all, a β-methoxy tyrosine unit. Many of the compounds also possess a homoproline moiety. The compounds have been reported to be active in HIV neutralization assays, to block viral fusion, and for some molecules, both activities have been reported [22]. Some of the compounds also have antifungal activity. One member of the class, papuamide A, 4, shows nM activity against HIV induced T cell death and blocks viral entry. It has been the focus of extensive studies to define its mode of action [23]. Surface plasmon resonance studies indicated that papuamide A does not interact directly with gp120 or sCD4, two important proteins involved in HIV fusion. It also showed no differential effects on viruses that infect cells expressing the chemokine receptors CCR5 or CXCR4, also important in viral fusion. Time course studies indicated that papuamide acts on the virus itself, as delayed treatment with papuamide (2 hr) resulted in a decrease in infectivity of the virus. Viral pretreatment with papuamide A resulted in approximately 50% reduction in infectivity, and washing did not reduce this effect, suggesting that papuamide A either remains stably bound to the virus or inactivates it. Papuamide A was demonstrated to bind to phosphtidylserine and may affect the viral membrane. Anjelic et. al. propose that papuamide A works through a membrane targeting mechanism in which the lipophilic chain of the peptide inserts into the membrane and the tyrosine unit binds to sterols in the membrane. Cholesterol is a major component of the HIV viral membrane and therefore if this model is correct, the peptides may exert their virucidal activity in a manner related to that of the antifungal peptides described above. No studies to define whether the anti-HIV activity can be rescued by addition of cholesterol or other β-hydroxysterols have been reported. Research is on-going with regard to defining the clinical utility of these compounds.

Tubulin Active agents-Leads for development of clinically useful agents

Disruption of the microtubule network is a clinically relevant mechanism of action for the development of new anticancer drugs. Discodermolide, 5, is a polyketide isolated from the sponge Discodermia dissoluta which was initially reported to have cytotoxic and immunosuppressive activity [24]. Discodermolide is a potent antimitotic agent that acts through induction of polymerization of tubulin and hyperstabilization of microtubules in a fashion similar to the clinically relevant paclitaxel [25]. Discodermolide can competitively displace paclitaxel from microtubules and retains anti-proliferative activity against multidrug resistant tumor cell lines. In contrast to other agents in this class, discodermolide is able to induce tubulin polymerization in the absence of GTP and at low temperatures with the resulting polymer being stable to reductions in temperature. It has been shown to display synergistic activity with paclitaxel both in vitro and in vivo suggesting that it may have utility in combination therapeutic regimes that would reduce toxicity of the current paclitaxel chemotherapeutic treatment [26-28]. It is also unique amongst the microtubule stabilizing agents in inducing accelerated cell senescence which may provide clinical opportunities different than other compounds in this class [29].

Due to its unique biological properties, discodermolide has been the subject of significant activity by the synthetic organic chemistry community with over 15 total syntheses of the compound reported [30,31]. A gram-scale synthesis developed by the Smith group was key to the clinical evaluation of the compound [32] and when coupled with other synthetic schemes, led to a refined process in which over 60 g of synthetic (+)-discodermolide was produced for use in clinical trials [33]. Discodermolide was evaluated in Phase I clinical trials for solid tumor malignancies at the Cancer Therapy and Research Center in San Antonio, Texas but the trials were halted due to adverse events (Mita A et al., abstract in J. Clinical Oncol 2004, 22:2025). This set back, along with the observation of synergistic activity with paclitaxel has contributed to a significant interest in preparing analogs of discodermolide with reduced toxicity [34]. Substantial research has also gone into defining the binding pose of discodermolide bound to purified tubulin and assembled microtubules [35-37]. The majority of these use molecular mechanics calculations and NMR methods to define structural features in discodermolide that interact with tubulin and to rationalize these with the known structure activity data [34]. HDX labeling of chick erythrocyte microtubules bound to paclitaxel or discodermolide has identified structural features in microtubules that are blocked from deuterium exchange in the bound conformations and clearly indicate changes in microtubule structure based upon which agent (paclitaxel vs. discodermolide) is bound [38]. The proposed binding model derived from this study is consistent with cytotoxicity data observed for cell lines with defined tubulin mutations and may provide a molecular basis for the observed synergy between the drugs. No consensus has yet been reached regarding the final binding pose of discodermolide with microtubules, but what is clear is that discodermolide adopts a hairpin conformation in solution due to syn-pentane interactions which then binds the taxane binding site on β-tubulin in a manner complementary to that of paclitaxel.

A new use for discodermolide may be in increasing the success of glaucoma filtration surgery through reducing postoperative wound fibrosis (Shuba L et al. abstract 633/A477 ARVO 2010, Fort Lauderdale, FL, May 2010). Shuba and co-workers have demonstrated that discodermolide can hyper-stabilize microtubules in human tenon and conjunctival fibroblasts. Both short- and long-term discodermolide treatments inhibit proliferation of human conjunctival fibroblasts and discodermolide treatment improved the outcome of glaucoma filtration surgery in rabbits without causing any adverse effects. Discodermolide may be a safe alternative drug to mitomycin C, a drug used clinically for fibrosis suppression after glaucoma filtration surgery.

Dictyostatin-1, a naturally occurring analog of discodermolide was first reported as a potent cytotoxic macrolide from a sponge of the genus Spongia [39] and later re-isolated from a lithistid sponge of the family Neopeltidae. Like discodermolide, dictyostatin-1, 6, is a tubulin polymerizing and hyperstabilizing agent. It has approximately ten-fold greater cytotoxicity than discodermolide for the majority of tumor cell lines assayed and has virtually no drop in potency in multi-drug resistant cancer cell lines expressing the p-glycoprotein efflux pump [40]. It can compete with paclitaxel and discodermolide for microtubules and molecular modeling studies suggest that it adopts the same hairpin conformation as discodermolide [41]. Clinical development of dictyostatin-1 has been hindered by patent coverage and therefore a significant effort has been made to prepare new analogs and to explore the structure activity relationships of dictyostatin analogs [42]. One exceptionally promising analog is 6-epidictyostatin-1 reported by Day, Curran and co-workers [43]. Evaluation of 6-epi dictyostatin in SCID mice bearing MDA-MB231 human breast cancer xenografts demonstrated that it induced tumor regression for 14 days for six out of nine mice treated with 6-epidictyostatin-1 and for 28 days for the remaining three mice. In contrast, no mice treated with paclitaxel showed tumor regression in this study. The mean time to two tumor doublings for paclitaxel treated, 6-epidictyostatin-1 treated, vehicle treated and control mice was 19.6 + 7.4, 38.1 + 12.1, 9.8 + 3.1 and 7.7 + 2.4 days, respectively, giving a statistically significant enhanced antitumor response for 6-epidictyostatin-1 versus paclitaxel. Work is on-going with regards to its further development. A 9-methoxy derivative of a hybrid molecule encompassing structural characteristics of both discodermolide and dictyostatin, 7, has been prepared by the Paterson group and shows nearly equal potency to dictyostatin-1 and ten fold greater potency than discodermolide against selected pancreatic cancer cell lines [44]. This compound represents a strong candidate for clinical development and synthesis of sufficient material for evaluation in experimental models of pancreatic cancer is underway.

The Lithistida are armed with a multi-faceted chemical armamentarium

One of the most interesting aspects of Lithistid chemistry is the diversity of structures and biological activities of compounds isolated from these sponges (Supplementary Information Table S1). In numerous instances, single specimens possess a wealth of different chemotypes many of which display distinctly different biological activities [11,45]. One illustrative example is a sponge of the family Neopeltidae, collected off Jamaica in 442 m of water from which dictyostatin-1, 6, kabiramide C acetate, 8, and neopeltolide, 9 were isolated. Additional minor kabiramides were also present in the specimen. The mode of action of all three classes of these potent cytotoxic agents has been defined: dictyostatin-1 is a potent (nM) cytotoxic agent that works through polymerization of tubulin and stabilization of microtubules [40]; the kabiramides are potent (nM) cytotoxic agents that act via inhibition of actin dynamics [46]; and neopeltolide shows picomolar potency against some tumor cell lines while being only cytostatic in others [47] and has been shown to inhibit oxidative phosphorylation through targeting the cytochrome bc1 complex resulting in blocking of mitochondrial ATP synthesis [48]. This remarkable sponge contains three structurally distinct classes of compounds that target three different biochemical processes: microtubule structure and function; actin and microfilament structure; and energy production (ATP synthesis). Other organisms collected at the same site had none of these compounds. Given that there is growing evidence that many of the compounds isolated from the lithistids may be produced by associated microbes [7] a number of questions can be posed: What drives the chemotypes in Lithistid sponges? Does one microbe (or type of microbe) produce all three compounds or are multiple microbes involved? If multiple microbes, is it cooperation, competition or some external environmental factor that drives production? Does the sponge have any role in production or is it simply an inert “fermentation reaction vessel”? Is there something special about lithistid sponge physiology and architecture that drives the production of unique natural products? Can this be emulated to successfully culture lithistid-derived microbes and induce compound biosynthesis with the goal of providing economically viable supplies of biomedically important natural products? These are just a few questions which remain to be answered.

Future Directions

The diversity of chemical structures and biological activities found in the Lithistida makes it clear that they remain an important source of novel metabolites. Continued exploration of new habitats will certainly lead to the discovery of new members of this elite order of sponge and with it new chemical entities. The sponges occur in both shallow and deep-water habitats and access to tools that allow for exploration of mesophotic and deep-water habitats should lead to new collections of these sponges. Older compounds already described but for which limited biological activity data has been reported are likely to provide new opportunities for drug or biochemical probe discovery if tested in new assays. The Lithistida remain an exciting source of chemical diversity useful in biomedical studies and should be an important model system for those interested in the ecology of sponge-microbial communities and the role of these microbes in production of biologically active natural products.

Supplementary Material

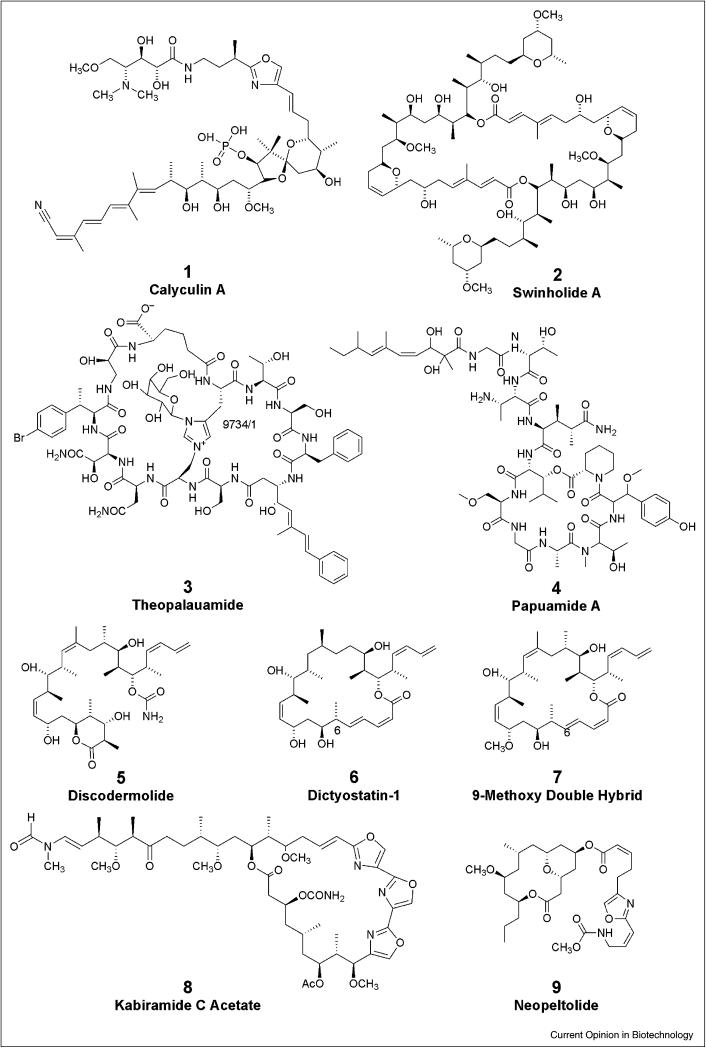

Figure 1.

Selected compounds from the Lithistida useful in biomedical research or with potential clinical significance.

Acknowledgements

A portion of the work described herein was supported by NIH grant RO1-CA093455.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary materials A table detailing the major classes of metabolites derived from Lithistida sponges and their associated bioactivity can be found in the supplementary material.

References

- 1.Kelly-Borges M, Pomponi SA. Phylogeny and classification of lithistid sponges (porifera: Demospongiae): a preliminary assessment using ribosomal DNA sequence comparisons. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol. 1994;3:87–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bewley CA, Faulkner DJ. Lithistid sponges: star performers or hosts to the stars. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998;37:2163–2178. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980904)37:16<2162::AID-ANIE2162>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Auria MV, Zampella A, Zollo F. The chemistry of lithistid sponge: a spectacular source of new metabolites. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2002;26:1175–1258. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bewley CA, Holland ND, Faulkner DJ. Two classes of metabolites from Theonella swinhoei are localized in distinct populations of bacterial symbionts. Experientia. 1996;52:716–722. doi: 10.1007/BF01925581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piel J, Hui D, Wen G, Butzke D, Platzer M, Fusetani N, Matsunaga S. Antitumor polyketide biosynthesis by an uncultivated bacterial symbiont of the marine sponge Theonella swinhoei. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16222–16227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405976101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piel J, Butzke D, Fusetani N, Hui D, Platzer M, Wen G, Matsunaga S. Exploring the Chemistry of Uncultivated Bacterial Symbionts: Antitumor Polyketides of the Pederin Family. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:472–479. doi: 10.1021/np049612d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uria A, Piel J. Cultivation-independent approaches to investigate the chemistry of marine symbiotic bacteria. Phytochemistry Reviews. 2009;8:401–414. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato Y, Fusetani N, Matsunaga S, Hashimoto K, Fujita S, Furuya T. Bioactive marine metabolites. Part 16. Calyculin A. A novel antitumor metabolite from the marine sponge Discodermia calyx. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1986;108:2780–2781. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishihara H, Martin BL, Brautigan DL, Karaki H, Ozaki H, Kato Y, Fusetani N, Watabe S, Hashimoto K, Uemura D, et al. Calyculin A and okadaic acid: inhibitors of protein phosphatase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;159:871–877. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •10.Fagerholm AE, Habrant D, Koskinen AM. Calyculins and related marine natural products as serine-threonine protein phosphatase PP1 and PP2A inhibitors and total syntheses of calyculin A, B, and C. Mar Drugs. 2010;8:122–172. doi: 10.3390/md80100122. A review describing the structures, synthesis and biological activities of the calyculin class of marine natural product.

- 11.Wegerski CJ, Hammond J, Tenney K, Matainaho T, Crews P. A serendipitous discovery of isomotuporin-containing sponge populations of Theonella swinhoei. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:89–94. doi: 10.1021/np060464w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmely S, Kashman Y. Structure of swinholide-A, a new macrolide from the marine sponge Theonella swinhoei. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:511–514. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato Y, Fusetani N, Matsunaga S, Hashimoto K, Sakai R, Higa T, Kashman Y. Antitumor macrodiolides isolated from a marine sponge sp.: Structure revision of misakinolide A. Tetrahedron Letters. 1987;28:6225–6228. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bubb MR, Spector I, Bershadsky AD, Korn ED. Swinholide A is a microfilament disrupting marine toxin that stabilizes actin dimers and severs actin filaments. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3463–3466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.8.3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saito SY, Watabe S, Ozaki H, Kobayashi M, Suzuki T, Kobayashi H, Fusetani N, Karaki H. Actin-depolymerizing effect of dimeric macrolides, bistheonellide A and swinholide A. J Biochem. 1998;123:571–578. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spector I, Braet F, Shochet NR, Bubb MR. New anti-actin drugs in the study of the organization and function of the actin cytoskeleton. Microsc Res Tech. 1999;47:18–37. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19991001)47:1<18::AID-JEMT3>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klenchin VA, Allingham JS, King R, Tanaka J, Marriott G, Rayment I. Trisoxazole macrolide toxins mimic the binding of actin-capping proteins to actin. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:1058–1063. doi: 10.1038/nsb1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allingham JS, Zampella A, D’Auria MV, Rayment I. Structures of microfilament destabilizing toxins bound to actin provide insight into toxin design and activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14527–14532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502089102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••19.Ho CH, Magtanong L, Barker SL, Gresham D, Nishimura S, Natarajan P, Koh JL, Porter J, Gray CA, Andersen RJ, et al. A molecular barcoded yeast ORF library enables mode-of-action analysis of bioactive compounds. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:369–377. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1534. Using yeast genetic methods as a tool, the compounds theopalauamide and theonellamide A were determined to exert their antifungal activity through binding 3-beta hydroxysterols. They represent a new class of sterol binding agents.

- 20.Schmidt EW, Bewley CA, Faulkner DJ. Theopalauamide, a Bicyclic Glycopeptide from Filamentous Bacterial Symbionts of the Lithistid Sponge Theonella swinhoei from Palau and Mozambique. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 1998;63:1254–1258. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishimura S, Arita Y, Honda M, Iwamoto K, Matsuyama A, Shirai A, Kawasaki H, Kakeya H, Kobayashi T, Matsunaga S, et al. Marine antifungal theonellamides target 3beta-hydroxysterol to activate Rho1 signaling. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:519–526. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••22.Andavan GS, Lemmens-Gruber R. Cyclodepsipeptides from marine sponges: natural agents for drug research. Marine drugs. 2010;8:810–834. doi: 10.3390/md8030810. This review describes the structures, synthesis and biological activities of the cyclic peptides from sponges. Many of the compounds described are from the Lithistida.

- •23.Andjelic CD, Planelles V, Barrows LR. Characterizing the anti-HIV activity of papuamide A. Marine drugs. 2008;6:528–549. doi: 10.3390/md20080027. The mode of action of the anti-HIV agent papuamide A was determined to be through interaction with the virus rather than through blocking viral entry into cells. Papuamide is suggested to be virucidal through binding cholesterol in the viral envelope.

- 24.Gunasekera SP, Gunasekera M, Longley RE, Schulte GK. Discodermolide: a new bioactive polyhydroxylated lactone from the marine sponge Discodermia dissoluta. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 1990;55:4912–4915. [Google Scholar]

- 25.ter Haar E, Kowalski RJ, Hamel E, Lin CM, Longley RE, Gunasekera SP, Rosenkranz HS, Day BW. Discodermolide, a cytotoxic marine agent that stabilizes microtubules more potently than taxol. Biochemistry. 1996;35:243–250. doi: 10.1021/bi9515127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martello LA, McDaid HM, Regl DL, Yang CP, Meng D, Pettus TR, Kaufman MD, Arimoto H, Danishefsky SJ, Smith AB, 3rd, et al. Taxol and discodermolide represent a synergistic drug combination in human carcinoma cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1978–1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honore S, Kamath K, Braguer D, Horwitz SB, Wilson L, Briand C, Jordan MA. Synergistic suppression of microtubule dynamics by discodermolide and paclitaxel in non-small cell lung carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4957–4964. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang GS, Lopez-Barcons L, Freeze BS, Smith AB, 3rd, Goldberg GL, Horwitz SB, McDaid HM. Potentiation of taxol efficacy and by discodermolide in ovarian carcinoma xenograft-bearing mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:298–304. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein LE, Freeze BS, Smith AB, 3rd, Horwitz SB. The microtubule stabilizing agent discodermolide is a potent inducer of accelerated cell senescence. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:501–507. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.3.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •30.Smith AB, Freeze BS. (+)-Discodermolide: total synthesis, construction of novel analogues, and biological evaluation. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:261–298. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.10.039. This paper provides an in depth review on the chemistry and biology of discodermolide.

- •31.Paterson I, Florence GJ. The chemical synthesis of discodermolide. Top. Curr. Chem. 2009;286:73–119. doi: 10.1007/128_2008_7. This paper provides an in depth review on the synthetic approaches to discodermolide.

- 32.Smith AB, 3rd, Kaufman MD, Beauchamp TJ, LaMarche MJ, Arimoto H. Gram-scale synthesis of (+)-discodermolide. Org Lett. 1999;1:1823–1826. doi: 10.1021/ol9910870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mickel SJ. Total synthesis of the marine natural product (+)-discodermolide in multigram quantities. Pure Appl. Chem. 2007;79:685–700. [Google Scholar]

- •34.Shaw SJ. The structure activity relationship of discodermolide analogues. Mini reviews in medicinal chemistry. 2008;8:276–284. doi: 10.2174/138955708783744137. This paper provides an in depth review on the structure activity relationships for discodermolide and analogs.

- 35.Jimenez-Barbero J, Amat-Guerri F, Snyder JP. The solid state, solution and tubulin-bound conformations of agents that promote microtubule stabilization. Curr Med Chem Anticancer Agents. 2002;2:91–122. doi: 10.2174/1568011023354416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanchez-Pedregal VM, Kubicek K, Meiler J, Lyothier I, Paterson I, Carlomagno T. The tubulin-bound conformation of discodermolide derived by NMR studies in solution supports a common pharmacophore model for epothilone and discodermolide. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:7388–7394. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jogalekar AS, Kriel FH, Shi Q, Cornett B, Cicero D, Snyder JP. The discodermolide hairpin structure flows from conformationally stable modular motifs. J Med Chem. 2010;53:155–165. doi: 10.1021/jm9015284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••.Khrapunovich-Baine M, Menon V, Verdier-Pinard P, Smith AB, 3rd, Angeletti RH, Fiser A, Horwitz SB, Xiao H. Distinct pose of discodermolide in taxol binding pocket drives a complementary mode of microtubule stabilization. Biochemistry. 2009;48:11664–11677. doi: 10.1021/bi901351q. The authors use HDX labeling of microtubules bound to discodermolide or paclitaxel to define similarities and differences in microtubule structure upon binding of drug. This suggests a molecular basis for the synergistic activity observed between discodermolide and paclitaxel.

- 39.Pettit GR, Cichacz ZA, Gao F, Boyd MR, Schmidt JM. Isolation and structure of the cancer cell growth inhibitor dictyostatin 1. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications. 1994:1111–1112. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Isbrucker RA, Cummins J, Pomponi SA, Longley RE, Wright AE. Tubulin polymerizing activity of dictyostatin-1, a polyketide of marine sponge origin. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Canales A, Matesanz R, Gardner NM, Andreu JM, Paterson I, Diaz JF, Jimenez-Barbero J. The bound conformation of microtubule-stabilizing agents: NMR insights into the bioactive 3D structure of discodermolide and dictyostatin. Chemistry. 2008;14:7557–7569. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pfeiffer B, Kuzniewski CN, Wullschleger C, Altmann KH. Macrolide-based microtubule-stabilizing agents - chemistry and structure-activity relationships. Top. Curr. Chem. 2009;286:1–72. doi: 10.1007/128_2008_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eiseman JL, Bai L, Jung W-H, Moura-Letts G, Day BW, Curran DP. Improved Synthesis of 6-epi-Dictyostatin and Antitumor Efficacy in Mice Bearing MDA-MB231 Human Breast Cancer Xenografts. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;51:6650–6653. doi: 10.1021/jm800979v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paterson I, Naylor GJ, Fujita T, Guzman E, Wright AE. Total synthesis of a library of designed hybrids of the microtubule-stabilising anticancer agents taxol, discodermolide and dictyostatin. Chem Commun (Camb) 2010;46:261–263. doi: 10.1039/b921237j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Plaza A, Bifulco G, Masullo M, Lloyd JR, Keffer JL, Colin PL, Hooper JN, Bell LJ, Bewley CA. Mutremdamide A and koshikamides C-H, peptide inhibitors of HIV-1 entry from different Theonella species. J Org Chem. 2010;75:4344–4355. doi: 10.1021/jo100076g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wada S, Matsunaga S, Saito S, Fusetani N, Watabe S. Actin-binding specificity of marine macrolide toxins, mycalolide B and kabiramide D. J Biochem. 1998;123:946–952. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wright AE, Botelho JC, Guzman E, Harmody D, Linley P, McCarthy PJ, Pitts TP, Pomponi SA, Reed JK. Neopeltolide, a macrolide from a lithistid sponge of the family Neopeltidae. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:412–416. doi: 10.1021/np060597h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••48.Ulanovskaya OA, Janjic J, Suzuki M, Sabharwal SS, Schumacker PT, Kron SJ, Kozmin SA. Synthesis enables identification of the cellular target of leucascandrolide A and neopeltolide. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:418–424. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.94. This paper describes the use of a yeast genetics approach to defining the mode of action of neopeltolide and subsequent confirmation of the cytochrome bc1 complex as the molecular target for neopeltolide.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.