Abstract

Objective

To assess referrals to sedation examining dental anxiety and background of patients and compare these characteristics to those referred to a restorative dentistry clinic.

Design

Descriptive, cross sectional survey and chart review.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects were 100 consecutive new patients in Sedation and Special Care and 50 new patients in Restorative Dentistry at Guy’s and St Thomas NHS Foundation Trust. A questionnaire included demographics, self-reported oral health and dental attendance, and dental fear. Information from the patient’s record was taken: ASA Classification, previous sedation or general anaesthesia, and alcohol and tobacco use, and medications.

Results

The best predictors of referral were dental anxiety level and an irregular attendance. The most important fears were seeing, hearing and feeling the vibrations of the dental drill, and the perception of an accelerated heart rate. Other factors, such as general, mental and dental health, and alcohol use were related to referral but less important.

Conclusions

Referral is consistent with the goal of the Sedation Clinic to see anxious patients. Referring general practitioners are able to identify these patients.

Introduction

A large proportion of adults in the United Kingdom are afraid of dentists (Nuttall et al., 2001)1. Approximately one in four adults in the UK delays seeking help for a painful dental condition as a result of their dental fear. Similarly, as many as one-in-five adults in North America is fearful of the dentist (Smith & Heaton, 2003)2. The prevalence of dental anxiety has not changed markedly in the last 30 years, in spite of more modern and less painful dental technology.

Fear and anxiety lead to avoidance of dental treatment, which in turn leads to impaired oral health (McGrath and Bedi, 2003)3. Research throughout the world has shown repeatedly that disadvantaged and medically compromised populations have the greatest levels and frequencies of dental fear3–9

As a result of irregular attendance and delay in seeking treatment, individuals with dental fear tend to be referred for specialist dental care and receive treatment under sedation or general anaesthesia. Data from the Business Services Authority for 2003 (the last year for which data are available), suggests that in primary care alone over £6 million was spent on treatment under sedation. This is an underestimate of the total cost because does not include the costs of secondary care and the Community Dental Service nor the time lost from productive work and other activities associated with dental infections. Irrespective of the cost, services are often in short supply making the question of how these services are rationed of public health importance10.

Objective

To assess the process of referral to a Sedation Clinic by examining the dental anxiety level and background of patients seeking care being referred and compare these characteristics to those of patients seeking care at the restorative dentistry clinic.

Design

This is a descriptive, cross sectional study.

Setting

The study was conducted in the departments of Sedation and Special Care Dentistry and Restorative dentistry at Guy’s and St Thomas NHS Foundation Trust. The study was conducted between January and June 2007 in the Division of Restorative Dentistry

Subjects and methods

100 consecutive patients on a new patient clinic in the department of sedation and special care dentistry and 50 patients attending new patient clinics in restorative dentistry at Guy’s and St Thomas NHS Foundation Trust. Patients being evaluated for the sedation clinic (SC) have been referred because their general dental practitioner has been unable to provide dental care due to their anxiety. Patients attending the restorative clinic (RC) have been referred for complex dental problems.

Patients were approached by a member of the staff while waiting to be seen by the dentist. At the SC they were told “We hope that by finding out why people are anxious about coming to the dentist we will be able to improve our service.” At the restorative clinic patients were given the same information but additionally told “You might not be very anxious yourself but we plan to compare results with people attending our anxiety clinics.” The number of people refusing to take part in each setting was documented.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of St Thomas’ Hospital. The survey was confidential and the informed consent of each participant was obtained.

A 34-item written questionnaire was administered after confirmation that the patients was able to read and write English and were happy to answer questions. The questionnaire included demographic information, self reported oral health (4-point Likert-like scale ranging from poor to excellent), self reported dental attendance (5-point Likert-like scale ranging from “only when I need to” to “more often than every 6 months”) and reasons for visits to the dentist (emergency treatment or routine checkup cleaning or filling), anxiety regarding dental injections (5 items ranging from not at all true to absolutely true),11 and a general measure of dental fear (Dental Fear Survey (DFS, 20 items, 5-point scales) as well as the subscores on the DFS for Anticipation, Specific Fears and Physiology.12 Additional items were included in the questionnaire to capture other aspects of dental anxiety. The questionnaire was pretested before use. Information was taken from the patient’s medical record: American Society of Anesthesiologists Classification (ASA), previous sedation or general anaesthesia for dentistry and alcohol and tobacco use and a note made of medication taken by the patients

The data were entered into Excel, edited, and analysed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 13).

Main outcome measures

The main out come variable was treatment at the Sedation and Special Care Dentistry Clinic (SC) or the restorative dentistry clinic. In regression analysis, this variable either took the value of 1 when the patient was seen at the SC or 0 when treated in the restorative dentistry clinic.

Results

One hundred consecutive new patients from the SC (77% female, mean age 36.5 years, range 16 to 67) and 50 consecutive new patients from the Restorative Clinic (52% female, mean age 42.4 years, range 15 to 75) participated in the study. There were three people who declined to take part in the sedation group and none in the restorative group. The level of education reached by the participants in the two groups is summarised in Table 1. Of the sedation group 81% were white as were 70% of the restorative group (35/50), the self-reported ethnicity of the participants is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the demographic characteristics of participants from Sedation and Restorative clinics.

| Participants from Restorative clinic (n=50) | Participants from Sedation clinic (n=100) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Highest Education level | ||

| O levels | 8 | 57 |

| A levels | 7 | 10 |

| BTEC | 3 | 12 |

| Degree | 8 | 8 |

| Postgraduate Qualifications | 9 | 3 |

| Missing data | (15) | (10) |

|

| ||

| Chi-square=26.9 p<0.001

| ||

| Ethnicity | ||

| White British a | 27 | 65 |

| White Irish a | 0 | 4 |

| White English a | 3 | 6 |

| White Scottish a | 0 | 1 |

| White Welsh a | 2 | 0 |

| White Portuguese a | 0 | 2 |

| White Spanish a | 1 | 0 |

| White Turkish a | 0 | 1 |

| White Turkish Cypriot a | 1 | 1 |

| Other White a | 1 | 1 |

| British Indian b | 3 | 1 |

| Other Asian b | 0 | 2 |

| Black Caribbean b | 4 | 3 |

| Black British b | 2 | 7 |

| Mixed Black b | 0 | 1 |

| Other Black b | 1 | 0 |

| Middle Eastern b | 2 | 0 |

| Iraqi b | 1 | 1 |

| Mixed White and Black Caribbean b | 0 | 2 |

| Mixed White and Black African b | 0 | 1 |

| Mixed White and Asian b | 1 | 0 |

| Not stated | 1 | 1 |

|

| ||

| Categories were grouped as shown by a and b superscripts for comparison Chi-square=

| ||

| Self-reported Oral Health | ||

| Poor | 6 | 52 |

| Fair | 20 | 26 |

| Good | 18 | 20 |

| Excellent | 6 | 1 |

|

| ||

| Chi-square=27.8 p<0.001

| ||

| Reason for Attendance | ||

| Routine | 16 | 55 |

| Emergency treatment | 24 | 25 |

| Other | 10 | 19 |

| Missing data | (1) | |

|

| ||

| Chi-square=9.1 p<0.05 | ||

The typical patient reported “poor” dental health (SC mode poor 52% RC mode fair 40%). There was a difference in self-reported dental health between the clinics. (Table 1)

There was a difference in self-reported attendance between the clinics. (SC mode ‘only when I need to’ 51%; RC mode ‘about every 6 months’ 66% (chi-square 47.5). There was also a significant difference in the reasons for attending 55% of the sedation patients attended only for emergency treatment while 48% of restorative patients attended for routine care (Table 1).

The majority of the patients in both clinics had never had sedation or a general anaesthetic for dental care before (SC 72% had not had a previous sedation or GA; RC 92% had not had a previous sedation or GA). Fifty-nine of 150 patients were either ASA II (55/150) or ASA III (4/150). There was no difference in the ASA between clinics although all four ASA III patients were in the SC.

Overall 47% patients in the SC (mean 15.7 years, range 1 to 30) and 26% patients in the Restorative clinic (mean 14.0 years, range 1 to 40) used tobacco. The typical patient self-reported consuming 3 units of alcohol (SC 3.7 mean, range 0–35; RC 2.1 units mean, range 0–14). Sixty-five percent of patients reporting not using any alcohol. Fifty-seven percent of those in the SC reported using alcohol versus only 16 percent of those in the RC (Fisher’s Exact Test, p<.0001).

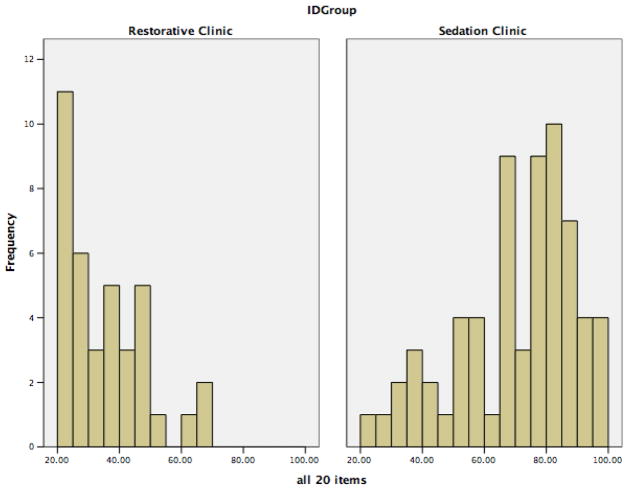

The total Dental Fear Survey score (DFS) for the two clinics was 69.8 (18.9 SD, 20–97 range) for the SC and 35.1 (13.6 SD, 20–68 range) for the RC. There was a difference in DFS score t=9.8. The distribution of the scores for the two clinics is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Dental Fear Survey Score by Clinic

The two clinics also differed in the same manner on each of the three subscores (t=11.2, 8.5, and 9.9 respectively).

Anticipation (SC Mean (SD) =9.8 (3.0); RC Mean (SD) =4.6 (1.8)

Specific Fears (SC Mean (SD) =42.0 (12.7); RC Mean (SD) =23.4 (9.4)

Physiology (SC Mean (SD) =17.7 (5.3); RC Mean (SD) =8.4 (3.8)

Table 2 gives the individual items in the DFS. The two clinics differed in the importance of various fears. Among the top five fears, the three items addressing the dental drill, overall fear and the physiological response to fear of a high heart rate were most important in the SC. In the RC, the three drill items also appeared in the top five but the overall fear and physiological response questions were rated lower. The only item where there was no significant difference between the two clinics was in taking impressions.

Table 2.

Frequencies of responses to individual items on the Dental Fear Survey by participants attending Sedation clinic (n=100) and Restorative clinic (n=50).

| Item | Participants attending Restorative clinic (n=50) | Participants attending Sedation clinic (n=100) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How much anxiety do each of the following cause you … | Not at all | A little | Somewhat | Much | Very much | Not at all | A little | Somewhat | Much | Very much | |

| Making an appointment for dentistry | 39 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 26 | 29 | 19 | 5 | 17 | Chi2=38.9, p<0.001 |

| Approaching the dentist’s surgery | 32 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 16 | 23 | 18 | 20 | 22 | Chi2=42.1, p<0.001 |

| Sitting in the waiting room | 24 | 17 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 17 | 16 | 21 | 23 | 22 | Chi2=36.3 p<0.001 |

| Being seated in the dental chair | 18 | 20 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 21 | 20 | 39 | Chi2=51.5, p<0.001 |

| The smell of the dentist’s surgery | 30 | 14 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 22 | 12 | 19 | 18 | 28 | Chi2=43.8, p<0.001 |

| Seeing the dentist walk in | 34 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 25 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 29 | Chi2=40.2, p<0.001 |

| Seeing the anaesthetic needle | 18 | 12 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 15 | 11 | 13 | 17 | 42 | Chi2=22.7, p<0.001 |

| Feeling the needle injected | 15 | 14 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 13 | 19 | 7 | 13 | 44 | Chi2=20.1, p<0.001 |

| Seeing the drill | 15 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 18 | 58 | Chi2=39.6, p<0.001 |

| Hearing the drill | 16 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 5 | 12 | 63 | Chi2=44.2, p<0.001 |

| Feeling the vibrations of the drill | 15 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 12 | 64 | Chi2=41.6, p<0.001 |

| Having your teeth cleaned | 25 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 13 | 14 | 16 | 20 | 27 | Chi2=35.4, p<0.001 |

| Having x-rays put in my mouth | 34 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 40 | 17 | 15 | 13 | 12 | Chi2=14.3, p<0.001 |

| Having models or impressions of my mouth | 23 | 12 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 33 | 18 | 15 | 9 | 16 | Chi2=5.0, ns |

| All things considered, how scared are you of having dentistry done ? | 19 | 16 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 15 | 66 | Chi2=80.2, p<0.001 |

| Never | Once or Twice | A few time | Often | Nearly every time | Never | Once or Twice | A few time | Often | Nearly every time | ||

| Has fear of dentistry ever caused you to put off making an appointment? | 44 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 41 | 42 | 0 | 15 | 0 | Chi2=31.4, p<0.001 |

| Has fear of dentistry ever caused you to cancel or not turn up for an appointment? | 13 | 18 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 16 | 18 | 14 | 35 | Chi2=30.0, p<0.001 |

The 5 items of the dental injection fear instrument were added to give a score from 5 to 25, where 25 indicates a maximal fear of dental injections. The mean score was 16.6 (7.0 SD 5–25 range) for the SC and 9.6 (4.3 5–19 range) RC. There were differences between the populations t=6.3. The individual item responses are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Frequencies of responses to individual items on the Fear of Injections scale by participants attending Sedation clinic (n=100) and Restorative clinic (n=50).

| Item | Participants attending Restorative clinic (n=50) | Participants attending Sedation clinic (n=100) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concerning dental injections I believe that … | Not at all true | A little true | Somewhat true | Very true | Absolutely true | Not at all true | A little true | Somewhat true | Very true | Absolutely true | |

| Nothing is as painful as a needle in my mouth | 22 | 11 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 17 | 11 | 24 | 13 | 32 | Chi2=28.0, p<0.001 |

| Seeing the needle is terrifying | 19 | 17 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 15 | 16 | 14 | 16 | 39 | Chi2=37.7, p<0.001 |

| Seeing the needle come closer to my mouth is scary | 17 | 18 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 15 | 11 | 14 | 14 | 41 | Chi2=32.4, p<0.001 |

| I don’t know why needles are so terrifying to me. They just are ! | 26 | 13 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 20 | 15 | 13 | 10 | 38 | Chi2=33.8, p<0.001 |

| Just the idea of the needle penetrating my body is terrifying | 24 | 14 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 26 | 14 | 16 | 9 | 35 | Chi2=22.2, p<0.001 |

The responses to the two questionnaires are highly correlated (R=0.53, p<0.001 for the SC and R=0.67, p<0.001 for the RC).

Cross sectional analyses

Scores on the DFS were dichotomised using the previously established cut-off of 37. When the fearful patients in each clinic were compared, the SC population is more likely to be male (44 v 19%, chi square=6.6, df 1, p=.01) and be more poorly educated (0 levels 65 v 24%, chi square=24.0, df 4, p<0.0001).

A logistic regression analysis was conducted where the type of clinic referral (SC v R) was examined relative to patient characteristics (sex, age, education, regular attendance, tobacco and alcohol use, mental health, and use of medications. The results show that patients who are fearful and have had a pattern of irregular attendance are 5.9 and 4.9 times respectively more likely have been referred to the SC (p<0.05). Other characteristics of the patients were not independently related to the referral site in this multivariable analysis.

Conclusions

A previous study of referrals to secondary care found that most were for sedation.13 These investigators found that three-of-10 of these patients opted for psychological treatment for their fears. Nevertheless very few psychological services are available for dentally anxious individuals in the UK or elsewhere. As a result, many avoid dentistry altogether, while others only agree to referral for dental treatment under sedation or general anaesthesia, which is in short supply and expensive. Increasing the availability of conjoint treatment with psychological interventions of proven efficacy addressing fears and sedation used to facilitate urgent care will increase access to dental services consequential improvements in oral health and general well being. The impact of oral ill health on general health and quality of life is established and is particularly marked in individuals with dental anxiety.14

Addressing the two objectives of the study, we determined that 62% of the Sedation Clinic patients had high dental fear (score over 37) 18% in the Restorative Clinic. There were significantly more high anxiety patients in the Sedation Clinic than in the Restorative clinic making the Sedation clinic an appropriate venue for research and clinical trials on the treatment of fearful dental patients. Participation in the study was high suggesting the patients are typical of those being referred by their general dental practitioner because they are too anxious to receive treatment in a normal setting.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by a grant from the Society for the Advancement of Anaesthesia in Dentistry (SAAD). We acknowledge the advice of Dr David Craig of the Kings College Dental Institute and Emeritus Professor Isaac Marks of the Institute of Psychiatry in carrying out this study and the assistance of the dental nurses in both sedation and restorative clinics. Thanks also to Brian Smith retired consultant in Restorative dentistry.

Contributor Information

Carole A Boyle, Department of Sedation and Special Care Dentistry, King’s College London Dental Institute at Guy’s, King’s College and St Thomas’ Hospitals, Floor 26, Tower Wing, London SE1 9RT, UK.

Tim Newton, King’s College London, Oral Health Services Research & Dental Public Health, King’s College Hospital, Caldecot Road, London SE5 9RW, UK.

Peter Milgrom, Department of Sedation and Special Care Dentistry, King’s College London Dental Institute at Guy’s, King’s College and St Thomas’ Hospitals, Floor 26, Tower Wing, London SE1 9RT, UK.

References

- 1.Nuttall NM, Bradnock G, White D, Morris J, Nunn J. Dental attendance in 1998 and implications for the future. Br Dent J. 2001 Feb 24;190(4):177–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith TA, Heaton LJ. Fear of dental care: are we making any progress? J Am Dent Assoc. 2003 Aug;134(8):1101–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGrath C, Bedi R. The association between dental anxiety and oral health-related quality of life in Britain. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:67–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berggren U. General and specific fears in referred and self-referred adult patients with extreme dental anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 1992 Jul;30(4):395–401. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(92)90051-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardie R, Ransford E, Zernik J. Dental patients’ perceptions in a multiethnic environment. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1995 Dec;23(12):77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holtzman JM, Berg RG, Mann J, Berkey DB. The relationship of age and gender to fear and anxiety in response to dental care. Spec Care Dentist. 1997 May-Jun;17(3):82–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1997.tb00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milgrom P, Mancl L, King B, Weinstein P. Origins of childhood dental fear. Behav Res Ther. 1995 Mar;33(3):313–9. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00042-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomar SL, Azevedo AB, Lawson R. Adult dental visits in California: successes and challenges. J Public Health Dent. 1998 Fall;58(4):275–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1998.tb03009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ragnarsson E. Dental fear and anxiety in an adult Icelandic population. Acta Odontol Scand. 1998 Apr;56(2):100–4. doi: 10.1080/00016359850136067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen EM, Girdler NM. Attitudes to conscious sedation in patients attending an emergency dental clinic. Prim Dent Care. 2005 Jan;12(1):27–32. doi: 10.1308/1355761052894149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milgrom P, Coldwell SE, Getz T, Ramsay DS, Weinstein P. Four dimensions of fear of dental injections. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128(6):756–766. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1997.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleinknecht RA, Thorndike RM, McGlynn FD, Harkavy J. Factor analysis of the dental fear survey with cross-validation. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984 Jan;108(1):59–61. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1984.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGoldrick P, Levitt J, deJongh A, Mason A, Evans D. Referrals to a secondary care dental clinic for anxious adult patients: implications for treatment. Brit Dent J. 2001;191:686–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen SM, Fiske J, Newton JT. The impact of dental anxiety on daily living. Brit Dent J. 2000 Oct 14;189(7):385–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]