Abstract

Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. suis is a fungus multiplying in the respiratory tract of pigs which occasionally is associated with interstitial pneumonia. Identification of Pneumocystis in tissue samples is considered difficult and there are only scarce data on its occurrence in European pigs. This investigation presents an in situ hybridization (ISH) procedure for identification of Pneumocystis spp. in paraffin wax embedded tissue samples and its application for labeling the agent in lung samples of pigs with interstitial pneumonia. Thirty-two out of 100 lung samples from pigs on Austrian farms were identified as positive, five of them with multiple, 12 with moderate and 15 with few organisms but Grocott’s methenamine silver staining demonstrated that only 20 cases were unequivocally positive for Pneumocystis carinii. In addition to interstitial pneumonia Pneumocystis-positive pigs were more frequently affected with granulomatous pneumonia than Pneumocystis-negative pigs. Frequently concurrent infections with different viral or bacterial lung pathogens were noted but there was no positive correlation between Pneumocystis- and PCV-2-infections. With other infections, no clear-cut differences between Pneumocystis-positive and Pneumocystis-negative animals were found. This study shows that Pneumocystis infections occur frequently in Austrian pigs with interstitial pneumonia. It remains to be shown which are the factors triggering severe multiplication and whether infection with Pneumocystis alone is able to induce lung disease in pigs.

Keywords: Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. suis, in situ hybridization, pigs, Austria

Introduction

Pneumocystis, a fungus in the phylum Ascomycota, is a frequent inhabitant of the lungs of many mammalian species [1]. In pigs, the agent is known as P. carinii f. sp. (forma specialis) suis [2], has been repeatedly found with and without lung disease or, sporadically in association with disease outbreaks [3-8]. Different diagnostic approaches have been used, ranging from histological detection to molecular identification by PCR and subsequent sequencing attempts. Some authors also applied immuno-histochemistry (IHC) or in situ hybridization (ISH) for specific localization of the organisms in tissue sections [4,6,9,10]. The majority of recent scientific publications on Pneumocystis in pigs are from Asia and South America [9-11] and with the exception of a recent prevalence study in slaughtered pigs from Portugal [12] and several earlier reports from Denmark [3,13], there is very little information on the European situation. The major objectives of this report were: (i) to establish a robust and sensitive ISH method for identification and localization of Pneumocystis organisms in lung tissue specimens, (ii) to apply this technique in comparison with the traditional Grocott’s methenamine-silver nitrate (GMS) staining for retrospective screening of porcine lung samples with interstitial pneumonia, and (iii) to correlate the presence or absence of Pneumocystis to the histological type of pneumonia and co-infections with other relevant pathogens of the respiratory tract.

Materials and methods

Samples

Formalin fixed and paraffin wax embedded tissue (PET) samples from lungs of 100 pigs originating from 99 different farms were used for the retrospective study. The common selection criterion was the histological diagnosis of an interstitial pneumonia. The pigs had been submitted for routine pathological investigation during the years 2007–2011 and of these, 92 had been euthanized and eight died spontaneously. To avoid investigating a series of samples from the same farm, one case was randomly chosen for study if there were multiple pigs from the same origin. The farms were located in the federal states of Upper Austria (59), Lower Austria (33), Styria (4), Burgenland (1), Vienna (1) and Salzburg (1). The investigated pigs were grouped, according to age, into suckling piglets (17), postweaned pigs (58), growers and finishers (24) and gilt (1). All lung samples were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and with GMS according to standard techniques and subjected to Pneumocystis-specific ISH.

In situ hybridization

An oligonucleotide probe with the potential to hybridize with all representatives of the genus Pneumocystis was designed after extensive homology studies using the Sci Ed Central software package (Scientific & Educational Software, Cary, NC, USA) on all available GenBank sequences of the 18S rRNA gene. This target had yielded very distinct and strong signals in previous ISH applications with other fungi [14]. A region of 40 bp was chosen as probe sequence, i.e., 5′-gga acc cga aga ctt tga ttt ctc ata aga tgc cga gcg a-3′. Subsequently, this sequence was submitted to Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST; http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) to search against GenBank sequences and to exclude unintentional cross-reactivity with other organisms. After probe synthesis and labeling of the 3′-end with digoxigenin (Microsynth AG, Balgach, Switzerland), ISH was carried out on PET samples based on a previously described protocol [15]. Briefly, proteolysis with proteinase K (2.5 μg/ml; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) in Tris-buffered saline for 30 min at 37°C. For hybridization, the slides were incubated overnight at 40° C with hybridization mixture and a final probe concentration of 20 ng/ml. The digoxigenin-labeled hybrids were detected by incubating the slides with anti-digoxigenin-alkaline phosphatase Fab fragments (1:200; Roche) for 1 h at room temperature. Visualization of the reaction was carried out using the color substrates 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-inodyl phosphate and 4-nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (Roche).

PET samples from a laboratory rat and a rabbit with morphologically and molecularly (PCR and sequencing) proven diagnoses of Pneumocystis pneumonia were used as positive controls in each run. In order to exclude unintended cross-hybridization with other organisms samples containing Aspergillus spp., Candida spp., Encephalitozoon cuniculi, Cryptosporidium baileyi, Entamoeba invadens, Giardia intestinalis, Histomonas meleagridis, Eimeria ssp., Monocercomonas colubrorum, Sarcocystis spp., Tetratrichomonas gallinarum, Trichomonas gallinae, Tritrichomonas foetus and Toxoplasma gondii were tested, and all were found to be negative.

Microscopic evaluation and assessment of co-infections

The evaluation of the slides was done by light microscopy and for the GMS and ISH methods the quantity of the microorganisms was assessed according to Jensen et al. [4] using the score + + + for multiple, + + for moderate and + for few organisms in the lung. H&E staining was used for assessment of the histological lung lesions.

The presence of viral and bacterial pathogens with potential relation to the pathological lung alterations had been tested in all or a proportion of the investigated lungs upon submission to laboratories (Table 1). These data were extracted from the files and considered in context with the Pneumocystis status of the animals.

Table 1.

Presence of viral and bacterial co-infections in the investigated lung samples.

| Pathogen | Pneumocystis positive | Pneumocystis negative | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCV-2l | 8/32 (25.0%) | 31/68 (45.6%) | 39/100 (39.0%) |

| PRRSV | |||

| Viral RNA2 | 1/6 (16.7%) | 0/33 (0.0%) | 1/39 (2.6%) |

| Antibodies3 | 5/14 (35.7%) | 12/33 (36.4%) | 17/47 (36.2%) |

| SIV4 | 1/8 (12.5%) | 12/27 (44.4%) | 13/35 (37.1%) |

| Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae 5 | 4/10 (40.0%) | 12/19 (63.2%) | 16/29 (55.2%) |

| Haemophilus parasuis 6,7 | 7/21 (33.3%) | 19/58 (32.8%) | 26/79 (32.9%) |

| Pasteurella multocida 7 | 2/19 (10.5%) | 12/55 (21.8%) | 14/74 (18.9%) |

| Bordetella bronchiseptica 7 | 2/19 (10.5%) | 6/55 (10.9%) | 8/74 (10.8%) |

| Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae 7 | 0/19 (0.0%) | 4/55 (7.2%) | 4/74 (5.4%) |

| Streptococcus suis 7 | 3/19 (15.8%) | 13/55 (23.6%) | 16/74 (21.6%) |

Results

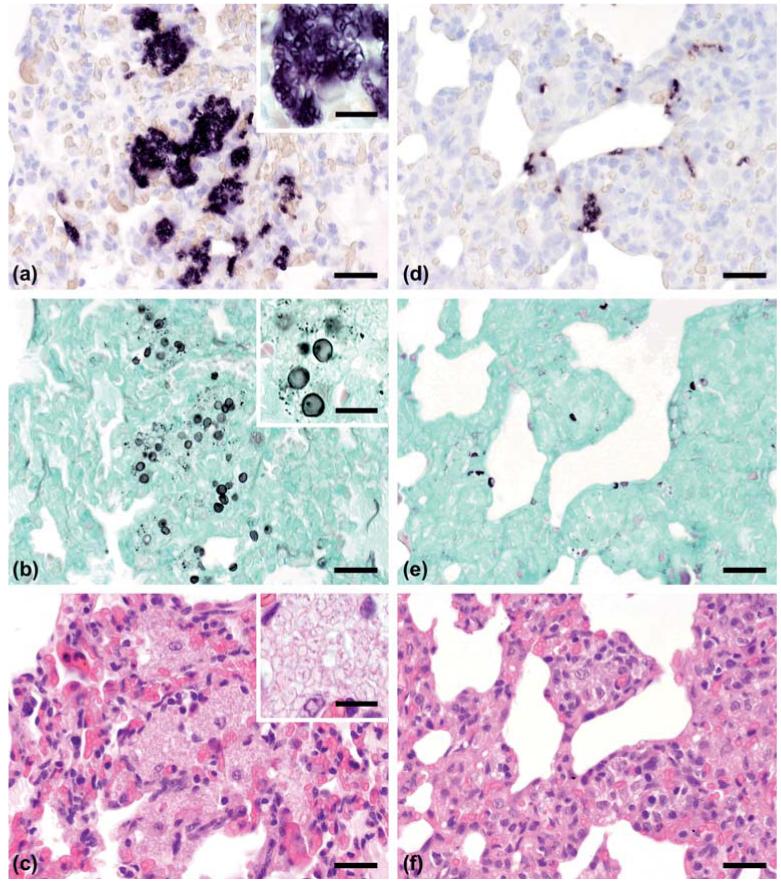

In the positive control, ISH identified numerous organisms within the alveoli which were characterized by a distinct purple to black signal, whereas in lung samples of 32 pigs, Pneumocystis were recognized by ISH, which included postweaned pigs (28) and growers (4). In four cases, multiple organisms (score: + + +) were present which caused an almost continuous lining of alveolar spaces over larger areas and frequently completely filling the alveoli (Fig. 1a). In 12 cases the Pneumocystis load was moderate (score: + +), characterized by either several larger clusters of organisms which could fill single alveoli or more diffuse distribution patterns with groups of organisms predominantly lining the alveolar surface (Fig. 1d). In cases with scores + + + and + + aggregates of Pneumocystis were also present in the bronchiolar lumina and the respiratory bronchioles, which seemed to be a preferred colonization site. Only a few Pneumocystis organisms (score: +) which were found in a few foci, on the surface of alveoli, singly or in small groups in 16 pigs. Generally, the entire organisms (both trophic forms and cysts) were stained by ISH, but the organism could be detected by GMS staining, in lower numbers and in only 20 of the 32 ISH-positive cases. While all the cases scored as + + + by ISH and 10 of the 12 cases scored as + + by ISH were also found positive by GMS staining (Figs. 1b and 1e), only five of the 16 cases with the ISH score + showed clearly identifiable Pneumocystis stages. By GMS only the cell walls of cyst stages were labeled.

Fig. 1.

(Left column): Case with strong colonization with Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. suis. Adjacent sections from the same lung area are shown in comparison after ISH, GMS and H&E stainings. (a) In situ hybridization (ISH) labels large colonies of numerous Pneumocystis developmental stages. Bar = 40 μm. Inset: High magnification does not allow us to unequivocally distinguish between cyst and trophozoite stages. Bar = 15 μm. (b) GMS labels exclusively cyst stages which are less frequent. Bar = 40 μm. Inset: High magnification shows the black stain of the cyst wall against a background of unstained trophozoites. Bar = 15 μm. (c) By H&E staining Pneumocystis colonies are recognizable by their ‘honeycomb’ appearance. Bar = 40 μm. Inset: High magnification does not allow us to unequivocally distinguish between cyst and trophozoite stages. Bar = 15 μm. (Right column): Case with moderate colonization with Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. suis. Adjacent sections from the same lung area are shown in comparison after ISH, GMS and H&E stainings. (d) ISH labels several small colonies of Pneumocystis developmental stages. Bar = 40 μm. (e) GMS labels only single cyst stages within these colonies. Bar = 40 μm. (f) By H&E staining Pneumocystis colonization is not convincingly recognizable. Bar = 40 μm. This Figure is reproduced in color in the online version of Medical Mycology.

In all 100 investigated cases, the histological analysis of H&E-stained lung tissue sections revealed interstitial pneumonias which were uniformly characterized by loss of type 1 pneumocytes and proliferation of type 2 pneumocytes, the presence of alveolar macrophages within the alveolar spaces, and infiltration of different amounts of mononuclear cells in the alveolar walls. The lesions were scored, according to distribution and severity as severe in 28 cases, moderate in 37 cases, or mild in 35 cases. This distribution pattern was similar in Pneumocystis-positive and Pneumocystis-negative cases. Additional lung lesions which were present in at least 10% of the cases are listed in Table 2. Sixty-five percent of the cases showed hyperplasia of bronchus associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) in context with bronchopneumonia. Comparatively few cases had fibrinous or fibrinous-hemorrhagic pneumonia (14%) or different stages of pleuritis (13%). These lesions were proportionally more frequent in cases without Pneumocystis. In contrast, granulomatous pneumonia occurred more frequently in Pneumocystis-positive lungs were multifocal infiltrates of histiocytes and occasionally multinucleated giant cells throughout the lung parenchyma were found. Efforts to unequivocally localize developmental stages of Pneumocystis in H&E slides were never successful in cases scored as ‘+’ and only exceptionally, in those that were ‘+ +’ by ISH (Fig. 1f). Only in cases scored ‘+ + +’, careful examination consistently revealed intraalveolar aggregates of Pneumocystis, generally recognizable by their ‘honeycomb’ appearance, which, however, were sometimes hardly distinguishable from edema fluid (Fig. 1c).

Table 2.

Relevant lung lesions and presence of Pneumocystis spores in the investigated lung samples categorized as Pneumocystis positive and Pneumocystis negative by in situ hybridization.

| Lesion | Pneumocystis positive | Pneumocystis negative | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interstitial pneumonia | 32 | 68 | 100 |

| Mild | 11 (34.4%) | 17 (25.0%) | 28 |

| Moderate | 10 (31.3%) | 27 (39.7%) | 37 |

| Severe | 11 (34.4%) | 24 (35.3%) | 35 |

| BALT hyperplasia and/or bronchopneumonia | 13 (40.6%) | 52 (76.5%) | 65 |

| Fibrinous or fibrinous- hemorrhagic pneumonia | 0 (0.0%) | 14 (20.6%) | 14 |

| Acute or chronic pleuritis | 2 (6.3%) | 11 (16.2%) | 13 |

| Granulomatous pneumonia | 10 (31.3%) | 6 (8.8%) | 16 |

| Positive GMS staining | 20 (62.5%) | 0 | 20 |

There was direct or indirect evidence for viral or bacterial infections with relevance for the respiratory tract in varying percentages of the investigated animals. In situ hybridization of inguinal lymph nodes revealed the presence of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV-2) in 25% of the Pneumocystis-positive cases and 45.6% of the Pneumocystis-negative cases. Antibodies to porcine respiratory and reproductive syndrome virus (PRRSV) were present in comparable percentages in cases with and without Pneumocystis colonization (35.7% vs. 36.4%), while the proportion of cases with antibodies to swine influenza virus (SIV) seemed to be higher in Pneumocystis-negative animals. Bacterial colonization (assessed with PCR for Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, with a combination of the results from PCR and cultivation for Haemophilus parasuis and with cultivation alone for the other bacteria) were also slightly more frequent in Pneumocystis-negative animals (Table 1).

Discussion

The ISH procedure described here proved to be a powerful tool for unambiguous detection of Pneumocystis in paraffin wax-embedded tissues and which will be widely applicable for post mortem examination of suspicious cases. Even the GMS staining method, frequently used for localizing fungal organisms in tissue sections, failed to identify sections with only few Pneumocystis cells. This finding is in line with previous observations [4,6] and emphasizes the importance of specific diagnostic assays. There are several studies applying IHC or ISH for the detection of Pneumocystis in humans and animals [4,9,10,16,17]. While some antibodies used for immunohistochemical demonstration of Pneumocystis in tissue sections were found to be only reactive with certain Pneumocystis species [4,10], the ISH probe described here has been predicted to identify all Pneumocystis species of which the respective nucleotide sequences have been deposited in publicly accessible databases. This prediction has – at least partly – been proven by the successful labeling of Pneumocystis derived from pig, rat and rabbit, which have been considered as three different species. The chromogenic ISH procedure which was developed, validated and applied in this work offers the possibility to correlating the presence of microorganisms with associated lesions. This aspect has to be appreciated as a considerable advantage compared to the frequently used PCR-based detection techniques which are usually unable to provide information on the abundance and tissue localization of pathogens.

In the present study almost one third (32%) of the investigated pigs were colonized with Pneumocystis. In comparison with two other prevalence studies in Europe [8,12], which both reported around 7% positive pigs, this percentage seems high and surprising at first sight and is more in line with prevalence data reported from Asia and South America [9,18]. However, the investigated material in this study was preselected for the presence of interstitial pneumonia, a fact which may easily explain the quite high colonization rate.

In contrast to other studies in which a supporting factor of PCV-2 infection for Pneumocystis propagation in the lung could not be excluded [19-21], our data argue against such a correlation. A higher percentage of Pneumocystis-negative cases were infected with PCV-2 than Pneumocystis-positive cases. While in humans the occurrence of Pneumocystis pneumonia and fulminant multiplication of the agent is clearly linked with immunosuppression (e.g., HIV infections) this association is less evident in different animal species, including pigs [2]. Moreover, the vast majority of Pneumocystis infections seem to lead to relatively benign colonization, and clinically manifest pneumonia is only an exception [11]. For example, a high proportion of laboratory rats is considered to be subclinically infected with Pneumocystis. The organism is generally eliminated from the lungs unless an immunosupressive condition is present [22]. A recent study demonstrated that the lungs of more than 80% of infants with sudden and unexpected death were colonized by Pneumocystis jirovecii which are easily detectable by both morphological and molecular techniques [23]. It is highly likely that in the present study that there was benign colonization in many cases. However, due to the presence of other infectious agents known to contribute to interstitial pneumonia it is impossible to judge the extent to which each of the infectious agents contributed to the observed pathologic changes. However, there seemed to be a general tendency that concurrent viral and bacterial infections were less frequent in Pneumocystis-positive cases than in Pneumocystis-negative cases. This observation differs from a similar study from Korea where the incidence for P. carinii infection was higher in virally (PRRSV and PCV-2)-infected pigs [9]. Also certain histological lesions, indicative of infections with Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and a number of other bacteria, such as BALT hyperplasia, broncho-pneumonia, fibrinous pneumonia, or pleuritis were more frequently present in Pneumocystis-negative lungs. In contrast, granulomatous inflammation was more often found in Pneumocystis-positive cases. This observation is in line with other reports that colonization with Pneumocystis is predominantly associated with infiltration of macrophages [4,6]. Generally, it remains to be shown which factors trigger severe multiplication and whether single infection with Pneumocystis without the presence of other infectious agents is able to induce lung disease in pigs.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Karin Fragner and Klaus Bittermann for excellent technical support. This work was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) grant P20926.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and the writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Aliouat-Denis C, Chabé M, Demanche C, et al. Pneumocystis species, co-evolution and pathogenic power. Infect Genet Evol. 2008;8:708–726. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chabé M, Aliouat-Denis C, Delhaes L, et al. Pneumocystis: From a doubtful unique entity to a group of highly diversified fungal species. FEMS Yeast Res. 2011;11:2–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bille-Hansen V, Jorsal SE, Henriksen SA, Settnes OP. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in Danish piglets. Vet Rec. 1990;127:407–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen TK, Boye M, Bille-Hansen V. Application of fluorescent in situ hybridization for specific diagnosis of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in foals and pigs. Vet Pathol. 2001;38:269–274. doi: 10.1354/vp.38-3-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kondo H, Taguchi M, Abe N, et al. Pathological changes in epidemic porcine Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. J Comp Pathol. 1993;108:261–268. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9975(08)80289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramos Vara JA. Characterization of natural occurring Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in pigs by histopathology, electron microscopy, in situ hybridization and PCR amplification. Histol Histopathol. 1998;13:129–136. doi: 10.14670/HH-13.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seibold HR, Munnell JF. Pneumocystis carinii in a pig. Vet Pathol. 1977;14:89–91. doi: 10.1177/030098587701400111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Settnes OP, Henriksen SA. Pneumocystis carinii in large domestic animals in Denmark. A preliminary report. Acta Vet Scand. 1989;30:437–440. doi: 10.1186/BF03548020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim KS, Jung JY, Kim JH, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of pulmonary pneumocystosis and concurrent infections in pigs in Jeju Island, Korea. J Vet Sci. 2011;12:15–19. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2011.12.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kondo H, Hikita M, Ito M, Kadota K. Immunohistochemical study of Pneumocystis carinii infection in pigs: evaluation of Pneumocystis pneumonia and a retrospective investigation. Vet Rec. 2000;147:544–549. doi: 10.1136/vr.147.19.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanches EMC, Ferreiro L, Borba MR, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of Pneumocystis from pig lungs obtained from slaughterhouses in southern and midwestern regions of Brazil. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec. 2011;63:1154–1159. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esgalhado R, Esteves F, Antunes F, Matos O. Study of the epidemiology of Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. suis in abattoir swine in Portugal. Med Mycol. 2012;51:66–71. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.700123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Settnes OP, Bille-Hansen V, Jorsal SE, Henriksen SA. The piglet as a potential model of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. J Protozool. 1991;38:140–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayden RT, Qian X, Roberts GD, Lloyd RV. In situ hybridization for the identification of yeast-like organisms in tissue section. Diagnostic Mol Pathol. 2001;10:15–23. doi: 10.1097/00019606-200103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chvala S, Fragner K, Hackl R, Hess M, Weissenböck H. Cryptosporidium infection in domestic geese (Anser anser f. domestica) detected by in-situ hybridization. J Comp Pathol. 2006;134:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J, Yu JR, Hong ST, Park CS. Detection of Pneumocystis carinii by in situ hybridization in the lungs of immunosuppressed rats. Korean J Parasitol. 1996;34:177–184. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1996.34.3.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi M,, Urata T,, Ikezoe T,, et al. Simple detection of the S ribosomal RNA of Pneumocystis carinii using in situ hybridisation. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49:712–716. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.9.712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanches EMC, Pescador C, Rozza D, et al. Detection of Pneumocystis spp. in lung samples from pigs in Brazil. Med Mycol. 2007;45:395–399. doi: 10.1080/13693780701385876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borba MR, Sanches EMC, Corrêa AMR, et al. Immunohistochemical and ultra-structural detection of Pneumocystis in wild boars (Sus scrofa) co-infected with porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) in Southern Brazil. Med Mycol. 2011;49:172–175. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.510540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanches EMC, Borba MR, Spanamberg A, et al. Co-infection of Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. suis and porcine circovirus-2 (PCV2) in pig lungs obtained from slaughterhouses in southern and midwestern regions of Brazil. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2006;53:92–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2006.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato K, Shibahara T, Ishikawa Y, Kondo H, Kubo M, Kadota K. Evidence of Porcine Circovirus infection in pigs with wasting disease syndrome from 1985 to 1999 in Hokkaido, Japan. J Vet Med Sci. 2000;62:627–633. doi: 10.1292/jvms.62.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armstrong MY, Smith AL, Richards FF. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in the rat model. J Protozool. 1991;38:136–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vargas SL, Ponce CA, Gallo M, et al. Near-universal prevalence of Pneumocystis and associated increase in mucus in the lungs of infants with sudden unexpected death. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:171–179. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosell C, Segales J, Plana-Duran J, et al. Pathological, immunohistochemical, and in-situ hybridization studies of natural cases of postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome (PMWS) in pigs. J Comp Pathol. 1999;120:59–78. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.1998.0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balka G, Hornyák A, Bálint A, et al. Genetic diversity of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus strains circulating in Hungarian swine herds. Vet Microbiol. 2008;127:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurth KT, Hsu T, Snook ER, et al. Use of a Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae nested polymerase chain reaction test to determine the optimal sampling sites in swine. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2002;14:463–469. doi: 10.1177/104063870201400603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliveira S, Galina L, Pijoan C. Development of a PCR test to diagnose Haemophilus parasuis infections. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2001;13:495–501. doi: 10.1177/104063870101300607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]