Abstract

APOBEC3A and APOBEC3G are DNA cytosine deaminases with biological functions in foreign DNA and retrovirus restriction, respectively. APOBEC3A has an intrinsic preference for cytosine preceded by thymine (5′-TC) in single-stranded DNA substrates, whereas APOBEC3G prefers the target cytosine to be preceded by another cytosine (5′-CC). To determine the amino acids responsible for these strong dinucleotide preferences, we analyzed a series of chimeras in which putative DNA binding loop regions of APOBEC3G were replaced with the corresponding regions from APOBEC3A. Loop 3 replacement enhanced APOBEC3G catalytic activity but did not alter its intrinsic 5′-CC dinucleotide substrate preference. Loop 7 replacement caused APOBEC3G to become APOBEC3A-like and strongly prefer 5′-TC substrates. Simultaneous loop 3/7 replacement resulted in a hyperactive APOBEC3G variant that also preferred 5′-TC dinucleotides. Single amino acid exchanges revealed D317 as a critical determinant of dinucleotide substrate specificity. Multi-copy explicitly solvated all-atom molecular dynamics simulations suggested a model in which D317 acts as a helix-capping residue by constraining the mobility of loop 7, forming a novel binding pocket that favorably accommodates cytosine. All catalytically active APOBEC3G variants, regardless of dinucleotide preference, retained HIV-1 restriction activity. These data support a model in which the loop 7 region governs the selection of local dinucleotide substrates for deamination but is unlikely to be part of the higher level targeting mechanisms that direct these enzymes to biological substrates such as HIV-1 cDNA.

Keywords: APOBEC3A, APOBEC3G, DNA cytosine deamination, HIV-1 restriction, Local dinucleotide target selection

Introduction

Human cells have the capacity to express up to nine enzymes with DNA cytosine to uracil (C-to-U) deaminase activity. Activation-induced deaminase (AID) deaminates immunoglobulin gene variable and switch region DNA cytosines to initiate somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination, respectively1,2. Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing protein catalytic subunit 1 (APOBEC1) edits RNA cytosines, but it is also a potent DNA deaminase that may have biological roles in suppressing retroelement replication3–9. Similarly, numerous studies combine to support a model in which the seven APOBEC3 (A3) enzymes have overlapping functions as innate immune effectors that prevent the replication of a broad number of endogenous and exogenous DNA-based substrates10–14. For instance, many retroviruses including HIV-1 are susceptible to restriction by one or more of the A3s and, under some circumstances, single- and double-stranded DNA viruses may also be targeted6,15–33.

Hundreds of studies over the past decade have shed light on the mechanism of HIV-1 restriction by APOBEC3G (A3G)10–13. Current models posit that cytoplasmic A3G binds RNA and thereby associates with the viral protein Gag to preferentially access the cores of assembling viral particles. Then, in a Trojan horse type mechanism, encapsidated A3G inhibits virus replication in a susceptible target cell by physically interfering with the progression of reverse transcription and by deaminating nascent viral cDNA cytosines to uracils. As reverse transcription proceeds to completion, viral cDNA uracils template the insertion of genomic-strand adenines. This series of events explains the well-established phenomenon of G-to-A hypermutation. A3G is the only family member with a strong intrinsic preference for 5′-CC dinucleotides, and this property accounts for a significant fraction of observed HIV-1 hypermutations in vivo (i.e., 5′-GG-to-AG mutations)15,34,35. APOBEC3D (A3D), APOBEC3F (A3F), and APOBEC3H (A3H) strongly prefer 5′-TC substrates, and these enzymes combine to explain the remaining fraction of hypermutations (i.e., 5′-GA-to-AA mutations36,37).

Additional studies have revealed that APOBEC3A (A3A) and several other family members (but not A3G) have the capacity to trigger the clearance of naked foreign DNA from cells by a C-to-U deamination mechanism38–41. In vivo, foreign DNA may come in a variety of forms, such as nuclear DNA from apoptotic or necrotic cells, mitochondrial DNA from organelle recycling, or microbial DNA from bacteria, viruses, and/or fungi. However, in cell culture, foreign DNA restriction can be modelled by transfecting plasmid DNA produced in E. coli into human cells and quantifying subsequent A3-dependent hypermutation and degradation38,41. A3A is the most effective foreign DNA restriction enzyme by this assay and, like several enzymes described above (but not A3G), it strongly prefers 5′-TC single-stranded DNA substrates23,38,41,42. A biological role in foreign DNA restriction is concordant with the fact that A3A is expressed exclusively in myeloid lineage cells such as macrophages, it is the most interferon-inducible of all of the human A3 family members, and it can accommodate both cytosine and 5-methyl-cytosine single-stranded DNA substrates23,38,41,43–45. Thus, A3A appears specialized for biological function in foreign DNA clearance, although a role in virus restriction in myeloid cell types is also plausible46,47.

The seven human A3 proteins can be divided into three phylogenetic subgroups based on conserved amino acids present in each enzyme’s catalytically active zinc-coordinating domain48,49. A3A, A3B, and A3G have Z1-type active site domains, A3C, A3D, and A3F have Z2-type active site domains, and A3H is the lone enzyme with a Z3-type active site domain. AID and APOBEC1 comprise separate phylogenetic groups. Chimeras and mutants have been used to gain insights into the amino acids that govern the intrinsic dinucleotide specificity of several of these enzymes. Original studies by Langlois and coworkers created A3F mutants with altered dinucleotide deamination preferences and thereby implicated a number of amino acids including loop 7 residues50. Kohli and coworkers grafted A3F and A3G loop 7 residues into AID and reported a corresponding transfer of dinucleotide deamination preferences51. Carpenter and coworkers and Wang and coworkers also implicated loop 7 by grafting sequences from A3s into AID52,53. Additionally, Kohli and coworkers (in a subsequent paper) and Wang and coworkers showed that the resulting AID chimeras were functional for somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination, with correspondingly altered mutational patterns (i.e., 5′-purine-C preference of wildtype AID had become 5′-CC or 5′-TC)53,54. These local substrate targeting data are concordant with a crystal structure of the distantly related deaminase TadA bound to its tRNA substrate, in which the analogous loop region interacts with the nucleotide immediately 5′ of the target adenosine55,56.

Here, we take advantage of the fact that A3A and the active domain of A3G are closely related, belonging to the same phylogenetic Z1 subgroup, and yet still elicit distinct local dinucleotide preferences, preferring 5′-TC and 5′-CC, respectively. This differential substrate specificity was used as a phenotype to determine the amino acids responsible and, further, to ask whether local substrate preferences may be linked to biological activity. Guided by high-resolution structures of the A3G catalytic domain and a predicted structure of A3A, we constructed a series of A3G chimeras in which putative DNA binding loops were replaced with the corresponding regions of A3A. Biochemical activity assays and HIV-1 restriction experiments combined to show that loops 1 and 3 influence enzymatic activity and loop 7 alone governs 5′-nucleotide selection relative to the cytosine targeted for DNA deamination. Replacing a single amino acid in A3G, D317, with the corresponding residue in A3A, Y132, was sufficient to endow 5′-TC DNA deamination activity. In addition, regardless of local dinucleotide preference, all of the enzymatically active A3G mutants showed potent HIV-1 restriction activity indicating that the precise amino acid composition of these loop regions is dispensable for engaging physiological targets.

Results

Structure-guided construction of A3G chimeras with loops from A3A

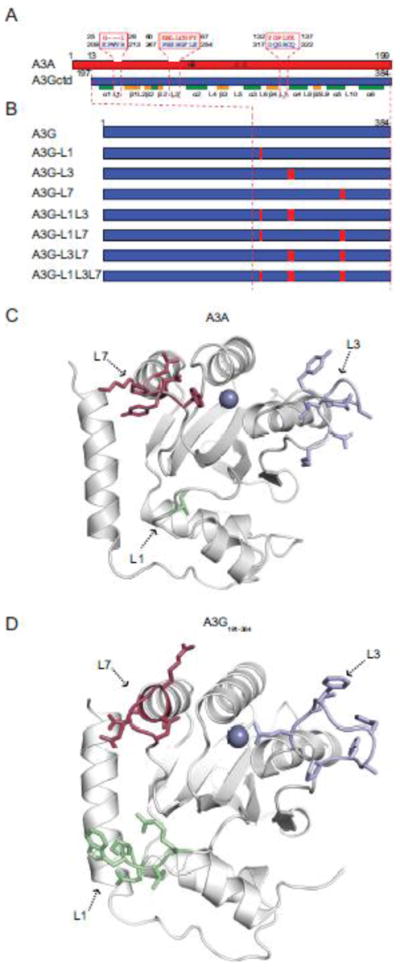

To better understand the differential dinucleotide substrate specificities of A3G and A3A, ClustalW57 was used to align the amino acid sequences of the catalytic domain of A3G (residues 197–384) and wildtype A3A (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S1). As noted previously40,58,59, the greatest divergence between these two Z1-type DNA deaminases is concentrated in the putative DNA binding loop regions, here named loops 1, 3, and 7 to correspond with regions located between conserved α-helices and β-strands (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S1). The Loop 7 region of A3G has been strongly implicated in dinucleotide substrate selectivity (see Introduction), but the precise single amino acid determinants have yet to be determined and reconciled with structural information.

Fig. 1. Alignment and schematics of A3A, A3G, and A3G loop mutants.

(a) A schematic of A3A (red) and A3G C-terminal domain (ctd; blue) showing loop 1, loop 3, and loop 7 amino acids. A3G structural elements are labelled below for reference.

(b) Schematics of A3G and derivatives made by replacing loop regions with the structurally corresponding residues from A3A.

(c) Ribbon schematic of an NMR structure of A3A61 showing loop 1 in green, loop 3 in blue, and loop 7 in red. The active site zinc is depicted as a purple sphere.

(d) Ribbon schematic of a crystal structure of A3G-197-38060 showing loop 1 in green, loop 3 in blue, and loop 7 in red. The active site zinc is depicted as a purple sphere.

Based on these alignments, we constructed a complete series of chimeras, in which loops 1, 3, and 7 of the A3G catalytic domain were replaced with the corresponding loop regions from A3A (loop sequences in Fig. 1a; construct schematics in Fig. 1b). DNA sequencing and immunoblotting were used to confirm the integrity of all constructs (below). Loops 1, 3, and 7 are located adjacent to the active site of A3G60 and A3A61 (colored green, blue, and red, respectively; Fig. 1c and d).

Dinucleotide deamination preferences of A3G loop chimeras in cell extracts

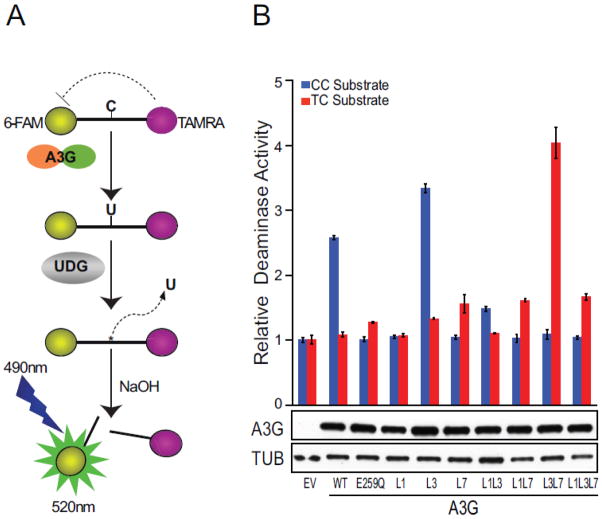

Fluorescence-based biochemical assays provide robust measures of DNA deaminase activity41,62,63 (schematic in Fig. 2a). The activity of A3G and its loop replacement derivatives was quantified by expressing each construct in 293 cells, preparing soluble lysates, and incubating each lysate with 5′-CC or 5′-TC containing single-stranded DNA substrates (primary deamination target underlined hereon; Fig. 2b). DNA cytosine deamination followed by uracil excision and hydrolytic cleavage results in the release of the fluorescent 6-FAM group from the TAMRA quench. Previous studies have shown that A3G has an intrinsic preference for 5′-CC, whereas A3A prefers 5′-TC15,23,34,35,38,41,42. A3G catalytic activity was severely compromised when the analogous region from A3A was used to replace loop 1, resembling the phenotype of the catalytic mutant E259Q. In contrast, replacement of A3G loop 3 with the homologous A3A loop caused a consistent and significant increase in 5′-CC deaminase activity. Concordant with prior literature (see Introduction), placing A3A loop 7 into A3G changed the enzyme’s substrate preference to 5′-TC, albeit with lower overall activity. Since loop 3 from A3A made A3G more active and loop 7 altered its substrate specificity, we assessed the activity of the combined loop mutant. Interestingly, this double loop mutant had both new properties, showing enhanced 5′-TC deamination activity and undetectable 5′-CC editing activity (Fig. 2b). Immunoblots showed that all of A3G loop chimeras expressed similarly and that observed activity and substrate differences are likely due to the intrinsic properties of the proteins themselves (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2. DNA deaminase activity of A3G loop constructs in 293 cell extracts.

(a) Schematic of the fluorescence-based ssDNA cytosine deamination assay. A3G deaminates C-to-U, UDG excises the U, NaOH breaks the phosphodiester backbone, and the 5′ fluorophore 6-FAM releases from the 3′ quench TAMRA. The resulting fluorescent read-out provides a direct measure of DNA deaminase activity because UDG and NaOH are provided in excess.

(b) A histogram reporting the relative activity of A3G and loop replacement derivatives on 5′-CC or 5′-TC single-stranded DNA substrates (blue and red bars, respectively). Immunoblots of A3G (anti-V5) and tubulin (anti-TUB) in the corresponding 293 lysates are shown below. Data are mean +/− standard deviation of three independent experiments.

HIV-1 restriction by A3G loop mutants

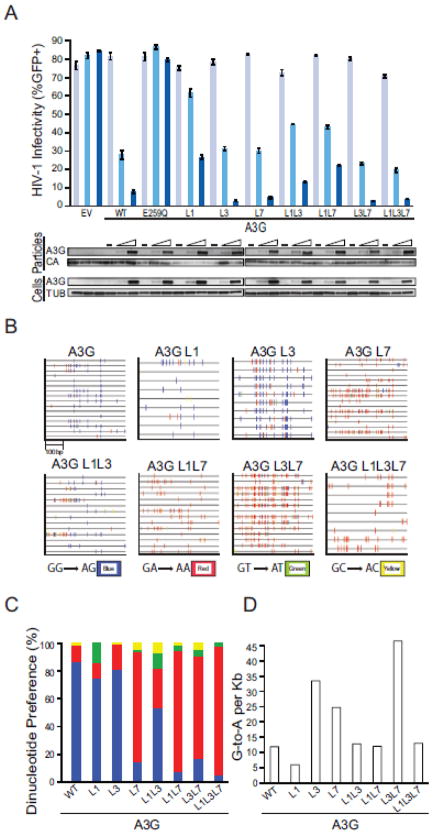

Multiple studies have shown that DNA deamination activity is required for full levels of HIV-1 restriction by human A3G16,64–66. Single-cycle virus infectivity assays were therefore done in the presence of wildtype A3G or each loop mutant to ask whether altering the local deamination preference had an impact on the restriction activity of this enzyme. Immunoblotting showed that each of the V5-tagged constructs was similarly expressed in 293 cells and packaged into viral particles (Fig. 3a). Low ratios of A3G to proviral DNA were used to minimize potential deaminase-independent effects67. For instance, transfection of 50 and 200 ng of wildtype A3G caused intermediate (67%) and strong (91%) levels of restriction, respectively, whereas equivalent amounts of the E259Q catalytic mutant had little effect. Interestingly, all of the loop mutants showed significant restriction activity ranging from modest (loop 1 and loop 1/7 constructs) to intermediate (loop 1/3) to near wildtype levels (loop 3, loop 7, loop 3/7, and loop 1/3/7 constructs) (Fig. 3a). These restriction capacities correlated with deaminase activity, as determined above using cell extracts and single-stranded DNA substrates. However, it is notable that these restriction assays appeared to provide more sensitive read-outs than cell extract activity assays because even the loop 1 construct was partially active and its activity could be boosted by combining it with loop 3.

Fig. 3. HIV restriction and hypermutation capabilities of A3G loop replacement constructs.

(a) A histogram reporting the average infectivity of HIV-GFP produced in the presence of 0, 50 or 200 ng of transfected plasmid expressing empty vector (EV), wildtype A3G (WT), catalytic mutant A3G (E259Q), or the indicated A3G loop replacements (n=3; mean and SD shown for each condition). Representative immunoblots are shown below for A3G (anti-V5) and tubulin (anti-TUB) expression in cell lysates and A3G (anti-V5) and Gag (anti-p24) in viral particles. Data are mean +/− standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(b) G-to-A mutation profiles of HIV proviruses from the infectivity experiment shown in ‘A’. Each tick represents a single G-to-A mutation, and colors depict dinucleotide context.

(c) A histogram summarizing the fraction of G-to-A mutations observed within each dinucleotide context (data from ‘b’).

(d) A histogram summarizing the observed G-to-A mutation frequency of the indicated constructs (data from ‘b’).

Next, we asked whether the local dinucleotide deamination preferences delineated using cell extracts would translate into similarly altered HIV-1 proviral DNA hypermutation patterns. This was done by PCR amplifying, cloning, and sequencing a 470 bp region of the GFP cassette from the integrated viruses that resulted from each single-round infectivity experiment. As expected from prior studies (see Introduction), the vast majority of viral plus strand mutations caused by A3G were 5′-GG-to-AG (87%) and a minority were 5′-GA-to-AA (12%) (Fig. 3b and c). Loop 1, loop 3, and loop 1/3 constructs also yielded over 50% 5′-GG-to-AG mutations. However, in stark contrast, loop 7, loop 1/7, loop 3/7, and loop 1/3/7 constructs all inflicted over 70% 5′-GA-to-AA mutations (Fig. 3b and c). The average G-to-A mutation loads were also interesting with a minimum of 6 mutations per kilobase (loop 1 construct) and a maximum of 46 mutations per kilobase (loop 3/7 construct), in comparison to wildtype A3G at 12 mutations per kilobase (Fig. 3d). Overall, these data confirm and extend prior studies by unambiguously demonstrating that loop 7 alone is responsible for selecting the 5′-base relative to the target cytosine. Our studies additionally show that DNA deaminase activity is influenced by loops 1 and 3 with negative and positive effects, respectively.

Activity of A3G loop 7 single amino acid substitution mutants

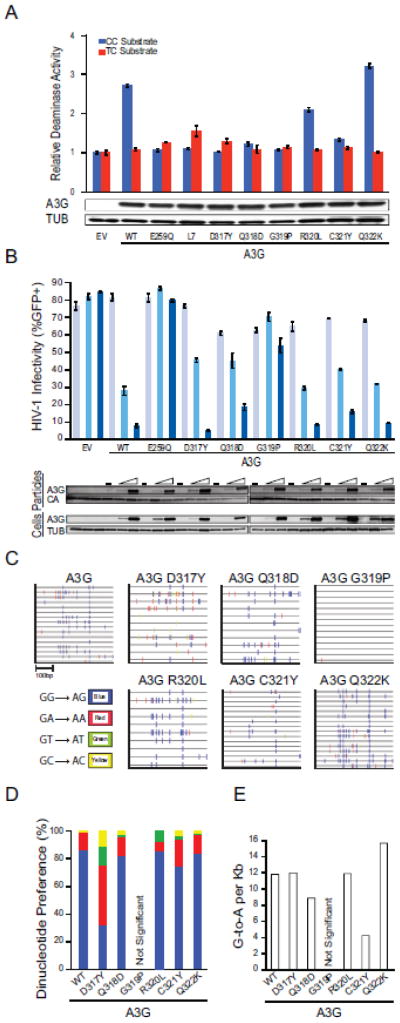

To further delineate the intrinsic determinants of dinucleotide selection, the six amino acids that differ between A3G and A3A in loop 7 were replaced individually. The resulting A3G constructs were expressed in 293 cells and lysates were prepared and used in a triplicate series of fluorescence-based activity assays as described above. Changing A3G D317 into the corresponding residue of A3A (Y132) proved particularly informative, as this substitution was the only one to cause A3G to adopt a more A3A-like 5′-TC preference (Fig. 4a). In comparison, four of the single amino acid substitution derivatives retained the intrinsic 5′-CC preference of wildtype A3G (Q318D, R320L, C321Y, Q322K) and one had no activity above background (G319P). Similar results were obtained by replacing individual loop 7 residues in the context of the hyperactive A3G loop 3 construct (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Fig. 4. Activities of A3G loop 7 single amino acid substitution mutants.

(a) A histogram reporting the relative activity of A3G and the indicated amino acid substitution mutants on 5′-CC or 5′-TC single-stranded DNA substrates (blue and red bars, respectively). Immunoblots of A3G (anti-V5) and tubulin (anti-TUB) in the corresponding 293 lysates are shown below. Data are mean +/- standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(b) A histogram reporting the average infectivity of HIV-GFP produced in the presence of 0, 50 or 200 ng of transfected plasmid expressing empty vector (EV), wildtype A3G (WT), catalytic mutant A3G (E259Q), A3G loop 7, or the indicated loop 7 amino acid substitution mutants (n=3; mean and SD shown for each condition). Representative immunoblots are shown below for A3G (anti-V5) and tubulin (anti-TUB) expression in cell lysates and A3G (anti-V5) and Gag (anti-p24) in viral particles. WT and D317Y data are the same as those in Fig. 4 and shown again here for comparison. Data are mean +/− standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(c) G-to-A mutation profiles of HIV proviruses from the infectivity experiment shown in ‘B’. Each tick represents a single G-to-A mutation, and colors depict dinucleotide context.

(d) A histogram summarizing the fraction of G-to-A mutations observed within each dinucleotide context (data from ‘c’).

(e) A histogram summarizing the observed G-to-A mutation frequency of the indicated constructs (data from ‘c’).

The importance of D317 for 5′-CC targeting was further tested through a series of HIV restriction and hypermutation experiments. As above for the whole loop constructs, all of the single amino acid substitution mutants were expressed and packaged similarly into viral particles (Fig. 4b). Moreover, apart from the inactive G319P construct, all of the proteins inhibited HIV-GFP infectivity similar to wildtype A3G (Fig. 4b). Viral DNA that had been produced in the presence of each of these constructs showed additional evidence for altered dinucleotide targeting preferences (Fig. 4c). Again, wildtype A3G and four of the mutant derivatives elicited less than 18% 5′-TC-to-TT mutations, which are reflected on the viral genomic strand as 5′-GA-to-AA mutations. In contrast, the D317Y construct inflicted over twice as many of this type of mutation (43%) (Fig. 4d). The lower activity of this single amino acid substitution mutant and incompletely transformed intrinsic dinucleotide preference in comparison to the entire loop 7 construct indicate that both the identity and the topology of other loop 7 amino acid residues are also contributing factors (compare dinucleotide hypermutation patterns in Figs. 3 and 4).

Insertion of other aromatic amino acids at A3G position 317 also skews deamination toward 5′-TC containing single-stranded DNA substrates

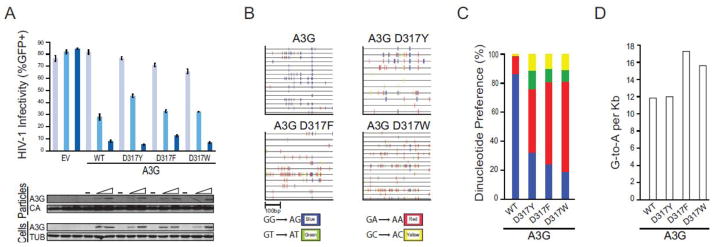

We next used HIV restriction and hypermutation experiments to test whether other aromatic amino acid substitutions at position 317 would also favor 5′-TC deamination. All of the constructs were expressed and packaged similarly and all inhibited the replication of Vif-deficient HIV-1 (Fig. 5a). Interestingly, each aromatic amino acid substitution construct showed a strong tendency for 5′-GA-to-AA hypermutation (Fig. 5b). The D317W construct in particular yielded a higher fraction of 5′-GA-to-AA hypermutations in comparison to the original D317Y construct, 60% versus 40%, respectively, suggesting that the larger aromatic amino acid may be even more favourable for 5′-TC deamination (Fig. 5c). This tendency also correlated with a slightly increased number of G-to-A mutations per kilobase (Fig. 5d). In terms of natural amino acid variation, it is important to note that human A3A and A3B have a tyrosine and other 5′-TC preferring deaminases, A3C, A3D, and A3F, have a phenylalanine at this position.

Fig. 5. Activities of A3G derivatives with aromatic amino acids at position 317.

(a) A histogram reporting the average infectivity of HIV-GFP produced in the presence of 0, 50 or 200 ng of transfected plasmid expressing empty vector (EV), wildtype A3G (WT), or the indicated amino acid substitution mutant (n=3; mean and SD shown for each condition). Representative immunoblots are shown below for A3G (anti-V5) and tubulin (anti-TUB) expression in cell lysates and A3G (anti-V5) and Gag (anti-p24) in viral particles. Data are mean +/− standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(b) G-to-A mutation profiles of HIV proviruses from the infectivity experiment shown in ‘A’. Each tick represents a single G-to-A mutation, and colors depict dinucleotide context.

(c) A histogram summarizing the fraction of G-to-A mutations observed within each dinucleotide context (data from ‘b’).

(d) A histogram summarizing the observed G-to-A mutation frequency of the indicated constructs (data from ‘b’).

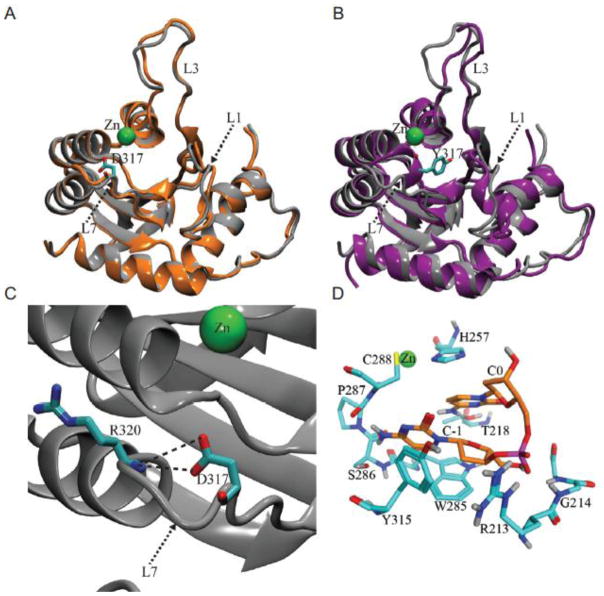

Structural model for local dinucleotide selection

To investigate the effect of D317Y on A3G structure, we performed a series of all-atom explicit-solvent MD simulations. The overall structure of wildtype A3G was well maintained throughout the entire duration of each MD simulation (Supplementary Fig. S3). Interestingly, in two separate MD experiments, the D317 side chain formed a persistent hydrogen bond with the R320 backbone (Fig. 6). This interaction creates an α-helix cap, known to stabilize α-helices in other proteins68–70. In contrast, this helical cap was unable to form in MD simulations of A3G D317Y. Instead, a local refolding event occurred in which the loop 7 region adopts a conformation that partly occludes the active site (Fig. 6b). Additionally, full or partial formation of a new 2-fold α-helix occurred in the loop 1 region during two separate MD simulations of A3G D317Y.

Fig. 6. Structural model for 5′-CC dinucleotide selection by A3G.

(a) Ribbon schematics of the wildtype A3G catalytic domain structure obtained from MD simulations of the apo system. The initial structure (gray) and the final snapshot (orange) of a 150 ns MD simulation are shown superimposed. Zinc is shown as a green sphere. D317 is depicted in stick representation, with carbon atoms in cyan and oxygen atoms in red.

(b) Ribbon schematics of A3G D317Y catalytic domain structure obtained in MD simulations of the apo system. The initial structure (gray) and the final snapshot (purple) of a 150 ns MD simulation are shown superimposed. Zinc is shown as a green sphere. Y317 is depicted in stick representation, with carbon atoms in cyan and oxygen atoms in red.

(c) A close-up view of the persistent helix-capping interaction between D317 and the backbone of R320 observed in MD simulations of the wildtype A3G in its apo form.

(d) Binding pose of a 5′-CC dinucleotide in the active site of wildtype A3G, based upon the final snapshot of a 400 ns MD simulation of 5′-CC-bound A3G. Nitrogen, oxygen and phosphorus atoms are depicted as sticks in blue, red and violet colors, respectively. Carbon atoms of the dinucleotide and the amino acids are shown in orange and cyan, respectively. Only the polar hydrogen atoms are depicted in light gray for clarity.

To further investigate and structurally rationalize the unique preference of A3G for 5′-CC substrates, we combined information from A3G catalytic domain crystal structure (3IR2), which lacks an active site ligand, and from a mouse cytidine deaminase crystal structure (2FR6), with the nucleobase positioned in the active site (Materials and Methods). The MD simulations starting from the modelled cytidine-bound A3G structure suggested that A3G has two distinct cytidine binding sites: one in a pocket near the catalytic glutamate (E259) and another in an adjacent pocket near C321 and other loop 7 residues (Supplementary Fig. S4). These preferred binding sites are consistent with the target cytosine needing to be positioned within the active site for deamination and the upstream cytosine needing to be accommodated nearby.

Combining the two preferred binding poses of cytidine, a 5′-CC dinucleotide was modelled into an MD-generated A3G catalytic domain structure. MD simulations of the 5′-CC-bound A3G catalytic domain structure showed that this dinucleotide adopted a binding pose that persisted for the entire 400 ns simulation time in two of the three experiments (Fig. 6d). In the third experiment, the same pose was maintained for about 300 ns and, after that period, the cytidine at position 0 came out of the pocket and sampled other conformations while the cytidine at position −1 remained bound. In contrast, no persistent nucleotide binding pose was observed in three separate MD simulations of A3G with 5′-TC.

Discussion

Originally suggested by E. coli mutagenesis experiments and subsequently demonstrated in several biochemical and biological assay systems, AID, APOBEC1, and various APOBEC3 proteins elicit distinct local DNA cytosine deamination preferences3,71 (Introduction). A loop adjacent to the active site (loop 7 in most family members) has been strongly implicated in local selection of the nucleobase immediately 5′ of the target cytosine with, for instance, A3G preferring a 5′ cytosine and A3A a 5′ thymine15,23,34,35,38,41,42. Here, a series of loop replacements was used to demonstrate that loop 7 alone is responsible for governing the intrinsic preference of A3G for 5′-CC dinucleotides. A full-length A3G variant with loop 7 from A3A loses 5′-CC deamination activity and gains a strong preference for 5′-TC substrates. Deaminase activity is enhanced and local preferences are maintained by simultaneous replacement of A3G loop 3 with the homologous region of A3A. A series of single amino acid exchanges in loop 7 led to the identification of A3G D317 as a major determinant of 5′ cytosine recognition. Replacement of D317 with tyrosine (naturally occurring in A3A and A3B loop 7), phenylalanine (naturally occurring in A3C, A3D, and A3F), or tryptophan causes A3G to adopt a strong preference for single-stranded DNA substrates with 5′-TC. Extensive multi-copy molecular dynamics simulations suggest a model in which 5′-CC dinucleotide-containing substrates are preferred by A3G because D317 acts as an α-helix cap, constraining the mobility of loop 7 and revealing a novel binding pocket near Cys321 that favorably accommodates cytosine, but not thymine or larger purine nucleobases. Stabilization of helices by helix dipole capping is well-established68–70. MD simulations further indicate that the loss of the helix-capping residue in the A3G D317Y mutant may induce local refolding events in loops 1 and 7, which may ultimately combine to reshape the −1 nucleobase binding pocket. Thus, the single amino acid substitution D317Y appears to cause A3G to lose its unique 5′-CC binding site, modifying its loop regions to adopt a DNA binding pose similar to other APOBEC3 enzymes that prefer 5′-TC dinucleotide-containing substrates.

The full replacement of loop 7 of A3G with the homologous region of A3A caused full conversion to a 5′-TC preference, whereas the single amino acid substitution D317Y caused a strong but partial conversion (compare Figs. 3b and 4c). These observations suggest that at least one other residue in loop 7 and/or the overall topology of loop 7 also contributes to 5′ base selection, substrate binding, and ultimately target cytosine deamination. Multiple substrate and product bound crystal structures may be required to appreciate the full set of molecular contacts required for single-stranded DNA binding and target cytosine deamination.

Overall, the results with the fluorescence-based DNA C-to-U deamination assays correlated very well with the HIV-1 restriction and hypermutation data. However, some minor differences can be reconciled by the fact that the fluorescence-based assay has a relatively low signal to noise making weaker activities hard to differentiate. In contrast, the HIV restriction and hypermutation assays are more sensitive, but they must also be interpreted carefully because similar losses of infectivity can be obtained with different levels of hypermutation (e.g., wildtype versus loop 3/7 construct in Fig. 3). Part of this may be due to the fact that it theoretically takes only 1 base substitution mutation to inactivate GFP (the infectivity assay read-out), whereas sequencing provides a more direct measure of enzymatic activity.

It is noteworthy that at least two distinct classes of small molecules block A3G enzymatic activity through covalent attachment to Cys321, which is near Asp317 in loop 763,72. Select compounds defined by catechol or 4-amino-1,2,4-triazole-3-thiol moieties have the capacity to covalently bind Cys321 and block substrate single-stranded DNA cytosine from entering the active site. It is therefore possible that a deeper appreciation of the molecular ligands required for 5′ base selection may help inform the design of deaminase inhibitor compounds. Future applications for DNA deaminase inhibitors could include infectious disease, autoimmune disease, and possibly even cancer therapies. For instance, small molecules that block the activity of the 5′-TC genomic DNA deaminase A3B73, which has a catalytic domain 92% similar to A3A, could have utility as adjuvants to existing chemotherapeutics by dampening the rate of tumor evolution and thereby decreasing the probability of a tumor becoming drug resistant.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid constructs

Wildtype A3A and A3G cDNA sequences used in this study match the GenBank reference sequences, NM_145699 and NM_021822, respectively. APOBEC3 expression constructs were expressed in pcDNA3.1 vectors with C-terminal V5 or MycHis tags. To prevent expression of the highly mutagenic human A3A protein in E. coli, an intron was inserted into A3A coding region between exons 2 and 3, as described36. Loop graft variants were created by overlap extension PCR, and single amino acid substitution variants were made by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene). Restriction digests and DNA sequencing were used to verify the integrity of all constructs. Primer sequences are available upon request.

DNA C-to-U activity assays

Semi-confluent 293T cells in 6 well plates were transiently transfected with 2 μg of the indicated constructs using TransIT transfection reagent (Mirus Bio). Two days post-transfection, cytoplasmic extracts were made by lysing the cells in GST lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1mM MgCl2,1 mM ZnCl2,10% Glycerol, 50μg/ml RNase A, protease inhibitor). Clarified cell lysates were used for fluorescence-based single-stranded DNA cytosine deaminase activity assays using Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) from a fluorescein (FAM) label to a carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) fluorophore62,63. Briefly, 20 μl of each cell lysate was incubated for 2 hrs at 37°C with 10 pmol of ssDNA oligonucleotide substrate 5′-FAM-AAACCCTAATAGATAATGTGA-TAMRA or 5′-FAM-ATAATCAAATAGATAAT-TAMRA (Biosearch Technologies, Inc.), 0.02 units of uracil DNA glycosylase (UDG; NEB), and 15 μl of 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH7.4),10 mM EDTA in Nunc 384-well black plates. Deamination of cytosine results in uracil, which is excised by UDG. The resulting abasic site is subjected to hydrolytic cleavage by adding 0.1 M NaOH, followed by mixing and incubating at 37°C for another 30 min. 3 μl of 4N HCl and 37 μl of 2M Tris-Cl (pH7.9) was then added for neutralization. Upon cleavage, the FAM and TAMRA labels are physically separated resulting in loss of FRET and increase in FAM signal. Activity was therefore quantified using a fluorescence plate reader with excitation at 490 nm and emission at 520 nm (Synergy Mx monochromator-based Multi-Mode Reader (BioTek Instruments Inc.) or LJL Analyst AD (LJL BioSystems Inc.).

Single cycle HIV-1 infectivity assays

293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin. At 50% confluency, cells were transfected (TransIT; Mirus Bio) with 100 ng of pMDG(vesicular stomatitis virus G protein [VSV-G]-ENV), 300 ng of pCS-CG, and 300 ng of pΔNRF (gag-pol-rev-tat)19 along with gradient of either V5 tagged APOBEC3 (0, 50 and 200 ng) expression construct or with an appropriate empty vector using TransIT (Mirus Bio). After 48 hours, virus-containing supernatants were harvested and purified by 0.45 μm PVDF filters to remove any remaining producer cells. A portion of the clarified viral supernatants was used to infect fresh 293T target cells and immunoblotted for the incorporated A3. Transfection efficiency of the producer cells was measured by flow cytometry for GFP (FACSCanto II Ruo; BD Biosciences). Producer cell lysates were immunoblotted to measure protein expression levels. 72 hours post-infection, target cells were harvested and infectivity (GFP) was measured by flow cytometry. Data were analyzed using FlowJo flow cytometry analysis software, version 8.7.1. Quantification was done by first gating the live cell population, followed by gating on the GFP-positive cells. All experiments were performed in triplicate with means and standard deviations shown.

Immunoblotting

Transfected 293T cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed directly in 2.5 X Laemmli Sample Buffer (25mM Tris, pH 6.8, 8% glycerol, 0.8% SDS, 2% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.02% bromophenol blue). The mixture was boiled at 95°C for 30 minutes. Virus-like particles were isolated from culture supernatants by purification through 0.45 μm PVDF filters (Millipore) followed by centrifugation (13,000 rpm for 2 hours) through a 20% sucrose cushion and lysis directly in 2.5X Laemmli sample buffer. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE on 12.5% resolving gels (Bio-Rad Criterion) at 150 V for 90 min. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad) at 90V for 2 hours. Membranes were blocked in 4% milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 0.1% Tween-20 prior to overnight incubation with mouse anti-V5 (Invitrogen) to detect A3G-V5 (Invitrogen) or mouse anti-α-Tubulin (Covance), p24/capsid (NIH ARRRP 3537 courtesy of B. Chesebro and K. Wehrly). Anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad) were detected using Hyglo HRP detection reagents (Denville Scientific). Blots were incubated in stripping buffer (0.2M glycine pH 2.2, 1.0% SDS, 1.0% Tween-20) before re-probing.

Proviral DNA sequence analysis

Genomic DNA was prepared from the HIV-1 infected 293T cell cultures using the DNeasy kit (Qiagen). A 712-bp amplicon from the GFP gene of integrated proviruses was amplified by Taq polymerase (Roche) for 20 cycles using degenerate primers 5′-ACTACAACARCCACAACRTCTATATC and 5′-AGGGTGTAAYAAGYGGGTGTTYT. Nested PCRs was done using a degenerate set of primers 5′-CTTCAARATCCRCCACAAC and 5′-GGAAGTAGYYTTGTGTGTGGTAGAT to amplify 514-bp amplicons. PCR products were separated on agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The amplicons were purified and cloned into pJET1.2 using the CloneJET PCR cloning kit (Fermentas). The amplicons were sequenced at the BioMedical Genomics Center at the University of Minnesota. Sequences were analyzed using Sequencher, version 4.6 (Gene Codes Corp.). Duplicate sequences potentially due to PCR treated were only analyzed once.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

A3G catalytic domain molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were based on crystal structure 3IR260. Amino acid substitutions introduced for protein solubility and crystallization were reverted in silico and the intermolecular zinc atom was removed to obtain a virtual wildtype structure. For cytidine-bound A3G simulations, the binding pose of cytidine was modelled using mouse cytidine deaminase as a template (2FR6)74 after which the distorted transition-state-like structure of cytidine was replaced with a geometry-optimized cytidine structure. The crystallographic water molecules were retained in each system solvated in a TIP3P water box with 10 Å buffer75. The residues coordinating zinc were modelled using the cationic dummy atom method76. Residues Glu254 and Glu259 that are in close proximity to the zinc site were protonated to comply with the suggestions of the cationic dummy atom model. The protonation states of other titratable residues were determined using the Whatif Web Interface77. MolProbity web server was used to check and correct histidine, asparagine and glutamine side chain orientations78. Systems were simulated at 200 mM salt concentration. Each solvated A3G structure consisted of about 31,000 atoms. Amber FF99SB force field was used to build the systems79.

Each system was first relaxed using 36,000 steps of minimization and four consecutive restrained 250 ps MD simulations. Subsequently, two copies of 150 ns MD simulations were performed at 1 atm and 310 K using NAMD2.7 suite80. This was done for each apo form of wildtype A3G, the apo form of A3G-D317Y, and the cytidine-bound form of wildtype A3G.

The two distinct binding modes of cytidine in our cytdine-bound MD simulations were combined in order to model 5′-CC and 5′-TC dinucleotides in the virtual wildtype A3G active site. For each of the dinucleotide-bound systems, three copies of 400 ns MD simulations were performed at 1 atm and 310 K using Amber12 suite (http://ambermd.org)81 on the GPU-based Keck II Center. RMSD plots indicate stability of the presented MD simulations (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

APOBEC3G is a DNA cytosine deaminase with an intrinsic 5′CC preference

APOBEC3A is a DNA cytosine deaminase with an intrinsic 5′TC preference

The intrinsic DNA deamination preference of both enzymes maps to loop 7

APOBEC3G loop 7 D317 is required for 5′CC dinucleotide selection

MD simulations suggest D317 stabilizes loop 7 and creates a pocket for binding 5′CC

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Harki, M. Olson, V. Feher, and several members of the Harris laboratory for valuable feedback. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI064046 and P01 GM091743 to RSH; F32 GM095219 to MAC; DP2-OD007237 to REA) and the National Science Foundation (XSEDE Supercomputer resources grant LRAC CHE060073N to REA). Support from the National Biomedical Computation Resource, the Center for Theoretical Biological Physics, and the UCSD Drug Discovery Institute is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Longerich S, Basu U, Alt F, Storb U. AID in somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:164–74. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Noia JM, Neuberger MS. Molecular mechanisms of antibody somatic hypermutation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:1–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.061705.090740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris RS, Petersen-Mahrt SK, Neuberger MS. RNA editing enzyme APOBEC1 and some of its homologs can act as DNA mutators. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1247–53. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00742-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanc V, Davidson NO. C-to-U RNA editing: mechanisms leading to genetic diversity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1395–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petit V, Guetard D, Renard M, Keriel A, Sitbon M, Wain-Hobson S, Vartanian JP. Murine APOBEC1 is a powerful mutator of retroviral and cellular RNA in vitro and in vivo. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:65–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cervantes Gonzalez M, Suspene R, Henry M, Guetard D, Wain-Hobson S, Vartanian JP. Human APOBEC1 cytidine deaminase edits HBV DNA. Retrovirology. 2009;6:96. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikeda T, Abd El Galil KH, Tokunaga K, Maeda K, Sata T, Sakaguchi N, Heidmann T, Koito A. Intrinsic restriction activity by apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme APOBEC1 against the mobility of autonomous retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:5538–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikeda T, Ohsugi T, Kimura T, Matsushita S, Maeda Y, Harada S, Koito A. The antiretroviral potency of APOBEC1 deaminase from small animal species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:6859–71. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niewiadomska AM, Tian C, Tan L, Wang T, Sarkis PT, Yu XF. Differential inhibition of long interspersed element 1 by APOBEC3 does not correlate with high-molecular-mass-complex formation or P-body association. J Virol. 2007;81:9577–83. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02800-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malim MH, Emerman M. HIV-1 accessory proteins--ensuring viral survival in a hostile environment. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:388–98. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albin JS, Harris RS. Interactions of host APOBEC3 restriction factors with HIV-1 in vivo: implications for therapeutics. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2010;12:e4. doi: 10.1017/S1462399409001343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wissing S, Galloway NL, Greene WC. HIV-1 Vif versus the APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases: an intracellular duel between pathogen and host restriction factors. Mol Aspects Med. 2010;31:383–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris RS, Hultquist JF, Evans DT. The restriction factors of human immunodeficiency virus. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:40875–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.416925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niewiadomska AM, Yu XF. Host restriction of HIV-1 by APOBEC3 and viral evasion through Vif. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;339:1–25. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-02175-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris RS, Bishop KN, Sheehy AM, Craig HM, Petersen-Mahrt SK, Watt IN, Neuberger MS, Malim MH. DNA deamination mediates innate immunity to retroviral infection. Cell. 2003;113:803–9. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangeat B, Turelli P, Caron G, Friedli M, Perrin L, Trono D. Broad antiretroviral defence by human APOBEC3G through lethal editing of nascent reverse transcripts. Nature. 2003;424:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature01709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang H, Yang B, Pomerantz RJ, Zhang C, Arunachalam SC, Gao L. The cytidine deaminase CEM15 induces hypermutation in newly synthesized HIV-1 DNA. Nature. 2003;424:94–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bishop KN, Holmes RK, Sheehy AM, Davidson NO, Cho SJ, Malim MH. Cytidine deamination of retroviral DNA by diverse APOBEC proteins. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1392–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liddament MT, Brown WL, Schumacher AJ, Harris RS. APOBEC3F properties and hypermutation preferences indicate activity against HIV-1 in vivo. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1385–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiegand HL, Doehle BP, Bogerd HP, Cullen BR. A second human antiretroviral factor, APOBEC3F, is suppressed by the HIV-1 and HIV-2 Vif proteins. EMBO J. 2004;23:2451–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng YH, Irwin D, Kurosu T, Tokunaga K, Sata T, Peterlin BM. Human APOBEC3F is another host factor that blocks human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. Journal of Virology. 2004;78:6073–6076. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.6073-6076.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosler C, Kock J, Kann M, Malim MH, Blum HE, Baumert TF, von Weizsacker F. APOBEC-mediated interference with hepadnavirus production. Hepatology. 2005;42:301–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.20801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen H, Lilley CE, Yu Q, Lee DV, Chou J, Narvaiza I, Landau NR, Weitzman MD. APOBEC3A is a potent inhibitor of adeno-associated virus and retrotransposons. Curr Biol. 2006;16:480–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonvin M, Achermann F, Greeve I, Stroka D, Keogh A, Inderbitzin D, Candinas D, Sommer P, Wain-Hobson S, Vartanian JP, Greeve J. Interferon-inducible expression of APOBEC3 editing enzymes in human hepatocytes and inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication. Hepatology. 2006;43:1364–74. doi: 10.1002/hep.21187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumert TF, Rosler C, Malim MH, von Weizsacker F. Hepatitis B virus DNA is subject to extensive editing by the human deaminase APOBEC3C. Hepatology. 2007 doi: 10.1002/hep.21733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vartanian JP, Guetard D, Henry M, Wain-Hobson S. Evidence for editing of human papillomavirus DNA by APOBEC3 in benign and precancerous lesions. Science. 2008;320:230–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1153201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henry M, Guetard D, Suspene R, Rusniok C, Wain-Hobson S, Vartanian JP. Genetic editing of HBV DNA by monodomain human APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases and the recombinant nature of APOBEC3G. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kock J, Blum HE. Hypermutation of hepatitis B virus genomes by APOBEC3G, APOBEC3C and APOBEC3H. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:1184–91. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83507-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delebecque F, Suspene R, Calattini S, Casartelli N, Saib A, Froment A, Wain-Hobson S, Gessain A, Vartanian JP, Schwartz O. Restriction of foamy viruses by APOBEC cytidine deaminases. J Virol. 2006;80:605–14. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.605-614.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gunther S, Sommer G, Plikat U, Iwanska A, Wain-Hobson S, Will H, Meyerhans A. Naturally occurring hepatitis B virus genomes bearing the hallmarks of retroviral G-->A hypermutation. Virology. 1997;235:104–8. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahieux R, Suspene R, Delebecque F, Henry M, Schwartz O, Wain-Hobson S, Vartanian JP. Extensive editing of a small fraction of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 genomes by four APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:2489–94. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80973-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suspène R, Guétard D, Henry M, Sommer P, Wain-Hobson S, Vartanian JP. Extensive editing of both hepatitis B virus DNA strands by APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8321–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408223102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ooms M, Krikoni A, Kress AK, Simon V, Munk C. APOBEC3A, APOBEC3B, and APOBEC3H haplotype 2 restrict human T-lymphotropic virus type 1. J Virol. 2012;86:6097–108. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06570-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu Q, Konig R, Pillai S, Chiles K, Kearney M, Palmer S, Richman D, Coffin JM, Landau NR. Single-strand specificity of APOBEC3G accounts for minus-strand deamination of the HIV genome. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:435–42. doi: 10.1038/nsmb758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chelico L, Pham P, Calabrese P, Goodman MF. APOBEC3G DNA deaminase acts processively 3′ --> 5′ on single-stranded DNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:392–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hultquist JF, Lengyel JA, Refsland EW, LaRue RS, Lackey L, Brown WL, Harris RS. Human and rhesus APOBEC3D, APOBEC3F, APOBEC3G, and APOBEC3H demonstrate a conserved capacity to restrict Vif-deficient HIV-1. J Virol. 2011;85:11220–34. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05238-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Refsland EW, Hultquist JF, Harris RS. Endogenous origins of HIV-1 G-to-A hypermutation and restriction in the nonpermissive T cell line CEM2n. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002800. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stenglein MD, Burns MB, Li M, Lengyel J, Harris RS. APOBEC3 proteins mediate the clearance of foreign DNA from human cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:222–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suspène R, Aynaud MM, Guetard D, Henry M, Eckhoff G, Marchio A, Pineau P, Dejean A, Vartanian JP, Wain-Hobson S. Somatic hypermutation of human mitochondrial and nuclear DNA by APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases, a pathway for DNA catabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4858–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009687108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bulliard Y, Narvaiza I, Bertero A, Peddi S, Rohrig UF, Ortiz M, Zoete V, Castro-Diaz N, Turelli P, Telenti A, Michielin O, Weitzman MD, Trono D. Structure-function analyses point to a polynucleotide-accommodating groove essential for APOBEC3A restriction activities. J Virol. 2011;85:1765–76. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01651-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carpenter MA, Li M, Rathore A, Lackey L, Law EK, Land AM, Leonard B, Shandilya SM, Bohn MF, Schiffer CA, Brown WL, Harris RS. Methylcytosine and normal cytosine deamination by the foreign DNA restriction enzyme APOBEC3A. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:34801–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.385161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thielen BK, McNevin JP, McElrath MJ, Hunt BV, Klein KC, Lingappa JR. Innate immune signaling induces high levels of TC-specific deaminase activity in primary monocyte-derived cells through expression of APOBEC3A isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27753–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koning FA, Newman EN, Kim EY, Kunstman KJ, Wolinsky SM, Malim MH. Defining APOBEC3 expression patterns in human tissues and hematopoietic cell subsets. J Virol. 2009;83:9474–85. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01089-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Refsland EW, Stenglein MD, Shindo K, Albin JS, Brown WL, Harris RS. Quantitative profiling of the full APOBEC3 mRNA repertoire in lymphocytes and tissues: implications for HIV-1 restriction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4274–4284. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wijesinghe P, Bhagwat AS. Efficient deamination of 5-methylcytosines in DNA by human APOBEC3A, but not by AID or APOBEC3G. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:9206–17. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berger G, Durand S, Fargier G, Nguyen XN, Cordeil S, Bouaziz S, Muriaux D, Darlix JL, Cimarelli A. APOBEC3A is a specific inhibitor of the early phases of HIV-1 infection in myeloid cells. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002221. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koning FA, Goujon C, Bauby H, Malim MH. Target cell-mediated editing of HIV-1 cDNA by APOBEC3 proteins in human macrophages. J Virol. 2011;85:13448–52. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00775-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conticello SG. The AID/APOBEC family of nucleic acid mutators. Genome Biol. 2008;9:229. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-6-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.LaRue RS, Andresdottir V, Blanchard Y, Conticello SG, Derse D, Emerman M, Greene WC, Jonsson SR, Landau NR, Lochelt M, Malik HS, Malim MH, Munk C, O’Brien SJ, Pathak VK, Strebel K, Wain-Hobson S, Yu XF, Yuhki N, Harris RS. Guidelines for naming nonprimate APOBEC3 genes and proteins. J Virol. 2009;83:494–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01976-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langlois MA, Beale RC, Conticello SG, Neuberger MS. Mutational comparison of the single-domained APOBEC3C and double-domained APOBEC3F/G anti-retroviral cytidine deaminases provides insight into their DNA target site specificities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:1913–23. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kohli RM, Abrams SR, Gajula KS, Maul RW, Gearhart PJ, Stivers JT. A portable hot spot recognition loop transfers sequence preferences from APOBEC family members to activation-induced cytidine deaminase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:22898–904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.025536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carpenter MA, Rajagurubandara E, Wijesinghe P, Bhagwat AS. Determinants of sequence-specificity within human AID and APOBEC3G. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:579–87. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang M, Rada C, Neuberger MS. Altering the spectrum of immunoglobulin V gene somatic hypermutation by modifying the active site of AID. J Exp Med. 2010;207:141–53. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kohli RM, Maul RW, Guminski AF, McClure RL, Gajula KS, Saribasak H, McMahon MA, Siliciano RF, Gearhart PJ, Stivers JT. Local sequence targeting in the AID/APOBEC family differentially impacts retroviral restriction and antibody diversification. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:40956–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.177402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Losey HC, Ruthenburg AJ, Verdine GL. Crystal structure of Staphylococcus aureus tRNA adenosine deaminase TadA in complex with RNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:153–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Conticello SG, Langlois MA, Neuberger MS. Insights into DNA deaminases. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:7–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Henry M, Terzian C, Peeters M, Wain-Hobson S, Vartanian JP. Evolution of the primate APOBEC3A cytidine deaminase gene and identification of related coding regions. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmitt K, Guo K, Algaier M, Ruiz A, Cheng F, Qiu J, Wissing S, Santiago ML, Stephens EB. Differential virus restriction patterns of rhesus macaque and human APOBEC3A: implications for lentivirus evolution. Virology. 2011;419:24–42. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shandilya SMD, Nalam MNL, Nalivaika EA, Gross PJ, Valesano JC, Shindo K, Li M, Munson M, Royer WE, Harjes E, Kouno T, Matsuo H, Harris RS, Somasundaran M, Schiffer CA. Crystal structure of the APOBEC3G catalytic domain reveals potential oligomerization interfaces. Structure. 2010;18:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Byeon IJ, Ahn J, Mitra M, Byeon CH, Hercik K, Hritz J, Charlton LM, Levin JG, Gronenborn AM. NMR structure of human restriction factor APOBEC3A reveals substrate binding and enzyme specificity. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1890. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thielen BK, Klein KC, Walker LW, Rieck M, Buckner JH, Tomblingson GW, Lingappa JR. T cells contain an RNase-insensitive inhibitor of APOBEC3G deaminase activity. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:1320–34. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li M, Shandilya SM, Carpenter MA, Rathore A, Brown WL, Perkins AL, Harki DA, Solberg J, Hook DJ, Pandey KK, Parniak MA, Johnson JR, Krogan NJ, Somasundaran M, Ali A, Schiffer CA, Harris RS. First-in-class small molecule inhibitors of the single-strand DNA cytosine deaminase APOBEC3G. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:506–17. doi: 10.1021/cb200440y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schumacher AJ, Haché G, MacDuff DA, Brown WL, Harris RS. The DNA deaminase activity of human APOBEC3G is required for Ty1, MusD, and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 restriction. J Virol. 2008;82:2652–60. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02391-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miyagi E, Opi S, Takeuchi H, Khan M, Goila-Gaur R, Kao S, Strebel K. Enzymatically active APOBEC3G is required for efficient inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2007;81:13346–53. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01361-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Browne EP, Allers C, Landau NR. Restriction of HIV-1 by APOBEC3G is cytidine deaminase-dependent. Virology. 2009;387:313–21. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Holmes RK, Malim MH, Bishop KN. APOBEC-mediated viral restriction: not simply editing? Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:118–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aurora R, Rose GD. Helix capping. Protein Sci. 1998;7:21–38. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bodkin MJ, Goodfellow JM. Competing interactions contributing to alpha-helical stability in aqueous solution. Protein Sci. 1995;4:603–12. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Doig AJ, Baldwin RL. N- and C-capping preferences for all 20 amino acids in alpha-helical peptides. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1325–36. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Petersen-Mahrt SK, Harris RS, Neuberger MS. AID mutates E. coli suggesting a DNA deamination mechanism for antibody diversification. Nature. 2002;418:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature00862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Olson ME, Li M, Harris RS, Harki DA. Small-molecule APOBEC3G DNA cytosine deaminase inhibitors based on a 4-amino-1,2,4-triazole-3-thiol scaffold. ChemMedChem. 2013;8:112–7. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Burns MB, Lackey L, Carpenter MA, Rathore A, Land AM, Leonard B, Refsland EW, Kotandeniya D, Tretyakova N, Nikas JB, Yee D, Temiz NA, Donohue DE, McDougle RM, Brown WL, Law EK, Harris RS. APOBEC3B is an enzymatic source of mutation in breast cancer. Nature. 2013;494:366–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Teh AH, Kimura M, Yamamoto M, Tanaka N, Yamaguchi I, Kumasaka T. The 1.48 A resolution crystal structure of the homotetrameric cytidine deaminase from mouse. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7825–33. doi: 10.1021/bi060345f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of Simple Potential Functions for Simulating Liquid Water. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pang YP. Novel zinc protein molecular dynamics simulations: Steps toward antiangiogenesis for cancer treatment. Journal of Molecular Modeling. 1999;5:196–202. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rodriguez R, Chinea G, Lopez N, Pons T, Vriend G. Homology modeling, model and software evaluation: three related resources. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:523–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.6.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen VB, Arendall WB, 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hornak V, Abel R, Okur A, Strockbine B, Roitberg A, Simmerling C. Comparison of multiple Amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins. 2006;65:712–25. doi: 10.1002/prot.21123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1781–802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gotz AW, Williamson MJ, Xu D, Poole D, Le Grand S, Walker RC. Routine Microsecond Molecular Dynamics Simulations with AMBER on GPUs. 1. Generalized Born. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8:1542–1555. doi: 10.1021/ct200909j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.