Abstract

MutS functions in mismatch repair (MMR) to scan DNA for errors, identify a target site and trigger subsequent events in the pathway leading to error removal and DNA re-synthesis. These actions, enabled by the ATPase activity of MutS, are now beginning to be analyzed from the perspective of the protein itself. This study provides the first ensemble transient kinetic data on MutS conformational dynamics as it works with DNA and ATP in MMR. Using a combination of fluorescence probes (on T. aquaticus MutS and DNA) and signals (intensity, anisotropy and resonance energy transfer), we have monitored the timing of key conformational changes in MutS that are coupled to mismatch binding and recognition, ATP binding and hydrolysis, as well as sliding clamp formation and signaling of repair. Significant findings include: (a) a slow step that follows weak initial interaction between MutS and DNA, in which concerted conformational changes in both macromolecules control mismatch recognition, (b) rapid, binary switching of MutS conformations that is concerted with ATP binding and hydrolysis, and (c) is stalled after mismatch recognition to control formation of the ATP-bound MutS sliding clamp. These rate-limiting pre- and post-mismatch recognition events outline the mechanism of action of MutS on DNA during initiation of MMR.

Keywords: DNA mismatch repair, MutS, kinetic mechanism, ATPase, FRET

INTRODUCTION

DNA mismatch repair (MMR) identifies and corrects errors made during DNA synthesis, such as mispaired bases and short insertion/deletion loops (IDL), thereby greatly reducing mutation frequency (by ~ 103-fold) and genomic instability.1,2 MMR also responds to chemical damage in DNA, in this case mediating cell cycle checkpoints and cell death, effectively mitigating the outcomes of genomic instability.3–5 Hence, loss of MMR protein function is linked strongly with inherited and spontaneous carcinogenesis.6 As is the case for other template-dependent DNA repair processes, MMR comprises: (a) recognition of the error, (b) resection of the error-containing DNA strand, and (c) re-synthesis of DNA. The MutS protein recognizes mismatches, IDLs and damage lesions and then recruits MutL protein to initiate the cellular response, which results in DNA repair and/or cell death depending on whether or not the error/lesion is repairable by MMR.

In E. coli, MutS protein forms homodimers that bind mismatch sites with high affinity and specificity.7 In eukaryotes, MutS homologues form heterodimers—Msh2–Msh6 (MutSα) that predominantly binds mismatches and small IDLs,8 and Msh2–Msh3 (MutSβ) that predominantly binds large IDL structures.9E. coli MutL is also a homodimer that communicates with MutH endonuclease to trigger nicking of the error-containing strand for resection.10–13 In other bacteria and eukaryotes, MutL homologues (e.g., S. cerevisiae Mlh1-Pms1, human MLH1-PMS2; MutLα) themselves have endonuclease activity that is essential for MMR.14–17 Ongoing analysis of MutS proteins by diverse approaches ranging from crystallography to ensemble and single-molecule kinetics has revealed remarkable details about their structure and function. In crystal structures of MutS, MutSα and MutSβ dimers bound to DNA, the two subunits are assembled in the form of the greek letter “θ” (Fig. 1a).7–9,18 The N-terminal DNA binding domains (I) and clamp domains (IV) form the lower channel that binds mismatched DNA asymmetrically and holds it in a sharply bent conformation, while the ATPase domains (V) form composite catalytic sites that cap the top of the upper channel.19 A conserved Phe-X-Glu motif from domain I of one MutS subunit (Msh6 in MutSα) makes specific contacts with the mismatched/inserted base (Phe stacks against the base and Glu makes a hydrogen bond).20–23 In addition there are several non-specific electrostatic contacts between MutS domains I and IV and the backbone of DNA flanking the mismatch site. Recent single-molecule imaging studies of S. cerevisiae MutSα and T. aquaticus MutS have revealed that the protein can arrive at a mismatch site via 1D sliding along the helical contour of DNA or via 3D diffusion.24–28 While its interaction with duplex DNA is rather weak (KD ~ 1 – 20 μM),23,26,29 MutS binds a mismatch with high affinity (KD ~ 5 – 30 nM)23,26,29,30 and can remain there for a prolonged period.24,26,30,31 In the crystal structure of T. aquaticus MutS dimer without DNA, domains I and IV are not resolved, indicating higher mobility (Fig. 1a).18 Equilibrium measurements of fluorophore-labeled T. aquaticus MutS domains IV indicate they are far apart in the absence of DNA,32 and single-molecule measurements of FRET (smFRET) between donor and acceptor fluorophore-labeled domains I indicate that mismatch binding brings them in close proximity (30 Å apart versus ~ 70 Å apart in the absence of DNA),28 likely as observed in MutS•mismatched DNA complex structures. Deuterium exchange analysis of E. coli MutS and S. cerevisiae MutSα is also consistent with such mismatched DNA-induced changes in these domains.33 Together, these findings describe an open MutS DNA binding site that is stabilized in a closed conformation upon mismatch recognition.

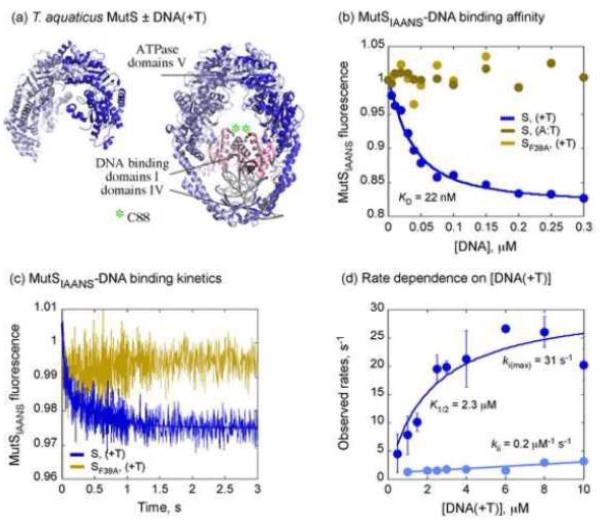

Fig. 1.

DNA mismatch recognition involves weak initial complex formation and slow change in MutS conformation. (a) Crystal structure of T. aquaticus MutS dimer free and bound to T-bulge DNA (PDB: 1EWQ), with mismatch binding domains I shown in pink and C88 marked with an asterisk. (b) Quenching of MutSIAANS fluorescence reports binding to DNA(+T) with an apparent KD of 22 nM; no change is detected with matched DNA or with MutS-F39AIAANS mutant. (c) A stopped-flow trace shows biphasic fluorescence quenching of MutSIAANS (0.1 μM) when mixed with DNA(+T) (6 μM); a 2-exponential fit yields apparent rates of 26.6 s−1 and 2 s−1; no signal change is detected with MutS-F39AIAANS. (d) The rate of the first phase (ki) increases hyperbolically with DNA(+T) to a maximum of 31 s−1 with an apparent K1/2 of 2.3 μM; the rate of the second phase (kii) shows slight linear increase at 0.2 μM−1 s−1.

The MutS dimer also exhibits asymmetric ATP binding and hydrolysis activity, whereby one subunit binds ATP with high affinity (KD ~ 2 μM) and the other with low affinity (KD ~ 30 μM).34–36 When MutS is not bound to a mismatch, ATP binding is followed by rapid hydrolysis and phosphate release at the high-affinity site (khydrolysis = 10 – 12 s−1 for T. aquaticus MutS at 40 °C) and slower steady state turnover (kcat = 0.3 s−1 for T. aquaticus MutS at 40 °C), which may be limited by ADP dissociation.35 Previous studies of MutSα have shown that the Msh6 subunit hydrolyzes ATP rapidly37 and Msh2 holds ADP with high affinity.38 Thus, in mismatch search mode the MutS dimer is likely to have at least one ADP bound with high affinity.39 After mismatch recognition, ATP hydrolysis is suppressed,34,35 and ATP-bound MutS can once again slide on DNA, but this time as a freely diffusing topologically linked clamp that does not retain the ability to bind mismatches;40,41 this behavior was most recently confirmed by single-molecule imaging of S. cerevisiae MutSα and T. aquaticus MutS on DNA.24,26–28,42 Chemical cross-linking,43 structural44 and deuterium exchange45 analysis of E. coli MutS, computational normal mode analysis of E. coli MutS and human MutSα,46 and smFRET analysis of fluorophore-labeled T. aquaticus MutS domains I,28 all indicate that ATP binding to domains V leads to large-scale conformational changes in mismatch binding domains I—likely forming the sliding clamp. This ATP-bound state of MutS is considered important for communication with MutL and initiation of MMR.13,43,47,48 Recently, a complex of S. cerevisiae MutSα and MutLα formed at a mismatch was observed diffusing on DNA after addition of ATP to the reaction.24 These findings support a prominent model of MMR, which posits that an ATP binding-induced switch in mismatch-bound MutS conformation initiates subsequent steps leading to DNA repair.40 Key kinetic questions about the MutS mechanism of action during MMR have to be resolved—how MutS transitions from a DNA-unbound or non-specific matched DNA-bound state (mismatch search mode) to a specific mismatch-bound state with kinked DNA; how it transitions from this mismatch-bound state to one whereby it can communicate with MutL; how it uses asymmetric ATP binding/hydrolysis/product release to drive these actions on DNA; and, most importantly, which steps are rate-determining and thus govern flux through the pathway. In the current study we have addressed these questions by a transient kinetics approach—monitoring the conformational dynamics of fluorophore-labeled T. aquaticus MutS protein and DNA during and after binding to a T-bulge site. The data reveal both slow and fast conformational changes in MutS and DNA that are coupled tightly with each other and with MutS ATPase activity, and identify specific slow conformational changes that direct the reaction from mismatch search through recognition and subsequent initiation of DNA repair.

RESULTS

MutSIAANS fluorescence reports selective, high affinity binding to T-bulge DNA

In order to monitor the kinetics of MutS conformational changes during initiation of MMR, we generated a single Cys mutant in the mismatch binding domain I (T. aquaticus MutS-C42A/M88C) and labeled it with the IAANS fluorophore (Fig. 1a). Molecular dynamics simulations based on the MutS•DNA(+T) crystal structure18 suggest that fluorophores at the C88 position in each monomer are separated on average by ~ 20 Å.28 Titration of MutSIAANS with DNA(+T), a 37 nucleotide (nt) DNA substrate containing a central T-bulge, results in quenching of IAANS fluorescence (Fig. 1b). The binding isotherm yields a low apparent dissociation constant, KD = 22 ± 4 nM, indicating high-affinity interaction between the protein and DNA, consistent with previous measurements using 32P-, 2-aminopurine-, or TAMRA-labeled DNA (KD = 15 – 25 nM).30,35 Moreover, the signal reports selective binding of MutSIAANS to the T-bulge, since no quenching is detected with a matched DNA substrate or with MutS-F39AIAANS, in which the essential mismatch binding Phe residue is mutated to Ala (Fig. 1b).

We then measured the rate of MutSIAANS binding to mismatched DNA by mixing the two reactants in a stopped-flow instrument. Consistent with the equilibrium binding experiment described above, MutSIAANS fluorescence is quenched rapidly on interaction with DNA(+T). The kinetics are biphasic, and a representative trace shown for 6 μM DNA(+T) yields rates ki = 26.6 ± 4 s−1 and kii = 2 ± 0.2 s−1 when fit with a double exponential function (Fig. 1c). No change in signal was detected on mixing the mutant MutS-F39AIAANS with mismatched DNA (Fig. 1c) or on mixing MutSIAANS with matched DNA (data not shown). Titration of MutSIAANS with increasing DNA(+T) revealed that the fast rate, ki, increases with substrate concentration in a hyperbolic manner, reaching a maximum of 31 ± 4 s−1 with an apparent K1/2 of 2.3 ± 0.7 μM (Fig. 1d). Hyperbolic dependence of this rate on DNA(+T) concentration suggests a two-step binding mechanism with initial bimolecular association followed by a concentration-independent second step—possibly a change in complex conformation that is limited to 31 s−1. Another notable finding is that the K1/2 value of 2.3 μM obtained from this binding isotherm is > 100-fold weaker than the KD of 22 nM obtained from equilibrium binding measurements (Fig. 1b). This large difference in values suggests that the initial collision complex is much weaker than the final MutS•DNA(+T) mismatch recognition complex. We explored this hypothesis by measuring the interaction directly by fluorescence anisotropy of TAMRA-labeled DNA(+T), as described below. The other rate, kii, increases linearly with a slight slope of 0.2 μM−1 s−1, and we could not ascertain simply from the IAANS signal whether it represents a distinct step in the binding mechanism or some heterogeneity in the MutSIAANS species that interact with DNA(+T); we favor the latter option based on experiments with labeled DNA (below).

Two-step mismatch binding with coupled conformational changes in both MutS and DNA

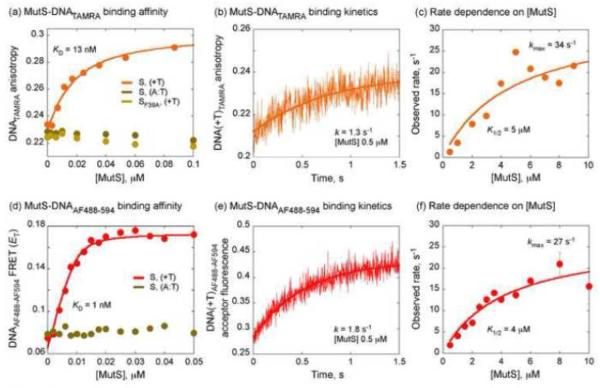

MutS binding to DNA was monitored by the increase in fluorescence anisotropy of DNA(+T)TAMRA (mismatched duplex of the same sequence as unlabeled DNA(+T) except with a TAMRA label at the 3'-end of one strand). Fig. 2a shows results from titration of DNA(+T)TAMRA with increasing wild type MutS under equilibrium conditions and, consistent with previous reports, the binding isotherm yields a KD of 13 ± 2 nM (Fig. 1b).29,30 There is no change in anisotropy on titrating DNA(+T)TAMRA with MutS-F39A or DNATAMRA (matched duplex) with wild type MutS, confirming that the signal reports selective binding of MutS to the T-bulge. Stopped-flow measurements of the interaction show rapid increase in DNA(+T)TAMRA anisotropy on mixing with MutS (Fig. 2b). The kinetic data fit well with a single exponential function to yield k = 1.3 ± 0.1 s−1 at 0.5 μM MutS concentration (note: no second slower phase is detectable even at longer observation times). Titration of DNA(+T)TAMRA with increasing MutS reveals a hyperbolic dependence of the DNA binding rate, which reaches a maximum of 34 ± 8 s−1, with an apparent dissociation constant, K1/2 = 5 ± 2 μM (Fig. 2c). The similar DNA binding kinetics observed with both MutSIAANS (Fig. 1d) and DNA(+T)TAMRA (Fig. 2c) provide strong support for a two-step mechanism of MutS binding to a mismatch.49

| (1) |

Fig. 2.

Coupled slow conformational changes in DNA and MutS result in a high-affinity, mismatch-specific recognition complex. (a) DNA(+T)TAMRA fluorescence anisotropy reports MutS binding with an apparent KD of 13 nM; no binding is detected with matched DNA or with MutS-F39A mutant. (b) A stopped-flow trace shows MutS (0.5 μM) binding to DNA(+T)TAMRA (0.06 μM) at a rate of 1.3 s−1. (c) The DNA binding rate increases hyperbolically with MutS concentration to a maximum of 34 s−1 with an apparent K1/2 of 5 μM. (d) DNA(+T)AF488-AF594 FRET efficiency reports MutS binding (and DNA bending) with an apparent KD of 1 nM; no binding is detected with matched DNA. (e) A stopped-flow trace shows MutS (0.5 μM) binding to DNA(+T)AF488-AF594 (0.03 μM) at a rate of 1.8 s−1. (f) The DNA binding/bending rate increases hyperbolically with MutS concentration to a maximum of 27 s−1 with an apparent K1/2 of 4 μM.

The first step yields a weak complex (KD1 ~ 5 μM) and then a second step involving MutS and DNA isomerization yields a high affinity, mismatch-specific complex. The rate of dissociation of this mismatch recognition complex was measured directly by mixing pre-equilibrated MutS•DNA(+T)TAMRA with excess unlabeled DNA(+T) trap (Fig. S1a). The decrease in fluorescence anisotropy reflecting DNA(+T)TAMRA release over time was fit by a single exponential function to yield koff = 0.05 s−1 (limited by k−2), the same as that obtained with DNA(+T)2-Ap substrate, which contains a 2-aminopurine probe adjacent to the T-bulge (Fig. S1a).30 From the two-step binding model with the first step in rapid equilibrium, k2 is ~ 30 s−1 (kmax = k2 + k−2), and the apparent bimolecular binding rate constant kon (or k1) is 6 × 106 M−1 s−1 (k2 / KD1), consistent with the previous measurement of 3 × 106 M−1 s−1 using DNA(+T)2-Ap.30 These rate constants yield a KD (koff / kon) of 10 – 20 nM for the final mismatch recognition complex, in accord with KD values obtained from equilibrium binding experiments (Fig. 1b, Fig. 2a).29,30

The kinetic data with DNA(+T)TAMRA and MutSIAANS show that mismatch recognition occurs minimally via a two-step mechanism in which an initial low-affinity complex converts to a high-affinity complex with accompanying conformational changes in (at least) MutS domains I. Given strong structural evidence that DNA is bent in the mismatch recognition complex,7,8,18 we asked whether DNA bending follows the same two-step mechanism. A 42 nt DNA substrate was synthesized with AlexaFluor 488 (AF488) and AlexaFluor 594 (AF594) positioned as a FRET donor-acceptor pair 12 and 14 nt from the central T-bulge.50 MutS binding to DNA(+T)AF488-AF594 increases FRET between the two dyes, indicating closer proximity due to DNA bending in the complex (spectra shown in Fig. S2a). Equilibrium titration of DNA(+T)AF488-AF594 with MutS shows that the increase in FRET efficiency (ET) is specific to the T-bulge, since it is not detected with matched DNAAF488-AF594 (Fig. 2d). The rate of this conformational change in DNA was measured by mixing increasing concentrations of MutS with DNA(+T)AF488-AF594 in the stopped-flow, and monitoring decrease in donor fluorescence and corresponding increase in acceptor fluorescence over time μn a control experiment, donor only labeled DNA(+T)AF488 mixed with MutS does not display any signal change in the same time frame; Fig. S2b). In Fig. 2e, a representative kinetic trace at 0.5 μM MutS is fit well by a single exponential function, yielding an apparent DNA bending rate k = 1.8 ± 0.07 s−1 (note: no second slower phase is detectable even at longer observations times). This bending rate is similar to the binding rate obtained with DNA(+T)TAMRA (k = 1.3 s−1 at 0.5 μM MutS; Fig. 2b). In this case also, the plot of rate versus MutS concentration is hyperbolic (Fig. 2f), reaching a maximum of 27 ± 4 s−1 with an apparent K1/2 (or KD1) of 4 ± 1 μM. Thus, the DNA FRET data also support a two-step mechanism of MutS binding to a mismatch, and the matching rates reveal that formation of the high-affinity mismatch recognition complex involves concerted conformational changes in both MutS and DNA following weak initial interaction.

One other observation is that the equilibrium binding experiment with DNA(+T)AF488-AF594 yields an apparent KD of 1 nM (Fig. 2d), which is substantially lower than the 15 – 25 nM value obtained with other fluorophore-labeled DNA substrates—DNA(+T)TAMRA (Fig. 2a) and DNA(+T)2-Ap30—or with MutSIAANS (Fig. 1b). The rate of MutS dissociation from a pre-equilibrated MutS•DNA(+T)AF488-AF594 complex is also much slower (0.008 s−1; data not shown) than from MutS•DNA(+T)TAMRA or MutS•DNA(+T)2-Ap (0.05 s−1; Fig. S1a), which accounts for the inordinately low KD. These data indicate an artifact with the AF-labeled substrate, in that after the mismatch-specific complex is formed, MutS can interact at a slower rate (over seconds) with AF dye(s) to form a stable off-pathway complex that is detected at longer time scales (e.g., in equilibrium experiments). Such non-specific interaction has been reported between E. coli MutS and AF dyes as well, requiring caution in experimental design and data interpretation.50

Rapid ATP binding- and hydrolysis-induced switching of MutS conformations

Recently, an smFRET study of MutS-C42A/M88C labeled with fluorescent donor and acceptor dyes (one each per domain I Cys 88 residue in the dimer) revealed that nucleotide binding to ATPase domains V leads to large conformational changes in mismatch binding domains I (Fig. 1a). The non-hydrolysable ATP analog, ATPγS, stabilizes free MutS in a high FRET state (domains I close to each other) whereas ADP stabilizes it in low FRET state (domains I far apart).28 We examined the kinetics of this allosteric signaling with MutSIAANS to better understand the coupling mechanism between ATPase and mismatch recognition/repair activities.

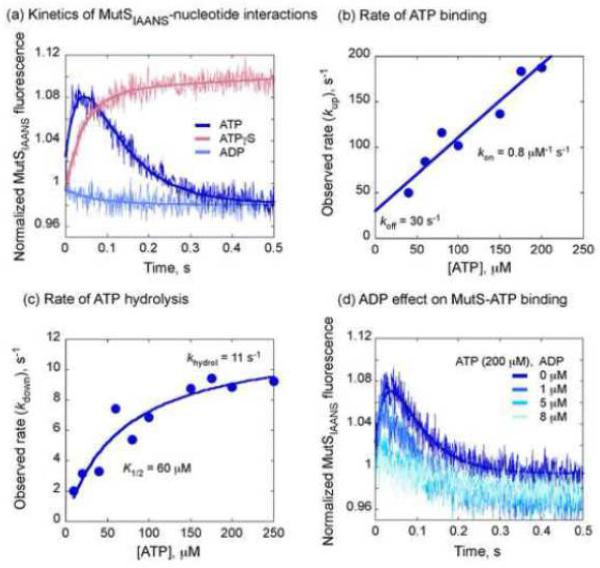

Mixing MutSIAANS with ATP in a stopped-flow leads to an increase and then decrease in IAANS fluorescence (Fig. 3a, kinetic traces shown at 100 μM nucleotide). A similar experiment with ATPγS shows only an increase in signal (note: the rate is about 5 times slower, indicating significant kinetic differences in MutS binding and response to ATPγS relative to ATP, which may complicate analysis of the mechanism30). And finally, a relatively slight decrease in signal is detected with ADP. These results suggest that the rise and drop in MutSIAANS fluorescence correspond to changes in protein conformation on ATP binding (consistent with ATPγS data) and ATP hydrolysis (consistent with ADP data), respectively (Fig. 3a). This hypothesis was tested by measuring the rates of the two phases at increasing ATP concentrations. Both rates, kup and kdown (from double exponential fits), vary with ATP as shown in Fig. 3b and 3c, respectively. kup increases linearly with ATP and the slope yields an apparent bimolecular ATP binding constant kon(ATP) = 0.8 × 106 M−1 s−1, which is similar to the previously reported value of 0.25 × 106 M−1 s−1 measured with 32P-ATP.35 Thus, on ATP binding to MutS domains V, the conformational change in domains I happens so fast as to appear concerted with the binding rate. Notably, the y-intercept yields an apparent dissociation rate koff(ATP) = 30 s−1, providing a KD of 37.5 μM for the ATP binding/MutS isomerization. Previous equilibrium binding experiments with 32P-ATP, 35S-ATPγS and 32P-ADP have shown that MutS binds nucleotides asymmetrically with KD values of ~ 2 μM and ~ 30 μM for high and low affinity sites, respectively.35 Now, the MutSIAANS signal reveals that the protein isomerizes upon ATP binding to the weak site (KD = 37.5 μM; Fig 3b). Moreover, as shown in Fig. 3d, the tight site must also bind ATP for this change to occur, since it is blocked when MutSIAANS is pre-equilibrated with 8 μM ADP (to occupy the tight site) prior to mixing with ATP (200 μM).

Fig. 3.

A binary switch in MutS domain I conformations driven by ATP binding and hydrolysis. (a) Stopped-flow traces of MutSIAANS (0.1 μM) mixed with various nucleotides show increase in fluorescence with ATPγS, slight decrease with ADP, and biphasic increase and decrease with ATP (100 μM). (b) The rate of the first phase increases linearly with ATP concentration with a slope of 0.8 μM−1 s−1 (apparent kon(ATP)) and a y-intercept of 30 s−1 (apparent koff(ATP)). (c) The rate of the second phase increases hyperbolically with ATP concentration to a maximum of 11 s−1, with an apparent K1/2 of 60 μM. (d) Pre-incubation with low concentrations of ADP (sufficient to fill the high affinity nucleotide-binding site) blocks ATP binding-induced increase in MutSIAANS fluorescence.

Fig. 3c shows that the rate of the second phase, kdown, increases hyperbolically with ATP concentration and reaches a maximum 11 ± 1 s−1. This is exactly the rate of ATP hydrolysis and phosphate (Pi) release measured previously with 32P-ATP and a fluorescent Pi sensor, respectively.35 Once the two ATP binding sites on MutS are occupied, the high affinity site catalyzes a burst of hydrolysis and Pi release (khydrol = 10 – 12 s−1 at 40 °C), followed by ~ 30-fold slower steady state rate (kcat = 0.3 – 0.4 s−1) in the absence of DNA (Fig. S3a). Thus, MutSIAANS data again reveal that on ATP hydrolysis in domains V, the conformational change in domains I happens so fast as to appear concerted with the hydrolysis rate. Moreover, the plot yields a high dissociation constant, K1/2 (KD) = 60 ± 15 μM, confirming that rapid ATP hydrolysis and corresponding MutS isomerization occur after both sites on the MutS dimer are occupied with ATP.

We also utilized KinTek Explorer51 to globally (simultaneously) fit MutSIAANS kinetic traces at all the different ATP concentrations with a simple binary model of ATP binding and hydrolysis. The analysis yielded similar kinetic parameters (kon(ATP) = 0.5 × 106 M−1 s−1, koff(ATP) = 15 s−1, khydrol = 9.2 s−1; Fig. S3b).

| (2) |

These findings reveal, in conjunction with spatial information from smFRET data28 that (a) when both high and low affinity binding sites are occupied by ATP, MutS switches immediately to a state with domains I proximal to each other, and (b) upon a burst of ATP hydrolysis at the high affinity site, MutS switches back immediately to a state with domains I distal to each other. This catalytic cycle can resume only after ADP dissociates from the high affinity site.

Slow ATP-induced conformational changes in MutS•mismatch complex control downstream steps in MMR

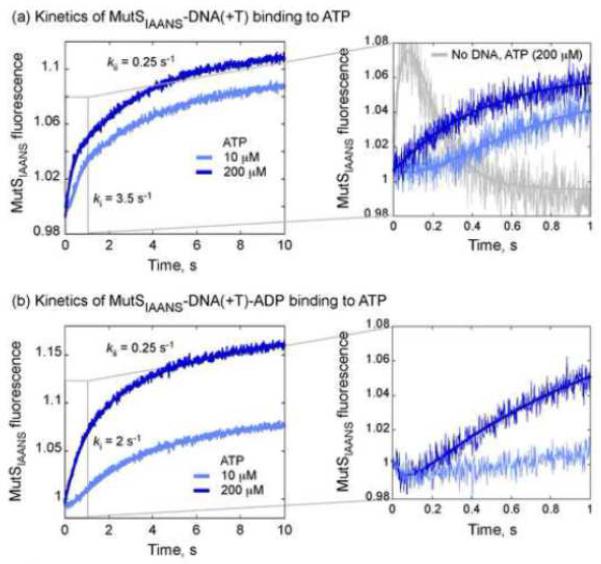

Once MutS recognizes a mismatch, ATP hydrolysis is suppressed (Fig. S3a) and the protein attains an ATP-bound state in which it can leave the site but stay topologically linked to DNA.24,27,28,41 We utilized MutSIAANS fluorescence to monitor ATP-driven changes in protein conformation following mismatch recognition. Fig. 4a shows two representative stopped-flow traces from mixing pre-equilibrated MutSIAANS•DNA(+T) complex with increasing concentrations of ATP. At low ATP (10 μM), three distinct phases are observed—a lag followed by biphasic increase in signal. The lag phase exhibits ATP concentration dependence, shortening with higher ATP until it becomes undetectable (Fig. 4a, expanded view). The rates of the two subsequent phases, estimated by double exponential fitting, remain constant at 3.5 ± 0.4 s−1 and 0.27 ± 0.02 s−1. These results reveal a substantially slower and more complex response to ATP binding from MutSIAANS•DNA(+T) complex versus MutSIAANS alone (Fig. 4a, grey trace: MutSIAANS alone mixed with 200 μM ATP). The kinetic data from all ATP concentrations were fit globally with a simple 3-step model in which ATP binding to MutS•DNA(+T) is followed by two concentration-independent steps in the reaction (Fig. S4a).

| (3) |

Fig. 4.

Mismatch recognition blocks rapid ATP binding/hydrolysis-induced MutS domain I switching. (a) Stopped-flow traces of MutSIAANS•DNA(+T) complex (0.1 μM) mixed with varying ATP concentrations (10 μM, light blue; 200 μM, dark blue) show an initial lag phase that disappears with increasing ATP, and is followed by a biphasic increase in fluorescence at maximal rates of 3.5 s−1 and 0.25 s−1. (b) The same experiment performed in the presence of 8 μM ADP (sufficient to fill the high-affinity site) shows a longer lag phase that persists even at high ATP concentrations (200 μM, dark blue). The lag is followed again by a biphasic increase in fluorescence at maximal rates of 2 s−1 and 0.25 s−1.

The lag phase tracks the ATP binding rate and is best fit with kon(ATP) (k1) = 0.5 × 106 M−1 s−1 and KD(ATP) ≤ 2 μM (i.e., ATP binding to the high affinity site).35 Subsequently, this ternary complex undergoes two conformational changes with best-fit rate constants of k2 = 3.7 s−1 and k3 = 0.25 s−1. What occurs during these steps other than changes in domains I was not discernable from the MutSIAANS signal alone, and was examined further with fluorophore labeled DNA.

We also performed the experiments described above with MutSIAANS•DNA(+T) complex pre-equilibrated with 8 μM ADP (to occupy the high affinity site). Rapid hydrolysis of one ATP per MutS dimer (in the absence of mismatched DNA),34,35 followed by slow turnover likely limited by ADP release,13,40 implies that one ADP-bound MutS is predominant in steady state and is involved in mismatch search and recognition. Mixing the ADP-bound MutSIAANS•DNA(+T) complex with ATP also yields kinetic traces with a lag phase followed by biphasic increase in fluorescence (Fig. 4b). Fitting the data with a 3-exponential function provides apparent rates of 1.5 – 2 s−1 and 0.25 s−1 for the latter two steps, similar to the rates obtained in the absence of ADP (Fig. 4a). The lag phase, however, is much longer and is detectable even at 200 μM ATP (Fig. 4b). This result implies an extra step in the reaction with the ADP-bound complex that limits ATP-induced conformational changes in domains I. We suspect that this step involves ADP dissociation from the high affinity site. Inclusion of this step prior to ATP binding in model (3) described above, and global fitting of kinetic data from all ATP concentrations yields good fits with KD(ADP) ~ 1 μM (Fig. S4b).

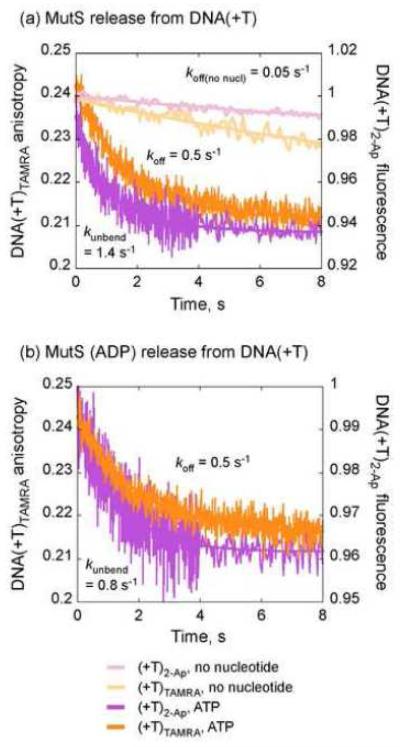

In order to explore the nature of the two slow steps following ATP binding to MutS•DNA(+T), we measured the kinetics of MutS release from the mismatch/DNA with two different fluorescent probes: (i) DNA(+T)2-Ap, in which fluorescence of 2-Ap adjacent to the T-bulge serves as an on-site reporter of MutS-mismatch interaction, and (ii) DNA(+T)TAMRA, in which fluorescence anisotropy of TAMRA at the duplex end serves as a generic reporter of MutS-DNA interaction. First, MutS•DNA(+T)2-Ap complex (with high 2-Ap fluorescence due to bent DNA) was mixed with excess unlabeled trap DNA(+T) in the absence or presence of ATP (500 μM), and the change in signal was monitored over time. In the absence of nucleotides, 2-Ap fluorescence is quenched at a slow rate of 0.053 ± 0.001 s−1 (Fig. 5a, Fig. S1a), consistent with our previous report.30 In the presence of ATP, however, 2-Ap quenching occurs much faster at 1.4 ± 0.15 s−1 (Fig. 5a). Similar experiments performed with MutS•DNA(+T)TAMRA complex yield rates of 0.051 ± 0.001 s−1 in the absence of nucleotides (Fig. 5a, Fig. S1a) and 0.55 ± 0.01 s−1 in the presence of ATP (Fig. 5a). Interestingly, while both DNA substrates report the same minimal rate in the absence of nucleotides (0.05 s−1), the rates differ by ~ 3-fold in the presence of ATP. We also performed a control experiment in which both probes were located on the same DNA substrate, and the results were consistent—upon addition of ATP, 2-Ap quenching occurs at 2.8 ± 0.3 s−1, 4-fold faster than the decrease in TAMRA anisotropy at 0.7 ± 0.01 s−1 (Fig. S5). The faster 2-Ap quenching rate likely reflects ATP-induced isomerization of the complex whereby DNA becomes less bent. The slower decrease in TAMRA anisotropy likely reflects ATP-induced release of MutS from the T-bulge (followed by rapid sliding off the short linear duplex). We propose that the first conformational change in MutS domains I (Fig. 4a, k2 = 3.5 s−1) correlates with unbending of DNA, as reported by 2-Ap quenching, and the second, slower change in domains I (Fig. 4a, k3 = 0.27 s−1) results in formation of the MutS sliding clamp that releases the mismatch, as reported by TAMRA anisotropy. Analogous experiments were performed with the ADP-bound MutS•DNA(+T) complex as well. ATP-induced 2-Ap quenching occurs at 0.8 ± 0.03 s−1 (Fig. 5b) and decrease in TAMRA anisotropy occurs at 0.5 ± 0.01 s−1 (Fig. 5b). The difference in rates does not appear significant in this case, likely because a fraction of ADP-bound MutS dissociates directly from the mismatch prior to ATP binding (koff = 1 s−1; Fig. S1b) and cannot be resolved by bulk kinetic analysis.

Fig. 5.

Two-step release of the T-bulge (2-Ap fluorescence) and DNA (TAMRA anisotropy) by MutS in the presence of ATP. (a) Stopped-flow traces for MutS•DNA(+T)2-Ap complex (0.03 μM) mixed with unlabeled DNA(+T) trap (3 μM) without (pink) and with 500 μM ATP (purple), and for MutS•DNA(+T)TAMRA complex (0.06 μM) mixed with unlabeled DNA(+T) (6 μM) without (salmon) and with ATP (orange). Single exponential fits yield rates of 0.05 s−1 for both DNA substrates without nucleotides, and 1.4 s−1 for MutS•DNA(+T)2-Ap and 0.55 s−1 for MutS•DNA(+T)TAMRA with ATP. (b) Similar experiments as in (a) except the complexes were pre-equilibrated with ADP (8 μM) prior to mixing with unlabeled DNA and ATP. Single exponential fits yield rates of 0.8 s−1 for MutS•DNA(+T)2-Ap and 0.5 s−1 for MutS•DNA(+T)TAMRA with ATP.

DISCUSSION

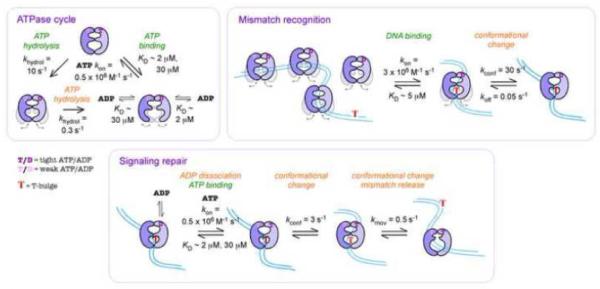

MutS performs the essential task of locating base-pair errors in DNA and initiating their repair. Our goal in this study was to identify transient MutS actions, determine their timing and assess their coupling to mismatched DNA binding/release and ATP binding/hydrolysis. We investigated the system with a combination of equilibrium and ensemble kinetics methods that measured changes in MutS conformation (domain I reporter: MutSIAANS fluorescence), interactions with DNA (binding/release reporter: DNA(+T)TAMRA fluorescence anisotropy; bending reporter: DNA(+T)AF488-AF594 FRET; mismatch on-site reporter: DNA(+T)2-Ap fluorescence), and ATP hydrolysis (Pi release reporter: PBPMDCC fluorescence) under the same experimental conditions. This multi-sensor approach identified key new steps, and provided rate information on these and other known steps in the pathway. Importantly, with multiple views of each transient event (from the perspective of different reactants) and previous structural, equilibrium and single molecule data, we were able to construct the most detailed kinetic model thus far of the mechanism of action of MutS in mismatch recognition and initiation of repair (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

A kinetic model for ATPase-linked MutS actions on DNA in mismatch repair. When not bound to a mismatch, the MutS ATPase cycle involves rapid ATP binding to the high- and low-affinity sites (which closes domains I and IV, rendering MutS unable to load on DNA), followed by fast and slow ATP hydrolysis at the these sites, respectively. ADP-bound and nucleotide-free MutS species interconvert between domains I/IV in open and closed states, with the 2-ADP species predominantly in open state (unstable on DNA). When MutS arrives at a mismatch, weak initial binding is followed by a slow recognition event in which both MutS and DNA change conformation to form a high-affinity complex (domains I closure and insertion into mismatch, DNA kinking). Slow dissociation of any ADP on MutS allows rapid ATP binding to both sites, and is followed by multiple rate-limiting conformational changes in both MutS and DNA that enable formation of a MutS sliding clamp (including domains I de-insertion from mismatch, DNA unbending). In this ATP-bound state, MutS can bind MutL and move away from the mismatch while remaining topologically linked to DNA, and initiate mismatch repair.

When not bound to a mismatch, MutS catalyzes an ATPase cycle in which both subunits bind ATP rapidly, one with high affinity (S1) and the other with low affinity (S2). The S1 site undergoes rapid ATP hydrolysis and Pi release, followed by a much slower steady state rate that is limited by ATP hydrolysis at S235,37 and/or ADP release at S1 (Sawant, Hingorani, unpublished data); this reaction is depicted in Fig. 6 with rate and equilibrium constants for T. aquaticus MutS measured at 25 °C and/or 40 °C (< 2-fold difference). In the apo MutS crystal structure (no nucleotides, no DNA), both domains I and the lower DNA-binding domains IV are unresolved,18 indicating an open/flexible state that allows DNA access to binding sites within the dimer (Fig. 1a), whereas ATP- or ATPγS-bound MutS cannot interact stably with DNA,30 indicating a closed state in which access is restricted. We also know from smFRET data that domains I fluctuate between open and closed states in apo MutS, and the equilibrium is shifted toward closed state with ATPγS and open state with ADP.28 This study shows that MutS flips instantaneously between these two states on ATP binding and hydrolysis, respectively; i.e., the conformational changes occur very fast, limited simply by the rate of ATP binding to both S1 and S2 and then ATP hydrolysis at S1 (Fig. 3). These kinetics reflect robust allosteric signaling from the ATPase domains V to the distant mismatch binding domains I—leading to rapid population in steady state of one- or two-ADP bound MutS species that are open to binding DNA30,39 (note: nucleotide-free MutS may not be highly populated in steady state, but it forms very long-lived complexes with mismatched DNA compared with ADP-bound MutS, and may therefore contribute significantly to mismatch recognition as well; Fig. S1). One other interesting finding is that ATP binding-induced domain I closure occurs almost 20-fold faster than subsequent ATP hydrolysis at the highest ATP concentration tested (185 s−1 versus 11 s−1, respectively, at 200 μM ATP; Fig. 3). Thus, there exists at least one slow step after domain I closure that limits ATP hydrolysis. We suggest that this transition controls formation of the ATP-bound MutS clamp following mismatch recognition, as discussed below.

Nucleotide-free and ADP-bound S. cerevisiae MutSα24 and T. aquaticus MutS26,27 are known to slide along the helical contour of DNA, presumably scanning the duplex for mismatch target sites (KD ~ 1 – 20 μM for matched DNA).23,26,29 MutSα was also observed binding mismatches by 3D collision.24 We had previously reported fast bimolecular association at 3 × 106 M−1 s−1 between nucleotide-free or ADP-bound MutS and DNA(+T)2-Ap, which specifically reports MutS interaction with the mismatch.30 The rate was confirmed in this study with DNA(+T)TAMRA and by smFRET measurements at low reactant concentrations.26,52 As depicted in Fig. 6, this initial contact between MutS and DNA establishes a weak equilibrium (KD = 5 μM), and is followed by rate-limiting isomerization (kconf = 30 s−1) that results in a high affinity complex (KD = 10 – 20 nM); note: unlike DNA(+T)2-Ap, DNA(+T)TAMRA could be titrated with high concentrations of MutS without background interference from tryptophan fluorescence, and thus revealed the limiting step in mismatch binding (Fig. 2). Similar DNA binding kinetics were observed for one ADP-bound MutS as well (data not shown). MutS and DNA undergo concerted conformational changes during this step (Figs. 1, 2)—likely characterized by inward movement of domains I whereby Phe-X-Glu motif on the S1 subunit inserts into the minor groove at the mismatch,18 and sharp bending of DNA at the site to facilitate this interaction (seen in all crystal structures of MutS-mismatched DNA complexes).7,8,18 In a recent smFRET study of T. aquaticus MutS labeled on domains IV, a transient species was detected prior to formation of the high affinity MutS•DNA(+T) complex.26 Although the temporal resolution wasn't sufficient to define the species, it could well be the initial complex determined in our study. In contrast, the final complex has a long half-life of 10 – 20 s, reflecting high stability (Fig. S1).26,30 From earlier studies of S. cerevisiae MutSα, we know that the protein binds to a bona fide mismatch, G:T, at the same fast rate as a possible mismatch, 2-Ap:T (kon = 2 × 107 M−1 s−1), but the final complex with G:T has 100-fold higher stability than the complex with 2-Ap:T (t1/2 = 60 s versus 0.6 s, respectively).31 Therefore, we consider rate-limiting isomerization of an initial weak complex to the tight, stable, mismatch-specific complex a fundamental recognition event that defines MutS transition from search to repair mode and licenses subsequent steps in the MMR pathway.

As reported previously, after mismatch recognition, the MutS ATPase mechanism is radically altered such that ATP hydrolysis at S1 is suppressed by ≥ 30-fold (Fig. S3).35,37 We now find that despite continued rapid binding of ATP to S1,35 mismatch-bound MutS does not switch instantaneously to the closed state as seen with apo MutS (Fig. 3). Instead there is a lag during ATP binding, followed by slow multi-step conformational changes in domains I, wherein the first step (kconf = 3 s−1; Fig. 4) is concerted with DNA unbending at the mismatch site (kunbend = 1.4 – 2.8 s−1; Fig. 5, Fig. S5). This slow response to ATP binding (3 s−1 for MutS•DNA(+T) versus 185 s−1 for MutS at 200 μM ATP) indicates that retraction of domains I from the mismatch is restricted and requires that the DNA straighten out at the same time. At this stage, MutS is still located at the mismatch (MutS complexes with unbent mismatched DNA have been visualized by both AFM and smFRET).52–54 In the next step, domains I undergo further adjustment (kconf = 0.3 s−1; Fig. 4), which results in MutS releasing the mismatch completely as a sliding clamp (koff = 0.5 s−1; Fig. 5); note: MutS slips off the ends of our short DNA(+T)TAMRA substrate. Measurements of smFRET in between MutS domains I, or between domains I and the mismatch site, indicate that this transition occurs in two steps—an intermediate species forms at 0.25 s−1 and then MutS leaves at 0.7 s−1.28 The net rate of these two steps, 0.2 s−1, is comparable to our ensemble measurement of 0.3 – 0.5 s−1 (smFRET between MutS domains IV and the mismatch site also yielded a release rate of 0.3 s−1).26,27 Thinking back on the relatively long interval between ATP binding and hydrolysis even in the absence of DNA (Fig. 4), it is likely that after binding ATP free MutS also samples these intermediate states that are refractory to ATP hydrolysis. In that case, however, without mismatch-induced stabilization of the final ATP-bound conformation, ATP hydrolysis quickly resets MutS to an ADP-bound or nucleotide-free state that can bind DNA again (Fig. 6). Finally, we have also found that ATP induced changes in domain I are stalled when the S1 site of MutS is occupied with ADP (Fig. 3d). MutS binding to a mismatch stimulates ADP release;13,40 nonetheless, this step causes additional delay in MutS transition to a sliding clamp (Figs. 4, Fig. S4).

In the clamp state, MutS domains I appear to be ~ 70 Å apart,28 unable to contact the mismatch, while domains IV remain closed, allowing the protein to diffuse rapidly on DNA.24,26–28 Single-molecule imaging of S. cerevisiae MMR proteins has shown that MutLα binds to MutSα present a G:T mismatch (without nucleotides or with ADP), and addition of ATP results in diffusion of the MutS•MutL complex along DNA. The initial MutS•MutL complex at the mismatch is less stable than the ATP-bound complex, which remains topologically linked to DNA even at > 500 mM NaCl.24 According to chemical cross-linking analysis of E. coli MMR proteins, after ATP binds to G:T mismatch-bound MutS, domains I come in close proximity to MutL.43T. aquaticus MutS kinetic data show that after mismatch recognition, nucleotide-free or ADP-bound MutS undergoes stepwise transition to a sliding clamp on binding ATP (Fig. 6). During this time MutL could first localize to the MutS•mismatch complex and then bind MutS tightly as domains I move out of the mismatch site. This domain I-mediated shift in MutS binding affinity from mismatch to MutL imposes an order of events that is strictly dependent on mismatch recognition. The MutS clamp apparently doesn't undergo ATPase turnover until it loses contact with duplex DNA (T. aquaticus and S. cerevisiae MutS ATPase kcat values match their DNA dissociation rates).30,31 This strong block on ATP hydrolysis implies that MutL could interact with ATP-bound MutS after it releases the mismatch, although this possibility awaits testing. It also ensures a long-lived post-mismatch recognition MutS•MutL complex on DNA until the next transition event in the repair pathway.26 Our data are consistent with the molecular switch model of MutS actions on DNA.41 We have added temporal details revealing that the switch is neither rapid nor binary—which is likely important for ordered assembly of MutS•MutL complexes at the mismatch, followed by a search for strand discrimination signals on DNA that enable nicking of the error-containing strand.55–57

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Proteins and DNA

T. aquaticus wild type MutS and MutS-C42A/M88C and MutS-F39A/C42A/M88C mutants were purified from E. coli BL21(DE3) cells by Q-sepharose chromatography (50 – 350 mM NaCl gradient) in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5% w/v glycerol), followed by (NH4)2SO4 precipitation (24 %) and dialysis against buffer A.35 MutS-C42A/M88C was labeled at C88 with 2-(4'-(iodoacetamido)anilino)naphthalene-6-sulfonic acid (IAANS; Life Technologies) by gradual addition of 25x molar excess of dye (dissolved in DMF) to 10 μM protein, pre-incubated for 15 min with 100 μM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP; Sigma-Aldrich) in buffer A, and further incubation for 1 hour at 25 °C then 12 hours at 4 °C with slow mixing. The reaction was terminated with 5 mM DTT, the protein concentrated by centrifugal filtration, and free dye removed by gel-filtration through a Bio-Gel P-6 (Bio-Rad) column (1.5 × 20 cm) in buffer A. Labeling efficiency was determined from absorbance measurements at 280 nm and 326 nm as per manufacturer instructions (MutS monomer ε = 52,720 M−1cm−1 at 280 nm; IAANS ε = 27,000 M−1cm−1 at 326 nm), corrected for buffer and IAANS absorbance at 280 nm; typical labeling efficiency was 1.6:1 of IAANS:MutS dimer.

DNAs were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies Inc., without any modification, or with 2-Ap located 3' to the T-bulge, or with internal or 3' end amino linkers for labeling with fluorophores: 5-(6)-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA), AlexaFluor 488 or AlexaFluor 594 (Life Technologies). The sequences are: +T = 5'-ATGTGAATCAGTATGGTA(+T)ATATCTGCTGAAGGAAAT* -3'; +Tcomplement = 5'-ATTTCCTTCAGCAGATATTACCATACTGATTCACAT-3'; AF+T = 5'-TCCATGGT*AATCAGTATGGTA(+T)ATATCTGCTGAAGGAAATTA-3'; AF+Tcomplement = 5'-TAATTTCCT*TCAGCAGATATTACCATACTGATTACCATGGA-3' (+T denotes T-bulge; A denotes 2-Ap; T* denotes NH2 linker-modified nucleotide for fluorophore labeling). Unlabeled DNA substrates were of the same sequences, and corresponding matched DNAs contained A:T or G:C in place of +T. All DNAs were purified by urea gel electrophoresis and labeled as described.30 Duplex DNAs were prepared by mixing single strands in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl (1:1.15 ratio labeled:unlabeled), heating to 95 °C for 2 min and slow cooling to 25 °C, followed by non-denaturing PAGE to confirm >95 % annealed product. ATP, ATPγS and ADP nucleotides were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Equilibrium analysis of MutS-DNA interactions

MutS-DNA binding was measured with MutSIAANS, DNATAMRA and DNAAF488-AF594 on a FluoroMax-3 fluorometer (Jobin-Yvon Horiba Group; Edison, NJ). MutSIAANS or MutS-F39AIAANS (0.025 μM) were titrated with T-bulge or matched DNA (0 – 0.2 μM) in buffer B (20 mM Hepes-NaOH, pH 7.7, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2) at 40 °C and fluorescence intensity measured after 2 min of mixing (λEX = 326 nm, λEM = 445 nm). The data were corrected for slight IAANS photobleaching as described58, the first point scaled to 1 and plotted versus DNA concentration. DNATAMRA (0.01 μM) was titrated with MutS or MutS-F39A (0 – 0.2 μM) at 25 °C and excited with vertically polarized light (λEX = 555 nm, λEM = 582 nm). Fluorescence anisotropy was calculated from the emitted vertical (IVV) and horizontal (IVH) polarized fluorescence intensities (IVV − GIVH/IVV + 2GIVH; G is the calculated grating correction factor) and plotted versus MutS concentration. DNAAF488-AF594 (0.01 μM) was titrated with MutS (0 – 0.05 μM) at 25 °C, and AF594 acceptor fluorescence (λEX = 470 nm, λEM = 615 nm) was converted to FRET efficiency:

ET is FRET efficiency, IAD and IA are fluorescence intensities of DNAAF488-594 and DNAAF594, respectively, and εA (2000 M−1 cm−1) and εD (71000 M−1 cm−1) are the extinction coefficients of AF488 and AF594 at 470 nm. The apparent dissociation constant (KD) for the interaction was obtained by fitting all the data to a quadratic equation by non-linear regression using KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software):

Fmin and Fmax are initial and final fluorescence intensities, respectively; Mt and Lt are total macromolecule and ligand concentrations, respectively. Each type of DNA binding experiment was repeated at least thrice, and the KD values were all within the reported errors.

Kinetic analysis of MutS-DNA interactions

The kinetics of MutS-DNA binding were measured with MutSIAANS, DNATAMRA and DNAAF488-AF594 on a KinTek SF-2001 stopped-flow instrument (KinTek Corp., Austin, TX). MutSIAANS or MutS-F39AIAANS (0.2 μM) was mixed in 1:1 ratio with DNA(+T) (1 – 20 μM) in buffer B at 40 °C, and fluorescence intensity measured over time (λEX = 326 nm, λEM > 350 nm). Two or more independent experiments were performed, and three or more traces within each experiment were averaged (1000 data points each), corrected for slight IAANS photobleaching and then fit to a double exponential function for estimation of rate constants. DNA(+T)TAMRA (0.12 μM) was mixed in 1:1 ratio with MutS (1 – 20 μM) at 40 °C, and fluorescence anisotropy measured over time (polarized, λEX = 555 nm, λEM > 570 nm). Two or more independent experiments were performed, and three or more traces within each experiment were averaged and fit to a single exponential function by non-linear regression using KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software). DNA(+T)AF488-AF594 (0.06 μM) was mixed in 1:1 ratio with MutS (1 – 20 μM) at 25 °C, and AF594 fluorescence measured over time (λEX = 470 nm, λEM = 610 – 630 nm). Two or more independent experiments were performed, and three or more traces within each experiment were averaged and fit to a single exponential function.

Nucleotide effects on MutS•DNA complex dissociation were measured by mixing MutS (1.2 μM) pre-incubated with DNA(+T)TAMRA (0.12 μM), ± ADP (8 μM), in 1:1 ratio with unlabeled DNA(+T) (12 μM) and ATP (4 mM), ± ADP (8 μM), in buffer B at 40 °C. TAMRA fluorescence anisotropy was measured over time (polarized, λEX = 555 nm, λEM > 570 nm). Two or more independent experiments were performed, and three or more traces within each experiment were averaged and fit to a single exponential function for estimation of rate constants. Mismatch site-specific changes in MutS•DNA complex were measured by mixing MutS (0.4 μM) pre-incubated with DNA(+T)2-Ap (0.06 μM), ± 8 μM ADP, in 1:1 ratio with unlabeled DNA(+T) (6 μM) and ATP (1 mM), ± 8 μM ADP, in buffer B at 40 °C. 2-Ap fluorescence was measured over time (λEX = 315 nm, λEM > 350 nm) and corrected for slight 2-Ap photobleaching and intrinsic MutS fluorescence; three or more traces were averaged and fit to a single exponential function.

Kinetic analysis of MutS-nucleotide interactions

Nucleotide effects on MutSIAANS fluorescence were measured on the stopped-flow by mixing protein (0.2 μM) in 1:1 ratio with ATP (20 μM - 1 mM), ADP (200 μM) or ATPγS (200 μM) in buffer B at 40 °C. Similar experiments were performed with MutSIAANS (0.2 μM) pre-incubated with ADP (1 – 8 μM) and mixed in 1:1 ratio with ATP (500 μM) and ADP (1 – 8 μM). Two or more independent experiments were performed, and three or more traces within each experiment were averaged, corrected for slight IAANS photobleaching and then fit to single or double exponential functions for estimation of rate constants. Nucleotide effects on MutSIAANS•DNA(+T) were measured by mixing protein (0.2 μM) pre-incubated with DNA(+T) (1μM), ± 8 μM ADP, in 1:1 ratio with ATP (20 μM - 2 mM) and DNA(+T) (1 μM), ± 8 μM ADP. Two or more independent experiments were performed, and three or more traces within each experiment were averaged, corrected for slight IAANS photobleaching and then fit to single or multiple exponential functions for estimation of rate constants. The data were also fit globally to minimal models using KinTek Explorer software,51 as detailed in Results.

Supplementary Material

Highlights

Transient kinetic analysis reveals MutS conformational dynamics in mismatch repair

Coupled, slow isomerization of MutS and DNA underlies specific mismatch recognition

ATP binding and hydrolysis trigger rapid switching of MutS conformations

Both ATP hydrolysis and rapid MutS switching are stalled after mismatch recognition

Instead MutS-mismatch-ATP complex undergoes stepwise isomerization to signal repair

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the NSF (MCB 1022203). We thank Dr. Miho Sakato and Dr. Ishita Mukerji for insightful discussions.

Abbreviations

- 2-Ap

2-aminopurine

- ATPγS

adenosine-5'-(γ-thio)-triphosphate

- FRET

Förster resonance energy transfer

- IAANS

2-(4'-(iodoacetamido)anilino)naphthalene-6-sulfonic acid

- TAMRA

5-(and 6-) carboxytetramethylrhodamine

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kunkel TA, Erie DA. DNA Mismatch Repair. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:681–710. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iyer RR, Pluciennik A, Burdett V, Modrich PL. DNA mismatch repair: functions and mechanisms. Chem Rev. 2006;106:302–23. doi: 10.1021/cr0404794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiricny J. The multifaceted mismatch-repair system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:335–46. doi: 10.1038/nrm1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li GM. Mechanisms and functions of DNA mismatch repair. Cell Res. 2008;18:85–98. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsieh P, Yamane K. DNA mismatch repair: Molecular mechanism, cancer, and ageing. Mech Ageing Dev. 2008;129:391–407. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plazzer JP, Sijmons RH, Woods MO, Peltomaki P, Thompson B, Den Dunnen JT, Macrae F. The InSiGHT database: utilizing 100 years of insights into Lynch Syndrome. Fam Cancer. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10689-013-9616-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamers MH, Perrakis A, Enzlin JH, Winterwerp HH, de Wind N, Sixma TK. The crystal structure of DNA mismatch repair protein MutS binding to a G x T mismatch. Nature. 2000;407:711–7. doi: 10.1038/35037523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warren JJ, Pohlhaus TJ, Changela A, Iyer RR, Modrich PL, Beese LS. Structure of the human MutSa DNA lesion recognition complex. Mol Cell. 2007;26:579–92. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta S, Gellert M, Yang W. Mechanism of mismatch recognition revealed by human MutSb bound to unpaired DNA loops. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:72–8. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ban C, Yang W. Crystal structure and ATPase activity of MutL: implications for DNA repair and mutagenesis. Cell. 1998;95:541–52. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81621-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guarne A, Ramon-Maiques S, Wolff EM, Ghirlando R, Hu X, Miller JH, Yang W. Structure of the MutL C-terminal domain: a model of intact MutL and its roles in mismatch repair. Embo J. 2004;23:4134–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ban C, Yang W. Structural basis for MutH activation in E.coli mismatch repair and relationship of MutH to restriction endonucleases. Embo J. 1998;17:1526–34. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acharya S, Foster PL, Brooks P, Fishel R. The coordinated functions of the E. coli MutS and MutL proteins in mismatch repair. Mol Cell. 2003;12:233–46. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kadyrov FA, Holmes SF, Arana ME, Lukianova OA, O'Donnell M, Kunkel TA, Modrich P. Saccharomyces cerevisiae MutLa is a mismatch repair endonuclease. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37181–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707617200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pillon MC, Lorenowicz JJ, Uckelmann M, Klocko AD, Mitchell RR, Chung YS, Modrich P, Walker GC, Simmons LA, Friedhoff P, Guarne A. Structure of the endonuclease domain of MutL: unlicensed to cut. Mol Cell. 2010;39:145–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guarne A, Junop MS, Yang W. Structure and function of the N-terminal 40 kDa fragment of human PMS2: a monomeric GHL ATPase. Embo J. 2001;20:5521–31. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gueneau E, Dherin C, Legrand P, Tellier-Lebegue C, Gilquin B, Bonnesoeur P, Londino F, Quemener C, Le Du MH, Marquez JA, Moutiez M, Gondry M, Boiteux S, Charbonnier JB. Structure of the MutLa C-terminal domain reveals how Mlh1 contributes to Pms1 endonuclease site. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:461–8. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Obmolova G, Ban C, Hsieh P, Yang W. Crystal structures of mismatch repair protein MutS and its complex with a substrate DNA. Nature. 2000;407:703–10. doi: 10.1038/35037509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Junop MS, Obmolova G, Rausch K, Hsieh P, Yang W. Composite active site of an ABC ATPase: MutS uses ATP to verify mismatch recognition and authorize DNA repair. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malkov VA, Biswas I, Camerini-Otero RD, Hsieh P. Photocross-linking of the NH2-terminal region of Taq MutS protein to the major groove of a heteroduplex DNA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23811–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowers J, Sokolsky T, Quach T, Alani E. A mutation in the MSH6 subunit of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH2-MSH6 complex disrupts mismatch recognition. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16115–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dufner P, Marra G, Raschle M, Jiricny J. Mismatch recognition and DNA-dependent stimulation of the ATPase activity of hMutSb is abolished by a single mutation in the hMSH6 subunit. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36550–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schofield MJ, Brownewell FE, Nayak S, Du C, Kool ET, Hsieh P. The Phe-X-Glu DNA binding motif of MutS. The role of hydrogen bonding in mismatch recognition. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45505–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100449200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorman J, Wang F, Redding S, Plys AJ, Fazio T, Wind S, Alani EE, Greene EC. Single-molecule imaging reveals target-search mechanisms during DNA mismatch repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E3074–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211364109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorman J, Chowdhury A, Surtees JA, Shimada J, Reichman DR, Alani E, Greene EC. Dynamic Basis for One-Dimensional DNA Scanning by the Mismatch Repair Complex Msh2-Msh6. Mol Cell. 2007;28:359–70. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeong C, Cho WK, Song KM, Cook C, Yoon TY, Ban C, Fishel R, Lee JB. MutS switches between two fundamentally distinct clamps during mismatch repair. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:379–85. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho WK, Jeong C, Kim D, Chang M, Song KM, Hanne J, Ban C, Fishel R, Lee JB. ATP alters the diffusion mechanics of MutS on mismatched DNA. Structure. 2012;20:1264–74. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiu R, DeRocco VC, Harris C, Sharma A, Hingorani MM, Erie DA, Weninger KR. Large conformational changes in MutS during DNA scanning, mismatch recognition and repair signalling. EMBO J. 2012;31:2528–40. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Y, Sass LE, Du C, Hsieh P, Erie DA. Determination of protein-DNA binding constants and specificities from statistical analyses of single molecules: MutS-DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:4322–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobs-Palmer E, Hingorani MM. The effects of nucleotides on MutS-DNA binding kinetics clarify the role of MutS ATPase activity in mismatch repair. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:1087–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhai J, Hingorani MM. S. cerevisiae Msh2-Msh6 DNA binding kinetics reveal a mechanism of targeting sites for DNA mismatch repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908302107. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho M, Chung S, Heo SD, Ku J, Ban C. A simple fluorescent method for detecting mismatched DNAs using a MutS-fluorophore conjugate. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;22:1376–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendillo ML, Putnam CD, Mo AO, Jamison JW, Li S, Woods VL, Jr., Kolodner RD. Probing DNA- and ATP-mediated conformational changes in the MutS family of mispair recognition proteins using deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13170–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.108894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antony E, Hingorani MM. Mismatch recognition-coupled stabilization of Msh2-Msh6 in an ATP-bound state at the initiation of DNA repair. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7682–93. doi: 10.1021/bi034602h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antony E, Hingorani MM. Asymmetric ATP binding and hydrolysis activity of the Thermus aquaticus MutS dimer is key to modulation of its interactions with mismatched DNA. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13115–28. doi: 10.1021/bi049010t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bjornson KP, Modrich P. Differential and simultaneous adenosine di- and triphosphate binding by MutS. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18557–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Antony E, Khubchandani S, Chen S, Hingorani MM. Contribution of Msh2 and Msh6 subunits to the asymmetric ATPase and DNA mismatch binding activities of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Msh2-Msh6 mismatch repair protein. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:153–62. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mazur DJ, Mendillo ML, Kolodner RD. Inhibition of Msh6 ATPase activity by mispaired DNA induces a Msh2(ATP)-Msh6(ATP) state capable of hydrolysis-independent movement along DNA. Mol Cell. 2006;22:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monti MC, Cohen SX, Fish A, Winterwerp HH, Barendregt A, Friedhoff P, Perrakis A, Heck AJ, Sixma TK, van den Heuvel RH, Lebbink JH. Native mass spectrometry provides direct evidence for DNA mismatch-induced regulation of asymmetric nucleotide binding in mismatch repair protein MutS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:8052–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gradia S, Acharya S, Fishel R. The human mismatch recognition complex hMSH2-hMSH6 functions as a novel molecular switch. Cell. 1997;91:995–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80490-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gradia S, Subramanian D, Wilson T, Acharya S, Makhov A, Griffith J, Fishel R. hMSH2-hMSH6 forms a hydrolysis-independent sliding clamp on mismatched DNA. Mol Cell. 1999;3:255–61. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang J, Bai L, Surtees JA, Gemici Z, Wang MD, Alani E. Detection of high-affinity and sliding clamp modes for MSH2-MSH6 by single-molecule unzipping force analysis. Mol Cell. 2005;20:771–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winkler I, Marx AD, Lariviere D, Heinze RJ, Cristovao M, Reumer A, Curth U, Sixma TK, Friedhoff P. Chemical trapping of the dynamic MutS-MutL complex formed in DNA mismatch repair in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:17326–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.187641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamers MH, Georgijevic D, Lebbink JH, Winterwerp HH, Agianian B, de Wind N, Sixma TK. ATP increases the affinity between MutS ATPase domains. Implications for ATP hydrolysis and conformational changes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:43879–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406380200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mendillo ML, Hargreaves VV, Jamison JW, Mo AO, Li S, Putnam CD, Woods VL, Kolodner RD. A conserved MutS homolog connector domain interface interacts with MutL homologs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;106:22223–28. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912250106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mukherjee S, Law SM, Feig M. Deciphering the mismatch recognition cycle in MutS and MSH2-MSH6 using normal-mode analysis. Biophys J. 2009;96:1707–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.10.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Selmane T, Schofield MJ, Nayak S, Du C, Hsieh P. Formation of a DNA mismatch repair complex mediated by ATP. J Mol Biol. 2003;334:949–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mendillo ML, Mazur DJ, Kolodner RD. Analysis of the interaction between the Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH2-MSH6 and MLH1-PMS1 complexes with DNA using a reversible DNA end-blocking system. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22245–57. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407545200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson KA. Transient-state kinetic analysis of enzyme reaction pathways. In: David SS, editor. The Enzymes. Vol. 20. Academic Press; 1992. pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cristovao M, Sisamakis E, Hingorani MM, Marx AD, Jung CP, Rothwell PJ, Seidel CA, Friedhoff P. Single-molecule multiparameter fluorescence spectroscopy reveals directional MutS binding to mismatched bases in DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5448–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson KA. Fitting enzyme kinetic data with KinTek Global Kinetic Explorer. Methods Enzymol. 2009;467:601–26. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)67023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sass LE, Lanyi C, Weninger K, Erie DA. Single-molecule FRET TACKLE reveals highly dynamic mismatched DNA-MutS complexes. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3174–90. doi: 10.1021/bi901871u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang H, Yang Y, Schofield MJ, Du C, Fridman Y, Lee SD, Larson ED, Drummond JT, Alani E, Hsieh P, Erie DA. DNA bending and unbending by MutS govern mismatch recognition and specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14822–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2433654100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tessmer I, Yang Y, Zhai J, Du C, Hsieh P, Hingorani MM, Erie DA. Mechanism of MutS Searching for DNA Mismatches and Signaling Repair. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:36646–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805712200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pluciennik A, Modrich P. Protein roadblocks and helix discontinuities are barriers to the initiation of mismatch repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12709–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705129104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghodgaonkar MM, Lazzaro F, Olivera-Pimentel M, Artola-Boran M, Cejka P, Reijns MA, Jackson AP, Plevani P, Muzi-Falconi M, Jiricny J. Ribonucleotides misincorporated into DNA act as strand-discrimination signals in eukaryotic mismatch repair. Mol Cell. 2013;50:323–32. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lujan SA, Williams JS, Clausen AR, Clark AB, Kunkel TA. Ribonucleotides are signals for mismatch repair of leading-strand replication errors. Mol Cell. 2013;50:437–43. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lohman TM, Mascotti DP. Nonspecific ligand-DNA equilibrium binding parameters determined by fluorescence methods. Methods Enzymol. 1992;212:424–58. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)12027-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.