Abstract

Young women with anorexia nervosa (AN) have reduced secretion of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and estrogen contributing to skeletal deficits. In this randomized, placebo-controlled trial, we investigated the effects of oral DHEA+ combined oral contraceptive (COC) vs. placebo on changes in bone geometry in young women with AN. Eighty women with AN, aged 13-27 yr, received a random, double-blinded assignment to micronized DHEA (50 mg/d) + COC (20μg ethinyl estradiol/0.1mg levonorgestrel) or placebo for 18 mo. Measurements of aBMD at the total hip were obtained by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry at 0, 6, 12, and 18 mo. We used the Hip Structural Analysis (HSA) Program to determine BMD, cross-sectional area (CSA), and section modulus at the femoral neck and shaft. Each measurement was expressed as a percentage of the age-, height-, and lean mass-specific mean from an independent sample of healthy adolescent females. Over the 18 months, DHEA+COC led to stabilization in femoral shaft BMD (0.0 ± 0.5 % of normal mean for age, height, and lean mass/year) compared with decreases in the placebo group (−1.1 ± 0.5% per year, p=0.03). Similarly, CSA, section modulus, and cortical thickness improved with treatment. In young women with AN, adrenal and gonadal hormone replacement improved bone health and increased cross sectional geometry. Our results indicate that this combination treatment has a beneficial impact on surrogate measures of bone strength, and not only bone density, in young women with AN.

Keywords: DHEAS, anorexia nervosa, adolescents, bone geometry, estrogen replacement therapy

Introduction

Two clinical features of anorexia nervosa (AN), alterations of the hormonal milieu and loss of body weight, are important risk factors for low BMD [5]. Although weight restoration is known to ameliorate some of the observed skeletal deficits, AN is a chronic disease. Many young women with AN remain malnourished for prolonged periods of time, making additional prevention strategies necessary. There are several hormonal abnormalities in these adolescents, including subnormal serum levels of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), estrogen, and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) that mirror profiles seen in the elderly 1,2. These hormones contribute to the regulation of bone metabolism, and influence the physiologic balance of bone formation and resorption that is important for acquisition and maintenance of peak bone mass. Estrogens are potent inhibitors of bone resorption. DHEA levels positively correlate with BMD, suggesting that DHEA plays an important role in bone accretion and the prevention of bone loss associated with low DHEA states (e.g., AN and aging) 3-5.

Despite the known hypoestrogenic state in these young women, studies testing estrogen/progestin monotherapy have yielded conflicting results6,7, suggesting that other mechanisms also contribute to observed skeletal deficits. We previously demonstrated that DHEA monotherapy led to increases in areal BMD (aBMD) Z-scores in young women with AN, but the effect was primarily explained by the accompanying weight gain 8. Given these preliminary results, we hypothesized that combined therapy with androgen and estrogen/progestin (combined oral contraceptive pill, COC) may be the ideal regimen to normalize altered mechanisms of bone turnover in AN. We recently reported that 18 months of treatment with DHEA+COC improved aBMD in adolescents and young women with AN9.

In addition to standard BMD evaluations by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), our current study also utilized estimates of bone structural geometry obtained from conventional DXA images. The Hip Structural Analysis (HSA) program uses properties of the DXA image to derive geometric measures that are commonly used in engineering evaluations of strength [10]. The resulting structural variables provide clinically relevant indices of bone strength, and have been used to predict stress fractures in military recruits [9], explain gender and ethnicity differences in fracture rates [11], and evaluate skeletal adaptation to weight changes, hormone replacement, and exercise intervention [12, 13]. In a previous cross-sectional analysis, young women with AN had lower resistance to axial and bending loads than healthy young women 10. However, to our knowledge, longitudinal changes in bone geometry have not been examined in adolescents with AN. In the present randomized, placebo-controlled trial, we investigated the effects of an 18-month regimen of oral DHEA+COC vs. placebo on changes in bone geometry in young women with AN. We hypothesized that treatment with DHEA+COC would preserve measurements of DXA-derived bone geometry compared to placebo.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Subjects

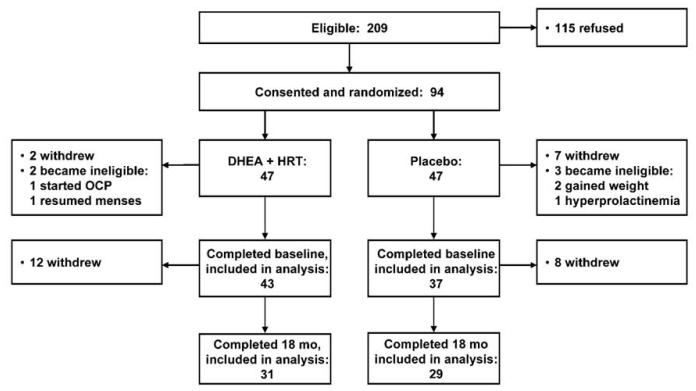

This study was a single-site, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00310791) conducted at Boston Children’s Hospital; full details of the trial have previously been published9. From 2003 to 2008, 615 adolescents presenting to the Eating Disorders Program at Boston Children’s Hospital were screened for study eligibility (Figure 1). Briefly, eligible patients (n=209) were female, aged 15-26 years, Tanner stage 5, and had been diagnosed with AN (amenorrhea, fear of weight gain, and malnutrition). All patients were otherwise healthy and taking no medications known to affect BMD. The local institutional review board approved the study protocol. Informed consent was obtained, with parental consent/subject assent for subjects <18 years.

Figure 1.

Trial Enrollment and Randomization

Ninety-four subjects were enrolled and randomized. One group received 18 months of oral micronized DHEA (50 mg daily; Belmar Pharmacy, Colorado; IND 52,192) plus conjugated equine estrogens (0.3mg daily; Premarin®, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals) for 3 months to minimize estrogen-associated side effects, followed by 15 months of COC (20μg ethinyl estradiol + 0.1mg levonorgestrel; Alesse®, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals). The other group received placebo for the entire 18 months. Both study staff and subjects were blinded to treatment assignment. After randomization, participants returned for assessments at 3, 6, 12, and 18 months.

Outcome Measures

Areal BMD and BMC of the whole body, lumbar spine, and total hip was measured by DXA (QDR 4500, Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA) at 0, 6, 12, and 18 months. Measurements were compared with age- and gender-matched norms11,12. For participants less than age 20 years, pediatric normative data were used 13. With this instrument, the average in vivo precision for aBMD (expressed as percent coefficient of variation) was 0.62% at the spine and 0.72% at the total hip.

Proximal femur scans were analyzed for bone structure and cross-sectional geometry by use of the Hip Structural Analysis (HSA) program developed by Beck et al.14 which is based upon principles first described by Martin and Burr15. The HSA software derives measures of BMD and geometry of narrow cross-sections of bone from traditional DXA images. HSA averages bone dimension and geometry measurements for a series of 5 parallel pixel mass profiles spaces −1mm apart along the bone axis. We report analyses from the narrow neck region (NN, across the femoral neck at its narrowest point) and the proximal femoral shaft region (S, across the shaft 1.5 times minimum neck width, distal to the intersection of the neck and shaft axes).

At the two analysis regions, bone mineral density (BMD, g/cm2), bone cross-sectional area exclusive of soft tissue spaces (CSA, cm2), and cross-sectional moment of inertia (CSMI, cm4) were measured. Section modulus (Z, cm3), a measure of bone bending strength, was calculated as CSMI/dmax, where dmax=the maximum distance from the center of mass to the surface. CSA and section modulus are inversely related to stresses due to axial and bending loads, respectively. Bone outer diameter was measured directly between the margins of the blur-corrected bone mass profile. Cortical thickness (cm) was estimated by modeling cortices of cross-sections as concentric circles. Models assume 100% of the measured mass is in the cortex for the femoral shaft, and 60% for the narrow neck. The relative thickness of the femoral neck cortex was calculated as a buckling ratio. Details of the method, including technique precision, have been previously published16,17. The bone strength index (BSI) is based on the general principle that bending strength of a long bone scales as section modulus over bone length18, and was calculated (section modulus/height) using height as a surrogate for bone length. Resulting values were multiplied by 1000 for convenience.

Normative Data

Bone geometry data from the Penn State Young Women’s Health were utilized as a healthy comparison group to allow for improved clinical interpretation of the HSA measures. The YWHS was a longitudinal study of Caucasian adolescent girls attending school in central Pennsylvania. Details of recruitment methods and subjects have been previously reported19 . Data from subjects aged 15 to 23 years was utilized for comparison. All control subjects were healthy, post-menarchal, and not taking medications known to affect bone health at the time of the visits. Data from a total of 325 control subjects met criteria for use in the data analysis.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline comparisons of continuous measures between the trial arms were made by Student t-test, corroborated by Wilcoxon two-sample tests for variables with skewed distribution. Dichotomies were compared by Fisher exact test.

A formula for the mean value of each bone geometry parameter was obtained by regression analysis of the normative data on age, height, and lean body mass. Measurements from each subject with AN were divided by the appropriate age-, height-, and lean mass-specific mean to obtain a percentage-of-normal value at 0, 6, 12, and 18 months. The normalized data were analyzed by repeated-measures analysis of variance, incorporating a time × treatment interaction and a compound-symmetric covariance structure. Missing values were not imputed, as we found no evidence of differential dropout between arms with respect to any of the bone geometry measures, and the mixed-model analysis is unbiased by random missingness. Linear trends for the treated and placebo group were constructed and compared using contrasts among parameters of the fitted model. All analyses followed the intention-to-treat principle, ascribing the randomly assigned treatment to each subject regardless of compliance. SAS software (version 9.2, Cary, NC) was used for all computations. Findings with P <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients

Of the 94 subjects randomized, fourteen (4 DHEA+COC, 10 placebo) became ineligible or withdrew before completing a baseline measurement (Figure 1), resulting in a final study sample of 80 participants (43 DHEA+COC, 37 placebo), aged 18.1 ± 2.7 yr (mean ± SD), of whom 76 provided usable normalized bone geometry data at baseline (73 at the femoral shaft, all 76 at the narrow neck); 62 at 6 months (both sites); 59 at 12 months (both sites); and 60 at 18 months (both sites). The two arms did not differ by baseline weight or demographic characteristics (Table 1). Subjects were malnourished (mean BMI 18.0 ± 1.5 kg/m2) and had amenorrhea of median duration 11 months (range 1-144 mo). At baseline, 13 subjects had moderate skeletal deficits (aBMD Z-score < −2 SD) at the lumbar spine (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristics by Study Arm

| All (80) | DHEA + COC Arm (43) |

Placebo Arm (37) | P * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | |||||

| Age, yr | 18.1 ± 2.7 | 18.0 ± 2.5 | 18.3 ± 2.8 | 0.84 | |

| Height, cm | 164.0 ± 7.0 | 164.4 ± 6.7 | 163.6 ± 7.5 | 0.47 | |

| Weight, kg | 48.6 ± 5.8 | 49.1 ± 5.9 | 48.0 ± 5.6 | 0.55 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 18.0 ± 1.5 | 18.1 ± 1.5 | 17.8 ± 1.5 | 0.24 | |

| Fat mass, kg | 8.6 ± 2.7 | 8.8 ± 2.8 | 8.4 ± 2.6 | 0.55 | |

| Lean mass, kg | 37.4 ± 4.5 | 37.5 ± 4.2 | 37.2 ± 4.8 | 0.68 | |

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 38.3 ± 14.4 | 39.8 ± 13.4 | 36.7 ± 15.6 | 0.14 | |

| PTH, pg/mL | 29.7 ± 11.2 | 30.1 ± 11.4 | 29.4 ± 11.1 | 0.71 | |

|

| |||||

| Median (Q1–Q3) | |||||

| Duration of AN, mo | 12 (4–28) | 12 (6–40) | 9 (4–18) | 0.07 | |

| Months amenorrhea † | 11 (5–20) | 9 (6–18) | 12 (5–20) | 0.63 | |

|

| |||||

| N (%) | |||||

| White | 71 (89) | 39 (91) | 32 (86) | 0.73 | |

| Hispanic | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 1.0 | |

|

| |||||

| Lumbar spine: ‡ | ≤ –1 SD | 41 (51) | 20 (47) | 21 (57) | 0.38 |

| ≤ –2 SD | 13 (16) | 8 (19) | 5 (14) | 0.76 | |

|

| |||||

| Total hip: | ≤ –1 SD | 19 (24) | 9 (21) | 10 (29) | 0.60 |

| ≤ –2 SD | 3 (4) | 1 (2) | 2 (6) | 0.58 | |

|

| |||||

| Whole body: | ≤ –1 SD | 11 (14) | 4 (9) | 7 (19) | 0.33 |

| ≤ –2 SD | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0.46 | |

Independent-sample t-test, corroborated by non-parametric test, or Fisher Exact test comparing distribution in DHEA+COC and placebo arms.

Excludes five participants with primary amenorrhea; includes six participants who were on COCs at time of recruitment and discontinued use of the medication for at least 1 month before the baseline visit.

aBMD Z-score.

Bone Dimensions and Geometry

At baseline, only the inner and outer diameter at the narrow neck differed between treatment arms (p=0.03; Table 2). When compared to healthy adolescents, subjects with AN demonstrated significant differences in all parameters at the femoral shaft. The femoral shaft of subjects with AN was larger (inner diameter 146 ± 14% of normal for age, height, and lean body mass; p<0.0001) and thus thinner than controls (cortical thickness 51 ± 7% of normal, p<0.0001). The femoral shaft also exhibited a much higher buckling ratio (222 ± 38% of normal, p<0.0001). Interestingly, CSA, section modulus, and BSI were all slightly but significantly higher than in the normal group. At the narrow neck, most bone parameters likewise showed differences from normal that were significant, although less profound. Subjects with AN had lower BSI, BMD, CSA, and section modulus than the control group (p≤0.002 for all), but no differences in cortical thickness or buckling ratio.

Table 2.

Baseline bone cross-sectional geometry, overall and by study arm: mean ± standard deviation relative to mean in normative sample.

| Parameter* | All | p † | DHEA + COC Arm |

Placebo Arm | p ‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Femoral Shaft

| |||||

| n | 73 | 40 | 33 | ||

| Bone mineral density | 95 ± 11 | 0.0001 | 96 ± 9 | 94 ± 13 | 0.58 |

| Cross-sectional area | 104 ± 13 | 0.005 | 106 ± 11 | 103 ± 15 | 0.26 |

| Cortical thickness | 51 ± 7 | <0.0001 | 51 ± 6 | 50 ± 7 | 0.65 |

| Inner diameter | 146 ± 14 | <0.0001 | 147 ± 14 | 144 ± 14 | 0.44 |

| Outer diameter | 110 ± 7 | <0.0001 | 111 ± 7 | 109 ± 7 | 0.25 |

| Buckling ratio | 222 ± 38 | <0.0001 | 221 ± 33 | 223 ± 44 | 0.84 |

| Section modulus | 114 ± 17 | <0.0001 | 116 ± 16 | 110 ± 17 | 0.10 |

| Bone strength index § | 114 ± 17 | <0.0001 | 117 ± 16 | 110 ± 17 | 0.10 |

|

| |||||

|

Femoral Narrow Neck

| |||||

| n | 76 | 42 | 34 | ||

| Bone mineral density | 92 ± 12 | <0.0001 | 92 ± 12 | 93 ± 12 | 0.71 |

| Cross-sectional area | 95 ± 14 | 0.002 | 96 ± 14 | 93 ± 13 | 0.41 |

| Cortical thickness | 102 ± 17 | 0.25 | 102 ± 17 | 102 ± 16 | 0.92 |

| Inner diameter | 104 ± 9 | 0.0002 | 106 ± 8 | 102 ± 10 | 0.030 |

| Outer diameter | 102 ± 7 | 0.005 | 104 ± 7 | 100 ± 8 | 0.030 |

| Buckling ratio | 103 ± 20 | 0.17 | 106 ± 21 | 100 ± 18 | 0.21 |

| Section modulus | 90 ± 17 | <0.0001 | 91 ± 18 | 88 ± 16 | 0.41 |

| Bone strength index § | 90 ± 17 | <0.0001 | 92 ± 18 | 88 ± 16 | 0.41 |

Bone strength parameters are expressed as percentage of normal mean for age, height, and lean body mass, determined from an independent sample. Baseline DXA not available for 1 DHEA+COC subject and 2 placebo subjects.

Comparing mean to 100% of normal, by one-sample t-test.

Comparing mean between treatment groups, by independent-sample t-test.

1000 × section modulus ÷ height.

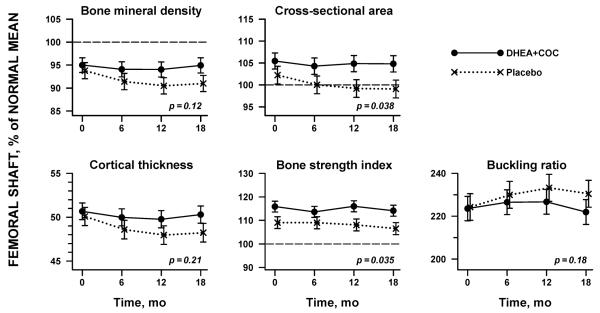

Over the 18 months of the trial, femoral shaft BMD did not change in the DHEA+COC group relative to the normal group (−0.0 ± 0.5 % of normal mean for age, height, and lean mass per year, mean ± standard error, p=0.94) while simultaneously dropping in the placebo group (−1.1 ± 0.5% per year, p=0.03; time x treatment p-value=0.12) (Table 3, Figure 2). Subjects receiving placebo treatment developed thinner bone (cortical thickness −0.7 ± 0.3% per year, p=0.02); the subjects receiving DHEA+COC did not demonstrate changes at these sites during the 18 months of treatment (Table 3, Figure 2). These longitudinal changes in bone geometry estimates led to declines in bone bending strength, estimated by both the sectional modulus and the bone strength index, in the placebo group and a significant difference from the subjects receiving DHEA+COC by 18 months (DHEA+COC 1.1 ± 0.7%/yr versus placebo −1.1 ± 0.7%/yr, p=0.04 for both).

Table 3.

Rate of change in bone strength parameters over 18-mo trial, comparing DHEA+COC treatment with placebo for the 60 young women who completed the study

| Parameter* | DHEA+COC | Placebo | Interaction p |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Change/yr ± SE† |

p | Change/yr ± SE |

p | ||

| Femoral shaft | |||||

| Bone mineral density | −0.0 ± 0.5 | 0.94 | −1.1 ± 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| Cross-sectional area | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.63 | −1.1 ± 0.5 | 0.02 | 0.038 |

| Cortical thickness | −0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.50 | −0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.02 | 0.21 |

| Inner diameter | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.053 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.27 | 0.61 |

| Outer diameter | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.54 | 0.0 ± 0.3 | 0.94 | 0.72 |

| Buckling ratio | −0.2 ± 1.7 | 0.90 | 3.2 ± 1.9 | 0.09 | 0.18 |

| Section modulus | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 0.13 | −1.1 ± 0.7 | 0.15 | 0.037 |

| Bone strength index ‡ | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 0.12 | −1.1 ± 0.7 | 0.15 | 0.035 |

|

| |||||

| Femoral narrow neck | |||||

| Bone mineral density | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 0.054 | −0.3 ± 0.6 | 0.59 | 0.09 |

| Cross-sectional area | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.57 | −0.0 ± 0.5 | 0.93 | 0.65 |

| Cortical thickness | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 0.040 | −0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.64 | 0.08 |

| Inner diameter | −0.7 ± 0.4 | 0.07 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.59 | 0.10 |

| Outer diameter | −0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.08 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.62 | 0.12 |

| Buckling ratio | −1.4 ± 1.0 | 0.14 | 0.3 ± 1.0 | 0.77 | 0.22 |

| Section modulus | 0.4 ± 0.6 | 0.48 | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 0.42 | 0.92 |

| Bone strength index ‡ | 0.4 ± 0.6 | 0.48 | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 0.44 | 0.94 |

Bone strength parameters are expressed as percentage of normal mean for age, height, and lean body mass, determined from an independent sample. SE: standard error of estimated rate of change per year.

SE: standard error of estimated rate of change per year, from repeated-measures regression analysis of bone strength parameter vs. time. p tests hypothesis of zero rate of change within treatment group. Interaction p tests for equal rate of change in the two treatment groups.

1000 × section modulus ÷ height.

Figure 2.

Changes in bone geometry at the femoral shaft in adolescents with anorexia nervosa over 18 months of therapy with either DHEA + COC (solid line) or placebo (dashed line), Bone geometry measures are presented as the percentage of normal mean, controlling for age, height, and lean body mass. P-values are from repeated-measures analysis of variance, incorporating a time × treatment interaction.

The axial strength of bone, estimated by CSA, also changed in different ways between treatment arms over the study. Subjects receiving DHEA+COC maintained CSA at the femoral shaft , while girls receiving placebo therapy lost −1.1 ± 0.5%/year (p=0.02; Figure 2). Adjustment of our results for the weight gain equally experienced by both treatment arms over the course of the trial (DHEA+COC: 5.9 ± 1.0 kg/yr vs. placebo: 5.2 ± 1.1 kg/yr; p=0.52) did not impact bone geometry findings.

Treatment effects were less profound at the femoral narrow neck (Table 3). While BMD and cortical thickness increased in the subjects receiving DHEA+COC and further declined in subjects receiving placebo, the overall difference between groups did not reach significance (Table 3). No difference in axial or bending strength at the femoral narrow neck was noted between groups. Controlling for weight gain or change in lean body mass during the trial did not impact these results.

Discussion

Compared to placebo, replacement of both adrenal and gonadal hormones led to significant improvements in bone health in young women with AN over 18 months of treatment. As compared to placebo, improvements in hip structural geometry estimates after treatment were seen in axial strength (CSA), bending strength (section modulus), and bone strength index measured at the femoral shaft. At the femoral neck, results were less robust. As the femoral shaft represents a much more common site for stress fracture in adolescents, our findings may have direct clinical relevance.

Patients with AN have an abnormal hormonal milieu, including deficits of androgens and estrogens. Both decreased skeletal loading (from malnutrition and loss of muscle mass) and the hormonal aberrations experienced by patients with AN lead to increased inner diameters of bone, increased outer diameters, and diminished cortical thickness10. These structural changes lead to larger, but thinner bones in girls with AN. The increased outer diameters are of particular interest in that it has been postulated with some evidence that estrogen tends to inhibit subperiosteal bone growth20. Previous investigations of single hormonal replacement for skeletal health preservation in these patients have yielded conflicting results 6,8,21,22. The current regimen, combining both estrogen/progestin and DHEA, built upon more than 20 years of previous research, and was designed to promote skeletal health in multiple ways. Combination hormonal therapy has been studied in other populations with a similar hormonal profile to teens with AN. Androgen and estrogen administered to postmenopausal women led to anabolic effects on bone formation markers and accompanied increases in BMD 23,24 Given the potentially synergistic mechanisms of action, treatment using combined DHEA + COC, which normalizes levels of endogenous hormones that should be present in abundance during adolescence, may be the optimal therapy to achieve the critical bone acquisition that should occur during adolescence and young adulthood. In our current study, hormone replacement increased cortical thickness, and led to an associated decrease in the buckling ratio. Elevated buckling ratios are indicative of increased fracture risk in adults25. We have demonstrated that femoral shaft dimensions are greater in subjects with AN compared to healthy young women10; in this trial, DHEA+COC appears to reduce these differences.

While DXA is the current clinical standard for evaluating bone mass in children and adolescents, traditional DXA outcomes do not adequately describe the strength of bone. Bone strength depends on both the material and structural (geometric) properties of bone [8]. While material strength cannot yet be measured in vivo by non-invasive means, measures of geometry may reveal strength deficits not readily evident in conventional BMD or BMC [9]. Previous work supports an association between sex steroid levels and these structural variables. Biopsy data have suggested that periosteal apposition (the deposit of new bone onto the outer surface) is suppressed by estrogen 26. Thus, estrogen supplementation (via the ethinyl estradiol administered to the treatment group) or estrogen derived from its precursor DHEA, may explain mechanistically the positive BMD changes observed in the DHEA + COC group. Our results demonstrate that unlike placebo, combined DHEA+COC led to improvements in bone geometry at a weight-bearing site, even after controlling for weight gain.

Given the chronicity of AN, many patients who suffer from the disease will remain malnourished for a prolonged length of time. Although weight gain leads to improvements in skeletal health, weight restoration is difficult to achieve in this population. We demonstrated that DHEA+COC therapy led to improvements in skeletal health even after accounting for weight gain. In this cohort actively involved in a research study, subjects in both groups gained weight over the 18 month study. Neither weight gain or change in lean mass differed between placebo and treatment group9. Despite these findings, axial and torsional bone strength (CSA, sectional modulus, BSI) increased in subjects receiving DHEA+COC, while simultaneously decreasing in subjects receiving placebo. Thus, our combination hormonal therapy represents an important and effective temporary measure to prevent bone loss and even improve skeletal health in these chronically ill young women, while patients move towards weight gain and psychological recovery.

Study limitations, related both to the study population and analyses, should be acknowledged. Our sample was limited to young women with skeletal maturity; these results may not be generalizable to growing adolescents with open epiphyses. The HSA program provides a method to assess bone structural parameters utilizing DXA technology. However, DXA scans are not optimized for measurements of bone geometry. There are inherent limitations in attempts to assess three-dimensional structure from two-dimensional images. Two-dimensional DXA structural geometrical variables dependent on mass calibration standards and mathematical derivation techniques are different from three-dimensional QCT variables27,28. However, correlations between measured variables between DXA and QCT range from moderate to high (0.73 to 0.90), substantiating the assumptions underlying the HSA approach and increasing confidence that 2D HSA replicates the 3D measures27,28. Precision of the HSA analyses was not measured for the current study. Because a cross calibration was not available for ensuring that geometry values were consistent with the normative reference data, the Boston parameters were linearly adjusted to ensure that there was a consistent relationship between HSA narrow-neck BMD and the conventional femoral neck BMD across the two studies. This geometry adjustment takes advantage of the consistency calibration by the manufacturer for the two model scanners. The HSA program assumes that tissue mineralization is not different from that of average adults. In reality, it may be reduced in growing adolescent skeletons, leading to small underestimates of cross-sectional geometry. Assumptions regarding proportions of cortical vs. trabecular bone that are used to estimate cortical thickness and buckling ratio may also not be as applicable to adolescents. Material strength, or factors that influence it such as tissue mineralization, determine stress resistance, but cannot be reliably evaluated using DXA or any other current non-invasive method. Despite these limitations, these sources of error should not be limited to one subject group or the other, and in fact, may be more likely to bias our results negatively.

In conclusion, a combination regimen of oral DHEA + COC for 18 months led to increases in estimates of bone cross-sectional geometry compared to placebo therapy in young women with AN. Positive results of treatment were seen at the femoral shaft, even after accounting for weight gain. Findings were less profound at the femoral narrow neck. Our results indicate that this new use of combination therapy has a beneficial impact on bone strength, and not only bone density, in young women with AN.

Acknowledgements

Study funding received from the Clinical and Translational Study Unit of Children’s Hospital Boston, NIH grants R01 HD043869, K23 HD060066, R01 AR060829, and funding from the Department of Defense, US Army Bone Health and Military Readiness Program. We thank our colleagues involved with the Young Women’s Health Study at Penn State Medical Center for their collaboration, as well as Belmar Pharmacy, Colorado, who supplied the DHEA supplement utilized in this study. We also wish to acknowledge the assistance of Jamie Nydegger, Yailka Cardenas, Caitlin Stone, Julie Ringelheim, Kristen van der Veen, Julia Brown, Courtney Giancaterino, Nicolle Quinn, and Diane DiFabio; the excellent nursing staff of the Boston Children’s Hospital Clinical and Translational Study Unit; and our patients and their families, who made this research possible.

Funding Sources: Clinical and Translational Study Unit of Children’s Hospital Boston, NIH grants R01 HD043869, K23 HD060066, and R01 AR060829, and Department of Defense, US Army Bone Health and Military Readiness Program.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00310791

Conflict of Interest Page Dr. Gordon was a co-director of the MIT/Harvard Clinical Investigation Training Program, sponsored in part by Pfizer and Merck. Dr. Beck is founder of Beck Radiological Innovations, Inc. All other authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Meikle AW, Daynes RA, Araneo BA. Adrenal androgen secretion and biologic effects. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 1991 Jun;20(2):381–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orentreich N, Brind JL, Rizer RL, Vogelman JH. Age changes and sex differences in serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate concentrations throughout adulthood. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1984 Sep;59(3):551–555. doi: 10.1210/jcem-59-3-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taelman P, Kaufman JM, Janssens X, Vermeulen A. Persistence of increased bone resorption and possible role of dehydroepiandrosterone as a bone metabolism determinant in osteoporotic women in late post-menopause. Maturitas. 1989 Mar;11(1):65–73. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(89)90121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haden ST, Glowacki J, Hurwitz S, Rosen C, LeBoff MS. Effects of age on serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, IGF-I, and IL-6 levels in women. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2000 Jun;66(6):414–418. doi: 10.1007/s002230010084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinberg KK, Freni-Titulaer LW, DePuey EG, et al. Sex steroids and bone density in premenopausal and perimenopausal women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1989 Sep;69(3):533–539. doi: 10.1210/jcem-69-3-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klibanski A, Biller BM, Schoenfeld DA, Herzog DB, Saxe VC. The effects of estrogen administration on trabecular bone loss in young women with anorexia nervosa. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995 Mar;80(3):898–904. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.3.7883849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seeman E, Szmukler GI, Formica C, Tsalamandris C, Mestrovic R. Osteoporosis in anorexia nervosa: the influence of peak bone density, bone loss, oral contraceptive use, and exercise. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1992 Dec;7(12):1467–1474. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650071215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon CM, Grace E, Emans SJ, et al. Effects of oral dehydroepiandrosterone on bone density in young women with anorexia nervosa: a randomized trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002 Nov;87(11):4935–4941. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Divasta AD, Feldman HA, Giancaterino C, Rosen CJ, Leboff MS, Gordon CM. The effect of gonadal and adrenal steroid therapy on skeletal health in adolescents and young women with anorexia nervosa. Metabolism. 2012 Jul;61(7):1010–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Divasta AD, Beck TJ, Petit MA, Feldman HA, Leboff MS, Gordon CM. Bone cross-sectional geometry in adolescents and young women with anorexia nervosa: a hip structural analysis study. Osteoporos. Int. 2007 Jan 5; doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0308-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly TL. Bone mineral density reference databases for American men and women. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1990;5:S249. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, et al. Proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos. Int. 1995;5(5):389–409. doi: 10.1007/BF01622262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zemel BS, Leonard MB, Kalkwarf HJ, et al. Reference data for the whole body, lumbar spine, and proximal femur for American children relative to age, gender, and body size. J Bone Miner Res 1. 2004:S231. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beck TJ, Ruff CB, Warden KE, Scott WW, Jr., Rao GU. Predicting femoral neck strength from bone mineral data. A structural approach. Invest. Radiol. 1990 Jan;25(1):6–18. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199001000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin RB, Burr DB. Non-invasive measurement of long bone cross-sectional moment of inertia by photon absorptiometry. J. Biomech. 1984;17(3):195–201. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(84)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck TJ, Looker AC, Ruff CB, Sievanen H, Wahner HW. Structural trends in the aging femoral neck and proximal shaft: analysis of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry data. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2000 Dec;15(12):2297–2304. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.12.2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khoo BC, Beck TJ, Qiao QH, et al. In vivo short-term precision of hip structure analysis variables in comparison with bone mineral density using paired dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans from multi-center clinical trials. Bone. 2005 Jul;37(1):112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selker F, Carter DR. Scaling of long bone fracture strength with animal mass. J. Biomech. 1989;22(11-12):1175–1183. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(89)90219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lloyd T, Petit MA, Lin HM, Beck TJ. Lifestyle factors and the development of bone mass and bone strength in young women. J. Pediatr. 2004 Jun;144(6):776–782. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leppanen OV, Sievanen H, Jokihaara J, et al. The effects of loading and estrogen on rat bone growth. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010 Jun;108(6):1737–1744. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00989.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golden NH, Lanzkowsky L, Schebendach J, Palestro CJ, Jacobson MS, Shenker IR. The effect of estrogen-progestin treatment on bone mineral density in anorexia nervosa. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2002 Jun;15(3):135–143. doi: 10.1016/s1083-3188(02)00145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu SL, Lebrun CM. Effect of oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy on bone mineral density in premenopausal and perimenopausal women: a systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2006 Jan;40(1):11–24. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.020065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raisz LG, Wiita B, Artis A, et al. Comparison of the effects of estrogen alone and estrogen plus androgen on biochemical markers of bone formation and resorption in postmenopausal women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1996 Jan;81(1):37–43. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.1.8550780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Labrie F, Diamond P, Cusan L, Gomez JL, Belanger A, Candas B. Effect of 12-month dehydroepiandrosterone replacement therapy on bone, vagina, and endometrium in postmenopausal women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997 Oct;82(10):3498–3505. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.10.4306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melton LJ, 3rd, Beck TJ, Amin S, et al. Contributions of bone density and structure to fracture risk assessment in men and women. Osteoporos. Int. 2005 May;16(5):460–467. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1820-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seeman E. Estrogen, androgen, and the pathogenesis of bone fragility in women and men. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2004 Sep;2(3):90–96. doi: 10.1007/s11914-004-0016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khoo BC, Brown K, Zhu K, et al. Differences in structural geometrical outcomes at the neck of the proximal femur using two-dimensional DXA-derived projection (APEX) and three-dimensional QCT-derived (BIT QCT) techniques. Osteoporos. Int. 2012 Apr;23(4):1393–1398. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1727-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khoo BC, Wilson SG, Worth GK, et al. A comparative study between corresponding structural geometric variables using 2 commonly implemented hip structural analysis algorithms applied to dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry images. J Clin Densitom. 2009 Oct-Dec;12(4):461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]