Abstract

Recent research has demonstrated some growth recovery among children stunted in infancy. Less is known about key age ranges for such growth recovery, and what factors are correlates with this growth. This study characterized child growth up to age 1 year, and from ages 1 to 5 and 5 to 8 years controlling for initial height-for-age z-score (HAZ), and identified key distal household and community factors associated with these growth measures using longitudinal data on 7,266 children in the Young Lives (YL) study in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam. HAZ at about age 1 year and age in months predicted much of the variation in HAZ at age 5 years, but 40 to 71% was not predicted. Similarly, HAZ at age 5 years and age in months did not predict 26 to 47% of variation in HAZ at 8 years. Multiple regression analysis suggests that parental schooling, consumption, and mothers’ height are key correlates of HAZ at about age 1 and also are associated with unpredicted change in HAZ from ages 1 to 5 and 5 to 8 years, given initial HAZ. These results underline the importance of a child’s starting point in infancy in determining his or her growth, point to key distal household and community factors that may determine early growth in early life and subsequent growth recovery and growth failure, and indicate that these factors vary some by country, urban/rural designation, and child sex.

Keywords: Child growth, child growth recovery, child growth faltering, household and community factors, Ethiopia, India, Peru, Vietnam

Introduction

Chronic undernutrition is a major global health challenge, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). According to de Onis et al. (2011), about 171 million children under age 5 years (167 million in LMICs) are stunted (i.e., at least two standard deviations below the median in height-for-age z-score, HAZ). Undernutrition contributes to more than one-third of the 7.7 million deaths annually among children under age 5 years, mostly in the developing world (Black et al. 2008, Rajaratnam et al. 2010). Undernutrition, poverty and inadequate parental stimulation prevent more than 200 million children under age 5 years from reaching their developmental potential (Grantham-McGregor et al. 2007). Extensive research demonstrates the importance of nutrition in the first 2-3 years of life for child survival, health, motor development, cognitive and socioemotional performance, school participation, adult wage rates and next-generation child anthropometrics (Behrman et al. 2009, Black et al. 2003, Caulfield et al. 2006, Crookston et al. 2011, Daniels and Adair 2004, Hoddinott et al. 2008, Maluccio et al. 2009,Victora et al. 2008).

Some have suggested that in developing country contexts, growth failure is essentially irreversible after about 2 years of age (Checkley et al. 2003, de Onis 2003, Walker et al. 1996). However, growth recovery from early childhood stunting may be possible. Significant proportions of children in some low-income contexts experienced increases in HAZ between ages 1 and 5 years (Crookston et al. 2010, Crookston et al. 2011, Lundeen et al. Submitted ). Less is known, however, as to what factors are associated with these reversals.

We developed evidence on the correlates of early child growth up to age 1, and deviations from expected growth from ages 1 to 5 and 5 to 8 years. We explored key distal factors at the household and community levels that were correlated with increases in HAZ from age 1 to 5 and from age 5 to 8 using Young Lives longitudinal data for Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam, and also examined whether there are systematic differences in these relations by country, urban-rural location and child sex. While a few cohort studies have examined the association of distal factors with changes in child growth (table 1), this is the first multi-country cohort study of which we are aware that has identified factors associated with change in height over time not predicted by initial height, thus identifying potential additional opportunities for improving child growth in resource-poor settings beyond those represented by correlates with HAZ at age 1 year.

Table 1.

Review of cohort studies examining distal factors associated with change in child height

| Author(s) | Age Range | Country [N=] | Estimation Method & Dependent Variable |

Independent Variables [Estimates] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outes et al. 2012 | 1 to 5 y | Ethiopia [1,999] | Community fixed-effects linear estimates of HAZ at age 5 lagged on HAZ at age 1 |

Wealth index quartile 4 × HAZ age 1 [−0.101 (−0.197, −0.004)] |

| Godoy et al. 2009 | 2 to 7 y | Bolivia [673] | Random-effects panel linear regression model for growth rate in height |

Number of younger siblings [−0.531 (−0.978, −0.084)*] Current income [−0.016 (−0.029, −0.003)*] |

| Crookston et al. 2010 | 1 to 5 y | Peru [374] | Logistic regression model for catch-up growth among children stunted in infancy |

Maternal height cm [OR: 1.66 (1.28, 2.17)] Maternal education y [OR: 1.06 (1.00, 1.13)] |

| Lourenco et al. 2012 | 0.5 to 10 y | Brazil [256] | Cubic spline mixed-effects models were used to estimate average HAZ |

Land ownership [0.34 (0.05, 0.63)] |

| Adair 1999 | 2 to 8.5 y | Philippines [2,011] | Logistic regression model for higher than expected linear growth rates |

Tall mother > 154.75 cm [OR: 1.55 (1.14, 2.11)] Short mother < 145 cm [OR: 0.39 (0.23, 0.66)] High assets, increase [OR: 3.07 (1.91, 4.97)] Number of younger siblings [OR: 0.89 (0.79, 0.99)] |

| Sedgh et al. 2000 | 0.5 to 7.5 y | Sudan [8,174] | Linear regression model predicting stunting reversal |

Maternal literacy=no [RR: 0.73 (0.63, 0.84)] Water in house=no [RR: 0.80 (0.69, 0.92)] |

| Coly et al. 2006 | 1 to 23 y | Senegal [2,874] | Linear regression model for height increment |

Four groupings of increasing duration of migration to urban settings [height increment in cm among girls: 67.2, 69.3, 67.4, 67.7; p<0.01] |

| Eckhardt et al. 2005 | 2 to 18.5 y | Philippines [2,029] | ANOVA (Group 1. decreased HAZ, Group 2. same HAZ, and Group 3. increased HAZ) |

BOYS: Maternal education y [Group 1,3: 7.7 (7.3, 8.1), 6.3 (5.9, 6.7)] GIRLS: Maternal education y [Group 1,3: 7.5 (7.1, 7.9), 6.1 (5.8, 6.4)] Maternal height cm [Group 1,3: 149.4 (148.9, 150.0), 150.9 (150.3, 151,5)] |

Confidence intervals estimated based on cut-off p-value reported

Data

We analyzed data on 7,266 children in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam collected at ages about 1, 5, and 8 years in YL, a cross-national cohort study on poverty and child well-being in the developing world. We studied the younger cohort, enrolled in 2002 at ages 6-17.9 months (round 1). Sampling details are at http://www.younglives.org.uk; comparisons with representative data suggested that the samples represented a variety of contexts in each of the countries studied, though not of the highest part of the income distributions. Subsequent data collection occurred in 2006 when the younger cohort was about 5 years old (round 2) and in 2009 when these children were about 8 years old (round 3). We used all observations for which HAZ values were available for all three rounds (from 91.6% [Ethiopia] to 95.9% [Vietnam] of total observations), and excluded children who were not between the target ages of 6 to 17.9 months at the time of first HAZ measurement (from 0.0% [Ethiopia] to 3.5% [Vietnam] of total observations), or for whom absolute changes between two rounds were greater than four standard deviations (0.1% [Vietnam] to 3.9% [Ethiopia] of total observations). We retained 87.9% of the initial observations for Ethiopia, 90.8% for India, 90.0% for Peru and 94.4% for Vietnam. Excluded observations had higher values for caregivers’ and fathers’ schooling, lower values of mothers’ height and consumption levels (except Ethiopia for consumption), were more likely to have moved, and had a longer time between measures (etable 1).

Growth Variables

HAZ at each round was based on the World Health Organization (WHO) 2006 standard for children under 5 years and the WHO 2007 standard for school-aged children (WHO 2006, deOnis et al. 2007). We computed the change in HAZ from ages 1 to 5 and 5 to 8 years. As children in the YL data were first interviewed between 6 and 17.9 months, a period in which there is widespread growth faltering in many LMICs (Victora et al. 2010), we controlled for the age at measurement in all analyses.

Household and Community Variables

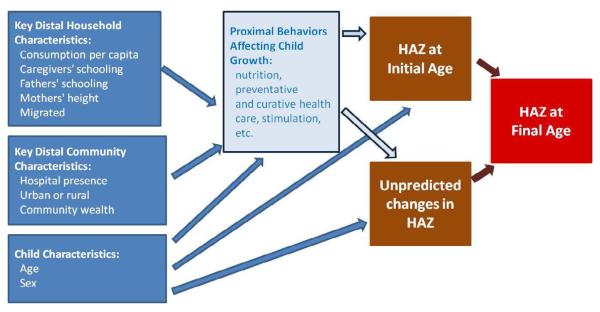

We studied key distal household and community variables that plausibly affect child growth (summarized in figure 1).

Figure 1.

Key Distal Household and Community Characteristics and HAZ at Initial Age, Unpredicted Changes in HAZ, and HAZ at Final Age

Household variables: (1) Poverty is associated with poorer growth outcomes (Black et al. 2008, Grantham-McGregor 2007); we computed country-specific household consumption per capita quintiles, separately by country (thus we are capturing relative differences in consumption within countries rather than absolute differences across countries; etable 2 shows results using purchasing power parity (PPP)-adjusted consumption per capita to allow for comparisons across countries in absolute consumption levels.). We used consumption as it is a relatively stable measure of household resources. Household consumption per capita was calculated using adult respondents’ estimation of food and non-food items with a recall period ranging from 15 days for food to 12 months for clothing. The total expenditures were converted to real monthly expenditures and divided by household size. Consumption data were collected when children were 5 and 8, so we used household consumption quintiles at the earliest point in time available for each outcome. (2) Maternal formal schooling is associated with child growth (Semba et al. 2008). We used continuous measures of caregivers’ schooling; caregivers were the individuals who spent the most time caring for children, and were usually mothers (98.4% for round 1). (3) Fathers’ schooling also is associated with child growth (Semba et al. 2008) so we included a continuous measure of fathers’ schooling. (4) Mothers’ height is inversely associated with stunting and may be an important predictor of potential growth due to genetic and other endowments (Bosch et al. 2008, Ozaltin et al. 2010, Subramanian et al. 2009). (5) As there may be growth differences by sex (Bosch et al. 2008), we included a variable for whether children were female. Finally, children were not measured at exactly 1, 5, and 8 years. We included the number of months between the beginning and the end of the growth period to control for the period of risk exposure.

Distal Community variables: (1) Access to health services may impact child growth (Fay et al. 2005), so we included a dummy variable for whether communities in which children lived had hospitals. (2) Whether the community is urban or rural may affect child nutrition (Garrett and Ruel 1999); we included a dummy for urban residence. (3) Community wealth may affect child growth through the provision of community services and the quality of community environments. We constructed an asset-based index separately by country as the first principal component of 19 indicators of household durables, housing quality, and available services (e.g., safe water sources and electricity) (Filmer and Scott 2012, etable 3). We included community wealth, which is the average asset index for all households (other than the child’s household) in the community. The distal community variables were complete for round 1, but due to migration, there were some missing values in rounds 2 and 3. We used community variables in round 1 and included a variable indicating whether children moved to different communities after round 1.

Methods

Our objectives were to (1) analyze associations of HAZ at age 1 year (HAZ(1)) with selected distal household and community factors, (2) characterize changes in HAZ from age 1 to 5 and 5 to 8 years that were not predicted by the starting values of HAZ (designated ucHAZ(1:5) and ucHAZ(5:8), where “ucHAZ” refers to “unpredicted change in HAZ”), and (3) estimate associations between unpredicted changes in HAZ (ucHAZ) and key distal family and community characteristics. The dependent variable for (3) was that component of HAZ at the end of the age period that was not predicted by the HAZ value at the start of the period (Stein et al, 2010). This method is an improvement upon examining the HAZ value at the end of the period while controlling for the value at the beginning of the period on the right side, because it isolates the portion of change over time that would not be predicted given the initial HAZ measure.

We used ordinary least squares (OLS) multivariate regressions to compute ucHAZ(1:5) and ucHAZ(5:8), and to investigate associations between the dependent variables and key household and community characteristics.

To obtain ucHAZ(1:5), we conducted OLS separately for each country for:

| (1) |

We included dummies for three separate age categories (relative to a reference category of ages 12-14 months) at which HAZ(1) measurements were taken, plus interactions between these categories and the HAZ(1) measurement. The interactions adjust for the tendency of HAZ to decrease with age over the age range at which study participants were recruited. We then generated ucHAZ(1:5) as the difference between the actual and predicted values of HAZ(5) (i.e., the residual). An analogous procedure was used to construct ucHAZ(5:8).

We next estimated associations between HAZ(1), ucHAZ(1:5), and ucHAZ(5:8) as dependent variables, with key distal household (H) and community (C) factors and controls as explanatory variables, plus a stochastic disturbance term (ν):

| (3) |

H is the vector of key distal household characteristics, and C is the vector of key distal community characteristics. We estimated equation (3) separately by country with robust standard errors allowing for clustering at the community level.

Several household and community variables had missing values for some individuals (see sample sizes in table 2). We employed multiple imputation methods with 25 replications using the ice command in Stata 12.1. For robustness analysis, we estimated the same models, but with interactions between each of the right-side variables and (1) female, (2) urban residence, (3) country and (4) indicators for excluded observations, in order to examine differences that may exist by sex, urban-rural residence, or country, as well as the implications of our data exclusion criteria.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics

| Full Sample | Ethiopia | India | Peru | Vietnam | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | S.D. | n | Mean | S.D. | N | Mean | S.D. | n | Mean | S.D. | N | Mean | S.D. | |

| HAZ Variables | |||||||||||||||

| HAZ(1) | 7,266 | −1.41 | 1.39 | 1,757 | −1.83 | 1.65 | 1,825 | −1.35 | 1.42 | 1,847 | −1.33 | 1.22 | 1,837 | −1.14 | 1.15 |

| HAZ(5) | 7,266 | −1.50 | 1.06 | 1,757 | −1.48 | 1.09 | 1,825 | −1.65 | 0.98 | 1,847 | −1.53 | 1.11 | 1,837 | −1.34 | 1.03 |

| HAZ(8) | 7,266 | −1.23 | 1.05 | 1,757 | −1.23 | 1.05 | 1,825 | −1.45 | 1.01 | 1,847 | −1.15 | 1.05 | 1,837 | −1.10 | 1.04 |

| Change in HAZ ages 1 to 5 y | 7,266 | 0.17 | 1.16 | 1,757 | 0.60 | 1.44 | 1,825 | −0.11 | 1.22 | 1,847 | 0.18 | 0.89 | 1,837 | 0.038 | 0.90 |

| Change in HAZ ages 5 to 8 y | 7,266 | 0.88 | 0.78 | 1,757 | 1.24 | 0.93 | 1,825 | 0.93 | 0.80 | 1,847 | 0.69 | 0.58 | 1,837 | 0.67 | 0.60 |

| ucHAZ(1:5) | 7,266 | 0.00 | 0.79 | 1,757 | 0.00 | 0.92 | 1,825 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 1,847 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 1,837 | 0.00 | 0.65 |

| ucHAZ(5:8) | 7,266 | 0.00 | 0.61 | 1,757 | 0.00 | 0.72 | 1,825 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 1,847 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 1,837 | 0.00 | 0.53 |

| Household characteristics | |||||||||||||||

| Consumption(R2) | 7,098 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 1,756 | 0.00 | 1.01 | 1,662 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1,846 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 1,834 | 0.00 | 1.02 |

| Consumption(R3) | 7,189 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 1,756 | 0.00 | 1.02 | 1,751 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 1,845 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 1,837 | 0.00 | 1.01 |

| Caregiver highest grade completed |

7,252 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 1,744 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 1,825 | 3.3 | 4.4 | 1,846 | 7.8 | 4.4 | 1,837 | 6.5 | 3.5 |

| Fathers’ highest grade completed |

7,083 | 6.8 | 4.6 | 1,683 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 1,822 | 5.6 | 5.0 | 1,789 | 9.1 | 3.9 | 1,789 | 7.7 | 4.0 |

| Mothers’ height (cm) | 6,987 | 152.9 | 7.6 | 1,615 | 158.4 | 9.0 | 1,793 | 151.5 | 6.5 | 1,761 | 149.9 | 5.9 | 1,818 | 152.2 | 5.9 |

| Child is female (%) | 7,266 | 47.9 | 1,757 | 46.6 | 1,825 | 46.3 | 1,847 | 49.8 | 1,837 | 48.8 | |||||

| Time between measurement, R1 to R2 |

7,266 | 51.5 | 2.3 | 1,757 | 50.2 | 1.3 | 1,825 | 52.5 | 1.8 | 1,847 | 52.0 | 3.2 | 1,837 | 51.3 | 1.7 |

| Time between measurement, R2 to R3 |

7,266 | 32.8 | 2.6 | 1,757 | 35.1 | 1.3 | 1,825 | 31.2 | 1.5 | 1,847 | 31.5 | 3.3 | 1,837 | 33.6 | 1.1 |

| Moved since age 1 (%) | 7,266 | 24.1 | 1,757 | 20.6 | 1,825 | 11.5 | 1,847 | 48.6 | 1,837 | 15.4 | |||||

| Community Characteristics | |||||||||||||||

| Community has hospital (%) | 7,136 | 51.3 | 1,669 | 31.9 | 1,783 | 47.4 | 1,847 | 34.4 | 1,837 | 89.8 | |||||

| Urban (%) | 7,261 | 36.5 | 1,757 | 35.2 | 1,825 | 24.8 | 1,842 | 66.3 | 1,837 | 19.4 | |||||

| Community wealth | 7,264 | −0.01 | 2.56 | 1,757 | 0.02 | 2.71 | 1,824 | −0.01 | 2.38 | 1,846 | −0.04 | 2.62 | 1,837 | −0.01 | 2.54 |

We used Stata 12.1 for data analysis. Formal ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Results

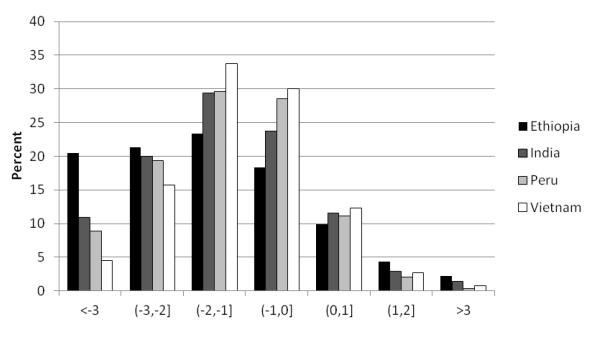

Figure 2 shows the distribution of HAZ(1). Ethiopia had the most children in the lowest two categories of z-scores in which children are considered “stunted”, followed by India, Peru, and then Vietnam. Vietnam had the most children in the categories (−1,0] and (0,1], followed by Peru, India, and then Ethiopia.

Figure 2.

Height-for-Age z-score at Age 1 Year, YL Countries

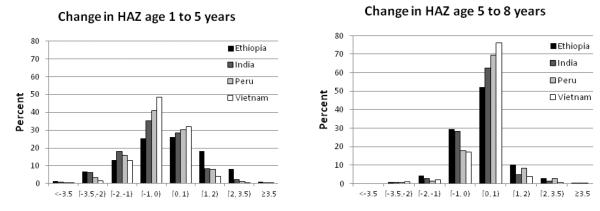

Figure 3 shows distributions of the total change in HAZ from ages 1 to 5 and 5 to 8 years. For over three-fifths (61%), absolute values of change between ages 1 and 5 years were greater than 0.5, and for a third (32.9%), they were greater than 1.0. For a quarter of the children, the absolute value of changes in HAZ between ages 1 and 5 years was less than 0.31. For the whole sample, the changes were fairly symmetrical around zero, with somewhat more (58%) having decreases from ages 1 to 5 years than having increases (42%).

Figure 3.

Change in HAZ, Ages 1 to 5 and 5 to 8 Years, YL Countries

The changes in HAZ from ages 5 to 8 years were smaller. Children in the lowest quartile of HAZ change had an absolute change of 0.16, the median value of absolute change was 0.34, and only 11.5% of the observations had absolute changes of more than one standard deviation. In contrast to the changes from ages 1 to 5 years, the vast majority (72.8%) of changes from ages 5 to 8 years were non-negative.

The distribution of HAZ change varied by country, with Ethiopia being the only country that had a majority of children (53.0%) with positive HAZ change from ages 1 to 5 years. Interestingly, however, Ethiopian children had the smallest change in HAZ from ages 5 to 8 years, with 64.7% experiencing positive HAZ change from age 5 to 8 years, compared to India (67.4%), Peru (79.5%) and Vietnam (79.0%). In contrast, Vietnamese children gained the least from ages 1 to 5 years, with only 36.3% experiencing positive HAZ change, yet gained substantially from ages 5 to 8 years.

Table 2 gives basic descriptive statistics. For key distal household variables: (1) Caregivers’ schooling averaged 5.0 completed grades, was lower for Ethiopia and India, and had fairly large within-country variation. (2) Fathers’ schooling averaged 6.8 grades, but with considerable variation across countries, again lower in Ethiopia and India. (3) Mothers’ height averaged 152.9 cm, with considerable within-country variation, particularly in Ethiopia. (4) The percentage of children who were female ranged from 46 to 49 percent.

For key distal community variables: (1) About half of the children (51.3%) overall lived in communities with hospitals, but a much higher proportion did in Vietnam (89.8%). (2) Urban residence was less common on average (36.5%), but included almost two-thirds (66.3%) of the households in Peru. (3) Variance in community wealth was highest in Ethiopia and lowest in Peru. In Peru, and India, communities clustered bimodally around richer and poorer values; in Vietnam communities were more evenly distributed with respect to community wealth, and in Ethiopia, many communities clustered around lower values.

Other controls: (1) the time between HAZ measurements averaged 51.5 months between ages 1 and 5 years, and 32.8 months between ages 5 and 8 years; with significant within-country variation, particularly in Peru. (2) About a quarter of the households (24.1%) moved between rounds 1 and 3, with almost half in Peru (48.6%) and only about a tenth (11.5%) in India. However, less than 10% of the sample switched from their initial urban/rural designation in subsequent observations (1% in Vietnam, 5% in India, 8% in Ethiopia, 23% in Peru).

ucHAZ, Ages 1 to 5 and 5 to 8 Years (Table 3): HAZ at age 1 year predicted 29% (Ethiopia) to 60% (Vietnam) of variation in HAZ at age 5 years. HAZ at age 5 years and the age dummies were more highly predictive of HAZ at age 8 years, predicting 53% (Ethiopia) to 74% (Vietnam) of the variation. The coefficients on the interactions between initial HAZ and age dummies were not jointly significant (p=0.18 to p=0.99). Children who were younger at round 1 measurement had lower HAZ at the end of the growth period, while older children had higher HAZ at the end of the period than the reference category of children measured initially at ages 12-14 months.

Table 3.

Regressions of HAZ at Round t on HAZ at Round t-1

| HAZ(5) regressed on HAZ(1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Ethiopia | India | Peru | Vietnam | |

| Height for age z-score year 1 | 0.35* [0.03] |

0.40* [0.03] |

0.64* [0.03] |

0.70* [0.02] |

| Age category 6-8 months | −0.12 [0.08] |

−0.35* [0.07] |

−0.27* [0.08] |

−0.52* [0.06] |

| Age category 9-11 months | −0.05 [0.09] |

−0.13 [0.07] |

−0.24* [0.08] |

−0.22* [0.05] |

| Age category 15-17 months | 0.10 [0.09] |

0.09 [0.08] |

0.13 [0.09] |

0.20* [0.07] |

| Constant | −0.92* [0.07] |

−1.01* [0.05] |

−0.62* [0.06] |

−0.46* [0.04] |

|

| ||||

| Observations | 1,757 | 1,825 | 1,847 | 1,837 |

| R-squared | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.60 |

| p-value test of interactionsa jointly = 0 | 0.99 | 0.21 | 0.34 | 0.23 |

|

| ||||

| HAZ(8) regressed on HAZ(5) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Height for age z-score year 2 | 0.70* [0.03] |

0.82* [0.02] |

0.80* [0.02] |

0.86* [0.02] |

| Age category 48-58 months | 0.12 [0.07] |

0.13 [0.11] |

0.07 [0.08] |

0.09 [0.08] |

| Age category 64-68 months | 0.03 [0.07] |

0.05 [0.06] |

−0.01 [0.06] |

−0.01 [0.04] |

| Age category 69-75 months | −0.11 [0.25] |

0.003 [0.09] |

0.07 [0.07] |

0.09 [0.10] |

| Constant | −0.22* [0.05] |

−0.12* [0.05] |

0.05 [0.04] |

0.06 [0.03] |

|

| ||||

| Observations | 1,757 | 1,825 | 1,847 | 1,837 |

| R-squared | 0.53 | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.74 |

| p-value test of interactions a jointly = 0 | 0.18 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.58 |

Standard errors in brackets;

p<0.05

Regressions include interactions between age categories and HAZ in round t-1 (not displayed).

Conversely, 40 to 71% of variation in HAZ at age 5 years was not predicted by a child’s HAZ at age 1 year, and 26 to 47% variation in HAZ at age 8 years was not predicted by HAZ at age 5 years.

Key Distal Household and Community Associations with HAZ(1) and ucHAZ (Table 4)

Table 4.

Regressions of HAZ(1) and ucHAZ

| Ethiopia | India | Peru | Vietnam | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| HAZ(1) | ucHAZ(1:5) | ucHAZ(5:8) | HAZ(1) | ucHAZ(1:5) | ucHAZ(5:8) | HAZ(1) | ucHAZ(1:5) | ucHAZ(5:8) | HAZ(1) | ucHAZ(1:5) | ucHAZ(5:8) | |

|

|

||||||||||||

| Lowest consumption quintile |

−0.13 [0.15] |

−0.27* [0.09] |

−0.18* [0.07] |

−0.02 [0.12] |

−0.05 [0.06] |

−0.03 [0.05] |

−0.24* [0.09] |

−0.11* [0.05] |

−0.03 [0.04] |

−0.30* [0.08] |

−0.09 [0.05] |

−0.00 [0.03] |

| 2nd consumption quintile |

−0.01 [0.13] |

−0.15 [0.08] |

−0.13 [0.07] |

−0.01 [0.11] |

−0.08 [0.05] |

−0.00 [0.05] |

−0.14 [0.09] |

−0.04 [0.05] |

−0.01 [0.04] |

−0.23* [0.07] |

−0.02 [0.05] |

0.02 [0.04] |

| 4th consumption quintile |

0.08 [0.11] |

−0.10 [0.05] |

0.03 [0.06] |

0.25* [0.11] |

0.02 [0.06] |

0.05 [0.05] |

0.02 [0.09] |

0.01 [0.05] |

−0.02 [0.04] |

−0.07 [0.09] |

0.09 [0.05] |

0.01 [0.03] |

| Highest consumption quintile |

0.14 [0.13] |

−0.07 [0.06] |

0.03 [0.05] |

0.30* [0.10] |

0.04 [0.06] |

0.07 [0.05] |

−0.19* [0.09] |

0.11* [0.04] |

0.03 [0.05] |

0.07 [0.09] |

0.13* [0.05] |

−0.00 [0.04] |

| Caregivers’ schooling, standardized |

0.20* [0.07] |

0.01 [0.04] |

−0.05 [0.03] |

0.054 [0.043] |

0.04 [0.03] |

0.05* [0.02] |

0.23* [0.05] |

0.05 [0.03] |

0.05* [0.02] |

0.11* [0.05] |

0.07* [0.03] |

0.03 [0.02] |

| Fathers’ schooling, standardized |

0.14* [0.05] |

0.09* [0.03] |

0.01 [0.02] |

0.14* [0.04] |

0.03 [0.02] |

−0.03 [0.02] |

0.08* [0.04] |

0.02 [0.03] |

0.03 [0.02] |

0.11* [0.05] |

0.01 [0.02] |

0.02 [0.02] |

| Mothers’ height, standardized |

0.15* [0.06] |

0.12* [0.05] |

0.04* [0.01] |

0.36* [0.05] |

0.14* [0.03] |

0.07* [0.02] |

0.30* [0.06] |

0.18* [0.04] |

0.05* [0.02] |

0.40* [0.04] |

0.15* [0.02] |

0.02 [0.03] |

| Child is female | 0.36* [0.08] |

−0.02 [0.05] |

0.07* [0.03] |

0.282* [0.06] |

0.01 [0.03] |

−0.02 [0.03] |

0.22* [0.06] |

−0.15* [0.04] |

0.05 [0.03] |

0.19* [0.05] |

−0.12* [0.03] |

0.07* [0.02] |

| Child moved after R1 | −0.63* [0.18] |

0.17 [0.10] |

−0.07 [0.07] |

−0.12 [0.10] |

0.14 [0.07] |

−0.05 [0.06] |

−0.03 [0.10] |

0.03 [0.04] |

−0.03 [0.04] |

−0.18* [0.08] |

−0.01 [0.07] |

0.03 [0.06] |

| Interval between measurements (months) |

−0.03 [0.03] |

0.00 [0.03] |

−0.05* [0.02] |

0.02 [0.02] |

0.03* [0.01] |

0.02 [0.01] |

−0.02 [0.02] |

0.01 [0.02] |

||||

| Age in months, R1 | −0.12* [0.02] |

−0.08* [0.01] |

−0.08* [0.01] |

−0.08* [0.01] |

||||||||

| Community has public or private hospital |

−0.54* [0.18] |

0.21* [0.10] |

−0.02 [0.11] |

−0.07 [0.12] |

0.19* [0.07] |

0.14* [0.05] |

−0.00 [0.15] |

0.01 [0.05] |

0.01 [0.06] |

0.31* [0.09] |

0.02 [0.06] |

−0.06 [0.05] |

| Site is urban | 0.01 [0.32] |

−0.19 [0.25] |

−0.06 [0.19] |

−0.33 [0.24] |

−0.03 [0.15] |

−0.08 [0.13] |

0.02 [0.13] |

0.13 [0.07] |

−0.00 [0.06] |

0.16 [0.16] |

0.21 [0.14] |

−0.02 [0.10] |

| Standardized value of community wealth |

0.19 [0.20] |

0.11 [0.13] |

0.08 [0.09] |

0.22 [0.13] |

0.10 [0.07] |

0.09 [0.05] |

0.23* [0.08] |

0.03 [0.04] |

0.00 [0.04] |

0.13 [0.07] |

−0.00 [0.06] |

0.03 [0.04] |

| Constant | −0.03 [0.34] |

1.65 [1.65] |

−0.15 [1.05] |

−0.39* [0.12] |

2.62* [0.81] |

−0.79 [0.48] |

−0.46* [0.19] |

−1.31* [0.56] |

−0.49 [0.31] |

−0.46* [0.12] |

1.17 [0.75] |

−0.27 [0.65] |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Observations | 1,757 | 1,757 | 1,757 | 1,825 | 1,825 | 1,825 | 1,847 | 1,847 | 1,847 | 1,837 | 1,837 | 1,837 |

| Rsquared | 0.144 | 0.094 | 0.028 | 0.141 | 0.102 | 0.065 | 0.282 | 0.159 | 0.028 | 0.274 | 0.122 | 0.017 |

|

| ||||||||||||

|

Test: Consumption jointly zero (p-value) |

0.544 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.001 | 0.335 | 0.348 | 0.007 | 0.017 | 0.790 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.950 |

Notes: Standard errors in brackets;

p<0.05. For HAZ(1), consumption is from R2. For ucHAZ(1:5), consumption is from R2 and months between measurements is number of months between R1 and R2 measurements; for ucHAZ(5:8), consumption is from R3 and months between measurements is number of months between R2 and R3 measurements. Continuous variables measured in standard deviation units. R-squared based on Fisher’s z transformation.

HAZ(1)

Key distal household and community characteristics and controls predicted from 14% (India) to 28% (Peru) of variation in HAZ(1).

Key Distal Household Characteristics: Household consumption per capita was significantly associated (joint significance p<0.05) with HAZ(1) in India, Peru, and Vietnam. In India, children from the two highest consumption quintiles had a quarter to almost a third of a standard deviation higher HAZ(1) than those from the third quintile, while in Vietnam, those in the two lowest consumption quintiles had a quarter to almost a third of a standard deviation lower HAZ(1) than those from the third quintile. Caregivers’ schooling was associated with 0.11 (Vietnam) to 0.23 (Peru) higher HAZ(1) for every additional standard deviation of completed schooling. Fathers’ schooling was also positive and significant in all four countries, associated with 0.08 (Peru) to 0.14 (Ethiopia) higher HAZ(1) for every additional standard deviation of completed schooling. Mothers’ height was also an important predictor, significant in all four countries, with associations ranging from 0.15 (Ethiopia) to 0.40 (Vietnam) higher HAZ(1) for every additional standard deviation of mothers’ height. Girls also had significantly higher HAZ(1) in all four countries.

Key Distal Community Characteristics: The presence of a hospital was significant and negative in Ethiopia, while it was significant and positive in Vietnam. There were no significant associations with community wealth or urban vs. rural residence for any country, with the exception of community wealth in Peru, where a one standard deviation increase in community wealth was associated with 0.23 higher HAZ(1).

ucHAZ(1:5)

Key distal household and community characteristics and controls predicted 9% (Ethiopia) to 16% (Peru) of variation in ucHAZ(1:5).

Key Distal Household Characteristics: Household consumption per capita was significantly associated with ucHAZ(1:5) for Ethiopia, Peru, and Vietnam. In Ethiopia, the lowest consumption quintile had 0.27 lower ucHAZ(1:5). In Peru and Vietnam, this figure was closer to 0.10 lower ucHAZ(1:5). In Peru and Vietnam, the highest consumption quintile had 0.11 and 0.13 higher ucHAZ(1:5). Given that standard deviations of ucHAZ(1:5) ranged from 0.65 (Vietnam) to 0.92 (Ethiopia), the magnitudes of these associations are not negligible.

Caregivers’ schooling was only significant in Vietnam, where a one-standard-deviation increase in schooling was associated with 0.07 higher ucHAZ(1:5). Fathers’ schooling was only significant in Ethiopia, where a one-standard-deviation increase was associated with 0.09 higher ucHAZ(1:5), though there were sex-specific differences in robustness checks presented below. In Peru and Vietnam, females had significantly lower ucHAZ(1:5) (0.15 and 0.12, respectively).

Mothers’ height was significantly associated with ucHAZ(1:5) in all countries, with a one-standard-deviation increase in height associated with 0.12 (Ethiopia) to 0.18 (Peru) higher ucHAZ(1:5) (0.12 in India and 0.15 in Vietnam).

Key Distal Community Variables: Living in a community with a hospital was associated with higher ucHAZ(1:5) for Ethiopia (0.21) and India (0.19). There were no significant associations between ucHAZ(1:5) and urban residence (as an additive dummy) or community wealth.

ucHAZ(5:8)

Key distal household and community characteristics and controls predicted 2% (Vietnam) to 7% (India) of variation in ucHAZ(5:8). While the predictive power of the model was lower for this age range, there were still some significant associations with magnitudes that were similar to those of the 1-5 years age range.

Key Distal Household Characteristics and ucHAZ(5:8): Consumption quintile was only jointly significant for Ethiopia (where the lowest consumption quintile had 0.18 lower ucHAZ(5:8)). Caregivers’ schooling was significant for India and Peru, with 0.05 higher ucHAZ for a one standard deviation increase in schooling in both. There were no significant associations with fathers’ schooling. Mothers’ height was significant in all countries except Vietnam. Females had 0.07 higher ucHAZ(5:8) in Ethiopia and Vietnam.

Key Distal Community Characteristics and ucHAZ(5:8): Hospital presence again was significant only for India, associated with 0.14 higher ucHAZ(5:8). Associations with urban residence and community wealth were not significant.

We also pooled all countries (and included interactions between country dummies and each right-side variable) to test for heterogeneity across countries (pair-wise comparisons in table 5). HAZ(1): There was heterogeneity in the associations with consumption quintile by country. There was no heterogeneity across countries for coefficient estimates on fathers’ schooling, and they were positive and significant for all four countries. In contrast, the coefficient estimate for caregivers’ schooling was significantly higher in magnitude in Peru than in India, the only country for which the coefficient was not significant. There were significant differences in mothers’ height across countries, with the coefficient estimate for Ethiopia much smaller and significantly different from Vietnam and from India. There were significant differences in the coefficient estimates for the presence of hospital across the different countries, and they varied from large and positive in Vietnam to large and negative in Ethiopia. There was no statistically significant heterogeneity for urban-rural status or community wealth.

Table 5.

Summary of Significant Associations and Pair-wise Differences, Regressions of HAZ(1), and ucHAZ with and without Interactions

| HAZ(1) | ucHAZ(1:5) | ucHAZ(5:8) | HAZ(1) | ucHAZ(1:5) | ucHAZ(5:8) | HAZ(1) | ucHAZ(1:5) | ucHAZ(5:8) | HAZ(1) | ucHAZ(1:5) | ucHAZ(5:8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| (No interactions) | (No interactions) | (Sex interactions) | (Urban interactions) | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Pair-wise comparisons1 | p<0.05 | p<0.05 | p<0.05 | |||||||||

| Consumption quintile | (4th):V≠I (5th):P≠I, E≠P, P≠V |

I,P,V | E,P,V | E | I,P,V | E,V | E | I,V | E,V | E | ||

| Caregivers’ schooling | P≠I | E≠I, E≠P | E,P,V | V | I,P | E,P,V | P | E,P | I | |||

| Fathers’ schooling | E≠P, E≠V | E,I,P,V | E | I,V | E | I | ||||||

| Mothers’ height | E≠I, E≠V | E,I,P,V | E,I,P,V | E,I,P | I,P,V | E,I,P,V | E,I | E,P,I | E,I,P,V | E,I | ||

| Female | E≠I | P≠I, V≠I, E≠P, E≠V |

E≠I, V≠I | E,I,P,V | P,V | E,V | V | E,I,P,V | P, V | E,V | ||

| Moved after R1 | E≠I, E≠P | E,V | E,V | E | ||||||||

| Time between measurement |

I,P,V | I | I | |||||||||

| Age at R1 | E,I,P,V | E,I,P,V | E,I,P,V | |||||||||

| Hospital presence | V≠I, E≠I, E≠P, E≠V |

P≠I, V≠I, E≠V | V≠I | E,V | E,I | I | E,V | E,I | I | E,P,V | E,I,P | |

| Site is urban | V | |||||||||||

| Community wealth | P | P | I | I | ||||||||

|

Sex Interactions: Fathers’ schooling |

P | E | ||||||||||

| Urban Interactions: | ||||||||||||

| Consumption quintile | E,V | V | V | |||||||||

| Mother’s schooling | ||||||||||||

| Fathers’ schooling | V | |||||||||||

| Mothers’ height | I | |||||||||||

| Female | E,P | I | ||||||||||

| Moved after R1 | ||||||||||||

| Time between measurement |

V | |||||||||||

| Hospital presence | P | E,I,P,V | I | |||||||||

| Community wealth | V | |||||||||||

| Test: interactions jointly significant at p<0.05 |

E,P,V | E | I | E,P,V | E,I,P,V | E,I,P,V | ||||||

Notes: E = Ethiopia, I = India, P = Peru, V = Vietnam;

Coefficient estimates for consumption quintiles may differ across countries due to differences in absolute per capita consumption levels in these four countries. Indeed we do find significant differences across countries for a number of the coefficient estimates for the consumption quintiles, which is consistent with the impacts of different absolute consumption per capita across the four countries. See etable 2 for analysis using PPP-adjusted consumption per capita.

Ethiopia was unique in regard to the relationship between paternal schooling and ucHAZ(1:5), and between caregivers’ schooling and ucHAZ(5:8). There was no statistical heterogeneity in the positive associations between mothers’ height and ucHAZ(1:5) and ucHAZ(5:8). There was also no statistically significant heterogeneity by country in consumption for ucHAZ(1:5) or ucHAZ(5:8), despite the differing contexts. There was heterogeneity for the presence of hospitals for both ucHAZ(1:5) and ucHAZ(5:8).

As an alternative to the use of relative consumption quintiles, we conducted the analysis using PPP-adjusted consumption per capita (etable 2). The significant relationship between HAZ(1) and consumption is robust when using the PPP-adjusted consumption per capita in Ethiopia, India, and Vietnam, associated with an increase of 0.08 (Vietnam) to 0.22 (India) in HAZ(1). For ucHAZ(1:5), the relationship is significant for Peru and India, where it is associated with an increase of 0.04 and 0.10, respectively. For ucHAZ(5:8), PPP-adjusted consumption per capita is significant for India, where it is associated with 0.10 increase in uHAZ(5:8).

In further robustness analysis (summary in table 5; etables 4-6), we found only one significant difference by sex (etable 5): in Ethiopia the coefficient estimate for paternal schooling was associated with ucHAZ(1:5) only for boys. However, in Peru, paternal schooling was associated with higher HAZ(1) for girls.

In all four countries, hospital presence was associated with significantly higher ucHAZ(1:5) in rural than in urban areas (etables 5-6). However, for ucHAZ(5:8), there was a strong positive association with hospital presence in urban India. There were some differences in the coefficient estimates for consumption by urban-rural designation, suggesting higher ucHAZ(1:5) for higher consumption quintiles in urban as compared to rural areas (India), but even lower ucHAZ(1:5) for lower consumption quintiles in urban areas (Vietnam). There were also some sex differences by urban-rural status, suggesting females in urban and rural areas were slightly disadvantaged compared to males in rural areas for ucHAZ(1:5) (Peru and Vietnam), ucHAZ(5:8) (Ethiopia and Vietnam), and HAZ(1) (Peru), and in Vietnam, the benefit for children of living in an area with a hospital was lower for girls than for boys.

Etable 1 shows the differences in means for the included versus excluded observations, some of which are significant. In robustness analysis including these observations (with a dummy and interaction terms added to equation (1)), we found that including observations with missing data or outliers would have significantly altered some of our findings, but qualitatively, the directions of the associations are the same.

Discussion

Our results reinforce previous findings that parental schooling, wealth, and maternal height are important determinants of HAZ(1), and provide evidence for the continued importance of these variables for growth after age 1 year, given HAZ(1) values. We also found that hospital presence in rural communities was strongly associated with ucHAZ. This finding is consistent with previous research linking nutritional status with access to health care services (Fay et al. 2005). We also observed some differential associations by child sex, which may have policy implications if policymakers and organizations want to bolster the physical, cognitive, and emotional development and growth of girls in developing countries.

In our data, HAZ(1) predicted 29-60% of the variation in HAZ(5), so the distal factors that predict HAZ(1) may have persistent effects. At the same time, 40%-71% of the variation in HAZ(5) is not predicted by HAZ(1). Our analysis suggests that many of the same factors may continue to be associated with growth beyond age 1 year through age 5 years. We were unable to predict much of the variation in ucHAZ(5:8) and the estimated significant associations tended to be smaller, suggesting that associations with some of these distal factors may lessen with age. This evidence supports the hypothesis that interventions prior to age 5 years have a higher potential impact, as distal factors may have already influenced child growth during the ages 0-5 years.

We found some heterogeneity in coefficient estimates for HAZ(1) and ucHAZ across countries. At the same time, fathers’ schooling, caregivers’ schooling, and mothers’ height for HAZ(1) and ucHAZ and consumption quintiles for ucHAZ, when significant, had associations in the same direction in all countries, with the magnitudes varying only slightly and not significantly. Our study had some limitations. We focused our attention on a limited set of key distal household and community factors and did not consider possible proximal and behavioral factors such as caregiving (hygiene, nutrition, responsive feeding, basic health routines, and care), early stimulation (cognitive and learning related interactions), responsivity (social and affective interactions, relationship building) and structure (discipline and protection from abuse). Inclusion of these mediating pathways probably would bias our estimates as they are likely to be determined by the same key distal characteristics we considered here as explanatory variables. We leave investigation of such proximal determinants to future investigations with other data.

Also, we were unable to examine growth from age 2 to 5 years to represent growth in early childhood subsequent to growth from conception to age 2 years (often characterized as a critical period) due to data limitations. However, in analysis using the Institute for Nutrition in Central America and Panama (Guatemala) nutritional supplementation study data (Stein et al. 2008), in which there were multiple measures over the first 7 years of age, we found that HAZ measures at ages 6 to 17.9 months predict well HAZ at age 24 months (for ages 6, 12, and 18 months, correlations with HAZ at age 24 months were r=0.74, 0.83, 0.91, respectively). If similar correlations across ages also hold for populations of YL countries, the cross-sectional patterns in HAZ at ages 6 to 18 months that were observed in the YL data represent fairly well cross-sectional patterns in HAZ that likely held for these same children at 24 months, even if the overall distribution in HAZ may have declined fairly substantially from 12 to 24 months. We were also limited by having only three HAZ measurements, with the first one around age 1 year. There may well be interesting patterns that can be uncovered only with more data on shorter age intervals, but we could not investigate such possibilities with the existing data. In addition, migration may have caused some biases in the estimates, resulting for example in biases towards zero for the community variables because the variables used were nosier representations of the underlying community characteristics for migrants than for non-migrants.

Despite such limitations, our study contributed to understanding of the extent of child growth not predicted by measurements at age 1, and of important correlates with child growth at age 1 year and unpredicted child growth from ages 1 to 5 and 5 to 8 years. In particular, maternal height and consumption had similar associations across very different developing country contexts, which is encouraging regarding external validity. The study also opened up important questions for future research, suggesting a focus in greater detail on the nature of child growth over broad age ranges through infancy and childhood, further examination of associations of household consumption per capita and maternal height to understand better what they truly represent and what are the proximal pathways through which they have associations, and an exploration of likely pathways through which key household and community correlates of child growth may affect girls differently from boys. Finally, our findings have important implications for policymakers wishing to enhance child growth in developing countries, suggesting emphasis on increasing health service availability in rural areas, possibly targeting girls with public health interventions, and reinforcing the emphasis on early life, but with the important caveat that growth trajectories may still be malleable after infancy, particularly through the 1-5 year age range.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

◀Height-for-age z-score (HAZ) at age 1 yr and age did not predict 40-71% of variation in HAZ at age 5 yrs

◀HAZ at age 5 yrs and age did not predict 26-47% of variation in HAZ at age 8 yrs

◀HAZ at age 1 was associated with parental schooling, consumption, and mothers’ height

◀Unpredicted HAZ change was associated with consumption and maternal height

◀Associations differed by urban-rural site and by country and child gender

Acknowledgements

This study is based on research funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (Global Health Grant OPP1032713), Eunice Shriver Kennedy National Institute of Child Health and Development (Grant R01 HD070993), and Grand Challenges Canada (Grant 0072-03 to the Grantee, The Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania). The data come from Young Lives, a 15-year survey investigating the changing nature of childhood poverty in Ethiopia, India (Andhra Pradesh), Peru and Vietnam (www.younglives.org.uk). Young Lives is core-funded by UK aid from the Department for International Development (DFID) and co-funded from 2010 to 2014 by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Eunice Shriver Kennedy National Institute of Child Health and Development, Grand Challenges Canada, Young Lives, DFID or other funders. The funders had no involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of this study; and in the decision to submit it for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Appendix A. Supplementary Data Supplementary data related to this article can be found at [INSERT LINK TO ONLINE FILES]

References

- Adair LS. Filipino children exhibit catch-up growth from age 2 to 12 years. Journal of Nutrition. 1999;129(6):1140–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.6.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison P. Missing Data. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2001. (Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, 07-136). [Google Scholar]

- Behrman JR, Calderon MC, Preston S, Hoddinott J, Martorell R, Stein AD. Nutritional supplementation of girls influences the growth of their children: prospective study in Guatemala. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;90:1372–1379. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Ezzati M, Mathers C, Rivera J. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. The Lancet. 2008;371(9608):243–260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? The Lancet. 2003;361(9376):2226–2234. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch AM, Baqui AH, van Ginneken JK. Early-life Determinants of Stunted Adolescent Girls and Boys in Matlab, Bangladesh. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2008;26(2):189–199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield LE, Richard SA, Rivera JA, Musgrove P, Black R. Stunting, wasting, and micronutrient deficiency disorders. In: Jamison D, Breman J, Measham A, et al., editors. Disease control priorities in developing countries. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; Washington, DC: 2006. pp. 551–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checkley W, Epstein LD, Gilman RH, Cabrera L, Black RE. Effects of acute diarrhoea on linear growth in Peruvian children. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157:166–175. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coly AN, Milet J, Diallo A, Ndiaye T, Bénéfice E, Simondon F, Wade S, Simondon KB. Preschool stunting, adolescent migration, catch-up growth, and adult height in young Senegalese men and women of rural origin. Journal of Nutrition. 2006;136:2412–2420. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.9.2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crookston B, Penny ME, Alder SC, Dickerson TT, Merrill RM, Stanford JB, Porucznik CA, Dearden KA. Children who recover from early stunting and children who are not stunted demonstrate similar levels of cognition. The Journal of Nutrition. 2010;140:1996–2001. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.118927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crookston BT, Dearden KA, Alder SC, Porucznik CA, Stanford JB, Merrill RM, Dickerson TT, Penny ME. Impact of early and concurrent stunting on cognition. Journal of Maternal & Child Nutrition. 2011;7:397–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2010.00255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels MC, Adair LS. Growth in young Filipino children predicts schooling trajectories through high school. The Journal of Nutrition. 2004;134(6):1439–1446. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.6.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Onis M. Commentary: Socioeconomic inequalities and child growth. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;32:503–505. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deOnis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(9):660. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.043497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Onis M, Blössner M, Borghi E. Prevalence and trends of stunting among pre-school children, 1990-2020. Public Health Nutrition. 2011;15:142–8. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011001315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt CL, Gordon-Larsen P, Adair LS. Growth patterns of Fili- pino children indicate potential compensatory growth. Annals of Human Biology. 2005;32:3–14. doi: 10.1080/03014460400027607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay M, Leipziger QW, Yepes T. Achieving child-health-related Millennium Development Goals: the role of infrastructure. World Development. 2005;33(8):1267–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Filmer D, Scott K. Assessing asset indices. Demography. 2012;49:359–392. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett JL, Ruel, M.T. Are determinants of rural and urban food security and nutritional status different? Some insights from Mozambique. World Development. 1999;27(11):1955–1975. [Google Scholar]

- Godoy RA, Nyberg C, Eisenberg DTA, Magvanjav O, Shinnar E, Leonard WR, Gravlee C, Reyes-Garcia V, McDade TW, Huanca T, Tanner S. Short but Catching Up: Statural Growth Among Native Amazonian Bolivian Children. American Journal of Human Biology. 2010;22:336–347. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantham-McGregor S, Cheung YB, Cueto S, Glewwe P, Richter L, Strupp B. Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. The Lancet. 2007;369(9555):60–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60032-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott J, Maluccio JA, Behrman JR, Flores R, Martorell R. The impact of nutrition during early childhood on income, hours worked, and wages of Guatemalan adults. The Lancet. 2008;371:411–416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço BH, Villamor E, Augusto RA, Cardoso MA. Determinants of linear growth from infancy to school-aged years: a population-based follow-up study in urban Amazonian children. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:265. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundeen EA, Behrman JR, Crookston BT, Dearden KA, Engle P, Georgiadis A, Penny ME, Stein AD, on behalf of the Young Lives Determinants and Consequences of Child Growth Project Team . Child growth from age 1 to age 8 y in four low- and middle-income countries: Young Lives. Emory University; Atlanta, GA: 2012. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Maluccio J, Hoddinott J, Behrman J, Quisumbing A, Martorell R, Stein AD. The impact of nutrition during early childhood on education among Guatemalan adults. Economics Journal. 2009;119:734–763. [Google Scholar]

- Outes I, Porter C. Catching up from early nutritional deficits? Evidence from rural Ethiopia. Economics & Human Biology. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2012.03.001. published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaltin E, Hill K, Subramanian SV. Association of maternal stature with offspring mortality, underweight, and stunting in low- to middle-income countries. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303:1507–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaratnam JK, Marcus JR, Flaxman AD, Wang H, Levin-Rector A, Dwyer L, Costa M, Lopez AD, Murray CJL. Neonatal, postneonatal, childhood, and under-5 mortality for 187 countries, 1970–2010: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 4. The Lancet. 2010;375:1988–2008. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60703-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgh G, Herrera MG, Nestel P, el Amin A, Fawzi WW. Dietary vitamin A intake and nondietary factors are associated with reversal stunting in children. Journal of Nutrition. 2000;130:2520–2526. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.10.2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semba RD, de Pee S, Sun K, Sari M, Akhter N, Bloem MW. Effect of parental formal education on risk of stunting in Indonesia and Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet. 2008;371:322–328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein AD, Wang M, Martorell R, Norris SA, Adair LS, Bas I, Sachdev HS, Bhargava SK, Fall CHD, Gigante DP, Victora CG. Growth patterns in early childhood and final attained stature: Data from five birth cohorts from low- and middle-income countries. American Journal of Human Biology. 2010;22:353–359. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein AD, Hoddinott J, Melgar P, Martorell R. Cohort profile: The Institute of Nutrition of Central America and Panama (INCAP) Nutrition Trial Cohort Study. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;37(4):716–720. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian SV, Ackerson LK, Davey Smith G, John NA. Association of maternal height with child mortality, anthropometric failure, and anemia in India. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301:1691–701. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C, Hallal PC, Martorell R, Richter L, Sachdev HS. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. The Lancet. 2008;371(9609):340–357. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora CG, de Onis M, Hallal PC, Blössner M, Shrimpton R. Worldwide timing of growth faltering: revisiting implications for interventions. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e473–80. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker SP, Grantham-McGregor SM, Himes JH, Powell CA, Chang SM. Early childhood supplementation does not benefit the long-term growth of stunted children in Jamaica. Journal of Nutrition. 1996;126:3017–3024. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.12.3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatrica Supplement. 2006;450:76–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.tb02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.