Abstract

Like other solid tumors, colorectal cancer (CRC) is a genomic disorder in which various types of genomic alterations, such as point mutations, genomic rearrangements, gene fusions, or chromosomal copy number alterations, can contribute to the initiation and progression of the disease. The advent of a new DNA sequencing technology known as next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized the speed and throughput of cataloguing such cancer-related genomic alterations. Now the challenge is how to exploit this advanced technology to better understand the underlying molecular mechanism of colorectal carcinogenesis and to identify clinically relevant genetic biomarkers for diagnosis and personalized therapeutics. In this review, we will introduce NGS-based cancer genomics studies focusing on those of CRC, including a recent large-scale report from the Cancer Genome Atlas. We will mainly discuss how NGS-based exome-, whole genome- and methylome-sequencing have extended our understanding of colorectal carcinogenesis. We will also introduce the unique genomic features of CRC discovered by NGS technologies, such as the relationship with bacterial pathogens and the massive genomic rearrangements of chromothripsis. Finally, we will discuss the necessary steps prior to development of a clinical application of NGS-related findings for the advanced management of patients with CRC.

Keywords: Next-generation sequencing, Cancer genomics, Colorectal cancers, Personalized medicine, The cancer genome atlas

Core tip: Next-generation sequencing (NGS)-driven genomic analyses are facilitating the genomic dissection of various types of human cancers, including colorectal cancer (CRC). This review contains an up-to-date summary of recent NGS-based CRC studies and an overview of how these efforts have advanced our understanding of colorectal carcinogenesis with novel biomarkers for genome-based cancer diagnosis and personalized cancer therapeutics.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancers (CRC) are the third most common human malignancy, and are also the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide[1]. Early detection of premalignant lesions such as adenomatous polyps has decreased the risk of CRCs[2], however, cases which are initially undetected and progress to advanced CRC with distant metastasis are still unfortunately incurable[3]. The development of CRC is a complex and heterogeneous process arising from an interaction between multiple etiological factors, including genetic factors[4] and environmental factors such as diet and lifestyle[5]. Recently, significant progress has been made in the characterization of genetic and epigenetic alterations in CRC genomes in support of the genomic view of colorectal carcinogenesis. Like other types of human solid tumors, CRC genomes harbor various types of genomic alterations ranging from small-scale changes (i.e., point mutations or small indels) to large-scale chromosomal copy number changes or rearrangements. Some of these alterations may contribute to colorectal carcinogenesis as oncogenic drivers, but the full spectrum of driver genomic alterations in CRC genomes is still incomplete.

For decades, the genome-wide profiling of cancer genomes has been mainly conducted using hybridization-based microarray technologies (i.e., expression microarrays and array-based comparative genomic hybridization)[6,7] or low-throughput Sanger sequencing[8]. Recently, the advancement of DNA sequencing technologies - next-generation sequencing (NGS) - has revolutionized the speed and throughput of DNA sequencing[9,10]. Table 1 lists the NGS platforms widely used in the characterization of cancer genomes. Since the first attempt at cancer genome sequencing using NGS technology[11], successful sequencing by NGS has been accomplished in many major human cancer types[12,13] including gastrointestinal malignancies such as esophageal[14], gastric[15], colorectal[16], and hepatocellular carcinomas[17,18]. The NGS-based studies of CRC genomes are summarized in Table 2. These studies identified the unique mutational spectrum and novel targets of genomic alterations in respective cancer types with biological and clinical significance.

Table 1.

The next-generation sequencing platforms for cancer genome analysis

| NGS types | Whole genome sequencing | Exome sequencing | Epigenome sequencing1 | RNA-seq |

| Source | Genomic DNA | Genomic DNA (targeted) | Genomic DNA (targeted) | RNA |

| Alteration types | Point mutations and indels, rearrangements2, DNA copy number changes | Point mutations and indels | DNA methylation and posttranscriptional histone modifications | Gene fusions3, alternative splicing events, point mutations and indels |

Epigenome sequencing can be classified into chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-based methods to detect genomic domains with epigenetic modifications[80] and more direct DNA methylation sequencing such as bisulfite-sequencing[59,60];

From whole genome sequencing data, the genomic rearrangements and DNA copy number changes are generally detected by paired-end mapping[81] and read-depth based methods[82], respectively;

Gene fusions can also be identified by paired-end, high-coverage whole genome sequencing, but the transcription-related events such as exon skipping or other alternative splicing events can only be identified by RNA-seq. NGS: Next-generation sequencing.

Table 2.

The list of next-generation sequencing-based studies of colorectal cancer genomes

| Ref. | NGS types | Major findings | Alteration types and software used |

| Bass et al[16] | WGS (9 pairs; tumor-matched normal) | Oncogenic fusion (VTI1A-TCG7L2) | Point mutations (MuTect[83]) |

| Indels (Indelocator)1 | |||

| Rearrangements (dRanger)1 | |||

| TCGA consortium | WGS (97 pairs; low-pass) | See main text | Point mutations (MuTect) |

| RNA-seq (218 tumors) | Recurrent mutations (MutSig)1 | ||

| Exome-seq (254 pairs) | DNA copy numbers (BIC-seq[82]) | ||

| Rearrangements (BreakDancer[81]) | |||

| Timmermann et al[84] | Exome-seq (2 pairs, one MSI-H and one MSS) | Comparison of mutation spectrum between MSI-H and MSS CRC genomes | Point mutation and indel (Vendor-provided GS reference mapper, Roche) |

| Zhou et al[85] | Exome-seq (1 series: normal-adenoma-adenocarcinoma) | Comparison of benign and malignant CRC genomes in the same patient | Point mutation and indel (Samtools[86]) |

| Kloosterman et al[73] | WGS (4 pairs; primary-metastasis-matched normals)Targeted 1300 genes (4 pairs) | Comparison of primary or metastatic CRC genomes | Chromothripsis and mutations (Burrow-Wheeler aligner[87] based in-house tools) |

| Brannon et al[88] (Proceedings) | Targeted 230 genes (50 pairs: primary-metastasis-matched normals) | Comparison of primary or metastatic CRC genomes | IMPACT (integrated mutation profiling of actionable cancer targets) |

| Yin et al[89] | RNA-seq (2 pairs) | RNA-seq based mutation study | Point mutations and indels (Samtools) |

Description of the software is available at https://confluence.broadinstitute.org/display/CGATools/. NGS: Next-generation sequencing; CRC: Colorectal cancer; TCGA: The cancer genome atlas; MSI: Microsatellite instability.

SOMATIC MUTATIONS IN CRC GENOMES

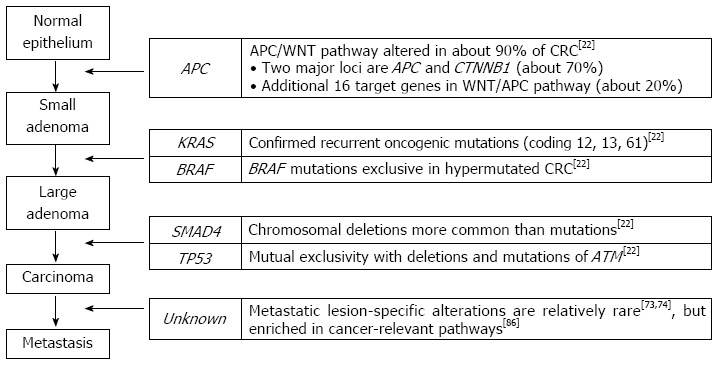

Like other solid tumors, CRC is thought to initiate and progress through a series of genetic and epigenetic alterations. The progression model of colorectal carcinogenesis (i.e., from adenomatous polyp to benign adenoma, eventually progressing to invasive adenocarcinoma) has been referred to as a classical cancer evolution model in which the CRC genome acquires somatic alterations in a progressive manner throughout several developmental stages. In this model, dysregulation of the APC/WNT pathway via the inactivation of APC occurs in the normal epithelium as an initiation process, while the loss of TP53 and TGF-β/SMAD4 gives rise to clonal expansion of tumor cells in the invasive adenocarcinoma (Figure 1)[4,19]. However, the genomic alterations associated with colorectal carcinogenesis may be more complicated than previously assumed. A complete and comprehensive catalogue of oncogenic drivers associated with colorectal carcinogenesis remains to be discovered.

Figure 1.

A classical progression model of colorectal carcinogenesis. A classical progression model of colorectal carcinogenesis is illustrated with genes whose alterations are responsible for each of the progressive steps. The right panel shows recent next-generation sequencing-based reports of the corresponding genes. CRC: Colorectal cancer; ATM: Ataxia telangiectasia mutated.

To extend the mutational spectrum in CRC genomes, the first exome-wide screening of approximately 13000 genes was conducted by Sanger sequencing[20]. This analysis identified approximately 800 somatic non-silent mutations in 11 CRC genomes. To distinguish oncogenic drivers from neutral passenger mutations, they identified the mutations whose frequency was significantly higher than random. The analysis revealed 69 potential oncogenic driver mutations in CRC genomes, including several well-known cancer-related genes (i.e., TP53, APC, KRAS, SMAD4, and FBXW7), and a large number of previously uncharacterized genes. Since they examined two distinct tumor types (CRC and breast cancers), they were able to identify the differences in the panel of candidate driver genes as well as identify the differences in the mutation spectrum between CRC and breast cancer genomes. The difference in the mutation spectrum (i.e., the predominance of C:G to T:A transitions over C:G to G:C transversions in CRC genomes) was confirmed by a subsequent kinase sequencing study across various cancer types[21] and by a recent whole-genome sequencing of nine CRC genomes[16].

NGS-BASED CRC STUDIES - LESSONS FROM THE CANCER GENOME ATLAS CRC STUDY

The advance in sequencing technologies has facilitated the use of genome sequencing for cancer genome studies, including CRC genomes. The largest NGS-based exome sequencing study of CRC genomes to date (approximately 200 CRC genomes) has recently been published as part of the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) projects[22]. The platforms used in the multidimensional genomic characterization of CRC genomes were compared with those used for glioblastoma multiforme in 2008 (Table 3)[23]. Two important lessons from this large-scale multidimensional TCGA CRC analysis are as follows:

Table 3.

The platforms used in the Cancer Genome Atlas consortium

| Alteration types | Glioblastoma multiforme (2008, TCGA) | Colorectal cancers (2012, TCGA) |

| Point mutations, indels | Sanger sequencing | Illumina GA and HiSeq DNA Sequencing1 |

| ABI SOLiD DNA Sequencing1 | ||

| DNA copy numbers | Agilent Human CGH Microarray 244 A | Agilent CGH Microarray Kit 1 × 1 M and 244 A |

| Affymetrix Genome-Wide SNP Array 6.0 | Affymetrix Genome-Wide SNP Array 6.0 | |

| Illumina Human Infinium 550 K BeadChip | Illumina Infinium 550 K and 1M-Duo BeadChip | |

| DNA Methylation | Illumina Infinium DNA Methylation 27 | Illumina Infinium DNA Methylation 27 |

| Illumina DNA Methylation Cancer Panel I | ||

| Transcriptome | Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 | Illumina GA and HiSeq RNA sequencing1 |

| Agilent 244 K Custom Array | Agilent 244 K Custom Array | |

| Affymetrix Human Exon 1.0 ST Array | ||

| MicroRNA | Agilent 8 × 15 K Human miRNA Microarray | Illumina GA and HiSeq miRNA sequencing1 |

| Whole-genome sequencing | N/A | Illumina HiSeq DNA sequencing1 |

Next-generation sequencing-based platforms are noted. The platforms used in the genomic characterization of glioblastoma multiforme in 2008 (left) and colorectal cancer genomes in 2012 (right) are shown. TCGA: The Cancer Genome Atlas.

First, similar to previous findings[20], most of the significantly recurrent mutations were observed at known cancer-related genes, such as APC, TP53, KRAS, PIK3CA, FBXW7, SMAD4, and NRAS. The study also revealed frequent coding microsatellite instability (MSI) on ACVR2A, TGFBR2, MSH3, and MSH6 by manual examination of sequencing reads for 30 known MSI loci. Although the majority of recurrent mutations were previously known, a number of novel mutations were also identified, which may have functional implications on colorectal tumorigenesis. For example, the mutations in SOX9[24], FAM123B[25], and 14 other genes are known to be implicated in the altered WNT/APC pathway. Although the biallelic inactivation of APC and the activating mutation of CTNNB1 encoding β-catenin are two major events that occurred in about 74% of the total CRC genomes studied, the mutations and deletions of an additional 16 (about 18%) genes in the WNT/APC pathway were not negligible, leading to the conclusion that nearly all CRC genomes (about 92%) have an alteration in the WNT/APC pathway[22].

A study which assigned potential molecular functions to rare mutations in CRC genomes using the pathway-level convergence was previously reported[26]. Thus, pathway- or network-level information from available resources (i.e., Gene Ontology[27]) and other methodologies to predict the functional impacts of non-synonymous point mutations[28,29] may help determine the potential functions of rare mutations and distinguish oncogenic drivers in studies with small-sized cohorts. This issue is also related to the sample-size problem in study design. Due to the limits on sample availability and research budget, many of the cancer mutation studies use a small discovery cohort for the generation of candidate mutations that are subsequently validated in an extended set. Increasing the number of samples in the initial discovery set would be beneficial in identifying events that are not highly recurrent but are still clinically meaningful (i.e., gene fusions involving receptor tyrosine kinases with available inhibitors). For example, the frequency of gene fusions such as ALK[30] and RET[31] in lung adenocarcinomas and FGFR[32] in glioblastoma multiforme are less than 5%. Although the level of recurrence is still the generally accepted functional indicator of genomic alterations[33,34], the incorporation of knowledge from other resources may facilitate the identification of biological or clinically relevant mutations more efficiently in a moderate-sized cohort.

Second, the concordant and discordant relationships between alterations examined across the samples may reveal valuable functional insights. The concordant relationship adopts the concepts of co-expressed networks in which the genes with significantly correlated expression levels (measured by Pearson’s correlation coefficients or mutual information) across diverse cellular conditions may have a functional relationship[35-37]. Importantly, TCGA-related studies revealed that the exclusivity between the potential oncogenic drivers may be common. For example, TCGA ovarian cancer study showed that the alterations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 (including germline or somatic mutations and epigenetic silencing via promoter hypermethylation) are mutually exclusive to each other[38]. The method to identify the pairs of exclusive genomic alterations is formulated as a standard analysis pipeline in TCGA projects as Mutual Exclusivity Modules (MEMo) in cancer[39]. In CRC genomes, MEMo analysis revealed that nearly half of the TCGA CRC genomes showed an exclusive relationship between the up-regulation of IGF2 and IRS2, and between the mutation of PIK3 pathway genes (PIK3CA and PIK3R1) and the homozygous deletion of PTEN[22]. This suggests that the IGF2-IRS2 axis is a major signaling pathway upstream of the PI3K pathway in CRC genomes[22]. The mutual exclusivity between the mutations of TP53 and ATM was also identified in the TCGA CRC genomes[22].

GENOMIC REARRANGEMENTS AND GENE FUSIONS IN CRC GENOMES

Bass et al[16] reported whole-genome sequencing (sequencing coverage about 30-fold) of nine CRC genomes. By comparing them with matched normal genomes, they identified approximately 140000 putative somatic mutations per CRC genome, which included approximately 700 non-silent point mutations and indels in coding sequences. One advantage of whole-genome sequencing is that the genome-wide landscape of the mutation spectrum in CRC genomes can be obtained, such as the relative paucity of mutations in exons and higher mutation frequency in intergenic regions than introns. This phenomenon is probably due to the selection pressure and transcription-coupled repair, and is consistent with other types of cancer genomes such as prostate cancers[40] and multiple myelomas[41]. Since most of the non-synonymous nucleotide substitutions were observed at known cancer genes such as KRAS, APC, and TP53, they focused on novel aspects that can only be identified from paired-end whole-genome sequencing data such as chromosomal rearrangements. Among the approximately 700 candidate rearrangements, 11 events give rise to in-frame fusion genes. The extended screening further revealed that VTI11A-TCF7L2 fusion is recurrent (3 out of 97 primary CRC genomes) and the siRNA-mediated down-regulation of this fusion transcript reduced the anchorage-independent cell growth in vitro, indicative of their potential oncogenic activity.

The low-pass (sequencing coverage approximately 3-4-fold) whole-genome sequencing of 97 TCGA CRC genomes also identified three genomes harboring NAV2-TCF7L1 fusion[22]. The predicted protein structures of fusion proteins lacked the β-catenin binding domain of TCF3 (encoded by TCF7L1), which is similar to the fusion of VTI11A-TCF7L2 that lacks the β-catenin binding domain of TCF4 (encoded by TCF7L2). In addition, the inactivation of TTC28 by genomic rearrangements is of note since this event is recurrent (21 out of 97 cases) and involves multiple partners for rearrangements in TCGA CRC genomes[22]. Gene fusions can also be identified from transcriptome sequencing, so called RNA-seq[42,43]. A recent RNA-seq-based study revealed recurrent gene fusions involving R-spondin family members of RSPO2 and RSPO3[44]. These fusions were exclusive to APC mutations in the observed CRC genomes, suggesting their potential roles in activating the APC/WNT pathway in colorectal carcinogenesis. Cancer-related gene fusion events are gaining attention since there has been no effective gene fusion screening method other than NGS-based paired-end sequencing. More importantly, many of the fusion candidates discovered so far represent oncogenic drivers and clinically actionable events (i.e., the fusion activates potential oncogenes such as tyrosine kinases that can be inhibited by small molecule inhibitors) as shown in recent studies[30-32] including the C2orf44-ALK fusion in CRC[45].

In addition, it was proposed that the genomic rearrangements in individual cancer genomes can be used as personal cancer markers to trace the disease activity (i.e., to detect recurrences or to evaluate the tumor burden of residual diseases)[46]. The proposed method, personalized analysis of rearranged ends, was applied to four cancer genomes, including two CRCs in a pilot test. It was demonstrated that the PCR-based quantification of the rearranged DNA in the plasma correlated well with the treatment course of CRC[46].

MICROSATELLITE INSTABILITY IN CRC GENOMES

Microsatellites are short tandem repeat sequences present at millions of sites in the human genome[47]. MSI defined as the length polymorphism of microsatellite repeat sequences, can arise due to a defect in the DNA mismatch repair system[48]. MSI is common in hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancers, also known as Lynch syndrome, where germline mutations of MLH1 and MSH2 are commonly observed[49,50]. About 15% of sporadic CRC are microsatellite-unstable, where transcriptional silencing of MLH1 by promoter hypermethylation is common[51,52]. The microsatellite-unstable sporadic CRC has distinct clinical and genomic features (i.e., common in right-sided colons and elderly females, and nearly diploid, etc.) compared to microsatellite-stable, but aneuploid CRC genomes. The key genes targeted by somatic point mutations and MSI-induced frameshifting mutations are different between the microsatellite-stable and -unstable CRC genomes, as shown in the TCGA CRC study[22]. Since the MSI analysis in the TCGA CRC study was limited to a manual search of exome sequencing reads for about 30 known loci with frequent MSI (i.e., TGFBR2, ACVR2A, BAX, etc.), a question remains as to whether we can fully exploit the NGS technology to screen the locus-level MSI in an exome- or genome-wide scale. One interesting report by Wang et al[53] showed that pancreatic cell lines with a homozygous deletion of MLH1 (which is a frequent target of promoter hypermethylation in MSI CRC genomes) frequently harbors truncating indels in TP53 and TGFBR2. This suggests that whole genome- or exome-sequencing data may be used for large-scale MSI screening to identify novel MSI events targeting tumor suppressor genes in cancer genomes.

NGS AND CRC EPIGENETICS

For decades, DNA methylation has been studied as one of the major cancer-related epigenetic modifications. Until recently, it was recognized that cancer genomes are undermethylated overall, but some genomic loci have focal DNA hypermethylation[54,55]. Transcriptional silencing by focal hypermethylation, especially at the CpG islands of gene promoters, is among the putative inactivating mechanisms of tumor suppressor genes in cancer genomes and often preferred over the inactivation by irreversible nucleotide substitutions[56]. Yet, the landscape of cancer-associated DNA methylation seems more dynamic than previously anticipated, as revealed by genome-wide CRC methylome studies[57,58]. Two recent CRC methylome studies used NGS-based sequencing of bisulfite-treated genomic DNA for bp-resolution methylome profiling[59,60]. Both studies proposed the presence of large blocks of DNA hypomethylation that occupied almost half of the genomes. Additionally, they reported that such findings as the genome-wide methylation variability of the adenoma genome is an intermediate between those of normal epithelium and CRC[60] and the domains of DNA hypomethylation regionally coincided with those of nuclear lamina attachment[59]. In addition, DNA methylation profiling has been also proposed as a means of early CRC diagnosis using non-invasive resources (i.e., blood- or stool-based)[61,62], which can benefit from NGS technologies.

NOVEL ASPECTS OF CRC GENOMES BY NGS STUDIES

NGS-based genome analysis may facilitate the identification of previously unrecognized, novel features of CRC cancer genomes. For example, owing to its high-throughput nature, NGS analysis may be able to detect the presence of foreign DNA sequences originating from bacterial or viral pathogens. Although the clear association between pathogens and certain human tumor types has been demonstrated in limited cases such as hepatitis B or C viruses with hepatocellular carcinoma, there have been ongoing efforts to use the sequencing data for pathogen discovery[63,64]. For instance, Kostic et al[65,66] analyzed nine CRC whole genome sequencing data sets[16] using their algorithm of PathSeq to identify microbial sequences enriched in CRC genomes compared to those in matched normal genomes. They observed that the sequences of Fusobacterium are enriched in CRC genomes, which was also shown in transcriptome sequencing results by independent researchers[67]. Although the oncogenic role of Fusobacterium in CRC genomes is only beginning to be elucidated[68], these results highlight the possibility that NGS-driven sequencing data will be a valuable resource to identify novel pathogens associated with human cancers.

Chromothripsis is a unique cancer genome-associated phenomenon in which tens to hundreds of chromosomal rearrangements occur in a “one-off” cellular event[69]. This phenomenon involves one or a few chromosomes in which massive chromosomal fragmentation is followed by rejoining of the fragments[70]. This results in unique genomic signatures that can be identified by paired-end sequencing (i.e., massive intrachromosomal rearrangements in the affected chromosome that can be visualized in a Circos diagram[71]) or from copy number profiles (i.e., frequent oscillations between two copy number states indicative of retained and lost chromosomal fragments). After the first discovery of chromothripsis in one chronic lymphocytic leukemia patient by paired-end sequencing[69], Stephens et al[69] also examined the copy number profiles of 746 cancer cell lines, observing that 2.4% of them (18 cell lines) showed the genomic signatures of chromothripsis. Recently, Kim et al[72] reported the tumor type-specific frequencies of chromothripsis as measured from a large-scale copy number profile of about 8000 cancer genomes including CRCs. Six out of 366 CRC genomes (1.8%) in the database showed the signature of chromothripsis (i.e., significant frequent alternation between different copy number states[72]) and the frequency was not substantially different from the average across the database (1.5%). Of note, Kloosterman et al[73] reported the paired-end whole-genome sequencing results of four CRC genomes with liver metastases, observing that all cases harbored evidence of chromothripsis. In addition, the comparison between primary and metastatic CRC genomes revealed that most genomic arrangements are shared both by primary and metastatic genomes, indicating that metastasis occurs quite rapidly with few additional mutational events, which was also proposed in mutation-based CRC genome studies[74]. Along with chromothripsis, several unique features of cancer genomes have been reported in breast cancer genomes (kataegis; regional hypermutations near rearrangement breakpoints)[75] and in prostate cancer genomes (chromoplexy; chains of copy-neutral rearrangements across multiple chromosomes)[40], which may expand the mutational categories in CRC genomes.

CONCLUSION

We have discussed the recent NGS-based CRC studies in various genomic aspects. The progress of CRC genomic analysis (but not exclusive to CRC) can be summarized into three issues: (1) the screening of clinically actionable targets for personalized targeted medicine; (2) the advancement of pathway-level understanding in colorectal carcinogenesis using a large-scale cohort; and (3) the identification of novel features or mutation types in CRC genomes. In terms of the first issue, Roychowdhury et al[76] reported an advanced NGS-based cancer patient management protocol that includes low-pass whole-genome, exome, and transcriptome sequencing of cancer genomes. The notable aspects of the protocol are the timeline (< 4 wk after enrollment) and cost (approximately 3600 USD), as well as the presence of a multidisciplinary sequencing tumor board (STB) to evaluate the mutation profiles of the patients and make a clinical decision. In their pilot study, the STB evaluated the sequencing results from a patient with metastatic CRC harboring NRAS mutation and CDK8 amplification and concluded that BRAF/MEK inhibitors and PI3K and/or CDK inhibitors could be beneficial for the patient. Second, the more complete and comprehensive collection of CRC-related somatic genomic alterations will advance the pathway-level understanding of colorectal carcinogenesis and help distinguish the oncogenic drivers from neutral passengers, as seen in large-scale meta-analyses of cancer genome profiles[72,77]. Finally, NGS-driven genomic studies are already reporting novel features of cancer genomes beyond the traditional mutational categories. Besides the MSI and chromothripsis we discussed, some researchers used publicly available genome sequencing data (including those of CRC genomes[16]) and reported novel mitochondrial mutations[78] and the activity of human retrotranspositions in the cancer genomes[79]. Taken together, NGS technology will advance our understanding of CRC genomes and the obtained knowledge will lead to a better diagnosis and personalized targeted therapeutics for CRC management.

Footnotes

Supported by Cancer Evolution Research Center (2012R1A5A2047939), South Korea

P- Reviewers Parsak C S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Wang CH

References

- 1.Shike M, Winawer SJ, Greenwald PH, Bloch A, Hill MJ, Swaroop SV. Primary prevention of colorectal cancer. The WHO Collaborating Centre for the Prevention of Colorectal Cancer. Bull World Health Organ. 1990;68:377–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O’Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Waye JD, Schapiro M, Bond JH, Panish JF. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977–1981. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Ko CY. Colon cancer survival rates with the new American Joint Committee on Cancer sixth edition staging. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1420–1425. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fearon ER. Molecular genetics of colorectal cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:479–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huxley RR, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Clifton P, Czernichow S, Parr CL, Woodward M. The impact of dietary and lifestyle risk factors on risk of colorectal cancer: a quantitative overview of the epidemiological evidence. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:171–180. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim MY, Yim SH, Kwon MS, Kim TM, Shin SH, Kang HM, Lee C, Chung YJ. Recurrent genomic alterations with impact on survival in colorectal cancer identified by genome-wide array comparative genomic hybridization. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1913–1924. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liotta L, Petricoin E. Molecular profiling of human cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:48–56. doi: 10.1038/35049567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stratton MR, Campbell PJ, Futreal PA. The cancer genome. Nature. 2009;458:719–724. doi: 10.1038/nature07943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahvejian A, Quackenbush J, Thompson JF. What would you do if you could sequence everything? Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1125–1133. doi: 10.1038/nbt1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shendure J, Ji H. Next-generation DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1135–1145. doi: 10.1038/nbt1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ley TJ, Mardis ER, Ding L, Fulton B, McLellan MD, Chen K, Dooling D, Dunford-Shore BH, McGrath S, Hickenbotham M, et al. DNA sequencing of a cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukaemia genome. Nature. 2008;456:66–72. doi: 10.1038/nature07485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mardis ER. Genome sequencing and cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2012;22:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyerson M, Gabriel S, Getz G. Advances in understanding cancer genomes through second-generation sequencing. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:685–696. doi: 10.1038/nrg2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agrawal N, Jiao Y, Bettegowda C, Hutfless SM, Wang Y, David S, Cheng Y, Twaddell WS, Latt NL, Shin EJ, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of esophageal adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:899–905. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zang ZJ, Cutcutache I, Poon SL, Zhang SL, McPherson JR, Tao J, Rajasegaran V, Heng HL, Deng N, Gan A, et al. Exome sequencing of gastric adenocarcinoma identifies recurrent somatic mutations in cell adhesion and chromatin remodeling genes. Nat Genet. 2012;44:570–574. doi: 10.1038/ng.2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bass AJ, Lawrence MS, Brace LE, Ramos AH, Drier Y, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, Voet D, Saksena G, Sivachenko A, et al. Genomic sequencing of colorectal adenocarcinomas identifies a recurrent VTI1A-TCF7L2 fusion. Nat Genet. 2011;43:964–968. doi: 10.1038/ng.936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujimoto A, Totoki Y, Abe T, Boroevich KA, Hosoda F, Nguyen HH, Aoki M, Hosono N, Kubo M, Miya F, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of liver cancers identifies etiological influences on mutation patterns and recurrent mutations in chromatin regulators. Nat Genet. 2012;44:760–764. doi: 10.1038/ng.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li M, Zhao H, Zhang X, Wood LD, Anders RA, Choti MA, Pawlik TM, Daniel HD, Kannangai R, Offerhaus GJ, et al. Inactivating mutations of the chromatin remodeling gene ARID2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2011;43:828–829. doi: 10.1038/ng.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markowitz SD, Bertagnolli MM. Molecular origins of cancer: Molecular basis of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2449–2460. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sjöblom T, Jones S, Wood LD, Parsons DW, Lin J, Barber TD, Mandelker D, Leary RJ, Ptak J, Silliman N, et al. The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2006;314:268–274. doi: 10.1126/science.1133427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R, Dalgliesh GL, Hunter C, Bignell G, Davies H, Teague J, Butler A, Stevens C, et al. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007;446:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455:1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Topol L, Chen W, Song H, Day TF, Yang Y. Sox9 inhibits Wnt signaling by promoting beta-catenin phosphorylation in the nucleus. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:3323–3333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808048200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Major MB, Camp ND, Berndt JD, Yi X, Goldenberg SJ, Hubbert C, Biechele TL, Gingras AC, Zheng N, Maccoss MJ, et al. Wilms tumor suppressor WTX negatively regulates WNT/beta-catenin signaling. Science. 2007;316:1043–1046. doi: 10.1126/science/1141515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torkamani A, Schork NJ. Identification of rare cancer driver mutations by network reconstruction. Genome Res. 2009;19:1570–1578. doi: 10.1101/gr.092833.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng PC, Henikoff S. Predicting the effects of amino acid substitutions on protein function. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:61–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, Takada S, Yamashita Y, Ishikawa S, Fujiwara S, Watanabe H, Kurashina K, Hatanaka H, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448:561–566. doi: 10.1038/nature05945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kohno T, Ichikawa H, Totoki Y, Yasuda K, Hiramoto M, Nammo T, Sakamoto H, Tsuta K, Furuta K, Shimada Y, et al. KIF5B-RET fusions in lung adenocarcinoma. Nat Med. 2012;18:375–377. doi: 10.1038/nm.2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh D, Chan JM, Zoppoli P, Niola F, Sullivan R, Castano A, Liu EM, Reichel J, Porrati P, Pellegatta S, et al. Transforming fusions of FGFR and TACC genes in human glioblastoma. Science. 2012;337:1231–1235. doi: 10.1126/science.1220834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banerji S, Cibulskis K, Rangel-Escareno C, Brown KK, Carter SL, Frederick AM, Lawrence MS, Sivachenko AY, Sougnez C, Zou L, et al. Sequence analysis of mutations and translocations across breast cancer subtypes. Nature. 2012;486:405–409. doi: 10.1038/nature11154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beroukhim R, Getz G, Nghiemphu L, Barretina J, Hsueh T, Linhart D, Vivanco I, Lee JC, Huang JH, Alexander S, et al. Assessing the significance of chromosomal aberrations in cancer: methodology and application to glioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20007–20012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710052104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barabási AL, Oltvai ZN. Network biology: understanding the cell’s functional organization. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basso K, Margolin AA, Stolovitzky G, Klein U, Dalla-Favera R, Califano A. Reverse engineering of regulatory networks in human B cells. Nat Genet. 2005;37:382–390. doi: 10.1038/ng1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carter SL, Brechbühler CM, Griffin M, Bond AT. Gene co-expression network topology provides a framework for molecular characterization of cellular state. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2242–2250. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ciriello G, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N. Mutual exclusivity analysis identifies oncogenic network modules. Genome Res. 2012;22:398–406. doi: 10.1101/gr.125567.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berger MF, Lawrence MS, Demichelis F, Drier Y, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko AY, Sboner A, Esgueva R, Pflueger D, Sougnez C, et al. The genomic complexity of primary human prostate cancer. Nature. 2011;470:214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature09744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chapman MA, Lawrence MS, Keats JJ, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, Schinzel AC, Harview CL, Brunet JP, Ahmann GJ, Adli M, et al. Initial genome sequencing and analysis of multiple myeloma. Nature. 2011;471:467–472. doi: 10.1038/nature09837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maher CA, Kumar-Sinha C, Cao X, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Han B, Jing X, Sam L, Barrette T, Palanisamy N, Chinnaiyan AM. Transcriptome sequencing to detect gene fusions in cancer. Nature. 2009;458:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature07638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao Q, Caballero OL, Levy S, Stevenson BJ, Iseli C, de Souza SJ, Galante PA, Busam D, Leversha MA, Chadalavada K, et al. Transcriptome-guided characterization of genomic rearrangements in a breast cancer cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1886–1891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812945106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seshagiri S, Stawiski EW, Durinck S, Modrusan Z, Storm EE, Conboy CB, Chaudhuri S, Guan Y, Janakiraman V, Jaiswal BS, et al. Recurrent R-spondin fusions in colon cancer. Nature. 2012;488:660–664. doi: 10.1038/nature11282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lipson D, Capelletti M, Yelensky R, Otto G, Parker A, Jarosz M, Curran JA, Balasubramanian S, Bloom T, Brennan KW, et al. Identification of new ALK and RET gene fusions from colorectal and lung cancer biopsies. Nat Med. 2012;18:382–384. doi: 10.1038/nm.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leary RJ, Kinde I, Diehl F, Schmidt K, Clouser C, Duncan C, Antipova A, Lee C, McKernan K, De La Vega FM, et al. Development of personalized tumor biomarkers using massively parallel sequencing. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:20ra14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharma PC, Grover A, Kahl G. Mining microsatellites in eukaryotic genomes. Trends Biotechnol. 2007;25:490–498. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boland CR, Goel A. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2073–2087.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bronner CE, Baker SM, Morrison PT, Warren G, Smith LG, Lescoe MK, Kane M, Earabino C, Lipford J, Lindblom A. Mutation in the DNA mismatch repair gene homologue hMLH1 is associated with hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer. Nature. 1994;368:258–261. doi: 10.1038/368258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leach FS, Nicolaides NC, Papadopoulos N, Liu B, Jen J, Parsons R, Peltomäki P, Sistonen P, Aaltonen LA, Nyström-Lahti M. Mutations of a mutS homolog in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Cell. 1993;75:1215–1225. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90330-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herman JG, Umar A, Polyak K, Graff JR, Ahuja N, Issa JP, Markowitz S, Willson JK, Hamilton SR, Kinzler KW, et al. Incidence and functional consequences of hMLH1 promoter hypermethylation in colorectal carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6870–6875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Veigl ML, Kasturi L, Olechnowicz J, Ma AH, Lutterbaugh JD, Periyasamy S, Li GM, Drummond J, Modrich PL, Sedwick WD, et al. Biallelic inactivation of hMLH1 by epigenetic gene silencing, a novel mechanism causing human MSI cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8698–8702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang L, Tsutsumi S, Kawaguchi T, Nagasaki K, Tatsuno K, Yamamoto S, Sang F, Sonoda K, Sugawara M, Saiura A, et al. Whole-exome sequencing of human pancreatic cancers and characterization of genomic instability caused by MLH1 haploinsufficiency and complete deficiency. Genome Res. 2012;22:208–219. doi: 10.1101/gr.123109.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Herman JG, Baylin SB. Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2042–2054. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrg816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan TA, Glockner S, Yi JM, Chen W, Van Neste L, Cope L, Herman JG, Velculescu V, Schuebel KE, Ahuja N, et al. Convergence of mutation and epigenetic alterations identifies common genes in cancer that predict for poor prognosis. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frigola J, Song J, Stirzaker C, Hinshelwood RA, Peinado MA, Clark SJ. Epigenetic remodeling in colorectal cancer results in coordinate gene suppression across an entire chromosome band. Nat Genet. 2006;38:540–549. doi: 10.1038/ng1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Irizarry RA, Ladd-Acosta C, Wen B, Wu Z, Montano C, Onyango P, Cui H, Gabo K, Rongione M, Webster M, et al. The human colon cancer methylome shows similar hypo- and hypermethylation at conserved tissue-specific CpG island shores. Nat Genet. 2009;41:178–186. doi: 10.1038/ng.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berman BP, Weisenberger DJ, Aman JF, Hinoue T, Ramjan Z, Liu Y, Noushmehr H, Lange CP, van Dijk CM, Tollenaar RA, et al. Regions of focal DNA hypermethylation and long-range hypomethylation in colorectal cancer coincide with nuclear lamina-associated domains. Nat Genet. 2012;44:40–46. doi: 10.1038/ng.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hansen KD, Timp W, Bravo HC, Sabunciyan S, Langmead B, McDonald OG, Wen B, Wu H, Liu Y, Diep D, et al. Increased methylation variation in epigenetic domains across cancer types. Nat Genet. 2011;43:768–775. doi: 10.1038/ng.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Glöckner SC, Dhir M, Yi JM, McGarvey KE, Van Neste L, Louwagie J, Chan TA, Kleeberger W, de Bruïne AP, Smits KM, et al. Methylation of TFPI2 in stool DNA: a potential novel biomarker for the detection of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4691–4699. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Warren JD, Xiong W, Bunker AM, Vaughn CP, Furtado LV, Roberts WL, Fang JC, Samowitz WS, Heichman KA. Septin 9 methylated DNA is a sensitive and specific blood test for colorectal cancer. BMC Med. 2011;9:133. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, Moore PS. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1152586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weber G, Shendure J, Tanenbaum DM, Church GM, Meyerson M. Identification of foreign gene sequences by transcript filtering against the human genome. Nat Genet. 2002;30:141–142. doi: 10.1038/ng818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kostic AD, Ojesina AI, Pedamallu CS, Jung J, Verhaak RG, Getz G, Meyerson M. PathSeq: software to identify or discover microbes by deep sequencing of human tissue. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:393–396. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kostic AD, Gevers D, Pedamallu CS, Michaud M, Duke F, Earl AM, Ojesina AI, Jung J, Bass AJ, Tabernero J, et al. Genomic analysis identifies association of Fusobacterium with colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012;22:292–298. doi: 10.1101/gr.126573.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Castellarin M, Warren RL, Freeman JD, Dreolini L, Krzywinski M, Strauss J, Barnes R, Watson P, Allen-Vercoe E, Moore RA, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012;22:299–306. doi: 10.1101/gr.126516.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McCoy AN, Araújo-Pérez F, Azcárate-Peril A, Yeh JJ, Sandler RS, Keku TO. Fusobacterium is associated with colorectal adenomas. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stephens PJ, Greenman CD, Fu B, Yang F, Bignell GR, Mudie LJ, Pleasance ED, Lau KW, Beare D, Stebbings LA, et al. Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell. 2011;144:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jones MJ, Jallepalli PV. Chromothripsis: chromosomes in crisis. Dev Cell. 2012;23:908–917. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, Jones SJ, Marra MA. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim TM, Xi R, Luquette LJ, Park RW, Johnson MD, Park PJ. Functional genomic analysis of chromosomal aberrations in a compendium of 8000 cancer genomes. Genome Res. 2013;23:217–227. doi: 10.1101/gr.140301.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kloosterman WP, Hoogstraat M, Paling O, Tavakoli-Yaraki M, Renkens I, Vermaat JS, van Roosmalen MJ, van Lieshout S, Nijman IJ, Roessingh W, et al. Chromothripsis is a common mechanism driving genomic rearrangements in primary and metastatic colorectal cancer. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R103. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-10-r103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jones S, Chen WD, Parmigiani G, Diehl F, Beerenwinkel N, Antal T, Traulsen A, Nowak MA, Siegel C, Velculescu VE, et al. Comparative lesion sequencing provides insights into tumor evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4283–4288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712345105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nik-Zainal S, Alexandrov LB, Wedge DC, Van Loo P, Greenman CD, Raine K, Jones D, Hinton J, Marshall J, Stebbings LA, et al. Mutational processes molding the genomes of 21 breast cancers. Cell. 2012;149:979–993. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roychowdhury S, Iyer MK, Robinson DR, Lonigro RJ, Wu YM, Cao X, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Sam L, Balbin OA, Quist MJ, et al. Personalized oncology through integrative high-throughput sequencing: a pilot study. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:111ra121. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beroukhim R, Mermel CH, Porter D, Wei G, Raychaudhuri S, Donovan J, Barretina J, Boehm JS, Dobson J, Urashima M, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463:899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Larman TC, DePalma SR, Hadjipanayis AG, Protopopov A, Zhang J, Gabriel SB, Chin L, Seidman CE, Kucherlapati R, Seidman JG. Spectrum of somatic mitochondrial mutations in five cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:14087–14091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211502109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee E, Iskow R, Yang L, Gokcumen O, Haseley P, Luquette LJ, Lohr JG, Harris CC, Ding L, Wilson RK, et al. Landscape of somatic retrotransposition in human cancers. Science. 2012;337:967–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1222077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Park PJ. ChIP-seq: advantages and challenges of a maturing technology. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:669–680. doi: 10.1038/nrg2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen K, Wallis JW, McLellan MD, Larson DE, Kalicki JM, Pohl CS, McGrath SD, Wendl MC, Zhang Q, Locke DP, et al. BreakDancer: an algorithm for high-resolution mapping of genomic structural variation. Nat Methods. 2009;6:677–681. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xi R, Hadjipanayis AG, Luquette LJ, Kim TM, Lee E, Zhang J, Johnson MD, Muzny DM, Wheeler DA, Gibbs RA, et al. Copy number variation detection in whole-genome sequencing data using the Bayesian information criterion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:E1128–E1136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110574108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, Sivachenko A, Jaffe D, Sougnez C, Gabriel S, Meyerson M, Lander ES, Getz G. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Timmermann B, Kerick M, Roehr C, Fischer A, Isau M, Boerno ST, Wunderlich A, Barmeyer C, Seemann P, Koenig J, et al. Somatic mutation profiles of MSI and MSS colorectal cancer identified by whole exome next generation sequencing and bioinformatics analysis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhou D, Yang L, Zheng L, Ge W, Li D, Zhang Y, Hu X, Gao Z, Xu J, Huang Y, et al. Exome capture sequencing of adenoma reveals genetic alterations in multiple cellular pathways at the early stage of colorectal tumorigenesis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Brannon AR, Vakiani E, Scott S, Sylvester B, Kania K, Viale A, Solit D, Berger M. Targeted next-generation sequencing of colorectal cancer identified metastatics specific genetic alterations. BMC Proceedings. 2012;6:P3. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yin H, Liang Y, Yan Z, Liu B, Su Q. Mutation spectrum in human colorectal cancers and potential functional relevance. BMC Med Genet. 2013;14:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-14-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]