Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the clinical results of angiography and embolization for massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage after abdominal surgery.

METHODS: This retrospective study included 26 patients with postoperative hemorrhage after abdominal surgery. All patients underwent emergency transarterial angiography, and 21 patients underwent emergency embolization. We retrospectively analyzed the angiographic features and the clinical outcomes of transcatheter arterial embolization.

RESULTS: Angiography showed that a discrete bleeding focus was detected in 21 (81%) of 26 patients. Positive angiographic findings included extravasations of contrast medium (n = 9), pseudoaneurysms (n = 9), and fusiform aneurysms (n = 3). Transarterial embolization was technically successful in 21 (95%) of 22 patients. Clinical success was achieved in 18 (82%) of 22 patients. No postembolization complications were observed. Three patients died of rebleeding.

CONCLUSION: The positive rate of angiographic findings in 26 patients with postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage was 81%. Transcatheter arterial embolization seems to be an effective and safe method in the management of postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

Keywords: Transcatheter arterial embolization, Postoperative hemorrhage, Complications, Surgery

Core tip: Postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage is a potentially fatal complication after abdominal surgery. It is difficult for surgeons to deal with it. Reoperation is often difficult or even unsuccessful in patients with postoperative hemorrhage, especially those with two or more previous abdominal operations, due to the anatomical inaccessibility of the arteries, postoperative adhesions, and inflammatory reactions. This study showed that transcatheter embolization was a useful microinvasive treatment option for the identification and occlusion of a massive bleeding site after abdominal surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage is a potentially fatal complication after abdominal surgery. It prolongs hospital stay, requires urgent radiological or surgical intervention, and increases mortality after abdominal surgery. The incidence of postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage after abdominal surgery is low, but increases with an increase in surgical procedures, severity of illness, and comorbid conditions. The incidence of postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage has been reported as 0.4%-4% in a recent series[1-7], and 2%-18% in earlier series[8-14]. Although recent studies have shown that its mortality has decreased, it remains a serious and life-threatening condition.

Traditionally, open ligation or excision has been considered to be the first-line therapeutic option for patients with massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage after abdominal surgery. However, the bleeding site is difficult to establish because of local inflammatory response after abdominal surgery. In addition, patients with postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage are reported to be poor candidates for emergency surgery because of cicatrization and friability of postoperative tissues[15].

Transcatheter angiographic embolization is a less invasive procedure that is known to be a safe and effective treatment to control massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage. With the development of endovascular techniques over the past decade, transarterial embolization has been widely used clinically for treatment of postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage after abdominal surgery, despite the possibility of gastrointestinal infarction[16-19].

In this study, we retrospectively reviewed and analyzed the angiographic findings and clinical outcomes of transarterial angiography and embolization in 26 patients with postoperative hemorrhage after abdominal surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by our institutional review board, and all patients gave their informed consent before the procedure. This study included 26 patients (22 male and 4 female) who underwent emergency transarterial angiography and embolization for postoperative hemorrhage after abdominal surgery between August 2007 and April 2012 at our hospital. The mean age was 57.2 years (range, 35-86 years). The average time of onset of postoperative hemorrhage was 27.7 d (range, 3-65 d). The abdominal surgery included surgery for gastric carcinoma (n = 13), pancreatic head carcinoma (n = 2), common bile duct carcinoma (n = 2), duodenal papilla carcinoma (n = 2), ascending colon carcinoma (n = 1), severe pancreatitis (n = 1), gallbladder carcinoma (n = 1), cholangiolithiasis (n = 1), and intra-abdominal abscess (n = 1), as well as splenomegaly (n = 1), and mesenteric torsion (n = 1). Clinical presentations included hematemesis, hematochezia/melena, and bleeding from surgical drains. The volume of bleeding was > 1 L in 24 h.

The diagnostic angiography was performed via transfemoral approach, using a 5-F angiographic catheter (Cook, Bloomington, IN, United States) and a 5-F sheath (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan). In all cases, celiac and superior mesenteric angiography was routinely performed to detect the bleeding points. If this did not detect any bleeding points, inferior mesenteric angiography was performed. Hemorrhage was diagnosed based on the presence of extravasation of contrast agent, a pseudoaneurysm, and a fusiform aneurysm on angiography. Immediately after bleeding points were identified, transarterial embolization was performed with microcoils (Cook) and/or gelatin sponge (gelfoam particles) through a coaxial 2.7-F microcatheter (Terumo). Transarterial embolization was also performed with gelfoam in one patient without positive angiographic findings. Technical success was defined as devascularization of the target vessels on postembolization angiography. Clinical success was defined as cessation of clinical symptoms (including melena, hematemesis, and hematochezia), and no requirement for subsequent hemostatic interventions (such as surgery, endoscopic therapy, and second embolization).

The diameter of microcoils we used was from 2 to 6 mm. The length of microcoils was from 3 to 8 cm. The diameter of gelfoam particles was approximately 1 mm. Clinical follow-up period was 3 mo in all patients.

RESULTS

Fifteen patients presented with hematemesis/melena, and 11 patients presented with bleeding from surgical drains. Twenty-two patients had signs of shock (systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg and pulse rate > 100 beats/min). The clinical features and angiographic findings are summarized in Table 1. Results of transarterial embolization are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Clinical features of patients with postoperative hemorrhage after abdominal surgery

| Case | Sex | Age (yr) | Diseases | Surgical procedure | Interval from operation to bleeding (d) | Clinical presentations |

| 1 | Male | 61 | Gastric carcinoma | Gastrectomy | 11 | Haematemesis/melena |

| 2 | Male | 72 | Pancreatitis | Pancreatitis necrosectomy | 15 | Bleeding from drain |

| 3 | Male | 46 | Duodenal papilla carcinoma | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 38 | Bleeding from drain |

| 4 | Male | 64 | Gastric carcinoma | Gastrectomy | 14 | Bleeding from drain |

| 5 | Male | 37 | Gastric carcinoma | Gastrectomy | 27 | Haematemesis/melena |

| 6 | Female | 44 | Gastric carcinoma | Gastrectomy | 18 | Bleeding from drain |

| 7 | Male | 51 | Gastric carcinoma | Gastrectomy | 20 | Haematemesis/melena |

| 8 | Male | 35 | Gastric carcinoma | Gastrectomy | 28 | Haematemesis/melena |

| 9 | Male | 41 | Gastric carcinoma | Gastrectomy | 64 | Haematemesis/melena |

| 10 | Male | 56 | Pancreatic carcinoma | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 10 | Haematemesis/melena |

| 11 | Female | 45 | Gallbladder carcinoma | Extended cholecystectomy | 25 | Haematemesis/melena |

| 12 | Male | 86 | Ascending colon carcinoma | Right hemicolectomy | 34 | Hematochezia/melena |

| 13 | Male | 59 | Gastric carcinoma | Gastrectomy | 50 | Haematemesis/melena |

| 14 | Male | 69 | Gastric carcinoma | Gastrectomy | 49 | Bleeding from drain |

| 15 | Male | 61 | Intra-abdominal abscess | Excision of Intra-abdominal abscess | 3 | Bleeding from drain |

| 16 | Male | 65 | Common Bile duct carcinoma | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 29 | Bleeding from drain |

| 17 | Male | 73 | Gastric carcinoma | Gastrectomy | 38 | Hematochezia/melena |

| 18 | Male | 60 | Bile duct carcinoma | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 29 | Bleeding from drain |

| 19 | Female | 62 | Gastric carcinoma | Gastrectomy | 21 | Haematemesis/melena |

| 20 | Male | 80 | Duodenal papilla carcinoma | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 8 | Bleeding from drain |

| 21 | Male | 42 | Pancreatic carcinoma | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 46 | Haematemesis/melena |

| 22 | Male | 45 | Splenomegaly | Splenectomy | 9 | Bleeding from drain |

| 23 | Male | 56 | Bile duct stone | Choledocholithotomy | 26 | Bleeding from drain |

| 24 | Female | 62 | Gastric carcinoma | Gastrectomy | 65 | Hematochezia/melena |

| 25 | Male | 76 | Gastric carcinoma | Gastrectomy | 29 | Haematemesis/melena |

| 26 | Male | 40 | Mesenteric torsion | Partial intestinal resection | 15 | Haematemesis/melena |

Table 2.

Angiographic findings and clinical results of patients with postoperative hemorrhage after abdominal surgery

| Case | Angiography finding | Embolized artery | Embolic agent | Clinical results |

| 1 | Negative | None | None | Conservative treatment and clinical success |

| 2 | Negative | None | None | Repeat surgery and clinical success |

| 3 | Negative | None | None | Repeat surgery and clinical success |

| 4 | Negative | None | None | Repeat surgery and clinical success |

| 5 | Extravasation | None | None | Conservative treatment and clinical success |

| 6 | Extravasation | Inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery | Microcoil | Clinical success |

| 7 | Extravasation | Jejunal artery | Microcoil | Clinical success |

| 8 | Extravasation | Jejunal artery | Microcoil | Clinical success |

| 9 | Extravasation | Inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery | Microcoil | Clinical success |

| 10 | Extravasation | Great pancreatic artery | Gelfoam | Clinical success |

| 11 | Negative | Right hepatic artery and gastroduodenal artery | Gelfoam | Die of rebleeding |

| 12 | Extravasation | Ileocolic artery | Microcoil | Clinical success |

| 13 | Pseudoaneurysm | Gastroduodenal artery | Microcoil | Clinical success |

| 14 | Extravasation | Gastroduodenal artery | Microcoil | Clinical success |

| 15 | Pseudoaneurysm | superior rectal artery | Microcoil | Clinical success |

| 16 | Pseudoaneurysm | Gastroduodenal artery | Microcoil | Clinical success |

| 17 | Fusiform aneurysm | Gastroduodenal artery | Microcoil | Clinical success |

| 18 | Pseudoaneurysm | Common hepatic artery | Microcoil | Clinical success |

| 19 | Extravasation | Gastroduodenal artery | Microcoil | Die of rebleeding |

| 20 | Pseudoaneurysm | Gastroduodenal artery | Microcoil | Die of rebleeding |

| 21 | Fusiform aneurysm | Proper hepatic artery | Microcoil + gelfoam | Clinical success |

| 22 | Pseudoaneurysm | Splenic artery and Right gastroepiploic artery | Microcoil + gelfoam | Clinical success |

| 23 | Pseudoaneurysm | Right hepatic artery | Microcoil + gelfoam | Clinical success |

| 24 | Pseudoaneurysm | Inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery | Microcoil + gelfoam | Clinical success |

| 25 | Fusiform aneurysm | Gastroduodenal artery | Microcoil + gelfoam | Clinical success |

| 26 | Pseudoaneurysm | Jejunal artery | Microcoil + gelfoam | Clinical success |

Bleeding points near the surgical fields were detected by angiography in 21 (81%) of 26 patients. Positive angiographic findings included extravasation of contrast medium (n = 9) (Figure 1), pseudoaneurysms (n = 9) (Figures 2 and 3), and fusiform aneurysms (n = 3). Extravasation of contrast medium was observed from the jejunal artery (n = 2), gastroduodenal artery (n = 2), right hepatic artery and gastroduodenal artery (n = 1), great pancreatic artery (n = 1), inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (n = 1), dorsal pancreatic artery (n = 1), and ileocolic artery (n = 1). Pseudoaneurysms were found in the gastroduodenal artery (n = 3), common hepatic artery (n = 1), right hepatic artery (n = 1), inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (n = 1), splenic artery and right gastroepiploic artery (n = 1), jejunal artery (n = 1), and superior rectal artery (n = 1). The fusiform aneurysms were identified in the gastroduodenal artery (n = 2), and the proper hepatic artery (n = 1).

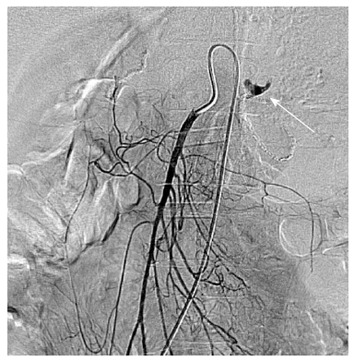

Figure 1.

A 35-year-old man with massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding after gastrectomy of gastric carcinoma. Selective superior mesenteric arteriography showed active arterial contrast extravasation (white arrow) from the jejunal artery.

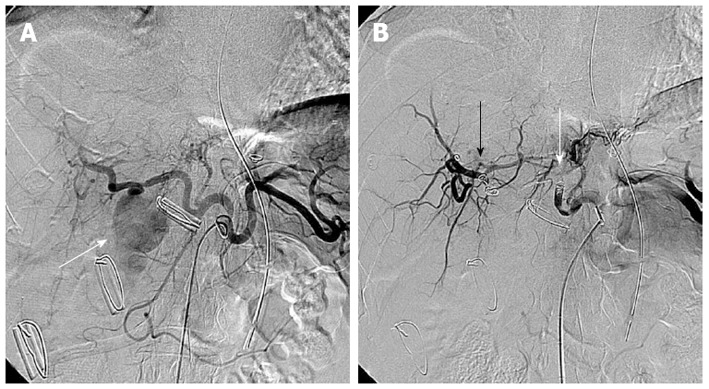

Figure 2.

A 56-year-old man presented with massive bleeding from surgical drains after choledocholithotomy due to common bile duct stone. A: Selective celiac arteriography showed a pseudoaneurysm (arrow) arising from the right hepatic artery; B: Selective celiac arteriography after embolization with microcoils and gelfoam demonstrated disappearance of the pseudoaneurysm. Embolic agents were inserted proximally (white arrow) and distally (black arrow) to the origin of the pseudoaneurysm.

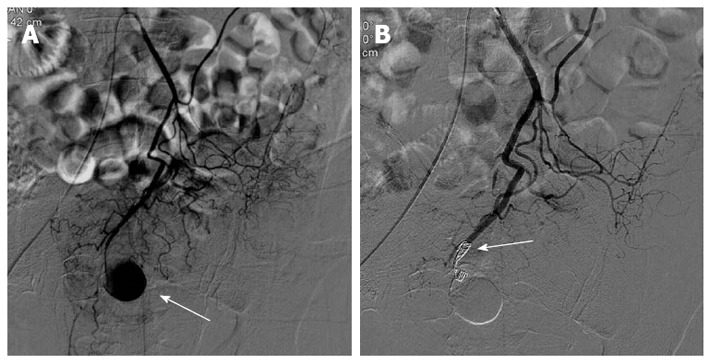

Figure 3.

A 61-year-old man presented with massive bleeding from surgical drains 3 d after excision of the intra-abdominal abscess. A: Selective inferior mesenteric arteriography shows a pseudoaneurysm (arrow) arising from the superior rectal artery; B: Selective inferior mesenteric arteriography after embolization with microcoils demonstrated complete occlusion (arrow) of the distal end of the superior rectal artery.

Transarterial embolization was performed in 20 of 21 patients with positive angiographic findings and one patient without positive angiographic findings. The embolized arteries are summarized in Table 2. Transarterial embolization of bleeding arteries was performed using a combination of microcoils and gelatin sponge in six cases, microcoils in 13 cases, and gelatin sponge in two cases. Transarterial embolization was not performed in one patient with positive angiographic finding, because the bleeding vessels were capillaries and could not be superselected. This patient underwent a second surgery after angiography immediately, and recovered after second surgery. However, there were five patients without positive angiographic findings in our study. Among these five patients, one died of rebleeding after blind embolization; one recovered after conservative treatment; and the other three also recovered after a second operation. In the surgical procedure, we found that the bleeding vessels were the splenic vein, portal vein behind the gastrointestinal anastomotic stoma, and left gastro-omental vein, respectively.

Technical success was achieved in 21 (95%) of 22 patients (20 patients with positive angiographic findings and one without positive angiographic findings). Clinical success was achieved in 18 (82%) of 22 patients. Three patients were unsuccessfully treated, including two with rebleeding after embolization, and one with rebleeding after blind embolization.

Postembolization complications such as intestinal ischemia and liver infarction did not occur in any patients during the follow-up period. Three patients (two with positive angiographic findings and one without positive angiographic findings) died of rebleeding after embolization.

DISCUSSION

Postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage is a life-threatening complication that occurs after abdominal surgery, particularly in the case of pancreaticoduodenectomy. The incidence of postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage after abdominal surgery is not high (0.4%-18%)[1-14]. Early hemorrhagic complications occur during the first 24 h postoperatively, and are usually caused by intraoperative technical failure, such as improper ligation of vessels in the operative area, and damages to small vessels during lymph node dissection. Delayed postoperative hemorrhage has a different pathophysiology of bleeding from early postoperative hemorrhage, and is complicated with intra-abdominal lesions such as marginal ulcer, anastomotic leakage, intra-abdominal abscess, and sepsis. In this study, the interval from surgery to bleeding ranged from 3 to 65 d, and was > 5 d for the majority of patients. The intra-abdominal complications such as pancreatic juice leakage, intestinal juice leakage, and intra-abdominal abscess were the main causes of gastrointestinal bleeding in our study. In order to reduce the rate of postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage after abdominal surgery, we must decrease abdominal surgery complications, such as stomal leak, marginal ulcer, and abscess.

Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are necessary to decrease the mortality of patients with postoperative hemorrhage after abdominal surgery. Endoscopy is usually served as the first-line diagnostic procedure. However, exact diagnosis via urgent gastrointestinal endoscopy can be severely impaired by excessive blood and clots in the gastrointestinal tract[20,21]. computed tomography angiography, Doppler ultrasound, and radionuclide scanning can also be used in the diagnosis of postoperative hemorrhage[5,22,23]. Compared with these diagnosis methods, angiography is quicker, safer, and more accurate to localize the bleeding points. In addition, angiography allows immediate embolization to stop gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Angiographic findings of postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage differ slightly from those of gastrointestinal hemorrhage without surgery. Positive angiographic findings of gastrointestinal hemorrhage without surgery mainly included extravasation of contrast medium, tumor staining, and vascular malformation. Charbonnet et al[24] reported that angiography had a positive angiographic rate of 31% in all consecutive patients without abdominal surgery. Kim et al[19] reported a positive angiographic rate of 79% in patients after abdominal surgery. However, positive angiographic findings of postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage mainly included extravasation of contrast medium and pseudoaneurysms. In our study, the positive findings were 81% (21 of 26 patients), and the rate of positive findings was higher than that of gastrointestinal hemorrhage without abdominal surgery, and was similar to that of gastrointestinal hemorrhage with surgery. Therefore, angiography should be the first-choice option for postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage after abdominal surgery, especially for patients with hemodynamic instability and poor general conditions. If celiac angiography fails to identify a source of bleeding, superselective angiography near the surgical field should be performed. However, angiography also has some limitations. For example, the result of angiography could be negative because the gastrointestinal bleeding is often intermittent or directly comes from veins or has been controlled by vasoactive agents. In this study, angiography demonstrated bleeding points in 21 of 26 patients. Reoperation was performed in three patients with negative angiographic findings. We found that the bleeding vessels were the left gastro-omental vein, portal vein behind the anastomotic stoma, and splenic vein.

Reoperation to control postoperative bleeding is the traditional approach to manage gastrointestinal hemorrhage after abdominal surgery. However, emergency surgical exploration has been reported to be associated with a mortality rate of as high as 64% in high-risk patients with hemodynamic instability and poor general conditions[25,26]. In addition, the surgical approach is often difficult or even unsuccessful in patients with postoperative hemorrhage, especially those with two or more previous abdominal operations, due to the anatomical inaccessibility of the arteries, postoperative adhesions, and inflammatory reaction. Endoscopy is another approach to manage postoperative hemorrhage[1-4,27-32]. However, emergency endoscopy for postoperative hemorrhage may be difficult owing to excessive blood and clots in the gastrointestinal tract, and inaccessibility of the bleeding sites in the small intestine.

Transarterial embolization is effective for postoperative hemorrhage, especially in patients with hemodynamic instability and poor general condition. However, the safety and clinical results of embolization have not been assessed in a large patient group. Beyer et al[5] reported that embolization had a success rate of 100% in nine patients with delayed hemorrhage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Miyamoto et al[33] demonstrated a success rate of 80% with superselective embolization in 10 patients with massive upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage after upper abdominal surgery. Compared with these studies, the clinical success rate (82%) of the present study was similar. However, the technical success rate in this study was 95% because we used high-resolution digital angiography and microcatheterization. Three patients died during the follow-up period. The cause of death was rebleeding after embolization, including one blind embolization.

The clinical results of blind embolization (defined as embolization without positive angiography) are controversial. Morris et al[34] found that blind embolization of the left gastric artery was effective in preventing rebleeding when an active bleeding site was localized by endoscopy. Kim et al[19] successfully treated four patients with blind embolization after an active bleeding site was identified by endoscopy or scintigraphy, or was suspicious on angiography. In our study, blind embolization was performed only in one patient after the bleeding site was localized by endoscopy. However, the patient died of rebleeding 3 d after the interventional procedure.

The most serious complications of postembolization are liver infarction and irreversible bowel ischemia. However, the liver can tolerate considerable arterial embolization without significant liver infarction, because the liver has a dual blood supply by the hepatic artery and portal vein, and the hepatic artery has abundant collateral pathways. Arterial embolization in the upper gastrointestinal tract above the ligament of Treitz is generally considered safe because of the rich collateral supply to the stomach and duodenum[34]. In contrast to the upper gastrointestinal tract, the lower gastrointestinal tract does not have a rich collateral artery, and is susceptible to embolization-induced ischemia. However, significant ischemia may be avoided if the embolic agent is delivered precisely to the bleeding sites. In our study, postembolization complications such as liver infarction and bowel ischemia were not encountered. Therefore, we believe that transarterial embolization is a safe method to treat postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

In conclusion, we retrospectively analyzed the angiographic findings and clinical outcomes of transarterial angiography and embolization in 26 patients with postoperative hemorrhage after abdominal surgery. Angiography was found to be a sensitive approach to detect the bleeding site, especially for patients with postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Transarterial embolization is an effective and safe method for the treatment of postoperative hemorrhage.

COMMENTS

Background

Gastrointestinal hemorrhage after abdominal surgery is an unusual complication. However, when it occurs, it can cause hemorrhagic shock that has a fatal outcome. This complication may occur as a result of anastomotic leakage, localized infection, or intraoperative arterial injury. Traditionally, reoperation is regarded as the first-line therapy. However, its usage is largely limited by the poor condition of patients with postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage and the difficulty in indentifying the bleeding sites during surgery. With advances in technology, a newer and less-invasive technique, transcatheter arterial embolization, has been developed and is reported to be safe and effective, especially in high-risk surgical patients.

Research frontiers

For postoperative gastrointestinal hemorrhage, the first important thing is to localize the bleeding site. Transarterial angiography is considered to be a better tool than endoscopy or noninvasive diagnostic imaging examinations such as computed tomography angiography and ultrasound. Transarterial access not only can provide diagnostic information but also has the advantage of intra-arterial embolization of the bleeding site simultaneously.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The surgical approach to control postoperative bleeding is often difficult or even unsuccessful in patients with postoperative hemorrhage, especially those with two or more previous abdominal operations, due to the anatomical inaccessibility of the arteries, postoperative adhesions, and inflammatory reaction. Therefore, its mortality rate was as high as 64% in high-risk patients with hemodynamic instability and poor general condition. However, with advances in techniques and microcatheters, transcatheter arterial embolization was performed to control postoperative bleeding. In this retrospective study, the technical success rate was 95%, and the clinical success rate was 82%. There were no procedure-related complications.

Applications

The results of the present study suggest that transcatheter arterial embolization is a safe and effective treatment for massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage following abdominal surgery.

Peer review

This was a good descriptive study in which the authors evaluated the clinical results of angiography and embolization for massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage after abdominal surgery. The results are interesting and suggest that transcatheter arterial embolization is a safe and effective treatment for massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage following abdominal surgery, especially for patients with hemodynamic instability and poor general condition.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers Beart R, Caumes E, Takeda R S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Tanizawa Y, Bando E, Kawamura T, Tokunaga M, Ono H, Terashima M. Early postoperative anastomotic hemorrhage after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2010;13:50–57. doi: 10.1007/s10120-009-0535-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malik AH, East JE, Buchanan GN, Kennedy RH. Endoscopic haemostasis of staple-line haemorrhage following colorectal resection. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:616–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martínez-Serrano MA, Parés D, Pera M, Pascual M, Courtier R, Egea MJ, Grande L. Management of lower gastrointestinal bleeding after colorectal resection and stapled anastomosis. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13:49–53. doi: 10.1007/s10151-009-0458-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linn TY, Moran BJ, Cecil TD. Staple line haemorrhage following laparoscopic left-sided colorectal resections may be more common when the inferior mesenteric artery is preserved. Tech Coloproctol. 2008;12:289–293. doi: 10.1007/s10151-008-0437-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beyer L, Bonmardion R, Marciano S, Hartung O, Ramis O, Chabert L, Léone M, Emungania O, Orsoni P, Barthet M, et al. Results of non-operative therapy for delayed hemorrhage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:922–928. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0818-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yekebas EF, Wolfram L, Cataldegirmen G, Habermann CR, Bogoevski D, Koenig AM, Kaifi J, Schurr PG, Bubenheim M, Nolte-Ernsting C, et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage: diagnosis and treatment: an analysis in 1669 consecutive pancreatic resections. Ann Surg. 2007;246:269–280. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000262953.77735.db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vernadakis S, Christodoulou E, Treckmann J, Saner F, Paul A, Mathe Z. Pseudoaneurysmal rupture of the common hepatic artery into the biliodigestive anastomosis. A rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. JOP. 2009;10:441–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon JM, Armstrong CP, Duffy SW, Elton RA, Davies GC. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding. A significant complication after surgery for relief of obstructive jaundice. Ann Surg. 1984;199:271–275. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198403000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeo CJ. Management of complications following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Clin North Am. 1995;75:913–924. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46736-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rumstadt B, Schwab M, Korth P, Samman M, Trede M. Hemorrhage after pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 1998;227:236–241. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199802000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welch CE, Rodkey GV, von Ryll Gryska P. A thousand operations for ulcer disease. Ann Surg. 1986;204:454–467. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198610000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikeguchi M, Oka S, Gomyo Y, Tsujitani S, Maeta M, Kaibara N. Postoperative morbidity and mortality after gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1517–1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bokey EL, Chapuis PH, Fung C, Hughes WJ, Koorey SG, Brewer D, Newland RC. Postoperative morbidity and mortality following resection of the colon and rectum for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:480–486; discussion 480-486. doi: 10.1007/BF02148847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsiotos GG, Munoz Juarez MM, Sarr MG. Intraabdominal hemorrhage complicating surgical management of necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1996;12:126–130. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reber PU, Baer HU, Patel AG, Triller J, Büchler MW. Life-threatening upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding caused by ruptured extrahepatic pseudoaneurysm after pancreatoduodenectomy. Surgery. 1998;124:114–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radeleff B, Noeldge G, Heye T, Schlieter M, Friess H, Richter GM, Kauffmann GW. Pseudoaneurysms of the common hepatic artery following pancreaticoduodenectomy: successful emergency embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:129–132. doi: 10.1007/s00270-005-0372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miura F, Asano T, Amano H, Yoshida M, Toyota N, Wada K, Kato K, Yamazaki E, Kadowaki S, Shibuya M, et al. Management of postoperative arterial hemorrhage after pancreato-biliary surgery according to the site of bleeding: re-laparotomy or interventional radiology. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:56–63. doi: 10.1007/s00534-008-0012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu C, Qiu YH, Luo XJ, Yi B, Jiang XQ, Tan WF, Yu Y, Wu MC. Treatment of massive pancreaticojejunal anastomotic hemorrhage after pancreatoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1625–1629. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J, Kim JK, Yoon W, Heo SH, Lee EJ, Park JG, Kang HK, Cho CK, Chung SY. Transarterial embolization for postoperative hemorrhage after abdominal surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vreeburg EM, Snel P, de Bruijne JW, Bartelsman JF, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the Amsterdam area: incidence, diagnosis, and clinical outcome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:236–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toyoda H, Nakano S, Takeda I, Kumada T, Sugiyama K, Osada T, Kiriyama S, Suga T. Transcatheter arterial embolization for massive bleeding from duodenal ulcers not controlled by endoscopic hemostasis. Endoscopy. 1995;27:304–307. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moran J, Del Grosso E, Wills JS, Hagy JA, Baker R. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: imaging of complications and normal postoperative CT appearance. Abdom Imaging. 1994;19:143–146. doi: 10.1007/BF00203489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker TG, Salazar GM, Waltman AC. Angiographic evaluation and management of acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1191–1201. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i11.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charbonnet P, Toman J, Bühler L, Vermeulen B, Morel P, Becker CD, Terrier F. Treatment of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30:719–726. doi: 10.1007/s00261-005-0314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lerut JP, Gianello PR, Otte JB, Kestens PJ. Pancreaticoduodenal resection. Surgical experience and evaluation of risk factors in 103 patients. Ann Surg. 1984;199:432–437. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198404000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith CD, Sarr MG, vanHeerden JA. Completion pancreatectomy following pancreaticoduodenectomy: clinical experience. World J Surg. 1992;16:521–524. doi: 10.1007/BF02104459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cirocco WC, Golub RW. Endoscopic treatment of postoperative hemorrhage from a stapled colorectal anastomosis. Am Surg. 1995;61:460–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee YC, Wang HP, Yang CS, Yang TH, Chen JH, Lin CC, Tsai CY, Chang LY, Huang SP, Wu MS, et al. Endoscopic hemostasis of a bleeding marginal ulcer: hemoclipping or dual therapy with epinephrine injection and heater probe thermocoagulation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:1220–1225. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez RO, Sousa A, Bresciani C, Proscurshim I, Coser R, Kiss D, Habr-Gama A. Endoscopic management of postoperative stapled colorectal anastomosis hemorrhage. Tech Coloproctol. 2007;11:64–66. doi: 10.1007/s10151-007-0330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trottier DC, Friedlich M, Rostom A. The use of endoscopic hemoclips for postoperative anastomotic bleeding. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18:299–300. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e318169039b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Umano Y, Horiuchi T, Inoue M, Shono Y, Oku Y, Tanishima H, Tsuji T, Tabuse K. Endoscopic microwave coagulation therapy of postoperative hemorrhage from a stapled anastomosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:1768–1770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wisniewski B, Rautou PE, Drouhin F, Narcy-Lambare B, Chamseddine J, Karaa A, Grange D. Endoscopic hemoclips in postoperative bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29:933–934. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(05)86460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyamoto N, Kodama Y, Endo H, Shimizu T, Miyasaka K. Hepatic artery embolization for postoperative hemorrhage in upper abdominal surgery. Abdom Imaging. 2003;28:347–353. doi: 10.1007/s00261-002-0041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris DC, Nichols DM, Connell DG, Burhenne HJ. Embolization of the left gastric artery in the absence of angiographic extravasation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1986;9:195–198. doi: 10.1007/BF02577940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]