Abstract

Objective

Reports on pregnancies in women with GSD-Ia are scarce. Due to improved life expectancy, pregnancy is becoming an important issue. We describe 15 pregnancies focusing on dietary treatment, biochemical parameters and GSD-Ia complications.

Study Design

Carbohydrate requirements (mg/kg/min), triglyceride and uric acid levels, liver ultrasonography and creatinine clearance were investigated before, during and after pregnancy. Data of the newborns were obtained from the records.

Results

In the first trimester, a significant increase in carbohydrate requirements was observed (p=0,007). Most patients had acceptable triglyceride and uric acid levels during pregnancy. No increase in size/number of adenomas was seen. In 3/4 patients, a decrease in GFR was observed after pregnancy. In three pregnancies, lactic acidosis developed during delivery with severe multi-organ failure in one. All but one of the children are healthy and show good psychomotor development.

Conclusion

Successful pregnancies are possible in GSD-Ia patients, although specific GSD-Ia related risks are present.

Keywords: pregnancy, glycogen storage disease type Ia, glucose metabolism, complications

Introduction

Glycogen storage disease type Ia (GSD Ia) is an autosomal recessive inborn error of carbohydrate metabolism due to a deficiency of the enzyme glucose-6-phosphatase. Deficiency of this enzyme leads to disturbed glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, and patients with GSD Ia therefore depend completely on exogenous sources of glucose. Biochemically, it is characterized by the combination of severe fasting hypoglycemia, hyperlactacidemia, hyperuricemia and hyperlipidemia.1,2 Clinically, it is characterized by stunted growth, hepatomegaly, wasted muscles, delayed puberty and a bleeding tendency due to impaired platelet function. The primary aim of treatment is prevention of hypoglycemia by administering exogenous glucose either by frequent meals, uncooked cornstarch (UCCS), or continuous gastric drip feeding (CGDF).3

This lifelong dietary treatment has dramatically improved the expected lifespan of patients with GSD Ia. More and more patients reach adult age, but several long-term complications have been observed such as glomerular hyperfiltration and proteinuria leading to renal insufficiency, liver adenomas with a small risk of malignant transformation, decreased bone density, anemia, ovarian cysts in females and rarely pulmonary hypertension.4

With increased life expectancy, pregnancy is becoming an important issue in female GSD Ia patients. The complications described above pose unique risks during pregnancy including the occurrence of hypoglycemia, possible increases in size or numbers of adenomas due to hormonal changes5 or a further decrease in renal function during pregnancy, as is seen in diabetes mellitus patients.6 Furthermore, in normal pregnancy, cholesterol and triglyceride levels increase significantly and uric acid initially decreases and thereafter rises in the second half of pregnancy.7,8 These biochemical fluxes may pose additional pregnancy-related risks for GSD Ia patients, who are already predisposed to hyperlipidemia and hyperuricemia in the non-pregnant state.

Reports on pregnancies in women with GSD Ia are scarce.9–14 Reports concerning the dietary management during pregnancy and the effect of pregnancy on adenomas and renal function in GSD Ia patients are not available at all. In this study, we describe the course and management of 15 pregnancies in 11 GSD Ia patients, with special focus on dietary treatment, metabolic control and the course of adenomas and renal function during pregnancy.

Material and Methods

We included all female GSD Ia patients from the metabolic centers of Hamburg (Germany), Düsseldorf (Germany), Florida (USA) and Groningen (the Netherlands), who had been under surveillance during their pregnancies. The diagnosis was confirmed by mutation analysis in all patients. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the respective institutions either as a prospective study (Florida, Düsseldorf) or as an exempt investigation because of the retrospective and anonymous collection of data, in accordance with Dutch law. Data were collected from the patient records by the treating physician and anonymous patient record forms were filled in that could not be traced to the individual patients. Written informed consent from the patients was obtained.

Hypoglycemia is defined as glucose concentrations < 63 mg/dl (3.5 mmol/l). Blood glucose concentrations were measured at home by means of a portable glucose meter if symptoms of hypoglycemia occurred and occasionally during 24 hour glucose measurements.

Data on the diets of the patients before, during and after pregnancy were collected. In all centers dietary adjustments in pregnancy were based on clinical symptoms of hypoglycemia, 24 hour blood glucose measurements and the above described biochemical parameters. Basal carbohydrate requirements before, during and within 6 months after pregnancy were calculated from the nocturnal carbohydrate intake and were expressed in mg/kg/min.

No specific treatment protocols for pregnant women with GSD Ia exist. In 2002 guidelines were published for the management of GSD Ia patients in general.3 These guidelines contain biomedical targets for the follow-up of these patients as well as recommendations for dietary and pharmacological treatment. In case of increased uric acid levels a xanthine oxidase inhibitor such as allopurinol® is recommended for prevention of gout and urate nephropathy. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors such as enalapril® should be started in case of persistent microalbuminuria for preventing further deterioration of renal function in patients.

Data on metabolic control and GSD Ia related complications before, during and after pregnancy were collected retrospectively. Patients were regarded to be in good metabolic control if they met the biomedical targets as defined in the guidelines of the retrospective European study on GSD I.3 According to these guidelines patients are considered to be in good metabolic control when triglycerides are < 530 mg/dl (6.0 mmol/l) and uric acid concentrations < 7.6 mg/dl (450 µmol/l). Triglyceride and uric acid concentrations in plasma were investigated according to standard laboratory procedures by colorometric and spectrophotometric analysis, respectively (Roche Modular).

Liver adenomas were monitored before, during and after pregnancy by performing ultrasonography of the liver. Nephropathy was diagnosed from the presence of microalbuminuria (defined as > 2.5 mg albumin/mmol creatinine) in morning urine samples. Estimated creatinine clearance was calculated from adjusted serum creatinine as described by Gault et al.15 Glomerular filtration rates before pregnancy and within 5–10 months after pregnancy were measured by I125 iothalamate and I131 hippuran clearance as described by Apperloo et al.16

Finally data with regard to conception and fetal outcome were obtained from the medical records. Neonatal hypoglycemia was defined as glucose levels < 45 mg/dl (2.5 mmol/l).

Differences in carbohydrate requirements, creatinine clearance and glomerular filtration rates between the periods before, during and after pregnancy were analyzed with the paired-samples t-test, by use of statistical software (SPSS 12.0.1).

Results

Patient characteristics

In total 15 pregnancies in 11 GSD Ia patients were included. The demographical data of these women are shown in table 1. Three patients have had multiple pregnancies. Two pregnancies occurred in two patients and one patient has had three successful pregnancies. Median age at conception was 29.3 years (range 21.0–34.7 years). Median weight before pregnancy was 62 kg (range 51–74 kg). Median Body Mass Index before pregnancy was 25.3 (range 21.9 – 28.9).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Patient | Centre | Age at conception (yrs) |

Height (cm) |

Weight at conception (kg) |

BMI at conception (kg/m2) |

Weight 3rd trimester (kg) |

Weight gain in pregnancy (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | 32.6 | 161 | 59 | 22.8 | 74 | 15 |

| 2 | H | 34.0 | 175 | 74 | 24.2 | 84 | 10 |

| 3.1 | G | 29.3 | 167.5 | 63 | 22.5 | 80 | 17 |

| 3.2 | G | 34.0 | 167.5 | 62 | 22.1 | 85 | 23 |

| 4 | G | 31.4 | 162 | 60 | 22.9 | 69 | 9 |

| 5 | G | 31.3 | 147 | 51 | 23.6 | 64 | 13 |

| 6 | D | 21.0 | 162 | 72 | 27.4 | 95 | 23 |

| 7 | D | 34.7 | 166 | 67 | 24.3 | 78 | 11 |

| 8 | D | 26.6 | 155 | 62 | 25.8 | 68 | 6 |

| 9.1 | D | 22.0 | 150 | 57 | 25.3 | 73 | 16 |

| 9.2 | D | 25.0 | 150 | 65 | 28.9 | NA | - |

| 10 | F | 31.0 | 154.4 | 65 | 27.3 | NA | - |

| 11.1 | F | 25.4 | 147 | 59 | 27.3 | 64 | 5 |

| 11.2 | F | 26.1 | 147 | 60 | 27.8 | NA | - |

| 11.3 | F | 28.5 | 147 | 59 | 27.3 | NA | - |

H= Hamburg, G = Groningen, D = Düsseldorf, F = Florida, BMI = body mass index, NA = not assessed

Conception

Out of the 11 included GSD Ia patients, five had delayed pubertal development, defined as reaching Tanner stage 4 later than the 95th percentile. In three out of seven investigated patients, polycystic ovaries were present. Of the 11 women included in our study, three failed to conceive after 12 months of unprotected intercourse. Two of these three women had polycystic ovaries and one of these two women with polycystic ovaries was treated with follicle stimulating hormone.

Dietary treatment

Before pregnancy, UCCS was taken at night in 11 of the 15 pregnancies, and in the other four cases CGDF. Patient 3 was initially treated with UCCS during the night, but developed frequent hypoglycemia in the first trimester. Her nocturnal diet was changed to CGDF in a hospital setting and continued throughout pregnancy; thereafter, no hypoglycemia was seen. During the second pregnancy of this patient, she was treated with CGDF at night throughout pregnancy, but frequent hypoglycemia again occurred in the first trimester. One episode of severe hypoglycemia required hospitalization and intravenous correction with an intravenous infusion of glucose.

Patient 4, one of the four patients treated with CGDF at night, suffered from severe nausea and pyrosis in the third trimester leading to decreased intake and recurrent hypoglycemia. She was admitted to the hospital and her diet was adapted to CGDF 24 hours per day. Thereafter, no hypoglycemia was observed.

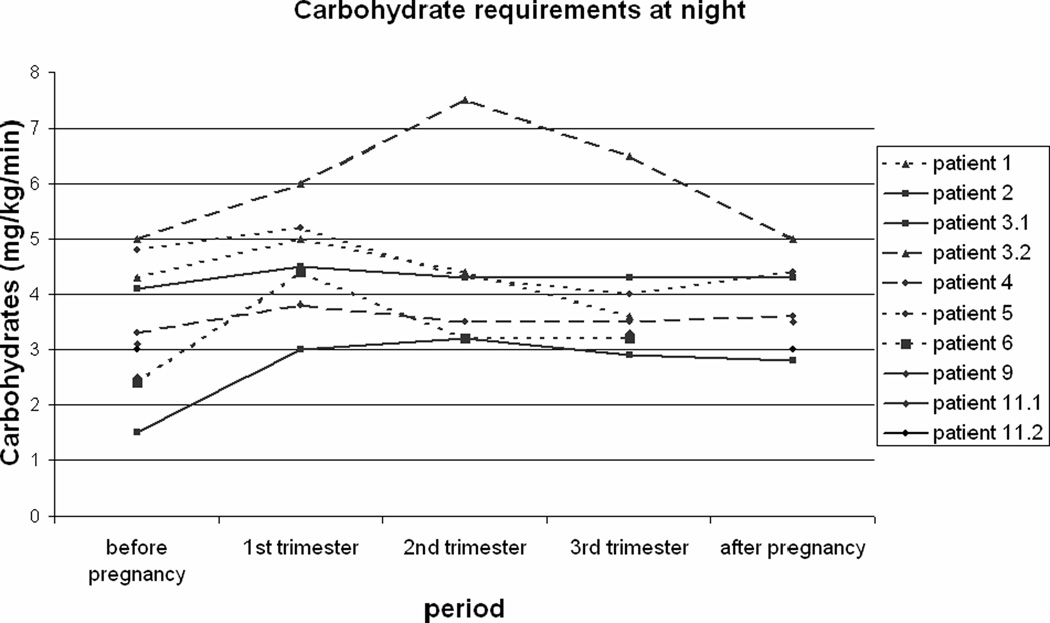

Figure 1 shows the basal carbohydrate requirements in 10 pregnancies of 8 GSD Ia patients, calculated as carbohydrate intake in mg/kg/min at night. The carbohydrate requirements in the first trimester of pregnancy are significantly higher compared to the requirements before pregnancy (p= 0.007) and after pregnancy (p= 0.05). Carbohydrate requirements in second and third trimester did not differ from the requirements before and after pregnancy.

Figure 1. Basal carbohydrate requirements during pregnancy.

Nocturnal carbohydrate intake in mg/kg/min for 10 pregnancies in 8 patients with glycogen storage disease type Ia.

Metabolic control in pregnancy

In six out of 15 pregnancies, an increase in frequency and/or severity of hypoglycemia was observed. In three pregnancies, hospitalization was needed for adjusting the diet to CGDF during day and night or treatment with glucose infusion.

Triglyceride and uric acid concentrations before pregnancy and maximal levels during pregnancy are shown in table 2. While two patients had a triglyceride concentration above 530 mg/dl before pregnancy, both showed acceptable triglyceride levels during pregnancy. One patient with triglycerides below 530 mg/dl before pregnancy, developed a hypertriglyceridemia in the second trimester. After pregnancy, triglycerides were elevated in three patients. One of these three patients did not have elevated triglycerides before or during pregnancy.

Table 2.

Metabolic control and complications before and during pregnancy.

| Patient | Centre | TG before pregnancy (mg/dl) |

Max TG in pregnancy (mg/dl) |

Max UA in pregnancy (mg/dl) |

Adenomas before (number / size of the largest) |

Course adenomas during pregnancy |

Microalbuminu ria (>2.5 mg/mmol creatinine) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | 332 | 344 | 4.6 | 4 / 5.7 cm | ↓ 2.7 cm | No |

| 2 | H | 187 | 240 | 6.3 | No | - | No |

| 3.1 | G | 174 | 313 | 4.4 | No | - | No |

| 3.2 | G | 193 | 250 | 2.7* | No | - | No |

| 4 | G | 631 | 480 | 5.9* | mult / 2.8 cm | status quo | Yes |

| 5 | G | 472 | 438 | 9.9 | mult / 6.6 cm | 1 extra | No |

| 6 | D | 746 | 301 | 6.8 | No | - | Yes |

| 7 | D | 396 | 857 | 5.9 | 3 / 8 cm | status quo | Yes |

| 8 | D | NA | NA | NA | mult / 3.4 cm | status quo | Yes |

| 9.1 | D | 347 | NA | 7.9 | No | - | No |

| 9.2 | D | 320 | NA | NA | No | - | No |

| 10 | F | NA | NA | 8.5 | mult / 7.3 cm | status quo | No |

| 11.1 | F | NA | 443 | NA | No | - | No |

| 11.2 | F | 397 | NA | 3.9 | 1 / 1 cm | status quo | No |

| 11.3 | F | 310 | NA | NA | 1 / 1 cm | status quo | No |

H= Hamburg, G = Groningen, D = Düsseldorf, F = Florida, TG = triglycerides, UA = uric acid,

= during allopurinol treatment, mult = multiple, NA = not assessed

In 12 cases, allopurinol was used before pregnancy and was discontinued before conception in 10 pregnancies. One patient had a uric acid concentration > 7.6 mg/dl before pregnancy during allopurinol treatment and continued to have increased concentrations during pregnancy without allopurinol. Two patients showed an elevation of uric acid during pregnancy after allopurinol treatment was discontinued. In two patients treated with allopurinol before pregnancy and with normal uric acid levels before and during pregnancy, uric acid was elevated after pregnancy.

GSD Ia complications during pregnancy

All patients were screened for adenomas before, during and after pregnancy by means of ultrasound investigations of the liver. In seven of 15 cases, one or more adenomas were present prior to pregnancy. In patient 4, a partial liver resection had been performed two years before pregnancy because of a hemorrhage in one of the adenomas, but this patient still had multiple adenomas. Follow-up during and after pregnancy showed that one of the seven patients developed an extra adenoma during pregnancy. In five out of seven patients, the size and number of adenomas remained unaltered. In one patient, a decrease in size of the adenoma was observed (table 2).

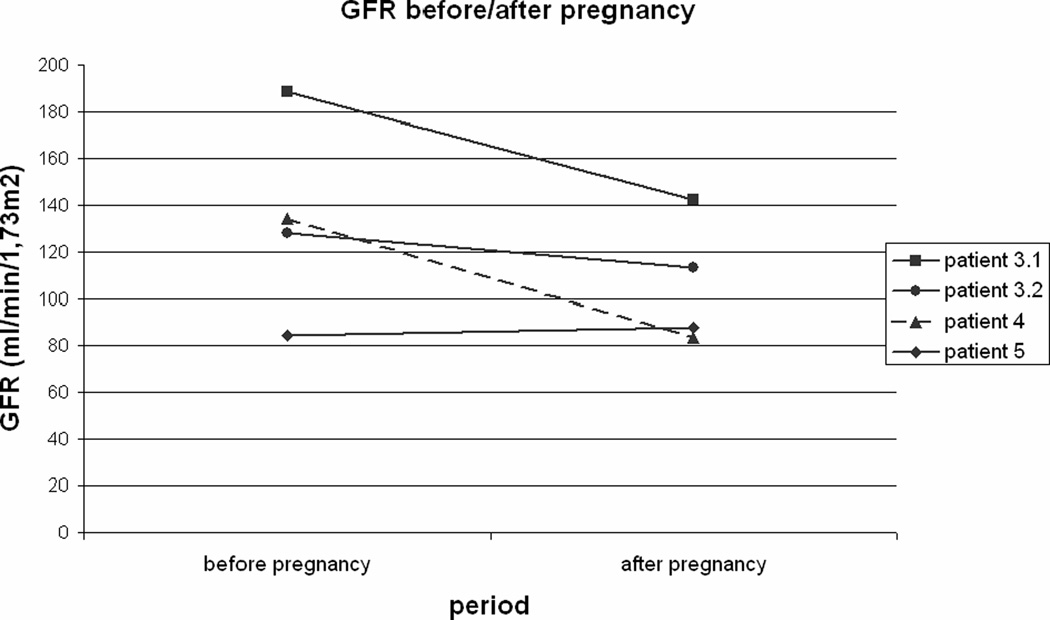

In four out of 15 pregnancies nephropathy with microalbuminuria was present prior to the pregnancy. In five patients, enalapril® was used. The enalapril® was discontinued in these patients prior to conception. Estimated creatinine clearance values were available in seven of the 15 pregnancies and showed a significant increase in the second trimester, when compared to the values before pregnancy and after pregnancy (p=0.04, p=0.04). In four pregnancies of three patients glomerular filtration rates were available before and after pregnancy. In three of these four pregnancies a decrease in GFR after pregnancy was observed (figure 2). No increase in microalbuminuria was seen. One patient without nephropathy developed severe proteinuria in the second trimester and hypertension in the third trimester, but completely recovered after pregnancy with no proteinuria documented for 2 years.

Figure 2. Glomerular filtration rates before and after pregnancy.

Glomerular filtration rates before and after pregnancy for 4 pregnancies in 3 patients with glycogen storage disease type Ia.

One of two GSD Ia patients with colitis experienced an aggravation of symptoms in the postpartum period.

Perinatal period

In twelve out of 15 pregnancies, a caesarean section was performed for various obstetric reasons, not related to GSD Ia. All patients were treated with a glucose infusion during labor. One patient developed intermittent hypoglycemia and a mild lactic acidosis during delivery. During the second delivery of this patient, again mild lactic acidosis was seen. Another patient suffered from severe hyperlactacidemia (31 mmol/l) and metabolic acidosis during delivery despite high-normal glucose levels. She developed a systemic inflammatory response syndrome with multi-organ failure and preterminal renal insufficiency. Hemodialysis was required, and she had to be admitted to an intensive care unit for 41 days. No data on metabolic control during pregnancy are available for this patient, but pre-pregnancy laboratory values showed good metabolic control. Of note, however, this patient has had a course complicated by epilepsy and mental retardation due to previous hypoglycemia, and she is being evaluated for a liver transplant due to hepatic adenomas, anemia and liver cirrhosis with hypoalbuminemia.

Offspring

The neonatal outcome of all 15 pregnancies is summarized in table 3. Two cases of prematurity, one case of fetal growth retardation and one case of macrosomia was observed. Hypoglycemia was documented in four of the15 neonates including the two neonates with macrosomia or fetal growth retardation. In three of these four cases, hypoglycemia was transient (< 24 hours) except for the dysmature child, who needed temporary gastric drip feeding because of feeding difficulties. The two premature children also were treated with gastric drip feeding because of prematurity, but showed no hypoglycemia. One of the premature children was born to the critically ill mother with hyperlactacidemia and had low APGAR scores (6/5/5 after 1/5/10 minutes). This child also showed delayed psychomotor development: walking at age 2 years and 1 month, and speaking 3–4 words at age 3 years. All other children had normal psychomotor development at the age of 1 year.

Table 3.

Outcome offspring of 15 pregnancies in 11 GSD Ia patients.

| Patient | Gestational age | Birth weight (grams) | Glucose < 45 mg/dl | PM development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41+4 | 4320 | Yes | Good |

| 2 | 40+6 | 3015 | No | Good |

| 3.1 | 38+4 | 3165 | Yes | Good |

| 3.2 | 38+4 | 3530 | No | Good |

| 4 | 38+3 | 3260 | No | Good |

| 5 | 38+0 | 2510 | Yes | Good |

| 6 | 37+4 | 3860 | No | Good |

| 7 | 37+0 | 2990 | No | Good |

| 8 | 34+6 | 2400 | No | Delayed |

| 9.1 | 38+3 | 3520 | No | Good |

| 9.2 | 38+0 | 3000 | Yes | Good |

| 10 | 35+4 | 1705 | No | Good |

| 11.1 | 42+0 | 3905 | No | Good |

| 11.2 | 41+5 | 3232 | No | Good |

| 11.3 | 40+0 | 3680 | No | Good |

Comment

Successful pregnancies are possible in GSD Ia patients, although specific GSD Ia related risks are present. Carbohydrate requirements showed large intra- and inter-individual variations. In the first trimester of pregnancy a significant increase in carbohydrate requirements was observed with a gradual return to pre-pregnancy carbohydrate requirements later in pregnancy. Although two patients in this sample had two pregnancies, in all pregnancies an increase in carbohydrate requirements in the first trimester of pregnancy was found. In normal pregnancy no increase in carbohydrate requirement is seen in early pregnancy, but an increase in peripheral insulin sensitivity in early pregnancy has been described.17 The increase in peripheral insulin sensitivity possibly causes a diminished glucose availability in blood, that can be compensated by an increased endogenous glucose production in times of need in healthy women. Because of the increase in carbohydrate requirement early in pregnancy and due to risks associated with hypoglycemia regular blood glucose measurements are recommended in GSD Ia patients throughout pregnancy.

Although an increase in uric acid and/or triglyceride levels was observed in some patients, both during pregnancy and in the postnatal period, the majority of our patients showed good metabolic control during pregnancy. This leads to the conclusion that good metabolic control during pregnancy can be achieved, although frequent follow-up of the biochemical targets is warranted. Lactate concentrations can increase during pregnancy due to hypoglycemia, hormonal changes and stress of pregnancy. Monitoring of lactate concentrations with a portable lactate meter18 may also be beneficial particularly in the first and third trimesters in an attempt to also maximize metabolic control.

This study has shown no evidence for increases in size or number of adenomas in this group of 15 pregnancies. Rupture of adenomas during pregnancy has been described in the past and poses a high mortality risk for both mother and child. Therefore Terkivatan et al. have recommended resection of large (≥ 5 cm) or growing symptomatic adenomas before pregnancy.5 Due to the small number of patients in our study, however, no conclusions can be drawn concerning this recommendation.

A significant increase in the estimated creatinine clearance was observed during pregnancy. This is compatible with the course in normal pregnancy, where a 40–65% increase in GFR has been described.19 In three out of four investigated patients, a decrease in GFR was observed after pregnancy, compared to the pre-pregnancy values. In pregnant patients with moderate –to-severe renal insufficiency due to diabetic nephropathy, a transient worsening of renal function in pregnancy was seen in 27% of patients and a permanent decline in 45%.6 Especially diabetes patients with a significantly low creatinine clearance before pregnancy are at risk.20 Nephropathy in GSD Ia patients resembles the course of diabetic nephropathy.21 Possibly, due to hemodynamic changes in pregnancy and the discontinuation of enalapril before and during pregnancy, a further decrease in GFR might develop in GSD Ia patients with known nephropathy, eventually leading to glomerular hypofiltration and possible renal insufficiency in some of the GSD Ia patients. It is generally advised to cease treatment with ACE inhibitors preconceptionally because of adverse effects for the fetus, such as hypotension, renal problems and growth restriction.22 Angiotensin II receptor antagonists, however, might be an alternative for GSD Ia patients with nephropathy, as described in pregnant patients with diabetic nephropathy.23 Whether the decreases in GFR described in our patients would have occurred in the absence of pregnancy and despite enalapril® treatment is not clear. However, the progressive deterioration of renal function in pregnancy should at least be considered in GSD Ia patients with low creatinine clearance values prior to pregnancy.

In three pregnancies, lactate acidosis developed during delivery with severe multi-organ failure in one case. In some cases higher glucose amounts might prevent lactic acidosis, although glucose levels in the severe case were high-normal. Metabolic deterioration during delivery can be a serious risk for the child, as lactic acidosis in the mother can cause serious problems in the neonate. Therefore frequent glucose controls and adequate treatment with glucose infusion according to the European guidelines3 are recommended during delivery.

The majority of the children born to GSD Ia mothers are healthy and show a good psychomotor development. Transient hypoglycemia may occur in these neonates, but this could well be accounted for by normal variation.

The fact that more healthier individuals are more likely to attempt pregnancy is not seen in the group of patients that we describe. Some of these patients even had multiple complications.

In conclusion good metabolic control is possible in GSD Ia patients during pregnancy. Physicians should be aware of the apparent increased carbohydrate requirements during the first trimester of pregnancy and possibly near the end of pregnancy. No significant increase in size or number of liver adenomas is observed in our patients. However, a further deterioration of renal function in GSD Ia patients, especially those with a low creatinine clearance prior to pregnancy, might be an important pregnancy-related risk in these patients. The development of hypoglycemias and lactic acidosis during pregnancy and delivery could pose an additional risk for impaired growth and delayed psychomotor development in children of GSD Ia mothers. This risk can be controlled by closely monitoring metabolic control during pregnancy and by glucose measurements and continuous glucose infusion during delivery.

Acknowledgements

We thank Christina E Morgan, Catherine E. Correia (University of Florida), Greet van Rijn and Esmee Udema (University Medical Center Groningen) for their help in preparation of the paper.

GRANT SUPPORT: These investigations were supported in part by NIH General Clinical Research Center Grant M01 RR 00082 (Florida) and NIH Mentored Career Award K23 RR 017560 (DW).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented in part at the Annual Symposium of the Society for the Study of Inborn Errors of Metabolism, Paris, France, Sept. 6–9, 2005.

References

- 1.Chen YT. Glycogen Storage Diseases. In: Scriver C, Childs B, editors. The metabolic & molecular bases of inherited disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005. p. 1521. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smit GPA, Rake JP, Akman HO, DiMauro S. The Glycogen Storage Diseases and Related Disorders. In: Fernandes J, Saudubray JM, van den Berghe G, Walter JH, editors. Inborn metabolic diseases : diagnosis and treatment. Berlin: Springer; 2006. pp. 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rake JP, Visser G, Labrune P, Leonard JV, Ullrich K, Smit GP. Guidelines for management of glycogen storage disease type I - European Study on Glycogen Storage Disease Type I (ESGSD I) Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161(Suppl 1):S112–S119. doi: 10.1007/s00431-002-1016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rake JP, Visser G, Labrune P, Leonard JV, Ullrich K, Smit GP. Glycogen storage disease type I: diagnosis, management, clinical course and outcome. Results of the European Study on Glycogen Storage Disease Type I (ESGSD I) Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161(Suppl 1):S20–S34. doi: 10.1007/s00431-002-0999-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terkivatan T, de Wilt JH, de Man RA, Ijzermans JN. Management of hepatocellular adenoma during pregnancy. Liver. 2000;20(2):186–187. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2000.020002186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Purdy LP, Hantsch CE, Molitch ME, Metzger BE, Phelps RL, Dooley SL, et al. Effect of pregnancy on renal function in patients with moderate-to-severe diabetic renal insufficiency. Diabetes Care. 1996;19(10):1067–1074. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.10.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potter JM, Nestel PJ. The hyperlipidemia of pregnancy in normal and complicated pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;133(2):165–170. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(79)90469-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lind T, Godfrey KA, Otun H, Philips PR. Changes in serum uric acid concentrations during normal pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1984;91(2):128–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1984.tb05895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mairovitz V, Labrune P, Fernandez H, Audibert F, Frydman R. Contraception and pregnancy in women affected by glycogen storage diseases. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161(Suppl 1):S97–S101. doi: 10.1007/s00431-002-1013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farber M, Knuppel RA, Binkiewicz A, Kennison RD. Pregnancy and von Gierke's disease. Obstet Gynecol. 1976;47(2):226–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson MP, Compton A, Drugan A, Evans MI. Metabolic control of von Gierke disease (glycogen storage disease type Ia) in pregnancy: maintenance of euglycemia with cornstarch. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75(3 Pt 2):507–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan IP, Havel RJ, Laros RK., Jr Three consecutive pregnancies in a patient with glycogen storage disease type IA (von Gierke's disease) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170(6):1687–1690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis R, Scrutton M, Lee P, Standen GR, Murphy DJ. Antenatal and Intrapartum care of a pregnant woman with glycogen storage disease type 1a. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;118(1):111–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee PJ, Muiesan P, Heaton N. Successful pregnancy after combined renal-hepatic transplantation in glycogen storage disease type Ia. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2004;27(4):537–538. doi: 10.1023/b:boli.0000037397.39725.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gault MH, Longerich LL, Harnett JD, Wesolowski C. Predicting glomerular function from adjusted serum creatinine. Nephron. 1992;62(3):249–256. doi: 10.1159/000187054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Apperloo AJ, de Zeeuw D, Donker AJ, de Jong PE. Precision of glomerular filtration rate determinations for long-term slope calculations is improved by simultaneous infusion of 125I-iothalamate and 131I-hippuran. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7(4):567–572. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V74567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catalano PM, Ishizuka T, Friedman JE. Glucose Metabolism in Pregnancy. In: Cowett R, editor. Principles of perinatal-neonatal metabolism. New York: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saunders AC, Feldman HA, Correia CE, Weinstein DA. Clinical evaluation of a portable lactate meter in type I glycogen storage disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2005;28(5):695–701. doi: 10.1007/s10545-005-0090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conrad KP. Mechanisms of renal vasodilation and hyperfiltration during pregnancy. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2004;11(7):438–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biesenbach G, Grafinger P, Stoger H, Zazgornik J. How pregnancy influences renal function in nephropathic type 1 diabetic women depends on their pre-conceptional creatinine clearance. J Nephrol. 1999;12(1):41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reitsma-Bierens WC. Renal complications in glycogen storage disease type I. Eur J Pediatr. 1993;152(Suppl 1):S60–S62. doi: 10.1007/BF02072091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sedman AB, Kershaw DB, Bunchman TE. Recognition and management of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor fetopathy. Pediatr Nephrol. 1995;9(3):382–385. doi: 10.1007/BF02254221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.How HY, Sibai BM. Use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in patients with diabetic nephropathy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002;12(6):402–407. doi: 10.1080/jmf.12.6.402.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]